Abstract

Fatigue and moisture damage have been recognized as the most prevalent problems on asphalt roads, necessitating large annual expenditures for road maintenance. Much industrial waste is added to bitumen paving to enhance its conventional quality while decreasing the negative impacts on the natural environment and increasing resistance to pavement distress. This research uses ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) to substitute conventional filler (Portland cement [PC]) in hot mix asphalt (HMA). To determine how the GGBFS affects the HMA's susceptibility to moisture and fatigue cracks, Marshall characteristics, tensile strength ratio (TSR), and index of retained strength (IRS) of the asphalt concrete were evaluated. HMA was prepared with different rates of GGBFS (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) instead of PC. The data support the usage of 50% GGBFS in asphalt pavements as a partial replacement of PC, which enhanced Marshal stability by 34.4%, reduced flow value by about 12.9%, and increased TSR and IRS by 11.1 and 14.54%, respectively. The fatigue resistance of the modified asphalt mix at the optimum rate was evaluated with the four-point bending beam test; the fatigue life (Nf) increased by 33.8% relative to the reference mixture. The results obtained from this research hold scientific value for researchers and method designers aiming to enhance the resistance of hot asphalt mixtures to moisture and cracking. Using waste materials as an alternative to PC contributes to cost reduction while mitigating the environmental damages associated with cement manufacturing. To summarize, this research highlights the significance of exploring sustainable options in the construction industry, emphasizing the importance of reducing costs, and minimizing environmental impacts.

1 Introduction

After the nineteenth century, the use of asphalt paving mixture spreads quickly around the world [1]. As a result, the total length of bituminous roads now exceeds three times the circumference of the Sun [2]. Significant investment is required for the development of the highways. The global interstate pavement construction industry has experienced substantial growth in recent decades as a result of a substantial increase in traffic volumes and permissible axial loads [3]. To mitigate the damages caused by these factors, there is a need for continuous improvement in road paving materials. This improvement is crucial to accommodate the predicted loads [4] and ensure the provision of affordable, safe, and long-lasting pavements [5]. Asphalt concrete (AC) consists of coarse and fine aggregate fillers and sometimes uses additives to enhance the AC performance.

Mineral filler is an inert substance that passes through a No. 200 sieve and can serve various functions in asphalt mixtures. First, filling the spaces left by the coarser particles and acting as a mineral aggregate component strengthens the mixture (increasing the mix’s stiffness). Second, when combined with a binder, filler forms mastic, the high-consistency cement or binder that holds together larger binder particles; a significant portion of the filler may remain suspended binder, and a lesser component forms the load-bearing structure [6,7].

“Durability, stability, flexibility, and skid resistance (in surface layers)” are the primary attributes that bitumen paving mixtures may possess [8]. The ability of hot mix asphalt (HMA) to resist the water action without suffering considerable decay is a crucial durability issue. The most common distress in HMA pavements is moisture damage, fatigue, and permanent deformation [9]. The main processes with moisture damage in bituminous pavement include the loss of the bitumen film cohesiveness and stiffness and the failure of the adhesive link between bitumen and aggregate [10] or the weakening of the bond among pavement layers [11]. The asphaltic pavement’s susceptibility to moisture might be viewed as a severe flaw that led to stripping and other issues like fatigue cracking [12].

The industry focuses on sustainability in construction to save energy and lower carbon dioxide emissions [13,14]. Employing wastes from diverse industrial processes conserves invaluable resources, lowers pollution, and recovers energy used through waste generation [14,15]. The substantial quantity of unprocessed pavement components used for road construction and repair, such as asphalt binder and gravel materials, represents a detriment to losing the earth's resources and the associated negative impacts on the surrounding environment [16]. Incorporating these wastes in the bituminous pavement is an environmentally friendly and cost-effective option that, if built, can significantly increase the pavement's resilience to the common distress experienced by flexible paving [17,18]. Blast furnace slag is a byproduct produced by iron manufacturers. Iron ore, coal, and limestone are delivered into the furnace, and the resulting molten slag floats above the melting iron at approximately 1,500–1,600°C. The chemistry of melted slag, about 30–40% SiO2 and 40% CaO, is virtually identical to the chemical composition of Portland cement (PC) [19]. The massive store of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) has a variety of consequences. It takes up much space, and its sewage leakage causes water contamination and soil devastation during wet seasons. Environmental reuse ground granulated blast slag (GGBS) will address these challenges [20]. Compared to the energy needed to produce PC, less power is required to produce GGBS. Carbon dioxide emissions will significantly reduce when GGBS is used instead of PC. As a result, GGBS is an eco-friendly building material. GGBFS is widely used as an alternative cementitious material to PC in concrete works [21,22]. The use of GGBFS as an alternative cementitious material to PC is commonly used in concrete works. Few studies have addressed its use in various types of asphalt mixtures (cold, warm, and hot). The goal of this study is to learn more about whether or not it is possible to use GGBFS as a cement material in asphalt mixtures industry. Different amounts of slag will be added to the mixtures to make them more resistant and improve their performance.

Al-Khafaji et al. created a new cold mix asphalt designed as a binder course from waste resources. As fillers in a polymer-modified emulsion, GGBS was used to replace the mineral filler (limestone dust), and cement kiln dust (CKD) was used as an activator. The mechanical properties were examined using the indirect tensile stiffness modulus, and water susceptibility was assessed using the stiffness modulus ratio. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was then used to analyze the samples' microstructure. The outcomes showed that adding GGBS and CKD significantly improved the mechanical characteristics and the water susceptibility. SEM verified these improvements and linked them to the early hydration product production in the sample [23].

Shahba et al. studied the possibility of partially substituting styrene–butadiene–styrene with GGBS to modify bitumen and porous asphalt mixtures. The following tests assessed modified bitumen and asphalt mixes: “penetration test, softening point, ductility, Marshall stability (MS), indirect tensile strength (ITS), moisture susceptibility, uniaxial compression test, porosity, and permeability.” The finding suggests that the additives used reduced bitumen penetration and ductility by 6–22 and 6.5–21%, respectively, while increasing its softening point from 43 to 60°C, strengthening asphalt mixture parameters such as Marshall strength, ITS, and uniaxial compression strength [24].

Al-Hdabi et al. evaluated using GGBFS instead of conventional mineral filler to produce the HMA. Marshall test, ITS test, compressive strength test, and mean MS ratio evaluated the mixes. The finding supported using GGBFS as a mineral filler in HMA. The stability was increased by 40% compared with the traditional blend; the durability of the modified mix was also enhanced. On the other hand, both the tensile strength ratio (TSR) and index of retained strength (IRS) of the GGBFS mix exhibited significant improvement compared with the control mix [25].

Chegenizadeh et al. studied the impact of applying GGBFS as a portion of filler materials (hydrated lime [HL]) in HMA on pavement distress. The control mixes with 1.5% HL were compared with the modified mixes with 1.5, 3, and 5% instead of HL. The results promote the usage of GGBFS in asphaltic pavements. The mixes with 3% GGBFS gave the best results after tasting with fatigue, rutting, and AMPT tests [26].

Previous research has mainly focused on enhancing the efficiency of asphalt pavements or using alternate filler materials. This research aims to examine the possibility of utilizing GGBFS as a filler in HMA and demonstrate its influence on MS, moisture susceptibility (TSR and IRS), and fatigue resistance. The mixes designed with various proportions of GGBFS were used to assess the effect on moisture damage compliance with Iraqi requirements SCRB/R9, 2003 [27] and evaluate the performance of the modified asphalt mix using a four-bending beam test. The findings add significant scientific value to the study by extending the lifespan of the pavement and increasing its strength. Additionally, the environmental impact of this approach is noteworthy as GGBFS is considered an industrial waste material, contributing to reducing the use of conventional cement materials and mitigating environmental waste.

2 Materials and test methods

The starting point of the laboratory work was to identify the optimal bitumen content (OBC) for the reference mixture (without the addition of the GGBFS). The OBC determined by this test will be used to create mixes for the Marshall test, indirect tensile, and compressive strength tests calculating TSR and IRS, respectively.

2.1 Asphalt cement

This study used one grade of asphalt cement (AC 40–50) from the al-Dora refinery. It was tested to ensure it complied with SCRB/R9, 2003. The physical characteristics of AC are represented in Table 1. The tests were done at the labs of the civil engineering department at the university of technology, Baghdad, Iraq.

Asphalt binder’s physical characteristic

| The conditions of laboratory tests | Standards | Tests values | Iraqi limitation CSRB/R9, 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration, 25°C, (0.1 mm) | ASTM D5 | 44.5 | 40–50 | |

| Ductility, 25°C, 5 cm/min | ASTM D113 | +120 | >100 | |

| softening point (ºC) | AD36 | 51.6 | — | |

| Specific gravity 25ºC | ASTM D70 | 1.046 | — | |

| Flash and fire point | ASTM D92 | Flash | 295ºC | >232° |

| Fire | 302ºC | — | ||

| Rotational viscosity Pa s | ASTM-D4402 | 0.543@135ºC | ||

| 0.157@165ºC | ||||

2.2 Aggregate

Crushed stone from the Al-Nebaie quarry near Al-Taji, north of Baghdad, was used in this investigation. By conducting standard laboratory tests on coarse and fine aggregates, it was verified that they conform to the state Corporation of Roads and Bridges SCRB R/9 for aggregates used in the asphalt surface layer regarding gradation and physical properties. The wearing course aggregate's maximum size must adhere to the SCRB R/9, 2003. Table 2 and Figure 1 illustrate the used aggregate’s physical properties and their gradient curves. The test were conducted by the National Center for Constructions Labs, Baghdad.

Coarse and fine aggregate’s physical characteristics

| Laboratory test | ASTM designations | Coarse aggregate | Fine aggregate | Iraqi limitation CSRB/R9, 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Bulk specific gravity | ASTM C127, C 128 | 2.615 | 2.626 | — |

| % Water absorption | ASTM-C 127, C 128 | 0.362 | 0.481 | — |

| Toughness, by Los Angeles abrasion test | ASTM-C131 | 20.5% | — | Max. 30% |

Aggregate’s gradation curve.

2.3 Filler

Cement, HL, and stone dust are the three fillers used most frequently in asphalt mixtures. It is feasible to use some materials as a whole or as a partial replacement for the filler to enhance the qualities of the asphalt mixture. In this study, PC and GGBFS were both used.

2.3.1 PC

The conventional asphalt mix was made using local ordinary PC as a mineral filler. The physical characteristics of PC are illustrated in Table 3.

Physical characteristics of PC (tests were done by the NCCL, Bagdad, Iraq)

| Properties | Tests results |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 3.15 |

| Passing sieve no. 200 (0.075 mm) | 96% |

| Fineness (cm2/g) | 3,200 |

2.3.2 GGBFS

GGBFS, in contrast, can be produced by the iron-making industry through organized processes based on temperature and duration, or it can be obtained from iron sections. Table 4 represents GGBFS’s physical properties.

Physical characteristics of GGBFS (the material processor processed these data)

| Property | Test results |

|---|---|

| Slag | Hot |

| Type | Powder |

| Color | Light grey |

| Fineness | 4,900–5,100 cm2/g |

| Specific gravity | 2.8 |

| Passing sieve No.200 (0.075 mm) | 97.5% |

3 Experimental work

3.1 Marshal mix design method

The technique entails producing and complying with cylindrical asphalt paving mixture specimens measuring 4 in. (101.6 mm) in diameter and nominally 2.5 in. (63.5 mm) in height, according to ASTM D6926-16 [28].

Determining the optimum binder content (OBC) was the first step. The asphaltic mixes were made and evaluated according to ASTM 6927-15 [29] for stability (MS), flow, density, air voids (VA), voids in mineral aggregate, and voids filled with asphalt. There were 15 prepared specimens in total (three for every%). The asphalt content of the mixtures was 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, and 6%, respectively, by weight of the total mix. Consequently, the OBC was determined to be 4.9% of the total weight of the mix.

The second stage of the laboratory work included employing the optimum asphalt content that was calculated in preparing samples for the reference asphalt mixture (without adding GGBFS) and the improved mixtures where GGBFS was added in four different proportions, namely 25, 50, 75, and 100% by the weight of the mineral filler. These mixtures were then tested with the Marshal test to evaluate their MS, which represents the highest load resistance to the plastic flow, whereas the flow correlates with the strain’s value at the highest load trace. Figure 2 shows the samples' preparation, mixing, and testing.

(a) Preparing the aggregate, (b) adding AC to the aggregate, (c) samples used in the tests, and (d) testing the samples.

3.2 TSR specimen preparation and testing

To assess the moisture susceptibility of AC specimens ASTM D4867M-09 standards are followed [30]. The samples used in these tests had an VA of 7 ± 1% (the same as the number of voids in the field) obtained by trying different blows, as shown in Figure 3.

Relationship between number of blows and % A.V.

After being removed from the mold, the prepared specimens were allowed to sit at room temperature for 24 h. They were then immersed in a water bath at 25°C for 30 min. The ITS [31] test procedure involves compressing a cylinder sample under two strips, creating a tensile stress in the vertical diametric plane and ultimately causing the sample to break. The ITS was run at a 50.8 mm/min rate until the sample broke. The maximum load value was captured at the instant the fracture appeared. The ITS was found using the following equation (Figures 4 and 5):

where St is the tensile strength (kPa), P is the maximum load (N), t is the height of the specimen (mm), D is the model diameter.

Testing sample with tensile strength apparatus.

Specimens tested by compressive strength device.

To determine the indirect strength ratio (TSR), two sets of molds are created for each additive percentage. Each set consists of three specimens. One of the groups tested dry, and the other wet. Wet specimens were placed in a vacuum container filled with distilled water to achieve a 55–80% saturation ratio. These partially saturated specimens are placed in a bath containing distilled water at 60 ± 1°C for 24 h. Finally, the temperature of the samples was adjusted to 25 ± 1°C by immersing them in another water bath before conducting the test. A constant load of 50 mm/min at 25°C was applied until failure, and the maximum load at failure was recorded and calculated for each group.

The indirect tensile ratio (TSR) is computed following equation (2), and the minimum value of ITR should be 80% to meet Iraqi standards SCRB/R9, 2003.

where TSR is the tensile strength ratio (%), S 1 is the soaked subset's relative tensile strength (kPa), and S 2 is the dry subset's relative tensile strength (kPa).

3.3 IRS: Specimen’s preparation and testing

ASTM D1075-11 [32] covers the measurement of the loss of compressive strength resulting from the action of water on compacted bituminous mixtures containing asphalt cement. Six samples, with 101.6 mm in diameter and 101.6 mm in height, were created for each percentage of the additive that has been used, and the samples were separated into two sets. The first set was composed of three samples left in the air path over 4 h at 25°C, after which the compressive test was conducted, and the mean value for the tested samples was documented (S 1). The other set similarly included another three samples. They were treated by storing them in a water bath to stay 24 h at 60 ± 1°C, then removing them and placing them in the water bath for 2 h at 25 ± 1°C. The test was then carried out on all these samples, and the mean value was documented (S 2). The experiment used a compressive force at a constant rate of 0.2 in./min (5.08 mm/min) to determine the maximal resistance load before failure. The IRS was determined following ASTM D 1075-07 equation (3), and the SCRB/R9, 2003, identified that the minimum value of IRS should be 70% to meet Iraqi standards.

where S 2 is the specimen’s wet compressive strength (kPa), S 1 is the specimen’s dry compressive strength (kPa).

3.4 Four-point bending beam test

This test was performed using the flexural beam fatigue device, Figure 6, on the conventional mix with PC and modified asphalt mix using GGBFS. The test was done at the National Center for Construction Laboratories and Research laboratories. The test procedure was adopted according to AASHTO T321-14 [33] for the flexural beam test.

Flexural beam fatigue device.

3.4.1 Fatigue sample preparation

The samples were compacted using the rolling wheel compactor (RWC), Figure 7, according to the Asphalt Institute (1982) recommendations, which pointed to this compaction method creating samples more simulated to the in situ conditions.

The RWC.

The molds have a standard dimension of 400 mm in length, 300 mm in width, and 120 mm in height; they were used to create test beams by cutting the samples in several beams of 380 ± 6 mm in length, 63 ± 6 mm in width, and 50 ± 6 mm in height (Figure 8). The sample weight was approximately 13,800 g compacted to achieve the desired void percentage, which was 3.96%.

Fatigue test samples.

4 Results and discussion

To establish the optimum asphalt concentration in AC mixtures, five percentages of asphalt contents (4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.0%) by weight of the mixture are used. It was found to be 4.9% by weight of the total mix.

4.1 Marshal stability and flow

Mixtures were prepared, and the Marshall test was performed to decide the controlled and the improved HMA’s properties and their suitability for road construction. Figure 9 depicts the MS results. The minimum stability requirement of 8 kN was met. The stability of all samples with varying percentages of GGBFs surpasses the performance of the controlled mix. The maximum stability value was obtained with HMA containing 50% GGBF with a 34.4% improvement rate. The HMA with 100% yielded the lowest value, but it is still higher than the control mix with 5.4%, and these results agree with Hanson et al. [26]. This means it can withstand more horizontal deformation when subjected to heavy traffic loads. This improvement in MS values of GGBFS mixtures might be attributed to GGBFS particles strengthening the binder and enhancing the stiffness and cohesion of the new mastic [25].

The effect of GGBFS content on MS.

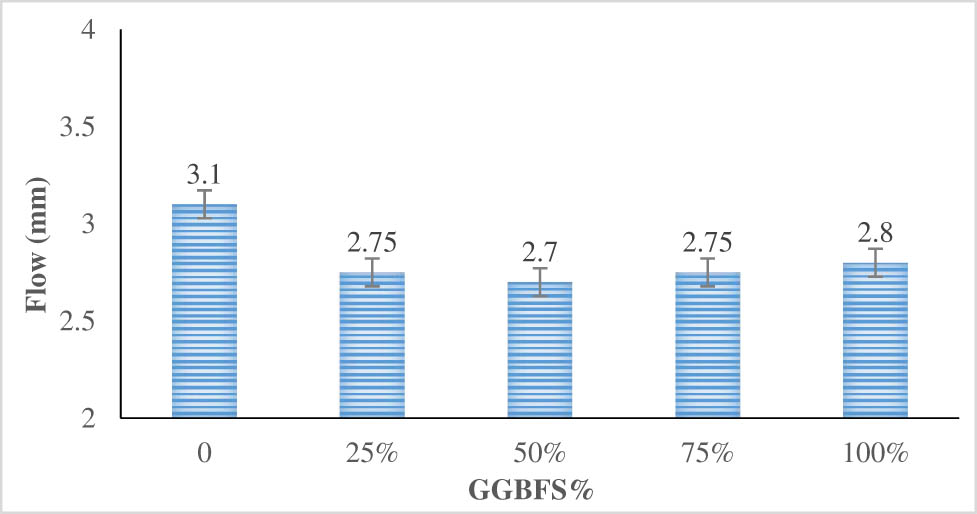

The flow value is the overall deformation experienced by the Marshall test specimen at maximum load. Figure 10 represents the flow results for control and modified mixes. The flow value decreased gradually as GGBFS increased to 50% replacement. Because of the absorption of hydrocarbon elements from the asphalt, the stiffening of the mix makes it more stable and less deformed. As the percentages of the additive increase, so does the absorption rate. As a result, the binding between the mix's components weakens the flow value increases, and thus, its tendency to deform increases.

Effect of GGBFS content on Marshall flow.

4.2 TSR

Including GGBFS significantly influences the amount of TSR in all the percentages employed in this article. As shown in Figure 11, values rose from 78.3 to 87% when the GGBFS content increased to 50% compared with the traditional mix, which will lead to lowering the potential hazard of moisture damage [25]. In contrast, increasing the GGBFS to more than 50% causes a reduction in the magnitude of tensile strength. Hence, the TSR of modified asphalt mixes is low due to the excessive hardness of the modified asphalt. This reduces the mix’s workability and the amount of asphalt binder that coats the aggregate particles, rendering them susceptible to water infiltration and feeble. However, their resistance is still more significant than the reference mix [24].

Effect of GGBFS content on TSR.

4.3 IRS

The IRS was employed to assess the resistance of the mixtures to water damage for both conventional and mixes containing varying percentages of GGBFS. IRS calculated the average compressive strength of conditioned specimens (wet) to unconditioned models (dry) in each percent of GGBFS as a ratio. The results of the test are illustrated in Figure 12. The enhancement in IRS was clearly in the HMAs with GGBFS in all categories. The highest value was 88.2%, recorded at 50% GGBFS, while the control mixture with PC had a 77% IRS. Employing GGBS as a partial substitution for cement in HMA mixes has improved strength and durability. The increased strength can be attributed to the increased activity of GGBS with cement [21]. Continuously increasing the ratio of GGBFS decreases the compressive strength because of the rising hardness, making the asphalt mixture brittle and less resistant to applied loads.

Impact of GGBFS on IRS.

4.4 Fatigue test result

A four-point bending test was conducted to evaluate the impact of adding GGBFS for enhancing HMA properties to resist fatigue cracking. The test was done according to the AASHTO T321 procedure. Constant strain mode at 400 µε, 20°C, and 5 Hz were the test variables that were input to the device’s software. The initial stiffness and the fatigue life for control and modified asphalt mixes are explained in Figures 13 and 14.

The initial stiffness of the HMAs before and after improvement.

The relationship between HMA type and the number of cycles.

The initial stiffness of HMA is defined as the flexural stiffness at the 100th load cycle. Figure 13 shows the effect of the GGBFS on the initial stiffness value. There was an increase in stiffness by 19% compared with the control mix, which conformed to the previous test result.

In this study, the bitumen mix beams’ fatigue life (Nf) was defined as the total number of cycles that caused a 50% reduction in the initial flexural stiffness.

From the analysis of Figure 14, the number of cycles increased significantly by adding 50% GGBFS; the Nf increased by 33.8% relative to the reference mixture. The reason for this is that the use of GGBFS led to an increase in stiffness and an improvement in the mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures. The results are consistent with Chegenizadeh et al. [26]. Using GGBFS in HMA could be a promising solution for developing more durable and sustainable asphalt pavement.

5 Conclusion

This study has demonstrated the potential of using GGBFS as a substitute for cement in asphalt mixtures. The findings of this research highlight the following key points:

MS values significantly improve with the addition of GGBFS at different percentages (25, 50, 75, and 100%). Comparing the MS values to the conventional mix, which contained only ordinary PC as a filler, shows increases of 12.9, 34.4, 18.27, and 5.3%, respectively. These results could be due to enhancing the stiffness and cohesion of the new mastic.

The flow value of the mix was also impacted by using GGBFS in place of cement. For the compounds with 25, 50, 75, and 100% cement substitution, the flow value dropped by 11.29, 12.9, 12.25, and 9.67%, respectively. This shows that a greater GGBFS concentration causes a reduction in the mix's flow ability.

The indirect tensile ratio was improved by comparing each GGBFS combination to the standard mix. With rising GGBFS composition from 0 to 100%, the TSR reached its maximum value of 87% at 50% with a 9.84% increase rate. This shows that GGBFS improves the mix's tensile characteristics.

Including GGBFS also positively affected the mix’s compressive strength. With 50% GGBFS content, the IRS reached 88.2%, demonstrating improved compressive strength recorded at 13.66% over the reference mixture. Increasing the activity of GGBS with cement improves the compressive strength.

In high concentrations, GGBFS hurts the performance of asphalt mixes by lowering their tensile and compressive strengths. This is because GGBFS is absorbed by the soft parts of asphalt (aromatic oils), which makes the bitumen stiff. As a result, bitumen becomes harder to deal with, and excellent workability is more challenging to achieve.

A relative improvement of around 33.8% was observed between the mix generated with 50% GGBFS and the reference mixture during the Nottingham fatigue test, indicating a considerable improvement in resistance to fatigue cracks. This improvement in crack resistance supports the results obtained during previous tests.

The experiments prove that GGBFS might partially replace the PC when utilized in an appropriate ratio.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the added scientific value that GGBFS inclusion in asphalt mixtures brings. The improved stability, tensile and compressive strengths, and fatigue crack resistance demonstrate the applicability of these findings in the design and construction of asphalt pavements. However, caution should be exercised when using high concentrations of GGBFS since they might affect the performance of the mix in terms of workability and strength.

For future work, it is recommended to try other rates of GGBFS substitution to identify the optimal ratio that achieves the best results. In addition, it might conduct more performance tests to evaluate the GGBFS mix's behavior against rutting and low-temperature cracks.

Limitations: In scientific experimentation, the condition of laboratory equipment used for conducting tests and the difficulty in obtaining laboratory materials can indeed have an impact on the results. Additionally, the proportions of the additive used may also affect the outcomes. Therefore, it is recommended to explore alternative proportions. It is important to note that these factors should be considered within a scientific framework to ensure accurate and reliable results.

-

Funding information: We declare that the manuscript was prepared depending on the personal effort of the author, and there is no funding effort from any side or organization.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Most datasets generated and analyzed in this study are in this submitted manuscript. The other datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author with the attached information.

References

[1] Rahman A, Ali SA, Adhikary SK, Hossain QS. Effect of fillers on bituminous paving mixes: An experimental study. J Eng Sci. 2012;3(1):121–7. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269507712.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Partl MN. Towards improved testing of modern asphalt pavements. Mater Struct. 2018;51(166):1–12. 10.1617/s11527-018-1286-9.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Shapie SS, Taher MN. A review of steel fiber’s potential use in Hot Mix Asphalt. IOP Conf. Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2022;1022(1):012024.10.1088/1755-1315/1022/1/012024Search in Google Scholar

[4] Caroles L. Asphalt elasticity modulus comparison using modified laboratory LWD against UMMATA method lucky. Civ Eng J. 2020;8(6):1257–67. www.CivileJournal.org.10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-06-012Search in Google Scholar

[5] Airey GD, Rahman MM, Collop AC. Absorption of bitumen into crumb rubber using the basket drainage method. Int J Pavement Eng. 2003;4(2):105–19.10.1080/1029843032000158879Search in Google Scholar

[6] Varma VA, Lakshmayya MTS. A review on different types of wastes used as fillers in bituminous mix. Int J Civ Eng Technol. 2018;9(9):289–300. http://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=9&IType=9.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Murana AA, Yakubu MU, Olowosulu AT. Use of carbide waste as mineral filler in hot mix asphalt. Sci Technol Educ. 2020;8(2):108–20.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Abdulhafedh A. Prototype road surface management system. World J Eng Technol. 2016;4:325–34.10.4236/wjet.2016.42033Search in Google Scholar

[9] Albayati AH. A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement. Open Eng J. 2023;13:1–25.10.1515/eng-2022-0463Search in Google Scholar

[10] Joni HH, Abed AH. Evaluation the moisture sensitivity of asphalt mixtures modified with waste tire rubber. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; 2022. p. 1–13.10.1088/1755-1315/961/1/012029Search in Google Scholar

[11] Nawir D, Mansur AZ. Effects of HDPE utilization and addition of wetfix-be to asphalt pavement in tropical climates. Civ Eng J. 2022;8(8):1665–78.10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-08-010Search in Google Scholar

[12] Mawat HQ, Ismael MQ. Assessment of moisture susceptibility for asphalt mixtures modified by carbon fibers. Civ Eng J. 2020 Feb;6(2):304–17.10.28991/cej-2020-03091472Search in Google Scholar

[13] Dulaimi A, Shanbara HK, Jafer H, Sadique M. An evaluation of the performance of hot mix asphalt containing calcium carbide residue as a filler. Constr Build Mater. 2020;261:1–10. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119918.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Payá J, Monzó J, Borrachero MV. Fluid catalytic cracking catalyst residue (FC3R): An excellent mineral by-product for improving early-strength development of cement mixtures. Cem Concr Res. 1999;29(11):1773–9.10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00164-7Search in Google Scholar

[15] Nistratov AV, Klimenko NN, Pustynnikov IV, Vu LK. Thermal regeneration and reuse of carbon and glass fibers from waste composites. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(5):967–84.10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-05-04Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ismael MQ, Joni HH, Fattah MY. Neural network modeling of rutting performance for sustainable asphalt mixtures modified by industrial waste alumina. Ain Shams Eng J. 2023;14(5):101972.10.1016/j.asej.2022.101972Search in Google Scholar

[17] Cardone F, Spadoni S, Ferrotti G, Canestrari F. Asphalt mixture modification with a plastomeric compound containing recycled plastic: laboratory and field investigation. Mater Struct. 2022;55(109):1–12. 10.1617/s11527-022-01954-4.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hussein SA, Al-Khafaji Z, Alfatlawi TJM, Abbood AKN. Improvement of permeable asphalt pavement by adding crumb rubber waste. Open Eng. 2022;12(1):1030–7.10.1515/eng-2022-0345Search in Google Scholar

[19] Arabani M, Azarhoosh AR. The effect of recycled concrete aggregate and steel slag on the dynamic properties of asphalt mixtures. Constr Build Mater. 2012;35:1–7. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.02.036.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Chen Z, Xie J, Xiao Y, Chen J, Wu S. Characteristics of bonding behavior between basic oxygen furnace slag and asphalt binder. Constr Build Mater. 2014;64:60–6. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.074.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Saklecha PP, Kedar RS, Professor A. Review on ground granulated blast-furnace slag as a supplementary cementitious material. Int J Comput Appl. 2015;975:8887.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Tung TM, Babalola OE, Le D. Evaluation of the post fire mechanical strength properties of recycled aggregate concrete containing GGBS: optimization and prediction using machine learning techniques. Asian J Civ Eng. 2023;24:1639–66.10.1007/s42107-023-00593-6Search in Google Scholar

[23] Al-Khafaji R, Dulaimi A, Sadique M, Aljsane A. Application of cement kiln dust as activator of ground granulated blast slag for developing a novel cold mix asphalt. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2021. p. 1–12.10.1088/1757-899X/1090/1/012029Search in Google Scholar

[24] Shahba S, Ghasemi M, Marandi SM. Effects of partial substitution of styrene-butadiene-styrene with granulated blastfurnace slag on the strength properties of porous asphalt. Int J Eng Trans A Basics. 2017;30(1):40–7.10.5829/idosi.ije.2017.30.01a.06Search in Google Scholar

[25] Al-Hdabi A, Al-Sahaf NA, Mahdi LA, Yesar Z, Moeid H, Hassan M. Laboratory investigation on the properties of asphalt concrete mixture with GGBFS as filler. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2019. p. 1–12.10.1088/1757-899X/557/1/012063Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chegenizadeh A, Hanson SW, Nikraz H, Kress CS. Effects of ground-granulated blast-furnace slag used as filler in dense graded asphalt. Appl Sci. 2022 Mar;12:1–15. 10.3390/app12062769%0Aacademic.Search in Google Scholar

[27] State Commission of Roads and Bridges(SCRB/R9). General specification for roads and bridges. Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Housing and Construction Department of Planning and Studies, Baghdad; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[28] ASTM D 6926. Standard practice for preparation of bituminous specimens using Marshall. Annu B Am Soc Test Mater ASTM Stand. 2014;i:1–6.Search in Google Scholar

[29] ASTM D 6927-15. Standard test method for Marshall stability and flow of bituminous mixtures. Annu B Am Soc Test Mater ASTM Stand. 2015;i:1–7.Search in Google Scholar

[30] ASTM D4867/4867M-09. Standard test method for effect of moisture on asphalt concrete paving mixtures. Am Soc Test Mater. 2014;i(Reapproved):1–5. www.astm.org.Search in Google Scholar

[31] ASTM D 6931. Standard test method for indirect tensile (IDT) strength of bituminous mixtures. 2017;1:3–7.Search in Google Scholar

[32] ASTM D1075-11. Standard test method for effect of water on compressive strength of compacted. Test. 2011;4(Reapproved):1–3.Search in Google Scholar

[33] AASHTO T321-14. Standard method of test for determining the fatigue life of compacted asphalt mixtures subjected to repeated flexural bending. Am Assoc State Highw Transp Washingt DC, USA. 2014;1–11.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Methodology of automated quality management

- Influence of vibratory conveyor design parameters on the trough motion and the self-synchronization of inertial vibrators

- Application of finite element method in industrial design, example of an electric motorcycle design project

- Correlative evaluation of the corrosion resilience and passivation properties of zinc and aluminum alloys in neutral chloride and acid-chloride solutions

- Will COVID “encourage” B2B and data exchange engineering in logistic firms?

- Influence of unsupported sleepers on flange climb derailment of two freight wagons

- A hybrid detection algorithm for 5G OTFS waveform for 64 and 256 QAM with Rayleigh and Rician channels

- Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy

- Exploring the potential of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for transportation

- Impact of insulation on energy consumption and CO2 emissions in high-rise commercial buildings at various climate zones

- Advanced autopilot design with extremum-seeking control for aircraft control

- Adaptive multidimensional trust-based recommendation model for peer to peer applications

- Effects of CFRP sheets on the flexural behavior of high-strength concrete beam

- Enhancing urban sustainability through industrial synergy: A multidisciplinary framework for integrating sustainable industrial practices within urban settings – The case of Hamadan industrial city

- Advanced vibrant controller results of an energetic framework structure

- Application of the Taguchi method and RSM for process parameter optimization in AWSJ machining of CFRP composite-based orthopedic implants

- Improved correlation of soil modulus with SPT N values

- Technologies for high-temperature batch annealing of grain-oriented electrical steel: An overview

- Assessing the need for the adoption of digitalization in Indian small and medium enterprises

- A non-ideal hybridization issue for vertical TFET-based dielectric-modulated biosensor

- Optimizing data retrieval for enhanced data integrity verification in cloud environments

- Performance analysis of nonlinear crosstalk of WDM systems using modulation schemes criteria

- Nonlinear finite-element analysis of RC beams with various opening near supports

- Thermal analysis of Fe3O4–Cu/water over a cone: a fractional Maxwell model

- Radial–axial runner blade design using the coordinate slice technique

- Theoretical and experimental comparison between straight and curved continuous box girders

- Effect of the reinforcement ratio on the mechanical behaviour of textile-reinforced concrete composite: Experiment and numerical modeling

- Experimental and numerical investigation on composite beam–column joint connection behavior using different types of connection schemes

- Enhanced performance and robustness in anti-lock brake systems using barrier function-based integral sliding mode control

- Evaluation of the creep strength of samples produced by fused deposition modeling

- A combined feedforward-feedback controller design for nonlinear systems

- Effect of adjacent structures on footing settlement for different multi-building arrangements

- Analyzing the impact of curved tracks on wheel flange thickness reduction in railway systems

- Review Articles

- Mechanical and smart properties of cement nanocomposites containing nanomaterials: A brief review

- Applications of nanotechnology and nanoproduction techniques

- Relationship between indoor environmental quality and guests’ comfort and satisfaction at green hotels: A comprehensive review

- Communication

- Techniques to mitigate the admission of radon inside buildings

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy”

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part II

- Integrated fuzzy logic and multicriteria decision model methods for selecting suitable sites for wastewater treatment plant: A case study in the center of Basrah, Iraq

- Physical and mechanical response of porous metals composites with nano-natural additives

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part II

- New recycling method of lubricant oil and the effect on the viscosity and viscous shear as an environmentally friendly

- Identify the effect of Fe2O3 nanoparticles on mechanical and microstructural characteristics of aluminum matrix composite produced by powder metallurgy technique

- Static behavior of piled raft foundation in clay

- Ultra-low-power CMOS ring oscillator with minimum power consumption of 2.9 pW using low-voltage biasing technique

- Using ANN for well type identifying and increasing production from Sa’di formation of Halfaya oil field – Iraq

- Optimizing the performance of concrete tiles using nano-papyrus and carbon fibers

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part II

- Comparative the effect of distribution transformer coil shape on electromagnetic forces and their distribution using the FEM

- The complex of Weyl module in free characteristic in the event of a partition (7,5,3)

- Restrained captive domination number

- Experimental study of improving hot mix asphalt reinforced with carbon fibers

- Asphalt binder modified with recycled tyre rubber

- Thermal performance of radiant floor cooling with phase change material for energy-efficient buildings

- Surveying the prediction of risks in cryptocurrency investments using recurrent neural networks

- A deep reinforcement learning framework to modify LQR for an active vibration control applied to 2D building models

- Evaluation of mechanically stabilized earth retaining walls for different soil–structure interaction methods: A review

- Assessment of heat transfer in a triangular duct with different configurations of ribs using computational fluid dynamics

- Sulfate removal from wastewater by using waste material as an adsorbent

- Experimental investigation on strengthening lap joints subjected to bending in glulam timber beams using CFRP sheets

- A study of the vibrations of a rotor bearing suspended by a hybrid spring system of shape memory alloys

- Stability analysis of Hub dam under rapid drawdown

- Developing ANFIS-FMEA model for assessment and prioritization of potential trouble factors in Iraqi building projects

- Numerical and experimental comparison study of piled raft foundation

- Effect of asphalt modified with waste engine oil on the durability properties of hot asphalt mixtures with reclaimed asphalt pavement

- Hydraulic model for flood inundation in Diyala River Basin using HEC-RAS, PMP, and neural network

- Numerical study on discharge capacity of piano key side weir with various ratios of the crest length to the width

- The optimal allocation of thyristor-controlled series compensators for enhancement HVAC transmission lines Iraqi super grid by using seeker optimization algorithm

- Numerical and experimental study of the impact on aerodynamic characteristics of the NACA0012 airfoil

- Effect of nano-TiO2 on physical and rheological properties of asphalt cement

- Performance evolution of novel palm leaf powder used for enhancing hot mix asphalt

- Performance analysis, evaluation, and improvement of selected unsignalized intersection using SIDRA software – Case study

- Flexural behavior of RC beams externally reinforced with CFRP composites using various strategies

- Influence of fiber types on the properties of the artificial cold-bonded lightweight aggregates

- Experimental investigation of RC beams strengthened with externally bonded BFRP composites

- Generalized RKM methods for solving fifth-order quasi-linear fractional partial differential equation

- An experimental and numerical study investigating sediment transport position in the bed of sewer pipes in Karbala

- Role of individual component failure in the performance of a 1-out-of-3 cold standby system: A Markov model approach

- Implementation for the cases (5, 4) and (5, 4)/(2, 0)

- Center group actions and related concepts

- Experimental investigation of the effect of horizontal construction joints on the behavior of deep beams

- Deletion of a vertex in even sum domination

- Deep learning techniques in concrete powder mix designing

- Effect of loading type in concrete deep beam with strut reinforcement

- Studying the effect of using CFRP warping on strength of husk rice concrete columns

- Parametric analysis of the influence of climatic factors on the formation of traditional buildings in the city of Al Najaf

- Suitability location for landfill using a fuzzy-GIS model: A case study in Hillah, Iraq

- Hybrid approach for cost estimation of sustainable building projects using artificial neural networks

- Assessment of indirect tensile stress and tensile–strength ratio and creep compliance in HMA mixes with micro-silica and PMB

- Density functional theory to study stopping power of proton in water, lung, bladder, and intestine

- A review of single flow, flow boiling, and coating microchannel studies

- Effect of GFRP bar length on the flexural behavior of hybrid concrete beams strengthened with NSM bars

- Exploring the impact of parameters on flow boiling heat transfer in microchannels and coated microtubes: A comprehensive review

- Crumb rubber modification for enhanced rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures

- Special Issue: AESMT-6

- Design of a new sorting colors system based on PLC, TIA portal, and factory I/O programs

- Forecasting empirical formula for suspended sediment load prediction at upstream of Al-Kufa barrage, Kufa City, Iraq

- Optimization and characterization of sustainable geopolymer mortars based on palygorskite clay, water glass, and sodium hydroxide

- Sediment transport modelling upstream of Al Kufa Barrage

- Study of energy loss, range, and stopping time for proton in germanium and copper materials

- Effect of internal and external recycle ratios on the nutrient removal efficiency of anaerobic/anoxic/oxic (VIP) wastewater treatment plant

- Enhancing structural behaviour of polypropylene fibre concrete columns longitudinally reinforced with fibreglass bars

- Sustainable road paving: Enhancing concrete paver blocks with zeolite-enhanced cement

- Evaluation of the operational performance of Karbala waste water treatment plant under variable flow using GPS-X model

- Design and simulation of photonic crystal fiber for highly sensitive chemical sensing applications

- Optimization and design of a new column sequencing for crude oil distillation at Basrah refinery

- Inductive 3D numerical modelling of the tibia bone using MRI to examine von Mises stress and overall deformation

- An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol and Hill Cipher

- Experimental investigation of generating superheated steam using a parabolic dish with a cylindrical cavity receiver: A case study

- Effect of surface roughness on the interface behavior of clayey soils

- Investigated of the optical properties for SiO2 by using Lorentz model

- Measurements of induced vibrations due to steel pipe pile driving in Al-Fao soil: Effect of partial end closure

- Experimental and numerical studies of ballistic resistance of hybrid sandwich composite body armor

- Evaluation of clay layer presence on shallow foundation settlement in dry sand under an earthquake

- Optimal design of mechanical performances of asphalt mixtures comprising nano-clay additives

- Advancing seismic performance: Isolators, TMDs, and multi-level strategies in reinforced concrete buildings

- Predicted evaporation in Basrah using artificial neural networks

- Energy management system for a small town to enhance quality of life

- Numerical study on entropy minimization in pipes with helical airfoil and CuO nanoparticle integration

- Equations and methodologies of inlet drainage system discharge coefficients: A review

- Thermal buckling analysis for hybrid and composite laminated plate by using new displacement function

- Investigation into the mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight mortar using commercial beads or recycled expanded polystyrene

- Experimental and theoretical analysis of single-jet column and concrete column using double-jet grouting technique applied at Al-Rashdia site

- The impact of incorporating waste materials on the mechanical and physical characteristics of tile adhesive materials

- Seismic resilience: Innovations in structural engineering for earthquake-prone areas

- Automatic human identification using fingerprint images based on Gabor filter and SIFT features fusion

- Performance of GRKM-method for solving classes of ordinary and partial differential equations of sixth-orders

- Visible light-boosted photodegradation activity of Ag–AgVO3/Zn0.5Mn0.5Fe2O4 supported heterojunctions for effective degradation of organic contaminates

- Production of sustainable concrete with treated cement kiln dust and iron slag waste aggregate

- Key effects on the structural behavior of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete-ribbed slabs: A review

- A comparative analysis of the energy dissipation efficiency of various piano key weir types

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part II

- Variability in road surface temperature in urban road network – A case study making use of mobile measurements

- Special Issue: BCEE5-2023

- Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt mixtures rejuvenated with waste engine oil to resist rutting deformation

- Assessment of potential resistance to moisture damage and fatigue cracks of asphalt mixture modified with ground granulated blast furnace slag

- Investigating seismic response in adjacent structures: A study on the impact of buildings’ orientation and distance considering soil–structure interaction

- Improvement of porosity of mortar using polyethylene glycol pre-polymer-impregnated mortar

- Three-dimensional analysis of steel beam-column bolted connections

- Assessment of agricultural drought in Iraq employing Landsat and MODIS imagery

- Performance evaluation of grouted porous asphalt concrete

- Optimization of local modified metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete by Taguchi method

- Effect of waste tire products on some characteristics of roller-compacted concrete

- Studying the lateral displacement of retaining wall supporting sandy soil under dynamic loads

- Seismic performance evaluation of concrete buttress dram (Dynamic linear analysis)

- Behavior of soil reinforced with micropiles

- Possibility of production high strength lightweight concrete containing organic waste aggregate and recycled steel fibers

- An investigation of self-sensing and mechanical properties of smart engineered cementitious composites reinforced with functional materials

- Forecasting changes in precipitation and temperatures of a regional watershed in Northern Iraq using LARS-WG model

- Experimental investigation of dynamic soil properties for modeling energy-absorbing layers

- Numerical investigation of the effect of longitudinal steel reinforcement ratio on the ductility of concrete beams

- An experimental study on the tensile properties of reinforced asphalt pavement

- Self-sensing behavior of hot asphalt mixture with steel fiber-based additive

- Behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete deep beams reinforced by basalt fibers

- Optimizing asphalt binder performance with various PET types

- Investigation of the hydraulic characteristics and homogeneity of the microstructure of the air voids in the sustainable rigid pavement

- Enhanced biogas production from municipal solid waste via digestion with cow manure: A case study

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part I

- Preparation and investigation of cobalt nanoparticles by laser ablation: Structure, linear, and nonlinear optical properties

- Seismic analysis of RC building with plan irregularity in Baghdad/Iraq to obtain the optimal behavior

- The effect of urban environment on large-scale path loss model’s main parameters for mmWave 5G mobile network in Iraq

- Formatting a questionnaire for the quality control of river bank roads

- Vibration suppression of smart composite beam using model predictive controller

- Machine learning-based compressive strength estimation in nanomaterial-modified lightweight concrete

- In-depth analysis of critical factors affecting Iraqi construction projects performance

- Behavior of container berth structure under the influence of environmental and operational loads

- Energy absorption and impact response of ballistic resistance laminate

- Effect of water-absorbent polymer balls in internal curing on punching shear behavior of bubble slabs

- Effect of surface roughness on interface shear strength parameters of sandy soils

- Evaluating the interaction for embedded H-steel section in normal concrete under monotonic and repeated loads

- Estimation of the settlement of pile head using ANN and multivariate linear regression based on the results of load transfer method

- Enhancing communication: Deep learning for Arabic sign language translation

- A review of recent studies of both heat pipe and evaporative cooling in passive heat recovery

- Effect of nano-silica on the mechanical properties of LWC

- An experimental study of some mechanical properties and absorption for polymer-modified cement mortar modified with superplasticizer

- Digital beamforming enhancement with LSTM-based deep learning for millimeter wave transmission

- Developing an efficient planning process for heritage buildings maintenance in Iraq

- Design and optimization of two-stage controller for three-phase multi-converter/multi-machine electric vehicle

- Evaluation of microstructure and mechanical properties of Al1050/Al2O3/Gr composite processed by forming operation ECAP

- Calculations of mass stopping power and range of protons in organic compounds (CH3OH, CH2O, and CO2) at energy range of 0.01–1,000 MeV

- Investigation of in vitro behavior of composite coating hydroxyapatite-nano silver on 316L stainless steel substrate by electrophoretic technic for biomedical tools

- A review: Enhancing tribological properties of journal bearings composite materials

- Improvements in the randomness and security of digital currency using the photon sponge hash function through Maiorana–McFarland S-box replacement

- Design a new scheme for image security using a deep learning technique of hierarchical parameters

- Special Issue: ICES 2023

- Comparative geotechnical analysis for ultimate bearing capacity of precast concrete piles using cone resistance measurements

- Visualizing sustainable rainwater harvesting: A case study of Karbala Province

- Geogrid reinforcement for improving bearing capacity and stability of square foundations

- Evaluation of the effluent concentrations of Karbala wastewater treatment plant using reliability analysis

- Adsorbent made with inexpensive, local resources

- Effect of drain pipes on seepage and slope stability through a zoned earth dam

- Sediment accumulation in an 8 inch sewer pipe for a sample of various particles obtained from the streets of Karbala city, Iraq

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part I

- Analyzing the impact of transfer learning on explanation accuracy in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems

- Effect of scale factor on the dynamic response of frame foundations

- Improving multi-object detection and tracking with deep learning, DeepSORT, and frame cancellation techniques

- The impact of using prestressed CFRP bars on the development of flexural strength

- Assessment of surface hardness and impact strength of denture base resins reinforced with silver–titanium dioxide and silver–zirconium dioxide nanoparticles: In vitro study

- A data augmentation approach to enhance breast cancer detection using generative adversarial and artificial neural networks

- Modification of the 5D Lorenz chaotic map with fuzzy numbers for video encryption in cloud computing

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part I

- Evaluation of static bending caused damage of glass-fiber composite structure using terahertz inspection

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Methodology of automated quality management

- Influence of vibratory conveyor design parameters on the trough motion and the self-synchronization of inertial vibrators

- Application of finite element method in industrial design, example of an electric motorcycle design project

- Correlative evaluation of the corrosion resilience and passivation properties of zinc and aluminum alloys in neutral chloride and acid-chloride solutions

- Will COVID “encourage” B2B and data exchange engineering in logistic firms?

- Influence of unsupported sleepers on flange climb derailment of two freight wagons

- A hybrid detection algorithm for 5G OTFS waveform for 64 and 256 QAM with Rayleigh and Rician channels

- Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy

- Exploring the potential of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for transportation

- Impact of insulation on energy consumption and CO2 emissions in high-rise commercial buildings at various climate zones

- Advanced autopilot design with extremum-seeking control for aircraft control

- Adaptive multidimensional trust-based recommendation model for peer to peer applications

- Effects of CFRP sheets on the flexural behavior of high-strength concrete beam

- Enhancing urban sustainability through industrial synergy: A multidisciplinary framework for integrating sustainable industrial practices within urban settings – The case of Hamadan industrial city

- Advanced vibrant controller results of an energetic framework structure

- Application of the Taguchi method and RSM for process parameter optimization in AWSJ machining of CFRP composite-based orthopedic implants

- Improved correlation of soil modulus with SPT N values

- Technologies for high-temperature batch annealing of grain-oriented electrical steel: An overview

- Assessing the need for the adoption of digitalization in Indian small and medium enterprises

- A non-ideal hybridization issue for vertical TFET-based dielectric-modulated biosensor

- Optimizing data retrieval for enhanced data integrity verification in cloud environments

- Performance analysis of nonlinear crosstalk of WDM systems using modulation schemes criteria

- Nonlinear finite-element analysis of RC beams with various opening near supports

- Thermal analysis of Fe3O4–Cu/water over a cone: a fractional Maxwell model

- Radial–axial runner blade design using the coordinate slice technique

- Theoretical and experimental comparison between straight and curved continuous box girders

- Effect of the reinforcement ratio on the mechanical behaviour of textile-reinforced concrete composite: Experiment and numerical modeling

- Experimental and numerical investigation on composite beam–column joint connection behavior using different types of connection schemes

- Enhanced performance and robustness in anti-lock brake systems using barrier function-based integral sliding mode control

- Evaluation of the creep strength of samples produced by fused deposition modeling

- A combined feedforward-feedback controller design for nonlinear systems

- Effect of adjacent structures on footing settlement for different multi-building arrangements

- Analyzing the impact of curved tracks on wheel flange thickness reduction in railway systems

- Review Articles

- Mechanical and smart properties of cement nanocomposites containing nanomaterials: A brief review

- Applications of nanotechnology and nanoproduction techniques

- Relationship between indoor environmental quality and guests’ comfort and satisfaction at green hotels: A comprehensive review

- Communication

- Techniques to mitigate the admission of radon inside buildings

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy”

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part II

- Integrated fuzzy logic and multicriteria decision model methods for selecting suitable sites for wastewater treatment plant: A case study in the center of Basrah, Iraq

- Physical and mechanical response of porous metals composites with nano-natural additives

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part II

- New recycling method of lubricant oil and the effect on the viscosity and viscous shear as an environmentally friendly

- Identify the effect of Fe2O3 nanoparticles on mechanical and microstructural characteristics of aluminum matrix composite produced by powder metallurgy technique

- Static behavior of piled raft foundation in clay

- Ultra-low-power CMOS ring oscillator with minimum power consumption of 2.9 pW using low-voltage biasing technique

- Using ANN for well type identifying and increasing production from Sa’di formation of Halfaya oil field – Iraq

- Optimizing the performance of concrete tiles using nano-papyrus and carbon fibers

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part II

- Comparative the effect of distribution transformer coil shape on electromagnetic forces and their distribution using the FEM

- The complex of Weyl module in free characteristic in the event of a partition (7,5,3)

- Restrained captive domination number

- Experimental study of improving hot mix asphalt reinforced with carbon fibers

- Asphalt binder modified with recycled tyre rubber

- Thermal performance of radiant floor cooling with phase change material for energy-efficient buildings

- Surveying the prediction of risks in cryptocurrency investments using recurrent neural networks

- A deep reinforcement learning framework to modify LQR for an active vibration control applied to 2D building models

- Evaluation of mechanically stabilized earth retaining walls for different soil–structure interaction methods: A review

- Assessment of heat transfer in a triangular duct with different configurations of ribs using computational fluid dynamics

- Sulfate removal from wastewater by using waste material as an adsorbent

- Experimental investigation on strengthening lap joints subjected to bending in glulam timber beams using CFRP sheets

- A study of the vibrations of a rotor bearing suspended by a hybrid spring system of shape memory alloys

- Stability analysis of Hub dam under rapid drawdown

- Developing ANFIS-FMEA model for assessment and prioritization of potential trouble factors in Iraqi building projects

- Numerical and experimental comparison study of piled raft foundation

- Effect of asphalt modified with waste engine oil on the durability properties of hot asphalt mixtures with reclaimed asphalt pavement

- Hydraulic model for flood inundation in Diyala River Basin using HEC-RAS, PMP, and neural network

- Numerical study on discharge capacity of piano key side weir with various ratios of the crest length to the width

- The optimal allocation of thyristor-controlled series compensators for enhancement HVAC transmission lines Iraqi super grid by using seeker optimization algorithm

- Numerical and experimental study of the impact on aerodynamic characteristics of the NACA0012 airfoil

- Effect of nano-TiO2 on physical and rheological properties of asphalt cement

- Performance evolution of novel palm leaf powder used for enhancing hot mix asphalt

- Performance analysis, evaluation, and improvement of selected unsignalized intersection using SIDRA software – Case study

- Flexural behavior of RC beams externally reinforced with CFRP composites using various strategies

- Influence of fiber types on the properties of the artificial cold-bonded lightweight aggregates

- Experimental investigation of RC beams strengthened with externally bonded BFRP composites

- Generalized RKM methods for solving fifth-order quasi-linear fractional partial differential equation

- An experimental and numerical study investigating sediment transport position in the bed of sewer pipes in Karbala

- Role of individual component failure in the performance of a 1-out-of-3 cold standby system: A Markov model approach

- Implementation for the cases (5, 4) and (5, 4)/(2, 0)

- Center group actions and related concepts

- Experimental investigation of the effect of horizontal construction joints on the behavior of deep beams

- Deletion of a vertex in even sum domination

- Deep learning techniques in concrete powder mix designing

- Effect of loading type in concrete deep beam with strut reinforcement

- Studying the effect of using CFRP warping on strength of husk rice concrete columns

- Parametric analysis of the influence of climatic factors on the formation of traditional buildings in the city of Al Najaf

- Suitability location for landfill using a fuzzy-GIS model: A case study in Hillah, Iraq

- Hybrid approach for cost estimation of sustainable building projects using artificial neural networks

- Assessment of indirect tensile stress and tensile–strength ratio and creep compliance in HMA mixes with micro-silica and PMB

- Density functional theory to study stopping power of proton in water, lung, bladder, and intestine

- A review of single flow, flow boiling, and coating microchannel studies

- Effect of GFRP bar length on the flexural behavior of hybrid concrete beams strengthened with NSM bars

- Exploring the impact of parameters on flow boiling heat transfer in microchannels and coated microtubes: A comprehensive review

- Crumb rubber modification for enhanced rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures

- Special Issue: AESMT-6

- Design of a new sorting colors system based on PLC, TIA portal, and factory I/O programs

- Forecasting empirical formula for suspended sediment load prediction at upstream of Al-Kufa barrage, Kufa City, Iraq

- Optimization and characterization of sustainable geopolymer mortars based on palygorskite clay, water glass, and sodium hydroxide

- Sediment transport modelling upstream of Al Kufa Barrage

- Study of energy loss, range, and stopping time for proton in germanium and copper materials

- Effect of internal and external recycle ratios on the nutrient removal efficiency of anaerobic/anoxic/oxic (VIP) wastewater treatment plant

- Enhancing structural behaviour of polypropylene fibre concrete columns longitudinally reinforced with fibreglass bars

- Sustainable road paving: Enhancing concrete paver blocks with zeolite-enhanced cement

- Evaluation of the operational performance of Karbala waste water treatment plant under variable flow using GPS-X model

- Design and simulation of photonic crystal fiber for highly sensitive chemical sensing applications

- Optimization and design of a new column sequencing for crude oil distillation at Basrah refinery

- Inductive 3D numerical modelling of the tibia bone using MRI to examine von Mises stress and overall deformation

- An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol and Hill Cipher

- Experimental investigation of generating superheated steam using a parabolic dish with a cylindrical cavity receiver: A case study

- Effect of surface roughness on the interface behavior of clayey soils

- Investigated of the optical properties for SiO2 by using Lorentz model

- Measurements of induced vibrations due to steel pipe pile driving in Al-Fao soil: Effect of partial end closure

- Experimental and numerical studies of ballistic resistance of hybrid sandwich composite body armor

- Evaluation of clay layer presence on shallow foundation settlement in dry sand under an earthquake

- Optimal design of mechanical performances of asphalt mixtures comprising nano-clay additives

- Advancing seismic performance: Isolators, TMDs, and multi-level strategies in reinforced concrete buildings

- Predicted evaporation in Basrah using artificial neural networks

- Energy management system for a small town to enhance quality of life

- Numerical study on entropy minimization in pipes with helical airfoil and CuO nanoparticle integration

- Equations and methodologies of inlet drainage system discharge coefficients: A review

- Thermal buckling analysis for hybrid and composite laminated plate by using new displacement function

- Investigation into the mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight mortar using commercial beads or recycled expanded polystyrene

- Experimental and theoretical analysis of single-jet column and concrete column using double-jet grouting technique applied at Al-Rashdia site

- The impact of incorporating waste materials on the mechanical and physical characteristics of tile adhesive materials

- Seismic resilience: Innovations in structural engineering for earthquake-prone areas

- Automatic human identification using fingerprint images based on Gabor filter and SIFT features fusion

- Performance of GRKM-method for solving classes of ordinary and partial differential equations of sixth-orders

- Visible light-boosted photodegradation activity of Ag–AgVO3/Zn0.5Mn0.5Fe2O4 supported heterojunctions for effective degradation of organic contaminates

- Production of sustainable concrete with treated cement kiln dust and iron slag waste aggregate

- Key effects on the structural behavior of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete-ribbed slabs: A review

- A comparative analysis of the energy dissipation efficiency of various piano key weir types

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part II

- Variability in road surface temperature in urban road network – A case study making use of mobile measurements

- Special Issue: BCEE5-2023

- Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt mixtures rejuvenated with waste engine oil to resist rutting deformation

- Assessment of potential resistance to moisture damage and fatigue cracks of asphalt mixture modified with ground granulated blast furnace slag

- Investigating seismic response in adjacent structures: A study on the impact of buildings’ orientation and distance considering soil–structure interaction

- Improvement of porosity of mortar using polyethylene glycol pre-polymer-impregnated mortar

- Three-dimensional analysis of steel beam-column bolted connections

- Assessment of agricultural drought in Iraq employing Landsat and MODIS imagery

- Performance evaluation of grouted porous asphalt concrete

- Optimization of local modified metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete by Taguchi method

- Effect of waste tire products on some characteristics of roller-compacted concrete

- Studying the lateral displacement of retaining wall supporting sandy soil under dynamic loads

- Seismic performance evaluation of concrete buttress dram (Dynamic linear analysis)

- Behavior of soil reinforced with micropiles

- Possibility of production high strength lightweight concrete containing organic waste aggregate and recycled steel fibers

- An investigation of self-sensing and mechanical properties of smart engineered cementitious composites reinforced with functional materials

- Forecasting changes in precipitation and temperatures of a regional watershed in Northern Iraq using LARS-WG model

- Experimental investigation of dynamic soil properties for modeling energy-absorbing layers

- Numerical investigation of the effect of longitudinal steel reinforcement ratio on the ductility of concrete beams

- An experimental study on the tensile properties of reinforced asphalt pavement

- Self-sensing behavior of hot asphalt mixture with steel fiber-based additive

- Behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete deep beams reinforced by basalt fibers

- Optimizing asphalt binder performance with various PET types

- Investigation of the hydraulic characteristics and homogeneity of the microstructure of the air voids in the sustainable rigid pavement

- Enhanced biogas production from municipal solid waste via digestion with cow manure: A case study

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part I

- Preparation and investigation of cobalt nanoparticles by laser ablation: Structure, linear, and nonlinear optical properties

- Seismic analysis of RC building with plan irregularity in Baghdad/Iraq to obtain the optimal behavior

- The effect of urban environment on large-scale path loss model’s main parameters for mmWave 5G mobile network in Iraq

- Formatting a questionnaire for the quality control of river bank roads

- Vibration suppression of smart composite beam using model predictive controller

- Machine learning-based compressive strength estimation in nanomaterial-modified lightweight concrete

- In-depth analysis of critical factors affecting Iraqi construction projects performance

- Behavior of container berth structure under the influence of environmental and operational loads

- Energy absorption and impact response of ballistic resistance laminate

- Effect of water-absorbent polymer balls in internal curing on punching shear behavior of bubble slabs

- Effect of surface roughness on interface shear strength parameters of sandy soils

- Evaluating the interaction for embedded H-steel section in normal concrete under monotonic and repeated loads

- Estimation of the settlement of pile head using ANN and multivariate linear regression based on the results of load transfer method

- Enhancing communication: Deep learning for Arabic sign language translation

- A review of recent studies of both heat pipe and evaporative cooling in passive heat recovery

- Effect of nano-silica on the mechanical properties of LWC

- An experimental study of some mechanical properties and absorption for polymer-modified cement mortar modified with superplasticizer

- Digital beamforming enhancement with LSTM-based deep learning for millimeter wave transmission

- Developing an efficient planning process for heritage buildings maintenance in Iraq

- Design and optimization of two-stage controller for three-phase multi-converter/multi-machine electric vehicle

- Evaluation of microstructure and mechanical properties of Al1050/Al2O3/Gr composite processed by forming operation ECAP

- Calculations of mass stopping power and range of protons in organic compounds (CH3OH, CH2O, and CO2) at energy range of 0.01–1,000 MeV

- Investigation of in vitro behavior of composite coating hydroxyapatite-nano silver on 316L stainless steel substrate by electrophoretic technic for biomedical tools

- A review: Enhancing tribological properties of journal bearings composite materials

- Improvements in the randomness and security of digital currency using the photon sponge hash function through Maiorana–McFarland S-box replacement

- Design a new scheme for image security using a deep learning technique of hierarchical parameters

- Special Issue: ICES 2023

- Comparative geotechnical analysis for ultimate bearing capacity of precast concrete piles using cone resistance measurements

- Visualizing sustainable rainwater harvesting: A case study of Karbala Province

- Geogrid reinforcement for improving bearing capacity and stability of square foundations

- Evaluation of the effluent concentrations of Karbala wastewater treatment plant using reliability analysis

- Adsorbent made with inexpensive, local resources

- Effect of drain pipes on seepage and slope stability through a zoned earth dam

- Sediment accumulation in an 8 inch sewer pipe for a sample of various particles obtained from the streets of Karbala city, Iraq

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part I

- Analyzing the impact of transfer learning on explanation accuracy in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems

- Effect of scale factor on the dynamic response of frame foundations

- Improving multi-object detection and tracking with deep learning, DeepSORT, and frame cancellation techniques

- The impact of using prestressed CFRP bars on the development of flexural strength

- Assessment of surface hardness and impact strength of denture base resins reinforced with silver–titanium dioxide and silver–zirconium dioxide nanoparticles: In vitro study

- A data augmentation approach to enhance breast cancer detection using generative adversarial and artificial neural networks

- Modification of the 5D Lorenz chaotic map with fuzzy numbers for video encryption in cloud computing

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part I

- Evaluation of static bending caused damage of glass-fiber composite structure using terahertz inspection