Abstract

Background

JS-K is a nitric oxide (NO)-releasing prodrug of the O2-arylated diazeniumdiolate group that shows pronounced cytotoxicity and antitumor properties in numerous cancer models, including in vitro as well as in vivo. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induce carcinogenesis by altering the redox status, causing increment in vulnerability to oxidative stress.

Material and methods

To determine the effect of JS-K, a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-activated NO-donor prodrug, on the induction of ROS accumulation, proliferation, and apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells, we measured the changes of cell proliferation, apoptosis, ROS growth, and initiation of the mitochondrial signaling pathway before and after JS-K treatment.

Results

In vitro, dose- and time-dependent development of renal carcinoma cells were controlled for JS-K, and JS-K also triggered ROS aggregation and cell apoptosis. Treatment with JS-K induces the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bak and Bax) and decrease the number of anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2). In fact, JS-K-induced apoptosis was reversed by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, and oxidized glutathione, a pro-oxidant, improved JS-K-induced apoptosis. Finally, we demonstrated that in renal carcinoma cells, JS-K improved the chemosensitivity of doxorubicin.

Conclusion

Our data indicate that JS-K-released NO induce apoptosis of renal carcinoma cells by increasing ROS levels.

1 Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a prevalent urogenital system malignant tumor with an incidence of approximately 5–10 per 100,000, representing 2–3% of all adult tumors [1], with one of the highest incidences of urological malignancies. According to the prediction by the American Cancer Society of the United States, almost 73,800 new cases of RCC and nearly 14,700 associated demises were reported in 2019. [2]. RCC is often asymptomatic in its preliminary phases, in that the illness frequently evolves at the time of diagnosis into final stages and exactly 25–30% of patients possess metastatic RCC at diagnosis. Various methods of treating RCC, for instance, conventional immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and radical surveillance, are currently available. Around 40% of patients, regrettably, are immune to radiation therapy and conventional chemotherapy. Such individuals may suffer systemic recurrence, resulting in high toxicity and poor treatment response [3], and a severe effect on disease-related death, with a very low 5-year survival rate (only 10–12%) [4]. Yet more studies on the mechanisms involved in the growth and advancement of RCC are thus need to identify new therapeutic targets.

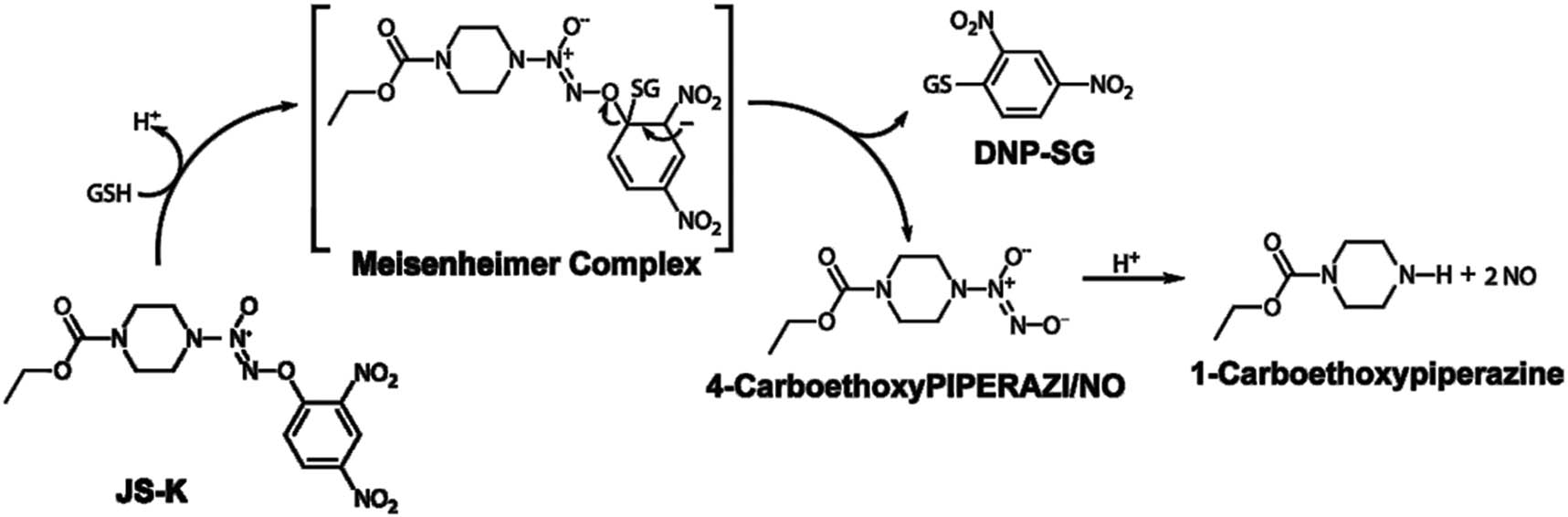

O2-(2,4-Nitrophenyl)1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl) piperazine-1-yl] diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (JS-K, C13H16N6O8, AS-No: 205432-128), a diazeniumdiolate-based nitric oxide (NO)-donor prodrug, is a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-activated compound that can produce more intracellular NO levels (Figure 1) [5]. The optimal activity of JS-K uniquely requires GSTs, with overexpression of GST, and JS-K can produce higher intracellular concentrations of cytotoxic inside tumor cells, thereby reducing the viability of tumor cell. JS-K has no apparent toxicity in normal cells and shows antitumor properties both in vivo and in vitro [6]. In the recent study, the level of intercellular ROS was regulated by NO via outputting numerous responsive nitrogen types (RNS) [7]. A recent study showed that JS-K was extremely effective against nonsmall-cell lung cancer cells through elevation of the basal levels of ROS [8]. JS-K has also been stated to have antitumor activity against prostate cancer cells [9,10], bladder cancer cells [11], Ovarian cancer [12], gastric cancer [13], and nonsmall-cell lung cancer [14]. However, the direct effect of JS-K-on proliferation and apoptosis of renal carcinoma cells and the role of ROS have not been characterized. The aim of this study is to explore whether JS-K also has cytotoxic effects on human renal carcinoma cells and to evaluate available mechanisms of ROS.

The structure of JS-K and release of NO.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and cell culture

JS-K was obtained from Biotechnology, Inc. of Santa Cruz (CA). Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology purchased N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) (Shanghai, China). The ACHN and A498 human renal carcinoma cell lines were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. ACHN and A498 cells were cultivated in DMEM medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) and PRMI-1640 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) separately, with 11% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37°C in the air with 5% carbon.

2.2 Cell proliferation assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan) assay assessed the proliferation of ACHN and A498 cells. Cells (1 × 103/well) were plated for 24 h on 97-well plates and treated for 12, 24, and 48 h using JS-K (5 μM). The Cell Counting Kit-8 (10 μL/per well) reagent was then included in to culture intermediate and incubated for 120 min at 37°C. The microplate reader measured the absorbance of each well at 450 nm (BioTek Instruments, Inc., US). Almost every experiment was performed in triplicate, and the average values were calculated.

2.3 Apoptosis study

Apoptosis was detected using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I. The cells were incubated in a conditioned medium by JS-K, then collected, separated by a centrifuge tube, and nurtured with Annexin V-FITC and PI for minutes at room temperature in the darkness. Then, the stained cells were evaluated by flow cytometry within 60 min.

2.4 Caspase-Glo 3/7 assays

We used the caspase-Glo 3/7 assay to gauge the exercise of caspase-3/7 following the manufacturer’s protocol to further analyze cell apoptosis. In short, JS-K treated cells and conditioned medium were grouped into 97-well dishes (Corning, USA). Then, each well was added with an equal volume of caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the darkness. A luminometer was used to obtain the luminescence data (Berthold Sirius L, Germany).

2.5 Measurement of intracellular ROS

In accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, we used the Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime) via flow cytometry to identify the accumulation of ROS. Cells were shortly treated with JS-K (1, 2, and 5 μM) for 6 h, collected, and centrifuged in a serum-free DCFH-DA reagent-containing medium. However, they were incubated in the dark for 20 min at 37°C. At the excitation source at 489 nm and emission at 526 nm, the DCF fluorescence energy was calculated.

2.6 RNS assay

In this study, nitrite ion (NO2-) was described as RNS, as well as the levels of RNS were quantified as per the manufacturer’s instructions using a Nitrite Assay Kit (Beyotime).

2.7 Superoxide measurement

The superoxide variable was determined using a Superoxide Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were treated using JS-K (1, 2, and 5 μM) for 6 h, and then, the superoxide detection reagent (200 μL/well) was randomly added and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. In a 96-well plate reader, the solution was read at 450 nm (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The superoxide variable was determined using a Superoxide Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were treated using JS-K 9 for 6 h, and then, the superoxide detection reagent (200 μL/well) was randomly added and incubated for 20 min at normal temperature. In a 96-well plate reader, the solution was read at 450 nm (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

2.8 Glutathione content assay

Renal carcinoma cells were incubated at 6 h JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) levels. Cells were implanted onto six-well plates, with a density of 3–105 cells (Millipore Scepter TM) per well. There had been two consecutive cycles of precipitation of the cells. The supernatant was extracted by ultracentrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min. The quantity of glutathione or glutathione disulfide (GSSG) was calculated by GSH and GSSG assay kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.9 Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Cells were grouped at 3–105 cells/well in seven-well plates and subjected to extreme JS-K (0, 1, 3, and 7 μM) concentrations for 3 h. The JC-1 mitochondrial membrane possibility assay kit (Beyotime) is used to evaluate the extent of mitochondrial membrane potential as per the producer’s protocols.

2.10 Measurement of ATP production

Cells were incubated for 6 h with JS-K, and afterward, ATP concentrations were calculated using ATP Assay Kit as instructed by producers.

2.11 Western blot analysis

Renal carcinoma cells were incubated with a buffer (Beyotime) in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethyl sulphonylfluoride (PMSF; Beyotime). Renal carcinoma cells treated with JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) were isolated by electrophoresis of sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel. Renal carcinoma lysates were subsequently transferred to the difluoride membranes of polyvinylidene. Bak (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Bax protein (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Bcl-2 (Cell Signaling Technology), PARP protein receptors (Cell Signaling Technology), and GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were transfected into the neurons and distilled overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then tested with an IgG-HRP supplementary goat-anti-rabbit antibody for 30 min (EarthOx, USA).

2.12 Statistical study

All tests were conducted at least three times and at least triplicated each time. The results have been represented as average ± SD. The one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0. LSD(L) examined the differences; a big variation was inferred for P < 0.05, and an exceedingly substantial variance for P < 0.01 was inferred.

-

Ethical approval: The experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Huizhou.

3 Results

3.1 JS-K suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells

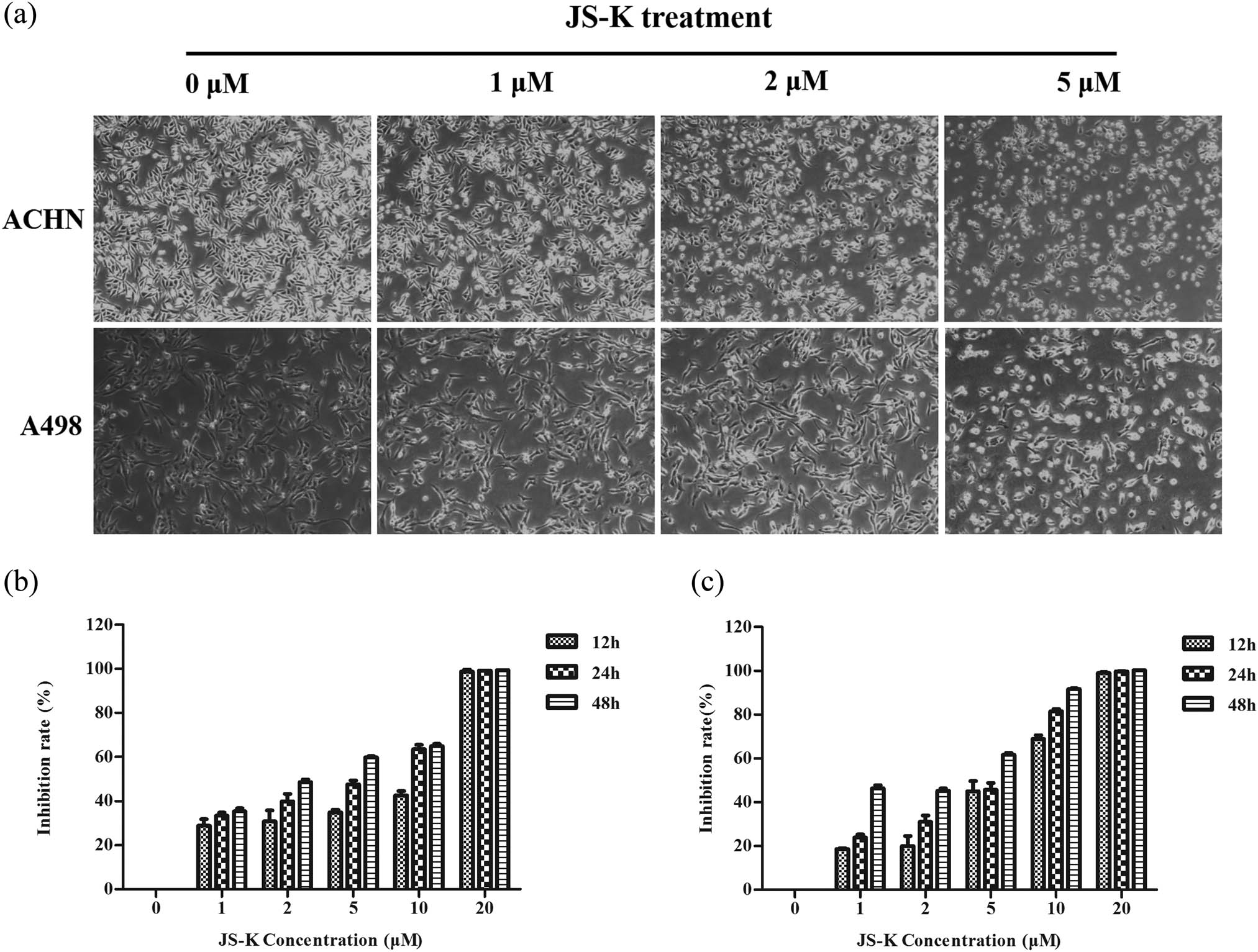

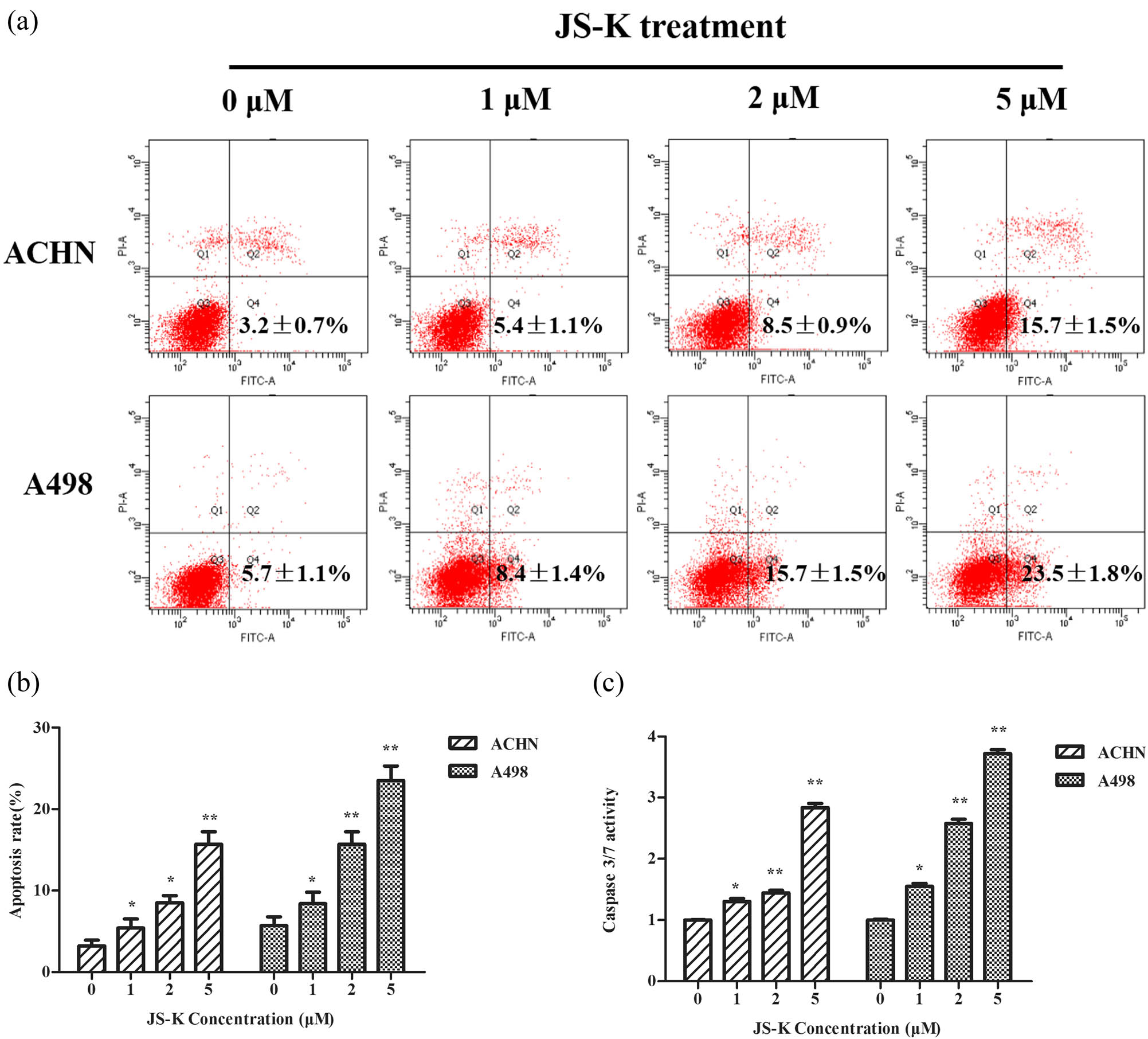

Renal carcinoma cells were treated with different JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) concentrations. Cells treated with JS-K for 24 h were distorted in shape and more cells endured apoptosis than untreated cells (Figure 2a). To analyze the possible inhibition of cell proliferation by JS-K in renal carcinoma cells, a CCK-8 assay was conducted. The data showed that JS-K exhibited highest dose- and time-dependent inhibition of renal carcinoma cell proliferation (Figure 2b and c). IC50 concentrations are 6.59 ± 0.16 μM (ACHN cells) and 5.52 ± 0.14 μM (A498 cells) at 24 h. Flow cytometry was used for the evaluation of the apoptosis effect of JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) in renal carcinoma cells. The findings showed that the apoptosis rate of renal cancer cells expanded in a dose-dependent manner after treatment with JS-K for 24 h (Figure 3a and b).

JS-K treatment inhibits renal carcinoma cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. (a) Visualized apoptosis caused by microscopy of JS-K in ACHN and A498 cells at 24 h (100×). (b and c) Cells were exposed to various JS-K concentrations (1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μM) for 12, 24, and 48 h, with an inhibition rate of 0%. Thus, every sample was recreated, and three separate assays (n = 3) are shown in the figure. The findings are presented as mean ± SD.

JS-K induces apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells. (a and b) JS-K-induced renal carcinoma cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry by using the staining method of Annexin V. Cells untreated were studied as controls. (c) Renal carcinoma cells were treated for 360 min with JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) and then intracellular activity of caspase-3/7 was detected. For at least three separate assays, findings are reported as mean ± SD. Single asterisks (*) show a substantial difference (P < 0.05), and double asterisks (**) show a very important difference (P < 0.01).

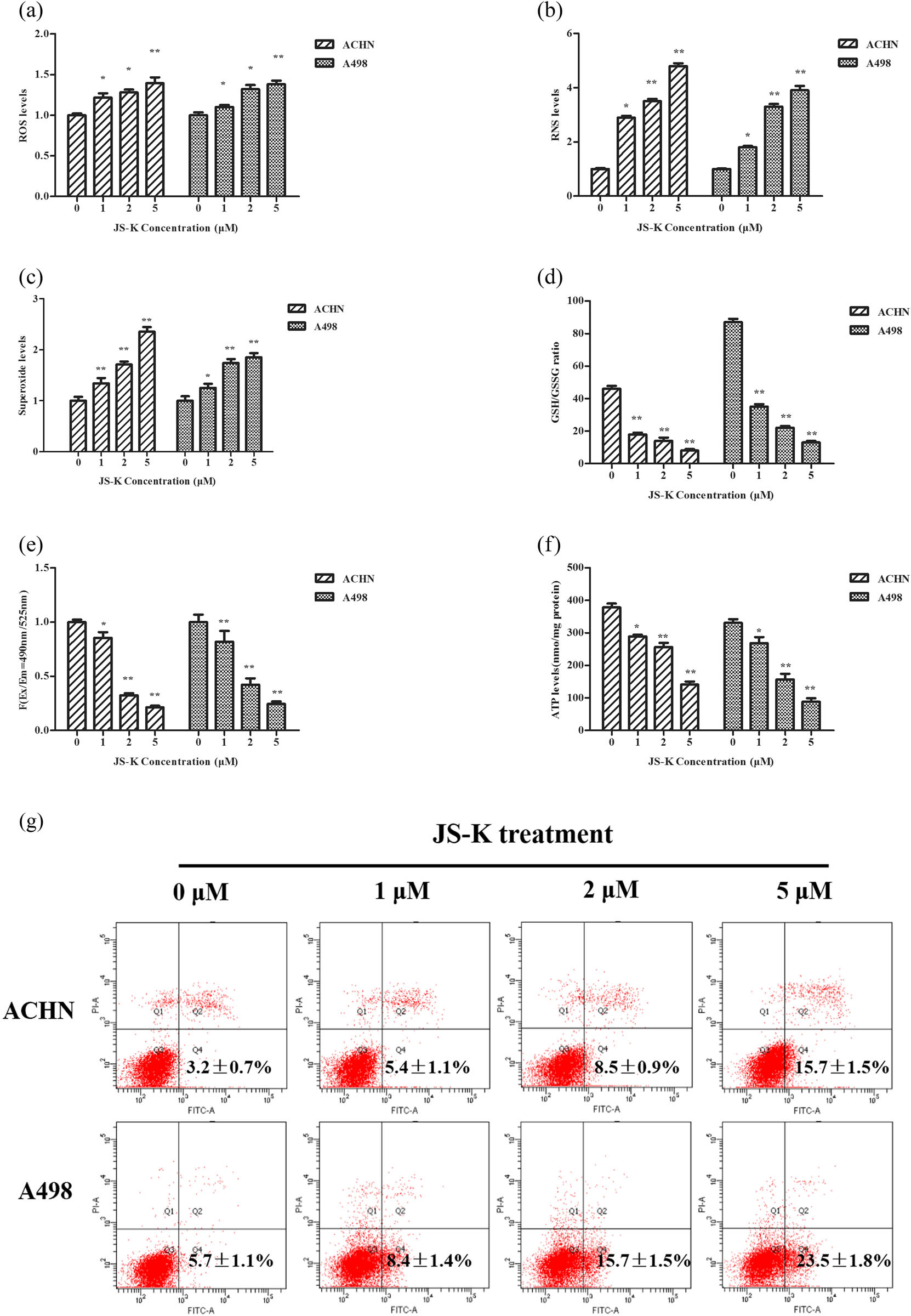

3.2 JS-K increases ROS and RNS levels and decreases the GSH/GSSG ratio in renal carcinoma cells

Overall ROS development, RNS, and superoxide concentrations were inspected after 6 h of treatment with varying ratios of JS-K in renal carcinoma cells. When renal carcinoma cells are treated with S-K, a substantial increase in the total output of ROS (Figure 4a), RNS (Figure 4b), and superoxide (Figure 4c) was observed. To control the impact of JS-K on oxidative stress, we also checked intracellular levels of GSH and GSSG. Its ratio decreased dramatically with JS-K therapy (Figure 4d). Thus, these data show that JS-K can induce an intracellular redox state imbalance, which may stimulate mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis mediated by mitochondria.

Effect of JS-K on ROS, RNS, mitochondrial membrane potential, GSH/GSSG ratio, ATP production, and apoptotic-related proteins in renal carcinoma cells. Treatment of JS-K renal carcinoma cells (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) for 360 min, and then detection of intracellular maximum ROS (a), RNS (b), superoxide (c), and GSH/GSSG ratio (d) levels. Upon 360 min of JS-K treatment, measurements were made for mitochondrial membrane potential (e) and ATP output (f and g). Western blot was used to identify concentrations of apoptotic-related proteins such as Bak, Bax. and PARP after cells were treated with JS-K (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) for 24 h. For at least three separate assays, findings are reported as mean ± SD.

3.3 JS-K reduces mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP levels in renal carcinoma cells

To evaluate the energy generation of mitochondria, the intracellular generation of mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP in renal carcinoma samples transfected with JS-K was evaluated. Upon treatment of cells with varying concentrations of JS-K for 6 h, the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 4e) and intracellular ATP (Figure 4f) were reduced in a dose-dependent way.

3.4 Effect of JS-K on the production of apoptotic proteins in renal carcinoma cells

Upon treatment with different concentrations of JS-K for 24 h, apoptotic proteins involved in mitochondria-mediated renal carcinoma cell apoptosis were measured. JS-K treatment showed an increase in the exercise of both caspase-9 and cleaved PARP compared to the Western blot negative controls (Figure 4g). Activation of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bak and Bax was upregulated by the J-SK treatment, while dose-dependent downregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was seen (Figure 4g).

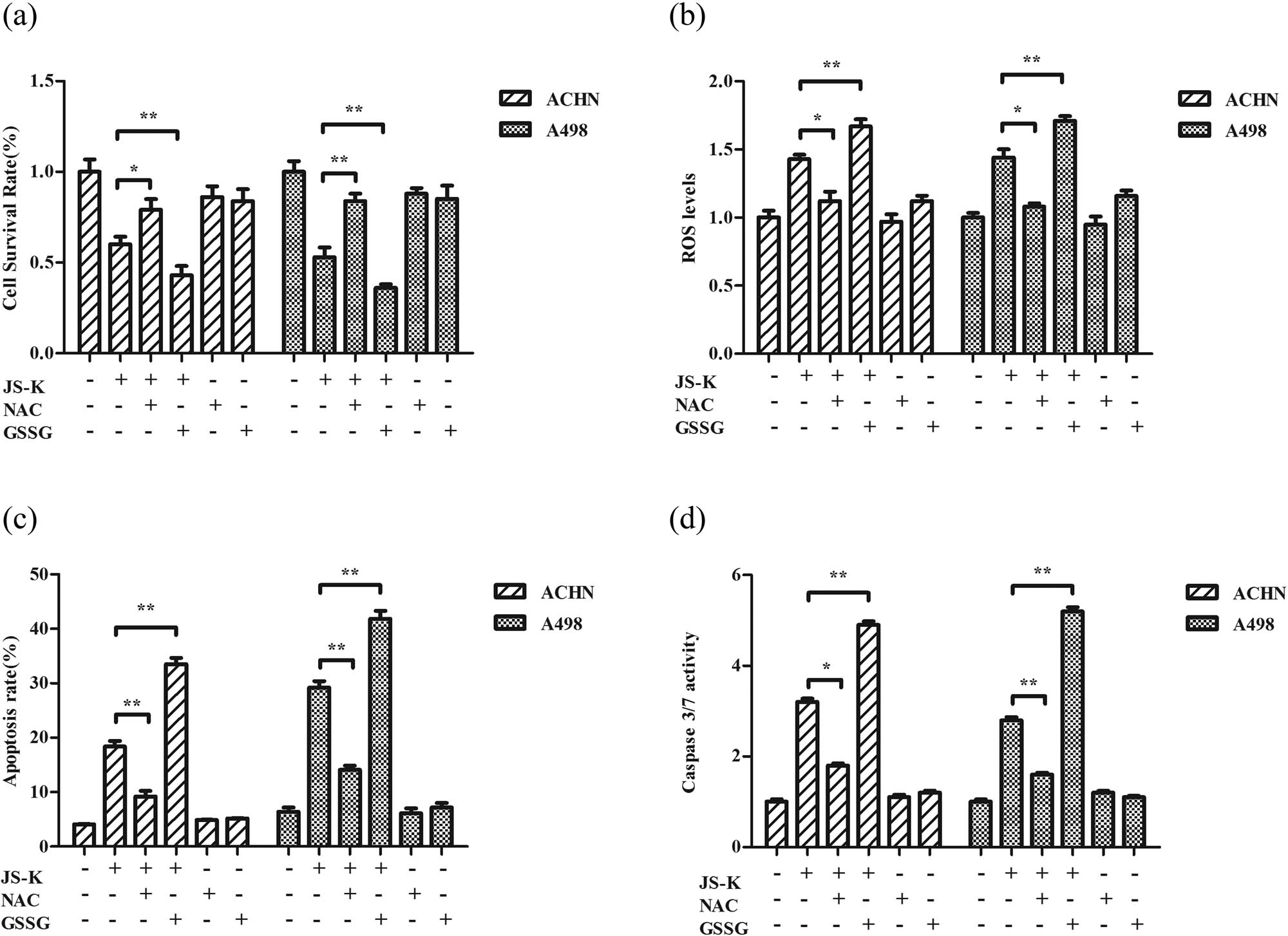

3.5 Impacts of NAC and GSSG on JS-K-induced cell growth suppression and apoptosis

In the inclusion or exclusion of antioxidants NAC (100 μM) or pro-oxidant GSSG (5 μM), renal carcinoma cells were treated with 5 μM JS-K for 24 h, separately, to evaluate the function of ROS in JS-K-induced cell proliferation inhibition and also apoptosis. The review shows that NAC restored the JS-K-induced inhibitory activity as well as renal cancer cell apoptosis and effectively reinstated ROS levels (Figure 5). Conversely, GSSG enhanced the inhibitory effect and apoptosis inserted by JS-K and thereby promoted the JS-K-mediated ROS production (Figure 5).

Effects of NAC and GSSG on JS-K-induced cell growth suppression and apoptosis. Cells were pre-cultured for 24 h with 100 μM NAC or 5 μM GSSG, and then incubated for 24 h both with and without 5 μM JS-K. Cell survival was assessed by CCK-8 assay (a), and flow cytometry (c) was evaluated for cell apoptosis. Cells were pretreated with 100 μM NAC or 5 μM GSSG for 24 h and subsequently treated with or without 5 μM JS-K for 6 h, and ROS output was measured (b) and Caspase-3/7 activation was analyzed (d). The values are represented as mean ± SD for at least three independent experiments. A single asterisk (*) shows a substantial difference (P < 0.05), and a double asterisk (**) (P < 0.01) shows an exceedingly big variation.

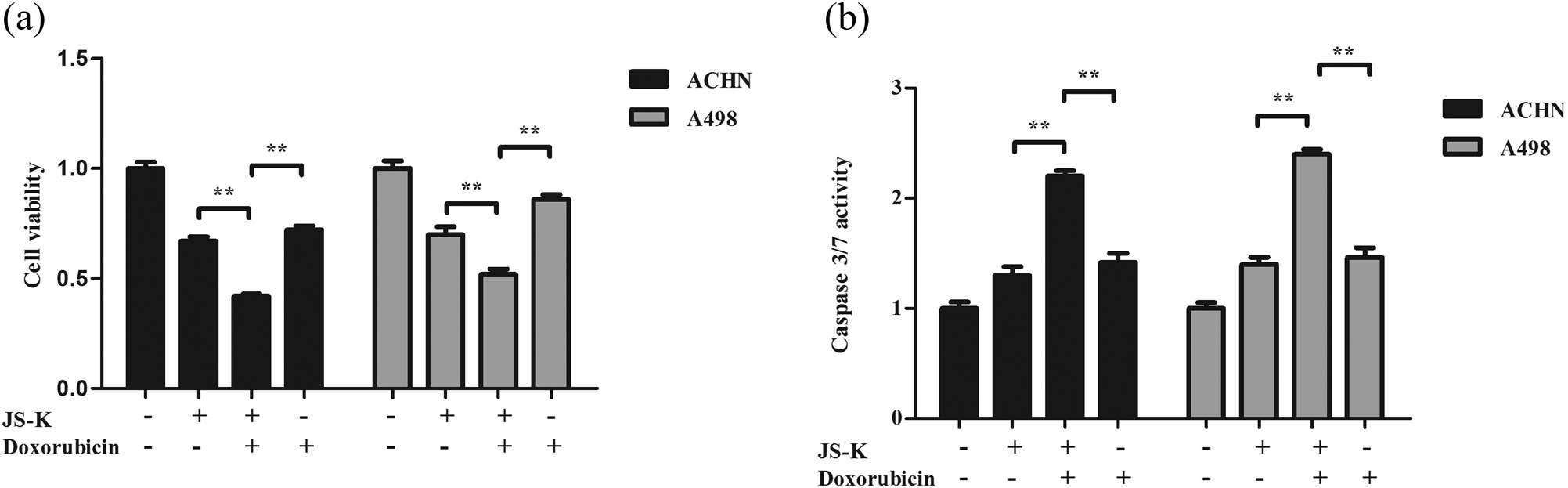

3.6 JS-K augments the chemosensitivity of doxorubicin in renal carcinoma cells

Renal carcinoma cells have been co-treated with JS-K and doxorubicin to assess the impacts of JS-K on the chemical sensitivity of doxorubicin. Compared to the treatment with JS-K alone or doxorubicin alone, combination action with JS-K and doxorubicin resulted in much more potent cell viability inhibition (Figure 6a). There was also a synergistic impact of the combined therapy with JS-K and doxorubicin on the promotion of caspase-3/7 in renal carcinoma cells (Figure 6b).

JS-K enhances the chemosensitivity of doxorubicin in renal carcinoma cells. (a) Cell viability was assessed following 12 h treatment with JS-K (5 μM) and doxorubicin (0.2 μM) using a CCK-8 assay. (b) Expression of caspase-3/7 in cells of renal carcinoma following treatment at multiple drug levels and time courses. The result for at least three separate experiments is expressed as mean ± SD. A single asterisk (*) shows a substantial difference (P < 0.05), and a double asterisk (**) (P < 0.01) shows an exceedingly huge difference.

4 Discussion

The previous studies have shown a steady increase of this cancer globally. Moreover, renal cell carcinoma is resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Therefore, it is essential to obtain an insight into the mechanisms of molecules of tumor cell apoptosis in primary renal cell carcinoma lesions to improve treatment and prognosis for this disease [15,16].

Whenever an imbalance exists between both the generation rate of ROS and the rate of ROS removal by scavenging mechanisms, oxidative stress occurs in some way. Glutathione is a ubiquitous cellular thiol that has two types: the main thiol redox mechanism in cells is depleted (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) and correct GSH/GSSG redox equilibrium is essential for the cell activity [17]. Thus, we hypothesized that JS-K-released nitric oxide would promote apoptosis of renal carcinoma cells by triggering ROS. Thus, this research shows that by the ROS production, JS-K conferred a cytotoxic effect and triggered renal carcinoma cell apoptosis. The development of renal carcinoma cells reduced with increasing JS-K concentrations, and apoptosis improved in a dose-dependent method. Findings show that NAC reversed the cytotoxic effect of JS-K and was improved by GSSG. ROS is significant for normal cellular processes. The deregulating level of ROS leads to the growth of numerous human diseases, including cancer. In contrast with normal tissue, due to rapid cell metabolism, cancer cells have elevated ROS levels. In cancer cells, the high ROS levels differentiate them from normal cells and can promote tumorigenesis. However, high ROS levels are also an Achilles’ heel for cancer cells because the elevated ROS renders cancer cells highly prone to oxidative stress-induced cell death that can be used by targeted cancer therapy to control [18,19]. For cell proliferation and apoptosis, ROS is a vital signaling molecule [20]. The stimulation of intracellular signal transduction, including the numerous cellular processes, such as inflammation, progression of the cell cycle, and invasion, is also involved in ROS [21].

It has been confirmed that various physiological phenomena and apoptosis-inducing chemicals result in oxidative stress by ROS generation, indicating a strong linkage between apoptosis and oxidative stress [22,23]. The intracellular redox state is sustained inside a narrow range under standard circumstances, but under pathological conditions, this balance may be disrupted to decrease or increase values [24]. JS-K-released NO has been reported to result in extremely high intracellular concentrations of ROS [6]. To inhibit the epithelial–mesenchymal transition as well as cancer development in prostate cancer cells [25], excessive ROS generation has been reported. In renal carcinoma cells, larger ROS, RNS, superoxide alterations, cell inhibition rates, and apoptosis rates have originally been identified, suggested that these cells might be highly sensitive to JS-K [9]. Indeed, we found significantly increased levels of ROS/RNS along with the increased apoptosis and inhibition of cell proliferation in two renal carcinoma cell lines following the treatment with JS-K. In addition, the antioxidant NAC reversed the antitumor effects of JS-K, whereas the pro-oxidant GSSG enhanced these effects, suggesting that ROS induction may be a way by which JS-K exerts its effects in renal carcinoma cells. Moreover, the outcome indicated that co-treatment with JS-K improved the renal carcinoma cell’s chemosensitivity to doxorubicin.

GSH is an important antioxidant. The consumption of glutathione can result in redox imbalance, which is related to mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis [26]. We demonstrated that the GSH level was significantly reduced by JS-K but increased the GSSG production in renal carcinoma cells, which lead to a reduction in the GSH/GSSG ratio. Moreover, findings have shown that the manufacturing of ATP could be controlled during apoptosis by the reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential [8]. Our data showed that, in a dose-dependent way, JS-K reduced the mitochondrial membrane latent and also ATP concentrations. In addition, upregulation of cleaved-caspase-9 has been observed, and it has a significant role in the family of cysteine aspartic protease (C)[27,28]. PARP is a caspase-9 precursor that helps in DNA repair, and cleaved-PARP is considered an indicator of cell proliferation apoptosis [29,30]. Bcl-2, Bax, and Bak are essential components of apoptosis activation of mitochondrial stress, and the Bcl-2 and Bax balance is essential for cell existence [31,32]. In this study, we showed that therapy with JS-K enhanced the expression in renal carcinoma cells of pro-apoptotic proteins, for instance, cleaved-Caspase-9, cleaved-PARP, Bax, and Bak, but JS-K reduced the expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. For instance, JS-K therapy has also improved caspase-3 and caspase-7 activities since they are either partly or entirely accountable for PARP cleavage. It has also showed that treatment using JS-K increased caspase-3/7 activation in renal carcinoma cells, indicating that aggregation of ROS induced by JS-K can encourage mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in cells of renal carcinoma.

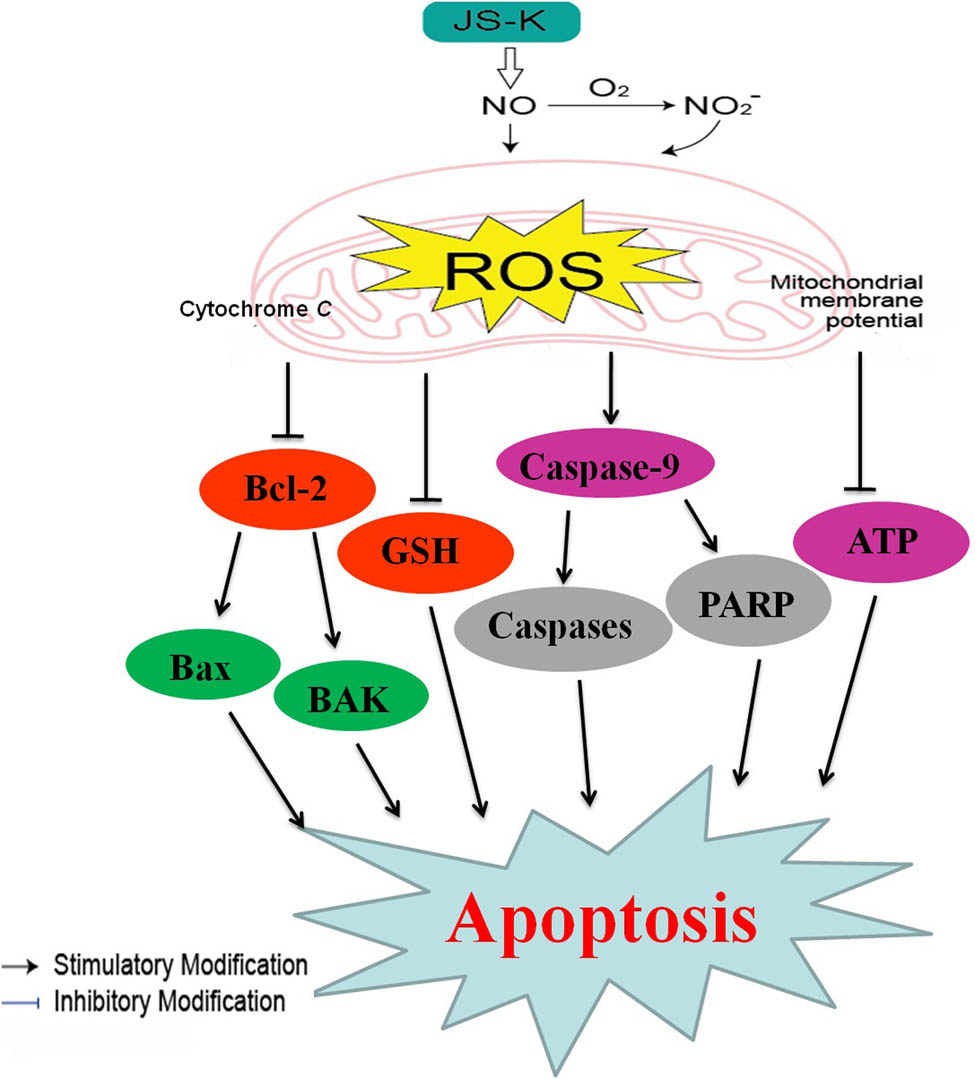

5 Conclusion

In particular, a major element for the progression of the disease is redox imbalance due to excessive or inadequate ROS. We have shown that ROS is strongly correlated with the proliferation of renal carcinoma cells as well as that the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway is stimulated by excessive ROS accumulation. In this study, the impacts of JS-K on human renal carcinoma cells have been evaluated and JS-K is indicated to considerably get rid of cell proliferation and to induce apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells as a result of the high ROS buildup. We indicated that the development of ROS is necessary for the initiation of the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway by JS-K (Figure 7). We theorize that there had been a disparity in redox reactions to support well-being in renal carcinoma cells. The effect of nitrites from NIL sources on renal carcinoma cells had also been studied, and findings equivalent to those induced with JS-K therapy were seen. Although more research will be required to comprehend the dynamic underlying mechanisms in the JS-K–induced production of ROS, collected data indicate that JS-K induces renal carcinoma cell apoptosis, and this is regulated, at least to some extent, via the renal carcinoma cell ROS-related pathway.

Cellular pathway of JS-K-induced cell apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells. JS-K-induced apoptosis of renal carcinoma cells via cytochrome c activation, repression of mitochondrial membrane potential by caspase-9 and PARP, and ATP. ROS development will continue, which ultimately led to apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

Our regards are to our fellow laboratory members for their directly participation in the study. The Medical Research Fund are the funders (No. A2018235) of Guangdong.

-

Funding information: The Medical Research Fund are the funders (No. A2018235) of Guangdong.

-

Author contributions: J. D. X. and L. Q. C.: designed the experiments. J. Y. C., L. Q. C., D. Q. H., and W. W. Y.: performed the experiments. J. D. X. and C. X. L.: were involved in data and statistical analyses. C. L. Q. and J. Y. C.: wrote the article and prepared figures. C. X. L. and J. Y. C.: provided guidance and the financial support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing of interests.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Men S, Zhu Y, Li JF, Wang X, Liang Z. Apigenin inhibits renal cell carcinoma cell proliferation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:19834–42.10.18632/oncotarget.15771Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Lee CH, Hung PF, Lu SC, Chung HL, Chiang SL, Wu CT, et al. MCP-1/MCPIP-1 signaling modulates the effects of IL-1β in renal cell carcinoma through ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23):6101–19.10.3390/ijms20236101Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] He H, Zhuo R, Dai J, Wang X, Huang X, Wang H, et al. Chelerythrine induces apoptosis via ROS ediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and STAT3 pathways in human renal cell carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;24(3):1–11.10.1111/jcmm.14295Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Chien G. Trend of surgical treatment of localized renal cell carcinoma. Perm J. 2019;23:18–108.10.7812/TPP/18-108Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Shami PJ, Saavedra JE, Wang LY. JS-K, a glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide donor of the diazeniumdiolate class with potent antineoplastic activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:409–17.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Kiziltepe T, Hideshima T, Ishitsuka K. JS-K, a GST-activated nitric oxide generator, induces DNA double-strand breaks, activates DNA damage response pathways, and induces apoptosis in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2007;110:709–18.10.1182/blood-2006-10-052845Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Hsieh HJ, Liu CA, Huang B. Shear-induced endothelial mechanotransduction: the interplay between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) and the pathophysiological implications. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:1–15.10.1186/1423-0127-21-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Maciag AE, Chakrapani H, Saavedra JE. The nitric oxide prodrug JS-K is effective against non-small-cell lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo: involvement of reactive oxygen species. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:313–20.10.1124/jpet.110.174904Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Laschak M, Spindler KD, Schrader AJ. JS-K, a glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide releasing prodrug inhibits androgen receptor and WNT-signaling in prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:130–40.10.1186/1471-2407-12-130Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Mingning Q, Sai Z. JS-K enhances chemosensitivity of prostate cancer cells to taxol via reactive oxygen species activation. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:757–64.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Qiu M, Chen L, Tan G. A reactive oxygen species activation mechanism contributes to JS-K-induced apoptosis in human bladder cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15104–16.10.1038/srep15104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Liu B, Huang X, Li Y, Liao W, Li M, Liu Y, et al. JS-K, a nitric oxide donor, induces autophagy as a complementary mechanism inhibiting ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):645–59.10.1186/s12885-019-5619-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Xudong Z, Aizhen C, Zheng P. JS-K induces reactive oxygen species-dependent anti-cancer effects by targeting mitochondria respiratory chain complexes in gastric cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(4):2489–504.10.1111/jcmm.14122Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Zeqing S, Yong X. JS-K induces G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in A549 and H460 cells via the p53/p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1. Pathw Oncol Rep. 2019;41(6):3475–87.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Yang CM, Ji S, Li Y. β-Catenin promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion but induces apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:711–24.10.2147/OTT.S117933Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17009–18.10.1038/nrdp.2017.9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Maciag AE, Holland RJ, Cheng YS. Nitric oxide-releasing prodrug triggers cancer cell death through deregulation of cellular redox balance. Redox Biol. 2013;1:115–24.10.1016/j.redox.2012.12.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Galadari S, Rahman A, Pallichankandy S. Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: to promote or to suppress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;104:144–64.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.01.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Prasad S, Gupta SC, Tyagi AK. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cancer: role of antioxidative nutraceuticals. Cancer Lett. 2017;387:95–105.10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.042Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Ray PD, Huang BW, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–90.10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Wu WS. The signaling mechanism of ROS in tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:695–705.10.1007/s10555-006-9037-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Pathak N, Khandelwal S. Oxidative stress and apoptotic changes in murine splenocytes exposed to cadmium. Toxicology. 2006;220:26–36.10.1016/j.tox.2005.11.027Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Lin B, Tan X, Jian L. A reduction in reactive oxygen species contributes to dihydromyricetin-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7041–9.10.1038/srep07041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Buonocore G, Perrone S, Tataranno ML. Oxygen toxicity: chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:186–90.10.1016/j.siny.2010.04.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Das TP, Suman S, Damodaran C. Induction of reactive oxygen species generation inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes growth arrest in prostate cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:537–47.10.1002/mc.22014Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Nie F, Zhang X, Qi Q. Reactive oxygen species accumulation contributes to gambogic acid-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells. Toxicology. 2009;260(1–3):60–7.10.1016/j.tox.2009.03.010Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Allan LA, Clarke PR. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation. FEBS J. 2009;276(21):6063–73.10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07330.xSuche in Google Scholar

[28] Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Caspases: killer proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:299–306.10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01085-2Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Satoh MS, Lindahl T. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature. 1992;356:356–8.10.1038/356356a0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Oliver FJ, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase in the cellular response to DNA damage, apoptosis, and disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1282–8.10.1086/302389Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Pohland T, Wagner S, Mahyar-Roemer M, Roemer K. Bax and Bak are the critical complementary effectors of colorectal cancer cell apoptosis by chemopreventive resveratrol. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:471–8.10.1097/01.cad.0000203387.29916.8eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Tasyriq M, Najmuldeen IA, In LL, Mohamad K, Awang K, Hasima N. 7alpha-hydroxy-beta-sitosterol from chisocheton tomentosus induces apoptosis via dysregulation of cellular Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cell cycle arrest by downregulating ERK1/2 activation. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:765316–28.10.1155/2012/765316Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2021 Jindong Xie et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation