Abstract

Environmental pollution by mercury is a local problem in Poland and concerns mainly industrial sites. Foundry waste are usually characterized by low mercury content compared to other heavy metals. Spent foundry sands with low content of Hg are the main component of foundry waste. However, Hg may be present in foundry dust, which may also be landfilled. Due to Hg toxicity, even a minimal content may have a negative impact on biota. This study focuses on assessing the mercury content of landfilled foundry waste (LFW), to assess its toxicity. Currently tested waste is recovered and reused as a road aggregate. The results were compared with the mercury content of local soils as the reference level. Waste samples were taken from foundry landfill. The mercury content, fractional composition, organic matter (OM) and total organic carbon content, pH and elementary composition of waste were analysed. It was found that the mercury content in LFW was very low, at the level of natural content in soils and did not pose a threat to the environment. The statistical analysis shows that mercury was not associated with OM of the waste, in contrast to soils, probably due to different types of OM in both materials.

1 Introduction

In the foundry industry, depending on the technological process used, various types of waste are produced. These include mainly spent foundry sands (SFSs), furnace slags, sludges or dusts from dust collectors and small quantities of metallic chips, excess material and others [1]. It is estimated that the mass of waste generated during the production process is similar to the mass of castings produced [2]. Therefore, the most important environmental protection measure taken by the foundry industry is the reduction in the amount of waste generated and its recovery. According to the Polish classification of waste, waste from the iron and steel industry is classified primarily in group 10 “Waste from thermal processes,” subgroup 10 09 “Waste from iron casting.” More than 75 codes have been assigned to foundry waste [2,3]. SFS represents up to 90% of the mass of all foundry waste produced. The sources of SFS are the processes of moulding, knock-out and the purification of castings. Due to high landfill costs, many foundries now use SFS regeneration facilities. The SFS that cannot be regenerated and reused in the foundry may be used in other industrial sectors, e.g. in road building and construction for the production of concrete mortar, Portland cement, road profile filling, road embankments and industrial platforms, as additives to asphalt, brick production, trench filling and ceramics [4]. In many countries such as United States, SFS is used to produce artificial soil substrates for agricultural and horticultural use [5,6]. The use of SFS for the production of artificial soil and technosol must not pose a risk to the environment and human health [7,8,9]. Therefore, the use of SFS from non-ferrous metal foundries is not recommended due to their contamination with heavy metals [10,11,12,13]. In addition to SFS, other foundry waste, such as metal, slag and dust, is also used. Even foundry waste that has been landfilled for many years may be reused [14]. The cost-effectiveness of the use of this waste depends on a number of factors, such as the type of waste, composition, the content of pollutants, physical properties and availability [15]. The main threat posed by foundry waste is the possibility of leaching and the migration of heavy metals in the environment [10,11,14,16,17,18]. The degree of contamination of SFS with heavy metals is mainly related to not only the type of cast metal but also the composition of the foundry sands, binders and hardening agents. Among the heavy metals, Hg, Cd and Pb are considered to be the most toxic [19]. However, the content of these metals in foundry waste is usually low [5,20].

Mercury is one of the most toxic heavy metals. Hg pollution is a global problem [21]. Therefore, in 2017, more than 120 countries signed the Minamata Convention, which aims to reduce global mercury emissions to the environment. The main anthropogenic sources of environmental pollution by mercury are industry, including the chemical industry, waste and fuel combustion and agriculture [22]. Increased Hg content in soils is found around metallurgical plants and smelters, coal-fired power plants, cement plants and their industrial waste landfills [22]. Industrial waste is also an important source of mercury in the environment [23,24]. Environmental pollution by mercury is a local problem in Poland and concerns industrial sites, mainly those close to mines [25], coal power station [26,27], in the vicinity of transport routes [28,29], in areas with active mining industry [30] and the Pb–Zn metallurgy [24]. In soil, mercury and many other metals are usually bounded with loamy material, sulphates and soil organic matter (SOM) [19,21,29]. Databases and maps of pollutant (heavy metals) distribution in the soils of all continents, including Europe, have been created in recent years [31]. According to these data, the mercury content in European soils varies within limits: agricultural soils <0.003–1.6 mg kg−1 DM and grazing land soil <0.003–3.1 mg kg−1 DM, respectively [31]. In Europe, the mercury pollution of soils occurs locally and is related to human activities, mainly in urban agglomerations, near coal-fired power stations, waste incinerators, chemical plants or metal works. According to GEMAS data, Poland belongs to the group of countries with a low Hg content in soils [31]. Only the border region with the Czech Republic and Germany (Western Sudetes) is polluted by this metal to a greater degree. The cause of this anomaly has not been explained; however, the impact of emissions from the combustion of hard coal was excluded [31]. In Poland, the degree of pollution with mercury and other metals in soils is regulated by Ordinance by conducting the assessment of pollution of the earth’s surface [32]. From the soil, mercury can penetrate into groundwater or accumulate in plants. The use of SFS as a substitute for soil brings about the risk of the contamination of soil substrates and thus the heavy metal contamination of crops [5,6]. However, the content of mercury in foundry waste is generally low, often below the limit of quantification (LOQ); therefore, its determination in SFS is omitted [5,17,20].

Although heavy metal contamination of SFS has been investigated thoroughly, Hg has received relatively little attention. Foundry wastes are usually characterized by low mercury content; for this reason, in the toxicity assessment of this waste the content of this metal is not analysed. However, due to Hg toxicity, even a minimal content may have a negative impact on biota. In previous studies, the content of heavy metals and their leaching from foundry waste were assessed [14,18,33], the purpose of which was to classify and assess the environmental impact of this waste. This study focuses on assessing the mercury content of foundry waste. The results were compared with the mercury content of local soils to assess the degree of waste pollution compared to the reference level. The detailed aims of this study were as follows: (1) the assessment of the degree of mercury contamination of landfilled foundry waste (LFW) from one of the Polish foundries; (2) fractional (particle-size) analysis of waste and the determination of a possible relationship between Hg content, particle size and organic matter (OM); and (3) a comparison of the results with the natural content in soil.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Foundry characteristics and waste sampling

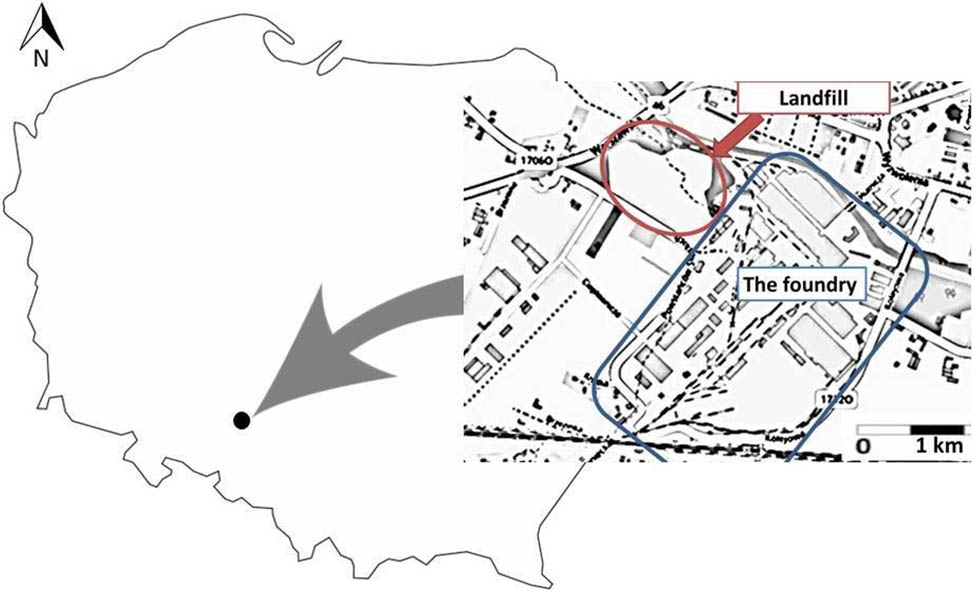

The foundry is located in south–western Poland, in the Opolskie Voivodeship (N 50°40′20.5853″; E 18°12′44.7181″). The foundry produces steel and iron castings, raw and machined, which are parts for industrial machinery and equipment. The landfill is located next to the foundry (N 50°40′40.0885″; E 18°12′17.1021″). The landfilled waste includes SFS, slag, spent refractories, sludge from dust collectors and sewage treatment plants and metalliferous inclusions. Foundry waste was landfilled from the 1990s to the present day. Previously, foundry waste was landfilled in another landfill, which is located at a considerable distance from the foundry and is no longer owned by the foundry. Currently, the waste material from both landfills is being recovered; this process began in the 2000s, and it is being used for aggregate production. It is estimated that over 3.5 million tonnes of waste was deposited in both landfills (data from 2003).

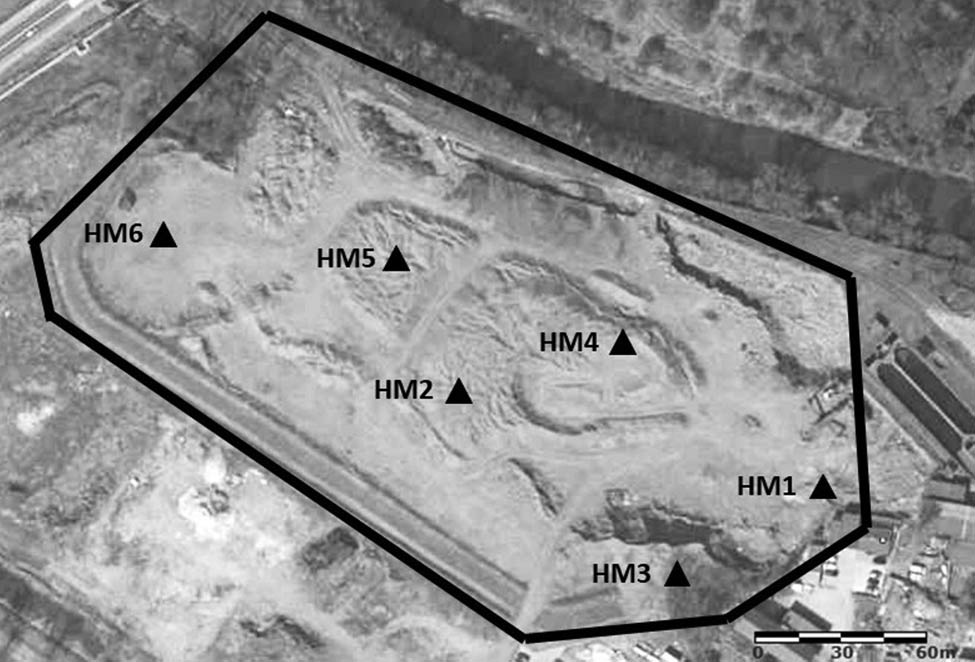

Due to the recovery and reuse of landfilled waste, in 2015 the landfill area owned by the foundry was reduced from 8.9 to 4.66 ha and modernized. The location of the foundry and landfill is shown in Figure 1. The tested samples were taken from this landfill in 2017. By this time most of the waste had been recovered. Six piles of recovered waste material were created at the landfill, with a height of 3 m and a capacity of approximately 100 m3 each. Test samples were taken from these piles (Figure 2). A total of 10–15 incremental samples were taken from each pile according to Polish standards (PN-EN 932-1:1999; PN-EN 932-2:2001). The samples were mixed and the volume was reduced by quartering to 5 L (laboratory sample). In the laboratory, the tested samples were dried at room temperature. Then, fraction analysis was performed using sieves with a decreasing mesh size (0.2–5.6 mm). Fractional analysis was performed in triplicate for each batch. A sample of 1 kg was used for this purpose. Each fraction was weighed with an accuracy of 0.1 g. The triplicate results were averaged. The other portion of the waste material was ground into a ball mill without pre-sieving.

Location of the foundry and landfill (Ozimek, Poland). Source: www.google.pl/maps

Location of the landfill and waste sampling sites. Source: www.google.pl/maps

2.2 Soil sampling

In order to assess the reference level, soil samples were taken from 20 measuring points located at different distances from the landfill. The sampling locations were the same as they were in previous studies [33] (Figure 3). The soils originated from arable land (No. 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19 and 20), meadows (No. 1), wasteland (No. 6, 9 and 14), allotment gardens (No. 5, 11, 12, 13 and 15) and forest soil (No. 10 and 18). Soil samples were taken and prepared according to Polish standards (PN-ISO 10381-2:2007; PN-ISO 10381-5:2009). Similar to waste samples, the soil was collected in November 2017. The samples were dried at room temperature, in air-dry conditions, triturated in a mortar and sieved (<1, <0.2 mm). No fractional analysis was performed for soil samples as it was not the aim of the study. The granulometric composition and classification of soils were performed in previous studies [33]. The mercury content in local soils as a natural background was compared with the landfilled waste.

Location of soil sampling points. Source: www.google.pl/maps

3 Methods

The pH was measured in an aqueous extract and in 1 M KCl (1/5, v/v) using a glass electrode with pH-conductometer CPC 501 (Elmetron) according to Polish standard (PN-ISO 10390). The content of total organic carbon (TOC) (<0.2 mm) according to the modified Tyurin titrimetric (classical) method [34] was analysed. The CHNS (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur) in the milled <0.1 mm averaged waste lot were determined using Elementar Vario Macro Cube elemental analyzer. In every fraction of waste and soil samples (<1 mm), the content of OM and SOM at 550°C and Hg was analysed. Mercury content was determined using the cold vapour atomic absorption spectrometry method for solid samples using an analyzer AMA 254 (Altec Ltd). All samples were carried out and analysed in triplicate.

3.1 Correlation analysis and quality control

The arithmetic mean and standard deviation from triplicate data were calculated using Software Statistica version 13.3, considering a significance level of p < 0.05. The simple correlation coefficients (r) (p < 0.05) between the LFW fractions, OM, TOC, total carbon (TC) and Hg of foundry waste and between SOM and Hg content in soil were calculated using Pearson’s test. For quality control certified reference materials (CRMs) were also analysed: for Hg content “Metals in soil” (SQC001, Merck) and “Rock” (DC73303, NCS) and for CHNS content “Alfaalfa B2273” (Cert. No. 41505). The accuracy of the methods was assessed by testing the degree of CRM recovery. Acceptable recovery range for CRM was 90–110%. The LOQs for each method were as follows: pH < 0.1; OM, TC, and TOC <0.1 wt%; H, N, and S <0.01 wt%; Hg <0.0005 mg kg−1.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Foundry waste

The basic characteristics of the analysed waste are presented in Table 1. The waste was characterized by a neutral and moderately alkaline pH with a mean pHH2O of 7.9 (range 7.3–8.5). Similarly, Dayton et al. found a neutral pH of leachate from foundry waste [6]. It is known that the pH value affects the leaching of contaminants from foundry waste; a low pH increases heavy metal mobility [5,20]. In the current study, mean OM and TOC contents in waste were 4 and 2.2 wt%, respectively. The main component of OM in foundry waste is organic binders which are present in spent casting moulds after the metal casting process. OM in SFS may contain toxic substances, for example, phenol, formaldehyde directly from phenol-formaldehyde binders or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons generated from organic binders after contact with liquid metal at a high temperature [6,11]. Among the analysed elements from elemental analysis (C, H, N, S), the highest percentage of carbon was found. The percentage of other elements (HNS) was low (0.04–0.09 wt%) (Table 1). In the case of sulphur, its forms that dissolve in water, i.e. sulphates, may be a problem. An excessively high concentration of sulphates in the eluates may disqualify the waste from being recovered [28,29]. However, the percentage of sulphur in the examined waste was small (mean 0.09%); therefore, it may be assumed that the waste will not pose a threat to the environment.

Characteristic of foundry waste

| Parameter | Min | Max | Mean (n = 18) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHH2O | 7.3 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 0.4 |

| pHKCl | 6.8 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 0.4 |

| OM (wt%) | 1.8 | 15.5 | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| TOC (wt%) | 1.0 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| TC (wt%) | 1.2 | 8.2 | 2.7 | 1.2 |

| H (wt%) | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| N (wt%) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| S (wt%) | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

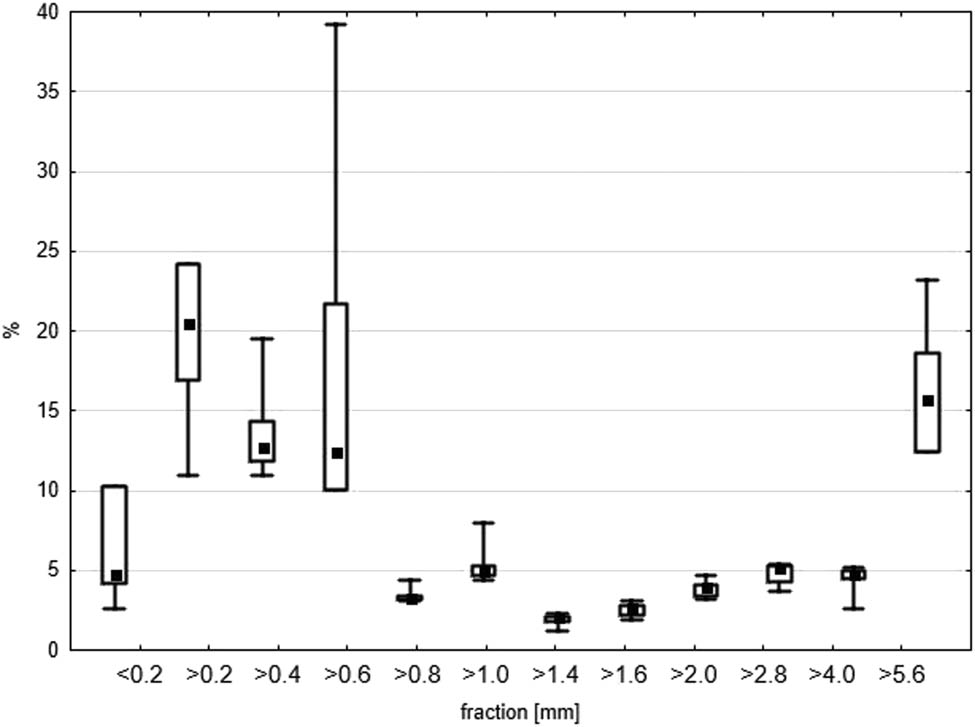

4.2 Fractional analysis, particle size of waste

The percentage of every fraction in the analysed waste is shown in Figure 4. A wide range of results was obtained for most of the fractions. This proves the heterogeneity of the landfilled material. Mass-wise, the highest percentages were found for the largest fraction above 5.6 mm and for fractions with a particle size between 0.2 and 0.6 mm. The largest fraction (>5.6 mm) consisted of metallic elements, sinter, slag and others. The percentage of other fractions did not exceed 5%. The percentage of the clay fraction (<0.2 mm) was low in the tested waste. This fraction is responsible for the binding properties of waste, which is important for applications in construction, but less so as an aggregate of foundry waste. The fractional analysis showed that the waste consisted mainly of sand fractions (<2 mm). Dayton et al. [6] obtained similar results. On the other hand, Siddique et al. [16] stated that the main fraction of foundry waste (85–95%) are particles of size between 0.15 and 0.6 mm, while the fine fraction (<0.075 mm) can reach up to 12%. The diversity of the composition and its specific structure makes it possible to use foundry waste in agriculture. The use of SFS in agriculture and horticulture is popular in countries such as Brazil, the United States and South Africa [5,6,16]. In 2007, the US EPA confirmed the benefits of using sands from iron and aluminium foundries in agricultural, horticultural and geotechnical applications [35]. Several US states have allowed the use of SFS for the production of artificial horticultural soils and Technosols [36,37].

Box and whisker plots of LFW fractions (%). The edges of the boxes show the SD, the whiskers show min–max, respectively. The mean is marked with a square point.

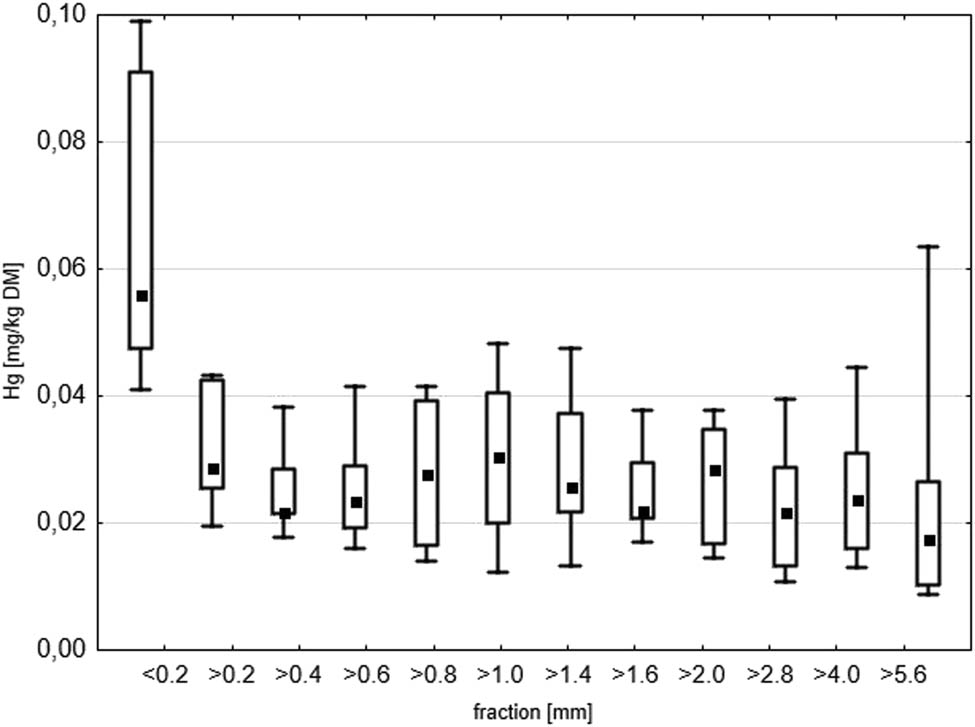

4.3 Mercury and OM content in the waste fraction

The mercury content in most fractions was similar and fell within the range of 0.023–0.031 mg kg−1 DM (Figure 5). The highest Hg content was found in the finest fraction (<0.2 mm), on average 0.065 mg kg−1 DM. The landfilled waste contained dust from dust collectors, which may have been the main component of the finest fraction. Foundry dusts, especially electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) is characterized by a high content of heavy metals including Hg compared to SFS [38,39,40,41]. Therefore, it may be assumed that the source of mercury in the finest fraction of the tested waste was foundry dusts with a high Hg content. Another explanation for this phenomenon may be the association of Hg with the loamy matter of this waste, just like in soils. Similarly, Klojzy-Karczmarczyk and Mazurek [26,28,30] and Kicińska [42] found the highest content of mercury and other heavy metals in the finer fraction of the mining waste, which was the effect of association with OM and the loamy material of this waste.

Box and whisker plots of Hg content (mg kg−1) in LFW fractions. The edges of the boxes show the SD, the whiskers show min–max, respectively. The mean is marked with a square point.

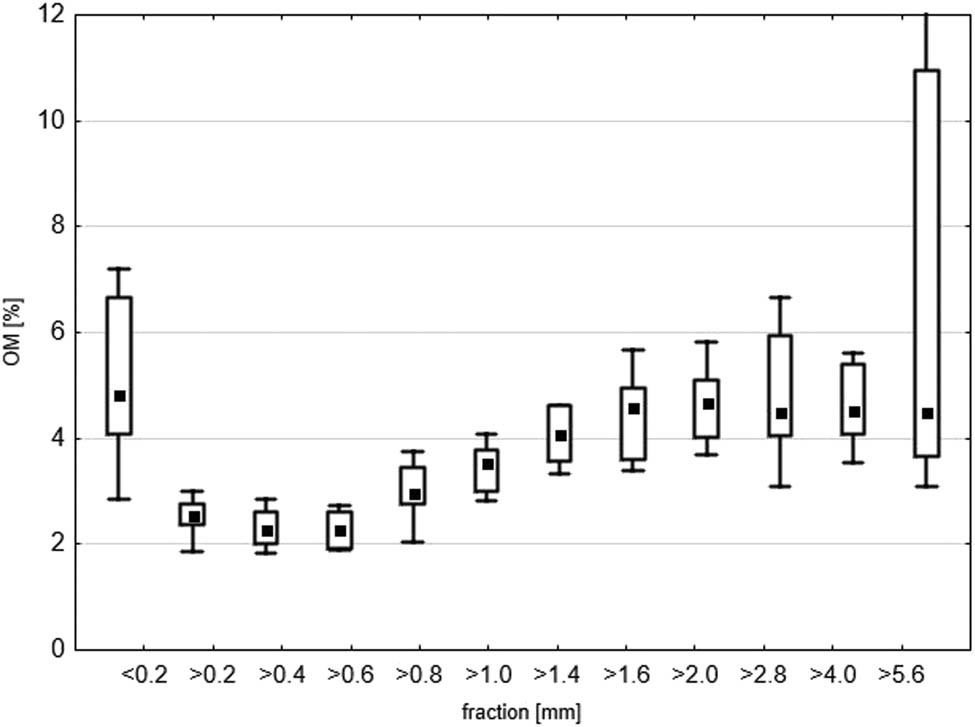

Figure 6 presents the percentage of OM in all fractions of the tested waste. The highest percentage of OM was found in the smallest fraction <0.2 mm (median 4.8%). In subsequent fractions, the percentage of OM decreased to 2.3% (fraction >0.6 mm), then increased to 4.5% for fractions >2.8 mm. The highest differences in the results were obtained for the largest fraction (>5.6 mm); OM varied between 3 and 15.5 wt%. This fraction was non-heterogeneous and consisted of various materials, hence the OM value differences. The composition of OM in foundry waste depends on the type of organic binders used in the production of foundry moulds. Binders may remain on sand particles after metal casting or may be ground off when separating the mould from the casting during shock grating or during mechanical regeneration of SFS [43].

Box and whisker plots of OM (%) in LFW fractions. The edges of the boxes show SD, the whiskers show min–max, respectively. The mean is marked with a square point.

4.4 Correlations analysis

A positive correlation means that both variables vary in the same way, when one increases the other increases. For a negative value of the correlation coefficient, the relationship between the variables is inverse. In the current study, no statistically significant correlation coefficients for the relationship between the Hg content and other parameters such as particle size – fractions, OM, TOC and TC were found. Therefore, it can be concluded that the mercury content did not depend on these parameters, unlike the soil. While a relationship between particle size and OM and carbon compounds (TC and TOC) in these waste was found. A low positive correlation between these parameters was obtained. The expected result was a high positive correlation for the relationship between OM, TOC and TC in the tested waste.

4.5 Local soil characteristic

This section presents the test results of soil around the foundry landfill. The aim was to compare the results of mercury content in waste with local soils being used as a natural reference. The physicochemical characteristics of the soil samples are presented in Table 2. An analysis of particle size shows that the soils of the studied area were light soils. The pH value in the analysed soils varied between pHKCl 5.8 and 7.5. The soils in the Opole region, as in Poland, are moderately acidic or acidic soils. The SOM content in the soils ranged from 1.77 to 5.25% and the TOC content from 0.59 to 2.14%. For comparison, the content of SOM is on average 1.94% (range 0.62–6.62%) and TOC 1.12% (range 0.36–3.84%) in Polish soils (https://www.gios.gov.pl/). The analysed soils were characterized by a moderate content of these components. In order to assess the degree of soil contamination of heavy metals, soil type, pH and TOC or SOM content is usually taken into account. Polish Regulation [32] considers Hg in soils depending on the soil group according to the purpose of their use. The permitted mercury content in Polish soils and the classification of the tested soils are also shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of soil samples

| Samples | Arable land and meadows | Allotment gardens | Forest soil | Wasteland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of land usea | II-1 | II-2 | III | IV |

| Hg (mg kg–1 DM) | 0.018–0.092 | 0.038–0.056 | 0.017–0.019 | 0.028–0.064 |

| Limit Hg contenta (mg kg–1 DM) | 2 | 4 | 10 | 30 |

| Granulometric composition | Sand/loamy sand | Sand | ||

| pHKCl | 6.0–6.7 | 6.6–6.9 | 6.8–7.5 | 5.8–6.7 |

| TOC (wt%) | 0.72–2.14 | 1.25–1.71 | 0.59–0.71 | 0.71–1.82 |

| SOM (wt%) | 2.08–5.25 | 2.96–3.62 | 1.77–2.03 | 1.83–5.11 |

- a

According to Polish classification (Journal of Law 2016 item. 1395), Group: II – arable land, orchards, meadows, pastures, allotment gardens, protected areas; III – forests, wooded areas; IV – industrial areas and traffic areas; II-1 and II-2 – subgroups according to pH and SOM values.

Current research shows that the mercury content in the soils of the studied area was very low and similar to its content in the tested waste. The mercury content in the soils studied was significantly lower than the limit values [32]. The Hg content in most soil samples was below 0.05 mg kg−1 DM, which is the average level for Polish soils [19,24]. Only a few samples were characterized at a slightly higher Hg content. In some regions of Poland, the Hg content in soils is increased due to industrial activities [22,24], along transport routes [28], in areas adjacent to a coal-fired power plant [26]. Mercury in the soil is known to have a strong affinity with SOM, mainly thiol and clay minerals, as it binds to colloids because of its large specific surface area and the presence of surface functional groups [19,21,29]. For this reason, the correlation between SOM, TOC and Hg content in the tested soils was determined (Table 3). A positive correlation was found between these components in the soil.

Correlation coefficients (r) between waste (n = 72) and soil (n = 20) properties and mercury content (Pearson’s test)

| Fraction | OM | TOC | TC | Hg | Hga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction | 1.0 | 0.518** | 0.543** | 0.587** | –0.128 | No data |

| OM | 1.0 | 0.946** | 0.936** | 0.020 | 0.689** | |

| TOC | 1.0 | 0.978** | –0.008 | 0.733** | ||

| TC | 1.0 | –0.016 | No data | |||

| Hg | 1.0 | 1.0 |

The bold values represent statistically significant correlation. **Correlation is significant at the ≤ 0.01 level.

- a

Correlation for soil samples.

5 Conclusions

The mercury content in the LFW was very low, similar to the natural content in soils. Obtained results show that the tested foundry waste was not contaminated with mercury, which should not negatively affect the environment during its landfilling or its reuse. An environmental problem with the use of LFW may be the high content of other heavy metals or toxic organic substances. The studies showed that the assessment of the mercury content in LFW, containing mainly SFS, may be omitted due to the very low content of this metal. However, when using LFW containing a high percentage of foundry dust, e.g. EAFD, it may pose an environmental problem, as shown in previous studies.

Fractional analysis showed that the tested waste was characterized by the highest percentage of sand fraction (<2 mm). The percentage of the finest fraction (clay fraction), which is responsible for the binding properties, an important parameter for building materials, was low. A high percentage of the largest fraction (>5.6 mm) consisted of metallic inclusions, sinter, slag and other materials was found. This fraction was also characterized by the largest differences in the content of OM due to the diversity of its composition. The highest percentage of OM for the finest (<0.2 mm) and the largest (>5.6 mm) fraction was found.

Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant correlation between the Hg content and other parameters of the tested waste. Low positive correlations between OM, TOC, TC and the particle size of the LFW were determined. In contrast to waste, a positive correlation between mercury content and SOM and TOC for the soil samples was found. This is probably due to the difference in the type of organic substances in waste and soil.

Abbreviations

- CHNS

-

carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur

- CRM

-

certified reference material

- EAFD

-

electric arc furnace dust

- LFW

-

landfilled foundry waste

- LOQ

-

limit of quantification

- OM

-

organic matter

- SFS

-

spent foundry sand

- SOM

-

soil organic matter

- TC

-

total carbon

- TOC

-

total organic carbon

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge foundry management for cooperation and Management Systems Office of the foundry for help with sampling.

-

Funding information: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or no-profit sectors. This study was supported by Opole University of Technology and the Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences from funds for statutory research.

-

Author contributions: Conceived and designed the study: M. B. and B. K. -K.; implemented the study: M. B. and B. K. -K.; analysed the data: M. B.; writing – original draft preparation: M. B.; writing – review and editing: M. B. and B. K. -K.; and supervision: B. K. -K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Kosa-Burda B, Kicińska A. Assessment of cadmium stability [Cd] in slags from the thermal processing plant waste in Krakow. E3S Web Conf; 2018. p. 44. Art UNSP No. 00075.10.1051/e3sconf/20184400075Search in Google Scholar

[2] Holtzer M, editor. Guide to best available techniques (BAT) guidelines for the foundry industry. Polish Ministry of the Environment; 2005 (in Polish). https://ippc.mos.gov.pl/ippc/custom/odlewnie.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Polish regulation of the minister of environment of 9 December 2014 on the waste catalog (Journal of Law 2014 item 1923).Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bożym M, Dąbrowska I. Directions of foundry waste management. In: Oszanca K, editor. Problems in environmental protection in the Opolskie Voivodeship – waste and sewage. Atmoterm; 2019. p. 24–41 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lindsay BJ, Logan TJ. Agricultural reuse of foundry sand. Rev J Res Sci Teach. 2005;2(1):3–12.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Dayton EA, Whitacre SD, Dungan RS, Basta NT. Characterization of physical and chemical properties of spent foundry sands pertinent to beneficial use in manufactured soils. Plant Soil. 2010;329:27–33. 101007/s11104-009-0120-0.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Beneficial reuse of foundry sand: a review of state practices and regulations Sector Strategies Division Office of Policy, Economics, and Innovation US Environmental Protection Agency and American Foundry Society Washington DC December 2002. Raport EPA 2002. Source: https://archiveepagov/sectors/web/pdf/reusebpdf.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Risk assessment of spent foundry sands in soil-related applications evaluating silica-based spent foundry sand from iron, steel, and aluminum foundries. EPA-530-R-14-003 October 2014. Raport EPA 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Thematic Strategy for Soil Protection plus Summary of the Impact Assessment COM 231. EU 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ji S, Wan L, Fan Z. The toxic compounds and leaching characteristics of spent foundry sands. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2001;132:347–64. 101023/A:1013207000048.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Dungan RS, Dees NH. The characterization of total and leachable metals in foundry molding sands. J Environ Manage. 2009;90:539–48. 101016/jjenvman200712004.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Sorvari J, Wahlstrom M. Industrial by-products. In: Worrell E, Reuter MA, Editors. Handbook of recycling: state-of-the-art for practitioners, analysts, and scientists, Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.; 2014. p. 231–53. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396459-5.01001-1.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Díaz Pace DM, Miguel RE, Di Roccoa HO, Anabitarte García F, Pardini L, Legnaioli S, et al. Quantitative analysis of metals in waste foundry sands by calibration free-laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim Acta Part B. 2017;131:58–65. 101016/jsab201703007.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Bożym M. Assessment of leaching of heavy metals from the landfilled foundry waste during exploitation of the heaps. Pol J Environ Stud. 2019;28(6):4117–26. 1015244/pjoes/99240.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zanetti M, Godio A. Recovery of foundry sands and iron fractions from an industrial waste landfill. Res Conserv Recycl. 2006;48:396–411. 101016/jresconrec200601008.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Siddique R, Kaur G, Rajor A. Waste foundry sand and its leachate characteristics. Res Conserv Recycling. 2010;54:1027–36. 101016/jresconrec201004006.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Miguel RE, Ippolito JA, Leytem AB, Porta AA, Noriega RBB, Dungan RS. Analysis of total metals in waste molding and core sands from ferrous and non-ferrous foundries. J Environ Manage. 2012;110:77–81. 101016/jjenvman201205025.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Bożym M. The study of heavy metals leaching from waste foundry sands using a one–step extraction. E3S Web Conf. 2017;19:1. 101051/e3sconf/20171902018.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kabata-Pendias A, Pendias H. Biogeochemistry of trace elements. Warsaw: PWN; 1999 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[20] Alves BSQ, Dungan RS, Carnin RLP, Galvez R, de Carvalho Pinto CRS. Metals in waste foundry sands and an evaluation of their leaching and transport to groundwater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014;225(5):1–11. 101007/s11270-014-1963-4.Search in Google Scholar

[21] O’Connor D, Hou D, Ok YS, Mulder J, Duan L, Wu Q, et al. Mercury speciation transformation and transportation in soils atmospheric flux and implications for risk management: a critical review. Env Intern. 2019;126:747–61. 101016/jenvint201903019.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Baran A, Czech T, Wieczorek J. Chemical properties and toxicity of soils contaminated by mining activity. Ecotoxicology. 2014;23:1234–44. 101007/s10646-014-1266-y.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Osterwalder S, Huang JH, Shetaya WH, Agnan Y, Frossard A, Frey B, et al. Mercury emission from industrially contaminated soils in relation to chemical microbial and meteorological factors. Env Pollut. 2019;250:944–52. 101016/jenvpol201903093.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Pasieczna A. Mercury in soils and river and stream sediments in the Silesia–Cracow region (Southern Poland). Biul Państwowego Inst Geolo. 2014;457:69–86 (in Polish).10.5604/08676143.1113257Search in Google Scholar

[25] Dołęgowska S, Michalik A. The use of a geostatistical model supported by multivariate analysis to assess the spatial distribution of mercury in soils from historical mining areas: Karczówka Mt, Miedzianka Mt and Rudki (south-central Poland). Env Monit Assess. 2019;191:302. 101007/s10661-019-7368-5.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Klojzy-Karczmarczyk B, Mazurek J. Soil contamination by mercury compounds in influence zone of coal-based power station. Energy Policy J. 2007;10(2):593–601 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[27] Antoszczyszyn T, Michalska A. The potential risk of environmental contamination by mercury contained in Polish coal mining waste. J Sustain Min. 2016;15:191–6. 101016/jjsm201704002.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Klojzy-Karczmarczyk B, Mazurek J. Contamination of subsurface soil layers with heavy metals around the southern ring road of Kraków. Przegląd Geolo. 2017;65:1296–1300 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[29] Klojzy-Karczmarczyk B. Variability of mercury content in various fractions of soils from the vicinity of Krakow ring road section. Ann Set Environ Prot. 2014;16:363–75 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[30] Klojzy–Karczmarczyk B, Mazurek J. Mercury in soils found in the vicinity of selected coal mine waste disposal sites. Energy Policy J. 2010;13(2):245–52 (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ottesen RT, Birke M, Finne TE, Gosar M, Locutura J, Reimann C, et al. Mercury in European agricultural and grazing land soils. Appl Geochem. 2013;33:1–12. 101016/japgeochem201212013.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Polish Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of September 1 2016 on to assess the pollution of the soil surface (Journal of Law 2016 item 1395).Search in Google Scholar

[33] Bożym M, Staszak D, Majcherczyk T. The influence of waste products from steel foundry dump on heavy metals and radionuclides contaminations in local soils. Prac ISCMOB. 2009;4:107–22. (in Polish).Search in Google Scholar

[34] Angelova VR, Akova VI, Ivanov KI, Licheva PA. Comparative study of titimetric methods for determination of organic carbon in soils compost and sludge. J Intern Sci Publ Ecol Saf. 2014;8:430–40.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Dungan RS, Kim JS, Weon HY, Leytem AB. The characterization and composition of bacterial communities in soils blended with spent foundry sand. Ann Microbiol. 2009;59(2):239–46.10.1007/BF03178323Search in Google Scholar

[36] Camps Arbestain M, Madinabeitia Z, Anza Hortala M, Macıas-Garcıa F, Virgel S, Macıas F. Extractability and leachability of heavy metals in Technosols prepared from mixtures of unconsolidated wastes. Waste Manage. 2008;28:2653–66. 101016/jwasman200801008.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Yao FX, Macías F, Santesteban A, Virgel S, Blanco F, Jiang X, et al. Influence of the acid buffering capacity of different types of Technosols on the chemistry of their leachates. Chemosphere. 2009;74:250–8.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.09.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Strobos JG, Friend JFC. Zinc recovery from baghouse dust generated at ferrochrome foundries. Hydrometallurgy. 2004;74(1–2):165–71. 101016/jhydromet200403002.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Salihoglu G, Pinarli V. Steel foundry electric arc furnace dust management: Stabilization by using lime and Portland cement. J Hazard Mater. 2008;153(3):1110–6. 101016/jjhazmat200709066.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Mymrin V, Nagalli A, Catai RE, Izzo RLS, Rose J, Romano CA. Structure formation processes of composites on the base of hazardous electric arc furnace dust for production of environmentally clean ceramics. J Clean Prod. 2016;137:888–94. jjclepro201607105.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Bożym M, Klojzy-Karczmarczyk B. The content of heavy metals in foundry dusts as one of the criteria for assessing their economic reuse. Miner Resour Manage. 2020;36(3):111–26. 10.24425/gsm.2020.133937.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kicińska A. Health risk assessment related to an effect of sample size fractions: methodological remarks. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. 2018;32(6):1867–87. 101007/s00477-017-1496-7v Search in Google Scholar

[43] Dańko R, Holtzer M, Dańko J. Investigations of physicochemical properties and thermal utilisation of dusts generated in the mechanical reclamation process of spent moulding sands. Arch Metall Mater. 2015;60(1):313–8.10.1515/amm-2015-0051Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Marta Bożym and Beata Klojzy-Karczmarczyk, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation