Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

-

Hassan A. Alhazmi

, Waquar Ahsan

Abstract

Depending upon the metal coordination capacity and the binding sites of proteins, interaction between metal and proteins leads to a number of changes in the protein molecule which may include the change in conformation, unfolding, overall charge, and aggregation in some cases. In this study, Cu(ii) and Ag(i) metal ions were selected to investigate aggregation of bovine serum albumin (BSA) molecule upon interaction by measuring the size and charge of the aggregates using nano-Zetasizer instrument. Two concentrations of metal ions were made to interact with a specific concentration of BSA and the size and zeta potential of BSA aggregates were measured from 0 min upto 18 h. The Cu(ii) and Ag(i) metal ions showed almost similar behavior in inducing the BSA aggregation and the intensity of peak corresponding to the normal-sized protein decreased with time, whereas the peak corresponding to the protein aggregate increased. However, the effect on zeta potential of the aggregates was observed to be different with both metal ions. The aggregation of protein due to interaction of different metal ions is important to study as it gives insight to the pathogenesis of many neurological disorders and would result in developing effective ways to limit their exposure.

1 Introduction

Copper (Cu) and Silver (Ag) are closely resembled coinage metals grouped together in group 11 and are being used for centuries as antimicrobial agents in healthcare systems and agriculture. Various copper- and silver-based agents are utilized increasingly nowadays, leading to increased exposure of these metal ions and therefore their toxicity. The underlying mechanisms of toxicity of these agents include protein aggregation, which could ultimately affect various important biological processes. In bacterial cell, these ions are shown to bind to important molecules, leading to disruption of their function [1]. Exposure to these metal ions often occurs via skin contact and inside the human body; these metal ions bind to various macromolecules including proteins inducing structural changes and aggregation which may result in health hazards.

These metal ions upon reaching the systemic circulation interact with plasma proteins leading to aggregation of proteins and increase in the coefficient of friction, thereby influencing the biointerface reactions. Studying effects of these metal ions on the protein adsorption and aggregation is vital in order to understand the untoward reactions and to design safer compounds. The protein-metal conjugates may lead to biocorrosion and have toxic effects on biological systems including neurodegenerative diseases [2]. Previously, Co(ii) and Cr(iii) metal ions were shown to aggregate albumin protein in phosphate buffer saline, leading to increase in the coefficient of friction in artificial joint prosthesis [3]. Another study revealed formation of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis due to interaction of trace metal ions with the albumin protein forming protein aggregates [4].

Several methods are reported in literature for the measurement of protein aggregation by metal ions including light scattering techniques, electrophoretic mobility, fluorescence spectroscopy, ultrafiltration, atomic absorption spectroscopy circular dischroism [2], etc. These methods either include costly instruments or expertise to perform the experiments as these techniques are much sophisticated. This study was aimed to utilize the Zetasizer instrument to measure the size of protein molecule before and after interaction with different concentrations of metal ions at different time intervals. To the best of our knowledge, no such study was conducted previously to measure the protein aggregation using the Zetasizer instrument. As we know, the size of bovine serum albumin (BSA) molecule remains around 10–13 nm in the native form and increases in case of aggregation. As the aggregates are formed, several protein molecules attach together forming polymeric protein molecules. Measuring the size of protein molecule after interaction with metal ions would give insight of the extent and type of aggregation and the metal-concentration at which the protein aggregation occurs can be determined. This method would provide preliminary information of the concentration of metal ions causing protein aggregation and will be useful in limiting the usage of metal-based compounds avoiding toxicity.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and instruments

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 99%), CuCl2, and AgNO3 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Steinhim, Germany). The ultrapure bidistilled water was produced in our lab. Zetasizer Nano Range (Malvern Panalytical, Ltd, Malvern, UK) was used to measure the nanosize and zeta potential of samples.

2.2 Preparation of solutions

2.2.1 Preparation of tris buffers

Two sets of tris buffers (20 mM, pH 7.4) were prepared for the study. For each set, accurately weighed (2.42 g) tris base was dissolved in 200 mL of ultrapure deionized double distilled water. For the preparation of tris HCl buffer, pH 7.4 was maintained using dilute hydrochloric acid and the volume was adjusted to 1,000 mL using ultrapure water. The other buffer, tris acetate, was prepared by adjusting the pH 7.4 using acetic acid and the final volume was maintained to 1,000 mL using ultrapure double distilled water. Tris HCl buffer was utilized to make solutions of Cu(ii) metal ions, whereas the tris acetate buffer was used for Ag(i) metal as the later is precipitated with the Cl− ions of HCl [5].

2.2.2 Preparation of BSA solution

The protein (BSA) solution (10 µM) was prepared by accurately weighing 33 mg of BSA powder in a 50 mL volumetric flask and making up the volume using the prepared tris HCl buffer (pH 7.4) for studying Cu(ii) ions and in tris acetate buffer (pH 7.4) for Ag(i) ions.

2.2.3 Preparation of metal solutions

Each metal salt was dissolved in the corresponding tris buffers to give stock solution of 1 mM which were diluted appropriately to obtain working solutions of concentrations 40 and 160 µM.

2.3 BSA-metal ion interaction

The BSA protein and each metal ion solution were added in equal proportions to obtain 1:4 and 1:16 concentrations, which were mixed properly and transferred to Zetasizer cells. The nanosize and zeta potential of the mixture were measured at 0 min immediately after mixing and the cells were incubated at 37°C with slow shaking and readings at different time intervals of 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 1,020, and 1,080 min were taken.

2.4 Measurement of nanosize and zeta potential using Zetasizer

The cells were placed in the Zetasizer instrument and the peaks of different molecular size (d.nm) with their relative intensities were obtained using the Malvern Zetasizer software version 7.01. Subsequently, zeta potential (mV) of all the samples were also measured using the software at different time intervals.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research does not include the use of human or animals.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Interaction of BSA with Cu(ii) ion

Two concentrations of Cu(ii) ion solutions, 40 and 160 µM, were mixed with 10 µM BSA solution in tris HCl buffer to give a concentration ratio of 1:4 and 1:16, respectively, which were incubated at 37°C and the size and zeta potential of samples were measured at 0, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 1,020, and 1,080 min time interval. The BSA blank solution was also analyzed to check the size and zeta potential of native BSA protein in the corresponding buffer. Table 1 summarizes the size (nm), peak intensity (%), and zeta potentials (mV) measured for all samples at different time points.

Interaction of BSA with different concentrations of Cu(ii)

| S. no. | Sample | Conc./ratio | Time (min) | Peak 1 size (nm) | Peak 1 intensity (%) | Peak 2 size (nm) | Peak 2 intensity (%) | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSA (Blank) | 10 µM | 0 | 13.18 | 87.5 | 348.3 | 9.7 | −15.5 |

| 2 | BSA + Cu(ii) | 1:4 | 0 | 12.88 | 62.7 | 367.2 | 25.5 | −17.3 |

| 30 | 12.89 | 72.2 | 185.2 | 28.3 | −17.6 | |||

| 60 | 11.94 | 55.9 | 219.1 | 40.6 | −16.4 | |||

| 120 | 11.66 | 30.3 | 281.8 | 64.7 | −19.1 | |||

| 180 | 8.26 | 8.8 | 292.4 | 78.5 | −22.6 | |||

| 240 | 9.92 | 8.4 | 260.7 | 81.4 | −24.9 | |||

| 300 | 10.22 | 7.8 | 187.8 | 83.0 | −23.6 | |||

| 1,020 | 9.61 | 5.0 | 192.7 | 91.5 | −23.9 | |||

| 1,080 | 15.01 | 4.8 | 210.7 | 92.0 | −23.2 | |||

| 3 | BSA + Cu(ii) | 1:16 | 0 | 11.70 | 93.6 | 243.0 | 6.4 | −10.7 |

| 30 | 10.14 | 61.4 | 141.5 | 34.6 | −18.2 | |||

| 60 | 10.05 | 55.9 | 145.4 | 38.8 | −20.7 | |||

| 120 | 8.84 | 62.1 | 127.4 | 40.8 | −18.9 | |||

| 180 | 9.86 | 53.2 | 158.0 | 42.1 | −18.6 | |||

| 240 | 10.23 | 52.2 | 142.0 | 44.4 | −20.8 | |||

| 300 | 10.74 | 49 | 144.6 | 47.0 | −21.3 | |||

| 1,020 | 9.88 | 32.4 | 257.0 | 51.3 | −20.7 | |||

| 1,080 | 9.96 | 32.8 | 173.8 | 64.5 | −20.5 |

The size of BSA protein at 10 µM concentration was measured in the tris HCl buffer and was found to be of 13.18 nm (87.5%) with a zeta potential of −15.5 mV, which showed that the BSA molecules were present in the normal size corresponding to the native protein (peak 1) and were segregated in the solution. Few agglomerates of BSA protein were also present which was evident by another peak (peak 2) corresponding to the size 348.3 nm of intensity 9.7%. When the prepared BSA solution was mixed with Cu(ii) solution in a ratio of 1:4, the change in the intensities of both peaks was observed immediately after mixing the solutions. The intensity of peak 1 corresponding to the normal-sized protein decreased markedly from 87.5 to 62.7% and the peak 2 corresponding to the protein aggregate showed an increase in intensity from 9.7 to 25.5%.

The zeta potential was also observed to be increased slightly at 0 min from −15.5 to −17.3 mV (more negative). Interestingly, this aggregation kept on increasing more or less with time as the intensity of peak 1 decreased and that of peak 2 increased (Figure 1). There was a sharp increase in the intensity of peak 2, and therefore, a decrease in peak 1 after 60 min, showing fast aggregation at this time. The increase in aggregation which was evident from the increase in the intensity of peak 2 and decrease in the intensity of peak 1 kept on increasing with time and became almost constant after 17 h. This showed that the time of exposure to the metal ions had marked effect on the aggregation of proteins and the accumulation of metal ions in the body for longer time would have more deleterious effects. The zeta potential of the BSA protein also changed with time as the charge became more negative after interaction with Cu(ii) ions, showing that the Cu(ii) ions after interacting with the amino acids present in BSA interacted with the surrounding anions increasing the negative charge of the protein. The negative charge kept on increasing as more and more Cl− ions coordinated with the Cu(ii) metal ions and became almost constant after some time, showing saturation of the surface.

Graph showing the interaction of BSA protein with Cu(ii) metal ion at 1:4 concentration ratio. An increase in the intensity of peak 2 corresponding to the BSA protein aggregate and decrease in the intensity of peak 1 corresponding to normal-sized native protein from 0 to 1,080 min (18 h) were observed.

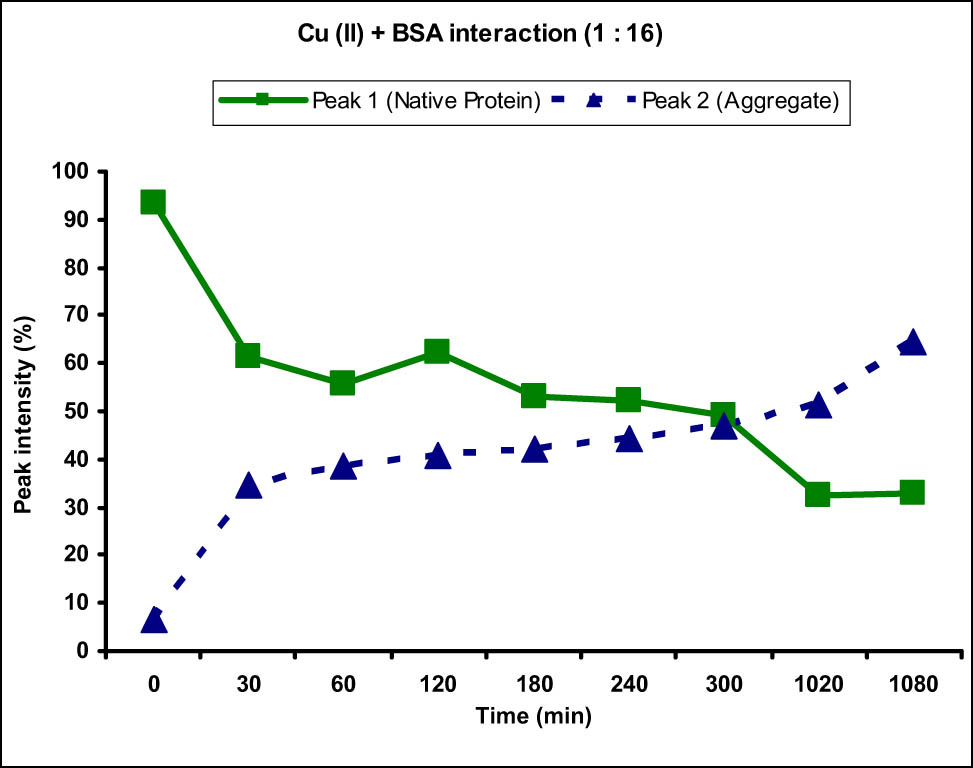

Similarly, the interaction of BSA with higher concentration of Cu(ii) was also studied to see the effects of concentration of metal ions on the aggregation of protein. BSA solution was mixed with 16 folds higher Cu(ii) solution in a ratio of 1:16 and the size and zeta potentials of BSA molecules were measured. When the Cu(ii) solution at 160 µM concentration was added to the BSA solution, immediately after the addition (at 0 min), interestingly an increase in the intensity of peak 1 and decrease in the intensity of peak 2 were observed (Figure 2). There was also a marked decrease (from −15.5 to −10.7 mV) in the zeta potential. This was attributed to the disaggregation of agglomerated protein molecules upon addition of higher concentration of Cu(ii) metal ions. This decrease in the zeta potential then led to the re-attraction of BSA molecules and formation of aggregates. This was evident from the data obtained for the sample measured at 30 min showing decrease in the intensity of peak 1 because of the decrease in the concentration of normal-sized protein and increase in the concentration of aggregates. The zeta potential also increased to −18.2 mV, showing complexation of Cu(ii) ions with the BSA protein and further coordination with surrounding anions. This behavior was consistent thereafter with increasing time as the intensity of peak corresponding to native size of protein kept on decreasing consistently with an increase in the intensity of peak 2, showing time-dependent increase in aggregation at this concentration.

Graph showing the interaction of BSA protein with Cu(ii) metal ion at 1:16 ratio. An increase in the intensity of peak 2 corresponding to the BSA protein aggregate and decrease in the intensity of peak 1 corresponding to normal-sized native protein from 0 to 1,080 min (18 h) were observed.

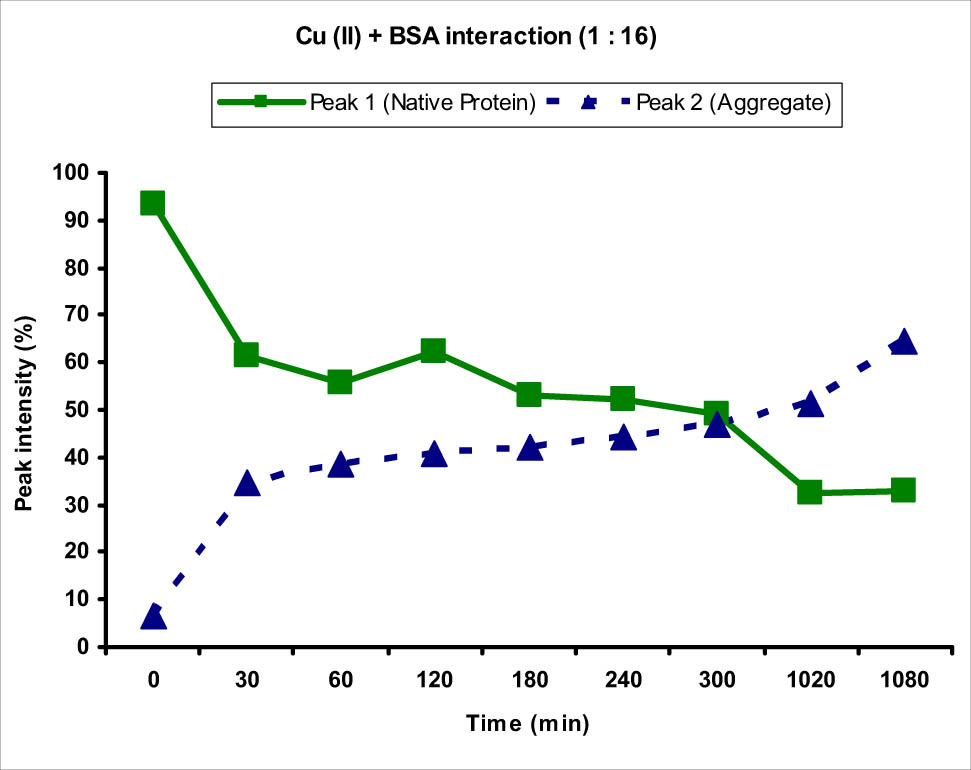

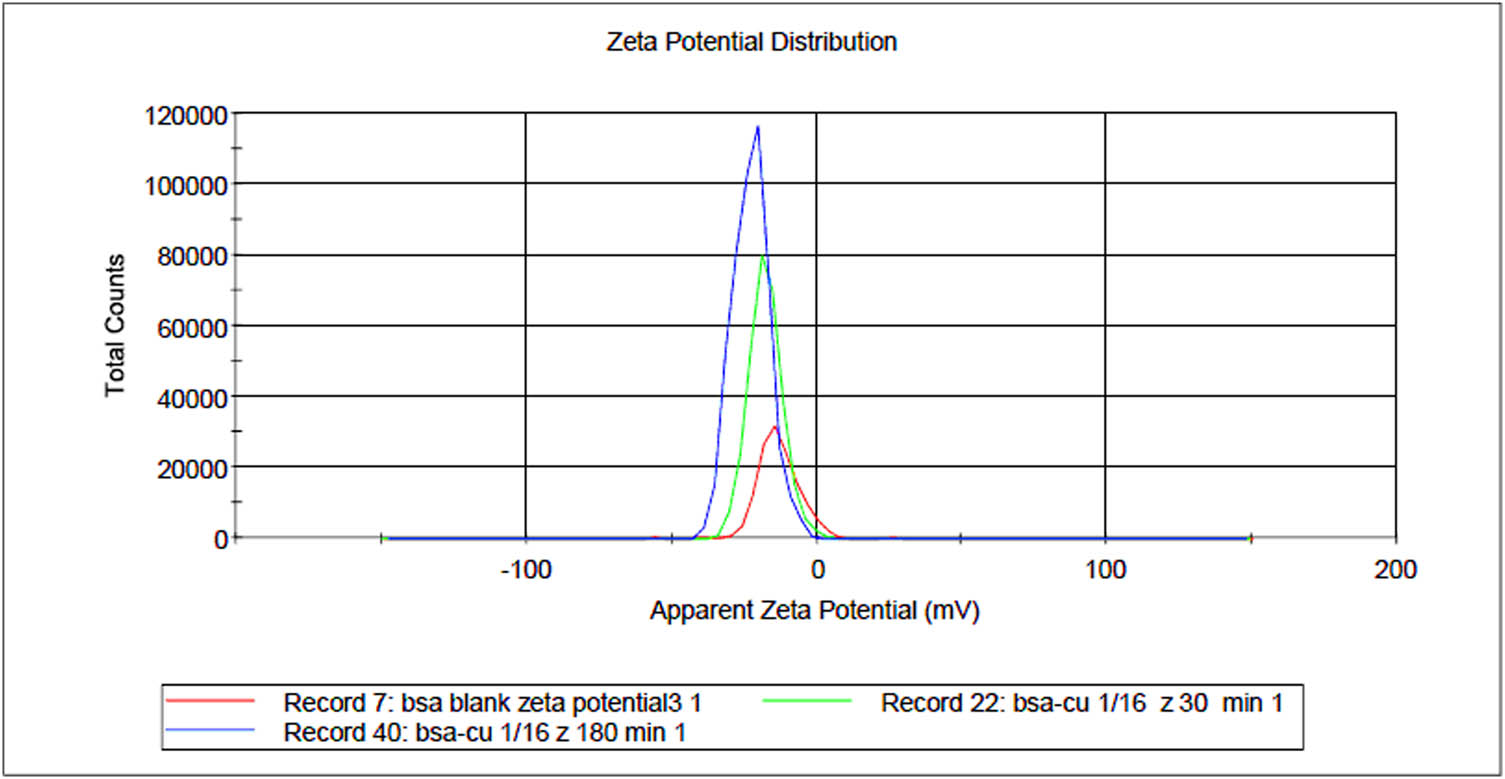

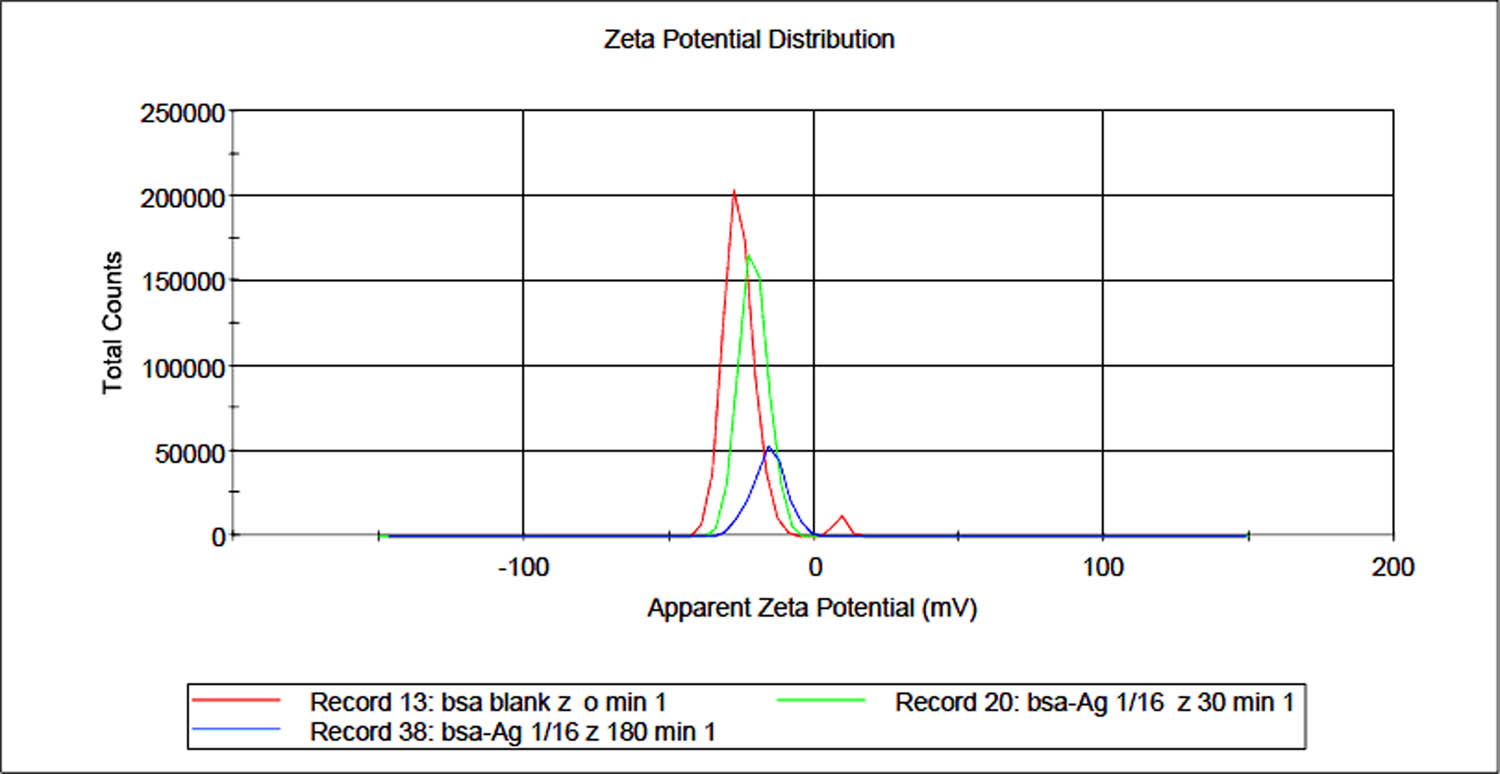

To study the effect of metal-complexation on the zeta potential of the BSA protein with time, the overlay graph of native-sized BSA protein together with the Cu(ii)-BSA complex at 30 and 180 min was studied (Figure 3) at 1:16 concentration. As evident from the figure, the zeta potential curve was shifted to the left hand side (becoming more negative) upon interaction with Cu(ii), which further shifted to the more negative side with time. Interestingly, the intensity or the total counts of peak increased upon complexation as well as with time, showing increased concentration of charged particles with time. Cu(ii), being a divalent metal ion, has more capacity to coordinate with the negatively charged BSA molecules forming more and more aggregates with time. It also has the capacity to bind with the surrounding anions present in the solution which further increased the negative charge.

Overlay graph of zeta potentials obtained for blank BSA and Cu(ii)-BSA complex at 30 and 180 min. The peaks can be seen shifted to the more negative side with an increase in intensity with time.

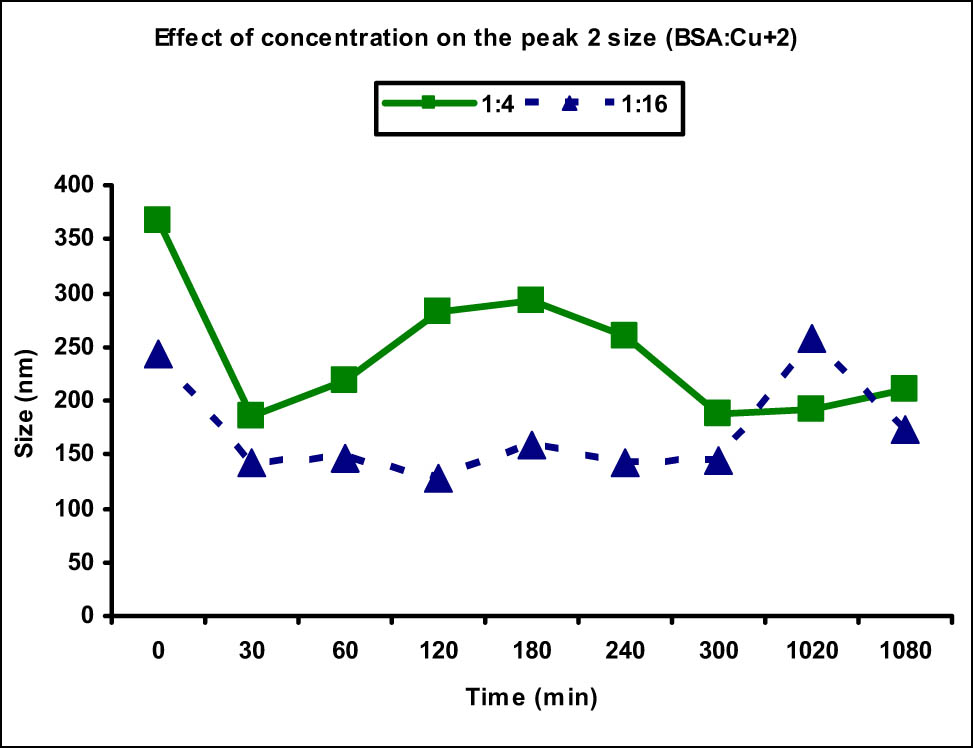

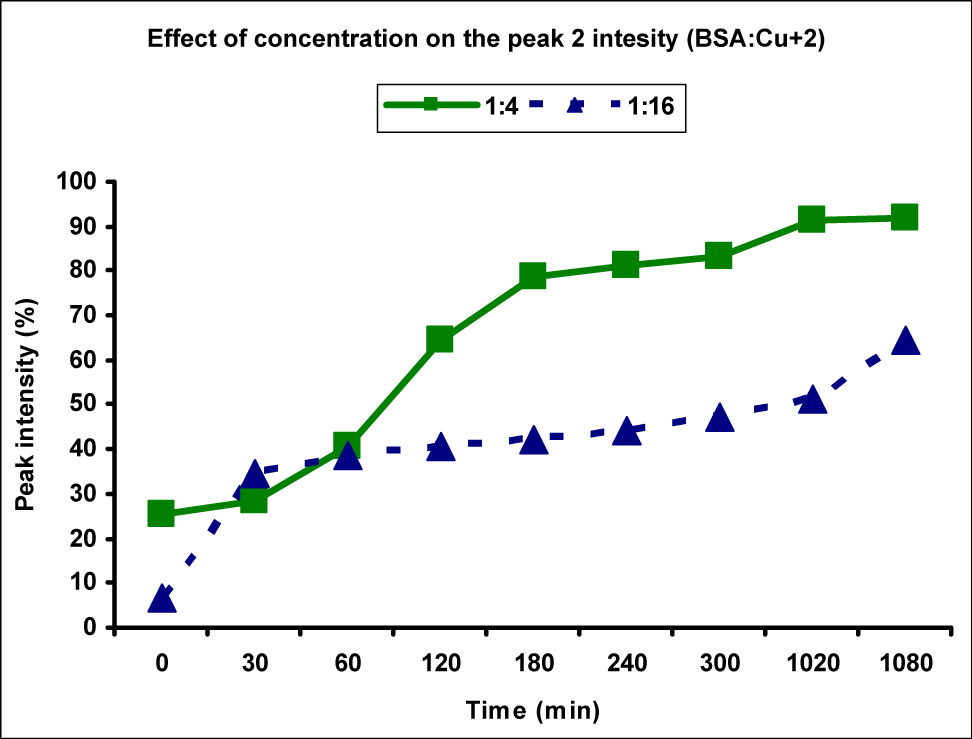

As far as the effect of concentration on the size and availability of protein aggregate is concerned, an interesting behavior was observed when the concentration of Cu(ii) metal ion was increased to 1:16. The size of aggregate in case of 1:4 as evident from the size distribution of peak 2 was found to be in the range of 185.2–367.2 nm, whereas the same was 127.4–257.0 nm, in case of 1:16 concentration ratio (Figure 4). It showed that the size of aggregate was comparatively smaller in case of higher concentration ratio. Similarly, the availability of aggregate which was evident from the intensity of peak 2 was found to be lesser in case of higher concentration as it increased to 64.5% at 18 h, whereas the intensity of peak 2 at 18 h in case of 1:4 ratio was 92% (Figure 5). It showed the presence of higher concentration of aggregates with faster aggregation at lower concentration of metal ions than the higher one. The concentration of normal-sized protein in case of 1:4 concentration was observed to be 4.8% at the end of 18 h, whereas 32.8% normal-sized protein was still available in case of 1:16 concentration at this time. The higher metal ion concentration saturated the binding sites of the BSA protein and the exposed amino acids coordinated with the excess metal ions keeping the exterior surface of protein hydrophilic, slowing down the formation of protein aggregate and aggregates of smaller size were formed.

Comparison of peak 2 (aggregate) size at different Cu(ii) metal ion concentrations. Increased aggregate size was observed at lower metal ion concentration (1:4) as opposed to the higher one (1:16).

Comparison of peak 2 (aggregate) intensity at different Cu(ii) metal ion concentrations. The peak 2 intensity, thereby the availability of aggregate, was found to be higher along with faster aggregation in case of lower metal ion concentration (1:4) as compared to the higher one (1:16).

3.2 Interaction of BSA with Ag(i) ion

Similarly, the effects of Ag(i) metal ions on the aggregation of BSA protein were also studied at different concentrations at various time points. Ag(i) ion solutions were prepared at concentrations of 40 and 160 µM and were mixed with 10 µM BSA solution to achieve the concentration ratio of 1:4 and 1:16, respectively, which were incubated at 37°C and the size and zeta potential of samples were measured at 0, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 1,020, and 1,080 min time interval. The average molecular size and zeta potentials measured for all BSA-Ag(i) samples are summarized in Table 2.

Interaction of BSA with different concentrations of Ag(i)

| S. no. | Sample | Conc./ratio | Time (min) | Peak 1 size (nm) | Peak 1 intensity (%) | Peak 2 size (nm) | Peak 2 intensity (%) | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSA (Blank) | 10 µM | 0 | 38.19 | 100.0 | — | — | −26.6 |

| 2 | BSA + Ag(i) | 1:4 | 0 | 11.01 | 18.1 | 205.5 | 57.9 | −25.1 |

| 30 | 10.17 | 19.6 | 179.0 | 77.8 | −28.4 | |||

| 60 | 11.52 | 21.3 | 180.5 | 76.1 | −28.5 | |||

| 120 | 10.22 | 16.5 | 186.2 | 78.6 | −28.2 | |||

| 180 | 9.63 | 15.8 | 190.3 | 80.6 | −28.3 | |||

| 240 | 9.95 | 11.0 | 159.0 | 83.7 | −28.2 | |||

| 300 | 8.39 | 8.7 | 224.1 | 84.6 | −28.8 | |||

| 1,020 | 9.87 | 8.1 | 213.8 | 86.5 | −25.3 | |||

| 1,080 | 9.09 | 7.2 | 204.2 | 91.8 | −28.1 | |||

| 3 | BSA + Ag(i) | 1:16 | 0 | 11.3 | 68.3 | 232.6 | 31.7 | −23.3 |

| 30 | 9.85 | 61.0 | 262.9 | 32.0 | −20.9 | |||

| 60 | 10.22 | 60.8 | 224.3 | 33.33 | −19.9 | |||

| 120 | 9.89 | 58.4 | 122.5 | 35.2 | −20.4 | |||

| 180 | 10.22 | 54.7 | 203.3 | 37.5 | −15.7 | |||

| 240 | 10.05 | 52.5 | 213.5 | 38.5 | −17.7 | |||

| 300 | 10.19 | 50.9 | 202.1 | 40.0 | −19.9 | |||

| 1,020 | 10.87 | 37.8 | 273.5 | 57.2 | −18.4 | |||

| 1,080 | 9.73 | 36.0 | 250.8 | 57.8 | −20.0 |

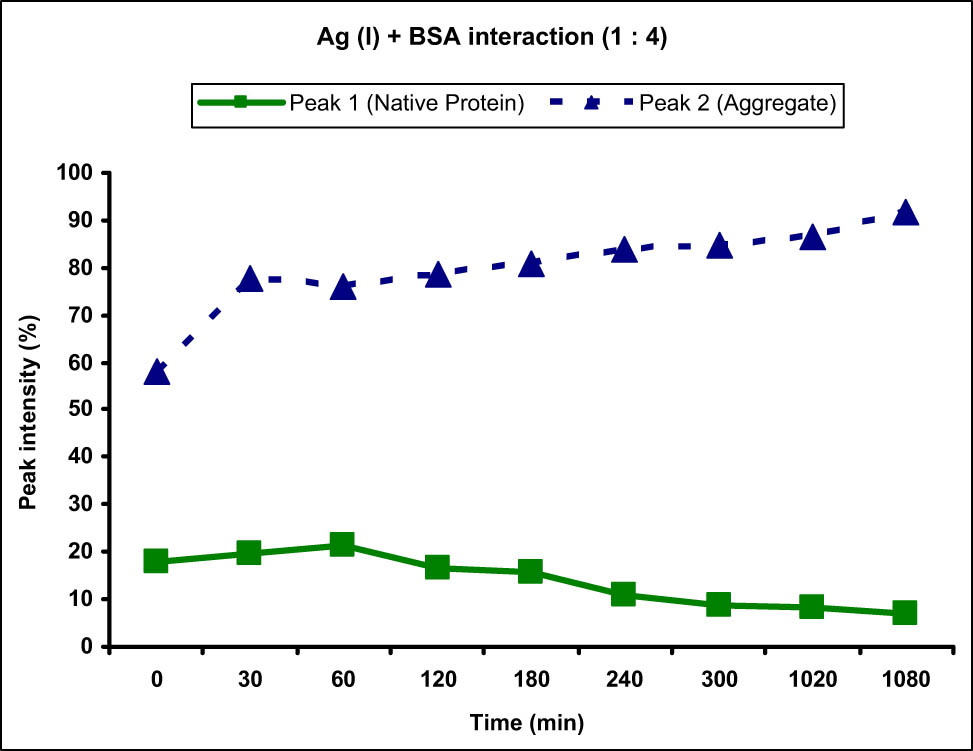

The BSA blank sample prepared in tris acetate buffer was also analyzed to measure the size and zeta potential. Interestingly, the size of BSA protein in tris acetate buffer was larger than that present in the tris HCl buffer and it was observed to be 38.19 nm with 100% intensity showing only single size distribution in the solution. The zeta potential of the sample was measured to be −26.6 mV, which was again higher than that obtained in case of tris HCl buffer showing greater repulsive forces between BSA molecules and that is why no agglomerates were obtained as opposed to the tris HCl buffer. Initially, BSA solution was mixed with Ag(i) metal ion solution in 1:4 ratio and the average size and zeta potential were measured at different time intervals. The aggregation observed due to Ag(i) ions was observed to be more or less similar to the Cu(ii) ions at 1:4 concentration and the formation of aggregates was observed immediately after mixing the two solutions at 0 min. Appearance of peak 2 of size 205.5 nm with 57.9% intensity was observed showing sudden aggregation of BSA molecules (Figure 6).

Graph showing the interaction of BSA protein with Ag(i) metal ion at 1:4 ratio. An increase in the intensity of peak 2 corresponding to the BSA protein aggregate and decrease in the intensity of peak 1 corresponding to normal-sized native protein from 0 to 1,080 min (18 h) were observed.

Importantly, the zeta potential in case of Ag(i) did not change considerably, showing that the Ag(i) ions did not coordinate with the surrounding ions and the total charge of the protein molecule remained unchanged. The peak 1 after addition of the metal ion solution changed considerably as the size also reduced to 11.01 nm and the intensity reduced greatly to 18.1%. This reduction in the intensity of peak 1 was consistent with time as it kept on decreasing and became 7.2% after 18 h of interaction. Similarly, the intensity of peak 2 corresponding to the aggregate increased with time and was observed to be 91.8% at the end of 18 h, showing time-dependent aggregation of BSA molecules in presence of Ag(i) metal ions (Figure 6). The zeta potential again did not change much and remained around −28 mV at all times.

When compared with the Cu(ii) metal ions at this concentration, the aggregation in case of Ag(i) was observed to be faster owing to the appearance (from 0%) of peak 2 of high intensity (57.9%) immediately after the addition of metal ion solution. In contrary, Cu(ii) ion showed lesser increase in the peak 2 intensity from 9.7 to 25.5% immediately after the addition of metal ions.

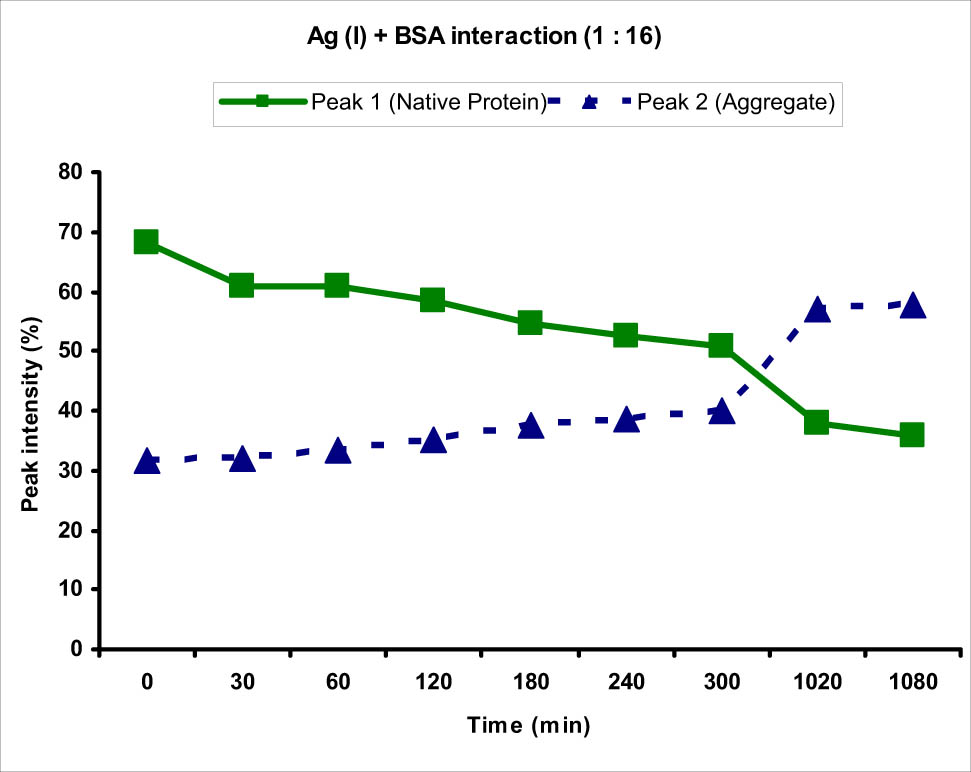

Similar behavior was observed when the protein and Ag(i) metal ion solutions were mixed in a ratio of 1:16. It showed appearance of peak 2 immediately after the addition of metal ion solution at 0 min, although the intensity of peak 2 was lesser than that obtained in case of 1:4. A distinct peak 2 of size 232.6 nm corresponding to the BSA aggregate was observed with an intensity of 31.7%. When the two solutions were incubated for longer time, the intensity of peak 1 decreased consistently with time showing the decrease in the concentration of normal-sized protein with an increase in the intensity of peak 2 showing increased concentration of aggregates (Figure 7). The zeta potential values in case of higher concentration at different time points were observed to be decreased from the zeta potential of blank BSA protein, which showed the increased attraction between BSA molecules upon interaction with the Ag(i) metal ions. This could be the reason for increased aggregate size at higher metal ion concentration. Also, Ag(i) is known to be reduced to nanoparticles by BSA protein which acts as a reducing agent. These nanoparticles have reduced zeta potential which, when combined with BSA protein, reduces zeta potential of the protein [6,7,8].

Graph showing the interaction of BSA protein with Ag(i) metal ion at 1:16 ratio. An increase in the intensity of peak 2 corresponding to the BSA protein aggregate and decrease in the intensity of peak 1 corresponding to normal-sized native protein from 0 to 1,080 min (18 h) were observed.

The effect of complexation with the Ag(i) metal ion on the zeta potential of BSA protein with time was also studied using the overlay graph of blank BSA with Ag(i) + BSA at 30 and 180 min (Figure 8). Interestingly, opposite effect of what was seen in case of Cu(ii) was observed in case of Ag(i) ions as the zeta potential of BSA molecule tends to decrease or become less negative upon complexation with Ag(i) ions which further decreased and shifted to the right hand side or less negative (towards zero) side with time. Also, the intensity or the total counts of the corresponding peaks decreased in case of complex and further decreased with increase in time. It showed that the concentration of charged particles decreased with time. This further supported the reason that more and more Ag(i) ions got reduced by BSA with time and the Ag(i) complexed with BSA could not coordinate with other anions and the concentration of charged particles decreased with time.

Overlay graph of zeta potentials obtained for blank BSA and Ag(i)-BSA complex at 30 and 180 min. The peaks can be seen shifted to the less negative side with a decrease in intensity with time.

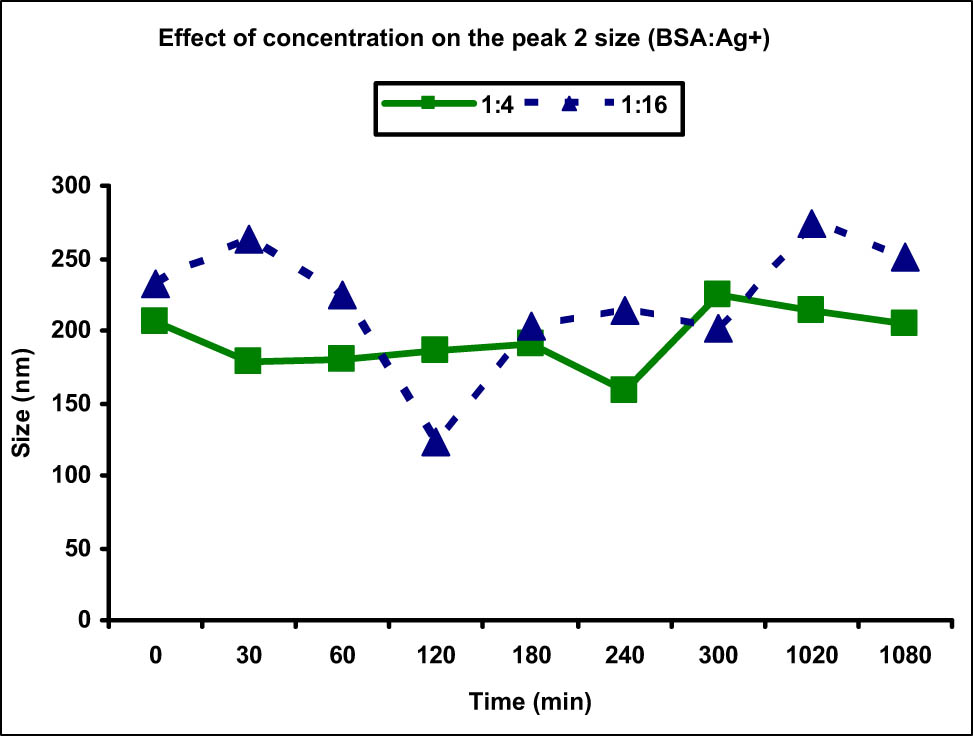

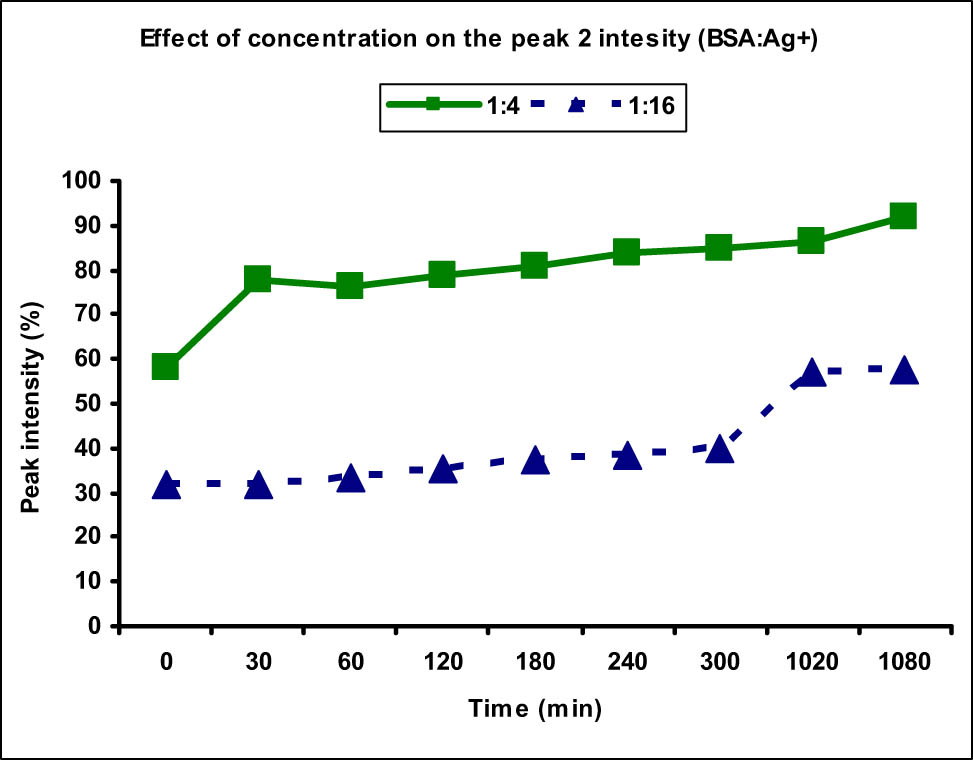

To study the effect of concentration on the peak size and intensity of BSA aggregates, the data obtained for the concentration 1:4 and 1:16 were compared and a slightly different behavior was observed as compared to the Cu(ii) metal ions. The size distribution of peak 2 which was corresponding to the BSA aggregates was measured to be in the range of 159.0–224.1 nm in case of 1:4 concentration, whereas it was in the range 122.5–273.5 nm for 1:16 concentration. At most of the time points (except two), the size of peak 2 was greater for higher concentration than that of the lower one in contrast to the behavior seen in Cu(ii) ions (Figure 9). This showed that increasing the concentration of Ag(i) metal ions led to an increase in the size of the aggregates. However, the effect of concentration on the intensity of peak 2 was similar to that observed for Cu(ii) ions as increasing the concentration decreased the rate of aggregation and reduced intensities were observed at all time points (Figure 10). The highest intensity observed at 18 h in case of 1:4 concentration was 91.8%, whereas it was merely 57.8% for higher concentration at the same time point. There was 7.2% normal-sized native protein remaining at the end of 18 h for concentration ratio 1:4 as compared to 36% in case of 1:16 showing greater aggregation at lower concentration with time.

Comparison of peak 2 (aggregate) size at different Ag(i) metal ion concentrations. Increased aggregate size was observed at lower metal ion concentration (1:4) as compared to the higher one (1:16).

Comparison of peak 2 (aggregate) intensity at different Ag(i) metal ion concentrations. The peak 2 intensity, thereby the availability of aggregate, was found to be higher along with faster aggregation in case of lower metal ion concentration (1:4) as compared to the higher one (1:16).

A number of methods have been developed to analyze the interactions of metal ions/metallodrugs with serum albumin protein including fluorescence and 3D fluorescence spectroscopy, UV-visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), and quantum dot-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry (QALDI-MS) [9]. Previously, our research group has also been involved in investigating the binding interaction of various metal ions and drugs with serum proteins such as human serum albumin (HSA) and BSA using cost-effective and efficient techniques [5,10,11,12,13]. These techniques revealed that the exogenous and endogenous ligands including drugs/metallodrugs generally bind to the binding sites present in the subdomains IA and IIA of the albumin protein which are also known as Sudlow’s site I and II, respectively. Metal ions are known to covalently bind to the macromolecules including proteins, DNA, and enzymes present in our body, which might have inhibitory effects on their functioning leading to apoptosis, necrosis, and cell death. Interaction of metal ions with serum proteins leads to the disruption of disulfide bonds present in the protein leading to change in its secondary structure. The α-helix component of the secondary structure of protein is partially lost upon interaction with metal ions, leading to partial unfolding of the protein [14].

The polarity around the tryptophan residue present at the binding site of albumin protein changes due to these interactions [15,16] as the distance between the amino acid residues changes. Various types of interactions between metal ions and the serum protein include rearrangements, energy transfer, and collision quenching processes [14,15,16]. Previously, several divalent metal ions complexes were prepared using Cu(ii), Zn(ii), Ni(ii), Co(ii), and Pt(ii) metal ions and their interaction with BSA protein was studied [17,18,19]. It was found that the specificity of binding interactions between the BSA protein and the metal ions as ligands was affected by the planarity of ligands. It was observed that these metal ions bind specifically to the Trp134 residue present on the surface of the protein being the most accessible residue for the metal ions. Metal ions bind preferentially to the subdomain IIA present in the Sudlow’s site I of the BSA protein [20].

Studying the aggregation of protein due to interaction with different metal ions is important to determine as several evidences are there which indicate their role in the pathogenesis of a number of diseases. For instance, the formation of fibrils by β-amyloid peptide, which is the major component of plaque in brain, is accelerated by these metal ions owing to the formation of oligomeric aggregates of these proteins increasing its toxicity [21,22]. Similarly, neurodementia disease is characterized by the abnormal deposition of protein aggregates in brain due to the exposure of metal ions leading to the neurological disorder [23,24]. These metal ions, therefore, have important consequences on the aggregation and/or unfolding of the protein and many studies are being devoted to determine the effects of these metal ions on peptide and protein aggregation and elucidating the mechanisms involved [25,26,27,28]. The results obtained indicated that the aggregation and unfolding process largely depends on the types and nature of proteins and metal ions and their respective concentrations.

Metal ions can act as promoters or inhibitors of the protein aggregation process depending upon the protein/metal ion ratio and the binding mechanism of metal ions [29,30,31,32]. Moreover, the presence of metal ions can significantly affect the conformation of proteins and therefore the aggregation which may ultimately lead to the formation of protein gels [33,34,35]. Importantly, the protein aggregation process is supposed to be lesser in case of monovalent ions than the divalent metal ions as they can form bridges and provide electrostatic attractions between the negatively charged species of surrounding protein molecules [36,37].

The repulsive forces between the charged protein molecules are decreased or lost which results in the proximity of protein molecules and the formation of non-covalent interactions of low energy [33]. The metal ions and proteins, however, interact with specific bonding forces and the binding sites present on the protein molecule are characterized previously [38,39,40]. The binding mode of metal ions is an important consideration in studying the formation of metal-protein complex as a metal ion can bind to the protein in two specific ways, intermolecular and intramolecular. In case of intramolecular binding, the geometry around the metal ions is in such a way that the atoms which participate in the coordination with metal ions are all present in the same protein molecule. Therefore, the intermolecular interactions are not favored; however, the coordination with metal ions can change the secondary structure of the protein. The amino acid residues present in the protein molecule including Tyrosine (Tyr) and Tryptophan (Trp) also show a change in the microenvironments of their side chains due to these interactions. On the other hand, intermolecular binding involves the formation of intermolecular bridges between the metal ion and protein molecules and the aggregation process depends upon the coordination capacity of the metal ions.

4 Conclusion

The Zetasizer instrument successfully measured the size and zeta potential of the BSA protein molecules before and after interaction with different concentrations of metal ions. The Zetasizer instrument has many advantages over other techniques as it is a very simple and cost-effective technique which does not require sample preparation steps and expertise to perform the experiment. The instrument was sensitive in detecting the size and zeta potential of the protein molecules and gave a preliminary idea about the metal-concentration and time at which the protein aggregation could take place in biological systems. Both Cu(ii) and Ag(i) metal ions led to the aggregation of BSA protein at different concentrations at different time points which were evident by the increase in the size of protein. Metal ions at lower concentrations exposed for longer time were observed to increase the aggregation as compared to the metal ions at higher concentration. As protein aggregation is known to be the major reason for a number of neurological disorders, measuring the concentration of metal ions which could cause the protein aggregation would help us in getting limited exposure to these metal ions.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, Jazan University, Jazan, for the financial assistance to carry out this study.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, Jazan University, Jazan, under Future Scientist Program no. 7 (Grant number: FS10-023).

-

Author contributions: H.A.A. – conceptualization, formal analysis, resources; W.A. – methodology, writing – original draft; A.M.M.I. – funding acquisition, writing – original draft; R.A.Y.K. – methodology, investigation; Z.A.A.H. – methodology, investigation; A.Y.F.S. – methodology, investigation; N.S. – writing – review and editing, software, validation; M.A.L. – resources, funding acquisition; A.N. – supervision, project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interests involved.

-

Data availability statement: Data associated with the study are available with the authors and can be produced upon request.

References

[1] Tambosi R, Liotenberg S, Bourbon ML, Steunou AS, Babot M, Durand A, et al. Silver and copper acute effects on membrane proteins and impact on photosynthetic and respiratory complexes in bacteria. mBio. 2018;9(6):e01535-18. 10.1128/mBio.01535-18.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Hedberg YS, Dobryden I, Chaudhary H, Wei Z, Claesson PM, Lendel C. Synergistic effects of metal-induced aggregation of human serum albumin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019;173:751–8. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.10.061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Hedberg YS, Pettersson M, Pradhan S, Wallinder IO, Rutland MW, Persson C. Can cobalt(ii) and chromium(iii) ions released from joint prostheses influence the friction coefficient? ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1(8):617–20. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00183.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Roos PM, Vesterberg O, Syversen T, Flaten TP, Nordberg M. Metal concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;151(2):159–70. 10.1007/s12011-012-9547-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Alhazmi HA, Nachbar M, Albishri HM, El-Hady DA, Redweik S, El Deeb S, et al. A comprehensive platform to investigate protein–metal ioninteractions by affinity capillary electrophoresis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;107:311–7. 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.01.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Morales-Sánchez JE, Guajardo-Pacheco J, Noriega-Treviño M, Quintero-González C, Compeán-Jasso M, López-Salinas F, et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using albumin as a reducing agent. Mater Sci Appl. 2011;2(6):578–81. 10.4236/msa.2011.26077.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Abdelhamid HN, Wu H-F. Proteomics analysis of the mode of antibacterial action of nanoparticles and their interactions with proteins. TrAC Trend Anal Chem. 2015;65:30–46. 10.1016/j.trac.2014.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Abdelhamid HN, Huang Z, El-Zohry AM, Zheng H, Zou X. A fast and scalable approach for synthesis of hierarchical porous zeolitic imidazolate frameworks and one-pot encapsulation of target molecules. Inorg Chem. 2017;56(15):9139–46. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01191.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Abdelhamid HN, Wu H-F. Monitoring metallofulfenamic–bovine serum albumin interactions: a novel method for metallodrug analysis. RSC Adv. 2014;4:53768–76. 10.1039/C4RA07638A.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Alhazmi HA. FT-IR Spectroscopy for the identification of binding sites and measurements of the binding interactions of important metal ions with bovine serum albumin. Sci Pharm. 2019;87:5. 10.3390/scipharm87010005.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Alhazmi HA, Al Bratty M, Javed SA, Lalitha KG. Investigation of transferrin interaction with medicinally important noble metal ions using affinity capillary electrophoresis. Pharmazie. 2017;72:243–8. 10.1691/ph.2017.6170.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Alhazmi HA, Al Bratty M, Meraya AM, Najmi A, Alam MS, Javed SA, et al. Spectroscopic characterization of the interactions of bovine serum albumin with medicinally important metal ions, platinum(iv), iridium(iii) and iron(ii). Acta Biochim Pol. 2021;68(1):99–107. 10.18388/abp.2020_5462.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Bratty MA. Spectroscopic and molecular docking studies for characterizing binding mechanism and conformational changes of human serum albumin upon interaction with Telmisartan. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28(6):729–36. 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.04.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Samari F, Hemmateenejad B, Shamsipur M, Rashidi M, Samouei H. Affinity of two novel five-coordinated anticancer Pt(ii) complexes to human and bovine serum albumins: a spectroscopic approach. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:3454–64. 10.1021/ic202141g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ehteshami M, Rasoulzadeh F, Mahboob S, Rashidi MR. Characterization of 6-mercaptopurine binding to bovine serum albumin and its displacement from the binding sites by quercetin and rutin. J Lumin. 2013;135:164–9. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2012.10.044.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jalali F, Dorraji PS, Mahdiuni H. Binding of the neuroleptic drug gabapentin to bovine serum albumin: Insights from experimental and computational studies. J Lumin. 2014;148:347–52. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2013.12.046.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Sathyadevi P, Krishnamoorthy P, Butorac RR, Cowley AH, Bhuvanesh NS, Dharmaraj N. Effect of substitution and planarity of the ligand on DNA/BSA interaction free radical scavenging and cytotoxicity of diamagnetic Ni(ii) complexes: a systematic investigation. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:9690–702. 10.1039/c1dt10767d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Sathyadevi P, Krishnamoorthy P, Jayanthi E, Butorac RR, Cowley AH, Dharmaraj N. Studies on the effect of metal ions of hydrazone complexes on interaction with nucleic acids bovine serum albumin and antioxidant properties. Inorg Chim Acta. 2012;384:83–96. 10.1016/j.ica.2011.11.033.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Krishnamoorthy P, Sathyadevi P, Cowley AH, Butorac RR, Dharmaraj N. Evaluation of DNA binding DNA cleavage protein binding and in vitro cytotoxic activities of bivalent transition metal hydrazone complexes. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:3376–87. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Asadi M, Asadi Z, Zarei L, Sadi SB, Amirghofran Z. Affinity to bovine serum albumin and anticancer activity of some new water-soluble metal Schiff base complexes. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2014;133:697–706. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.05.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Mantyh PW, Ghilardi JR, Rogers S, De Masters E, Allen CJ, Stimson ER, et al. Aluminum, iron, and zinc ions promote aggregation of physiological concentrations of β-amyloid peptide. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1171–4. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03639.x.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, Paradis M, Vonsaltel J, Gusella JF, et al. Rapid induction of Alzheimer A amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265:1464–7. 10.1126/science.8073293.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kelly JW. The alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins and their multi-step assembly pathways. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:101–6. 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80016-x.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Uversky VN, Fink AL. Conformational constraints for amyloid fibrillation: the importance of being unfolded. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1698:131–53. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.12.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Suzuki K, Miura T, Takeuchi H. Inhibitory effect of copper(ii) on zinc(ii)-induced aggregation of amyloid beta-peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:991–6. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5263.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Streltsov VA, Titmuss SJ, Epa VC, Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Varghese JN. The structure of the amyloid-β peptide high-affinity copper ii binding site in Alzheimer disease. Biophys J. 2008;95(3447):56. 10.1529/biophysj.108.134429.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Danielsson J, Pierattelli R, Banci L, Graslund A, High-resolution NMR. studies of the zinc-binding site of the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. FEBS J. 2007;274:46–59. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05563.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Wang L, Colon W. Effect of zinc, copper, and calcium on the structure and stability of serum amyloid A. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5562–9. 10.1021/bi602629y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Fox JH, Kama AJ, Lieberman G, Chopra R, Dorsey K, Chopra V, et al. Mechanisms of copper ion mediated Huntington’s disease progression. PLoS One. 2007;2:e334. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000334.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Garai K, Sengupta P, Sahoo B, Maiti S. Selective destabilization of soluble amyloid beta oligomers by divalent metal ions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;354:210–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Navarra G, Leone M, Militello V. Thermal aggregation of β-lactoglobulin in presence of metal ions. Biophys Chem. 2007;131:52–61. 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Militello V, Navarra G, Foderà V, Librizzi F, Vetri V, Leone M. Thermal aggregation of proteins in the presence of metal ions. In: San Biagio PL, Bulone D, editors. Biophysical Inquiry into Protein Aggregation and Amyloid Diseases. Kerala, India: Transworld Research Network; 2008. p. 181–232.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Remondetto GE, Subirade M. Molecular mechanisms of Fe2+-induced -lactoglobulin cold gelation. Biopolymers. 2003;69:461–9. 10.1002/bip.10423.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Haque ZZ, Aryana KJ. Effect of copper, iron, zinc and magnesium ions on bovine serum albumin gelation. Food Sci Technol Res. 2002;8:1–3. 10.3136/fstr.8.1.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Navarra G, Giacomazza D, Leone M, Librizzi F, Militello V, San Biagio PL. Thermal aggregation and ion-induced cold-gelation of bovine serum albumin. Eur Biophys J. 2009;38:437–6. 10.1007/s00249-008-0389-6.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Bryant CM, McClements DJ. Molecular basis of protein functionality with special consideration of cold-set gels derived from heat-denatured whey. Trends Food Sci Tech. 1998;9:143–51. 10.1016/S0924-2244(98)00031-4.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Stellato F, Menestrina G, Serra MD, Potrich C, Tomazzolli R, Meyer-Klaucke W, et al. Metal binding in amyloid beta-peptides shows intra- and inter-peptide coordination modes. Eur Biophys J. 2006;35:340–51. 10.1007/s00249-005-0041-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Suzuki K, Miura T, Takeuchi H. Inhibitory effect of copper(ii) on zinc(ii)-induced aggregation of amyloid beta-peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:991–6. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5263.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Miura T, Suzuki K, Kohata N, Takeuchi H. Metal binding modes of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide in insoluble aggregates and soluble complexes. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7024–31. 10.1021/bi0002479.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Morante S, Gonzalez-Iglesias R, Potrich C, Meneghini C, Meyer-Klaucke W, Menestrina G, et al. Inter- and intra-octarepeat Cu(ii) site geometries in the prion protein – Implications in Cu(ii) binding cooperativity and Cu(ii)-mediated assemblies. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11753–9. 10.1074/jbc.M312860200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Hassan A. Alhazmi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation