Abstract

Cerebral ischemia is an extremely complex disease that can be caused by a variety of factors. Cerebral ischemia can cause great harm to human body. Sevoflurane is a volatile anesthetic that is frequently used in clinic, and has a lot of advantages, such as quick induction of general anesthesia, quick anesthesia recovery, no respiratory tract irritation, muscle relaxation, and small cycle effect. The mechanism of sevoflurane preconditioning or post-treatment induction is poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to illustrate the mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury and also provide theoretical guidance for future research.

Abbreviations

- Akt

-

protein kinase B

- EAA

-

excitatory amino acid

- IL-1β

-

interleukin-1β

- iNOS

-

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- Nrf2

-

nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- TGF-β2

-

transforming growth factor-β2

- TNF-α

-

tumor necrosis factor-α

1 Introduction

Sevoflurane is a generally used inhalational anesthetic in clinic that can induce ischemia tolerance both in vivo and in vitro [1,2]. It is the most commonly used general anesthetic in pediatric populations and is widely used as general anesthesia in Japan, the United States, and Europe. Sevoflurane was listed in China in 2005 and has been widely used in surgery [3].

Cerebral ischemia is characterized by obstruction of blood flow to the brain and is the leading cause of death and chronic disability worldwide [4]. Cerebrovascular disease may lead to cerebral ischemia, which is caused by damage to brain tissue. Cerebral ischemia is not only the cause of high mortality and disability but also a great concern for human health [5]. Since the etiology of cerebral ischemia is complex and the treatment is hard, there are no effective drugs available for treatment [6]. There are three main pathological types of cerebral ischemia [7]: ischemic stroke [8], primary intra-cerebral hemorrhage [9], and subarachnoid hemorrhage [6]. The main reason for ischemia–reperfusion injury is not the ischemia itself, but the excess free radicals that attack cells in this part of the tissue recovering from the obstruction of the blood supply. Cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury mainly involves free radical formation in excess, toxic effects mediated by excitatory amino acid (EAA), increase in blood glucose levels, calcium ion overload in the cell, and damage to nerve function and inflammation [10].

In this study, sevoflurane was extensively used in various stages of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Both sevoflurane preconditioning and postprocessing can alleviate cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury to a certain extent, especially sevoflurane has a significant effect in the regeneration and repair of nerve cells [11] and downregulation of the expression of inflammatory factors, sevoflurane has a significant effect. Previous researchers have found that sevoflurane pretreatment may delay the protection of focal cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury by reducing the levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1β) [12,13]. Recently, a study [14] has found that sevoflurane pretreatment up-regulates the expression of transforming growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2), vascular endothelial growth factor-A, and CD34, as well as the phosphorylation level of Smad3. TGF-β2 inhibitor treatment can inhibit the expression of TGF-β2, vascular endothelial growth factor-A and CD34, and the phosphorylation level of Smad3, which suggests that sevoflurane pretreatment can alleviate brain injury in rats with ischemia–reperfusion injury by activating TGF-β2/Smad3 signaling pathway. Sevoflurane postprocessing also has a consider able protective effect on cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rat brain tissue [15,16], and its mechanism may be to reduce the release of inflammatory factors, reduce inflammation and oxidative stress response, thus inhibiting apoptosis. In addition, sevoflurane post-processing can significantly improve the learning and memory impairment and the degree of cerebral infarction in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats [17].

2 Properties of sevoflurane

2.1 Physicochemical properties of sevoflurane

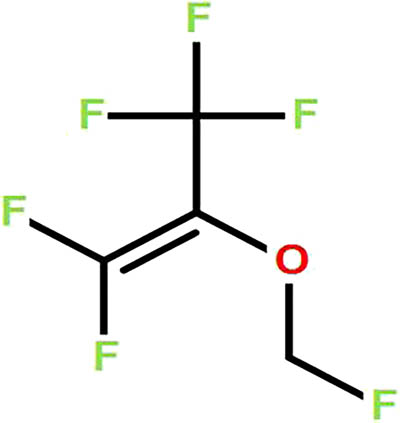

The chemical name of sevoflurane is 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-(fluorine methoxy)propane. The chemical structure is given in Figure 1.

Chemical structure of sevoflurane.

The molecular formula of sevoflurane is C4H3F7O. It is a colorless and aromatic liquid that is volatile and non-flammable and is stable in heat and strong acids. Sevoflurane causes no irritation to the respiratory tract. The effect of sevoflurane on hemodynamics and autonomic respiration was also small. The blood/gas distribution coefficient of sevoflurane is 0.69 and it has a low boiling point (58.6℃) with a relative molecular weight of 200.05 [18].

2.2 Physiological disposition and metabolic process in vivo of sevoflurane

Sevoflurane, in gas form, enters the bloodstream through the alveolar absorption, via blood circulation, into the brain. The produced effect is based on the quantity effect. The drug works through the processes of gas-blood and blood-brain, which transfers alveolar gas through the blood to brain tissue. After inhaling, sevoflurane plays a role in the nervous system.

With the advantages of fast onset, good circulation stability, high safety, and less adverse reactions, sevoflurane is used in the anesthesia induction of craniocerebral surgery [19]. The study has shown that [20] in patients undergoing craniotomy for acute intracranial hemorrhage, compared with total intravenous anesthesia, levels of serum C-reactive protein, serum S-100 β and neuron-specific enolase, inflammation-related factors and intracranial pressure of the patients with 1–2% sevoflurane combined with intravenous anesthesia were significantly decreased, which suggested that sevoflurane could inhibit the inflammatory reaction, and had brain-protective effect. Additionally, in the non-cardiac surgery of elderly patients with coronary heart disease, sevoflurane has little effect on the patient’s hemodynamics and myocardial damage. It can effectively improve cardiac function, reduce the incidence of adverse reactions, and has high safety performance [21].

There are two ways to expel sevoflurane from the body. Most of the sevoflurane can be discharged directly through the lungs. A small fraction of sevoflurane needs to be bio-converted and excreted via the kidney. Since liposoluble sevoflurane cannot be excreted through urine, it is obligatory to produce water-soluble hexafluoro-2-propanol which oxidizes to inorganic fluoride ions with the help of cytochrome P450-2E1 in the liver [3].

2.3 Inhalation and induction methods of sevoflurane

Sevoflurane inhalation induction is commonly used in two clinical methods, that is lung capacity breathing induction and tidal volume breathing induction. The lung capacity breathing induction method is the one where the patients are induced with maximal inhalation and breathlessness; when patients cannot tolerate breathlessness, then again deep inhalation and breathlessness. The tidal volume breathing induction method allows the patient to breathe normally [22].

2.4 Sevoflurane was used in combination with different drugs

Sevoflurane is administered via a mixture of sevoflurane and oxygen or oxygen–nitrous oxide. The anesthetic concentration of sevoflurane is 8% [23]. Nitric oxide is a gas anesthetic used in clinic. The anesthetic effect of the drug itself is low; however, its combination with other volatile drugs can reduce the anesthetic minimum alveolar concentration, and thus exert a beneficial effect [24]. Sevoflurane can also be administered with oxygen or oxygen–nitrous oxide, after the amount of intravenous anesthesia necessary for sleep is reached. The administration of narcotic drugs is usually performed with oxygen or oxygen–nitrous oxide. In the case of patients, the minimum effective concentration is used to maintain the anesthetic status below 4.0%. The medication is usually stopped three minutes before the end of the operation [25].

The use of propofol after inhalation of sevoflurane can ensure rapid reach of anesthetic depth and the inhibition of cough and spasm. Propofol is a general anesthetic drug with a short duration and no excitatory effects. It can inhibit the appearance of the myotonic phenomenon.

2.5 Sevoflurane for anesthesia

Since children are in the developmental stage, heart rate changes, respiratory depression, body temperature instability, and wakefulness delay are prone to occur during anesthesia. This needs to be carefully considered while selecting an anesthetic. A multicenter study involving comparison of sevoflurane and halothane anesthesia in 428 children showed that sevoflurane groups were induced to be stable without coughing, breath holding, excitement, laryngospasm, bronchial spasm, increased respiratory exudates, vomiting, and other adverse reactions [26]. For adults, Thwaites et al. [27] compared 8% sevoflurane and propofol-induced cystoscopy in adult patients. The results showed that the induction time required for sevoflurane was longer than propofol; but the rate of apnea caused by propofol was significantly higher than that of sevoflurane, and the apnea duration caused by propofol was longer than that of sevoflurane.

2.6 Effect of abnormal blood pressure on sevoflurane

The minimum alveolar concentration with a relatively stable value is used to evaluate the efficacy of inhalation anesthetics. In an animal experiment [28], the minimum alveolar concentration of sevoflurane in the normotensive group and hemorrhagic hypotension group was measured by tail clamping method and the results showed that hemorrhagic hypotension could reduce the minimum alveolar concentration of sevoflurane. However, preventive use of lervoflurane combined with inhaled sevoflurane to maintain the status of anesthesia has a better effect on stabilizing blood pressure, cerebral blood flow, and intracranial pressure in patients with hypertensive intracranial aneurysms undergoing interventional surgery [29]. In addition, in the operation of elderly hypertension patients, sevoflurane anesthesia can maintain the depth of anesthesia, and extubation under deep anesthesia can better inhibit cardiovascular response [30,31]. This suggests that hypertension has little effect on the use of sevoflurane.

2.7 Sevoflurane’s protection mechanism on cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

2.7.1 Reduction of cell damage caused by free radicals

The body’s oxidation/antioxidant system is in dynamic balance under normal conditions. However, in ischemia and hypoxia, the production of free radicals and the oxidative defense system become imbalanced in the body, which is an important pathophysiological basis closely related to cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury [32].

Brain cells are extremely vulnerable to oxygen-free radical damage due to their high metabolic activity, rapid production of active oxygen metabolites, high content of unsaturated fatty acids, and low antioxidant capacity. Free radicals have strong chemical activity, by which they can react with nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and other substances, leading to dysfunction or even death of brain cells [33]. Inflammation results in compounding inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and existing EEA, both of which lead to an increase in NO synthesis. Nitric oxide radicals can strengthen lipid peroxidation, which induces injury in cytomembrane and increase permeability, which can damage the brain tissues directly. In the heart and cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury models, inhaled anesthetics can eliminate nitric oxide and a wide range of free radicals, such as peroxides and NO, both of which exert their biological effects by activating guanylate cyclase that plays a protective role [34]. Sevoflurane postconditioning can significantly inhibit the upregulation of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), induced by cerebral ischemia [35]. Superoxide and oxygen free radicals released during ischemia and reperfusion can induce lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane causing irreversible damage to the cells. Malonic dialdehyde is the main metabolite of this process, and its concentration positively correlated with the extent to which cells are attacked and damaged by free radicals. Superoxide dismutase plays the role of oxygen radical scavenger in the body, and its activity levels represent the body’s ability to scavenge oxygen free radicals. Therefore, inhibiting the excessive release of free radicals and increasing the activity of superoxide dismutase can play a role in brain protection. All aouchiche had found that Sevoflurane post-treatment can increase superoxide dismutase and catalase activity after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury, reduce malonic dialdehyde concentration, and exert neuroprotective effects [36]. Thus, it can provide palliative care for the brain injury. The protection mechanism is related to controlling iNOS and superoxide dismutase. It was showed previously that in the cerebral ischemia model, inhaled anesthetic plays a protective role by eliminating oxygen free radicals, such as NO, peroxide, and ONNO− [34]. Moreover, sevoflurane pretreatment can increase the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and then up-regulate endogenous antioxidation [37]. Post-treatment administration may involve Akt/Nrf2 pathway, significantly increase the expression of phosphorylated protein kinase B (Akt), oxidoreductase 1, Nrf2, thereby reducing the level of oxidative stress and playing a neuroprotective role [38].

2.7.2 Decreased calcium ion content in cells

Neonatal brain injury occurs at about one in every 4,000 live births [39]. However, the mechanism of sevoflurane preconditioning-induced neuroprotection is poorly understood [40]. Calcium ions play an important role in nerve cell activity and signal transduction. Cerebral ischemia leads to energy deficiency, calcium pump dysfunction, mitochondrial damage, and cell membrane depolarization. It can also promote the release of glutamate by the vesicles and activate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, calpain1, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKⅡ), which causes excitotoxicity of neurons, which increases calcium influx and induce apoptosis [41]. Suction sevoflurane has two mechanisms to decrease calcium ion concentration in the cells. One of them is the activated GABAA receptor, which is located in the postsynaptic vesicles and can extend and increase the conduction of the receptor to the chloride ions, open long-time channels, and inhibit synaptic excitability to reduce the internal flow of calcium ions. The other one is activated ATP-sensitive potassium channel, KATP. These channels are inhibited by ATP and activated under energy-depleted conditions. They also can be activated by volatile anesthetics [42]. The opening of these channels produces an outward current. This current can maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential and reduce the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore to inhibit cell injury and death [43,44]. The consequence is reduced calcium ions in the internal flow and calcium ions overload.

2.7.3 Alleviate the toxic effect by EAA

Glutamate accumulating outside the nerve cells is observed in the ischemia and hypoxia, with insufficient blood supply to the brain tissue. Glutamic acid stimulates a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionate-receptor and N-methyl-D-aspartate to excessive excitability and both of them can activate calcium ions and calcium-dependent proteases, causing cytoskeleton destruction, free radical damage, and ionic equilibrium disorder [45]. It seems that the toxicity of EAAs is the originator of all these consequences [45,46]. Previous studies found that sevoflurane can reduce the concentration of glutamic acid by microdialysis [47]. Another experiment demonstrated that the protection mechanism of cerebral ischemia may be related to glutamate transporter by pre-treatment of sevoflurane [48]. The results of the microdialysis study showed that sevoflurane pre-conditioning could reduce the concentration of glutamic acid in cerebral ischemia rats. About 2.5 and 4% of sevoflurane decreased the release of glutamate caused by the depolarization of the synaptic membrane in the neurons of the cerebral frontal cortex of the isolated brain, and the degree of inhibition was 45 and 55%, respectively [47]. Sevoflurane activated protein kinase C kinase by acting directly on the catalytic area and the regulatory region of the protein kinase C. The activation of the latter can enhance the transport function of the glutamic acid transporter in the presynaptic membrane neuron and reduce the concentration of excitatory neurotransmitter glutamic acid in the brain [49].

2.7.4 Relieve inflammation and high blood glucose

Hyperglycemia is not only an important independent risk factor for cerebral ischemia, but also causes poor prognosis in patients with ischemic stroke. The inflammatory correlation factor of hyperglycemia plays an important role in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury, and the damage to endothelial cells directly leads to functional impairment of brain neurons [50]. Cytokines have a dual functions. One is neurotrophy and the other is neurovirulence. However, when the cytokines are superfluous, it mainly results in the neurovirulence function [51]. One of the main mechanisms of ischemia–reperfusion injury is an excessive inflammatory response. TNF-α and IL-1β are the main inflammatory factors in the process of immune and inflammatory reactions, which can induce the expression of intercellular adhesion molecules and aggregation of neutrophils, activating endothelial cells to produce various cytokines. Recent studies have shown that NF-κB is also present in brain vascular endothelial cells, nerve cells, and glial cells, which are specifically activated when the central nervous system is ischemic. Cerebral ischemic–reperfusion injury induces over-expression of pro-inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 through the expression of activated NF-κB, thereby causing inflammatory damage of nerve cells [52]. Studies have shown that pretreatment with sevoflurane effectively inhibits nuclear translocation and activation of NF-κB, thereby significantly reducing the release of inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1 by inhibiting the overexpression of many genes associated with inflammatory responses [53]. Previous experiments have shown that the combination of sevoflurane pre-treatment and post-treatment indicates that sevoflurane can reduce TNF-α in serum [54].

2.7.5 Inhibit cell apoptosis

Apoptosis is an important cause of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Apoptosis is irreversible especially in nerve cells. Therefore, inhibition of apoptosis is critical. The number of apoptotic cells in functional nerve cells at different time points after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in adult rats showed that the number of apoptotic cells in the sevoflurane preconditioning group was significantly lower than that of the control group at 3–7 days of recovery period [55]. Classical apoptotic pathways include intracellular pathways and extracellular pathways. The intracellular pathways involved in apoptosis are mainly divided into caspase-dependent and caspase-independent signaling pathways.

Studies have confirmed that sevoflurane postconditioning can regulate the expression of caspase-3, thus, inhibiting neuronal apoptosis. The extracellular pathway closely related to apoptosis is mainly the Bcl-2 family, of which Bcl-2 is the most important anti-apoptotic factor, while Bax has a pro-apoptotic effect. The balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members affects the induction of apoptosis. When brain damage, such as cerebral ischemia, occurs, the apoptotic protein Bax and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 can migrate from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. This Bax-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway plays an important role in neuronal damage. Research shows that sevoflurane postconditioning can also suppress apoptosis, protect nerve function, and induce the expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, while downregulating the expression of apoptotic protein P53 and Bax [56]. Previous research showed that sevoflurane post-treatment can significantly reduce the expression of TLR4 protein and TRAF6 protein and their mRNAs in brain tissue [57].

2.7.6 Regulate cerebral blood flow

Cerebral blood flow is not kept under control due to continuous pressure changes after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion. Sevoflurane can significantly ameliorate cerebral blood flow by dilating the blood vessels and increasing the cerebral blood flow in a dose-dependent manner. Studies have shown that when 8% sevoflurane is inhaled, the mean velocity of cerebral blood flow increases markedly [58]. Bundgaard et al. showed that 1.5 to 2.5% sevoflurane can increase cerebral blood flow and reduce cerebral vascular resistance in a concentration-dependent manner [59]. Reinsfelt et al. believed that sevoflurane has a certain effect on the regulation and metabolism of cerebral blood flow during cardiopulmonary bypass. However, the use of sevoflurane has not yet reached a consensus on the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Therefore, whether the changes in cerebral blood flow can explain the neuroprotective effects of sevoflurane is not yet clear [60]. Cerebral blood flow autoregulation refers to the process in which cerebral parenchymal blood vessels maintain constant cerebral blood flow and normal brain function through various mechanisms when blood pressure changes [61]. When sevoflurane of approximately one minimum alveolar concentration is inhaled, it can effectively reduce the range of cerebral blood flow autoregulation. But it does not demonstrate the connection between the reduction in cerebral blood flow autoregulation and injury of cerebral ischemia [62]. It has been found that sevoflurane combined anesthesia can control the concentration of amino acids (reduce the toxic injury of amino acids) and maintain the normal hemodynamics of cerebrovascular by regulating cerebral blood flow autoregulation [63].

2.7.7 Repair nervous system

When the central nervous system gets damaged, microglia can eliminate cell debris by phagocytosis and accelerate tissue repair. Xu et al. [64] randomly divided the rats into three groups. There were sham operation group (sham group), focal cerebral ischemia–reperfusion group (control group), and sevoflurane pre-treatment + focal cerebral ischemia–reperfusion group (sevo group). The research showed that sevoflurane preconditioning could cause the migration of microglia to the cerebral ischemia region. It also promoted the activation and phagocytosis of microglia. Activated microglia secreted brain-derived neurotrophic factor, providing a nutritious microenvironment for nerve regeneration and repair. Research found that sevoflurane post-treatment, in a dose-dependent manner, ameliorated the neurological function and abatement of the cerebral infarction region [65]. The study found that the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays an important role in the anti-apoptotic activity of anesthetics and the neuroprotective effects of neuronal survival [66]. Sevoflurane post-treatment upregulates the mRNA and protein levels of heme oxygenase-1 by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thereby alleviating neuronal damage by exerting its neuroprotective effects [67]. Previous studies have shown that pretreatment with sevoflurane can alleviate the extent of damage to astrocytes after cerebral ischemia injury, using transmission electron microscopy. Meanwhile, it also proved that sevoflurane pretreatment can reduce the loss of CX-43 protein as shown by immunofluorescence staining and western-blotting [68]. CX-43 protein, extensively located at glial cells, has been shown to repair neurological injury after ischemia [69].

3 Discussion

Sevoflurane is an anesthetic for general use, whose function is to protect heart and brain tissues. But the use of anesthetic preconditioning is limited, as most ischemia episodes are unpredictable [70]. Previous studies showed that sevoflurane at a concentration as low as 1% was effective to induce neuroprotection, suggesting that a subclinical concentration for anesthesia can induce the postconditioning effect [71]. The use of sevoflurane can reduce free radical formation, alleviate toxic effect by EAA, decrease calcium ion overload in the cell, mitigate the damage to nerve function, and relieve inflammation (Table 1).

Mechanisms and relevant indicators of sevoflurane in the protection of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

| Medical gas | Mechanism of action | Main relevant indicators | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sevoflurane | Reduction of cell damage caused by free radicals | Peroxides, NO, ONNO− | [34] |

| iNOS | [35] | ||

| Superoxide dismutase, catalase, malonic dialdehyde | [36] | ||

| Akt, oxidoreductase 1, Nrf2 | [37,38] | ||

| Decreased calcium ion content in cells | N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, calpain1, Ca2+/CaMKⅡ | [41] | |

| GABAA receptor, KATP | [42] | ||

| Alleviate the toxic effect by excitatory amino acid | a-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionate-receptor, N-methyl-d-aspartate | [45] | |

| Protein kinase C kinase | [49] | ||

| Relieve inflammation and high blood glucose | NF-κB, inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1, etc.) | [53,54] | |

| Inhibit cell apoptosis | Bcl-2, P53, Bax | [56] | |

| TLR4, TRAF6 | [57] | ||

| Regulate cerebral blood flow | Concentration of amino acids | [63] | |

| Repair nervous system | Microglia | [64] | |

| PI3K/Akt, heme oxygenase-1 | [65,66] | ||

| CX-43 protein | [68] |

In summary, cerebral ischemia is a complex disease. The cause of cerebral ischemia injury is not clear yet, but elucidating the mechanism will play a guiding role in preventing brain injury and other fatal conditions, such as producing large amounts of oxygen free radicals and inflammatory factors; thus, causing apoptosis in the nervous system after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion [72]. These mechanisms still need to be clarified in future studies.

Sevoflurane is the third generation of inhalable anesthetics. The mechanism of its neuroprotective effects is not yet clear. The current research is at the exploratory stage. To date, many studies have reported that sevoflurane can downregulate the expression of inflammatory factors, but the specific mechanism of sevoflurane on inflammatory factors is not understood. Whether the protection mechanism of sevoflurane preconditioning and postprocessing is different remains to be studied. Furthermore, whether sevoflurane has different protective mechanisms for individuals of different ages and genders remains to be studied.

-

Funding information: This work was jointly supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81473587, 81774230), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LR16H270001).

-

Author contributions: Bing Chen and Minqiu Lin both searched literatures and wrote the paper. Simiao Chen, Weiyan Chen, Jingmei Song and Yuyan Zhang participated in the discussion and enrichment of the content and contributed to the final paper as well.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Kitano H, Kirsch JR, Hurn PD, Murphy SJ. Inhalational anesthetics as neuroprotectants or chemical preconditioning agents in ischemic brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1108–28.10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600410Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Yang QZ, Dong H, Deng J, Wang Q, Ye RD, Li XY, et al. Sevoflurane preconditioning induces neuroprotection through reactive oxygen species-mediated up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes in rats. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:931–7.10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820bcfa4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wang D, Yang X. Sevoflurane and its metabolism. J North Sichuan Med Coll. 2013;28:409–12.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhong X, Lin R, Li Z, Mao J, Chen L. Effects of Salidroside on cobalt chloride-induced hypoxia damage and mTOR signaling repression in PC12 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:1199–206.10.1248/bpb.b14-00100Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Chen QM, Xiao L, Wang XM, Zuo L, Huang LH, Shan DY. The influence of early rehabilitation treatment for acute cerebrovascular disease to recovery limb function. Kunming Med Univ J. 2015;36:43–5.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Clarkson AN. Anesthetic-mediated protection/preconditioning during cerebral ischemia. Life Sci. 2007;80:1157–75.10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33.10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Beitner-Johnson D, Rust RT, Hsieh T, Millhorn DE. Regulation of CREB by moderate hypoxia in PC12 cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:143–52.10.1007/0-306-46825-5_14Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Boutros A, Wang J, Capuano C. Isoflurane and halothane increase adenosine triphosphate preservation, but do not provide additive recovery of function after ischemia, in preconditioned rat hearts. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:109–17.10.1097/00000542-199701000-00015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C. The science of stroke: mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron. 2010;67:181–98.10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Park H, Jeong EJ, Kim MH, Kim MH, Hwang JW, Min SW, et al. Effects of sevoflurane on neuronal cell damage after severe cerebral ischemia in rats. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61:327–31.10.4097/kjae.2011.61.4.327Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Ye Z, Guo QL, Wang E, Shi M, Pan YD. Sevoflurane preconditioning induced delayed neuroprotection against focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cent South Univ (Med Sci). 2009;34:152–7.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Qin Q, Li R, Zeng QF. Effects of sevoflurane pretreatment on angiotensin Ⅱ receptor and inflammation in hippocampus of rats with focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Guizhou Med Univ. 2019;44:1024–8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Huo M, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Zheng XX, Cao Y, Chen X. Mechanism of sevoflurane pretreatment on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. progress in modern. Biomedicine. 2020;20:2246–51.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Pang HL, Song JJ, Fan JC, Zheng XZ. Protective effect of sevoflurane post-conditioning on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury rats and its effect on toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. J Xinxiang Med Univ. 2020;37:21–5 + 29.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yu F, Tong LJ, Cai DS. Sevoflurane inhibits neuronal apoptosis and expressions of HIF-1 and HSP70 in brain tissues of rats with cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:5082–90.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Miao YF, Yang MQ, Sima LJ, Yan JQ. Effect of sevoflurane anesthesia on learning and memory function in rats with cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Chin J Pract Nerv Dis. 2020;23:2123–29.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Adamczyk S, Robin E, Simerabet M, Kipnis E, Tavernier B, Vallet B, et al. Sevoflurane pre- and post-conditioning protect the brain via the mitochondrial K ATP channel. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:191–200.10.1093/bja/aep365Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Kondo Y, Hirose N, Maeda T, Suzuki T, Yoshino A, Katayama Y. Changes in cerebral blood flow and oxygenation during induction of general anesthesia with sevoflurane versus propofol. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;876:479–84.10.1007/978-1-4939-3023-4_60Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Wu SH, Zhang GQ, Weng CH. Effect of sevoflurane inhalation anesthesia for craniotomy in patients with cerebral protective effect of acute intracranial hemorrhage. J Pract Med. 2017;33:276–8.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Yang XH, Shu YB, Yu DS. Effects of sevoflurane anesthesia on hemodynamics and myocardial injury in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. Chin J Gerontol. 2020;40:3014–7.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Li P, Wang J, Luo LL, Huang W. Progress in the study of seven halothane induced anesthesia. West China Med J. 2017;32:1112–5.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhu B, Huang LF, Li P. Comparison of anesthetic effect and safety between seven halothane and propofol induced anesthesia in pediatric surgery patients. Anti-Infection. Pharmacy. 2018;15:895–7.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Ju RH. Clinical research progress of sevoflurane inhalation induced anesthesia. J China Prescr Drug. 2017;15:27–8.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Chang TC, Cavuoto KM. Anesthesia considerations in pediatric glaucoma management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25:118–21.10.1097/ICU.0000000000000032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Wappler F, Frings DP, Scholz J, Mann V, Koch C, Schulte am Esch J. Inhalational induction of anaesthesia with 8% sevoflurane in children: conditions for endotracheal intubation and side-effects. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:548–54.10.1097/00003643-200307000-00006Search in Google Scholar

[27] Thwaites A, Edmends S, Smith I. Inhalation induction with sevoflurane: a double-blind comparison with propofol. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:356–61.10.1093/bja/78.4.356Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Bi SP, Chen ZJ, Wang G, Zhang H, Zhang ZJ, Wang AG. Influence of duration of anesthesia or hemorrhagic hypotention on MAC of sevoflurane in rabbits. Acad J Chin PLA Med Sch. 2000;21:61–2.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wang F, Gao CJ, Zheng YY. Preventive effects of inhaled lervoflurane combined with inhaled sevoflurane on blood pressure, cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure in patients with intracranial aneurysms complicated with hypertension. Pract J Cancer. 2019;34:1536–8.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chen Y. Effect of propofol and sevoflurane on extubation of hypertensive patients under deep anesthesia. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2018;11:62–3.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Tan ZY. Application effect analysis of two anesthesia methods in elderly patients with hypertension surgery. Chin Foreign Med Res. 2015;12:133–4.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zhao D, Yuan LH, Zhang J, Zhang P, Yu P, Xiao F, et al. Effects of sevoflurane post-conditioning on oxidative stress and inflammatory reaction during rat cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. J Clin Anesthesiol. 2017;33:688–92.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ji W, Xia DG. Research progress of the protective mechanism of sevoflurane on ischemic brain injury. Chin J Clin (Electron Ed). 2015;9:4712–5.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Fang M, Tao YX, He FH, Zhang MJ, Levine Claire F, Mao PZ, et al. Synaptic PDZ domain-mediated protein interactions are disrupted by inhalational anesthetics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36669–75.10.1074/jbc.M303520200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Velly Lionel J, Canas Paula T, Guillet Benjamin A, Labrande Christelle N, Masmejean Frédérique M, Nieoullon André L, et al. Early anesthetic preconditioning in mixed cortical neuronal-glial cell cultures subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation: the role of adenosine triphosphate dependent potassium channels and reactive oxygen species in sevoflurane-induced neuroprotection. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:955–63.10.1213/ane.0b013e318193fee7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Allaouchiche B, Debon R, Goudable J, Chassard D, Duflo F. Oxidative stress status during exposure to propofol, sevoflurane and desflurane. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:981–5.10.1097/00000539-200110000-00036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Cai M, Tong L, Dong BB, Hou WG, Shi LK, Dong HL. Kelch-like Ech-associated protein 1-dependent nuclear factor-e2–related factor 2 activation in relation to antioxidation induced by sevoflurane preconditioning. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:507.10.1097/ALN.0000000000001485Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Li B, Sun J, Lv G, Yu Y, Wang G, Xie K, et al. Sevoflurane postconditioning attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via protein kinase B/nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway activation. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014;38:79–86.10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.08.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985–95.10.1056/NEJMra041996Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Sun YY, Li YH, Liu L, Wang YQ, Xia YY, Zhang LL, et al. Identification of miRNAs involved in the protective effect of sevoflurane preconditioning against hypoxic injury in PC12 cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2015;35:1117–25.10.1007/s10571-015-0205-7Search in Google Scholar

[41] Matsuda T, Arakawa N, Takuma K, Kishida Y, Kawasaki Y, Sakaue M, et al. SEA0400, a novel and selective inhibitor of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, attenuates reperfusion injury in the in vitro and in vivo cerebral ischemic models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:249–56.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jiang MT, Nakae Y, Ljubkovic M, Kwok WM, Stowe DF, Bosnjak ZJ. Isoflurane activates human cardiac mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K+ channels reconstituted in lipid bilayers. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:926–32.10.1213/01.ane.0000278640.81206.92Search in Google Scholar

[43] Kowaltowski AJ, Seetharaman S, Paucek P, Garlid KD. Bioenergetic consequences of opening the ATP-sensitive K(+) channel of heart mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H649–57.10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H649Search in Google Scholar

[44] Gateau-Roesch O, Argaud L, Ovize M. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore and postconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:264–73.10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[45] Gagliardi RJ. Neuroprotection, excitotoxicity and NMDA antagonists. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2000;58:583–8.10.1590/S0004-282X2000000300030Search in Google Scholar

[46] Nishizawa Y. Glutamate release and neuronal damage in ischemia. Life Sci. 2001;69:369–81.10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01142-0Search in Google Scholar

[47] Engelhard K, Werner C, Hoffman WE, Matthes B, Blobner M, Kochs E. The effect of sevoflurane and propofol on cerebral neurotransmitter concentrations during cerebral ischemia in rats. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1155–61.10.1213/01.ANE.0000078576.93190.6FSearch in Google Scholar

[48] Xia P, Wang ZP, Jiang S, Zeng YM. Activation of glutamate transporters during sevoflurane precondition against ischemic brain damage. Chin J Tissue Eng Res. 2007;11:2261–4.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Do SH, Kamatchi GL, Washington JM, Zuo Z. Effects of volatile anesthetics on glutamate transporter, excitatory amino acid transporter type 3: the role of protein kinase C. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1492–7.10.1097/00000542-200206000-00032Search in Google Scholar

[50] Liu X, Zhang JZ. The research development of relative factors of inflammation in the impairment of cerebral ischemia reperfusion. J North Sichuan Med Coll. 2014;29:237–42.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Merrill JE, Benveniste EN. Cytokines in inflammatory brain lesions: helpful and harmful. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:331–8.10.1016/0166-2236(96)10047-3Search in Google Scholar

[52] Stephenson D, Yin T, Smalstig EB, Hsu MA, Panetta J, Little S, et al. Transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B is activated in neurons after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:592–603.10.1097/00004647-200003000-00017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Zhong C, Zhou Y, Liu H. Nuclear factor kappa B and anesthetic preconditioning during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:540–6.10.1097/00000542-200403000-00012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Wu Y, Han XC, Xing QZ, Li Y, Dong X, Zhang YJ, et al. Protective effect of sevoflurane on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in patients undergoing intracranial aneurysm clipping. Chin J Mod Appl Pharm. 2019;36:1678–81.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Codaccioni JL, Velly LJ, Moubarik C, Bruder NJ, Pisano PS, Guillet BA. Sevoflurane preconditioning against focal cerebral ischemia: inhibition of apoptosis in the face of transient improvement of neurological outcome. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1271–8.10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a1fe68Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Wang JK, Yu LN, Zhang FJ, Yang MJ, Yu J, Yan M, et al. Postconditioning with sevoflurane protects against focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Res. 2010;1357:142–51.10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Dan JP, Li DZ, Zhang K, Zhu GH, Wang LS. Effects of seven sevoflurane postcondionting on the expression of TLR4 and TRAF6 in brain tissue of rats after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. J Clin Exp Med. 2018;17:2255–9.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Yan R, Ji FB, Guo SQ, Hu NQ. Effect of high concentration sevoflurane induction on cerebral blood flow velocity in patients undergoing nucleus pulposus extraction. J Clin Anesthesiol. 2011;27:777–8.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Bundgaard H, von Oettingen G, Larsen KM, Landsfeldt U, Jensen KA, Nielsen E, et al. Effects of sevoflurane on intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolism. A dose-response study in patients subjected to craniotomy for cerebral tumours. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:621–7.10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05292.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Reinsfelt B, Westerlind A, Ricksten SE. The effects of sevoflurane on cerebral blood flow autoregulation and flow-metabolism coupling during cardiopulmonary bypass. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:118–23.10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02324.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Lin WR, Gao QC, Li XL. Observation on autoregulation range of cerebral blood flow in mice. Shandong Med J. 2017;57:32–4.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Goettel N, Patet C, Rossi A, Burkhart Christoph S, Czosnyka M, Strebel Stephan P, et al. Monitoring of cerebral blood flow autoregulation in adults undergoing sevoflurane anesthesia: a prospective cohort study of two age groups. J Clin Monit Comput. 2016;30:255–64.10.1007/s10877-015-9754-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Zhang XF, Wang JS, Qu MM, Fei J. Effects of sevoflurane on cerebrovascular autoregulation and amino acid levels in cerebrospinal fluid in children undergoing neurosurgery. Shandong Med J. 2018;58:71–3.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Xu CL, Zhang GH, Ju H, Zhang WC, He YF, Pei J. The effect and mechanism of sevoflurane preconditioning on cerebral endogenous neurogenesis and reconstruction following brain ischemia in rats. Guangdong Med J. 2018;39:1142–7.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Xia M, Dong HL, Xie KL, Xiong LZ. The protective effect of sevoflurane postconditioning on focal cerebral ischemia reperfusioon injury. J Clin Anesthesiol. 2008;5:434–6.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Wang JK, Yu LN, Zhang FJ, Yang MJ, Yu J, Yan M, et al. Postconditioning with sevoflurane protects against focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Res. 2010;1357:142–51.10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.009Search in Google Scholar

[67] Zhao S, Wu J, Zhang L, Ai Y. Post-conditioning with sevoflurane induces heme oxygenase-1 expression via the PI3K/Akt pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:2435–40.10.3892/mmr.2014.2094Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Yu Q, Yu Z, Liang WM. The effect of sevoflurane preconditioning on astrocytic gap junctions against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Chin J Clin Neurosci. 2016;24:254–9.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Takano T, Oberheim N, Cotrina ML, Nedergaard M. Astrocytes and ischemic injury. Stroke. 2009;40:S8–12.10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533166Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Yang Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Fang X, Xu J. Sevoflurane postconditioning against cerebral ischemic neuronal injury is abolished in diet-induced obesity: role of brain mitochondrial KATP channels. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:843–50.10.3892/mmr.2014.1912Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Ren X, Wang Z, Ma H, Zuo Z. Sevoflurane postconditioning provides neuroprotection against brain hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:1401–4.10.1007/s10072-014-1726-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Fang SD, Zhu YS. Recent advances in pathophysiology mechanisms of cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury. Med Recapitulate. 2006;18:1114–6.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Bing Chen et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation