Abstract

Mango stem bark extracts (MSBE) have been used as bioactive ingredients for nutraceutical, cosmeceutical, and pharmaceutical formulations due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects. We performed the MSBE preparative column liquid chromatography, which led to the resolution and identification by GC-MS of 64 volatile compounds: 7 hydrocarbons, 3 alcohols, 1 ether, 3 aldehydes/ketones, 7 phenols, 20 terpenoids (hydrocarbons and oxygenated derivatives), 9 steroids, 4 nitrogen compounds, and 1 sulphur compound. Major components were β-elemene, α-guaiene, aromadendrene, hinesol, 1-octadecene, β-eudesmol, methyl linoleate, juniper camphor, hinesol, 9-methyl (3β,5α)-androstan-3-ol, γ-sitosterol, β-chamigrene, 2,5-dihydroxymethyl-phenetylalcohol, N-phenyl-2-naphtaleneamine, and several phenolic compounds. The analysis of MSBE, Haden variety, by GC-MS is reported for the first time, which gives an approach to understand the possible synergistic effect of volatile compounds on its antioxidant, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects. The identification of relevant bioactive volatile components from MSBE extracts, mainly terpenes from the eudesmane family, will contribute to correlate its chemical composition to previous determined pharmacological effects.

1 Introduction

Mango stem bark extract (MSBE) has been developed as a bioactive ingredient for nutraceutical, cosmeceutical, and pharmaceutical formulations due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects [1]. The MSBE’s major component is a xanthone (mangiferin, 2-β-d-glucopyranosyl-1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyl-9H-xanthen-9-one, hereafter MF), which has been intensively studied as a promising candidate to be developed for neurodegenerative diseases treatment [2], besides its use as antioxidant in food formulations against lifestyle disorders [3]. Our first work about the chemical composition of the MSBE led to the isolation of seven phenolic components: gallic acid and its methyl and propyl esters, MF, (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin, benzoic acid and its propyl ester, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid; four sugars: glucose, galactose, arabinose, and fructose; and 3 polyols: sorbitol, myoinositol, and xylitol [4]. All previous reported components from the MSBE were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography with photodiode detection coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-MS), but no report has been published about its volatile components, which are usually analyzed by high resolution gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The composition of polyphenol-rich extracts from mango by-products (stem bark and branch tree) on two varieties (Haden and Tommy Atkins) has been compared, and we concluded that the Haden variety would be the best choice for a future exploitation of mango by-products for the production of polyphenol-rich extracts [5].

We report in this manuscript the MSBE volatiles’ composition from the Haden variety by GC-MS to contribute to its full chemical characterization. The possible influence of several volatile components on previous described MSBE health effects (antioxidant and anti-inflammatory) and their possible synergistic effects with nonvolatile components are discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Stem bark collection

Stem Bark (SB) from mango, Haden variety, was collected from a farm located in Bani region (Dominican Republic) in the autumn season (2019), according to a Standardized Operational Procedure [6]. Briefly, bark was marked, with not more than a 2 cm depth, as a rectangle (10 × 50 cm approximately), depending on the tree size. The bark was collected without damaging the stem, with specially designed tools. Bark pieces were cleaned manually from dust, and residues, milled with a hammer mill (3–5 mm pieces), and dried at 60°C for 2 h. SB was dried until constant weight, and water content was determined with a humidity balance (Radwag, Poland, PMR-50).

2.2 Mango stem bark extract (MSBE)

SB (200 g) was Soxhlet-extracted with 1.5 L petroleum ether (boiling point: 40–60°C) for 12 h. Solvent was evaporated down to 10 mL with a dry nitrogen flux, and the residue brought into a stoppered vial and kept at 4–8°C until chromatographic analysis (extract A). The remaining SB was Soxhlet-extracted thereafter with 1.5 L chloroform for 2 h. Solvent was evaporated through vacuum rotary evaporation (ROVA-100, MRC Labs, Israel), and the residue dissolved in acetone, filtered through a 0.45 µm filter disc with a syringe, brought into a stoppered vial, and kept at 4–8°C until preparative chromatography.

Commercially available MSBE powder, obtained through a standardized industrial technology [7], was extracted by a simultaneous steam distillation-solvent extraction (SDE) procedure. The sample was suspended in 90 mL of sodium chloride saturated solution and heated at 140°C for 1 h. Condensed vapors were collected with 10 mL of diethyl ether. Cooling temperature in the condenser was fixed at 0°C. The extract was concentrated to 1 mL in a Kuderna-Danish apparatus with a Vigreux column, dried overnight (4–8°C) with anhydrous sodium sulfate, brought into a stoppered vial, and kept at 4–8°C until chromatographic analysis (extract B).

2.3 Preparative chromatography

Extract A was subjected to preparative chromatography using a Spectrum Labs, USA, Model CF-2, fraction collector equipped with a YL-9160 UV detector (Young Lin, Korea), and a silica gel (80–100 mesh) column, 25 × 5 cm i.d., with a solvent gradient of n-hexane:ethyl acetate as follows: 0–30 min (n-hexane), 30–60 min (1:1 hexane–ethyl acetate), and 60–90 min (ethyl acetate) at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min, and eluent detection at 254 nm, to yield extracts C, D, and E, respectively. Fractions were concentrated by vacuum rotary evaporation; the residue dissolved in 5 mL acetone, dried overnight (4–8°C) with anhydrous sodium sulfate, brought into a stoppered vial, and kept at the same temperature until chromatographic analysis.

2.3.1 High resolution gas chromatography mass spectrometry (HR-GC-MS)

HR-GC-MS was performed on a Carlo Erba (Italy), model MEGA 2, coupled to a VG (UK) mass detector, model TRIO 1000 with splitless injection. Chromatographic analyses were performed on a SPB-1 column (Supelco, USA, 30 × 0.32 mm i.d., df = 1 µm) with helium as carrier gas (1 mL/min). Experimental conditions were as follows: injection volume, 1 µL; splitless time, 30 or 60 s; injector temperature, 260–290°C; detector (FID) temperature, 300°C. Oven heating was programmed from 30 to 60°C to 250–300°C at 4–10°C/min according to extract polarity.

The column was connected through a direct inlet interface (280°C) to the quadrupole ionic source (EI+) fixed at 70 eV at a temperature of 230 or 270°C. Mass spectra were recorded from 10 to 600 Da, scan rate 0.8 s, and stored until data processing. Experimental data were processed with Lab-Base™ software (Fisons, UK) and chromatographic peak identification was done for direct comparison with a library search program and/or retention times and spectra from standard compounds when available. Peaks identification by the library search program should have a match value higher than 0.9.

2.4 Chemicals

All reagents and solvents for extraction and preparative chromatography were purchased from JT Baker, USA. Solvents were Pure for Analysis quality. The following standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Missouri, USA): (+)-aromadendrene (97% purity, MW: 204.35, colorless liquid), dodecanal (92% purity, MW: 184.32, colorless liquid), β-eudesmol (98% purity, MW: 222.37, colorless liquid), α-humulene (96% purity, MW: 204.35, colorless liquid), hinesol (98% purity, MW: 194.27, colorless liquid), 3-methyldibenzothiophene (96% purity, MW: 198.29, colorless liquid), 6-methyl-3-heptanol (99% purity, MW: 130.23, colorless liquid), methyl linoleate (>98% purity, MW: 294.47, colorless liquid), (+)-nootkatone (>99% purity, MW: 218.33, colorless liquid), octanal (99% purity, MW: 128.21, colorless liquid), 1-octadecene (95% purity, MW: 252.48, colorless liquid), myristic acid (>99% purity, MW: 228.37, amorphous white solid), palmitic acid (>99% purity, MW: 256.42, amorphous white solid), and heptadecanenitrile (95% purity, MW 251.45, colorless liquid).

The following standards were purchased from Supelco Inc. (USA): β-amyrin (98% purity, MW: 426.72, colorless liquid), trans-(−)-caryophyllene (98% purity, MW: 204.35, colorless liquid), β(−)-elemene (98% purity, MW: 204.35, colorless liquid), n-hexadecane (>99% purity, MW: 226.44, colorless liquid), n-heptadecane (>99% purity, MW: 240.47, colorless liquid), and guaiol (2 mg/mL solution, MW: 222.37, colorless liquid).

The following pure compounds were available in the laboratory (JT Baker, USA) and used as standards for identification: phenol (>99%, MW: 94.11, colorless hygroscopic solid), hexanoic acid (>99%, MW 116.16, colorless liquid), methyl 4-hydroxymethylbenzoate (>99%, MW: 166.17, white amorphous solid), and 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenol (97% purity, MW: 184.19, colorless amorphous solid).

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3 Results

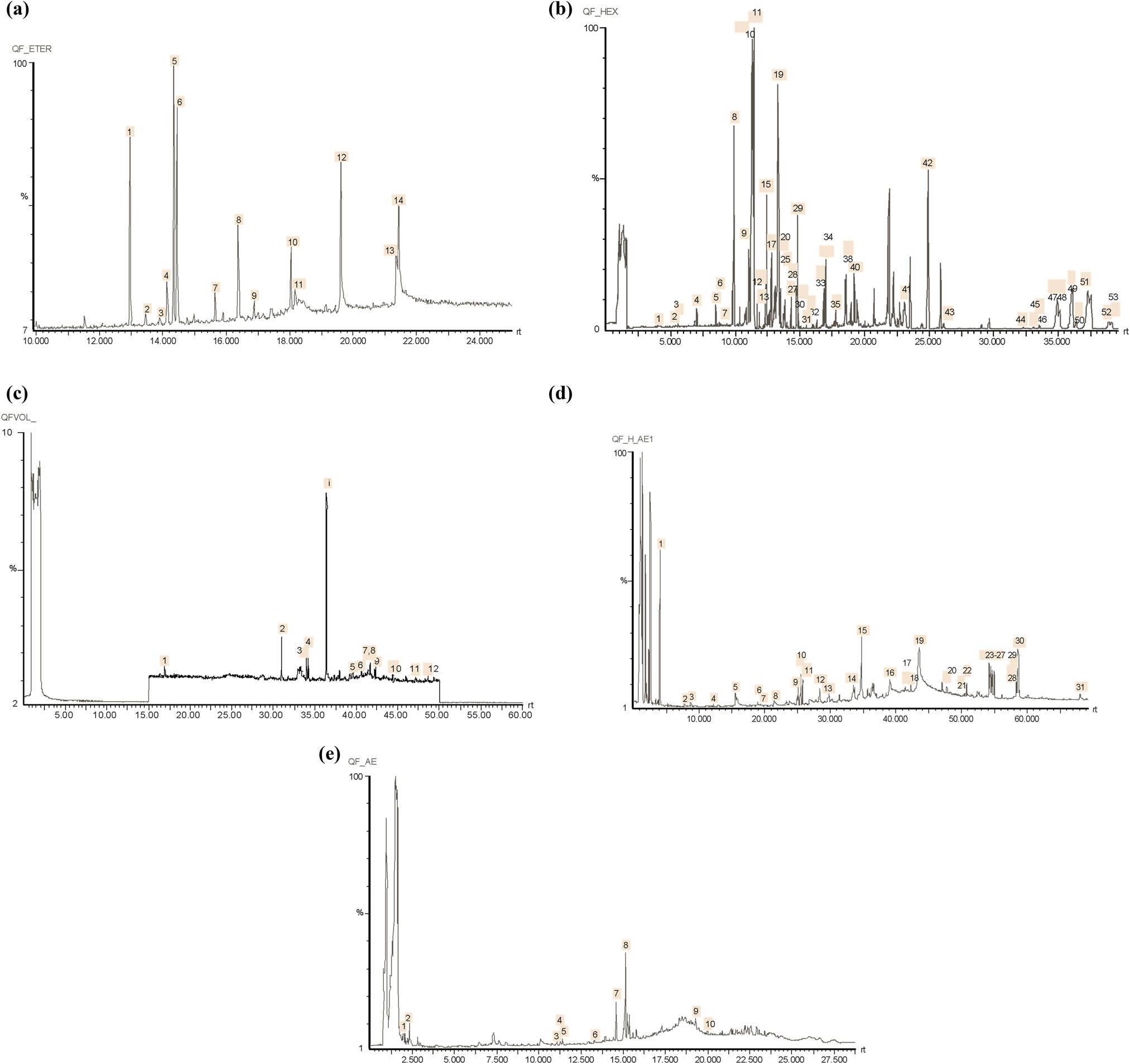

Figure 1 shows the chromatograms from extracts A to E, respectively. Ten compounds from 14 (71%) in extract A, nine compounds from 11 (82%) in extract B, 29 compounds from 53 (55%) in extract C, 20 compounds from 31 (65%) in extract D, and seven compounds from 10 (70%) in extract E could be identified by their mass spectra either by library search software or by comparison with mass spectra of pure standard compounds when available.

Gas chromatograms (FID) of mango stem bark extracts, Haden variety. (a) Fresh mango stem bark extract by Soxhlet extraction. (b) Industrial spray-dried mango stem bark extract (MSBE) by simultaneous steam distillation-solvent extraction. (c) Hexane eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A. (d) Hexane–ethyl acetate (1:1) eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A. (e) Ethyl acetate eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A.

Major components on extract A (Figure 1a) were peaks 1, 5, 6, 8, and 12, identified as β-elemene, β-selinene, 3,7(11)-selinadiene, bulnesol, and palmitic acid, respectively. Peaks 10 and 14 could be identified as a saturated hydrocarbon, with more than 17 carbons, and a gliceride from 9-octadecenoic acid, respectively, but fragmentation patterns were not conclusive. β-elemene (peak 1) and palmitic acid (peak 12) were identified by comparison of their chromatographic behavior and identical mass spectra of pure standards. β-selinene (peak 5), 3,7(11)-selinadiene (peak 6), and bulnesol (peak 8) matched library spectra with values of 0.99, 0.96, and 0.98, respectively, and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds. Other identified minor components in extract A by comparison with authentic standards were trans-(−)-caryophyllene (peak 2), α-humulene (peak 3), n-hexadecane (peak 7), n-heptadecane (peak 9), and palmitic acid (peak 12).

Major components on extract B (SDE extraction, Figure 1b) were peaks 2, 3, 4 and 7, identified as β-elemene, β-selinene, 3,7(11)-selinadiene, and juniper camphor, respectively.

Peak 8 could be identified as a saturated aldehyde with more than 10 carbons, but mass spectrum was not conclusive. β-elemene (peak 2) was identified by comparison of its chromatographic behavior and identical mass spectrum of an authentic standard. β-selinene, 3,7(11)-selinadiene, and juniper camphor matched library spectra with values of 0.99, 0.96, and 0.99, respectively, and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds. Other identified minor components in extract B by comparison with authentic standards were guaiol (peak 5), myristic acid (peak 9), palmitic acid (peak 10), and heptadecanenitrile (peak 11). Peak 6 was identified as α-eudesmol with a matched library spectrum of 0.94 and identical molecular ion as compared to published mass spectrum data of the pure compound.

Major components on extract C (nonpolar fraction, Figure 1c) were peaks 8, 10, 11, 19, and 29, identified as β-elemene, α-guaiene, (+)-aromandendrene, hinesol, and 1-octadecene, respectively. Peak 42 was identified as squalene, a common compound from stationary phase column bleeding. β-elemene (peak 8), (+)-aromandendrene (peak 11), hinesol (peak 19), and 1-octadecene (peak 29) were identified by comparison of their chromatographic behavior and identical mass spectra of pure standards. Peak 10 was identified as α-guaiene with a matched library spectrum of 0.95 and identical molecular ion as compared to published mass spectrum data of the pure compound. Other identified minor components in extract C by comparison with authentic standards were octanal (peak 1), dodecanal (peak 2), (+)-nootkatone (peak 27), 3-methyldibenzothiophene (peak 31), and β-amyrin (peak 49). Another 21 compounds were identified with matched library spectra values between 0.92 and 0.99 and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds (see Table 1).

Identified components in mango stem bark extracts, Haden variety. Extract A: Soxhlet extraction from dried stem bark; extract B: simultaneous steam distillation-solvent extraction of industrial spray-dried stem bark extract (MSBE); extract C: hexane eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A; extract D: hexane–ethyl acetate (1:1) eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A; extract E: ethyl acetate eluate by preparative chromatography from extract A (Match = 1.00 means mass spectra comparison with authentic pure standard)

| No | Compound | M+ | Calc. mass | Match* | Type of extract | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Hydrocarbons (7 compounds) | |||||||||

| 1 | α-Terpinolen[3,8-dimethyl-4-(1-methylidene)-(8S-cis)-2,4,6,7,8,8αhexahydro-5 (1H)-azulenone] | 136 | 136.23 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 2 | Pentamethylethylbenzene | 176 | 176.40 | 0.97 | x | ||||

| 3 | Hexadecane | 225 | 226.44 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 4 | Heptadecane | 240 | 240.47 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 5 | 1-Ethyldecylbenzene | 246 | 246.40 | 0.97 | x | ||||

| 6 | 1-Octadecene | 252 | 252.48 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 7 | 3-Eicosene | 280 | 280.50 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| Alcohols/ethers (4 compounds) | |||||||||

| 8 | 6-Methyl-3-heptanol | 130 | 130.23 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 9 | 1,1-Ethoxypropoxyethane | 132 | 132.20 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| 10 | 2-Butyloctanol | 186 | 186.33 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 11 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzenemethanol | 243 | 243.21 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| Aldehydes/ketones (3 compounds) | |||||||||

| 12 | Octanal | 128 | 128.21 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 13 | Dodecanal | 184 | 184.32 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 14 | 4-Hydroxy-3,5,6-trimethyl-4-(3-oxo-1-butenyl)-2-cyclohexen-1-one | 222 | 222.28 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| Carboxylic/fatty acids/esters (9 compounds) | |||||||||

| 15 | Hexanoic acid | 116 | 116.16 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 16 | 4-Hydroxymethylbenzoate | 151 | 151.14 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 17 | Myristic acid | 228 | 228.37 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 18 | Palmitic acid | 256 | 256.42 | 1.00 | x | x | x | ||

| 19 | Methyl 13-methylpentadecanoate | 270 | 270.50 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 20 | Methyl 2-methylhexadecanoate | 284 | 284.50 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 21 | Methyl 2-oxohexadecanoate | 284 | 284.40 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| 22 | Methyl linoleate | 294 | 294.47 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 23 | Methyl 10-octadecenoate | 296 | 296.50 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| Phenols (7 compounds) | |||||||||

| 24 | Phenol | 94 | 94.11 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 25 | o-Cathecol (1,2-benzenediol) | 110 | 110.11 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| 26 | 1-(2-Hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)ethanone | 150 | 150.07 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 27 | 2,5-Dihydroxy-α-methylphenetyl alcohol | 168 | 168.19 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 28 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenol | 184 | 184.19 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 29 | 3-Octylphenol | 206 | 206.32 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 30 | 3-Pentadecylphenol | 304 | 304.50 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| Terpenes/sesquiterpenes (20 compounds) | |||||||||

| 31 | β-Elemene | 204 | 204.35 | 1.00 | x | x | x | ||

| 32 | α-elemene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 33 | trans-Caryophyllene | 204 | 204.35 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 34 | α-Humulene | 204 | 204.35 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 35 | α-Guaiene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.95 | x | ||||

| 36 | β-Chamigrene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.96 | x | x | |||

| 37 | γ-Selinene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.95 | x | x | |||

| 38 | β-Selinene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.99 | x | x | x | ||

| 39 | α-Selinene | 204 | 204.35 | 0.96 | x | x | |||

| 40 | 3,7(11)-Selinadiene (naphthalene-1,2,3,4,4α,5,6,8α-octahydro-4,8-dimethyl- 2-(1-methylethenyl)-[2R-(2α,4α8β)]) | 204 | 204.35 | 0.96 | x | x | |||

| 41 | (+) Aromadendrene | 204 | 204.35 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 42 | (+) Nootkatone | 218 | 218.33 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 43 | Spathulenol | 220 | 220.35 | 0.93 | x | ||||

| 44 | Ledol | 222 | 222.37 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| 45 | Hinesol | 222 | 222.37 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 46 | Bulnesol | 222 | 222.37 | 0.98 | x | x | |||

| 47 | α-Eudesmol | 222 | 222.37 | 0.94 | x | ||||

| 48 | β-Eudesmol | 222 | 222.37 | 1.00 | x | x | |||

| 49 | Guaiol | 222 | 222.37 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 50 | Juniper camphor | 222 | 222.37 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| Steroids (9 compounds) | |||||||||

| 51 | 9-Methyl-(3β,5α)-androstan-3-ol | 290 | 290.50 | 0.96 | x | ||||

| 52 | 3β-Campesterol | 400 | 400.68 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 53 | 3β,5α-4,4-Dimethylcholesta-8,14-dien-3-ol acetate | 412 | 412.70 | 0.93 | x | ||||

| 54 | Stigmast-4-en-3-one | 412 | 412.70 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| 55 | γ-Sitoesterol | 414 | 414.70 | 0.98 | x | ||||

| 56 | β-Amyrin (olean-12-en-3β-ol) | 426 | 426.72 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 57 | D:C-Friedoolean-3-one (multifluorenone) | 426 | 426.72 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 58 | 24-Methylencycloartanol | 440 | 440.70 | 0.92 | x | ||||

| 59 | 3β-Cycloartane-3,25-diol | 444 | 444.70 | 0.93 | x | ||||

| Nitrogen compounds (4 compounds) | |||||||||

| 60 | N-Phenyl-1-naphthalenamine | 219 | 219.28 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 61 | N-phenyl-2-naphthalenamine | 219 | 219.28 | 0.91 | x | ||||

| 62 | Heptadecanenitrile | 251 | 251.45 | 1.00 | x | ||||

| 63 | 9-Octadecenamide | 281 | 281.50 | 0.99 | x | ||||

| Sulphur compound (1 compound) | |||||||||

| 64 | 3-Methyldibenzothiophene | 198 | 198.29 | 1.00 | x | ||||

Major components on extract D (medium-polarity fraction, Figure 1d) were peaks 10, 15, 19, 23, and 31, identified as β-selinene, β-eudesmol, methyl linoleate, 9-methyl-(3β,5α)-androstan-3-ol, and γ-sitoesterol, respectively. Peaks 24–30 were identified as alkyl substituted phenols, but identification was not possible due to their low concentrations.

β-eudesmol (peak 15) and methyl linoleate (peak 19) were identified by comparison of their chromatographic behavior and identical mass spectra of pure standards. β-selinene (peak 10), 9-methyl-(3β,5α)-androstan-3-ol (peak 23), and γ-sitoesterol (peak 31) matched library spectra with values of 0.99, 0.96, and 0.98, respectively, and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds. Other identified minor components in extract D by comparison with authentic standards were 6-methyl-3-heptanol (peak 1), phenol (peak 2), and palmitic acid (peak 16). Another 11 compounds were identified with matched library spectra values between 0.91 and 0.99 and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds (see Table 1).

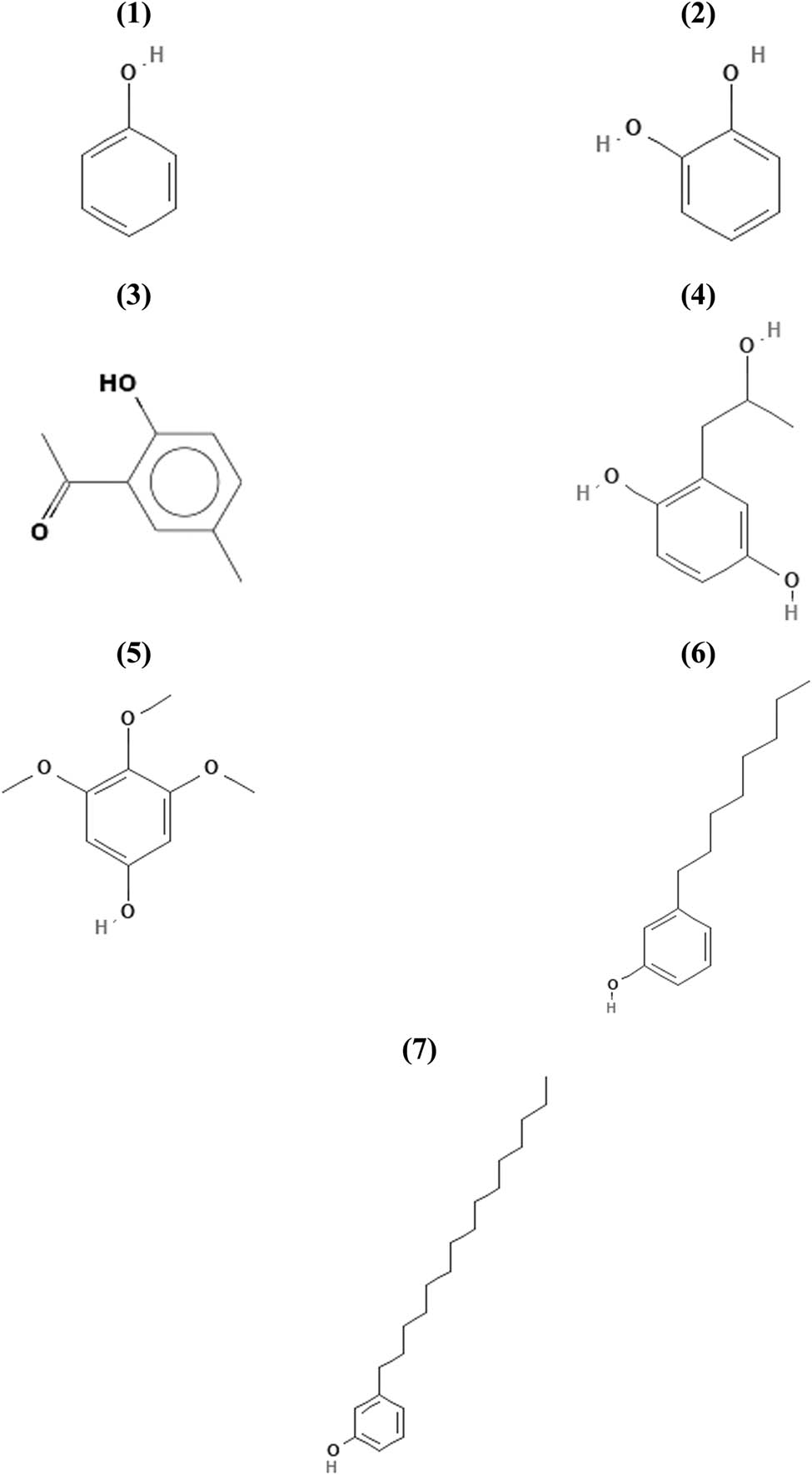

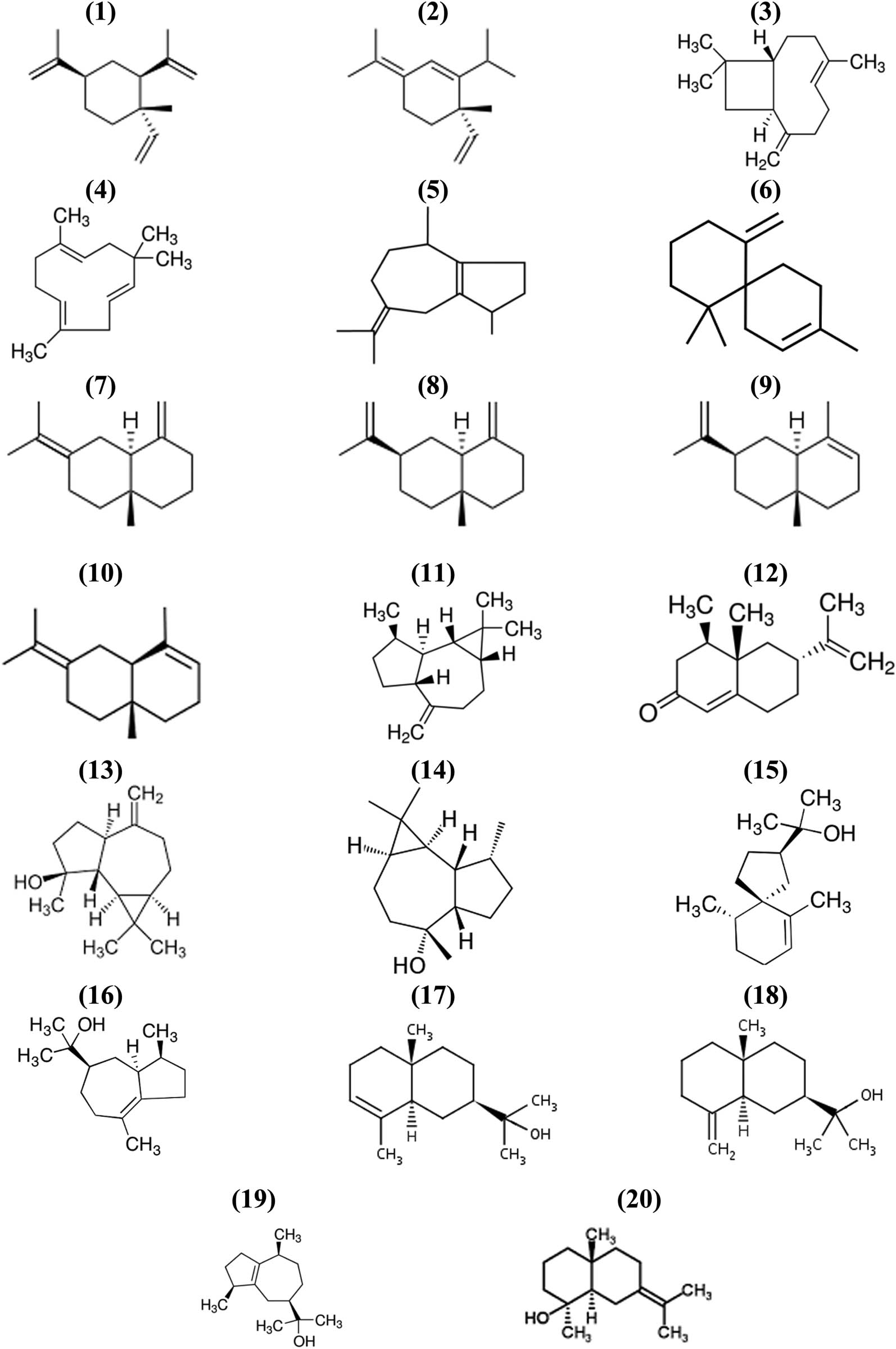

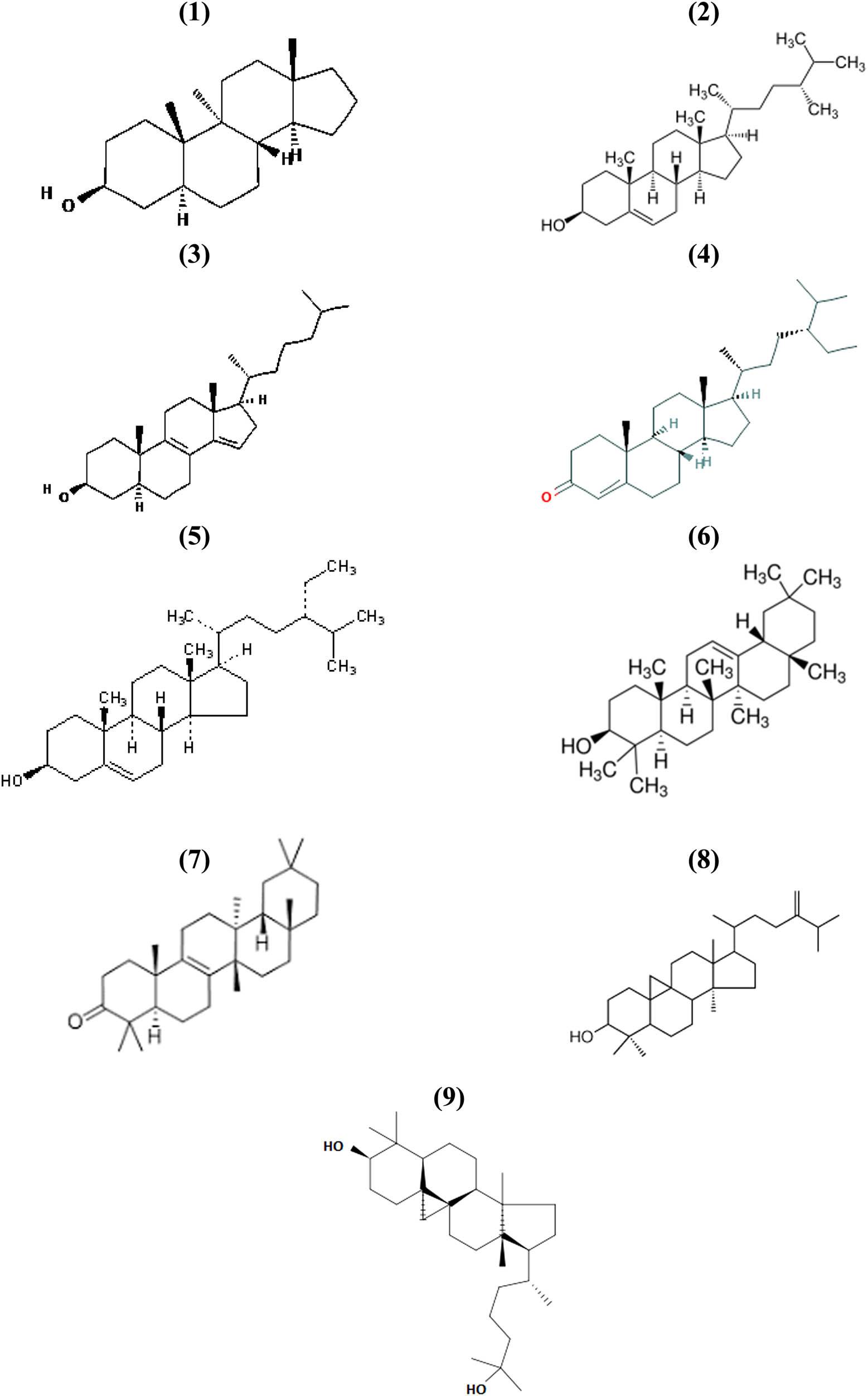

The major component on extract E (polar fraction, Figure 1e) was peak 8, identified as an oxygenated sesquiterpenoid (C15H26O), probably a naphtalenemethanol derivative, but fragmentation pattern was not conclusive. Hexanoic acid (peak 1) and β-eudesmol (peak 6) were identified by comparison of their chromatographic behavior and identical mass spectra of pure standards. β-chamigrene (peak 3), α-selinene (peak 5), 2,5-dihydroxy-α-methylphenetyl alcohol (peak 7), and N-phenyl-2-naphtaleneamine (peak 9) were identified with matched library spectra values of 0.96, 0.96, 0.91, and 0.92, respectively, and had identical molecular ions as compared to published mass spectra data of pure compounds. Summarizing, 64 compounds from 96 detected chromatographic peaks (67%) could be identified either by comparison with pure authentic standards (23 compounds, 24%) or by library mass spectra matches between 0.91 and 0.99 (41 compounds, 43%). Results are shown in Table 1. Relevant chemical structures of phenols (7 compounds), terpenoids (20 compounds), and steroids (9 compounds), regarding their possible biological significance, are shown in Figures 2–4, respectively.

Chemical structures of identified phenols: (1) phenol, (2) 3o-cathecol (1,2-benzenediol), (3) 1-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)ethanone, (4) 2,5-dihydroxy-α-methyl-phenetyl alcohol, (5) 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenol, (6) 3-octylphenol, (7) 3-pentadecyl-phenol.

Chemical structures of identified terpenoid compounds: (1) β-elemene, (2) α-elemene, (3) trans-(−)caryophyllene, (4) α-humulene, (5) α-guaiene, (6) β-chamigrene, (7) γ-selinene, (8) β-selinene, (9) α-selinene, (10) 3,7(11)-selinadiene, (11) (+) aromadendrene, (12) (+) nootkatone, (13) spathulenol, (14) ledol, (15) hinesol, (16) bulnesol, (17) α-eudesmol, (18) β-eudesmol, (19) guaiol, (20) juniper camphor.

Chemical structures of identified steroid compounds: (1) 9-methyl-(3β,5α)-androstane-3-ol, (2) 3β-campesterol, (3) 3β,5α-4,4-dimethylcholesta-8,14-dien-3-ol acetate, (4) stigmast-4-en-3-one, (5) γ-sitoesterol, (6) β-amyrin (olean-12-en-3β-ol), (7) D:C-friedoolean-3-one (multifluorenone), (8) 24-methylencycloartanol, (9) 3β-cycloartane-3,25-diol.

4 Discussion

Volatile compounds in fruits and vegetables usually have been analyzed in terms of their contribution to aroma [8] and flavor [9] properties of fresh or processed products, as part of their contribution to organoleptic properties in terms of product acceptance by the consumer. Fresh or processed fruits, fruit juices, fruit residues after industrial processing (peel and seeds), flowers, pollen, and roots and leaves (fresh or dried) are the most frequently studied parts for the determination of volatiles [10]. Volatile essential oil components from stem, or SB, have been studied in order to determine possible insect attractants or pheromones [11], insect repellents [12], and compounds with certain pharmacological activities [13].

The discoveries of quinine in the Chinchona bark in the XVII century, which subsequently led to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for malaria treatment, and of salicylic acid in the willow SB extract (Salix alba), the precursor of the worldwide known aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) in the XIX century, are examples of nonvolatile blockbuster bioactive components that gave a sound contribution and discovery of new drugs from natural products chemistry. The possible contributions of volatiles from, i.e., willow SB extracts [14], different parts of pomegranate including SB [15], and cinnamon bark extract [16], as bioactive components have been studied. Our interest was to determine the presence of possible bioactive volatile components in the MSBE, which may contribute to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects through a possible synergy mechanism [17]. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and immune-regulatory effects of the MSBE have been tested both in vitro and in vivo [1]. The concentrations at which MSBE exhibited its antioxidant effect were extremely low, no prooxidant effect were observed, and protection to oxidative damage was highly significant [18,19,20,21,22].

Haden mango SB extract components were mainly of nonpolar nature, and compounds found in higher relative amounts were sesquiterpene hydrocarbons as β-elemene, β-selinene, α-guaiene, and aromandendrene, in that order. A report has indicated the high anti-proliferative activity of β-elemene on glioma cells, and it was also an inducer of apoptosis in these cell lines [23]. It has shown to inhibit atherosclerotic lesions by reducing vascular oxidative stress and maintaining the endothelial function by improving plasma nitrite levels [24]. Several studies have shown that β-elemene may be a mediator in cancer prevention through an autoimmune mechanism [25]. Therefore, the possible contribution of β-elemene to the MSBE health effects is considerably high according to these previous reports.

Aromandendrene has been reported as a component of Eucaliptus sp. essential oils, and has shown to have synergistic properties with 1,8-cineole against antibiotic-resistant pathogens [26], but no other biological effect has been reported. β-selinene and α-guaiene have been found in several essential oils [27], and therefore, have no distinctive contributions to MSBE pharmacological effects. β-selinene-rich essential oils (between 37 and 57%) have shown to have strong reducing power as compared to gallic acid and catechin; good ability to chelate iron II; to moderate free radical scavenging activity; and have acceptable anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities [28]. The presence of several terpenes from the eudesmane family, like β-selinene, in the MSBE volatiles composition, highly related to the antioxidant activity, must be considered in further studies in the attempt to correlate this health effect with eudesmane-type terpenes.

Major polar components on MSBE extracts were juniper camphor, hinesol, β-eudesmol, 9-methyl-(3β,5α)-androstan-3-ol, γ-sitosterol, and 2,5-dihydroxy-methylphenetylalcohol. Although these oxygenated compounds were determined in relatively low amounts, as compared to sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, they have higher water solubility, and therefore, higher bioavailability in terms of their possible contribution to MSBE pharmacological effects. These components are commonly found in essential oils from several plants with antioxidant [28] or antimicrobial [29] effects. Hinesol has shown to inhibit H+, K+-ATPase [30], and this result may explain the observed benefits of MSBE on gastric disorders. It also enhanced the inhibitory effect of omeprazole on the hydrogen pump. On the other hand, β-eudesmol stimulates an increase in appetite through Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin (TRPA1), and therefore body weight gain [31]. Again, the presence of eudesmane-type sesquiterpenic alcohols adds a new insight into their possible contribution to the MSBE antioxidant effect.

We conducted the analysis on an industrial MSBE (extract B), which has been used as an antioxidant bioactive ingredient on nutritional supplement formulations (tablets and capsules), and a cosmeceutical cream [7], in order to determine differences on volatiles composition as compared to fresh mango SB (extract A). Both extracts had similar content of β-elemene, β-selinene, and a naphthalene derivative (eudesmane type), but it could not be determined that juniper camphor was present in extract B, which was not present in extract A. Therefore, it might be assumed that these three nonpolar components would contribute to synergize the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of other less volatile components of MSBE bioactive ingredients, like polyphenols and flavonoids, in commercial formulations. Juniper camphor (eudesmane family) is a common available component from plant extracts [32], but its possible contribution to biological effects of essential oils or plant extracts is not clear [33]. It has been found as the main component of Pulicaris sp. essential oils, which have shown high antioxidant activity [34], but reports about biological effects as pure compound are not available.

Studies about mango volatiles have shown that their composition may differ significantly among varieties [35]. The main research focus on mango volatiles has been to identify the major contributing compounds to fruit aroma and flavor [36,37]. The influence of germplasm on volatiles composition of mango fruit cultivated in seven countries has been studied [38]. A study on the volatile composition of the gum-resin exudated by the bark trunk of mango (non-specified variety) showed the presence of selinenes (α- and β-) as the major components, followed by β-caryophyllene, β-elemene, and β-chamigrene [39]. Our findings are consistent with these results in terms of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, but oxygenated components were not found in gum-resin, probably due to the sampling technique (headspace). Nevertheless, reports about composition on the MSBE for any variety, and its possible health effects, are only few.

We reported previously 14 components, mainly nonvolatile polyphenols, sugars, and polyols, form an industrial MSBE [4] by HPLC, MS, and NMR techniques, and eight main minerals: Na, K, Ca, Mg, Mn, Cu, Zn, and Se by ICP-MS [40]. We report now a list of 64 volatile components in the MSBE, identified by GC-MS, which will give a sound basis in the attempts to correlate observed MSBE pharmacological effects to its chemical composition and their possible synergy effects with nonvolatile components.

5 Conclusions

The analysis of MSBE, Haden variety, by GC-MS is reported for the first time, which gives an approach in order to understand the possible synergistic effect of volatile compounds on its antioxidant, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects. The identification of relevant bioactive components in MSBE extracts, mainly terpenes and sesquiterpenes from the eudesmane family, will contribute to correlate their chemical composition to previous reported pharmacological effects.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. John Caccavale for English grammar revision.

-

Funding information: The financial support from the National Fund of Science and Technology (FONDOCYT), Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology (MESCyT), Dominican Republic, and the National Evangelic University (UNEV) through Project 2015-2A3-062 is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Conflict of interest: AJNS and JAA hold a patent about compositions containing mango extracts. LNP declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Authors contributions: All authors have participated in the work and have reviewed and agreed with the content of the article as follows: conceptualization, original draft preparation, supervision, and funding acquisition, AJNS; investigation, data curation, and manuscript reviewing, JAA and LNP.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Nuñez-Selles AJ, Delgado-Hernandez R, Garrido-Garrido G, Garcia-Rivera D, Guevara-Garcia M, Pardo-Andreu GL. The paradox of natural products as pharmaceuticals: experimental evidences of a mango stem bark extract. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(5):351–8. 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Nuñez Selles AJ, Daglia M, Rastrelli L. The potential role of mangiferin in cancer treatment through its immunomodulatory, antiangiogenic, apoptopic and gene regulatory effects. Biofactors. 2016;42(5):475–91. 10.1002/biof.1299.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Imran M, Arshad MS, Butt MS, Kwon JH, Arshad MU, Sultan MT. Mangiferin: a natural miracle bioactive compound against lifestyle related disorders. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:84–100. 10.1186/s12944-017-0449-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Nuñez Selles AJ, Velez Castro H, Agüero Agüero J, Gonzalez Gonzalez J, Naddeo F, De Simone F, et al. Isolation and quantitative analysis of phenolic antioxidants, free sugars, and polyols from mango (Mangifera indica L.) stem bark aqueous decoction used in Cuba as nutritional supplement. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(4):762–6. 10.1021/jf011064b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Nuñez Selles AJ, Espaillat Martinez VM, Nuevas Paz L. HPLC-DAD and HPLC-ESI-MS-DAD analysis of polyphenol-rich extracts from mango agricultural by-products, Tommy Atkins and Haden varieties (Mangifera indica L.) cultivated in Dominican Republic. Int J Pharm Chem. 2020;6:77–88. 10.11648/j.ijpc.20200606.12.Search in Google Scholar

[6] UNEV, Quality Assesment Department. SOP 04.02.03.21.2019. Procedure for the collection of mango stem bark in agricultural sites; 2019. (Spanish).Search in Google Scholar

[7] Nuñez Selles AJ, Paez Betancourt E, Amaro Gonzalez D, Acosta Esquijarosa J, Agüero Agüero J, Capote Hernández R, et al. Composition obtained from Mangifera indica L. Patent CA 2358013A1, 2000/07/06; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[8] El Hadi MAM, Zhang FJ, Wu FF, Zhou CH, Tao J. Advances in fruit aroma volatile research. Molecules. 2013;18(7):8200–29. 10.3390/molecules18078200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Kader AA. Flavor quality of fruits and vegetables. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88(11):1863–8. 10.1002/jsfa.3293.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ayseli MT, Ayseli Yİ. Flavors of the future: health benefits of flavor precursors and volatile compounds in plant foods. Tr Food Sci Technol. 2016;48(2):69–77. 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.005.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Xu H, Turlings TC. Plant volatiles as mate-finding cues for insects. Tr Plant Sci. 2018;23(2):100–11. 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.11.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Kandasamy D, Gershenzon J, Hammerbacher A. Volatile organic compounds emitted by fungal associates of conifer bark beetles and their potential in bark beetle control. J Chem Ecol. 2016;42(9):952–69. 10.1007/s10886-016-0768-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Saab AM, Gambari R, Sacchetti G, Guerrini A, Lampronti I, Tacchini M, et al. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of essential oils from cedrus species. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32(12):1415–27. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1346648.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Li Y, Chen J, Yang Y, Li C, Peng W. Molecular characteristics of volatile components from willow bark. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2020;32(3):1932–6. 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.01.025.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Reidel RVB, Cioni PL, Pistelli L. Volatiles from different plant parts of Punica granatum grown in Tuscany (Italy). Sci Hortic. 2018;231:49–55. 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.12.019.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Li YQ, Kong DX, Wu H. Analysis and evaluation of essential oil components of cinnamon barks using GC–MS and FTIR spectroscopy. Ind Crop Prod. 2013;41:269–78. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.04.056.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Bag A, Chattopadhyay RR. Evaluation of synergistic antibacterial and antioxidant efficacy of essential oils of spices and herbs in combination. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131321.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Martinez G, Delgado R, Perez G, Garrido G, Nuñez-Selles AJ, Leon OS. Evaluation of the in vitro antioxidant activity of Mangifera indica L. extract (Vimang). Phytother Res. 2000;14:424–7. 10.1002/1099–573(200009)14:6<424:AID-PTR643>3.0.CO;2-8.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Martınez G, Giuliani A, Leon OS, Perez G, Nuñez-Selles AJ. Effect of Mangifera indica L. extract (QF808) on protein and hepatic microsome peroxidation. Phytother Res. 2001;15:581–5. 10.1002/ptr.980.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Martınez G, Rodrıguez MA, Giuliani A, Nuñez-Selles AJ, Pons N, Leon OS, et al. Protective effect of Mangifera indica L. extract (Vimang) on the injury associated with hepatic ischaemia reperfusion. Phytother Res. 2003;17:197–201. 10.1002/ptr.921.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Martınez G, Candelario E, Giuliani A, Leon OS, Sam S, Delgado R, et al. Mangifera indica L. extract (QF808) reduces ischaemia-induced neuronal loss and oxidative damage in the gerbil brain. Free Radic Res. 2001;35:465–73. 10.1080/10715760100301481.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sanchez GM, Re L, Giuliani A, Nuñez-Selles AJ, Perez G, Leon OS. Protective effects of Mangifera indica L. extract, mangiferin and selected antioxidants against TPA-induced biomolecules oxidation and peritoneal macrophage activation in mice. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:565–73. 10.1006/phrs.2000.0727.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhou HY, Shen JK, Hou JS, Qiu YM, Luo QZ. Experimental study on apoptosis induced by elemene in glioma cells. Ai Zheng. 2003;22(9):959–63. (Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[24] Liu M, Chen X, Ma J, Hassan W, Wu H, Ling J, et al. β-Elemene attenuates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice via restoring NO levels and alleviating oxidative stress. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95(11):1789–98. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.092.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tong H, Liu Y, Jiang L, Wang J. Multi-targeting by β-elemene and its anticancer properties: a good choice for oncotherapy and radiochemotherapy sensitization. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(4):554–67. 10.1080/01635581.2019.1648694.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Mulyaningsih S, Sporer F, Zimmermann S, Reichling J, Wink M. Synergistic properties of the terpenoids aromadendrene and 1, 8-cineole from the essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus against antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(13):1061–6. 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.06.018.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Raut JS, Karuppayil SM. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind Crop Prod. 2014;62:250–64. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.055.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Chandra M, Prakash O, Kumar R, Bachheti RK, Bhushan B, Kumar M, et al. β-Selinene-rich essential oils from the parts of Callicarpa macrophylla and their antioxidant and pharmacological activities. Medicines. 2017;4(3):52. 10.3390/medicines4030052.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wińska K, Mączka W, Łyczko J, Grabarczyk M, Czubaszek A, Szumny A. Essential oils as antimicrobial agents – myth or real alternative? Molecules. 2019;24(11):2130. 10.3390/molecules24112130.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Satoh K, Nagai, F, Kano, I. Inhibition of H+,K+-ATPase by hinesol, a major component of So-jutsu, by interaction with enzyme in the E1 state. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59(7):881–6. 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00399-8.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ohara K, Fukuda T, Ishida Y, Takahashi C, Ohya R, Katayama M, et al. β-Eudesmol, an oxygenized sesquiterpene, stimulates appetite via TRPA1 and the autonomic nervous system. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–16. 10.1038/s41598-017-16150-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Lingan K. A review on major constituents of various essential oils and its application. Transl Med. 2018;8(201):2161. 10.4172/2161-1025.1000201.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Dhifi W, Bellili S, Jazi S, Bahloul N, Mnif W. Essential oils’ chemical characterization and investigation of some biological activities: a critical review. Medicines. 2016;3(4):25. 10.3390/medicines3040025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Assaeed A, Elshamy A, El Gendy AEN, Dar B, Al-Rowaily S, Abd-ElGawad A. Sesquiterpenes-rich essential oil from above ground parts of Pulicaria somalensis exhibited antioxidant activity and allelopathic effect on weeds. Agronomy. 2020;10(3):399. 10.3390/agronomy10030399.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Pino JA, Mesa J, Muñoz Y, Martí MP, Marbot R. Volatile components from mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(6):2213–23. 10.1021/jf0402633.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Pino JA, Mesa J. Contribution of volatile compounds to mango (Mangifera indica L.) aroma. Flavour Fragr J. 2006;21(2):207–13. 10.1002/ffj.1703.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kulkarni RS, Chidley HG, Pujari KH, Giri AP, Gupta VS. Geographic variation in the flavour volatiles of Alphonso mango. Food Chem. 2012;130(1):58–66. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.053.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Li L, Ma XW, Zhan RL, Wu HX, Yao QS, Xu W, et al. Profiling of volatile fragrant components in a mini-core collection of mango germplasms from seven countries. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0187487. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187487.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Elouma-Ndinga AM, Bonose M, Bleton J, Tchapla A, Ouamba J-M, Chaminade P. Characterization of volatile compounds from the gum-resin of Mangifera indica L. trunk bark using HS-SPME-GC/MS. Pharm Méd Trad Afric. 2015;17(2):1–7.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Nuñez-Selles AJ, Durruthy Rodriguez MD, Rodriguez Balseiro E, Nieto Gonzalez L, Nicolais V, Rastrelli L. Comparison of major and trace element concentrations in 16 varieties of cuban mango stem bark (Mangifera indica L.). J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55(6):2176–81. 10.1021/jf063051+.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Alberto J. Núñez Sellés et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation