In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

-

Nael Abutaha

, Mohammed AL-Zharani

Abstract

Numerous compounds derived from natural sources such as microbes, plants, and insects have proven to be safe, efficacious, and cost-effective therapeutics for human diseases. This study examined the bioactivities of propolis, a structural sealant and antibacterial/antifungal agent produced by honey bees. Chinese propolis was extracted in methanol or hexane. Propolis significantly reduced the numbers of viable cancer cells when applied as a methanol extract (IC50 values in μg/mL for the indicated cell line: MDA-MB-231, 74.12; LoVo, 74.12; HepG2, 77.74; MCF7, 95.10; A549, 114.84) or a hexane extract (MDA-MB-231, 52.11; LoVo, 45.9; HepG2, 52.11; MCF7, 78.01; A549, 67.90). Hexane extract also induced apoptosis of HepG2 cells according to activated caspase-3/7 expression assays (17.6 ± 2.9% at 150 μg/mL and 89.2 ± 1.9% at 300 μg/mL vs 3.4 ± 0.4% in vehicle control), suppressed the growth of Candida albicans and multiple multidrug-resistant and nonresistant Gram-positive bacteria, and inhibited croton oil-induced skin inflammation when applied as topical treatment. GC-MS identified hexadecanoic acid methyl ester as a major constituent (33.6%). Propolis hexane extract has potential anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities.

1 Introduction

Identification of bioactive agents from natural sources, including microbes, insects, and traditional medicinal plants, is a major focus of drug discovery research for infectious diseases and cancer [1,2]. Indeed, there are numerous examples of drugs developed from plants and microbial sources, including the anticancer agents combretastatin, camptothecin, taxanes, geniposide, artesunate, colchicine, salvicine, roscovitine, homoharringtonine, ellipticine, tapsigargin, maytanasin, and bruceantin [3], the antimicrobial polymyxin (colistin) from Paenibacillus amylolyticus [4], and the antimicrobial phytochemicals 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid, ellagic acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid, coumaric acid, and 4-methoxycinnamic acid [5]. Several anti-inflammatory compounds were also first isolated from plants, such as resveratrol, curcumin, boswellic acid, baicalein, betulinic acid, oleanolic acid, and ursolic acid [6].

Acquired drug resistance is a major factor limiting the long-term efficacies of both cancer and microbial infection treatments. Further, some of these drug resistance mechanisms are similar [7]. One strategy for overcoming drug resistance is polypharmacy using drugs with distinct mechanisms of action, such as polychemotherapy for cancer. Many raw natural products and extracts contain large numbers of chemical compounds with distinct or shared bioactivities that act synergistically. These compounds may thus help in overcoming resistance, thereby increasing the efficacy of current cancer polychemotherapy treatments and reducing the likelihood of recurrence and secondary malignancies [8].

Propolis is a resin-like product collected by worker bees (Apis mellifera L.) from different plants to protect the hive, seal cracks, maintain internal temperature and humidity, protect against microbial infections, and prevent decomposition of intruder carcasses [9,10]. The major constituents include pollen (5%), oils (10%), wax (30%), and resins and vegetable balsam (50%). In addition, 300 compounds with potential bioactivity have been reported in propolis, including esters, phenolic acids, and flavonoids. While bioactivity varies with geographical origin and time of collection, many reports have documented antibacterial, antifungal, antitumoral, antiprotozoal, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antioxidant, antiviral, wound healing, and anticancer activities [9,11,12,13,14].

The goal of this investigation was to evaluate the chemical composition and anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties of propolis hexane and methanol extracts from Chinese propolis, including the first test of anti-inflammatory potential using the croton oil-induced inflammation in mice ear edema model.

2 Experimental

2.1 Solvent extraction

Propolis (30 g) was extracted twice in methanol (300 mL) (Fisher Scientific, UK) in a shaking incubator at 150 rpm for 24 h at 30°C and the two extracts were pooled together. The suspension was filtered using Whatman® Grade 1 filter paper and evaporated using rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Germany). The evaporated suspension was re-extracted twice in 250 mL of hexane (Fisher Scientific, UK) in a shaking incubator similar to methanol. The remaining residue (solid) was re-extracted twice in 250 mL of ethyl acetate (Fisher Scientific, UK) in a shaking incubator and processed similar to methanol extract. The resulting methanol, hexane, and ethyl acetate extracts were evaporated, weighed, and dissolved in methanol at a final concentration of 20 mg/mL and stored at −20°C.

2.2 Cancer cell lines

Breast cancer lines MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, the liver cancer line HepG2, the colon cancer line LoVo, and the lung cancer line A549 were obtained from DSMZ, Germany, and grown in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, UFC Biotech, Saudi Arabia, Riyadh). The cell lines were grown at 37°C using a humidified incubator and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell were incubated under the same conditions during drug treatments unless otherwise specified.

2.3 Viable cell number assay

Number of viable cell during treatment was measured as described previously [15] using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Invitrogen). Increasing concentrations of the extract were prepared from a stock solution (10.00 mg/mL) by diluting in culture medium. The final vehicle (methanol) concentration did not exceed 0.1%. Cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were grown in 24-well plates for 24 h, and then incubated with different doses of propolis (20, 50, 100, 140, and 200 µg/mL). The extract concentration needed to inhibit viable cell number by 50% (IC50) was interpolated from the dose‒response curve plotted using Origin 8 software (Northampton, MA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (each with independent triplicate biological repeats).

2.4 Cell morphology and Hoechst 33342 staining

HepG2 cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were grown in 24-well plates, incubated for 24 h, and imaged under phase-contrast microscopy to describe baseline morphology. Cells were then treated with 150 μg/mL extract for 48 h, stained (Hoechst 33342), and then imaged under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS, Carlsbad, USA) according to the method described previously [15].

2.5 Annexin-V, and dead cell assay

HepG2 cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were grown in 6-well plates, incubated until they reach 80% confluence, then treated with 150 μg/mL extract, 300 μg/mL extract, or 0.01% methanol vehicle (control) for 24 h. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s guide. Cells were centrifuged (3,000 rpm, 5 min), washed with PBS, resuspended in DMEM medium 1% bovine serum albumin, and mixed with Annexin V and Dead Cell reagent. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 25°C in the dark and results were analyzed using the Muse™ Cell Analyzer (Millipore, USA).

2.6 Caspase-3/7 activity

HepG2 cells treated as described for cell apoptosis induction were also examined for caspase activity using the Muse® Caspase3/7 Kit following the user’s guide. Briefly, treated HepG2 cells (1 × 105/well) were trypsinized, washed (phosphate-buffered saline), and collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min and further processed by flow cytometry as described [15] using the Muse™ Cell Analyzer.

2.7 Induction of dermatitis in mouse ear skin

Adult albino mice (25–30 g) were housed at four animals per group/cage under standard conditions with free access to water and food. Mice were first anesthetized by injection of ketamin HCl (150 mg/kg, i.p.). After 5 min, inflammation was induced by applying croton oil to the inner surface of the ear (0.4 mg/ear). The right ear was left untreated as a negative control. Twenty-four hours later, a 50 µL solution containing 500 µg hexane extract in acetone or AVOCOM (0.1% Ointment as a positive control) was applied to the croton oil-treated ear using cotton swaps. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were killed by pentobarbital (200 mg/kg, i.p.) and the ears harvested. Ear samples were cut in 6 mm diameter sections, fixed in 10% formalin, and processed as previously described [16]. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and examined under light microscopy.

2.8 Antibacterial activity

A total of eight multidrug-resistant and nonresistant microbial species (Table 1) were examined for propolis sensitivity using agar well diffusion assays as described previously [15]. Muller Hinton agar was poured into Petri plates and allowed to solidify with sterile cork borers to make 6 mm wells. A 100 µL volume of microbial suspension adjusted to OD = 0.01 in growth medium was swabbed over the growth medium surface and 10 mg/mL of the hexane extract solution in growth medium or methanol (negative control) was carefully pipetted into the wells and left to diffuse for 30 min at 25°C. Plates were then kept for 24 h at 37°C. The zones of growth inhibition were recorded in millimeters. All concentrations and microbial strains were tested in triplicate.

Suppression of microbial growth by hexane and methanol propolis extracts as measured by zone of inhibition diameter

| Microorganism | Origin | R type | Bacterial growth inhibition zones mm ± std | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Hexane | Ethyl acetae | |||

| Candida albicans | ATCC-90028 | — | 12 ± 0.7 | 12 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| MRSA* | ATCC33591 | Met | 13 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| S. aureus | Clinical | Ery | 12 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| S. epidermidis | Clinical | Sensitive | 13 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| E. coli | Clinical | Sensitive | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| E. coli | Clinical | fix, amp, amx, cxm, | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| A. baumannii | Clinical | clav, amp, amx, cef, cxm, fix, amox/K | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 |

| A. baumannii | Clinical | Sensitive | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 00 |

*MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Antimicrobial agents: amp, ampicillin; met, amox/K, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; methicillin; ery, erythromycin; cxm, cefuroxime; amx, amoxicillin; fix, cefixime; clav, clavulanic acid; cef, ceftriaxone.

2.9 GC-MS analysis

GC-MS (PerkinElmer Clarus 600, Waltham, MA, USA) fingerprinting was employed to assess the complexity of hexane extract as previously described [15]. The mass spectra were compared to data from the National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST, Gaithersburg, USA) and WILEY Spectral libraries for species identification.

-

Ethical approval: All procedures were performed according to the Animal Ethics Committee, Princess 265 Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, KSA.

3 Results

The yield of propolis extract was calculated as weight/weight percent yield of 30 g of propolis (Figure 1). The yields of methanol, hexane, and ethyl acetate extracts were 30, 6.3, and 21.6%, respectively.

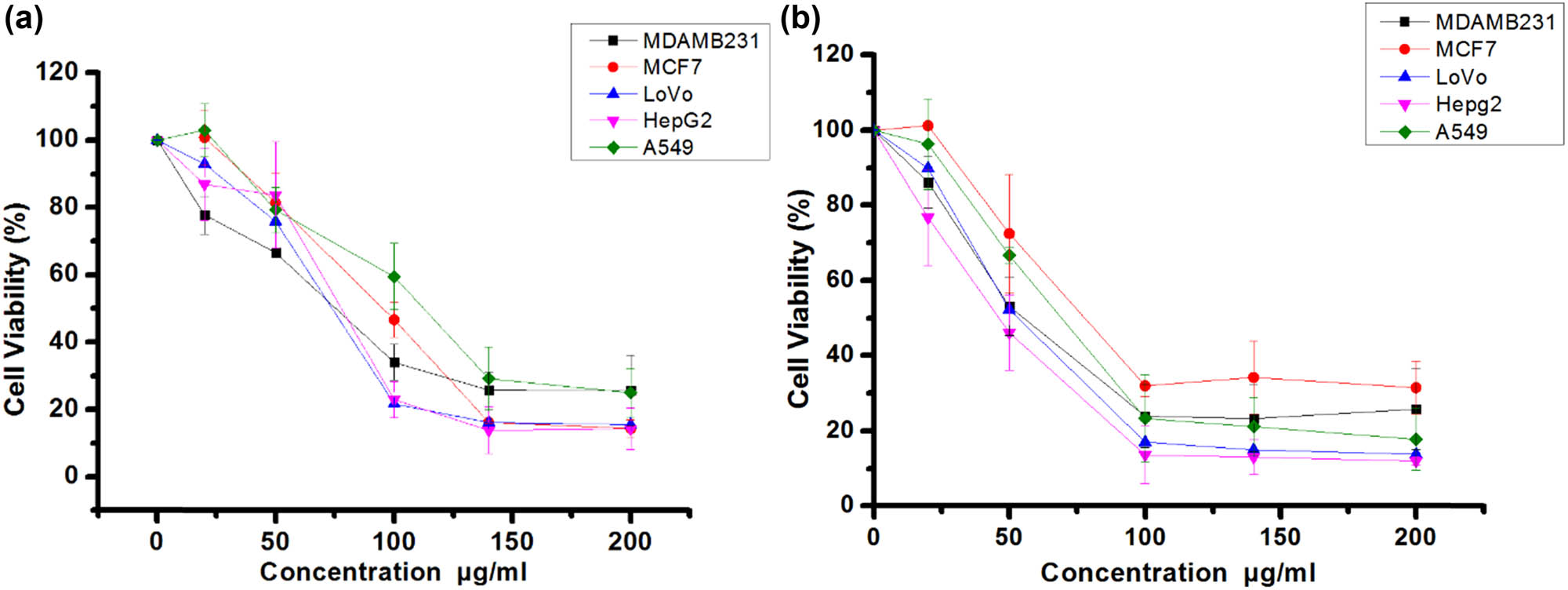

Suppression of viable cancer cell number by propolis methanol extract (a) and hexane extract (b) against MCF7, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, LoVo, and A549 cancer cell lines.

3.1 Cell culture

To evaluate the antiproliferative and/or cytotoxic effects of methanol and hexane extracts of propolis on cancer cells, LoVo, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, MCF7, and A549 cell lines were incubated with increasing extract concentrations and viable cell numbers estimated by MTT assay (Figure 1a and b). These assays yielded IC50 values (in µg/mL) of 74.12 (MDA-MB-231), 77.74 (LoVo), 74.12 (HepG2), 95.10 (MCF7), and 114.84 (A549) for the methanol extract (Figure 1a) and 53.41 (MDA-MB-231), 52.11 (LoVo), 45.9 (HepG2), 78.01 (MCF7), and 67.90 (A549) for the hexane extract. Due to enhanced antiproliferative or cytotoxic efficacy, subsequent experiments were conducted using hexane extract on HepG2 cells.

3.2 Morphological changes to HepG2 cells

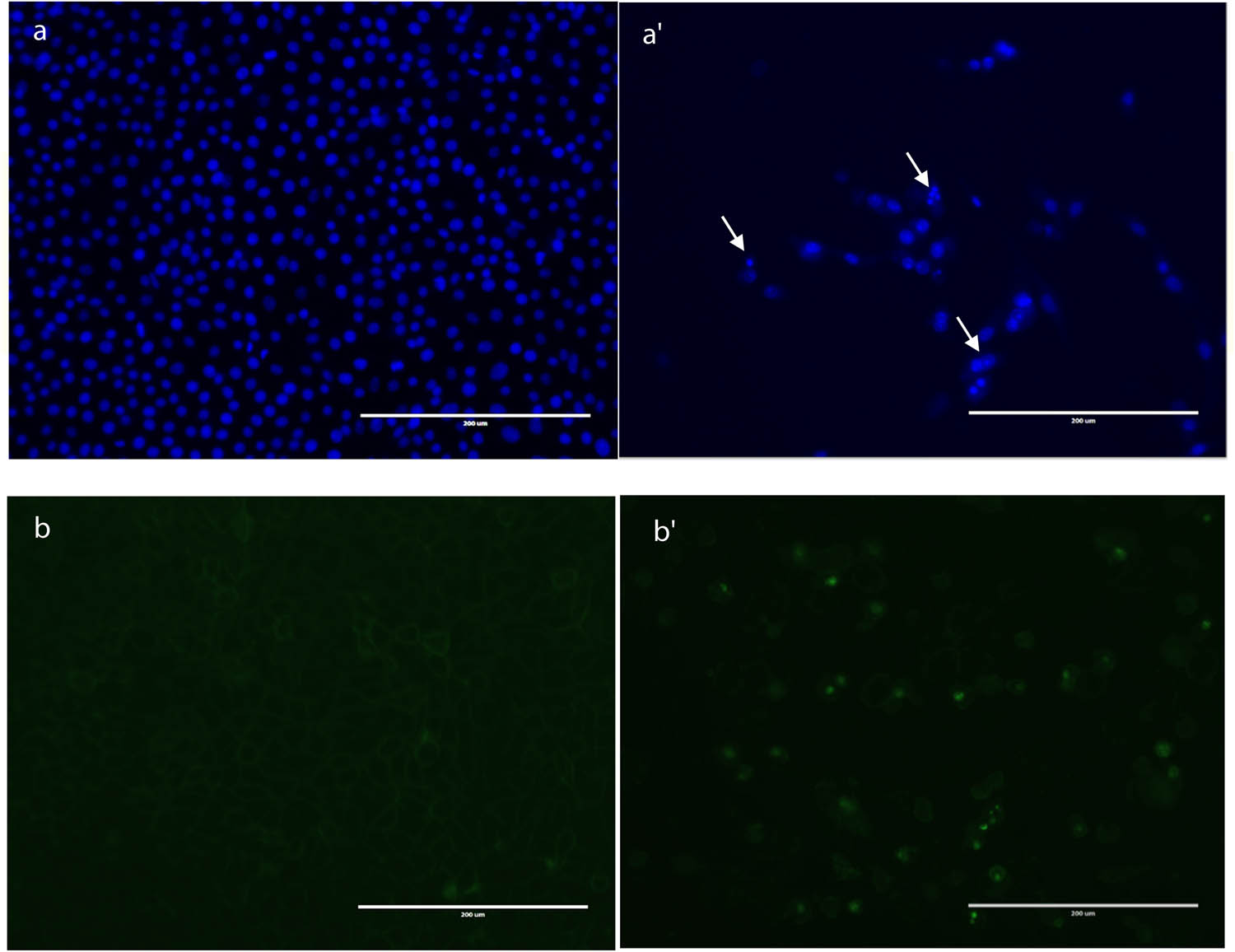

Vehicle-treated HepG2 cells were healthy, spindle-shaped, and attached to the substrate. The cytoplasm was clear and the cell body smooth with cell filopodia approaching neighboring cells. Following treatment with the propolis hexane fraction, cells detached from the substrate and shrank, suggesting apoptosis. Indeed, Hoechst 33342 staining revealed nuclear condensation and fragmentation consistent with apoptosis (arrows in Figure 2).

Induction of apoptosis in HepG2 cells by treatment with hexane propolis extract for 48 h. (a) Apoptosis as assessed by nuclear staining. Cells treated with 0.1% methanol vehicle displayed even nuclear staining (a). HepG2 cells showing condensation of DNA (a′). The white arrows show apoptotic cells. (b) control cells, (b′) treated cells.

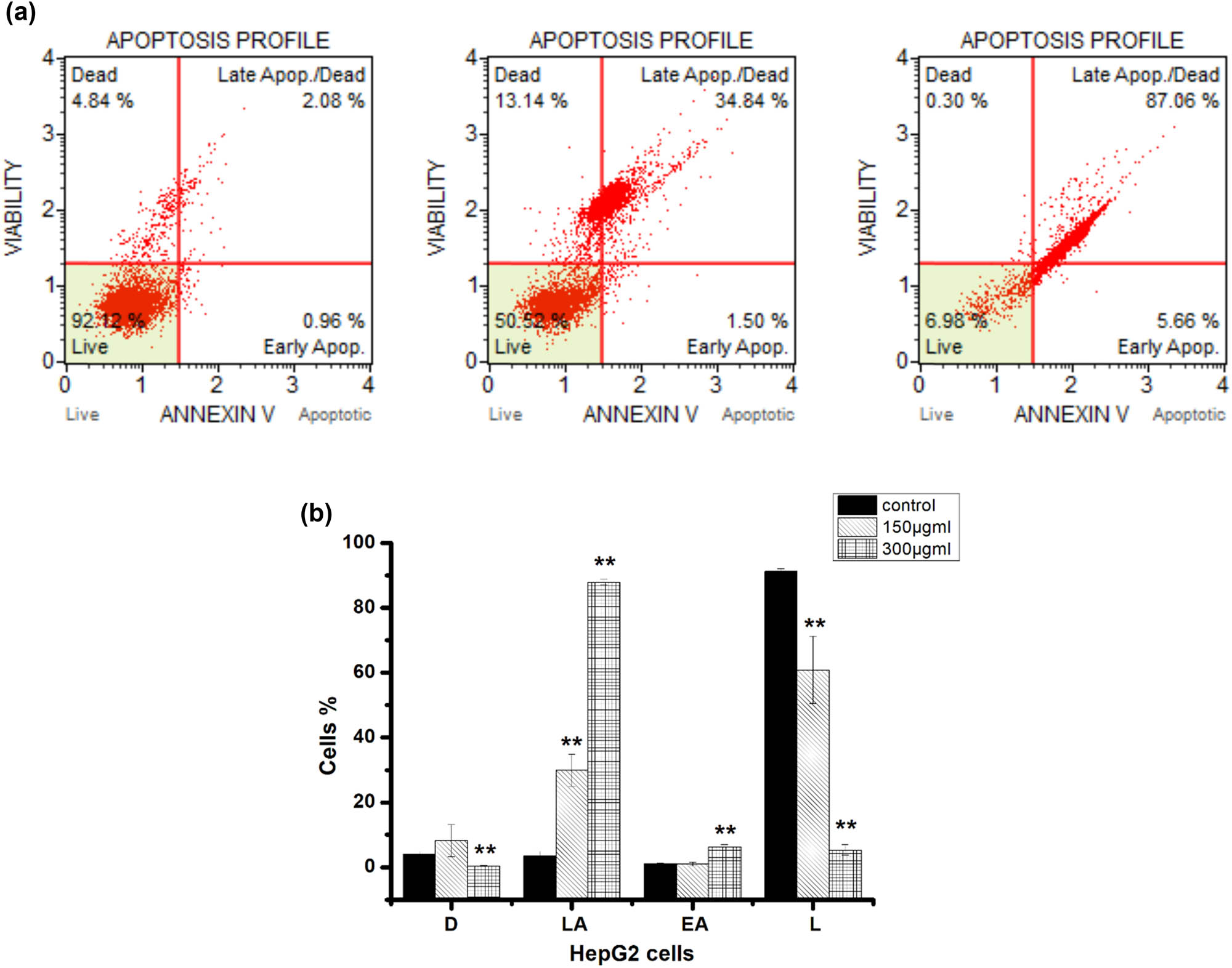

3.3 Annexin-V and dead cell assay

To examine the proapoptotic potential of hexane extract, HepG2 cells were incubated with 150 and 300 μg/mL for 48 h, and apoptotic cells were identified by Annexin V staining and a Dead Cell Muse kit. Result revealed substantial dose-dependent apoptosis, with only 60.8 ± 10.3% of cells remaining after 150 µg/mL incubation and 5.3 ± 1.64% remaining after 300 µg/mL hexane extract treatment for 48 h, proportions significantly lower than following vehicle treatment (91.2 ± 0.8%). While there was little difference in the proportion of early apoptotic cells among treatment groups (control: 1.1 ± 0.17%; 150 µg/mL: 0.97 ± 0.5%; 300 µg/mL: 6.3 ± 0.65%), there were substantial differences in the proportions of late apoptotic cells (control: 3.4 ± 1.38%; 150 µg/mL: 29.9 ± 4.8%; 300 µg/mL: 87.9 ± 0.85%). These results suggest that the hexane extract of propolis suppressed cancer cell number (Figure 3) by inducting apoptosis.

Hexane propolis extract induced HepG2 cell apoptosis at 150 and 300 µg/mL. (a) In each panel, the lower left quadrant designates live cells (dead cell marker (–) and annexin v (–)), lower-right quadrant designates early apoptosis (dead cell marker (–) and annexin v (+)), upper right quadrant designates late apoptosis (dead cell marker (+) and annexin v (+)), and upper left quadrant designates necrotic cells (dead cell marker (+) and annexin v (–)). (b) Proportions of dead cells (D), live cells (L), early apoptotic cell (EA), and late apoptotic cell (LA). Data presented as the mean ± SD, obtained from three independent replications. Significancy between the treated and control cells is reported at the (**) p < 0.05.

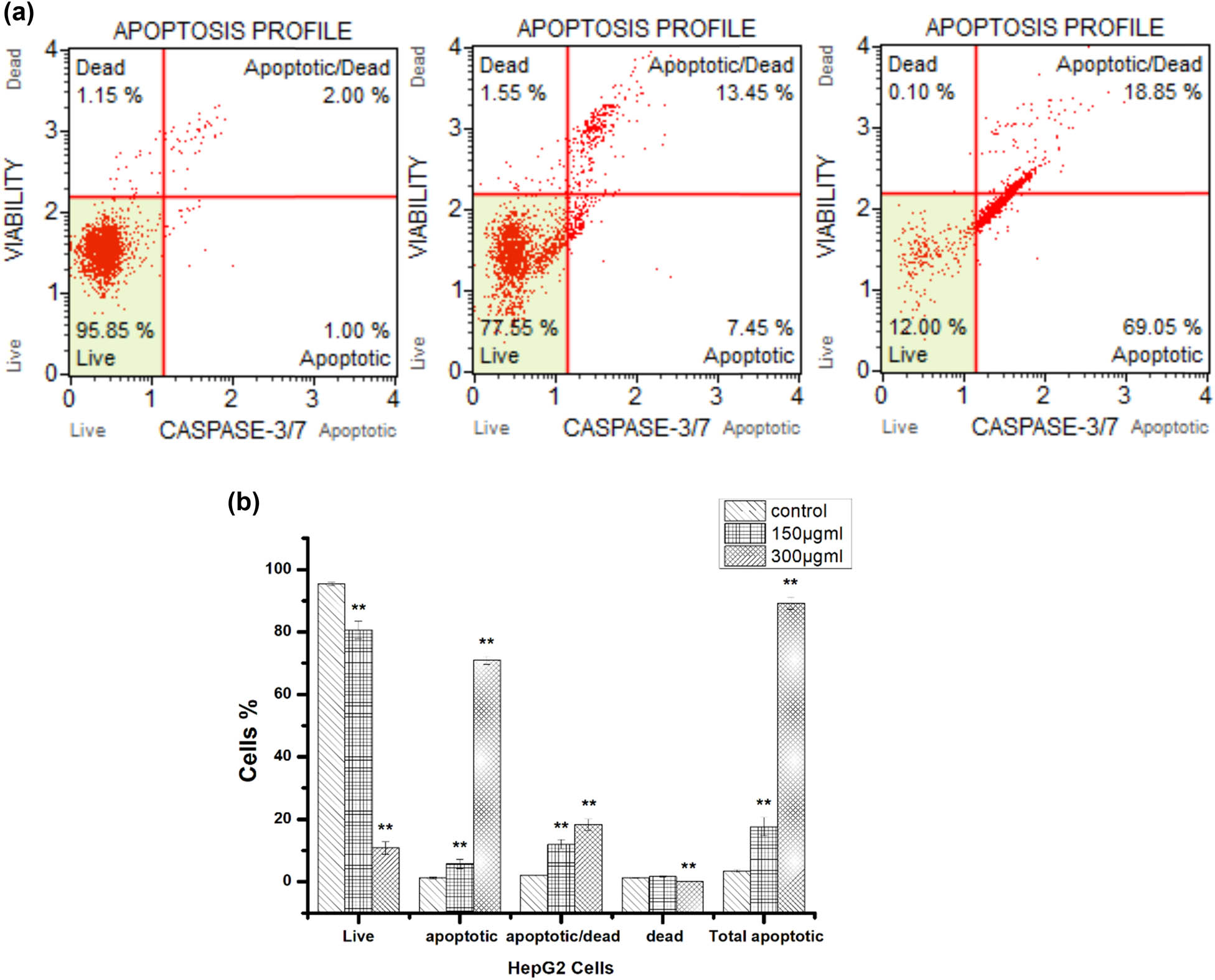

To further verify the proapoptotic effects of hexane propolis extract on HepG2 cells, caspase-3/7 detection assays were conducted in which apoptotic cells emit a bright fluorescence from the nucleus. Again consistent with proapoptotic efficacy, 150 µg/mL extract induced markedly brighter fluorescence emission than vehicle. Further, in accord with Annexin V and Muse assays, the increase in caspase-3/7 activity was dose-dependent (control: 3.4 ± 0.4%; 150 μg/mL: 17.6 ± 2.9%; 300 μg/mL: 89.2 ± 1.9%) (Figure 4).

Hexane extract induced caspase activation in HepG2 cells as revealed by Muse® Caspase 3/7 Kit staining. (a) In each panel, the lower left quadrant designates cells negative for dead cell marker and caspase 3/7, lower-right quadrant cells negative for dead cell marker and positive for caspase 3/7, upper right quadrant cells positive for dead cell marker and caspase 3/7, and upper left quadrant cells positive for dead cell marker and negative for caspase 3/7. (b) Proportions of live, apoptotic, apoptotic/dead, and total apoptotic cells. **p < 0.05.

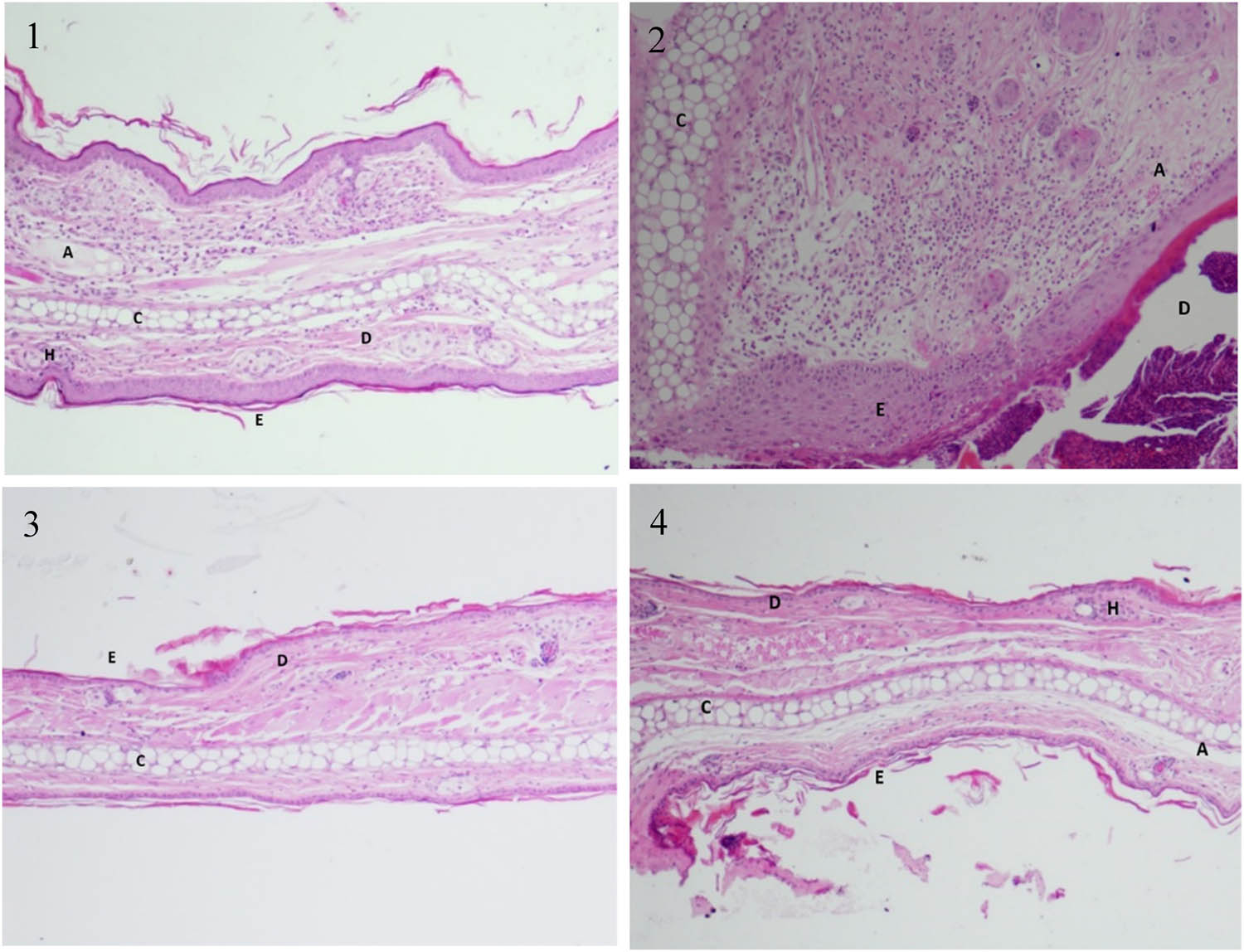

3.4 Croton-induced mouse ear inflammation

The epidermal layer, dermal layer, and cartilage of the untreated (right) ear exhibited normal histological features with no cell infiltration, while the croton oil-treated (left) ear revealed extensive infiltration of neutrophil in the dermal layer (Figure 5(2)). Treatment with hexane extract (100 mg/kg) after croton oil reduced neutrophil infiltration (Figure 5(3)) and maintained relatively normal histological features similar to those observed following AVOCAM treatment as a positive control (Figure 5(4)).

Hexane propolis extract reduced the histopathological alterations associated with ear inflammation/edema induced by croton oil. (1) Normal histological structures of the epidermal layer, dermal layer, and cartilage from an untreated ear. Note the absence of neutrophil infiltration. (2) Tissue treated with croton oil is showing infiltration of neutrophil in the dermis. (3) Tissue of ear treated with hexane propolis extract following croton oil showing virtually undamaged dermis and cartilage with little infiltration of cells. (4) Ear tissue treated with hexane propolis extract showing less of cells in the dermis compared to the croton oil-treated group. H, hair follicle; E, epidermis; D, dermis; C, cartilage; A, adipose tissue.

3.5 Antimicrobial activity

As shown in Table 1, C. albicans was highly susceptible to hexane and methanol extracts as indicated by inhibition zone diameter (12 ± 0.6 mm). However, ethyl acetate extract was inactive at the concentrations tested. Other species demonstrated similar zones of inhibition (12‒13 mm) in response to 10 mg/mL of either extract. In contrast, E. coli and, A. baumannii were resistant to both extracts at all concentrations tested.

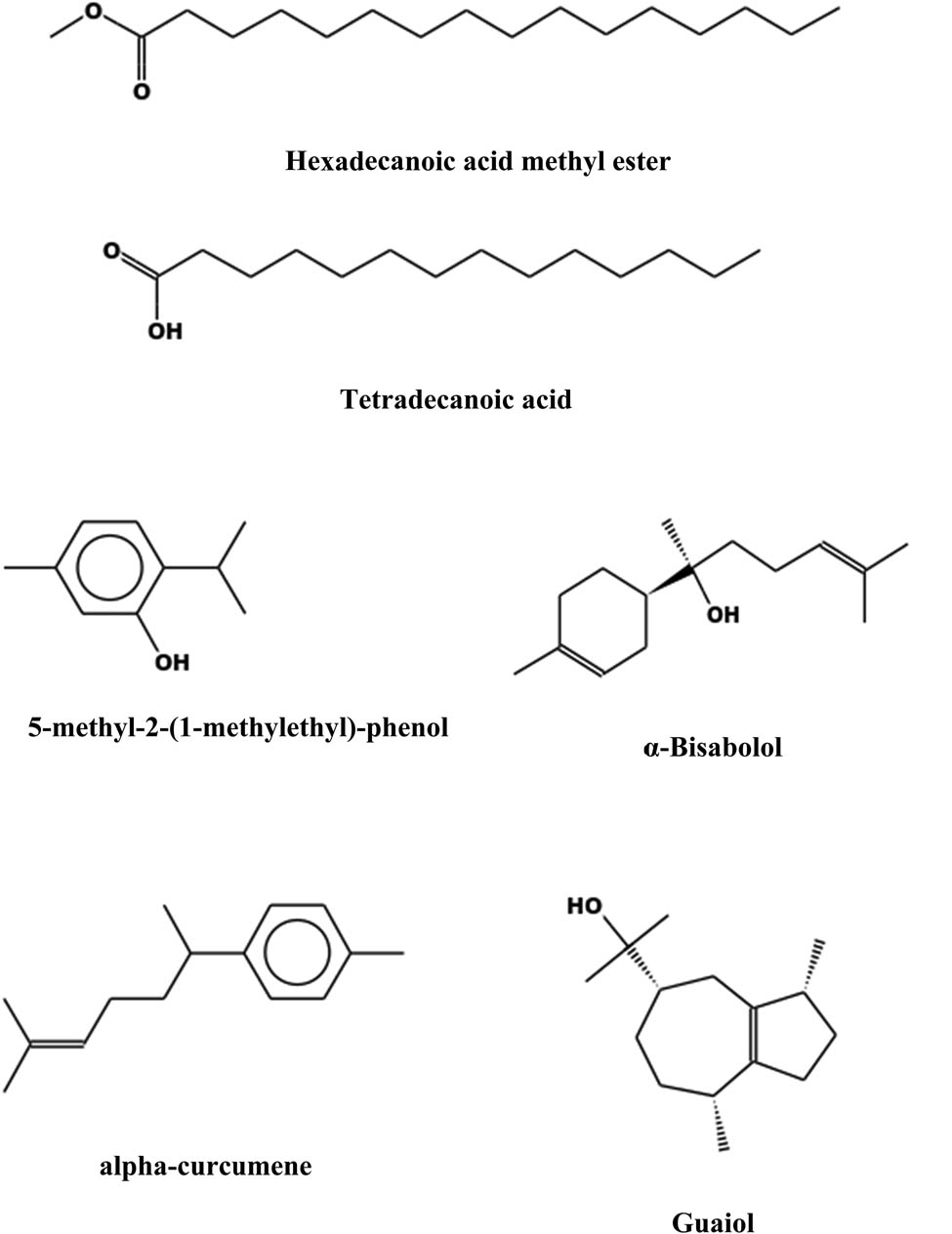

3.6 GC-MS analysis

GC-MS analysis and comparison with NIST and WILEY Spectral libraries revealed the presence of 18 phytochemical compounds in hexane extract (Table 2 and Figure 6). The six largest peaks were hexadecanoic acid methylester (33.6%), octadecanoic acid methylester (11.7%), alpha-eudesmo (7.2%), bicyclo[2.2.2]octa-2,5-dien (6.6%), tetradecanoic acid (4.8%), and 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-phenol (4.6%).

Compounds identified in the hexane extract of propolis by GC-MS

| Compound name | Chemical formula | MW (g/mol) | RT | Area % | Biological activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-phenol | C10H14O | 150.22 | 13.08 | 4.630 | Anticancer [36] |

| 1-Heptadecanol | C17H36O | 256.5 | 14.02 | 1.410 | — |

| Alpha-curcumene | C15H22 | 202.33 | 15.29 | 2.830 | Anticancer [37] |

| 7-Methyl-3-methylene -7-octen-1-ol | C10H18O | 154.25 | 15.69 | 2.210 | — |

| 1-Heptadecene | C17H34 | 238.5 | 16.52 | 1.580 | — |

| Guaiol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 16.83 | 1.680 | Antibacterial, insecticidal [14,15] and antitumoral [16] |

| (−)-Alpha-selinene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 17.28 | 2.000 | Anticancer [11] |

| 3,9-Epoxy-p-menthane | C10H18O | 154.25 | 17.35 | 1.370 | — |

| Alpha.-eudesmol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 17.59 | 7.230 | Anticancer [38] |

| Alpha.-bisabolol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 17.83 | 3.680 | Anticancer [39] |

| 18-Nonadecen-1-ol | C19H38O | 282.5 | 19.37 | 2.680 | — |

| Tetradecanoic acid | C14H28O2 | 228.37 | 19.52 | 4.880 | Anticancer and antioxidant [40] |

| Bicyclo[2.2.2]octa-2,5-diene | C8H10 | 106.16 | 19.65 | 6.660 | Apoptosis promoters [40] |

| cis-9,10-Epoxyoctadecan-1-o | C18H36O2 | 284.5 | 20.02 | 0.650 | Antioxidant and antibacterial activity [32] |

| (−)-Alpha-costol | C15H24O | 220.35 | 20.38 | 2.120 | — |

| Methyl ester of hexadecanoic acid | C17H34O2 | 270.5 | 20.79 | 33.600 | Anticancer and antioxidant [34,35] |

| Ethyl ester of nonadecanoic acid | C21H42O2 | 326.6 | 21.71 | 3.140 | — |

| Methyl ester of octadecanoic acid | C19H38O2 | 298.5 | 23.43 | 11.790 | Antioxidant and antifungal [41,42] |

Some of the anticancer compounds detected in hexane propolis extract.

3.7 Statistical analyses

All results represent the means ± SD from three experiments. Statistical analyses were carried using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. The results were considered statistically different when **p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried using Microsoft Excel 2016.

4 Discussion

Numerous natural compounds have been demonstrated to inhibit tumor growth, metastasis, and (or) angiogenesis through multi-target actions. This study demonstrates that a hexane (nonpolar) extract of the honey bee product propolis can dose-dependently reduce the number of viable breast, lung, colon, and lung cancer cells in vitro. A methanol (polar) extract demonstrated similar anticancer activity, albeit with less potency. Further, these cells demonstrated morphological and biochemical changes indicative of apoptosis. While the precise mechanisms of action remain to be elucidated, according to MTT assay results, the triple negative breast cancer line MDA-MB-231 was more sensitive than the MCF-7 line, suggesting that the antiproliferative and cytotoxic actions of the hexane extract are independent of estrogen receptor signaling.

Targeted apoptosis induction is one of the best promising tactics for cancer therapy [17]. Here, multiple tests demonstrated that hexane extract induced substantial apoptosis, reaching almost 90% of treated cells at 300 µg/mL. Caspases are the main effects of apoptosis, and different caspases are involved in extrinsic and intrinsic pathways [18]. Caspases cleave cellular substrates, such as PARP, during apoptosis [19,20]. We found that hexane extract induced activation of executioner caspases 3 and 7.

Current results also demonstrated the antibacterial potential of propolis extracts against Gram-positive, but not Gram species. This finding is similar to the common reports that Gram-positive bacteria are more sensitive (compared to Gram-negative) to plant extracts due to the structural differences of their cell walls and the phytochemical composition of plants [13,21,22,23,24,25]. Indeed, propolis is used in different biomedical applications for its antibacterial efficacy [26,27]. However, the mechanisms of bacterial inactivation are still unclear and warrant further study to identify the major active compounds. There are several compounds detected in hexane extract that have been reported to inhibit bacteria (Table 1).

The hexane extract also demonstrated anti-inflammatory potential in the mouse croton oil-induced inflammation, which features both edema and neutrophil infiltration [28]. n-Hexadecanoic acid was the most abundant molecule in the exact, accounting for more than 33% of the total phytocompound detected by GC-MS. In a previous enzyme kinetics study, n-hexadecanoic acid demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting phospholipase A2 [29]. Further study is required to address if this same mechanism contributes to suppression of ear inflammation induced by croton oil. These findings are in line with Menezes et al. [30], who reported that 14 ethanol extracts of propolis possess anti-inflammatory activity using a mouse ear inflammation model. Moreover, the efficacy of the hexane extract to inhibit neutrophil infiltration was comparable to the clinical topical anti-inflammatory AVOCOM.

GC-MS fingerprinting is employed to characterize the complex composition of plant extract used in traditional medicine [31]. This method was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to control the quality of plant extracts as marker components [32]. GC-MS profiling of the active extracts confirmed the presence of several classes of compounds with documented anticancer or antimicrobial activity [33]. Among these compounds were several saturated fatty acids, which are bioactive compounds found extensively in the plant kingdom. A number of studies have indicated that hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, a major compound present in the hexane extract, is also able to induce apoptosis of gastric cancer cells [34]. Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester also has demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, 5-alpha reductase inhibitory, hypocholesterolemic, pesticidal, and nematicidal activities [35]. In addition, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-phenol was found to inhibit the growth of PC3, HCT-116, and AGS cancer cells [36]. Shin and Lee found that alpha-curcumene was highly cytotoxic to human cervical cancer cells (SiHa) [37]. Numerous studies have revealed that the other compounds present in propolis hexane extract have potent cytotoxic effects on various types of cancer cell lines and microbes (Table 2). These activities may result in part from the synergistic activities of the identified compounds. Studies testing the bioactivities of these individual compounds alone and in specific combinations are warranted to identify the most potent and specific for further clinical development.

5 Conclusion

In this study, the hexane extract of propolis demonstrated potent cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines as well as antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities. GC-MS profiling revealed the presence of numerous molecules, such as hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, methyl ester of octadecanoic acid, and Guaiol with documented anticancer and antimicrobial activities. Further research is required to evaluate the subacute toxicity of hexane extract, identify additional bioactive components, and elucidate their mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Research Groups Program Grant no. (RGP-1442-0033).

-

Funding information: Financial support was by Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University.

-

Author contributions: Nael Abutaha, Mohammed AL-Zharani, Amal Alotaibi, Mary Anne W. Cordero, Asmatanzeem Bepari, and Saud Alarifi performed the experiments. Nael Abutaha carried out the analysis of data, conceived, and designed the experiment. All authors have read and agreed to the published manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no competing interests.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated are included in this article.

References

[1] Pejin B, Iodice C, Tommonaro G, Bogdanovic G, Kojic V, De Rosa S. Further in vitro evaluation of cytotoxicity of the marine natural product derivative 4′-leucine-avarone. Nat Product Res. 2014;28(5):347–50.10.1080/14786419.2013.863201Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Katiyar C, Gupta A, Kanjilal S, Katiyar S. Drug discovery from plant sources: an integrated approach. Ayu. 2012;33(1):10–9.10.4103/0974-8520.100295Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Lichota A, Gwozdzinski K. Anticancer activity of natural compounds from plant and marine environment. Int J Mol sci. 2018;19(11):3533.10.3390/ijms19113533Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Ghrairi T, Jaraud S, Alves A, Fleury Y, El Salabi A, Chouchani C. New insights into and updates on antimicrobial agents from natural products. Hindawi. 2019;2019:1–3.10.1155/2019/7079864Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Vandal J, Abou-Zaid MM, Ferroni G, Leduc LG. Antimicrobial activity of natural products from the flora of Northern Ontario, Canada. Pharm Biol. 2015;53(6):800–6.10.3109/13880209.2014.942867Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Gautam R, Jachak SM. Recent developments in anti‐inflammatory natural products. Med Res Rev. 2009;29(5):767–820.10.1002/med.20156Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Vasan N, Baselga J, Hyman DM. A view on drug resistance in cancer. Nature. 2019;575(7782):299–309.10.1038/s41586-019-1730-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Pezzuto JM, Vang O. Natural products for cancer chemoprevention: single compounds and combinations. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020.10.1007/978-3-030-39855-2Search in Google Scholar

[9] Anjum SI, Ullah A, Khan KA, Attaullah M, Khan H, Ali H, et al. Composition and functional properties of propolis (bee glue): a review. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26(7):1695–703.10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.08.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Pasupuleti VR, Sammugam L, Ramesh N, Gan SH. Honey, propolis, and royal jelly: a comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1259510.10.1155/2017/1259510Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Silva E, Estevam E, Silva T, Nicolella H, Furtado R, Alves CCF, et al. Antibacterial and antiproliferative activities of the fresh leaf essential oil of Psidium guajava L.(Myrtaceae). Brazilian J Biol. 2019;79(4):697–702.10.1590/1519-6984.189089Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Barraviera B. The journal of venomous animals and toxins including tropical diseases (JVATiTD) from 1995 to 2007. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2007;13(2):428–9.10.1590/S1678-91992007000200001Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wagh VD. Propolis: a wonder bees product and its pharmacological potentials. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2013;2013:1–11.10.1155/2013/308249Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Lotfy M. Biological activity of bee propolis in health and disease. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7(1):22–31.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Abutaha N, Al-zharani M, Al-Doaiss AA, Baabbad A, Al-Malki AM, Dekhil H. Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5. Open Chem. 2020;18(1):472–81.10.1515/chem-2020-0047Search in Google Scholar

[16] da Silva JM, Conegundes JL, Mendes Rde F, Pinto Nde C, Gualberto AC, Ribeiro A, et al. Topical application of the hexane fraction of L acistema pubescens reduces skin inflammation and cytokine production in animal model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67(11):1613–22.10.1111/jphp.12463Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Della Corte A, Chitarrini G, Di Gangi IM, Masuero D, Soini E, Mattivi F, et al. A rapid LC-MS/MS method for quantitative profiling of fatty acids, sterols, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids in grapes. Talanta. 2015;140:52–61.10.1016/j.talanta.2015.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516.10.1080/01926230701320337Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier G, Earnshaw W. Cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371(6495):346–7.10.1038/371346a0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Boulares AH, Yakovlev AG, Ivanova V, Stoica BA, Wang G, Iyer S, et al. Role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in apoptosis Caspase 3-resistant PARP mutant increases rates of apoptosis in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(33):22932–40.10.1074/jbc.274.33.22932Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Fokt H, Pereira A, Ferreira A, Cunha A, Aguiar C. How do bees prevent hive infections? The antimicrobial properties of propolis. Current Res Technol Educ Topics Appl Microbiol Microbial Biotechnol. 2010;1:481–93.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ahuja V, Ahuja A. Apitherapy-a sweet approach to dental diseases. Part II: propolis. J Adv Oral Res. 2011;2(2):1–8.10.1177/2229411220110201Search in Google Scholar

[23] Harfouch RM, Mohammad R, Suliman H. Antibacterial activity of syrian propolis extract against several strains of bacteria in vitro. World J Pharm Pharma Sci. 2016;6:42–6.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Martinotti S, Ranzato E. Propolis: a new frontier for wound healing? Burn Trauma. 2015;3(1):9.10.1186/s41038-015-0010-zSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Nedji N, Loucif-Ayad W. Antimicrobial activity of Algerian propolis in foodborne pathogens and its quantitative chemical composition. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(6):433–7.10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60601-0Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tosi B, Donini A, Romagnoli C, Bruni A. Antimicrobial activity of some commercial extracts of propolis prepared with different solvents. Phytoth Res. 1996;10(4):335–6.10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199606)10:4<335::AID-PTR828>3.0.CO;2-7Search in Google Scholar

[27] Sforcin JM, Bankova V. Propolis: is there a potential for the development of new drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133(2):253–60.10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.032Search in Google Scholar

[28] Pathak D, Pathak K, Singla A. Flavonoids as medicinal agents-recent advances. Fitoterapia. 1991;62(5):371–89.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zuzarte M, Gonçalves MJ, Cavaleiro C, Cruz MT, Benzarti A, Marongiu B, et al. Antifungal and anti-inflammatory potential of Lavandula stoechas and Thymus herba-barona essential oils. Ind Crop Products. 2013;44:97–103.10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.11.002Search in Google Scholar

[30] Menezes H, Alvarez JM, Almeidaa E. Mouse ear edema modulation by different propolis ethanol extracts. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49(8):705–7.10.1055/s-0031-1300486Search in Google Scholar

[31] Xin Z, Ren D, Zhang X, Yi Z, Yi L. Chromatographic fingerprints combined with chemometric methods reveal the chemical features of authentic radix polygalae. J AOAC Int. 2017;100(1):30–7.10.5740/jaoacint.16-0225Search in Google Scholar

[32] Fan XH, Cheng YY, Ye ZL, Lin RC, Qian ZZ. Multiple chromatographic fingerprinting and its application to the quality control of herbal medicines. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;555(2):217–24.10.1016/j.aca.2005.09.037Search in Google Scholar

[33] Bodoprost J, Rosemeyer H. Analysis of phenacylester derivatives of fatty acids from human skin surface sebum by reversed-phase HPLC: chromatographic mobility as a function of physico-chemical properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2007;8(11):1111–24.10.3390/i8111111Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yu FR, Lian XZ, Guo HY, McGuire PM, Li RD, Wang R, et al. Isolation and characterization of methyl esters and derivatives from Euphorbia kansui (Euphorbiaceae) and their inhibitory effects on the human SGC-7901 cells. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8(3):528–35.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kim YH, Chung HJ. The effects of Korean propolis against foodborne pathogens and transmission electron microscopic examination. N Biotechnol. 2011;28(6):713–8.10.1016/j.nbt.2010.12.006Search in Google Scholar

[36] Islam MT, Khalipha A, Bagchi R, Mondal M, Smrity SZ, Uddin SJ, et al. Anticancer activity of thymol: A literature‐based review and docking study with Emphasis on its anticancer mechanisms. IUBMB life. 2019;71(1):9–19.10.1002/iub.1935Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Shin Y, Lee Y. Cytotoxic activity from Curcuma zedoaria through mitochondrial activation on ovarian cancer cells. Toxicol Res. 2013;29(4):257–61.10.5487/TR.2013.29.4.257Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Wiart C. Lead compounds from medicinal plants for the treatment of cancer. United States: Academic Press; 2012. p. 110.1016/B978-0-12-398371-8.00001-5Search in Google Scholar

[39] Seki T, Kokuryo T, Yokoyama Y, Suzuki H, Itatsu K, Nakagawa A, et al. Antitumor effects of α‐bisabolol against pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(12):2199–205.10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02082.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Waisundara VY. Traditional herbal remedies of Sri Lanka. Croatia: CRC Press; 2019.10.1201/9781315181844Search in Google Scholar

[41] Sujatha M, Karthika K, Sivakamasungari S, Mariajancyrani J, Chandramohan G. GC-MS analysis of phytocomponents and total antioxidant activity of hexane extract of Sinapis alba. Int J Pharm Chem Biol Sci. 2014;4(1):112–7.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Rangel-Sánchez G, Castro-Mercado E, García-Pineda E. Avocado roots treated with salicylic acid produce phenol-2, 4-bis (1, 1-dimethylethyl), a compound with antifungal activity. J plant Physiol. 2014;171(3–4):189–98.10.1016/j.jplph.2013.07.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Nael Abutaha et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation