Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

-

Bartosz Piechowicz

, Magdalena Podbielska

Abstract

Temperature has a significant influence on the action of pyrethroids, and their effect increases with decreasing ambient temperature. Using gas chromatography, we assessed the degradation rate of λ-cyhalothrin, active ingredients (AI) of Karate Zeon 050 CS from pyrethroid group, in bees incubated for 48 h under different temperature conditions. With RT-qPCR method, we studied expression levels of selected cytochrome P450 genes after exposure to the plant protection product (PPP). The half-life of λ-cyhalothrin decreased from 43.32 to 17.33 h in the temperature range of 21–31°C. In animals incubated at 16°C, the AI half-life was even shorter and amounted to 10.19 h. The increase in temperature increased the expression of Cyp9Q1, Cyp9Q2, and Cyp9Q3 in the group of control bees. We showed a two-fold statistically significant increase in gene expression after treatment with PPP bees. The obtained results indicate that honey bees are characterized by susceptibility to pyrethroids that vary depending on the ambient temperature. This may be due to the different expressions of genes responsible for the detoxification of these PPPs at different temperatures.

1 Introduction

Foraging bees (Apis mellifera) are exposed to a variety of environmental factors, including residues from commercial plant protection products (PPPs) [1,2,3,4] and changing ambient temperatures [5]. Theoretically, gatherer bees, as heterothermic organisms, during foraging outside the hive are able to temporarily maintain the body temperature at a constant level. They spend their resting time mainly inside the hive, where, due to the presence of brood, the temperature is also constant, relatively high (33–35°C), which eliminates their exposure to low ambient temperatures. However, it often happens that on hot nights in numerous, strong families, the gatherers, being of little use in the hive, spend the night outside the nest – on the walls or hanging at the outlet. During this period, animals are exposed to unfavorable external conditions, and at the same time, they do not activate thermoregulatory mechanisms related to feeding. Similarly, bees are exposed to large fluctuations in temperature in the broodless period (from autumn to spring), which is characterized by a significantly lowered temperature in the nest. The ambient temperature and plant protection products may interact with each other [6,7], which may prove unfavorable to the functioning of a single bee. Temperature affects the stability of PPPs, their evaporation, penetration through the outer layers of the organism, and tissue penetration [8]. It also influences the physiology of the organism itself – it determines the effectiveness of the sodium/potassium pump [9], homeostasis of cell membranes [10] or the metabolic rate [11,12], which is more optimal, the more likely is the chance of a successful detoxification process [10]. The temperature may also determine the enzyme production responsible for detoxification and antioxidant mechanisms in bees [13], which may affect the neutralization of toxins. One of the most important groups of these compounds is the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. They are a large and complex group of heme-thiolate proteins that are found in almost all living organisms [14]. The detoxification process mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes is crucial in tolerating and developing pesticide resistance in many pests [15], including tolerance to pyrethroid [16], one of the most popular groups of insecticides, characterized by a complex mechanism of action [17,18]. Pyrethroids show a close dependence of their effectiveness on temperature – this dependence was called the “temperature coefficient.” Their effectiveness increases with decreasing ambient temperature [19,20,21]. For this reason, they are most often used in spring, during the flowering period of many nectarizing plants that feed bees.

The aim of the study was to estimate the rate of degradation of λ-cyhalothrin, active ingredient (AI) of Karate Zeon 050 CS (λ-cyhalothrin-based insecticide, CBI), in worker honeybees incubated after intoxication at 16, 21, 26, and 31°C. We also assessed whether λ-cyhalothrin is an expression inducer of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family – the CYP9Q subfamily, i.e., CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3, and whether the temperature of bees has an influence on this expression.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Insects used in the experiments

The experimental object in the study were gatherers of honey bees (Apis mellifera carnica) collected from the outlets of four hives located at Werynia (Poland) at the Faculty of Biotechnology of the Rzeszow University. The workers were collected from the hives between 08:00 and 09:00 a.m., 40 min against intoxication. In order to calm down, all insects were incubated at 7°C for 30 min before intoxication.

2.2 Insecticide

KarateZeon 050 CS (Syngenta Limited, Great Britain) containing λ-cyhalothrin ([α-cyano-3-phenoxybenzyl 3-(2-chloro-3.3.3-trifluoro-1-propenyl)-2.2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylate], type II pyrethroid insecticide) (50 g per L of the insecticide) as an AI was used in the experiments. The applied dose of the preparation was 20 µL L−1.

2.3 Intoxication

Intoxication was performed using the solution obtained by dissolving 5 µL of Karate-Zeon 050 CS in 1 L of distilled water. Bees were exposed to 5 µL of distilled water (the control group) or the CBI solution, applied topically on the dorsal part of their prothorax. After intoxication, the bees in groups of 10 (always from the same hive) were placed in Petri dishes where they had unlimited access to vessels containing 50% m v−1 sucrose syrup. The dishes were kept in constant darkness in a laboratory incubator S 711 (Chłodnictwo-Madej, Poland) at different temperatures: 16, 21, 26, or 31°C.

After 2, 6, 12, 24, or 48 h of incubation, subsequent dishes were removed from the incubator and were frozen for further analyses. For each application temperature (16, 21, 26, and 31°C) and each termination time (2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h), four replicates of 10 individuals were used (extraction of the residue was carried out in each case from three samples).

The insects intended for gene expression tests were treated with CBI (in the control sample – with water), in the same way as the bees used for the analysis of the λ-cyhalothrin degradation rate. For this experiment, the incubation of the insects was completed 6 h after intoxication each time.

2.4 Extraction of λ-cyhalothrin residues from bees

An analytical portion of lyophilized bees (Labconco Freezone 2.5 freeze dryer, Labconco, USA; pressure: 0.024 mbar; temperature: 50°C; time: 168 h) was shaken for 2 min with 10 mL of water and 10 mL of acetonitrile (Chempur, Poland). About 4 g of anhydrous magnesium sulfate(vi) (Chempur, Poland), 1 g of sodium chloride (Chempur, Poland), 1 g of trisodium citrate (Chempur, Poland), and 0.5 g of sesquihydrate disodium hydrogen citrate (Chempur, Poland) was added, and the contents were shaken for next 2 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 4,500 rpm. Then, 6 mL of the acetonitrile phase was transferred to a polypropylene tube containing 150 mg of the primary secondary amine (Agilent, USA) and 900 mg of anhydrous sodium sulfate(vi) (Chempur, Poland) and vigorously shaken for 2 min and centrifuged for 5 min under the same conditions as before. Finally, 4 mL of the obtained extract was collected, transferred to a glass flask, evaporated in a helium stream of purity 5.0, and dissolved in 4 mL of petroleum ether (Chempur, Poland).

2.5 Chromatography analysis

The obtained extracts were analyzed using the Agilent 7,890 gas chromatograph (Agilent, USA), equipped with an electron capture detector (µECD). The chromatograph was operated via ChemStation software and equipped with an autosampler and an HP-5MS column (30 m: 0.32 mm: 0.25 mm). The following chromatographic conditions were used: µECD detector temperature, 290°C; injector temperature, 250°C. The oven temperature was programmed as follows: 100°C – 0 min → 10°C min−1 → 180°C – 4 min → 3°C min−1 → 220°C – 15 min → 10°C min−1 → 260°C – 20 min. The total analysis time was 64.33 min. The injection volume was 1 µL.

2.6 Analytical standards

A certified pesticide analytical standard was obtained from The Institute of Industrial Organic Chemistry (Poland). For linearity determinations, standard solutions in the clean matrix were prepared at the following standard concentrations: 0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.50, and 1.0 mg L−1. Linearity was described with determination coefficients (R 2 > 0.99). Excellent linearity was achieved for the studied pesticide when using a matrix-matched standard. The limit of quantification values were the lowest at a spiked level (0.001 mg kg−1).

2.7 Validation of the analytical method

Recoveries of two λ-cyhalothrin isomers were 72.6% (SD = 5.7%; RSD/CV = 8.87%) and 85.8% (SD = 5.7%; RSD/CV = 6.66%), which means the values obtained were within the assumed range of 70–120% [22].

2.8 RNA isolation

The total bee RNA used for the analysis was isolated from 20 adults by pretreating them with liquid nitrogen and grinding them in a mortar. The next stages of the RNA extraction procedure were performed using the setup for RNA isolation, GenEluteMammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma Aldrich, USA). RNA was eluted from columns using 30 µL of RNase-free water. RNA concentration and purity in samples were assessed using a NanoDrop™ Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). RNA samples with ratios OD260/280 = 1.8:2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0 > 500 ng were used for further analysis.

2.9 cDNA synthesis

About 300 ng of RNA from each isolated sample was subjected to reverse transcription at 50°C for 1 h, using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, USA). For this purpose, we prepared a mixture consisting of 300 ng of RNA, 1 µL of (dT)18 starter, 2 µL of Random HEK starter, and nuclease-free water (to a final volume of 13 µL). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 65°C and then cooled on ice. Depending on the number of analyzed samples, we prepared a sufficient quantity of the reaction mixture, mixing its component in the right proportions. A composition for a single sample was as follows: 4 µL of reaction buffer, 0.5 µL of 40 U µL−1 RNase inhibitor, 2 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, and 0.5 µL of 20 U µL−1 reverse transcriptase. Control samples (-RT) were prepared in the same manner, with the reverse transcriptase replaced with an identical volume of nuclease-free water. The obtained cDNA was diluted 10 times with RNase-free water and stored at −20°C.

2.10 Analysis of the transcriptional activity of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family, involved in detoxification – CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3, using the real-time qPCR technique

About 10 µL of the reaction mixture containing 1 µL of 10 times diluted cDNA sample, 5 µL of LightCycler Master Mix (Roche, Switzerland), 0.25 µL of 10 µM solutions of both forward and reverse primers (Table 1), and 3.5 µL of nuclease-free distilled water was prepared for the RT-qPCR analysis.

Sequences of primers of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family involved in detoxification – CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 [23]

| Primers | Primer sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| CYP9Q1 | Forward: TCGAGAAGTTTTTCCACCG |

| Reverse: CTCTTTCCTCCTCGATTG | |

| CYP9Q2 | Forward:GATTATCGCCTATTATTACTG |

| Reverse: GTTCTCCTTCCCTCTGAT | |

| CYP9Q3 | Forward: GTTCCGGGAAAATGACTAC |

| Reverse: GGTCAAAATGGTGGTGAC | |

| Reference gene | Forward: GAGTGTCTGCTATGGATTGCAA |

| eIF3-S8 | Reverse: TCGCGGCTCGTGGTAAA |

We performed a comparative qPCR analysis using Roche LightCycler® 480, according to the producer’s protocol. We started with the initial sample denaturation in 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 min, with the denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, primers connected at 56°C for 20 s, and strand extension at 72°C for 20 s. The reaction was stopped by cooling samples to 40°C for 10 s. To eliminate nonspecific amplification, the melting curve of the obtained products was also analyzed.

Using Roche LightCycler® 480 Software, we analyzed the reference CYP9Q transcript levels for the endogenous control eIF3-S8 (a translation initiation factor involved in cell proliferation).

2.11 Analysis of the results

The average-adjusted residue levels of the two λ-cyhalothrin isomers (summed values) were calculated and their degradation trends were expressed as exponential equation (1):

where R t is the concentration (residue) of any pesticide after t time (in h), R 0 is the initial concentration of the pesticide (in mg kg−1), and k is the rate constant (in h−1).

The half-lives were calculated using equation (2):

where k is the rate constant (in h−1).

The Q 10 coefficient for the test of degradation was calculated according to formula (3):

where W 2 is the degradation time obtained at a higher temperature, W 1 is the degradation time obtained at a lower temperature, T 2 is the higher temperature (°C), and T 1 is the lower temperature (°C).

The results of the gene expression analysis are presented as the arithmetic mean ± SD (standard deviation). The statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 5. The differences with the p < 0.05 coefficient were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Influence of temperature on the course of λ-cyhalothrin degradation in honey bees

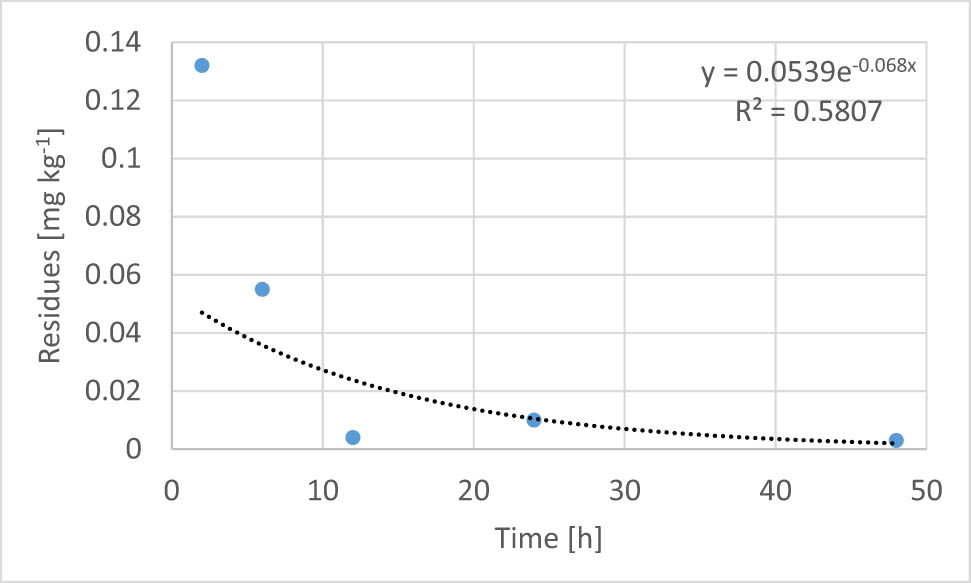

Two hours after poisoning in bees kept at 31, 26, 21, and 16°C, the residues of λ-cyhalothrin were 0.049, 0.116, 0.086, and 0.132 mg kg−1, respectively (Table 2, Figure 1).

Residues (mg kg1) of λ-cyhalothrin in honey bees, 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after poisoning and the parameters of their exponential degradation

| Time (day) | Mean ± SD λ-cyhalothrin residue in bee samples (mg kg−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31°C | 26°C | 21°C | 16°C | |

| 2 h | 0.049 ± 0.023 | 0.116 ± 0.087 | 0.086 ± 0.037 | 0.132 ± 0.100 |

| 6 h | 0.065 ± 0.091 | 0.043 ± 0.020 | 0.013 ± 0.005 | 0.055 ± 0.012 |

| 12 h | 0.030 ± 0.033 | 0.024 ± 0.018 | 0.020 ± 0.004 | 0.004 ± 0.002 |

| 24 h | 0.044 ± 0.056 | 0.023 ± 0.011 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.010 ± 0.005 |

| 48 h | 0.008 ± 0.009 | 0.020 ± 0.009 | 0.022 ± 0.002 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| 0–48 h | R t = 0.0666e−0.04t | R t = 0.0594e−0.028t | R t = 0.0266e−0.016t | R t = 0.0539e−0.068t |

| r² = 0.6117 | r² = 0.5187 | r² = 0.2424 | r² = 0.7582 | |

| T1/2 | 17.33 | 24.76 | 43.32 | 10.19 |

Exponential degradation trend of λ-cyhalothrin residues in bees incubated at 16°C (n = 3).

The exponential equations describe very poorly (r 2 = 0.2424), poorly (r 2 = 0.5187 and 0.6117), and well (r 2 = 0.7582) the course of λ-cyhalothrin degradation in the bee tissues (Table 2, Figure 1). Specified degradation constants (k), respectively, 0.04 (31°C), 0.028 (26°C), 0.016 (21°C) and 0.068 (16°C) indicate the rapid detoxification of λ-cyhalothrin by bees. Based on equation (2), the AIs of PPP half-life were calculated and were 17.33, 24.76, 43.32, and 10.19 h, respectively. Based on these values, the Q 10 coefficients were calculated as 1.42 (in the range 16–31°C), 0.40 (21–31°C), 0.49 (26–31°C), 2.43 (16–26°C), 0.33 (21–26°C), and 18.07 (16–21°C).

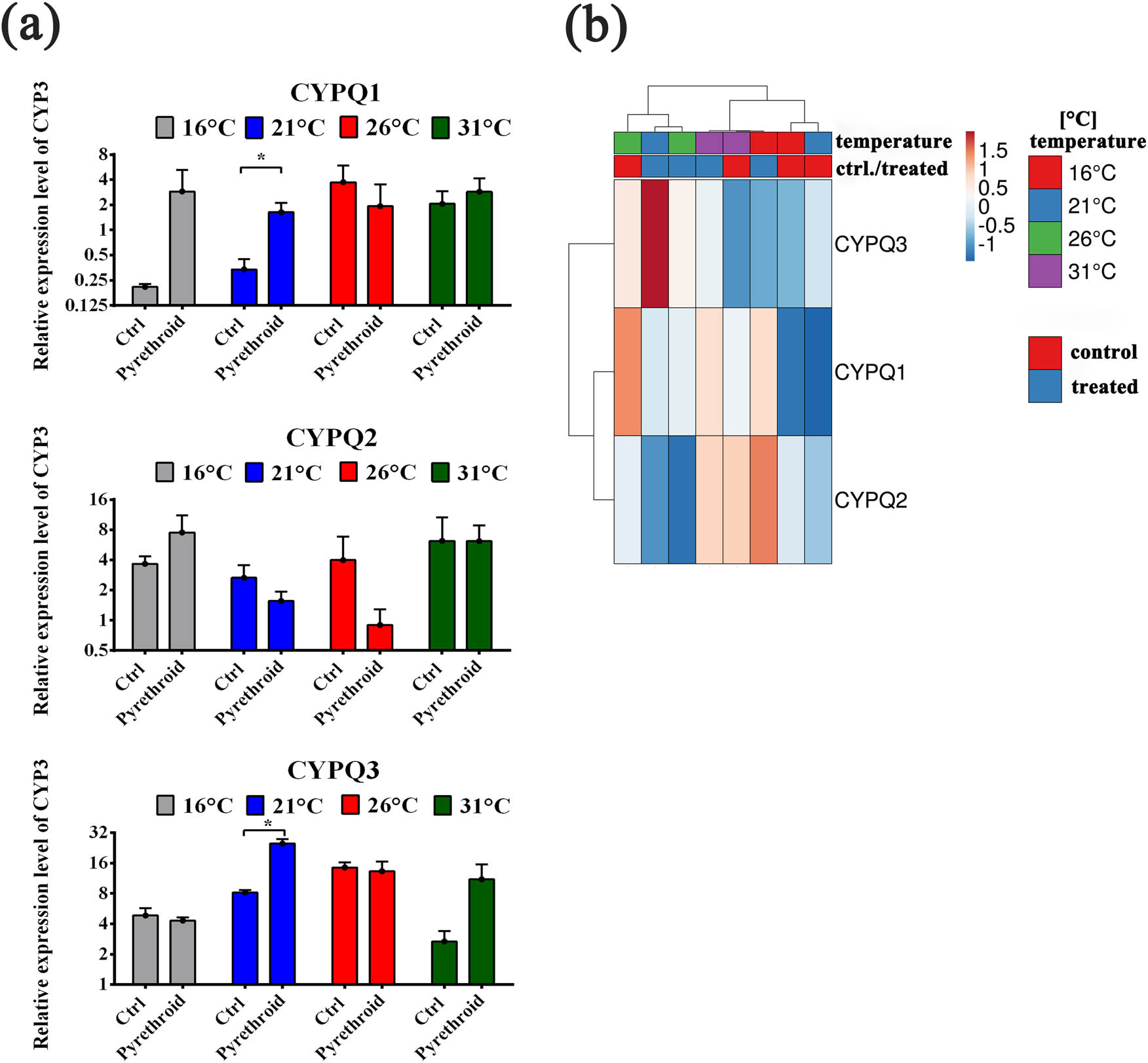

3.2 Transcriptional activity of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family involved in detoxification of CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 under various temperature conditions

In the conducted studies the expression profile of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family taking part in the first stage of detoxification of xenobiotics, i.e., CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 in Apis meliffera in response to heat stress (Figure 2) was analyzed. The results showed a statistically significant increase in the expression of CYP9Q1 and CYP9Q3 genes during the detoxification of the applied PPP at 21°C compared to the control. At a temperature of 16°C, an increase in the mRNA level of the CYP9Q1 and CYP9Q2 genes was observed, compared to the control group. Analysis of the expression of genes involved in detoxification at higher temperatures (31°C) showed an increase in mRNA of the CYP9Q3 gene.

(a) Semiquantitative evaluation of the expression of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family involved in detoxification – CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3. Real-time PCR method. The bars show the relative expression of the gene tested in relation to the expression of the eIF3-S8 gene; the mean of three determinations with SD is marked. It differs from the control: *p < 0.05. (b) The heat map generated on the basis of the comparison of the transcriptional profile of genes encoding cytochrome P450 isoenzymes belonging to the CYP3 family involved in detoxification – CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 at various intoxication temperatures of bees (16, 21, 26, 31°C). Hierarchical clustering was performed using ClustVis, an online tool for clustering multidimensional data (BETA) (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/).

In control bees, in most cases, there was an increase in gene expression with an increase in their incubation temperature; in the case of Cyp9Q3, in the temperature range 16–26°C, the increase was statistically significant. A similar significance was also observed for the reduction of the rate of Cyp9Q3 expression in the temperature range 26–31°C. Only in one case (16–21°C), the temperature caused a significant change in the level of gene expression (Cyp9Q3) in intoxicated bees.

4 Discussion

Pyrethroids are compounds derived from natural pyrethrins, with a nonselective, complex mechanism of action. They disturb the dynamics of sodium channels by extending their opening time [24]. They are also agonists of T-type calcium channels in the insect muscles [25], and the conduction of impulses in the muscles of bees is due to calcium ions [26]. Moreover, pyrethroids reduce the mitochondrial complex by inhibiting succinate and glutamate [27]. They also disrupt the phosphorylation of proteins [28] and modify the function of proteins, which create intracellular gap junctions [29] and induce strong oxidative stress [30]. Despite these multiple mechanisms of action, pyrethroids are frequently used because they have low mammalian toxicity and a short half-life in their tissues. Anadón et al. [17] indicate that this time depends both on the form of administration (intravenous, nutritionally) and of the examined tissues. In their research, λ-cyhalothrin administered intravenously to rats disappeared in plasma after less than 8 h, and nutritionally after less than 11 h after intoxication. In the case of neuromuscular fibers, this time was extended to 26 and 34 h, respectively. In bees, this time calculated using the exponential equation was similar and ranged from 10.19 to 43.32 h (in temperature 26°C T1/2 = 24.76 h), longer than we observed in our previous studies [31], whereas in bees incubated at 26°C, the half-life was 14 h. During the research, the insects were incubated in constant darkness, the conditions that prevail at night outside the hive; for bee-gatherers, not dealing directly with work in the hive, they happen to spend resting periods. This period is characterized by a significant slowdown in the pace of metabolic changes [32]. In earlier studies, incubation has been associated with constant exposure to light and it probably contributed to the observed difference in the rate of AI decomposition.

In bees incubated in the temperature range of 31–21°C, the time of AI decomposition increased with the decrease of the ambient temperature, ranging from 17.33 to 43.32 h, and then decreased in the temperature range of 16°C T1/2 = 10.19 h (Table 2). This may be due to the heterothermal nature of bee-gatherers. Probably in the temperature range of 31–21°C, they kept their body temperature close to the ambient temperature, which resulted in nearly two times, according to the van’t Hoff-Arrhenius [33] rule, the slowdown in the rate of metabolic changes estimated on the basis of changes in the decomposition rate of λ-cyhalothrin (Q 10 = 0.40). At 16°C, the insects activated the mechanisms of thermogenesis, needed to maintain the temperature necessary to maintain efficiency and readiness for feeding, which could indirectly contribute to faster AI decomposition (Q 10 = 2.43 and Q 10 = 18.07, respectively in the range of 16–26°C and 16–21°C). Kovac et al. [34], analyzing the temperature of individual parts of the body of bees under various thermal conditions of the environment, observed significantly greater differences at 15°C in the temperature of the body and belly of these insects than at 26 or 38°C pointing to the existence of efficient thermogenesis in worker bees at lower ambient temperatures.

Bees are organisms that can precisely regulate their body temperature, which theoretically could withstand the temperature effect of PPPs. However, in the absence of brood (no brood tests were used in the experiment), the thermogenesis process starts only at lower temperatures, which may significantly affect the rate of detoxification of insects. Additionally, pyrethroids belong to agents where insecticidal activity increases with decreasing temperature [19,20]. It has also been shown that deltamethrin, another AI from the pyrethroids group, causes hypothermia in bees incubated at 22°C [35], which may also affect the level of thermogenesis in these animals, and thus, indirectly the efficiency of their detoxification.

Transcription of CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 belonging to the CYP3 group and taking part in the first stage of detoxification of xenobiotics is modulated in A. mellifera, incl. by tau-fluvalinate and bifenthrin (AIs from the pyrethroid group). This clan midgut P450s metabolizes pyrethroids to a form suitable for further cleavage by the carboxylesterases that also contribute to tau-fluvalinate tolerance [23]. As shown in the metabolism of cypermethrin in Helicoverpa armigera, carboxylesterases also metabolize hydroxylated metabolites of pyrethroids generated by P450s [36].

We also observed changes in the transcriptional activity of CYP9Q1, CYP9Q2, and CYP9Q3 in our studies. In control bees incubated at lower temperatures (16–21°C), we observed a clear, although not significantly lower than at 26 and 31°C, the transcriptional activity of genes encoding Cyp9Q1 and Cyp9Q2. In the case of Cyp9Q3, the observed increase in protein transcriptional activity along with the temperature increase from 16 to 26°C proved to be statistically significant. Li et al. [13] also indicated that with increasing ambient temperature in A. cerana and A. mellifera, there is an increase in oxidative stress, which induces an increase in the activity of detoxification and antioxidant enzymes. Probably, just low oxidative stress and the accompanying decreased transcriptional activities of Cyp9Q1, Cyp9Q2, and Cyp9Q3 genes in the groups incubated at lower temperatures may be responsible for the negative temperature coefficient of pyrethroids. It seems that despite the high increase in Cyp9Q1 expression at 16 and 21°C, Cyp9Q2 at 16°C and a statistically significant increase in Cyp9Q3 expression at 21°C after PPP use, the time required to activate the body’s protective mechanisms is too long to prevent bees against the harmful multidirectional effects of the CBI. This means that the stress to which bees incubated at higher temperatures are exposed can practically increase their chances of survival when an additional toxic factor appears that requires the involvement of detoxification and antioxidant processes. On the other hand, the low temperature to which gatherers sleeping outside in the hive are sometimes exposed can pose a risk to them, especially in combination with hypothermic pyrethroids, which are highly effective in cooler environments.

5 Conclusion

The obtained results show that the temperature significantly influences the half-life of λ-cyhalothrin in A. mellifera worker-gatherers. The fastest decomposing of AI was in bees incubated at 16°C (10.19 h), and the slowest (43.32 h) – at 21°C. The fastest rate of detoxification of bees incubated at 16°C indicates the occurrence in these insects periodically, depending on the ambient temperature, the ability to increase the rate of metabolic changes.

With increasing temperature, the expression of genes involved in pyrethroids detoxification usually increased (statistically significant for Cyp9Q3 in the range of 16–26°C) in the control bees. The treatment of bees with PPPs only in two cases (Cyp9Q1 and Cyp9Q3; 21°C) resulted in a significant increase in the expression of detoxification genes in the studied workers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eng. Kazimierz Czepiela for help in carrying out this research. The study was supported by funds from the University of Rzeszow, College of Natural Sciences.

-

Funding information: The research was supported by the statutory fund of the College of Natural Sciences of the University of Rzeszów.

-

Author contributions: The conception and design of the study – BP, LP. Insects incubation – BP, MK. Preparation of samples for analysis – BP, MK. Chromatographic analysis – ES, MPo. Molecular analysis – LP, MK. Analysis and interpretation of data – BP, LP, MPi, AK. Drafting the article – BP, AK, LP. Final approval of the version to be submitted – BP, AK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding or the first author on request.

References

[1] Piechowicz B, Grodzicki P, Podbielska M, Tyrka N, Śliwa M. Transfer of active ingredients from plant protection products to a honeybee (Apis mellifera) hive from winter oilseed rape crops protected with conventional methods. Pol J Env Stud. 2018;27:1219–28.10.15244/pjoes/76362Search in Google Scholar

[2] Piechowicz B, Wos I, Podbielska M, Grodzicki P. The transfer of active ingredients of insecticides and fungicides from an orchard to beehives. J Env Sci Health B. 2018;53:18–24.10.1080/03601234.2017.1369320Search in Google Scholar

[3] Niell S, Jesús F, Pérez N, Pérez C, Pareja L, Abbate S, et al. Neonicotinoids transference from the field to the hive by honey bees: towards a pesticide residues biomonitor. Sci Total Env. 2017;581–582:25–31.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.011Search in Google Scholar

[4] Calatayud-Vernich P, Calatayud F, Simó E, Aguilar JAP, Yolanda, Picó Y. A two-year monitoring of pesticide hazard in-hive: high honey bee mortality rates during insecticide poisoning episodes in apiaries located near agricultural settings. Chemosphere. 2019;232:471–80.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.170Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sánchez-Echeverría K, Castellanos I, Mendoza-Cuenca L, Zuria I, Sánchez-Rojas G. Reduced thermal variability in cities and its impact on honey bee thermal tolerance. Peer J. 2019;7:e7060.10.7717/peerj.7060Search in Google Scholar

[6] Glunt KD, Oliver SV, Hunt RH, Paaijmans KP. The impact of temperature on insecticide toxicity against the malaria vectors Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. Malar J. 2018;17:131.10.1186/s12936-018-2250-4Search in Google Scholar

[7] Piechowicz B, Grodzicki P. Effect of temperature on toxicity of selected insecticides to forest beetle Anoplotrupes stercorosus. Chem Didact Ecol Metrol. 2013;18:103–8.10.2478/cdem-2013-0023Search in Google Scholar

[8] Horn D. Temperature synergism in integrated pest management. In: Hollman GJ, Denlinger DL, editors. Temperature sensitivity in insects and application in integrated pest management. Boulder, CO, USA; Oxford, UK: Westview Studies in Insect Biology, Westview Press; 1998.10.1201/9780429308581-5Search in Google Scholar

[9] Pierau FK, Torrey P, Carpenter D. Mammalian cold receptor afferents: role of an electrogenic sodium pump in sensory transduction. Brain Res. 1974;73:156–60.10.1016/0006-8993(74)91015-4Search in Google Scholar

[10] Tęgowska E. Insecticides and thermoregulation in insects. Pestycydy/Pesticide. 2003;1–4:47–75.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Piechowicz B, Gola J, Grodzicki P, Piechowicz I. Selected insecticides and acaricide as modifiers of the metabolic rate in the beetle Anoplotrupes stercorosus under various thermal conditions: the effect of pirimicarb, diazinon and fenazaquin. Acta Sci Pol, Silvarum Colendarum Ratio Ind Lignaria. 2014;13:19–29.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Maliszewska J, Tęgowska E. Is there a relationship between insect metabolic rate and mortality of mealworms Tenebrio molitor L. after insecticide exposure? J Cent Eur Agric. 2016;17:685–94.10.5513/JCEA01/17.3.1763Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li X, Ma W, Shen J, Long D, Feng Y, Su W, et al. Tolerance and response of two honeybee species Apis cerana and Apis mellifera to high temperature and relative humidity. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217921.10.1371/journal.pone.0217921Search in Google Scholar

[14] Yu L, Tang W, He W, Ma X, Vasseur L, Baxter SW, et al. Characterization and expression of the cytochrome P450 gene family in diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.). Sci Rep. 2015;5:8952.10.1038/srep08952Search in Google Scholar

[15] Li X, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;52:231–53.10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151104Search in Google Scholar

[16] Johnson RM, Wen Z, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Mediation of pyrethroid insecticide toxicity to honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. J Econ Entomol. 2006;99:1046–50.10.1093/jee/99.4.1046Search in Google Scholar

[17] Anadón A, Martínez-Larrañaga MR, Martínez MA. Use and abuse of pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids in veterinary medicine. Vet J. 2009;182:7–20.10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.04.008Search in Google Scholar

[18] Anadón A, Arés I, Martínez MA, Martínez-Larrañaga MR. Pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids: use in veterinary medicine. In: Ramawat K, Mérillon JM, editors. Natural products. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. 10.1007/978-3-642-22144-6_131.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Khan HAA, Akram W. The effect of temperature on the toxicity of insecticides against Musca domestica L.: implications for the effective management of diarrhea. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95636.10.1371/journal.pone.0095636Search in Google Scholar

[20] Harwood AD, You J, Lydy MJ. Temperature as a toxicity identification evaluation tool for pyrethroid insecticides: toxicokinetic confirmation. Env Toxicol Chem. 2009;28:1051–8.10.1897/08-291.1Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ahn YJ, Shono T, Fukami JI. Effect of temperature on pyrethroid action to Kdr-type house fly adults. Pest Biochem Physiol. 1987;28:301–7.10.1016/0048-3575(87)90124-6Search in Google Scholar

[22] European Commission, 2019. Analytical quality control and method validation procedures for pesticide residues analysis in food and feed. SANTE/12682/2019. Eur Comm Dir Heal Food Safety. https://www.eurl-pesticides.eu/docs/public/tmplt_article.asp?CntID=727.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. CYP9Q-mediated detoxification of acaricides in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). PNAS. 2011;108:12657–62.10.1073/pnas.1109535108Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Wang SY, Wang GK. Voltage-gated sodium channels as primary targets of diverse lipid-soluble neurotoxins. Cell Signal. 2003;15:151–9.10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00085-2Search in Google Scholar

[25] Aldridge WN. An assessment of the toxicological properties of pyrethroids and their neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1990;21:80–104.10.3109/10408449009089874Search in Google Scholar

[26] Collet C, Belzunces L. Excitable properties of adult skeletal muscle fibres from the honeybee Apis mellifera. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:454–64.10.1242/jeb.02667Search in Google Scholar

[27] Gasner B, Wuthrich A, Sholtysik G, Solioz M. The pyrethroids permetrin and cyhalothrin are potent inhibitors of the mitochondrial complex I. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:855–60.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Soderlund D, Clark JM, Sheets LP, Mullin LS, Piccirillo VJ, Sargent D, et al. Mechanism of pyrethroid neurotoxicity: implications for cumulative risk assessment. Toxicology. 2002;171:3–59.10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00569-8Search in Google Scholar

[29] Papaefthimiou C, Theophilidis G. The cardiotoxic action of the pyrethroid insecticide deltamethrin, the azole fungicide prochloraz, and their synergy on the semi-isolated heart of the bee Apis mellifera macedonica. Pest Biochem Physiol. 2001;69:77–91.10.1006/pest.2000.2519Search in Google Scholar

[30] Atere AD, Oseni BSA, Agbona TO, Idomeh FA, Akinbo DB, Osadolor HB. Free radicals inhibit the haematopoietic elements and antioxidant agents of rats exposed to pyrethroids insecticides. J Exp Res. 2019;7:66–74.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Piechowicz B, Sadło S, Woś I, Białek J, Depciuch J, Podbielska M, et al. Treating honey bees with an extremely low frequency electromagnetic field and pesticides: impact on the rate of disappearance of azoxystrobin and λ-cyhalothrin and the structure of some functional groups of the probabilistic molecules. Env Res. 2020;190:09989.10.1016/j.envres.2020.109989Search in Google Scholar

[32] Grodzicki P, Piechowicz B, Caputa M. Effect of the own vs. foreign colony odor on daily shifts in olfactory and thermal preference and metabolic rate of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) workers. J Apic Res. 2020;59:691–702.10.1080/00218839.2020.1769276Search in Google Scholar

[33] Běhrádek J. Temperature coefficients in biology. Biol Rev. 1930;5:30–58.10.1111/j.1469-185X.1930.tb00892.xSearch in Google Scholar

[34] Kovac H, Stabentheiner A, Hetz SK, Petz M, Crailsheim K. Respiration of resting honeybees. J Insect Physiol. 2007;53:1250–61.10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.06.019Search in Google Scholar

[35] Vandame R, Belzunces LP. Joint actions of deltamethrin and azole fungicides on honey bee thermoregulation. Neurosci Lett. 1998;251:57–60.10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00494-7Search in Google Scholar

[36] Lee KS, Walker CH, McCaffery AR, Ahmad M, Little E. Metabolism of transcypermethrin by Heliothis armigera and H. virescens. Pest Biochem Physiol. 1989;34:49–57.10.1016/0048-3575(89)90140-5Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Bartosz Piechowicz et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation