Abstract

Curcumin has been known and used in the medical and industrial world. One way to improve its stability, bioavailability and its medical applications is using encapsulation method. In this research, we studied cocoliposome (coconut liposome) as the encapsulation material. The encapsulation efficiency (EE), loading capacity (LC), release rate (RR), as well as the free radical scavenging activity, measured by inhibition ratio (IR), of curcumin in encapsulation product were studied on varying cholesterol compositions and in simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH 1.2) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 7.4) conditions. We found that curcumin encapsulation in cocoliposome (CCL) formulation was influenced by cholesterol composition and pH conditions. The EE, LC and free radical scavenging activity diminished under both the SIF and SGF conditions when the cholesterol concentration enhanced. However, the RR increased as the cholesterol intensified. The condition to acquire the most favorable encapsulation parameter values was at 10% cholesterol composition. Furthermore, the IR results at 10% cholesterol concentration of CCL was 67.70 and 82.13% in SGF and SIF milieu, respectively. The CCL formulation thrived better under SIF conditions for free radical scavenging activities.

1 Introduction

Curcumin has been known and used in the medical and industrial world. Curcumin or diferuloat methane is a natural polyphenol phytochemical compound obtained from Curcuma longa (turmeric) extract [1]. Curcumin has been widely used as a drug due to its bioactivity as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and anti-tumor agent with low toxicity [2,3]. Curcumin is also used as chemopreventive agents in various types of cancer, such as leukemia and lymphoma, gastrointestinal cancer, genitaurinary cancer, nerve cancer and sarcoma, breast cancer and lung cancer [4]. Despite these broad applications, the therapeutic functions are hindered by low bioavailability [5]. The low bioavailability of curcumin is instigated by low level of solubility in aqueous media, low stability at basic pH, and easy elimination from the body [6]. Proper and careful design of a delivery system can significantly increase bioavailability.

Various delivery methods of active ingredients have been developed, and one of them is liposomes. Liposomes are chosen as a delivery system due to their sustainable, biodegradable, nontoxic and nonimmunogenic nature [7]. Liposomes are widely used as a delivery system to stabilize drugs and overcome problems in bioavaibility [8]. Liposomes are microscopic bilayer vesicles made from phospholipids dispersed in aqueous media. Exploration on liposomes from various natural resources has been conducted to acquire the desired results [9,10,11,12,13,14]. At present, an ongoing exploration of natural liposomes is the cocoliposome, which is made from CocoPLs [15,16,17].

Research on cocoliposome includes its ability to encapsulate a variety of active materials involving vitamin C, beta-carotene, cinnamic acid and galangal extract [18,19]. Although further research is needed, cocoliposome has indeed shown prospects as delivery systems for both polar and nonpolar substances. To know better about the nature of cocoliposome as delivering tool for various active matters, in this study, we explored the cocoliposome for encapsulating curcumin. Encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome (CCL) formulation was carried out with the desire of increasing its bioavailability, biocompatibility and stability. We scrutinized the CCL parameters in simulated intestinal Fluid (SIF) and simulated gastric fluid (SGF) environments separately.

Furthermore, cholesterol is an important component in liposomal formulations. Cholesterol affects liposome stability, drug encapsulation efficiency and control liposome release. It plays an important role in controlling physical and chemical properties of liposome, such as membrane flexibility and rigidity [20,21]. In relation to the effectiveness of liposomes as a delivery system for curcumin, the composition of the liposomal membrane is very important. It is known that the presence of cholesterol in the liposome membrane is very essential [20,22,23]. It is related to the physical properties of the membrane, its permeability and the ability of the liposome as a carrier system of curcumin. To comprehend how cholesterol influences the curcumin encapsulation in cocoliposome, we added cholesterol in various compositions to the formulations. We also explored the scavenging activity of CCL preparations. To our knowledge, this is the first report presenting the in vitro study of cocoliposome encapsulation ability for curcumin. The present discovery provides evidence on the encapsulation capability of cocoliposome especially for polyphenolic compounds such as curcumin.

The relationship between the liposome composition, the environment where the liposome will be used, and the encapsulation parameters can be delicate and unforeseen. It can also influence the intended effect of the encapsulated material. The aim of this research was to further characterize the encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome in both SIF and SGF environments by exercising important parameters in encapsulation process and curcumin antioxidant property.

2 Methods

2.1 Preparation of coconut phospholipid (CocoPLs)

Coconut phospholipid (CocoPLs) was isolated in-house using Hudiyanti’s procedure (1,2). Concisely, CocoPLs extraction procedure is divided into extraction by soaking dry coconut powder in chloroform/methanol (2/1) mixture followed by solvent partition of the liquid extract in hexane and ethanol 87% solvent. Finally, the ethanol layer was evaporated to obtain CocoPLs. CocoPLs obtained was used to prepared liposomes.

2.2 Simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) solution preparation

Two homogeneous solutions of 7.5 g of Na2HPO4·2H2O (0.05 M) and 3.9 g of NaH2PO4·2H2O (0.05 M) in 500 mL of demineralized water were prepared, respectively. About 9.5 mL of NaH2PO4·2H2O (0.05 M) and 40.5 mL of Na2HPO4·2H2O (0.05 M) solutions were mixed. The solution was diluted to 100 mL and adjusted to pH 7.4.

2.3 Preparation of simulated gastric fluid (SGF) solution

Two grams of NaCl was dissolved in 800 mL of demineralized water. A solution of 4.5 mL of 37% HCl was added to the NaCl solution drop by drop, followed by demineralized water to reach 1 L in volume. The pH was adjusted to 1.2.

2.4 Preparation of curcumin standard curve

Two milligrams of curcumin was dissolved in 100 mL ethanol to obtain 50 ppm curcumin stock solution. An array of curcumin solution with concentrations 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5 and 6 ppm was made from the stock solution. The λ max (426 nm) of the curcumin was determined using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, and the standard curve was established from the array of curcumin solutions.

2.5 Preparation of curcumin loaded coconut liposomes (CCL)

CCL was prepared in five formulations composed of CocoPLs, cholesterol (Chol) and curcumin (Cur). The formulation is presented in Table 1. Each formula was dissolved in 100 mL of chloroform/methanol (9:1, v/v). A 10 mL solution of LC0 was placed in a reaction tube and nitrogen gas was streamed into the tube until all solvent evaporated leaving a thin film at the bottom of the tube. Then, 10 mL SIF solution was poured into the tube. The tube was then exposed to freeze-thawing cycles at 4°C cooling and 45°C heating until the thin film was dispersed. The procedure of freeze-thawing cycles was adapted from the study by Hudiyanti et al. [15,18,19]. The dispersion was then sonicated at 27°C for 30 min. This process was repeated for every formula in Table 1 with SIF and SGF solutions. There were 10 diverse dispersions under 2 simulated conditions, alkaline for SIF (pH 7.4) and acidic for SGF (pH 1.2) solution, respectively.

Formulation of curcumin-loaded coconut liposomes (CCL) dispersions

| CCL formulation | Composition (w/w/w) in mg | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CocoPLs | Chol | Cur | |

| LC0 | 125 | 0 | 1 |

| LC10 | 125 | 12.5 | 1 |

| LC20 | 125 | 25 | 1 |

| LC30 | 125 | 37.5 | 1 |

| LC40 | 125 | 50 | 1 |

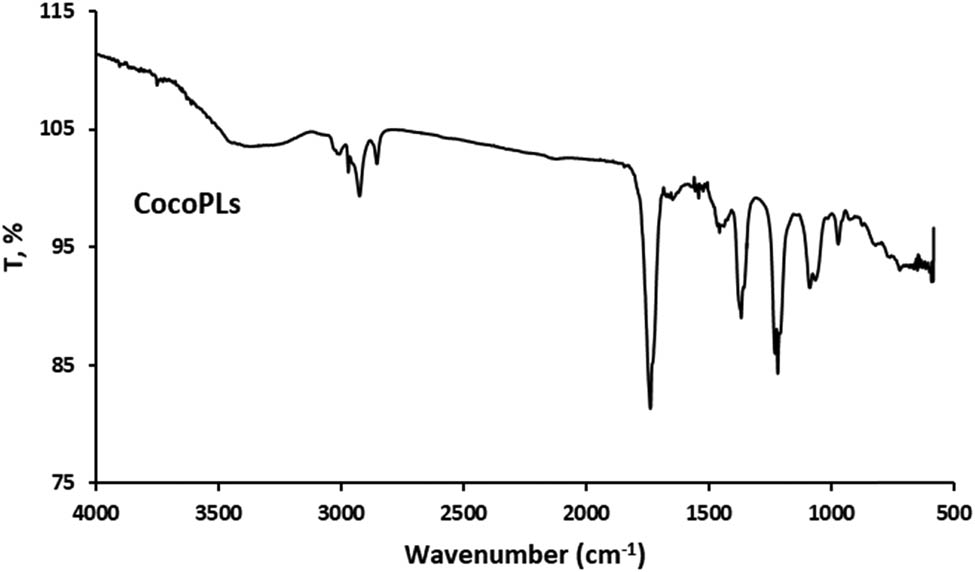

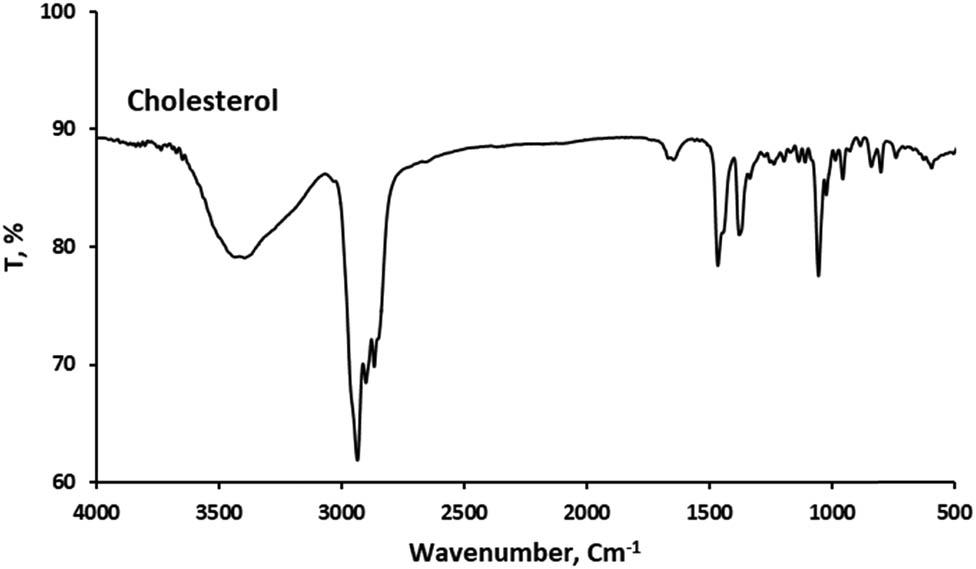

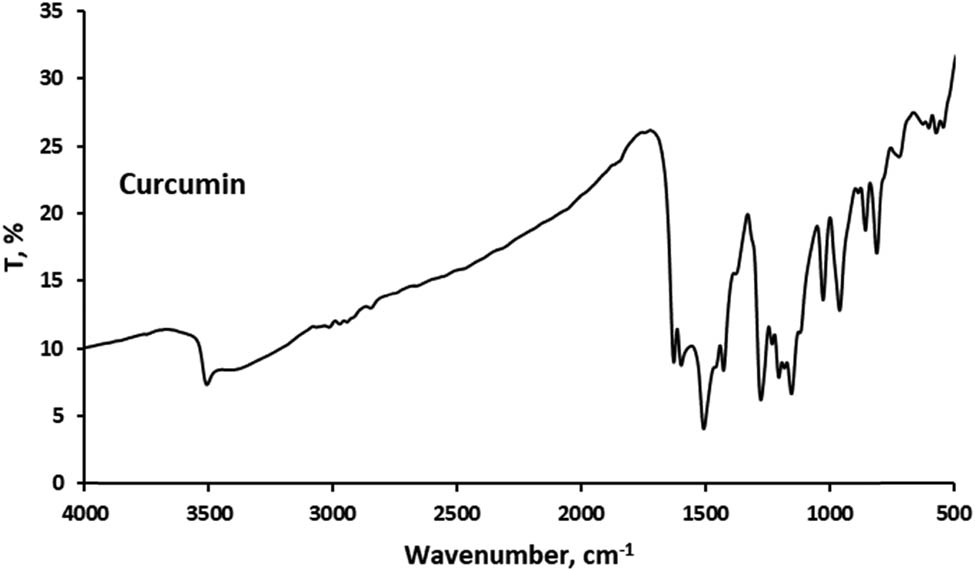

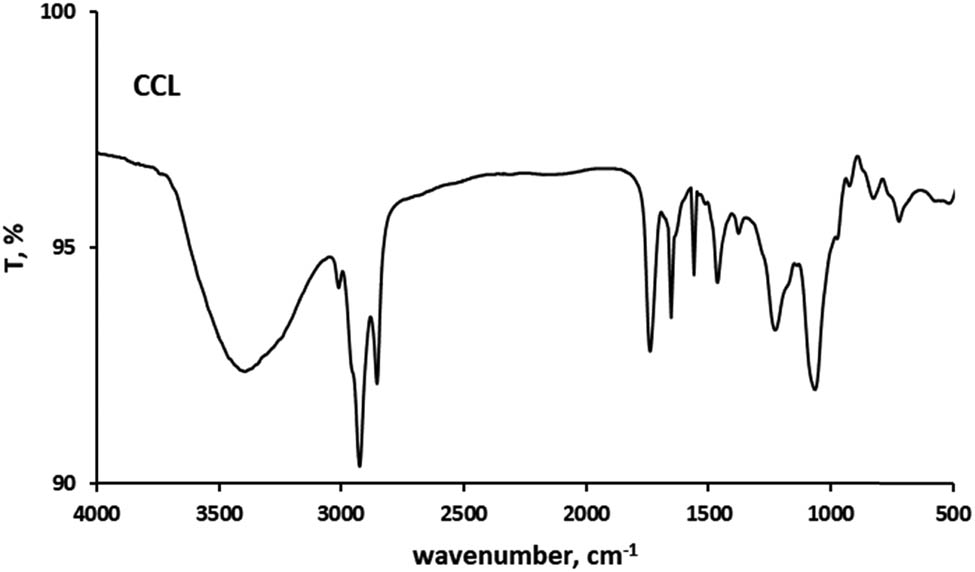

2.6 Functional group analysis by FTIR spectrometry

CocoPLs, cholesterol, curcumin and CCL were analyzed to determine changes and interactions that might occur during encapsulation through changes in the functional groups using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer (FTIR, Perkin Elmer Model Frontier FT-IR, USA), range of 5,500–435 cm−1, resolution 4.0 cm−1, number of scans 3.

2.7 Encapsulation efficiency (

EE

) and loading capacity (

LC

)

The ability of cocoliposome to load curcumin was denoted by encapsulation efficiency (

2.8 Release rate of curcumin

Average release rate (

2.9 DPPH free radical scavenging assay

1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay was conducted following the method by Blois [24]. Briefly, 1 mL of each CCL dispersion was mixed with 3 mL of DPPH solution (40 µg/mL). The mixtures were incubated at room temperature without exposure to light for 30 min. Later, the mixture’s absorbance was analyzed using UV–Vis spectrophotometry at λ

max (516 nm). The radical scavenging activity was calculated as DPPH scavenging activity (

where

2.10 Statistical analysis

Data were collected in duplicate. Statistical analysis was executed with ANOVA. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Results with P value <0.1 were considered statistically significant.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to human or animal use.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Functional group analysis by FTIR spectrometry

Functional group analysis using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to verify the encapsulation of curcumin in the cocoliposome. FTIR can disclose the chemical alterations by generating an infrared absorption spectrum. Figures 1–4 present the FTIR spectra of curcumin, cholesterol, CocoPLs and the CCL. The characteristic peaks for phospholipids were found at ∼1,228 and ∼1,085 cm−1 for PO2− stretching; ∼1,047 cm−1 indicating C–O–P stretching; ∼819 cm−1 denoting P–O stretching; ∼1,738 cm−1 denoting C═O stretching in esters; ∼2,925 and ∼2,854 cm−1 indicating CH2 stretching of acyl chains; ∼2,971 and ∼2,855 cm−1 denoting CH3 stretching of acyl chains; ∼1,457 and ∼1,366 cm−1 signifying CH3 bending and ∼1,598 cm−1 denoting ═C–H stretch [17,22,25]. The major bands for cholesterol molecule were found at several positions as follows: the peaks between 2,800 and 3,000 cm−1 signifying stretching vibrations of CH2 and CH3 groups. The wide and intense band at ∼3,400 cm−1 was assigned to OH stretching. The distinctive strong band at 2,933 cm−1 was assigned to CH2 stretching vibration. The double bond (C═C) in the second ring was shown at 1,667 cm−1. The band at 1,465 cm−1 was assigned to asymmetric stretching vibrations of CH2 as well as CH3 groups. The peak at 1,377 cm−1 was assigned to the CH2 and CH3 bending vibration. The peak at 1,054 cm−1 was assigned to ring deformation of cholesterol. The peak at 839 cm−1 was assigned to the C–C–C stretching. The peaks between 900 and 675 cm−1 were assigned to the C–H out-of-plane bending, which were the distinctive of the aromatic replacement configuration [23]. The spectrum of curcumin displayed a sharp absorption peak at 3,510 cm−1, signifying the existence of the phenolic –OH stretching vibration. The strong peak at 1,628 cm−1 signified primarily fused C═O and C═C groups, and 1,599 cm−1 was attributed to the symmetric aromatic stretching vibration. The sharp peak at 1,508 cm−1 was attributed to C═C vibrations. The sharp peak at 1,455 cm−1 was from the phenolic C–O, while the enolic C–O peak was appeared at 1,278 cm−1. The peak at 1,025 cm−1 was attributed to the asymmetric stretching of C–O–C. The peak at 721 cm−1 was the C–H vibration of aromatic ring [26,27]. The FT-IR spectra of the curcumin, cholesterol and CocoPLs was found to have merged in CCL. All the sharp peaks of curcumin, cholesterol and CocoPLs were observed. However, no observable new characteristic peaks were found in the FTIR spectra of CCL. Therefore, it could be predicted that no chemical reaction occurs in the process of curcumin encapsulation in the cocoliposome. The interactions that occur were thought to be non-covalent interactions.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of coconut phospholipids (CocoPLs).

Fourier transform infrared spectra of cholesterol (Chol).

Fourier transform infrared spectra of curcumin (Cur).

Fourier transform infrared spectra of CCL.

3.2 Encapsulation efficiency

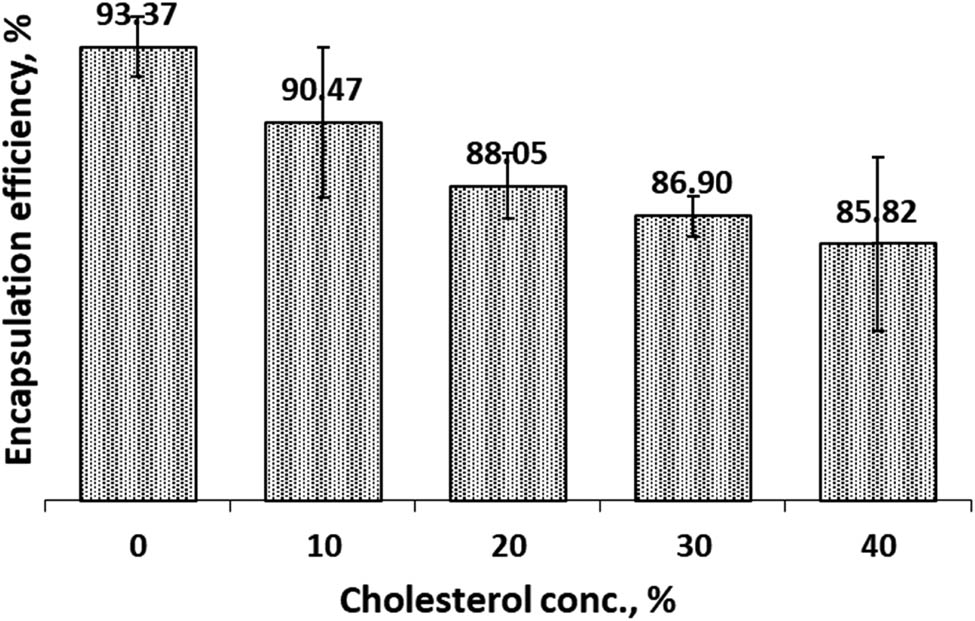

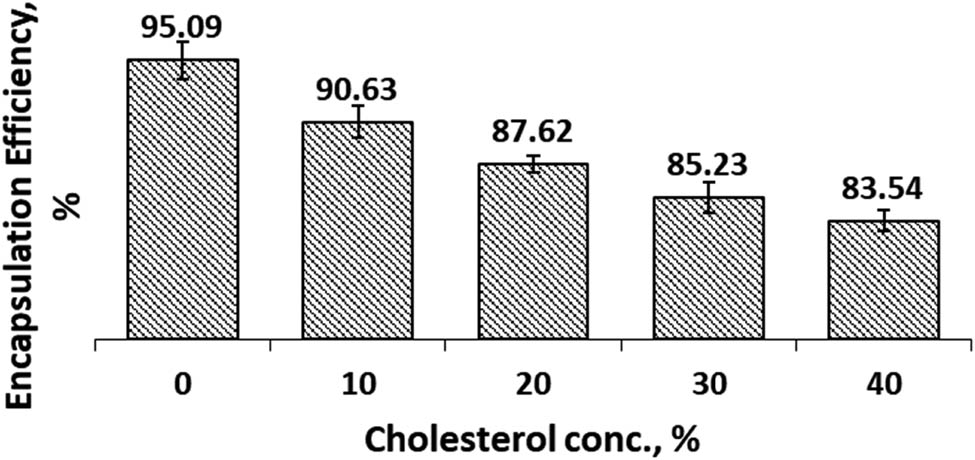

The EE of CCL in both SIF and SGF solutions were presented in Figures 5 and 6.

Encapsulation efficiency of Cur in cocoliposome in SIF solution as a function of cholesterol.

Encapsulation efficiency of Cur in cocoliposome in SGF solution as a function of cholesterol.

In SIF environments, Figure 5, the addition of cholesterol in the cocoliposome composition decreased the efficiency of encapsulation. These data indicated that the composition of cholesterol in the cocoliposome membrane exerted great influence on the encapsulation efficiency. Data showed that the efficiency of encapsulation remains high, 90.47%, when the composition of cholesterol is 10%. The same results were obtained in the SGF milieu, Figure 6, the efficiency of encapsulation decreased with increasing cholesterol concentration in the cocoliposome membrane. The data revealed that in the SGF environment, cholesterol also had a significant effect on the efficiency of the curcumin encapsulation system. The best cholesterol composition to get high EE value in SGF solution was 10% with the EE value around 90.63%. These data specified that cholesterol modified the efficiency of cocoliposome encapsulation against curcumin. The effect of cholesterol was quite small at low concentrations, 10%. Statistical analysis of the data disclosed that EE was significantly affected by cholesterol concentration. However, the encapsulation efficiency in SIF condition was not significantly different from SGF.

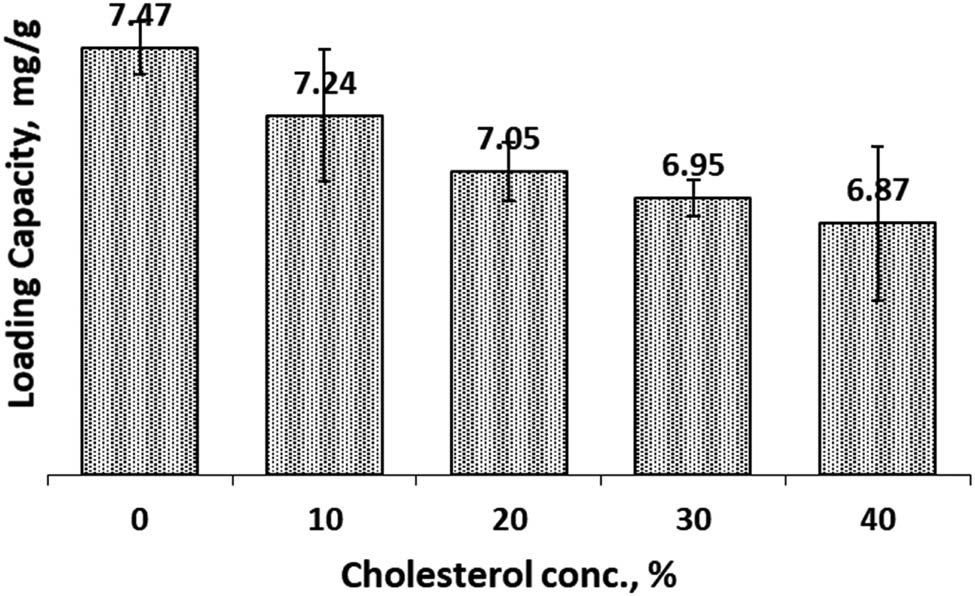

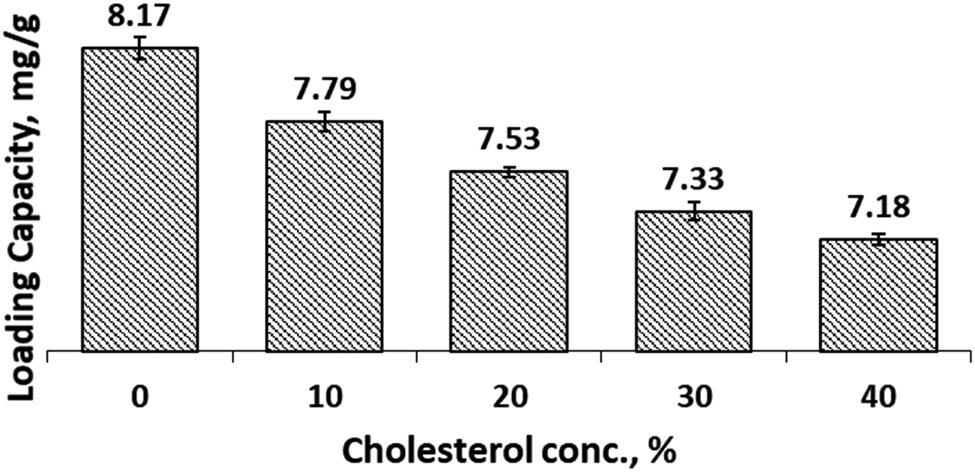

3.3 Loading capacity

The LC calculates the amount of curcumin successfully encapsulated in cocoliposome per unit weight (gram) of CocoPLs in the liposome. It provides an overview of how the preparations can be used practically. The LC of CCL in both SIF and SGF solutions is presented in Figures 7 and 8. Figure 7 presents the LC of curcumin in SIF environment. The LC of curcumin in the cocoliposome preparations without addition of cholesterol was 7.47 mg/g. The data disclosed a decrease in LC value when cholesterol concentration is increased. When the cholesterol concentration is 10%, the LC was still close to the initial value of 7.24 mg/g. Figure 8 described the LC in SGF solution. Similar changes occurred when cholesterol concentration was increased and the LC was decreased. The LC of curcumin in the cocoliposome preparations without the addition of cholesterol was 8.17 mg/g. The LC was still close to the initial value of 7.79 mg/g when the cholesterol concentration is 10%. The information from both the SIF and SGF conditions indicated that cholesterol altered the LC value of curcumin in the cocoliposome preparations. However, the data suggested that the cholesterol concentration of 10% still gave a fairly high LC. The value of LC was affected significantly by cholesterol concentration and environmental conditions (SIF and SGF).

Loading capacity of Cur in cocoliposome in SIF solution as a function of cholesterol.

Loading capacity of Cur in cocoliposome in SGF solution as a function of cholesterol.

3.4 Release rate (RR)

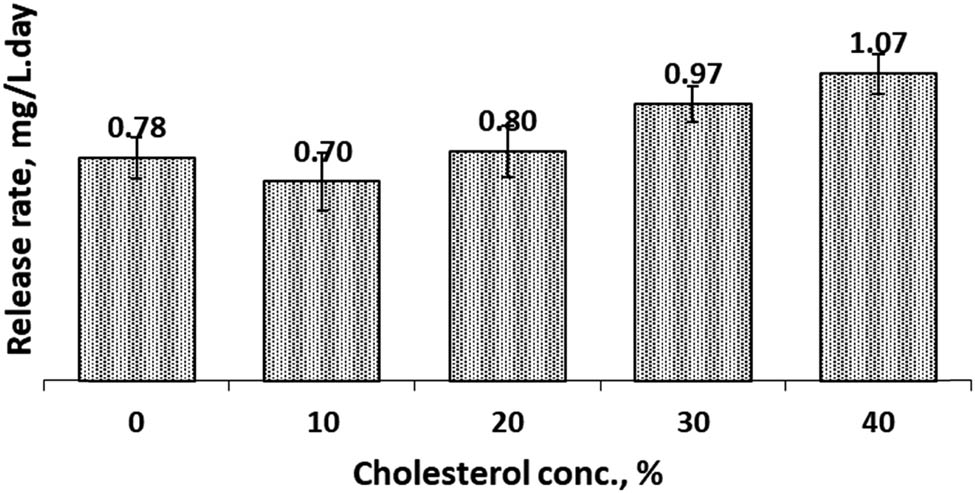

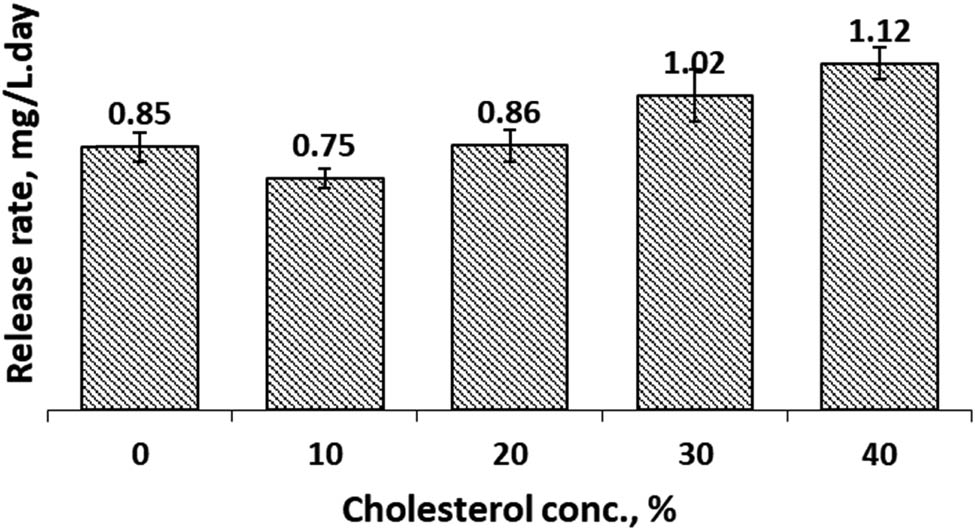

RR of active agent carriers such as liposomes or other forms of carrier is an important feature related to the therapeutic activity of active agents [28]. Therefore, we studied the release rate of curcumin from our prepared CCL. The RR of CCL in both SIF and SGF solutions were presented in Figures 9 and 10. Data presented that in SIF condition, Figure 9, generally the addition of cholesterol increased the rate of release of curcumin. The RR of CCL without cholesterol (non-cholesterol CCL) in the liposome membrane was 0.78 mg/L day. The lowest RR, 0.70 mg/L day, was obtained when the cholesterol concentration was 10%. For higher concentration of cholesterol, the RR increased above the RR of non-cholesterol CCL. The RR in SGF condition, Figure 10, typically ascended with an increase in cholesterol concentration in the cocoliposome membrane. The most promising composition in SGF condition to attain a low release rate was at 10% of cholesterol with the release rate of 0.75 mg/L day. The data revealed that either in SIF or SGF solution, 10% cholesterol concentration would give the lowest RR. The RR was influenced significantly by cholesterol concentration and environmental condition. This discovery was in accordance to the EE and LC data.

Release rate of Cur from cocoliposome in SIF solution as a function of cholesterol.

Release rate of Cur from cocoliposome in SGF solution as a function of cholesterol.

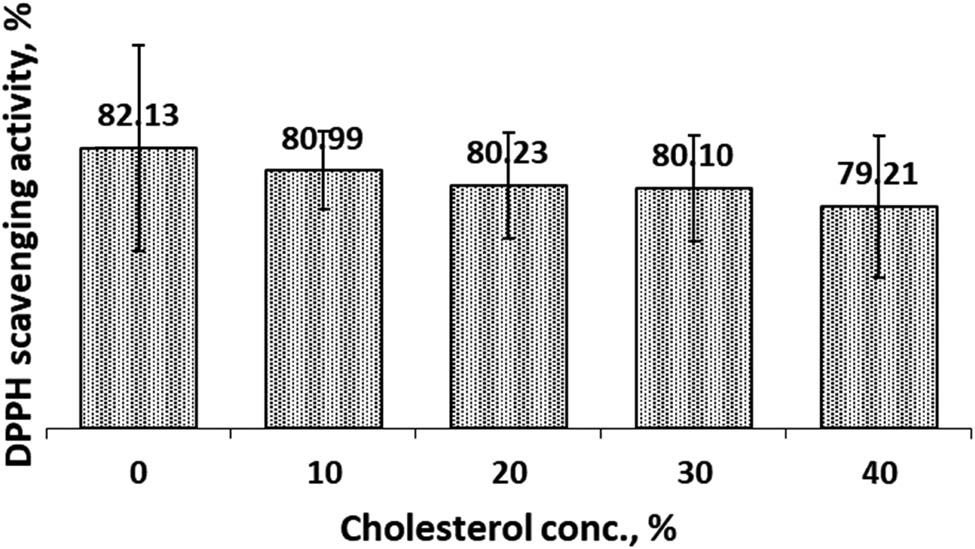

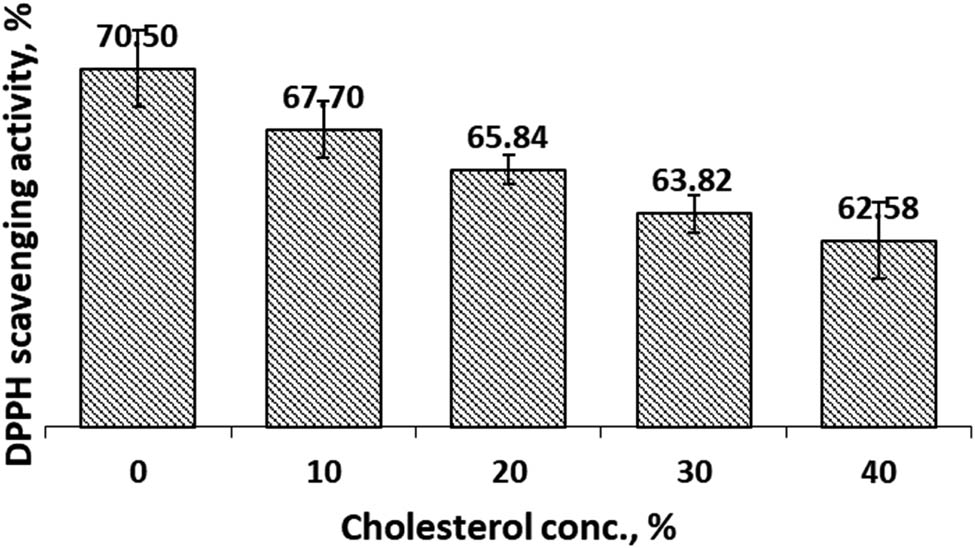

3.5 DPPH scavenging activity assay

The antioxidant activity of encapsulated curcumin was analyzed by DPPH scavenging activity assay. Antioxidant activity will be high if the DPPH scavenging activity is high. DPPH scavenging activity of CCL in both SIF and SGF solutions were presented in Figures 11 and 12. Prior to the analysis, we measured DPPH scavenging activity of CocoPLs. We found that the DPPH scavenging activity was low and insignificant compared with curcumin. Therefore, we deliberated that the DPPH scavenging activity of CCL preparations came from curcumin. DPPH scavenging activity of the preparations in SIF milieu, Figure 11, revealed that increasing cholesterol concentration would reduce the DPPH scavenging activity. In SGF setting, an increase in cholesterol composition also decreased the DPPH scavenging activity, Figure 12. Both graphs exposed that the trend of DPPH scavenging activity was still decreasing when the cholesterol concentration reached 40%. Besides the DPPH scavenging activity in SIF milieu were higher than that in SGF. At cholesterol concentration of 10%, the scavenging activity in SIF and SGF was 80.99 and 67.70%, respectively. The scavenging activity in SGF was significantly affected by the cholesterol concentration. Moreover, the scavenging activity was induced significantly by environmental conditions (SIF and SGF).

DPPH scavenging activity of CCL in SIF solution as a function of cholesterol.

DPPH scavenging activity of CCL in SGF solution as a function of cholesterol.

3.6 Curcumin encapsulation in cocoliposome

3.6.1 Cholesterol effect

As predicted in the FTIR analysis results, it is estimated that the interactions that occur in the curcumin encapsulation in the cocoliposome are non-covalent interactions. The molecular structure of curcumin shows that the curcumin molecule, has two hydrogen bond donor and six hydrogen bond acceptor, with a topological polar surface area of 93.1 Å2 [29]. Therefore, the possible interaction is a hydrogen bond between the curcumin and phospholipid molecules. Curcumin has a large polar surface area, but the polar area is geometrically spread across the length of the molecule so that the position of the curcumin tends to be laterally located inside the liposome membrane close to the polar area of the membrane. The large polar surface area and the number of sites for hydrogen bond formation explain the ease of curcumin to be encapsulated in the liposome membrane. This is manifested in the high EE and LC values for liposome formulations without cholesterol.

Meanwhile, cholesterol has an amphiphilic structure with one hydrogen bond donor and acceptor group. As a result, the presence of cholesterol in liposome formulations will interfere with non-covalent interactions between curcumin and phospholipids. There is competition for the formation of hydrogen bonds with phospholipids between curcumin and cholesterol. The relatively small size of polar portion of the cholesterol and its position at the tip of the molecule boost the chance of cholesterol to form hydrogen bond with phospholipids. The cholesterol affinity on hydrogen bonding formation with phospholipids is higher than curcumin. It is evident from the decrease in EE and LC of curcumin when there is cholesterol in the formulations. The greater the cholesterol concentration, the greater the decrease is. The same rationalizes also justified how cholesterol causes RR to increase when there is cholesterol in the liposomal formulations. In the case of RR, it is also necessary to pay attention to the packing of molecules in the liposome membrane. Similar RRs for formulations with 0 and 20% cholesterol concentrations are thought to be associated with the molecular packing of phospholipid, cholesterol and curcumin molecules in the liposome membrane. The packing of molecules which then sterically affects the diffusion and movement of curcumin in the membrane will ultimately affects the release of curcumin from the membrane as well. Cholesterol at a concentration of 20% is believed to provide a molecular packing and steric effect similar to that of liposome membranes without cholesterol. The data indicated that the liposome formulation to obtain the most optimum EE, LC and RR was the formulation with a cholesterol concentration of 10%.

DPPH scavenging activity of curcumin in liposome preparations is related to the amount of encapsulated curcumin in CCL. It is then represented by the EE and LC values. Data show that DPPH scavenging activity of CCL decreases with increasing cholesterol concentration. Thus, the reduction of DPPH scavenging activity of the CCL preparations is in accordance with the EE and LC data.

3.6.2 Effect pH (SIF and SGF) conditions

Encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome was thought to involve non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bond interactions. The hydrogen bond interactions depend on pH values. Changes of pH affected protonation of phosphate group in phospholipids. Meanwhile in acidic and neutral conditions, curcumin molecules appeared in protonated form where curcumin played as a potent hydrogen donor [30]. However, in basic situations where the enolate form of the heptadienone chains prevailed, curcumin operated instead as an electron donor. These properties were thought to cause discrepancies in the value of the encapsulation parameters and scavenging activity under acidic (SGF, pH = 1.2) and neutral (SIF, pH = 7.4). The scavenging activity at 10% cholesterol composition was 82.13 and 67.70% in SIF and SGF condition, respectively. In view of the scavenging activity, SIF condition was more suitable for CCL formulation. This result is in line with the poor solubility of curcumin under acidic conditions [31].

4 Conclusion

Encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome was affected by cholesterol and pH conditions. Under both the SIF and SGF conditions, when the cholesterol concentration increased then the encapsulation efficiency, loading capacity and DPPH scavenging activity decreased, but the release rate increased. The formulation to obtain the optimum encapsulation parameters value was at a cholesterol concentration of 10%. The DPPH free radical scavenging activity at 10% cholesterol composition of CCL was 82.13 and 67.70% in SIF and SGF surroundings, respectively. The CCL formulation thrived better under SIF conditions for free radical scavenging activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tatik Widiarih for her advice in statistical interpretation of the data.

-

Funding source: This research was supported by the Minister of Research and Technology/BRIN Republic Indonesia through PDUPT Research Scheme 2020. Grant No. 257-49/UN7.6.1/PP/2020.

-

Author contributions: Muhammad Fuad Al Khafiz performed the experiments and wrote the original draft. Khairul Anam, and Parsaoran Siahaan analyzed data and resources. Linda Suyati analyzed data and carried out project administration. Dwi Hudiyanti was lead investigator, research design, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and finalization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Stanić Z. Curcumin, a compound from natural sources, a true scientific challenge – a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2017;72:1–12. 10.1007/s11130-016-0590-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Shome S, Talukdar AD, Choudhury MD, Bhattacharya MK, Upadhyaya H. Curcumin as potential therapeutic natural product: a nanobiotechnological perspective. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2016;68:1481–500. 10.1111/jphp.12611.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Carvalho D, de M, Takeuchi KP, Geraldine RM, de Moura CJ, Torres MCL. Production, solubility and antioxidant activity of curcumin nanosuspension. Food Sci Technol. 2015;35:115–9. 10.1590/1678-457X.6515.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Perrone D, Ardito F, Giannatempo G, Dioguardi M, Troiano G, Lo Russo L, et al. Biological and therapeutic activities, and anticancer properties of curcumin (review). Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:1615–23. 10.3892/etm.2015.2749.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Siviero A, Gallo E, Maggini V, Gori L, Mugelli A, Firenzuoli F, et al. Curcumin, a golden spice with a low bioavailability. J Herb Med. 2015;5:57–70. 10.1016/j.hermed.2015.03.001.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Prasad S, Tyagi AK, Aggarwal BB. Recent developments in delivery, bioavailability, absorption and metabolism of curcumin: The golden pigment from golden spice. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:2–18. 10.4143/crt.2014.46.1.2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Lamichhane N, Udayakumar TS, D’Souza WD, Simone CB, Raghavan SR, Polf J, et al. Liposomes: clinical applications and potential for image-guided drug delivery. Molecules. 2018;23:288–305. 10.3390/molecules23020288.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Lee MK. Liposomes for enhanced bioavailability of water-insoluble drugs: in vivo evidence and recent approaches. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:264. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12030264.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Le NTT, Cao VDu, Nguyen TNQ, Le TTH, Tran TT, Thi TTH. Soy lecithin-derived liposomal delivery systems: surface modification and current applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4706–33. 10.3390/ijms20194706.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Hasan M, Belhaj N, Benachour H, Barberi-Heyob M, Kahn CJFJF, Jabbari E, et al. Liposome encapsulation of curcumin: physico-chemical characterizations and effects on MCF7 cancer cell proliferation. Int J Pharm. 2014;461:519–28. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.12.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Hudiyanti D, Triana D, Siahaan P. Studi Pendahuluan tentang Enkapsulasi Vitamin C dalam Liposom Kelapa (Cocos nucifera L.). J Kim Sains Dan Apl. 2017;20:5. 10.14710/jksa.20.1.5-8.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Müller LK, Landfester K. Natural liposomes and synthetic polymeric structures for biomedical applications. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;468:411–8. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.088.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] van Hoogevest P, Wendel A. The use of natural and synthetic phospholipids as pharmaceutical excipients. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2014;116:1088–107. 10.1002/ejlt.201400219.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Kondratowicz A, Weiss M, Juzwa W, Majchrzycki Ł, Lewandowicz G. Characteristics of liposomes derived from egg yolk. Open Chem. 2019;17:763–78. 10.1515/chem-2019-0070.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Hudiyanti D, Raharjo TJ, Narsito, Noegrohati S. Investigation on the morphology and properties of aggregate structures of natural phospholipids in aqueous system using cryo-tem. Indones J Chem. 2012;12:54–61. 10.22146/ijc.21372.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Hudiyanti D, Jayanti M, Al-Khafiz MF, Anam K, Fuad Al-Khafiz M, Anam K. A study of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) phosphatidylcholine species. Orient J Chem. 2018;34:2963–8. 10.13005/ojc/340636.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hudiyanti D, Kamila N, Kusuma Wardani F, Anam K. Coconut phospholipid species: isolation, characterization and application as drug delivery system. Nano- Micro-Encapsulation – Tech Appl [working title]. IntechOpen. 2021:1–17. 10.5772/intechopen.88176.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hudiyanti D, Aminah S, Hikmahwati Y, Siahaan P. Cholesterol implications on coconut liposomes encapsulation of beta-carotene and vitamin C. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. vol. 509, IOP Publishing; 2019. p. 012037. 10.1088/1757-899X/509/1/012037.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Hudiyanti D, Al-Khafiz MF, Anam K. Encapsulation of cinnamic acid and galangal extracts in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) liposomes. J Phys Conf Ser. vol. 1442, Institute of Physics Publishing; 2020. p. 12056. 10.1088/1742-6596/1442/1/012056.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kaddah S, Khreich N, Kaddah F, Charcosset C, Greige-Gerges H. Cholesterol modulates the liposome membrane fluidity and permeability for a hydrophilic molecule. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;113:40–8. 10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Briuglia M-LL, Rotella C, McFarlane A, Lamprou DA. Influence of cholesterol on liposome stability and on in vitro drug release. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2015;5:231–42. 10.1007/s13346-015-0220-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Shapaval V, Brandenburg J, Blomqvist J, Tafintseva V, Passoth V, Sandgren M, et al. Biochemical profiling, prediction of total lipid content and fatty acid profile in oleaginous yeasts by FTIR spectroscopy. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:1–12. 10.1186/s13068-019-1481-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Gupta U, Singh V, Kumar V, Khajuria Y. Spectroscopic studies of cholesterol: fourier transform infra-red and vibrational frequency analysis. Mater Focus. 2014;3:211–7. 10.1166/mat.2014.1161.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–200. 10.1038/1811199a0.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Hudiyanti D, Fuad Al Khafiz M, Anam K, Al Khafiz MF, Anam K. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) lipids: extraction and characterization. Orient J Chem. 2018;34:1136–40. 10.13005/ojc/340268.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zhao Z, Xie M, Li Y, Chen A, Li G, Zhang J, et al. Formation of curcumin nanoparticles via solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical CO2. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:3171–81. 10.2147/IJN.S80434.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Feng R, Song Z, Zhai G. Preparation and in vivo pharmacokinetics of curcumin-loaded PCL-PEG-PCL triblock copolymeric nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:4089–98. 10.2147/IJN.S33607.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Gébleux R, Wulhfard S, Casi G, Neri D. Antibody format and drug release rate determine the therapeutic activity of noninternalizing antibody-drug conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2606–12. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0480.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] National Center for Biotechnology Information. Curcumin | IC21H20O6 – PubChem. PubChem Database. 2020. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Curcumin#section=Computed-Properties (accessed August 4, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lee W-H, Loo C-Y, Bebawy M, Luk F, Mason R, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin and its derivatives: their application in neuropharmacology and neuroscience in the 21st century. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11:338–78. 10.2174/1570159x11311040002.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Rahimi HR, Nedaeinia R, Sepehri Shamloo A, Nikdoust S, Kazemi Oskuee R. Novel delivery system for natural products: nano-curcumin formulations. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6:383–98. 10.22038/ajp.2016.6187.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Dwi Hudiyanti et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation