Abstract

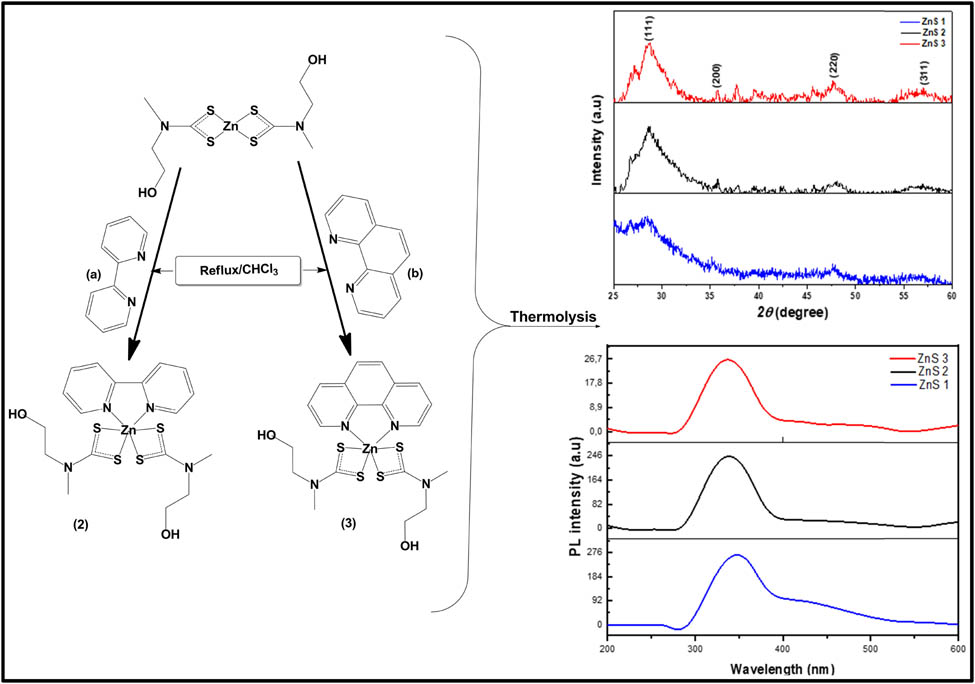

Zinc sulphide nanoparticles represented as ZnS1, ZnS2 and ZnS3 have been prepared from Zn(ii) N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate (1) complex and its 2,2′-bipyridine (2) and 1,10′-phenanthroline (3) adducts, respectively. Both the parent complex (1) and the adducts (2) and (3) were characterised by spectroscopic techniques and elemental analysis. In the solid state, the structures of complexes (1) and (2) were established using single-crystal X-ray analysis. Complex (1) possessed a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry about the zinc centre, whilst forming a dimer via bidentate bridging coordination between two opposite dithiocarbamate motifs. On the other hand, complex (2) formed a trigonal prismatic geometry about the Zn centre with a ZnS4N2 chromophore. The decomposition of the complexes in hexadecylamine afforded spherical-shaped ZnS nanoparticles of the cubic sphalerite crystal phase. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs showed that the average particles size of ZnS1, ZnS2 and ZnS3 were 2.63, 5.27 and 6.52 nm, respectively. In the optical study, the estimated bandgap energies were found in the range between 4.34 and 4.08 eV, which indicated a blue shift when compared with the bandgap energy of bulk ZnS.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Group 12 complexes of dithiocarbamate have been vastly studied due to their usefulness in areas such as analytical chemistry and agriculture, as well as their use as precursor compounds for material synthesis [1]. Zinc(ii) dithiocarbamate is prominent amongst this class of complexes and has found relevance in many industrial and biological processes [2,3]. Both the centrosymmetric dimeric [4] and the monomeric structures, such as those derived from N-isobutyl-N-propyl and N-cyclohexyl-N-methyl dithiocarbamate [5,6], have been reported for Zinc(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes. This variation is indicative of the influence of the nature of organic substituent present in the dithiocarbamate backbone on the observed structure of the complexes in a solid state [4].

Transition metal chalcogenides are important semiconductor materials that have continued to draw attention due to their outstanding properties and wide range of applications in diverse areas [7]. Specifically, zinc sulphide (ZnS) is a II–VI semiconductor that has continued to gain more attention owing to industrial, biological and agricultural applications [8]. The nanoparticles show significant quantum confinement effects that influence their optical and electrical properties [9]. Hence, its application in photovoltaics, photonic/optoelectronic devices, sensors and catalysis [10,11]. It is more chemically stable when compared with ZnSe, which in turn favours its preferred usage as host material [12]. Its polymorphic nature implies that it exists in two crystalline forms of wurtzite and sphalerite (zinc blend) [12]. However, the coordination geometry between S and Zn remains tetrahedral in nature. The difference, notwithstanding, is that the wurtzite phase has a hexagonal form whereas the sphalerite phase possesses a stable cubic form [12]. The bandgap energy found in both polymorphs is 3.91 and 3.54 for the wurtzite and zinc blend, respectively [12]. ZnS has been prepared by different methods in other to achieve specific structures and properties [9], and different chemical and physical methods have been reported for the synthesis of ZnS [13,14]. Earlier, it has been mostly prepared using precipitation or coprecipitation methods [15,16]. However, in recent times, the single-source precursor methods have been widely used and Zn(ii) complexes have been utilised as precursor compounds for the preparation of ZnS nanoparticles [17,18]. The thermal decomposition of compounds bearing S-donor groups has proven to be a desirable route to achieving ZnS nanoparticles with good crystallinity, tuneable dimensions and narrow size distributions [9]. The ease of synthesis of metal sulphide (MS) nanoparticles from metal dithiocarbamate complexes as precursor compounds has made them desirable starting materials in nanomaterial synthesis.

Herein, we present the synthesis, structural and optical properties of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate) (1) and its 2,2′-bipyridine (2) and 1,10′-phenanthrolin (3) adducts.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and physical measurements

All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich chemicals company and were used without any further purifications. These include N-methyl-N-ethanolamine, carbon disulphide, ammonium hydroxide, zinc acetate dihydrate, chloroform, 2,2′-bipyridine, 1, 10′-phenanthroline, trioctylphosphine (TOP), hexadecylamine, methanol and toluene. The percentage elemental composition (C, H, N and S) of the complexes was estimated using an Elementar analyser, Vario EL Cube. Infrared spectra, obtained at room temperature, were carried out on Alpha Bruker FTIR spectrophotometer in the wavenumber range of 4,000–500 cm−1. The Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer for 1H and 13C NMR analysis in chloroform solution (CDCl3) solution. Powder X-ray diffractogram (XRD) of the nanoparticles was recorded on a Bruker D8 Advanced XRD machine, equipped with a proportional counter using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 A, nickel filter). Samples were added on a flat steel sample holder and scanned from 10 to 80°C. The diffraction peaks at several values were matched with other recorded standards in JCPDS. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectra of the nanoparticles were recorded using a Perkin-Elmer λ20 UV-vis spectrophotometer. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the nanoparticles were measured using Perkin Elmer LS 45 Fluorimeter.

2.1.1 Single crystal X-ray determination

Single crystal X-ray diffraction analyses were performed at 200 K using a Bruker Kappa Apex II diffractometer with monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). APEX2 [19] was used for data collection and SAINT [19] for cell refinement and data reduction. The structure was solved using SHELXT-2014 [20] and refined by least-squares procedures using SHELXL-2016 [21] with SHELXLE [22] as a graphical interface. Data were corrected for absorption effects using the numerical method implemented in SADABS [19]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Carbon-bound H atoms were placed in calculated positions and were included in the refinement in the riding model approximation, with U iso(H) set to 1.2U eq(C). The H atoms of the methyl groups were allowed to rotate with a fixed angle around the C–C bond to best fit the experimental electron density (HFIX 137 in the SHELX program suite [21]) with U iso(H) set to 1.5U eq(C). The methyl groups of (1) show rotational disorder with two positions rotated from each other by 60 degrees. The H atoms of the methyl groups were allowed to rotate with a fixed angle around the C–C bond to best fit the experimental electron density (HFIX 123 in the SHELX program [21]). The H atoms of the hydroxyl groups were allowed to rotate with a fixed angle around the C–O bond to best fit the experimental electron density (HFIX 147 in the SHELX program [21]), with U iso(H) set to 1.5U eq(O). The structure of (2) was refined as a 2-component twin with a BASF parameter of 0.25.

2.2 Synthesis of ammonium-N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate

The synthesis of this ligand followed an already reported synthetic route [23]. Briefly, an equimolar amount of N-methyl-N-ethanolamine (0.8 mL, 0.001 mol) and carbon disulphide (0.6 mL, 0.001 mol) was stirred for 30 min in a round bottom flask placed in an ice bath. To this mixture, ammonium hydroxide (3 mL, 0.001 mol) was added and stirred further for 2 h to obtain the ammonium salt of N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate.

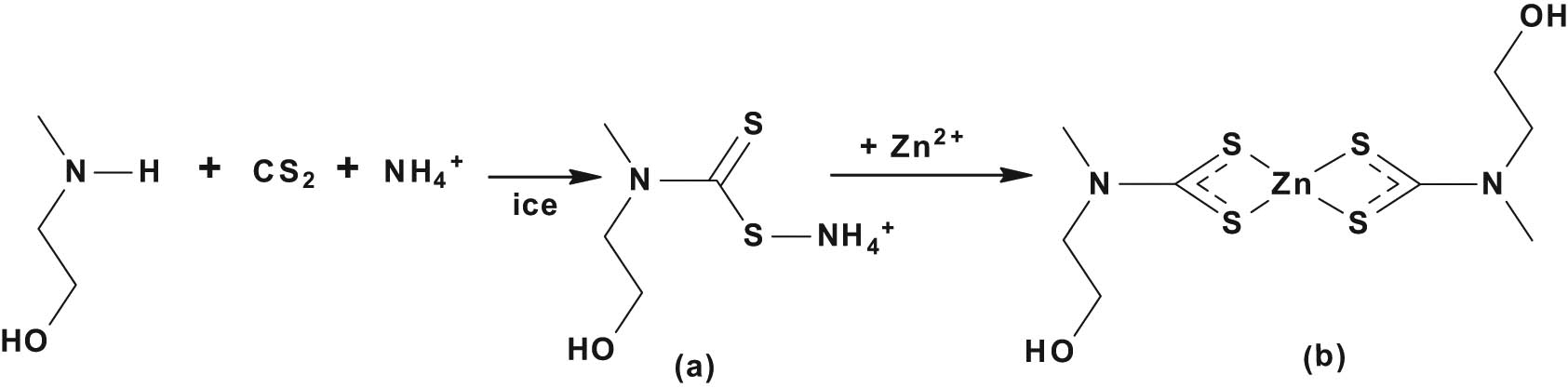

2.3 Synthesis of Zn(ii) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate) (1)

A freshly prepared ammonium N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate (1.8 g, 0.005 mol) was dissolved in 20 mL water, followed by the addition of 20 mL aqueous solution of zinc acetate dihydrate (1.2 g, 0.005 mol) with continuous stirring for an hour. The obtained white precipitate was filtered, rinsed with a large volume of water and dried [23], as shown in Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (a) ammonium N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate and (b) Zn(ii) bis-(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate).

(1): Yield, 1.25 g, 78%; M. Pt, 112–113°C; selected IR, (cm−1): 1,492 ν(C═N), 1,387 ν(C2–N), 977 ν(C–S), 2,930 ν(–C–H), 3,287 ν(O–H), 1,619 δ(O–H), 503 (Zn–S); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 4.85 (s, 2H, NCH2CH2OH), 3.89 (t, 4H, NCH2CH 2OH), 3.51 (s, 6H, NCH 3), 3.35 (t, 4H, NCH 2CH2OH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 206.2 (–NCS2), 66.0 (NCH2 CH2OH), 60.2 (NCH2 CH2OH), 44.9 (NCH3); anal. calc. for C8H16N2S4 (365.87): C, 26.26; H, 4.41; N, 7.66; S, 35.06. Found: C, 26.12; H, 4.22; N, 7.99; S, 35.02%.

2.4 Synthesis of 2,2′-bipyridine (2) and 1, 10′-phenanthroline (3) adducts of Zn(ii) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate)

The procedure followed an already reported method [24]. A hot 20 mL chloroform solution of the Lewis base (0.001 mol) (either 2,2′-bipyridine (2) or 1,10′-phenanthroline (3)) was added to an equimolar amount of hot 20 mL chloroform solution of Zn(ii) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate) (1) (0.37 g, 0.001 mol) while stirring. The resulting yellow solution was refluxed for 1 h, then allowed to cool to room temperature and filtered. The yellow filtrate from the solution was kept for crystallisation by slow evaporation. Scheme 2 presents the synthetic route for the formation of the adducts.

Synthesis of (a) Zn(ii) (2,2′-bipyridyl) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate) (2) and (b) Zn(ii) (1,10-phenanthroline) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanoldithiocarbamate) (3).

(2): Yield, 0.98 g, 69%; M. Pt, 163–165°C; selected IR, (cm−1): 1,475 ν(C═N), 1,367 ν(C2–N), 977 ν(C–S), 2,920 ν(–C–H), 3,377 ν(O–H), 1,597 δ(O–H), 506 (Zn–S); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 8.93–7.25 (m, 8H, bpy), 5.35 (s, 2H, NCH2CH2OH), 4.07 (t, 4H, NCH2CH 2OH), 3.93 (t, 4H, NCH 2CH2OH), 3.52 (s, 6H, NCH 3); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 204.2 (–NCS2), 163.5, 136.2, 129.4, 128.9, (bpy), 54.1 (NCH2 CH2OH), 32.0 (NCH2CH2OH), 25.9 (NCH3); anal. calc. for C18H24N4S4 (522.05): C, 41.41; H, 4.63; N, 10.73; S, 24.57. Found: C, 41.32; H, 4.61; N, 11.10; S, 24.22%.

(3): Yield, 1.05 g, 74 %; M. Pt, 172–173°C; Selected IR, (cm−1): 1,481 ν(C═N), 1,376 ν(C2–N), 981 ν(C–S), 2,918 ν(–C–H), 3,327 ν(O–H), 1,580 δ(O–H), 497 (Zn–S); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 9.57–7.20 (m, 8H, phen), 5.34 (s, 2H, NCH2CH2OH), 4.25 (t, 4H, NCH2CH 2OH), 3.69 (t, 4H, 4H, NCH 2CH2OH), 3.16 (s, 6H, NCH 3); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 204.5 (–NCS2), 127.3, 129.2, 132.5, 159.8 (phen), 53.7 (NCH2 CH2OH), 26.0 (NCH3), 31.2 (NCH2CH2OH); anal. calc. for C20H24N4S4 (546.0702): C, 43.99; H, 4.43; N, 10.26; S, 23.49. Found: C, 44.12; H, 4.31; N, 4.55; S, 23.02%.

2.5 Synthesis of hexadecylamine (HDA) capped ZnS nanoparticles

The nanoparticles were prepared with slight modifications of an established solvothermal procedure, using a single-source precursor [25,26]. About 0.3 g of the complexes was dispersed in 5 mL of trioctylphosphine (TOP) and injected into a solution of 3 g hot hexadecylamine at 160°C, with vigorous stirring under nitrogen. The reaction temperature was maintained at 160°C while aliquots were taken at 15, 30 and 45 min, to monitor the growth of nanoparticles. After 60 min, the heating was stopped and the solution was allowed to cool to 70°C, then excess methanol was added to precipitate the nanoparticles. The solid was separated by centrifugation and re-dispersed in toluene. The centrifugation and isolation procedure were repeated three times for the purification of nanoparticles. The synthesised nanoparticles were represented as ZnS1, ZnS2 and ZnS3, to denote the particles synthesised from (1), (2) and (3), respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Description of crystal structures of (1) and (2)

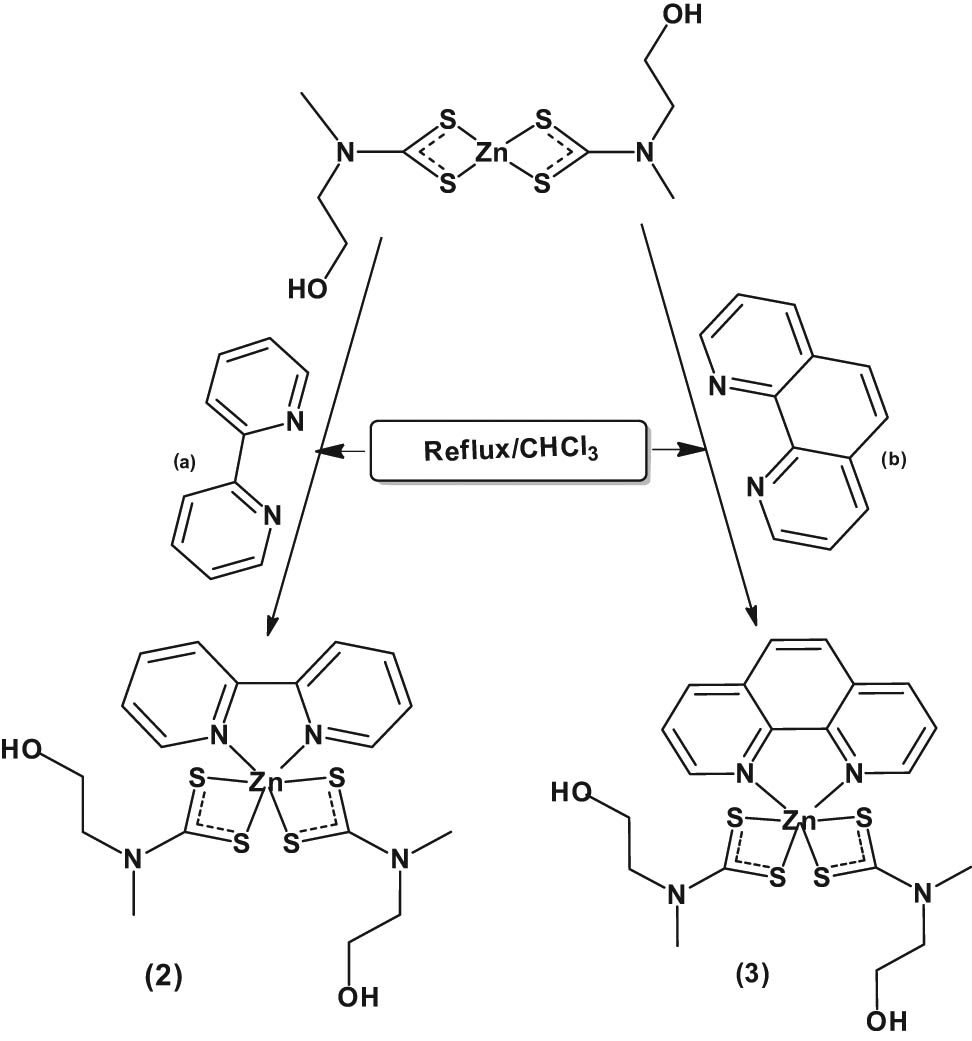

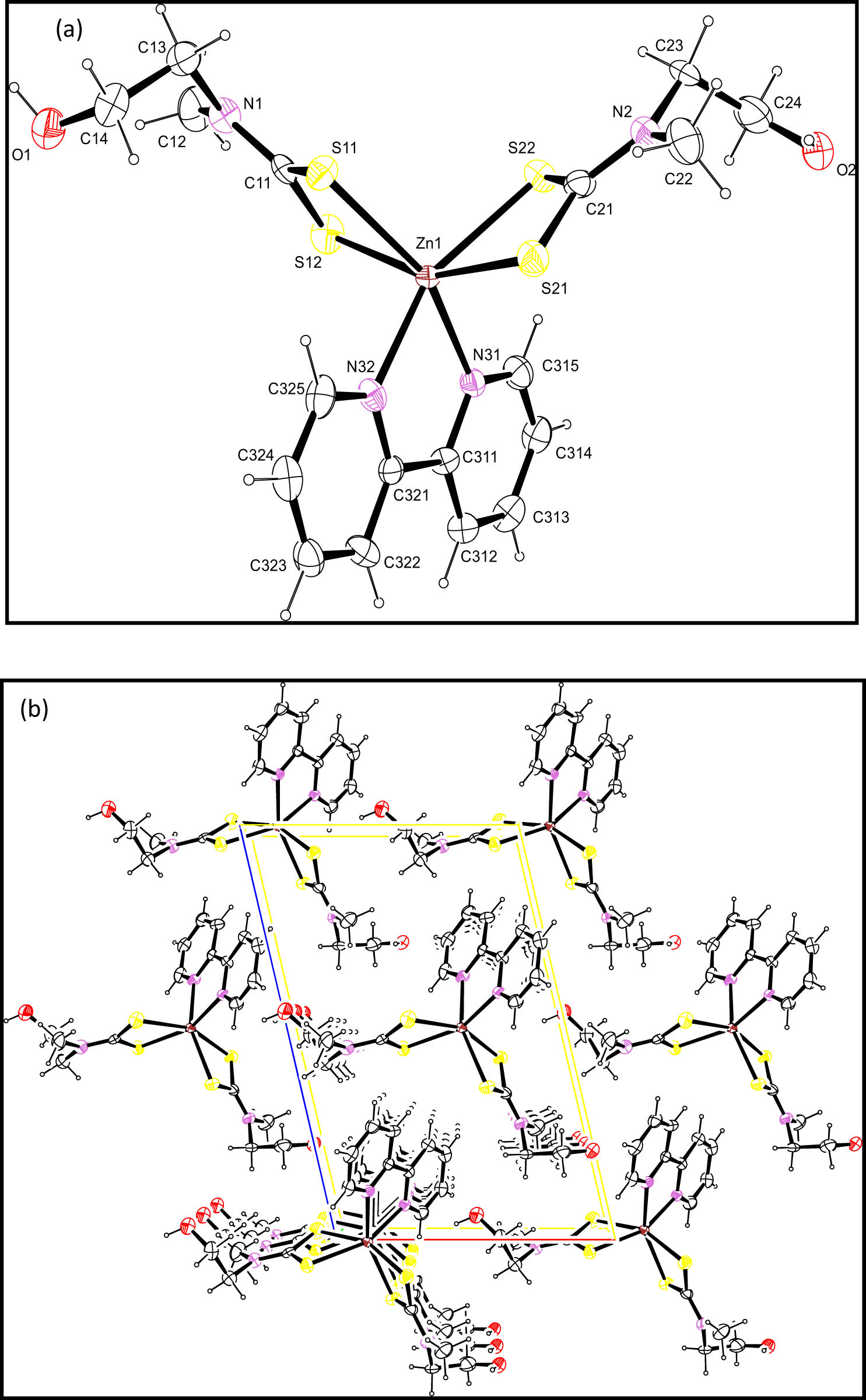

The molecular structures of complexes (1) and (2) were established by single-crystal X-ray diffractometry. Crystallographic parameters for (1) and (2) were obtained and the selected bond angles and distances have been summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The complexes reveal a chelating k 2 -S,S′ binding fashion of dithiocarbamates, which is the most common structural motif [27]. The ORTEP diagrams of complexes (1) and (2) are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Both complexes are monoclinic with P21/n and Pn space groups for complexes (1) and (2), respectively.

Summary of crystal data and structure refinement

| Complex | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C16H32N4O4S8Zn2 | C18H24N4O2S4Zn |

| Formula weight | 731.72 | 522.04 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.13 × 0.15 × 0.58 | 0.07 × 0.40 × 0.54 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Temperature (K) | 200 | 200 |

| Crystal habit | Rod, colourless | Plate, clear yellow |

| Space group | P21/n | Pn |

| a (Å) | 8.4252(2) | 10.5377(6) |

| b (Å) | 22.1700(7) | 6.7318(3) |

| c (Å) | 8.4854(3) | 16.0866(9) |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 |

| β (˚) | 113.496(1) | 103.132(2) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 90 |

| V [Å**3] | 1453.55(8) | 1111.30(10) |

| Z | 2 | 2 |

| Dcalc (Mg m−3) | 1.672 | 1.560 |

| F(000) | 752.0 | 540 |

| Dataset | −11:10; −29:29; −11:11 | −14:14; −8:8; −21:21 |

| μ(MoKa) (/mm) | 2.255 | 1.503 |

| R(int) | 0.024 | 0.0426 |

| Observed reflections I > 2σ(I) | 3,160 | 5,011 |

| Nref, Npar | 3631,156 | 5391,267 |

| Final R, wR2, S | 0.0217, 0.0516, 1.05 | 0.0637, 0.1716, 1.10 |

| Max. residual density [e/Å3] | 0.26 | 2.26 |

| Min. residual density [e/Å3] | −0.34 | −0.76 |

| θ range (˚) | 1.8–28.3 | 2.1–28.3 |

Selected bond lengths and bond angles

| (1) | (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths (Å) | Bond lengths (Å) | ||

| Zn1–S11 | 2.3332(5) | Zn1–S11 | 2.516(3) |

| Zn1–S12 | 2.4488(6) | Zn1–S12 | 2.577(3) |

| Zn1–S21 | 2.3391(4) | Zn1–S21 | 2.523(3) |

| Zn1–S22 | 2.8608(6) | Zn1–S22 | 2.559(3) |

| Zn1–S22i | 2.3659(5) | Zn1–N31 | 2.172(8) |

| S22–Zni | 2.3659(5) | Zn1–N32 | 2.197(8) |

| S11–C11 | 1.7350(16) | S11–C11 | 1.713(12) |

| S12–C11 | 1.7125(17) | S12–C11 | 1.720(12) |

| S21–C21 | 1.7138(14) | S21–C21 | 1.705(10) |

| S22–C21 | 1.7491(15) | S22–C21 | 1.734(11) |

| N1–C11 | 1.327(2) | N1–C11 | 1.340(15) |

| N2–C21 | 1.3215(19) | N2–C21 | 1.440(16) |

| Bond angle (°) | Bond angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S11–Zn1–S12 | 76.19(2) | S11–Zn1–S12 | 70.38(9) |

| S11–Zn1–S22 | 94.76(2) | S11–Zn1–S21 | 94.24(10) |

| S11–Zn1–S22i | 123.49(2) | S21–Zn1–S22 | 71.00(9) |

| S21–Zn1–S22 | 68.85(2) | S12–Zn1–S22 | 96.61(10) |

| S21–Zn1–S22i | 108.45(2) | S11–Zn1–N32 | 94.1(2) |

| S12–Zn1–S21 | 102.58(2) | S12–Zn1–N32 | 104.0(2) |

| S22–Zn1–S22i | 93.45(2) | S21–Zn1–N31 | 105.1(2) |

| Zn1–S11–C11 | 84.50(6) | S22–Zn1–N31 | 94.0(2) |

| Zn1–S12–C11 | 81.42(5) | N31–Zn1–N32 | 74.7(3) |

| Zn1–S21–C21 | 95.14(5) | Zn1–S11–C11 | 87.0(4) |

| Zn1–S22–C21 | 77.79(5) | Zn1–S12–C11 | 84.9(4) |

| Zn1–S22–Zn1i | 86.55(2) | Zn1–S21–C21 | 86.1(4) |

| C11–N1–C12 | 121.15(16) | Zn1–S22–C21 | 84.3(3) |

| C11–N1–C13 | 122.03(14) | C11–N1–C12 | 122.9(10) |

| C12–N1–C13 | 116.79(16) | C11–N1–C13 | 122.7(9) |

| C21–N1–C23 | 123.81(13) | C12–N1–C13 | 114.4(10) |

| C22–N1–C23 | 115.27(12) | C21–N1–C22 | 119.8(9) |

| C21–N1–C22 | 120.91(13) | C21–N1–C23 | 123.2(10) |

| S12–C11–N1 | 121.21(12) | C22–N1–C23 | 117.0(9) |

| S11–C11–N1 | 121.00(13) | ||

| S21–C21–N2 | 120.36(11) | ||

| S22–C21–N2 | 121.36(11) | ||

| S11–C11–S12 | 117.79(9) | ||

| S21–C21–S22 | 118.18(8) | ||

Symmetry elements: (i) 1 − x, 1 − y, 2 − z.

![Figure 1

(a) The molecular structure and (b) packing diagram of [ZnL1

2] with displacement ellipsoids drawn to 50% probability level. Symmetry elements: (i) 1 − x, 1 − y, 2 − z.](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2021-0094/asset/graphic/j_chem-2021-0094_fig_001.jpg)

(a) The molecular structure and (b) packing diagram of [ZnL1 2] with displacement ellipsoids drawn to 50% probability level. Symmetry elements: (i) 1 − x, 1 − y, 2 − z.

(a) The molecular structure and (b) packing diagram viewed normal to (010) of (2) with displacement ellipsoids drawn to 50% probability level.

Complex (1) is a centrosymmetric dimeric structure in which an asymmetric unit of one contains two half binuclear molecules, such that the centre of inversion of each unit is inclined towards another as shown in Figure 1. A typical feature of dithiocarbamate compounds is the planarity [28] of the MS2CNC2 unit, and all these seven atoms were found approximately in a plane, which resulted in the stereochemical rigidity of the dithiocarbamate [29]. Owing to the presence of the two chelating and bridging dithiocarbamate ligands, each independent complex contains a core central eight-membered ring of ZnSCS2, which is stabilised by a trans-annular Zn–S22 bond that is longer by approximately 0.5 Å than the other Zn–S bonds. This feature is in agreement with those reported already earlier [30,31,32]. In each mononuclear moiety of (1), the dithiocarbamate ligands featured an S,S′-anisobidentate coordination, in which each of them contains a short Zn–S bonds (Zn1–S11/Zn1–S21) and a longer Zn–S bonds (Zn1–S12/Zn1–S22), Table 2 [33]. Although there are some conformational differences amongst each binuclear moiety of (1) complex as regards the terminal residues, the Zn2S8 molecular cores are superimposable. The longer Zn–S bond interactions and the acute chelate angles seemed to be the major contributors to the distortion of the 4 + 1 coordination geometry. Therefore, the geometry around the Zn atoms was distorted trigonal bipyramidal with about 35% along the Berry pseudorotation and S22i (i: 1 − x, 1 − y, 2 − z) as the pivot atom [34]. Tau-Descriptor for the 5-coordination is 0.57 [35].

Furthermore, in complex (1), the bond parameters of the terminal dithiocarbamate attached to the central Zn atom; S11–Zn1–S12 [76.19(2)°] and S21–Zn1–S22 [68.85(2)°] deviate significantly from 90o, which consequently results in the distortion of the geometry about the Zn centre due to the small bite angle. In addition, other S–Zn–S bonds angles in (1) were found at 102.58(2)° and 94.76(2)° for S12–Zn–S21 and S11–Zn–S22, respectively. It is expected that atoms at the equatorial position should be close to 120o. However, due to steric hindrances, these angles were smaller for S12–Zn–S21 and S1–Zn–S4 in (1). Furthermore, in complex (1), the chelating and bridging behaviour of the dithiocarbamate ligands were observed due to dimerisation through the coordination of two Zn atoms and S atoms, similar to earlier reported cadmium dithiocarbamate [27]. Despite the varying bond angles around the eight-membered ring of [ZnSCS]2, a stable boat and chair conformation was observed in this complex. This was in agreement with Tiekink and Zukerman–Schpector report [4,36]. In the chelating ring, the C–S bond lengths were between those of double and single bonds (Table 2) contrary to a typical C–S bond length of 1.81Å, which appeared higher than the average length found in this complex [1.72Å] [33]. This indicated a double bond character and further signified the charge delocalisation within the CS2Zn chelate ring [27]. Both intra and intermolecular C–H/S and O⋯HO interactions existed, as shown in Table 3. One of the ethanolic groups in the dithiocarbamate moiety was disordered on each monomer unit of the complex.

Geometric details of hydrogen bonding (°) and (Å)

| Interactions | D–H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D–H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | ||||

| O1–H1··O2 | 0.8400 | 1.9500 | 2.7614(18) | 163.00 |

| O2–H2··O1 | 0.8400 | 1.8800 | 2.7130(18) | 171.00 |

| C12–H12D··S12 | 0.9800 | 2.4200 | 2.981(2) | 116.00 |

| C12–H12F··S12 | 0.9800 | 2.6900 | 3.6398(16) | 164.00 |

| C13–H13B··S11 | 0.9900 | 2.6700 | 3.0079(18) | 100.00 |

| C14–H14A··S11 | 0.9900 | 2.8600 | 3.4256(18) | 117.00 |

| C14–H14B··S12 | 0.9900 | 2.8500 | 3.7715(19) | 156.00 |

| C22–H22D··S21 | 0.9800 | 2.3800 | 2.9529(16) | 116.00 |

| C23–H23B··S22 | 0.9900 | 2.5800 | 3.0654(16) | 110.00 |

| (2) | ||||

| O2–H2··N2 | 0.8400 | 2.5700 | 2.893(15) | 104.00 |

| C12–H12C··S12 | 0.9800 | 2.5100 | 3.058(15) | 115.00 |

| C13–H13B··S11 | 0.9900 | 2.6100 | 2.986(13) | 102.00 |

| C22–H22C··S21 | 0.9800 | 2.5800 | 2.969(13) | 104.00 |

| C23–H23B··S22 | 0.9900 | 2.5900 | 3.026(12) | 106.00 |

| C314–H314··O1 | 0.9500 | 2.5700 | 3.520(15) | 176.00 |

| C315–H315··S21 | 0.9500 | 2.7900 | 3.497(11) | 132.00 |

| C315–H315··S22 | 0.9500 | 2.8200 | 3.481(11) | 128.00 |

| C325–H325··S12 | 0.9500 | 2.7900 | 3.582(10) | 3.582(10) |

In complex (2), the Zn atom was bonded to the dithiocarbamate ligands through the two sulphur atoms and to the 2,2′-bipyridine through two nitrogen atoms of the Lewis base, to form a ZnS4N2 group in both complexes. Owing to the closeness of Zn to the bipyridine molecule in [ZnL2 (bpy)] complex, an appreciable difference in the bond lengths between the Zn and S bonds was observed like those in complex (1). The occurrence of shorter bond lengths (which are longer than the shorter Zn–S bond in (1)) was observed for the Zn1–S11 and Zn1–S21, while those of longer length, Zn1–S12 and Zn1–S22, were lesser than those found in (1). This gave a trigonal prism geometry around the Zn atom similar to the previous report [27]. The atoms S11, S12 and N32, and S21, S22 and N31 define the bases of the prism with the Zn atom situated 1.351(4) and 1.323(5) Å from the prism bases, respectively. The bite angles observed in each of the dithiocarbamate groups in (2): S11–Zn1–S12 [70.38(9)°] and S21–Zn1–S22 [71.00(9)°] were comparable to the values found for other bipyridine adducts of dithiocarbamate [27]. The bite angle of the bipyridine molecule in the complexes was 74.7(3)° and was slightly larger than the observed angle in bipyridine adducts of similar N-alkyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamate complexes containing cadmium atoms [37]. The intra- and intermolecular C–H/S and O⋯HO interactions existed, as shown in Table 3. Due to the closeness of the Zn to the bipyridine molecule, an appreciable difference in the bond lengths between the Zn–S bonds was observed. Both complexes have two molecules per unit cell as shown in the packing diagram in Figures 1b and 2b.

3.2 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy of the complexes

In the 1H NMR spectra of the precursor complex and the adducts, the protons of the methyl group attached to the electronegative nitrogen atom from the ligand moiety resonated as a singlet in the range 3.52–3.16 ppm. This was somewhat higher than expected for a free methyl proton due to its attachment to an electronegative atom [23]. Signals of methylene protons from the ethanolic group attached to both N- and O-ends of the chain were found in the region between 4.25 and 3.51 ppm in all the synthesised complexes. These signals were detected somewhat downfield than expected due to the deshielding effect of the electronegative atoms. Furthermore, the signals due to the proton of the −OH group in both the parent complex and adducts were found in the region between 5.35 and 4.85 ppm [23]. The protons of the bipyridine and the phenanthroline groups appeared in the aromatic region around 8.93–7.25 and 9.57–7.20 ppm, respectively [27,38]. The observed chemical shift with higher frequency in the adduct, bearing the phenanthroline moiety, could be ascribed to the higher number of aromatic rings compared to those of bipyridine.

The 13C NMR spectra of the complexes showed a significant peak due to the quaternary carbons [18] of NCS2 at 206.2, 204.2 and 204.5 ppm for complexes (1), (2) and (3), respectively. The upfield shift in the carbon signal of the adducts in comparison to the parent complex (1) has been attributed to the delocalisation of electron density in the NCS2Zn moiety and the electron cloud withdrawing resonance effect of the rings in the bipyridine and phenanthroline moiety upon coordination to the zinc atom [27,38,39]. The presence of this signal could also suggest the complexation between the metal atom and the dithiocarbamate ligand [38]. The aromatic carbon from the N-donor ligands of bipyridine and phenanthroline was found to resonate in the frequency range of 163.5–128.9 and 159.8–127.3 ppm, respectively [40]. The observed chemical shift of the aromatic carbon peaks in the bipyridine adducts towards a low field region could be attributed to the higher electron-donating tendency of the nitrogen atoms of bipyridine compared to those of the phenanthroline due to the extra ring in the phenanthroline molecule. The signal of the α-carbon in the ethyl moiety bearing the −OH group, of both the parent and the adducts, was observed around 60.3–31.2 ppm, while the β-carbon appeared in the range 66.1–53.7 ppm. These were in agreement with previous reports on similar ligands [41]. The lower signal in the α-carbon compared to the β-carbon could be ascribed to the deshielding effect due to the more electronegative oxygen on the β-carbon compared to the nitrogen atom on the α-carbon [41]. Furthermore, the carbon of the methyl group attached to the N-atom in the dithiocarbamate backbone in both the parent and adducts resonated at 44.9 ppm and around 26.0 ppm, respectively. In the adducts, the upfield movement of the C atoms of the dithiocarbamate backbones, N–CH3 and N–CH2CH2OH, could be attributed to the electron cloud withdrawing resonance effect of the phenyl groups in N-donor ligands attached to the metal centre [27].

3.3 FTIR spectroscopic studies of the complexes

The important bands in the infrared spectra of the prepared dithiocarbamate complexes were found in three regions: 1,060–940 cm−1 v(C–S), 1,580–1,450 cm−1 v(C═N) and 455–250 cm−1 v(M–S) [8]. In the parent complex (1), the thioureide ν(C═N) band occurred at 1,492 cm−1. However, a shift to lower wavelength was observed in the adducts at 1,475 and 1,481 cm−1 for complexes (2) and (3), respectively. The lowering of the vibrational frequency of the thioureide bands in the adducts compared to the parent complex has been ascribed to the increase in coordination number from four to six, which occurred upon adduct formation [42]. Hence, the change in geometry affected the degree of interaction that occurred between the dithiocarbamate ligand and the metal ion [42]. Furthermore, the presence of a single unsplit band in the parent complex and the adduct complexes, in the region between 977–981 cm−1, assigned to the C–S group, suggested the formation of a bidentate mode of bonding between the dithiocarbamate ligand and the central metal ion [43]. The bands due to the ν(–C–H) of the alkyl groups were observed in the region of 2,918–2,971 cm−1 [23]. The O–H stretching and bending vibrations were observed in the region of 3,287–3,377 and 1,580–1,619 cm−1, respectively, in all the complexes. The peak corresponding to M–S stretching vibration was found in the range 497–506 cm−1 [23].

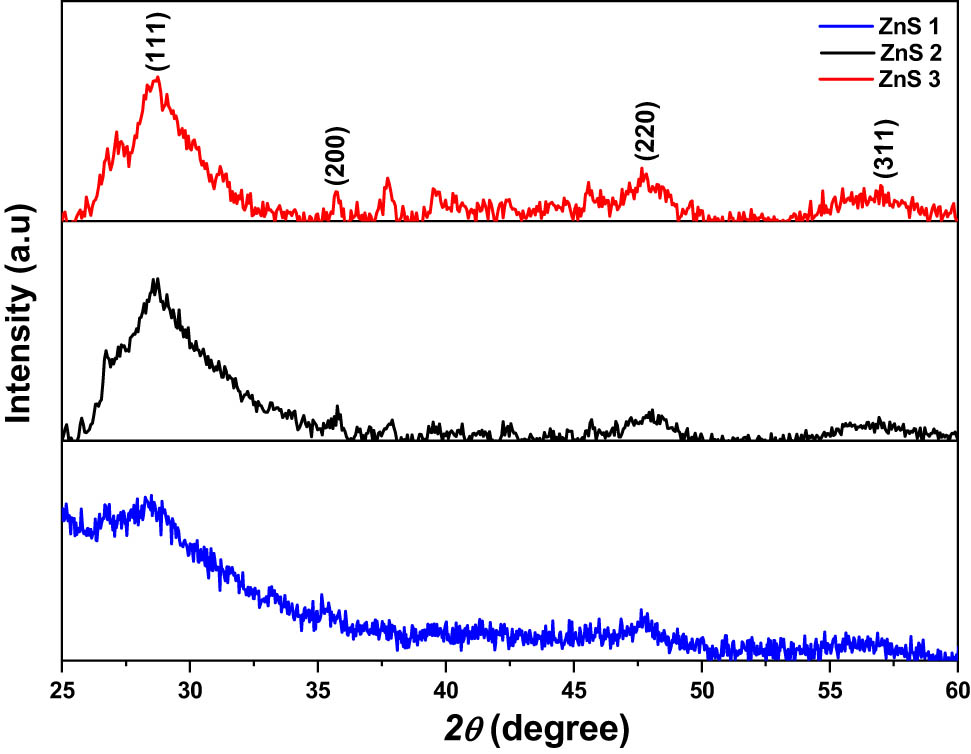

3.4 X-ray diffraction analysis of the nanoparticles

The as-prepared ZnS nanoparticles were characterised by powder X-ray diffraction, and the patterns obtained are presented in Figure 3. In all the samples, diffraction patterns observed correspond to the (1 1 1), (2 2 0) and (3 1 1) planes of cubic (sphalerite) phase of ZnS nanoparticles, which agrees with the standard JCPDS ID: 00-005-0566. The sphalerite phase is well-known to be the more thermodynamically stable form of ZnS at room temperature [9] The observed XRD peaks in each of the nanoparticles were found to be relatively broad, indicating the nano-sized nature of the samples. Other unidentified peaks in the XRD pattern may be due to the compound used as the capping agent.

XRD pattern ZnS1, ZnS2 and ZnS3 nanoparticles obtained from (1), (2) and (3), respectively, as precursor complexes.

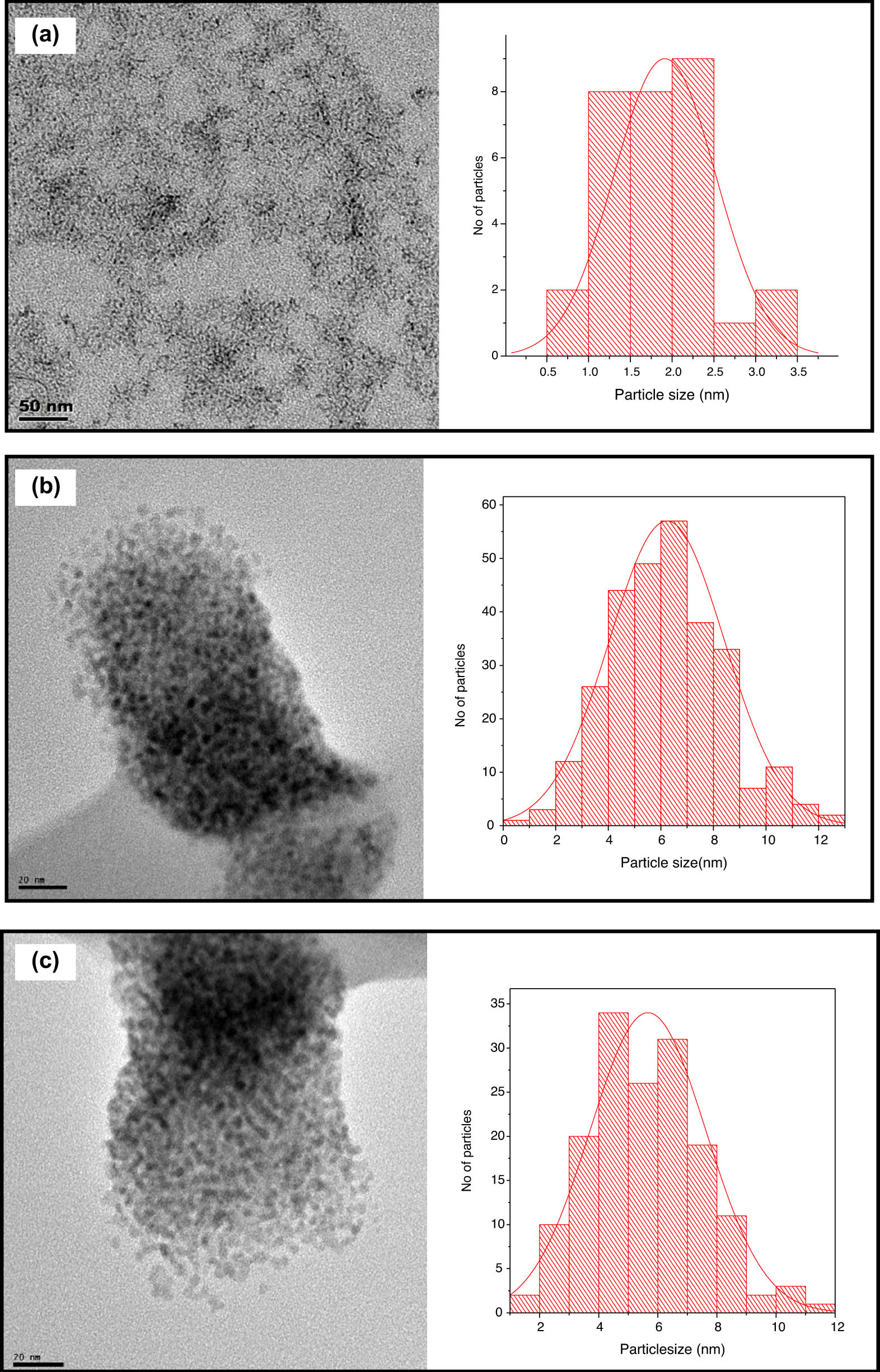

3.5 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies

The TEM micrographs showing the morphologies and sizes of the ZnS nanoparticles are shown in Figure 4(a)–(c) along with their particle size distribution histogram, which was estimated using ImageJ software. The nanoparticles obtained from the parent complex (1), showed rice-shaped morphology, with a mean size of 2.63 nm. The morphology of the nanoparticles obtained from complex (2), represented as ZnS2, showed spherical morphology with a mean size of 5.27 nm. The nanoparticles obtained from complex (3) showed similar spherical morphology with a relatively larger particle mean size (6.52 nm) compared to ZnS1 and ZnS2. These observed differences in nanoparticles’ shape and size have been attributed to the change in the decomposition profile due to the introduction of a Lewis base into the structure of the precursor compounds, thereby altering the functional groups in the compound [25].

TEM micrographs of (a) ZnS1, (b) ZnS2 and (c) ZnS3, with their respective particle size distribution histogram.

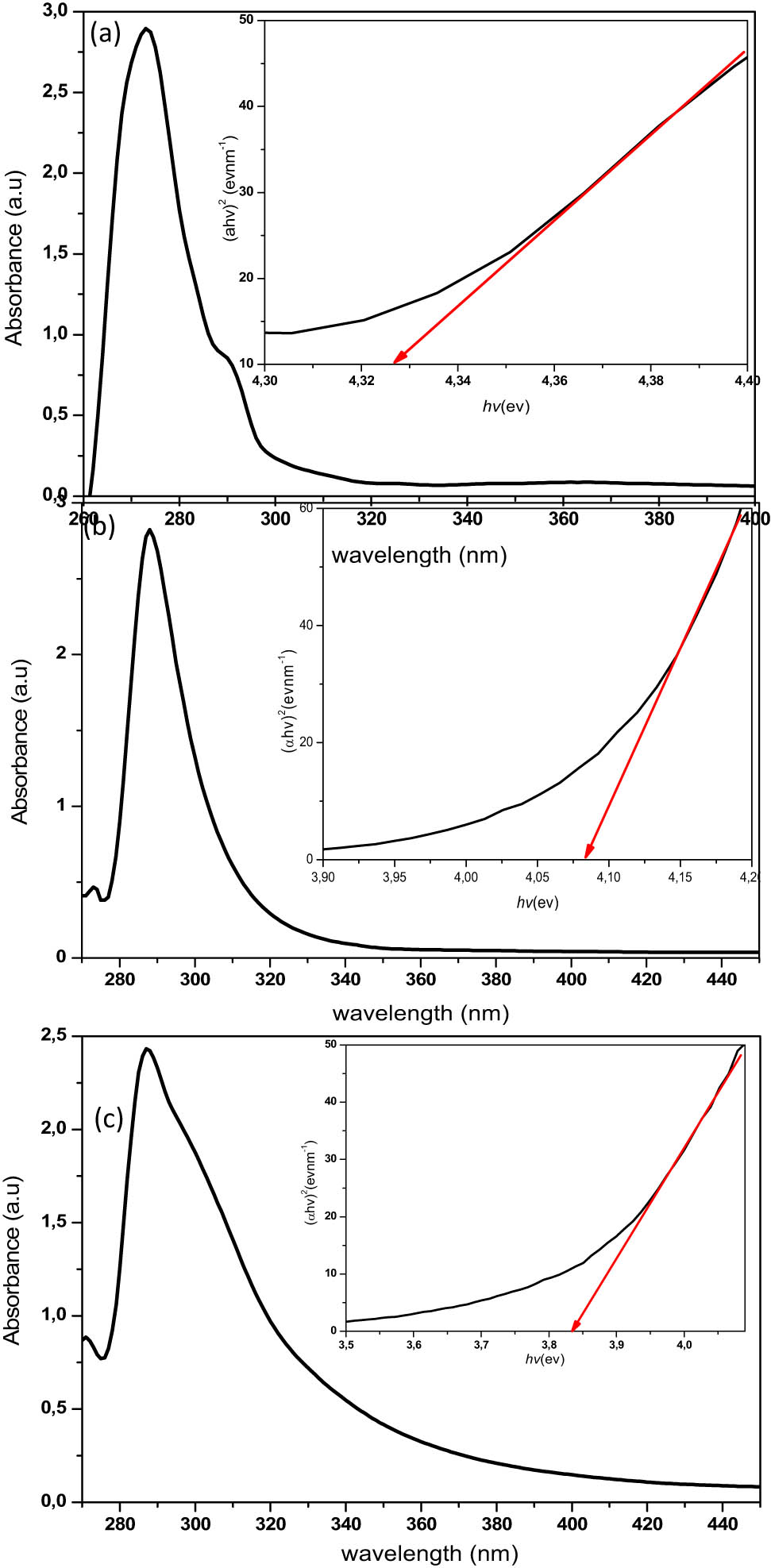

3.6 Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopic study

The photo-absorption properties of the synthesised ZnS nanoparticles were studied using UV-vis spectroscopy, and the obtained spectra are presented in Figures 5a–c. All the synthesised nanoparticles showed the photo-absorption property in the UV light region around 220–420 nm range. The spectra exhibited properties that were indicative of light absorption due to the band-gap transition [44]. The optical bandgap of the nanoparticles was calculated according to Tauc’s relation (equation (1)) [44,45], and the plots are presented as insets in the UV-spectra of Figure 5a–c.

where A is a constant, α is the absorption coefficient, hv is the photon energy, E g is the optical bandgap and n = ½ (indirect transition) or n = 2 (in indirect transition). The bandgap can be obtained by extrapolating the linear portion of the plot (αE)2 vs E to α = 0. The optical parameters obtained from the absorption spectra are presented in Table 4. The bandgap values of all the ZnS nanoparticles from different precursor compounds showed higher bandgap energy than the bulk value (3.68 eV) [44]. This blue shift has been ascribed to the quantum confinement effect and is dependent on both the size and morphologies of the synthesised nanoparticles [44].

Absorption spectra of (a) ZnS1, (b) ZnS2 and (c) ZnS3, and their respective Tauc plots (inset).

Summary of optical spectra data from the UV-vis spectra

| Nanoparticles | Bandgap (eV) | Band edge (nm) | Size (nm) | Absorption peak (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnS1 | 4.34 | 286 | 2.42 | 275 |

| ZnS2 | 4.09 | 303 | 2.88 | 289 |

| ZnS3 | 4.08 | 304 | 2.92 | 289 |

The introduction of the Lewis bases into the parent compound showed a significant effect on the optical properties of the nanoparticles obtained. Table 4 presents the sizes and bandgap energies of the nanoparticles. An increase in the size of the nanoparticles was observed upon the introduction of the Lewis base, which seemed to also increase with an increase in the number of rings in the Lewis bases. This affected the bandgap energy, which showed a reduction since there is an inverse proportionality between the size of nanoparticles and bandgap.

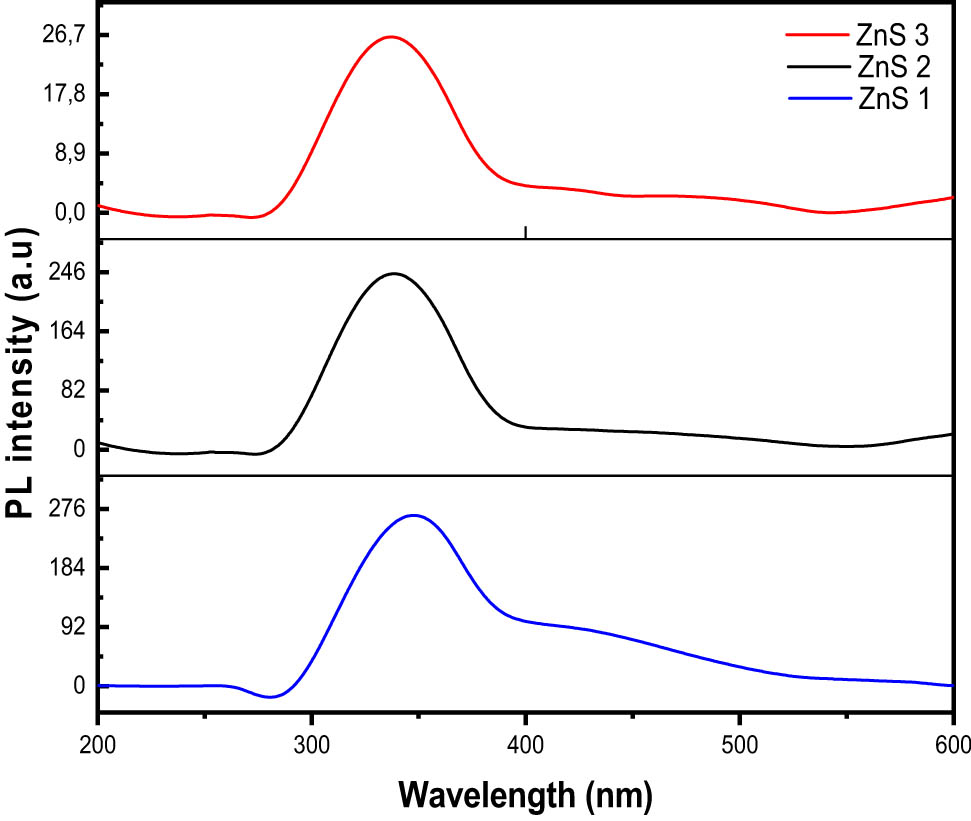

3.7 Photoluminescence spectra

The Photoluminescence spectra of the synthesised ZnS nanoparticles, at an excitation wavelength of 250 nm, are shown in Figure 6. The emission peaks were found in the range 336–340 nm. These emission wavelengths contributed to near band edge emission and may originate from the recombination of the free excitons of ZnS within the nanosize regime [46]. In all the spectra, band energy of about 4.9 eV was observed which resulted in a blue shift when compared to the bandgap energy of bulk ZnS (3.68 eV). The broad nature of the spectra may be due to the large particle size distribution, as observed in the TEM micrographs. A weak emission peak was observed in the spectra of ZnS3 around 490 nm. This emission peak has been ascribed to the defect states or interstitial impurities, which are possibly present at the surface of the ZnS nanoparticles [47,48]. Generally, the fluorescence mechanism proceeds by the absorption of the photon which has comparable energy with the bandgap energy of the semiconductor material, imitating an electron–hole pair as shown in Figure 7 [49]. This energy becomes thermalised within a short time, such that the energy separation between the hole and electron becomes approximately equal to the energy of the gap, leading to the radiative recombination of the electron–hole pair, which consequently gives rise to the emission of photons (luminescence). Therefore, the bang gap energies of the nanomaterial are a rough reflection of the peak positions [49].

Photoluminescence spectra of ZnS nanoparticles.

![Figure 7

Photoluminescence mechanism in semiconductors material [50].](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2021-0094/asset/graphic/j_chem-2021-0094_fig_007.jpg)

Photoluminescence mechanism in semiconductors material [50].

4 Conclusion

ZnS nanoparticles were successfully prepared from the thermolysis of Zn(ii) bis(N-methyl-N-ethanol dithiocarbamate) and its 2,2′-bipyridyl and 1,10′-phenanthroline adducts. The Zn(ii) complex and its respective adducts contained Zn atom coordinated to the dithiocarbamate group in an S,S′-bidentate fashion. The as-prepared ZnS nanoparticles gave spherical-shaped morphology with cubic sphalerite phase, which showed size increment with an increase in the bulkiness of the precursor complexes. The optical property of the nanoparticles showed a blue shift relative to the bandgap energy of bulk ZnS (3.68 eV).

Supplementary data

CCDC 1872719 and 1872720 for complex (1) and (2) respectively contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this dissertation. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge Dr. Innocent Shuro of the Laboratory for Electron Microscopy (LEM) for the morphological studies of the nanoparticles using transition electron microscopy (TEM).

-

Funding information: Financial support from the National Research Foundation and the North-West University, South Africa, are greatly appreciated.

-

Author contributions: D.C.O. – conceptualisation, investigation, writing – review and editing; J.O.A. – formal analysis, writing – review and editing; R.T.P. – methodology, investigation; F.F.B. – methodology, investigation, E.H. – software.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Hogarth G. Transition metal dithiocarbamates: 1978–2003. Prog Inorg Chem. 2005;53:71–561.10.1002/0471725587.ch2Search in Google Scholar

[2] Nieuwenhuizen PJ, Ehlers AW, Haasnoot JG, Janse SR, Reedijk J, Baerends EJ. The mechanism of Zinc(ii)-dithiocarbamate-accelerated vulcanization uncovered; theoretical and experimental evidence. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:163–8.10.1021/ja982217nSearch in Google Scholar

[3] Yilmaz VT, Yazıcılar TK, Cesur H, Ozkanca R, Maras FZ. Metal complexes of phenylpiperazine‐based dithiocarbamate ligands. synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic, thermal, and antimicrobial activity studies. Synth React Inorg Met Chem. 2003;33:589–605.10.1081/SIM-120020326Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sathiyaraj E, Perumal MV, Nagarajan ER, Ramalingan C. Functionalized zinc(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes: Synthesis, spectral and molecular structures of bis(N-cyclopropyl-N-4-methoxybenzyldithiocarbamato-S,S′)zinc(ii) and (2,2′-bipyridine)bis(N-cyclopropyl-N-4-methoxybenzyldithiocarbamato-S,S′)zinc(ii). J Saudi Chem Soc. 2018;22:527–37.10.1016/j.jscs.2017.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[5] Awang N, Baba I, Yamin BM, Ng SW. Bis(N-isobutyl-N-propyl-dithiocarbamato-κ2 S,S′) zinc(ii). Acta Crystallogr Sect E Struct Rep Online. 2010;66(2):m215.10.1107/S1600536810002825Search in Google Scholar

[6] Emima Jeronsia J, Allwin Joseph L, Annie Vinosha P, Jerline Mary A, Jerome, Das S. Camellia sinensis leaf extract mediated synthesis of copper oxide nanostructures for potential biomedical applications. Mater Today Proc. 2019;8:214–22.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.02.103Search in Google Scholar

[7] Motizuki K, Nishio Y, Shirai M, Suzuki N. Effect of intercalation on structural instability and superconductivity of layered 2H-type Nbse2 and NbS2. J Phys Chem Solids. 1996;57:1091–6.10.1016/0022-3697(95)00401-7Search in Google Scholar

[8] Prevenslik TV. Acoustoluminescence and sonoluminescence. J Lumin. 2000;87:1210–2.10.1016/S0022-2313(99)00513-XSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Mintcheva N, Gicheva G, Panayotova M, Kulinich SA. Room-temperature synthesis of zns nanoparticles using zinc xanthates as molecular precursors. Mater (Basel). 2020;13:171.10.3390/ma13010171Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Sanz M, López-Arias M, Marco JF, de Nalda R, Amoruso S, Ausanio G, et al. Ultrafast laser ablation and deposition of wide band gap semiconductors. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:3203–11.10.1021/jp108489kSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Sharma M, Jain T, Singh S, Pandey OP. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes under UV-Visible light using capped ZnS nanoparticles. Sol Energy. 2012;86:626–33.10.1016/j.solener.2011.11.006Search in Google Scholar

[12] Singh J, Rawat M. A review on zinc sulphide nanoparticles: from synthesis, properties to applications. J Bioelectron Nanotechnol. 2016;1–5.10.13188/2475-224X.1000006Search in Google Scholar

[13] Riaz S, Raza ZA, Majeed MI, Jan T. Synthesis of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their incorporation into poly(hydroxybutyrate) matrix in the formation of a novel nanocomposite. Mater Res Express. 2018;5:055027.10.1088/2053-1591/aac1f9Search in Google Scholar

[14] Dhand C, Dwivedi N, Loh XJ, Jie Ying AN, Verma NK, Beuerman RW, et al. Methods and strategies for the synthesis of diverse nanoparticles and their applications: a comprehensive overview. RSC Adv. 2015;5:105003–37.10.1039/C5RA19388ESearch in Google Scholar

[15] Vacassy R, Scholz SM, Dutta J, Plummer CJG, Houriet R, Hofmann H. Synthesis of controlled spherical zinc sulfide particles by precipitation from homogeneous solutions. J Am Ceram Soc. 1998;81:2699–705.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1998.tb02679.xSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Sharma M, Kumar S, Pandey OP. Study of energy transfer from capping agents to intrinsic vacancies/defects in passivated ZnS nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:2655–66.10.1007/s11051-009-9844-2Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mbese JZ, Ajibade PA. Synthesis, structural and optical properties of ZnS, CdS and HgS nanoparticles from dithiocarbamato single molecule precursors. J Sulfur Chem. 2014;35:438–49.10.1080/17415993.2014.912280Search in Google Scholar

[18] Srinivasan N, Thirumaran S. Synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles from pyridine adducts of zinc(ii) dithiocarbamates. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2014;17:964–70.10.1016/j.crci.2013.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bruker-AXS. APEX2. Version 2014.11-0. Madison: Bruker-AXS; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Sheldrick GM. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr Sect A Found Crystallogr. 2015;71:3–8.10.1107/S2053273314026370Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Sheldrick GM. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr Sect C Struct Chem. 2015;71:3–8.10.1107/S2053229614024218Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Hübschle CB, Sheldrick GM, Dittrich B. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J Appl Crystallogr. 2011;44:1281–4.10.1107/S0108767319098143Search in Google Scholar

[23] Bobinihi FF, Onwudiwe DC, Hosten EC. Synthesis and characterization of homoleptic group 10 dithiocarbamate complexes and heteroleptic Ni(ii) complexes, and the use of the homoleptic Ni(ii) for the preparation of nickel sulphide nanoparticles. J Mol Struct. 2018;1164:475–85.10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.03.063Search in Google Scholar

[24] Arul Prakasam B, Ramalingam K, Bocelli G, Cantoni A. NMR and fluorescence spectral studies on bisdithiocarbamates of divalent Zn, Cd and their nitrogenous adducts: Single crystal X-ray structure of (1,10-phenanthroline)bis(4-methylpiperazinecarbodithioato) zinc(ii). Polyhedron. 2007;26:4489–93.10.1016/j.poly.2007.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[25] Nyamen LD, Rajasekhar Pullabhotla VS, Nejo AA, Ndifon P, Revaprasadu N. Heterocyclic dithiocarbamates: precursors for shape controlled growth of CdS nanoparticles. N J Chem. 2011;35:1133.10.1039/c1nj20069kSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Nyamen LD, Rajasekhar Pullabhotla VSR, Nejo AA, Ndifon PT, Warner JH, Revaprasadu N. Synthesis of anisotropic PbS nanoparticles using heterocyclic dithiocarbamate complexes. Dalt Trans. 2012;41:8297–302.10.1039/c2dt30282aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Onwudiwe DC, Hosten EC. Synthesis, structural characterization, and thermal stability studies of heteroleptic cadmium(ii) dithiocarbamate with different pyridyl groups. J Mol Struct. 2018;1152:409–21.10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.09.076Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ivanov AV, Korneeva EV, Gerasimenko AV, Forsling W. Structural organization of nickel(ii), zinc(ii), and copper(ii) complexes with diisobutyldithiocarbamate: EPR, 13C and 15N CP/MAS NMR, and x-ray diffraction studies. Russ J Coord Chem. 2005;31:695–707.10.1007/s11173-005-0157-4Search in Google Scholar

[29] Onwudiwe DC, Ajibade PA. Synthesis and characterization of metal complexes of N-alkyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamates. Polyhedron. 2010;29:1431–6.10.1016/j.poly.2010.01.011Search in Google Scholar

[30] Benson RE, Ellis CA, Lewis CE, Tiekink ERT. 3D-, 2D- and 1D-supramolecular structures of {Zn[S2CN(CH2CH2OH)R]2}2 and their {Zn[S2CN(CH2CH2OH)R]2}2(4,4′-bipyridine) adducts for R = CH2CH2OH, Me or Et: polymorphism and pseudo-polymorphism. CrystEngComm. 2007;9:930–40.10.1039/b706442jSearch in Google Scholar

[31] Tan YS, Ooi KK, Ang KP, Akim AM, Cheah YK, Halim SN, et al. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and cell selectivity of zinc dithiocarbamates functionalized with hydroxyethyl substituents. J Inorg Biochem. 2015;150:48–62.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.06.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Paz FAA, Neves MC, Trindade T, Klinowski J. The first dinuclear zinc(ii) dithiocarbamate complex with butyl substituent groups. Acta Crystallogr Sect E Struct Rep Online. 2003;59:1067–9.10.1107/S160053680302419XSearch in Google Scholar

[33] Adeyemi JO, Onwudiwe DC, Ekennia AC, Okafor SN, Hosten EC. Organotin(iv) N-butyl-N-phenyldithiocarbamate complexes: Synthesis, characterization, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies. J Mol Struct. 2019;1192:15–26.10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.04.097Search in Google Scholar

[34] Berry RS. Correlation of rates of intramolecular tunneling processes, with application to some group V compounds. J Chem Phys. 1960;32:933–8.10.1063/1.1730820Search in Google Scholar

[35] Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van Rijn J, Verschoor GC. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(ii) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(ii) perchlorate. J Chem Soc, Dalt Trans. 1984;1349–56. 10.1039/DT9840001349.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Poplaukhin P, Tiekink ERT. Crystal structure of bis[N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-N-methyldithiocarbamato-κ 2 S, S′](pyridine)zinc(ii) pyridine monosolvate and its N-ethyl analogue. Acta Crystallogr Sect E Crystallogr Commun. 2017;73:1246–51.10.1107/S2056989017010568Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ajibade PA, Onwudiwe DC. Synthesis, characterization and thermal studies of 2,2′-bipyridine adduct of bis-(N-alkyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamato-S,S′)cadmium(ii). J Mol Struct. 2013;1034:249–56.10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.10.047Search in Google Scholar

[38] Awang N, Baba I, Yamin BM, Halim AA. Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial assay of 1, 10-phenanthroline and 2, 2′-bipyridyl adducts of cadmium(ii) N-sec-butyl-N-environmental health programme, faculty of allied health sciences, universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Sch World Appl Sci J. 2011;12:1568–74.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Adeyemi JO, Onwudiwe DC, Ekennia AC, Anokwuru CP, Nundkumar N, Singh M, et al. Synthesis, characterization and biological activities of organotin(iv) diallyldithiocarbamate complexes. Inorg Chim Acta. 2019;485:64–72.10.1016/j.ica.2018.09.085Search in Google Scholar

[40] Onwudiwe DC, Ajibade PA. Synthesis, characterization and thermal study of phenanthroline adducts of Zn (ii) and Cd(ii) Complexes of bis-N-alkyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamates. Asian J Chem. 2013;25:10057–61.10.14233/ajchem.2013.15135Search in Google Scholar

[41] Nomura R, Takabe A, Matsuda H. Facile synthesis of antimony dithiocarbamate complexes. Polyhedron. 1987;6:411–6.10.1016/S0277-5387(00)81000-1Search in Google Scholar

[42] Awang N, Nordin NA, Rashid N, Kamaludin NF. Synthesis and characterisation of phenanthroline adducts of Pb(ii) complexes of bis-N-alkyl-N-ethyldithiocarbamates. Orient J Chem. 2015;31:333–9.10.13005/ojc/310138Search in Google Scholar

[43] Bonati F, Ugo R. Organotin(iv) N,N-disubstituted dithiocarbamates. J Organomet Chem. 1967;10:257–68.10.1016/S0022-328X(00)93085-7Search in Google Scholar

[44] Tian X, Wen J, Wang S, Hu J, Li J, Peng H. Starch-assisted synthesis and optical properties of ZnS nanoparticles. Mater Res Bull. 2016;77:279–83.10.1016/j.materresbull.2016.01.046Search in Google Scholar

[45] Sun D, Du Y, Tian X, Li Z, Chen Z, Zhu C. Microwave-assisted synthesis and optical properties of cuprous oxide micro/nanocrystals. Mater Res Bull. 2014;60:704–8.10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.09.067Search in Google Scholar

[46] Ong CB, Ng LY, Mohammad AW. A review of ZnO nanoparticles as solar photocatalysts: synthesis, mechanisms and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;81:536–51.10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.020Search in Google Scholar

[47] Phuong Nguyen T, Duy Le A, Bich Vu T, Vinh Lam Q. Investigations on photoluminescence enhancement of poly(vinyl alcohol)-encapsulated Mn-doped ZnS quantum dots. J Lumin. 2017;192:166–72.10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.06.031Search in Google Scholar

[48] Bruchez M, Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Sci (80-). 1998;281(5385):2013–6. Published online 1998.10.1126/science.281.5385.2013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Denzler D, Olschewski M, Sattler K. Luminescence studies of localized gap states in colloidal ZnS nanocrystals. J Appl Phys. 1998;84(5):2841–5. Published online 1998.10.1063/1.368425Search in Google Scholar

[50] Ledoux G, Guillois O, Huisken F, Kohn B, Porterat D, Reynaud C. Crystalline silicon nanoparticles as carriers for the Extended Red Emission. Astron Astrophys. 2001;377:707–20.10.1051/0004-6361:20011136Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Damian C. Onwudiwe et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (ABB 2021)

- The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode

- Study of an adsorption method for trace mercury based on Bacillus subtilis

- Special Issue on The 1st Malaysia International Conference on Nanotechnology & Catalysis (MICNC2021)

- Mitigating membrane biofouling in biofuel cell system – A review

- Mechanical properties of polymeric biomaterials: Modified ePTFE using gamma irradiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of anthocyanins in Tibetan hulless barley from different geographical locations by UPLC-QTOF-MS and their antioxidant capacities

- Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil

- GC-MS analysis of mango stem bark extracts (Mangifera indica L.), Haden variety. Possible contribution of volatile compounds to its health effects

- Influence of nanoscale-modified apatite-type calcium phosphates on the biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms

- Removal of paracetamol from aqueous solution by containment composites

- Investigating a human pesticide intoxication incident: The importance of robust analytical approaches

- Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by chloroform fraction of Juniperus phoenicea and chemical constituents analysis

- Recovery of γ-Fe2O3 from copper ore tailings by magnetization roasting and magnetic separation

- Effects of different extraction methods on antioxidant properties of blueberry anthocyanins

- Modeling the removal of methylene blue dye using a graphene oxide/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite under sunlight irradiation by intelligent system

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation

- Full spectrum and genetic algorithm-selected spectrum-based chemometric methods for simultaneous determination of azilsartan medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan: Development, validation, and application on commercial dosage form

- Evaluation of the performance of immunoblot and immunodot techniques used to identify autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases

- Computational studies by molecular docking of some antiviral drugs with COVID-19 receptors are an approach to medication for COVID-19

- Synthesis of amides and esters containing furan rings under microwave-assisted conditions

- Simultaneous removal efficiency of H2S and CO2 by high-gravity rotating packed bed: Experiments and simulation

- Design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel thiophene, pyrimidine, pyrazole, pyridine, coumarin and isoxazole: Dydrogesterone derivatives as antitumor agents

- Content and composition analysis of polysaccharides from Blaps rynchopetera and its macrophage phagocytic activity

- A new series of 2,4-thiazolidinediones endowed with potent aldose reductase inhibitory activity

- Assessing encapsulation of curcumin in cocoliposome: In vitro study

- Rare norisodinosterol derivatives from Xenia umbellata: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activities and HPTLC quantification of rutin in white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and root extracts grown in Saudi Arabia

- Comparison of adsorption properties of commercial silica and rice husk ash (RHA) silica: A study by NIR spectroscopy

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a high-capacity material for next-generation sodium-ion capacitors

- Aroma components of tobacco powder from different producing areas based on gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry

- The effects of salinity on changes in characteristics of soils collected in a saline region of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Synthesis, properties, and activity of MoVTeNbO catalysts modified by zirconia-pillared clays in oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

- Synthesis and crystal structure of N,N′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea N,N-dimethylformamide

- Quantitative analysis of volatile compounds of four Chinese traditional liquors by SPME-GC-MS and determination of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities

- A novel separation method of the valuable components for activated clay production wastewater

- On ve-degree- and ev-degree-based topological properties of crystallographic structure of cuprite Cu2O

- Antihyperglycemic effect and phytochemical investigation of Rubia cordifolia (Indian Madder) leaves extract

- Microsphere molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction for diazepam analysis using itaconic acid as a monomer in propanol

- A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species

- Machine vision-based driving and feedback scheme for digital microfluidics system

- Study on the application of a steam-foam drive profile modification technology for heavy oil reservoir development

- Ni–Ru-containing mixed oxide-based composites as precursors for ethanol steam reforming catalysts: Effect of the synthesis methods on the structural and catalytic properties

- Preparation of composite soybean straw-based materials by LDHs modifying as a solid sorbent for removal of Pb(ii) from water samples

- Synthesis and spectral characterizations of vanadyl(ii) and chromium(iii) mixed ligand complexes containing metformin drug and glycine amino acid

- In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria with probiotic activity isolated from local pickled leaf mustard from Wuwei in Anhui as substitutes for chemical synthetic additives

- Utilization and simulation of innovative new binuclear Co(ii), Ni(ii), Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) diimine Schiff base complexes in sterilization and coronavirus resistance (Covid-19)

- Phosphorylation of Pit-1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at serine 126 is associated with cell proliferation and poor prognosis in prolactinomas

- Molecularly imprinted membrane for transport of urea, creatinine, and vitamin B12 as a hemodialysis candidate membrane

- Optimization of Murrayafoline A ethanol extraction process from the roots of Glycosmis stenocarpa, and evaluation of its Tumorigenesis inhibition activity on Hep-G2 cells

- Highly sensitive determination of α-lipoic acid in pharmaceuticals on a boron-doped diamond electrode

- Synthesis, chemo-informatics, and anticancer evaluation of fluorophenyl-isoxazole derivatives

- In vitro and in vivo investigation of polypharmacology of propolis extract as anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and chemical properties

- Topological indices of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph

- Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZnO catalyst and its catalytic synthesis of rosin glycol ester

- Construction of a new luminescent Cd(ii) compound for the detection of Fe3+ and treatment of Hepatitis B

- Investigation of bovine serum albumin aggregation upon exposure to silver(i) and copper(ii) metal ions using Zetasizer

- Discoloration of methylene blue at neutral pH by heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions using crystalline and amorphous iron oxides

- Optimized extraction of polyphenols from leaves of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) grown in Lam Dong province, Vietnam, and evaluation of their antioxidant capacity

- Synthesis of novel thiourea-/urea-benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens

- Simple modifications of nicotinic, isonicotinic, and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acids toward new weapons against plant diseases

- Synthesis, optical and structural characterisation of ZnS nanoparticles derived from Zn(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Presence of short and cyclic peptides in Acacia and Ziziphus honeys may potentiate their medicinal values

- The role of vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on prolonged anticonvulsant activity of terpene derivatives in pentylenetetrazole test

- GADD45B induced the enhancing of cell viability and proliferation in radiotherapy and increased the radioresistance of HONE1 cells

- Cannabis sativa L. chemical compositions as potential plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidinesynthase enzyme inhibitors: An in silico study for drug development

- Dynamics of λ-cyhalothrin disappearance and expression of selected P450 genes in bees depending on the ambient temperature

- Identification of synthetic cannabinoid methyl 2-{[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl] formamido}-3-methylbutanoate using modern mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques

- Study on the speciation of arsenic in the genuine medicinal material honeysuckle

- Two Cu(ii)-based coordination polymers: Crystal structures and treatment activity on periodontitis

- Conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in the presence of mesoporous aluminosilicate catalyst

- Review Articles

- Hsien Wu and his major contributions to the chemical era of immunology

- Overview of the major classes of new psychoactive substances, psychoactive effects, analytical determination and conformational analysis of selected illegal drugs

- An overview of persistent organic pollutants along the coastal environment of Kuwait

- Mechanism underlying sevoflurane-induced protection in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury

- COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Everything we know so far – A comprehensive review

- Challenge of diabetes mellitus and researchers’ contributions to its control

- Advances in the design and application of transition metal oxide-based supercapacitors

- Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil

- The structural chemistry of zinc(ii) and nickel(ii) dithiocarbamate complexes

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis natural products – A review

- Recent progress in direct urea fuel cell

- Rapid Communications

- A comparative morphological study of titanium dioxide surface layer dental implants

- Changes in the antioxidative properties of honeys during their fermentation

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study”

- Erratum to “Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “A nitric oxide-releasing prodrug promotes apoptosis in human renal carcinoma cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species”

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Visible light-responsive photocatalyst of SnO2/rGO prepared using Pometia pinnata leaf extract

- Antihyperglycemic activity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. leaf ethanol extract SNEDDS in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

- Selection of oil extraction process from Chlorella species of microalgae by using multi-criteria decision analysis technique for biodiesel production

- Special Issue on the 14th Joint Conference of Chemistry (14JCC)

- Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of isatin-pyrrole derivatives against HepG2 cell line

- CO2 gas separation using mixed matrix membranes based on polyethersulfone/MIL-100(Al)

- Effect of synthesis and activation methods on the character of CoMo/ultrastable Y-zeolite catalysts

- Special Issue on Electrochemical Amplified Sensors

- Enhancement of graphene oxide through β-cyclodextrin composite to sensitive analysis of an antidepressant: Sulpiride

- Investigation of the spectroelectrochemical behavior of quercetin isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum

- An electrochemical sensor for high sensitive determination of lysozyme based on the aptamer competition approach

- An improved non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor amplified with CuO nanostructures for sensitive determination of uric acid

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020

- Fast discrimination of avocado oil for different extracted methods using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectroscopy with PCA based on volatile organic compounds

- Effect of alkali bases on the synthesis of ZnO quantum dots

- Quality evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon wines in different vintages by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Diatomaceous Earth: Characterization, thermal modification, and application

- Electrochemical determination of atenolol and propranolol using a carbon paste sensor modified with natural ilmenite

- Special Issue on the Conference of Energy, Fuels, Environment 2020

- Assessment of the mercury contamination of landfilled and recovered foundry waste – a case study

- Primary energy consumption in selected EU Countries compared to global trends

- Modified TDAE petroleum plasticiser

- Use of glycerol waste in lactic acid bacteria metabolism for the production of lactic acid: State of the art in Poland

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Theoretical study of energy, inertia and nullity of phenylene and anthracene

- Banhatti, revan and hyper-indices of silicon carbide Si2C3-III[n,m]

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Occurrence of mycotoxins in selected agricultural and commercial products available in eastern Poland

- Special Issue on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants

- Acute and repeated dose 60-day oral toxicity assessment of chemically characterized Berberis hispanica Boiss. and Reut in Wistar rats

- Phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant, and anti-protein denaturation activities of Curcuma longa L. rhizome and leaves

- Antiplasmodial potential of Eucalyptus obliqua leaf methanolic extract against Plasmodium vivax: An in vitro study

- Prunus padus L. bark as a functional promoting component in functional herbal infusions – cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects

- Molecular and docking studies of tetramethoxy hydroxyflavone compound from Artemisia absinthium against carcinogens found in cigarette smoke

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2020)

- Preparation of cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) essential oil loaded poly(lactic acid) nanofibers

- Influence of mica mineral on flame retardancy and mechanical properties of intumescent flame retardant polypropylene composites

- Production and characterization of thermoplastic elastomer foams based on the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) rubber and thermoplastic material

- Special Issue on Applied Chemistry in Agriculture and Food Science

- Impact of essential oils on the development of pathogens of the Fusarium genus and germination parameters of selected crops

- Yield, volume, quality, and reduction of biotic stress influenced by titanium application in oilseed rape, winter wheat, and maize cultivations

- Influence of potato variety on polyphenol profile composition and glycoalcaloid contents of potato juice

- Carryover effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation and early weaning on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing Najdi lambs