Abstract

Ethnobotanical studies revealed the experience and knowledge of people who learned the therapeutic virtues of plants through trials and errors and transferred their knowledge to the next generations. This study determined the ethnobotanical use of Juniperus drupacea (Andiz) in the Antalya province and the current and future potential distribution areas of J. drupacea in Türkiye during 2041–2060 and 2081–2100 according to the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios and based on the IPSL-CM6A-LR climate change model. The very suitable areas encompassed 22379.7 km2. However, when the SSP2-4.5 scenario was considered, the areas most suitable for J. drupacea comprised 6215.892 km2 for 2041–2060 and 378.318 km2 for 2081–2100. Based on the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the area most suitable for J. drupacea was 979.082 km2 for 2041–2060. However, no suitable areas were identified with the SSP5-8.5 scenario for 2081–2100. Considering the models for the future estimated distribution areas of J. drupacea, serious contractions endangering the species are predicted in its distribution areas. Therefore, scientific research should focus on identifying J. drupacea populations and genotypes that demonstrate resilience to future drought conditions resulting from climate change. This endeavor is crucial as it holds significant ecological and economic values.

1 Introduction

Humans have always benefited from nature to meet their food, clothing, cooking, and fuel needs. The information obtained through trial and error has been developed and carried to the present day, and ethnobotanical studies have gained importance [1–4]. In recent years, technological development, urban transitions, modern life, and the relative loss of traditions and customs caused a decrease in orally transmitted information about plants. In this respect, ethnobotanical studies are valuable for recording “humanity’s knowledge of plants” [3].

Türkiye is rich in flora and plant diversity, and ethnobotanical studies are still conducted by many researchers in different regions of the country; however, the actual use of the plants identified by such studies remains poorly known. Recently, the demand for forest and natural resources has increased. This increase is essential in meeting commercial gains and local needs, especially for forest villagers.

Cupressaceae is a monoic or dioecious family. Its members are evergreen small trees or shrubs, resinous, distinctively fragrant, and highly branched. Some leaves are needle-shaped, while others are flakes [5,6]. Juniperus drupacea Labill, belonging to the family Cupressaceae, is a wingless tree with thin trunk shells and seeds. It mostly grows on the Mediterranean coast and back-Mediterranean forests at 600–1,750 m of altitude [5,7]. It is naturally distributed in Türkiye and has socio-economic and ecological contributions. Different parts of the tree are used as folk medicine and food. It is used to treat respiratory and urinary tract infections, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Additionally, the molasses obtained from its fruits is consumed as food; its local consumption has spread throughout Türkiye in recent years as food and food support [5].

J. drupacea is endangered because of natural regeneration, logging, forbidden grazing, illegal collection for ethnobotanical use, and climate change. The natural regeneration of the species is difficult due to slow growth, low seed viability, and germination problems [8]. Additionally, the decrease in juniper stands destroys nutrient-rich soils well suited for seed growing under denser tree covers [9,10]. This situation threatens the survival of juniper species. Therefore, taking measures to protect existing juniper stands and ensure their sustainability is necessary [11].

This study aimed to determine the ethnobotanical use of J. drupacea in the Antalya region. Determining the usage areas of plants and their local names is essential for transferring human heritage to future generations. Additionally, with technological development and urban transitions, the loss of ethnobotanical information becomes problematic, making the regular recording of such information crucial.

The second part of the study aimed to determine the potential distribution areas of J. drupacea over time based on climate change scenarios using maximum entropy (MaxEnt). Climate change increases the danger of plant species extinction by negatively affecting their biodiversity and geographical distribution [12,13]. Reintroducing and rehabilitating threatened species in terrestrial ecosystems requires detailed knowledge of their potential distribution range. Global scientific studies and observations have determined that plants migrate to high altitudes due to climate change, which will continue in the next 100 years [14–16]. MaxEnt, an algorithm used to model the appropriate geographical distribution of species based on the species distribution model, was used in this study [17]. An evaluation based on machine learning was made to determine future strategies for the conservation and sustainability of J. drupacea.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Determining ethnobotany properties

A questionnaire of 20 questions was prepared, and interviews were conducted with the local people to determine the ethnobotanical characteristics of J. drupacea in the Kuyucak district of Antalya province. J. drupacea is widespread throughout the Mediterranean region of Türkiye, and Kuyucak district was chosen as the study area because it produces Andiz molasses densely.

Sixty-five people were interviewed in the region. The questionnaire included the following questions, among others: (Question 6) What is the situation on plant use that grows naturally in the region? (Question 8) For what purpose do you use the Andiz tree? (Question 10) What is taken into consideration when collecting the Andiz tree from nature? (Question 11) How are the collected plants stored? Moreover, general research was conducted on Questions 8–14. For multiple-choice questions, each option was evaluated as a % in itself.

Participants were allowed to answer the questionnaire alone, at their own free will, without external influence. The following equation was used to determine the sample size [18]:

where n is the sample size, Z is the confidence coefficient (Z = 1.96 for 95% confidence interval), N is the main mass size, p and q are the probability of finding the desired size in the population (0.5), and D is the accepted sampling error (10%).

Using this equation, the sample size was found to be 50. The survey of 65 people was considered, including the margin of error. Questionnaires were evaluated by converting the numerical values of the answered choices into percentages in frequency tables. Statistical Package for Social Science 25.0 was used for the analysis.

2.2 Prediction of present and future potential distribution areas of J. drupacea

MaxEnt 3.4.1, which produces a species distribution model, was used to determine the potential distribution areas of J. drupacea according to climate change scenarios. The existing data of the species (sample points), environmental variables (bioclimatic data), and future climate change scenarios are required to obtain results from the MaxEnt algorithm. Sample spots of J. drupacea were obtained from available literature and field observations (Table 1) [19–22]. The coordinates of these points were marked in the WGS84 coordinate system in the current version of the QGIS 3.22 program utilizing Google Earth Satellite 5 m resolution base maps as the base data (Figure 1) [23].

Attribute information of J. drupacea Labill

| J. drupacea | X | Y | Province | District | Avg. sol. rad. | Avg. temp. | Avg. wind | Avg. prec. | Elev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35.006 | 37.382 | Adana | Karaisalı | 2.06 | 11.79 | 2.06 | 52.71 | 1,001 |

| 2 | 31.83 | 37.07 | Antalya | Akseki | 2.33 | 10.50 | 2.33 | 57.13 | 1,500 |

| 3 | 31.715 | 37.261 | Antalya | Akseki | 2.17 | 10.77 | 2.17 | 55.44 | 1,201 |

| 4 | 32.326 | 36.668 | Antalya | Alanya | 2.63 | 9.05 | 2.63 | 60.70 | 1,767 |

| 5 | 31.828 | 36.607 | Antalya | Alanya | 2.36 | 18.84 | 2.36 | 86.16 | 41 |

| 6 | 32.338 | 36.764 | Antalya | Gündoğmuş | 2.62 | 8.15 | 2.62 | 59.47 | 1,836 |

| 7 | 35.989 | 35.963 | Hatay | Yayladağı | 3.28 | 13.69 | 3.28 | 96.12 | 885 |

| 8 | 37.244 | 37.69 | Kahramanmaraş | Çağlayancerit | 2.21 | 10.34 | 2.21 | 46.84 | 1,386 |

| 9 | 36.381 | 37.595 | Kahramanmaraş | Andırın | 2.07 | 10.98 | 2.07 | 58.02 | 1,243 |

| 10 | 37.06 | 37.693 | Kahramanmaraş | Dulkadiroğlu | 2.17 | 10.17 | 2.17 | 47.54 | 1,384 |

| 11 | 36.578 | 37.918 | Kahramanmaraş | Onikişubat | 2.13 | 9.48 | 2.13 | 51.50 | 1,424 |

| 12 | 36.83 | 37.88 | Kahramanmaraş | Onikişubat | 2.07 | 11.13 | 2.07 | 50.80 | 1,126 |

| 13 | 32.955 | 37.071 | Karaman | Karaman M. | 2.26 | 9.71 | 2.26 | 43.07 | 1,460 |

| 14 | 34.566 | 37.265 | Mersin | Çamlıyayla | 2.39 | 7.53 | 2.39 | 42.84 | 1,660 |

| 15 | 34.67 | 37.13 | Mersin | Çamlıyayla | 2.31 | 13.29 | 2.31 | 54.01 | 938 |

| 16 | 34.134 | 36.746 | Mersin | Erdemli | 2.67 | 11.06 | 2.67 | 51.34 | 1,399 |

| 17 | 34.316 | 36.767 | Mersin | Erdemli | 2.62 | 13.46 | 2.62 | 57.49 | 793 |

| 18 | 33.791 | 36.569 | Mersin | Silifke | 2.63 | 10.63 | 2.63 | 51.88 | 1,504 |

| 19 | 34.495 | 37.096 | Mersin | Toroslar | 2.38 | 11.28 | 2.38 | 46.56 | 1,289 |

| 20 | 34.53 | 36.913 | Mersin | Toroslar | 2.48 | 15.07 | 2.48 | 59.78 | 687 |

| 21 | 36.219 | 37.622 | Osmaniye | Kadirli | 1.97 | 10.90 | 1.97 | 58.67 | 1,253 |

Input data for the MaxEnt area of J. drupacea.

The bioclimatic data from the WorldClim [24] data-sharing site comprise 19 bioclimatic variables produced from the lowest and highest temperature averages and annual precipitation averages (Table 2) to find the current potential distribution areas. Descriptive data, such as elevation, aspect, slope, temperature, precipitation, humidity, and insolation, for sample points were collected using maps from the database [24]. Predictive modeling of the current and future potential distribution areas relied specifically on the WorldClim database, particularly version 2.1 [24]. This database includes monthly climate data from 1970 to 2000, encompassing minimum, average, and maximum temperatures, precipitation, solar radiation, wind speed, water vapor pressure, and total precipitation.

Bioclimatic variables (WorldClim [24])

| BIO1 = Annual mean temperature |

| BIO2 = Mean diurnal range (mean of monthly (max temp − min temp)) |

| BIO3 = Isothermality (BIO2/BIO7) (×100) |

| BIO4 = Temperature seasonality (standard deviation × 100) |

| BIO5 = Max temperature of warmest month |

| BIO6 = Min temperature of coldest month |

| BIO7 = Temperature annual range (BIO5–BIO6) |

| BIO8 = Mean temperature of wettest quarter |

| BIO9 = Mean temperature of driest quarter |

| BIO10 = Mean temperature of warmest quarter |

| BIO11 = Mean temperature of coldest quarter |

| BIO12 = Annual precipitation |

| BIO13 = Precipitation of wettest month |

| BIO14 = Precipitation of driest month |

| BIO15 = Precipitation seasonality (coefficient of variation) |

| BIO16 = Precipitation of wettest quarter |

| BIO17 = Precipitation of driest quarter |

| BIO18 = Precipitation of warmest quarter |

| BIO19 = Precipitation of coldest quarter |

Bioclimatic variables, with a spatial resolution of 2.5 min (approximately 20 km²), were utilized to determine the current distribution and were derived from data observed in WorldClim version 2.1. Detailed information regarding these specific variables is provided in Table 2. The IPSL-CM6A-LR climate change model, which is the latest version of the Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace (IPSL) climate model and also includes the carbon cycle, was used to extract the future distribution areas of J. drupacea [25]. According to the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, the potential distribution areas of the species in the 2041–2060 (∼2050) and 2081–2100 (∼2090) time intervals were modeled and presented with maps and tables. Based on the model results, the loss and gain values in the species’ distribution areas were deduced from the intersection of the current and future potential distribution areas.

The overall methodological flowchart for the MaxEnt modeling of J. drupacea is presented in Figure 2. The flowchart comprises four main steps: (1) preparing and pre-processing the environmental variables, (2) assessing crucial factors and predicting potential distribution areas using MaxEnt models under various climate scenarios, (3) validating the distribution through field investigations and statistical methods, and (4) analyzing the characteristics of the range shift for J. drupacea.

Flowchart illustrating the methodology employed for MaxEnt modeling and forecasting the future potential distribution of J. drupacea under climate change scenarios.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Ethnobotany properties

The survey participants included 56.9% of women and 43.1% of men, among which 69.7% were married. The average age of participants was 60 years and above. About 26.2% of the participants were primary school-secondary education graduates, 52.9% were unemployed/housewives, 34.4% were self-employed, and 12.6% were public sector workers (Table 3).

Demographic characteristics of survey participants

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 37 | 56.9 |

| Male | 28 | 43.1 |

| Total | 65 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 20 | 30.3 |

| Married | 45 | 69.7 |

| Total | 65 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 | 5 | 7.7 |

| 31–40 | 11 | 17 |

| 41–50 | 14 | 21.5 |

| 51–60 | 10 | 15.4 |

| >60 | 25 | 38.4 |

| Total | 65 | 100 |

| Education status | ||

| İlliterate | 5 | 7.7 |

| Primary school | 17 | 26.2 |

| Secondary school | 17 | 26.2 |

| High school | 8 | 12.3 |

| University/undergraduate | 15 | 23 |

| Master | 2 | 3.1 |

| PhD | 1 | 1.5 |

| Total | 65 | 100 |

| Profession | ||

| Housewife-not working | 34 | 52.9 |

| Self-employment | 22 | 34.4 |

| Government official | 9 | 12.6 |

| Total | 119 | 100 |

Around 98.5% of the participants benefited from the plants that grow naturally in the region and used J. drupacea. According to the research results, 98.5% of the local people benefited from plants for health and treatment, 88.1% for food/spices, 1.5% for cosmetic and aesthetic purposes, and 1.5% for pleasure. About 87.7% of the participants obtained the plants by collecting them from nature.

Regarding which parts of the plant they most benefit from, 98.5% mentioned the cones, 3.1% the flowers, and 1.5% the leaves. When asked about the collection period, 23.1% answered October–November and September–October, 18.5% September–November, 13.8% October, 1.5% October–November, and 6.2% October–December. 9.2% said they did not collect the plant. About the Andiz they collected, 95.4% stated they preserved it as molasses, and 6.2% dried the cones, flowers, and leaves. When asked about their consumption time, 84.6% said as they get sick, 35.4% as needed, 20% when needed, and 1.5% every day. When collecting J. drupacea from nature, 87.7% pay attention to the mature cones, 52.3% to collect in the right season, 23.1% to the plants’ health, 16.9% to the cleanliness and hygiene of the collection area, 4.6% to the completeness of all the plant’s organs. When asked if they had heard about the potential side effects of using the plant, 56.9% said no and 43.1% said they had heard of side effects but did not see any. Among the factors influencing people’s consumption, 83.1% were from family, 72.3% from people around, 6.2% from printed media, 3.1% from books/magazines, 1.5% from audio-visual media, and 1.5% from advertisements. Finally, when asked about the way they consume the plant, 78% said as molasses when they get sick, one spoon a day, 11% as molasses two spoons a week, and 11% when needed. 96% of the participants stated that they obtained molasses by boiling the cones of the Andiz tree and 4% stated that they bought it ready-made. To make molasses, Andiz cones are collected from nature and passed through a pine cone crushing machine to obtain flour. The flour is kept in water for 48 h and filtered through a sieve before boiling. Boiling continues until the flour turns into molasses. The formed pulp is taken out during boiling.

About 44% of the participants reported selling the products they obtained from the Andiz tree and sending the molasses to companies in metropolitan cities. 45% of them sell it in local markets, 7% do not sell it but collect enough molasses for their own family’s consumption, and 4% stated that they do not sell it but transfer it ready-made and buy it from the markets. About the way they consume the molasses obtained from the Andiz, 41% answered a spoonful a day to treat colds, 40% said a spoonful twice a week as an immune booster, and 12% said one spoonful a day to treat fatigue, 4% answered one spoonful a day as an appetizer, and 3% consume one spoonful every other day to treat stomach discomfort, sore throat, runny nose, and loss of appetite. Molasses has reached a central position today with the development of production technologies and the increasing interest in nutrient-rich natural products [26].

Andiz tree fruits contain a hard seed, from which Andiz rosary is made. Andiz molasses is made from the outer shells of the Andiz cones. In the villages of the Taurus Mountains, “Andiz Molasses” is traditionally obtained by boiling young cones with water. The taste of this molasses is slightly bitter, and its production is limited since it is laborious. Andiz molasses can regulate the amount of sugar in the blood and is good for anemia; it is used to treat bronchitis, cough, mouth sores, tuberculosis, kidney inflammation, psoriasis, nausea, and hemorrhoids and is beneficial for the lungs and liver. Andiz molasses is especially rich in minerals; the potassium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and sodium content of Andiz molasses produced by traditional methods is quite high, especially for grape, carob, and fig molasses [27]. The results of our survey indicate that molasses obtained from the fruits of the Andiz tree is used extensively by the local people to treat various diseases.

3.2 Prediction of potential distribution areas of J. drupacea

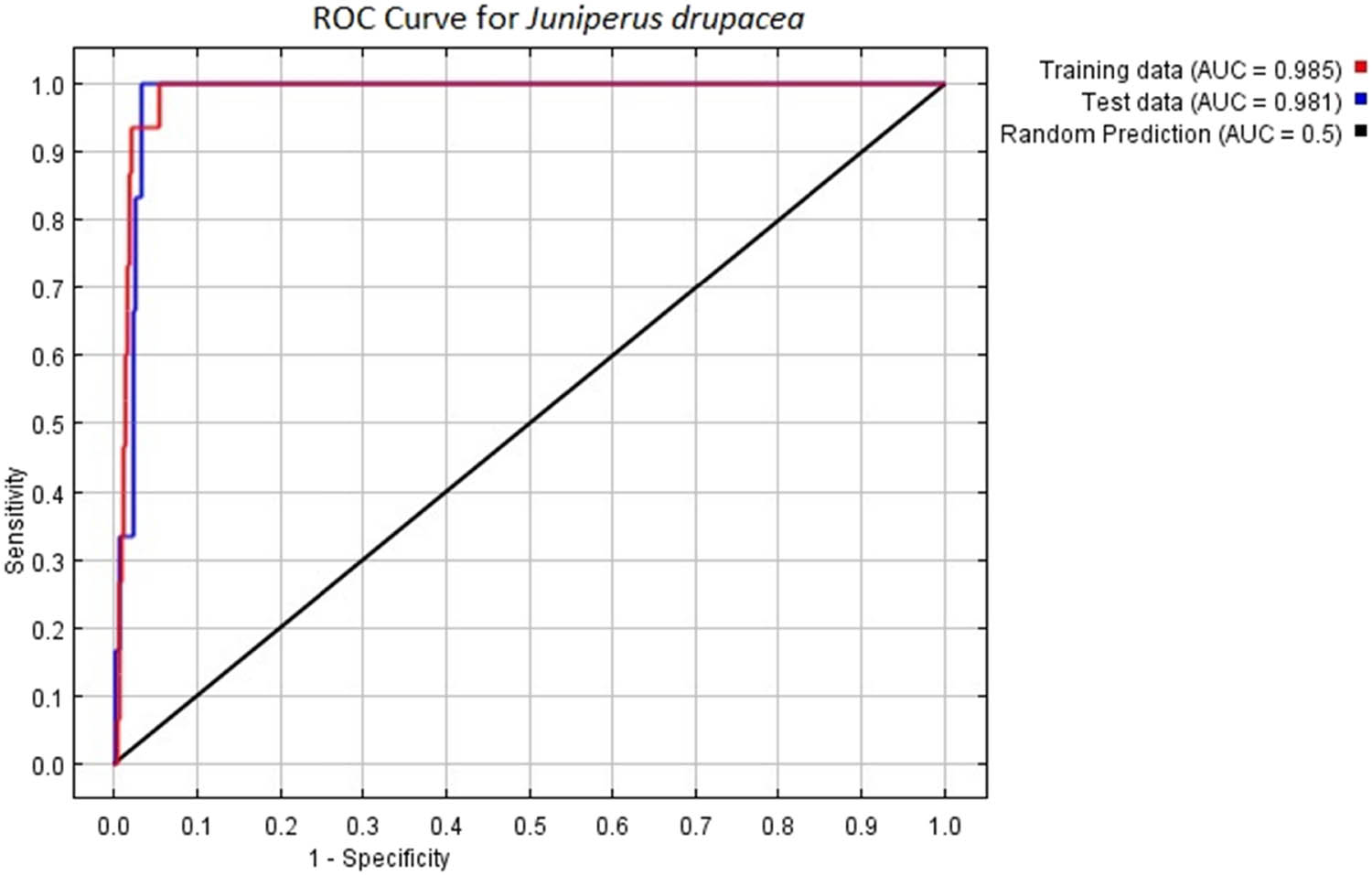

The success of MaxEnt models was tested with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC). The model’s accuracy increases as the area under the ROC curve (AUC) value approaches 1. If the AUC exceeds 0.5, the model performs better than random prediction [28–32]. The AUC value of 0.985 in the model output indicates that the model is very sensitive and accurate (Figure 3).

ROC curve for J. drupacea.

The MaxEnt model also offers the Jackknife test option, which presents the importance levels of the variables during the process. The Jackknife test results for J. drupacea indicate that the most important variables are related to precipitation, including the Precipitation of Driest Quarter (BIO17), Precipitation of Driest Month (BIO14), Precipitation of Warmest Quarter (BIO18), and Precipitation Seasonality (BIO15) (Figure 4).

Jackknife test for J. drupacea.

In the MaxEnt algorithm, the asset value occurs between 0 and 1, and the presence increases as it approaches 1. The suitability values for current and future potential spread are under five classes: “0” is not suitable, “0–0.25” is very suitable, “0.25–0.5” is less suitable, “0.5–0.75” is suitable, and “0.75–1” is very suitable. These values were collected, and the areas were calculated in km2 [33,34]. Comparing the potential current distribution areas of the model with the sample points indicates that they largely overlap with the natural distribution areas (Figure 5).

Potential current distribution of J. drupacea.

The study utilized a set of new scenarios developed for CMIP6 to offer a more comprehensive future outlook as part of the sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC6). The IPCC AR5 incorporates four representative concentration pathways (RCPs), exploring potential future greenhouse gas emissions. These scenarios are known as RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5. The study employed updated versions of these scenarios from CMIP6, known as shared socio-economic pathways (SSPs), which include SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP4-6.0, and SSP5-8.5. Notably, the study focused on the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. The study incorporated two specific SSPs from CMIP6: SSP2, characterized by moderate forcing levels in a temperate scenario and SSP5, representing high-level global resource usage. These scenarios, as outlined by Hausfather et al. [35], were analyzed for 2041–2060 and 2081–2100. Considering the models created according to the SSP2-45 scenario (Figure 6), there will be contractions in the species’ distribution area in the ∼2050 period, and more than half of the areas classified as very suitable and suitable will be lost. Suitable distribution areas will remain very limited and in small pieces.

Potential distribution of J. drupacea for ∼2050 (a) and ∼2090 (b) according to the SSP2-4.5 scenario.

In the SSP5-85 scenario (Figure 7), very suitable distribution areas in the ∼2050 period will be limited and in small pieces, similar to the ∼2090 period in the SSP2-45 scenario, and only very few suitable areas will be available for the species distribution in the ∼2090 period (Table 4). The total of the current distribution areas indicates a decrease to 1 in 15.

Potential distribution of J. drupacea for ∼2050 (a) and ∼2090 (b) according to the SSP5-8.5 scenario.

Potential geographical distribution of J. drupacea L. currently and in the future according to the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 climate scenarios (km2)

| SSP2-4.5 | SSP5-8.5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 2041–2060 | 2081–2100 | 2041–2060 | 2081–2100 | |

| Unsuitable | 533971 | 636051.6 | 658788.3 | 646364.2 | 764438.9 |

| Very low suitable | 150677.9 | 97106.3 | 86040.8 | 94763.22 | 15506.09 |

| Low suitable | 50264.61 | 25002.98 | 22422.9 | 25747.09 | 0 |

| Suitable | 22651.89 | 15568.23 | 12314.68 | 12091.45 | 0 |

| Very suitable | 22379.7 | 6215.892 | 378.318 | 979.082 | 0 |

The future change of the current state of J. drupacea toward loss and gain is mapped in Figure 8, and the potential areas are given in Table 5 in km2. The maps indicate that the losses are in the majority. Only the SSP5-85 scenario for the ∼2050 period indicates a gain higher than the other period and scenario.

Change status of J. drupacea for ∼2050 and ∼2090 according to the SSP2-4.5 (a, b) and SSP5-8.5 (c, d) scenarios.

Spatial changes between current and predicted distribution areas of J. drupacea under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios for 2050 and 2090 in Türkiye (km2)

| SSP2-4.5 | SSP5-8.5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Current to ∼2050 | Current to ∼2090 | Current to ∼2050 | Current to ∼2090 |

| Stable | 71519.951 | 48118.33 | 55939.82 | 204.5 |

| Loss | 174230.408 | 197040.3 | 188098.9 | 245769.6 |

| Gain | 570.588 | 1857.909 | 7778.238 | 0 |

| Unsuitable | 533624.09 | 532928.5 | 528128.1 | 533971 |

Climate change is a critical contributor to habitat loss and biodiversity decline, as evidenced by numerous studies. The complexity of topographical variations complicates the prediction of the impact of climate change on habitat diversity and species. Nevertheless, studies indicate that certain species will likely migrate northward, while endemic species may face extinction risks [31,33,36–42]. Our results highlight the substantial influence of climate change on the Mediterranean Ecosystem, especially within the habitats of species like J. drupacea.

Walas et al. [43] have demonstrated that precipitation is crucial in the distribution of J. drupacea, mirroring our findings. Their study focused on Türkiye and examined the past, present, and future trends, predicting significant declines in the potential distribution areas of this species. In a similar study, Arslan et al. [44] determined the distribution areas of J. foetidissima in the 2041–2060 and 2081–2100 periods and concluded that, in the case of climate change, the adaptation resistance of the species would be low and species protection studies should be conducted.

4 Conclusion

“Andiz Molasses” obtained from J. drupacea fruits is used extensively as a folk remedy and food for its nutritional content. Our research on the ethnobotanical use of J. drupacea in the Antalya region determined that 98.5% of the local people use the Andiz plant, and 95.4% benefit from the obtained molasses. The molasses is used by the local people to treat colds, as an immune booster, against weakness, to treat stomach discomfort, sore throat, runny nose, and anorexia as an appetizer.

The estimated future distribution areas of J. drupacea due to climate change over time indicate serious contractions in the species’ distribution areas, which are currently in the Mediterranean region of Türkiye. Based on the SSP5-8.5 scenario for the ∼2090 period, very few suitable areas will remain for this species, and the continuity of the species in our country will be endangered. The tendency of the species to adapt by ascending to higher altitudes is seen in the SSP5-8.5 scenario for the ∼2050 period. However, the model results indicate a transition from an unsuitable area to very few suitable areas in this region, which will not ensure the continuity of the species. The species will suffer from serious problems, especially due to the changes in precipitation, according to the Jackknife results in the two periods.

To separate J. drupacea from the climate change disaster with the least damage, determining the in situ, ex situ, and gen-protection areas and conducting various studies to create populations in emerging potential areas is necessary.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved. The third author, Almira Uzun, is a PhD scholarship holder of YÖK 100/2000 in the thematic field of sustainable forestry and forest disaster.

-

Author contributions: A.G.S. designed the investigation; G.T. and H.F. conducted the questionnaires, A.G.S., G.T., and A.U. made data curation. A.G.S. and A.U. modeled the present and future distribution areas of Juniperus drupacea and A.G.S. prepared and edited the original draft with contributions from all authors.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Kocyigit M. An ethnobotanical research in Yalova Province. Master’s thesis. Istanbul, Turkish: Istanbul University, Institute of Health Sciences; 2005. p. 193.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Faydalıoglu E, Surucuoglu MS. Use and economic importance of medicinal and aromatic plants from past to present. Kastamonu Univ Faculty Forestry Mag. 2011;11:52–67. Turkish.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Kendir G, Guvenc A. A general overview of ethnobotany and ethnobotanical studies done in Turkey. Hacet Univ Faculty Pharm Mag. 2010;30:49–80. Turkish.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Oztürk F, Dolarslan M, Gul E. Ethnobotany and historical development. Turkish Sci Dervish Mag. 2016;2:11–3. Retrieved from. http://dergipark.gov.tr/derleme/issue/35098/389371.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kocakulak E. Researches on the essential oils of Juniperus drupacea Lab. Ankara: Gazi University; 2007. p. 113.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Capa M. Investigation that antioxidant activity of various extracts of Hippophae rhamnoides and Juniperus drupacea. PhD thesis. Erzurum: Atatürk University; 2017. p. 99.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Tunalıer Z. Wood essential oils of Juniperus foetidissima Willd. PhD thesis. Eskişehir: Anadolu University; 1999. p. 155.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Tilki F. Preliminary results on the effects of various pretreatments on seed germination of Juniperus oxycedrus L. Seed Sci Technol. 2007;35:765–70. 10.15258/sst.2007.35.3.25.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Kose H. Research on seed germination methods of some woody landscape plants found in natural vegetation III. Juniperus oxycedrus L. Anadolu J AARI. 2000;10:88–100.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Rupprecht F, Oldeland J, Finckh M. Modelling potential distribution of the threatened tree species Juniperus oxycedrus: how to evaluate the predictions of different modelling approaches? J Veg Sci. 2011;22:647–59. 10.1111/j.16541103.2011.01269.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Pinna MS, Cañadas EM, Fenu G, Bacchetta G. The European Juniperus habitat in the Sardinian coastal dunes: implication for conservation. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2015;164:214–20. 10.1016/j.ecss.2015.07.032.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Chakraborty A, Joshi PK, Sachdeva K. Predicting distribution of major forest tree species to potential impacts of climate change in the central Himalayan region. Ecol Eng. 2016;97:593–609.10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.10.006Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zhao H, Zhang H, Xu C. Study on Taiwania cryptomerioides under climate change: MaxEnt modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2020;24:e01313.10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01313Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Abdelaal M, Fois M, Fenu G, Bacchetta G. Using MaxEnt modeling to predict the potential distribution of the endemic plant Rosa arabica Crép. in Egypt. Ecol Inf. 2019;50:68–75.10.1016/j.ecoinf.2019.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Arslan ES, Akyol A, Orucu OK, Sarikaya AG. Distribution of rose hip (Rosa canina L.) under current and future climate conditions. Reg Environ Change. 2020;20:107. 10.1007/s10113-02001695-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Li G, Huang J, Guo H, Du S. Projecting species loss and turnover under climate change for 111 Chinese tree species. Ecol Manag. 2020;477:118488.10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118488Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Elith J, Phillips SJ, Hastie T, Dudik M, Chee YE, Yates CJ. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Divers Distrib. 2011;17(1):43–57. 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Karasar N. Bilimsel araştırma ve yöntemi (15. baskı). Ankara, Turkish: Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık; 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Davis PH. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands.: C. I-XI. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 1965.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] GBIF. Global biodiversity information facility. free and open access to biodiversity data; 2021. https://www.gbif.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] OGM. Primary tree species distributed in our forests. Ankara: Forestry General Directorate; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Tubives. Turkish Plants Data Service; 2004. http://194.27.225.161/yasin/tubives/index.php?sayfa=1&tax_id=9301.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] QGIS. QGIS 3.22 Bialowieza – A Free and Open GIS; 2021. https://www.qgis.org/en/site/forusers/visualchangelog322/index.html.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] WorldClim. Global climate and weather data – WorldClim. 2020; https://worldclim.org/data/index.html.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] IPCC. IPCC climate change: The physical science basis. contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Ereli E. Determination of the effect of different oath molasses production methods on phenolic compounds and some quality parameters. Adana, Turkish: Adana Alparslan Türkeş Science and Technology University; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Karaca I. Pekmez örneklerinde vitamin ve mineral tayini. Malatya, Turkish: Inonu University; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Süel H, Mapping habitat suitability of game animals in Sütçüler District, Isparta. PhD thesis. Isparta: Suleyman Demirel University; 2014. p. 151.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Mert A, Kıraç A. Habitat suitability mapping of Anatololacerta danfordi (Günter, 1876) in Isparta-Sütçüler District. Bilge Sci. 2017;1:16–22.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Oruc MS, Mert A, Ozdemir I. Modelling habitat suitability for red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) using environmental variables in çatacık region. Bilge Sci. 2017;1:135–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Dulgeroglu C, Aksoy A. Predicting impacts of climate change on geographic distribution of Origanum minutiflorum Schwarz & PH Davis using maximum entropy algorithm. Erzincan Üniv Fen Bilim Enst Derg. 2018;11:182–90.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Sarikaya AG, Orucu OK. Maxent modeling for predicting the potantial distribution of Arbutus andrachne L. in Turkey. Kuwait J Sci. 2021;4(2):1–13.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Coban HO, Orucu OK, Arslan ES. MaxEnt modeling for predicting the current and future potential geographical distribution of Quercus libani Olivier. Sustainability. 2020;12:2671.10.3390/su12072671Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Uzun A, Aksu B, Uzun T. Prediction of present and future distribution areas of Acer campestre L. subsp. campestre (field maple) using the maxent model. Turkish J Landsc Res. 2020;3:108–19.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Hausfather Z, Drake HF, Abbott T, Schmidt GA. Evaluating the performance of past climate model projections. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47:e2019GL085378. 10.1029/2019GL08537.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Yi YJ, Cheng X, Yang ZF, Zhang SH. Maxent modeling for predicting the potential distribution of endangered medicinal plant (H. riparia Lour) in Yunnan, China. Ecol Eng. 2016;92:260–9. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.04.010.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Akyol A, Orucu OK, Arslan ES, Sarikaya AG. Predicting of the current and future geographical distribution of Laurus nobilis L. under the effects of climate change. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195:459.10.1007/s10661-023-11086-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Akhter S, Mc Donald MA, Van Breugel P, Sohel S, Kjaer ED, Mariott R. Habitat distribution modelling to identify areas of high conservation value under climate change for Mangifera sylvatica Roxb. of Bangladesh. Land Use Pol. 2017;60:223–32. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.027.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Al-Qaddi N, Vessella F, Stephan J, Al-Eisawi D, Schirone B. Current and future suitability areas of kermes oak (Quercus coccifera L.) in the Levant under climate change. Reg Environ Change. 2017;17:143–56. 10.1007/s10113-016-0987-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Thuiller W, Lavore S, Araújo MB, Sykes MT, Prentice IC. Climate change threats to plant diversity in Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8245–50. 10.1073/pnas.0409902102.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Babalik AA, Sarikaya O, Orucu OK. The current and future compliance areas of kermes oak (Quercus coccifera L.) under climate change in Turkey. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2021;30:406–13.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Kumar D, Rawat S, Joshi R. Predicting the current and future suitable habitat distribution of the medicinal tree Oroxylum indicum (L.) Kurz in India. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2021;23:100309. 10.1016/j.jarmap.2021.100309.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Walas Ł, Sobierajska K, Ok T, Donmez AA, Kanoglu SS, Dagher-Kharrat MB, et al. Past, present, and future geographic range of an oro-Mediterranean Tertiary relict: the Juniperus drupacea case study. Reg Environ Change. 2019;19:1507–20.10.1007/s10113-019-01489-5Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Arslan ES, Gülcin D, Sarikaya AG, Olmez Z, Gulcu S, Sen I, et al. Modeling of the current and future potential distribution of stinking juniper (Juniperus foetidissima Willd.) in Turkey with machine learning techniques. Eur J Eng Sci Tech. 2021;22:1–12. 10.31590/ejosat.848961).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Constitutive and evoked release of ATP in adult mouse olfactory epithelium

- LARP1 knockdown inhibits cultured gastric carcinoma cell cycle progression and metastatic behavior

- PEGylated porcine–human recombinant uricase: A novel fusion protein with improved efficacy and safety for the treatment of hyperuricemia and renal complications

- Research progress on ocular complications caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus and the function of tears and blepharons

- The role and mechanism of esketamine in preventing and treating remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia based on the NMDA receptor–CaMKII pathway

- Brucella infection combined with Nocardia infection: A case report and literature review

- Detection of serum interleukin-18 level and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and its clinical significance

- Ang-1, Ang-2, and Tie2 are diagnostic biomarkers for Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematous

- PTTG1 induces pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and promotes aerobic glycolysis by regulating c-myc

- Role of serum B-cell-activating factor and interleukin-17 as biomarkers in the classification of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features

- Effectiveness and safety of a mumps containing vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps cases from 2002 to 2017: A meta-analysis

- Low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin predict an increased breast cancer risk and its underlying molecular mechanisms

- A case of Trousseau syndrome: Screening, detection and complication

- Application of the integrated airway humidification device enhances the humidification effect of the rabbit tracheotomy model

- Preparation of Cu2+/TA/HAP composite coating with anti-bacterial and osteogenic potential on 3D-printed porous Ti alloy scaffolds for orthopedic applications

- Aquaporin-8 promotes human dermal fibroblasts to counteract hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage: A novel target for management of skin aging

- Current research and evidence gaps on placental development in iron deficiency anemia

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2910829 in PDE4D is related to stroke susceptibility in Chinese populations: The results of a meta-analysis

- Pheochromocytoma-induced myocardial infarction: A case report

- Kaempferol regulates apoptosis and migration of neural stem cells to attenuate cerebral infarction by O‐GlcNAcylation of β-catenin

- Sirtuin 5 regulates acute myeloid leukemia cell viability and apoptosis by succinylation modification of glycine decarboxylase

- Apigenin 7-glucoside impedes hypoxia-induced malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells in a p16-dependent manner

- KAT2A changes the function of endometrial stromal cells via regulating the succinylation of ENO1

- Current state of research on copper complexes in the treatment of breast cancer

- Exploring antioxidant strategies in the pathogenesis of ALS

- Helicobacter pylori causes gastric dysbacteriosis in chronic gastritis patients

- IL-33/soluble ST2 axis is associated with radiation-induced cardiac injury

- The predictive value of serum NLR, SII, and OPNI for lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with internal mammary lymph nodes after thoracoscopic surgery

- Carrying SNP rs17506395 (T > G) in TP63 gene and CCR5Δ32 mutation associated with the occurrence of breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- P2X7 receptor: A receptor closely linked with sepsis-associated encephalopathy

- Probiotics for inflammatory bowel disease: Is there sufficient evidence?

- Identification of KDM4C as a gene conferring drug resistance in multiple myeloma

- Microbial perspective on the skin–gut axis and atopic dermatitis

- Thymosin α1 combined with XELOX improves immune function and reduces serum tumor markers in colorectal cancer patients after radical surgery

- Highly specific vaginal microbiome signature for gynecological cancers

- Sample size estimation for AQP4-IgG seropositive optic neuritis: Retinal damage detection by optical coherence tomography

- The effects of SDF-1 combined application with VEGF on femoral distraction osteogenesis in rats

- Fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles using alginate: In vitro and in vivo assessment of its administration effects with swimming exercise on diabetic rats

- Mitigating digestive disorders: Action mechanisms of Mediterranean herbal active compounds

- Distribution of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in Han and Uygur populations with breast cancer in Xinjiang, China

- VSP-2 attenuates secretion of inflammatory cytokines induced by LPS in BV2 cells by mediating the PPARγ/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Factors influencing spontaneous hypothermia after emergency trauma and the construction of a predictive model

- Long-term administration of morphine specifically alters the level of protein expression in different brain regions and affects the redox state

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technology in the etiological diagnosis of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis

- Clinical diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of neurodyspepsia syndrome using intelligent medicine

- Case report: Successful bronchoscopic interventional treatment of endobronchial leiomyomas

- Preliminary investigation into the genetic etiology of short stature in children through whole exon sequencing of the core family

- Cystic adenomyoma of the uterus: Case report and literature review

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a drug delivery mechanism

- Dynamic changes in autophagy activity in different degrees of pulmonary fibrosis in mice

- Vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes: Big data insights

- Lactate-induced IGF1R protein lactylation promotes proliferation and metabolic reprogramming of lung cancer cells

- Meta-analysis on the efficacy of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to treat malignant lymphoma

- Mitochondrial DNA drives neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN signaling pathway in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain mice

- Application value of artificial intelligence algorithm-based magnetic resonance multi-sequence imaging in staging diagnosis of cervical cancer

- Embedded monitoring system and teaching of artificial intelligence online drug component recognition

- Investigation into the association of FNDC1 and ADAMTS12 gene expression with plumage coloration in Muscovy ducks

- Yak meat content in feed and its impact on the growth of rats

- A rare case of Richter transformation with breast involvement: A case report and literature review

- First report of Nocardia wallacei infection in an immunocompetent patient in Zhejiang province

- Rhodococcus equi and Brucella pulmonary mass in immunocompetent: A case report and literature review

- Downregulation of RIP3 ameliorates the left ventricular mechanics and function after myocardial infarction via modulating NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway

- Evaluation of the role of some non-enzymatic antioxidants among Iraqi patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- The role of Phafin proteins in cell signaling pathways and diseases

- Ten-year anemia as initial manifestation of Castleman disease in the abdominal cavity: A case report

- Coexistence of hereditary spherocytosis with SPTB P.Trp1150 gene variant and Gilbert syndrome: A case report and literature review

- Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells

- Exploratory evaluation supported by experimental and modeling approaches of Inula viscosa root extract as a potent corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in a 1 M HCl solution

- Imaging manifestations of ductal adenoma of the breast: A case report

- Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects

- Isomangiferin promotes the migration and osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- Prognostic value and microenvironmental crosstalk of exosome-related signatures in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive breast cancer

- Circular RNAs as potential biomarkers for male severe sepsis

- Knockdown of Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits growth and glycolysis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

- The expression and biological role of complement C1s in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- A novel GNAS mutation in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a with articular flexion deformity: A case report

- Predictive value of serum magnesium levels for prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing EGFR-TKI therapy

- HSPB1 alleviates acute-on-chronic liver failure via the P53/Bax pathway

- IgG4-related disease complicated by PLA2R-associated membranous nephropathy: A case report

- Baculovirus-mediated endostatin and angiostatin activation of autophagy through the AMPK/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Metformin mitigates osteoarthritis progression by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and enhancing chondrocyte autophagy

- Evaluation of the activity of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial vaginosis

- Atypical presentation of γ/δ mycosis fungoides with an unusual phenotype and SOCS1 mutation

- Analysis of the microecological mechanism of diabetic kidney disease based on the theory of “gut–kidney axis”: A systematic review

- Omega-3 fatty acids prevent gestational diabetes mellitus via modulation of lipid metabolism

- Refractory hypertension complicated with Turner syndrome: A case report

- Interaction of ncRNAs and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: Implications for osteosarcoma

- Association of low attenuation area scores with pulmonary function and clinical prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Long non-coding RNAs in bone formation: Key regulators and therapeutic prospects

- The deubiquitinating enzyme USP35 regulates the stability of NRF2 protein

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as potential diagnostic markers for rebleeding in patients with esophagogastric variceal bleeding

- G protein-coupled receptor 1 participating in the mechanism of mediating gestational diabetes mellitus by phosphorylating the AKT pathway

- LL37-mtDNA regulates viability, apoptosis, inflammation, and autophagy in lipopolysaccharide-treated RLE-6TN cells by targeting Hsp90aa1

- The analgesic effect of paeoniflorin: A focused review

- Chemical composition’s effect on Solanum nigrum Linn.’s antioxidant capacity and erythrocyte protection: Bioactive components and molecular docking analysis

- Knockdown of HCK promotes HREC cell viability and inner blood–retinal barrier integrity by regulating the AMPK signaling pathway

- The role of rapamycin in the PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway in mitophagy in podocytes

- Laryngeal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Report of four cases and review of the literature

- Clinical value of macrogenome next-generation sequencing on infections

- Overview of dendritic cells and related pathways in autoimmune uveitis

- TAK-242 alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inhibiting pyroptosis and TLR4/CaMKII/NLRP3 pathway

- Hypomethylation in promoters of PGC-1α involved in exercise-driven skeletal muscular alterations in old age

- Profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from effluents of Kolladiba and Debark hospitals

- The expression and clinical significance of syncytin-1 in serum exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- A histomorphometric study to evaluate the therapeutic effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on the kidneys infected with Plasmodium chabaudi

- PGRMC1 and PAQR4 are promising molecular targets for a rare subtype of ovarian cancer

- Analysis of MDA, SOD, TAOC, MNCV, SNCV, and TSS scores in patients with diabetes peripheral neuropathy

- SLIT3 deficiency promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by modulating UBE2C/WNT signaling

- The relationship between TMCO1 and CALR in the pathological characteristics of prostate cancer and its effect on the metastasis of prostate cancer cells

- Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is a potential target for enhancing the chemosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PHB2 alleviates retinal pigment epithelium cell fibrosis by suppressing the AGE–RAGE pathway

- Anti-γ-aminobutyric acid-B receptor autoimmune encephalitis with syncope as the initial symptom: Case report and literature review

- Comparative analysis of chloroplast genome of Lonicera japonica cv. Damaohua

- Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells regulate glutathione metabolism depending on the ERK–Nrf2–HO-1 signal pathway to repair phosphoramide mustard-induced ovarian cancer cells

- Electroacupuncture on GB acupoints improves osteoporosis via the estradiol–PI3K–Akt signaling pathway

- Renalase protects against podocyte injury by inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy

- Review: Dicranostigma leptopodum: A peculiar plant of Papaveraceae

- Combination effect of flavonoids attenuates lung cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting the STAT3 and FAK signaling pathway

- Renal microangiopathy and immune complex glomerulonephritis induced by anti-tumour agents: A case report

- Correlation analysis of AVPR1a and AVPR2 with abnormal water and sodium and potassium metabolism in rats

- Gastrointestinal health anti-diarrheal mixture relieves spleen deficiency-induced diarrhea through regulating gut microbiota

- Myriad factors and pathways influencing tumor radiotherapy resistance

- Exploring the effects of culture conditions on Yapsin (YPS) gene expression in Nakaseomyces glabratus

- Screening of prognostic core genes based on cell–cell interaction in the peripheral blood of patients with sepsis

- Coagulation factor II thrombin receptor as a promising biomarker in breast cancer management

- Ileocecal mucinous carcinoma misdiagnosed as incarcerated hernia: A case report

- Methyltransferase like 13 promotes malignant behaviors of bladder cancer cells through targeting PI3K/ATK signaling pathway

- The debate between electricity and heat, efficacy and safety of irreversible electroporation and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of liver cancer: A meta-analysis

- ZAG promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition by promoting lipid synthesis

- Baicalein inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and mitigates placental inflammation and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Impact of SWCNT-conjugated senna leaf extract on breast cancer cells: A potential apoptotic therapeutic strategy

- MFAP5 inhibits the malignant progression of endometrial cancer cells in vitro

- Major ozonated autohemotherapy promoted functional recovery following spinal cord injury in adult rats via the inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation

- Axodendritic targeting of TAU and MAP2 and microtubule polarization in iPSC-derived versus SH-SY5Y-derived human neurons

- Differential expression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and Toll-like receptor/nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathways in experimental obesity Wistar rat model

- The therapeutic potential of targeting Oncostatin M and the interleukin-6 family in retinal diseases: A comprehensive review

- BA inhibits LPS-stimulated inflammatory response and apoptosis in human middle ear epithelial cells by regulating the Nf-Kb/Iκbα axis

- Role of circRMRP and circRPL27 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Investigating the role of hyperexpressed HCN1 in inducing myocardial infarction through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Characterization of phenolic compounds and evaluation of anti-diabetic potential in Cannabis sativa L. seeds: In vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies

- Quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis of breast Ki67 based on artificial intelligence

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Screening of different growth conditions of Bacillus subtilis isolated from membrane-less microbial fuel cell toward antimicrobial activity profiling

- Degradation of a mixture of 13 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by commercial effective microorganisms

- Evaluation of the impact of two citrus plants on the variation of Panonychus citri (Acari: Tetranychidae) and beneficial phytoseiid mites

- Prediction of present and future distribution areas of Juniperus drupacea Labill and determination of ethnobotany properties in Antalya Province, Türkiye

- Population genetics of Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) in the northwest Pacific Ocean via GBS sequencing

- A comparative analysis of dendrometric, macromorphological, and micromorphological characteristics of Pistacia atlantica subsp. atlantica and Pistacia terebinthus in the middle Atlas region of Morocco

- Macrofungal sporocarp community in the lichen Scots pine forests

- Assessing the proximate compositions of indigenous forage species in Yemen’s pastoral rangelands

- Food Science

- Gut microbiota changes associated with low-carbohydrate diet intervention for obesity

- Reexamination of Aspergillus cristatus phylogeny in dark tea: Characteristics of the mitochondrial genome

- Differences in the flavonoid composition of the leaves, fruits, and branches of mulberry are distinguished based on a plant metabolomics approach

- Investigating the impact of wet rendering (solventless method) on PUFA-rich oil from catfish (Clarias magur) viscera

- Non-linear associations between cardiovascular metabolic indices and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study in the US population (2017–2020)

- Knockdown of USP7 alleviates atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice by regulating EZH2 expression

- Utility of dairy microbiome as a tool for authentication and traceability

- Agriculture

- Enhancing faba bean (Vicia faba L.) productivity through establishing the area-specific fertilizer rate recommendation in southwest Ethiopia

- Impact of novel herbicide based on synthetic auxins and ALS inhibitor on weed control

- Perspectives of pteridophytes microbiome for bioremediation in agricultural applications

- Fertilizer application parameters for drip-irrigated peanut based on the fertilizer effect function established from a “3414” field trial

- Improving the productivity and profitability of maize (Zea mays L.) using optimum blended inorganic fertilization

- Application of leaf multispectral analyzer in comparison to hyperspectral device to assess the diversity of spectral reflectance indices in wheat genotypes

- Animal Sciences

- Knockdown of ANP32E inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth and glycolysis by regulating the AKT/mTOR pathway

- Development of a detection chip for major pathogenic drug-resistant genes and drug targets in bovine respiratory system diseases

- Exploration of the genetic influence of MYOT and MB genes on the plumage coloration of Muscovy ducks

- Transcriptome analysis of adipose tissue in grazing cattle: Identifying key regulators of fat metabolism

- Comparison of nutritional value of the wild and cultivated spiny loaches at three growth stages

- Transcriptomic analysis of liver immune response in Chinese spiny frog (Quasipaa spinosa) infected with Proteus mirabilis

- Disruption of BCAA degradation is a critical characteristic of diabetic cardiomyopathy revealed by integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis

- Plant Sciences

- Effect of long-term in-row branch covering on soil microorganisms in pear orchards

- Photosynthetic physiological characteristics, growth performance, and element concentrations reveal the calcicole–calcifuge behaviors of three Camellia species

- Transcriptome analysis reveals the mechanism of NaHCO3 promoting tobacco leaf maturation

- Bioinformatics, expression analysis, and functional verification of allene oxide synthase gene HvnAOS1 and HvnAOS2 in qingke

- Water, nitrogen, and phosphorus coupling improves gray jujube fruit quality and yield

- Improving grape fruit quality through soil conditioner: Insights from RNA-seq analysis of Cabernet Sauvignon roots

- Role of Embinin in the reabsorption of nucleus pulposus in lumbar disc herniation: Promotion of nucleus pulposus neovascularization and apoptosis of nucleus pulposus cells

- Revealing the effects of amino acid, organic acid, and phytohormones on the germination of tomato seeds under salinity stress

- Combined effects of nitrogen fertilizer and biochar on the growth, yield, and quality of pepper

- Comprehensive phytochemical and toxicological analysis of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.) fractions

- Impact of “3414” fertilization on the yield and quality of greenhouse tomatoes

- Exploring the coupling mode of water and fertilizer for improving growth, fruit quality, and yield of the pear in the arid region

- Metagenomic analysis of endophytic bacteria in seed potato (Solanum tuberosum)

- Antibacterial, antifungal, and phytochemical properties of Salsola kali ethanolic extract

- Exploring the hepatoprotective properties of citronellol: In vitro and in silico studies on ethanol-induced damage in HepG2 cells

- Enhanced osmotic dehydration of watermelon rind using honey–sucrose solutions: A study on pre-treatment efficacy and mass transfer kinetics

- Effects of exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide on photosynthetic traits of 53 cowpea varieties under NaCl stress

- Comparative transcriptome analysis of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings in response to copper stress

- An optimization method for measuring the stomata in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) under multiple abiotic stresses

- Fosinopril inhibits Ang II-induced VSMC proliferation, phenotype transformation, migration, and oxidative stress through the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Salsola imbricata methanolic extract and its phytochemical characterization

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Absorbable calcium and phosphorus bioactive membranes promote bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells osteogenic differentiation for bone regeneration

- New advances in protein engineering for industrial applications: Key takeaways

- An overview of the production and use of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin

- Research progress of nanoparticles in diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Bioelectrochemical biosensors for water quality assessment and wastewater monitoring

- PEI/MMNs@LNA-542 nanoparticles alleviate ICU-acquired weakness through targeted autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial protection

- Unleashing of cytotoxic effects of thymoquinone-bovine serum albumin nanoparticles on A549 lung cancer cells

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM”

- Erratum to “Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation”

- Retraction

- Retraction to “MiR-223-3p regulates cell viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting RHOB”

- Retraction to “A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis”

- Special Issue on Advances in Neurodegenerative Disease Research and Treatment

- Transplantation of human neural stem cell prevents symptomatic motor behavior disability in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease

- Special Issue on Multi-omics

- Inflammasome complex genes with clinical relevance suggest potential as therapeutic targets for anti-tumor drugs in clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- Gastroesophageal varices in primary biliary cholangitis with anti-centromere antibody positivity: Early onset?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Constitutive and evoked release of ATP in adult mouse olfactory epithelium

- LARP1 knockdown inhibits cultured gastric carcinoma cell cycle progression and metastatic behavior

- PEGylated porcine–human recombinant uricase: A novel fusion protein with improved efficacy and safety for the treatment of hyperuricemia and renal complications

- Research progress on ocular complications caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus and the function of tears and blepharons

- The role and mechanism of esketamine in preventing and treating remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia based on the NMDA receptor–CaMKII pathway

- Brucella infection combined with Nocardia infection: A case report and literature review

- Detection of serum interleukin-18 level and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and its clinical significance

- Ang-1, Ang-2, and Tie2 are diagnostic biomarkers for Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematous

- PTTG1 induces pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and promotes aerobic glycolysis by regulating c-myc

- Role of serum B-cell-activating factor and interleukin-17 as biomarkers in the classification of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features

- Effectiveness and safety of a mumps containing vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps cases from 2002 to 2017: A meta-analysis

- Low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin predict an increased breast cancer risk and its underlying molecular mechanisms

- A case of Trousseau syndrome: Screening, detection and complication

- Application of the integrated airway humidification device enhances the humidification effect of the rabbit tracheotomy model

- Preparation of Cu2+/TA/HAP composite coating with anti-bacterial and osteogenic potential on 3D-printed porous Ti alloy scaffolds for orthopedic applications

- Aquaporin-8 promotes human dermal fibroblasts to counteract hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage: A novel target for management of skin aging

- Current research and evidence gaps on placental development in iron deficiency anemia

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2910829 in PDE4D is related to stroke susceptibility in Chinese populations: The results of a meta-analysis

- Pheochromocytoma-induced myocardial infarction: A case report

- Kaempferol regulates apoptosis and migration of neural stem cells to attenuate cerebral infarction by O‐GlcNAcylation of β-catenin

- Sirtuin 5 regulates acute myeloid leukemia cell viability and apoptosis by succinylation modification of glycine decarboxylase

- Apigenin 7-glucoside impedes hypoxia-induced malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells in a p16-dependent manner

- KAT2A changes the function of endometrial stromal cells via regulating the succinylation of ENO1

- Current state of research on copper complexes in the treatment of breast cancer

- Exploring antioxidant strategies in the pathogenesis of ALS

- Helicobacter pylori causes gastric dysbacteriosis in chronic gastritis patients

- IL-33/soluble ST2 axis is associated with radiation-induced cardiac injury

- The predictive value of serum NLR, SII, and OPNI for lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with internal mammary lymph nodes after thoracoscopic surgery

- Carrying SNP rs17506395 (T > G) in TP63 gene and CCR5Δ32 mutation associated with the occurrence of breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- P2X7 receptor: A receptor closely linked with sepsis-associated encephalopathy

- Probiotics for inflammatory bowel disease: Is there sufficient evidence?

- Identification of KDM4C as a gene conferring drug resistance in multiple myeloma

- Microbial perspective on the skin–gut axis and atopic dermatitis

- Thymosin α1 combined with XELOX improves immune function and reduces serum tumor markers in colorectal cancer patients after radical surgery

- Highly specific vaginal microbiome signature for gynecological cancers

- Sample size estimation for AQP4-IgG seropositive optic neuritis: Retinal damage detection by optical coherence tomography

- The effects of SDF-1 combined application with VEGF on femoral distraction osteogenesis in rats

- Fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles using alginate: In vitro and in vivo assessment of its administration effects with swimming exercise on diabetic rats

- Mitigating digestive disorders: Action mechanisms of Mediterranean herbal active compounds

- Distribution of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in Han and Uygur populations with breast cancer in Xinjiang, China

- VSP-2 attenuates secretion of inflammatory cytokines induced by LPS in BV2 cells by mediating the PPARγ/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Factors influencing spontaneous hypothermia after emergency trauma and the construction of a predictive model

- Long-term administration of morphine specifically alters the level of protein expression in different brain regions and affects the redox state

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technology in the etiological diagnosis of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis

- Clinical diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of neurodyspepsia syndrome using intelligent medicine

- Case report: Successful bronchoscopic interventional treatment of endobronchial leiomyomas

- Preliminary investigation into the genetic etiology of short stature in children through whole exon sequencing of the core family

- Cystic adenomyoma of the uterus: Case report and literature review

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a drug delivery mechanism

- Dynamic changes in autophagy activity in different degrees of pulmonary fibrosis in mice

- Vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes: Big data insights

- Lactate-induced IGF1R protein lactylation promotes proliferation and metabolic reprogramming of lung cancer cells

- Meta-analysis on the efficacy of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to treat malignant lymphoma

- Mitochondrial DNA drives neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN signaling pathway in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain mice

- Application value of artificial intelligence algorithm-based magnetic resonance multi-sequence imaging in staging diagnosis of cervical cancer

- Embedded monitoring system and teaching of artificial intelligence online drug component recognition

- Investigation into the association of FNDC1 and ADAMTS12 gene expression with plumage coloration in Muscovy ducks

- Yak meat content in feed and its impact on the growth of rats

- A rare case of Richter transformation with breast involvement: A case report and literature review

- First report of Nocardia wallacei infection in an immunocompetent patient in Zhejiang province

- Rhodococcus equi and Brucella pulmonary mass in immunocompetent: A case report and literature review

- Downregulation of RIP3 ameliorates the left ventricular mechanics and function after myocardial infarction via modulating NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway

- Evaluation of the role of some non-enzymatic antioxidants among Iraqi patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- The role of Phafin proteins in cell signaling pathways and diseases

- Ten-year anemia as initial manifestation of Castleman disease in the abdominal cavity: A case report

- Coexistence of hereditary spherocytosis with SPTB P.Trp1150 gene variant and Gilbert syndrome: A case report and literature review

- Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells

- Exploratory evaluation supported by experimental and modeling approaches of Inula viscosa root extract as a potent corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in a 1 M HCl solution

- Imaging manifestations of ductal adenoma of the breast: A case report

- Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects

- Isomangiferin promotes the migration and osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- Prognostic value and microenvironmental crosstalk of exosome-related signatures in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive breast cancer

- Circular RNAs as potential biomarkers for male severe sepsis

- Knockdown of Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits growth and glycolysis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

- The expression and biological role of complement C1s in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- A novel GNAS mutation in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a with articular flexion deformity: A case report

- Predictive value of serum magnesium levels for prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing EGFR-TKI therapy

- HSPB1 alleviates acute-on-chronic liver failure via the P53/Bax pathway

- IgG4-related disease complicated by PLA2R-associated membranous nephropathy: A case report

- Baculovirus-mediated endostatin and angiostatin activation of autophagy through the AMPK/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Metformin mitigates osteoarthritis progression by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and enhancing chondrocyte autophagy

- Evaluation of the activity of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial vaginosis

- Atypical presentation of γ/δ mycosis fungoides with an unusual phenotype and SOCS1 mutation

- Analysis of the microecological mechanism of diabetic kidney disease based on the theory of “gut–kidney axis”: A systematic review

- Omega-3 fatty acids prevent gestational diabetes mellitus via modulation of lipid metabolism

- Refractory hypertension complicated with Turner syndrome: A case report

- Interaction of ncRNAs and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: Implications for osteosarcoma

- Association of low attenuation area scores with pulmonary function and clinical prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Long non-coding RNAs in bone formation: Key regulators and therapeutic prospects

- The deubiquitinating enzyme USP35 regulates the stability of NRF2 protein

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as potential diagnostic markers for rebleeding in patients with esophagogastric variceal bleeding

- G protein-coupled receptor 1 participating in the mechanism of mediating gestational diabetes mellitus by phosphorylating the AKT pathway

- LL37-mtDNA regulates viability, apoptosis, inflammation, and autophagy in lipopolysaccharide-treated RLE-6TN cells by targeting Hsp90aa1

- The analgesic effect of paeoniflorin: A focused review

- Chemical composition’s effect on Solanum nigrum Linn.’s antioxidant capacity and erythrocyte protection: Bioactive components and molecular docking analysis

- Knockdown of HCK promotes HREC cell viability and inner blood–retinal barrier integrity by regulating the AMPK signaling pathway

- The role of rapamycin in the PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway in mitophagy in podocytes

- Laryngeal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Report of four cases and review of the literature

- Clinical value of macrogenome next-generation sequencing on infections

- Overview of dendritic cells and related pathways in autoimmune uveitis

- TAK-242 alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inhibiting pyroptosis and TLR4/CaMKII/NLRP3 pathway

- Hypomethylation in promoters of PGC-1α involved in exercise-driven skeletal muscular alterations in old age

- Profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from effluents of Kolladiba and Debark hospitals

- The expression and clinical significance of syncytin-1 in serum exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- A histomorphometric study to evaluate the therapeutic effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on the kidneys infected with Plasmodium chabaudi

- PGRMC1 and PAQR4 are promising molecular targets for a rare subtype of ovarian cancer

- Analysis of MDA, SOD, TAOC, MNCV, SNCV, and TSS scores in patients with diabetes peripheral neuropathy

- SLIT3 deficiency promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by modulating UBE2C/WNT signaling

- The relationship between TMCO1 and CALR in the pathological characteristics of prostate cancer and its effect on the metastasis of prostate cancer cells

- Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is a potential target for enhancing the chemosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PHB2 alleviates retinal pigment epithelium cell fibrosis by suppressing the AGE–RAGE pathway

- Anti-γ-aminobutyric acid-B receptor autoimmune encephalitis with syncope as the initial symptom: Case report and literature review

- Comparative analysis of chloroplast genome of Lonicera japonica cv. Damaohua

- Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells regulate glutathione metabolism depending on the ERK–Nrf2–HO-1 signal pathway to repair phosphoramide mustard-induced ovarian cancer cells

- Electroacupuncture on GB acupoints improves osteoporosis via the estradiol–PI3K–Akt signaling pathway

- Renalase protects against podocyte injury by inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy

- Review: Dicranostigma leptopodum: A peculiar plant of Papaveraceae

- Combination effect of flavonoids attenuates lung cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting the STAT3 and FAK signaling pathway

- Renal microangiopathy and immune complex glomerulonephritis induced by anti-tumour agents: A case report

- Correlation analysis of AVPR1a and AVPR2 with abnormal water and sodium and potassium metabolism in rats

- Gastrointestinal health anti-diarrheal mixture relieves spleen deficiency-induced diarrhea through regulating gut microbiota

- Myriad factors and pathways influencing tumor radiotherapy resistance

- Exploring the effects of culture conditions on Yapsin (YPS) gene expression in Nakaseomyces glabratus

- Screening of prognostic core genes based on cell–cell interaction in the peripheral blood of patients with sepsis

- Coagulation factor II thrombin receptor as a promising biomarker in breast cancer management

- Ileocecal mucinous carcinoma misdiagnosed as incarcerated hernia: A case report

- Methyltransferase like 13 promotes malignant behaviors of bladder cancer cells through targeting PI3K/ATK signaling pathway

- The debate between electricity and heat, efficacy and safety of irreversible electroporation and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of liver cancer: A meta-analysis

- ZAG promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition by promoting lipid synthesis

- Baicalein inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and mitigates placental inflammation and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Impact of SWCNT-conjugated senna leaf extract on breast cancer cells: A potential apoptotic therapeutic strategy

- MFAP5 inhibits the malignant progression of endometrial cancer cells in vitro

- Major ozonated autohemotherapy promoted functional recovery following spinal cord injury in adult rats via the inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation

- Axodendritic targeting of TAU and MAP2 and microtubule polarization in iPSC-derived versus SH-SY5Y-derived human neurons

- Differential expression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and Toll-like receptor/nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathways in experimental obesity Wistar rat model

- The therapeutic potential of targeting Oncostatin M and the interleukin-6 family in retinal diseases: A comprehensive review

- BA inhibits LPS-stimulated inflammatory response and apoptosis in human middle ear epithelial cells by regulating the Nf-Kb/Iκbα axis

- Role of circRMRP and circRPL27 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Investigating the role of hyperexpressed HCN1 in inducing myocardial infarction through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Characterization of phenolic compounds and evaluation of anti-diabetic potential in Cannabis sativa L. seeds: In vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies

- Quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis of breast Ki67 based on artificial intelligence

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Screening of different growth conditions of Bacillus subtilis isolated from membrane-less microbial fuel cell toward antimicrobial activity profiling

- Degradation of a mixture of 13 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by commercial effective microorganisms

- Evaluation of the impact of two citrus plants on the variation of Panonychus citri (Acari: Tetranychidae) and beneficial phytoseiid mites

- Prediction of present and future distribution areas of Juniperus drupacea Labill and determination of ethnobotany properties in Antalya Province, Türkiye

- Population genetics of Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) in the northwest Pacific Ocean via GBS sequencing

- A comparative analysis of dendrometric, macromorphological, and micromorphological characteristics of Pistacia atlantica subsp. atlantica and Pistacia terebinthus in the middle Atlas region of Morocco

- Macrofungal sporocarp community in the lichen Scots pine forests

- Assessing the proximate compositions of indigenous forage species in Yemen’s pastoral rangelands

- Food Science

- Gut microbiota changes associated with low-carbohydrate diet intervention for obesity

- Reexamination of Aspergillus cristatus phylogeny in dark tea: Characteristics of the mitochondrial genome

- Differences in the flavonoid composition of the leaves, fruits, and branches of mulberry are distinguished based on a plant metabolomics approach