Abstract

Emerging evidence has figured that serum conversion rate of mumps is a crucial link of mumps disease. Nevertheless, a rising number of mumps outbreaks caused our attention and studies examining the serum conversion cases were conducted in small samples previously; this meta-analysis was conducted to assess the immunogenicity and safety of a mumps containing vaccine (MuCV) before 2019. We identified a total of 17 studies from the year of 2002–2017. In the case–control studies, the vaccine effectiveness (VE) of MuCV in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps was 68% (odds risk: 0.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14−0.70) while in the cohort studies and randomised control trials, 58% (relative risk [RR]: 0.42; 95% CI, 0.26−0.69). Similar intervals of effectiveness rates were found during non-outbreak periods compared with outbreak periods (VE: 66%; RR: 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18−0.68 versus VE: 49%; RR: 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21−1.27). In addition, the MuCV group with two and three doses did not show enhanced laboratory-confirmed mumps than one dose (VE: 58%; RR: 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20−0.88 versus VE: 65%, RR: 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20−0.61) for the reason of the overlap of 95% CI. MuCV had comparable effectiveness comparing non-outbreak and outbreak period, one dose, and two or three doses. MuCV displayed acceptable adverse event profiles.

1 Introduction

Mumps is an acute respiratory infection caused by mumps virus infection of the parotid gland [1]. Mumps is highly transmissible as a common childhood viral disease and is also prevalent in both teenagers and young adults. Mumps should be a global concern, especially in China due to the considerable number of mumps cases [2]. Previous studies have reported the highest incidences of mumps in China in 2011 and 2012, with the incidence 33.9/100,000 and 35.6/100,000 [2]. Mumps is a self-limited disease that is mild in most cases but has serious complications, including meningitis and orchitis [3]. Examination of laboratory-confirmed mumps is an important indicator of exposure to the mumps virus.

Mumps is a vaccine-preventable disease. Widespread use of mumps containing vaccine (MuCV) has dramatically decreased the incidence of mumps. Mumps population immunity depends on the widespread use of MuCV [1]. Immunization with a MuCV is recommended by the World Health Organization, and the widespread use of MuCV has led to a significant decline in the incidence of mumps in several countries. MuCV represents a monovalent vaccine but can also be used in combination with other vaccines, such as the measles–mumps–rubella vaccine and multi-valent MuCVs, are commonly used. Occasional outbreaks continue to occur despite the increase in populations vaccinated with MuCV. Previous studies have examined laboratory-confirmed mumps during outbreak periods is regional and from small samples [4]. Thus, it is important to demonstrate adequate effectiveness to provide reassurance regarding the vaccine’s continued capability to confer protective immunity. However, studies clinically confirming mumps have been routinely carried out to measure the effectiveness of MuCV. Moreover, a certain level of latency and misdiagnosis has been observed in the clinical diagnosis of mumps. Most clinical studies consist of serum neutralization tests for mumps antibodies, which can measure the clinical and serologic responses to the MuCV rather than the true effectiveness of the MuCV. Some reports indicate that the diagnosis of mumps can be confirmed in the laboratory by the isolation of the mumps virus from specimens, which may reflect the effectiveness of MuCV [5,6,7].

The most common adverse events related to MuCV include injection-site pain, redness, and swelling; fever, vomiting, and drowsiness; and orchitis and skin infection. Serious adverse events (SAEs) have primarily consisted of skin infections and obstructive bronchitis and inflammatory diseases, which include orchitis, parotitis, meningitis, and pancreatitis [8,9,10]. Prevention of the adverse events associated with MuCV at different doses is becoming an increasingly critical global public health issue as an increased risk of safety events after doses of immunization have been reported [11,12]. Taken together, the present meta-analysis was conducted to synthetically assess the effectiveness and safety of MuCV in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps cases from 2002–2017.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Literature search

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library searchers databases for studies published from inception to May 3, 2019. Additionally, based on the importance of mumps in China, we used the China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases, as well as the theses and dissertations database in China. The inclusion criteria included case–control studies, cohort studies, and randomised control trials (RCTs). Key words or subject headings that were used consisted of “mumps-containing vaccine,” “effectiveness,” and “safety.” We scanned the relevant articles retrieved from the reference lists of the eligible articles. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis protocol was performed in the application of this systematic review and meta-analysis.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies assessing the effectiveness and safety of MuCV in participants from 2002 to 2017 were included for analysis. Included study types consisted of RCTs, cohort, descriptive, and case–control studies. Studies involving animal trials were excluded. Following the exclusion of 288 duplicates, abstracts and full texts were screened (Figure 1). Finally, the trial and control groups were extracted from the RCTs, the case and control groups from case–control studies, and the exposed and non-exposed groups from cohort studies. Some descriptive studies from which we could not identify two groups were excluded. For the RCTs, the control groups included placebo treatments, such as sodium chloride (4.5 mg), sucrose (12.5 mg), or a combination of these. Studies were excluded if they considered molecular biology, vaccine development, animal studies, and reviews, or were not published in either English or Chinese. Corresponding authors were contacted via email or telephone when critical data were defaulted in the original studies. Single studies associated with duplicate publications were considered one study and the publication with the most complete information was selected.

Selection of studies in our meta-analysis: a total of nine cohort studies, five RCTs, and three case–control studies were ultimately included in this meta-analysis.

2.3 Outcome assessment

The effectiveness of MuCV after the last dose was calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI) in each study. The secondary outcomes were adverse events. We primarily considered injection pain, redness, and swelling to be local symptoms. Fever, vomiting, and drowsiness were considered systematic reactions. The SAEs primarily consisted of inflammatory diseases, skin infections, and obstructive bronchitis. For a better understanding of the safety issues of MuCV, we compared different doses of MuCV.

2.4 Data extraction

All data were extracted by the lead author (LFH), and the second author (GBG) summarized the findings in Excel. Any disagreements in the data were resolved through discussion with the third author (PX). The following characteristics that might influence the MuCV effectiveness and safety were retrieved, including the first author, year of publication, study design, country, study period, intervention, type and valent of MuCV, coverage of MuCV, percentage of males, sample extracted from the participants, effectiveness confirmed index, and information sources. All of the above data were extracted into prepared templates.

2.5 Quality assessment

The Cochrane’s collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of biases was used to evaluate the biases in the RCTs (http://www.cochrane-handbook.org). We assessed seven biases including the selection bias, attribution bias, performance bias, reporting bias, detection bias, and other biases. In addition, the tool was used to assess the quality of the five RCTs. Regarding non-randomized experimental studies, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the quality of nine cohort studies and three case–control studies, including the four fields of selection, comparability, outcome, and total score (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp). We divided the NOS score into three levels: (1) high quality, score ≥7; (2) moderate quality, 4 ≤ score < 7; and (3) low quality, score <4 [13].

2.6 Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using Revman Manager 5.3 and Stata (version 12.0). We calculated the summary relative risk (RR) and odds risk (OR) estimates and 95% CIs as association measures for dichotomous results at the 5% level. Since the OR was used to evaluate the risk of disease in case–control studies, whereas RR was used to evaluate cohort studies and RCTs, we evaluated the risk of laboratory-confirmed mumps from the case–control studies, cohort studies, and RCTs, respectively.

The I 2 statistic was used to assess the level of heterogeneity across the included studies, with values of 25, 50, and 75%, which represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneities, respectively [14]. We initially performed the analyses using a random-effects model, which were re-adjusted using a fixed-effects model in case the I 2 value was lower than 50% and the P value was greater than 0.05. All of the statistical results were displayed as forest plots and tables.

We performed a subgroup analysis to compare the pooled association estimates and heterogeneity. The subgroup analyses were related to outbreak versus non-outbreak period, as well as one dose of MuCV versus two and three doses of MuCV. Since there is only one study that has reported three doses of MuCV making it impossible to compare to other studies, we evaluated the groups that received two and three doses group compared with the one dose group. Potential outliers were detected using a sensitivity analysis by removing each estimate one at a time and recalculating the pooled estimates. We also performed sensitivity analyses by restricting ORs or RRs adjusted for potential confounding factors. Begg’s funnel plots were used to assess publication bias. Since the present study consisted of a meta-analysis and the patients were not directly involved, patient consent was not required. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Medical University.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

The database search identified 622 articles containing relevant studies and clinical trial experiments. The most ineligible studies were excluded based on duplicates and abstracts and titles. Of the 622 selected articles, a total of 288 duplicates were excluded. Of the 334 screened records, 35 articles were excluded after scanning the titles. Of the 299 studies included for abstract screening, 196 articles were excluded after scanning the abstracts. Finally, 17 articles were included in our analysis after excluding 86 articles due to the full text. A total of nine cohort studies, five RCTs, and three case–control studies were ultimately included in this meta-analysis. The details of the selection process details are presented in Figure 1.

3.2 Description characteristics

The included studies were conducted in Belgium, Canada, China, Finland, Germany, Italy, Jordan, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, and Taiwan, China [5,15–30]. The total number of participants ranged from 20 to 3,808,130. The confirmed cases primarily occurred in children aged approximately 13 years old. Various valents and types of MuCV were used. The case definition intended for detecting laboratory-confirmed mumps was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by the presence of mumps virus RNA in all studies. As supplemental indexes, immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody was assessed in 15 studies, IgM antibody was assessed in 11 studies from patient samples (e.g., blood, oral fluid, and throat swabs). Nine studies used all the three methods described above. Regionally, the department of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was the most common resource for recording information regarding laboratory-confirmed mumps and a history of MuCV vaccination. The department of CDC included China, the United States, and Korea. The detailed characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in our meta-analysis

| Author (year) [ref] | Country | Study period | Intervention | Mumps-containing vaccine | Percent male | Sample extracted from participants | Laboratory confirmed index | Information sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valent | Type | ||||||||

| 5 RCTs | |||||||||

| Yan (2014) [25] | China | October 2012 to November 2012 | NA | NA | SP-A viral of the F-genotype | 43.00% | Throat swabs, blood | RNA, IgG | Chinese Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Vesikari (2010) [23] | Finland | October 2006 to March 2007 | Subcutaneous injection in deltoid region | Quadruvalent | Jeryl Lynn | 48.90% | Blood | RNA, IgG | NA |

| Deichmann (2015) [29] | Germany | NA | Muscle injection in deltoid region | Quadruvalent and hexavalent | Jeryl Lynn | NA | Blood | RNA, IgG, IgM | NA |

| Huang (2014) [27] | Taiwan | August 2010 to July 2012 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn | 51.11% | Blood | RNA, IgG, IgM | University laboratory |

| Klein et al. (2012) [20] | The United States | NA | Subcutaneous injection of left thigh | Quadruvalent | Jeryl Lynn | 50.62% | Blood | RNA, IgG, IgM | NA |

| 9 cohort studies | |||||||||

| Deeks et al. (2011) [15] | Canada | September 2009 to June 10 2010 | NA | Trivalent | NA | 72.40% | NA | RNA, IgM | The Ontario Immunization Record Information System database |

| Batayneh (2002) [22] | Jordan | 1999 to 2000 | NA | Trivalent | NA | 51.28% | Blood | RNA, IgG | The Department of Notifiable Communicable Diseases |

| Braeye (2014) [21] | Belgium | June 2012 to April 2013 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn | 53.00% | NA | RNA, IgG, IgM | The National Research Center |

| Ogbuanu (2012) [31] | The United States | January to February, 2010 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn | 43.99% | NA | RNA, IgG, IgM | The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York State Department of Health. |

| La (2017) [28] | Italy | 2009 to 2011 | NA | Quadruvalent | NA | 50.30% | NA | RNA, IgG, IgM | Vaccination register and hospital discharge records |

| Schaffzin et al. (2007) [19] | The United States | June to September, 2005 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn et al. | 47.00% | Blood | RNA, IgG, IgM | The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Dittrich (2011) [16] | The Netherlands | 2003 to 2006 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn | 51.34% | Oral fluid | RNA, IgG | The vaccination register |

| Kawano et al. (2015) [17] | The United States | September 2005 to December 2013 | NA | Monovalent | Hoshino strain | 62.50% | Blood and oral fluid | RNA, IgG | Laboratory medical records |

| Guo (2016) [30] | China | NA | NA | Trivalent | NA | 45.71% | Blood | RNA, IgG | NA |

| 3 case–control studies | |||||||||

| Castilla (2009) [17] | Spain | August 2006 to June 2008 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn | 48.00% | NA | RNA, IgG, IgM | The regional vaccination registry |

| Moon (2017) [26] | Korea | 2012 | NA | Trivalent | Jeryl Lynn or RIT 4385 strains | 100% | Blood | RNA, IgG, IgM | The Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Harling (2005) [25] | The United Kingdom | June 1998 to May 1999 | NA | Trivalent | NA | 37.61% | Oral fluid | RNA, IgM | The local Consultant in Communicable Disease Control |

Note. Ref: reference; SD: Standard difference; RCTs: Ran.

3.3 Vaccine effectiveness (VE) against laboratory-confirmed mumps

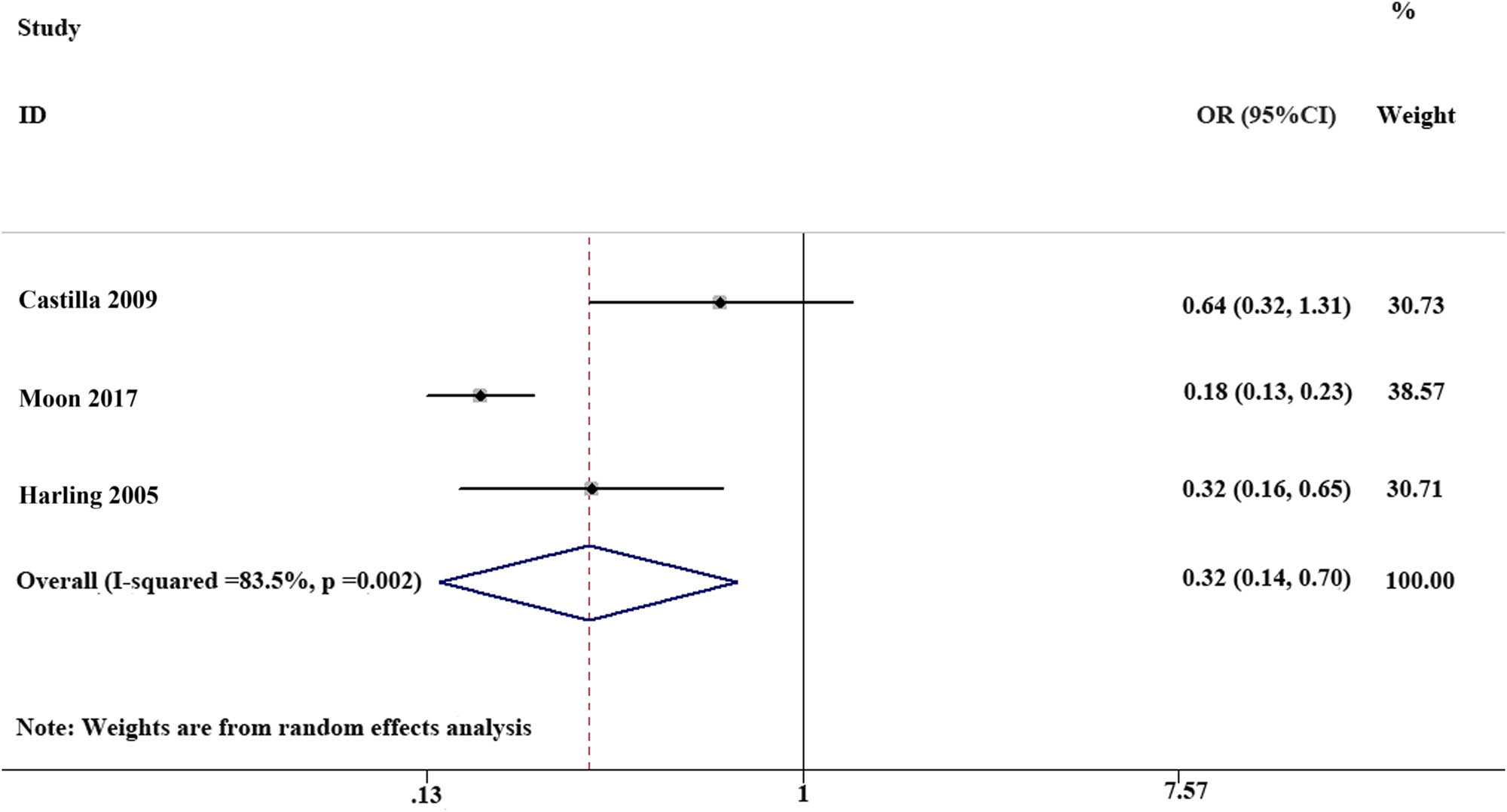

3.3.1 Effectiveness in case–control studies

Of the three case–control studies, the VE of MuCV in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps was 68% (OR: 0.32; 95% CI, 0.14−0.70). In total, of the 1,140 individuals in the laboratory-confirmed mumps group, 130 were MuCV vaccinated, and of the 1,258 individuals in the control group, 397 were vaccinated. The above comparison was conducted using a random-effects model (Figure 2).

The effectiveness of mumps containing vaccine (3 case–control studies): of the three case–control studies, the VE of MuCV in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps was 68%.

3.3.2 Effectiveness in cohort studies and RCTs

Of the nine cohort studies and five RCTs, we compared the mumps incidence rate between the vaccination group and the control group. The results showed that the overall VE for preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps was 58% (RR: 0.42; 95% CI, 0.26−0.69).

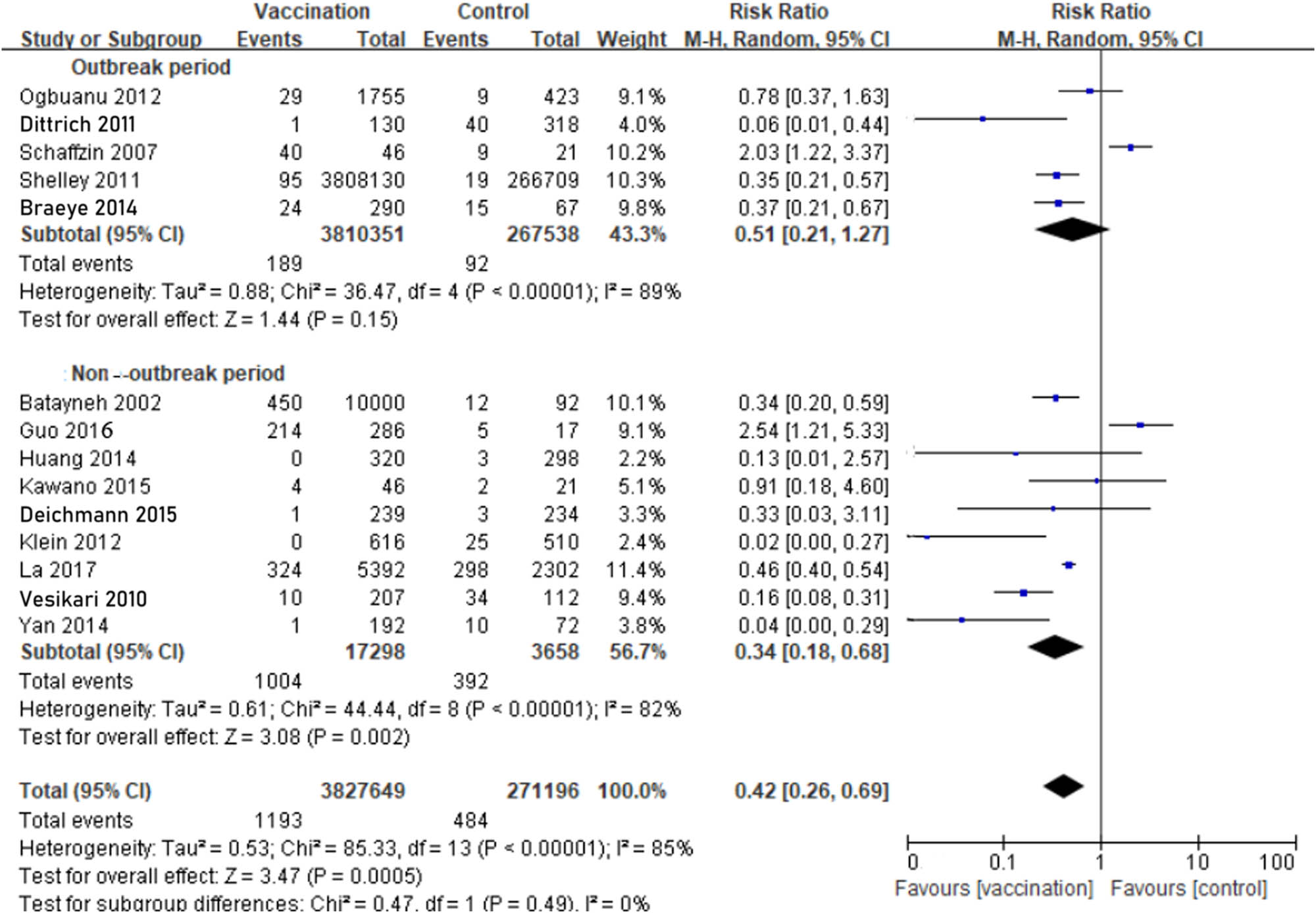

3.3.3 Effectiveness between the outbreak and non-outbreak period

During the outbreak period, we estimated the incidence was 0.50‱ in the MuCV vaccination group, which was calculated from 189 people diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed mumps among the 3,810,351 MuCV recipients. Moreover, the incidence was 3.44‱ in the control group, which was calculated from 92 people diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed mumps among the 267,538 non-MuCV recipients. The outbreak and non-outbreak periods were used as comparisons. During the outbreak period, the VE of MuCV was 49% (RR: 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21−1.27), whereas the VE during the non-outbreak period was 66% (RR: 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18−0.68). Although the pooled RRs showed that VE of MuCV during non-outbreak was superior than the outbreak period, the 95% CI was similar among the outbreak group and the non-outbreak group, which indicates that VE of MuCV during outbreak was no better than non-outbreak period. All three of the above comparisons were applied in a random-effects model (Figure 3).

Comparison between outbreak and non-outbreak period evaluating the effectiveness of mumps containing vaccine (9 cohort studies and 5 RCTs): during the outbreak period, the VE of MuCV was 49% (RR: 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21−1.27), whereas the VE during the non-outbreak period was 66% (RR: 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18−0.68).

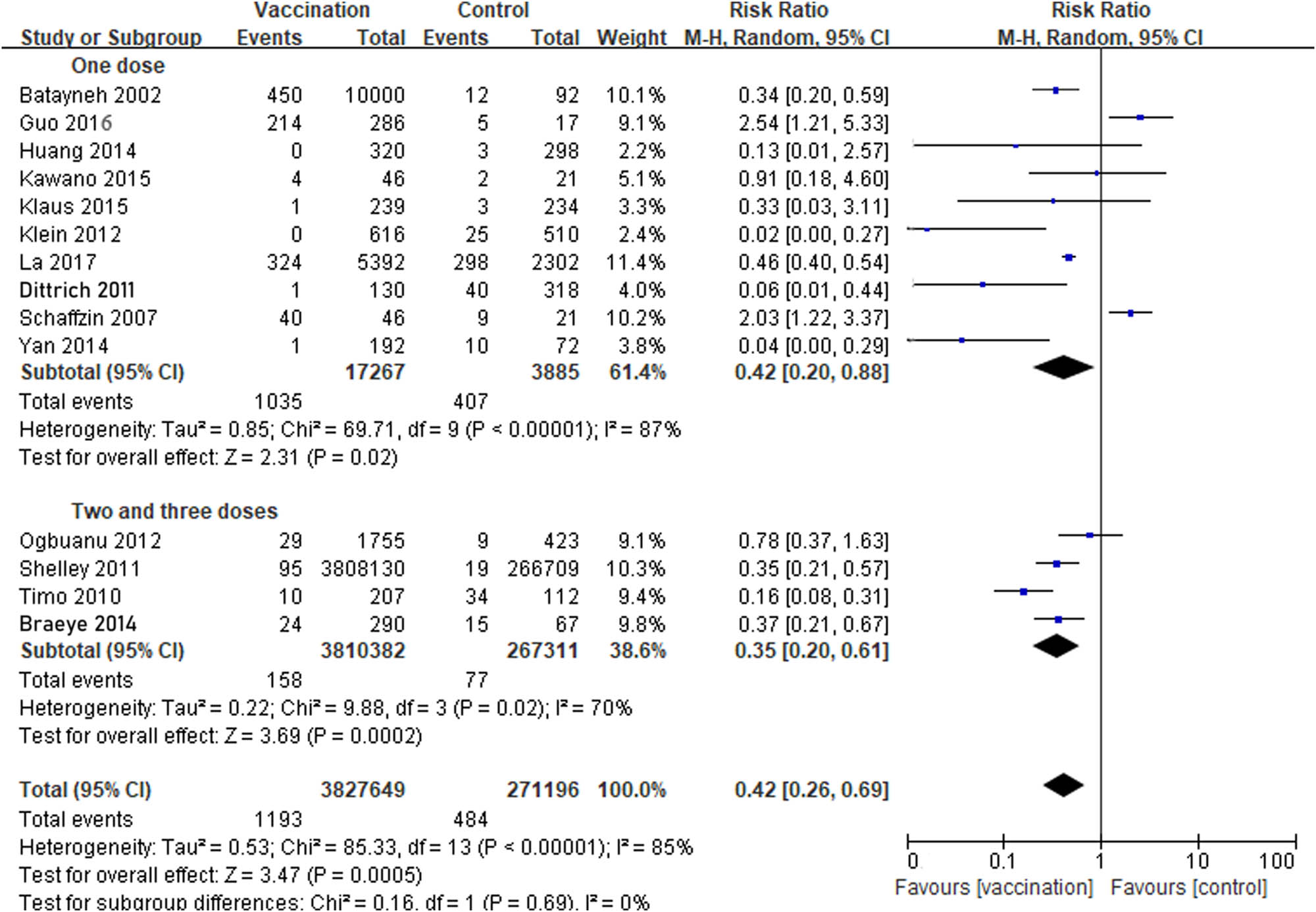

3.3.4 Effectiveness in one, two, and three doses

There were ten studies that reported one dose of MuCV, three studies that reported two doses, and one study that reported three doses. The results showed that the VE of one dose of MuCV was 58% (RR 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20−0.88), whereas two and three doses were 65% (RR 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20−0.61). However, the 95% CIs of the two subgroups showed an overlap, which indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between the two subgroups. All the above comparisons were applied in a random-effects model (Figure 4).

Comparison between one dose, two, and three doses evaluating the effectiveness of mumps containing vaccine (9 cohort studies and 5 RCTs): the results showed that the VE of one dose of MuCV was 58% (RR 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20−0.88), whereas two and three doses were 65% (RR 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20−0.61).

3.4 Safety

To assess safety, five RCTs and one cohort study added up to six studies that investigated adverse events. In most of the studies, local symptoms, systematic symptoms, or SAEs occurred during the first 15 days of the post-vaccination observation period. Redness and fever were the two most common symptoms. The incidence rate of two local symptoms and two systematic symptoms following two doses of MuCV was higher than that experienced following one dose, which was statistically different.

3.4.1 Local symptoms

The five RCTs and one cohort study reported 701 cases among 1,574 participants in the MuCV group and 248 cases among the 1,262 participants in the control group. All three symptoms occurred until 56 days post-vaccination. For injection-site pain, 25.71% of events associated with one dose of the MuCV were reported, which were higher than that of two doses. In addition, we found that two doses of MuCV statistically increased the risk of swelling and redness. There were insufficient data available to evaluate the other symptoms which were not depicted in Table S1.

3.4.2 Systematic symptoms

The number of systematic symptoms was 877 cases among the 1,335 participants in the MuCV group and 461 cases among the 1,028 participants in the control group. Statistical differences existed regarding fever (RR: 1.68; 95% CI, 1.36−2.08; I 2 = 0%) and drowsiness (RR: 1.63; 95% CI, 1.34−1.98; I 2 = 43%). Together with vomiting, all three of these symptoms showed that the incidence rate associated with two doses of MuCV were higher, although vomiting was not statistically significant.

3.4.3 SAEs

Four cases (0.97%) of skin infection and obstructive occurred after two doses of the MuCV vaccination. No cases of orchitis existed and there are no related fatal SAEs reported in any of the included studies. Nevertheless, the two symptoms were not statistically significant.

3.5 Quality and risk of bias assessment

Taken together, a total of eleven studies were of moderate quality and the other six studies were of high quality. In considering the five RCTs, the overall quality was good and indicated that the overall risk of bias was low (Figure S1). Except for detection and performance, bias primarily emerged as high risk of biases, the other five biases mostly emerged as low risk of biases. With regard to the nine cohort studies and three case–control studies, six studies were assigned as moderate quality (score of 6 for four studies and score of 5 for two studies) and the other six studies were assigned as high quality, as shown in Table S2 according to the NOS. The sensitivity analysis confirmed the credibility of this meta-analysis (Figure S2). The funnel plot displayed non-significant asymmetry (Begg’s test P > 0.05) both in the three case–control studies, nine cohort studies, and five RCTs (Figure S3).

4 Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that has evaluated the effectiveness of MuCV using laboratory diagnosis and reassessed the safety of MuCV. To our knowledge, the reasons for the increasing instances of mumps outbreaks are multifaceted. One significant possibility may be the decreasing effectiveness of the MuCV. Laboratory confirmation has been found to be of high value to diagnose mumps and decrease the possibility that laboratory confirmation could be the reason for the onset of mumps outbreaks [5,15–30]. Thus, evaluating the effectiveness and safety of MuCV for decreasing laboratory-confirmed mumps is of high value and there are an insufficient number of previously studied regional samples [4]. Our findings provide a reference for countries recording information pertaining to laboratory confirmation and may reflect a need to re-evaluate the precise VE and safety of MuCV.

In general, there are insufficient data regarding whether MuCV is effective for laboratory-confirmed mumps and related concerns continue to increase. Instead of laboratory-confirmed mumps, a large body of evidence has been derived from cases of clinical mumps [32]. Therefore, biases and residual confounding factors provide alternative explanations for the incorrect VE of MuCV. The results of this study show that the effectiveness of MuCV in cohort studies and RCTs was lower for laboratory-confirmed mumps (VEs ranging from 49 to 66% with a pooled estimates of 58%) compared to approximately 66.4% after an individual’s final vaccine dose as reported as clinical-confirmed cases by previous analyses [33,34]. A possible explanation for this is that the studies included in our meta-analysis focused on laboratory-confirmed cases rather than clinical-confirmed cases. As a result, a greater number of mumps cases were found than previously reported studies, most of which focused on clinically diagnosed mumps. Sabine et al. indicated that for every one case of clinical vaccinated mumps, at least three asymptomatic cases can be expected and at higher risk of mumps virus infection [16]. On the other hand, a significant decrease in the voluntarily MuCV-vaccinated population explains the reduction of VEs to some extent [35]. Those with immunity against mumps (i.e., those with laboratory-confirmed cases) reflect the true level of herd immunity [36]. In addition, the proportion of the overall VE was lower than the suggested threshold of 90−92% to interrupt transmission [35].

In reducing the cases of laboratory-confirmed mumps, the results showed that MuCV during the non-outbreak period was more effective than that during the outbreak period (VE = 49% during the outbreak period versus 66% during the non-outbreak period). However, the 95% CIs indicate similar VEs between the two periods, which differed from that of previous studies. To our knowledge, the outbreaks were usually associated with higher MuCV effectiveness and the degree of protection increased at the beginning of 20th century [37]. The similarity of the VE intervals illustrated a decreased frequency of protection in the population exposed to mumps virus during outbreak period. The key contributing factor to this phenomenon has been proposed to be waning immunity, which was potentially due to immune escape resulting from various valents and types of MuCV over a long period. Waning immunity indicated a waning of vaccine-induced immunity, which increased the susceptibility to infection with the mumps virus since a mismatch existed between the vaccine strain and a predominant circulating wild-type strain of the mumps virus [38,39]. In addition, cases of reinfection have been reported among individuals who have had naturally acquired mumps, suggesting that MuCV may not be effective in some individuals and VE of MuCV might be overvalued [38]. From this perspective, waning immunity would exert an influence on decreasing the robustness of vaccine-derived immunity and exponentially increase the probability of mumps virus exposure during the outbreak period. In fact, most mumps cases in recent outbreaks have been reported among young adults, and some researchers estimated that may be due to waning immunity towards MuCV [40,41].

Compared with only one dose of the vaccine in 17,267 individuals, the participants vaccinated with two doses reached 3,808,627 resulting from an immunization with two doses of MuCV as part of a childhood vaccination program in many vaccinated countries by 2005 [40,41]. Consistent with most studies, the point estimate of the pooled VE for two and three doses (VE = 65%) was higher than that of one dose (VE = 58%). Specifically, the pooled analysis reported an impressive remission rate of VEs of MuCV in laboratory-confirmed mumps. Effectiveness of one dose of MuCV was shown from 66 to 96%, whereas the effectiveness of two doses and three does was observed from 86 to 99% according to previous studies [42–45]. However, the 95% CI of the two subgroups indicated that the effectiveness did not differ significantly between two or three doses of MuCV and one dose of MuCV. One possible explanation for this finding may be that many individuals who reported being vaccinated with one dose may have been vaccinated with another dose and boosted by exposure via an increasing occurrence of outbreaks, but their history of vaccination has been incorrectly recorded [31]. In addition, Deeks et al. found that when vaccine supplies were limited, administering a single dose of the vaccine may avert more cases and deaths than a standard two-dose campaign [15]. Furthermore, there were only three studies involving a two doses MuCV vaccine regimen. Widespread third-dose intervention of MuCV can be extremely time consuming and resource intensive; thus, we could extract only one study involving a three-dose MuCV study design [32,46]. To date, there are fewer studies that investigated two and three doses of MuCV compared to that involving one dose of MuCV [43]. Thus, our results may be associated with limitations due to the lack of studies on two and three doses of MuCV. In general, MuCV was found to be effective for laboratory-confirmed mumps and which doses of MuCV should be recommended as being in need of further research.

Some confounding factors that were identified may explain our insignificant findings. For the detection of laboratory-confirmed mumps, three methods were used. Qualitative RNA expression by PCR was a determinant factor, while the levels of IgG and IgM were considered supplemental factors. While some studies used all three methods, others used only one of the three. Although PCR was found to be significant for identifying mumps virus infection, the data were not directly provided. Therefore, we either contacted the authors or indirectly obtained the data through calculations. Thus, our task was a difficult and time-consuming process. The evaluation of VE by cautiously confirming PCR test results may provide better understanding of the precise VE of the MuCV. There have been no relevant placebo RCTs included in this analysis which is another possible confounding factor. It is considered unethical to withhold MuCV, particularly from those at the highest risk of developing severe illness due to mumps.

Safety issues concerning post-vaccination symptoms associated with different doses of MuCV are a concern [47]. In addition to injection-site pain, the incidence of two local symptoms and three systematic symptoms increased with additional doses of MuCV. Redness, swelling, and drowsiness were the most frequently reported symptoms common among the majority of the studies [10,12]. Compared with previous studies, the higher reporting of adverse events may be due to the increasing number of MuCV-vaccinated individuals or the availability of a variety of new MuCV [48,49]. Rare SAEs and the lack of mortality related to MuCV indicate that MuCV was generally and unequivocally safe for laboratory-confirmed mumps in line with what has been reported globally.

With respect to the limitations associated with our analysis, including moderate to high heterogeneity, the present results should be interpreted with caution. First, there have been few studies conducted on MuCV vaccination and evaluated by laboratory confirmation. In some studies, the data were limited, making data extraction difficult. Thus, we were required to contact the corresponding authors. Moreover, some of the studies included in this analysis were observational studies and could have led to detection bias.

5 Conclusion

Our results suggest that MuCV provides lower protection against laboratory-confirmed mumps. MuCV showed similar effectiveness during an outbreak period and a non-outbreak period. Moreover, MuCV did not show increased effectiveness with the delivery of two and three doses rather than one dose. MuCV exhibited acceptable adverse event profiles. The confirmation of laboratory-confirmed mumps will help to more precisely assess the VE and safety of MuCV.

Acknowledgments

We thank International Science Editing (http://www.internationalscienceediting.com) for editing this manuscript.

-

Funding information: Our study was supported by the Quality Engineering Project of Higher Education Institutions, Anhui Province, China [grant number: 2022jnds042] and Institutions of Higher Education Scientific Research Project (Key Natural Science Project) of Anhui Province in 2022 [grant number: 2022AH052879].

-

Author contributions: PX: manuscript writing, design, proofreading; BGG: data analysis, literature search, figures; LFH: manuscript writing, tables.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Li D, Zhang H, You N, Chen Z, Yang X, Zhang H, et al. Mumps serological surveillance following 10 years of a one-dose mumps-containing-vaccine policy in Fujian Province, China. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics. 2022;18(6):e2096375, 1–7.10.1080/21645515.2022.2096375Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Zhang D, Guo Y, Rutherford S, Qi C, Wang X, Wang P, et al. The relationship between meteorological factors and mumps based on Boosted regression tree model. The. Science of the total environment. 2019;695:133758.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133758Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Dong W, Zhang K, Gong Z, Luo T, Li J, Wang X, et al. Infectious diseases in children and adolescents in China: analysis of national surveillance data from 2008 to 2017. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2022;369:m1043.10.1136/bmj.m1043Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Sartorius B, Penttinen P, Nilsson J, Johansen K, Jönsson K, Arneborn M, et al. An outbreak of mumps in Sweden, February-April 2004. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(9):191–3.10.2807/esm.10.09.00559-enSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Maillet M, Bouvat E, Robert N, Baccard-Longère M, Morel-Baccard C, Morand P, et al. Mumps outbreak and laboratory diagnosis. J Clin Virol. 2015;62:14–9.10.1016/j.jcv.2014.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Utz JP, Houk VN, Alling DW. Clinical and laboratory studies of mumps. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:1283–6.10.1056/NEJM196406112702404Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Weibel RE, Carlson AJ, Villarejos VM, Buynak EB, Mclean AA, Hilleman MR. Clinical and laboratory studies of combined live measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines using the RA 27/3 rubella virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1980;165(2):323–6.10.3181/00379727-165-40979Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Gee S, O’Flanagan D, Fitzgerald M, Cotter S. Mumps in Ireland, 2004-2008. Euro Surveill. 2008;13(18).10.2807/ese.13.18.18857-enSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Demicheli V, Rivetti A, Debalini MG, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD004407.10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Sukumaran L, Mcneil MM, Moro PL, Lewis PW, Winiecki SK, Shimabukuro TT. Adverse events following measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine in adults reported to the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS), 2003-2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(10):e58–65.10.1093/cid/civ061Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Lee CY, Tang RB, Huang FY, Tang H, Huang LM, Bock HL. A new measles mumps rubella (MMR) vaccine: a randomized comparative trial for assessing the reactogenicity and immunogenicity of three consecutive production lots and comparison with a widely used MMR vaccine in measles primed children. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6(3):202–9.10.1016/S1201-9712(02)90112-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Hviid A, Rubin S, Muhlemann K. Mumps. Lancet. 2008;371(9616):932–44.10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.10.1007/s10654-010-9491-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Deeks SL, Lim GH, Simpson MA, Gagné L, Gubbay J, Kristjanson E, et al. An assessment of mumps vaccine effectiveness by dose during an outbreak in Canada. CMAJ. 2011;183(9):1014–20.10.1503/cmaj.101371Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Dittrich S, Hahné S, van Lier A, Kohl R, Boot H, Koopmans M, et al. Assessment of serological evidence for mumps virus infection in vaccinated children. Vaccine. 2011;29(49):9271–5.10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.072Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Kawano Y, Suzuki M, Kawada J, Kimura H, Kamei H, Ohnishi Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of immunization with live-attenuated and inactivated vaccines for pediatric liver transplantation recipients. Vaccine. 2015;33(12):1440–5.10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.075Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Castilla J, García Cenoz M, Arriazu M, Fernández-Alonso M, Martínez-Artola V, Etxeberria J, et al. Effectiveness of Jeryl Lynn-containing vaccine in Spanish children. Vaccine. 2009;27(15):2089–93.10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Schaffzin JK, Pollock L, Schulte C, Henry K, Dayan G, Blog D, et al. Effectiveness of previous mumps vaccination during a summer camp outbreak. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e862–8.10.1542/peds.2006-3451Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Klein NP, Shepard J, Bedell L, Odrljin T, Dull P. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine administered concomitantly with measles, mumps, rubella, varicella vaccine in healthy toddlers. Vaccine. 2012;30(26):3929–36.10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.080Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Braeye T, Linina I, De Roy R, Hutse V, Wauters M, Cox P, et al. Mumps increase in Flanders, Belgium, 2012-2013: results from temporary mandatory notification and a cohort study among university students. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4393–8.10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.069Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Batayneh N, Bdour S. Mumps: immune status of adults and epidemiology as a necessary background for choice of vaccination strategy in Jordan. Apmis. 2002;110(7-8):528–34.10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.11007803.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Lindblad N, Korhonen T, Lommel P, Willems P, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a booster dose of the 10-valent pneumococcal nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine coadministered with measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine in children aged 12 to 16 months. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(6):e47–56.10.1097/INF.0b013e3181dffabfSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Liang Y, Ma J, Li C, Chen Y, Liu L, Liao Y, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a live attenuated mumps vaccine: a phase I clinical trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(5):1382–90.10.4161/hv.28334Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Harling R, White JM, Ramsay ME, Macsween KF, Bosch CVD. The effectiveness of the mumps component of the MMR vaccine: a case control study. Vaccine. 2005;23(31):4070–4.10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Moon JY, Jung J, Huh K. Universal measles-mumps-rubella vaccination to new recruits and the incidence of mumps in the military. Vaccine. 2017;35(32):3913–6.10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Huang LM, Lin TY, Chiu CH, Chiu NC, Chen PY, Yeh SJ, et al. Concomitant administration of live attenuated Japanese encephalitis chimeric virus vaccine (JE-CV) and measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine: Randomized study in toddlers in Taiwan. Vaccine. 2014;32(41):5363–9.10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.085Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] La Torre G, Saulle R, Unim B, Meggiolaro A, Barbato A, Mannocci A, et al. The effectiveness of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination in the prevention of pediatric hospitalizations for targeted and untargeted infections: A retrospective cohort study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(8):1879–83.10.1080/21645515.2017.1330733Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Deichmann KA, Ferrera G, Tran C, Thomas S, Eymin C, Baudin M. Immunogenicity and safety of a combined measles, mumps, rubella and varicella live vaccine (ProQuad®) administered concomitantly with a booster dose of a hexavalent vaccine in 12–23-month-old infants. Vaccine. 2015;33(20):2379–86.10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.070Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Guo Q, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Xin XM. Analysis on detection results of mumps antibody levels in 3 to 15 years old students in high-tech industrial development of Urumqi, China. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care. 2016;24(08):853–5.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ogbuanu IU, Kutty PK, Hudson JM, Blog D, Abedi GR, Goodell S, et al. Impact of a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine on a mumps outbreak. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1567–74.10.1542/peds.2012-0177Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Cardemil CV, Dahl RM, James L, Wannemuehler K, Gary HE, Shah M, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of MMR vaccine for mumps outbreak control. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(10):947–56.10.1056/NEJMoa1703309Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Anderson RM, May RM. Immunisation and herd immunity. Lancet. 1990;335(8690):641–5.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Utz JP, Kasel JA, Cramblett HG, Szwed CF, Parrott RH. Clinical and laboratory studies of mumps. I. Laboratory diagnosis by tissue-culture technics. N Engl J Med. 1957;257(11):497–502.10.1056/NEJM195709122571103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Lo NC, Hotez PJ. Public health and economic consequences of vaccine hesitancy for measles in the United States. Jama Pediatr. 2017;171(9):887–92.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1695Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Anderson RM, May RM. Immunisation and herd immunity. Lancet (London, England). 1990;335(8690):641–5.10.1016/0140-6736(90)90420-ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Centers FDCA. Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children--United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48(12):243–8.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Beleni A, Borgmann S. Mumps in the vaccination age: Global epidemiology and the situation in Germany. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2018;15(8):1618.10.3390/ijerph15081618Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Association between vaccine refusal and vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States: A Review of measles and pertussis. JAMA. 2016;315(11):1149–58.10.1001/jama.2016.1353Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Vygen S, Fischer A, Meurice L, Mounchetrou Njoya I, Gregoris M, Ndiaye B, et al. Waning immunity against mumps in vaccinated young adults, France 2013. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(10):30156.10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.10.30156Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Cohen C, White JM, Savage EJ, Glynn JR, Choi Y, Andrews N, et al. Vaccine effectiveness estimates, 2004-2005 mumps outbreak, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(1):12–7.10.3201/eid1301.060649Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Aasheim ET, Inns T, Trindall A, Emmett L, Brown KE, Williams CJ, et al. Outbreak of mumps in a school setting, United Kingdom, 2013. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(8):2446–9.10.4161/hv.29484Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Povey M, Henry O, Riise Bergsaker MA, Chlibek R, Esposito S, Flodmark CE, et al. Protection against varicella with two doses of combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine or one dose of monovalent varicella vaccine: 10-year follow-up of a phase 3 multicentre, observer-blind, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(3):287–97.10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30716-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Assessment of mumps-containing vaccine effectiveness during an outbreak: Importance to introduce the 2-dose schedule for China.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Barrabeig I, Antón A, Torner N, Pumarola T, Costa J, Domínguez À. Mumps: MMR vaccination and genetic diversity of mumps virus, 2007-2011 in Catalonia, Spain. Bmc Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):954.10.1186/s12879-019-4496-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Maglione MA, Das L, Raaen L, Smith A, Chari R, Newberry S, et al. Safety of vaccines used for routine immunization of U.S. children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):325–37.10.1542/peds.2014-1079Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Afzal MA, Minor PD, Schild GC. Clinical safety issues of measles, mumps and rubella vaccines. B World Health Organ. 2000;78(2):199–204.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Perez-Vilar S, Weibel D, Sturkenboom M, Black S, Maure C, Castro JL, et al. Enhancing global vaccine pharmacovigilance: Proof-of-concept study on aseptic meningitis and immune thrombocytopenic purpura following measles-mumps containing vaccination. Vaccine. 2018;36(3):347–54.10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Berry AA, Abu-Elyazeed R, Diaz-Perez C, Mufson MA, Harrison CJ, Leonardi M, et al. Two-year antibody persistence in children vaccinated at 12-15 months with a measles-mumps-rubella virus vaccine without human serum albumin. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2017;13(7):1516–22.10.1080/21645515.2017.1309486Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Constitutive and evoked release of ATP in adult mouse olfactory epithelium

- LARP1 knockdown inhibits cultured gastric carcinoma cell cycle progression and metastatic behavior

- PEGylated porcine–human recombinant uricase: A novel fusion protein with improved efficacy and safety for the treatment of hyperuricemia and renal complications

- Research progress on ocular complications caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus and the function of tears and blepharons

- The role and mechanism of esketamine in preventing and treating remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia based on the NMDA receptor–CaMKII pathway

- Brucella infection combined with Nocardia infection: A case report and literature review

- Detection of serum interleukin-18 level and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and its clinical significance

- Ang-1, Ang-2, and Tie2 are diagnostic biomarkers for Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematous

- PTTG1 induces pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and promotes aerobic glycolysis by regulating c-myc

- Role of serum B-cell-activating factor and interleukin-17 as biomarkers in the classification of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features

- Effectiveness and safety of a mumps containing vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps cases from 2002 to 2017: A meta-analysis

- Low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin predict an increased breast cancer risk and its underlying molecular mechanisms

- A case of Trousseau syndrome: Screening, detection and complication

- Application of the integrated airway humidification device enhances the humidification effect of the rabbit tracheotomy model

- Preparation of Cu2+/TA/HAP composite coating with anti-bacterial and osteogenic potential on 3D-printed porous Ti alloy scaffolds for orthopedic applications

- Aquaporin-8 promotes human dermal fibroblasts to counteract hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage: A novel target for management of skin aging

- Current research and evidence gaps on placental development in iron deficiency anemia

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2910829 in PDE4D is related to stroke susceptibility in Chinese populations: The results of a meta-analysis

- Pheochromocytoma-induced myocardial infarction: A case report

- Kaempferol regulates apoptosis and migration of neural stem cells to attenuate cerebral infarction by O‐GlcNAcylation of β-catenin

- Sirtuin 5 regulates acute myeloid leukemia cell viability and apoptosis by succinylation modification of glycine decarboxylase

- Apigenin 7-glucoside impedes hypoxia-induced malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells in a p16-dependent manner

- KAT2A changes the function of endometrial stromal cells via regulating the succinylation of ENO1

- Current state of research on copper complexes in the treatment of breast cancer

- Exploring antioxidant strategies in the pathogenesis of ALS

- Helicobacter pylori causes gastric dysbacteriosis in chronic gastritis patients

- IL-33/soluble ST2 axis is associated with radiation-induced cardiac injury

- The predictive value of serum NLR, SII, and OPNI for lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with internal mammary lymph nodes after thoracoscopic surgery

- Carrying SNP rs17506395 (T > G) in TP63 gene and CCR5Δ32 mutation associated with the occurrence of breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- P2X7 receptor: A receptor closely linked with sepsis-associated encephalopathy

- Probiotics for inflammatory bowel disease: Is there sufficient evidence?

- Identification of KDM4C as a gene conferring drug resistance in multiple myeloma

- Microbial perspective on the skin–gut axis and atopic dermatitis

- Thymosin α1 combined with XELOX improves immune function and reduces serum tumor markers in colorectal cancer patients after radical surgery

- Highly specific vaginal microbiome signature for gynecological cancers

- Sample size estimation for AQP4-IgG seropositive optic neuritis: Retinal damage detection by optical coherence tomography

- The effects of SDF-1 combined application with VEGF on femoral distraction osteogenesis in rats

- Fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles using alginate: In vitro and in vivo assessment of its administration effects with swimming exercise on diabetic rats

- Mitigating digestive disorders: Action mechanisms of Mediterranean herbal active compounds

- Distribution of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in Han and Uygur populations with breast cancer in Xinjiang, China

- VSP-2 attenuates secretion of inflammatory cytokines induced by LPS in BV2 cells by mediating the PPARγ/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Factors influencing spontaneous hypothermia after emergency trauma and the construction of a predictive model

- Long-term administration of morphine specifically alters the level of protein expression in different brain regions and affects the redox state

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technology in the etiological diagnosis of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis

- Clinical diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of neurodyspepsia syndrome using intelligent medicine

- Case report: Successful bronchoscopic interventional treatment of endobronchial leiomyomas

- Preliminary investigation into the genetic etiology of short stature in children through whole exon sequencing of the core family

- Cystic adenomyoma of the uterus: Case report and literature review

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a drug delivery mechanism

- Dynamic changes in autophagy activity in different degrees of pulmonary fibrosis in mice

- Vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes: Big data insights

- Lactate-induced IGF1R protein lactylation promotes proliferation and metabolic reprogramming of lung cancer cells

- Meta-analysis on the efficacy of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to treat malignant lymphoma

- Mitochondrial DNA drives neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN signaling pathway in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain mice

- Application value of artificial intelligence algorithm-based magnetic resonance multi-sequence imaging in staging diagnosis of cervical cancer

- Embedded monitoring system and teaching of artificial intelligence online drug component recognition

- Investigation into the association of FNDC1 and ADAMTS12 gene expression with plumage coloration in Muscovy ducks

- Yak meat content in feed and its impact on the growth of rats

- A rare case of Richter transformation with breast involvement: A case report and literature review

- First report of Nocardia wallacei infection in an immunocompetent patient in Zhejiang province

- Rhodococcus equi and Brucella pulmonary mass in immunocompetent: A case report and literature review

- Downregulation of RIP3 ameliorates the left ventricular mechanics and function after myocardial infarction via modulating NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway

- Evaluation of the role of some non-enzymatic antioxidants among Iraqi patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- The role of Phafin proteins in cell signaling pathways and diseases

- Ten-year anemia as initial manifestation of Castleman disease in the abdominal cavity: A case report

- Coexistence of hereditary spherocytosis with SPTB P.Trp1150 gene variant and Gilbert syndrome: A case report and literature review

- Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells

- Exploratory evaluation supported by experimental and modeling approaches of Inula viscosa root extract as a potent corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in a 1 M HCl solution

- Imaging manifestations of ductal adenoma of the breast: A case report

- Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects

- Isomangiferin promotes the migration and osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- Prognostic value and microenvironmental crosstalk of exosome-related signatures in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive breast cancer

- Circular RNAs as potential biomarkers for male severe sepsis

- Knockdown of Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits growth and glycolysis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

- The expression and biological role of complement C1s in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- A novel GNAS mutation in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a with articular flexion deformity: A case report

- Predictive value of serum magnesium levels for prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing EGFR-TKI therapy

- HSPB1 alleviates acute-on-chronic liver failure via the P53/Bax pathway

- IgG4-related disease complicated by PLA2R-associated membranous nephropathy: A case report

- Baculovirus-mediated endostatin and angiostatin activation of autophagy through the AMPK/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Metformin mitigates osteoarthritis progression by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and enhancing chondrocyte autophagy

- Evaluation of the activity of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial vaginosis

- Atypical presentation of γ/δ mycosis fungoides with an unusual phenotype and SOCS1 mutation

- Analysis of the microecological mechanism of diabetic kidney disease based on the theory of “gut–kidney axis”: A systematic review

- Omega-3 fatty acids prevent gestational diabetes mellitus via modulation of lipid metabolism

- Refractory hypertension complicated with Turner syndrome: A case report

- Interaction of ncRNAs and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: Implications for osteosarcoma

- Association of low attenuation area scores with pulmonary function and clinical prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Long non-coding RNAs in bone formation: Key regulators and therapeutic prospects

- The deubiquitinating enzyme USP35 regulates the stability of NRF2 protein

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as potential diagnostic markers for rebleeding in patients with esophagogastric variceal bleeding

- G protein-coupled receptor 1 participating in the mechanism of mediating gestational diabetes mellitus by phosphorylating the AKT pathway

- LL37-mtDNA regulates viability, apoptosis, inflammation, and autophagy in lipopolysaccharide-treated RLE-6TN cells by targeting Hsp90aa1

- The analgesic effect of paeoniflorin: A focused review

- Chemical composition’s effect on Solanum nigrum Linn.’s antioxidant capacity and erythrocyte protection: Bioactive components and molecular docking analysis

- Knockdown of HCK promotes HREC cell viability and inner blood–retinal barrier integrity by regulating the AMPK signaling pathway

- The role of rapamycin in the PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway in mitophagy in podocytes

- Laryngeal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Report of four cases and review of the literature

- Clinical value of macrogenome next-generation sequencing on infections

- Overview of dendritic cells and related pathways in autoimmune uveitis

- TAK-242 alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inhibiting pyroptosis and TLR4/CaMKII/NLRP3 pathway

- Hypomethylation in promoters of PGC-1α involved in exercise-driven skeletal muscular alterations in old age

- Profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from effluents of Kolladiba and Debark hospitals

- The expression and clinical significance of syncytin-1 in serum exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- A histomorphometric study to evaluate the therapeutic effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on the kidneys infected with Plasmodium chabaudi

- PGRMC1 and PAQR4 are promising molecular targets for a rare subtype of ovarian cancer

- Analysis of MDA, SOD, TAOC, MNCV, SNCV, and TSS scores in patients with diabetes peripheral neuropathy

- SLIT3 deficiency promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by modulating UBE2C/WNT signaling

- The relationship between TMCO1 and CALR in the pathological characteristics of prostate cancer and its effect on the metastasis of prostate cancer cells

- Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is a potential target for enhancing the chemosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PHB2 alleviates retinal pigment epithelium cell fibrosis by suppressing the AGE–RAGE pathway

- Anti-γ-aminobutyric acid-B receptor autoimmune encephalitis with syncope as the initial symptom: Case report and literature review

- Comparative analysis of chloroplast genome of Lonicera japonica cv. Damaohua

- Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells regulate glutathione metabolism depending on the ERK–Nrf2–HO-1 signal pathway to repair phosphoramide mustard-induced ovarian cancer cells

- Electroacupuncture on GB acupoints improves osteoporosis via the estradiol–PI3K–Akt signaling pathway

- Renalase protects against podocyte injury by inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy

- Review: Dicranostigma leptopodum: A peculiar plant of Papaveraceae

- Combination effect of flavonoids attenuates lung cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting the STAT3 and FAK signaling pathway

- Renal microangiopathy and immune complex glomerulonephritis induced by anti-tumour agents: A case report

- Correlation analysis of AVPR1a and AVPR2 with abnormal water and sodium and potassium metabolism in rats

- Gastrointestinal health anti-diarrheal mixture relieves spleen deficiency-induced diarrhea through regulating gut microbiota

- Myriad factors and pathways influencing tumor radiotherapy resistance

- Exploring the effects of culture conditions on Yapsin (YPS) gene expression in Nakaseomyces glabratus

- Screening of prognostic core genes based on cell–cell interaction in the peripheral blood of patients with sepsis

- Coagulation factor II thrombin receptor as a promising biomarker in breast cancer management

- Ileocecal mucinous carcinoma misdiagnosed as incarcerated hernia: A case report

- Methyltransferase like 13 promotes malignant behaviors of bladder cancer cells through targeting PI3K/ATK signaling pathway

- The debate between electricity and heat, efficacy and safety of irreversible electroporation and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of liver cancer: A meta-analysis

- ZAG promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition by promoting lipid synthesis

- Baicalein inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and mitigates placental inflammation and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Impact of SWCNT-conjugated senna leaf extract on breast cancer cells: A potential apoptotic therapeutic strategy

- MFAP5 inhibits the malignant progression of endometrial cancer cells in vitro

- Major ozonated autohemotherapy promoted functional recovery following spinal cord injury in adult rats via the inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation

- Axodendritic targeting of TAU and MAP2 and microtubule polarization in iPSC-derived versus SH-SY5Y-derived human neurons

- Differential expression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and Toll-like receptor/nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathways in experimental obesity Wistar rat model

- The therapeutic potential of targeting Oncostatin M and the interleukin-6 family in retinal diseases: A comprehensive review

- BA inhibits LPS-stimulated inflammatory response and apoptosis in human middle ear epithelial cells by regulating the Nf-Kb/Iκbα axis

- Role of circRMRP and circRPL27 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Investigating the role of hyperexpressed HCN1 in inducing myocardial infarction through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Characterization of phenolic compounds and evaluation of anti-diabetic potential in Cannabis sativa L. seeds: In vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies

- Quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis of breast Ki67 based on artificial intelligence

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Screening of different growth conditions of Bacillus subtilis isolated from membrane-less microbial fuel cell toward antimicrobial activity profiling

- Degradation of a mixture of 13 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by commercial effective microorganisms

- Evaluation of the impact of two citrus plants on the variation of Panonychus citri (Acari: Tetranychidae) and beneficial phytoseiid mites

- Prediction of present and future distribution areas of Juniperus drupacea Labill and determination of ethnobotany properties in Antalya Province, Türkiye

- Population genetics of Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) in the northwest Pacific Ocean via GBS sequencing

- A comparative analysis of dendrometric, macromorphological, and micromorphological characteristics of Pistacia atlantica subsp. atlantica and Pistacia terebinthus in the middle Atlas region of Morocco

- Macrofungal sporocarp community in the lichen Scots pine forests

- Assessing the proximate compositions of indigenous forage species in Yemen’s pastoral rangelands

- Food Science

- Gut microbiota changes associated with low-carbohydrate diet intervention for obesity

- Reexamination of Aspergillus cristatus phylogeny in dark tea: Characteristics of the mitochondrial genome

- Differences in the flavonoid composition of the leaves, fruits, and branches of mulberry are distinguished based on a plant metabolomics approach

- Investigating the impact of wet rendering (solventless method) on PUFA-rich oil from catfish (Clarias magur) viscera

- Non-linear associations between cardiovascular metabolic indices and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study in the US population (2017–2020)

- Knockdown of USP7 alleviates atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice by regulating EZH2 expression

- Utility of dairy microbiome as a tool for authentication and traceability

- Agriculture

- Enhancing faba bean (Vicia faba L.) productivity through establishing the area-specific fertilizer rate recommendation in southwest Ethiopia

- Impact of novel herbicide based on synthetic auxins and ALS inhibitor on weed control

- Perspectives of pteridophytes microbiome for bioremediation in agricultural applications

- Fertilizer application parameters for drip-irrigated peanut based on the fertilizer effect function established from a “3414” field trial

- Improving the productivity and profitability of maize (Zea mays L.) using optimum blended inorganic fertilization

- Application of leaf multispectral analyzer in comparison to hyperspectral device to assess the diversity of spectral reflectance indices in wheat genotypes

- Animal Sciences

- Knockdown of ANP32E inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth and glycolysis by regulating the AKT/mTOR pathway

- Development of a detection chip for major pathogenic drug-resistant genes and drug targets in bovine respiratory system diseases

- Exploration of the genetic influence of MYOT and MB genes on the plumage coloration of Muscovy ducks

- Transcriptome analysis of adipose tissue in grazing cattle: Identifying key regulators of fat metabolism

- Comparison of nutritional value of the wild and cultivated spiny loaches at three growth stages

- Transcriptomic analysis of liver immune response in Chinese spiny frog (Quasipaa spinosa) infected with Proteus mirabilis

- Disruption of BCAA degradation is a critical characteristic of diabetic cardiomyopathy revealed by integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis

- Plant Sciences

- Effect of long-term in-row branch covering on soil microorganisms in pear orchards

- Photosynthetic physiological characteristics, growth performance, and element concentrations reveal the calcicole–calcifuge behaviors of three Camellia species

- Transcriptome analysis reveals the mechanism of NaHCO3 promoting tobacco leaf maturation

- Bioinformatics, expression analysis, and functional verification of allene oxide synthase gene HvnAOS1 and HvnAOS2 in qingke

- Water, nitrogen, and phosphorus coupling improves gray jujube fruit quality and yield

- Improving grape fruit quality through soil conditioner: Insights from RNA-seq analysis of Cabernet Sauvignon roots

- Role of Embinin in the reabsorption of nucleus pulposus in lumbar disc herniation: Promotion of nucleus pulposus neovascularization and apoptosis of nucleus pulposus cells

- Revealing the effects of amino acid, organic acid, and phytohormones on the germination of tomato seeds under salinity stress

- Combined effects of nitrogen fertilizer and biochar on the growth, yield, and quality of pepper

- Comprehensive phytochemical and toxicological analysis of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.) fractions

- Impact of “3414” fertilization on the yield and quality of greenhouse tomatoes

- Exploring the coupling mode of water and fertilizer for improving growth, fruit quality, and yield of the pear in the arid region

- Metagenomic analysis of endophytic bacteria in seed potato (Solanum tuberosum)

- Antibacterial, antifungal, and phytochemical properties of Salsola kali ethanolic extract

- Exploring the hepatoprotective properties of citronellol: In vitro and in silico studies on ethanol-induced damage in HepG2 cells

- Enhanced osmotic dehydration of watermelon rind using honey–sucrose solutions: A study on pre-treatment efficacy and mass transfer kinetics

- Effects of exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide on photosynthetic traits of 53 cowpea varieties under NaCl stress

- Comparative transcriptome analysis of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings in response to copper stress

- An optimization method for measuring the stomata in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) under multiple abiotic stresses

- Fosinopril inhibits Ang II-induced VSMC proliferation, phenotype transformation, migration, and oxidative stress through the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Salsola imbricata methanolic extract and its phytochemical characterization

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Absorbable calcium and phosphorus bioactive membranes promote bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells osteogenic differentiation for bone regeneration

- New advances in protein engineering for industrial applications: Key takeaways

- An overview of the production and use of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin

- Research progress of nanoparticles in diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Bioelectrochemical biosensors for water quality assessment and wastewater monitoring

- PEI/MMNs@LNA-542 nanoparticles alleviate ICU-acquired weakness through targeted autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial protection

- Unleashing of cytotoxic effects of thymoquinone-bovine serum albumin nanoparticles on A549 lung cancer cells

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM”

- Erratum to “Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation”

- Retraction

- Retraction to “MiR-223-3p regulates cell viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting RHOB”

- Retraction to “A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis”

- Special Issue on Advances in Neurodegenerative Disease Research and Treatment

- Transplantation of human neural stem cell prevents symptomatic motor behavior disability in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease

- Special Issue on Multi-omics

- Inflammasome complex genes with clinical relevance suggest potential as therapeutic targets for anti-tumor drugs in clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- Gastroesophageal varices in primary biliary cholangitis with anti-centromere antibody positivity: Early onset?

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Constitutive and evoked release of ATP in adult mouse olfactory epithelium

- LARP1 knockdown inhibits cultured gastric carcinoma cell cycle progression and metastatic behavior

- PEGylated porcine–human recombinant uricase: A novel fusion protein with improved efficacy and safety for the treatment of hyperuricemia and renal complications

- Research progress on ocular complications caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus and the function of tears and blepharons

- The role and mechanism of esketamine in preventing and treating remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia based on the NMDA receptor–CaMKII pathway

- Brucella infection combined with Nocardia infection: A case report and literature review

- Detection of serum interleukin-18 level and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and its clinical significance

- Ang-1, Ang-2, and Tie2 are diagnostic biomarkers for Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematous

- PTTG1 induces pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and promotes aerobic glycolysis by regulating c-myc

- Role of serum B-cell-activating factor and interleukin-17 as biomarkers in the classification of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features

- Effectiveness and safety of a mumps containing vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed mumps cases from 2002 to 2017: A meta-analysis

- Low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin predict an increased breast cancer risk and its underlying molecular mechanisms

- A case of Trousseau syndrome: Screening, detection and complication

- Application of the integrated airway humidification device enhances the humidification effect of the rabbit tracheotomy model

- Preparation of Cu2+/TA/HAP composite coating with anti-bacterial and osteogenic potential on 3D-printed porous Ti alloy scaffolds for orthopedic applications

- Aquaporin-8 promotes human dermal fibroblasts to counteract hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage: A novel target for management of skin aging

- Current research and evidence gaps on placental development in iron deficiency anemia

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2910829 in PDE4D is related to stroke susceptibility in Chinese populations: The results of a meta-analysis

- Pheochromocytoma-induced myocardial infarction: A case report

- Kaempferol regulates apoptosis and migration of neural stem cells to attenuate cerebral infarction by O‐GlcNAcylation of β-catenin

- Sirtuin 5 regulates acute myeloid leukemia cell viability and apoptosis by succinylation modification of glycine decarboxylase

- Apigenin 7-glucoside impedes hypoxia-induced malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells in a p16-dependent manner

- KAT2A changes the function of endometrial stromal cells via regulating the succinylation of ENO1

- Current state of research on copper complexes in the treatment of breast cancer

- Exploring antioxidant strategies in the pathogenesis of ALS

- Helicobacter pylori causes gastric dysbacteriosis in chronic gastritis patients

- IL-33/soluble ST2 axis is associated with radiation-induced cardiac injury

- The predictive value of serum NLR, SII, and OPNI for lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with internal mammary lymph nodes after thoracoscopic surgery

- Carrying SNP rs17506395 (T > G) in TP63 gene and CCR5Δ32 mutation associated with the occurrence of breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- P2X7 receptor: A receptor closely linked with sepsis-associated encephalopathy

- Probiotics for inflammatory bowel disease: Is there sufficient evidence?

- Identification of KDM4C as a gene conferring drug resistance in multiple myeloma

- Microbial perspective on the skin–gut axis and atopic dermatitis

- Thymosin α1 combined with XELOX improves immune function and reduces serum tumor markers in colorectal cancer patients after radical surgery

- Highly specific vaginal microbiome signature for gynecological cancers

- Sample size estimation for AQP4-IgG seropositive optic neuritis: Retinal damage detection by optical coherence tomography

- The effects of SDF-1 combined application with VEGF on femoral distraction osteogenesis in rats

- Fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles using alginate: In vitro and in vivo assessment of its administration effects with swimming exercise on diabetic rats

- Mitigating digestive disorders: Action mechanisms of Mediterranean herbal active compounds

- Distribution of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in Han and Uygur populations with breast cancer in Xinjiang, China

- VSP-2 attenuates secretion of inflammatory cytokines induced by LPS in BV2 cells by mediating the PPARγ/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Factors influencing spontaneous hypothermia after emergency trauma and the construction of a predictive model

- Long-term administration of morphine specifically alters the level of protein expression in different brain regions and affects the redox state

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technology in the etiological diagnosis of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis

- Clinical diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of neurodyspepsia syndrome using intelligent medicine

- Case report: Successful bronchoscopic interventional treatment of endobronchial leiomyomas

- Preliminary investigation into the genetic etiology of short stature in children through whole exon sequencing of the core family

- Cystic adenomyoma of the uterus: Case report and literature review

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a drug delivery mechanism

- Dynamic changes in autophagy activity in different degrees of pulmonary fibrosis in mice

- Vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes: Big data insights

- Lactate-induced IGF1R protein lactylation promotes proliferation and metabolic reprogramming of lung cancer cells

- Meta-analysis on the efficacy of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to treat malignant lymphoma

- Mitochondrial DNA drives neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN signaling pathway in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain mice

- Application value of artificial intelligence algorithm-based magnetic resonance multi-sequence imaging in staging diagnosis of cervical cancer

- Embedded monitoring system and teaching of artificial intelligence online drug component recognition

- Investigation into the association of FNDC1 and ADAMTS12 gene expression with plumage coloration in Muscovy ducks

- Yak meat content in feed and its impact on the growth of rats

- A rare case of Richter transformation with breast involvement: A case report and literature review

- First report of Nocardia wallacei infection in an immunocompetent patient in Zhejiang province

- Rhodococcus equi and Brucella pulmonary mass in immunocompetent: A case report and literature review

- Downregulation of RIP3 ameliorates the left ventricular mechanics and function after myocardial infarction via modulating NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway

- Evaluation of the role of some non-enzymatic antioxidants among Iraqi patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- The role of Phafin proteins in cell signaling pathways and diseases

- Ten-year anemia as initial manifestation of Castleman disease in the abdominal cavity: A case report

- Coexistence of hereditary spherocytosis with SPTB P.Trp1150 gene variant and Gilbert syndrome: A case report and literature review

- Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells

- Exploratory evaluation supported by experimental and modeling approaches of Inula viscosa root extract as a potent corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in a 1 M HCl solution

- Imaging manifestations of ductal adenoma of the breast: A case report

- Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects

- Isomangiferin promotes the migration and osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- Prognostic value and microenvironmental crosstalk of exosome-related signatures in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive breast cancer

- Circular RNAs as potential biomarkers for male severe sepsis

- Knockdown of Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits growth and glycolysis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

- The expression and biological role of complement C1s in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- A novel GNAS mutation in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a with articular flexion deformity: A case report

- Predictive value of serum magnesium levels for prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing EGFR-TKI therapy

- HSPB1 alleviates acute-on-chronic liver failure via the P53/Bax pathway

- IgG4-related disease complicated by PLA2R-associated membranous nephropathy: A case report

- Baculovirus-mediated endostatin and angiostatin activation of autophagy through the AMPK/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Metformin mitigates osteoarthritis progression by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and enhancing chondrocyte autophagy

- Evaluation of the activity of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial vaginosis