Neuronutrition in autism spectrum disorders

-

Anastasiia Badaeva

, Giulia Malaguarnera

, Sergio Modafferi

, Antonio Trapanotto

, Francesca Fazzina

, Ursula M. Jacob

, Damiano Galimberti

, Caterina Gagliano

and Vittorio Calabrese

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition with increasing prevalence, often associated with oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation. This review explores the role of neuronutritions and polyphenols as potential therapeutic strategies for managing ASD. Neuronutrition focuses on bioactive dietary compounds that activate vitagenes, which are crucial genes involved in cellular stress response. Nutrients such as sulforaphane, acetyl-L-carnitine, and omega-3 fatty acids have shown promise in improving oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in ASD patients. Polyphenols, including resveratrol, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), luteolin, and curcumin, have demonstrated neuroprotective effects by reducing neuroinflammation and enhancing antioxidant defense. Both neuronutrients and polyphenols leverage hormesis, which is a biological response to mild stressors, to improve cellular resilience and brain health. Clinical studies support their potential in alleviating ASD symptoms, suggesting that targeted dietary interventions could complement conventional treatments. Further research is required to understand the long-term efficacy and mechanisms of these interventions for ASD management.

Introduction

Neuronutrition is an emerging interdisciplinary field that studies the effects of dietary components on neurological disorders by targeting key molecular mechanisms such as neuroinflammation, oxidative/nitrosative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, gut-brain axis disturbances, and neurotransmitter imbalances [1]. This emerging field combines insights from neuroscience, nutrition, and biochemistry to develop targeted dietary interventions for neurological disorders. Neuronutrition research aims to identify specific nutrients and bioactive compounds that can modulate brain function, and potentially prevent or alleviate neurological disorders. By focusing on the molecular mechanisms, it may be possible to develop personalized nutritional strategies that complement existing treatments and improve the outcomes of patients with various neurological conditions. Dietary components include proteins, carbohydrates, fats, prebiotics, and probiotics, all of which influence neurobiology, neurochemistry, cognition, and behavior [2]. Nutritional components, particularly dietary antioxidants, play a significant role in activating and regulating vitagenes, which are a group of genes involved in preserving cellular homeostasis during stressful conditions. They encode proteins such as heat shock proteins (Hsp), sirtuins, and thioredoxins, which are crucial for the cellular stress response system. Nutrients such as carnosic acid, resveratrol, sulforaphane, dimethyl fumarate, acetyl-L-carnitine, and carnosine have been shown to activate vitagenes, contributing to the upregulation of protective proteins and enhancing cellular stress tolerance and redox homeostasis [3]. Nutritional activation of vitagenes is crucial for mitigating oxidative stress, which is associated with aging and various neurodegenerative diseases.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social communication and restrictive and repetitive behaviors. In the United States, ASD has a prevalence rate of approximately 2.3 % among children aged 8 years and 2.2 % among adults [4]. Over the past decade, the prevalence of ASD has markedly increased, likely due to advancements in diagnostic criteria, enhanced screening methodologies, and increased public awareness and recognition of this disorder.

Review methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 2000 and June 2024. Search terms included combinations of “autism spectrum disorder,” “ASD,” “neuronutrition,” “polyphenols,” “vitagene,” “hormesis,” “oxidative stress,” “mitochondrial dysfunction,” and “Nrf2.” Both preclinical and clinical studies were considered.

Inclusion criteria were: (i) peer-reviewed original studies or systematic reviews/meta-analyses in English; (ii) human clinical trials, in vivo, or in vitro studies addressing nutritional or hormetic interventions relevant to ASD; and (iii) data on molecular mechanisms or clinical outcomes.

Exclusion criteria included: (i) studies without mechanistic or behavioral endpoints, (ii) case reports, or (iii) interventions unrelated to nutritional modulation.

Neuronutrition studies and mechanism of action in ASD

Recent studies have increasingly highlighted the role of targeted nutrients in improving behavioral, cognitive, and physiological outcomes in individuals with ASD [5]. Patients with ASD often exhibit antibodies against vitamin transporters at the blood-brain barrier, leading to cerebral vitamin deficiencies. Restrictive eating behaviors and long-term treatments, such as antiepileptic drugs for comorbid psychiatric conditions, further increase the risk of vitamin and nutrient deficiencies in children with ASD [6]. While pharmacological interventions like risperidone and aripiprazole can reduce irritability and aggression, they are often associated with side effects including changes in appetite, weight, and sleep patterns [7]. Specific metabolic phenotypes such as increased oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and reduced methylation capacity indicate heightened nutritional demand in ASD [8]. Table 1 summarizes the recent evidence-based data on nutrients studied in ASD.

Evidences-based data on nutrients in ASD treatment.

| Nutrient | Mechanism of action | Evidence (sample and duration) | Primary outcomes | Safety/adverse events | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | VDR-mediated immune, serotonergic, neuroprotective regulation. | Meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (n=870 children; 8–16 weeks) | Core ASD symptoms: no significant improvement; irritability modestly improved (−0.37) in baseline-deficient children; High heterogeneity. | Generally safe; no severe or serious adverse events reported; supplementation tolerable within studied dose ranges. | Li et al. [9] |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | Anti-inflammatory, supports neuronal membrane fluidity and neurotransmission. | Meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (n=416 children; 8–52 weeks). | Small, non-significant effects on overall ASD behaviors (−0.10), hyperactivity (−0.24), stereotyped behavior (−0.20), communication (−0.09), emotional difficulty (−0.15). Moderate heterogeneity. | Safe and well tolerated; no serious adverse events observed in pediatric ASD trials. | Jia et al. [10] |

| Cobalamin (B12) | Enhances methylation, redox metabolism; ↑GSH, cysteine, SAM; ↓GSSG, SAH | Meta-analysis of 17 studies (n=600; 4–24 weeks) | Improved methylation (SAM/SAH, homocysteine), redox biomarkers (GSH, GSSG), clinical symptoms (communication, daily living, social skills); moderate effect in responders (0.59). Moderate heterogeneity. | Mild, transient adverse events (hyperactivity, irritability, sleep disturbances) reported in a minority of participants; no serious adverse events. | Rossignol and Frye [11] |

| Folinic acid (B9) | Supports one-carbon metabolism, methylation, DNA/RNA synthesis | Meta-analysis of 2 RCTs (n=103; 8–16 weeks) | Reduced ASD symptoms (MD −0.66; 95 % CI −1.22, −0.10; p=0.02); small sample, needs larger trials. | Mild and transient adverse events; overall well tolerated in pediatric populations. | Soetedjo et al. 2025 [12] |

| L-Carnitine | Supports mitochondrial function, β-oxidation, and energy metabolism | Three randomized trials (Geier [13], Fahmy [14], Goin-Kochel [15]), sample 10–30 children, age 2.7–10 years; doses 50–200 mg/kg/day; duration 4 weeks–6 months. | Improvements in hyperactivity, social behavior, and core ASD symptoms measured by CARS, CGI, ATEC; dose-dependent efficacy; rapid improvement in children with metabolic deficiencies (TMLHE), small sample, needs larger trials. | Generally well tolerated; mild gastrointestinal symptoms or strong body odor at higher doses; no serious adverse events. | Malaguarnera and Cauli 2019 [16] |

| Sulforaphane | Activates Nrf2–ARE and vitagene/HSP pathways; modulates glutathione redox, mitochondrial efficiency, and inflammatory signaling. | Meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (n=250, 10–18 weeks) | Improved total symptoms (SMD −0.27), aberrant behavior (−0.43), hyperactivity (−0.58), social interaction (−0.43), social communication (−0.24), restricted/repetitive behavior (−0.16). No sig. effect on irritability, anxiety, sensory sensitivity, social motivation. Moderate heterogeneity. | Well tolerated; adverse events comparable to control | Wang et al. 2025 [17] |

Oxidative stress and impaired redox homeostasis are significant concerns in ASD patients. The activation of vitagenes and the subsequent cellular stress response can potentially ameliorate some pathophysiological processes associated with ASD. For instance, the neuroprotective roles of sulforaphane and hydroxytyrosol, compounds known to activate vitagenes, have been explored for their potential benefits in ASD by enhancing the heat shock response and improving mitochondrial function, thus mitigating oxidative damage and improving behavioral symptoms [18]. These findings underscore a growing interest in hormetic interventions, setting the stage for exploring polyphenols and other hormetic compounds as promising strategies to support cellular stress responses and neuroprotection, which will be discussed in the following sections.

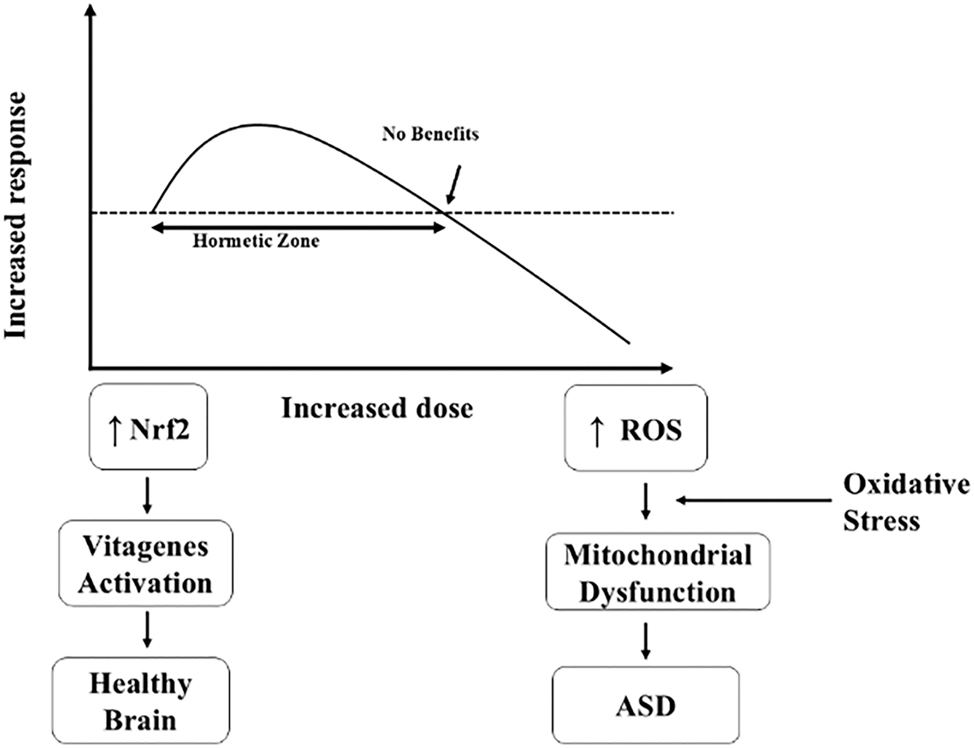

Hormesis and neuroprotective mechanisms

The neuronutrients that induce hormesis are those compounds that at low doses elicit a beneficial effect, whereas at higher doses, they are detrimental [19], 20]. Hormesis is a biological phenomenon characterized by a biphasic dose-response to an environmental agent or stressor [21]. In the context of cellular biology and health, hormesis involves the mild stress-induced stimulation of protective mechanisms, resulting in enhanced cellular resilience and function (Figure 1). Hormetic dose–response relationships are typically characterized by biphasic patterns, often represented as inverted U- or J-shaped curves. These phenomena have been consistently documented across a broad spectrum of biological systems, ranging from prokaryotes to humans, and involving diverse cell types. A distinctive feature of hormesis is the consistency of its quantitative parameters, which remain largely unaffected by variations in biological model, cell lineage, measured endpoint, triggering agent, or mechanistic pathway. The defining trait of the hormetic response is a relatively small but reproducible stimulatory effect, generally between 30% and 60 % above baseline levels. This effect spans numerous biological outcomes, including but not limited to cellular proliferation, organismal growth, reproductive capacity, cognitive performance, and longevity – underscoring its potential significance in health promotion, disease mitigation, and therapeutic applications, particularly in neuroprotection [22]. The concept of hormesis suggests that a certain degree of challenge or stress may be beneficial for health and longevity, in contrast to the notion that all stressors are inherently harmful [23].

The key stage of the hormetic response to cellular stress includes an initial adaptation and activation of defense mechanisms, a preconditioning response activated by mild stress exposure, the activation of vitagenes, and the incremental activation of mitochondria to produce more energy. Cells and organisms adapt to low stress levels by activating defense mechanisms and repair processes. Exposure to mild stress can help an organism to better withstand more severe stressors in the future. Hormetic stressors can activate vitagenes, which are genes involved in cellular stress response and protection. Mild mitochondrial stress can improve mitochondrial function and cellular energy production, while when stress becomes excessive or chronic induces pathophysiological conditions, such as in neuroinflammation and ultimately neurodegeneration. Hormetic stress often induces an increased production of endogenous antioxidants.

Hormetic responses can also result from overcompensation to disruption in homeostasis, enhancing antioxidant defenses, selective apoptosis, immunological responses, and intercellular communication [23]. The mechanisms of action of hormesis involve various cellular signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms. These typically include the activation of enzymes such as kinases and deacetylases, and transcription factors like Nrf-2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) and NF-κB, which lead to increased production of cytoprotective and restorative proteins [22]. Nrf2 is a member of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–like (NRF) transcription factor family, which consists of basic leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins structurally related to nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NFE2, also known as p45). These factors are defined by the presence of a conserved 43-amino acid Cap‘n’Collar (CNC) domain. Within this group, the vertebrate-specific NRF subfamily – which includes NRF1 (NFE2L1), NRF2 (NFE2L2), and NRF3 (NFE2L3) – is critically involved in regulating gene expression in response to oxidative and reductive stress conditions [24]. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1), which promotes its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Upon exposure to oxidative stress, Nrf2 is released from Keap1, translocates to the nucleus, and binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE) in the promoter regions of target genes. This binding induces the expression of a range of cytoprotective genes, including those encoding for heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferase (GSTs), and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [24]. Two recent studies have further explored a possible mechanism of neuroprotection via the activation of Nrf2: (i) mediated by pyridoxine, which induces glutathione synthesis via PKM2-mediated Nrf2 transactivation [25], and (ii) via a non-canonical activation of the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, which acts both in oxidative stress and in modulating autophagy [26]. The non-canonical activation of Nrf2 by p62 and PKM2-mediated activation by pyridoxine converge on the same outcome: the upregulation of antioxidant defenses, particularly GSH synthesis, to protect cells from oxidative damage and excessive autophagy. Recent evidence suggests that dysregulated autophagy contributes to neuroinflammatory mechanisms in autism spectrum disorder. Since USP18 facilitates the autophagic degradation of Gasdermin D to suppress pyroptosis, modulation of this pathway may represent a potential mechanism linking impaired cellular clearance with neuroimmune activation in ASD [27]. This understanding highlights the potential therapeutic significance of targeting the Nrf2 pathway to mitigate oxidative stress-related cellular damage (Figure 2).

Mechanisms of canonical and non-canonical Nrf2 activation the figure depicts the canonical and non-canonical pathways for the activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Under basal conditions (dark blue), Nrf2 resides in the cytoplasm, where it associates with Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), facilitating its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation via the proteasome. During oxidative stress (red), Nrf2 dissociates from KEAP1, translocates into the nucleus, and binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE) within the promoter regions of target genes. This interaction drives the expression of cytoprotective genes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase (γ-GCL). In the non-canonical activation pathway (yellow), polyphenol-induced inhibition of autophagy elevates the levels of p62, a protein that competes with KEAP1 for Nrf2 binding. This competitive interaction results in Nrf2 activation independent of KEAP1. Additionally, pyridoxine-mediated Nrf2 activation (light blue) constitutes another neuroprotective mechanism. Here, pyridoxine enhances glutathione synthesis by trans-activating Nrf2, a process reliant on the involvement of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2).

Several studies have demonstrated that nutrient-activating hormesis can bolster antioxidant defenses and attenuate neuroinflammation. For instance, a variety of phytochemicals, including stilbenoids, quinones, terpenoids, and carotenoids, have been shown to activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway through multiple distinct mechanisms. These include: (1) disruption of the Nrf2–Keap1 interaction, (2) covalent modification of critical cysteine residues on Keap1 via oxidation or alkylation, (3) modulation of upstream kinases such as GSK3β, p38 MAPK, ERK, AMPK, and PI3K/AKT, and (4) epigenetic regulation involving DNA methylation and histone modifications [28]. In addition, polyphenols exhibit a broad spectrum of bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-amyloidogenic, anti-α-synuclein, and antidepressant effects [28]. Sulforaphane, derived from cruciferous vegetables, activates the Nrf2 pathway, reduces oxidative stress, and improves behavioral outcomes in children with ASD [29]. Similarly, resveratrol and hydroxytyrosol exhibit neuroprotective effects by modulating oxidative stress pathways and enhancing mitochondrial function [30]. Notably, hydroxytyrosol, a compound derived from olive extract, markedly reduces amyloid-β aggregation and β-amyloid-induced paralysis – effects that are abolished when stress response genes such as skn-1/Nrf2 and hsp-16.2 are silenced [30]. Similarly, resveratrol confer protection against proteotoxic stress through pathways involving the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and proteasomal degradation, all reliant on skn-1/Nrf2 signaling [31]. It has been demonstrated that the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway is also modulated by Coriolus Versicolor and Hericium Erinaceus, two species of mushrooms that contain bioactive compounds that can enhance the body’s antioxidant defenses and provide neuroprotective effects. For example, the upregulation of Nrf2-regulated genes in these mushrooms has been linked to their ability to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby offering therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases [32]. In a recent Metanalysis by Yang J and colleagues, it has been underlined the beneficial roles of Nrf2 activators in improving autism-like behaviors by acting against inflammation, oxidant stress, and inflammation [33]. Further studies should investigate the mechanism of action by which nutrients, such as polyphenols and mushrooms, modulate the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway, and the correlation with ASD pathophysiology.

The concept of hormesis, in which low doses of a stressor stimulate protective responses, is closely related to the function of vitagenes. These vitagenes are involved in cellular mechanisms that adapt to mild stress, thereby improving cell survival and longevity by encoding proteins that protect against oxidative damage [3]. Thus, by modulating vitagenes, hormetic nutrition offers a promising approach for managing ASD by leveraging cellular stress responses and innate immune signaling. Incorporating specific hormetic nutrients into the diet can enhance cellular resilience, optimize mitochondrial function, and potentially ameliorate the neurological and behavioral symptoms associated with ASD.

Within the mitochondria, vitagenes play a significant role in regulating the cellular response to oxidative stress and maintaining mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are the major sources and targets of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are byproducts of cellular respiration. Through their encoded proteins, vitagenes help mitigate the damaging effects of ROS by enhancing antioxidant defenses and repairing damaged proteins and lipids. This protective mechanism is crucial for sustaining mitochondrial bioenergetics and preventing cellular damage, which can lead to various age-related diseases and neurodegenerative disorders [33]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are significant factors in ASD pathology. Numerous studies have demonstrated the co-occurrence of mitochondrial abnormalities and elevated oxidative stress markers in individuals with ASD [34]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD is characterized by deficiencies in electron transport chain (ETC) complexes, which impair cellular energy production and lead to increased ROS production. This imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses results in oxidative stress, which can cause extensive cellular damage and contribute to the neurodevelopmental deficits observed in ASD [35].

Role of polyphenolic compounds in autism spectrum disorders

Polyphenols, a type of secondary metabolite, have been identified in 8,000 plant species. Many of these polyphenols possess a bitter taste, while some have been found to have an astringent taste. The bitter taste receptors, such as taste receptor 2 (T2R) and transient receptor potential (TRP), are expressed in the digestive tract, including the oral cavity. The interaction between polyphenols and bitter taste receptors, and the subsequent transduction of these signals to the central nervous system, has been identified. The activation of T2R has been demonstrated to induce the secretion of gastrointestinal hormones, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), into the bloodstream, as well as the release of neurotransmitters into the vagus nerve. The latter is known to regulate appetite via the nucleus of the solitary tract, and so on [36]. Furthermore, the perception of astringency is recognized by TRP channels expressed on gastrointestinal sensory nerves and transmitted to the central nervous system, activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is a stress response, and enhancing sympathetic nerve activity. Within the HPA axis, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a stress hormone and neurotransmitter, is secreted, promoting the projection of noradrenaline from the locus coeruleus to the entire brain. Noradrenaline is known to enhance memory and learning. Consequently, the impact of polyphenols on brain function is significant [37], and it is anticipated that they will improve the symptoms of autism.

Resveratrol (RSV) is a polyphenolic compound present in grapes, peanuts, and red wine that has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects [38]. RSV has been observed to ameliorates brain edema, increases blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability, alters aquaporin profile, and augments GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression in rat models of autism induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid (VPA) [39]. An in vivo study showed that RSV (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) improved the symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in rats [40], reducing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress, making it a promising molecule against ASD [41]. Furthermore, oral administration of RSV ameliorated autistic behavior by reducing neuroinflammation in a propionic acid (PPA) model of autism [42]. It is noteworthy that the reduction in autistic traits was correlated with the possible alleviation of gastrointestinal (GI) alterations in animals, since PPA is a compound produced by intestinal bacteria [43]. Using a genetical animal model of ASD, it has been reported that intraperitoneal (i.p.) RSV improves social behavior, reduces the activation of Th cells, promotes T-regulatory cell function [44], and decreases the production of several pro-inflammatory mediators in the central nervous system (CNS) [45]. Sunand et al. found that a polyphenol–probiotic complex containing RSV, acetyl-l-carnitine, and curcumin reversed autistic traits and modulated biochemical levels of inteleukin-6 (IL-6), TNF-α, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), serotonin (5-HT), and acetylcholinesterase (AchE) in rats [46]. An open-label pilot trial studied the effect of 200 mg/d trans-resveratrol on five boys aged 10–13 years diagnosed with autism. RSV treatment significantly improved ASD symptoms and increased miR-195-5p, an important modulator of inflammatory and immunological pathways, suggesting the efficacy and safety of RSV in pediatric autistic subjects [47].

EGCG, the primary catechin in green tea, is also present in apples, peaches, kiwis, blackberries, pears, and nuts such as pistachios, hazelnuts, and walnuts [48]. In vitro, 3 μM EGCG restored dendritic and synaptic defects in neuronal models of CDKL5 deficiency disorder (CDD), a rare X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by seizures, motor impairments, and autistic-like features [49]. In Cdkl5-KO mice, low-dose EGCG (25 mg/kg daily, i.p., for 30 days) rescued glutamatergic synaptic contacts and spine morphology, whereas higher doses produced pro-apoptotic and hepatotoxic effects, consistent with the hormesis concept [49]. Similarly, in ASD rat models, EGCG at 2 mg/kg normalized key neurotransmitters and neurochemicals, including serotonin, glutamate, and nitrite [50].

EGCG rapidly crosses the blood–brain barrier and modulates intracellular Ca2+, ERK1/2, and NF-κB pathways, reducing IL-8 levels and supporting neuroprotection [51]. It also regulates gut microbiota–derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, which enhances mitochondrial function often impaired in ASD [52], 53]. Maternal butyrate supplementation in autistic mouse models has been shown to rescue social and repetitive behavioral deficits in offspring [54]. Beyond ASD, EGCG exhibits antioxidant properties and promotes neurogenesis and neuroplasticity in Down syndrome mouse models, indicating broader neuroprotective potential [55].

Although pediatric ASD trials are currently lacking, EGCG has been studied in children with Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome at 9 mg/kg/day (≈400–600 mg/day in adolescents) over several months, demonstrating good tolerability with hepatic monitoring [56].

Recent evidence has shown that other polyphenols that are structurally similar to EGCG, such as luteolin or quercetin, have achieved clinical benefits in the disease [57]. Luteolin exerts neuroprotective effects by reducing IL-6, TNF-α, nitrotyrosine, and NF-ĸB serum concentrations, improving neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, and inhibiting mast cell activation [58], 59]. In particular, Bertolino et al. investigated the effect of the association of ultramicronized fatty acid amide palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) with the polyphenol luteolin in VPA mice and the effect of PEA (700 mg) with luteolin (70 mg) in microgranules, twice a day, in a 10-year-old male child with ASD. The treatment ameliorated social and non-social behaviors in mice and improved patient clinical symptoms with a reduction in stereotypes [60]. These data suggest that ASD symptomatology may be improved by agents that control the activation of mast cells and microglia [60]. Similarly, luteolin and PEA reduced proinflammatory molecules, such as IL-1β, NF-κB, and TNF-α, influenced apoptosis markers in the hippocampus and cerebellum, and promoted enhanced neuroplasticity and neurogenesis in ASD animals [61]. Quercetin present in Chamomile sp., Sophora sp., and C. sinensis extracts promotes mitochondrial protection by increasing the scavenging antioxidant activity of ROS generated in the cell [62]. An open-label pilot study showed that children with ASD undergoing polyphenolic treatment based on an oral formulation consisting of luteolin (100 mg/capsule), quercetin (70 mg/capsule), and quercetin glycoside rutin (30 mg/capsule), at a dose of one capsule per 10 kg of weight per day for 26 weeks, showed significant improvement in several abilities, such as communication, concentration, and cooperation, with a parallel decrease in abnormal clinical traits [63] and a reduction in serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 [64].

Syringic acid (SA) is a polyphenolic compound with anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antioxidant, and neuromodulatory activities [65]. SA can prevent behavioral impairment, restore antioxidant enzyme and neurotransmitter levels, reduce neuroinflammation, improve neuronal integrity, and reduce p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) expression in a dose-dependent manner in VPA-treated rats [65].

Curcumin is a potential neuroprotector in psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders [66] that easily crosses the BBB, increasing the glutathione (GSH) concentration, reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, and improving ASD quality [67]. Treatment with curcumin orally administered for 4 weeks at different doses (50/100/200 mg/kg) has been shown to increase antioxidant defense, restore normal mitochondrial function, and ultimately improve behavioral defects in ASD rats [64], as well as abnormal body and brain weight values [68]. Furthermore, two studies were performed using the BTBRT+ltpr3tf/J (BTBRT) mouse model of ASD. The first, using 20 mg/kg of curcumin, reported enhanced neural stem cell proliferation and improved short-term memory and sociability [69]. The second study evaluated three different doses of curcumin (25/50/100 mg/kg), showing the restoration of several oxidative stress markers in the hippocampus and cerebellum, with a dose-dependent increase in sociability in curcumin-treated mice [70]. Taken together, these results suggest that this polyphenolic molecule could be effective in preventing autistic behavioral and biochemical traits. Autism is classified as a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). All PDDs have qualitative impairment in social relatedness and often interfere with symptoms, including irritability. Yokukansan (TJ-54), a traditional Japanese medicine that contains a mixture of dried herbs, 4 g of atractylodis lancease rhizome, 4 g of Poria, 3 g of Cnidii rhizoma, 3 g of Angelicae radix (Angelica acutiloba), 2 g of radix bupleuri, 1.5 g of radix glycyrrhizae, and 3 g of uncariae uncis cum ramulus [71], is widely prescribed for psychiatric disorders by acting mainly on the glutamatergic and serotonergic nervous systems. A 12 week prospective, open-label study of 20 children and adolescents diagnosed with PDDs showed that treatment with TJ-54 at dosages from 2.5 to 7.5 g/day resulted in significant amelioration of irritability, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech [72]. TJ-54 mechanism of action as a partial D2 agonist, 5-HT1A agonist, and 5-HT2A antagonist [73] may prove important for both its effectiveness and tolerability in PDDs.

Bacopa monnieri (BM) (Plantiginaceae), commonly called Brahmi, is a perennial herb found in northeast India. It is used in Indian traditional medicine; Ayurveda, as a memory booster, has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, analgesic, sedative, and antiepileptic properties [74]. In particular, several studies have shown that BM exerts a memory-enhancing effect as well as neuroprotection through the presence of bacoside A (Abhishek et al. [74]). BM at 80 mg/kg ameliorated social deficits, repetitive behavior, and cognitive and motor impairments in a VPA model of ASD [74]. Moreover, BM was found to have significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, ultimately improving the histopathological score and reducing the upregulated mRNA and protein expression of AMPA in both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [74]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that grape seed extract (GSE) alleviates oxidative damage [75] by modulating nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) activity, an essential transcription factor responsible for antioxidant defence and inflammatory cytokine expression [76]. Indeed, GSE exerts protective effects against these changes and ameliorates autism symptoms [77]. Interestingly, gallic acid, a major component of grape seeds, can facilitate a decrease in the number of cerebellar Purkinje and granular cells in autistic rats [78], making it a possible therapeutic agent for ASD.

Isothiocyanate sulforaphane (SF), present in high amounts in broccoli sprouts, has been reported to ameliorate autistic symptoms by increasing GSH production and reducing oxidative phosphorylation, lipid peroxidation, and neuroinflammation [79]. This double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial aimed to investigate the beneficial effects of risperidone and SF treatment in alleviating irritability in children with ASD. Compared with the placebo group, patients in the SF group showed greater improvements in irritability and hyperactivity symptoms [80]. The efficacy of SF was investigated in another randomized parallel double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial in children with ASD. SF treatment leads to improvements in sociability, communication, irritability, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech. Significant changes were also observed in the levels of biomarkers of glutathione redox status, mitochondrial respiration, inflammatory markers, and heat shock proteins [81].

Boswellia species gum resin contains many terpenes such as, mon, di, tri, tetra and pentacyclic triterpenes besides containing complex phenolic, flavonoids and other active compounds. The in vitro, in vivo and some clinical studies have shown that these bioactive substances exhibit extensive biological activities among those anti-inflammatory, protecting nervous system against many neurological disorders, antioxidants, free-radical scavenging, immunomodulating and other biological activities [82]. On the other hand, Boswellia sacra gum resin contains significant amounts of terpenes compared to many other Boswellia species. For instance, it contains large amounts of boswellic acids such as AKBA, alpha and beta boswellic acids [83]. There are accumulating evidences that these boswellic acids play a potential role as natural phytochemicals in reducing the pathogenic factors associated with various neurological disorders [84]. Furthermore, according to recently published literature, pentacyclic triterpenes play significant roles in many biological activities, such as inhibiting the release of some pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, and other cytokines mainly produced by blood monocytes, which are increased in nearly 100 % of autistic children beside enhancing the inflammatory cytokines IL-10 [85]. A recent study showed that autism may be accompanied by abnormalities in the inflammatory response system, specifically IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α in whole blood [86]. However, more clinical studies in humans are required at this stage to confirm the role of such bioactive substances, and their neuroprotective potential makes them a promising option for treating major neurological disorders, including autism, which is a complex neurological disorder of largely unknown cause.

Emerging in vitro and in vivo models to understand neuronutrition

Conventional pharmacological strategies have shown limited efficacy in treating neurodegenerative diseases, often due to restricted mechanisms of action and insufficient neuronal uptake [87]. As an alternative, neurohormesis has gained attention for its potential to activate adaptive, cytoprotective responses through mild metabolic stress. Within this framework, low-dose polyphenols have demonstrated neuroprotective and antioxidant effects by modulating key cellular pathways, notably the Nrf2 signaling cascade and vitagene network. Emerging in vitro and in vivo models are increasingly employed to investigate these mechanisms, offering valuable tools to elucidate the role of diet-derived compounds in promoting brain health and resilience through neuronutritional strategies [88].

The emergence of reprogramming technologies and the subsequent refinement of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)-based protocols for neuronal differentiation and 3D cerebral organoid generation has inaugurated a new paradigm in preclinical disease modeling with significant implications for drug discovery. By reprogramming adult cells into pluripotent stem cells, researchers can now readily generate a diverse range of neural cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, offering unprecedented opportunities to study human brain development and disease [89].

By recapitulating key developmental stages, these models allow for the study of factors and mechanisms that can perturb physiological function by interfering with these developmental processes. In the last decade, iPSC-derived brain models were successfully employed to model neurodevelopment and neurodevelopmental disorders [90], [91], [92], to study prenatal toxins exposure [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], and gene-environment interactions [98], 99].

iPSCs can also be used to derive three-dimensional (3D) cerebral organoids that better recapitulate the complex architecture and structural organization of the developing human brain [100]. Cerebral organoids have been effectively employed to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ASD [101], 102].

Regarding the testing of novel therapeutic molecules, the ability to generate patient-specific brain tissue provides a unique opportunity to directly test compounds on cells derived from the individual patient, thereby increasing the precision and relevance of drug discovery efforts. iPSCs-derived models can help stratify patients based on their molecular profiles, facilitating the identification of new therapeutic targets [103]. In particular, iPSC-derived patient-specific neural progenitor cells (NPCs) have been successfully employed for drug discovery in the context of neuropsychiatric disorders. Unlike immortalized cell lines conventionally used in drug discovery pipeline, NPCs rely on mitochondrial respiration and are sensitive to oxidative phosphorylation impairments, thus may represent a valuable model to carry out drug screenings for neurological disorders where mitochondrial function is impaired such as ASD [104], 105].

Other studies conducted in iPSCs-derived brain models have demonstrated the potential of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a drug in clinical trials for ASD, in correcting neuronal deficits in both idiopathic and syndromic forms of ASD [102], 106], 107]. Additionally, drugs like gentamycin and roscovitine have shown potential in addressing specific molecular defects underlying these disorders. These findings highlight the potential of iPSC-derived models to accelerate the development of targeted therapies for neurodevelopmental disorders [100].

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), with its conserved neural system and molecular pathways, has emerged as a valuable model for studying neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD. Several studies have demonstrated that low-dose treatments with polyphenolic compounds, such as hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein, enhance stress resistance and extend lifespan in C. elegans by activating the SKN-1/Nrf2 signaling pathway, which is crucial for oxidative stress defense and longevity regulation. Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated that extracts from olive leaves efficiently scavenged free radicals in vitro and significantly increased the expression of antioxidant enzymes extending lifespan and increased stress resistance in C. elegans [108]. Additionally, phenolic acid metabolites like protocatechuic, gallic, and vanillic acids have been shown to improve mitochondrial function, heat-stress resistance, and chemotaxis in C. elegans, indicating their potential as hormetic agents in neuroprotective strategies [109]. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of hormetic signaling and autophagic mechanisms in mediating the protective actions of dietary polyphenols against neurodegenerative pathologies in genetically amenable C. elegans models.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Nutritional interventions have shown promise in mitigating oxidative stress and improving mitochondrial function in ASD patients. Nutrients such as sulforaphane, hydroxytyrosol, omega-3 fatty acids, and acetyl-L-carnitine can activate vitagenes, upregulate antioxidant defenses, and enhance mitochondrial biogenesis [110]. Clinical studies have supported the efficacy of these nutritional interventions in improving the symptoms and metabolic profiles of children with ASD. For instance, supplementation with vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids has been associated with enhanced social skills and reduced hyperactivity [111], whereas acetyl-L-carnitine has been shown to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in ASD [112]. These findings highlight the potential of targeted nutritional strategies to support mitochondrial health and reduce oxidative stress, thereby contributing to the better management of ASD symptoms.

The advent of 3D cell models and iPSC-based techniques has transformed neuroscience by enabling the generation of diverse neural cell types and cerebral organoids, allowing researchers to model brain development, neurodevelopmental disorders, and drug discovery with unprecedented precision. These patient-specific models, which recapitulate human brain architecture and mitochondrial functions, have proven effective in identifying therapeutic targets and testing drugs for conditions such as ASD, highlighting their potential to accelerate targeted therapy development. Despite limitations in reproducibility, scalability, and translatability to human disease [113], organoid models offer a valuable platform for investigating neuroprotective mechanisms and screening novel therapeutic compounds for autism and other brain disorders. While their adoption for large-scale drug screening is currently hindered by these challenges, they have the potential to bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical research [114].

While in clinical research traditional approaches to managing ASD have primarily focused on behavioral interventions and pharmacological treatments, emerging research suggests that neuronutrition strategies, including targeted dietary interventions and supplementation, may offer promising alternatives for improving cognitive function, reducing oxidative stress, and alleviating ASD symptoms. The evidence presented underscores the potential of specific nutrients, such as sulforaphane, hydroxytyrosol, omega-3 fatty acids, and acetyl-L-carnitine, in mitigating oxidative stress and enhancing mitochondrial function in ASD patients. Clinical studies have demonstrated tangible improvements in ASD symptoms and metabolic profiles following nutritional intervention. As research in this area continues to evolve, it is becoming increasingly clear that a multidisciplinary approach incorporating neuronutrition, hormetic diet principles, and vitagen-targeted supplementation could play a crucial role in ameliorating ASD symptoms and significantly enhancing the quality of life of affected individuals.

Furthermore, research underscores the connection between atypical brain activation patterns and distinctive eye behaviors in individuals with ASD [115]. While direct evidence linking the eye as a model of the brain in autism research remains uncertain, studies have consistently identified unique gaze behaviors and eye movement patterns in individuals with ASD. These discoveries have spurred the development of diagnostic tools, such as the Gaze-Based Autism Classifier (GBAC), which leverages eye-tracking data and machine learning to enhance the precision of ASD detection [116]. Exploring the clinical impact of neuronutrition strategies in ophthalmology may pave the way for novel translational insights and therapeutic advancements. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that lipid imbalances may play a role in neuroinflammation and synaptic function, critical factors implicated in ASD pathophysiology [117]. Recent studies suggest a possible integration of lipidomics tear analysis and neuronutrition, presenting an intriguing avenue for advancing our understanding of ASD [118]. Tear lipidomics can provide a non-invasive biomarker source, capturing metabolic alterations and lipid profile changes associated with neurodevelopmental conditions like ASD. When combined with neuronutrition strategies, such as tailored dietary interventions rich in omega-3 fatty acids or other lipid-modulating nutrients, lipidomics analysis could offer valuable insights into individualized treatment approaches. Such strategies might not only improve systemic lipid profiles but also target neuroinflammatory pathways and mitochondrial dysfunctions commonly observed in ASD [119]. By leveraging the synergy between lipidomics and neuronutrition, researchers and clinicians could develop novel diagnostic tools and therapeutic approaches that address the underlying metabolic and neurological complexities of ASD.

Implementing neuronutrition strategies in the management of ASD requires a comprehensive and individualized approach. The foundation of this approach is engaging a registered dietitian or nutritionist with expertise in ASD to develop a tailored dietary plan. This professional should possess specific knowledge of the unique nutritional needs and challenges associated with ASD, including experience in creating meal plans that address common sensory sensitivities and food aversion. While research on its efficacy is mixed, some individuals with ASD have reported improvements in behavior, communication, and gastrointestinal symptoms following this diet. However, it is crucial to implement these dietary changes under professional supervision. Neuronutrition strategies should be integrated with existing behavioral and pharmacological treatments to provide a comprehensive approach to ASD management. Regular evaluation and modification of neuronutrition strategies in collaboration with healthcare professionals are essential for optimizing outcomes. Educating family members, caregivers, and school personnel about an individual’s neuronutrition plan ensures consistency across all environments. Providing clear guidelines, meal plans, and strategies for managing dietary needs in various settings is crucial for the success of the neuronutrition approach.

In conclusion, modifying dietary habits and supplementing with specific neuronutrients based on targeted neuronutritional goals represents a promising multidisciplinary strategy for promoting brain health and preventing and treating neurological disorders. Finally, exploring the use of functional foods and nutraceuticals may offer specific benefits for individuals with ASD. By adopting this comprehensive and individualized neuronutritional approach, it is possible to improve the management of ASD symptoms and enhance the overall quality of life of individuals with ASD. The study of neuronutrition, hormetic diet, and vitagen-targeted supplementation may ameliorate ASD symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We recognize helpful discussions and the help with the manuscript figure preparation with Beatrice Pranzo and Michela Perrone.

-

Funding information: This research has been conducted with funds from “PIACERI Ricerca di Ateneo 2024/2026, Linea Intervento 1” and from MIUR (PRIN 2022FWB4E).

-

Author contribution: Conceptualization: V. Calaberese, A. Danilov; literature review: G. Malaguarnera, S. Modafferi, A. Trapanotto, F. Fazzina; writing: A. Badaeva, U. Jacob, C. Girlando, D. Galimberti, C. Gagliano,T. Avitabile, F. Guadagni, L. Rashan; and editing and final approval: all authors.

-

Conflict of interest: Prof. Calabrese is Editor in Chief of Open Medicine Journal. This fact has not affected the peer review process. There is no other conflict of interest.

-

Data Availability Statement: Data supporting this study are available upon request.

References

1. Badaeva, AV, Danilov, AB, Clayton, P, Moskalev, AA, Karasev, AV, Tarasevich, AF, et al.. Perspectives on neuronutrition in prevention and treatment of neurological disorders. Nutrients 2023;15:2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112505.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Zamroziewicz, MK, Barbey, AK. Nutritional cognitive neuroscience: innovations for healthy brain aging. Front Neurosci 2016;10:240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00240.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Scuto, M, Trovato Salinaro, A, Caligiuri, I, Ontario, ML, Greco, V, Sciuto, N, et al.. Redox modulation of vitagenes via plant polyphenols and vitamin D: novel insights for chemoprevention and therapeutic interventions based on organoid technology. Mech Ageing Dev 2021;199:111551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2021.111551.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Hirota, T, King, BH. Autism spectrum disorder: a review. JAMA 2023;329:157–68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.23661.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Nogay, NH, Nahikian-Nelms, M. Effects of nutritional interventions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: an overview based on a literature review. Int J Dev Disabil 2022;69:811–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2036921.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Indika, NR, Frye, RE, Rossignol, DA, Owens, SC, Senarathne, UD, Grabrucker, AM, et al.. The rationale for vitamin, mineral, and cofactor treatment in the precision medical care of autism spectrum disorder. J Pers Med 2023;13:252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13020252.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Aishworiya, R, Valica, T, Hagerman, R, Restrepo, B. An update on psychopharmacological treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Neurotherapeutics 2022;19:248–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-022-01183-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Kuźniar-Pałka, A. The role of oxidative stress in autism spectrum disorder pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Biomedicines 2025;13:388. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13020388.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Li, B, Xu, Y, Zhang, X, Zhang, L, Wu, Y, Wang, X, et al.. The effect of vitamin D supplementation in treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Neurosci 2022;25:835–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2020.1815332.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Jia, S-J, Jing, J-Q, Yi, L-X, Yang, C-J. The effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Res Autism 2025;126:202642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reia.2025.202642.Search in Google Scholar

11. Rossignol, DA, Frye, RE. The effectiveness of cobalamin (B12) treatment for autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med 2021;11:784. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Soetedjo, FA, Kristijanto, JAF, Durry, FD. Folinic acid and autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of two double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials. AcTion: Aceh Nutr J 2025;10:194–203. https://doi.org/10.30867/action.v10i1.1743.Search in Google Scholar

13. Geier, DA, Kern, JK, Davis, G, King, PG, Adams, JB, Young, JL, et al.. A prospective double-blind, randomized clinical trial of levocarnitine to treat autism spectrum disorders. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:15–23. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.881792.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Fahmy, SF, El-Hamamsy, M, Zaki, O, Badary, OA. Effect of l-carnitine on behavioral disorder in autistic children. Value Health 2013;16:A15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.092.Search in Google Scholar

15. Goin-Kochel, RP, Scaglia, F, Schaaf, CP, Berry, LN, Dang, D, Nowel, KP, et al.. Side effects and behavioral outcomes following high-dose carnitine supplementation among young males with autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Glob Pediatr Health 2019;6:2333794X19830696. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X19830696.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Malaguarnera, M, Cauli, O. Effects of l-Carnitine in patients with autism spectrum disorders: review of clinical studies. Molecules 2019;24:4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24234262.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Wang, R, Ren, Z, Li, Y. The effect of sulforaphane on autism spectrum disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. EXCLI J 2025;24:542–57. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2025-8239.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Calabrese, V, Giordano, J, Ruggieri, M, Berritta, D, Trovato, A, Ontario, ML, et al.. Hormesis, cellular stress response, and redox homeostasis in autism spectrum disorders. J Neurosci Res 2016;94:1488–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23893.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Hayes, DP. Nutritional hormesis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;61:147–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602507.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Pande, S, Raisuddin, S. The underexplored dimensions of nutritional hormesis. Curr Nutr Rep 2022;11:386–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-022-00423-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Calabrese, V, Trovato, A, Scuto, M, Ontario, ML, Tomasello, M, Perrotta, R, et al.. Chapter 9 – resilience signaling and hormesis in brain health and disease. In: Human aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021:155–72 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-822569-1.00012-3Search in Google Scholar

22. Calabrese, EJ, Osakabe, N, Di Paola, R, Siracusa, R, Fusco, R, D’Amico, R, et al.. Hormesis defines the limits of lifespan. Ageing Res Rev 2023;91:102074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Mattson, MP. Hormesis defined. Ageing Res Rev 2007;7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Noruzi, M, Sharifzadeh, M, Abdollahi, M. Hormesis. In: Reference module in biomedical research. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2023:351–8 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-824315-2.00640-0Search in Google Scholar

25. Sandberg, M, Patil, J, D’Angelo, B, Weber, SG, Mallard, C. NRF2-regulation in brain health and disease: implication of cerebral inflammation. Neuropharmacology 2014;79:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.11.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Wei, Y, Lu, M, Mei, M, Wang, H, Han, Z, Chen, M, et al.. Pyridoxine induces glutathione synthesis via PKM2-mediated Nrf2 transactivation and confers neuroprotection. Nat Commun 2020;11:941. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14788-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Wang, L, Li, M, Lian, G, Yang, S, Wu, Y, Cui, J. USP18 antagonizes pyroptosis by facilitating selective autophagic degradation of gasdermin D. Research (Wash DC) 2024;7:0380. https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0380.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Thiruvengadam, M, Venkidasamy, B, Subramanian, U, Samynathan, R, Ali Shariati, M, Rebezov, M, et al.. Bioactive compounds in oxidative stress-mediated diseases: targeting the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway and epigenetic regulation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10121859.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Singh, K, Connors, SL, Macklin, EA, Smith, KD, Fahey, JW, Talalay, P, et al.. Sulforaphane treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:15550–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416940111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Terracina, S, Petrella, C, Francati, S, Lucarelli, M, Barbato, C, Minni, A, et al.. Antioxidant intervention to improve cognition in the aging brain: the example of hydroxytyrosol and resveratrol. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:15674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232415674.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Farkhondeh, T, Folgado, SL, Pourbagher-Shahri, AM, Ashrafizadeh, M, Samarghandian, S. The therapeutic effect of resveratrol: focusing on the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2020;127:110234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Trovato Salinaro, A, Pennisi, M, Di Paola, R, Scuto, M, Crupi, R, Cambria, MT, et al.. Neuroinflammation and neurohormesis in the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer-linked pathologies: modulation by nutritional mushrooms. Immun Ageing 2018;15:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-017-0108-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Yang, J, Fu, X, Liao, X, Li, Y. Nrf2 activators as dietary phytochemicals against oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:561998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Calabrese, V, Cornelius, C, Dinkova-Kostova, AT, Calabrese, EJ. Vitagenes, cellular stress response, and acetylcarnitine: relevance to hormesis. Biofactors 2009;35:146–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/biof.22.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Calabrese, V, Cornelius, C, Dinkova-Kostova, AT, Calabrese, EJ, Mattson, MP. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010;13:1763–811. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2009.3074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Osakabe, N, Ohmoto, M, Shimizu, T, Iida, N, Fushimi, T, Fujii, Y, et al.. Gastrointestinal hormone-mediated beneficial bioactivities of bitter polyphenols. Food Biosci 2024;61:104550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104550.Search in Google Scholar

37. Osakabe, N, Shimizu, T, Fujii, Y, Fushimi, T, Calabrese, V. Sensory nutrition and bitterness and astringency of polyphenols. Biomolecules 2024;14:234. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14020234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Malaguarnera, M, Khan, H, Cauli, O. Resveratrol in autism spectrum disorders: behavioral and molecular effects. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:188. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9030188.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Deckmann, I, Santos-Terra, J, Fontes-Dutra, M, Körbes-Rockenbach, M, Bauer-Negrini, G, Schwingel, GB, et al.. Resveratrol prevents brain edema, blood-brain barrier permeability, and altered aquaporin profile in autism animal model. Int J Dev Neurosci 2021;81:579–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdn.10137.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Carrasco-Pozo, C, Mizgier, M, Speisky, H, Gotteland, M. Differential protective effects of quercetin, resveratrol, rutin and epigallocatechin gallate against mitochondrial dysfunction induced by indomethacin in Caco-2 cells. Chem Biol Interact 2012;195:199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2011.12.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Bhandari, R, Kuhad, A. Resveratrol suppresses neuroinflammation in the experimental paradigm of autism spectrum disorders. Neurochem Int 2017;103:8–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Shultz, SR, MacFabe, DF. Propionic acid animal model of autism. In: Patel, V, Martin, C, editors. Comprehensive Guide to Autism. NY: Springer; 2014:1755–78 pp.10.1007/978-1-4614-4788-7_106Search in Google Scholar

43. Bin-Khattaf, RM, Al-Dbass, AM, Alonazi, M, Bhat, RS, Al-Daihan, S, El-Ansary, AK. In a rodent model of autism, probiotics decrease gut leakiness in relation to gene expression of GABA receptors: emphasize how crucial the gut-brain axis. Transl Neurosci 2024;15:20220354. https://doi.org/10.1515/tnsci-2022-0354.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Bakheet, SA, Alzahrani, MZ, Ansari, MA, Nadeem, A, Zoheir, KM, Attia, SM, et al.. Resveratrol ameliorates dysregulation of Th1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory cell-related transcription factor signaling in a BTBR T + tf/J mouse model of autism. Mol Neurobiol 2016;54:5201–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-0066-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Ahmad, SF, Ansari, MA, Nadeem, A, Bakheet, SA, Alzahrani, MZ, Alshammari, MA, et al.. Resveratrol attenuates pro-inflammatory cytokines and activation of JAK1-STAT3 in BTBR T(+) Itpr3(tf)/J autistic mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2018;829:70–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Sunand, K, Mohan, GK, Bakshi, V. Synergetic potential of combination probiotic complex with phytopharmaceuticals in valproic acid induced autism: prenatal model. Int J Appl Pharm Sci Res 2021;6:33–43. https://doi.org/10.21477/ijapsr.6.3.02.Search in Google Scholar

47. Marchezan, J, Deckmann, I, da Fonseca, GC, Margis, R, Riesgo, R, Gottfried, C. Resveratrol treatment of autism spectrum disorder – a pilot study. Clin Neuropharmacol 2022;45:122–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0000000000000516.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Nagle, DG, Ferreira, D, Zhou, YD. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): chemical and biomedical perspectives. Phytochemistry 2006;67:1849–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.06.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Trovò, L, Fuchs, C, De Rosa, R, Barbiero, I, Tramarin, M, Ciani, E, et al.. The green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) restores CDKL5-dependent synaptic defects in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis 2020;138:104791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Kumaravel, P, Melchias, G, Vasanth, N, Manivasagam, T. Dose-dependent amelioration of epigallocatechin-3-gallate against sodium valproate induced autistic rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2017;9:203–6. https://doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2017v9i4.17283.Search in Google Scholar

51. Pogačnik, L, Pirc, K, Palmela, I, Skrt, M, Kwang, KS, Brites, D, et al.. Potential for brain accessibility and analysis of stability of selected flavonoids in relation to neuroprotection in vitro. Brain Res 2016;1651:17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2016.09.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Serra, D, Almeida, LM, Dinis, TCP. Polyphenols as food bioactive compounds in the context of autism spectrum disorders: a critical mini-review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;102:290–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Rose, S, Bennuri, SC, Murray, KF, Buie, T, Winter, H, Frye, RE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the gastrointestinal mucosa of children with autism: a blinded case-control study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186377. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186377.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Cristiano, C, Hoxha, E, Lippiello, P, Balbo, I, Russo, R, Tempia, F, et al.. Maternal treatment with sodium butyrate reduces the development of autism-like traits in mice offspring. Biomed Pharmacother 2022;156:113870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113870.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Valenti, D, de Bari, L, de Rasmo, D, Signorile, A, Henrion-Caude, A, Contestabile, A, et al.. The polyphenols resveratrol and epigallocatechin-3-gallate restore the severe impairment of mitochondria in hippocampal progenitor cells from a Down syndrome mouse model. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1862:1093–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.03.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Scala, I, Valenti, D, Scotto D’Aniello, V, Marino, M, Riccio, MP, Bravaccio, C, et al.. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate plus omega-3 restores the mitochondrial complex I and F0F1-ATP synthase activities in PBMCs of young children with Down syndrome: a pilot study of safety and efficacy. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:469. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10030469.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Nasiry, D, Khalatbary, AR. Natural polyphenols for the management of autism spectrum disorder: a review of efficacy and molecular mechanisms. Nutr Neurosci 2023;2023:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2023.2180866.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Zuiki, M, Chiyonobu, T, Yoshida, M, Maeda, H, Yamashita, S, Kidowaki, S, et al.. Luteolin attenuates interleukin-6-mediated astrogliosis in human iPSC-derived neural aggregates: a candidate preventive substance for maternal immune activation-induced abnormalities. Neurosci Lett 2017;653:296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.06.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Asadi, S, Theoharides, TC. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and extracellular mitochondria augment IgE-stimulated human mast-cell vascular endothelial growth factor release, which is inhibited by luteolin. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-85.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Cristiano, C, Pirozzi, C, Coretti, L, Cavaliere, G, Lama, A, Russo, R, et al.. Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts autistic-like behaviours in BTBR T+tf/J mice: contribution of central and peripheral mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 2018;74:166–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Bertolino, B, Crupi, R, Impellizzeri, D, Bruschetta, G, Cordaro, M, Siracusa, R, et al.. Beneficial effects of co-ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide/luteolin in a mouse model of autism and in a case report of autism. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017;23:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12648.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Savino, R, Medoro, A, Ali, S, Scapagnini, G, Maes, M, Davinelli, S. The emerging role of flavonoids in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Med 2023;12:3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103520.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Chung, S, Yao, H, Caito, S, Hwang, JW, Arunachalam, G, Rahman, I. Regulation of SIRT1 in cellular functions: role of polyphenols. Arch Biochem Biophys 2010;501:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Taliou, A, Zintzaras, E, Lykouras, L, Francis, K. An open-label pilot study of a formulation containing the anti-inflammatory flavonoid luteolin and its effects on behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Ther 2013;35:592–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.04.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Tsilioni, I, Taliou, A, Francis, K, Theoharides, TC. Children with autism spectrum disorders, who improved with a luteolin-containing dietary formulation, show reduced serum levels of TNF and IL-6. Transl Psychiatry 2015;5:e647. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66. Calabrese, V, Cornelius, C, Mancuso, C, Barone, E, Calafato, S, Bates, T, et al.. Vitagenes, dietary antioxidants and neuroprotection in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:376–97. https://doi.org/10.2741/3250.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Blaylock, RL, Strunecka, A. Immune-glutamatergic dysfunction as a central mechanism of the autism spectrum disorders. Curr Med Chem 2009;16:157–70. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986709787002745.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Bhandari, R, Kuhad, A. Neuropsychopharmacotherapeutic efficacy of curcumin in experimental paradigm of autism spectrum disorders. Life Sci 2015;141:156–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2015.09.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

69. Al-Askar, M, Bhat, RS, Selim, M, Al-Ayadhi, L, El-Ansary, A. Postnatal treatment using curcumin supplements to amend the damage in VPA-induced rodent models of autism. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1763-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Zhong, H, Xiao, R, Ruan, R, Liu, H, Li, X, Cai, Y, et al.. Neonatal curcumin treatment restores hippocampal neurogenesis and improves autism-related behaviors in a mouse model of autism. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2020;237:3539–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05634-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Mizukami, K, Asada, T, Kinoshita, T, Tanaka, K, Sonohara, K, Nakai, R, et al.. A randomized cross-over study of a traditional Japanese medicine (kampo), Yokukansan, in the treatment of the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009;12:191–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S146114570800970X.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Wake, R, Miyaoka, T, Inagaki, T, Furuya, M, Ieda, M, Liaury, K, et al.. Yokukansan (TJ-54) for irritability associated with pervasive developmental disorder in children and adolescents: a 12-week prospective, open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2013;23:329–36. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2012.0108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Miyaoka, T, Furuya, M, Yasuda, H, Hayashida, M, Nishida, A, Insagaki, T, et al.. Yi-gan san as adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: an open-label study. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009;32:6–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e31817e08c3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Abhishek, M, Rubal, S, Rohit, K, Rupa, J, Phulen, S, Gurjeet, K, et al.. Neuroprotective effect of the standardised extract of Bacopa monnieri (BacoMind) in valproic acid model of autism spectrum disorder in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2022;293:115199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115199.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

75. Rajput, SA, Sun, L, Zhang, NY, Khalil, MM, Ling, Z, Chong, L, et al.. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract alleviates aflatoxin B1-induced immunotoxicity and oxidative stress via modulation of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways in broilers. Toxins (Basel) 2019;11:23. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11010023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76. Osakabe, N, Modafferi, S, Ontario, ML, Rampulla, F, Zimbone, V, Migliore, MR, et al.. Polyphenols in inner ear neurobiology, health and disease: from bench to clinics. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59112045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Arafat, EA, Shabaan, DA. The possible neuroprotective role of grape seed extract on the histopathological changes of the cerebellar cortex of rats prenatally exposed to valproic acid: animal model of autism. Acta Histochem 2019;121:841–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2019.08.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Samimi, P, Edalatmanesh, MA. The effect of gallic acid on histopathologic evaluation of cerebellum in valproic acid-induced autism animal models. Int J Med Res Health Sci 2016;5:164–71.Search in Google Scholar

79. Fahey, JW, Liu, H, Batt, H, Panjwani, AA, Tsuji, P. Sulforaphane and brain health: from pathways of action to effects on specific disorders. Nutrients 2025;17:1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081353.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80. Momtazmanesh, S, Amirimoghaddam-Yazdi, Z, Moghaddam, HS, Mohammadi, MR, Akhondzadeh, S. Sulforaphane as an adjunctive treatment for irritability in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Zimmerman, AW, Singh, K, Connors, SL, Liu, H, Panjwani, AA, Lee, LC, et al.. Randomized controlled trial of sulforaphane and metabolite discovery in children with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Autism 2021;12:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-021-00447-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82. Calabrese, V, Osakabe, N, Khan, F, Wenzel, U, Modafferi, S, Nicolosi, L, et al.. Frankincense: a neuronutrient to approach Parkinson’s disease treatment. Open Med (Wars) 2024;19:20240988. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2024-0988. Erratum in: Open Med (Wars). 2024 Dec 19;19(1):20242001. 10.1515/med-2024-2001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

83. Schmiech, M, Lang, SJ, Ulrich, J, Werner, K, Rashan, LJ, Syrovets, T, et al.. Comparative investigation of frankincense nutraceuticals: correlation of boswellic and lupeolic acid contents with cytokine release inhibition and toxicity against triple-negative breast cancer cells. Nutrients 2019;11:2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102341.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Ebrahimpour, S, Fazeli, M, Mehri, S, Taherianfard, M, Hosseinzadeh, H. Boswellic acid improves cognitive function in a rat model through its antioxidant activity: neuroprotective effect of boswellic acid. J Pharmacopunct 2017;20:10–17. https://doi.org/10.3831/KPI.2017.20.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85. Moudgil, KD, Venkatesha, SH. The anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of natural products to control autoimmune inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2022;24:95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010095.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

86. Alzghoul, L, Abdelhamid, SS, Yanis, AH, Qwaider, YZ, Aldahabi, M, Albdour, SA. The association between levels of inflammatory markers in autistic children compared to their unaffected siblings and unrelated healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci 2019;49:1047–53. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1812-167.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Palanisamy, CP, Pei, J, Alugoju, P, Anthikapalli, NVA, Jayaraman, S, Veeraraghavan, VP, et al.. New strategies of neurodegenerative disease treatment with extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Theranostics 2023;13:4138–65. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.83066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

88. Calabrese, V, Osakabe, N, Siracusa, R, Modafferi, S, Di Paola, R, Cuzzocrea, S, et al.. Transgenerational hormesis in healthy aging and antiaging medicine from bench to clinics: role of food components. Mech Ageing Dev 2024;220:111960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2024.11196.Search in Google Scholar

89. Costamagna, G, Comi, GP, Corti, S. Advancing drug discovery for neurological disorders using iPSC-derived neural organoids. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:2659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052659.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

90. Li, R, Sun, L, Fang, A, Li, P, Wu, Q, Wang, X. Recapitulating cortical development with organoid culture in vitro and modeling abnormal spindle-like (ASPM related primary) microcephaly disease. Protein Cell 2017;8:823–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-017-0479-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Lancaster, MA, Renner, M, Martin, CA, Wenzel, D, Bicknell, LS, Hurles, ME, et al.. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013;501:373–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12517.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

92. Paşca, AM, Park, JY, Shin, HW, Qi, Q, Revah, O, Krasnoff, R, et al.. Human 3D cellular model of hypoxic brain injury of prematurity. Nat Med 2019;25:784–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0436-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

93. Qiao, H, Zhang, YS, Chen, P. Commentary: human brain organoid-on-a-chip to model prenatal nicotine exposure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018;6:138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00138.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94. Dang, J, Tiwari, SK, Agrawal, K, Hui, H, Qin, Y, Rana, TM. Glial cell diversity and methamphetamine-induced neuroinflammation in human cerebral organoids. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:1194–207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0676-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

95. Ao, Z, Cai, H, Havert, DJ, Wu, Z, Gong, Z, Beggs, JM, et al.. One-stop microfluidic assembly of human brain organoids to model prenatal cannabis exposure. Anal Chem 2020;92:4630–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00205.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

96. Meng, Q, Zhang, W, Wang, X, Jiao, C, Xu, S, Liu, C, et al.. Human forebrain organoids reveal connections between valproic acid exposure and autism risk. Transl Psychiatry 2022;12:130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-01898-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

97. Zhong, X, Harris, G, Smirnova, L, Zufferey, V, Sá, RCDSE, Baldino, RF, et al.. Antidepressant paroxetine exerts developmental neurotoxicity in an iPSC-derived 3D human brain model. Front Cell Neurosci 2020;14:25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2020.00025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

98. Modafferi, S, Zhong, X, Kleensang, A, Murata, Y, Fagiani, F, Pamies, D, et al.. Gene–environment interactions in developmental neurotoxicity: a case study of synergy between chlorpyrifos and CHD8 knockout in human BrainSpheres. Environ Health Perspect 2021;129:77001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP8580.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

99. Umans, BD, Gilad, Y. Oxygen-induced stress reveals context-specific gene regulatory effects in human brain organoids. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2024. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.03.611030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

100. Wang, L, Owusu-Hammond, C, Sievert, D, Gleeson, JG. Stem cell-based organoid models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2023;93:622–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.01.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

101. Zink, A, Lisowski, P, Prigione, A. Generation of human iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) as drug discovery model for neurological and mitochondrial disorders. Bio Protoc 2021;11:e3939. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.3939.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

102. Marchetto, MC, Belinson, H, Tian, Y, Freitas, BC, Fu, C, Vadodaria, K, et al.. Altered proliferation and networks in neural cells derived from idiopathic autistic individuals. Mol Psychiatry 2017;22:820–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.95.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

103. Griesi-Oliveira, K, Acab, A, Gupta, AR, Sunaga, DY, Chailangkarn, T, Nicol, X, et al.. Modeling non-syndromic autism and the impact of TRPC6 disruption in human neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20:1350–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

104. Williams, EC, Zhong, X, Mohamed, A, Li, R, Liu, Y, Dong, Q, et al.. Mutant astrocytes differentiated from Rett syndrome patient-specific iPSCs have adverse effects on wild-type neurons. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:2968–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddu008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

105. Kleiman, RJ, Engle, SJ. Human inducible pluripotent stem cells: realization of initial promise in drug discovery. Cell Stem Cell 2021;28:1507–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2021.08.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

106. Griesi-Oliveira, K, Acab, A, Gupta, A, Sunaga, DY, Chailangkarn, T, Nicol, X, et al.. Modeling non-syndromic autism and the impact of TRPC6 disruption in human neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20:1350–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.141.Search in Google Scholar

107. Shen, J, Liu, L, Yang, Y, Zhou, M, Xu, S, Zhang, W, et al.. Insulin-like growth factor 1 has the potential to be used as a diagnostic tool and treatment target for autism spectrum disorders. Cureus 2024;16:e65393. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.65393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central