Abstract

Developing efficient and robust electrocatalysts is increasingly essential for water splitting, severely hindered by the sluggish four-electron transfer process of oxygen evolution reaction (OER). Amorphous/crystalline heterophase engineering has recently emerged as a promising electronic modulation approach for OER catalysts but suffers from poor conductivity of the amorphous structure. Here, we coupled the amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 induced by vanadium doping with NiP heterojunction, highlighting the synergistic effect in modulating the electronic structures and the complementary effect in promoting conductivity. As a superior electrocatalyst to commercial RuO2, the as-prepared NFO-V0.3-P showed a low overpotential of 277 mV at the current density of 20 mA cm−2, a Tafel slope of 45 mV dec−1, and long-term stability. The excellent OER catalytic activity is attributed to the synergistic effect at the heterophase interface with rich active sites, fine-tuning of electronic regulation, and enhanced conductivity.

1 Introduction

Electrolysis of water to produce hydrogen and oxygen is a promising approach to solving current energy crisis and environmental pollution problems [1,2,3]. The bottleneck of electrochemical water splitting is the slow oxygen evolution reaction (OER) on the anode [4], while the commonly used noble metal iridium (Ir)-based and ruthenium (Ru)-based catalysts are limited by their high cost and poor stability [5,6,7]. Therefore, the development of earth-abundant transition metals as high-performance OER electrocatalysts has attracted more and more researchers’ attention [8,9,10]. For example, spinel nickel ferrite NiFe2O4 has become a promising catalyst due to its advantages such as low cost, easy preparation, and easy structure control [11]. Researchers have prepared a series of NiFe2O4 catalysts with different structures and properties by hydrothermal method [12], solvothermal method [13], and sol–gel method [14]. However, pure NiFe2O4 is not suitable for OER due to the shortcomings of active sites and electronic structure and needs to be modified [15]. There are two main strategies to prepare transition metals into high-performance OER catalysts. The first is to adjust the morphology, geometry, and size of materials to increase the number of active centers [16,17,18]. The second is to improve the intrinsic activity of each active center by adjusting the crystal and electronic structures [19,20,21].

Doping can lead to heterophase, exhibiting optimized catalytic activity [22,23]. Recently, it has been reported that doping can induce the formation of amorphous/crystalline heterophase, resulting in abundant surface defects and coordinatively unsaturated sites, thereby increasing the exposure of active sites [24]. Han et al. fabricated F-doped Co2B with a high-density crystalline/amorphous interface that significantly enhances OER activity [25]. V is favored among all the dopants due to its low cost and robust existence in various valence states [26]. Li et al. reported that V promoted the transfer of electrons from Ni to VO x and reduced the adsorption energy; VO x also led to significant decay of the Ni lattice, resulting in amorphous/crystalline heterophase with increased electrochemically active surface area [27]. However, the low electrical conductivity of the amorphous structure severely limits the charge transfer during catalysis [28]. The built-in electric field at the heterojunction interface promotes charge transfer and redistribution, effectively regulating the electronic structure and enhancing conductivity [29]. Thus, heterojunction might be a remedy for the amorphous/crystalline structure. Furthermore, although spinel oxides have been intensively reported previously, the amorphous/crystalline heterophase spinel oxides coupled with phosphide heterojunction have not been reported yet. Therefore, it is desirable to construct such a hybrid interface and investigate the synergistic electronic regulation effect for boosting OER.

Based on the above challenges, we combined V-doping and phosphide heterojunction strategies to construct an amorphous/crystalline heterophase catalyst NFO-V0.3-P to synergistically optimize the electrical structure and conductivity for OER. The introduction of V weakened the crystallization ability of spinel NiFe2O4 and induced the formation of amorphous/crystalline heterophase with abundant oxygen vacancies and uncoordinated sites. Although V doping alone promoted the rearrangement of the electronic structure, the addition of NiP heterostructure improved the amorphous phase’s poor conductivity and further optimized the electronic structure by reducing the e g occupancy of Ni to be around 1.2. The as-prepared NFO-V0.3-P achieved a low overpotential of 277 mV at the current density of 20 mA cm−2, a Tafel slope of 45 mV dec−1, and long-term stability in alkaline media. This work provides an insightful coupling strategy for designing advanced OER electrocatalysts and performs a practical evaluation from the perspective of the e g occupancy in revealing its potential in synergistic electronic regulation.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, analytically pure), iron(iii) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, analytically pure), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, >98%), vanadium(iii) chloride (VCl3, >97%), ammonia (NH3·H2O, analytically pure), sodium hypophosphite (NaH2PO2, analytically pure), potassium hydroxide (KOH, analytically pure) were purchased from Kelong Chemical Agent. Ruthenium oxide (RuO2, 99.95%) was purchased from Alfa Aeser. Nafion solution (5%) was purchased from Dupont. All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

2.2 Synthesis of NFO electrocatalyst

First, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (1 mmol), Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (2 − x mmol), and CTAB (0.2 g) were dissolved in a mixed solution of 20 mL deionized water and 10 mL ethanol and stirred for 1 h to obtain a homogeneous solution. Then, NH3·H2O (3 mL) was added dropwise under vigorous stirring. Subsequently, the solution was transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 180°C for 12 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and water, and dried at 50°C overnight. Finally, the precursor was ground and calcined in a muffle furnace at 400°C for 4 h to obtain the NFO catalyst.

2.3 Synthesis of NFO-V x electrocatalysts

Except for the raw materials, the preparation method of NFO-V x (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5) catalysts is the same as that of NFO. First, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (1 mmol), Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (2 − x mmol), VCl3 (x mmol), and CTAB (0.2 g) were dissolved in a mixed solution of 20 mL deionized water and 10 mL ethanol and stirred for 1 h to obtain a homogeneous solution. The following preparation steps are exactly the same as that of NFO catalyst, and finally, the NFO-V x (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5) catalysts were obtained.

2.4 Synthesis of NFO-Vx-P electrocatalyst

The prepared NFO-V0.3 and NaH2PO2 were loaded in two porcelain boats with a mass ratio of 1:3 and were placed downstream and upstream of the tube furnace, respectively. The NFO-V0.3-P catalyst was prepared by heating to 300°C at a heating rate of 2°C min−1 under an Ar atmosphere for 2 h.

2.5 Material characterizations

The phase structure of the catalysts was determined using an X’pert Pro powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) from 20° to 80°. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and elemental mapping were obtained using a JEOL JSM-7800 F field-emission SEM. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were taken using a Tecnai G220 (S-TWIN, FEI). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was measured by Thermo ESCALAB 250XI. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were obtained using a Bruker EMX plus X-band EPR spectrometer.

2.6 Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed on Ivium Vertex. C electrochemical workstation in a three-electrode electrochemical cell. Pt sheet and Hg/HgO were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode. 1 M KOH solution was used as the electrolyte; 5 mg of catalyst was ultrasonically dispersed in a mixed solution of ethanol (900 μL) and Nafion (5 wt%, 100 μL) to obtain a homogeneous catalyst ink. Then, 100 µL of the as-prepared ink was drop cast onto nickel foam (1 cm × 1 cm) to prepare the working electrode with a catalyst loading of 0.5 mg cm−2.

The electrolyte was bubbled with O2 for 30 min before the OER measurements and maintained an O2-saturated electrolyte throughout the measurement. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) between 0 and 1 V vs Hg/HgO at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 was performed to activate the catalysts surface until a steady-state CV curve was established. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves were collected at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 and corrected by solution resistance (R s). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed at open circuit potential over the frequency range between 100 kHz and 0.1 Hz. By calibrating the reference electrode (Figure S1), all potential values were calibrated concerning the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) by E RHE = E Hg/HgO + 0.93 V. Overpotentials (η) was calculated based on the formula η = E RHE − 1.23 V. Electrochemical active surface areas (ECSA) were obtained by measuring electrochemical double-layer capacitance (C dl) of catalysts. Chronopotentiometry measurements evaluated stability at the current density of 20 and 100 mA cm−2.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization analysis of catalysts

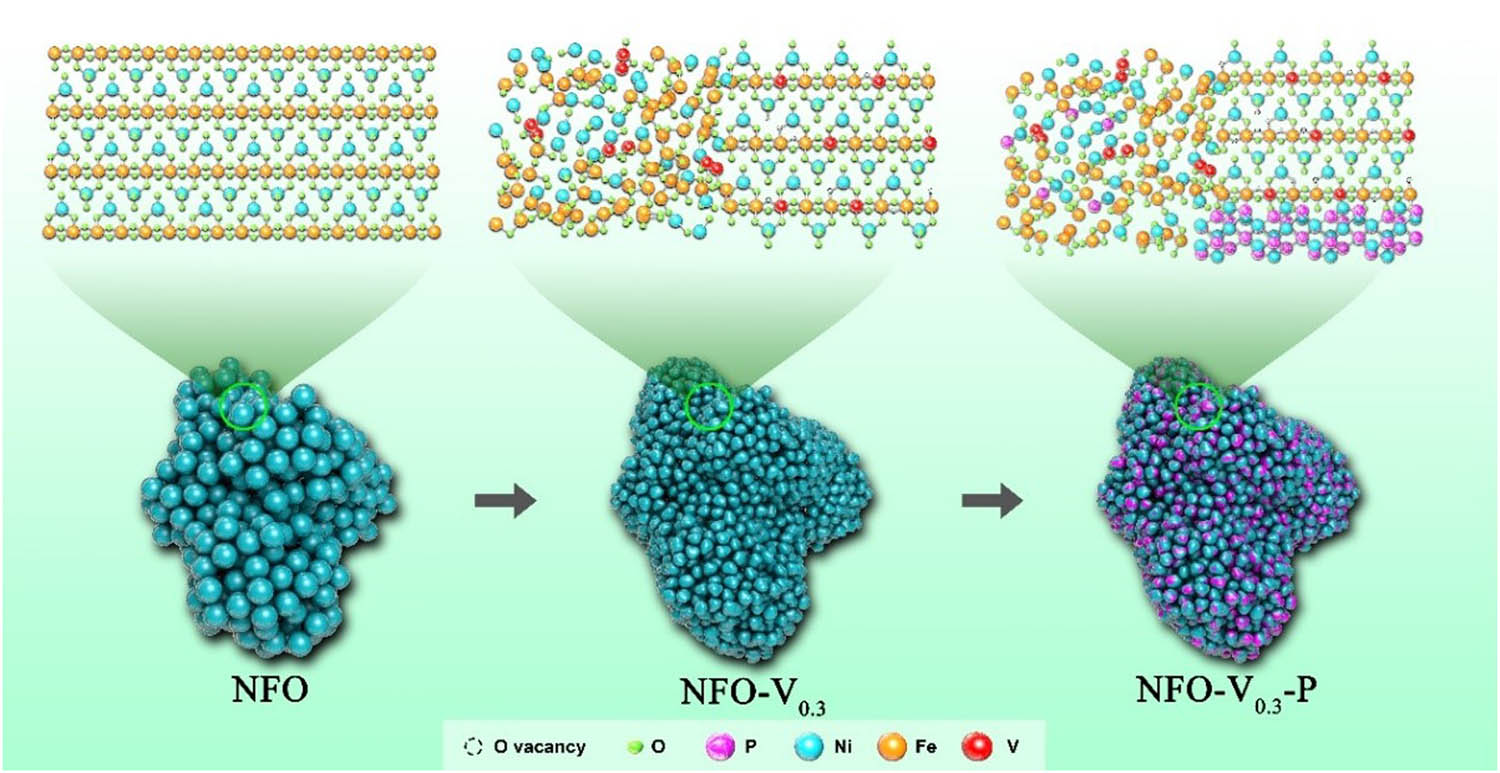

The synthesis of the NFO-V0.3-P catalyst involved two steps. As shown in Figure 1, the first step was to dope V into the catalyst by hydrothermal method. CTAB as a surfactant modulated the shape and size of nanoparticles and prevented excessive aggregation of nanoparticles. After the first heat treatment, transition metal oxide nanoparticles with the structural formula of NiV0.3Fe1.7O4 were prepared and denoted as NFO-V0.3. In the second step, a small amount of NaH2PO2 was pyrolyzed in a tube furnace to grow metal phosphide on the catalyst surface to obtain the final catalyst, which was named NFO-V0.3-P. V and P have been successfully introduced into the catalyst system in the corresponding steps, as shown in Figure 2(a) and Figures S2, S3. The distribution of each element in the catalyst is uniform.

Catalyst preparation process diagram.

(a) SEM image and the corresponding elemental mapping of NFO-V0.3-P. (b) XRD patterns of NFO, NFO-V0.3, NFO-V0.3-P. (c–e) TEM and (f–h) HRTEM image of NFO, NFO-V0.3, NFO-V0.3-P.

The catalysts’ morphology and crystal structure evolution after V introduction and surface partial phosphating were characterized using XRD and TEM. As shown in Figure 2(b) and Figure S4, the diffraction angles and diffraction intensity of the NFO catalyst are consistent with those of NiFe2O4 (PDF #10-0325), indicating the successful preparation of an inverse spinel transition metal oxide with the good crystal structure. The catalyst after V doping also shows a similar XRD pattern, but the diffraction intensity is reduced, indicating that the crystalline nature was affected due to the V doping. With the increase in V content, the diffraction intensity gradually decreases, indicating that the weakening of crystallinity is caused by V and is closely related to the content of V. The crystallinity of the catalysts is NFO (93.9%), NFO-V0.1 (91.6%), NFO-V0.3 (59.2%), and NFO-V0.5 (49.3%), respectively. The XRD pattern of NFO-V0.3-P shows that the partial phosphating of the surface does not significantly change the original crystal structure of the catalyst. The new diffraction peaks with low intensity at 35.15°, 39.15°, and 48.07° correspond to (112), (211), and (220) crystal planes of NiP, respectively, which indicate that NiP appeared after phosphating.

TEM and HRTEM images provide more details on the changes in the catalyst structure. Figure 2(c) shows the polycrystalline structure of NFO, consisting of irregular nanoparticles with a particle size of 10 nm. The lattice fringes corresponding to NiFe2O4 on the (220), (311), (440), and (400) planes are observed in Figure 2(f), which verifies the above-mentioned XRD characterization. As shown in the TEM image of NFO-V0.3 (Figure 2d), the polycrystalline structure still exists, but the nanoparticle size is significantly reduced. The corresponding HRTEM (Figure 2g) shows a sizeable blurred area without visible lattice fringes, recognized as the amorphous phase, which shows that the introduction of V in the catalyst weakens the crystallization ability of NFO-V0.3. The introduction of a small amount of V causes part of Fe to be replaced by V. Due to the differences in atomic radius and electronic structure of V and Fe, the presence of V in the crystal lattice hinders the crystallization process, thereby weakening the crystallization ability of the catalyst [24]. Thus, part of the crystalline phase is transformed into an amorphous phase. At the same time, the limited crystallization ability prevents the catalyst nanoparticles from growing large enough, resulting in the phenomenon of nanoparticle size reduction after V doping. With an appropriate amount of V doping, some regions in the catalyst are transformed into the amorphous phase, but the rest can still be crystallized normally. The amorphous/crystalline mixed heterophase is constructed by adjusting the amount of V doping. The amorphous/crystalline mixed heterophase structure in NFO-V0.3 provides many vacancies and interfacial defects, providing more reactive sites for catalytic reactions [30]. As shown in Figure 2(h), such an amorphous/crystalline heterophase structure is preserved after phosphating in NFO-V0.3-P. The lattice diffraction fringes correspond to the NiP (122) plane to support the XRD characterization.

XPS was used to further evaluate the surface chemical composition and valence state of the catalysts. As shown in Figure S6(a), the existence of the V 2p peak and P 2p peak can be observed in the XPS total spectra of the three catalysts, verifying the existence of V and P elements. On the high-resolution P 2p XPS spectrum of NFO-V0.3-P (Figure S6b), the doublet peak in the 127–131 eV region is ascribed to P-metal bonding [31]. The broad peak centered at 132.8 eV comes from the P–O bonding of phosphorus species exposed to air [32], which further proves the existence of metal phosphide on the catalyst surface.

For transition metal oxides, the e g occupancy of the transition metal ions at the active site is an essential descriptor of OER activity because the e g orbitals directly participate in σ bonding with surface oxygen [33]. A small e g occupancy will lead to strong oxygen binding force, and the intermediate cannot be effectively desorbed; a large e g occupancy will inhibit the activation of oxygen and weaken the binding force of the intermediate [34]. Previous studies have found that when the e g occupancy is around 1.2, an ideal balance will be reached, and the catalyst shows the optimal OER activity [35,36]. Since Ni2+ has a valence electron configuration of (t 2g6 e g2), it can be assumed that Ni2+ (e g = 2) is in a high-spin state and Ni3+ (e g = 1) is in a high-spin state. According to the ratio of Ni2+ and Ni3+, the e g occupy can be calculated [37]. As shown in Figure 3(a), with the introduction of V, a high oxidation state peak corresponding to Ni3+ appears at 856.28 eV, and the characteristic peak corresponding to Ni2+ is significantly reduced. According to the characteristic peak area Ni3+/Ni2+ = 1.23, the calculated e g occupancy is approximately 1.44. It is also observed in Figure 3(b) that the V 2p3/2 peak, which should be observed at 517.5 eV, appears at 517 eV. The lower valence is due to the acceptance of electrons from Ni. After growing the phosphide heterojunction, the corresponding binding energy of Ni 2p3/2 shifts positively from 855.08 to 855.38 eV, and the binding energy of the V 2p3/2 peak (Figure S3d) further decreases to 516.8 eV. The ratio of Ni3+/Ni2+ continues to increase, and the e g occupancy is calculated to be 1.26 by the ratio, which means the oxidation state of Ni is higher. The characteristic peak at 853.4 eV is attributed to Ni-P, which proves the existence of the NiP crystal phase on the catalyst surface [31].

XPS spectra of NFO, NFO-V0.3, NFO-V0.3-P in (a) Ni 2p, (b) Fe 2p, (c) O 1 s, and (d) V 2p region.

In the Fe 2p spectra shown in Figure 3(c), the signal mainly consists of two peaks near 712.7 and 724.3 eV, which belong to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2, respectively [38]. The Fe3+ content in high valence state increases after V doping and decreases after phosphating, which means that the overall oxidation state of Fe increases first and then decreases. The heterojunction changes the internal electronic structure of the catalyst, and more electrons are transferred around Fe3+ to ensure the high oxidation state and low e g occupancy of Ni in the catalytic active site. On the high-resolution O 1s XPS spectrum (Figure 3d), the peak at 529.7 eV is attributed to O-metal bonding, the peak at 532.6 eV is related to the hydroxyl species of surface adsorbed water molecules, while the peak at 531.2 eV is attributed to a large number of defect sites with low oxygen coordination, namely, oxygen vacancies [39]. It is clearly observed that the peak area at 531.2 eV increases with V doping and phosphide heterojunction. It indicates that amorphous/crystalline mixed heterophase and phosphide heterojunction bring more defects to the catalyst and are more favorable for OER activity [30]. EPR spectroscopy (Figure S7) also demonstrated changes in oxygen vacancies, and the enhanced EPR signal intensity at g = 2.003 is attributed to the significant increase in oxygen vacancies [40].

3.2 OER performance of catalysts

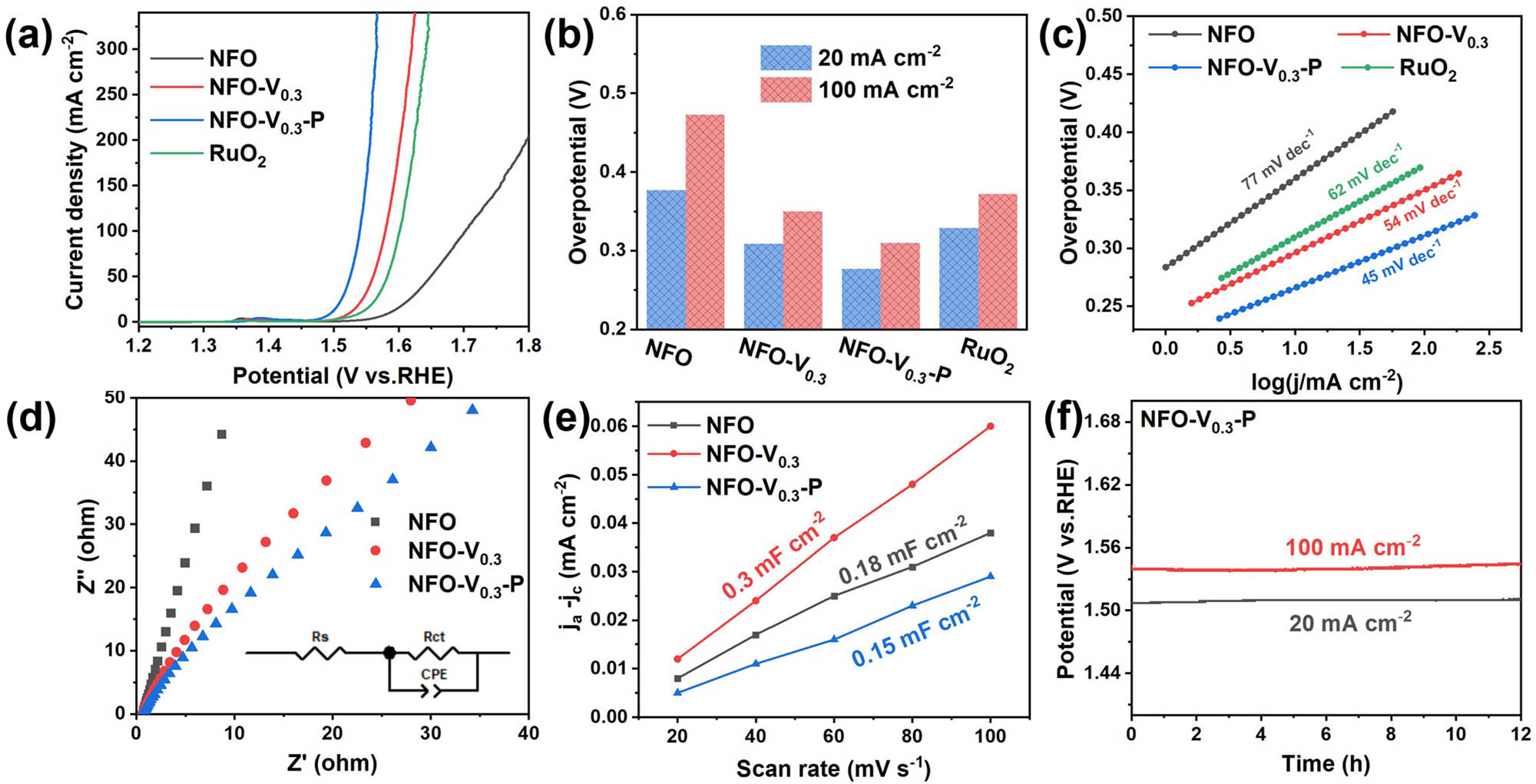

The OER activity of the catalysts was evaluated in 1 M KOH solution using a three-electrode cell, and commercial RuO2 was used for comparison. Clearly, catalysts with different V contents showed different degrees of OER activity improvement over NFO (Figure S8). NFO-V0.3 exhibits the lowest overpotentials of 309 and 350 mV at current densities of 20 and 100 mA cm−2. The enhanced OER activity is related to the formation of amorphous/crystalline heterophase and the regulation of electronic structure induced by V in the catalyst. After constructing the surface heterojunction, the OER activity of NFO-V0.3-P was further enhanced. As shown in Figure 4(a), NFO-V0.3-P exhibits low overpotentials of 277 mV and 310 mV at current densities of 20 and 100 mA cm−2, far superior to commercial RuO2. The Tafel plots (Figure 4c) converted from LSV curves can evaluate the reaction kinetics of the catalysts. NFO-V0.3-P shows the lowest Tafel slope of 45 mV dec−1 among all samples, outperforming NFO (77 mV dec−1), NFO-V0.3 (54 mV dec−1), and commercial RuO2 (62 mV dec−1). This indicates that the OER reaction kinetics of the catalyst are optimized by V doping and phosphide heterojunction.

(a) iR-corrected LSV curves of NFO, NFO-V0.3, NFO-V0.3-P, and RuO2. (b) A comparison of the overpotential values at the current densities of 20 and 100 mA cm−2. (c) Corresponding Tafel plots of the polarization curves in (a). (d) Nyquist plots of NFO, NFO-V0.3, NFO-V0.3-P. (e) The electrochemical C dl of NFO, NFO-V0.3, and NFO-V0.3-P. (f) OER chronopotentiometry measurement of NFO-V0.3-P catalyst at the current densities of 20 and 100 mA cm−2.

As shown in Figure S9, the intrinsic catalytic activity of the catalysts can be compared by measuring the C dl in the potential range from 0.83 to 1.03 V to estimate the ECSA. NFO-V0.3 possesses the highest C dl (0.3 mF cm−2), attributed to more defects in the amorphous/crystalline phases, exposing the most reactive sites. Although part of the active surface area of NFO-V0.3-P is covered by the phosphide heterojunction, the conductivity and more oxygen vacancy defects brought by phosphating significantly increase the OER activity. The charge transport properties of the catalysts can be further explored through the EIS tests. Figure 4(d) shows that NFO-V0.3-P has the lowest R ct, verifying the enhanced overall conductivity by phosphide heterojunction. Although the amorphous phase can provide many reactive sites, the electrical conductivity of both the spinel phase and the amorphous phase is relatively poor. Therefore, the phosphide heterojunction in NFO-V0.3-P sacrifices little reactive surface area to significantly improve the overall conductivity of the catalyst, which is helpful to further improve the electrocatalytic activity.

In our designed strategies, the enhanced OER activity of the catalyst is achieved by tuning the crystal structure and electronic structure. The amorphous phase induced by V doping in the crystal structure can provide more reactive sites, and its poor conductivity is improved by the phosphide heterojunction. The V and P heteroatoms introduced by the V-doping and NiP heterojunction strategies, respectively, jointly promote electronic rearrangement. The transfer of electrons from Ni to V or other atoms achieves a higher valence state of Ni and an e g occupancy closer to 1.2, as well as lower binding energy of the catalyst for oxygen intermediates. The optimization of the catalyst's electronic structure benefits from the synergistic regulation of the two designed strategies. Therefore, the OER activity of the catalyst is greatly enhanced after adjusting various factors such as active sites, conductivity, and e g occupancy. Finally, we evaluated the stability and durability of the synthesized catalysts in an alkaline electrolyte by measuring chronopotentiometry curves at 20 and 100 mA cm−2 in alkaline media, which is a critical factor for the large-scale application of catalysts in industrial applications. Chronopotentiometry curves of NFO-V0.3-P in 1 M KOH (Figure 4f) show that the overpotential increased by only 4 mV after continuous electrolysis for 12 h, indicating good stability at both low and high current densities.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we successfully constructed amorphous/crystalline heterophase coupled with phosphide heterojunction in NFO-V0.3-P by V doping and surface phosphating. The phosphide heterojunction improves the poor conductivity caused by the amorphous phase and achieves an e g occupancy of 1.26 for Ni. As a result, the catalyst exhibits a low overpotential of 277 mV at 20 mA cm−2, a Tafel slope of 45 mV dec−1, and long-term stability in alkaline electrolytes. The amorphous/crystalline heterophase and heterojunction provide more active sites and higher conductivity and promote the electronic regulation of active sites. This work provides an instructive strategy to construct amorphous/crystalline heterophase coupled with heterojunction for synergistically enhanced OER performance.

-

Funding information: The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52002338), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Sichuan Province (No. 2021ZYD0053), and Key R&D Program of Sichuan Province (2022YFSY0024).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Chen MP, Liu D, Zi BY, Chen YY, Liu D, Du XY, et al. Remarkable synergistic effect in cobalt-iron nitride/alloy nanosheets for robust electrochemical water splitting. J Energy Chem. 2022;65:405–14.10.1016/j.jechem.2021.05.051Search in Google Scholar

[2] Huang W, Peng C, Tang J, Diao FY, Yesibolati MN, Sun HY, et al. Electronic structure modulation with ultrafine Fe3O4 nanoparticles on 2D Ni-based metal–organic framework layers for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. J Energy Chem. 2022;65:78–88.10.1016/j.jechem.2021.05.030Search in Google Scholar

[3] Rahman ST, Rhee KY, Park SJ. Nanostructured multifunctional electrocatalysts for efficient energy conversion systems: Recent perspectives. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10:137–57.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0008Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang LH, Fan Q, Li K, Zhang S, Ma XB. First-row transition metal oxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts: Regulation strategies and mechanistic understandings. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2020;4:5417–32.10.1039/D0SE01087ASearch in Google Scholar

[5] Audichon T, Napporn TW, Canaff C, Morais C, Comminges C, Kokoh KB. IrO2 coated on RuO2 as efficient and stable electroactive nanocatalysts for electrochemical water splitting. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120:2562–73.10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b11868Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zagalskaya A, Alexandrov V. Mechanistic study of IrO2 dissolution during the electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. J Phys Chem Lett. 2020;11:2695–700.10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00335Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Audichon T, Mamaca N, Morais C, Servat K, Napporn TW, Mayousse E, et al. Synthesis of RuxIr1-xO2 anode electrocatalysts for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Electrocatal Appl Fuel Cell Electrol. 2013;45:47–58.10.1149/04521.0047ecstSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Tahir M, Pan L, Zhang RR, Wang YC, Shen GQ, Aslam I, et al. High-valence-state NiO/Co3O4 nanoparticles on nitrogen-doped carbon for oxygen evolution at low overpotential. Acs Energy Lett. 2017;2:2177–82.10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00691Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhou YN, Fan RY, Dou SY, Dong B, Ma Y, Yu WL, et al. Tailoring electron transfer with Ce integration in ultrathin Co(OH)2 nanosheets by fast microwave for oxygen evolution reaction. J Energy Chem. 2021;59:299–305.10.1016/j.jechem.2020.10.037Search in Google Scholar

[10] Liu Y, Ying YR, Fei LF, Liu Y, Hu QZ, Zhang GG, et al. Valence engineering via selective atomic substitution on tetrahedral sites in spinel oxide for highly enhanced oxygen evolution catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:8136–45.10.1021/jacs.8b13701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Singh NK, Singh RN. Electrocatalytic properties of spinel type NixFe3-xO4 synthesized at low temperature for oxygen evolution in KOH solutions. Indian J Chem Sect A Inorg Bio-Inorg Phys Theor Anal Chem. 1999;38:491–5.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Balasubramanian P, He SB, Jansirani A, Deng HH, Peng HP, Xia XH, et al. Engineering of oxygen vacancies regulated core-shell N-doped carbon@NiFe2O4 nanospheres: A superior bifunctional electrocatalyst for boosting the kinetics of oxygen and hydrogen evaluation reactions. Chem Eng J. 2021;405:126732.10.1016/j.cej.2020.126732Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yuan FF, Cheng XM, Wang MF, Ni YH. Controlled synthesis of tubular ferrite MFe2O4 (M = Fe, Co, Ni) microstructures with efficiently electrocatalytic activity for water splitting. Electrochim Acta. 2019;324:134883.10.1016/j.electacta.2019.134883Search in Google Scholar

[14] Maruthapandian V, Mathankumar M, Saraswathy V, Subramanian B, Muralidharan S. Study of the oxygen evolution reaction catalytic behavior of CoxNi1−xFe2O4 in alkaline medium. Acs Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:13132–41.10.1021/acsami.6b16685Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Chen Q, Wang R, Lu FQ, Kuang XJ, Tong YX, Lu XH. Boosting the oxygen evolution reaction activity of NiFe2O4 nanosheets by phosphate ion functionalization. Acs Omega. 2019;4:3493–9.10.1021/acsomega.8b03081Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Tian W, Li JY, Liu YF, Ali R, Guo Y, Deng LJ, et al. Atomic-scale layer-by-layer deposition of FeSiAl@ZnO@Al2O3 hybrid with threshold anti-corrosion and ultra-high microwave absorption properties in low-frequency bands. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021;13(1):161.10.1007/s40820-021-00678-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Liao CG, Yang BP, Zhang N, Liu M, Chen GX, Jiang XM, et al. Constructing conductive interfaces between nickel oxide nanocrystals and polymer carbon nitride for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1904020.10.1002/adfm.201904020Search in Google Scholar

[18] Huan TN, Rousse G, Zanna S, Lucas IT, Xu XZ, Menguy N, et al. A dendritic nanostructured copper oxide electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:4792–6.10.1002/anie.201700388Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Zhou Y, Zheng HY, Kravchenko II, Valentine J. Flat optics for image differentiation. Nat Photonics. 2020;14:316.10.1038/s41566-020-0591-3Search in Google Scholar

[20] Li X, Wang H, Cui ZM, Li YT, Xin S, Zhou JS, et al. Exceptional oxygen evolution reactivities on CaCoO3 and SrCoO3. Sci Adv. 2019;5(8):eaav6262.10.1126/sciadv.aav6262Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Wang HP, Wang J, Pi YC, Shao Q, Tan YM, Huang XQ. Double perovskite LaFexNi1-xO3 nanorods enable efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:2316–20.10.1002/ange.201812545Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kong QQ, Feng W, Zhang Q, Zhang P, Sun Y, Yin YC, et al. Hybrid amorphous/crystalline FeNi(Oxy) hydroxide nanosheets for enhanced oxygen evolution. Chemcatchem. 2019;11:3004–9.10.1002/cctc.201900718Search in Google Scholar

[23] Tuysuz H, Hwang YJ, Khan SB, Asiri AM, Yang PD. Mesoporous Co3O4 as an electrocatalyst for water oxidation. Nano Res. 2013;6:47–54.10.1007/s12274-012-0280-8Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kuang M, Zhang JM, Liu DB, Tan HT, Dinh KN, Yang L, et al. Amorphous/crystalline heterostructured cobalt-vanadium-iron (oxy)hydroxides for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Adv Energy Mater. 2020;10(43):2002215.10.1002/aenm.202002215Search in Google Scholar

[25] Han H, Choi H, Mhin S, Hong YR, Kim KM, Kwon J, et al. Advantageous crystalline-amorphous phase boundary for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. Energy Environ Sci. 2019;12:2443–54.10.1039/C9EE00950GSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Li PS, Duan XX, Kuang Y, Li YP, Zhang GX, Liu W, et al. Tuning electronic structure of NiFe layered double hydroxides with vanadium doping toward high efficient electrocatalytic water oxidation. Adv Energy Mater. 2018;8(15):1703341.10.1002/aenm.201703341Search in Google Scholar

[27] Li YB, Tan X, Hocking RK, Bo X, Ren HJ, Johannessen B, et al. Implanting Ni-O-VOx sites into Cu-doped Ni for low-overpotential alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2720.10.1038/s41467-020-16554-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Smith RDL, Prevot MS, Fagan RD, Zhang ZP, Sedach PA, Siu MKJ, et al. Photochemical route for accessing amorphous metal oxide materials for water oxidation catalysis. Science. 2013;340:60–3.10.1126/science.1233638Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Li SZ, Zang WJ, Liu XM, Pennycook SJ, Kou ZK, Yang CH, et al. Heterojunction engineering of MoSe2/MoS2 with electronic modulation towards synergetic hydrogen evolution reaction and supercapacitance performance. Chem Eng J. 2019;359:1419–26.10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.036Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zhang LJ, Jang H, Liu HH, Kim MG, Yang DJ, Liu SG, et al. Sodium-Decorated Amorphous/Crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: A robust pH-universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60:18821–9.10.1002/anie.202106631Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Li X, Huang WQ, Xia LX, Li YY, Zhang HW, Ma SF, et al. NiFe2O4/NiFeP heterostructure grown on nickel foam as an efficient electrocatalyst for water oxidation. Chemelectrochem. 2020;7:4047–54.10.1002/celc.202000958Search in Google Scholar

[32] Liu TT, Liu H, Wu XJ, Niu YL, Feng BM, Li W, et al. Molybdenum carbide/phosphide hybrid nanoparticles embedded P, N co-doped carbon nanofibers for highly efficient hydrogen production in acidic, alkaline solution and seawater. Electrochim Acta. 2018;281:710–6.10.1016/j.electacta.2018.06.018Search in Google Scholar

[33] Suntivich J, May KJ, Gasteiger HA, Goodenough JB, Shao-Horn Y. A perovskite oxide optimized for oxygen evolution catalysis from molecular orbital principles. Science. 2011;334:1383–5.10.1126/science.1212858Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Hardin WG, Mefford JT, Slanac DA, Patel BB, Wang XQ, Dai S, et al. Tuning the electrocatalytic activity of perovskites through active site variation and support interactions. Chem Mater. 2014;26:3368–76.10.1021/cm403785qSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Cai Z, Li LD, Zhang YW, Yang Z, Yang J, Guo YJ, et al. Amorphous nanocages of Cu-Ni-Fe hydr(oxy)oxide prepared by photocorrosion for highly efficient oxygen evolution. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:4189–94.10.1002/anie.201812601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Wei C, Feng ZX, Scherer GG, Barber J, Shao-Horn Y, Xu ZCJ. Cations in octahedral sites: A descriptor for oxygen electrocatalysis on transition-metal spinels. Adv Mater. 2017;29(23):1606800.10.1002/adma.201606800Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Da YM, Zeng LR, Wang CY, Gong CR, Cui L. A simple approach to tailor OER activity of SrxCo0.8Fe0.2O3 perovskite catalysts. Electrochim Acta. 2019;300:85–92.10.1016/j.electacta.2019.01.052Search in Google Scholar

[38] Fan K, Ji YF, Zou HY, Zhang JF, Zhu BC, Chen H, et al. Hollow iron-vanadium composite spheres: A highly efficient iron-based water oxidation electrocatalyst without the need for nickel or cobalt. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:3289–93.10.1002/anie.201611863Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Xue WJ, Cheng F, Li ML, Hu WJ, Wu CP, Wang B, et al. Surpassing electrocatalytic limit of earth-abundant Fe4+ embedded in N-doped graphene for (photo)electrocatalytic water oxidation. J Energy Chem. 2021;54:274–81.10.1016/j.jechem.2020.05.053Search in Google Scholar

[40] Zhang L, Lu CJ, Ye F, Wu ZY, Wang YA, Jiang L, et al. Vacancies boosting strategy enabling enhanced oxygen evolution activity in a library of novel amorphous selenite electrocatalysts. Appl Catal B. 2021;284:119758.10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119758Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption