Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

-

Maryamsadat Shahidi

and Davood Tofighi

Abstract

In the following research, we specifically assessed the feasibility of a novel AS-1411-chitosan (CS)-gold nanoparticle (AuNPs) delivery system to carry methotrexate (MTX) into the cancer cells. The designed system had a spherical shape with average size of 62 ± 2.4 nm, the zeta potential of −32.1 ± 1.4 mV, and released MTX in a controlled pH- and time-dependent manner. CS-AuNPs could successfully penetrate the breast cancer cells and release the therapeutic drug, and ultimately, be accumulated by the nucleolin-AS1411 targeting mechanism within the in vivo environment. The anticancer activity of MTX was attributed to the induction of mitochondria membrane potential loss and nuclear fragmentation, which leads to apoptotic death. Moreover, the cellular internalization confirmed the high potential in the elimination of cancer cells without notable cytotoxicity on non-target cells. Therefore, it was concluded that the AS1411-CS-AuNPs with considerable in vitro and in vivo results could be utilized as a favorable system for breast cancer treatment.

1 Introduction

The latest global cancer statistics elucidated that 2.3 million new cancer cases and 685,000 deaths occurred due to breast cancer in 2020 [1]. Over the past decades, different procedures have been licensed in the context of cancer therapy and led to a higher survival rate [2]. Among all commonly used procedures, chemotherapy still remained the mainstream strategy to treat an extended range of cancers in clinical practice; nonetheless, its efficiency is strictly reduced because of the systemic drug distribution and low therapeutic indices of chemotherapeutic drugs [3]. It seems, drug delivery nanosystems are promising for cancer therapy [4,5,6,7,8].

Methotrexate (MTX) is a folic acid antagonist approved for treating and managing rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, a recent investigation displayed the high capability of MTX as an agent to combat a variety of human cancer types like ovarian and breast cancers [9,10]. MTX can bind to folate receptors, impair DNA synthesis, and induce cell death in the rapid proliferation of breast cancer cells [11]. Despite the extensive clinical application of MTX, its efficacy is restricted due to the poor water solubility, short half-life, and severe toxic effects on healthy tissues [12].

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are a favorable nanomaterial in numerous medical applications, especially in controlled drug delivery and medical imaging, owing to their strong photostability, ease of synthesis, chemical stability, and low toxicity [13]. However, the full potential of these NPs is limited in living systems because of the direct interaction between the NPs and blood proteins, which affects the biological behavior and functionality of the NPs, resulting in inflammatory responses and insufficient delivery to target cells [14].

Chitosan (CS)-coated nanocarriers have a remarkable potential to be placed in biomedical applications [15,16,17]. CS is a natural polymer procured from chitin deacetylation, and its unique characteristics, such as non-toxicity, low immunogenicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, made it an attractive choice for delivery systems [18]. Additionally, it is documented that CS as a cationic polymer gives a positive charge to the surface of nanocarriers and enhances their affinity to contact negatively charged targets such as nucleic acids and cell membranes [19]. Site-specific drug delivery can be improved by decorating CS with specific ligands that couple to targets overexpressed on cancerous cells’ surfaces [20].

Aptamers are molecular recognition elements that include peptides and nucleic acids (RNA and ssDNA) that bind to a specific target molecule [21,22]. It is noteworthy that the AS1411, as one particular guanine-rich DNA aptamer, can attach to nucleolin as its target protein. Also, its expression on the surface of several cancer cells, like breast cancer, is highly observed but absent on normal cells [23].

In this research, we designed the AS1411-decorated CS-AuNPs complex not only to conquer the negative limitation of MTX but also to enhance the delivery mechanism by modifying the surface of AuNPs with biocompatible and biodegradable CS [24,25]. For this purpose, AuNPs are first conjugated by CS and then loaded with aptamer and MTX. To acquire the desired therapeutic consequence, the formulation containing MTX was optimized in particle size, zeta potential (ZP), and MTX loading. The resulted complex was examined in both in vitro and in vivo conditions to evaluate the delivery and impact of MTX on the proliferation of breast cancer. Moreover, to explore the specific effects of the complex on cancer cells, cultured Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were employed as the control group.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

For this experiment, trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), fetal bovine serum (FBS), DAPI (D8417), ethidium bromide, penicillin–streptomycin, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, Massachusetts, USA), 50–190 kDa CS (deacetylation degree = 85%), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), gold(iii) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and MTX (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) were acquired. The AS1411 aptamer with the sequence of 5′-GGTGGTGGTGGTTGTGGTGGTGGTGG-3′ was supplied from Yahooteb Novin Co.

2.2 Cell culture

The cell lines of MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 (as the target groups), and CHO (as the control group) were acquired from Tehran’s Pasteur Institute of Iran. All cell lines were individually cultured in 4.5 g/L glucose DMEM enriched by 1% antibiotic and 10% FBS, then incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 37°C and 5% CO2. Each cell line was checked daily under a microscope to observe confluency, and the culture mediums were renewed every 3 days.

2.3 Preparation of CS-AuNPs

In the beginning, the synthesis of AuNPs was performed according to Turkevich et al.’s previously described report. In brief, 20 mL of 1 mM HAuCl4·3H2O was added to a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask and boiled under vigorous stirring. Afterward, 2 mL of trisodium citrate solution (1%) and a reducing agent were quickly loaded into the boiling solution and continued stirring for 15 min. Next the heater was turned off, and the solution was stirred for an additional 15 min. At the end of the reaction, the color of the mixture turned from light yellow to deep red, representing the formation of AuNPs. Centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min was performed to discard the large particles. Ultimately, the obtained supernatant was dialyzed and freeze-dried, respectively.

In the next step, CS (20 mg) and acetic acid (1 mL, 1% v/v) solution were mixed and stirred for 24 h. Next 1,000 μL of AuNPs solution (pH 6.0) was added to 40 µL of the prepared CS solution under magnetic stirring for 2 h [26]. The resultant mixture was stored at 4°C for further studies.

In the final step, to synthesize Apt-CS-AuNPs conjugate, 1,000 μL of the CS-AuNPs solution and 10 μL of AS1411 (100 μM, activated with EDC/NHS) were mixed (pH 7.4) and kept for 1.5 h at room temperature. The obtained Apt-CS-AuNP was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 20 min to remove non-reactive AS1411. After centrifugation, the resulted Apt-CS-AuNP was dissolved in PBS and kept at −20°C.

Meanwhile, 8 mg EDC, 5 mg MTX, and 5 mg NHS were dispersed in 5 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) and kept in an incubator for 0.5 h at room temperature. To load MTX on the prepared Apt-CS-AuNPs, both suspensions were mixed and stirred for 48 h. The resulted MTX-Apt-CS-AuNP bioconjugate was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 0.5 h and lyophilized for 24 h. The presence of MTX in this bioconjugate was verified by using an ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy at 306 nm. The supernatant was collected for further indirect calculation of the drug-loading content. A dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Zetasizer analyzer (Nano-Z, Malvern, UK) was employed to assess the surface potential of the NPs at 25°C. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was performed to distinguish the functional groups of NPs using KBr pellets at 4 cm−1 resolution from 4,000 to 400 cm−1. The DLS measurements were conducted at pH 7.4 and 5.5 at room temperature [27]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT7700, Tokyo, Japan, Hitachi) was implemented to determine the average size of NPs. Also, the absorption of AS1411 molecules on the CS-AuNPs surface was evaluated by measuring the absorbance of AS1411-CS-AuNPs conjugate at 260 nm by a UV spectrophotometer (Cambridge, UK).

2.4 In vitro drug-release study

To evaluate the performance of the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex on the pH-dependent release of MTX, the complex was dispersed in 30 mL of PBS buffer at 5.5 and 7.4 pH in a dialysis bag (molecular cut-off, 2.0 kDa) under gentle stirring at 37°C. At certain time intervals (0–72 h), the release media (3 mL) was taken out and replaced with an equal volume of fresh buffer. The percentage of released MTX in certain time points was investigated by UV-vis absorbance at 306 nm. The cumulative release percentage of MTX was measured employing a standard curve.

2.5 In vitro stability of NPs

To monitor the in vitro stability of AuNPs and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS complex, the freeze-dried AuNPs and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS complex was re-suspended in PBS buffer (1:10 volume ratio). Then, the ZP and average size were measured regularly by DLS for 1 week.

2.6 Agarose gel electrophoresis

For evaluating AS1411 loading confirmation, the AS1411 molecules were mixed with the CS-AuNPs complex in a total volume of 10 µL in PBS or FBS at pH 7.5. The mobility of free AS1411 (positive control) and Apt-AuNPs-CS conjugate were evaluated by 2% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis containing ethidium bromide (1 h, 60 V).

2.7 AS1411 conjugation efficiency

To investigate the AS1411 conjugation efficiency, the AS1411 molecules were mixed with the CS-AuNPs complex and incubated for 24 h in the dialysis cassette. The unbounded AS1411 molecules were deleted from the AS1411-CS-AuNPs suspension using a dialysis cassette (3.5 kDa) during 48 h incubation. The AS1411-CS-AuNPs conjugate will be trapped in the cassette during the dialysis procedure, and the unconjugated AS1411 molecules will move from the cassette into the surrounding solution. The amount of unbounded AS1411 molecules was indirectly quantified by measuring its absorption at 260 nm and the AS1411 standard curve [28].

2.8 Cellular uptake using fluorescence microscopy

To explore the MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS complex’s cellular internalization, the target cells were cultured at 105 cells/well on confocal plates (35 mm) at 37°C for 0.5 days. The culture media was swapped with 2 mL of serum-free medium containing desired formulations and incubated for 4 h to investigate the uptake. Next the fluorescence images were obtained at the excitation of 559 nm and 400× magnification.

2.9 Cell toxicity assessment

The in vitro cytotoxicity of Apt-AuNPs-CS (without MTX), free MTX, MTX-AuNPs-CS (without Apt), and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS against all cell lines were measured at certain time points using an MTT cell viability kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, a density of 6 × 103 cells/well was planted in a 35 mm culture dish and incubated overnight. Cell in the logarithmic phase was utilized for treatment with concentrations of 0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, and 500 μg/mL of each drug formulation for 24 h. After incubation for 4 h, MTT (20 μL, 5 mg/mL in PBS) was transferred to each well. Ultimately, the formed crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 200 μL) and read by a microplate reader (BioTek, USA) at 570 nm.

2.10 Morphological modifications of cell nuclei

The target cells were cultured at 2 × 104 concentrations in a 35 mm culture plate and maintained overnight. The breast cancer cells were incubated with free MTX and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS at a 100 μg/mL concentration of each drug formulation at 37°C for 1 day. Then the morphological alterations of cell nuclei were distinguished by DAPI staining according to standard instruction.

2.11 Flow cytometry analysis

After the same culture density of target cells in the previous assessment, the cells received PBS (control), free MTX, and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS at 100 μg/mL of each drug formulation for 1 day. Afterward, the cells were harvested, cleaned in PBS, trypsinized, and centrifugated at 1,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellets were redispersed in 100 μL of binding buffer and exposed to propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate stains in a dark condition for 15 min. The flow cytometry was assessed using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

2.12 Cell cycle assay

First, target cells were exposed to 100 μg/mL PBS, free MTX, and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS for 1 day. Next the cells were harvested, rinsed in PBS, and fixed with cold ethanol (70%) overnight. To stain the cells with PI, they were subjected to RNase A (0.1 mg/mL) at 37°C for 30 min in a dark condition. Flow cytometry was employed to measure the percentage of the stained cells in different phases.

2.13 Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Based on the protocols given by the manufacturer, the target cells were cultured at 5 × 105 cells/well concentration, and 100 μg/mL of each drug formulation was included. After 1 day, 1 mL of culture medium containing JC-1 fluorescence dye (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was inserted and kept in an incubator for 20 min at 37°C. Ultimately, each dish was rinsed twice with ice-cold JC-1 dye and examined using flow cytometry to identify the MMP.

2.14 Generation of intracellular ROS assay

Herein 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was employed to stain and measure intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Therefore, the target cells were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well and maintained overnight to confluent. Next 100 μg/mL free drug and drug formulation were added to each cell line and kept for 1 day. Then, PBS containing 10 µM DCFH-DA was included in each sample and kept for 0.5 h at 37°C. Ultimately, a fluorescence microscope (400× magnification) was employed to capture images at 485 nm excitation and 520 nm emission.

2.15 Real-time PCR

After culturing cell lines overnight, they were treated with PBS, free MTX, and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS at 100 μg/mL of each drug formulation for 1 day. Next based on the instructions given by the manufacturer, the total RNA was extracted from the cell lines. Similarly, cDNA synthesis and SYBR® Premix Ex Taq TM II kits (TAKARA, Japan) were utilized to convert the RNA to cDNA and perform real-time PCR amplification. β-actin was considered a housekeeping gene (Table 1).

The specific primer sequences

| Genes | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) | 5′-ACAGAGGGCATGGAGAGAGA-3′ | 5′-CTGAGAGCAGGGATGTAGCC-3′ |

| B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) | 5′-CGGCTGAAGTCTCCATTAGC-3′ | 5′-CCAGGGAAGTTCTGGTGTGT-3′ |

| Caspase 3 | 5′-CTGTGTGCAGGCTTTTGTGT-3′ | 5′-CTCAATCACTGCTCGTGGAA-3′ |

| Caspase 9 | 5′-CGCCACTCTCTCATTCACAA-3′ | 5′-TCAAGGCAGCCTGTTCTTTT-3′ |

2.16 Western blotting

Like other assessments, after culturing and exposing the cell lines to each nanoformulation for 1 day, cells were gathered, and the total concentration of proteins was estimated by applying Bradford Assay. Next 50 μg protein samples were added, and to separate them, 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried to the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The samples were exposed to 5% bovine serum albumin to block and prepare the membranes for subjecting them to the primers (acquired from Cell Signaling Technology), including B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xl), Bax, Bcl-2, β-actin, cytochrome C (Cyt-C), caspase-3, and caspase-9, at 4°C overnight. At the end of the primary antibody incubation time, the membranes were subjected to the secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescence reagent and Image J software were employed to identify and visualize the protein bands. β-actin was considered as an internal control protein.

2.17 In vivo study

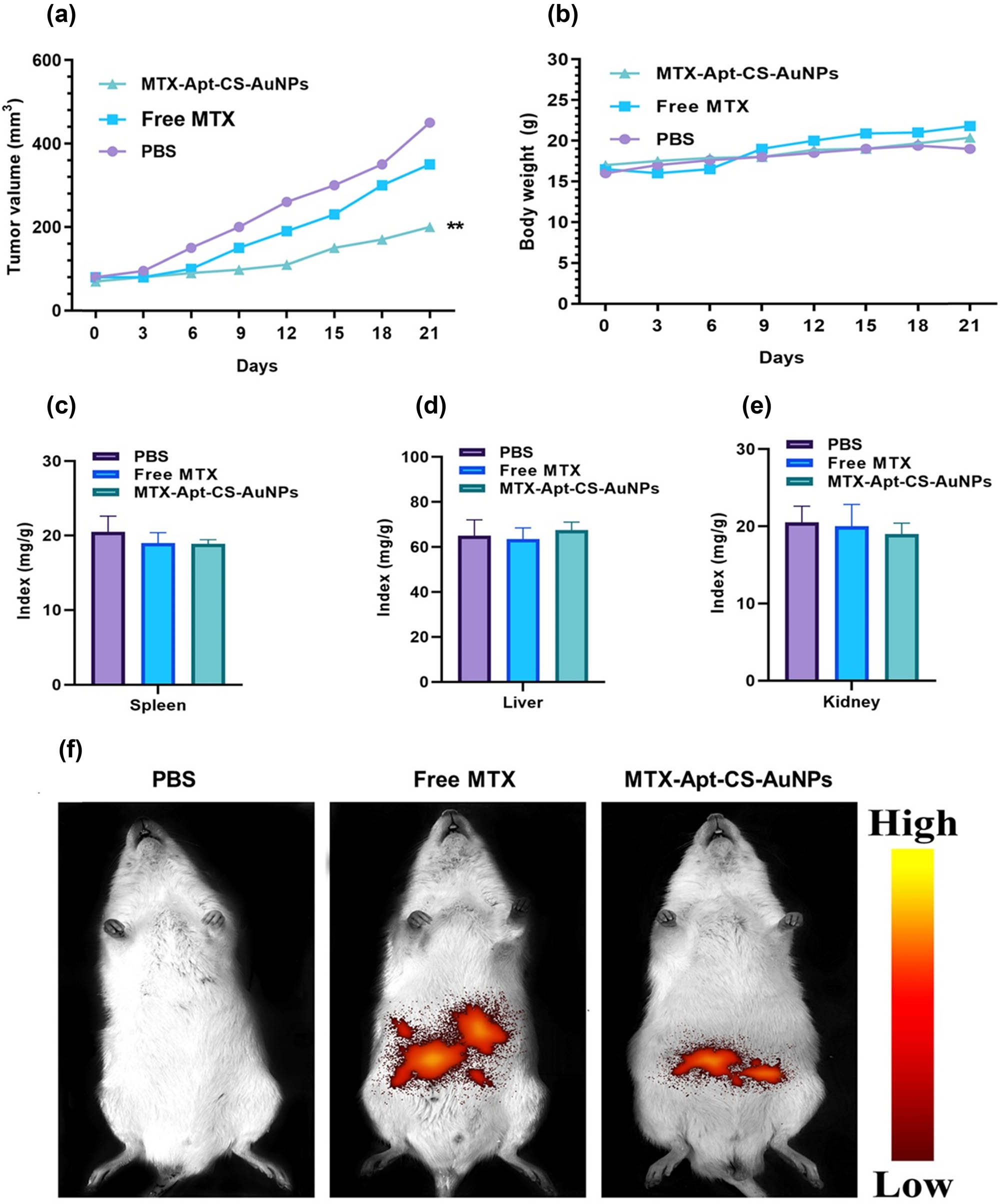

In this study, 15 4–5 weeks old BALB/c mice (16–20 g) were acquired from the Laboratory Animal Center of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (Yazd, Iran). All animal protocols were conducted under the university’s ethics. MDA-MB-231 cells at 4 × 105 concentration were subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of the mice. Once the tumor grew to about 30–40 mm3, they were categorized into 3 groups of 5. Next testing drugs, including MTX-Apts-CS-AuNPs complex, free MTX with 2.5 mg/kg MTX per mouse, and normal saline, were injected at the tail vein of each category. The tumor size ((length × width2)/2) and body weight were measured every 3 days for 21 days. The fluorescence imaging was conducted using an IVIS imaging system after 4 h of the last injection. All mice were sacrificed on day 21, and their liver, spleen, and kidney were removed and weighed. The organ indexes were calculated by the ratio of the organ weight to the body weight.

2.18 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were executed in the SPSS V.18.0 and GraphPad Prism V.8 software. The experimental variables were analyzed using appropriate tests, including one-way ANOVA. All data were stated as mean value ± standard deviation (SD). P-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of the synthesized MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex

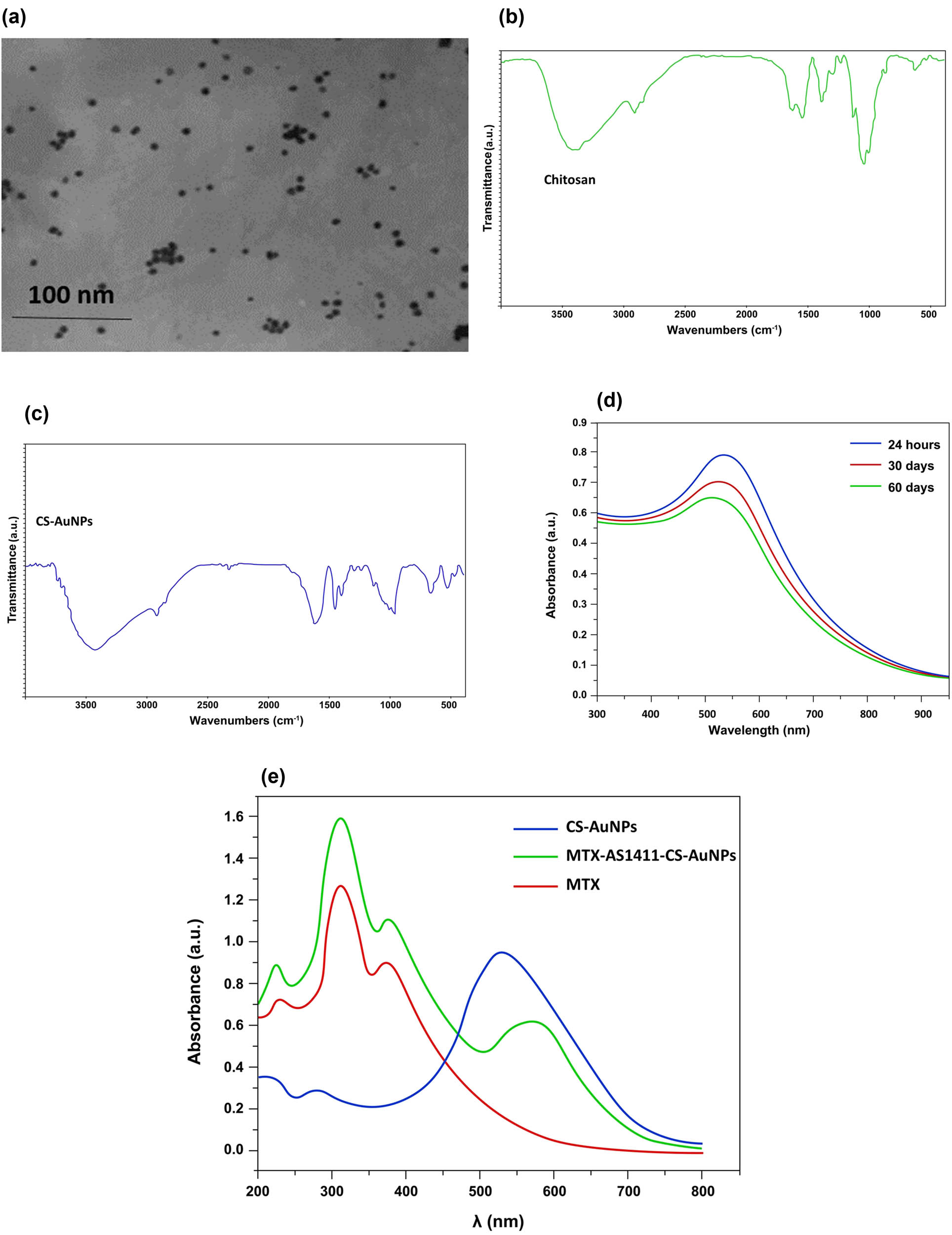

In various cancer treatment procedures, manifold documents have admitted the evolution of targeted drug delivery to successfully transfer chemo drugs to tumor sites and enhance their therapeutic efficiency on cancerous cells without significant drawbacks on non-cancerous cells [29]. Herein we mainly focused on designing a study to improve the therapeutic efficiency of MTX on breast cancer cells by the construction of the MTX-AS1411-AuNPs-CS complex. As a typical drug delivery vehicle, the size of NPs can enhance the solubility of hydrophobic drugs such as MTX and improve their therapeutic efficacy [30]. The MTX-loaded NPs below 200 nm can successfully circulate in blood vessels and then be preferentially taken up by tumor cells [31]. In the current work, the particle size and morphology of the synthesized CS-AuNPs complex were visualized using the TEM technique, and the images revealed a spherical shape with average sizes of 18.1 ± 1.5 nm (Figure 1a).

(a) TEM images of CS-AuNPs. (b) FTIR spectra of CS. (c) FTIR spectra of CS-AuNPs. (d) UV-visible absorption spectra of CS-AuNPs at different times. (e) UV-visible absorption spectra of in vitro MTX loading onto AS1411-CS-AuNPs.

Along with nanoparticle size, to characterize the possible changes in functional groups and absorption peaks on the surface of the AuNPs-CS conjugates, an FTIR spectrum was performed. In the FTIR spectra of CS, the functional broadband around 3,402 and 3,292 cm−1 was attributed to the N–H or O–H stretching vibrations. The peaks located at 2,856, 1,639, 1,559, 1,382, and 1,074 cm−1 were related to the C–H, C═O (amide I), N–H (amid II), C–H, and C–O groups, which were jointed to glucosamine and acetylglucosamine groups of CS (Figure 1b). The characteristic features of the CS spectrum observed in the current study were similar to some prior reports [32]. In the FTIR spectrum of CS-AuNPs, almost identical peaks as that of pure CS were observed, suggesting the presence of CS over AuNPs. The important difference observed in the FTIR of CS-AuNP and pure CS was the shift of a band observed at 1,559 cm−1 in the CS spectrum to 1,464 cm−1 in the CS-AuNP spectrum, which exhibited the attachment of AuNPs to CS through affinity interaction with amino groups, thus reducing the vibration intensity of N–H bond (Figure 1c). Contrary to our expectations, there was no change in the broadband centered around 3,400 cm−1. However, this band’s transmittance intensity was diminished compared to the intensity band observed in the FTIR record of CS. The formation of the CS-AuNPs complex could be suggested from the results recorded from FTIR and other experiments. The formation and stability of CS-AuNPs were also checked using UV spectrometer analysis. The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band was observed approximately at 530 nm and displayed a stable condition after two months (Figure 1d). These properties almost agree with the prior reports [33].

ZP is another essential parameter that predicts both nanosuspension’s surface charge and physical stability. The results exhibited that after adding CS to AuNPs, the ZP shifted from −21.6 ± 7.3 to +17.8 ± 4.6 mV due to the presence of the amino groups of CS coating on the AuNPs surface. On the contrary, after loading aptamer, the ZP shifted to −28.6 ± 4.9 mV due to the negatively charged AS1411 on the outer surface of CS-AuNPs, verifying the synthesis of AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex (Table 2). The successful AS1411 absorption was proved by the agarose gel electrophoresis and measuring the absorbance at 260 nm and changes in CS-AuNPs surface charge (Table 2). As shown in Figure S1a, after adding the AS1411 aptamer to the CS-AuNPs complex, its related band did not appear on the agarose gel compared to the bright band of free aptamer, suggesting the successful conjugation of AS1411 and CS-AuNPs complex. On the other hand, the UV absorption spectra of the conjugated AS1411-CS-AuNPs exhibited an absorbance peak at 260 nm, which could suggest successful aptamer attachment on the surface of CS-AuNPs (Figure S1b). Moreover, AS1411 loading efficiency was >85%, confirming AS1411 conjugation to the surface of CS-AuNPs.

The average size and ZP of AuNPs, CS-AuNPs, AS1411-CS-AuNPs, and MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs

| Samples | Average size (nm) | ZP (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| AuNP | 18.1 ± 1.5 | −21.6 ± 7.3 |

| CS-AuNP | 29 ± 4.2 | +17.8 ± 4.6 |

| AS1411-CS-AuNPs | 38.9 ± 1.8 | −28.6 ± 4.9 |

| MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs | 62 ± 2.4 | −32.1 ± 1.4 |

Presented data are provided as mean value ± SD (n = 5).

We also demonstrated the release of AS1411 from CS-AuNPs in a 10% FBS-containing medium (pH 7.5). Agarose gel electrophoresis illustrated that the AS1411 was slightly released from the nano-vehicle and was detectable after 48 h. These results suggested the protection of AS1411 by the CS-AuNPs at pH 7.4 in FBS solution (Figure S1c).

The stability of NPs in pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 was also determined using DLS analysis. In Figure S2a and S2b, both AuNPs and MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs were found to have good stability with minimal size changes at pH 7.4 during 7 days. DLS analysis also revealed that AuNPs and MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs (pH 7.4) had a constant surface charge for 7 days (Figure S3a and b). Due to the polycation property of CS, its structure was altered at different pHs. In lower pH solutions, CS molecules become more protonated and extended, and this causes higher hydrodynamic volume NPs [34]. However, the average size of MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs became abnormal after 24 h in the pH 5.5 buffer, suggesting the collapses in NPs (Figure S2c).

Moreover, the efficiency of MTX loading into Apt-CS-AuNPs conjugates was determined by UV-visible spectroscopy. As presented in Figure 1e, 2 particular absorption bands around 310 and 380 nm corresponded to the absorption of MTX bands, implying that MTX was successfully incorporated into CS-AuNPs. In addition, CS-AuNPs presented a peak around 530 nm, corresponding to the SRP band of spherical AuNPs (Figure 1e). However, the absorbance of MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNP is higher than AuNPs-CS, and the SPR peak shifted to a longer wavelength (580 nm). As the particle diameter increases, the plasmon absorption band shifts toward a longer wavelength (red-shifting) [35].

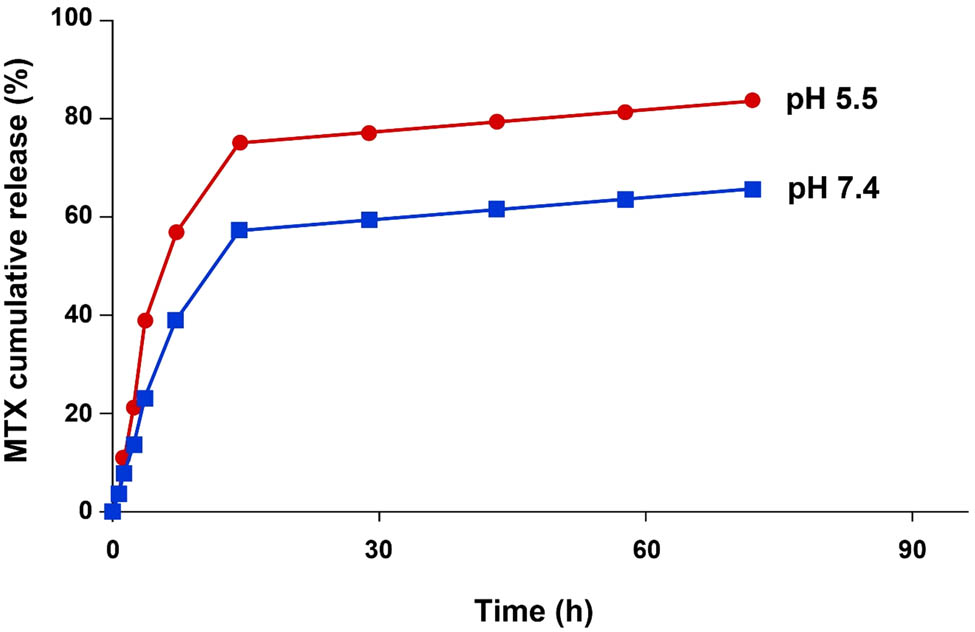

3.2 In vitro release behaviors of MTX from the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex

Drug release from NPs at physiological pH plays an important role in forming toxic effects on healthy cells. The slower release of MTX from the vehicle at pH 7.4 was predictable because of the low hydrolysis of amide bonds, which can greatly reduce the systemic toxic effects. Similarly, Luo et al. investigated the PEGylated-CS NPs and concluded that the MTX release had a higher pace in acidic pH than physiologic pH, which was similar to our results [36]. The release of MTX from the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs as a drug carrier system was determined at different pHs and times, and the results are shown in Figure 2. To mimic the human healthy and unhealthy physiological environments, the release of MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 was investigated at pH 7.4 and 5.5, respectively. As expected, a higher release rate, 74%, at pH 5.5 (the lysosome pH) than pH 7.4 (the physiological pH) was obtained after 72 h of treatment. Therefore, it was concluded that the release of MTX in acidic pH is highly dependent on the –NH2 groups of CS, which could be selectively protonated in the low pH of the tumor environment. After penetration into the cells, as the lysosomal compartments have an acidic pH (around 4.5–5.5), it was assumed that MTX was released from the MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411, then entered into the cytosol. Moreover, lysosomal organelles contain various hydrolytic enzymes that can break down the internalized AuNPs-CS-AS1411 conjugate [37].

The MTX release profile from the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs conjugate at pH 5.5 (top line) and pH 7.4 (bottom line).

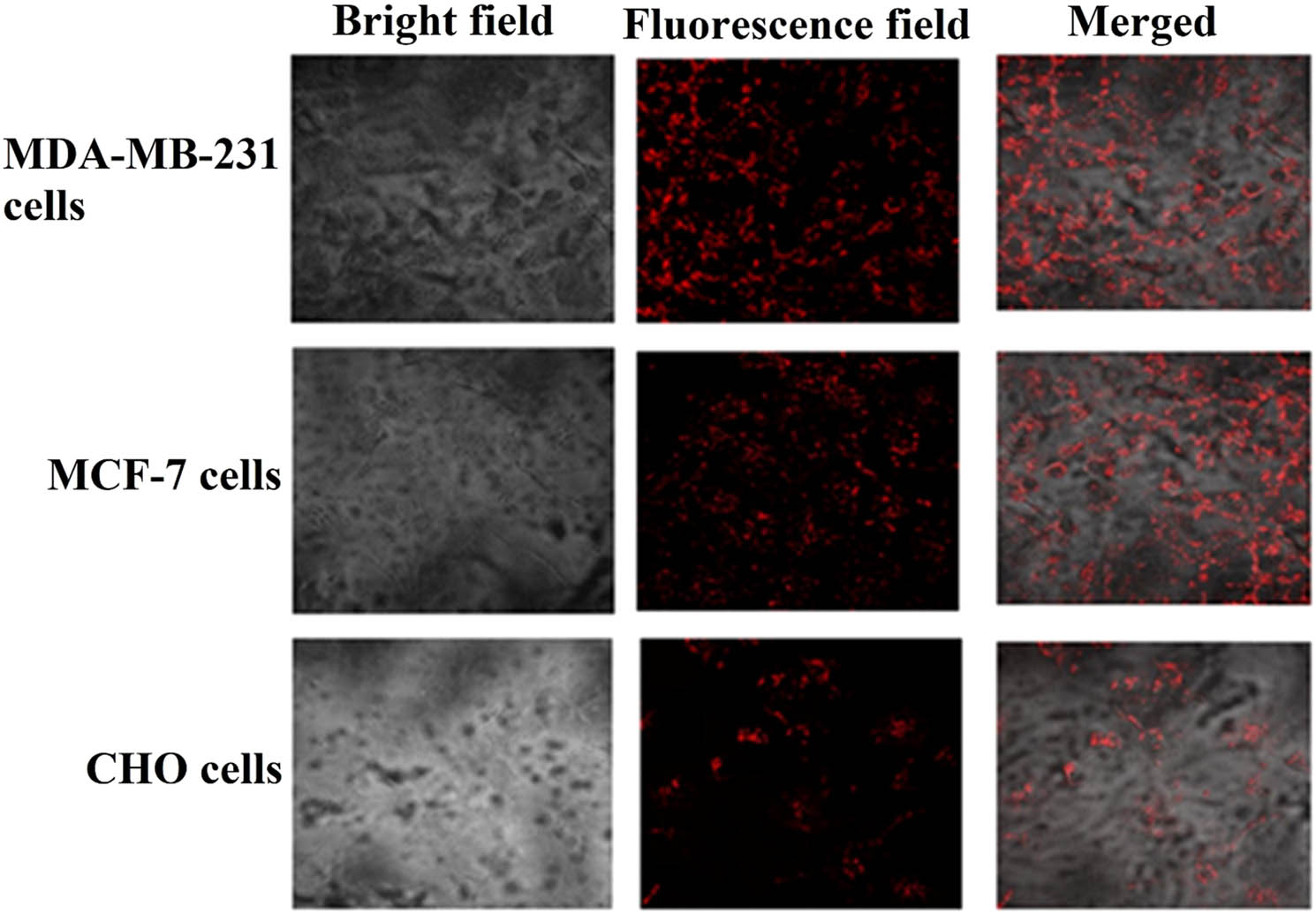

3.3 Cellular internalization of MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 complex

The in vitro experimental studies demonstrated that a surface decoration of nano-vesicles with aptamers could cause the enhancement of drug accumulation in targeted tumor sites [38]. For instance, Saravanakumar et al. designed aptamer-decorated CS NPs to deliver erlotinib to the A549 cell line. They have declared that the attachment of AS1411 aptamer to the nucleolin of A549 cell at the surface increased when transformed via a carrier system and improved the therapeutic efficiency [39]. Herein the specificity of AS1411 toward the cellular trapping of the MTX-CS-AuNPs-AS1411 complex in cancer cells as a cellular model expressing nucleolin protein was investigated. The obtained images of all cell lines displayed the potential of AS1411-functionalized NPs to enter breast cancer cells compared to CHO cells. As shown in Figure 3, MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 complex was successfully taken up by target cells, while less red fluorescence was observed in the CHO cells after treatment with MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 complex. These findings confirmed that the penetration of MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 into the intracellular matrix was higher than free MTX. Also, they indicated that AS1411-decorated AuNPs-CS could assist MTX in entering into the cancer cells (Figure 3).

The MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 cellular uptake by the cell lines using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

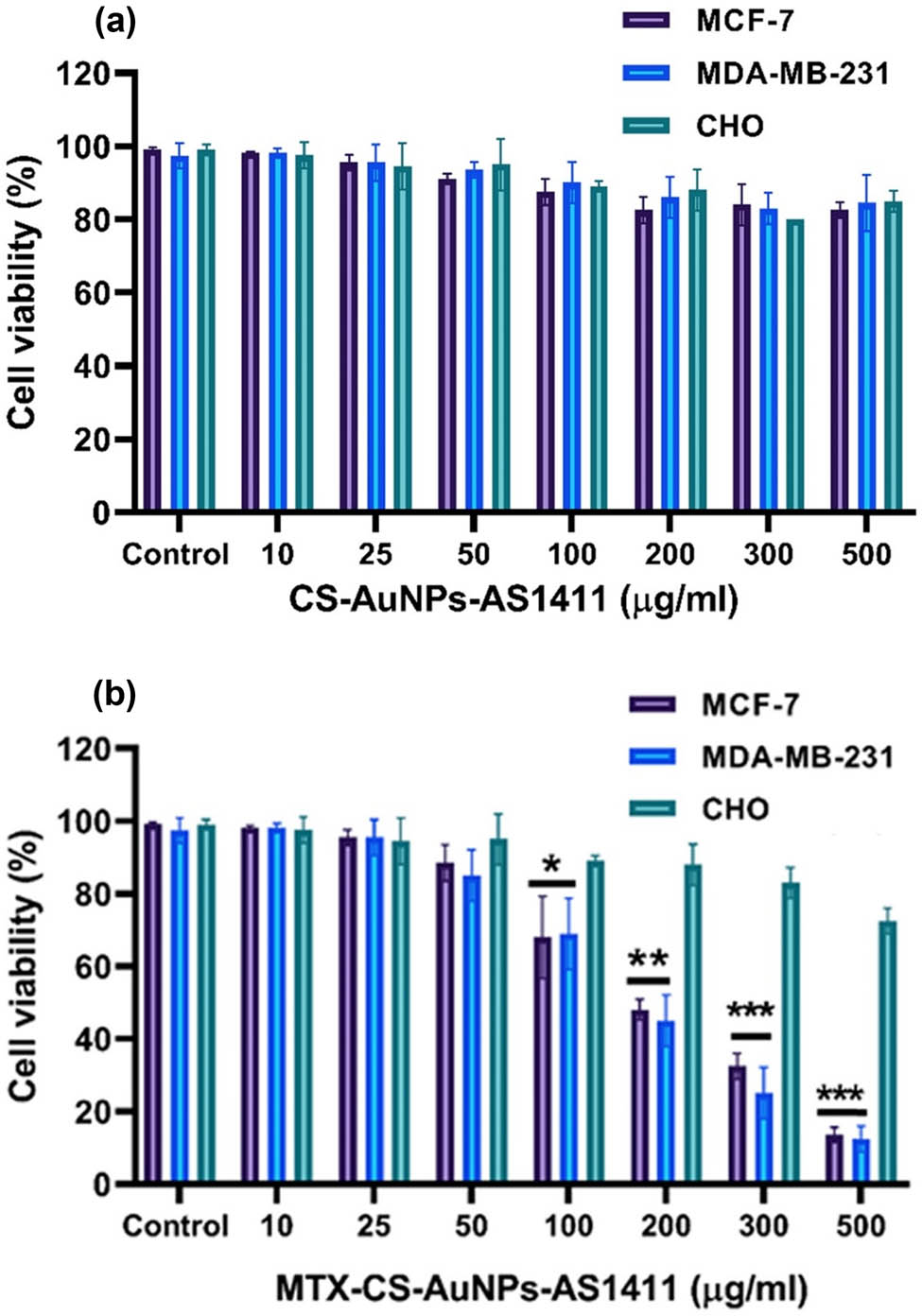

3.4 In vitro cell viability

From the research findings, the utilization of a delivery system for carrying MTX leads to a decrease in the drug’s toxic effects in the non-target cells. Zhao et al. reported that the cytotoxicity of MTX-loaded NPs against breast cancer cells and tumor tissues was raised appreciably compared to free MTX [40]. Therefore, to explore the in vitro efficiency of MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs, the cytotoxicity of free MTX, MTX-CSNPs, and MTX-AS1411-AuNPs-CS was tested on the cell lines using MTT assay. The presented result in Figure 4a revealed that cells treated with CS-AuNPs-AS1411 show no major impact on the viability of cells at all concentrations, which confirmed the biocompatibility of CS-AuNPs-AS1411. Moreover, it was notable that an increase in the concentration of MTX-CS-AuNPs-AS1411 could diminish the survivability of both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, but no noteworthy decrease in the viability of normal CHO cells was observed. Thus, it was concluded that the designed MTX-AS1411-AuNPs-CS has no toxic effect on non-target cells (Figure 4b).

(a) Effect of Apt-AuNPs-CS (without MTX) and (b) MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS on CHO (non-target), MDA-MB-231 (target), and MCF-7 (target) cell viabilities. The values are stated as mean value ± SD. * p < 0.05 shows significant differences.

3.5 The MMP (ΔΨm)

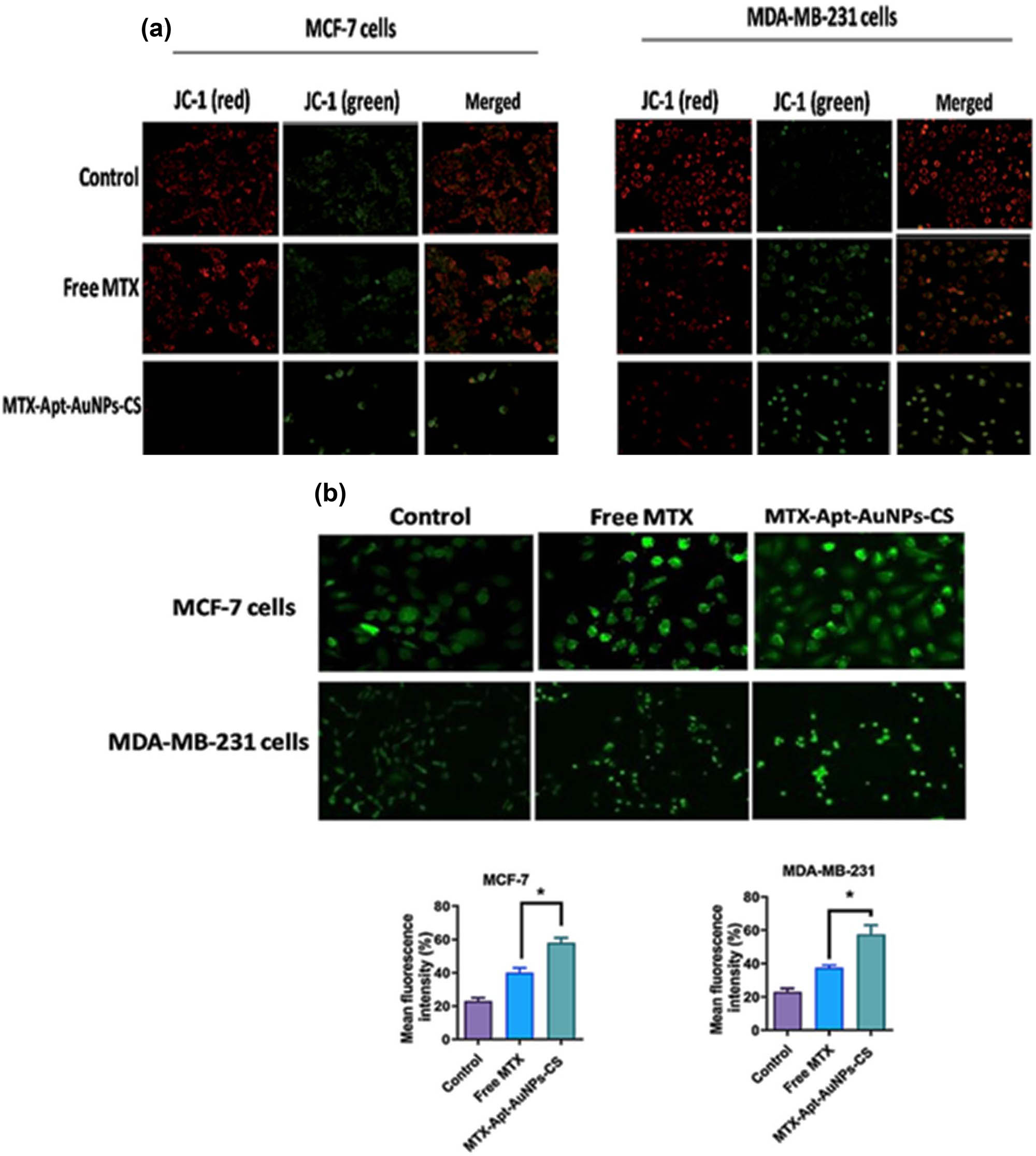

In this step, the morphological changes in the mitochondrial membranes of the target cells were examined via staining the cancer cells with JC-1, a mitochondrial fluorescent dye. The cells were subjected to free MTX and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS complex for 24 h. Next the MMP (ΔΨm) disruption was visualized under a fluorescent microscope. Mitochondrial membranes can be detected by the JC-1 and emit red fluorescence light. When the MMP is disrupted, JC-1 cannot aggregate into the mitochondrial membrane and remains monomeric in the cytoplasm that emits green fluorescence. According to fluorescence images, the mean fluorescence intensity changed from red to green in the target cells after exposure to MTX and MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS for 24 h, representing the Δψm loss due to the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane. However, the JC-1 dye showed a more intense green fluorescence in the MTX-Apt-AuNPs-CS treatment group than in the free MTX treatment group (Figure 5a).

(a) Determination of MMP (ΔΨm) disruption by JC-1 dye and (b) ROS using fluorescence microscopy (400× magnification). * p < 0.05 shows significant differences.

3.6 ROS generation

The obtained data showed a release of MTX upon entry into the cytoplasm, which caused overproduction of intracellular ROS and induction of oxidative stress situation. As displayed in Figure 5b, the ROS levels were higher in cancer cells treated with MTX-AS1411-AuNPs-CS and free MTX than in untreated cells. The results showed an increased fluorescence intensity in the target cells exposed to MTX-AS1411-AuNPs-CS compared to free MTX, indicating that the MTX delivered by the vehicle was able to generate ROS and induce DNA damage and apoptosis (Figure 5b).

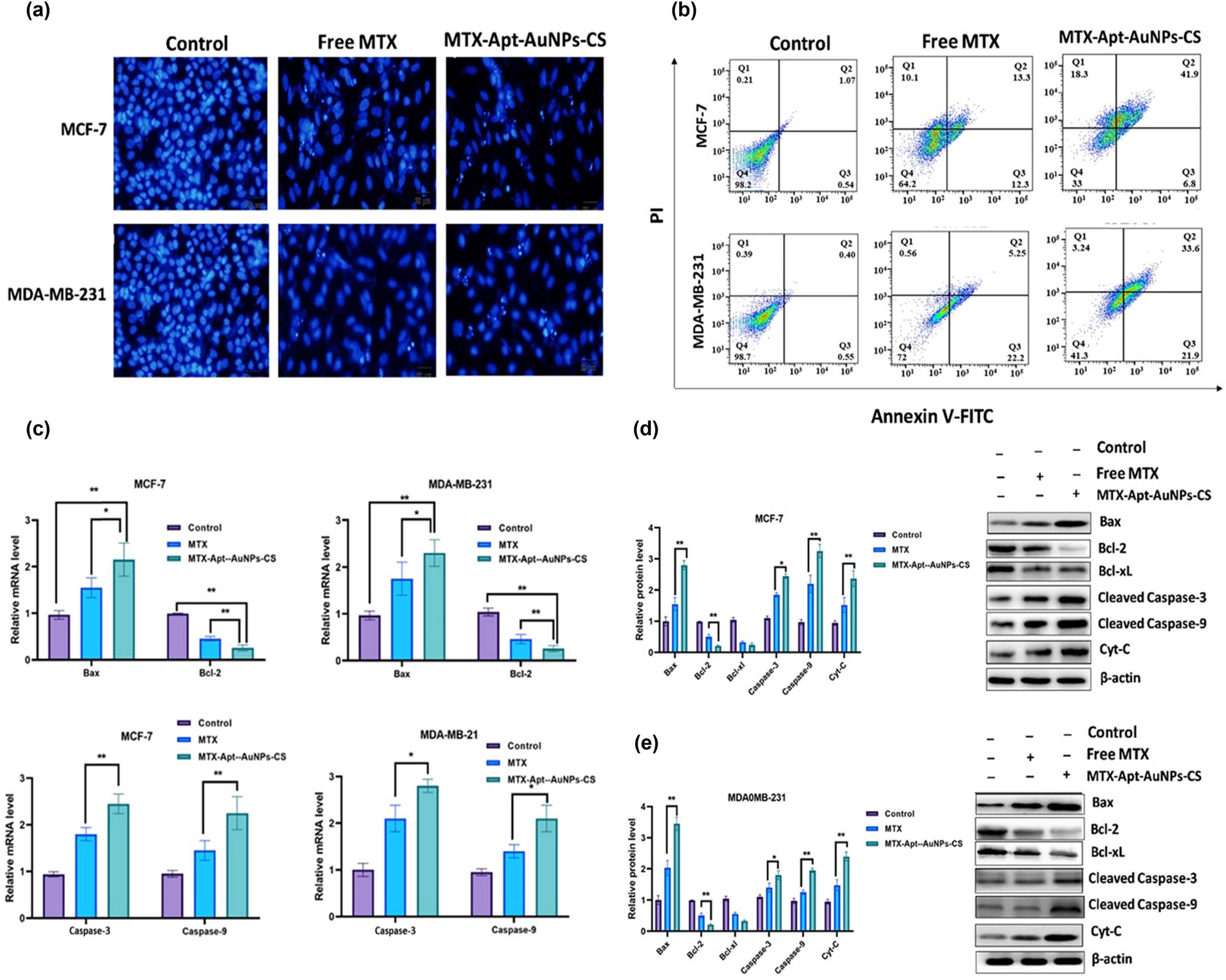

3.7 Apoptosis analysis

Generally, an increase in intracellular ROS levels and the magnitude of damage to DNA and mitochondria confirm the cell’s fate proceeding toward the apoptosis pathway. In both the cancer cell lines, the nuclear fragmentation was apperceived by Hoechst and DAPI staining after MTX-CS-AuNPs-AS1411 exposure. The DAPI fluorescent dye forms the dsDNA adducts by which the condensation of apoptotic cell nuclei is detectable. Figure 6a shows that the control group had standard intact nuclei. However, the MTX-treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells have abnormal features such as partially fragmented nuclei (Figure 6a). Hence, the number of fragmented cell nuclei were grown after MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs uptake by the target cells. Therefore, the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex approved its capability of triggering apoptosis. Therefore, to measure the apoptosis rate of the complex, flow cytometry using annexin V and PI staining methods was used. In Figure 6b, free MTX demonstrated acceptable anti-tumoral activity in the cells at 25 and 28%, respectively. While exposing the cells to functionalized complexes, the death rate rose to 48.5 and 55.5% after incubation for 24 h, respectively. Moreover, after the treatment with the therapeutic drugs, the expression levels of anti-apoptotic and apoptotic markers in the target cells were evaluated using q-RT-PCR and western blotting analyses. The results exhibited that the utilization of the delivery system could downregulate the expression of anti-apoptosis protein (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) and upregulate apoptosis-related markers (Cyt-C, Bax, cleaved-caspase-3, and cleaved-caspase-9) compared with MTX alone or control groups (Figure 6c–e).

The target cells were incubated with free MTX and MTX-AuNCs-CS-AS1411, and then apoptosis was assessed using (a) DAPI staining by inverted fluorescent microscope and (b) flow cytometry. The apoptosis-related markers were investigated using (c) real-time PCR, and (d, e) western blotting. β-actin was considered as an internal control. * p < 0.05 shows significant differences.

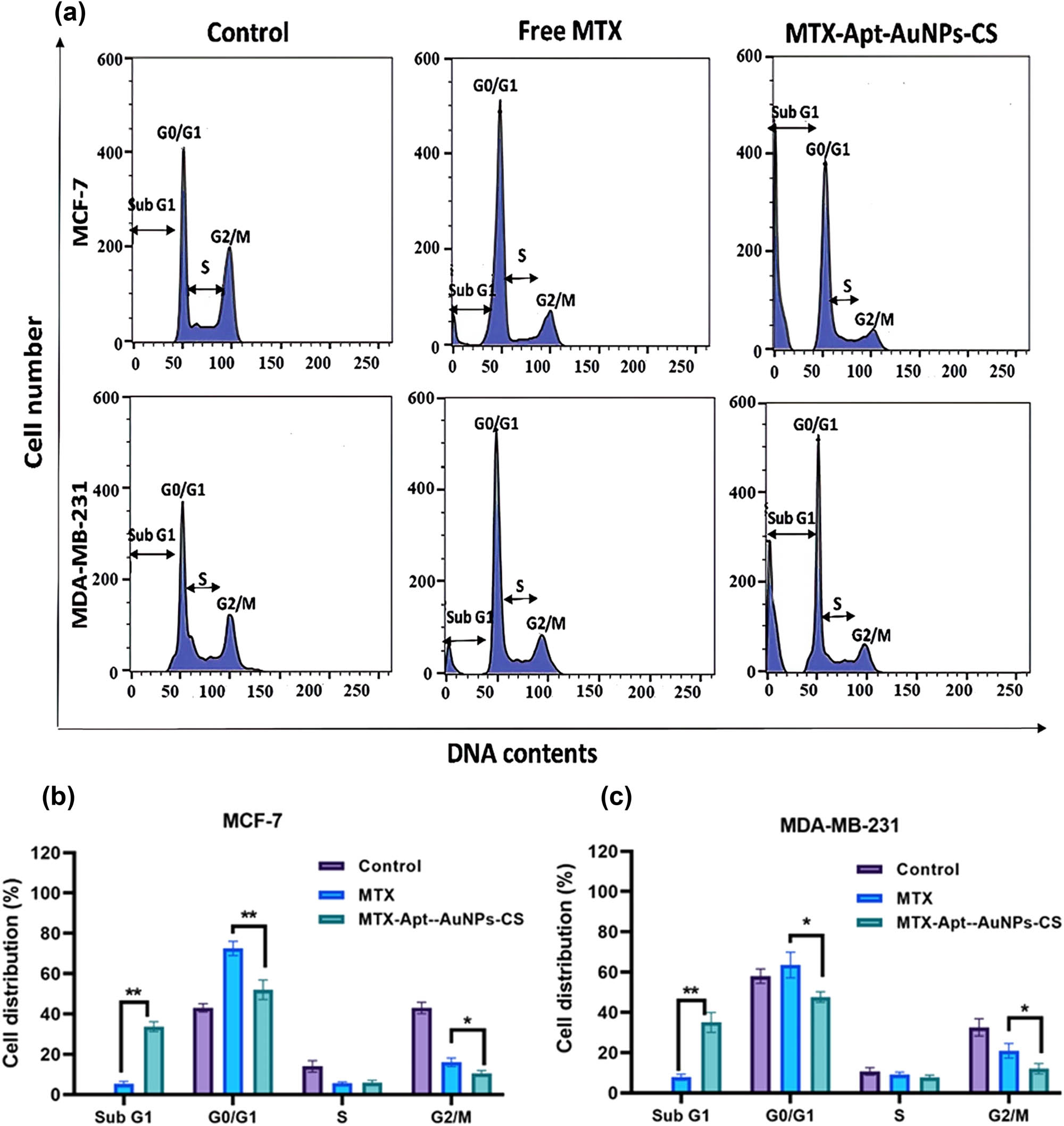

3.8 Cell cycle analysis

The cell cycle of the target cells was evaluated by being subjected to MTX and MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex and conducting a flow cytometry and PI staining. Treatment of cells with free MTX showed some alterations in cell cycles in both cell lines, including a reduction in cancer cell percentage in phase S. Interestingly, cell treatment with MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex increased the cell percentage in sub Go/G1 as a sign of apoptosis (Figure 7). It should be noted that the molecular event of cell cycle arrest is crucial for dealing with the rapid growth of cancer cells. Generally, the cell cycle events are classified into G1, S, and G2 interphases and mitotic (M) stages, which are disturbed under cellular stress [41]. Therefore, a constant high level of MTX-AuNCs-CS-AS1411 complex in the cell lines confirmed the potential of the complex to impel cell cycle arrest to a remarkable extent.

(a) Cell cycle distribution histograms of the target cells. Relative cell cycle distribution of Sub G1, Go/G1, S, and G2 phases in (b) MCF-7 and (c) MDA-MB-231. * p < 0.05 shows significant differences.

The in vitro results were similar to the prior works [42,43]. Mechanistically, MTX could bind to folate receptor and suppress the activity of dihydrofolate reductase, and in turn, impair DNA synthesis, inhibit cell proliferation, and finally induce cell death in the rapidly proliferating cancer cells [11]. Accumulative evidence potentially revealed that the MTX conjugation with the suitable NPs could preserve its attachment to the folate receptor and simultaneously avoid its premature release to decrease the severe toxic effects on healthy tissues during chemotherapy [10]. We have exhibited that the designed nano-system could enhance the drug uptake into the target cells. Our findings indicated that the anti-cancer activity of MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex against the breast cancer cells was higher than that of the free MTX. MTX released from the vehicle could potentially reduce cell viability in the target cells, disrupt the mitochondrial membrane, cause nuclear fragmentation, and cause subsequent apoptotic cell death and cell cycle arrest. Our results suggested that the MTX-AS1411-CS-AuNPs complex might be a promising drug delivery system, especially for breast carcinoma. The anti-cancer effects of this nano-complex as an in vivo system will be investigated.

3.8.1 In vivo study

Tumor-bearing BALB/c mice were employed to investigate the antitumoral activity of MTX in the MTX-AuNCs-CS-AS1411 complex. For this purpose, mice were intravenously subjected to the complex, free MTX, and PBS. As displayed in Figure 8a, the utilization of a delivery system could affect tumor suppression more than those treated with MTX alone or PBS groups (p < 0.01). To evaluate the possible side effects, the bodyweight loss and organ indexes were monitored. As reported in Figure 8b, compared to the mice treated with PBS, no considerable alternation in the bodyweight of the mice exposed to MTX-AuNCs-CS-AS1411 was observed. The main organ (liver, spleen, and kidney) tissues were removed and weighed to calculate the organ indexes. The measured ratio were as listed in Figure 8(c–e). Likewise, no considerable alteration was observed between the control and experimental groups in organ indexes.

(a) Tumor size, (b) the bodyweight, and (c–e) the organ indexes (liver, spleen, and kidney) of mice after treatment with PBS, free MTX, and MTX-Apt-CS-AuNPs. (f) The fluorescence intensities of mice after 4 h post injection with PBS, free MTX, and MTX-Apt-CS-AuNPs to monitor the targeting effects. **p < 0.01 shows significant differences.

Moreover, to evaluate the targeting effects of therapeutic drugs, the fluorescence intensities of major organs and tumors were monitored after 4 h of the last injection. The images indicated that the red light was primarily accumulated in the tumor side subjected by the MTX-AuNPs-CS-AS1411 compared to the free MTX. The high entrapment of the complex in cancer sites could be associated with its tumor targeting potential of AS1411 aptamer (Figure 8f).

4 Conclusion

In this experiment, we successfully designed the AuNCs-CS-AS1411 system to deliver MTX to MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells and breast tumor site. In vitro cellular internalization studies revealed that the designed nano-system could successfully enter into tumor cells, superior to AS1411 as a targeting ligand. Our data showed that MTX released from the vehicle in the target cells could reduce cancer cell viability, disrupt the mitochondrial membrane, cause nuclear fragmentation, and cause subsequent apoptotic cell death and cell cycle arrest. Also, the synthesized nano-system could selectively deliver MTX to the target tumor site and reduce the systematic adverse effect of this chemotherapeutic drug. The results demonstrated a major anti-tumoral activity on the cancer cell lines and minor toxicity on healthy tissues.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals’ use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

References

[1] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.10.3322/caac.21660Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Schirrmacher V. From chemotherapy to biological therapy: A review of novel concepts to reduce the side effects of systemic cancer treatment. Int J Oncol. 2019;54:407–19.10.3892/ijo.2018.4661Search in Google Scholar

[3] Senapati S, Mahanta AK, Kumar S, Maiti P. Controlled drug delivery vehicles for cancer treatment and their performance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3:1–19.10.1038/s41392-017-0004-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Abtahi NA, Naghib SM, Ghalekohneh SJ, Mohammadpour Z, Nazari H, Mosavi SM, et al. Multifunctional stimuli-responsive niosomal nanoparticles for co-delivery and co-administration of gene and bioactive compound: In vitro and in vivo studies. Chem Eng J. 2022;429:132090. 10.1016/j.cej.2021.132090.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Mazidi Z, Javanmardi S, Naghib SM, Mohammadpour Z. Smart stimuli-responsive implantable drug delivery systems for programmed and on-demand cancer treatment: An overview on the emerging materials. Chem Eng J. 2022;433:134569. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.134569.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Yaghoubi F, Naghib SM, Motlagh NSH, Haghiralsadat F, Jaliani HZ, Tofighi D, et al. Multiresponsive carboxylated graphene oxide-grafted aptamer as a multifunctional nanocarrier for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics and bioactive compounds in cancer therapy. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10:1838–52. 10.1515/ntrev-2021-0110.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Abtahi NA, Naghib SM, Haghiralsadat F, Reza JZ, Hakimian F, Yazdian F, et al. Smart stimuli-responsive biofunctionalized niosomal nanocarriers for programmed release of bioactive compounds into cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10:1895–911. 10.1515/ntrev-2021-0119.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Rahimzadeh Z, Naghib SM, Askari E, Molaabasi F, Sadr A, Zare Y, et al. A rapid nanobiosensing platform based on herceptin-conjugated graphene for ultrasensitive detection of circulating tumor cells in early breast cancer. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10:744–53. 10.1515/ntrev-2021-0049.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Shakeran Z, Keyhanfar M, Varshosaz J, Sutherland DS. Biodegradable nanocarriers based on chitosan-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles for delivery of methotrexate for application in breast cancer treatment. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;118:111526.10.1016/j.msec.2020.111526Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Fathi M, Barar J, Erfan-Niya H, Omidi Y. Methotrexate-conjugated chitosan-grafted pH-and thermo-responsive magnetic nanoparticles for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;154:1175–84.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.272Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Panji M, Behmard V, Zare Z, Malekpour M, Nejadbiglari H, Yavari S, et al. Synergistic effects of green tea extract and paclitaxel in the induction of mitochondrial apoptosis in ovarian cancer cell lines. Gene. 2021;787:145638.10.1016/j.gene.2021.145638Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Johari-Ahar M, Barar J, Alizadeh AM, Davaran S, Omidi Y, Rashidi M-R. Methotrexate-conjugated quantum dots: synthesis, characterisation and cytotoxicity in drug resistant cancer cells. J Drug Target. 2016;24:120–33.10.3109/1061186X.2015.1058801Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Amina SJ, Guo B. A review on the synthesis and functionalization of gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery vehicle. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:9823.10.2147/IJN.S279094Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Park SJ. Protein–nanoparticle interaction: corona formation and conformational changes in proteins on nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:5783.10.2147/IJN.S254808Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Mohammed MA, Syeda J, Wasan KM, Wasan EK. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2017;9:53.10.3390/pharmaceutics9040053Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Gooneh-Farahani S, Naghib SM, Naimi-Jamal MR, Seyfoori A. A pH-sensitive nanocarrier based on BSA-stabilized graphene-chitosan nanocomposite for sustained and prolonged release of anticancer agents. Sci Rep. 2021;11:17404. 10.1038/s41598-021-97081-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Gooneh-Farahani S, Naghib SM, Naimi-Jamal MR. A novel and inexpensive method based on modified ionic gelation for pH-responsive controlled drug release of homogeneously distributed chitosan nanoparticles with a high encapsulation efficiency. Fibers Polym. 2020;21:1917–26. 10.1007/s12221-020-1095-y.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang W, Meng Q, Li Q, Liu J, Zhou M, Jin Z, et al. Chitosan derivatives and their application in biomedicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:487.10.3390/ijms21020487Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Jhaveri J, Raichura Z, Khan T, Momin M, Omri A. Chitosan nanoparticles-insight into properties, functionalization and applications in drug delivery and theranostics. Molecules. 2021;26:272.10.3390/molecules26020272Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Briolay T, Petithomme T, Fouet M, Nguyen-Pham N, Blanquart C, Boisgerault N. Delivery of cancer therapies by synthetic and bio-inspired nanovectors. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:1–24.10.1186/s12943-021-01346-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Zhang Y, Lai BS, Juhas M. Recent advances in aptamer discovery and applications. Molecules. 2019;24:941.10.3390/molecules24050941Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Shahidi M, Abazari O, Bakhshi A, Zavarreza J, Modarresi M, Haghiralsadat F, et al. Multicomponent siRNA/miRNA-loaded modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles targeted bladder cancer for a highly effective combination therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:949704. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.949704.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Panji M, Behmard V, Zare Z, Malekpour M, Nejadbiglari H, Yavari S, et al. Suppressing effects of Green tea extract and Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on TGF-β-induced Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via ROS/Smad signaling in human cervical cancer cells. Gene. 2021;794:145774.10.1016/j.gene.2021.145774Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Mu W, Chu Q, Liu Y, Zhang N. A review on nano-based drug delivery system for cancer chemoimmunotherapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020;12:1–24.10.1007/s40820-020-00482-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Franconetti A, Carnerero JM, Prado-Gotor R, Cabrera-Escribano F, Jaime C. Chitosan as a capping agent: Insights on the stabilization of gold nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;207:806–14.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.12.046Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Lai C, Liu X, Qin L, Zhang C, Zeng G, Huang D, et al. Chitosan-wrapped gold nanoparticles for hydrogen-bonding recognition and colorimetric determination of the antibiotic kanamycin. Microchim Acta. 2017;184:2097–105.10.1007/s00604-017-2218-zSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Kukreti S, Kaushik M. Exploring the DNA damaging potential of chitosan and citrate-reduced gold nanoparticles: physicochemical approach. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;115:801–10.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Vandghanooni S, Eskandani M, Barar J, Omidi Y. AS1411 aptamer-decorated cisplatin-loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for targeted therapy of miR-21-inhibited ovarian cancer cells. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:2729–58.10.2217/nnm-2018-0205Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EVR, del Pilar Rodriguez-Torres M, Acosta-Torres LS, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:1–33.10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Gaumet M, Vargas A, Gurny R, Delie F. Nanoparticles for drug delivery: the need for precision in reporting particle size parameters. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;69:1–9.10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Prabha S, Arya G, Chandra R, Ahmed B, Nimesh S. Effect of size on biological properties of nanoparticles employed in gene delivery. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44:83–91.10.3109/21691401.2014.913054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Mohan CO, Gunasekaran S, Ravishankar CN. Chitosan-capped gold nanoparticles for indicating temperature abuse in frozen stored products. Npj Sci Food. 2019;3:1–6.10.1038/s41538-019-0034-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Tyagi H, Kushwaha A, Kumar A, Aslam M. A facile pH controlled citrate-based reduction method for gold nanoparticle synthesis at room temperature. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11:1–11.10.1186/s11671-016-1576-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Tsai M-L, Chen R-H, Bai S-W, Chen W-Y. The storage stability of chitosan/tripolyphosphate nanoparticles in a phosphate buffer. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;84:756–61.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.04.040Search in Google Scholar

[35] Saleh NM, Aziz AA. Simulation of surface plasmon resonance on different size of a single gold nanoparticle. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1083, IOP Publishing; 2018, p. 12041.10.1088/1742-6596/1083/1/012041Search in Google Scholar

[36] Luo F, Li Y, Jia M, Cui F, Wu H, Yu F, et al. Validation of a Janus role of methotrexate-based PEGylated chitosan nanoparticles in vitro. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9:1–13.10.1186/1556-276X-9-363Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Rosenholm JM, Peuhu E, Bate-Eya LT, Eriksson JE, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Cancer-cell-specific induction of apoptosis using mesoporous silica nanoparticles as drug-delivery vectors. Small. 2010;6:1234–41.10.1002/smll.200902355Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Zhu G, Chen X. Aptamer-based targeted therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;134:65–78.10.1016/j.addr.2018.08.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Saravanakumar K, Sathiyaseelan A, Mariadoss AVA, Jeevithan E, Hu X, Shin S, et al. Dual stimuli-responsive release of aptamer AS1411 decorated erlotinib loaded chitosan nanoparticles for non-small-cell lung carcinoma therapy. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;245:116407.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116407Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Zhao Y, Guo Y, Li R, Wang T, Han M, Zhu C, et al. Methotrexate nanoparticles prepared with codendrimer from polyamidoamine (PAMAM) and oligoethylene glycols (OEG) dendrons: Antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–11.10.1038/srep28983Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Goel S, DeCristo MJ, McAllister SS, Zhao JJ. CDK4/6 inhibition in cancer: beyond cell cycle arrest. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:911–25.10.1016/j.tcb.2018.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Ciro Y, Rojas J, Di Virgilio AL, Alhajj MJ, Carabali GA, Salamanca CH. Production, physicochemical characterization, and anticancer activity of methotrexate-loaded phytic acid-chitosan nanoparticles on HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;243:116436.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116436Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Akbari E, Mousazadeh H, Sabet Z, Fattahi T, Dehnad A, Akbarzadeh A, et al. Dual drug delivery of trapoxin A and methotrexate from biocompatible PLGA-PEG polymeric nanoparticles enhanced antitumor activity in breast cancer cell line. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;61:102294.10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102294Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Maryamsadat Shahidi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions