Abstract

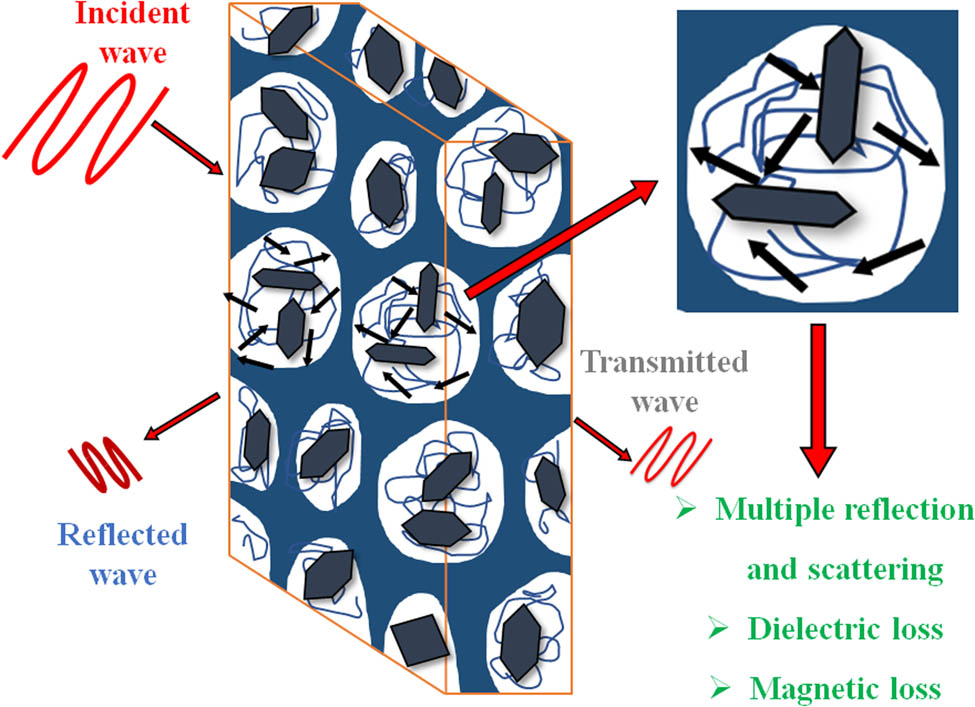

Lightweight and high-performance electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials are urgently required to solve increasingly serious radiation pollution. However, traditional lightweight EMI shielding materials usually show low EMI shielding performance, poor mechanical properties, and environmental stability, which greatly limit their practical applications. Herein Ni foam/graphene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol (Ni/GO/PVA) composite aerogels were successfully prepared by a freeze-drying method. The Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels possessed low density (189 mg cm−3) and high compression strength (172.2 kPa) and modulus (5.5 MPa). The Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogel was hydrophobic, and their contact angle can reach 145.2°. The hydrophobic modification improved the environmental stability of the composite aerogels. Moreover, the Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels exhibited excellent EMI shielding performance. Their maximum EMI shielding effectiveness (SE) can reach 87 dB at the thickness of 2.0 mm. When the thickness is only 1.0 mm, the EMI SE can still reach 60 dB. The electromagnetic energy absorption and attenuation mechanisms of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels include multiple reflection and scattering, dielectric loss, and magnetic loss. This work provides a promising approach for the design and preparation of the lightweight EMI shielding materials with superior EMI SE, which may be applied in various fields such as aircrafts, spacecrafts, drones, and robotics.

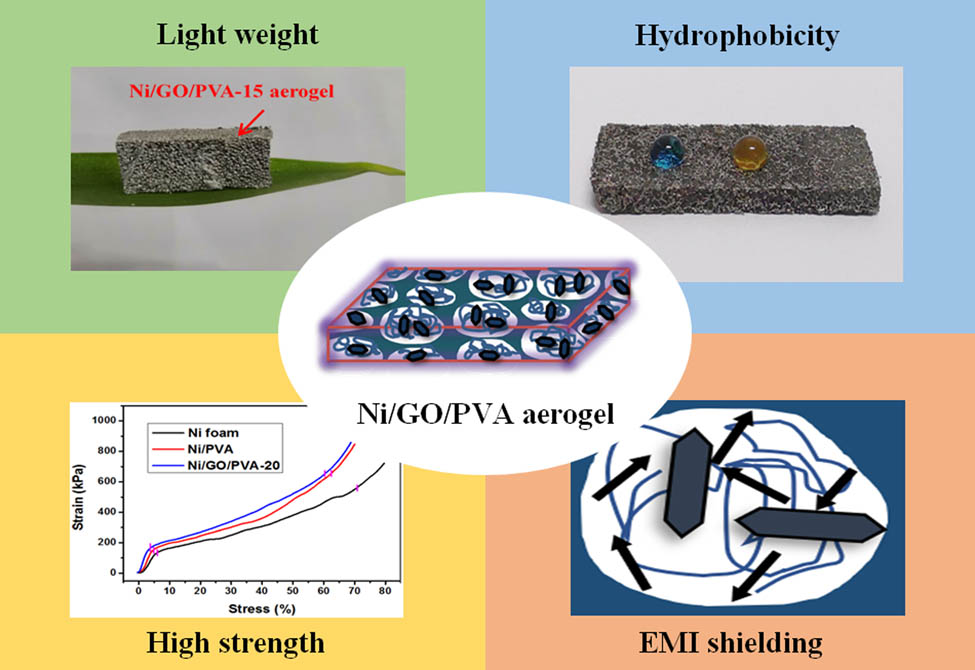

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of communication technology, electronic devices have been widely used in our daily life [1,2,3,4]. When these devices transmit or receive electrical signals, electromagnetic waves are inevitably generated [5]. Electromagnetic radiation not only affects the reliability and lifetime of precision equipment, but also threatens human health [6,7,8]. Undoubtedly, the development of high-performance electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials is one of the effective strategies to solve the above problems [9,10]. EMI shielding materials are very important in equipment with special-needs, which are widely used in communications, electronics, aerospace, military, navigation, medical, and many other fields. Traditional EMI shielding materials such as metals, have excellent EMI shielding properties, but the intrinsic high density and poor corrosion resistance limit their practical applications [11,12,13].

Recently, carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers, graphene, or their hybrids, have become popular alternatives for EMI shielding applications because of their lightweight, chemical stability, flexibility, and good mechanical properties [1,14–23]. For example, Wei et al. [24] synthesized a freestanding highly aligned laminated graphene film by a scalable scanning centrifugal casting method, which showed an EMI shielding effectiveness (SE) of 93 dB at a thickness of ≈100 µm. Jia et al. [25] fabricated a freestanding and ultrathin graphene oxide/silver nanowire (GO/Ag) film by a vacuum-assisted self-assembly method, which had an EMI SE of 62 dB at a thickness of merely 8 µm. Rani et al. [26] prepared a polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan/graphite oxide/nickel oxide (PVA/CS/GO/NiO) nanocomposite film using solution casting technique, and the EMI SE value was 12 dB for nanocomposite film containing 3.0/30 wt% of GO/NiO. Although some achievements have been realized in carbon-based EMI shielding materials, the densities of the reported materials are still not low enough for EMI shielding materials in aerospace industry. Exploring the simple and efficient methods to prepare lightweight EMI shielding materials with superior EMI SE value is still a challenge.

Porous materials such as aerogels, foams, and sponges are ideal candidates for lightweight EMI shielding materials due to their unique 3D skeleton structure and ultralow density [27–29]. More importantly, the porous structures are conducive to multiple internal reflection and absorption of electromagnetic waves [30]. Li et al. [31] fabricated a graphene aerogel with multilayer structure via mechanical compression, which showed high electrical conductivity (181.8 S m−1) and EMI shielding performance (43 dB at thickness of 2.5 mm). Yu et al. [32] fabricated an anisotropic polyimide/graphene composite aerogel by unidirectional freezing and freezing drying, which exhibited EMI SE of 26–28 dB at thickness of 2.5 mm when the graphene content was 13 wt%. Yang et al. [33] prepared a 3D copper nanowires-thermally annealed graphene aerogel (CuNWs-TAGA) framework by freeze-drying followed by thermal annealing, which showed the maximum EMI SE value of 47 dB at thickness of 3.0 mm, ascribed to perfect 3D CuNWs-TAGA conductive network structures. Wang et al. [34] constructed a CNT/graphene/polyimide foam with stable compressibility and perfect conductive networks. The resultant composite foam exhibited an average EMI SE of 28 dB at thickness of 2.0 mm. However, the EMI shielding performance of these porous materials is relatively poor, especially at small thickness (≤2.0 mm), which cannot meet the increasingly demanding application requirements. It remains a challenge to maximize the EMI shielding performance at low density and small thickness through the rational design of the composition and structure.

From graphical abstract, we successfully designed and fabricated Ni/GO/PVA aerogels by freeze-drying process, which possess lightweight, hydrophobicity, high compression strength, and superior EMI shielding performance. The GO in aerogel was dispersed in PVA, which greatly increased the heterogeneous contact area and enhanced the interfacial polarization effect. The porous structure makes the electromagnetic wave be reflected and scattered many times, which increases the propagation distance of the electromagnetic wave. Combined with Ni foam with high conductivity and permeability, reflecting the large number of incoming electromagnetic waves, the synergistic effect of dielectric and magnetic loss improves the EMI SE of the materials. In addition, the hydrogen bonding between GO and PVA improves the mechanical properties of the material. The surface energy of the material after hydrophobic treatment is low, and the droplets can roll on the surface, which realizes the self-cleaning function and improves the corrosion resistance. This design and fabrication strategy provides high-potential for the practical application of EMI shielding materials.

2 Materials and specimens

2.1 Materials

GO was purchased from Tangshan JianHua Technology Development Co., Ltd. PVA (MW: ∼195,000) was purchased from Beijing Yili Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd. Ni foam (density: 8 mg cm−3) was obtained from Kunshan Guangsheng jianeng Materials Co., Ltd. 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane (FAS-17, >96% purity) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd.

2.2 Preparation of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels

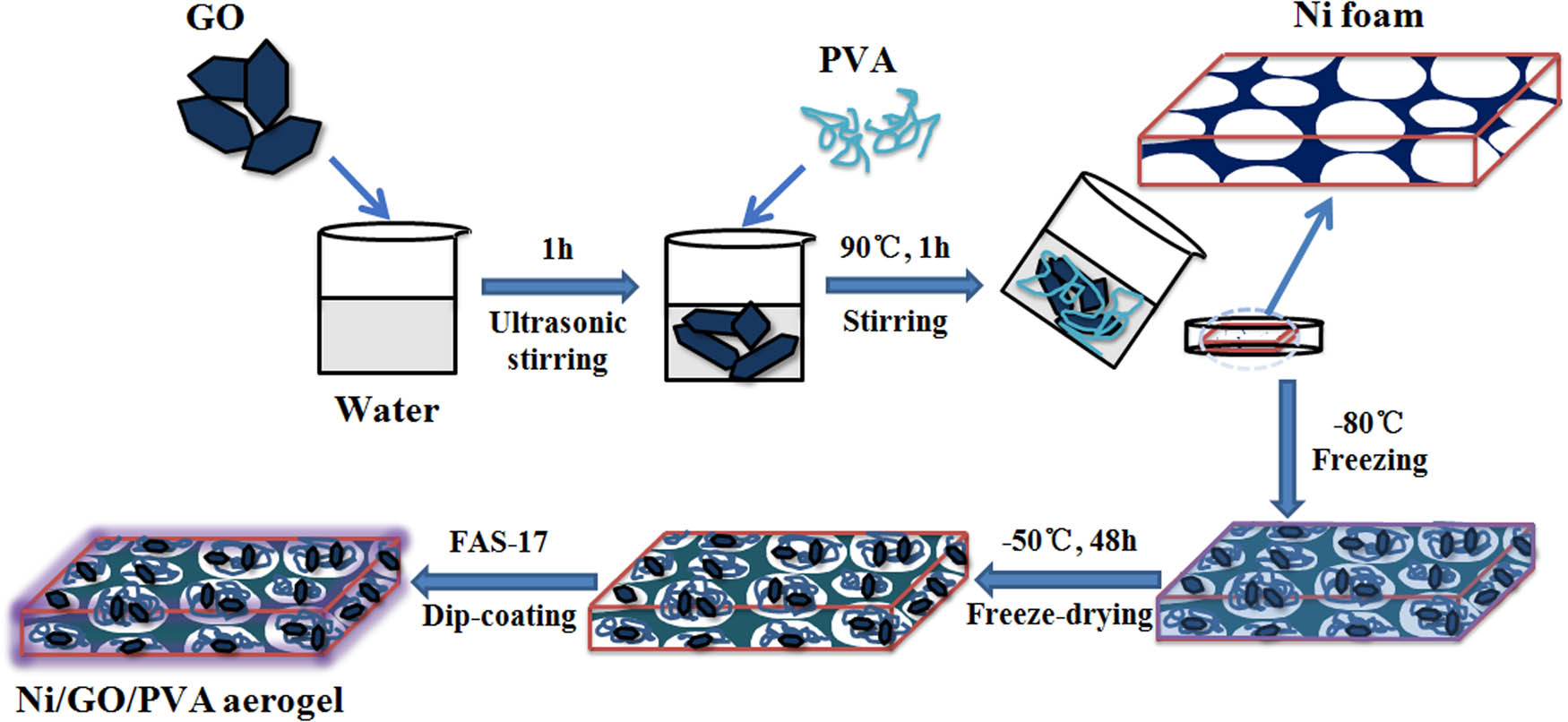

Figure 1 shows the preparation process of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels. Four Ni/GO/PVA aerogels with GO content were prepared, and the mass of GO accounted for 5, 10, 15, and 20% of GO and PVA mass, and were named Ni/GO/PVA-5, Ni/GO/PVA-10, Ni/GO/PVA-15, and Ni/GO/PVA-20, respectively. First, taking Ni/Go/PVA-15 as an example, 0.18 g GO was added into 50 mL of deionized water, after ultrasonic stirring, 1.00 g PVA was added into GO dispersion, and stirred in 80°C water bath for 1 h, PVA is completely dissolved and GO/PVA dispersion is obtained, which is left room temperature for cooling. Then, an appropriate size of Ni foam was into the mold; the GO/PVA dispersion was slowly poured into the mold until the Ni foam is not on the surface. It was put into a vacuum oven to remove bubbles. Then, the mold was placed in liquid nitrogen environment, and the GO/PVA dispersion was completely frozen. The mold was put into the freeze dryer and aerated at −50°C for 48 h to get Ni/GO/PVA aerogel. Without adding GO, Ni/PVA aerogels were prepared by the same method. 2.50 g FAS-17 was dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol, and the aerogels were extracted for 10 min and removed at 135°C for 30 min. The hydrophobic modified Ni/GO/PVA aerogels were obtained.

Preparation process of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels.

2.3 Characterization

The morphology and microstructure were observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (HITACHI SU8010). The mechanical properties of the aerogels were tested using an electronic universal testing machine (SHIMADZU AGS-X) equipped with a 2-kN load cell at a loading rate of 5 mm min−1 in compression mode. The aerogels were cut into 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm, and each sample was tested 5 times under the same condition. The contact angles of the aerogels were measured with a contact angle goniometer (Dataphysics OCA 25) using deionized water droplets of 5 µL, at 5 different positions on the aerogel. The density of the aerogels was calculated from measured geometries and mass of the samples. The EMI shielding properties of the Ni/GO/PVA-5, Ni/GO/PVA-10, Ni/GO/PVA-15, and Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels were measured in a frequency range of 8.2–12.4 GHz (X-band) at room temperature by a vector network analyzer (Ceyear 3672b) using the waveguide method. The samples were cut into 22.86 mm × 10.16 mm × 2.0 mm (length × width × thickness) sizes to satisfy the waveguide holders. The power coefficients of reflection (R), transmission (T), and absorption (A) were calculated from the measured scattering parameters (S 11 and S 21). The total EMI SE (SET) can be evaluated based on the following equations [35,36]:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology and structure of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels

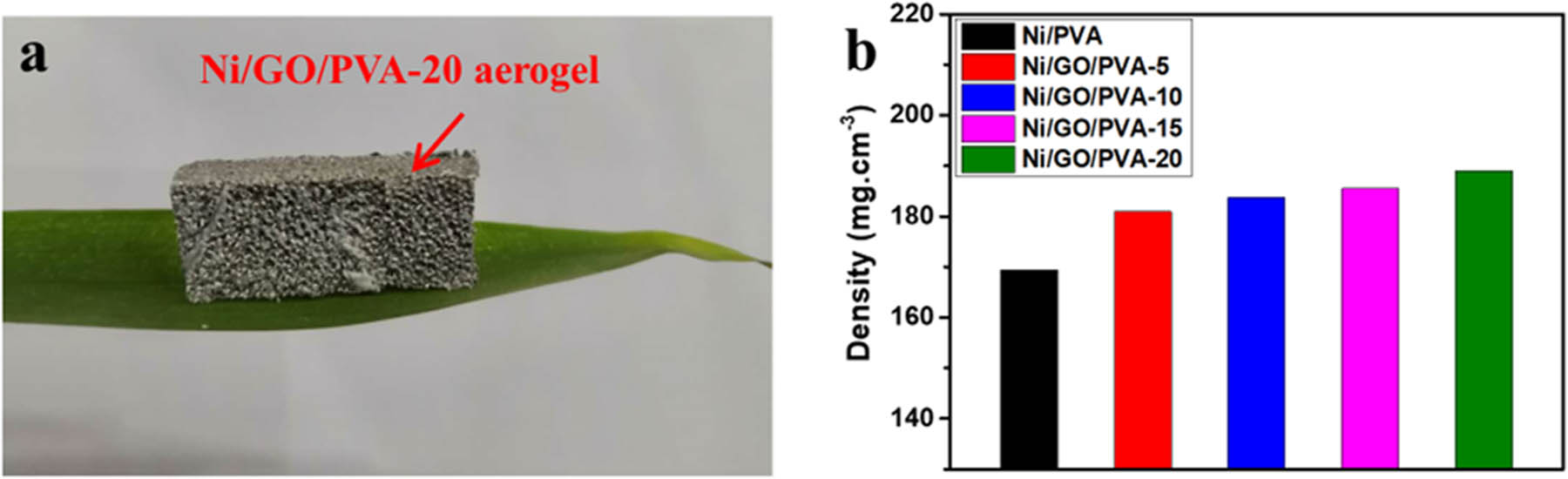

Figure 2(a) shows the porous structure of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels. Ni/GO/PVA aerogels are placed on bamboo leaves without bending the leaves, indicating that Ni/GO/PVA aerogels have very low density. Figure 2(b) compares the density of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels with different GO contents. It can be seen that the density of aerogels increases with the increase in GO content, and the density of Ni/GO/PVA-20 is 189 mg cm−3.

(a) Photograph of Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogel; (b) histogram of aerogel density.

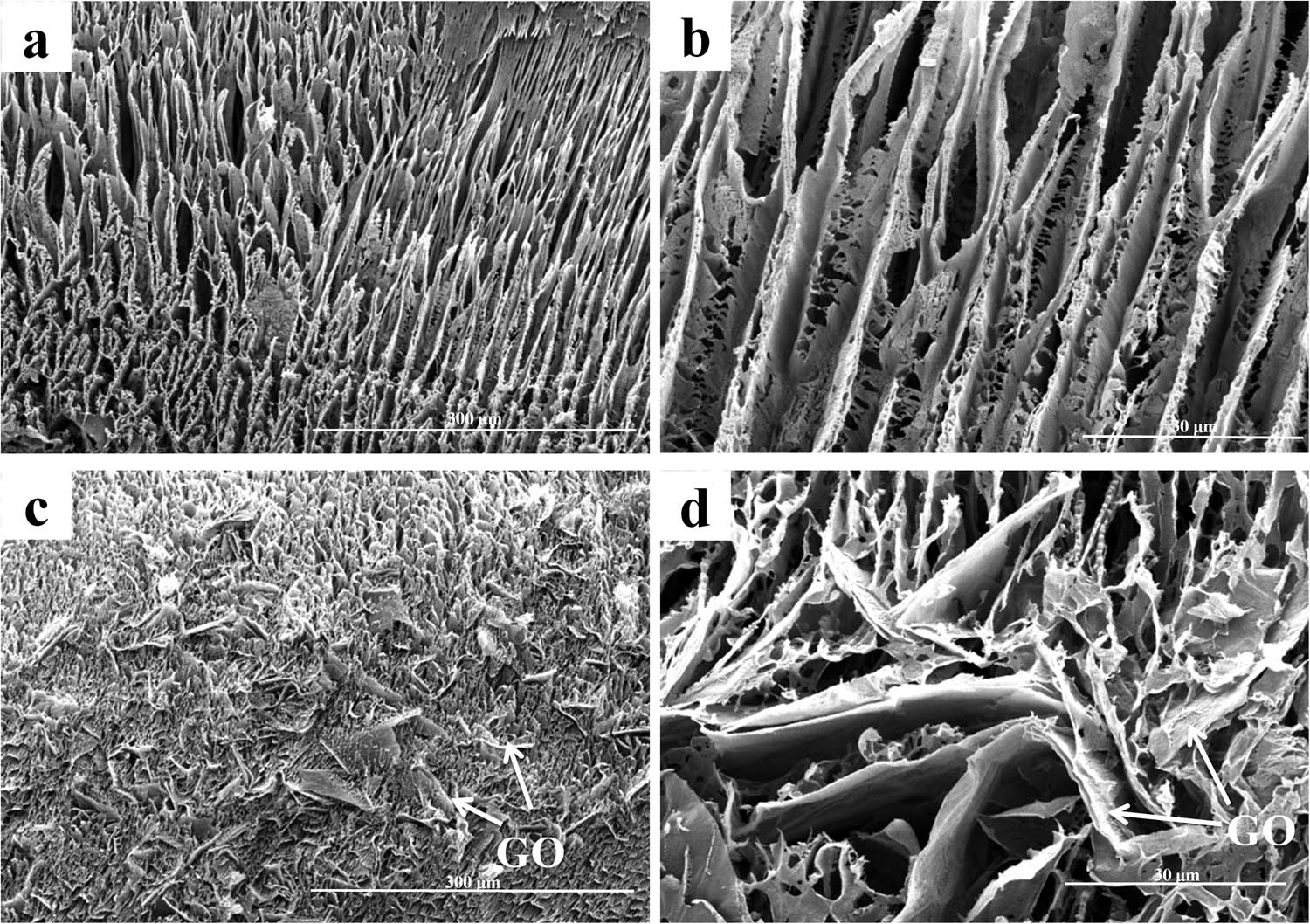

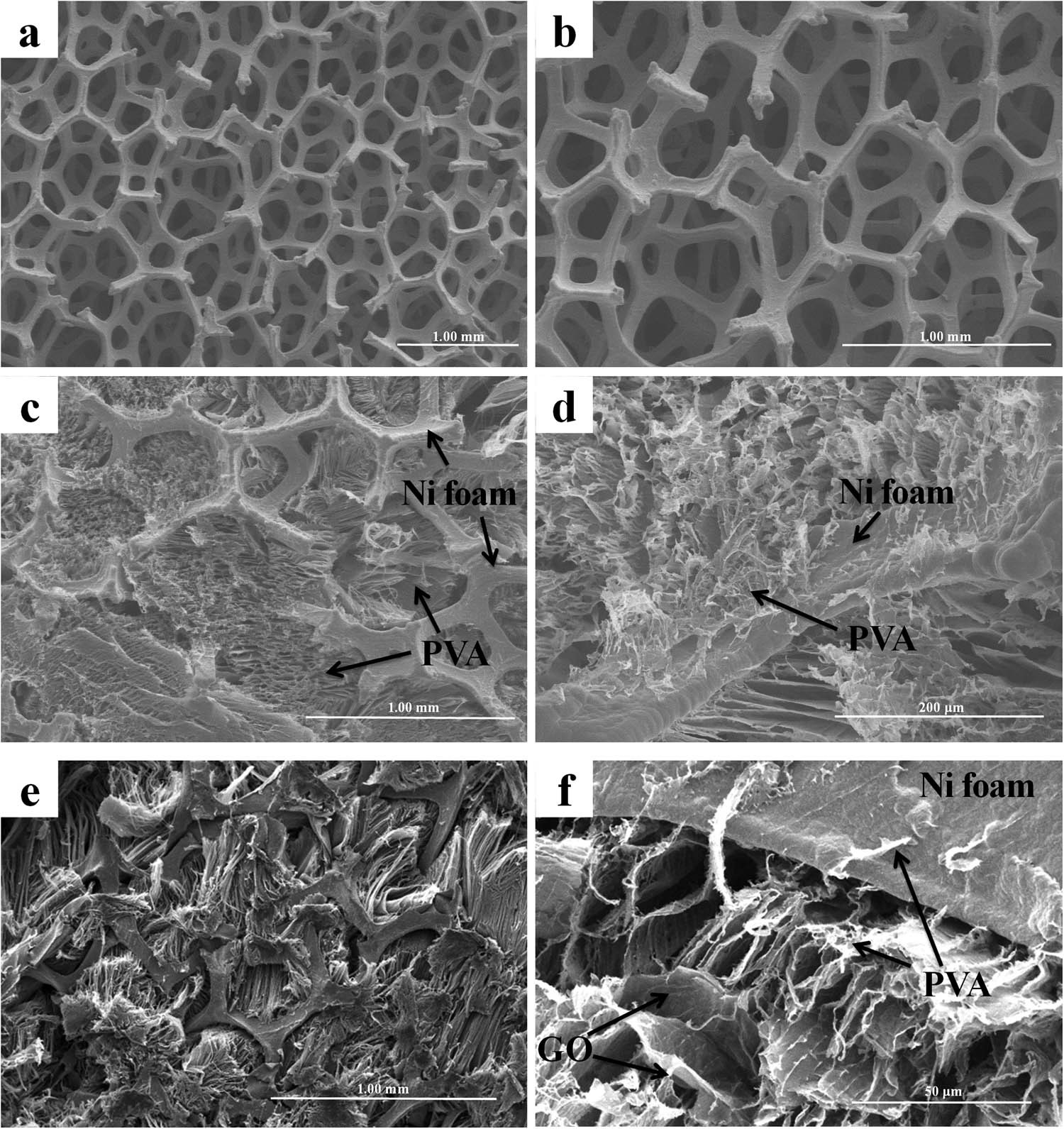

Figure 3(a and b) shows the SEM images of PVA aerogel at different magnification rates. From Figure 3(a), we can see that PVA is interconnected from each other. After freezing and drying, a lot of pore structures are formed from PVA thin-walled honeycomb like structure. The porous structure increases the specific surface area of the aerogels. In addition, the local direction of the pore structure is consistent, which reflects the growth direction of ice crystal during freezing. Figure 3(b) is an enlarged PVA thin wall. More pore structures can be observed in PVA thin wall, which further expands the specific surface area of the aerogels. Figure 3(c and d) shows the SEM images of GO/PVA aerogel (20% mass fraction of GO) at different magnification rates. Figure 3(c) shows that GO is homogeneously embedded in PVA, and the discontinuity of GO causes the aerogels not to have a complete conductive network. Therefore, the conductivity of the aerogels should be further modified. Figure 3(d) is a magnification map of the GO slice. Observed at high magnification, the GO lamella is composed of only 1–2 layers, indicating that GO can be dispersed uniformly without agglomeration in PVA, which greatly enlarges the specific surface area of GO, and is more conducive to electromagnetic wave contact with GO and multiple reflections inside the aerogel.

SEM photographs (a and b) PVA aerogels; (c and d) GO/PVA aerogels.

Figure 4(a and b) shows the SEM photographs of Ni foam with different magnifications. The high conductivity and continuous skeleton structure of Ni foam ensure excellent conductivity of the composite aerogels. In addition, magnetic Ni foam can give good magnetic loss to the composite aerogels, and further reduce the electromagnetic energy [37,38]. A large number of pores between the Ni foam frameworks facilitate the smooth flow of GO/PVA solution into the interior, while the high porosity of the Ni foam greatly reduces the density of the material. Figure 4(c and d) shows the SEM photographs of the Ni/PVA aerogels. Porous structure of PVA fills the pores of Ni foam and improves the compressive properties of the material. PVA adhered well to the nickel skeleton (Figure 4(d)), indicating that the combination of PVA and Ni foam is good, which ensures the stability of the material. Figure 4(e and f) are the SEM photographs of the Ni/GO/PVA aerogels. GO/PVA is evenly and tightly packed in the pores of Ni foam, providing support force for Ni skeleton, thereby enhancing the strength of the material. From Figure 4(f), it can be seen that PVA can be tightly coated on the surface of GO and Ni foam, showing a good combination.

SEM photographs: (a and b) Ni foam; (c and d) Ni/PVA aerogels; (e and f) Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels.

3.2 Mechanical properties of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels

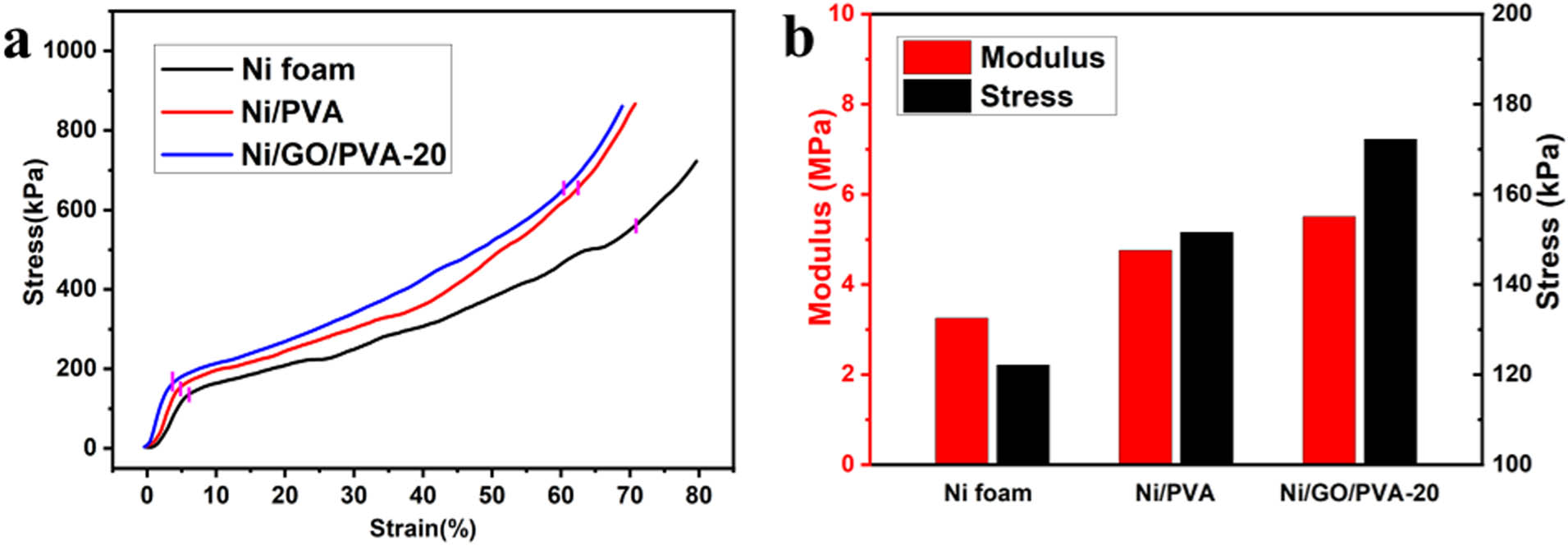

Figure 5(a) shows the compression properties of the Ni foam, Ni/PVA, and Ni/GO/PVA-20. The compressive stress–strain curves of the Ni foam can be divided into three stages: linear deformation, collapse, and densification stage. When the strain is in the range of 0–5%, the stress increases linearly with the strain, and the deformation is mainly elastic deformation, which can be recovered after unloading. When the strain reaches 5%–70%, the slope of the curve decreases rapidly, and the deformation is mainly plastic deformation. As the load increases, the weak area inside the Ni foam begins to collapse and cracks occur, and the deformation produced in this form is unrecoverable. When strain exceeds 70%, the deformation is too large. Most pores in the Ni foam are completely compacted, and the material enters the densification stage. The stress increases sharply with the increase in strain. Ni/PVA and Ni/GO/PVA-20 also have three deformation stages, and compared with Ni foam, the slope of the linear deformation stage is larger, and the stress at the end of linear deformation is greater. In addition, because of the presence of PVA and GO in the pores, Ni/PVA and Ni/GO/PVA-20 begin to densify at a smaller strain. As shown in Figure 5(b), the relationship for the modulus and the stress at the end of the linear deformation stage is: Ni/GO/PVA-20 > Ni/PVA > Ni foam. PVA is filled with Ni foam pores, which provides a certain support force for the compression. The GO of Ni/GO/PVA-20 is distributed in PVA, and the hydrogen bond between GO and PVA ensures higher strength and modulus.

Compression properties of Ni foam, Ni/PVA, and Ni/GO/PVA-20 (a) compression stress–strain curves; (b) modulus and maximum stress.

3.3 Hydrophobicity of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels

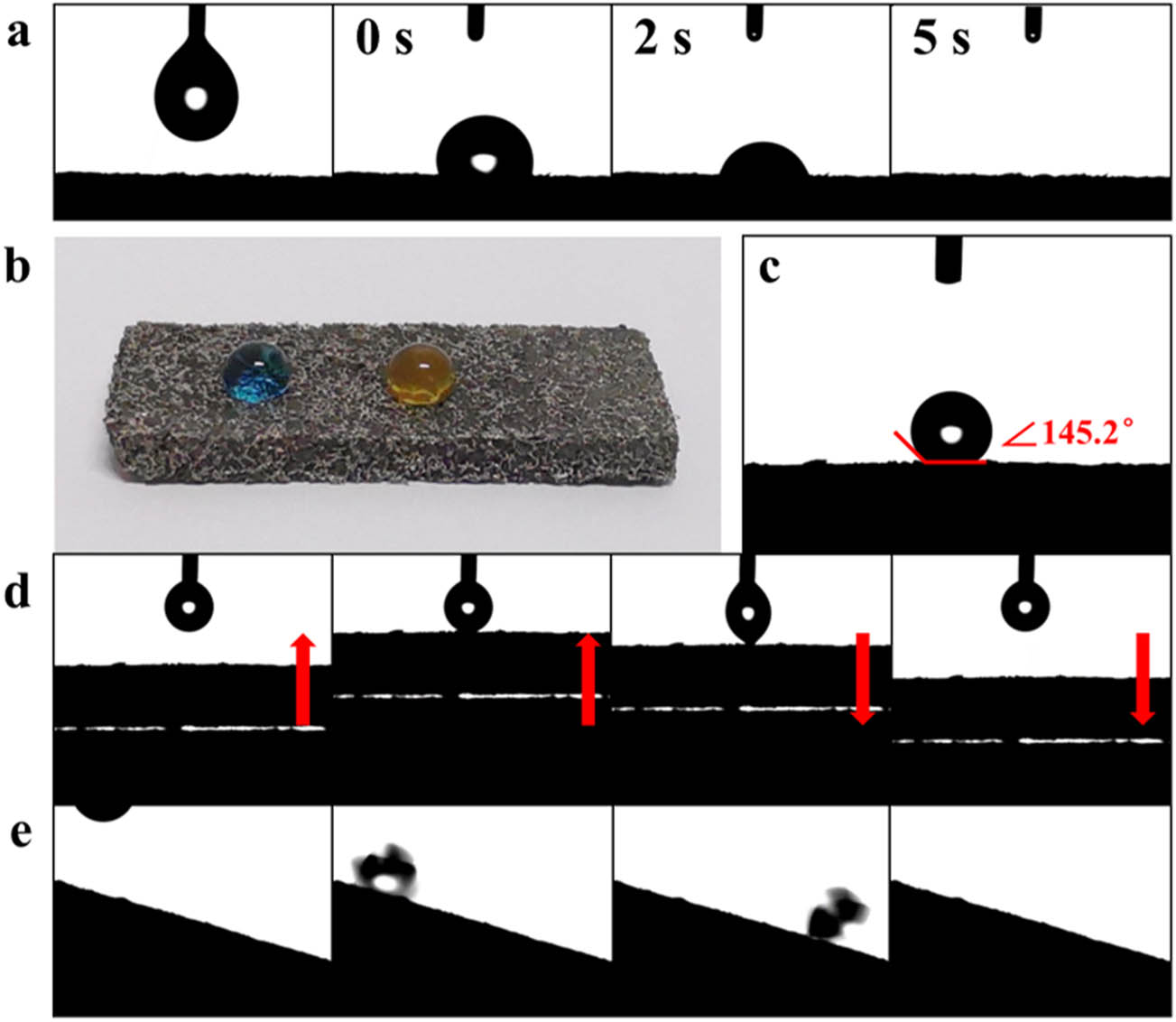

A large number of porous structures exist in Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels, and a large number of hydroxyl groups on PVA make the materials hydrophilic. As shown in Figure 6(a), the droplet drops on the surface of the Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogel without hydrophobic treatment, and the droplet is absorbed by the material after 5 s. Hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels exhibit strong hydrophobicity. Figure 6(b) shows that when droplets of different colors are dropped on the surface of the material, the beads can remain on the surface of the material with a complete spherical shape and are not absorbed by the material. The average contact angle of Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels is 145.2° (Figure 6(c)). Then, the droplet drag experiment is carried out on the material, as shown in Figure 6(d). First, the material is moved upward to contact the droplet, and then slowly moved down the material. It is found that the droplet is dragged and deformed between the needle tube and the material. Due to the excellent hydrophobicity of the material, the droplet is not dragged to the surface of the material, but remained on the needle tube. The rolling experiment of water drops is shown in Figure 6(e) and the material is tilted to 17°. Drops of water from above can roll down smoothly and quickly. The droplet drag experiment and rolling experiment show that the material has excellent hydrophobicity. The hydrophobicity of Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels is attributed to two points. First, the surface energy of FAS-17 coating on the aerogel is low, and the affinity between the material and water is reduced. Second, the micro porous structure of aerogels formed micron roughness on the surface, reducing the liquid-solid contact area, thus increasing the hydrophobicity of the materials. Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels with hydrophobic treatment have special applications for waterproofing and corrosion resistance. Meanwhile, water droplets can roll on the surface of the material, remove the adsorbed dust and pollutants, and achieve self-cleaning function.

Surface wettability of Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogel: (a) before hydrophobicity modification; (b and c) contact angle after hydrophobic modification; (d) droplet drag experiment; (e) rolling angle experiment.

3.4 EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels

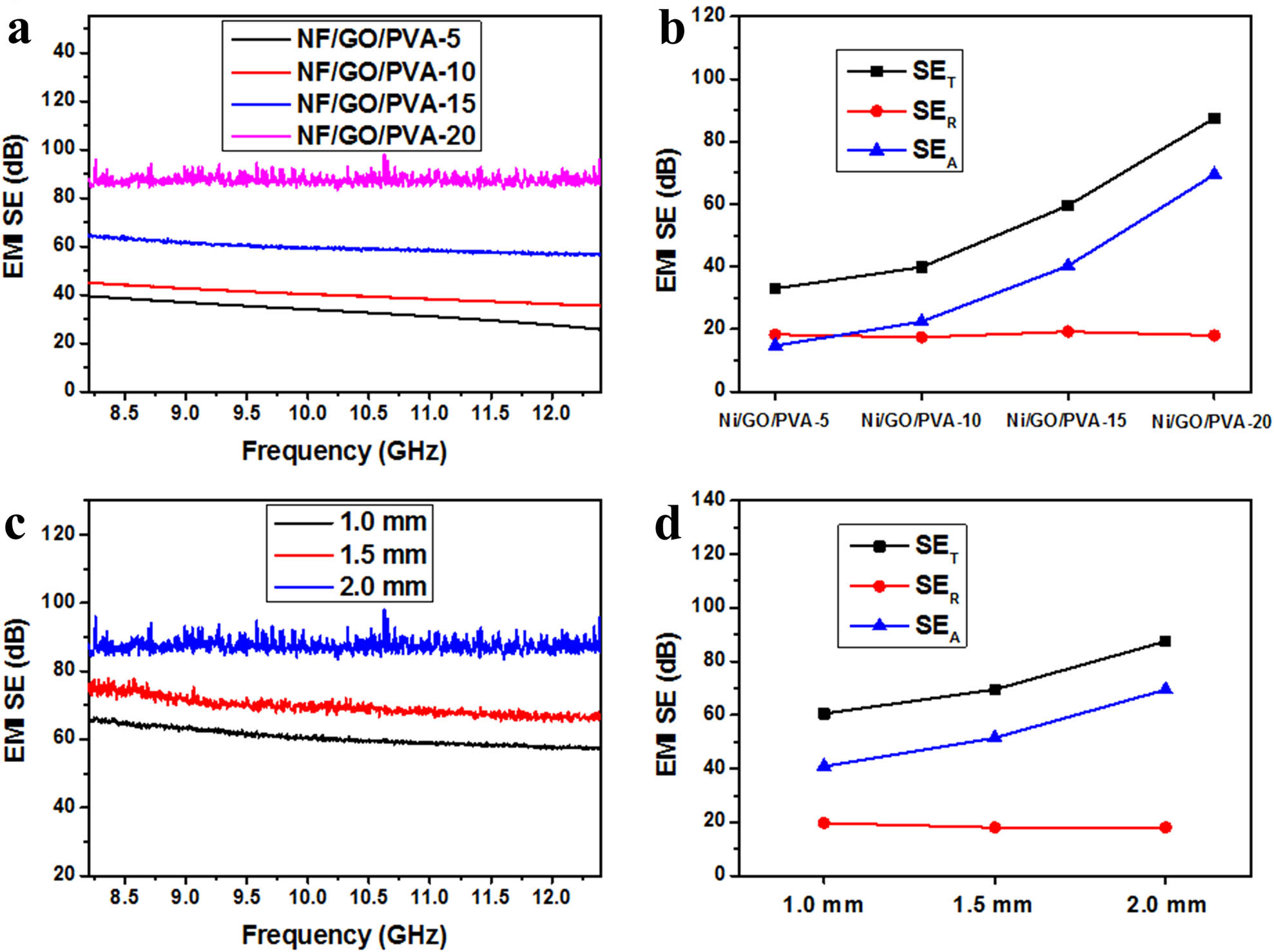

Figure 7(a) shows the EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels with different GO contents. The SET of Ni/GO/PVA-5 decreases with the increase in the frequency, for 8.2 GHz, the SET is 39 dB, while for 12.4 GHz, the SET is 26 dB, and the entire X band can shield 99% of the electromagnetic waves. The EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels can be obviously improved by increasing the GO content, and the EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA-20 is 87 dB, corresponding to an ultrahigh EMI shielding efficiency of ∼99.9999998%. The EMI shielding performance consists of the reflection of electromagnetic wave from the interface between the sample and air and the absorption of electromagnetic wave by the sample. Figure 7(b) shows the average values of SET, SER, SEA of Ni/GO/PVA in X-band. The SER of Ni/GO/PVA-5 is greater than that of SEA, indicating that the EMI shielding of Ni/GO/PVA is mainly reflected at low GO content. With the increase in GO content, the SER of Ni/GO/PVA-10, Ni/GO/PVA-15, and Ni/GO/PVA-20 is less than that of SEA, which shows that the EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels with high GO content is mainly the absorption. With the increase in graphene content, Ni/GO/PVA has no obvious effect on the reflection ability of the electromagnetic wave, but the absorption ability is obviously improved. The reflectivity depends on the impedance matching at the interface between the sample and free space. The impedance match is related to the electromagnetic parameters of the sample. The Ni foam in Ni/GO/PVA forms a complete three-dimensional conductive network. The change in GO has no obvious effect on the conductivity. Therefore, SER is not affected by the change in the GO content. Electromagnetic waves produce reflection in the pores of Ni surface and GO surface. GO distributes unevenly in the pores of Ni foam. Multiple reflections greatly increase the propagation distance of electromagnetic waves. In addition, GO increases a large number of heterogeneous interfaces, and the ability of interface polarization loss increases. The increase in GO content enhances the ability of the electromagnetic wave attenuation, thus improving the EMI shielding ability of Ni/GO/PVA.

EMI shielding properties of Ni/GO/PVA aerogel: (a and b) effect of GO content; (c and d) effect of thickness for Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels.

Figure 7(c) shows the EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels with different thicknesses. The thickness of the aerogels increases and the EMI shielding performance is enhanced. From 1.0 mm to 2.0 mm, the EMI shielding performance is improved from 60 to 87 dB. Figure 7(d) shows the average values of SET, SER, and SEA in X-band for different thicknesses of Ni/GO/PVA-20. The reflection of electromagnetic waves of the samples varies little with thickness. The enhancement of EMI shielding performance of thick samples is due to the enhanced absorption of electromagnetic waves. With the increase in thickness, the propagation time of electromagnetic waves in the samples is longer, the number of GO sheets is more, and the reflection time of electromagnetic waves is increased. The propagation distance of the electromagnetic waves in the sample is larger, the electromagnetic waves are more likely to be attenuated, and the SEA increases. In addition, the thickness of the sample increased, the thickness of Ni foam increased, the electromagnetic wave propagation distance increased, and the magnetic loss capacity increased. Table 1 compares the EMI shielding properties of related materials in recent years. Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogels exhibit excellent EMI shielding properties at small thickness.

Comparison of EMI shielding properties of related materials in literature

| Materials | Thickness (mm) | EMI SE (dB) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon nanotube/graphene/polyimide foam | 2.0 | 28 | [35] |

| Cu nanowires/graphene aerogel | 3.0 | 47 | [34] |

| rGO aerogel | 5.0 | 40 | [40] |

| Graphene aerogel | 2.5 | 43 | [32] |

| Ti3C2T x /rGO aerogel | 2.0 | 56 | [29] |

| Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogel | 2.0 | 87 | This work |

| Ni/GO/PVA-20 aerogel | 1.0 | 60 | This work |

3.5 Analysis of EMI shielding mechanism

The EMI shielding mechanism of Ni/GO/PVA aerogels is divided into two parts: reflection and absorption of electromagnetic waves. As shown in Figure 8, when the electromagnetic waves reach the surface of the sample, the high conductivity of the three-dimensional conductive network of Ni foam makes the interface between air and sample impedance mismatch, and a part of the electromagnetic waves are reflected [40]. There are a lot of pores in the Ni foam. GO flakes and PVA distribute irregularly in the pores, on the one hand, preventing the electromagnetic wave spilling from the pores. On the other hand, the structure inside the sample causes the electromagnetic waves to reflect and scatter on the surface of the Ni hole wall and GO surface, increasing the electromagnetic wave propagation path, and the electromagnetic waves have a greater probability to be attenuated [41,42]. The absorption mechanism of the electromagnetic wave is divided into dielectric loss and magnetic loss. First, the high conductivity of the continuous conductive network of Ni foam conduces to fast electron transfer, and aerogel has strong conductance loss. Second, there are GO and PVA in the pores of the Ni foam, which make the samples have a large number of heterogeneous interfaces (Ni-GO, Ni-PVA, and GO-PVA). Under the action of electromagnetic waves, free charges gather at the interface, causing strong interfacial polarization loss. Finally, strong magnetic nickel can cause strong magnetic loss, and further dissipate electromagnetic energy through natural resonance, exchange resonance, and eddy current [37]. In general, the synergistic effect of the dielectric loss and magnetic loss and the porous structure of the aerogels make the material possess excellent EMI shielding performance.

EMI shielding mechanism of Ni/GO/PVA aerogel.

4 Conclusion

Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels with disordered GO, porous structure, and lightweight were successfully prepared by freeze-drying process. The results show that the compression process can be divided into linear deformation, collapse, and densification stage. The hydrogen bonding between GO and PVA and the binding force between PVA and Ni foam increase the modulus of the Ni/GO/PVA linear deformation stage. Ni/GO/PVA aerogels have waterproof properties, while water droplets can roll on the surface of the material, remove the adsorbed dust and pollutants, and achieve self-cleaning function. Moreover, with the increase in the GO content, the overall EMI shielding performance is improved. Ni/GO/PVA-20 has excellent EMI shielding performance and it can reach 87 dB at the thickness of 2.0 mm. The EMI shielding performance decreases with the decrease in thickness. The EMI shielding performance of Ni/GO/PVA-20 with thickness of 1.0 mm and 1.5 mm is 60 dB and 70 dB, respectively. The porous structure of the disordered GO and aerogels increase the propagation distance of electromagnetic waves. The dielectric loss, magnetic loss, and multiple reflection and scattering are the main mechanisms of electromagnetic energy attenuation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial supports from Excellent Young Scientist Foundation of NSFC (No. 11522216); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11872087); Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 2182033); Aeronautical Science Foundation of China (No. 2016ZF51054); the 111 Project (No. B14009); Project of the Science and Technology Commission of Military Commission (No. 17-163-12-ZT-004-002-01); Foundation of Shock and Vibration of Engineering Materials and Structures Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (No. 18kfgk01); Foundation of State Key Laboratory for Strength and Vibration of Mechanical Structures (No. SV2019-KF-32). Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Technology of Beijing Institute of Technology (No. KFJJ21-06M).

-

Funding information: Excellent Young Scientist Foundation of NSFC (No. 11522216); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11872087); Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 2182033); Aeronautical Science Foundation of China (No. 2016ZF51054); the 111 Project (No. B14009); Project of the Science and Technology Commission of Military Commission (No. 17-163-12-ZT-004-002-01); Foundation of Shock and Vibration of Engineering Materials and Structures Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (No. 18kfgk01); Foundation of State Key Laboratory for Strength and Vibration of Mechanical Structures (No. SV2019-KF-32). Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Technology of Beijing Institute of Technology (No. KFJJ21-06M).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Xie J, Jiang H, Li J, Huang F, Zaman A, Chen X, et al. Improved impedance matching by multi-componential metal-hybridized rGO toward high performance of microwave absorption. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):1–9.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0001Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Bhat A, Budholiya S, Raj SA, Sultan MTH, Hui D, Shah AUM, et al. Review on nanocomposites based on aerospace applications. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10:237–53.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0018Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Du S, Chen H, Hong R. Preparation and electromagnetic properties characterization of reduced graphene oxide/strontium hexaferrite nanocomposites. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):105–14.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0010Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Shahzad F, Alhabeb M, Hatter CB, Anasori B, Hong SM, Koo CM, et al. Electromagnetic interference shielding with 2D transition metal carbides (MXenes). Science. 2016;353(6304):1137–40.10.1126/science.aag2421Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Zhou Y, Wang SJ, Li DS, Jiang L. Lightweight and recoverable ANF/rGO/PI composite aerogels for broad and high-performance microwave absorption. Compos B Eng. 2021;213:108701.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.108701Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Cao WT, Chen FF, Zhu YJ, Zhang YG, Jiang YY, Ma MG, et al. Binary strengthening and toughening of MXene/cellulose nanofiber composite paper with nacre-inspired structure and superior electromagnetic interference shielding properties. ACS Nano. 2018;12(5):4583–93.10.1021/acsnano.8b00997Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wang SJ, Li DS, Zhou Y, Jiang L. Hierarchical Ti3C2Tx MXene/Ni chain/ZnO array hybrid nanostructures on cotton fabric for durable self-cleaning and enhanced microwave absorption. ACS Nano. 2020;14(7):8634–45.10.1021/acsnano.0c03013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Sun Y, Peng Y, Zhou T, Liu H, Gao P. Study of the mechanical-electrical-magnetic properties and the microstructure of three-layered cement-based absorbing boards. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):160–9.10.1515/rams-2020-0014Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Iqbal A, Shahzad F, Hantanasirisakul K, Kim MK, Kwon J, Hong J, et al. Anomalous absorption of electromagnetic waves by 2D transition metal carbonitride Ti3CNTx (MXene). Science. 2020;369(6502):446–50.10.1126/science.aba7977Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Yao B, Hong W, Chen T, Han Z, Xu X, Hu R, et al. Highly stretchable polymer composite with strain-enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. Adv Mater. 2020;32(14):1907499.10.1002/adma.201907499Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Wang SJ, Li DS, Jiang L. Synergistic effects between MXenes and Ni chains in flexible and ultrathin electromagnetic interference shielding films. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2019;6(19):1900961.10.1002/admi.201900961Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Liu J, Zhang HB, Sun R, Liu Y, Liu Z, Zhou A, et al. Hydrophobic, flexible, and lightweight MXene foams for high-performance electromagnetic-interference shielding. Adv Mater. 2017;29(38):1702367.10.1002/adma.201702367Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ahmad SI, Hamoudi H, Abdala A, Ghouri ZK, Youssef KM. Graphene-reinforced bulk metal matrix composites: Synthesis, microstructure, and properties. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):67–114.10.1515/rams-2020-0007Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Barathi Dassan EG, Rahman AAA, Abidin MSZ, Akil HM. Carbon nanotube-reinforced polymer composite for electromagnetic interference application: A review. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):768–88.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0064Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Zuo HM, Li DS, Hui D, Lei J. The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene)diamines and GO nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):587–99.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0052Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Liu SD, Li DS, Yang Y, Jiang L. Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):218–26.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0020Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Chen XX, Li Y, Wang Y, Song DQ, Zhou ZW, Hui D. An approach to effectively improve the interfacial bonding of nano-perfused composites by in situ growth of CNTs. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):282–91.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0025Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Guan QF, Han ZM, Yang KP, Yang HB, Ling ZC, Yin CH, et al. Sustainable double-network structural materials for electromagnetic shielding. Nano Lett. 2021;21(6):2532–7.10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c05081Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Kośla K, Olejnik M, Olszewska K. Preparation and properties of composite materials containing graphene structures and their applicability in personal protective equipment: a review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):215–42.10.1515/rams-2020-0025Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Visconti P, Primiceri P, de Fazio R, Strafella L, Ficarella A, Carlucci AP. Light-induced ignition of carbon nanotubes and energetic nano-materials: A review on methods and advanced technical solutions for nanoparticles-enriched fuels combustion. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):26–46.10.1515/rams-2020-0010Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Wang J, Xu Y, Wu X, Zhang P, Hu S. Advances of graphene- and graphene oxide-modified cementitious materials. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):465–77.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0041Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Li DS, Han WF, Jiang L. On the tensile properties and failure mechanisms of 3D six-directional braided composites at elevated temperatures. Compos Commun. 2021;28:100884.10.1016/j.coco.2021.100884Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Li DS, Yang Y, Jiang L. Experimental study on the fabrication, high-temperature properties and failure analysis of 3D seven-directional braided composites under compression. Compos Struct. 2021;268:113934.10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.113934Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Wei Q, Pei S, Qian X, Liu H, Liu Z, Zhang W, et al. Superhigh electromagnetic interference shielding of ultrathin aligned pristine graphene nanosheets film. Adv Mater. 2020;32(14):1907411.10.1002/adma.201907411Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jia H, Yang X, Kong QQ, Xie LJ, Guo QG, Song G, et al. Free-standing, anti-corrosion, super flexible graphene oxide/silver nanowire thin films for ultra-wideband electromagnetic interference shielding. J Mater Chem A. 2021;9(2):1180–91.10.1039/D0TA09246KSuche in Google Scholar

[26] Rani P, Ahamed MB, Deshmukh K. Structural, dielectric and EMI shielding properties of polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan blend nanocomposites integrated with graphite oxide and nickel oxide nanofillers. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2020;32(1):764–79.10.1007/s10854-020-04855-wSuche in Google Scholar

[27] Fan Z, Wang D, Yuan Y, Wang Y, Cheng Z, Liu Y, et al. A lightweight and conductive MXene/graphene hybrid foam for superior electromagnetic interference shielding. Chem Eng J. 2020;381:122696.10.1016/j.cej.2019.122696Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Zhao S, Zhang HB, Luo JQ, Wang QW, Xu B, Hong S, et al. Highly electrically conductive three-dimensional Ti3C2Tx MXene/reduced graphene oxide hybrid aerogels with excellent electromagnetic interference shielding performances. ACS Nano. 2018;12(11):11193–202.10.1021/acsnano.8b05739Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lin S, Liu J, Wang Q, Zu D, Wang H, Wu F, et al. Highly robust, flexible, and large-scale 3D-metallized sponge for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv Mater Technol. 2019;5(2):1900761.10.1002/admt.201900761Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Weng C, Wang G, Dai Z, Pei Y, Liu L, Zhang Z. Buckled AgNW/MXene hybrid hierarchical sponges for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Nanoscale. 2019;11(47):22804–12.10.1039/C9NR07988BSuche in Google Scholar

[31] Li CB, Li YJ, Zhao Q, Luo Y, Yang GY, Hu Y, et al. Electromagnetic interference shielding of graphene aerogel with layered microstructure fabricated via mechanical compression. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(27):30686–94.10.1021/acsami.0c05688Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yu Z, Dai T, Yuan S, Zou H, Liu P. Electromagnetic interference shielding performance of anisotropic polyimide/graphene composite aerogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(27):30990–1001.10.1021/acsami.0c07122Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Yang X, Fan S, Li Y, Guo Y, Li Y, Ruan K, et al. Synchronously improved electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal conductivity for epoxy nanocomposites by constructing 3D copper nanowires/thermally annealed graphene aerogel framework. Compos Appl Sci Manuf. 2020;128:105670.10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.105670Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Wang YY, Sun WJ, Yan DX, Dai K, Li ZM. Ultralight carbon nanotube/graphene/polyimide foam with heterogeneous interfaces for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding and electromagnetic wave absorption. Carbon. 2021;176:118–25.10.1016/j.carbon.2020.12.028Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Zhao B, Park CB. Tunable electromagnetic shielding properties of conductive poly(vinylidene fluoride)/Ni chain composite films with negative permittivity. J Mater Chem C. 2017;5(28):6954–61.10.1039/C7TC01865GSuche in Google Scholar

[36] Shen B, Li Y, Yi D, Zhai W, Wei X, Zheng W. Strong flexible polymer/graphene composite films with 3D saw-tooth folding for enhanced and tunable electromagnetic shielding. Carbon. 2017;113:55–62.10.1016/j.carbon.2016.11.034Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Liu J, Cao MS, Luo Q, Shi HL, Wang WZ, Yuan J. Electromagnetic property and tunable microwave absorption of 3D nets from nickel chains at elevated temperature. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(34):22615–22.10.1021/acsami.6b05480Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Xu W, Wang GS, Luo Q, Yin PG. Designed fabrication of reduced graphene oxides/Ni hybrids for effective electromagnetic absorption and shielding. Carbon. 2018;139:759–67.10.1016/j.carbon.2018.07.044Suche in Google Scholar

[39] González M, Baselga J, Pozuelo J. Modulating the electromagnetic shielding mechanisms by thermal treatment of high porosity graphene aerogels. Carbon. 2019;147:27–34.10.1016/j.carbon.2019.02.068Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Zhou B, Li Z, Li Y, Liu X, Ma J, Feng Y, et al. Flexible hydrophobic 2D Ti3C2Tx-based transparent conductive film with multifunctional self-cleaning, electromagnetic interference shielding and joule heating capacities. Compos Sci Technol. 2021;201:108531.10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108531Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Wu Y, Wang Z, Liu X, Shen X, Zheng Q, Xue Q, et al. Ultralight graphene foam/conductive polymer composites for exceptional electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(10):9059–69.10.1021/acsami.7b01017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Zeng Z, Jin H, Chen M, Li W, Zhou L, Zhang Z. Lightweight and anisotropic porous MWCNT/WPU composites for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26(2):303–10.10.1002/adfm.201503579Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Dian-sen Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications