Abstract

During the orthodontic process, increased microbial colonization and dental plaque formation on the orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries are major complications, causing oral infectious diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal diseases. To reduce plaque accumulation, antimicrobial materials are increasingly being investigated and applied to orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries by various methods. Through the development of nanotechnology, nanoparticles (NPs) have been reported to exhibit excellent antibacterial properties and have been applied in orthodontic materials to decrease dental plaque accumulation. In this review, we present the current development, antibacterial mechanisms, biocompatibility, and application of antibacterial NPs in orthodontic materials.

1 Introduction

Orthodontic materials, including fixed and removable orthodontic appliances and orthodontic auxiliaries, are essential components in orthodontic treatments. However, the potential adverse effects associated with these appliances and auxiliaries remain unresolved. Increased microbial biofilm accumulation on orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries and subsequential dental caries and periodontitis are common complications during orthodontic treatment [1,2]. Various attempts have been made to inhibit biofilm accumulation on orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries [3], and the addition of antimicrobial agents to these appliances is one of the most effective strategies [4,5]. Some particles have been reported to exhibit excellent antibacterial properties against both gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria when transformed into nanometer size [6,7,8,9,10], and these nanosized antibacterial agents are preferred to be added to dental materials due to the greater surface-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles (NPs), which have intimate interactions with microbial membranes and provide a considerably larger surface area for antibacterial activity [11,12,13]. NPs can be used in dental materials through two mechanisms, including mixing NPs with dental materials or preparing NP coatings on the surface to reduce microbial adhesion and prevent caries [14,15]. In orthodontic treatment, NPs have been proposed for a variety of purposes, such as inhibiting bacteria [15], reducing friction [16], and increasing bond strength [17]. The purpose of this article is to review the antibacterial mechanism, biocompatibility, and application of NPs in orthodontic materials and put forward the prospect of the possible research direction of the combination of antibacterial NPs and orthodontic materials in the future.

2 Antibacterial mechanism of NPs applied in orthodontic materials

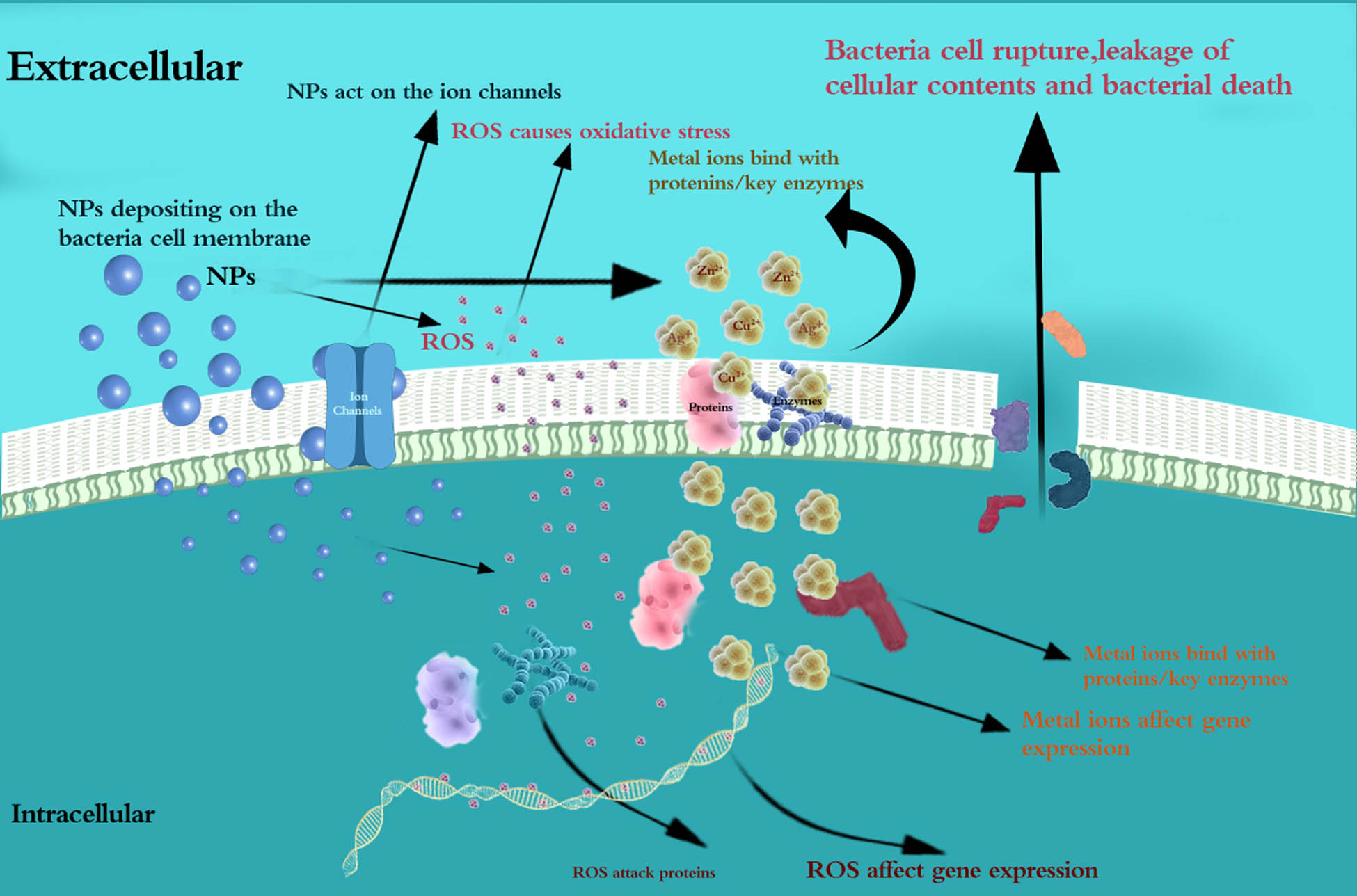

When the particles applied for orthodontic material modification are reduced to nanometer size, new physicochemical and mechanical properties can be obtained, and some NPs can improve the antibacterial ability of orthodontic materials in different ways [18]. NPs can exhibit antibacterial function when in contact with bacterial cells through electrostatic attraction [19], van der Waals forces [20], receptor–ligand interactions [21], and hydrophobic interactions [22]. At present, the antibacterial mechanism of NPs is not clearly understood, and many details of the dynamic process of their interaction with bacterial cells are not clearly known, but with the help of numerous analytical tools and research methods, some common understandings have been accumulated (Figure 1).

Antibacterial mechanism of NPs applied in orthodontic materials.

2.1 Inhibition of biofilms

Biofilms are complex communities that form when a group of microorganisms self-secrete a polysaccharide matrix that retains nutrients for the constituent cells and protects them from both the immune response and antimicrobial agents [23]. Reducing the adhesion of biofilms is an effective way to prevent oral infections. Some evidence shows that NPs can affect bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [24,25], and the mechanisms that have been concluded are as follows:

Reduction of the formation of biofilms: The mechanism by which NPs inhibit the formation of bacterial biofilms is related to the regulation of bacterial metabolism, which is an important activity of biofilms. NPs were reported to adhere to and diffuse into biofilms, act on the ion channels in bacterial biofilms that are helpful for the long-distance electrical signal conduction of bacteria in a biofilm, disrupt the membrane potential, and lead to enhanced lipid peroxidation and DNA binding, thus regulating the metabolic activity of bacteria and decreasing the ability of bacteria to form biofilms [26,27,28].

Reduction of the adhesion of biofilms: NPs can modify the surface of the material and make it not conducive to the adhesion of the biofilm. Jasso-Ruiz demonstrated that the orthodontic brackets coated with nanosilver present smoother surfaces, which reduced the adhesion of both Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus to the orthodontic brackets, demonstrating the antibacterial properties of silver NPs (Ag NPs) [15]. In the study of Lee, an anti-adherent effect against Candida albicans and Streptococcus oralis was observed with the incorporation of mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs) into poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [29].

2.2 Extracellular antibacterial effects

Before penetrating bacteria cells, NPs exhibit antibacterial effects through the disruption of the bacterial cell membrane. The main disruption methods are as follows:

Depositing on the surface and interaction with the components of the cell membrane: Visualization methods such as electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy have shown that the appearance of the bacterial cell membrane could be changed when NPs deposit on the surface of bacteria. This deposition causes large holes that cannot be repaired on the surface of the bacterial cell [30], which is followed by the NP’s penetration into the bacterial cell [31]. The destruction of cell morphology and integrity was observed after the deposition of ZnO NPs [32], and depressions in the cell membrane of Escherichia coli and a large amount of Ag NPs embedded in the cell membrane of bacteria were found after the deposition of Ag NPs on the bacterial cell membrane [33,34,35,36]. In addition, some NPs were reported to exhibit the antibacterial effects through the direct interaction with bacterial cell membrane components, which is followed by cell death due to the increasing membrane permeability and the leakage of cellular contents [37].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidative stress: NPs reduce oxygen molecules to produce different types of ROS, including superoxide radicals (O2 −), hydroxyl radicals (˙OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet oxygen (O2), which have strong positive redox potential and exhibit different levels of dynamics and activity [38]. The excess of ROS disrupts the balance between the production and clearance of ROS in bacterial cells and causes oxidative stress, which damages the individual components of bacterial cells [24,39]. Oxidative stress has been proven to be a key factor in changing cell membrane permeability, which can lead to the destruction of the bacterial cell membrane, causing the leakage of cellular contents and resulting in bacterial death [40]. Danilczuk reported Ag-generated free radicals through the electron spin resonance (ESR) study of Ag NPs [41], and Kim confirmed the production of free radicals by ESR analysis of Ag NPs and concluded that the antibacterial mechanism of Ag NPs is related to the formation of free radicals and subsequent free radical-induced membrane damage [42]. As reported, titanium dioxide NPs can produce hydroxyl radicals with a strong bactericidal effect [43].

Effects of dissolved metal ions: The positively charged metal ions of NPs are released to bind with the negatively charged functional groups of the bacterial cell membrane, resulting in the confusion and dispersion of the originally ordered and closely spaced cell membranes, destroying their inherent function and leading to bacterial death [44,45]. Sondi and Salopek-Sondi demonstrated that sulfur-containing proteins/key enzymes in the membrane or inside the cells are likely to be the preferred binding sites of Ag NPs, and the accumulation of Ag NPs on the bacterial membrane can cause permeability and lead to cell death [33].

2.3 Intracellular antibacterial effects

NPs penetrate in bacterial cells and interact with important functional molecules, resulting in the inhibition of the growth of bacterial cells in the following ways:

ROS-induced oxidative stress: NPs introduce ROS and metal ions into bacteria by diffusion, and ROS can help to improve the gene expression level of oxidized proteins, which is an important mechanism of bacterial apoptosis [46]. ROS can attack proteins and inhibit the activity of certain periplasmic enzymes essential for maintaining the normal morphology and physiological processes of bacterial cells [44,47].

Effects of dissolved ions: Metal ions absorbed into bacterial cells directly interact with the functional groups of proteins and nucleic acids, including mercapto (–SH), amino (–NH), and carboxyl (–COOH) groups, damaging enzyme activity, changing the cell structure, affecting normal physiological processes, and ultimately inhibiting microorganisms [38,42,48,49]. Morones et al. [50] and Sondi and Salopek-Sondi [33] studied the bactericidal effect of Ag NPs and found that these NPs were able to penetrate inside the bacteria and cause further damage, possibly by interacting with sulfur- and phosphorus-containing compounds, such as DNA. Feng et al. [51] found that DNA lost its replication ability and that the protein became inactivated and Yamanaka et al. [52] found that the expression of ribosomal subunit proteins and other cellular proteins and enzymes necessary for ATP production was inactivated after Ag+ treatment.

3 NPs applied for antibacterial purposes in orthodontic materials

NPs applied for antibacterial purposes in orthodontics are mainly combined with dental materials or coated over the surfaces of orthodontic materials. According to the sources and modes of action, they can be roughly divided into three types: inorganic NPs, organic NPs, and natural macromolecule compound NPs.

3.1 Inorganic NPs

Inorganic NPs include metals, metal oxides, their doped form, and some novel surface-modified NPs.

3.1.1 Nanoparticulate metals

Metals have been used as antimicrobial agents for centuries, and they can obtain stronger antibacterial activity when the size is reduced to the nanometer scale.

3.1.1.1 Ag

According to recent studies, nanosilver is the most commonly used antibacterial nanometal in orthodontic materials. Whether used alone or in combination with other reagents, Ag NPs have shown excellent antibacterial properties. Ag NPs formed in situ show substantial antibacterial activity through oxidative stress and the release of silver ions [53,54]. Silver ions are very active and can quickly bind to negatively charged proteins, RNA, DNA, and so on, which is the most important part of their antibacterial mechanism [55]. It has been observed that Ag NPs can attach to the bacterial cell membrane and penetrate the bacterial internal respiratory chain, leading to bacterial cell leakage and eventual cell death [56]. As expected, Ag NPs have been studied in a variety of orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries and have shown extraordinary antibacterial effects [15,57,58,59,60].

3.1.1.2 Au

Gold NPs (Au NPs) exert favorable biocompatibility and can be easily modified due to their controllable size and chemical stability [61]. 4,6-Diamino-2-pyrimidinethiol-conjugated Au NPs (AuDAPT) were previously reported to effectively kill multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria and induce drug resistance to a much smaller extent than conventional antibiotics [62]. AuDAPT-coated aligners have been proven to have antibacterial effects on the suspension of Porphyromonas gingivalis, slow biofilm formation, and favorable biocompatibility [63].

3.1.1.3 Cu

As an NP with an antibacterial effect, copper is significantly more affordable than silver or gold, so it is economically attractive. Antibacterial effects on Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and S. mutans were observed in the study of Argueta-Figueroa et al. when Cu NPs were added to orthodontic adhesives [64].

3.1.2 Nanoparticulate metal oxides

Highly ionic nanoparticulate metal oxides are very valuable as antimicrobial agents, since they can be prepared with extremely high surface areas and special crystal morphologies with a large number of edges and corners, as well as other potentially reactive sites [65].

3.1.2.1 CuO

Khan et al. showed that CuO NPs had a strong inhibitory effect on the growth and colonization of microbial plaque [66]. The study of Toodehzaeim et al. showed that orthodontic adhesive containing CuO NPs had antibacterial properties and could inhibit the growth of S. mutans [67].

3.1.2.2 ZnO

Previous studies have proven that nanozinc oxide has a strong bactericidal effect on gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as spores resistant to high temperature and high pressure. The antibacterial mechanism of ZnO includes the reduction of bacterial viability, the generation of hydrogen peroxide, the accumulation of ZnO NPs on the surface of bacteria, the production of ROS on the surface of particles, the release of zinc ions, the dysfunction of bacterial cell membranes, and the internalization of ZnO NPs [68]. ZnO NPs were used to prepare a unique coating on the surface of NiTi archwire, and the coating had a superior antibacterial effect on both gram-negative bacteria and gram-positive bacteria and had superior frictional performance [69]. In addition, cationic curcumin-doped zinc oxide NPs (cCur/ZnO NPs) have been added to orthodontic adhesives to control a variety of cariogenic biofilms and reduce their metabolic activity [70].

3.1.2.3 TiO2

Among all kinds of nanomaterials, titanium dioxide NPs have excellent properties, such as high chemical stability, good biocompatibility, and nontoxicity. Previous experiments have shown that titanium dioxide can generate superoxide anion radicals and hydroxyl radicals with strong chemical activity and bactericidal activity due to its electronic structure [43,71]. These ROS are strong oxidants that react with biomolecules, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, resulting in oxidative damage to cell membranes and bacterial death [72,73,74]. TiO2 NPs were reported to be added to glass ionomer cement in orthodontic treatment and the results showed that TiO2 NPs caused rapid intracellular bacterial damage and could significantly improve the antibacterial effect [43]. In addition, fixed retainer composites filled with TiO2 NPs showed a statistically significant increase in antibacterial activity [75].

Although the nanometals and nanometal oxides listed above exhibit effective antibacterial properties, their biocompatibility and safety are still not confirmed and still need to be determined by further intraoral studies. Silver and copper ions have been reported to be cytotoxic in in vitro studies for several types of cells, and the toxicity mechanism is not yet clear, which may be mostly attributed to the size and concentration of NPs [76,77]. Au NPs exert favorable biocompatibility, while the cost is a vital problem when Au NPs are applied in orthodontic materials for bacterial inhibition. ZnO and TiO2 NPs show biocompatibility and minimum cytotoxicity [43,70], making them possible types of antibacterial NPs for application in orthodontic materials.

3.1.3 Fluoride NPs

During an acidic challenge, the presence of fluoride initiates the formation of fluorapatite to replace the dissolved hydroxyapatite, which is conducive to remineralization [78]. Fluorides with significant antibacterial activity have been found to affect bacterial metabolism mainly through intracellular antibacterial effects. They can act either directly or by forming metal–fluoride complexes that have significant effects on a variety of enzymes and regulatory phosphatases [79]. Released F-ions can act as glycolytic enzyme inhibitors and transmembrane proton carriers to inhibit oral microorganisms by inducing cytoplasmic acidification and have long-distance antibacterial activity [80,81]. Fluoride NPs can exhibit antibacterial effect and play a role in demineralization and remineralization processes, while many oral bacteria are insensitive to the direct action of fluoride unless they are prepared as metal–fluoride complexes. Asiry et al. evaluated the antibacterial effect of a conventional orthodontic composite resin blended with yttrium fluoride (YF3) NPs and a remarkable antibacterial effect was proven [82]. In addition, Yi developed a resin-modified glass ionomer containing NPs of calcium fluoride (nCaF2) with antibacterial and remineralization capabilities to combat enamel white spot lesions [83].

3.1.4 Mesoporous bioactive glass NPs (MBNs)

MBNs are bioactive substances consisting of SiO2, CaO, Na2O, and P2O5. MBNs have been widely used as biological materials because of their high chemical stability, mechanical stability, and effective bioactive functions [84]. They can remineralize enamel and dentin with high bioactivity, lower cytotoxicity to dental pulp stem cells, and antibacterial activity against intraoral bacteria [85,86]. MBNs exhibit the antibacterial effects mainly through extracellular antibacterial effects. It has been hypothesized that the antibacterial activity of bioactive glass is attributed to the increase in local pH following the exchange of sodium ions with protons in body fluids, and the alteration to a highly alkaline environment stresses bacteria and induces them to modify their form and ultrastructure, thus changing numerous genes and protein phenotype patterns [87]. Another factor that contributes to antibacterial activity is the release of ions, such as silica, calcium, and phosphate, which interfere with bacterial membrane perturbation, resulting in higher osmotic pressure [84]. In addition, resin-modified glass ionomers and adhesives containing MBN can release calcium and phosphate, thus improving the mechanical properties of demineralized hard tissues [85,86,88]. Nam confirmed the antibacterial effect of fluorinated bioactive glass NPs added to orthodontic bonding resin on S. mutans [89], and the remineralization ability of MBNs added to a self-adhesive resin and its antibacterial effect on both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria was further proven by Choi et al. [90].

3.1.5 MSNs

The direct bactericidal effect of MSNs has not been reported. Lee et al. first utilized MSNs themselves as antimicrobial additives and an anti-adherent effect against C. albicans and S. oralis was observed with the incorporation of MSNs into PMMA [29]. The major mechanism of the anti-adherent effect against microbes is related to the hydrophilic surface energy. Moreover, in this study, MSN was reported to be a carrier of amphotericin B and the performance after loading amphotericin B into MSN-incorporated PMMA suggested a long-term antimicrobial effect [29].

3.1.6 Nanographene oxide (N-GO)

N-GO has antibacterial activity because it has several chemical groups, which makes it able to form different interactions between covalent and noncovalent, and N-GO may show more activity at the edges than at the surface due to ROS [91]. Pourhajibagher and Bahador [92] highlighted that 5 wt% N-GO could be considered an orthodontic adhesive additive to reduce the microbial count and biofilm with no adverse effect on the shear bond strength and adhesive remnant index. The antibacterial property of N-GO has been proven, and its high water solubility, good biocompatibility, low toxicity, good mechanical properties, and high cost-effectiveness allow it to be used for bacterial inhibition in orthodontic materials.

3.2 Organic NPs

3.2.1 Quaternary ammonium compounds

Polymerizable quaternary ammonium salt (QAS) is a broad-spectrum cationic biocide and possesses significant antibacterial activities against a variety of bacteria, fungi, and viruses [93]. Cationic QAS exhibits the antibacterial effects mainly through extracellular antibacterial effects by attracting and penetrating negatively charged bacterial cell membranes [93,94]. Studies have shown that the addition of insoluble antibacterial quaternary ammonium polycationic polyethyleneimine (PEI) NPs to orthodontic adhesives and cements, such as Neobond and GC Fuji Ortho LC, results in stable antibacterial properties and may prevent S. mutans from growing adjacent to orthodontic appliances [95]. Sharon et al. [96] also confirmed that the addition of quaternary ammonium polyethyleneimine (QPEI) NPs to orthodontic cement appeared to significantly reduce the number of viable S. mutans and Lactobacillus casei, as well as bacterial biomass around orthodontic brackets. In addition, these NPs could be highly effective for months without compromising the chemical, physical, or biological compatibility of the combined base materials [97].

3.3 Natural macromolecule compound NPs

The delivery of traditional antibacterial natural macromolecule compound materials in the form of nanoliposomes and NPs can improve the transport efficiency of drugs and enhance the stability and targeting of drugs, which is the main form of clinical use of nanoantimicrobials at present. Some natural macromolecule compound nanomaterials are reported to exert antimicrobial effects with high levels of biodegradability and biocompatibility without causing toxicity and have been applied in orthodontic materials for antibacterial purposes.

3.3.1 Chitosan NPs

Chitosan is a cationic material, as it contains one primary amine group and chitosan has shown antifungal activity in the free form of the polymer [37] or its derivatives [98,99], especially against C. albicans. Chitosan NPs inhibit bacteria mainly through extracellular antibacterial effects. The antibacterial and antifungal activity of chitosan is mostly associated with its polycationic nature, which interacts with negatively charged phospholipid components on the bacterial and fungal membrane, resulting in increased membrane permeability and the leakage of cellular contents, which subsequently leads to cell death [37,100,101,102]. Hosseinpour et al. [2] added chitosan NPs to orthodontic primers and found their antibacterial activity against S. mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Lactobacillus acidophilus lasted up to 7 days in a rat model.

3.3.2 Curcumin NPs and curcumin-doped poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) NPs

Curcumin is a natural hydrophobic compound derived from the common food spice rhizome of Curcuma longa (turmeric) with therapeutic properties, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and wound healing properties [103]. Curcumin can inhibit the growth and proliferation of many bacterial strains, such as staphylococci, lactobacilli, and streptococci, and its antibacterial activity is attributed to the destruction of the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall [104]. Curcumin has been proven to have antibacterial activity against S. mutans, S. sanguinis, and L. acidophilus when added to orthodontic adhesives [105]. The application of curcumin has been limited by its poor bioavailability due to its low water solubility, poor permeability, and rapid metabolism. PLGA has been used to carry curcumin for antibacterial purposes because of its sustained drug delivery, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and high stability in biological fluids and during storage [106,107], and curcumin-doped poly lactic-co-glycolic acid NPs (Cur-PLGA-NPs) have been proven to serve as an orthodontic adhesive additive with anti-biofilm activity and can be used to control S. mutans biofilm formation [108].

4 Biocompatibility and safety of antibacterial NPs applied in orthodontic materials

The biocompatibility and safety of nanomaterials and NPs remain uncertain. The toxicity of antibacterial NPs is affected by many factors, such as NP type, dose, particle size, distribution, action duration, concentration, and interaction with other compounds. Some researchers have pointed out that there are current limitations of NPs applied in the dental sector related to the topics of biocompatibility and safety [109], while others have suggested that there is little evidence for these limitations [110]. Previous studies on NPs applied in orthodontic materials usually investigated the antibacterial characteristics for very short periods, varying from days to a few weeks, and were mostly carried out under in vitro conditions, which could not provide sufficient evidence for biocompatibility and safety. The long-term performance of orthodontic materials with NPs needs further investigation to develop fully biocompatible and safe nanomaterials [111,112,113].

5 Materials with antibacterial NPs and the main bacteria inhibited in orthodontic therapy

Microorganisms mainly exist in the form of biofilms on the surface of teeth, oral mucosa, and oral materials. Oral flora imbalance during orthodontic treatment can lead to oral infectious diseases, including dental caries, periodontal disease, candidiasis, endodontic infections, orthodontic infections, and peri-implantitis [65,114]. The antibacterial NPs applied in orthodontic materials are mainly used to prevent and solve these oral infections. Commonly used orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries with NPs for antibacterial usage are described as follows.

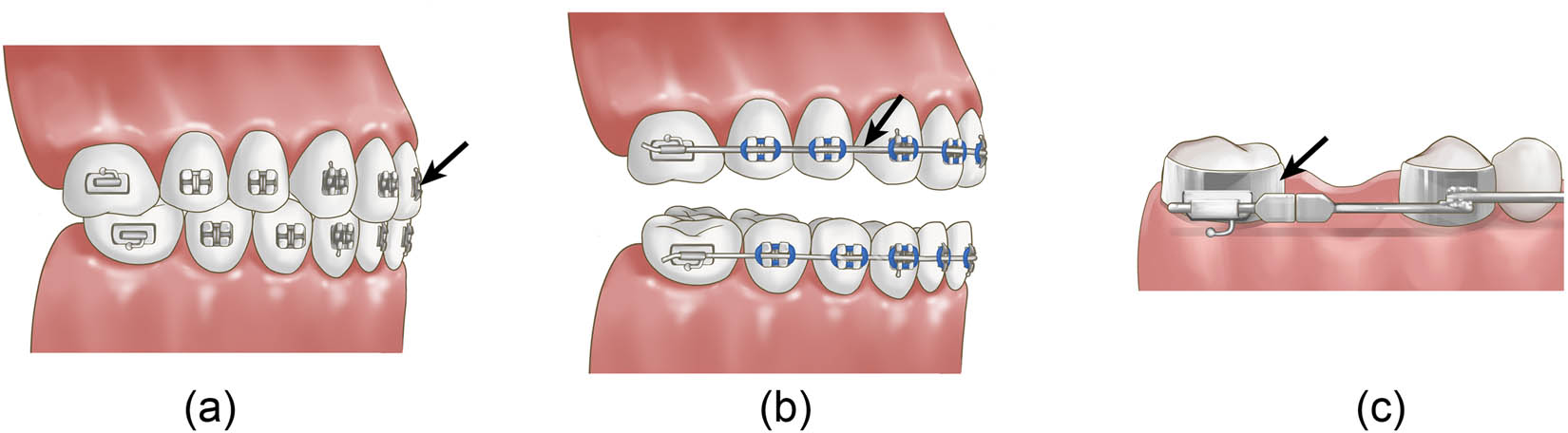

(a) Orthodontic stainless-steel brackets; (b) orthodontic metal archwires; and (c) orthodontic stainless-steel bands (black arrow points).

Previous antibacterial NPs used in orthodontic appliances and the components

| Ref. | Orthodontic appliances and the components | NPs used | Bacterial tested | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jasso-Ruiz et al. [15] | Orthodontic brackets | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| S. sobrinus | ||||

| Metin-Gursoy et al. [56] | Orthodontic brackets | Ag NPs | S. mutans | Animal study |

| Salehi et al. [116] | Orthodontic brackets | N-doped TiO2 NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Ghasemi et al. [117] | Orthodontic brackets | Ag NPs, titanium oxide NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Zhang et al. [118] | Orthodontic brackets | Ag/TiO2 NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | ||||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | ||||

| P. gingivalis | ||||

| Prevotella intermedia | ||||

| Mhaske et al. [123] | Orthodontic archwires | Ag NPs | L. acidophilus | In vitro |

| Kachoei et al. [124] | Orthodontic archwires | ZnO NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Hammad et al. [69] | Orthodontic archwires | Mesoporous silica NPs | S. aureus | In vitro |

| S. pyogenes | ||||

| E. coli | ||||

| Prabha et al. [126] | Orthodontic bands | Ag NPs | Gram-positive bacteria (not specified) | In vitro |

| Farhadian et al. [59] | Removable orthodontic appliances and retainers | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Ghorbanzadeh et al. [128] | Removable orthodontic appliances and retainers | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vivo |

| S. sobrinus | ||||

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| L. casei | ||||

| Lee et al. [29] | Removable orthodontic appliances and retainers | Mesoporous silica NPs | C. albicans | In vitro |

| S. oralis | ||||

| Zhang et al. [63] | Clear aligners | 4,6-Diamino-2-pyrimidinethiol-modified Au NPs | P. gingivalis | In vitro |

5.1 Orthodontic appliances and the components

5.1.1 Orthodontic stainless-steel brackets

Brackets are necessary tools in fixed orthodontic treatment, and the potential accumulation of microbial biofilm may lead to enamel demineralization around the brackets [115]. Stainless-steel brackets are mostly used in fixed orthodontic treatment. As shown in Table 1, various NPs used in orthodontic brackets have been proven to have effective antibacterial activity. Jasso-Ruiz evaluated the anti-adherent and antibacterial properties of different nanosilver-modified orthodontic brackets with radiomarkers and found that nanosilver-modified brackets could inhibit the biological activities of S. mutans and S. sobrinus, indicating that nanosilver-modified brackets can prevent the accumulation of dental plaque and the occurrence of dental caries during orthodontic treatment [15]. Furthermore, Metin-Gursoy also confirmed the antibacterial effect of nanosilver-coated orthodontic brackets on S. mutans through an in vivo experiment in rats [56]. Salehi found that N-doped TiO2-coated orthodontic brackets could prevent the growth of S. mutans for at least 3 months and could effectively prevent enamel decalcification during orthodontic treatment [116]. Ghasemi found that 60 and 100 μm films of Ag NPs and titanium oxide NPs can be coated on brackets to efficiently reduce bacterial count after 3 h [117]. Zhang et al. suggested that nano-Ag/TiO2-coated brackets had antibacterial activity against several kinds of bacteria in the dark, and the antibacterial activity after 20 min could reach 79% (Table 1 and Figure 2a) [118].

5.1.2 Orthodontic metal archwires

As an indispensable role in fixed orthodontic treatment, archwires have mainly been studied to reduce the coefficient of friction to improve treatment efficiency [119]. With the development of nanotechnology in the dental field, some NPs were reported to be combined with orthodontic archwires and exhibited the ability to reduce friction and inhibit bacteria in the form of coatings. As shown in previous studies, NPs are deposited on the orthodontic archwire as a spacer to decrease the surface sharpness and frictional forces between the archwire and the orthodontic bracket [120,121] and protect the metallic wires against oxidation [122] to achieve the goal of friction reduction. In addition, surface modification of orthodontic archwires with Ag NPs has been reported to prevent the accumulation of dental plaque and the development of dental caries during orthodontic treatment [123]. Orthodontic archwires coated with ZnO NPs also exhibit significant antibacterial activity against S. mutans [124], S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and E. coli while reducing friction [69]. Since few studies have been conducted on both friction reduction and the antibacterial properties of orthodontic archwires coated with NPs, no correlation between these two characteristics has been reported (Figure 2b).

5.1.3 Orthodontic stainless-steel bands

Orthodontic bands are seated in supra- and subgingival areas, which may compromise the health of the surrounding periodontal tissues and can be associated with the occurrence of periodontopathogenic bacteria [125]. Prabha et al. coated orthodontic bands with Ag NPs and concluded that the coated bands were biocompatible, possessed distinct antimicrobial activity, and could be potential antimicrobial dental bands for future clinical use (Figure 2c) [126].

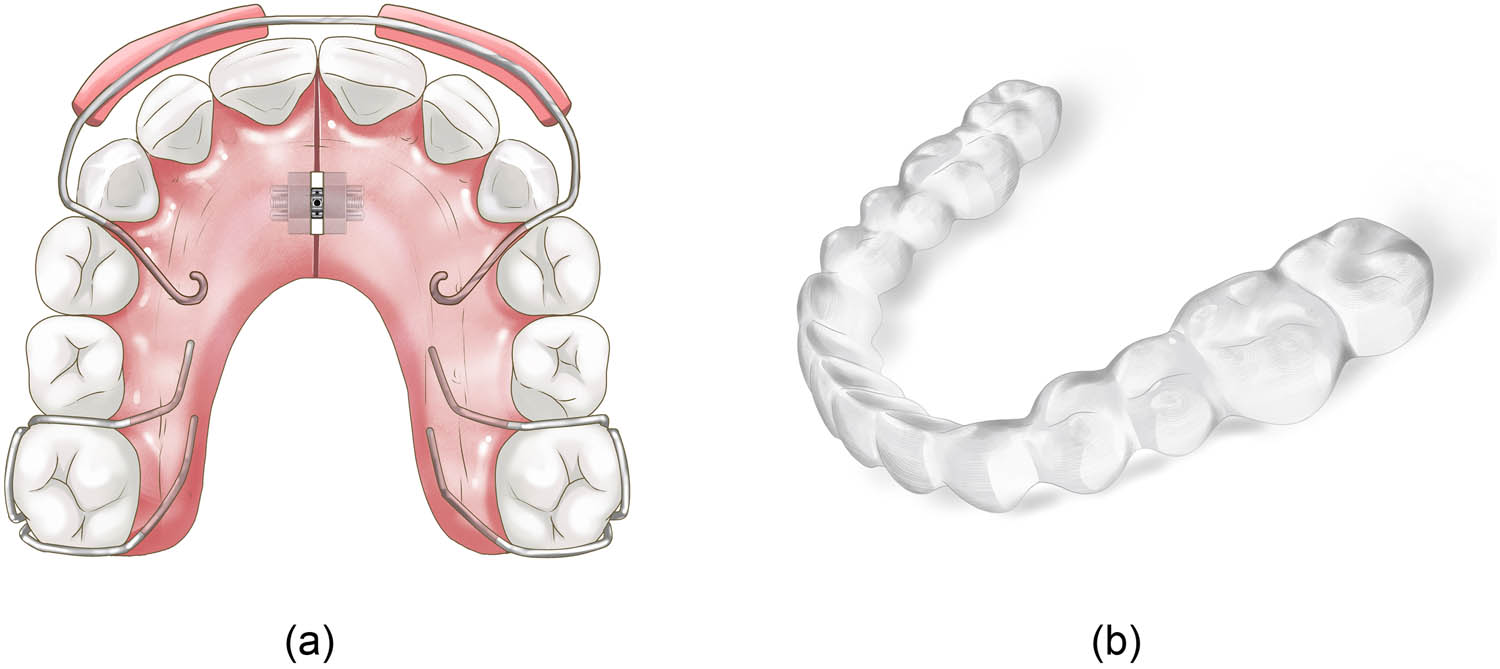

(a) Traditional removable orthodontic appliances and (b) clear aligner.

5.1.4 Removable orthodontic appliances

The use of orthodontic acrylic resins in the fabrication of removable orthodontic appliances and retainers (Figure 3a) is increasing due to the growing demand for orthodontic treatments [11]. The accumulation of microorganisms on acrylic resins increases the incidence of caries and oral diseases and jeopardizes the efficiency of orthodontic treatments [127]. The use of antibacterial materials in acrylic resin of removable orthodontic appliances and retainers is helpful to reduce bacterial aggregation during orthodontic treatments. In a randomized clinical trial, Ghorbanzadeh found that the average levels of test cariogenic bacteria in saliva decreased approximately 2- to 70-fold (30.9–98.4%) in patients wearing orthodontic appliances with in situ-generated Ag NPs compared to those wearing normal baseplates of orthodontic appliances [128]. Farhadian found that Ag NPs with a 500 ppm concentration and 40 nm size incorporated into the acrylic plate of retainers had a strong antimicrobial effect against S. mutans colony-forming units under clinical conditions [59]. An anti-adherent effect against C. albicans and S. oralis was observed with the incorporation of MSNs into PMMA and MSN has been reported to be a carrier of amphotericin B. The performance after loading amphotericin B into the MSN-incorporated PMMA suggested a long-term antimicrobial effect (Figure 3) [29].

Despite the traditional removable orthodontic appliances made of acrylic resins, clear aligners (Figure 3b) are made of a transparent polymer material, which is a new trend in orthodontic treatment in recent years, and more patients tend to choose clear aligners as orthodontic appliances than fixed appliances and traditional removable orthodontic appliances due to their esthetics and comfort. During clear aligner treatment, both the teeth and gingiva are covered for nearly the entire day with aligners. Thus, with proper modification, clear aligners may be used as a long-term drug delivery system for patients with P. gingivalis infection [63]. Zhang coated antibacterial AuDAPTs over clear aligners, and these AuDAPT-coated aligners exhibited antibacterial effects on a suspension of P. gingivalis, affecting the neighboring area of the material, slowing biofilm formation, and showing favorable biocompatibility [63].

5.2 Orthodontic auxiliaries

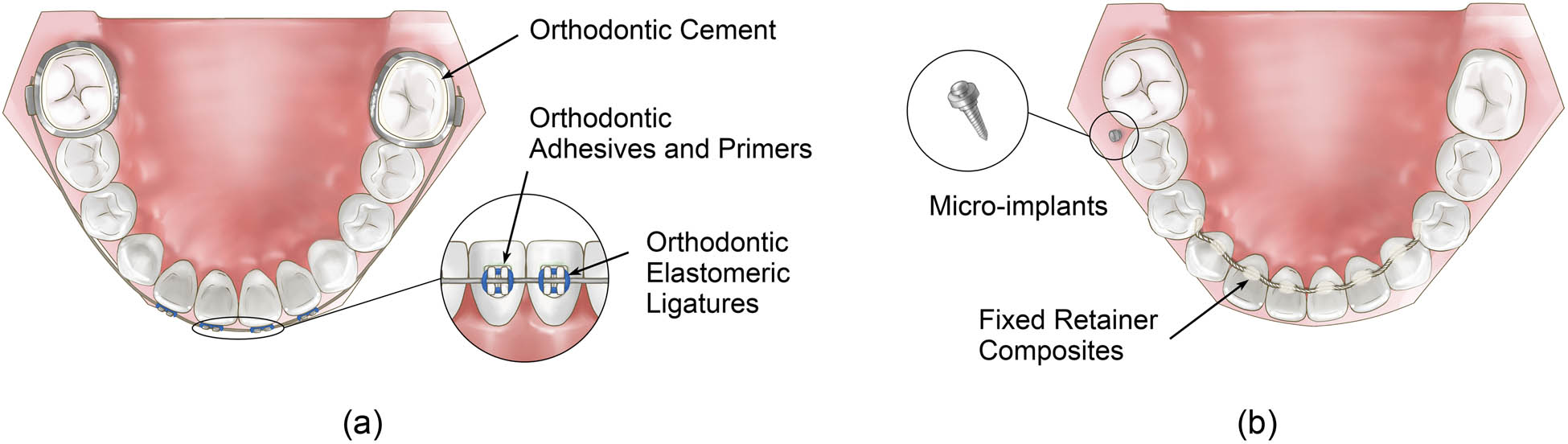

5.2.1 Orthodontic adhesives and primers

Orthodontic resin, including orthodontic adhesive and primer, is a binder between an orthodontic bracket and tooth enamel that contacts the tooth surface directly. White spot lesions or enamel demineralization caused by acid biofilms usually develop in areas adjacent to orthodontic brackets [129]. To overcome these damages, antibacterial adhesives and primers containing different NPs were studied. As a commonly used antibacterial material, silver has been added to orthodontic adhesives in the form of NPs, which showed obvious antibacterial effects [58,130,131], and a 5% concentration was reported to be the minimum concentration of Ag NPs with optimal antimicrobial efficacy against S. sanguinis, L. acidophilus, and S. mutans [131]. The antibacterial effect of Cu NPs on S. aureus, E. coli, and S. mutans was also found when 0.0100 wt% Cu NPs were added to the orthodontic adhesive [64]. Bioactive glass NPs were added to a self-adhesive resin and a statistically significant antibacterial effect was found at the concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 wt% [90]. In addition, the antibacterial properties of other NPs in orthodontic resin were studied and their antibacterial effects were reported, including CuO NPs at the concentration of 0.01, 0.5, and 1.0 wt% [67]; TiO2 NPs at the concentration of 1, 5, and 10 wt% [132]; Ag/hydroxyapatite NPs at the concentration of 5 and 10 wt% [133]; yttrium(iii) fluoride NPs at the best concentration of 1 wt% [82]; cCur/ZnO NPs at the best concentration of 7.5 wt% [70]; fluorinated bioactive glass NPs [89]; amorphous calcium phosphate NPs at a concentration of 5 wt% [134]; curcumin NPs at the best concentration of 1 wt% [105]; curcumin-doped poly lactic-co-glycolic acid NPs at the best concentration of 7 wt% [108]; chitosan NPs at the best concentration of 5 wt% [2]; polycationic PEI-based NPs at the best concentration of 1.5 wt% [135]; and graphene oxide NPs at a concentration of 5 wt% (Table 2 and Figure 4a) [92].

(a and b) Orthodontic auxiliaries.

Previous antibacterial NPs used in orthodontic auxiliaries

| Ref. | Orthodontic auxiliaries | NPs used | Bacterial tested | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanchez-Tito and Tay [58] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| Eslamian et al. [130] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Bahador et al. [131] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Ag NPs | S. sanguinis | Animal study |

| S. mutans | ||||

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| Argueta-Figueroa et al. [64] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Copper NPs | S. aureus | In vitro |

| E. coli | ||||

| S. mutans | ||||

| Nam et al. [89] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Fluorinated bioactive glass NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Choi et al. [90] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Mesoporous bioactive glass NPs | Gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria | In vitro |

| Toodehzaeim et al. [67] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | CuO NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Sodagar et al. [132] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | TiO2 NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| Sodagar et al. [133] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Ag/hydroxyapatite NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| Asiry et al. [82] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Yttrium(iii) fluoride NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Pourhajibagher et al. [70] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Cationic curcumin-doped zinc oxide NPs | Biofilm | In vitro |

| Liu et al. [134] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Amorphous calcium phosphate NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Sodagar et al. [105] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Curcumin NPs | S. mutans, S. sanguinis, L. acidophilus | In vitro |

| Ahmadi et al. [108] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Curcumin-doped poly lactic-co-glycolic acid NPs | Biofilm | In vitro |

| Hosseinpour et al. [2] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | Chitosan NPs | S. mutans | Animal study |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| Zaltsman et al. [135] | Orthodontic adhesives and primers | QPEI NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Pourhajibagher and Bahador et al. [92] | Orthodontic adhesives | Graphene oxide NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Ren et al. [43] | Orthodontic cement | TiO2 NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Zhang et al. [57] | Orthodontic cement | Ag NPs | Biofilm and plaque | In vitro |

| Wang et al. [136] | Orthodontic cement | Ag NPs | Biofilm and plaque | In vitro |

| Moreira et al. [137] | Orthodontic cement | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| Yi et al. [83] | Orthodontic cement | CaF2 NPs | Biofilm | In vitro |

| Sharon et al. [96] | Orthodontic cement | Quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine NPs | S. mutans, L. casei | In vitro |

| Varon-Shahar et al. [95] | Orthodontic cement | Polycationic PEI-based NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| Mirhashemi et al. [139] | Fixed retainer composites | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| L. acidophilus | ||||

| Kotta et al. [75] | Fixed retainer composites | TiO2 NPs | Biofilm | In vitro |

| Hernandez-Gomora et al. [60] | Orthodontic elastomeric ligatures | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| L. casei | ||||

| S. aureus | ||||

| E. coli | ||||

| Venugopal et al. [143] | Micro-implants | Ag NPs | S. mutans | In vitro |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | ||||

| Qiang et al. [142] | Micro-implants | Ag NPs | E. coli | In vitro |

| S. aureus |

5.2.2 Orthodontic cement

As a new adhesive material, glass ionomer cement is the product of the interaction between fluoro aluminosilicate glass powder and polyacrylic acid aqueous solution [43]. It is widely used in the bonding of brackets and bands and so on in orthodontic treatment. The performance of orthodontic cement directly affects the curative effect of orthodontic treatment. To improve the antibacterial performance of orthodontic cement, different kinds of NPs were added to the orthodontic cement, and their antibacterial properties were tested. Ren added different proportions of titanium dioxide NPs to traditional glass ion cement and found that the antibacterial effect against S. mutans of glass ion cement significantly improved at a concentration of 10 wt% [43]. In addition, some different NPs, including Ag NPs at a concentration of 0.1 wt% [57,136,138], nano-CaF2 at a concentration of 20 wt% [83], quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine NPs at a concentration of 1 wt% [96], and polycationic PEI-based NPs at a concentration of 1 wt% [95], were added to orthodontic cement and proved to be effective antibacterial agents (Figure 4a).

5.2.3 Fixed retainer composites

Many orthodontists presume that fixed bonded retainers are the only way to obtain the desired alignment after the debonding of orthodontic appliances, especially in the lower anterior segment [138]. The fixed bonded retainer is made of a piece of wire and composite resin bonded to teeth, which means there would be potential bacterial accumulation around the retainer. To overcome microorganism aggregation, researchers have tried to add Ag NPs into the composites of the fixed retainer and more antibacterial effects were observed as the concentration of Ag NPs increased, especially against S. mutans, S. sanguis, and L. acidophilus at the best concentration of 5 wt% [139]. Kotta et al. evaluated the antibacterial activity of retainers bonded with conventional and NP (TiO2)-containing composites and found that composites containing TiO2 at a concentration of 1 wt% showed a statistically significant increase in antibacterial activity (Figure 4b) [75].

5.2.4 Orthodontic elastomeric ligatures

Orthodontic elastomeric ligatures are synthetic elastics made of polyurethane material, with advantages, such as quickness of application, patient comfort, and lower cost than self-ligation clips [140]. However, apart from their practical benefits, elastomeric ligatures exhibit a greater number of microorganisms in the plaque around the brackets than steel ligatures [141]. In the study of Hernandez-Gomora et al., Ag NPs were synthesized in situ on orthodontic elastomeric ligatures and this study suggested the potential of the material to combat dental biofilms and in turn decrease the incidence of demineralization in dental enamel (Figure 4a) [60].

5.2.5 Micro-implants

With the rapid development and advancement in orthodontic and orthopedic technologies, micro-implants are increasingly used for absolute anchorage. Ti-based implants are susceptible to bacterial infections, leading to poor healing and osteointegration and resulting in implant failure or repeated surgical intervention [142]. To reduce bacterial infections and increase the success rate of implants, NPs were used on the micro-implants. Venugopal found that titanium micro-implants modified with AgNP-coated biopolymers exhibited excellent antibacterial properties [143] and in Qiang’s study, the antibacterial properties of Ag NP/silk sericin-coated Ti surfaces were demonstrated to prevent bacterial cell adhesion as well as early-stage biofilm formation and exhibited a negligible level of cytotoxicity in L929 mouse fibroblast cells (Figure 4b) [142].

6 Conclusions and perspectives

Microbial accumulation is a common problem during the orthodontic process. Orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries promote supra- and subgingival biofilm accumulation and hinder oral hygiene, causing adverse effects, such as dental caries and periodontal disease. Studies have shown that, during orthodontic treatment, there is an elevated level of major oral pathogenic pathogens, such as S. mutans [144] and P. gingivalis [145]. Various attempts have been made to increase the antimicrobial properties of orthodontic appliances and auxiliaries, and research on the application of nano-antibacterial materials in orthodontics is also increasing. However, current nanomaterials have not yet achieved the perfect balance of antimicrobial effect and biocompatibility, which should still be further studied. From the aspect of orthodontic materials, clear aligners are a new trend in orthodontic appliances, while there are few studies on the application of NPs in clear aligners for microbe inhibition at present, and antibacterial NPs combined with clear aligners should be given more attention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Ma Yuxing of the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, for drawing the illustrations in this article.

-

Funding information: The present work was funded by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Sichuan Province (No. 22ZDYF2835 and No. 2021YFG0230).

-

Author contributions: Zhang Yun prepared and submitted the manuscript as a co-first author. Du Qin prepared and revised this article as a co-first author. Corresponding authors Li Xiaobing and Fei Wei were responsible for the revision of this article and communication with the editors. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this article and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

[1] Sardana D, Zhang J, Ekambaram M, Yang Y, McGrath CP, Yiu CKY. Effectiveness of professional fluorides against enamel white spot lesions during fixed orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2019;82:1–10.10.1016/j.jdent.2018.12.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Hosseinpour NA, Sodagar A, Akhavan A, Pourhajibagher M, Bahador A. Antibacterial effects of orthodontic primer harboring chitosan nanoparticles against the multispecies biofilm of cariogenic bacteria in a rat model. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2020;62(4):817–24.10.3897/folmed.62.e50200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Hochli D, Hersberger-Zurfluh M, Papageorgiou SN, Eliades T. Interventions for orthodontically induced white spot lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39(2):122–33.10.1093/ejo/cjw065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Chanachai S, Chaichana W, Insee K, Benjakul S, Aupaphong V, Panpisut P. Physical/mechanical and antibacterial properties of orthodontic adhesives containing calcium phosphate and nisin. J Funct Biomater. 2021;12(4):73.10.3390/jfb12040073Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Pourhajibagher M, Salehi-Vaziri A, Noroozian M, Akbar H, Bazarjani F, Ghaffari H, et al. An orthodontic acrylic resin containing seaweed Ulva lactuca as a photoactive phytocompound in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: assessment of anti-biofilm activities and mechanical properties. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2021;35:102295.10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102295Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kumar S, Kavita, Bhatti HS, Singh K, Gupta S, Sharma S, et al. Effect of glutathione capping on the antibacterial activity of tin doped ZnO nanoparticles. Phys Scrip. 2021;96(12):125807 (11pp).10.1088/1402-4896/ac1eb3Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kumar S, Taneja S, Banyal S, Singhal M, Kumar V, Sahare S, et al. Bio-synthesised silver nanoparticle-conjugated L-cysteine ceiled Mn:ZnS quantum dots for eco-friendly biosensor and antimicrobial applications. J Electr Mater. 2021;50(7):3986–95.10.1007/s11664-021-08926-4Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kumar S, Jain A, Panwar S, Sharma I, Jeon HC, Kang TW, et al. Effect of silica on the ZnS nanoparticles for stable and sustainable antibacterial application. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2019;16(2):531–40.10.1111/ijac.13145Search in Google Scholar

[9] Bhattacharya P, Dey A, Neogi. S. An insight into the mechanism of antibacterial activity by magnesium oxide nanoparticles. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(26):5329–39.10.1039/D1TB00875GSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Kumar S, Kang TW, Lee SJ, Yuldashev S, Taneja S, Banyal S, et al. Correlation of antibacterial and time resolved photoluminescence studies using bio-reduced silver nanoparticles conjugated with fluorescent quantum dots as a biomarker. J Mater Sci Mater Electr. 2019;30(7):6977–83.10.1007/s10854-019-01015-7Search in Google Scholar

[11] Shahabi M, Movahedi FS, Rangrazi A. Incorporation of chitosan nanoparticles into a cold-cure ortho-dontic acrylic resin: effects on mechanical properties. Biomimetics (Basel). 2021;6(1):7.10.3390/biomimetics6010007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Cao W, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li Q, Xiao Y, Li P, et al. Novel resin-based dental material with anti-biofilm activity and improved mechanical property by incorporating hydrophilic cationic copolymer functionalized nanodiamond. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2018;29(11):162.10.1007/s10856-018-6172-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Saafan A, Zaazou MH, Sallam MK, Mosallam O, El Danaf HA. Assessment of photodynamic therapy and nanoparticles effects on caries models. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(7):1289–95.10.3889/oamjms.2018.241Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi E, Lynch E. Nanoparticles in orthodontics, a review of antimicrobial and anti-caries applications. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(6):413–7.10.3109/00016357.2013.859728Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Jasso-Ruiz I, Velazquez-Enriquez U, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Morales-Luckie RA, Sawada T, Yamaguchi R. Silver nanoparticles in orthodontics, a new alternative in bacterial inhibition: in vitro study. Prog Orthod. 2020;21(1):24.10.1186/s40510-020-00324-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Behroozian A, Kachoei M, Khatamian M, Divband B. The effect of ZnO nanoparticle coating on the frictional resistance between orthodontic wires and ceramic brackets. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2016;10(2):106.10.15171/joddd.2016.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Felemban NH, Ebrahim MI. The influence of adding modified zirconium oxide-titanium dioxide nano-particles on mechanical properties of orthodontic adhesive: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):43.10.1186/s12903-017-0332-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Zakrzewski W, Dobrzynsk M, Dobrzynski W, Zawadzka-Knefel A, Janecki M, Kurek K, et al. Nanomaterials application in orthodontics. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(2):337.10.3390/nano11020337Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Li H, Chen Q, Zhao J, Urmila K. Enhancing the antimicrobial activity of natural extraction using the synthetic ultrasmall metal nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):11033.10.1038/srep11033Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Armentano I, Arciola CR, Fortunati E, Ferrari D, Mattioli S, Amoroso CF, et al. The interaction of bacteria with engineered nanostructured polymeric materials: a review. Sci World J. 2014;2014(3):410423.10.1155/2014/410423Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Gao W, Thamphiwatana S, Angsantikul P, Zhang L. Nanoparticle approaches against bacterial infections. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2014;6(6):532–47.10.1002/wnan.1282Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Luan B, Huynh T, Zhou R. Complete wetting of graphene by biological lipids. Nanoscale. 2016;8(10):5750–4.10.1039/C6NR00202ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] DeQueiroz GA, Day DF. Antimicrobial activity and effectiveness of a combination of sodium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide in killing and removing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms from surfaces. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103(4):794–802.10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03299.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Peng Z, Ni J, Zheng K, Shen Y, Wang X, He G, et al. Dual effects and mechanism of TiO2 nanotube arrays in reducing bacterial colonization and enhancing C3H10T1/2 cell adhesion. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:3093–105.10.2147/IJN.S48084Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Su HL, Chou CC, Hung DJ, Lin SH, Pao IC, Lin JH, et al. The disruption of bacterial membrane integrity through ROS generation induced by nanohybrids of silver and clay. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):5979–87.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Lundberg ME, Becker EC, Choe S. MstX and a putative potassium channel facilitate biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e60993.10.1371/journal.pone.0060993Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Pan F, Xu A, Xia D, Yu Y, Chen G, Meyer M, et al. Effects of octahedral molecular sieve on treatment performance, microbial metabolism, and microbial community in expanded granular sludge bed reactor. Water Res. 2015;87:127–36.10.1016/j.watres.2015.09.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Lellouche J, Friedman A, Lellouche JP, Gedanken A, Banin E. Improved antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of magnesium fluoride nanoparticles obtained by water-based ultrasound chemistry. Nanomedicine. 2012;8(5):702–11.10.1016/j.nano.2011.09.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lee JH, El-Fiqi A, Jo JK, Kim DA, Kim SC, Jun SK, et al. Development of long-term antimicrobial poly(methyl methacrylate) by incorporating mesoporous silica nanocarriers. Dent Mater. 2016;32(12):1564–74.10.1016/j.dental.2016.09.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Tang YJ, Ashcroft JM, Chen D, Min G, Kim CH, Murkhejee B, et al. Charge-associated effects of fullerene derivatives on microbial structural integrity and central metabolism. Nano Lett. 2007;7(3):754–60.10.1021/nl063020tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Brayner R, Ferrari-Iliou R, Brivois N, Djediat S, Benedetti MF, Fievet F. Toxicological impact studies based on Escherichia coli bacteria in ultrafine ZnO nanoparticles colloidal medium. Nano Lett. 2006;6(4):866–70.10.1021/nl052326hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Wang Y, Huang F, Pan D, Li B, Chen D, Lin W, et al. Ultraviolet-light-induced bactericidal mechanism on ZnO single crystals. Chem Commun (Camb). 2009;2009(44):6783–5.10.1039/b912137dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;275(1):177–82.10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Ni Z, Gu X, He Y, Wang Z, Zou X, Zhao Y, et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticle-decorated hydroxyapatite (HA@Ag) poriferous nanocomposites and the study of their antibacterial activities. RSC Adv. 2018;8(73):41722–30.10.1039/C8RA08148DSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Wu Y, Yang Y, Zhang Z, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Sun L. A facile method to prepare size-tunable silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial mechanism. Adv Powder Technol. 2018;29(2):407–15.10.1016/j.apt.2017.11.028Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ni Z, Wang Z, Sun L, Li B, Zhao. Y. Synthesis of poly acrylic acid modified silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activities. Mater Sci Eng C. 2014;41:249–54.10.1016/j.msec.2014.04.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Ing LY, Zin NM, Sarwar A, Katas H. Antifungal activity of chitosan nanoparticles and correlation with their physical properties. Int J Biomater. 2012;2012:632698.10.1155/2012/632698Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:1227–49.10.2147/IJN.S121956Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Li Y, Zhang W, Niu J, Chen Y. Mechanism of photogenerated reactive oxygen species and correlation with the antibacterial properties of engineered metal-oxide nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2012;6(6):5164–73.10.1021/nn300934kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Cheloni G, Marti E, Slaveykova VI. Interactive effects of copper oxide nanoparticles and light to green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Aquat Toxicol. 2016;170:120–8.10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.11.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Danilczuk M, Lund A, Sadlo J, Yamada H, Michalik J. Conduction electron spin resonance of small silver particles. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2006;63(1):189–91.10.1016/j.saa.2005.05.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, Kim JH, Park SJ, Lee HJ, et al. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;3(1):95–101.10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Ren J, Du Z, Lin J. Applied research glass ionomer cement with TiO2 nanoparticles in orthodontic treatment. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2021;21(2):1032–41.10.1166/jnn.2021.18681Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Padmavathy N, Vijayaraghavan R. Interaction of ZnO nanoparticles with microbes – a physio and biochemical assay. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7(6):813–22.10.1166/jbn.2011.1343Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Gao M, Sun L, Wang Z, Zhao Y. Controlled synthesis of Ag nanoparticles with different morphologies and their antibacterial properties. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33(1):397–404.10.1016/j.msec.2012.09.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Wu B, Zhuang WQ, Sahu M, Biswas P, Tang YJ. Cu-doped TiO2 nanoparticles enhance survival of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 under ultraviolet light (UV) exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(21):4635–9.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Yu J, Zhang W, Li Y, Wang G, Yang L, Jin J, et al. Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial activity and mechanism of a novel hydroxyapatite whisker/nano zinc oxide biomaterial. Biomed Mater. 2014;10(1):015001.10.1088/1748-6041/10/1/015001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Liao C, Li Y, Tjong SC. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(2):449–9.10.3390/ijms20020449Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Yin IX, Zhang J, Zhao IS, Mei ML, Li Q, Chu CH. The antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles and its application in dentistry. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:2555–62.10.2147/IJN.S246764Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Morones JR, Elechiguerra JL, Camacho A, Holt K, Kouri JB, Ramirez JT, et al. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2005;16(10):2346–53.10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Feng QL, Wu J, Chen GQ, Cui FZ, Kim TN, Kim JO. A mechanistic study of the antibacterial effect of silver ions on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52(4):662–8.10.1002/1097-4636(20001215)52:4<662::AID-JBM10>3.0.CO;2-3Search in Google Scholar

[52] Yamanaka M, Hara K, Kudo J. Bactericidal actions of a silver ion solution on Escherichia coli, studied by energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy and proteomic analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(11):7589–93.10.1128/AEM.71.11.7589-7593.2005Search in Google Scholar

[53] Li Y, Yang C, Yin X, Sun Y, Weng J, Zhou J, et al. Inflammatory responses to micro/nano-structured titanium surfaces with silver nanoparticles in vitro. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(22):3546–59.10.1039/C8TB03245ASearch in Google Scholar

[54] Chiloeches A, Echeverría C, Cuervo-Rodríguez R, Plachà D, López-Fabal F, Fernández-García M, et al. Adhesive antibacterial coatings based on copolymers bearing thiazolium cationic groups and catechol moieties as robust anchors. Prog Org Coat. 2019;136(11):105272.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105272Search in Google Scholar

[55] Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN, Dibo SA. Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature. Burns. 2007;33(2):139–48.10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010Search in Google Scholar

[56] Metin-Gursoy G, Taner L, Akca G. Nanosilver coated orthodontic brackets: in vivo antibacterial properties and ion release. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39(1):9–16.10.1093/ejo/cjv097Search in Google Scholar

[57] Zhang N, Melo M, Antonucci JM, Lin NJ, Lin-Gibson S, Bai Y, et al. Novel dental cement to combat biofilms and reduce acids for orthodontic applications to avoid enamel demineralization. Materials (Basel). 2016;9(6):413.10.3390/ma9060413Search in Google Scholar

[58] Sanchez-Tito M, Tay LY. Antibacterial and white spot lesions preventive effect of an orthodontic resin modified with silver-nanoparticles. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021;13(7):e685–91.10.4317/jced.58330Search in Google Scholar

[59] Farhadian N, Usefi MR, Khanizadeh S, Ghaderi E, Farhadian M, Miresmaeili A. Streptococcus mutans counts in patients wearing removable retainers with silver nanoparticles vs those wearing conventional retainers: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dent Orthop. 2016;149(2):155–60.10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.07.031Search in Google Scholar

[60] Hernandez-Gomora AE, Lara-Carrillo E, Robles-Navarro JB, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Hernandez-Lopez S, Medina-Solis CE, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on orthodontic elastomeric modules: evaluation of mechanical and antibacterial properties. Molecules. 2017;22(9):1407.10.3390/molecules22091407Search in Google Scholar

[61] Xie Y, Xianyu Y, Wang N. Functionalized gold nanoclusters identify highly reactive oxygen species in living organisms. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(14):1702026.10.1002/adfm.201702026Search in Google Scholar

[62] Zhao Y, Tian Y, Cui Y, Liu W, Ma W, Jiang X. Small molecule-capped gold nanoparticles as potent antibacterial agents that target Gram-negative bacteria. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(35):12349–56.10.1021/ja1028843Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Zhang M, Liu X, Xie Y, Zhang Q, Zhang W, Jiang X, et al. Biological safe gold nanoparticle-modified dental aligner prevents the porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm formation. ACS Omega. 2020;5(30):18685–92.10.1021/acsomega.0c01532Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Argueta-Figueroa L, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Morales-Luckie RA, Olea-Mejia OF. An evaluation of the antibacterial properties and shear bond strength of copper nanoparticles as a nanofiller in orthodontic adhesive. Aust Orthod J. 2015;31(1):42–8.10.21307/aoj-2020-139Search in Google Scholar

[65] Allaker RP, Memarzadeh K. Nanoparticles and the control of oral infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(2):95–104.10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.11.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Khan ST, Ahamed M, Al-Khedhairy A, Musarrat J. Biocidal effect of copper and zinc oxide nanoparticles on human oral microbiome and biofilm formation. Mater Lett. 2013;97:67–70.10.1016/j.matlet.2013.01.085Search in Google Scholar

[67] Toodehzaeim MH, Zandi H, Meshkani H, Firouzabadi AH. The effect of CuO nanoparticles on antimicrobial effects and shear bond strength of orthodontic adhesives. J Dent (Shiraz). 2018;19(1):1–5.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Dizaj SM, Lotfipour F, Barzegar-Jalali M, Zarrintan MH, Adibkia K. Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;44:278–84.10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Hammad SM, El-Wassefy NA, Shamaa MS, Fathy A. Evaluation of zinc-oxide nanocoating on the characteristics and antibacterial behavior of nickel-titanium alloy. Dental Press J Orthod. 2020;25(4):51–8.10.1590/2177-6709.25.4.051-058.oarSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Pourhajibagher M, Salehi VA, Takzaree N, Ghorbanzadeh R. Physico-mechanical and antimicrobial properties of an orthodontic adhesive containing cationic curcumin doped zinc oxide nanoparticles subjected to photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2019;25:239–46.10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.01.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Cao B, Wang Y, Li N, Liu B, Zhang Y. Preparation of an orthodontic bracket coated with an nitrogen-doped TiO2-xNy thin film and examination of its antimicrobial performance. Dent Mater J. 2013;32(2):311–6.10.4012/dmj.2012-155Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Kuhn KP, Chaberny IF, Massholder K, Stickler M, Benz VW, Sonntag HG, et al. Disinfection of surfaces by photocatalytic oxidation with titanium dioxide and UVA light. Chemosphere. 2003;53(1):71–7.10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00362-XSearch in Google Scholar

[73] Lee MC, Yoshino F, Shoji H, Takahashi S, Todoki K, Shimada S, et al. Characterization by electron spin resonance spectroscopy of reactive oxygen species generated by titanium dioxide and hydrogen peroxide. J Dent Res. 2005;84(2):178–82.10.1177/154405910508400213Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Shirai R, Miura T, Yoshida A, Yoshino F, Ito T, Yoshinari M, et al. Antimicrobial effect of titanium dioxide after ultraviolet irradiation against periodontal pathogen. Dent Mater J. 2016;35(3):511–6.10.4012/dmj.2015-406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Kotta M, Gorantla S, Muddada V, Lenka RR, Karri T, Kumar S, et al. Antibacterial activity and debonding force of different lingual retainers bonded with conventional composite and nanoparticle containing composite: an in vitro study. J World Fed Orthod. 2020;9(2):80–5.10.1016/j.ejwf.2020.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Ge L, Li Q, Wang M, Ouyang J, Li X, Xing MM. Nanosilver particles in medical applications: synthesis, performance, and toxicity. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9(1):2399–407.10.2147/IJN.S55015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[77] Chang YN, Zhang M, Xia L, Zhang J, Xing G. The toxic effects and mechanisms of CuO and ZnO nanoparticles. Materials. 2012;5:2850–71.10.3390/ma5122850Search in Google Scholar

[78] Cury JA, Tenuta LM. Enamel remineralization: controlling the caries disease or treating early caries lesions? Braz Oral Res. 2009;23(Suppl 1):23–30.10.1590/S1806-83242009000500005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Lellouche J, Friedman A, Gedanken A, Banin E. Antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of yttrium fluoride nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:5611–24.10.2147/IJN.S37075Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[80] Zheng X, Cheng X, Wang L, Qiu W, Wang S, Zhou Y, et al. Combinatorial effects of arginine and fluoride on oral bacteria. J Dent Res. 2015;94(2):344–53.10.1177/0022034514561259Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[81] Van Loveren C. Antimicrobial activity of fluoride and its in vivo importance: identification of research questions. Caries Res. 2001;35(Suppl 1):65–70.10.1159/000049114Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Asiry MA, Alshahrani I, Alqahtani ND, Durgesh H, B. Efficacy of yttrium(iii) fluoride nanoparticles in orthodontic bonding. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2019;19(2):1105–10.10.1166/jnn.2019.15894Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Yi J, Dai Q, Weir MD, Melo MAS, Lynch CD, Oates TW, et al. A nano-CaF2-containing orthodontic cement with antibacterial and remineralization capabilities to combat enamel white spot lesions. J Dent. 2019;89:103172.10.1016/j.jdent.2019.07.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] El-Fiqi A, Lee JH, Lee EJ, Kim HW. Collagen hydrogels incorporated with surface-aminated mesoporous nanobioactive glass: Improvement of physicochemical stability and mechanical properties is effective for hard tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(12):9508–21.10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] Jang JH, Lee MG, Ferracane JL, Davis H, Bae HE, Choi D, et al. Effect of bioactive glass-containing resin composite on dentin remineralization. J Dent. 2018;75:58–64.10.1016/j.jdent.2018.05.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Thompson ID, Hench LL. Mechanical properties of bioactive glasses, glass-ceramics and composites. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1998;212(2):127–36.10.1243/0954411981533908Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Drago L, Toscano M, Bottagisio M. Recent evidence on bioactive glass antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity: a mini-review. Materials (Basel). 2018;11(2):326–6.10.3390/ma11020326Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[88] Hench LL. The story of bioglass. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(11):967–78.10.1007/s10856-006-0432-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Nam HJ, Kim YM, Kwon YH, Yoo KH, Yoon SY, Kim IR, et al. Fluorinated bioactive glass nanoparticles: enamel demineralization prevention and antibacterial effect of orthodontic bonding resin. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(11):1813–3.10.3390/ma12111813Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[90] Choi A, Yoo KH, Yoon SY, Park BS, Kim IR, Kim YI, et al. Anti-microbial and remineralizing properties of self-adhesive orthodontic resin containing mesoporous bioactive glass. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(13):3550.10.3390/ma14133550Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Zhou T, Zhou X, Xing D. Controlled release of doxorubicin from graphene oxide based charge-reversal nanocarrier. Biomaterials. 2014;35(13):4185–94.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Pourhajibagher M, Bahador A. Orthodontic adhesive doped with nano-graphene oxide: physico-mechanical and antimicrobial properties. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2021;63(3):413–21.10.3897/folmed.63.e53716Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Huang L, Xiao YH, Xing XD, Li F, Ma S, Qi LL, et al. Antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of two novel cross-linking antibacterial monomers on oral pathogens. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56(4):367–73.10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.10.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[94] Li F, Chai ZG, Sun MN, Wang F, Ma S, Zhang L, et al. Anti-biofilm effect of dental adhesive with cationic monomer. J Dent Res. 2009;88(4):372–6.10.1177/0022034509334499Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[95] Varon-Shahar E, Sharon E, Zabrovsky A, Houri-Haddad Y, Beyth N. Antibacterial orthodontic cements and adhesives: a possible solution to streptococcus mutans outgrowth adjacent to orthodontic appliances. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2019;17(1):49–56.Search in Google Scholar

[96] Sharon E, Sharabi R, Eden A, Zabrovsky A, Ben-Gal G, Sharon E, et al. Antibacterial activity of orthodontic cement containing quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine nanoparticles adjacent to orthodontic brackets. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):606.10.3390/ijerph15040606Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[97] Beyth N, Yudovin-Farber I, Perez-Davidi M, Domb AJ, Weiss EI. Polyethyleneimine nanoparticles incorporated into resin composite cause cell death and trigger biofilm stress in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(51):22038–43.10.1073/pnas.1010341107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[98] Kulikov SN, Lisovskaya SA, Zelenikhin PV, Bezrodnykh EA, Shakirova DR, Blagodatskikh IV, et al. Antifungal activity of oligochitosans (short chain chitosans) against some Candida species and clinical isolates of Candida albicans: molecular weight-activity relationship. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;74:169–78.10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.12.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[99] Silva-Dias A, Palmeira-de-Oliveira A, Miranda IM, Branco J, Cobrado L, Monteiro-Soares M, et al. Anti-biofilm activity of low-molecular weight chitosan hydrogel against Candida species. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2014;203(1):25–33.10.1007/s00430-013-0311-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[100] Gondim B, Castellano L, de Castro RD, Machado G, Carlo HL, Valenca AMG, et al. Effect of chitosan nanoparticles on the inhibition of Candida spp. biofilm on denture base surface. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;94:99–107.10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.07.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[101] Rashki S, Asgarpour K, Tarrahimofrad H, Hashemipour M, Ebrahimi MS, Fathizadeh H, et al. Chitosan-based nanoparticles against bacterial infections. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;251:117108.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[102] Rajabnia R, Ghasempour M, Gharekhani S, Gholamhoseinnia S, Soroorhomayoon S. Anti-Streptococcus mutans property of a chitosan: containing resin sealant. J Int Soc Prev Commun Dent. 2016;6(1):49–53.10.4103/2231-0762.175405Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[103] Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014;116(1):1–7.10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[104] Moghadamtousi SZ, Kadir HA, Hassandarvish P, Tajik H, Abubakar S, Zandi K. A review on antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activity of curcumin. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:186864.10.1155/2014/186864Search in Google Scholar

[105] Sodagar A, Bahador A, Pourhajibagher M, Ahmadi B, Baghaeian P. Effect of addition of curcumin nanoparticles on antimicrobial property and shear bond strength of orthodontic composite to bovine enamel. J Dent (Tehran). 2016;13(5):373–82.Search in Google Scholar

[106] Silva LM, Hill LE, Figueiredo E, Gomes CL. Delivery of phytochemicals of tropical fruit by-products using poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. 2014;165:362–70.10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.05.118Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] Esmaili Z, Bayrami S, Dorkoosh FA, Akbari Javar H, Seyedjafari E, Zargarian SS, et al. Development and characterization of electrosprayed nanoparticles for encapsulation of Curcumin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106(1):285–92.10.1002/jbm.a.36233Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[108] Ahmadi H, Haddadi-Asl V, Ghafari HA, Ghorbanzadeh R, Mazlum Y, Bahador A. Shear bond strength, adhesive remnant index, and anti-biofilm effects of a photoexcited modified orthodontic adhesive containing curcumin doped poly lactic-co-glycolic acid nanoparticles: an ex-vivo biofilm model of S. mutans on the enamel slab bonded brackets. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2020;30:101674.10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101674Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[109] Hadrup N, Loeschner K, Bergstrom A, Wilcks A, Gao X, Vogel U, et al. Subacute oral toxicity investigation of nanoparticulate and ionic silver in rats. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(4):543–51.10.1007/s00204-011-0759-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[110] Aeran H, Kumar V, Uniyal S, Tanwer P. Nanodentistry: Is just a fiction or future. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2015;5(3):207–11.10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[111] Kavoosi F, Modaresi F, Sanaei M, Rezaei Z. Medical and dental applications of nanomedicines. APMIS. 2018;126(10):795–803.10.1111/apm.12890Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[112] Patil M, Mehta DS, Guvva S. Future impact of nanotechnology on medicine and dentistry. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2008;12(2):34–40.10.4103/0972-124X.44088Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[113] Maman P, Nagpal M, Gilhotra RM, Aggarwal G. Nano era of dentistry-an update. Curr Drug Deliv. 2018;15(2):186–204.10.2174/1567201814666170825155201Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[114] Allaker RP. The use of nanoparticles to control oral biofilm formation. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1175–86.10.1177/0022034510377794Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[115] van der Kaaij N. Prevention of white spot lesion formation during treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2020;127(12):699–704.10.5177/ntvt.2020.12.20058Search in Google Scholar

[116] Salehi P, Babanouri N, Roein-Peikar M, Zare F. Long-term antimicrobial assessment of orthodontic brackets coated with nitrogen-doped titanium dioxide against Streptococcus mutans. Prog Orthod. 2018;19(1):35.10.1186/s40510-018-0236-ySearch in Google Scholar

[117] Ghasemi T, Arash V, Rabiee SM, Rajabni R, Pourzare A, Rakhshan V. Antimicrobial effect, frictional resistance, and surface roughness of stainless steel orthodontic brackets coated with nanofilms of silver and titanium oxide: a preliminary study. Microsc Res Tech. 2017;80(6):599–607.10.1002/jemt.22835Search in Google Scholar

[118] Zhang R, Zhang W, Bai X, Song X, Wang C, Gao X, et al. Report: discussion on the development of nano Ag/TiO2 coating bracket and its antibacterial property and biocompatibility in orthodontic treatment. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28(2 Suppl):807–10.Search in Google Scholar

[119] Gracco A, Dandrea M, Deflorian F, Zanella C, De Stefani A, Bruno G, et al. Application of a molybdenum and tungsten disulfide coating to improve tribological properties of orthodontic archwires. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2019;9(5):753.10.3390/nano9050753Search in Google Scholar

[120] Rapoport L, Leshchinsky V, Lapsker I, Volovik Y, Nepomnyashchy O, Lvovsky M, et al. Tribological properties of WS2 nanoparticles under mixed lubrication. Wear. 2003;255:785–93.10.1016/S0043-1648(03)00044-9Search in Google Scholar

[121] Cizaire L, Vacher B, Le Mogne T, Martin JM, Rapoport L, Margolin A, et al. Mechanisms of ultra-low friction by hollow inorganic fullerene-like MoS2 nanoparticles. Surf Coat Technol. 2002;160:282–7.10.1016/S0257-8972(02)00420-6Search in Google Scholar

[122] Friedman H, Eidelman O, Feldman Y. Fabrication of self-lubricating cobalt coatings on metal surfaces. Nanotech. 2007;18:115703.10.1088/0957-4484/18/11/115703Search in Google Scholar

[123] Mhaske AR, Shetty PC, Bhat NS, Ramachandra CS, Laxmikanth SM, Nagarahalli K, et al. Antiadherent and antibacterial properties of stainless steel and NiTi orthodontic wires coated with silver against Lactobacillus acidophilus – an in vitro study. Prog Orthod. 2015;16(1):40.10.1186/s40510-015-0110-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[124] Kachoei M, Nourian A, Divband B, Kachoei Z, Shirazi S. Zinc-oxide nanocoating for improvement of the antibacterial and frictional behavior of nickel-titanium alloy. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2016;11(19):2511–27.10.2217/nnm-2016-0171Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[125] Demling A, Heuer W, Elter C, Heidenblut T, Bach FW, Schwestka-Polly R, et al. Analysis of supra- and subgingival long-term biofilm formation on orthodontic bands. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31(2):202–6.10.1093/ejo/cjn090Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[126] Prabha RD, Kandasamy R, Sivaraman US, Nandkumar MA, Nair PD. Antibacterial nanosilver coated orthodontic bands with potential implications in dentistry. Ind J Med Res. 2016;144(4):580–6.Search in Google Scholar

[127] Gong SQ, Epasinghe J, Rueggeberg FA, Niu LN, Mettenberg D, Yiu CK, et al. An ORMOSIL-containing orthodontic acrylic resin with concomitant improvements in antimicrobial and fracture toughness properties. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42355.10.1371/journal.pone.0042355Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[128] Ghorbanzadeh R, Pourakbari B, Bahador A. Effects of baseplates of orthodontic appliances with in situ generated silver nanoparticles on cariogenic bacteria: a randomized, double-blind cross-over clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16(4):291–8.10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1678Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[129] Ma Y, Zhang N, Weir MD, Bai Y, Xu HHK. Novel multifunctional dental cement to prevent enamel demineralization near orthodontic brackets. J Dent. 2017;64:58–67.10.1016/j.jdent.2017.06.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed