Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

-

Pengfei Li

Abstract

Thermal protection system (TPS) is of great significance to launch hypersonic flight and landing process of hypersonic vehicles, which can effectively shield the hypersonic vehicle from severe aerodynamic heating encountered. Phenolic aerogels play an important role in TPS due to their characteristics of low density, high porosity, and low thermal conductivity. However, phenolic aerogel is easy to be oxidized at elevated temperatures under oxidizing environments, which severely limits its large-scale application as thermal insulation materials in TPS. In this study, a novel TiB2–B4C/carbon (TB/C) aerogel composite was synthesized by introducing TiB2 and B4C particles into phenolic aerogels through quick-gelation and mechanical mixing. The developed aerogel composites were characterized by scanning electron microscopy, Fourier transform infrared, thermal analysis, etc., to evaluate their microstructure, oxidation resistance, and mechanical properties. Experimental evidence showed that TiB2 and B4C particles reacted with the oxygen-containing molecules to form TiO2–B2O3 layer, which effectively improved oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of phenolic aerogel composites.

1 Introduction

Phenolic aerogels were widely used in hypersonic vehicles, civil structural edifices, and industrial architectures [1,2,3]. Incorporation of inorganic particles into a phenolic aerogel matrix can significantly improve mechanical, oxidation resistance, and fire retardancy of the organic–inorganic aerogel composites. However, phenolic aerogels are usually prepared via a week-long base-catalyzed gelation process, and deionized water or anhydrous ethanol is chosen as the solvent [4,5]. It is difficult to achieve well-dispersed inorganic particles in phenolic aerogels because of inorganic particle sedimentation due to gravity and incompatibility with precursor solution [6].

At present, there are two ways to modify the surface of inorganic particles by chemical treatments to increase the affinity of the inorganic particle surface for precursor solution [7,8]. The first one is accomplished through adding modified nanoparticles into polymer aerogels. Pulci et al. achieved surface modification of ZrO2 nanoparticles with several organic acids, demonstrating that the addition of nano-ZrO2 produces an improvement of both thermal and mechanical performance compared with pristine material [9]. The second method is using silane coupling agents to modify particle surfaces, thus improving the compatibility between the particle surfaces and precursor solution. Liu et al. used trimethoxy silane to modify halloysite nanotubes (m-HNTs) and introduced m-HNTs into the phenolic aerogel [10]. The obtained aerogel composite exhibited low carbonization shrinkage (30.83%) and enhanced residue yield (73.24%) at 1,000°C protected in N2 atmosphere.

Functional inorganic particles, such as B4C, TiB2, and ZrB2 particles, are generally considered as excellent candidates for thermal oxidation applications [11,12]. Compared with traditional inorganic particles, such as TiO2, ZrO2, SiO2, and Halloysite nanotubes, functional inorganic particles can react with oxygen-containing molecules to form oxides and increase the residue yield of composite during the oxidation process [13,14]. For example, TiB2 particles react with the oxygen-containing molecules to form B2O3 and TiO2 [15]. Besides, molten B2O3 cover the oxidized surface and form protective layer, which can effectively inhibit the oxidation of phenolic aerogel in the interior [16,17]. However, these functional inorganic particles are chemically inert and cannot be chemically treated to increase the compatibility of the particle surface for the solvent. For this reason, it is extremely difficult to efficiently introduce functional inorganic particles into phenolic aerogel.

In this work, a quick-gelation approach to achieve better dispersibility of TiB2 and B4C particles in the phenolic aerogel is reported. The gelation of resorcinol with formaldehyde could be remarkably accelerated by acid catalysis because the addition of formaldehyde is an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction [18,19,20,21]. In Table 1, this work is compared with other existing works. As can be seen from Table 1, this work has ultra-quick time of gelation. Thus, trifluoroacetic acid (CF3COOH) is used as a catalyst to accelerate gelation, which avoids the severe sedimentation of TiB2 and B4C particles over time in precursor solution. The oxidation of TiB2 and B4C particles at elevated temperatures could form a protective layer, which can effectively improve oxidation resistance and mechanical performance of aerogel composites. The introduction of TiB2 and B4C particles into phenolic aerogels in this study only requires simple mechanical mixing without complex chemical treatment, which is suitable for large-scale production.

Comparison of gelation time of phenolic aerogels

| Catalyst | Solvent | Molar ratio of R:F | Ratio of solvent catalyst | T (°C) | Gelation time | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2CO3 | H2O | 1:2 | 72.5a | 85 | >2 days | [16,17] |

| HCl | CH3CN | 1:2 | 21b | 80 | 10 min | [16] |

| CF3COOH | H2O | 1:3 | 20b | 35 | 15–30 s | This work |

R: Resorcinol; F: formaldehyde; a: the molar ratio of solvent: catalyst; b: the volume ratio of solvent:catalyst.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Formaldehyde (37.0 wt% aqueous solution, AR) and resorcinol (AR) were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Inc. Deionized water was supplied in our laboratory. CF3COOH was obtained from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. TiB2 and B4C particles (purity > 98%) with particle size of 1–10 μm, used as fillers, were provided by Aladdin Industrial Inc. All chemicals were used as-received with no further purification.

2.2 Preparation of TB/C aerogel composites

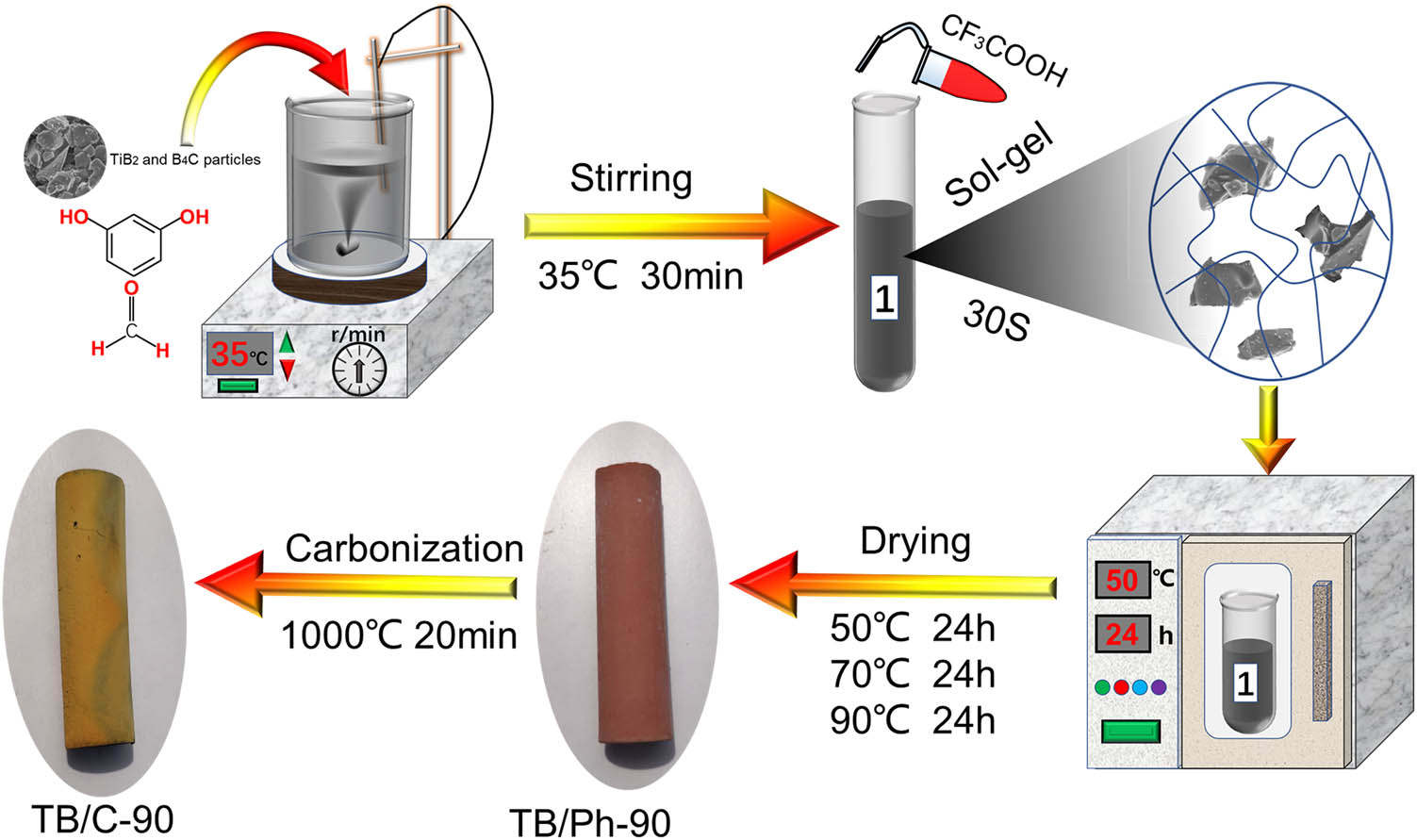

Figure 1 shows schematic illustration of the preparation process of TB/C aerogel composites. In this work, resorcinol, formaldehyde, and deionized water were referred to as R, F, and W, respectively. The molar ratios of F:R and W:R were maintained at 3:1 and 1:2, respectively. The weight ratio of TiB2:B4C was 1:1. According to the method, the precursor solutions, containing R, F, and W, were mixed by a magnetic stirrer at 35°C, and the solid content of the precursor solutions was recorded as 1. Suspension was manufactured by dissolving precursor solutions (solid content is 1) and 0, 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90% of filler (mixture of TiB2 and B4C) under vigorous stirring for 30 min, and then decanted into glass molds. Second, the appropriate amount of CF3COOH was dropped into glass molds. The volume ratio of suspension:CF3COOH was 20:1. The glass molds were sealed and placed into tube holder at room temperature for gelation to form hydrogels. Typically, the gel time is about 20–40 s and the aging time is 2 h. The obtained hydrogels were directly dried in an oven at 50°C for 24 h, 70°C for 24 h, and 90°C for 24 h to obtain aerogel composites. Finally, the samples were carbonized at 1,000°C for 20 min in muffle furnace. The uncarbonized phenolic (Ph) aerogel monomers were expressed as TB/Ph-x-y, and the carbon aerogel monomers were denoted as TB/C-x-y, where x refers to the content of TiB2 and B4C in TB/Ph-x-y, and y indicates carbonization temperature.

Schematic illustration for the preparation process of TB/C aerogel composites.

2.3 Characterization

The morphological microstructure of the samples was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; HitachiS-4800F) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. The groups of aerogel composites were characterized with Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra and recorded on a Nexus 670 FTIR spectrometer with KBr pellets in the wave number range of 4,000–500 cm−1. Thermal stability test of the aerogel composites was performed by a NETZSCH STA449F3 thermal analyzer. Compressive strength of the cylindrical samples (r × h: 10 mm × 20 mm) was measured by electronic universal testing machine with a testing speed of 1.0 mm min−1. The XRD patterns of the TB/C aerogel composites were measured by an X-ray diffractometer, Bruker D8 Advance Discover with CuKα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA). The thermal residue of TB/C aerogel composites was also characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Drying and carbonization shrinkages were calculated by measuring the diameter of each cylindrical sample before and after drying and carbonization, respectively. Densities were determined through dividing weight by volume. Thermal conductivity was determined by the Hot Disk thermal protection system (TPS) 2500 thermal constant analyzer at 25°C.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microstructure of TB/C aerogel composites

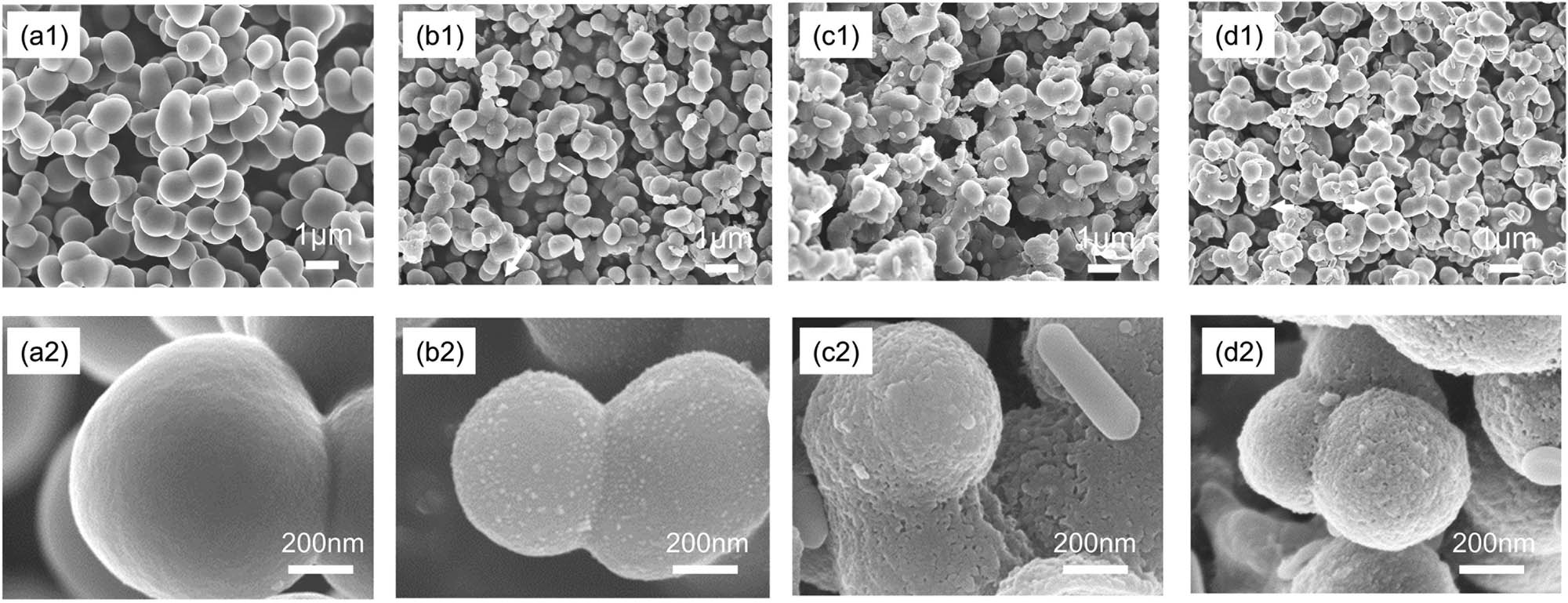

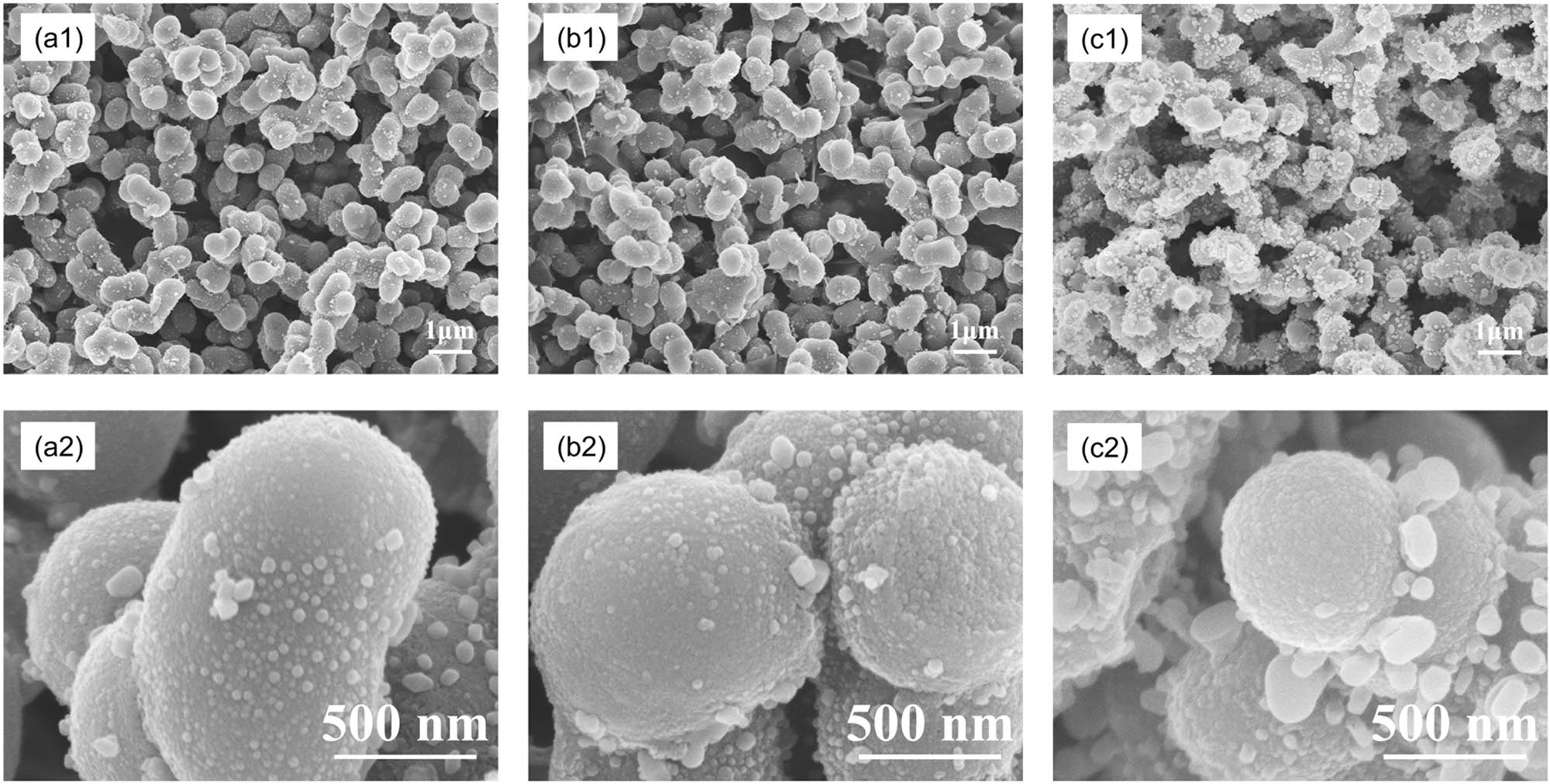

The microstructures of the TB/C aerogel composites with different TiB2 and B4C contents are shown in Figure 2. SEM images show that TB/C aerogel composites are basically composed of well-connected microspheres, which are connected through clear neck and randomly gather together to obtain “grape string” appearance. For pure carbon aerogel without TiB2 and B4C added (Figure 2a), the diameter of carbon microspheres is about 1 μm and its surface is smooth. The morphology of samples begins to change as TiB2 and B4C particles are introduced, and in Figure 2b and c, the B2O3 layers start to appear and the TiO2 grains are primitively generated. For TB/C-90 aerogel composites (Figure 2d2), the diameter of microspheres is about 620 nm.

(a)–(d) SEM images of TB/C aerogel composites with different TiB2 and B4C contents: (a1), (a2) 0; (b1), (b2) 10%; (c1), (c2) 50%; and (d1), (d2) 90%.

The FTIR spectra of the TB/Ph aerogel composites with different TiB2 and B4C contents are shown in Figure 3a. The TB/Ph aerogel composites exhibited typical adsorptions of Ph–OH at 3,410 cm−1 (stretching), CH2 stretching at 2,926 cm−1, C═C vibration of aromatic rings at 1,617 and 1,476 cm−1, Ph–O stretching vibrations of phenolic hydroxyl group at 1,220 cm−1, and C–O stretching vibrations of methylene ether bridges (CH2−O−CH2) at 1,090 cm−1. Bands at 1,015 cm−1 were ascribed to C–O stretching vibration of CH2OH. The TB/Ph aerogel composites exhibited absorption peak of the hydrogen bonds (OH···O) at 3,224 cm−1 (Figure 3c) [22,23,24]. Presumably, hydrogen bonds (OH···O) are generated by the residual non-hydrolyzed hydroxymethyl groups (CH2OH) and phenolic hydroxyl group (Ph-OH) [25]. As the content of TiB2 and B4C is increased, the intensity of the hydrogen bonds increases, indicating incorporation of more CH2OH and Ph–OH in the form of hydrogen bonds.

(a) FTIR spectra of TB/Ph aerogel composites, (b) methylene ether bridge index of TB/Ph aerogel composites, and (c) interactions of TB/Ph aerogel composites.

Peaks at 1,617 cm−1 were assigned to the C═C vibration of aromatic rings, which were consistent in each reaction system and unaffected by the content of TiB2 and B4C particles [26]. Thus, bands at 1,617 cm−1 could be used as a standard for analysis. The excessive formaldehyde (F/R = 3) allows the conjecture that most of the 2-, 4-, and 6-positions of the resorcinol aromatic rings react and form the corresponding hydroxymethyl derivatives. Thus, the molar ratio of methylene ether bridges (CH2−O−CH2) is much higher than that of methylene bridges (CH2) in aerogel composites. Based on the absorption intensities (A 1 and A 0) of the methylene ether bridges and phenyl groups (1,090 and 1,617 cm−1, respectively), we can calculate the methylene ether bridge index (I) of the TB/Ph aerogel composites by the following relationship: I = A 1/A 0. As shown in Figure 3b, it is apparent that the methylene ether bridge index decreases from 1.14 to 0.91 with the increased content of TiB2 and B4C, which was attributed to the added TiB2 and B4C particles hindering the motion of organic clusters and eventually partial CH2OH and Ph-OH had not participated in the sol–gel reaction. This can result in different thermal stability and compressive strength of TB/Ph aerogel composites due to fewer methylene ether bridges [27,28,29]. All these are consistent with the FTIR spectra, TG, and comprehensive strength analysis.

3.2 Oxidation resistance and thermal stability of TB/Ph aerogel composites

3.2.1 TG-DTG analysis

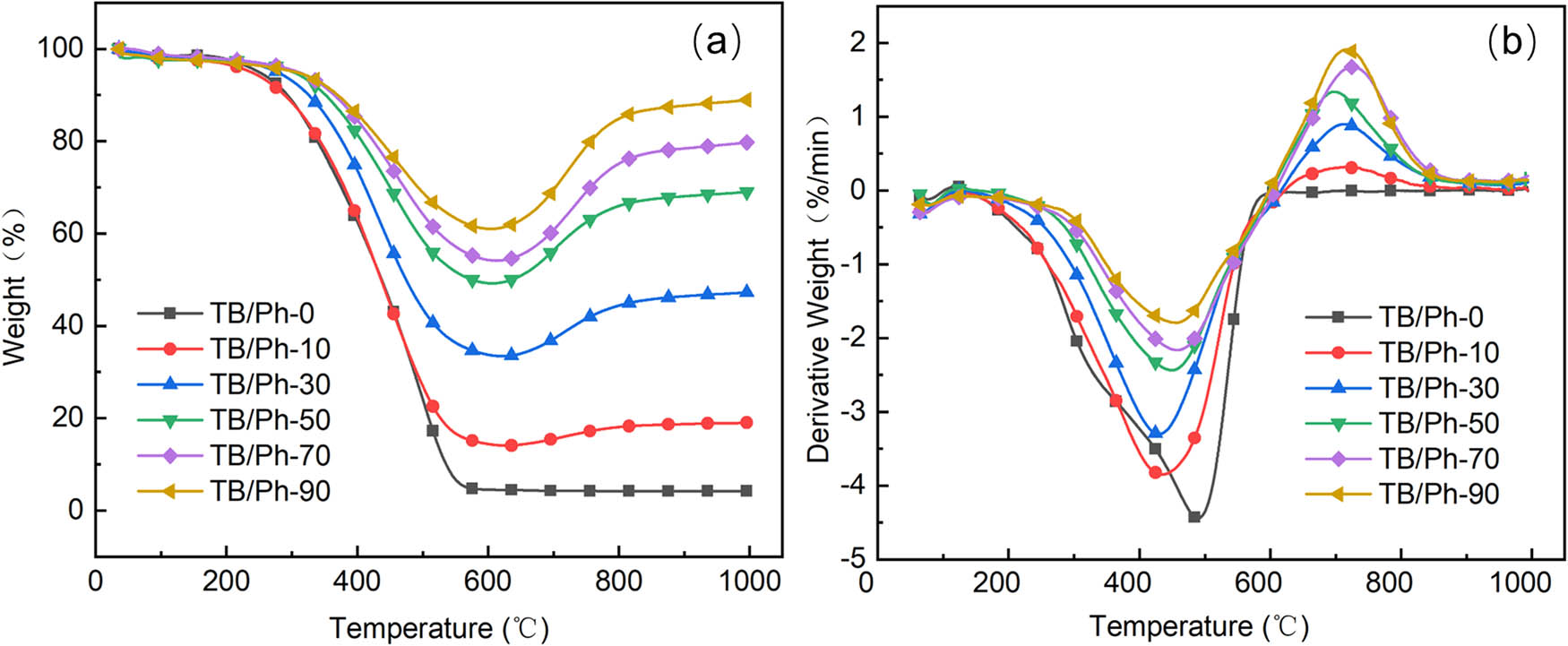

As shown in Figure 4b and Table 2, the temperature of the maximum degradation rates (T max1) for pure phenolic aerogel (494.4°C) are greater than that for TB/Ph aerogel composites. These results reveal that the thermal stability of aerogels is decreased clearly with the introduction of TiB2 and B4C particles by mechanical mixing. TiB2 and B4C particles will affect the condensation between hydroxymethyl derivatives of resorcinol and lead to a reduction in the number of methylene ether bridges (CH2−O−CH2). These are consistent with the FTIR spectra analysis. Moreover, with the increase in TiB2 and B4C particle content, T max1 increases slightly, as the formation of B2O3-protected structure will increase the T max1. This should be attributed to oxidation of partial B4C particles at temperatures below 500°C [30]. Interestingly, we discover that the residue yield of TB/Ph aerogel composites at high temperatures could be evidently increased by the presence of TiB2 and B4C particles. The residue yield of pure phenolic aerogel was 5.68%, while that of TB/Ph-90 hold was 90.01% at 1,000°C, indicating the outstanding oxidation resistance of TB/Ph aerogel composites.

(a) TG curves of samples at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 from room temperature to 1,000°C under air atmosphere; (b) DTG curves of samples at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 from room temperature to 1,000°C under air atmosphere.

Thermal decomposition characteristics of TB/Ph aerogel composites

| Samples | T max1/°C | T max2/°C | Residue yield% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300°C | 600°C | 1,000°C | |||

| TB/C-0 | 494.4 | / | 88.75 | 5.8 | 5.68 |

| TB/C-10 | 437.0 | 717.3 | 88.04 | 16.51 | 21.45 |

| TB/C-30 | 429.7 | 712.6 | 92.55 | 35.37 | 49.25 |

| TB/C-50 | 458.3 | 706.6 | 95.29 | 51.01 | 70.83 |

| TB/C-70 | 455.8 | 724.7 | 95.10 | 54.02 | 79.83 |

| TB/C-90 | 455.8 | 716.5 | 95.03 | 61.97 | 90.01 |

T max1: temperature of the maximum degradation rate. T max2: temperature of the maximum mass gain rate.

As shown in Figure 4a and Table 2, the degradation processes of TB/Ph aerogel composites both can be divided into three stages [31]. Take the TB/Ph-90 for example, the first stage with little mass loss (<5%) is from room temperature to 300°C, and the mass loss of the samples is mainly due to the evaporation of the free water in the aerogels. When the temperature reaches 600°C, severe mass loss is observed in the TG curves. With the pyrolysis of phenolic aerogels, many kinds of pyrolysis volatiles including H2O, CO, CO2, H2, CH4, and other derivates are released out [32,33]. The oxygen-containing molecules, including CO, O2, CO2, and H2O, take a large proportion in the number of volatiles, and provide a source of oxidizing atmosphere. In the step of 600–1,000°C, the residue yield of the TB/Ph aerogel composites increased continuously with the increased content of TiB2 and B4C particles, which means that some weight gain reactions between TiB2 and B4C particles and oxygen-containing molecules should have occurred. As listed in Table 2, the residue yield of TB/Ph-90 aerogel composites increased from 61.97 to 90.01%, when temperature was increased from 600 to 1,000°C. Some main gain reactions are given as follows:

3.2.2 EDS, XRD, and XPS analyses

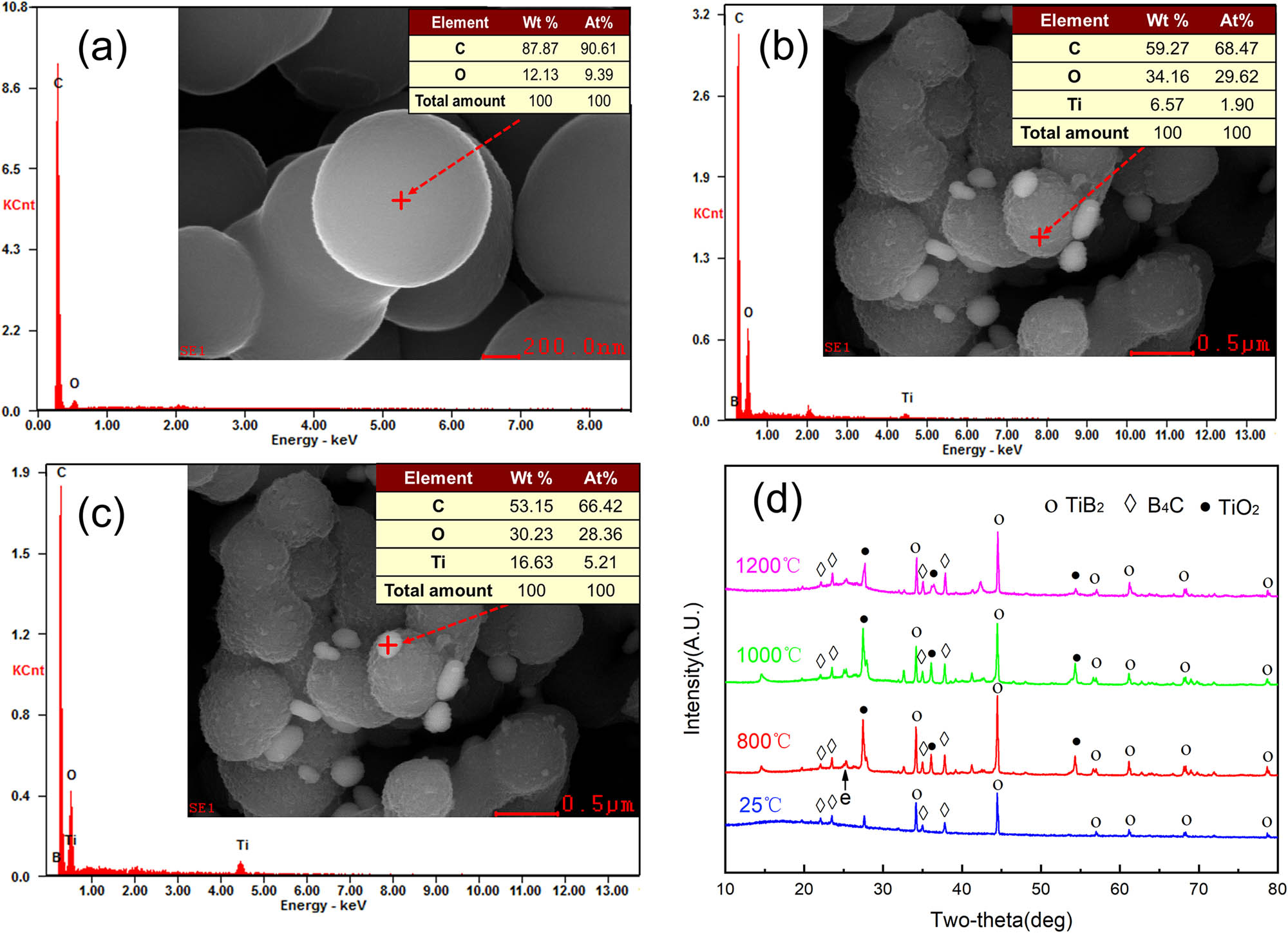

To further verify the occurrence of the weight gain reactions, EDS and XRD analyses are employed. As shown in Figure 5a, only the C and O elements are detected on the surface of carbon microspheres without TiB2 and B4C. As shown in Figure 5c, the molar ratio of oxygen and titanium in white spot is approximately equal to 5.38, while the molar ratio of TiO2 is 2. These results implied that new substance was formed and coated on the surface of carbon microspheres. Figure 5d shows the XRD patterns of the residues for TB/C-30 aerogel composites at 25–1,200°C. There are TiB2 and B4C diffraction peaks in the non-carbonized aerogel samples. The diffraction peak of TiO2 can be evidently detected at 800°C, which confirms the oxidation of TiB2. Besides, broad peak e observed at 2θ angles of about 25° is the characteristic peak of amorphous carbon.

EDS analysis of aerogel composites: (a) TB/C-0; (b and c) TB/C-30; (d) XRD pattern of the TB/C-30 aerogel composites. wt%: mass fraction, At%: atomic fraction.

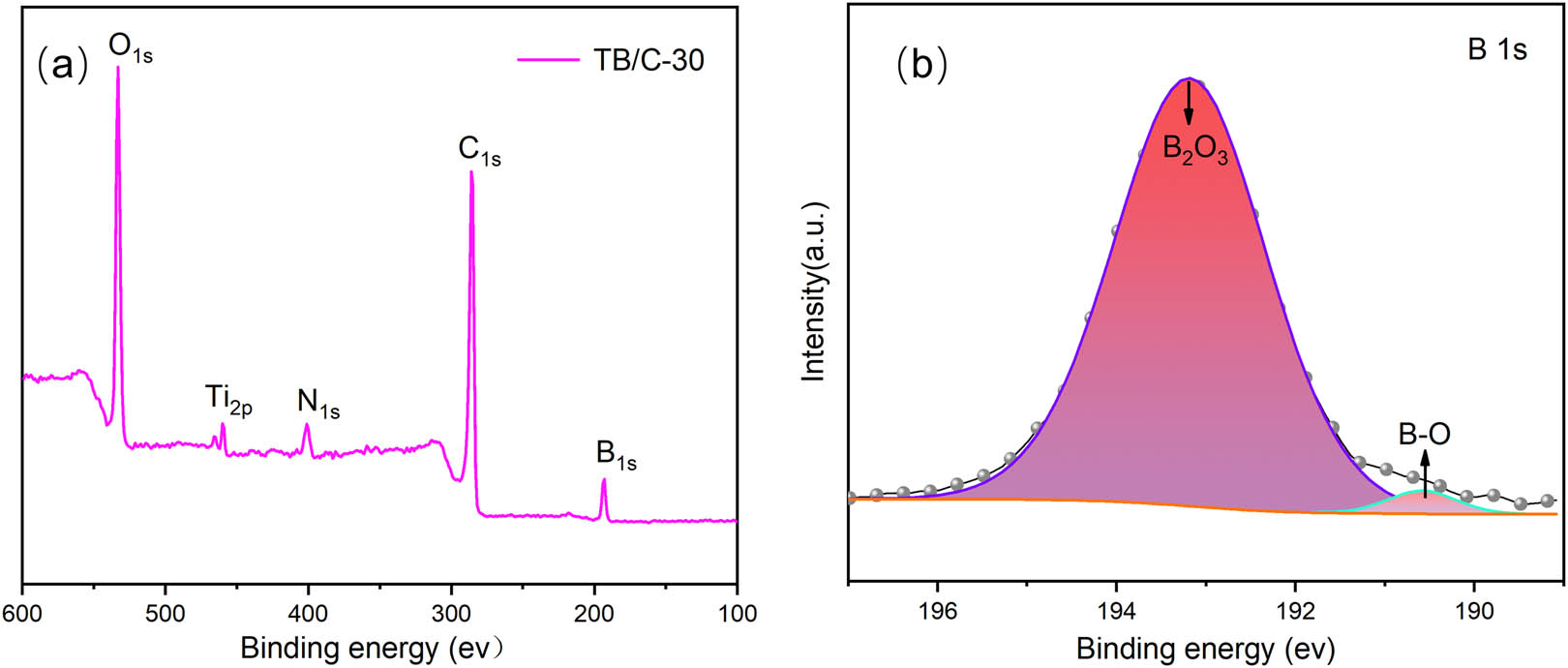

The oxygen, titanium, nitrogen, carbon, and boron elements are detected from the full-scan XPS spectrum of the thermal residues (Figure 6a). The high-resolution B1s XPS spectrum for the thermal residues (Figure 6b) shows a prominent peak at 193.28 eV, usually assigned to the contribution of B2O3, and the peak detected at energy (190.38 eV) corresponds to the B–O binding [34]. The diffraction peaks of B2O3 are not detected by XRD due to its amorphous form in the aerogel network, which has flowability at high temperature (melting point is 450°C) [35,36,37]. The glassy B2O3 could cover the surface of the carbon aerogel by forming a continuous protective film and improving the oxidation resistance of composites.

XPS spectra of TB/C-30 aerogel composites: (a) a full-scan and (b) B1s.

3.2.3 Microstructure of TB/C aerogel composites at different carbonization temperatures

Figure 7 illustrates the microstructure transformation of TB/C aerogel composites at different carbonization temperatures. As shown in Figure 7a2, the TB/C-30-800 exhibits typical aerogel network with overlapping structure, and the TiO2 grains are randomly dispersive and coated on the surface of aerogel nanospheres. The presence of B2O3 can densify the surface of aerogel nanospheres and form a protective barrier against high-temperature oxidation. As the carbonization temperature reaches to 1,200°C, the aerogel composites maintain a stable porous nanostructure and form bigger TiO2 grains with the size of 100 nm (Figure 7c2).

(a)–(c) SEM images of TB/C-30 aerogel composites at different carbonization temperatures: (a1), (a2) 800°C; (b1), (b2) 1,000°C; and (c1), (c2) 1,200°C.

3.3 Mechanical and thermal insulation properties

As shown in Figure 8a, densities of TB/Ph aerogel composites increase remarkably from 0.379 to 0.582 g cm−3 with the increased content of TiB2 and B4C. This should be attributed to the introduction of TiB2 (4.52 g cm−3) and B4C (2.52 g cm−3) particles [38]. The density of the TB/C-90 aerogel composites increases slightly from 0.582 to 0.647 g cm−3, majorly due to some weight gain reactions during the carbonization process. Figure 8b presents the compressive strength of samples. The lowest compressive strength of TB/Ph aerogel composites is shown by TB/Ph-90, which also should be attributed to the introduction of TiB2 and B4C in aerogels. The increase of TiB2 and B4C particles will affect the sol–gel polymerization of organic clusters and eventually weaken the network skeleton of TB/Ph aerogel composites [39,40,41], which is consistent with the FTIR spectra. Interestingly, it is apparent that the compressive strength of the TB/C aerogel composites first increased from 0.62 to 1.94 MPa and then decreased from 1.94 to 1.06 MPa with a further increase in TiB2 and B4C contents (Figure 8b). This should be attributed to the formation of protective structure, which can reduce the pyrolysis of phenolic aerogel matrix and retain its strength. However, TiO2 grains and glassy B2O3 are not assembled into a solid unified structure due to the short carbonization time (only 20 min). Therefore, with the increase of TiB2 and B4C contents, the compressive strength will still show a downward trend, which is similar to the compressive performance trend of uncarbonized aerogels.

(a) Density of samples and (b) comprehensive strength of samples.

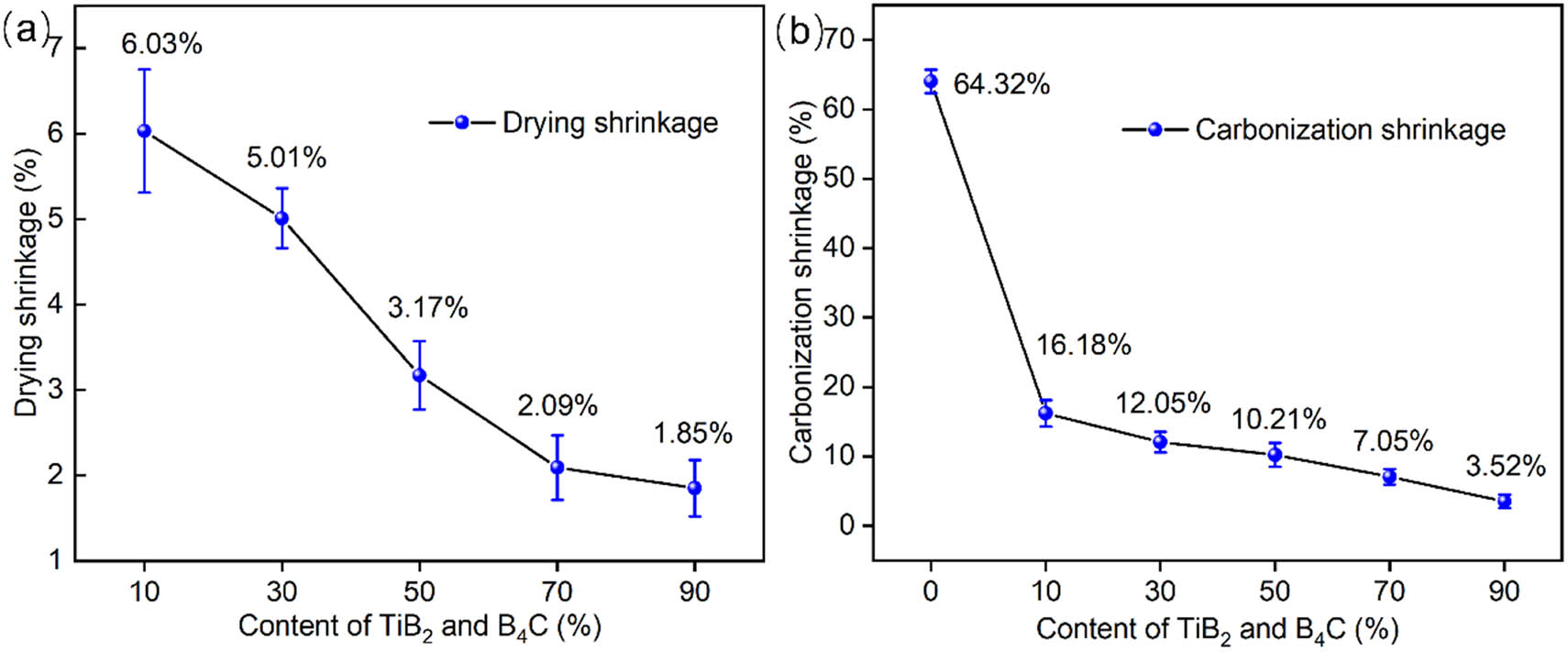

As displayed in Figure 9a, the drying shrinkage dropped remarkably from 6.03 to 1.85% with the rise of TiB2 and B4C contents. This phenomenon can be explained by particle enhancement. With the increase of TiB2 and B4C contents, TB/Ph aerogel composites can more effectively against shrinkage due to the huge capillary force generated during ambient pressure drying. Figure 9b illustrates the change of carbonization shrinkage from TB/Ph to TB/C aerogel composites during carbonization process. The carbonization shrinkage decreases dramatically from 16.18 to 3.52% when changing the content of TiB2 and B4C from 10 to 90%, revealing that the introduction of TiB2 and B4C particles can effectively restrain the oxidation and improve mechanical properties of composites due to the formation of TiO2–B2O3 layer.

(a) Drying shrinkage of samples and (b) carbonization shrinkage of samples.

The thermal conductivities of TB/Ph and TB/C aerogel composites were measured at 25°C, and the results are shown in Figure 10a. Typically, the total thermal conductivity includes solid conductivity, gas conductivity, convection transmission, and radiation transmission [42], which can be schematically illustrated in Figure 10b. As the content of TiB2 and B4C particles increases, the thermal conductivities of TB/C aerogel composites gradually increase from 0.054 to 0.081 W m−1 K−1 at 25°C. On the one hand, the solid phase thermal conductivity increases ascribed to the high thermal conductivity of TiB2 and B4C (about 60–120 W m−1 K−1) [43]. On the other hand, the aggregation of particles is beneficial to solid-phase thermal conductivity, which will provide more solid-phase thermal transport pathways with the increase in density of the composites. When the content of TiB2 and B4C is 90%, the thermal conductivity of TB/Ph-90 aerogel composites is 0.081 W m−1 K−1, which increased by 70% compared with those of pure phenolic aerogels (0.048 W m−1 K−1).

(a) Thermal conductivity curves at 25°C of aerogel composites; (b) schematics illustrating thermal transport pathways.

During carbonization process, the TiB2 and B4C particles gradually transform to TiO2 grains and glassy B2O3 by oxidation reaction, which will fill the gap of aerogel microspheres and further improve the solid-phase thermal conductivity of TB/C aerogel composites. When the content of TiB2 and B4C is 90%, the thermal conductivity of TB/C-90 aerogel composites is 0.188 W m−1 K−1, which increased by 132.11% compared with TB/C-90 aerogel composites (0.081 W m−1 K−1). However, due to the porous structures, the heat transfers of gaseous thermal conduction and convection in TB/C aerogel composites are inhibited effectively.

4 Conclusion

By adjusting the content of TiB2 and B4C particles, a novel TB/C aerogel composite was fabricated via the sol–gel polymerization followed by ambient pressure drying and carbonization. During carbonization process, the TiB2 and B4C particles gradually transform to TiO2 grains and glassy B2O3 layer by oxidation reduction reaction, which densify the surface of aerogel nanospheres and form a protective barrier. The resulting TB/C aerogel composites exhibited low densities between 0.331 and 0.647 g cm−3, relatively high compressive strength, ranging from 0.62 to 1.94 MPa, and low thermal conductivities of 0.097–0.188 W m−1 K−1 at room temperature. When the content of TiB2 and B4C was 90%, the residue yield of aerogel composites was 90.01% at 1,000°C in air, which increased by 84.33% compared with that of phenolic aerogels. Therefore, this work provides a significant way to improve the oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TB/Ph aerogel composites, and it may be useful for thermal structure in TPS, such as hypersonic vehicles and civil industrial architectures.

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by the Joint Fund of Ministry of Education for Equipment Pre-research (6141A02022250).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] He H, Geng L, Liu F, Ma B, Huang W, Qu L, et al. Facile preparation of a phenolic aerogel with excellent flexibility for thermal insulation. Eur Polym J. 2022;163:110905.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110905Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jia X, Dai B, Zhu Z, Wang J, Qiao W, Long D, et al. Strong and machinable carbon aerogel monoliths with low thermal conductivity prepared via ambient pressure drying. Carbon. 2016;108:551–60.10.1016/j.carbon.2016.07.060Search in Google Scholar

[3] Balaji A, Udhayasankar R, Karthikeyan B, Swaminathan J, Purushothaman R. Mechanical and thermal characterization of bagasse fiber/coconut shell particle hybrid biocomposites reinforced with cardanol resin. Results Chem. 2020;2:100056.10.1016/j.rechem.2020.100056Search in Google Scholar

[4] Yang Z, Li J, Xu X, Pang S, Hu C, Guo P, et al. Synthesis of monolithic carbon aerogels with high mechanical strength via ambient pressure drying without solvent exchange. J Mater Sci & Technol. 2020;50:66–74.10.1016/j.jmst.2020.02.013Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wang Y, Wang S, Bian C, Zhong Y, Jing X. Effect of chemical structure and cross-link density on the heat resistance of phenolic resin. Polym Degrad Stab. 2015;111:239–46.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.11.016Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wang C, Cheng H, Hong C, Zhang X, Zeng T. Lightweight chopped carbon fibre reinforced silica-phenolic resin aerogel nanocomposite: Facile preparation, properties and application to thermal protection. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2018;112:81–90.10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.05.026Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kango S, Kalia S, Celli A, Njuguna J, Habibi Y, Kumar R. Surface modification of inorganic nanoparticles for development of organic–inorganic nanocomposites–A review. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38(8):1232–61.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.02.003Search in Google Scholar

[8] Prabhu P, Karthikeyan B, Vannan RR, Balaji A. Dynamic mechanical analysis of Silk and Glass (S/G/S)/Pineapple and Glass (P/G/P)/Flax and Glass (F/G/F) reinforced Lannea coromandelica blender hybrid nano composites. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15:2484–96.10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.09.068Search in Google Scholar

[9] Pulci G, Paglia L, Genova V, Bartuli C, Valente T, Marra F. Low density ablative materials modified by nanoparticles addition: Manufacturing and characterization. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2018;109:330–7.10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.03.025Search in Google Scholar

[10] Liu H, Wang P, Zhang B, Li H, Li J, Li Y, et al. Enhanced thermal shrinkage behavior of phenolic-derived carbon aerogel-reinforced by HNTs with superior compressive strength performance. Ceram Int. 2021;47(5):6487–95.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.10.232Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ding J, Huang Z, Qin Y, Shi M, Huang C, Mao J. Improved ablation resistance of carbon–phenolic composites by introducing zirconium silicide particles. Compos Part B: Eng. 2015;82:100–7.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.08.023Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wang S, Huang H, Tian Y, Huang J. Effects of SiC content on mechanical, thermal and ablative properties of carbon/phenolic composites. Ceram Int. 2020;46(10, Part B):16151–6.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.03.170Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wu K, Zhou Q, Cao J, Qian Z, Niu B, Long D. Ultrahigh-strength carbon aerogels for high temperature thermal insulation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;609:667–75.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.11.067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Hou X, Zhang R, Fang D. An ultralight silica-modified ZrO2–SiO2 aerogel composite with ultra-low thermal conductivity and enhanced mechanical strength. Scr Materialia. 2018;143:113–6.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2017.09.028Search in Google Scholar

[15] Cao X, Wang B, Ma X, Feng L, Shen X, Wang C. Oxidation behavior of melt-infiltrated SiC–TiB2 ceramic composites at 500–1300°C in air. Ceram Int. 2021;47(7, Part A):9881–7.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.12.130Search in Google Scholar

[16] Chen Y, Chen P, Hong C, Zhang B, Hui D. Improved ablation resistance of carbon–phenolic composites by introducing zirconium diboride particles. Compos Part B: Eng. 2013;47:320–5.10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.11.007Search in Google Scholar

[17] Amirsardari Z, Mehdinavaz Aghdam R, Salavati-Niasari M, Shakhesi S. Enhanced thermal resistance of GO/C/phenolic nanocomposite by introducing ZrB2 nanoparticles. Compos Part B: Eng. 2015;76:174–9.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.01.011Search in Google Scholar

[18] Mulik S, Sotiriou-Leventis C, Leventis N. Time-efficient acid-catalyzed synthesis of resorcinol−formaldehyde aerogels. Chem Mater. 2007;19(25):6138–44.10.1021/cm071572mSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Zhang Z, Zhao S, Chen G, Feng J, Feng J, Yang Z. Influence of acid-base catalysis on the textural and thermal properties of carbon aerogel monoliths. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;296:109997.10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.109997Search in Google Scholar

[20] Singh KP, Palmese GR. Enhancement of phenolic polymer properties by use of ethylene glycol as diluent. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;91(5):3096–106.10.1002/app.13439Search in Google Scholar

[21] Paulraj P, Balakrishnan K, Rajendran RRMV, Alagappan B. Investigation on recent research of mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced polymer (NFRP) materials. Materiale Plastice. 2021;58(2):100–18.10.37358/MP.21.2.5482Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hashimoto M, Tajima F, Yamamura K. Tetrameric O–H⋯O hydrogen-bond systems accompanied by C–H⋯O hydrogen-bonds in the crystal of 1,4-bis(hydroxymethyl)triptycene: An X-ray study. J Mol Structure. 2002;616(1):129–34.10.1016/S0022-2860(02)00319-8Search in Google Scholar

[23] Böger T, Sanchez-Ferrer A, Richter K. Hydroxymethylated resorcinol (HMR) primer to improve the performance of wood-adhesive bonds – A review. Int J Adhes Adhesives. 2022;113:103070.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2021.103070Search in Google Scholar

[24] Monk JD, Bucholz EW, Boghozian T, Deshpande S, Schieber J, Bauschlicher CW, et al. Computational and experimental study of phenolic resins: Thermal–mechanical properties and the role of hydrogen bonding. Macromolecules. 2015;48(20):7670–80.10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01183Search in Google Scholar

[25] Guo M, Pitet LM, Wyss HM, Vos M, Dankers PYW, Meijer EW. Tough stimuli-responsive supramolecular hydrogels with hydrogen-bonding network junctions. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(19):6969–77.10.1021/ja500205vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Yi Z, Zhang J, Zhang S, Gao Q, Li J, Zhang W. Synthesis and mechanism of metal-mediated polymerization of phenolic resins. Polymers. 2016;8(5):159.10.3390/polym8050159Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Giannetti E. Thermal stability and bond dissociation energy of fluorinated polymers: A critical evaluation. J Fluor Chem. 2005;126(4):623–30.10.1016/j.jfluchem.2005.01.008Search in Google Scholar

[28] Furer VL, Vandyukov AE, Khamatgalimov AR, Kleshnina SR, Solovieva SE, Antipin IS, et al. Investigation of hydrogen bonding in p-sulfonatocalix[4]arene and its thermal stability by vibrational spectroscopy. J Mol Structure. 2019;1195:403–10.10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[29] An X, Jing B, Li Q. Regulating function of alkali metal on the strength of OH⋯O hydrogen bond in phenol–water complex: Weak to strong and strong to weak. Comput Theor Chem. 2011;966(1):278–83.10.1016/j.comptc.2011.03.023Search in Google Scholar

[30] Kılıçarslan A, Toptan F, Kerti I, Piskin S. Oxidation of boron carbide particles at low temperatures. Mater Lett. 2014;128:224–6.10.1016/j.matlet.2014.04.138Search in Google Scholar

[31] Asaro L, D’Amico DA, Alvarez VA, Rodriguez ES, Manfredi LB. Impact of different nanoparticles on the thermal degradation kinetics of phenolic resin nanocomposites. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;128(3):1463–78.10.1007/s10973-017-6103-0Search in Google Scholar

[32] Wang J, Jiang H, Jiang N. Study on the pyrolysis of phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin and modified PF resin. Thermochim Acta. 2009;496(1):136–42.10.1016/j.tca.2009.07.012Search in Google Scholar

[33] Deng Z, Yue J, Huang Z. Solvothermal degradation and reuse of carbon fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2021;221:109011.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109011Search in Google Scholar

[34] Wang S, Wang Y, Bian C, Zhong Y, Jing X. The thermal stability and pyrolysis mechanism of boron-containing phenolic resins: The effect of phenyl borates on the char formation. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;331:519–29.10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.01.062Search in Google Scholar

[35] Li B, Deng J, Li Y. Oxidation behavior and mechanical properties degradation of hot-pressed Al2O3/ZrB2/ZrO2 ceramic composites. Int J Refractory Met Hard Mater. 2009;27(4):747–53.10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2008.12.006Search in Google Scholar

[36] Brach M, Sciti D, Balbo A, Bellosi A. Short-term oxidation of a ternary composite in the system AlN–SiC–ZrB2. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2005;25(10):1771–80.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2004.12.007Search in Google Scholar

[37] Guo W-M, Zhang G-J, Kan Y-M, Wang P-L. Oxidation of ZrB2 powder in the temperature range of 650–800°C. J Alloy Compd. 2009;471(1):502–6.10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.04.006Search in Google Scholar

[38] Song Q, Zhang Z-H. Microstructure and self-healing mechanism of B4C– TiB2– SiC composite ceramic after pre-oxidation behaviour. Ceram Int. 2022;48(17):25458–64.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.05.223Search in Google Scholar

[39] Fu S-Y, Feng X-Q, Lauke B, Mai Y-W. Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate–polymer composites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2008;39(6):933–61.10.1016/j.compositesb.2008.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[40] Feng J, Venna SR, Hopkinson DP. Interactions at the interface of polymer matrix-filler particle composites. Polymer. 2016;103:189–95.10.1016/j.polymer.2016.09.059Search in Google Scholar

[41] Pérez E, Alvarez V, Pérez CJ, Bernal C. A comparative study of the effect of different rigid fillers on the fracture and failure behavior of polypropylene based composites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2013;52:72–83.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.03.035Search in Google Scholar

[42] Wang G, Zhao J, Wang G, Mark LH, Park CB, Zhao G. Low-density and structure-tunable microcellular PMMA foams with improved thermal-insulation and compressive mechanical properties. Eur Polym J. 2017;95:382–93.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.08.025Search in Google Scholar

[43] Vajdi M, Sadegh Moghanlou F, Nekahi S, Ahmadi Z, Motallebzadeh A, Jafarzadeh H, et al. Role of graphene nano-platelets on thermal conductivity and microstructure of TiB2–SiC ceramics. Ceram Int. 2020;46(13):21775–83.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.05.289Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Pengfei Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review