Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

-

Atif Mahmood

, Essam A. Al-Ammar

and Dongwhi Choi

Abstract

High voltage (HV) outdoor insulators are subjected to both electrical and environmental stresses, which may lead to their failure. Among the causes, corona discharge, humidity and UV radiation are considered to be the most damaging factors. Efforts are therefore underway to investigate new materials for improving the performance of insulating systems. In this research work, silicone-based room temperature vulcanized samples filled with alumina trihydrate (ATH), silicon dioxide and magnesium hydroxide (MH) were prepared and exposed to AC corona discharge for a duration of 110 h. The electric discharge was also accompanied by UV radiation and two different humidity levels. Following aging of the test samples, diagnosis was conducted to assess their integrity. Measurements based on determining the static contact angle demonstrated the loss of hydrophobicity of all the materials, while hydrophobicity recovery phenomena revealed that ATH-doped materials demonstrated a comparatively higher increase in the contact angle than in samples filled with silicone dioxide (silica) and MH. Scanning electron microscopy analysis revealed deep cracks and block-like structures on their surfaces. Similarly, energy-dispersive X-ray analysis indicated the signs of surface oxidation of the aged samples. However, the data of elemental composition exhibited the loss of filler contents as well as that of carbon from the base matrix. The overall assessment showed that resistance to suppress aging is influenced by both the filler type and its concentration in the investigated composites. The ATH-filled composites exhibited outstanding performance when exposed to the rigors of corona discharge and other environmental stresses. This research contributes to materials science and HV engineering by addressing the development of composites for enhanced insulator performance, with future aspects lying in the utilization of nano-composites for advanced functionality and durability.

1 Introduction

Outdoor insulators are used in the overhead transmission and distribution lines to mechanically support the line conductors and electrically insulate them from the grounded towers. This necessitates that mechanical strength-to-weight ratio, thermal conductivity and breakdown strength of the insulator should be high apart from the low maintenance cost [1]. These properties of materials can be enhanced using different types of fillers, surface treatments and modification in material properties using different strategies [2,3,4]. Moreover, use of certain fillers and treatment methods improve materials’ thermal properties, hydrophobicity and friction coefficient [5,6]. Rubber polymers are employed as insulating materials in high voltage (HV) transmission, the recycling of which are of major importance [7]. Silicone rubber (SIR) is used as an insulator, and these rubber materials have created new opportunities for operating at higher voltages due to their superior hydrophobicity, increased mechanical strength, less maintenance needs and high dielectric strength [8]. Hydrophobicity of SIR is a key characteristic that sets it apart from ceramic and glass insulators and contributes to its better pollution flashover performance [9]. Moreover, its ability to recover hydrophobicity, which is considered as one of the most important characteristics, gives it preference over other polymers. The reason behind it is the migration of pre-existing low molecular weight (LMW) polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) from the bulk of the material to the degraded surface. This transfer (of LMW) can take place even if the insulator surface is polluted, and due to this advantage, SIR-based insulators are used in highly contaminated areas as well. Moreover, the hydrophobic nature of SIR prevents the development of leakage current, which subsequently inhibits surface flashover [10,11,12]. SIR is a solid insulating material, but there are liquids as well as gaseous materials that provide better insulating properties [13,14].

SIR insulators due to their organic structure are prone to aging and degradation when exposed to electrical and environmental stresses [15,16,17]. A strong electrical field may cause dry-band arcing (DBA) and corona discharge. The loss of hydrophobicity enhances the flow of leakage current which leads to DBA, and eventually to the eroding of insulator’s surface [18]. Similarly, corona discharge due to a locally enhanced electric field is considered as another potential threat to the performance of SIR insulators. The gaseous (NO and NO2) byproducts of corona discharge may combine with the moisture contents to form HNO3, which may be damaging to both the core and the shed material. Moreover, corona discharge also produces ozone gas as well as if it takes place in the vicinity of an insulator it may deposit electrons/ions on its surface [19,20]. The latter has been found to affect the electric field distribution and flashover performance of the insulator [21]. The inescapable and gradual process of aging is inevitably triggered by prolonged and continuous exposure to elevated levels of electric field intensity, high UV radiation, increased humidity, substantial pollution and the presence of various external environmental factors [22,23,24].

Significant work has been done to study the impact of fillers on the performance enhancement of insulating materials under the impact of corona exposure. In the study of Nazir et al. [25], the effectiveness of SIR materials filled with various concentrations of micro-/nanosized silica was assessed in order to determine the most suitable formulation to prevent both the corona discharge and loss of hydrophobicity. Results of the measurements showed that the test sample filled with 5 wt% nano-silica has the higher resistance to corona discharge than the others without any filler as well as those filled with micro- and micro-/nanosilica. Silica fillers not only provide better insulating behavior but also are used to improve resistance against different types of radiation [26]. Nazir et al. used micro-alumina trihydrate (ATH) and nano-alumina for enhancing the properties of SIR against corona discharge. The conducted analysis indicated that addition of a small amount of nano-alumina to the micro-ATH-filled sample significantly improved its performance [27]. In one study, authors used micro-/nanosized silica fillers, and they found that the ability to suppress corona discharge was found to be more for the co-filled composite containing 2 wt% nano-silica and 10 wt% micro-silica as compared to the other formulations [28]. Similarly, hydrophobicity loss and recovery phenomena were studied on SIR samples filled with aluminum hydroxide and fumed silica after being exposed to corona discharge. The authors found that loss of hydrophobicity on a clean surface was more than that on the contaminated surface. Moreover, the hydrophobicity recovery of clean and contaminated surfaces after being exposed to corona was fast returning to the initial value of contact angle just after 24 h of recovery time [29]. In a more recent work, authors studied the impact of humidity, heat and corona discharges on the surface of ATH-filled insulators. They found that due to the synergistic effect of aging the morphology of composites was distorted, precipitation of fillers also occurred and deeper surface cracks were noticed. Infrared spectroscopy shows continuous breakdown of polymer chains. Micro-cavities result from SiR and ATH decomposition, reducing hydrophobicity, increasing moisture absorption, and causing abnormal heating [30].

The efforts made by various researchers have demonstrated, for instance, that corona discharge when combined with the environmental stresses (humidity, acid fog, or vertical wind) have synergistic effects in speeding up the breakdown of insulators [31,32,33]. However, the reported data are not ample, particularly the severity of degradation due to corona discharge under UV radiation and relatively high humidity is not studied at length. Accounting for this gap, long term (110 h) AC corona discharge aging of SIR materials reinforced with different concentrations of micro-sized ATH, silica and magnesium hydroxide (MH) fillers was conducted in a specially designed chamber. The experimental setup was also equipped with arrangements for UV radiation and humidity. For the latter, two levels (medium and relatively high) were considered. After performing the aging, test samples were assessed for various properties to describe the insulation characteristics, with particular emphasis on understanding hydrophobicity recovery phenomena using contact angle measurement. The other diagnostic tools employed included scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometry to analyze the surface morphology and elemental composition, respectively. The results of various tests were demonstrated, discussed and compared to identify the most suitable composition among the investigated formulations to retard the process of aging due to the synergetic impact of electrical and environmental stresses.

2 Materials and tests

2.1 Composite preparation

RTV-615A (RTV = room temperature vulcanized) with a density of 1.15 g/m3 was used as the base material. It contained 70% of PDMS and 30% of vinyl compound. Three types of fillers, silica, ATH and MH, were used for reinforcement of the base polymer. The different tools/equipment used in preparation process of test samples are shown in Figure 1, and the procedure is described as follows. In the first step, filler particles were stirred for 15 min in a 100 ml solution of ethanol, followed by ultrasonication for 30 min to achieve proper de-agglomeration. Then, RTV-615A was added to the filler, and blending was performed using an HSM-100 LSK high-shear blender for 15 min. Following that step, the curing agent (RTV-615B) was added to the mixture, and it was stirred again for 15 more minutes. The part-A to part-B ratio was kept at 10:1. Moreover, to remove any entrapped air, the prepared mixture was placed in a vacuum desiccator for 10 min. Following that, molding was done to get the required shape and size of the test sample. The shape was flat, while dimensions selected were of two types. One was 75 mm × 40 mm × 3 mm and the other was 120 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm. Finally, to complete the vulcanization process, a pressure of 30 MPa was applied using a hydraulic press for 30 min, and then postcuring was performed in an oven at a temperature of 85°C for the next 4 h. The list of prepared room temperature vulcanized silicone rubber (RTV-SiR) composites is given in Table 1.

(a) Schematic view and (b) photographic representation of the corona discharge setup. Needle-plane electrodes for aging the test samples are shown. Also, arrangements for UV irradiation and humidity are shown.

Specifications of the studied SIR materials reinforced with different concentrations of ATH, silica and MH fillers

| Sample notation | RTV-SIR (wt%) | Filler specifications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Particle size (µm) | Specific gravity (g/cm3) | wt% | ||

| A50 | 50 | ATH | 1.7 | 2.40 | 50 |

| S50 | 50 | Silica | 1.1 | 2.65 | 50 |

| M50 | 50 | MH | 1.1 | 2.40 | 50 |

| A40 | 60 | ATH | 1.7 | 2.40 | 40 |

| S40 | 60 | Silica | 1.1 | 2.65 | 40 |

| M40 | 60 | MH | 1.1 | 2.40 | 40 |

2.2 Corona discharge setup

Specifications of the studied RTV-SIR materials reinforced with different concentrations of micro-sized particles of silica, ATH and MH are provided in Table 1. Samples of materials were prepared in a rectangular shape having a length, width and thickness of 120 mm, 50 mm and 5 mm, respectively, and exposed to AC corona discharge using a needle-plane electrode arrangement, as shown in Figure 1. The whole setup was housed in a stainless-steel chamber, where a regulated gaseous environment was provided to minimize possible ozone impact on the conducted measurements. The needle electrode with a tip diameter of 2 mm served as a corona source. The test sample was placed on the bottom electrode, which was grounded. The schematic and pictorial views of the corona discharge setup are shown in Figure 1, and the procedure for corona discharge is described as follows. Six single needle-plane identical electrodes connected to a 16 kVA transformer were used to expose the test samples to corona discharge. The applied voltage was adjusted with the help of a variac (regulating transformer).

The voltage value was measured through a HV probe, which was further connected to an oscilloscope for displaying the data. The scale-down ratio of the probe was 1,000:1. Corona discharge was created at two different electric field strengths by adjusting the gap distance between the tip of the needle electrode and the sample’s surface as 1 and 5 mm. Moreover, to incorporate the effect of UV radiation, UVA-340 lamps were used. However, for controlling the humidity level, a humidifier equipped with a sensor, display and controller was placed inside the chamber. Experiments were performed at two different relative humidity levels, medium (55–65%) and high (75–85%). Also, to check the variation of results, measurements were repeated at least three times.

2.3 Hydrophobicity loss and recovery analysis

It is crucial to assess the hydrophobicity of insulating materials as it reduces with the aging process. Numerous techniques, including the water immersion technique; sliding angle, dynamic contact angle, and static contact angle measurement; and the Swedish Transmission Research Institute scale can be used to quantitatively evaluate the hydrophobicity loss and recovery. Among these, the most popular method is the measurement of static contact angle, which is present at the point where a liquid drop meets a material surface. The following Young–Dupré equation is used to link the contact angle with the surface energy of the solid and surface tension of the liquid materials:

where

Due to the high surface energy and ease of wetting, hydrophilic materials allow water droplets to touch more surface area, and the contact angle ultimately decreases from 90°. Hydrophobic materials, on the other hand, have low surface energies that prevent water droplets from flowing along their surfaces, causing the contact angle to be greater than 90° [34].

In the present study, a micropipette was used to put a drop of 20 µl size to measure the contact angle of SIR materials. Following corona aging of the test sample, a droplet of de-ionized water was placed on its surface, and a snapshot was captured through a high-resolution camera, which was further uploaded to a computer. “ImageJ” software having low-bond axisymmetric drop shape analysis plugin was used to find the static contact angle of the droplet [35]. Moreover, to assess hydrophobicity recovery of the aged samples, measurements were taken at different time intervals. The recorded data were also compared with that of the unaged (virgin) materials.

2.4 SEM and EDX analyses

SEM is a diagnostic technique used for assessing surface topography in order to evaluate the morphology of materials under study. Moreover, it is also used to identify any changes on the surface of the treated/aged sample. In the test procedure, to create SEM micrographs, a high-energy beam of electrons scans the sample in a raster scanning pattern. In order to produce signals that contain information about the sample’s surface topography and composition, the beam of electrons interact with the atoms of samples on the surface. In the present study, an FEI Quanta FEG-250 ESEM machine, which was also equipped with an EDX detector, was used to generate high-quality SEM micrographs to assess the morphology of the sample as well as to measure the compositions of elements on its surface. For comparative analysis, SEM images were taken both for the unaged and corona aged SIR materials.

3 Results of diagnostic measurements

3.1 Loss of hydrophobicity

Contact angles were measured both prior to and postcorona discharge aging of the test samples. The collected data under different studied scenarios are shown in Tables 2 and 3. As seen in both the tables, the contact angle of untreated (unaged) samples is greater than 90°, showing their good hydrophobicity. However, due to the long time (110 h) exposure of test samples to corona discharge and other stresses (humidity and UV radiation), their hydrophobicity reduces (contact angles are lower than those of the unaged materials). This observation is the same, irrespective of the reinforcement of samples with the type and concentration of fillers. Nevertheless, the decrease in contact angle due to aging is different for the SIR materials, which is dependent on their composition. It is lower for ATH-doped samples A50 and A40 as compared to their silica and MH-filled counterparts, respectively, reflecting better hydrophobicity of the former than the latter. The performed measurements also indicate the effects of UV radiation, humidity and electric field stress (different at 1 and 5 mm gap distances). For example, the loss under high humidity is more than that under medium humidity. Moreover, by adding UV radiation, the impact becomes stronger. As far as the effect of varying gap distance is concerned, higher loss can be noticed at 1 mm as compared to that at 5 mm.

Measured contact angle of the test samples before and immediately after their corona aging

| Samples | Unaged | High humidity (with UV) | High humidity (without UV) | Medium humidity (with UV) | Medium humidity (without UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A50 | 95.6° | 20.2° | 21.7° | 21.6° | 22.4° |

| S50 | 93.8° | 13.7° | 14.9° | 20.8° | 23.4° |

| M50 | 95.3° | 15.8° | 16.4° | 16.1° | 22.8° |

Data recorded at medium and relatively high humidity levels as well as with and without UV radiations are shown.

Measured contact angle of the studied SIR materials before and immediately after their corona aging at 1 mm and 5 mm gap distances between the needle electrode and sample’s surface

| Samples | Unaged | 5 mm (with UV) | 5 mm (without UV) | 1 mm (with UV) | 1 mm (without UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A40 | 92.1° | 32.8° | 35.9° | 26.3° | 27.9° |

| S40 | 97.0° | 24.4° | 30.2° | 23.3° | 23.7° |

| M40 | 99.5° | 22.9° | 28.6° | 22.1° | 23.1° |

3.2 Hydrophobicity recovery

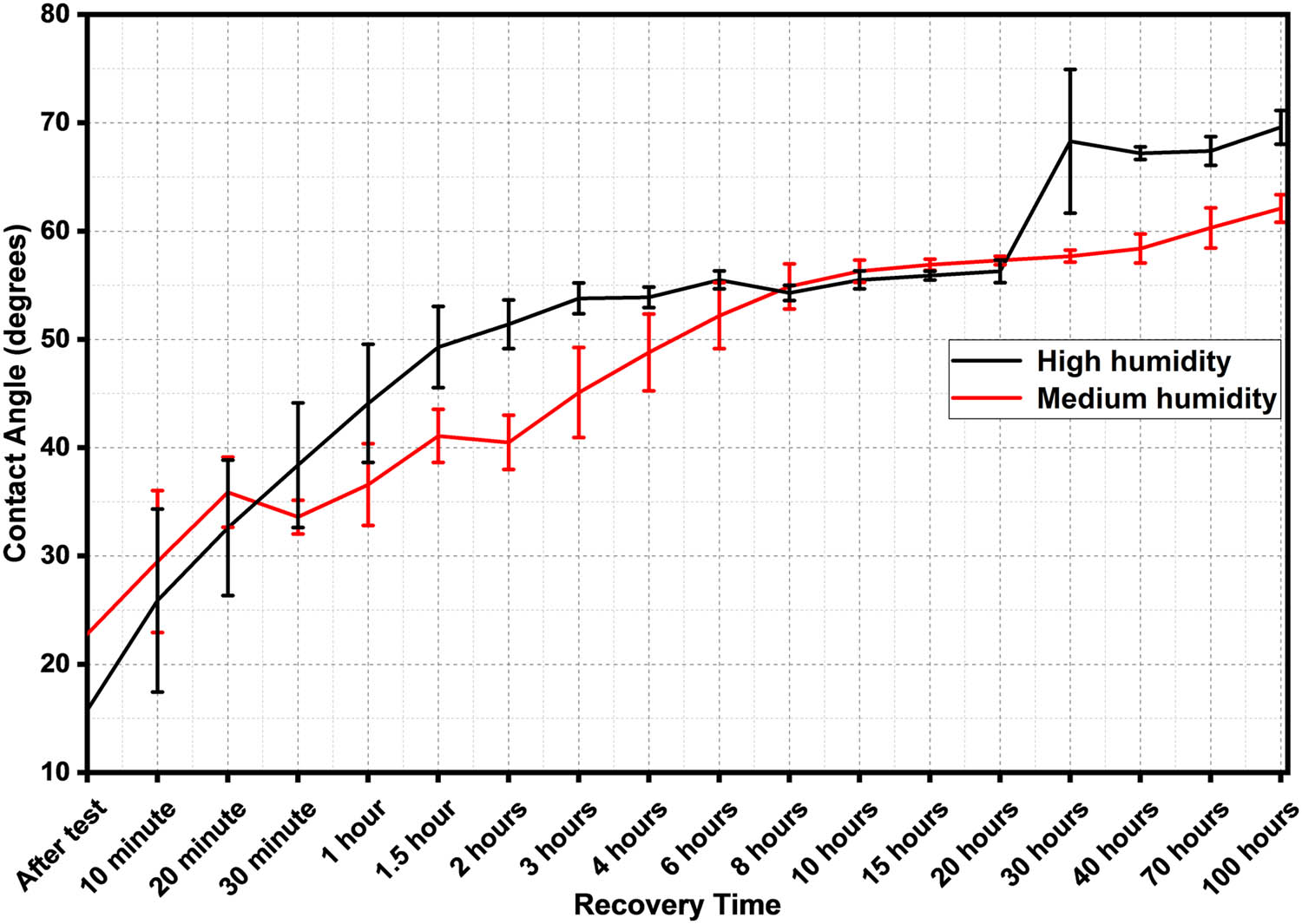

Hydrophobicity recovery is one of the desired properties of SIR insulators, and to analyze the factors behind it, an in-depth study was performed in the current research. For this purpose, contact angles of the unaged and corona aged SIR materials were measured using the procedure described in Section 2.2. Collected data of the test samples exposed to corona discharge under relatively high humidity (75–85%) and UV radiation containing 50 and 40 wt% concentrations of the studied fillers are shown in Figure 2(a) and (b), respectively. As is seen, contact angles of the test samples recorded through the first (immediately after aging) and the last measurements (at 100 h) are different. The latter values are higher than the earlier ones, reflecting the hydrophobicity recovery phenomenon. Moreover, analyzing the recovery rate through slopes of the lines, one can observe that, in general, it is higher for SIR materials reinforced with 40 wt% of fillers as compared to their 50 wt% doped counterparts, particularly at the beginning. Similarly, for samples S40 and M40, the final mean values (of angles) of 72.3° and 70.7°, respectively, are also more than those of S50 and M50, which are 69.7° and 65.6°, respectively. The only exception is that of A40 and A50, where for the latter an angle of 75.7° was recorded, while for the earlier, it was measured as 74.5°. To analyze the impact of varying humidity levels (during corona discharge under UV radiation) on the hydrophobicity recovery rate, the contact angle vs recovery time graph of sample A50 (filled with 50 wt% of micro-sized ATH) is shown in Figure 3. As is seen, both the initial and final values as well as slopes of the curves in various time intervals are different under medium (55–65%) and relatively high humidity (75–85%) levels. For instance, in the beginning, the recovery rate shown by the black and red lines is quite similar, although mean values of angles are higher under medium humidity as compared to the high humidity. On the other hand, later on, opposite tendency/behavior is noticeable. Both the slope of the curve and contact angle become higher under the humidity level of 75–85% than that of 55–65%. The presented data thus infer that hydrophobicity loss increases when corona discharge is accompanied by high humidity (as is also summarized in Table 2); however, under the same conditions, the recovery phenomenon after certain time duration is also the fastest.

Hydrophobicity recovery of the corona aged SIR materials under high relative humidity (75–85%) and UV radiation. Sub-figures (a) and (b) show measurements for the samples containing 50 and 40 wt% concentrations of the studied fillers, respectively.

Hydrophobicity recovery of the test sample A50 exposed to corona discharge under UV radiation at 1 mm gap distance and at two different humidity levels.

In addition to the varying humidity level, the effect imposed by the UV radiation together with the corona discharge was also assessed on the studied SIR materials. One such example is shown in Figure 4, where data for the ATH-doped test sample A40 are presented. For comparative analysis, measurements taken without applying any UV radiation are also displayed. As is seen, there is a clear difference between the two curves and remains almost consistent throughout the length of the data recording time, indicating that both the hydrophobicity loss and its recovery rate are adversely affected when corona discharge is accompanied by UV radiation.

Hydrophobicity recovery of the SIR material A40 aged under high humidity at 1 mm gap distance. Data recorded both with and without UV radiation are displayed.

To examine how the strength of the electric field stress influences the contact angle as well as its increase (recovery) after corona discharge, data were recorded at 1 and 5 mm gap distances between the needle tip and the sample’s surface. For illustration, measurements performed on SIR material M40 reinforced with 40 wt% of micro-sized MH filler are shown in Figure 5. It is worth highlighting here that corona discharge aging was realized under UV radiation and high humidity to create the worst impact. As is seen, by increasing the electric field stress through reducing the gap distance, the effect becomes stronger. Thus, contact angles throughout the duration of measurement are high (showing high hydrophobicity) when the sample is stressed at 5 mm as compared to 1 mm. However, the slopes of the curves, representing the hydrophobicity recovery rate, are nearly the same.

Hydrophobicity recovery of SIR material M40 aged under UV radiation and high humidity. Data recorded at 1 and 5 mm gap distances between the sample and the needle electrode are shown.

In Figure 6, two curves of the test sample doped separately with 40 and 50 wt% concentrations of the MH filler are shown. Corona discharge treatment was done at 1 mm gap distance and under UV radiation and high humidity to see how the severity of this worst condition is reduced by varying the filler concentration. By analyzing the curves, it can be inferred that apart from the high contact angles in the entire time window, the recovery rate is also fast for the sample M40 compared to that of SiR M50, particularly, at the beginning. Thus, reinforcement of the base material with the optimal concentration of filler is important for achieving desired results. Moreover, it is concluded from the analysis of data in this section that corona discharge treatment of the test samples accompanied by environmental and electrical stresses adversely affect their hydrophobicity as the contact angle did not reach 90° in any of the studied scenario in the whole recorded time.

Hydrophobicity recovery of corona exposed SIR materials M40 and M50. Aging is performed under high humidity and UV radiation and at 1 mm gap distance.

3.3 SEM analysis

SEM micrographs of the corona aged SIR materials were obtained using the procedure outlined in Section 2.3. The collected data were analyzed under different studied scenarios to assess/compare the effects of various stresses/environmental factors (electric field, UV radiation and humidity) on the severity of surface degradation. SEM images of unaged samples are presented in Figure 7. However, Figure 8 depicts the surface morphology of ATH, silica and MH-doped samples A50, S50 and M50, respectively, which were aged under an HV electrode through corona discharge at 1 mm gap distance. Effects of UV radiation as well as those of the medium and high humidity levels were also incorporated. As is seen, the synergetic impact of these stresses affects the surface conditions, even though the severity is different being dependent on the material’s composition. For the test sample A50, surface cracks and fissures can be observed which become deeper when the humidity level is increased (compare images in Figure 8(a) and (b)). A similar tendency is also indicated in Figure 9(d) and (e), where the results of SIR material M50 are displayed. Nevertheless, surface degradation/roughness of the ATH-filled sample is less pronounced as compared to its MH-filled counterpart. The relatively strongest effect is demonstrated in Figure 8(e) for material M50. For the silica-doped material S50, its SEM micrograph is provided in Figure 8(c), in which signs of surface deterioration are also noticeable, though they are much weaker than those in Figure 8(e).

SEM micrographs of unaged composites: (a) A40, (b) S40, (c) M40, (d) A50, (e) S50 and (f) M50.

SEM micrographs of the studied composites aged under corona discharge at 1 mm gap distance and under UV radiation. Sub-figures (a) and (b) represent data of sample A50 under high and medium humidity levels, respectively, (c) displays the image of sample S50 under high humidity and (d) and (e) show images of sample M50.

(a) Image of the corona aged SiR material M40 at 5 mm gap distance and under UV radiation. (b) and (c) SEM micrographs of the test sample M40 at 1 mm gap distance and without and with UV radiation, respectively. (d) and (e) Data of samples S40 and A40 at 1 mm gap distance and under UV radiation. The humidity level in all these scenarios was kept high (75–85%).

To examine the impact of electric field strength, which was varied through changing the gap distance, on the surface degradation, SEM images of SIR materials reinforced with 40 wt% concentration of the studied fillers are presented in Figure 9. Effects with and without UV radiation and by keeping high humidity level were also assessed. A comparison of the sub-figures shows that by applying the extreme/worst conditions (UV radiation and adjusting the gap distance at 1 mm which gives a strong electric field), more surface roughness in the form of deep cracks, block-like structures and even spots of white powder are created, resulting in the highest loss of hydrophobicity.

This is illustrated in Figure 9(c) for the ATH-doped material A40. However, the data (of the same sample and at the same electric field) recorded without UV radiation show comparatively much lower surface degradation, as is evident from Figure 9(b). On the other hand, if the electric field is reduced (by increasing the gap distance to 5 mm) while keeping UV radiation, no significant change occurs. This can be observed from the comparison of images in Figure 9(a) and (c). For other studied materials S40 and M40, SEM micrographs are provided in Figure 9(d) and (e), respectively, which also exhibit signs of surface roughness (shallow cracks and even white spots), although weaker as compared to sample A40. It is thus concluded from the analysis of data in this section that corona discharge when accompanied by UV radiation imposes a stronger impact than other stresses/environmental factors (electric field and humidity).

3.4 EDX analysis

To identify changes in the elemental composition of the investigated materials, EDX analysis was performed both prior to and post corona aging tests. Results of the measurements are presented in Table 4, where percentage values (of the constituents) of the samples reinforced with 50 wt% concentration of ATH, silica and MH fillers are listed. It is important to highlight here that the major elements constituting the studied composites are silicone (Si), oxygen (O), carbon (C), aluminum (Al) and magnesium (Mg). As is seen, corona discharge treatment affects constituents of the samples including both the fillers and other components, and its intensity increases by combining other stresses/factors with it. For example, the SIR material A50 shows a decrease of both Al (ATH filler) and C. In the case of Al (ATH filler) the percentage drops from 16.38 to 11.69 when effects of UV radiation and high humidity are also incorporated. The percentage of other elements (O and Si), however, increases beyond the level measured in the unaged conditions of the sample. Similarly, by analyzing the data of SIR S50 (containing silica as a filler), similar tendency can be observed, particularly related to the percentage drop of C. The quantity of Si is also reducing, although weakly as compared to C. As far as the MH-filled sample M50 is concerned, the percentage decrease of Mg (filler) is much higher than those of silica and ATH.

Elemental composition of the studied SIR materials aged under corona discharge at 1 mm distance between the needle tip and the sample surface

| A50 | % C | % O | % Al | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 20.91 | 38.96 | 16.38 | 23.74 |

| Without UV, high humidity | 18.35 | 43.15 | 14.30 | 24.20 |

| With UV, high humidity | 16.16 | 47.59 | 11.69 | 24.56 |

| Without UV, medium humidity | 18.05 | 43.11 | 14.78 | 24.06 |

| With UV, medium humidity | 16.20 | 47.22 | 11.83 | 24.75 |

| S50 | % C | % O | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 24.67 | 31.99 | 43.34 |

| Without UV, high humidity | 12.25 | 45.26 | 42.49 |

| With UV, high humidity | 8.26 | 54.30 | 39.44 |

| Without UV, medium humidity | 11.63 | 46.16 | 42.21 |

| With UV, medium humidity | 8.73 | 53.30 | 37.97 |

| M50 | % C | % O | % Mg | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 23.65 | 32.32 | 17.16 | 26.87 |

| Without UV, high humidity | 22.98 | 37.96 | 11.62 | 27.44 |

| With UV, high humidity | 17.52 | 43.77 | 8.79 | 29.92 |

| Without UV, medium humidity | 23.11 | 36.21 | 13.19 | 27.49 |

| With UV, medium humidity | 17.67 | 43.50 | 9.19 | 29.64 |

Moreover, the loss of carbon content was higher in the case of UV and high humidity. However, O and Si like material A50 show their increase.

To analyze the effect of changing the gap distance in corona discharge tests on the elemental composition of the studied materials, measurements are shown in Table 5. Data were collected while keeping humidity at a relatively high level (75 to 85%). As is seen, varying the electric field strength does create an impact. For example, by reducing the gap distance (giving a higher field), samples lose both fillers and carbon, irrespective of their composition. Moreover, upon worsening the conditions (applying UV radiation and a strong electric field), the percentage of constituents (fillers and carbon) drop further. On the other hand, in assessing the effect on O and Si, similar results as presented in Table 4 can be seen. Thus, their percentage increase by increasing the severity of the synergetic impact of electrical and environmental stresses.

Elemental composition of the corona aged test samples under high humidity (75 to 85%)

| A40 | % C | % O | % Al | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 23.20 | 32.92 | 13.28 | 30.60 |

| 5 mm, without UV | 22.56 | 33.25 | 12.22 | 31.97 |

| 5 mm, with UV | 19.97 | 37.06 | 10.17 | 32.80 |

| 1 mm, without UV | 17.15 | 38.77 | 10.38 | 33.70 |

| 1 mm, with UV | 18.47 | 40.25 | 9.42 | 34.86 |

| S40 | % C | % O | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 26.56 | 39.61 | 33.83 |

| 5 mm, without UV | 24.22 | 43.31 | 32.47 |

| 5 mm, with UV | 20.42 | 47.27 | 32.31 |

| 1 mm, without UV | 23.59 | 46.87 | 29.54 |

| 1 mm, with UV | 19.75 | 51.27 | 28.98 |

| M40 | % C | % O | % Mg | % Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 22.10 | 31.36 | 15.84 | 30.70 |

| 5 mm, without UV | 18.24 | 35.34 | 13.57 | 31.85 |

| 5 mm, with UV | 16.61 | 38.83 | 12.22 | 32.34 |

| 1 mm, without UV | 15.46 | 39.48 | 11.41 | 33.65 |

| 1 mm, with UV | 14.92 | 40.71 | 9.39 | 34.98 |

3.5 Discussion

To elaborate/identify possible reasons associated with the important/noticeable findings of various diagnostic measurements, the following discussion is presented. Analysis of the contact angle through which hydrophobicity was determined showed that (immediately after corona discharge aging) ATH-doped samples (A40 and A50) have higher values than their silica and MH-filled counterparts. Moreover, it was found to be affected by the UV radiation, humidity and electric field strength. As far as hydrophobicity recovery (increase in the contact angle with time) is concerned, it was observed to be higher in the initial duration of diagnosis and lower later on, irrespective of the composition of samples. Materials reinforced with a relatively high concentration (50 wt%) of the studied fillers showed comparatively slow recovery. This may be linked with the agglomeration phenomenon, which suppresses the movement/diffusion of LMW from the bulk of material toward its surface. Transfer of LMW, if takes place effectively, enhances the ability of materials to recover their surface characteristics/properties (including hydrophobicity) after being exposed to aging though applying various stresses. Apart from this (movement of LWM), hydrophobicity recovery phenomenon is also attributed to the polar group reorientation and condensation of silanol groups [18]. Quantifying the impact of individual stresses on hydrophobicity recovery, UV radiation was identified as the major (most damaging) factor. Nevertheless, the effect of increasing electric field strength (reducing gap distance) and humidity level was also noticed.

Assessment of the elemental composition of the test samples showed an increase in the oxygen content due to the oxidation process on their surfaces. This increase causes the formation of a hydrophilic layer that resembles silica and polar silanol groups on the PDMS (base matrix in the studied materials) surface, resulting in the loss of its hydrophobicity. The latter was observed to be higher when corona discharge treatment was intensified by adjusting the lower gap distance (between the needle tip and sample’s surface) as well as by applying UV radiation and high humidity. The reason behind the synergetic impact of these stresses, according to the mechanism outlined in the study of Hillborg and Gedde [36], is the strong oxidation process, which causes the transformation of the hydrophobic –CH3 group to the –CH2 group. Moreover, it produces hydroxyl (Si–CH2OH) and peroxides (Si–CH2OOH) due to the reaction between oxygen contents and PDMS. Apart from O, an increase in the silicone contents on the surface of materials was also noticed, which can be attributed to the movement of LMWs. However, for samples S40 and S50 (filler was silica, which comprised both silicone and oxygen), no significant change was recorded, and its interpretation is rather complex due to the difficulty in distinguishing between the movement of LMWs and lowering of the filler content. Opposite to the behavior of O and Si, decreasing percentage of both C and filler was observed, representing a loss of the other desired properties such as electrical and mechanical properties [37].

SEM micrographs, depending on the severity of aging, exhibited deep cracks, pits, block-like structures and even spots of white powder. The development of surface cracks may provide a low resisting route/path to the diffusion of LMW constituents, thus contributing to the higher rate of increasing contact angle (fast hydrophobicity recovery). To increase the recovery rate through cracking the hydrophilic layer on the surface, formed due to aging, Hillborg and Gedde suggested a modest mechanical stress [38]. It was also hypothesized in another research work that corona-induced deformation of the PDMS surface starts the angle recovery process at a faster rate [39].

4 Conclusions

This study focuses on improving certain properties of insulator composites utilizing the concept of materials sciences and providing better materials for HV insulation systems. The effect of the corona discharge accompanied by UV radiation and two humidity levels (medium and high) was analyzed on six different types of SIR materials filled with micro-sized particles of ATH, silica and MH. The duration of the test sample’s treatment was kept as 110 h. Following aging, different tools were employed for diagnosis, particularly to examine hydrophobicity recovery phenomena. The results of performed measurements, carried out immediately after the aging process of samples, exhibited a noticeable decrease of their contact angle. Moreover, the recovery of hydrophobicity on ATH-doped materials was observed at a relatively higher rate as compared to the silica and MH-filled samples. SEM micrographs and other assessments demonstrated the strongest impact of UV radiation among the investigated stresses/factors. Similarly, analysis of the elemental composition revealed the loss/gain of major constituents of the test samples, affecting adversely both their surface characteristics and other desired properties. The overall assessment showed that selection of the optimal weight percentage ratio of the base matrix and filler particles is important for achieving desired results. This research provides foundational insights into improving the insulator composite performance utilizing filler contents with higher concentrations. Future studies could explore hybrid composites having both micro and small concentrations of nano-sized particles to increase the lifespan of insulation systems. Investigating the synergistic impacts of micro- and nano-fillers under multiple stress conditions could completely transform the fabrication technique of futuristic insulating materials for HV insulation systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan, for providing the funds for one year research work. The authors are also thankful to Professor Ayman El-Hag and the University of Waterloo, Canada, for providing the equipment required for this research work and also work space in the high voltage laboratory. This work was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R492), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1C1C1008831).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Higher Education Commission and GIK Institute under the grant number 119FEG2004. This work was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R492), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Atif Mahmood: writing – original draft preparation, conceptualization. Ahmed Muneeb: methodology, supervision. Usman Saeed: software, visualization. Shahid Alam: validation, formal analysis. Essam A. Al-Ammar: investigation, data curation. Jee-Hyun Kang: resources, data curation. Wail Al Zoubi: writing – review and editing, funding acquisition. Dongwhi Choi: supervision, project administration. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Cheng L, Mei H, Wang L, Guan Z, Zhang F. Research on aging evaluation and remaining lifespan prediction of composite insulators in high temperature and humidity regions. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2016 Oct;23(5):2850–7.10.1109/TDEI.2016.7736845Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wang J, Pan Z, Wang Y, Wang L, Su L, Cuiuri D, et al. Evolution of crystallographic orientation, precipitation, phase transformation and mechanical properties realized by enhancing deposition current for dual-wire arc additive manufactured Ni-rich NiTi alloy. Addit Manuf. 2020 Aug;34:101240.10.1016/j.addma.2020.101240Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kuang W, Wang H, Li X, Zhang J, Zhou Q, Zhao Y. Application of the thermodynamic extremal principle to diffusion-controlled phase transformations in Fe-CX alloys: Modeling and applications. Acta Materialia. 2018 Oct;159:16–30.10.1016/j.actamat.2018.08.008Search in Google Scholar

[4] Yang W, Jiang X, Tian X, Hou H, Zhao Y. Phase-field simulation of nano-α′ precipitates under irradiation and dislocations. J Mater Res Technol. 2023 Jan;22:1307–21.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.11.165Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yang S, Huang Z, Hu Q, Zhang Y, Wang F, Wang H, et al. Proportional optimization model of multiscale spherical BN for enhancing thermal conductivity. ACS Appl Electron Mater. 2022 Aug;4(9):4659–67.10.1021/acsaelm.2c00878Search in Google Scholar

[6] Li X, Liu Y, Leng J. Large-scale fabrication of superhydrophobic shape memory composite films for efficient anti-icing and de-icing. Sustain Mater Technol. 2023 Sep;37:e00692.10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00692Search in Google Scholar

[7] Tang Y, Wang Y, Wu D, Chen M, Pang L, Sun J, et al. Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2023 Aug;62(1):20230347.10.1515/rams-2023-0347Search in Google Scholar

[8] Gubanski SM, Dernfalk A, Andersson J, Hillborg H. Diagnostic methods for outdoor polymeric insulators. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2007 Oct;14(5):1065–80.10.1109/TDEI.2007.4339466Search in Google Scholar

[9] Nazir MT, Xingliang J, Akram S. Laboratory investigation on hydrophobicity of new silicon rubber insulator under different environmental conditions. Dimensions. 2012;60(7):4–6.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hergert A, Kindersberger J, Bär C, Bärsch R. Transfer of hydrophobicity of polymeric insulating materials for high voltage outdoor application. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2017 Apr;24(2):1057–67.10.1109/TDEI.2017.006146Search in Google Scholar

[11] Swift DA, Spellman C, Haddad A. Hydrophobicity transfer from silicone rubber to adhering pollutants and its effect on insulator performance. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2006 Aug;13(4):820–9.10.1109/TDEI.2006.1667741Search in Google Scholar

[12] Banik A, Mukherjee A, Dalai S. Development of a pollution flashover model for 11 kV porcelain and silicon rubber insulator by using COMSOL multiphysics. Electr Eng. 2018 Jun;100:533–41.10.1007/s00202-017-0520-8Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang B, Wang S, Chen L, Li X, Tang N. Influence of oxygen on solid carbon formation during arcing of eco-friendly SF6-alternative gases. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2023 Jun;56(36):365502.10.1088/1361-6463/acd64eSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Zhu S, Li X, Bian Y, Dai N, Yong J, Hu Y, et al. Inclination‐enabled generalized microfluid rectifiers via anisotropic slippery hollow tracks. Adv Mater Technol. 2023 Aug;8(16):2300267.10.1002/admt.202300267Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lan L, Yao G, Wang HL, Wen XS, Liu ZX. Characteristics of corona aged Nano-composite RTV and HTV silicone rubber. In 2013 Annual Report Conference on Electrical Insul and Dielectric Phenomena 2013 Oct 20. IEEE; p. 804–8.10.1109/CEIDP.2013.6747063Search in Google Scholar

[16] Venkatesulu B, Thomas MJ. Long-term accelerated weathering of outdoor silicone rubber insulators. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2011 Mar;18(2):418–24.10.1109/TDEI.2011.5739445Search in Google Scholar

[17] Haddad G, Gupta RK, Wong KL. Visualization of multi-factor changes in HTV silicone rubber in response to environmental exposures. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2014 Oct;21(5):2190–8.10.1109/TDEI.2014.003871Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gorur R, Cherney E, Burnham J. Outdoor insulators, phoenix, arizona, usa, ravi s. gorur. Inc. 1999;4:179Y204.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Phillips AJ, Childs DJ, Schneider HM. Water drop corona effects on full-scale 500 kV non-ceramic insulators. IEEE Trans Power Delivery. 1999 Jan;14(1):258–65.10.1109/61.736734Search in Google Scholar

[20] Sarathi R, Mishra P, Gautam R, Vinu R. Understanding the influence of water droplet initiated discharges on damage caused to corona-aged silicone rubber. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2017 Sep;24(4):2421–31.10.1109/TDEI.2017.006546Search in Google Scholar

[21] Kumara S, Alam S, Hoque IR, Serdyuk YV, Gubanski SM. DC flashover characteristics of a polymeric insulator in presence of surface charges. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2012 Jun;19(3):1084–90.10.1109/TDEI.2012.6215116Search in Google Scholar

[22] Liu S, Liu S, Wang Q, Zuo Z, Wei L, Chen Z, et al. Improving surface performance of silicone rubber for composite insulators by multifunctional Nano-coating. Chem Eng J. 2023 Jan;451:138679.10.1016/j.cej.2022.138679Search in Google Scholar

[23] Xia Y, Song X, He J, Jia Z, Wang X. Evaluation method of aging for silicone rubber of composite insulator. Trans China Electrotech Soc. 2019;34:440–8.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Bi M, Deng R, Jiang T, Chen X, Pan A, Zhu L. Study on corona aging characteristics of silicone rubber material under different environmental conditions. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2022 Mar;29(2):534–42.10.1109/TDEI.2022.3163792Search in Google Scholar

[25] Nazir MT, Phung BT, Hoffman M. Performance of silicone rubber composites with SiO2 micro/nano-filler under AC corona discharge. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2016 Oct;23(5):2804–15.10.1109/TDEI.2016.7736840Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zhang G, Yang Z, Li X, Deng S, Liu Y, Zhou H, et al. Gamma-ray irradiation induced dielectric loss of SiO2/Si heterostructures in through-silicon vias (TSVs) by forming border traps. ACS Appl Electron Mater. 2024;6:1339–4610.1021/acsaelm.3c01646Search in Google Scholar

[27] Nazir MT, Phung BT, Yu S, Li S. Resistance against AC corona discharge of micro-ATH/nano-Al2O3 co-filled silicone rubber composites. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2018 Apr;25(2):657–67.10.1109/TDEI.2018.006914Search in Google Scholar

[28] Tahir MH, Arshad A, Manzoor HU. Influence of corona discharge on the hydrophobic behaviour of nano/micro filler based silicone rubber insulators. Mater Res Express. 2022 Mar;9(3):035302.10.1088/2053-1591/ac5b04Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zhu Y. Influence of corona discharge on hydrophobicity of silicone rubber used for outdoor insulation. Polym Test. 2019 Apr;74:14–20.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[30] Li X, Zhang Y, Chen L, Fu X, Geng J, Liu Y, et al. Study on the ageing characteristics of silicone rubber for composite insulators under multi-factor coupling effects. Coatings. 2023 Sep;13(10):1668.10.3390/coatings13101668Search in Google Scholar

[31] Reddy BS, Prasad DS. Effect of coldfog on the corona induced degradation of silicone rubber samples. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2015 Jun;22(3):1711–8.10.1109/TDEI.2015.7116368Search in Google Scholar

[32] Reddy BS. Corona degradation of the polymer insulator samples under different fog conditions. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2016 Feb;23(1):359–67.10.1109/TDEI.2015.005256Search in Google Scholar

[33] Du BX, Xu H, Liu Y. Effects of wind condition on hydrophobicity behavior of silicone rubber in corona discharge environment. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 2016 Feb;23(1):385–93.10.1109/TDEI.2015.005463Search in Google Scholar

[34] Nekeb A. Effect of some of climatic conditions in the performance of outdoor HV silicone rubber insulators (Doctoral dissertation). Cardiff University; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Stalder AF, Melchior T, Müller M, Sage D, Blu T, Unser M. Low-bond axisymmetric drop shape analysis for surface tension and contact angle measurements of sessile drops. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2010 Jul;364(1–3):72–81.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.04.040Search in Google Scholar

[36] Hillborg H, Gedde UW. Hydrophobicity changes in silicone rubbers. IEEE Trans Dielectr Electr Insul. 1999 Dec;6(5):703–17.10.1109/TDEI.1999.9286748Search in Google Scholar

[37] Saleem MZ, Akbar M. Review of the performance of high-voltage composite insulators. Polymers. 2022 Jan;14(3):431.10.3390/polym14030431Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Hillborg H, Gedde UW. Hydrophobicity recovery of polydimethylsiloxane after repeated exposure to corona discharges. Influence of crosslink density. In 1999 Annual Report Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (Cat. No. 99CH36319). Vol. 2, IEEE; 1999 Oct. p. 751–5.10.1109/CEIDP.1999.807914Search in Google Scholar

[39] Gubanski SM. Modern outdoor insulation-concerns and challenges. IEEE Electr Insul Mag. 2005 Nov;21(6):5–11.10.1109/MEI.2005.1541483Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface