Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

-

Shabbir Ahmed Khan

, Najam Ul Hassan

and Dongwhi Choi

Abstract

The Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (where x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15) nano ferrite powder was synthesized through chemical co-precipitation method, NaOH and acid oleic as raw materials. The XRD patterns confirmed the spinal structure phase purity of materials. XRD results showed that lattice parameter decreases with the increase of copper concentration by increasing copper concentration in the parent material. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to determine the morphology and particle size. SEM analysis indicated that all the samples are in nano size and homogeneous. AC electrical properties of nanoparticles were investigated by employing impedance spectroscopy. The real and the imaginary parts of impedance, permittivity, modulus along with the real part of ac conductivity, and tan delta were measured and analyzed for all synthesized samples in 1 Hz to 7 MHz for different voltages at 300 K.

1 Introduction

Ferrites are used in a variety of applications as they exhibit remarkable magnetic and electrical properties [1,2,3]. Spinel ferrites play an integral role in devices such as high-density information storage devices and in magnetic resonance imaging techniques [4,5,6]. Nickel ferrite is considered an important soft ferrite material among other materials because of its distinctive characteristics [7,8,9]. These include nominal losses in eddy current and lower values of electrical conductivity, and they also possess higher chemical stability [10,11,12]. Nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) exhibits counter spinal structure. It is utilized in a variety of technical applications, i.e. gas sensors, for the purification of water and also as catalyst [13,14,15]. It is observed that nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) properties are highly dependent on the variation of the composition and also on the route it has been synthesized. Literature shows various methods including the Sol-Gel technique, hydrothermal synthesis, solid-state reaction method, and co-precipitation method are used commonly for its preparation [16,17,18]. Co-precipitation method is regarded as the simplest, and the low temperature required for sintering and cost-effective technique among others. In this research, we have also used Co-precipitation for the synthesis of our samples [19,20,21]. In addition to the quick production of a uniform end product, this approach should also allow for the efficient separation of precipitates from the liquid solution and the ability to control or modify the size of the particles [22,23,24]. The key factor in the co-precipitation process is the careful selection of solvent, with water commonly being employed as the solvent [25,26,27]. Nevertheless, organic solvents can be employed, but at a significant expense [28,29,30]. Temperature is a fundamental component that is crucial in regulating particle size and the creation of different phases [31,32]. The co-precipitation process occurs at the ambient temperature, often within the range of 323–373 K, in order to expedite the precipitation. The pH value of the medium is the primary determinant in co-precipitation, as it strongly influences the phase formation. To achieve favorable results, it is recommended to maintain a pH level of approximately 12 [33,34,35].

In the literature, various reports show the study of NiFe2O4 in various compositions. Zheng et al. reported NiFe2O4-FeNi/C (NFO-FN/C) composites by confinement pyrolysis of the polydopamine for large-scale preparation and for the enhanced EMW absorption [36,37,38] Another report shows the synthesis of NiFe2O4 NPs and explored the uses in biomedical applications [39]. Gouadria et al. reported LaFeO3/NiFe2O4 nanohybrid for their efficient use in the photodegradation process [40]. Singh et al. studied the mixing of NiFe2O4 with Cu-doped ZnO (ZnO-Cu) for antibacterial applications [41]. Similarly, various other reports show the study of NiFe2O4 in various forms of compositions and composites and their potential applications referring towards the importance and large-scale production for soft ferrites [42,43,44,45,46,47]. This work intends to enhance the understanding further of how the addition of copper affects several properties of nickel ferrites, building upon existing literature on the subject.

This research study employs many methodologies to analyze the structure and electrical properties of the Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (where x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15) system. Due to the difference in the copper and nickel ionic radius, Cu caused lattice distortion and changes in the crystal structure when substituted. Copper doping can alter the electrical conductivity and polarization mechanisms in ferrite, enhancing dielectric parameters including permittivity and loss tangent. The synthesis of nano ferrite powder was achieved through chemical co-precipitation using NaOH and acid oleic. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to analyze the structural properties of the powder. The XRD patterns revealed the high purity of synthesized samples. According to XRD analysis, the lattice parameter decreases as the copper level in the parent material increases. The particle size and shape were assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis revealed that all samples exhibited a uniform and nanoscale size distribution. Alternating current impedance spectroscopy was employed to investigate the electrical properties of nanoparticles. The impedance, permittivity, modulus, AC conductivity, and tan delta of all compositions were analyzed at room temperature for different voltages over a frequency range of 1 Hz to 7 MHz.

2 Experimental method

Nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) samples were prepared by employing the co-precipitation method. Using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) 3 molar solutions, the precipitating agent is prepared. 0.4 Molar ferric chloride (FeCl3·6H2O > 99%) and 0.2 molar nickel chloride (NiCl2·6H2O > 99%) and CuCl₂·2H₂O > 99% solution was made and mixed slowly with the precipitating agent. NaOH solution was added dropwise while keeping note of pH. The reactants are continuously stirred with the help of a magnetic stirrer until a pH level of greater than 12 is achieved. As surfactant, oleic acid (2–3 drops) is mixed with the solution. Subsequently, this precipitate is stirred for about 40 min while maintaining the temperature to 80°C. The material being treated is then allowed to cool to room temperature. After that in order to expel the undesirable impurities and surfactant the sample under preparation is washed two times by ethanol and distilled water. In the centrifuge machine, the sample is centrifuged at a rate of 2,000 revolutions per minute (rpm), for about 15 min. It is then followed by an overnight drying session in an oven where the material is dried at 80°C. The material taken from the oven is then ground well to make it into powder form. Finally, it was subjected to a high temperature of 600°C in a furnace for 10 h. After the synthesis of the parent material, the next process is to fabricate the pellets before the execution of characterization. For the fabrication of the circular-shaped pellets hydraulic press is utilized. It exerted a pressure of 6 tons/inch2 for the duration of 2 min. The diameters of these pellets are 10 mm, and the thickness is maintained to 1.5 mm. After their fabrication, the pellets are subjected to the sintering process in a furnace. In the furnace, the temperature is kept at 600°C for 10 h. The final product after sintering is ready for further characterization processes. SEM instrument the structural properties of the synthesized powders are studied. The JSM5910 model of SEM is used for imaging the prepared samples, which is manufactured by JEOL, Japan. For impedance spectroscopy, the Alpha-N Analyzer, Novo control, Germany, was used that is installed in PINSTECH, Islamabad

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD analysis

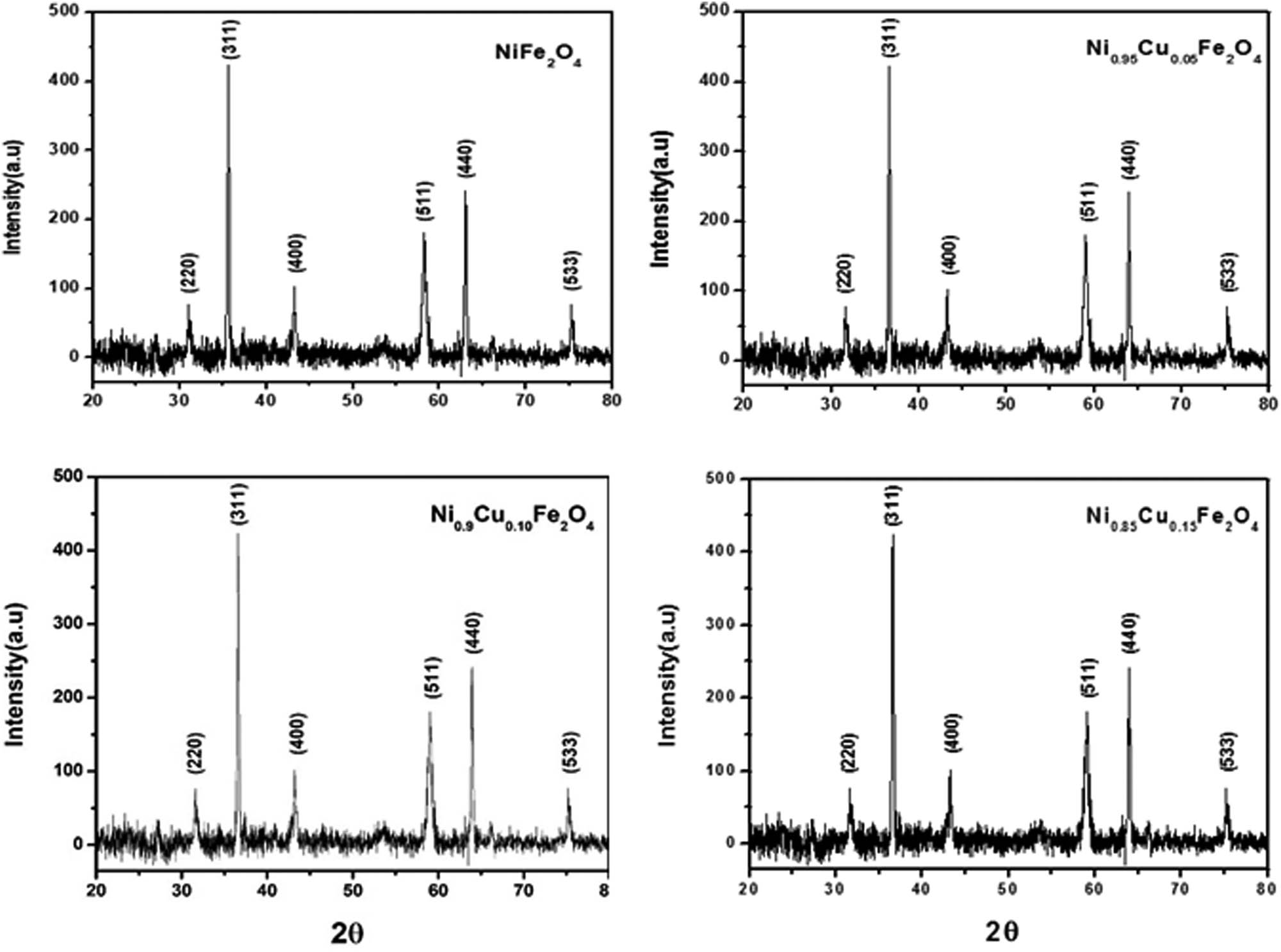

XRD Pattern for the parent sample (NiFe2O4) is shown in Figure 1(a). The diffraction pattern of the sample is analyzed, and the formation of spinal cubic structure is confirmed. The average crystallite size of the parent sample has been calculated from the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) using the Scherrer formula [48]

where D is the crystallite size, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray, β is full width at half maximum (FWHM) measured in radians, and θ is the Bragg angle. The X-ray diffraction pattern of the parent sample heated at 600°C is prepared by employing the co-precipitation method, all of the peaks shown in the pattern were successfully indexed. XRD result shows a single-phase cubic spinel structure with an average crystallite size of 40.52 nm. X’Pert Pro, Analytical, Netherlands machine is used for X-ray diffraction. By utilizing Cu Kα radiation (1.5418 Å) in XRD, the phase purity of the sintered pellets was affirmed. With a scanning step and counting time of 0.02° and 3 s, respectively, the XRD data were taken for 20° ≤ 2θ ≤ 80° by maintaining the temperature to room temperature. XRD pattern collected at room temperature of freshly synthesized parent sample (NiFe2O4). All of the peaks shown in the pattern were successfully indexed.

Powder XRD patterns of Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (where x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15).

The lattice parameter here determined from XRD data is a = 8.3400 Å. The lattice constants are reduced by increasing copper doping in the studied composition shown in Figure 1(b)–(d). This could be referred to the difference in the ionic radius of Cu ions being smaller ionic radius (0.73 Å) than Ni (0.74 Å) and Fe ions (0.67 Å) [49,50]. The cell volume of the parent sample is 580.09 Å3, and it is greater than the doped samples. The main diffraction planes are (220), (311), (400), (511), (440), and (533) with maximum diffraction intensity from the (311) plane. The presence of all these planes confirms the existence of a cubic spinel structure which is consistent with the data file of JCPDS PDF card no. 003-0875. These results are also in agreement with the previous work of Sivakumar et al., Maaz et al., Shahane et al., and Babu et al. [7,51,52,53]. Broad peaks were observed in the sample, demonstrating the lower degree of crystallization at a lower annealing temperature. These all values are in good agreement with the literature. The sharp diffraction peaks indicate a high degree of crystallization.

3.2 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Morphological analysis of all synthesized samples was done using SEM. The JSM5910 model of Scanning Electron Microscope is used for imaging the prepared samples, which is manufactured by JEOL, Japan. It is installed in the centralized resource laboratory (CRL), University of Peshawar, Peshawar. The JSM5910 SEM images the samples at magnifications of 5,000 up to 60,000 at a voltage of 15 kV. SEM micrographs of the NiFe2O4 pellets at the magnifications of 10 and 5 µm for Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (where x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15,) sintered at 600°C are shown in Figure 2. It is visible from the micrographs that there are even-size grains both in the nano and bulk regimes. A number of interfaces are also seen in these micrographs. There might be a change in resistivity due to the decrease in the mean free path which occurs as a result of decreased grain size. From the micrographs, it is observed that there are well-connected grains and very little porosity is present in the samples; in addition, an increase in the copper content decreases the grain sizes slightly. The pore size as well as the number of pores in unit area slightly varies with area. It is also observed that some grains have sharp grain boundaries while few other grains are intermixed. Grains lie in the range of 1–5 µm size.

SEM images of NiFe2O4, Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, 0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 nanoparticles.

3.3 Impedance spectroscopy

Impedance spectroscopy is used for investigating the ac electrical properties of nickel ferrite Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (where x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15,…) and to analyze the existing electroactive regions. The effect of voltage on different parameters is observed over a wide frequency range. The results of Impedance spectroscopy of the NiFe2O4 system reveal the presence of grains, grain boundaries, and electrode semiconductor contacts which are the electroactive regions. Impedance data is taken in the frequency range of 1–3 × 107 Hz. Different AC signals from 0.1 to 1 V were applied for the collection of relevant impedance data. The temperature is kept at room temperature. In Figure 3(a)–(d), the complex impedance plots the lower values are due to the effect of grains, and then, the medium range of values occurred because of the grain boundaries while the presence of electrode effects yields the higher values in this plot.

Complex impedance plots of (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1 to 1 V.

Figure 4(a)–(d) shows the variation of real impedance over frequency. In these plots, the three electroactive regions are present at lower, intermediate, and higher values of frequencies. There are higher values of impedance at lower frequencies, the reason behind this is the effect of grains. In the medium frequency range, the impedance values are intermediate due to the effect of grain boundaries. At the end where the frequencies are lower the impedance values are greater owing to the considerable electrode effects.

Variation of real impedance over frequency plots (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1 to 1 V.

In Figure 5(a)–(d), the effect of frequency on modulus′ is demonstrated. In these plots at lesser frequencies, the values of real and imaginary parts of modulus are also lower, this phenomenon occurs because of the effects of electrode and grain boundaries; on the other side, the values are increasing considerably at the elevated frequencies, and this is due to the grain effect. Figure 6(a)–(d) show the plots between the real part of permittivity with frequency. At higher frequencies, the lower values of the dielectric constant are due to grains while at lower frequencies the higher values of the dielectric constant correspond to interfacial effects, grain boundaries, and the electrode effect. The reduction in dielectric constant at elevated frequency values is quite a normal dielectric behavior [54,55]. The slight variations observed in the graphs for different compositions can be attributed to the saturation of the electroactive regions or the occurrence of the same electrical phenomenon in the voltage range.

Frequency vs real part of modulus plots of (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1–1 V.

Variation of electrical permittivity′ with frequency plots of (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1–1 V.

In Figure 6(a)–(d), it is obvious that the dielectric permittivity is decreasing as the frequency is increased this phenomenon occurs because with the increase of copper concentration, there is a decrease in the concentration of nickel ions (Ni2+). As a result of this, the Fe2+ ions yield less pairs for the hole, and ultimately, this results in electron hopping because of the buildup of charges across the grain boundaries which increase the resistance.

Figure 7(a)–(d) reveals the relation between frequency and ac conductivity. In 1977, Jonscher presented his famous power law [56,57,58,59]. The effect of frequency on the ac conductivity is elaborated in this law. A frequency-independent region represents the DC conductivity in the conductivity plot. It is then followed by an area where AC conductivity rises with the increase in frequency. The frequency from where the slope of the curve starts deviating is known as the hopping frequency. It is evident from the plot that the values of AC conductivity are lower at the lesser frequency end and they are higher at the larger frequency end the logic behind these variations is the electrode effect at the lower frequencies and the grain conductivity effect towards the higher frequency values. In between due to the grain boundaries effect, the values are intermediate at medium frequencies.

Frequency vs conductivity plots of (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1–1 V.

Figure 8(a)–(d) shows the dependence of tan delta with frequency. From this plot, three main regions can be noted prominently, where the values of tangent loss are lesser, medium, and higher. The reasons behind the noticeable variations in these values are the grains, grain boundaries, and electrode effects at the higher, medium, and lower frequency range, respectively. The frequency from where the slope of the curve starts deviating is known as the hopping frequency.

Frequency vs Tan Delta plots (a) NiFe2O4, (b) Ni0.95Cu0.05Fe2O4, (c) Ni0.90Cu0.10Fe2O4, and (d) Ni0.85Cu0.15Fe2O4 from 0.1–1 V.

4 Conclusions

Copper-doped NiFe2O4 particles with cubic spinal structure have been successfully synthesized by co-precipitation technique. XRD data confirmed the single-phase cubic spinel structure of copper-doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles. The lattice parameter has been calculated from the XRD pattern. The lattice parameter of Nickel ferrite was 8.34 Å and by increasing the copper concentration, the lattice parameter decreased by a small amount. The crystallite size of nickel ferrite calculated by Scherer’s formula was about 40.83 nm which decreases with the increase in copper concentration. SEM analysis indicated that all the samples are nano-sized and homogeneous. SEM examination has shown that the grains are usually well connected and there is very little porosity. SEM indicated that with copper concentration increase, the grain sizes have decreased. Impedance spectroscopic results of Ni1−x Cu x Fe2O4 (x = 0.05, 0.10, and 0.15) system show that there are three electroactive regions like G.B; grain and electrode are present. The conductivity decreases with increases in copper content. Modulus plots highlight the least capacitive phase of materials which are grains or bulk of materials whereas impedance plots highlight the more resistive phase of materials which are G.B and Electrodes or contacts. At higher frequencies, the lower value of permittivity is intrinsic whereas the higher value of permittivity at lower frequencies is extrinsic which is mainly due to interfacial effects.

Acknowledgments

SBK would like to acknowledge Dr. Javed Akhter and Dr. Mohammad Younas PINSTECH Islamabad for using their laboratory facilities for Impedance Spectroscopy. Thanks to Dr. Imran GC University of Faisalabad for helping me with pellet formation and XRD analysis of the samples. I would like to thank Dr. Manzoor Ahmad and Mr. Arshad for helping me with the SEM analysis. This work was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R243), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R243) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (RS-2024-00357072).

-

Author contributions: Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Shabbir Ahmed Khan. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Pullar RC. Hexagonal ferrites: A review of the synthesis, properties and applications of hexaferrite ceramics. Prog Mater Sci. 2012;57:1191–334.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2012.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[2] Guo J, Cai R, Cali E, Wilson GE, Kerherve G, Haigh SJ, et al. Low-temperature exsolution of Ni–Ru bimetallic nanoparticles from a-site deficient double perovskites. Small. 2022;18:1–10. 10.1002/smll.202107020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Sagadevan S, Chowdhury ZZ, Rafique RF. Preparation and characterization of nickel ferrite nanoparticles via co-precipitation method. Mater Res. 2018;21:e20160533. 10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2016-0533.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Janudin N, Kasim NAM, Feizal Knight V, Norrrahim M, Razak M, Abdul Halim N, et al. Fabrication of a Nickel Ferrite/Nanocellulose-Based Nanocomposite as an Active Sensing Material for the Detection of Chlorine Gas. Polymers (Basel). 2022;14:1906. 10.3390/polym14091906.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Narang SB, Pubby K. Nickel Spinel Ferrites: A review. J Magn Magn Mater. 2021;519:167163. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.167163.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhao XG, Yang D, Ren JC, Sun Y, Xiao Z, Zhang L. Rational design of halide double perovskites for optoelectronic applications. Joule. 2018;2:1662–73. 10.1016/j.joule.2018.06.017.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sivakumar P, Ramesh R, Ramanand A, Ponnusamy S, Muthamizhchelvan C. Preparation of sheet like polycrystalline NiFe2O4 nanostructure with PVA matrices and their properties. Mater Lett. 2011;65:1438–40.10.1016/j.matlet.2011.02.026Search in Google Scholar

[8] Raikher YL, Stepanov VI, Depeyrot J, Sousa MH, Tourinho FA, Hasmonay E, et al. Dynamic optical probing of the magnetic anisotropy of nickel-ferrite nanoparticles. J Appl Phys. 2004;96:5226–33.10.1063/1.1790574Search in Google Scholar

[9] Cross WB, Affleck L, Kuznetsov MV, Parkin IP, Pankhurst QA. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of ferrites MFe2O4 (M = Mg, Ba, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn); reactions in an external magnetic field. J Mater Chem. 1999;9:2545–52.10.1039/a904431kSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Song J, Chen Y, Hao X, Wang M, Ma Y, Xie J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of novel Ni–Cr–Co-based superalloy GTAW joints. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;29:2758–67.10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.01.241Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yuhua C, Yuqing M, Weiwei L, Peng H. Investigation of welding crack in micro laser welded NiTiNb shape memory alloy and Ti6Al4V alloy dissimilar metals joints. Opt Laser Technol. 2017;91:197–202.10.1016/j.optlastec.2016.12.028Search in Google Scholar

[12] Yang B, Wang H, Zhang M, Jia F, Liu Y, Lu Z. Mechanically strong, flexible, and flame-retardant Ti3C2Tx MXene-coated aramid paper with superior electromagnetic interference shielding and electrical heating performance. Chem Eng J. 2023;476:146834.10.1016/j.cej.2023.146834Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhu Q, Chen J, Gou G, Chen H, Li P. Hydrogen embrittlement behavior of SUS301L-MT stainless steel laser-arc hybrid welded joint localized zones. J Mater Process Technol. 2017;246:267–75.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.03.022Search in Google Scholar

[14] Huang Z, Luo P, Wu Q, Zheng H. Constructing one-dimensional mesoporous carbon nanofibers loaded with NaTi2(PO4)3 nanodots as novel anodes for sodium energy storage. J Phys Chem Solids. 2022;161:110479.10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110479Search in Google Scholar

[15] Luo P, Huang Z, Lyu Z, Ma X. In-situ fabrication of a novel CNTs-promoted Na3MnTi(PO4)3@C electrode in high-property sodium-ion storage. J Phys Chem Solids. 2024;188:111911.10.1016/j.jpcs.2024.111911Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhao L, Fang H, Wang J, Nie F, Li R, Wang Y, et al. Ferroelectric artificial synapses for high-performance neuromorphic computing: Status, prospects, and challenges. Appl Phys Lett. 2024;124:30501.10.1063/5.0165029Search in Google Scholar

[17] Guo J, He B, Han Y, Liu H, Han J, Ma X, et al. Resurrected and tunable conductivity and ferromagnetism in the secondary growth La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 on transferred SrTiO3 membranes. Nano Lett. 2024;24:1114–21.10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c03651Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Zhao Y. Co-precipitated Ni/Mn shell coated nano Cu-rich core structure: A phase-field study. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;21:546–60.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.09.032Search in Google Scholar

[19] Patange SM, Shirsath SE, Jadhav SS, Lohar KS, Mane DR, Jadhav KM. Rietveld refinement and switching properties of Cr3 + substituted NiFe2O4 ferrites. Mater Lett. 2010;64:722–4.10.1016/j.matlet.2009.12.049Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kumar R, Kumar R, Kumar Sahoo P, Singh M, Soam A. Synthesis of nickel ferrite for supercapacitor application. Mater Today Proc. 2022;67:1001–4. 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.05.433.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ishaq K, Saka AA, Kamardeen AO, Ahmed A, Alhassan MI, Abdullahi H. Characterization and antibacterial activity of nickel ferrite doped α-alumina nanoparticle. Eng Sci Technol an Int J. 2017;20:563–9. 10.1016/j.jestch.2016.12.008.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Rana G, Dhiman P, Kumar A, Vo DVN, Sharma G, Sharma S, et al. Recent advances on nickel nano-ferrite: A review on processing techniques, properties and diverse applications. Chem Eng Res Des. 2021;175:182–208. 10.1016/j.cherd.2021.08.040.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Ahmad U, Afzia M, Shah F, Ismail B, Rahim A, Khan RA. Improved magnetic and electrical properties of transition metal doped nickel spinel ferrite nanoparticles for prospective applications. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2022;148:106830. 10.1016/j.mssp.2022.106830.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Chakradhary VK, Ansari A, Akhtar MJ. Design, synthesis, and testing of high coercivity cobalt doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles for magnetic applications. J Magn Magn Mater. 2019;469:674–80. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.09.021.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Chen L, Dai H, Shen Y, Bai J. Size-controlled synthesis and magnetic properties of NiFe2O4 hollow nanospheres via a gel-assistant hydrothermal route. J Alloy Compd. 2010;491:L33–8. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.11.031.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Bao N, Shen L, Wang Y, Padhan P, Gupta A. A facile thermolysis route to monodisperse ferrite nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12374–5.10.1021/ja074458dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Koli PB, Kapadnis KH, Deshpande UG. Nanocrystalline-modified nickel ferrite films: an effective sensor for industrial and environmental gas pollutant detection. J Nanostruct Chem. 2019;9:95–110. 10.1007/s40097-019-0300-2.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Durgadsimi SU. Synthesis and structural analysis of nickel ferrite synthesized by co-precipitation method. Eurasian Phys Tech J. 2021;18:14–9. 10.31489/2021No4/14-19.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Kuang W, Wang H, Li X, Zhang J, Zhou Q, Zhao Y. Application of the thermodynamic extremal principle to diffusion-controlled phase transformations in Fe-C-X alloys: Modeling and applications. Acta Mater. 2018;159:16–30.10.1016/j.actamat.2018.08.008Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zhao Y, Sun Y, Hou H. Core-shell structure nanoprecipitates in Fe-xCu-3.0Mn-1.5Ni-1.5Al alloys: A phase field study. Prog Nat Sci Mater Int. 2022;32:358–68.10.1016/j.pnsc.2022.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[31] Yang W, Jiang X, Tian X, Hou H, Zhao Y. Phase-field simulation of nano-α′ precipitates under irradiation and dislocations. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;22:1307–21.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.11.165Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zhang Y, He X, Cong X, Wang Q, Yi H, Li S, et al. Enhanced energy storage performance of polyethersulfone-based dielectric composite via regulating heat treatment and filling phase. J Alloy Compd. 2023;960:170539.10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.170539Search in Google Scholar

[33] Li H, Wu HZ, Xiao GX. Effects of synthetic conditions on particle size and magnetic properties of NiFe2O4. Powder Technol. 2010;198:157–66.10.1016/j.powtec.2009.11.005Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zhu S, Zhu J, Ye S, Yang K, Li M, Wang H, et al. High-entropy rare earth titanates with low thermal conductivity designed by lattice distortion. J Am Ceram Soc. 2023;106:6279–91.10.1111/jace.19233Search in Google Scholar

[35] Jiang XJ, Bao SJ, Zhang LW, Zhang XY, Jiao LS, Qi HB, et al. Effect of Zr on microstructure and properties of TC4 alloy fabricated by laser additive manufacturing. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:8782–92.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.137Search in Google Scholar

[36] Zheng Z, Chen Y, Liu H, Lin H, Zhao H, Fang R, et al. Facile fabrication of NiFe2O4-FeNi/C heterointerface composites with balanced magnetic-dielectric loss for boosting electromagnetic wave absorption. Chem Eng J. 2024;481:148224.10.1016/j.cej.2023.148224Search in Google Scholar

[37] Long X, Chong K, Su Y, Du L, Zhang G. Connecting the macroscopic and mesoscopic properties of sintered silver nanoparticles by crystal plasticity finite element method. Eng Fract Mech. 2023;281:109137.10.1016/j.engfracmech.2023.109137Search in Google Scholar

[38] Long X, Chong K, Su Y, Chang C, Zhao L. Meso-scale low-cycle fatigue damage of polycrystalline nickel-based alloy by crystal plasticity finite element method. Int J Fatigue. 2023;175:107778.10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2023.107778Search in Google Scholar

[39] Manohar A, Prabhakar Vattikuti SV, Manivasagan P, Jang ES, Bandi H, Al-Enizi AM, et al. Exploring NiFe2O4 nanoparticles: Electrochemical analysis and evaluation of cytotoxic effects on normal human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) and mouse melanoma (B16-F10) cell lines. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2024;682:132855.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132855Search in Google Scholar

[40] Gouadria S, Al-Sehemi AG, Manzoor S, Abdullah M, Ghafoor Abid A, Raza N, et al. Design and preparation of novel LaFeO3/NiFe2O4 nanohybrid for highly efficient photodegradation of methylene blue dye under visible light illumination. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2024;448:115305.10.1016/j.jphotochem.2023.115305Search in Google Scholar

[41] Singh A, Yadav K, Kumar R, Slimani Y, Sun AC, Thakur A, et al. ZnO-Cu/NiFe2O4 magnetic nanocomposite with boosted photocatalytic and antibacterial activity against E. coli. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2024;37:101087.10.1016/j.nanoso.2023.101087Search in Google Scholar

[42] Gasser A, Ramadan W, Getahun Y, Garcia M, Karim M, El-Gendy AA. Feasibility of superparamagnetic NiFe2O4 and GO-NiFe2O4 nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia. Mater Sci Eng B. 2023;297:116721.10.1016/j.mseb.2023.116721Search in Google Scholar

[43] Li W, Zhou X, Kang Y, Zou T, Li W, Ying Y, et al. Microstructure and magnetic properties of the FeSiAl soft magnetic composite with a NiFe2O4-doped phosphate insulation coating. J Alloy Compd. 2023;960:171010.10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171010Search in Google Scholar

[44] Saha S, Routray KL, Hota P, Dash B, Yoshimura S, Ratha S, et al. Structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of green synthesized Ag doped NiFe2O4 spinel ferrite. J Mol Struct. 2024;1302:137409.10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.137409Search in Google Scholar

[45] Kumar A, Khanna K, Ram T, Dwivedi SK, Kumar S. Magnetic and magneto-dielectric properties of Nd3 + modified PbTiO3 and NiFe2O4 based multiferroic composites. Mater Today Proc. Epub ahead of print 2023. 10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.050.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Sivaprakash P, Divya S, Esakki Muthu S, Ali A, Jaglicic Z, Hwan Oh T, et al. Effect of rare earth Europium (Eu3 +) on structural, morphological, magnetic and dielectric properties of NiFe2O4 nanoferrites. Mater Sci Eng B. 2024;301:117200.10.1016/j.mseb.2024.117200Search in Google Scholar

[47] El Desouky FG, Saadeldin MM, Mahdy MA, El Zawawi IK. Tuning the structure, morphological variations, optical and magnetic properties of SnO2/NiFe2O4 nanocomposites for promising applications. Vacuum. 2021;185:110003.10.1016/j.vacuum.2020.110003Search in Google Scholar

[48] Patterson AL. The scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys Rev. 1939;56:978–82. 10.1103/PhysRev.56.978.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Pubby K, Meena SS, Yusuf SM, Bindra Narang S. Cobalt substituted nickel ferrites via Pechini’s sol–gel citrate route: X-band electromagnetic characterization. J Magn Magn Mater. 2018;466:430–45. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.07.038.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Belekar RM, Wani MA, Athawale SA, Kakde AS, Raghuvanshi MR. Minimum hysteresis loss and amplified magnetic properties of superparamagnetic Ni–Zn nano spinel ferrite. Phys Open. 2022;10:100099. 10.1016/j.physo.2022.100099.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Maaz K, Karim S, Mumtaz A, Hasanain SK, Liu J, Duan JL. Synthesis and magnetic characterization of nickel ferrite nanoparticles prepared by co-precipitation route. J Magn Magn Mater. 2009;321:1838–42 10.1016/j.jmmm.2008.11.098.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Shahane GS, Kumar A, Arora M, Pant RP, Lal K. Synthesis and characterization of Ni-Zn ferrite nanoparticles. J Magn Magn Mater. 2010;322:1015–9. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Babu KV, Kumar GVS, Satyanarayana G, Sailaja B, Sailaja Lakshmi CC. Microstructural and magnetic properties of Ni1-xCuxFe2O4 (x = 0.05, 0.1 and 0.15) nano-crystalline ferrites. J Sci Adv Mater Devices. 2018;3:236–42. 10.1016/j.jsamd.2018.04.003.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Moradmard H, Farjami Shayesteh S, Tohidi P, Abbas Z, Khaleghi M. Structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of magnesium doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles. J Alloy Compd. 2015;650:116–22. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.07.269.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Ishaque M, Islam MU, Azhar Khan M, Rahman IZ, Genson A, Hampshire S. Structural, electrical and dielectric properties of yttrium substituted nickel ferrites. Phys B Condens Matter. 2010;405:1532–40. 10.1016/j.physb.2009.12.035.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Salim E, Tarabiah AE. The influence of NiO nanoparticles on structural, optical and dielectric properties of CMC/PVA/PEDOT:PSS nanocomposites. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2023;33:1638–45. 10.1007/s10904-023-02591-2.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Solanki PD, Oza MH, Jethwa HO, Joshi J, Joshi G, Jayavel R, et al. Nickel pyrophosphate nanoparticles: synthesis, structural, thermal, spectroscopic, and dielectric studies. Nano. 2022;17:2250049. 10.1142/S1793292022500497.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Bhuyan MDI, Das S, Basith MA. Sol-gel synthesized double perovskite Gd2FeCrO6 nanoparticles: Structural, magnetic and optical properties. J Alloy Compd. 2021;878:160389. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160389.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Karmakar S, Behera D. High-temperature impedance and alternating current conduction mechanism of Ni0.5Zn0.5WO4 micro-crystal for electrical energy storage application. J Aust Ceram Soc. 2020;56:1253–9. 10.1007/s41779-020-00475-z.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy