Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

-

Muhammad Yahya Tahir

, Dahoon Ahn

and Dongwhi Choi

Abstract

Zinc-ion supercapacitors (ZISCs) exhibit great potential to store energy owing to the benefits of high power density and environmentally friendly features. However, solving the drawbacks of low specific energy and poor cyclic performance at high current rates is necessary. Thus, developing better cathode materials is a practical and efficient way to overcome these limitations. This work presents an encouraging design of two-dimensional (2D) graphite ultrathin nanosheets (GUNSs) as a cathode material for ZISCs. The experimental results show that the GUNSs-based cathode material exhibits a wide surface area and rapid charge transformation features. The 2D GUNS as a cathode was tested in three-electrode systems, and it provided an exceptionally high capacitance of 641 F/g at 1 A/g in an aqueous ZnSO4 electrolyte, better than GUNS-N2 (462 F/g at 1 A/g) and pristine graphite (225.8 F/g at 1 A/g). The 2D GUNS has a rate performance of 43.8% at a current density of 20 A/g, better than GUNS-N2 (35.6%) and pristine graphite (8.4%) at the same conditions. Furthermore, a ZISC device was fabricated using GUNSs as cathode and Zn-foil as anode with 1 M ZnSO4 electrolyte (denoted as GUNSs//Zn). The as-fabricated GUNSs//Zn device exhibits an excellent capacitance of 182.5 F/g at 1 A/g with good capacitance retention of 97.2%, which is better than pristine graphite (94.6%), and nitrogen-doped GUNS (GUNS-N2) cathode (95.7%). In addition, the GUNSs//Zn device demonstrated an ultrahigh cyclic life of 10,000 cycles, and 96.76% of capacitance was maintained. Furthermore, the GUNSs//Zn device delivers a specific energy of 64.88 W h/kg at an ultrahigh specific power of 802.67 W/kg and can run a light-emitting diode for practical applications.

1 Introduction

To obtain benefits from renewable energy sources, high-performance energy storage and conversion technologies are required to save energy, such as supercapacitors, batteries, and fuel cells [1,2,3]. However, the actual practical use at the grid level of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries is hampered by their low specific power and short lifespan due to slow ion-transport kinetics via intercalation/deintercalation [4,5]. Despite the progress made in lithium-ion batteries, other metal-ion batteries have also been researched alongside, such as potassium and sodium ion batteries [6,7]. Even though lithium-ion batteries are widely used in electric cars and portable electronics, there is still a pressing need for innovative battery systems that have the advantages of high voltage, cost-effectiveness, safety, and environmental friendliness, such as bivalent metal ion batteries such as magnesium [8], calcium [9], and zinc ion batteries [10]. Recently, many researchers have focused on dual-ion batteries, where the battery reaction involves both cations and anions [11,12]. DIBs possess higher energy densities than mono and divalent ion batteries; however, the power densities of batteries are low. Metal-ion supercapacitors, like lithium, sodium, and potassium ion supercapacitors, may successfully compensate for the insufficient specific power of rechargeable batteries. However, the extreme reactivity of these metals (lithium, sodium, and potassium) produces dendrite-at metal anodes, and the flammability of organic electrolytes offers severe safety concerns [13,14]. Therefore, aqueous energy storage technologies have gained a lot of interest because of their strong ionic conductivity and excellent safety benefits. Thus, it is extremely desirable to design unique and advanced aqueous energy storage devices with features like good safety, excellent specific power, and specific energy [15]. Lately, aqueous zinc-ion supercapacitors (ZISCs) have been designed, owing primarily to their superiorities in terms of cost-effectiveness, high specific energy, and extended lifespan [16,17].

ZISCs have been identified as the most appealing energy storage candidates due to their ability to combine the benefits of supercapacitors and batteries [18]. ZISCs typically consist of an anode of battery type and a cathode of capacitor type [19]. The metallic Zn-based negative electrode (anode) exhibits an excellent theoretical capacity of 823 mA h/g as well as a low redox potential of −0.76 V, making it a good energy storage material with a fairly large voltage window [19]. The working principle of ZISCs involves fast deposition/stripping of the Zn ion in the anode, resulting in high specific energy, and fast adsorption/desorption of the Zn ion on the cathode, resulting in high specific power [20].

Carbon-based materials have been the subject of much investigation for supercapacitors [21]. Carbon-based materials, including graphite, are becoming a new class of electrodes for supercapacitor systems due to their portability, excellent flexibility, easy fabrication methods, and outstanding electrical conductivity [22]. However, owing to its limited surface area, graphite foil exhibits a low specific capacitance. Its surface area might be enhanced via electrochemical exfoliation [23]. In high voltage, ions intercalate and transform into different gaseous species in the graphite layers in an electrolyte. The electrochemical exfoliation process expands the surface area. Although electrochemically exfoliated graphite foil has been used in several research reactors, the method is difficult and challenging to implement on intact systems [24,25].

Herein, we present an encouraging cathode design of two-dimensional (2D) graphite ultrathin nanosheets (GUNSs) for ZISCs. The experimental results show that the GUNS-based cathode material exhibits a wide surface area and rapid charge transport. GUNS exhibits a high capacitance of 641 F/g at 1 A/g, outperforming GUNS-N2 (462 F/g at 1 A/g) and pristine graphite (225.8 F/g at 1 A/g). GUNS has a good rate performance of 43.8% at 20 A/g, which is significantly higher than GUNS-N2 (35.6%) and pristine graphite (8.4%) in the same conditions. The resulting ZISC device (GUNSs//Zn) demonstrates an excellent capacitance (182.5 F/g at 1 A/g). Further, the GUNSs//Zn demonstrate an ultrahigh cyclic life of 10,000 cycles, and 96.76% of capacitance was maintained. Furthermore, GUNSs//Zn reveals a specific energy of 64.88 W h/kg at an ultrahigh specific power of 802.67 W/kg.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of 2D GUNSs

Carbon paper served as an electrode for the preparation of 2D GUNSs. A silver pad was used to attach the carbon to a tungsten wire, and it was then added to the solution as a negative electrode. The single carbon paper was submerged in the solution. With a 5 cm distance between them, a platinum plate was positioned side by side with carbon paper. About 5 g of sulfuric acid (H2SO4, Sigma-Aldrich; 98% concentration) was diluted in 100 mL of deionized water to obtain the ionic solution. The electrochemical exfoliation process was performed using an electrode made of carbon paper and a DC bias voltage. A 5 V is applied to the electrode and left undisturbed for 30 min to obtain a mixed solution. Add 100 mL of deionized water to the solution and stir well. The exfoliated carbon was filtered via a 100 nm membrane with deionized water to generate a 2D GUNS solution. After that, 2D GUNS was sonicated using a mild water bath for 5 min to disperse them in a dimethyl formamide (DMF) solution. The suspension was centrifuged at 2,500 rpm to eliminate undesired large particles created during the exfoliation. The centrifuged suspension can then be used for film production and further characterization. These electrochemical exfoliations were all carried out at ambient temperature.

2.2 Physical characterization

The material’s morphology was studied using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, HITACHI SU8220), a transmission electron microscope (TEM, FEI Themis Z), and an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer. To analyze crystal structure, an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, X’Pert Pro Analytical) by means of monochromatic radiations (Cu-Kα; = 0.15406 nm) was used. The elemental composition of 2D GUNS was studied using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

2.3 Electrochemical characterization

For the fabrication of the ZISC device, to design the positive electrode (cathode), the active substance, conductive carbon black, and polyvinylidene fluoride were combined in the ratio of 80:10:10 (wt%). The pulp mixture was mixed with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), pasted onto a carbon cloth (CC) of 1 × 1 cm2 surface, and dried for 6 h. About 1.2 mg/cm2 of active material was bulk-loaded onto the CC. The negative electrode (anode) was a Zn plate with 1 M ZnSO4 aqueous solution. The galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) and cyclic voltammogram (CV) were measured using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E, China). The CVs were performed in a voltage window varied from 0 to 1.6 V, while the GCD testing was performed at 1–10 A/g.

2.4 Calculations

According to the discharge time, calculate the specific capacitance of the single electrode device and apply equation (1):

where

In a two-electrode system, the optimal mass ratio of the positive electrode and the negative electrode can be calculated according to equation (2):

where

The ZISC device’s capacitance C d (F/g), specific power (P) (W/kg), and specific energy (E) (W h/kg) are all computed as follows:

where Δt (s) denotes the discharge time, I (A) denotes the current, M (g) shows the mass of both the anode and the cathode, and V (V) represents the voltage window.

3 Results and discussion

The sample was synthesized using an electrochemical exfoliation technique, making use of carbon paper (working electrode), platinum foil (counter electrode), and Ag/AgCl (reference electrode) in H2SO4. Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the technique for fabricating the 2D GUNS.

Schematic depiction of fabrication procedure of 2D GUNSs.

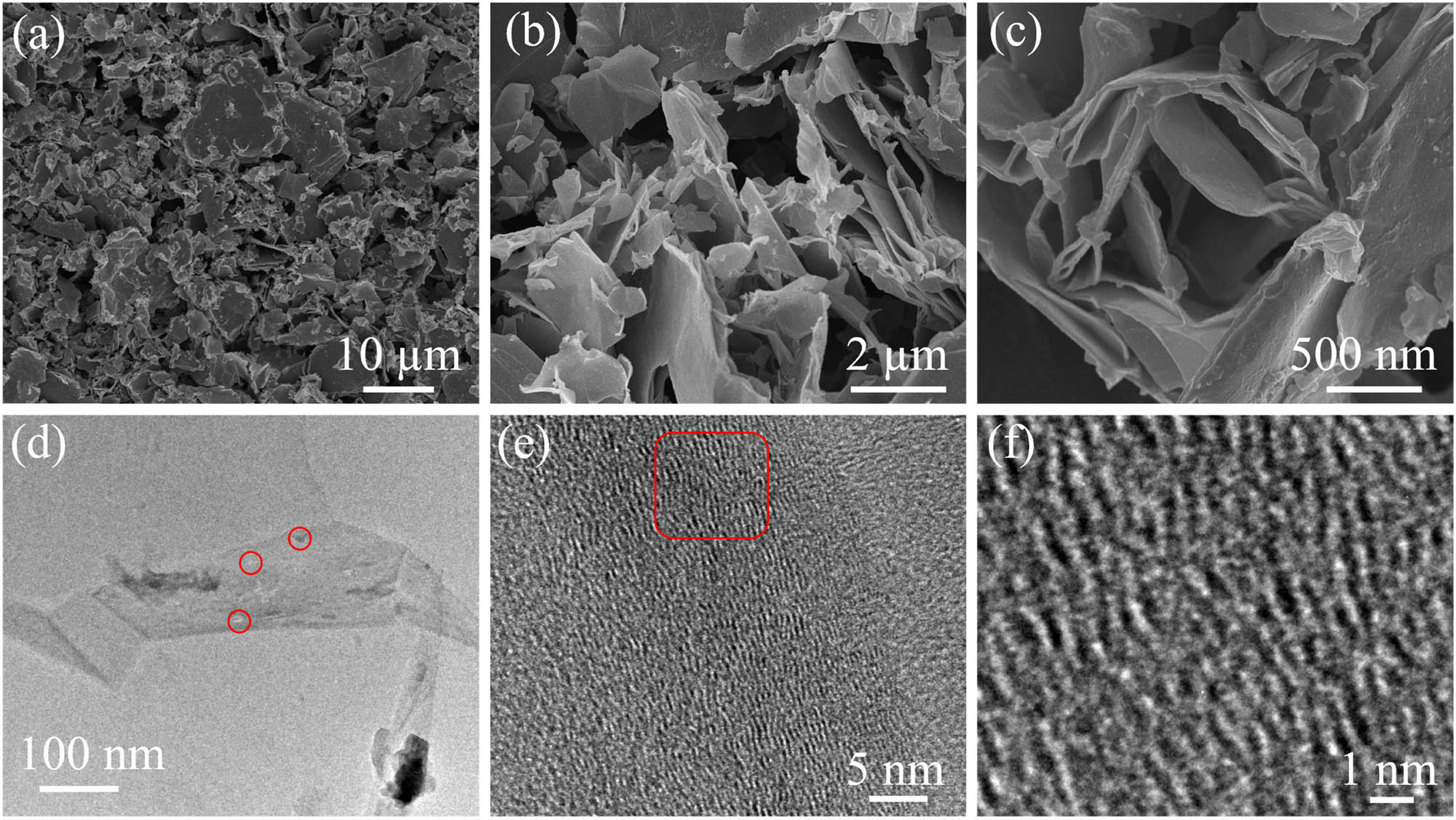

Figure 2a–c illustrates the low- and high-resolution FESEM images of 2D GUNS. All images exhibit crumpled and ultrathin nanosheets overlapped and randomly arranged and supported by the high-resolution FESEM image (Figure 2c). The morphology of the prepared sample is quite similar to that of already reported materials [26]. The geometrical characteristics of the 2D GUNSs and the extent of exfoliation can be seen by TEM images. Figure 2d–f displays TEM images of as-prepared 2D GUNSs. Low-resolution TEM image shows ultrathin sheet-like morphology of 2D GUNSs (Figure 2d), and tiny pores can be observed (marked with circles). Furthermore, the high-resolution TEM images (Figure 2e and f) exhibit that the porous graphite nanosheets consisted of four to six films and show a 0.3397 nm spacing, which is compatible with the (002) plane of graphite. Obviously, the elevated reactivity will provide the GUNSs with increased Zn ion storage. Additionally, the shorter ion transport route of porous GUNSs will help to enhance rate performance.

(a–c) Low- and high-resolution SEM images of 2D GUNSs, (d and e) low- and high-resolution TEM images of 2D GUNSs, and (f) HR-TEM image of 2D GUNSs.

The XRD image of 2D GUNS is depicted in Figure 3a. Two characteristics of carbon diffraction reflexes were discovered, including (002) and (101). The presence of a distinct diffraction peak (002) at 26.6° in 2D GUNSs provides evidence that this material is a kind of graphite [27]. The peak location of 2D GUNSs is identical to that of natural graphite, as described in the literature. Since carbon is the fundamental ingredient, the crystal layer of carbon is unaffected by the electrochemical exfoliation process [28]. In addition, the XRD of carbon paper and GUNS were further analyzed. As shown in Figure S1, we found that the position corresponding to the peak of the characteristic peak (002) of carbon before and after the exfoliation process does not shift, but the width of the peak increases. This is due to the formation of bulky 2D ultra-thin graphene nanosheets after exfoliation by electrochemical means, which form many voids during the nanosheet stacking process, thus increasing the spacing of the graphene nanosheets, resulting in a decrease in the crystallinity of the sample. In addition, the peak corresponding to the (101) crystal plane is shifted to the left, which proves the increase in crystal plane spacing.

(a) XRD patterns of 2D GUNSs, (b) C-1s XPS spectrum of 2D GUNSs, (c) O-1s XPS spectrum of 2D GUNSs, (d) the Raman spectra of the pristine graphite and 2D GUNSs, and (e and f) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore-size distribution curve.

Figure 3b displays a C-1s XPS spectrum of the 2D GUNSs obtained using XPS to study the existence of oxide defects. A dominating peak at 284.7 eV can be associated with (C–C) graphitic carbon. The deconvolution of the spectra showed the presence of many minor peaks with higher binding energies along with the C–C peak. Such characteristic peaks belong to oxides (284.6 eV belongs to C═C and 288.6 eV belongs to C═O) covalently bound extending to graphite in the case of an oxidized graphite. It is also possible that these peaks are due to solvent molecules that are still present inside the 2D GUNSs. Further, Figure 3c exhibits the O-1s XPS spectrum, which reveals two major peaks at 529.4 eV, ascribed to lattice oxygen, and 531.1 eV, ascribed to chemisorbed oxygen, respectively [29]. Therefore, the exceptional characteristics of the 2D GUNSs generated by high shear exfoliation were supported by XPS results, which are advantageous to enhancing the pseudocapacitive performance.

As shown in Figure 3d, we tested the Raman spectra of raw graphite and GUNS. It was observed that the G-band of the two samples remained unchanged. Compared to the original graphite, the peaks in the D-band of the GUNS were significantly reduced after electrochemical dissection, and the I D/I G value decreased from 0.61 to 0.22. This is attributed to electrochemical peeling, leading to many chemical bond breaks [30].

Specific surface area, porosity, and average pore diameter significantly affect the properties of ZHSC’s electrode material. As shown in Figure 3e, N2 adsorption–desorption measurements were investigated for the textural properties of GUNS. Rapid uptake at high relative pressure was identified as the isotherm type IV with an H3 hysteresis loop, which is relevant to mesoporous-like materials [31]. Distinctive hysteresis loop from 0.0 to 1.0 P/P 0 belongs to the typical Langmuir IV isotherms. The results show that GUNS has the largest BET-specific surface area of up to 59.8 m2/g, which is particularly suitable for energy storage applications due to GUNS-N2 and pristine graphite samples. Due to the large specific surface area, it can promote electrolyte ion diffusion, enhance charge transport, and provide more electroactive sites for fast energy storage. The corresponding pore size distribution (Figure 3f) calculated by the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda method from the desorption branch further confirms the characteristics of the mesoporous structure. The pore size of the GUNS rises sharply at 107.6 nm, which marks a layered mesoporous feature. This porosity is mainly due to multiple inclined intermediate pores, which enhance the mass transport of GUNS and improve the utilization of the active surface area of the electrode.

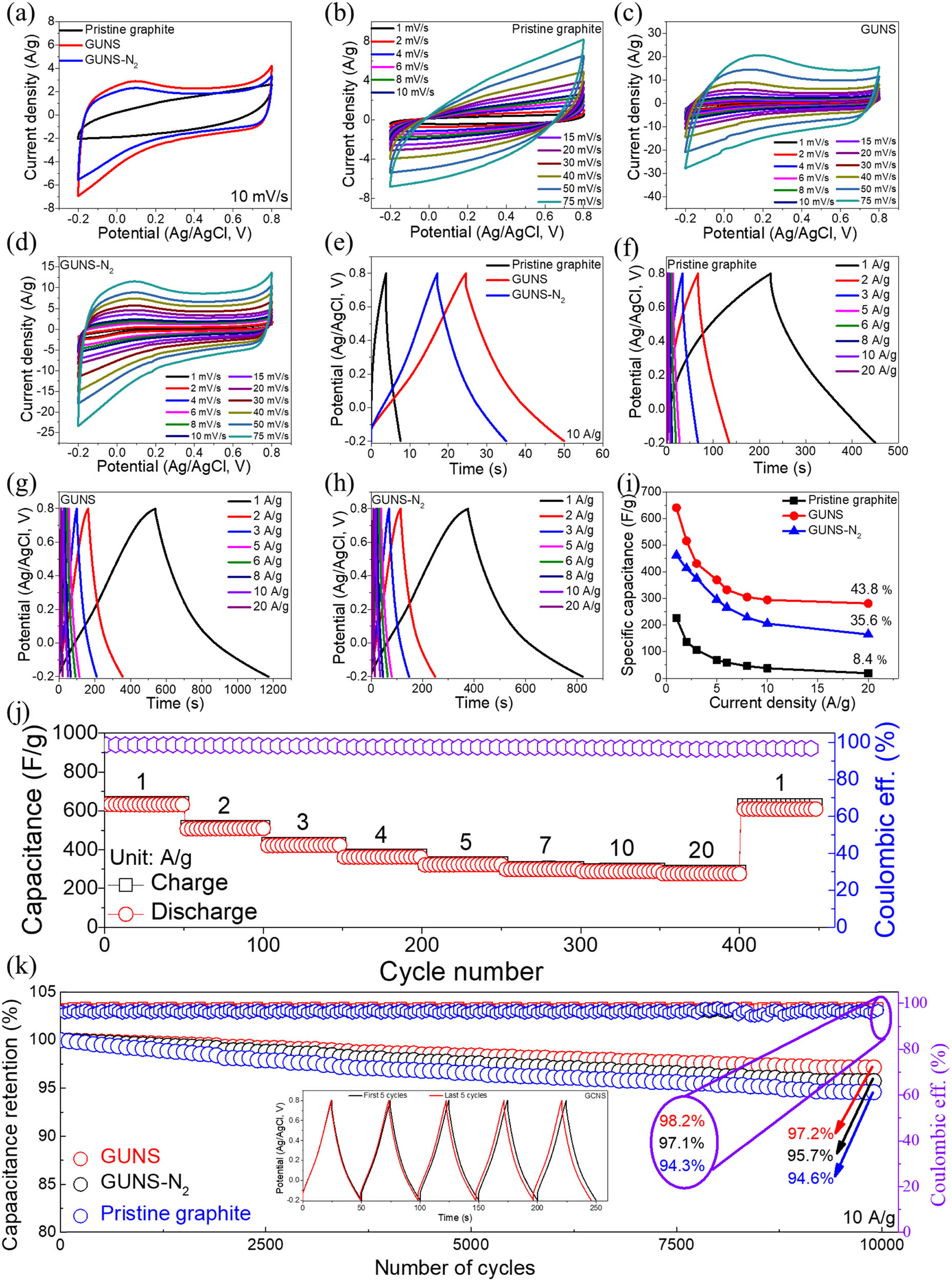

In a three-electrode system, the electrochemical performance of pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 was studied under a voltage window of −0.2 to 0.8 V using 1 M ZnSO4 aqueous solution as the electrolyte. Figure 4a shows the CV curves of pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 at a scan rate of 10 mV/s with a pair of redox peaks of GUNS and GUNS-N2. The GUNS obtained by electrochemical exfoliation has a large specific surface area, providing more active sites for zinc ions and promoting redox reaction. After N2 treatment, the abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface disappeared, decreasing the number of surface-active sites. As a result, the electrochemical performance is reduced. For further investigation, the CV curves are recorded at different scan rates (1–75 mV/s), as shown in Figure 4b–d. The shape of the CV curves of the electrodes remained stable as the scanning rates increased, indicating rapid mass transfer at the electrode/electrolyte interface. At different scan rates, GUNS electrodes have a larger area under the CV curve and greater charge storage capacity. In Figure 4e, the GCD curves of the pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes were compared at a current density of 10 A/g (potential window of −0.2 to 0.8 V). The GCDS electrode was observed to have a longer discharge time than the Ti3C2T x electrode, indicating higher charge storage capacity, which is consistent with the CV curves. Furthermore, GCD curves were recorded at different current densities from 1 to 20 A/g for pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes (Figure 4f–h). The quasi-triangular GCD curve of the pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes with high symmetry indicate high coulombic efficiency and excellent redox reaction reversibility. As shown in Figure 4i, the specific capacitance of the GCD curves for the three electrodes was also calculated. At a current density of 1 A/g, the GUNS electrode produces an ultra-high capacitance of 641 F/g, significantly larger than the GUNS-N2 (462 F/g at 1 A/g), and pristine graphite (225.8 F/g at 1 A/g) electrode. After the current density is increased to 20 A/g, the specific capacitance generated by the GUNS electrode decreases to 280.8 F/g, and the initial capacitance retention rate is about 43.8%, which is much larger than that of GUNS-N2 (35.6%) and pristine graphite (8.4%) electrodes, indicating that the GUNS electrode has good rate performance. This is attributed to increased specific surface area after exfoliation and the production of abundant oxygen-containing functional groups. After nitrogen treatment, the electrochemical performance decreases due to decreased surface oxygen-containing functional group content. Compared to GUNS, the specific capacitance and capacitance retention ratio of GUNS-N2 are reduced. Figure 4j shows the rate performance of the GUNS, with the specific capacitance values of 641, 517, 431, 370, 330, 304, 294, and 280 F/g at 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 20 A/g, respectively. When the current density is reduced to 1 A/g, a high discharge capacitance of 609.5 F/g can be recovered with a coulomb efficiency of up to 96.75%, demonstrating good electrochemical reversibility and fast reaction kinetics. As shown in Figure 4k, the GUNS electrode exhibited exceptional cycle stability after 5,000 GCD cycles, with a capacitance retention rate of 97.2%, compared to the pristine graphite electrode (94.6%) and GUNS-N2 electrode (95.7%). The coulombic efficiency of GUNS is as high as 98.2%, which is better than GUNS-N2 (97.1%) and pristine graphene (94.3%). The illustration in Figure 4k shows a comparison of the first and the last 6 GCD curves.

(a) Comparative CV curves of pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 in potentials window of –0.2 to 0.8 V at 10 mV/s; CV curves at various scan rates for (b) pristine graphite, (c) GUNS, and (d) GUNS-N2. (e) Comparative GCD curves of pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes. (f–h) GCD curves at various current densities range for pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes. (i) Specific capacitance as a function of current density. (j) Rate capability and Coulombic efficiency versus the number of cycles up to 450 cycles of GUNS electrode. (k) Capacitance retention concerning cycles up to 5,000 cycles for pristine graphite, GUNS, and GUNS-N2 electrodes (insets are first and last five cycles in 1 M ZnSO4 electrolyte).

Furthermore, we performed XRD and SEM tests on samples before and after the electrochemical reaction. The test results show that the peak of XRD shifts to the left after the electrochemical reaction due to the insertion of Zn-ions. The strength of the peak is significantly weakened, which is attributed to the electrochemical reaction reducing the material’s crystallinity. In addition, according to the comparison of SEM images before and after the reaction, the sample’s morphology remained stable, proving that it had superior electrochemical stability. However, some crystals appeared on the sample’s surface after the reaction, which was attributed to the precipitation of the electrolyte and recrystallization on the electrode surface (Figure S3).

We analyzed the XPS of different samples, and the C-1s spectrum showed a decrease in C═O, proving that the content of oxygen-containing functional groups was reduced (Figure S2). The SEM mapping of GUNS and GUNS-N2 was performed to demonstrate nitrogen functionalization, which reduces oxygen-containing functional groups, and these findings are consistent with XPS analysis (Figure S4(a) and (b)).

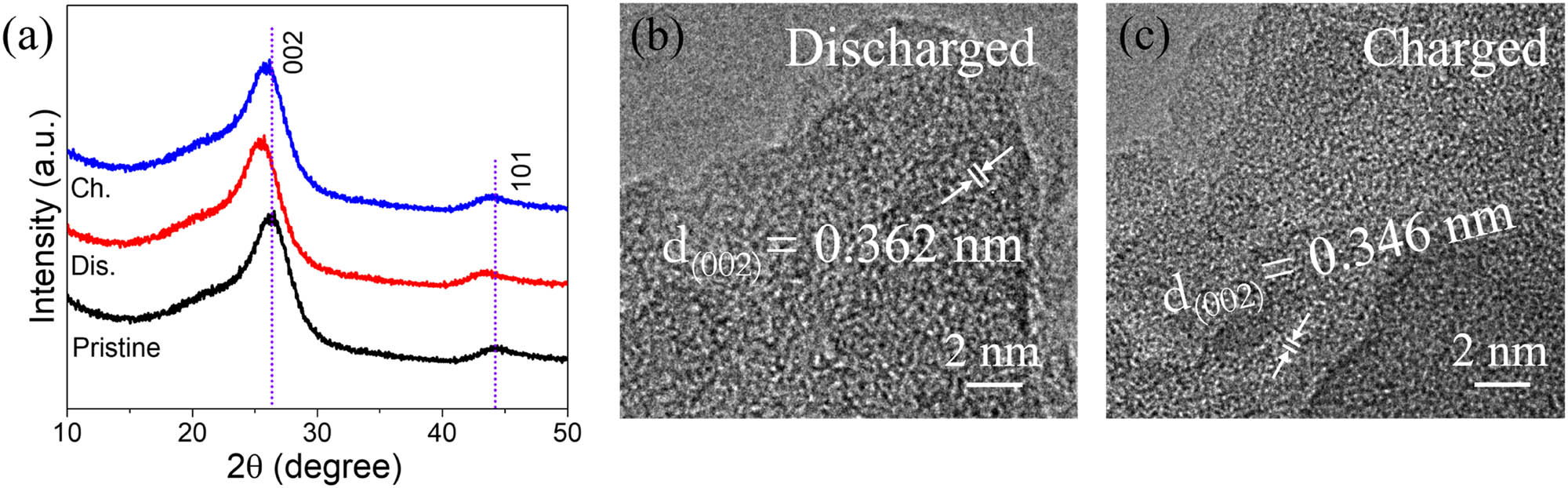

To further analyze the storage mechanism of Zn-ions, we performed ex situ XRD and TEM tests. As shown in Figure 5a, the peaks of the (002) crystal plane and (101) crystal plane of GUNS are shifted to the left after charging, proving that the crystal plane spacing has become larger, which is attributed to the insertion of Zn ions resulting in a wider lattice structure. In addition, the ex situ TEM test was also performed, and the crystal plane spacing was expanded to 0.362 nm after the end of charging (002), which proved the successful insertion of Zn ions. After the discharge, the crystal plane spacing became 0.346 nm, proving that the Zn ions were successfully inserted.

(a) Ex situ XRD of charge and discharge with GUNS. (b and c) HR-TEM images at discharge and charge.

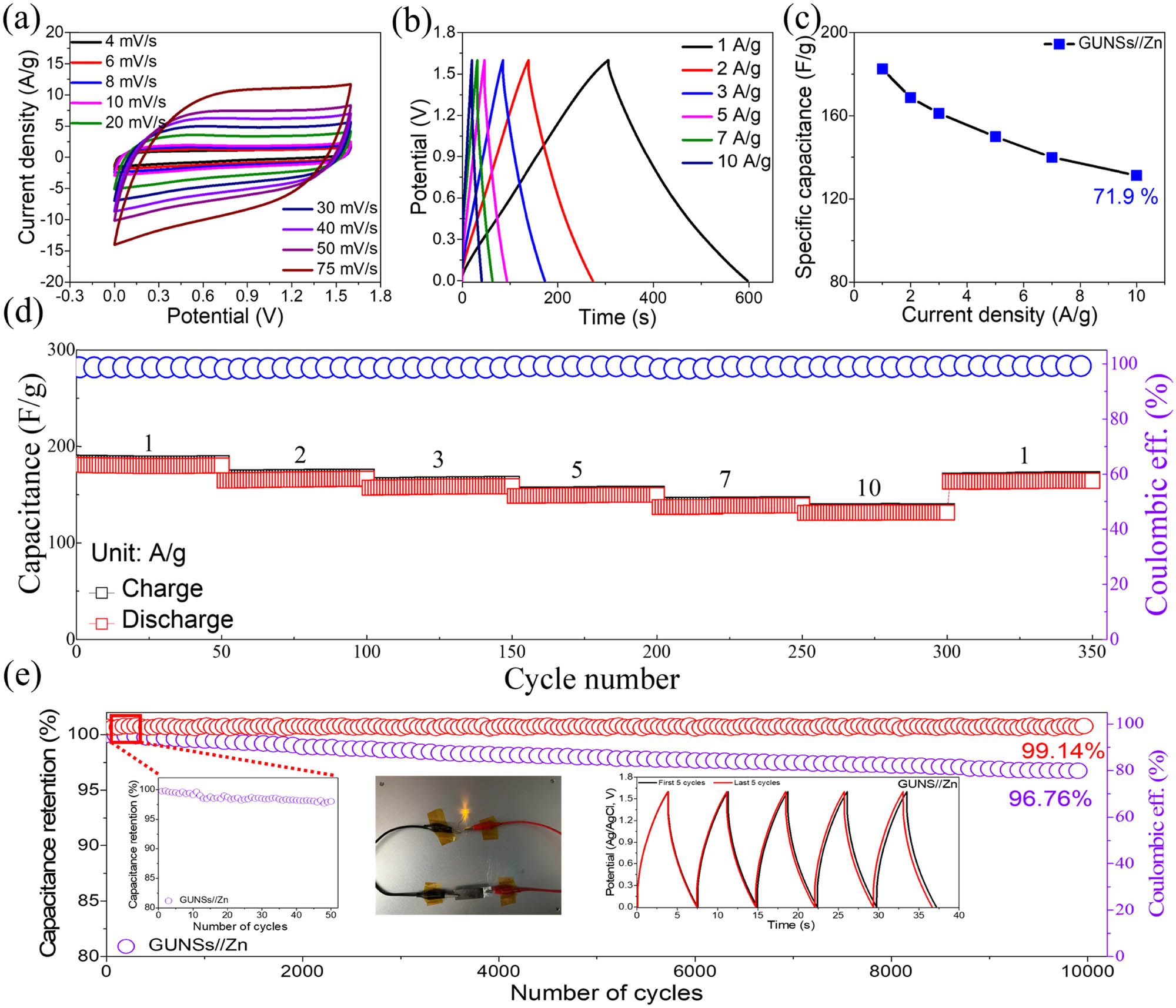

To examine the feasibility of the 2D GUNSs electrode for real-world practical applications, an aqueous GUNSs//Zn device was designed. Figure 6a depicts the CVs of GUNSs//Zn devices at different scan rates (4–75 mV/s). The approximately rectangular CV profiles supported the electrochemical double-layer approach. Even at high scan rates, the nearly rectangular-shaped CV profiles reveal the GUNSs//Zn device’s fast kinetics, extremely reversible characteristics, and excellent rate performance [24]. Across the porous surface, the electrolyte ions go through reversible absorption and desorption processes. Further, the GCD profiles of the GUNSs//Zn device at various current densities (1–10 A/g) are displayed in Figure 6b. The linear curve and symmetry revealed that the GUNSs//Zn device exhibited almost ideal behavior. With the decreasing current density, charge/discharge time increased. There is a little drop in potential, which is attributable to micropores that allow for fast electron and ion exchanges [32]. The specific capacitance (C d) of the GUNSs//Zn device has been computed using equation (1) and is shown in Figure 6c. The C d values of GUNSs//Zn device values are 182.5, 168.75, 161.25, 150, 140, and 131.25 F/g at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 A/g, respectively. GUNSs//Zn device maintained 71.9% of its capacitance even at 10 A/g. GUNSs//Zn device has excellent stability, with coulomb efficiency remaining at 99.2% after 350 cycles at different current densities (Figure 6d). In addition, the cycling stability of the GUNSs//Zn devices over 10,000 cycles of GCD was studied, and the results showed that 96.76% capacitance and 99.14% coulombic efficiency were maintained, showing superior performance (Figure 6e). The inset of Figure 6e compares the first and last six cycles of GCD curves of GUNS//Zn. For practical applications, one GUNS//Zn device can light one light-emitting diode (LED); a digital photograph of lighting the LED is shown in the inset of Figure 6e.

Electrochemical characterization of GUNSs//Zn device: (a) CVs, (b) GCDs, and (c) capacitance vs current density. (d) Rate capability and Coulombic efficiency versus the number of cycles up to 350 cycles of GUNSs//Zn device. (e) Cycling stability (insets are first and last five cycles in 1 M ZnSO4 electrolyte).

Electrochemically active surface areas of the catalysts were calculated based on the double-layer capacitance (C dl), which was obtained from cyclic voltammetry (CV) [33]. As shown in Figure S5, the C dl value of GUNS//Zn is determined to be 132 F/g.

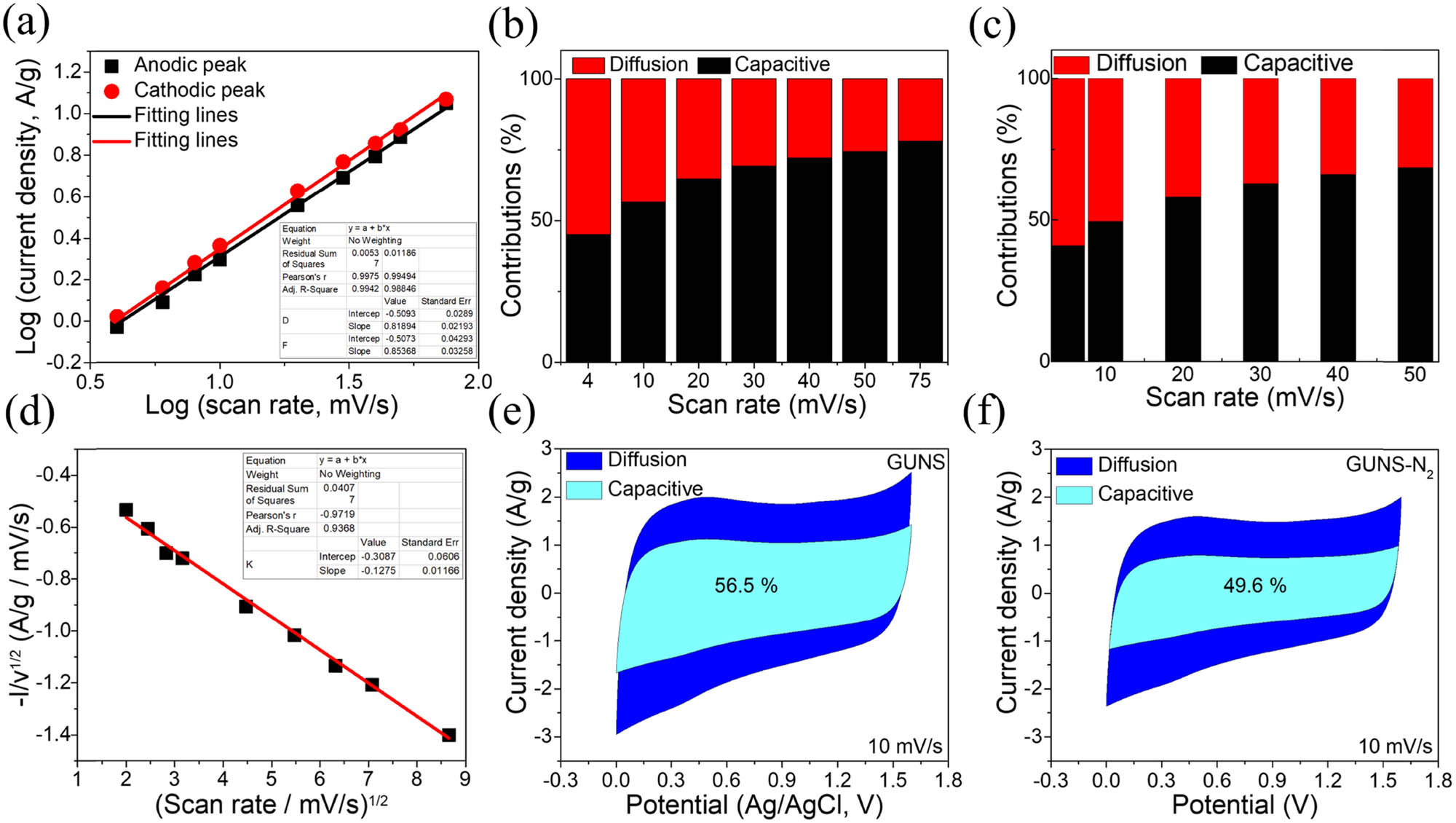

Moreover, the charge storage method of GUNSs//Zn was investigated by analyzing the electrochemical kinetics using power law [34]

In the above equations, v indicates scan rate, i indicates peak current density, and a indicates arbitrary constants. The most significant component is the b-value, which describes the charge storage behavior (if the b-value is equal to 0.5, the charge storage mechanism is diffusion-controlled; if the b-value is equal to 1, the charge storage mechanism is capacitive). The b-values were calculated using the slope of equation (5) [log(v) vs log(i)], and equal to 0.81 and 0.85, respectively (Figure 7a), that is approaching 1, showing the hybrid nature of charge storage, such as capacitive- and diffusion-controlled leads to high electrochemical performance [35]. The typical capacitive- and diffusion-controlled contributions were determined as follows:

(a) Calculation of b-values; (b and c) capacitive/diffusion methods at different scan rates (4–75 mV/s) of GUNS and GUNS-N2; (d) calculation of k 1 and k 2 values; (e and f) capacitive/diffusion methods at 10 mV/s of GUNS and GUNS-N2.

In the above equation, i indicates total current, k 1(v) and k 2(v)1/2 are capacitive and diffusion-controlled based parameters of charge storage, respectively. k 1 and k 1 indicate arbitrary constants. Figure 7b and c depicts trends in capacitive behavior observed at different scan rates for GUNS and GUNS-N2. The slope and y-intercept of the plots can be used to calculate the values of k 1 and k 2 (Figure 7d). In addition, at 10 mV/s, the GUNS stores 56.5% of the total charge by the capacitance method and 43.5% by the diffusion control mechanism (Figure 7e). The capacitor of GUNS-N2 stores 49.6% of the charge, and the diffusion control mechanism stores 50.4% (Figure 7f).

To examine the practical strength of the GUNSs//Zn device, the E and P of the device were computed. Figure 8 exhibits the Ragone plot. The GUNSs//Zn demonstrate specific energies of 64.88, 60, 57.33, 53.33, 49.77, and 46.66 W h/kg at 802.67, 1526.32, 2349.59, 4084.71, 5666.62, and 8270.12 W/kg. Furthermore, the current device outperforms several other previously explored SC and ZISC devices such as ZnCo2O4//AC (31.1 W h/kg, 759.9 W/kg) [36], Co@Co2O4//AC (38 W h/kg, 850 W/kg) [37], Zn–Ni–Al–Co//AC (36.5 W h/kg, 710 W/kg) [38], Zn foil//PDC (36.4 W h/kg, 376.6 W/kg) [39], MDC//Zn foam (36.4 W h/kg, 487.5 W/kg) [40], Zn//MXene-rGO (35.1 W h/kg, 278.8 kW/kg) [41], MXene/rGO//Zn (34.9 W h/kg at 279.9 W/kg) [42], and WC-6ZnN-12U//Zn@CC (27.7 W h/kg at 35.7 W/kg) [43]. These findings demonstrate the better performance of the GUNSs//Zn, including great cycle stability and exceptional specific energy. The main factor for the 2D GUNS material’s outstanding characteristics is its beneficial 2D GUNS characteristics. As a result, 2D GUNSs have a reasonably large surface area and an unusually high electrochemical activity.

E vs P in the Ragone plot and comparison with previously explored SCs and ZISCs devices.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a promising 2D GUNS cathode design for ZISCs. According to the experimental findings, the cathode material based on GUNSs exhibits a wide surface area and rapid charge transport. 2D GUNSs provide exceptional capacitance and specific energy during charging/discharging processes. The 2D GUNSs as a cathode was tested in three-electrode systems, and it provided an exceptionally high capacitance of 641 F/g at 1 A/g in an aqueous ZnSO4 electrolyte, which is better than the GUNS-N2 (462 F/g at 1 A/g) and pristine graphite (225.8 F/g at 1 A/g). When current density increases by a factor of 20 (20 A/g), the GUNS electrode still has an initial capacitance retention rate of 43.8%, which is much larger than that of the GUNS-N2 (35.6%) and pristine graphite (8.4%) electrodes. Furthermore, a ZISC device was fabricated using GUNSs as cathode and Zn-foil as anode with 1 M ZnSO4 electrolyte (denoted as GUNSs//Zn). In addition, extensive charge/discharge tests showed outstanding electrochemical stabilities; thus, the GUNSs//Zn device demonstrated an ultrahigh cyclic life of 10,000 cycles, and 96.76% of capacitance was maintained. Furthermore, GUNSs//Zn reveals a specific energy of 64.88 W h/kg at an ultrahigh specific power of 802.67 W/kg. This study paves the way for more investigation into 2D graphite materials for high-performance ZISCs.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the Research Fund for International Scientists (grant number 52250410342) and the Supercomputing Center of Lanzhou University. This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2024R765) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Liu B, Wang X, Chen Y, Xie H, Zhao X, Nassr AB, et al. Honeycomb carbon obtained from coal liquefaction residual asphaltene for high-performance supercapacitors in ionic and organic liquid-based electrolytes. J Energy Storage. 2023;68:107826.10.1016/j.est.2023.107826Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sha L, Sui B, Wang P, Gong Z, Zhang Y, Wu Y, et al. 3D network of zinc powder woven into fibre filaments for dendrite-free zinc battery anodes. Chem Eng J. 2024;481:148393.10.1016/j.cej.2023.148393Search in Google Scholar

[3] Huang Q, Jiang S, Wang Y, Jiang J, Chen Y, Xu J, et al. Highly active and durable triple conducting composite air electrode for low-temperature protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nano Res. 2023;16:9280–8.10.1007/s12274-023-5531-3Search in Google Scholar

[4] Hao W, Xie J. Reducing diffusion-induced stress of bilayer electrode system by introducing pre-strain in lithium-ion battery. J Electrochem Energy Convers Storage. 2021;18(2):020909.10.1115/1.4049238Search in Google Scholar

[5] Huang Z, Luo P, Wu Q, Zheng H. Constructing one-dimensional mesoporous carbon nanofibers loaded with NaTi2(PO4)3 nanodots as novel anodes for sodium energy storage. J Phys Chem Solids. 2022;161:110479.10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110479Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mu S, Liu Q, Kidkhunthod P, Zhou X, Wang W, Tang Y. Molecular grafting towards high-fraction active nanodots implanted in N-doped carbon for sodium dual-ion batteries. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;8(7):nwaa178.10.1093/nsr/nwaa178Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Huang Z, Luo P, Zheng H, Lyu Z, Ma X. Novel one-dimensional V3S4@NC nanofibers for sodium-ion batteries. J Phys Chem Solids. 2023;172:111081.10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.111081Search in Google Scholar

[8] Wang J, Zhang Y, Liu G, Zhang T, Zhang C, Zhang Y, et al. Improvements in the magnesium ion transport properties of graphene/CNT-wrapped TiO2-B nanoflowers by nickel doping. Small. 2024 Feb;20(6):2304969.10.1002/smll.202304969Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Wang M, Jiang C, Zhang S, Song X, Tang Y, Cheng H-M. Reversible calcium alloying enables a practical room-temperature rechargeable calcium-ion battery with a high discharge voltage. Nat Chem. 2018;10:667–72.10.1038/s41557-018-0045-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Luo P, Huang Z, Lyu Z, Ma X. In-situ fabrication of a novel CNTs-promoted Na3MnTi(PO4)3@C electrode in high-property sodium-ion storage. J Phys Chem Solids. 2024;188:111911.10.1016/j.jpcs.2024.111911Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang X, Tang Y, Zhang F, Lee C-S, Novel A. Aluminum–graphite dual-ion battery. Adv Energy Mater. 2016;6:1502588.10.1002/aenm.201502588Search in Google Scholar

[12] Chen C, Lee C-S, Tang Y. Fundamental understanding and optimization strategies for dual-ion batteries: a review. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023;15:121.10.1007/s40820-023-01086-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Zhu X, Xu Q, Li H, Liu M, Li Z, Yang K, et al. Fabrication of high-performance silver mesh for transparent glass heaters via electric-field-driven microscale 3D printing and UV-assisted microtransfer. Adv Mater. 2019;31(32):1902479.10.1002/adma.201902479Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Cai X, Shadike Z, Cai X, Li X, Luo L, An L, et al. Membrane electrode assembly design for lithium-mediated electrochemical nitrogen reduction. Energy Environ Sci. 2023;16:3063–73.10.1039/D3EE00026ESearch in Google Scholar

[15] Sufyan Javed M, Zhang X, Ali S, Shoaib Ahmad Shah S, Ahmad A, Hussain I, et al. Boosting the energy storage performance of aqueous NH4 + symmetric supercapacitor based on the nanostructured molybdenum disulfide nanosheets. Chem Eng J. 2023;471:144486.10.1016/j.cej.2023.144486Search in Google Scholar

[16] Javed MS, Najam T, Hussain I, Idrees M, Ahmad A, Imran M, et al. Fundamentals and scientific challenges in structural design of cathode materials for zinc‐ion hybrid supercapacitors. Adv Energy Mater. 2022;53:2202303.10.1002/aenm.202202303Search in Google Scholar

[17] Javed MS, Asim S, Najam T, Khalid M, Hussain I, Ahmad A, et al. Recent progress in flexible Zn‐ion hybrid supercapacitors: Fundamentals, fabrication designs, and applications. Carbon Energy. 2023;5(1):e271.10.1002/cey2.271Search in Google Scholar

[18] Javed MS, Mateen A, Ali S, Zhang X, Hussain I, Imran M, et al. The emergence of 2D MXenes based Zn‐ion batteries: recent development and prospects. Small. 2022;18:2201989.10.1002/smll.202201989Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Zhao L, Fang H, Wang J, Nie F, Li R, Wang Y, et al. Ferroelectric artificial synapses for high-performance neuromorphic computing: Status, prospects, and challenges. Appl Phys Lett. 2024;124(3):30501.10.1063/5.0165029Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhang W, Fu Q, Li J, Lian B, Xia Y, Zhou L, et al. Probing van der Waals magnetic surface and interface via circularly polarized X-rays. Appl Phys Rev. 2023;10(4):41308.10.1063/5.0164400Search in Google Scholar

[21] Gogotsi Y, Simon P. True performance metrics in electrochemical energy storage. Science. 2011;334:917–8.10.1126/science.1213003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Jang B, Kim H, Park S-W, Lim M, Lee J, Go G-M, et al. In situ exfoliation and modification of graphite foil in supercapacitor devices: a facile strategy to fabricate high-performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2021;11:4006–10.10.1039/D0RA10533CSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Munuera J, Paredes J, Enterría M, Pagán A, Villar-Rodil S, Pereira M, et al. Electrochemical exfoliation of graphite in aqueous sodium halide electrolytes toward low oxygen content graphene for energy and environmental applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:24085–99.10.1021/acsami.7b04802Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Wang Z, Fu W, Hu L, Zhao M, Guo T, Hrynsphan D, et al. Improvement of electron transfer efficiency during denitrification process by Fe-Pd/multi-walled carbon nanotubes: Possessed redox characteristics and secreted endogenous electron mediator. Sci Total Environ. 2021;781:146686.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146686Search in Google Scholar

[25] Liu Q, Chen Q, Tang Y, Cheng H-M. Interfacial modification, electrode/solid-electrolyte engineering, and monolithic construction of solid-state batteries. Electrochem Energy Rev. 2023;6:15.10.1007/s41918-022-00167-1Search in Google Scholar

[26] Liu J, Yang H, Zhen SG, Poh CK, Chaurasia A, Luo J, et al. A green approach to the synthesis of high-quality graphene oxide flakes via electrochemical exfoliation of pencil core. Rsc Adv. 2013;3:11745–50.10.1039/c3ra41366gSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Xu P, Yuan Q, Ji W, Yu R, Wang F, Huo N. Study on the annealing phase transformation mechanism and electrochemical properties of carbon submicron fibers loaded with cobalt. Mater Express. 2022;12:1493–501.10.1166/mex.2022.2302Search in Google Scholar

[28] Liu M, Huang J, Meng H, Liu C, Chen Z, Yang H, et al. A novel approach to prepare graphite nanoplatelets exfoliated by three-roll milling in phenolic resin for low-carbon MgO-C refractories. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2023;43:4198–208.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2023.02.064Search in Google Scholar

[29] Suk JW, Piner RD, An J, Ruoff RS. Mechanical properties of monolayer graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6557–64.10.1021/nn101781vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Liu Y, Qin J, Lu L, Xu J, Su X. Enhanced microwave absorption property of silver decorated biomass ordered porous carbon composite materials with frequency selective surface incorporation. Int J Miner Metall Mater. 2023;30:525–35.10.1007/s12613-022-2491-7Search in Google Scholar

[31] Eckmann A, Felten A, Mishchenko A, Britnell L, Krupke R, Novoselov KS, et al. Probing the nature of defects in graphene by Raman spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3925–30.10.1021/nl300901aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Huang X, Li S, Qi Z, Zhang W, Ye W, Fang Y. Low defect concentration few-layer graphene using a two-step electrochemical exfoliation. Nanotechnology. 2015;26:105602.10.1088/0957-4484/26/10/105602Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ye B, Kim J, Lee MJ, Chun SY, Jeong B, Kim T, et al. Mn-Ce oxide nanoparticles supported on nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide as low-temperature catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021;310:110588.10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110588Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zhang H, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Bai L, et al. Boosting Zn-ion adsorption in cross-linked N/P co-incorporated porous carbon nanosheets for the zinc-ion hybrid capacitor. J Mater Chem A. 2021;9:16565–74.10.1039/D1TA03501KSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Bhoyate S, Ranaweera CK, Zhang C, Morey T, Hyatt M, Kahol PK, et al. Eco‐friendly and high performance supercapacitors for elevated temperature applications using recycled tea leaves. Glob Chall. 2017;1:1700063.10.1002/gch2.201700063Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Javed MS, Khan AJ, Ahmad A, Siyal SH, Akram S, Zhao G, et al. Design and fabrication of bimetallic oxide nanonest-like structure/carbon cloth composite electrode for supercapacitors. Ceram Int. 2021;47:30747–55.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.254Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zhao X, Fan B, Qiao N, Soomro RA, Zhang R, Xu B. Stabilized Ti3C2Tx-doped 3D vesicle polypyrrole coating for efficient protection toward copper in artificial seawater. Appl Surf Sci. 2024;642:158639.10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.158639Search in Google Scholar

[38] Cai X, Li X, You J, Yang F, Shadike Z, Qin S, et al. Lithium-mediated ammonia electrosynthesis with ether-based electrolytes. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(47):25716–25.10.1021/jacs.3c08965Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Wang S, Liu Y, He L, Sun Y, Huang Q, Xu S, et al. A gel polymer electrolyte based on IL@NH2-MIL-53 (Al) for high-performance all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Chin J Chem Eng. 2024.10.1016/j.cjche.2024.01.017Search in Google Scholar

[40] Zhang Q, Zhao B, Wang J, Qu C, Sun H, Zhang K, et al. High-performance hybrid supercapacitors based on self-supported 3D ultrathin porous quaternary Zn-Ni-Al-Co oxide nanosheets. Nano Energy. 2016;28:475–85.10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.08.049Search in Google Scholar

[41] Zeng S, Shi X, Zheng D, Yao C, Wang F, Xu W, et al. Molten salt assisted synthesis of pitch derived carbon for Zn ion hybrid supercapacitors. Mater Res Bull. 2021;135:111134.10.1016/j.materresbull.2020.111134Search in Google Scholar

[42] Xiong T, Shen Y, Lee WSV, Xue J. Metal Organic framework derived carbon for ultrahigh power and long cyclic life aqueous Zn ion capacitor. Nano Mater Sci. 2020;2:159–63.10.1016/j.nanoms.2019.09.008Search in Google Scholar

[43] Wang Q, Wang S, Guo X, Ruan L, Wei N, Ma Y, et al. Mxene‐reduced graphene oxide aerogel for aqueous zinc‐ion hybrid supercapacitor with ultralong cycle life. Adv Electron Mater. 2019;5:1900537.10.1002/aelm.201900537Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects