Abstract

The beneficial effect of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to enhance the electrical conductivity and piezoresistivity of cement-based materials was highly contingent upon its dispersion. To achieve an appropriate dispersion of CNTs, ultrasonication, high-speed stirring, and chemical dispersion were commonly used, which raises the risk of structural damage of CNTs caused by the excessive energy. In this study, electrostatic self-assembly of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on CNTs was employed to efficiently disperse CNTs. To optimize the dispersion effect of conductive fillers in cement paste, the mix proportions including sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) concentration, CNTs concentration, and Fe3O4/CNTs ratios were adjusted. The dispersion degree and electrical property were evaluated by UV–vis absorption and zeta potential. In addition, the effect of self-assembled conductive filler dosage on the electrically conductive property of cement pastes was examined. The results show that the occurrence of electrostatic self-assembly was proved by the change of zeta potential, and the grape-bunch structure was observed by transmission electron microscopy. Further, the optimal proportions of self-assembled conductive fillers were 0.20 wt% SDS concentration, 0.05 wt% CNTs concentration, and 1:1 Fe3O4/CNTs ratio. The self-assembled conductive filler dosage between 0.02 and 0.10 wt% can effectively improve the electrical conductivity of cement paste with up to 68% reduction of resistivity.

1 Introduction

Concrete is widely used in the construction of infrastructure structure, such as highways, bridges, and tunnels. However, concrete structures are susceptible to developing cracks during service life due to brittle material properties and environmental influences, which can potentially result in severe accidents. Consequently, the global community has expressed significant interest in ensuring efficient monitoring and timely maintenance of concrete structures [1–3]. Conventional approaches to monitoring involve the installation of embedded sensors (e.g., strain gauge, optic sensors, piezoelectric ceramic, shape memory alloy, etc.) into the concrete structures. However, these traditional sensors have some drawbacks including poor compatibility, high failure probability, short service life, thus making it difficult to achieve a long-term structural monitoring [4,5]. As a solution, the self-sensing cement-based materials have garnered significant attention from researchers owing to their remarkable sensitivity, exceptional durability, and outstanding compatibility with concrete structures [6].

The self-sensing cement-based materials are developed by incorporating nano-conductive fillers into cement materials to achieve performance modification [7,8]. As a functional component, the incorporation of conductive fillers enables the induction of piezoresistivity into ordinary cement-based materials to form new cement-based sensors. The sensitivity of sensors is influenced by many factors, such as filler type, filler content, and filler dispersion [9,10]. Among nano-conductive fillers, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are found to be able to modify the properties of cement-based materials due to its excellent electrical conductivity, high chemical and thermal stability, and electromagnetic absorption properties [11–13]. In previous studies, the addition of CNTs was observed to induce a significant decrease in the electrical resistance of cement-based materials [14]. Based on the characteristic of resistance change, many research studies have been done on piezoresistivity and electrical conductivity of CNTs/cement-based materials. Li et al. observed that the addition of CNTs produced a remarkable increase in the piezoresistivity of cement pastes, with a fractional change in resistivity up to 14% [13]. Yu et al. investigated the piezoresistivity of CNTs/cement-based materials and observed a correlation between the piezoresistive response and compressive stress levels [15]. A study conducted by Han et al. demonstrated that the incorporation of CNTs in cement-based materials resulted in a highly responsive and stable behavior under repetitive stress, and further verified a significant response under vehicular loadings [16]. García-Macías et al. established a micromechanics model to predict the uniaxial stress-sensing property of CNTs/cement-based materials, which proved to be beneficial for structural health monitoring application [17]. Ding et al. reported a new self-sensing cementitious composite using directly growing CNT by in situ synthesized method, which was used in a smart system for crack development monitoring with high sensitivity and fidelity, indicating its potential for structural health monitoring [18,19].

Although CNTs/cement-based materials exhibited good piezoresistivity, the improvement of electrical conductivity and mechanical properties were affected by the dispersion of CNTs [20–24]. The uneven dispersion of CNT agglomerates would adversely affect the formation of the internal conductive network of the CNTs/cement-based materials, thus weakening their piezoresistivity [25]. It would also cause increased porosity of cement-based materials, resulting in reduction of mechanical properties [26,27]. Many methods, such as ultrasonication, mechanical stirring dispersion, and chemical dispersion methods were used to improve the dispersion of CNTs [28–30]. Although the above methods offered partial assistance in dispersing CNTs, they were accompanied by certain limitations such as extra energy consumption, potential structural damage of CNTs caused by the excessive ultrasonication energy [31–33].

Electrostatic self-assembly is a method in which atoms or molecules spontaneously arrange into an order structure based on the principle of mutual attraction of opposite charge, which is an effective technique for solving the dispersion of nanomaterials [34]. Additionally, electrostatic self-assembled conductive fillers can exhibit excellent electrical conductivity with a cooperative improvement effect, reinforcing the formation of a conductive network [35]. Many research have studied different types of electrostatic self-assembled fillers and found that the piezoresistive properties of smart cementitious composites was enhanced [31]. Due to its semiconductor and magnetic properties, the nano-Fe3O4 particles can realize a controllable distribution under the magnetic field assembled with CNTs, which has a great potential in monitoring application of vulnerable locations while avoiding stress concentration caused by external sensors.

However, limited research studies have been reported on the CNTs–Fe3O4 electrostatic self-assembled conductive fillers. In this article, a simple and general procedure for the electrostatic self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers was demonstrated in order to enhance the dispersion efficiency of CNTs, avoiding the traditional methods of energy consumption and damage of CNTs caused by excessive high energy. The microstructure and dispersion degree of the composite conductive fillers were analyzed, and the optimal ratios of the conductive filler were determined. Additionally, the effect of self-assembled conductive fillers on the electrically conductive properties of cement pastes was also addressed using the optimal ratio.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The raw materials used in this study included the multi-walled CNTs, Fe3O4 nanoparticles, surfactant, deionized water, and cement. The carboxyl (COOH)-functionalized multi-walled CNTs were purchased from Chengdu (China) Organic Chemical Co. Ltd. Referring to previous study, the size range of CNTs that contributed to the achievement of higher mechanical performance was selected, and the properties of CNTs are listed in Table 1 [36]. The Fe3O4 nanoparticles are A.R. grade (diameter: 20 nm, purity: 99.5%) and were supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd. An anionic, surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS,

Properties of functionalized CNTs

| Type | Outer diameter (nm) | Length (

|

Purity (wt%) | Specific surface area (m2/g) | –COOH functionalization (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNT | 10–30 | 10–30 | >95 | >110 | 1.55 |

SDS parameters

| Relative molecular mass | PH | Water (%) | Inorganic salt content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 288.4 | 7.5–9.5 | ≤3.0 | ≤7.5 |

Chemical compositions of cement (wt%)

| Components | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | 21.96 | 4.73 | 3.68 | 65.30 | 2.59 | 0.30 | 0.66 |

2.2 Self-assembled Fe3O4 nanoparticles along CNTs

The preparation flowchart of self-assembled conductive fillers is shown in Figure 1. The CNTs with COOH groups was negatively charged in an alkaline environment [37]. CNTs were first treated by anionic surfactant (SDS) to further make the surface negatively charged. The negatively charged CNTs self-assembled on the surface of positively charged Fe3O4 nanoparticles by electrostatic adsorption to form grape bunch structure together. Three parameters were adjusted to optimize the electrostatic self-assembly effect, including SDS concentration, CNTs concentration, and Fe3O4/CNTs ratios. The mix proportions of self-assembled conductive fillers are presented in Table 4. The concentration of SDS and CNTs was based on the wt% of SDS–CNTs dispersion.

Preparation flowchart of self-assembled conductive fillers.

Mix proportions of self-assembled conductive fillers

| SDS concentration (wt%) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| CNTs concentration (wt%) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | — |

| Fe3O4/CNTs ratio | 1:2 | 1:1.5 | 1:1 | 1.5:1 | 2:1 | — | — |

First, SDS were added into 100 mL deionized water and magnetically stirred at 40°C until fully dissolved, and then evenly mixed with CNTs using glass rod for 30 s. The mixed CNTs dispersion was subjected to a 15 min ultrasonication at 650 W. After that, the absorbance of CNTs dispersion was measured to determine the optimal SDS and CNTs concentration. CNTs and Fe3O4 nanoparticles with different mass ratios were added into deionized water (100 mL) and ultrasonically stirred for 20 min at 650 W. Finally, the CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersion was first ultrasonically stirred for 30 min and then magnetically stirred at 200 rpm for 2 h under 30°C to complete the electrostatic assembly. The optimal mass ratio of CNTs and Fe3O4 nanoparticles was then determined by UV–vis absorption test and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

2.3 Mix proportion and preparation of cement pastes

A total of ten sets of the self-assembled conductive fillers were prepared, with varying dosages (0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 wt% of cement) for each set. A water to cement ratio (w/c) of 0.35 and a dosage of 0.14 wt% (based on cement) defoaming agent was applied across all the mixes. A mix with pure CNTs (0.1 wt% of cement) was added as a reference. The mixing process of cement-based materials incorporating conductive fillers is illustrated in Figure 2. First, the weighed self-assembled conductive fillers and water were combined using a paste stirrer operating at a low speed of 140

Specimen fabrication process.

2.4 Testing methods

2.4.1 Zeta potential

A Zetasizer Nano ZS nano-particle zeta potential analyzer (Malvern, Britain) was utilized to analyze the zeta potential of CNTs dispersion, Fe3O4 nanoparticles dispersion, SDS–CNTs dispersion, and CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersion. Prior to the test, a small amount of supernatant was taken from the sample using a dropper and the zeta potential was determined after high dilution, with at least three measurements per sample.

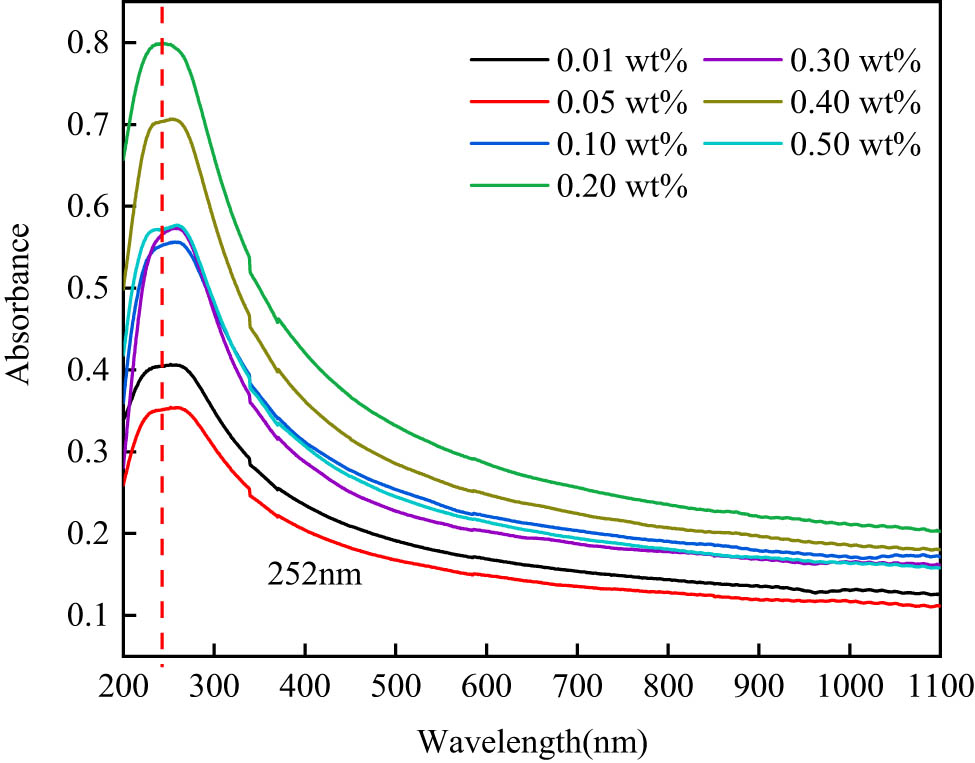

2.4.2 UV–vis absorption

Relevant absorption bands corresponding to additional absorption were observed in the UV–vis region for individual CNT particles, while agglomerated CNTs were inactive in the range of wavelength from 200 to 1,100 nm [40,41]. Therefore, a correlation could be established between the quantity of dispersed individual CNT particles and the strength of the absorption spectrum associated with them, and the better the differentiation of the absorption spectrum and the higher absorbance, the better the dispersion of CNTs [42].

The UV–vis absorption spectra were measured using a Metash UV8000 spectrometer in the wavelength range of 200–1,100 nm. In order to achieve a suitable concentration of CNTs for UV–vis measurements, the samples were diluted 100 times by adding a surfactant solution. The concentration of SDS in diluent was similar to that in CNTs dispersion to avoid the colloidal destabilization of CNTs [43]. The blank used was diluted by the same factor, under the same SDS concentration as the corresponding sample. For spectrophotometric measurements, three separate preparations and samplings were conducted for each dispersion of CNTs.

2.4.3 Microstructure characterization

A JSM-7610F scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and JEM-1011 TEM were used for microstructure characterization of the electrostatic self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers. The preparation of the samples involved immersing a copper grid in the CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersion, followed by a subsequent drying process.

2.4.4 Electrically conductive measurements

To eliminate the impact of contact resistance, a technique involving four electrodes was employed to measure the potential difference across the specimen [44]. After curing, the specimens were dried at 105°C in oven for 1 day prior to testing. During the measurement, a 305CF direct current (DC) power source was utilized. The voltage and current were observed using a digital multimeter manufactured by Keithley Instruments. The outer two current electrodes were subjected to a constant DC, while the potential difference was measured using the two inner voltage electrodes. The resistance was analyzed in relation to its current flow in order to investigate its ohmic behavior. The resistivity was calculated according

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of self-assembled conductive fillers

The zeta potential of different conductive filler dispersions is shown in Figure 3. The symbol of the zeta potential represented the electrical properties of ionic surface charges. For solutions with a single electrical property, the greater the absolute value of zeta potential, the better the dispersion stability of the particles in solution [45]. As observed from Figure 3, the surface of Fe3O4 particles was positively charged with a potential value of 25.4 mV, while the surface of CNT particles was negatively charged with a potential value of −2.5 mV, indicating that CNT particles were poorly stabilized in solution with agglomeration problems [46]. In order to enhance the dispersion of CNTs, 0.1 wt% SDS surfactant was added into the CNTs dispersion. The absolute zeta potential value of SDS–CNTs dispersion was increased to 38.1 mV, illustrating an increased electrostatic repulsion energy between particles and dispersion stability. In addition, the absolute value of zeta potential of 1:1 mixed CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersion was reduced to 15.1 mV, which can be attributed to the electrostatic self-assembly of the electrically opposite nanoparticles attracted to each other, resulting in a decrease in the absolute potential value. It is worth noting that the zeta potential of the dispersion after electrostatic self-assembly was not able to analyze its dispersion, which would be further characterized by UV–vis absorption test.

Zeta potential of different dispersions.

The morphologies of the electrostatic self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers were further determined by SEM as shown in Figure 4. As can be seen from the figure, there was almost no agglomeration between CNT particles, and a large number of Fe3O4 particles were adsorbed on the outer surface of CNTs, which improved the physical contact between CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers. The TEM image of the self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers is given in Figure 5, which showed that the Fe3O4 particles were evenly dispersed on the surface of CNTs, forming a synergistic combination effect from grape bunch structure to improve the dispersion of conductive fillers.

SEM image of self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers.

TEM image of self-assembled CNTs–Fe3O4 conductive fillers.

It should be emphasized that even after prolonged ultrasonication, the Fe3O4 particles could still be tightly immobilized on the CNTs surface, indicating that a robust electrostatic self-assembly occurred between these two types of nanoparticles, preventing their aggregation. At the same time, Fe3O4 particles acted as a spacer between CNT particles, preventing re-stacking to lose specific surface area of CNT particles, consequently enhancing the electrical conductivity of self-sensing cement-based materials.

3.2 Dispersion of self-assembled conductive fillers

3.2.1 Effect of SDS concentration

As shown in Figure 6, seven samples of SDS–CNTs dispersion with different SDS concentrations were selected for UV–vis absorption spectra test. The maximum absorbance of each sample was observed at

UV–vis absorption spectra of SDS–CNTs dispersions.

Figure 7 shows the absorbance of SDS–CNTs dispersion in variation of SDS concentration and CNTs concentration measured at the characteristic wavelength of 252 nm. At the same concentration of CNTs, the absorbance of CNTs dispersion steadily increased as the SDS concentration increased to 0.20 wt% and then slightly decreased when SDS concentration exceeded 0.20 wt%, which corresponded to the dispersion degree of CNTs in the aqueous SDS solutions. For a given SDS concentration, the absorbance of CNTs dispersion gradually increased with the CNTs concentration increasing. When the concentrations of CNTs were 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 wt%, the absorbance varied significantly with the SDS concentration, and peaked at 0.08, 0.52, and 0.70, respectively. However, there was little change in absorbance as the concentration of CNTs gradually increased to more than 0.50 wt%. The reason for this phenomenon was mainly related to the critical micelle concentration (cmc), an important property of anionic surfactant to highlight the role of the surfactant state (unimers vs micelles) in dispersion [43]. At low concentration, the SDS molecules were less adsorbed on the wall of CNTs, the repulsive force and spatial site resistance between particles were not enough to overcome the agglomeration between CNT particles. When the concentration of SDS was larger than cmc which exceeded the saturated adsorption of SDS on CNTs. Excessive SDS molecules combined in dispersion to generate a large number of micelles, which created osmotic pressure leading to the re-agglomeration of CNT particles [47–49]. According to the results, it can be concluded that the best CNTs dispersion was achieved at the SDS concentration of 0.2 wt%, so all subsequent experiments were carried out with an SDS concentration of 0.20 wt%.

Absorbance of CNTs dispersion.

3.2.2 Effect of CNTs concentration

As shown in Figure 8, the absorbance of CNTs dispersion increased initially and then decreased with the concentration of CNTs increasing. As the CNTs concentration increased to 0.05 wt%, the absorbance reached a peak of 0.55, which indicated that the CNT particles were best dispersed at this concentration. When the CNTs concentration exceeded 1.0 wt%, the absorbance of CNTs reached a plateau, which can be attributed to the high content of CNT particles that led to an obvious agglomeration, reaching the maximum dispersion degree of CNTs in the aqueous SDS solutions [50]. Therefore, a suitable concentration of CNTs should be selected in the preparation of self-assembled conductive fillers. CNTs concentration of 0.05 wt% was chosen to prepare the self-assembled conductive fillers for the following tests.

Absorbance of diluted CNTs dispersions.

3.2.3 Effect of the Fe3O4/CNTs ratio

Figure 9 shows the absorbance of CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersions at different ratios. It can be seen that the absorbance of the dispersions initially positively correlated to Fe3O4/CNTs ratios before 1:1, with the absorbance increased from 0.51 to 0.69. When the ratio of Fe3O4 to CNTs was over 1:1, the dispersion was basically invariant after slightly decreasing. The reason can be explained that Fe3O4 particles were adsorbed on the surface of CNTs due to electrostatic interaction, and their own bulk site resistance reduced the Van der Waals’ force between CNT particles to improve the dispersion of CNTs. With the increase of ratio up to 1:1, such effect was dominant. However, excessive Fe3O4 particles agglomerated, as the surface of CNTs was saturated for Fe3O4 adsorption, leading to a small reduction in CNTs dispersion and the absorbance [51].

Absorbance of CNTs–Fe3O4 dispersions.

Moreover, compared with the SDS–CNTs dispersion, the absorbance of the dispersion with a 0.2 wt% SDS concentration and a 0.05 wt% CNTs concentration was 0.52, while that of the dispersion with a 1:1 Fe3O4/CNTs ratio was 0.69, which proved that the self-assembly effect was superior to the surfactant for the dispersion of CNTs.

3.3 Micro-morphology of self-assembled conductive fillers

Figure 10 shows the morphologies of the self-assembled conductive fillers with different Fe3O4/CNTs ratios. With a gradual increase of Fe3O4 proportion (1:2–1:1), the amount of Fe3O4 particles attached to the CNTs surface increased, forming multiple grape bunch structure, resulting in a better dispersion of CNTs. However, with too many Fe3O4 particles (over 1:1), the interparticle attraction was larger than the electrostatic attraction, which made the dispersed CNTs re-agglomerate. The optimal ratio of Fe3O4 and CNTs for self-assembled conductive fillers was 1:1.

TEM images of self-assembled conductive fillers with different Fe3O4/CNTs ratios: (a) 1:2, (b) 1:1.5, (c) 1:1, (d) 1.5:1, and (e) 2:1.

3.4 Electrically conductive property of cement pastes with self-assembled conductive fillers

Due to the structure of the grape bunches, the conductive fillers can be uniformly dispersed in cement pastes. Based on literature [31], Fe3O4 and CNTs played the roles of short-range and long-range conductors in improvement of electrical conductivity for cement pastes, respectively, which was beneficial to piezoresistivity. As illustrated in Figure 11, the electrical resistivity of cement pastes with self-assembled conductive fillers significantly decreased by 68% when the content of self-assembled conductive fillers increased from 0 to 0.1 wt%, indicating that the conductive fillers could form widely distributed conductive network in cement-based materials. The electrical resistivity of cement-based materials with 0.02–0.1 wt% fillers decreased sharply. However, the resistivity changed marginally later (0.1–2 wt%), representing that self-assembled conductive fillers were excessive to form conductive network. Therefore, the content of conductive fillers between 0.02 and 0.1 wt% was the percolation threshold zone, where piezoresistivity could be displayed [52]. In comparison with results of CNTs–cement-based material (Table 5), the electrical resistivity of cement-based materials with self-assembled conductive fillers was 16.2% lower than that of cement -based materials with CNTs under the same dosage (0.1 wt%), indicating that the self-assembled conductive fillers had a better conductive effect.

Electrical resistivity of cement pastes with self-assembled conductive fillers.

Electrical resistivity of cement pastes with different conductive fillers

| Conductive filler type | Electrical resistivity (KΩ·cm) |

|---|---|

| CNTs | 26.5 |

| Self-assembled conductive fillers | 22.2 |

4 Conclusions

This article optimized the mix proportions of the electrostatic self-assembled conductive fillers using CNTs and Fe3O4 nanoparticles and investigated the effect of CNTs dosage on the electrically conductive property of cement-based materials. The following conclusions were drawn from the experimental results:

An easy-to-operate and stable method for the preparation of self-assembled conductive fillers was identified. The zeta potential results indicated that electrostatic self-assembly occurred between two types of nanoparticles, and a grape bunch structure was observed by SEM and TEM.

An optimal proportion of self-assembled conductive fillers was developed, i.e., 0.20 wt% SDS concentration, 0.05 wt% CNTs concentration, and 1:1 Fe3O4/CNTs ratio.

The electrically conductive property of cement-based materials increased with the self-assembled conductive fillers dosage increasing. Compared with the ordinary cement paste, the electrical resistivity was decreased by 68% at a self-assembled conductive fillers dosage of 0.1 wt%.

The ratio optimization of self-assembled conductive fillers improved the efficiency of self-assembly and the dispersion of fillers, and reduced the energy consumption. The increase in electrical conductivity proved that electrostatic self-assembled conductive fillers are promising modification materials to develop multifunctional and smart cement-based composites. The magnetic properties can be further used to carry out related studies.

-

Funding information: This project was supported by Science and Technology Project of Shandong High Speed Group Co., Ltd (Grant No. 1560021022), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2021QE174), the Open Project Fund of Key Laboratory of Concrete and Pre-stressed Concrete Structures of Ministry of Education in Southeast University (Grant No. CPCSME2022-03), and the Open Project Fund of Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Civil Engineering Structures & Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Technology (Grant No. ZKLCDF230301).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Hang B, Zhang LQ, Ou JP. Smart and multifunctional concrete toward sustainable infrastructures. Berlin: Springer; 2017.10.1007/978-981-10-4349-9Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ubertini F, Laflamme S, Ceylan H, Luigi Materazzi A, Cerni G, Saleem H, et al. Novel nanocomposite technologies for dynamic monitoring of structures: a comparison between cement-based embeddable and soft elastomeric surface sensors. Smart Mater Struct. 2014;23(4):045023.10.1088/0964-1726/23/4/045023Search in Google Scholar

[3] Galao O, Baeza FJ, Zornoza E, Garcés P. Strain and damage sensing properties on multifunctional cement composites with CNF admixture. Cem Concr Compos. 2014;46:90–8.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.11.009Search in Google Scholar

[4] Park S, Ahmad S, Yun CB, Roh Y. Multiple crack detection of concrete structures using impedance-based structural health monitoring techniques. Exp Mech. 2006;46(5):609–18.10.1007/s11340-006-8734-0Search in Google Scholar

[5] De Backer H, Corte W, Bogaert P. A case study on strain gauge measurements on large post-tensioned concrete beams of a railway support structure. Insight. 2003;45:822–6.10.1784/insi.45.12.822.52987Search in Google Scholar

[6] Dong W, Li W, Tao Z, Wang K. Piezoresistive properties of cement-based sensors: review and perspective. Constr Build Mater. 2019;203:146–63.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.081Search in Google Scholar

[7] Han B, Ding S, Yu X. Intrinsic self-sensing concrete and structures: a review. Measurement. 2015;59:110–28.10.1016/j.measurement.2014.09.048Search in Google Scholar

[8] Monteiro AO, Loredo A, Costa PMFJ, Oeser M, Cachim PB. A pressure-sensitive carbon black cement composite for traffic monitoring. Constr Build Mater. 2017;154:1079–86.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.053Search in Google Scholar

[9] Han J, Pan J, Cai J, Li X. A review on carbon-based self-sensing cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. 2020;265:120764.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120764Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bekzhanova Z, Memon SA, Kim JR. Self-sensing cementitious composites: review and perspective. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(9):2355.10.3390/nano11092355Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Jiang S, Zhou D, Zhang L, Ouyang J, Yu X, Cui X, Han B. Comparison of compressive strength and electrical resistivity of cementitious composites with different nano- and micro-fillers. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2018;18(1):60–8.10.1016/j.acme.2017.05.010Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kang I, Schulz MJ, Kim JH, Shanov V, Shi D. A carbon nanotube strain sensor for structural health monitoring. Smart Mater Struct. 2006;15(3):737–48.10.1088/0964-1726/15/3/009Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li GY, Wang PM, Zhao X. Pressure-sensitive properties and microstructure of carbon nanotube reinforced cement composites. Cem Concr Compos. 2007;29(5):377–82.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[14] Coppola L, Buoso A, Corazza F. Electrical properties of carbon nanotubes cement composites for monitoring stress conditions in concrete structures. Appl Mech Mater. 2011;82:118–23.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.82.118Search in Google Scholar

[15] Yu X, Kwon E. A carbon nanotube/cement composite with piezoresistive properties. Smart Mater Struct. 2009;18(5):055010.10.1088/0964-1726/18/5/055010Search in Google Scholar

[16] Han B, Yu X, Kwon E. A self-sensing carbon nanotube/cement composite for traffic monitoring. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(44):445501.10.1088/0957-4484/20/44/445501Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] García-Macías E, D’Alessandro A, Castro-Triguero R, Pérez-Mira D, Ubertini F. Micromechanics modeling of the uniaxial strain-sensing property of carbon nanotube cement–matrix composites for SHM applications. Compos Struct. 2017;163:195–215.10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.12.014Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ding S, Xiang Y, Ni Y-Q, Thakur VK, Wang X, Han B, Ou J. In-situ synthesizing carbon nanotubes on cement to develop self-sensing cementitious composites for smart high-speed rail infrastructures. Nano Today. 2022;43:101438.10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101438Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ding S, Wang X, Qiu L, Ni YQ, Dong X, Cui Y, et al. Self-sensing cementitious composites with hierarchical carbon fiber‐carbon nanotube composite fillers for crack development monitoring of a Maglev Girder. Small. 2022;19(9):2206258.10.1002/smll.202206258Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Camacho-Ballesta C, Zornoza E, Garcés P. Performance of cement-based sensors with CNT for strain sensing. Adv Cem Res. 2016;28(4):274–84.10.1680/adcr.14.00120Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bogas JA, Hawreen A, Olhero S, Ferro AC, Guedes M. Selection of dispersants for stabilization of unfunctionalized carbon nanotubes in high pH aqueous suspensions: application to cementitious matrices. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;463:169–81.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.196Search in Google Scholar

[22] Liew KM, Kai MF, Zhang LW. Carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious composites: an overview. Composites, Part A. 2016;91:301–23.10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.10.020Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mendoza Reales OA, Dias Toledo Filho R. A review on the chemical, mechanical and microstructural characterization of carbon nanotubes-cement based composites. Constr Build Mater. 2017;154:697–710.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.232Search in Google Scholar

[24] Ramezani M. Design and predicting performance of carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious materials: mechanical properties and dispersion characteristics: Electronic Theses and Dissertations; 2019.10.31224/osf.io/4nqcxSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Collins F, Lambert J, Duan WH. The influences of admixtures on the dispersion, workability, and strength of carbon nanotube–OPC paste mixtures. Cem Concr Compos. 2012;34(2):201–7.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.09.013Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ramezani M, Kim YH, Sun Z. Probabilistic model for flexural strength of carbon nanotube reinforced cement-based materials. Compos Struct. 2020;253:112748.10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112748Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ramezani M, Dehghani A, Sherif MM. Carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious composites: a comprehensive review. Constr Build Mater. 2022;315:125100.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125100Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zou B, Chen SJ, Korayem AH, Collins F, Wang CM, Duan WH. Effect of ultrasonication energy on engineering properties of carbon nanotube reinforced cement pastes. Carbon. 2015;85:212–20.10.1016/j.carbon.2014.12.094Search in Google Scholar

[29] Banerjee S, Hemraj-Benny T, Wong SS. Covalent surface chemistry of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2005;17(1):17–29.10.1002/adma.200401340Search in Google Scholar

[30] Sindu BS, Sasmal S. Properties of carbon nanotube reinforced cement composite synthesized using different types of surfactants. Constr Build Mater. 2017;155:389–99.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.059Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang L, Zheng Q, Dong X, Yu X, Wang Y, Han B. Tailoring sensing properties of smart cementitious composites based on excluded volume theory and electrostatic self-assembly. Constr Build Mater. 2020;256:119452.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119452Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ramezani M, Kim YH, Sun Z. Modeling the mechanical properties of cementitious materials containing CNTs. Cem Concr Compos. 2019;104:103347.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.103347Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ramezani M, Kim YH, Sun Z, Sherif MM. Influence of carbon nanotubes on properties of cement mortars subjected to alkali-silica reaction. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;131:104596.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104596Search in Google Scholar

[34] Chen Y, Xu J, Liu X, Tang Y, Lu T. Electrostatic self-assembly of platinum nanochains on carbon nanotubes: a highly active electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Appl Catal B: Environ. 2013;140–141:552–8.10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.04.049Search in Google Scholar

[35] Zhang S, Shao Y, Yin G, Lin Y. Carbon nanotubes decorated with Pt nanoparticles via electrostatic self-assembly: a highly active oxygen reduction electrocatalyst. J Mater Chem. 2010;20(14):2826.10.1039/b919494kSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Ramezani M, Kim YH, Sun Z. Mechanical properties of carbon-nanotube-reinforced cementitious materials: database and statistical analysis. Mag Concr Res. 2020;72(20):1047–71.10.1680/jmacr.19.00093Search in Google Scholar

[37] Seo J-W, US Shin. Preparation of positively and negatively charged carbon nanotube-collagen hydrogels with pH sensitive characteristic. J Korean Chem Soc. 2016;60(3):187–93.10.5012/jkcs.2016.60.3.187Search in Google Scholar

[38] Ramezani M, Kim YH, Sun Z. Elastic modulus formulation of cementitious materials incorporating carbon nanotubes: probabilistic approach. Constr Build Mater. 2021;274:122092.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122092Search in Google Scholar

[39] Park J, Jung M, Lee Y-W, Hwang H-Y, Hong S-G, Moon J. Quantified analysis of 2D dispersion of carbon nanotubes in hardened cement composite using confocal Raman microspectroscopy. Cem Concr Res. 2023;166:107102–240.10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107102Search in Google Scholar

[40] Saito R, Fujita M, Dresselhaus G, Dresselhaus MS. Electronic structure of chiral graphene tubules. Appl Phys Lett. 1992;60(18):2204–6.10.1063/1.107080Search in Google Scholar

[41] Kataura H, Kumazawa Y, Maniwa Y, Umezu I, Suzuki S, Ohtsuka Y, et al. Optical properties of single-wall carbon nanotubes. Synth Met. 1999;103(1):2555–8.10.1016/S0379-6779(98)00278-1Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jiang L, Gao L, Sun J. Production of aqueous colloidal dispersions of carbon nanotubes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;260(1):89–94.10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00176-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Dai W, Wang J, Gan X, Wang H, Su X, Xi C. A systematic investigation of dispersion concentration and particle size distribution of multi-wall carbon nanotubes in aqueous solutions of various dispersants. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2020;589:124369.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124369Search in Google Scholar

[44] Sun Z, Nicolosi V, Rickard D, Bergin SD, Aherne D, Coleman JN. Quantitative evaluation of surfactant-stabilized single-walled carbon nanotubes: dispersion quality and its correlation with zeta potential. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112(29):10692–9.10.1021/jp8021634Search in Google Scholar

[45] Hanaor D, Michelazzi M, Leonelli C, Sorrell CC. The effects of carboxylic acids on the aqueous dispersion and electrophoretic deposition of ZrO2. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2012;32(1):235–44.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2011.08.015Search in Google Scholar

[46] Parveen S, Rana S, Fangueiro R. A review on nanomaterial dispersion, microstructure, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotube and nanofiber reinforced cementitious composites. J Nanomaterials. 2013;2013:1–19.10.1155/2013/710175Search in Google Scholar

[47] Alexander K, Sheshrao Gajghate S, Shankar Katarkar A, Majumder A, Bhaumik S. Role of nanomaterials and surfactants for the preparation of graphene nanofluid: a review. Mater Today: Proc. 2021;44:1136–43.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.231Search in Google Scholar

[48] Jiang Y, Song H, Xu R. Research on the dispersion of carbon nanotubes by ultrasonic oscillation, surfactant and centrifugation respectively and fiscal policies for its industrial development. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;48:30–8.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.05.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Islam MF, Rojas E, Bergey DM, Johnson AT, Yodh AG. High weight fraction surfactant solubilization of single-wall carbon nanotubes in water. Nano Lett. 2003;3(2):269–73.10.1021/nl025924uSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Yu J, Grossiord N, Koning CE, Loos J. Controlling the dispersion of multi-wall carbon nanotubes in aqueous surfactant solution. Carbon. 2007;45(3):618–23.10.1016/j.carbon.2006.10.010Search in Google Scholar

[51] Chen Y, Yang Q, Huang Y, Liao X, Niu Y. Synergistic effect of multiwalled carbon nanotubes and carbon black on rheological behaviors and electrical conductivity of hybrid polypropylene nanocomposites. Polym Compos. 2018;39(S2):E723–32.10.1002/pc.24141Search in Google Scholar

[52] Han B, Zhang L, Sun S, Yu X, Dong X, Wu T, Ou J. Electrostatic self-assembled carbon nanotube/nano carbon black composite fillers reinforced cement-based materials with multifunctionality. Composites, Part A. 2015;79:103–15.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.09.016Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation