Abstract

Herein, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) were used as hybrid modifiers to enhance the mechanical properties of cement mortar and overcome the limitations of modification methods based on only polymers and nanomaterials. The use of PVA latex as a bridging agent with the aid of ultrasound energy effectively improved the dispersion uniformity and stability of CNTs. The results indicate that doping an appropriate amount of PVA in CNT-modified cement mortar, especially those modified with hydroxylated CNTs (h-CNTs), could synergistically improve performance. Amongst the samples, the h-CNT-modified cement mortar incorporated with 1 wt% PVA showed the optimal mechanical properties. The compressive and flexural strengths of this cement mortar increased by 33 and 42%, respectively, compared with those of cement mortars modified with h-CNTs alone. The microscopic characterisation results showed that the formation of a uniformly distributed h-CNT/PVA film network in the matrix effective filling of pores and bridging of cracks were responsible for performance enhancement.

1 Introduction

The unique graphene structure of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) endows them with excellent mechanical and electrical properties. For example, CNTs have tensile strength and elasticity modulus that are 100 and 5 times those of steel, respectively, while only having 1/6–1/7 the density of steel [1]. In addition, their electrical conductivity can reach 1,000–2,000 S cm−1, which is approximately 10,000 times than that of copper. Therefore, CNTs are superior to any known fibre material and are considered ideal reinforcing materials for cement composites. Previous studies have shown that CNTs doped at an appropriate amount can effectively improve the mechanical properties of cementitious materials. One reason for this enhancement is the fibre-bridging effect, which retards the formation and unfolding of microcracks through the adhesion of CNTs to hydration products [2,3,4]. Another reason is the filling effect of nanomaterials, wherein CNTs act as fillers of interstitial spaces in hydration products and improve defects. This effect is manifested macroscopically as a decrease in porosity and an increase in cement matrix strength [5,6]. In addition, in cement pastes, CNTs have a nucleation effect similar to that of the other nanoparticles and C–S–H gel easily agglomerates around CNTs instead of depositing on the unhydrated-cement particle surfaces [7,8]. Furthermore, adding CNTs to cementitious materials confers the materials with a range of functional properties that have been widely reported in several studies; these properties include strain and damage sensing and electromagnetic interference shielding [9,10,11,12]. These unique advantages make CNTs a strong contender for use in reinforced cementitious composites.

Although existing studies have confirmed the positive effects of CNTs on cement-based materials, some of their disadvantages remain to be addressed. High aspect ratios of CNTs lead to strong van der Waals attraction between CNTs resulting in the formation of agglomerate; this is a challenge for the application of CNTs in cementitious materials [13,14,15,16]. Although CNTs can be well dispersed in mixed water using specific dispersion techniques, the problem of geometry-dependent clustering, which occurs when cement particles are considerably larger than the spacing between inclusions, still hinders the homogeneous dispersion of CNTs in the matrix [17]. The mechanical properties of the cement matrix are largely affected by the formation and extension of cracks between hydration products. However, because nanotubes have small sizes, they cannot easily individually and effectively bridge large cracks and prevent further crack expansion. This situation is another drawback to the application of CNTs in cementitious materials. Therefore, finding a new method that enables the homogeneous dispersion of CNTs and their connection into long chain-like structures to strengthen their interactions with the cement matrix is necessary.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a water-soluble, biologically compatible, non-toxic and readily available low-cost synthetic polymer that has been used as a modifier and aggregate surface pre-treatment agent in cement-based composite materials [18,19]. PVA has excellent film-forming properties and can improve the tensile strength, flexural strength and impermeability of cementitious materials. PVA colloids are typical hydrophilic materials with strong cohesive energy, preventing aggregation and ensuring homogeneous nanoparticle dispersion. Research has shown that PVA can uniformly disperse CNTs without surfactants because it can form a hydrophilic colloid solution when an appropriate preparation technology is used. This colloid solution can prevent CNT aggregation and stabilise suspensions [20]. In addition, small amounts of CNTs can considerably enhance the tensile properties and thermal stability of PVA films. The combined application of CNTs and PVA in cement-based materials can overcome the limitations of modification methods based solely on polymers and nanomaterials. Furthermore, it is expected to further improve the mechanical properties and durability of building materials.

Because of its excellent performance as aforementioned, herein, PVA was expected to not only disperse CNTs but also to connect them with cement paste to further improve the mechanical properties of cement mortar. A two-stage experimental study was conducted. In the first stage, the single and combined effects of three types of CNTs (pristine, carboxylated and hydroxylated CNTs) and PVA on the mechanical properties of cement mortar were primarily investigated to identify the optimal CNT type. In the second stage, the identified CNTs were combined with PVA for cement mortar reinforcement and the effects of PVA content on the compressive strength, flexural strength, dry bulk density and water resistance of the resulting composites were investigated. The chemical interactions and microstructural characterisation of CNT/PVA complexes and the resulting mortar were also studied via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for understanding the mechanism underlying the performance enhancement in composite materials.

2 Experimental program

2.1 Raw materials

The cement used in this study was P.O 42.5 R Portland cement (produced by Guang dong Tapai Cement Co., Ltd.). Its chemical composition is shown in Table 1. PVA (PVA-124 AR) with a molecular weight of 105,000 and a hydrolysis degree of 97% was supplied by Xi-long Chemical Co., Ltd., China. The physicochemical characteristics of PVA are presented in Table 2. Three different types of multi-walled CNTs, namely, pristine CNTs (without surface functionalisation, designated as p-CNTs), hydroxylated CNTs (with –OH functional groups, designated as h-CNTs) and carboxylated CNTs (with –COOH functional groups, designated as c-CNTs), with average diameters of approximately 10–30 nm were provided by Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co., Ltd., China, and used in this study. The specific physical and chemical properties of the CNTs are presented in Table 3. The surface morphology of the three types of CNTs was observed by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-F200, Japan), as presented in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows that the walls of p-CNTs were smooth, whereas those of h-CNTs and c-CNTs were rough owing to the grafting of –OH and –COOH. The fine aggregate was China ISO standard sand satisfying the criterion of BS EN 196-1 (from Xiamen ISO Standard Sand Co., Ltd.). Its chemical composition and particle size are shown in Table 4. The defoaming agent, which had a polydimethylsiloxane content of 52–90%, was produced by Guangdong Defong Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.

Chemical composition of cement

| CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | SO3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | Na2O | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62.4 | 18.3 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 2.6 |

Physicochemical characteristics of the PVA

| Molecular weight | Degree of hydrolysis | PH | Volatile content | Ash content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 105,000 MW | 97 mol% | 5–7 | 5.0% | 0.7% |

Properties of three types of CNTs

| Raw material | Unit | p-CNTs | h-CNTs | c-CNTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External diameter | nm | 2–5 | 2–5 | 2–5 |

| Length | μm | 10–30 | 10–30 | 10–30 |

| Ash | wt% | <1.5 | <1.5 | <1.5 |

| Purity | wt% | >95 | >95 | >95 |

| Special surface area | m2 g−1 | >350 | >400 | >400 |

| Bulk density | g cm−3 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| True density | g cm−3 | ∼2.1 | ∼2.1 | ∼2.1 |

| Electric conductivity | s cm−1 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| −OH/−COOH content | wt% | — | 5.58 | 3.86 |

TEM images of (a) p-CNTs, (b) c-CNTs and (c) h-CNTs.

Chemical composition and particle size of sand

| SiO2 content | Mud content | Ignition loss | Particle size |

|---|---|---|---|

| >96% | <0.2% | <0.4% | 0.8–2 mm |

2.2 Mixing proportion and specimen preparation

Two series of specimens were prepared to investigate the synergistic effects of CNTs and PVA on the microstructure and mechanical properties of cement mortars. Their mixing proportions are given in Table 5. The specimens had a water/cement (with the CNTs and PVA)/sand ratio of 0.4:1:1.5 and a defoaming agent content of 0.14% of the mass fraction of cement. In the first stage (Series 1), the single and combined effects of different types of CNTs and PVA on the mechanical properties of cement mortars were investigated. In the second stage (Series 2), the effect of the incorporation of different PVA contents (0–2 wt%) on the properties of h-CNT-modified cement mortars was explored. The detailed preparation of the CNT/PVA cement mortars is as follows (Figure 2):

A weighed quantity of PVA powder was dissolved in distilled water and stirred with a magnetic stirrer at 95°C for approximately 30 min to obtain a homogeneous colloidal solution (Figure 2a).

A specific quantity of each type of CNT was added to the prepared PVA latex and mixed by ultrasonic dispersion in a bath-based sonicator for 1.5 h at 60°C to distribute the nanocomposite uniformly (Figure 2b).

The weighed cement and sand were dry mixed for approximately 3 min in a rotary mixer. Afterwards, CNT/PVA nanocomplexes and the remaining water were added to the above mixture and wet-mixed at moderate speed for 2 min. Finally, the mixture was added with the defoamer and mixed at high speed for 2 min (Figure 2c).

The mixture prepared in step (3) was poured into oiled moulds, and an electric vibrator was used to ensure good compaction (Figure 2d).

The curing method has a great influence on the mechanical properties of mortar, and it is necessary to standardise the curing process for all samples [21]. In the present work, all specimens were demoulded after 1 day of curing and then cured in air for 27 days (average annual humidity was approximately 84–92% and temperature was 22–28°C; Figure 2e).

Mixing proportions of CNT/PVA modified cement mortar (unit: g)

| Series | Mix ID | Cement | Sand | Water | CNTs | PVA | Defoaming agent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series 1 | CM | 100 | 150 | 40.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| NCM | 100 | 150 | 40.20 | 0.5 (p-CNTs) | 0 | 0.14 | |

| HCM | 100 | 150 | 40.20 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0 | 0.14 | |

| CCM | 100 | 150 | 40.20 | 0.5 (c-CNTs) | 0 | 0.14 | |

| PCM | 100 | 150 | 40.24 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.14 | |

| NPCM | 100 | 150 | 40.44 | 0.5 (p-CNTs) | 0.6 | 0.14 | |

| HPCM | 100 | 150 | 40.44 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0.6 | 0.14 | |

| CPCM | 100 | 150 | 40.44 | 0.5 (c-CNTs) | 0.6 | 0.14 | |

| Series 2 | HPCM0(HCM) | 100 | 150 | 40.20 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0 | 0.14 |

| HPCM1 | 100 | 150 | 40.28 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0.2 | 0.14 | |

| HPCM2 | 100 | 150 | 40.36 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0.4 | 0.14 | |

| HPCM3 (HPCM) | 100 | 150 | 40.44 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 0.6 | 0.14 | |

| HPCM4 | 100 | 150 | 40.06 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 1.0 | 0.14 | |

| HPCM5 | 100 | 150 | 41.00 | 0.5 (h-CNTs) | 2.0 | 0.14 |

Flow chart of sample preparation. (a) PVA latex. (b) CNT/PVA nanocomposite. (c) Mixing of cement mortar. (d) Pour into mold and vibrate. (e) Specimens were demolded after 1 day and then curing in air for 27 days (22–28°C).

2.3 Test methods

2.3.1 Mechanical performance

A universal testing machine (CMT-5105, China) was used to measure the flexural and compression strengths of cement mortar at 28 days of curing age. All tests were performed according to the standard BS EN 1015-11:1999 [22]. Three prismatic specimens with dimensions of 160 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm were used for three-point bending tests with a supporting span of 100 mm. Broken half prisms obtained after these were used for compression tests. The compressive strength test was performed with a standard sample holder to ensure a loading area of 40 mm × 40 mm. A servo-hydraulic testing system was used in the displacement control mode to conduct three-point bending tests at a loading rate of 0.1 mm min−1. The values for three specimens in each group were averaged to obtain the experimental result. The loading rate for the compression test was 1 kN s−1. Figure 3 schematically illustrates the loading device used to test the mechanical properties of the specimens.

Loading device used for testing flexural and compressive strengths.

2.3.2 Dry bulk density and capillary water absorption

Dry bulk density (dimensions: 160 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm) and capillary water absorption (dimension: 80 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm) tests on cement mortars were performed in accordance with BS EN 1015-10:1999 [23] and DIN 52617 [24], respectively. Before testing, all samples were dried in a drying oven (105 ± 2°C) for approximately 48 h. After drying, the samples were cooled in an airtight container. For the capillary water absorption test, a layer of paraffin wax was applied on the four vertical surfaces of the sample. The sample was then placed in water at a distance of 10 mm between the height of the water surface and the bottom edge of the specimen.

2.3.3 Mineralogical and micromorphological investigations

The absorption spectra of pure PVA, CNTs and CNT/PVA nanocomplexes were recorded in the wavenumber range of 500–4,000 cm−1 by using a MAUNA-IR 750 infrared spectrometer (Nikolai, USA). Before testing, the samples were ground into powder particles of approximately 45 μm and mixed with KBr. The X-ray spectra of pure PVA, CNTs and CNT/PVA nanocomposites were recorded by using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Germany). Radiation (40 kV, 40 mA; wavelength λ = 1.5406 nm) was sourced from a copper target, and the diffraction angle ranged from 10 to 60°. The Raman spectra of the CNTs and CNT/PVA nanocomplexes were obtained through Raman spectroscopy (HORIBA JobinYvon, HR800, France) with a confocal microscope equipped with a solid-state crystal laser (λ = 532 nm) as an excitation source. Field-emission SEM (FESEM; SU8010, operated at 1.0 and 5.0 kV accelerating voltages) was used to examine CNT/PVA nanocomplexes and cement mortar samples. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed to investigate the thermal stability of the CNTs (TGA55, TA Instruments, USA). All samples were heated from 30 to 800°C in a nitrogen stream at a heating rate of 10°C min−1.

3 Results

3.1 Characterisation of functionalised CNTs

Figure 4a shows the FTIR spectra of p-CNTs, h-CNTs and c-CNTs. FTIR spectroscopy was employed to confirm whether hydroxyl or carboxyl groups were successfully attached to the CNTs. The absorption peaks of p-CNTs mainly appeared at 3,420, 2,905, 1,647, 1,455 and 1,069 cm−1. The absorption peaks observed at 3,420 and 1,647 cm−1 could be attributed to the stretching and bending vibrations of −OH, respectively. The corresponding absorption peaks at 1,455 and 1,069 cm−1 were mainly ascribed to saturated and unsaturated C═C vibrations, respectively, whereas the weak absorption peak at 2,905 cm−1 appeared to be owing to C–H stretching [17,25]. The positions of the FTIR absorption peaks of h-CNTs were similar to those of p-CNTs. However, the peak intensities of h-CNTs at 3,420 and 1,647 cm−1 showed remarkable enhancement, thereby confirming that numerous hydroxyl groups had attached to the h-CNT surfaces. In addition, the enhancement in the intensity of the characteristic peak appearing near 2,905 cm−1 reflects an increase in defects on the CNT surfaces owing to functionalisation. In contrast to those of p-CNTs and h-CNTs, the FTIR spectral profile of the c-CNT sample presented a new characteristic absorption peak at 1,741 cm−1 that represented C═O stretching vibration, indicating the successful attachment of the carboxyl group to c-CNTs via functionalisation. The attachment of abundant functional groups can promote the uniform dispersion of nanoparticles and contribute to enhanced interfacial bonding between CNTs and cement. Figure 4b shows the X-ray diffractograms of p-CNTs, h-CNTs and c-CNTs. In the diffractogram of p-CNTs, two distinct characteristic peaks corresponding to the layer spacing of carbon atoms (d002, representing the degree of graphitisation) and d100 reflection appeared at 2θ = 25.947 and 43.239°, respectively [26]. The positions of the major diffraction peaks of h-CNTs and c-CNTs remained unchanged in contrast to those of p-CNTs. However, the intensities of their (d002) peaks enhanced considerably after functionalisation, likely owing to the insertion of hydroxyl or carboxyl groups that increased the interlayer spacing between the CNTs. Figure 4c shows the Raman spectra of the CNTs. Raman spectroscopy is widely used to analyse the extent of surface defects in carbon nanomaterials [27–29]. The Raman spectra of p-CNTs showed two strong peaks near 1,348 and 1,590 cm−1. The D-band located near 1,348 cm−1 corresponded to the presence of defects in the CNTs and scattering of amorphous carbon impurities, whereas the G-band near 1,590 cm−1 was ascribed to the vibration of C–C bonds in the graphite structure [30]. Defect concentration on the CNTs is proportional to the ratio of D- and G-band intensities (I D/I G) and can be used to quantify the degree of functionalisation [31]. The spectra of p-CNTs showed weak D-band intensity and a low I D/I G value (0.58), indicating a graphite structure with high crystallinity and few defects. Notably, the intensity of the D-band in the Raman spectra of h-CNTs and c-CNTs was higher than that of p-CNTs and their I D/I G values reached 0.68 and 0.63, respectively, suggesting that functionalisation led to an increase in defects on the CNT surfaces. The thermal degradation characteristics of the three types of CNTs were quantified via TGA; the results are shown in Figure 4d. In the first stage (∼30–200°C), the weight loss of the CNTs is mainly due to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water from the pores [32]. The weight loss in the second stage (∼200–460°C) is mainly due to the decomposition of oxygen-containing groups on the CNT surface [33]. At this stage, p-CNTs show almost no weight change (because there are almost no oxygen-containing functional groups on their surface), while h-CNTs show the highest weight loss, indicating that they have the most abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface. The weight loss in the third stage (∼460–800°C) is due to the continuous decomposition of carbon chains in the CNTs [34].

Characterisation of p-CNTs, h-CNTs and c-CNTs. (a) FTIR spectra, (b) XRD spectra, (c) Raman spectra and (d) TGA results.

3.2 Characterisation of CNT/PVA nanocomposites

The interaction between CNTs and PVA molecules was investigated through FTIR spectroscopy. The test results are provided in Figure 5a. In the FTIR spectrum of pure PVA, the characteristic absorption peak appearing near 3,282 cm−1 is owing to the stretching vibration of –OH; that near 2,928 cm−1 is due to the asymmetric/symmetric stretching vibration of –CH2; and those at 1,660, 1,413, 1,088 and 827 cm−1 are attributed to the C═O, C═C, C–O and C–C stretching vibrations in PVA, respectively [35]. The FTIR spectra of the CNT/PVA copolymer and pure PVA showed similar features. However, their peaks had slightly shifted to low wavelengths, indicating the presence of interfacial interactions between the polymer and nanofillers. The same conclusion has been reported by Jia et al. [36]. Moreover, the energy band intensity ratios between 1,088 and 827 cm−1 of the three CNT/PVA copolymers had changed compared with that of pure PVA, reflecting that nanofiller doping altered the crystallinity of PVA chains. We determined the crystalline properties of pure PVA and CNT/PVA copolymers using XRD to understand the effect of nanofiller incorporation on the crystallinity of the polymers further. Figure 5b shows the diffraction scans of pure PVA and the three types of CNT/PVA copolymer samples. Pure PVA exhibits a characteristic peak at 2θ = 19.68°. This peak corresponds to the (110) reflection. This result is consistent with previous findings [37]. The diffraction intensity of the characteristic peak in the crystalline region of PVA considerably reduced with the addition of nanofiller, suggesting that the interaction of randomly distributed CNTs with PVA molecules led to a substantial decrease in crystallinity. Similar findings have been reported by Aslan [38], who found that the peak diffraction intensity associated with the crystalline region of PVA gradually decreases as the CNT content in hybrids increases. Notably, the decrease in the crystallinity of PVA contributes to the increase in strength and elastic modulus and improvement in the chemical and temperature resistance of polymers [39,40]. Comparing the XRD diffraction curves of the three CNT/PVA copolymers reveals that the intensity of the main diffraction peaks of the complexes decreased considerably after doping with functionalised CNTs (h-CNTs and c-CNTs). This result indirectly indicates that the interactions between the functionalised CNTs and PVA molecules strengthened. Figure 5c summarises the Raman spectra of the three types of the PVA-doped CNT samples acquired under 532 nm laser excitation. In the spectra of the CNT/PVA copolymer, the D-band is located near 1,348 cm−1 and the G-band is located near 1,593 cm−1. The G-band of the CNT/PVA copolymer has shifted by 3 cm−1 shift compared with that of pure CNT, further confirming the interaction between CNT and PVA molecules. The I D/I G ratios of p-CNT/PVA, h-CNT/PVA and c-CNT/PVA reached 0.69, 0.80 and 0.79, respectively, which were remarkably higher than those of pure CNTs. This result suggests that the interaction with PVA induces additional surface defects in the CNTs. It also implies that the increase in defect order is more remarkable for functionalised CNTs (especially for h-CNT/PVA nanocomplexes with the highest I D/I G values amongst samples) than for non-functionalised CNTs. These defects will play a key role in the formation of long-range electrostatic and crystal orders in the cement matrix.

Characterisation of pure PVA, p-CNT/PVA, h-CNT/PVA and c-CNT/PVA. (a) FTIR, (b) XRD and (c) Raman spectra.

3.3 Effect of CNT/PVA incorporation on the mechanical properties of cement mortars

The individual and combined effects of three types of CNTs and PVA on the mechanical properties of cement mortar were investigated. The results are shown in Figure 6. The incorporation of the CNTs was beneficial effect to the compressive and flexural strengths of cement mortar with or without functionalisation treatment. This observation was consistent with the nanoenhancement effect observed by Mohsen et al. The CNTs primarily improve the mechanical properties of cement mortar through three mechanisms. First, the CNTs can refine the internal pores of the matrix through the filling effect and improve the compactness of cementitious materials [41]. Second, the CNTs can delay crack extension through the bridging effect [42]. Third, their presence can enhance the hydration rate of cement through the nucleation effect [43]. Notably, the addition of functionalised CNTs led to a more remarkable enhancement in the mechanical properties of cement mortar than those of untreated CNTs. Amongst the CNT–cement mortar samples without PVA, the HCM sample (containing h-CNTs) exhibited the best mechanical properties. The compressive/flexural strengths of the HCM sample increased by 16%/42% and 4%/4% than those of the reference (CM) and NCM (containing p-CNTs), respectively. By contrast, the compressive/flexural strengths of mortar samples containing c-CNTs (CCM) were 14%/40% higher than those of the reference. Notably, the surfaces of functionalised CNTs contain numerous hydrophilic groups (–OH and –COOH), improving their effective dispersion in the cement matrix and enhancing their bonding effect through interfacial interactions with cement hydrates (consistent with the results described in Section 3.1). This interaction increased the efficiency of load transfer between the functionalised CNTs and cement matrix. Therefore, functionalised CNTs more effectively enhanced the mechanical properties of cement mortar than untreated CNTs. In addition, hydroxyl-functionalised CNTs could better enhance the cement matrix than carboxyl-functionalised CNTs likely because the high wettability of the hydroxyl group on their surfaces resulted in high hydrophilicity [44,45]. Therefore, functionalised CNTs with hydrophilic groups, especially OH groups, were recommended for modifying cementitious composites. The addition of PVA alone could slightly increase the compressive/flexural strengths of cement mortars by approximately 12%/16% than those of the reference. This was mainly owing to the pore-filling and crack-bridging effects of the cured PVA film, as reported by Cao et al. [46]. Furthermore, the results displayed in Figure 5 illustrate that the mechanical properties of the cement mortar incorporated with the CNT/PVA complex are superior to those incorporated with the CNTs or PVA alone. In particular, the compressive/flexural strengths of HPCM (with h-CNTs and PVA) were 26%/58%, 22%/28% and 41%/82% higher than those of PCM, HCM and the reference, respectively. The compressive/flexural strengths of NPCM and CPCM increased by 30%/72% and 34%/75%, respectively, than those of the reference. The above-combined effects might be related to the formation of more uniformly distributed nanocomposites and strong interfacial binding bonds in the cement matrix owing to the interaction between the CNTs and PVA. However, the specific strengthening mechanism must be further confirmed through mineralogical and micromorphological observations.

Synergistic effect of CNTs and PVA on the (a) compressive strength and (b) flexural strength of cement mortar.

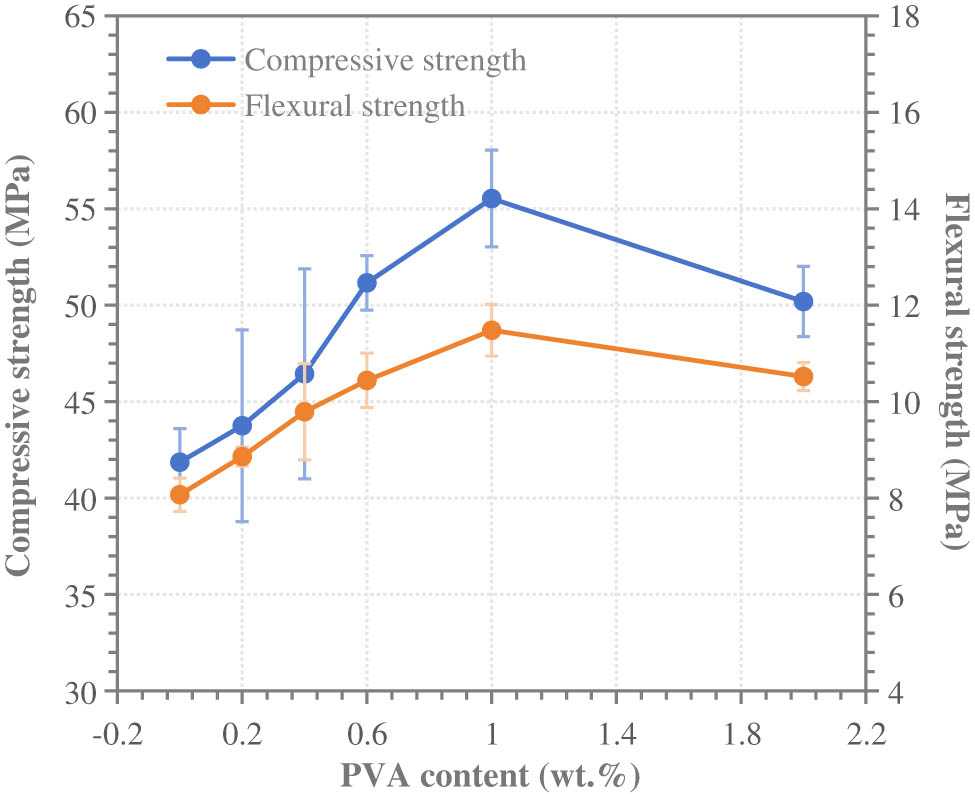

3.4 Effect of the PVA content on the mechanical properties of HPCM

As can be concluded from the above results (Figure 6), the combination of h-CNTs and PVA can maximise the mechanical properties of cement mortars. The mechanical properties of cement mortars with six PVA contents (0–2%) were determined to further investigate the suitable amount of PVA in the HPCM system (containing h-CNTs and PVA, Series 2). The results are presented in Figure 7. As shown in Figure 7, the compressive and flexural strengths of HPCM increased with increasing PVA content until peaking at 1 wt% doping. The compressive/flexural strengths of HPCM4 (containing 1.0 wt% PVA and 0.5 wt% h-CNTs) had improved by 33%/42% relative to those of HPCM0 (containing only 0.5 wt% h-CNTs without PVA). The compressive/flexural strengths of HPCM4 had increased by approximately 53%/101% relative to those of CM; this result is consistent with that reported by Sun et al. [47]. However, when the polymer doping further increased to 2 wt%, the excess PVA reduced the reinforcing effect. The compressive/flexural strengths of HPCM5 had reduced by approximately 10%/8% compared with those of HPCM4. Excessive incorporation of PVA weakens the enhancement effect probably because the thick PVA film formed in the matrix hinders the hydration of cement particles, a finding that has been confirmed in our previous work [48]. The increased air pore content of cementitious composites owing to high PVA usage is another factor that contributes to the reduction in the enhancement effect [49]. Therefore, a reasonable amount of PVA content in h-CNT–cement mortar is suggested to be 0.6–1.0 wt%.

Effect of PVA incorporation on the compressive and flexural strengths of HPCM.

3.5 Effect of PVA content on the dry bulk density of HPCM

The effect of PVA content on the dry bulk density of HPCM is depicted in Figure 8. The dry bulk densities of HPCM with different PVA contents ranged from 2,032 to 2,191 kg m−3. The 28-day dry bulk density of HPCM increased with increasing PVA content until the PVA content reached 1 wt% and then decreased. Amongst samples, HPCM4 (with 1 wt% PVA) exhibited the highest dry bulk density of 2,191 kg m−3. The dry bulk density of HPCM4 increased by 7.8% compared with that of HPCM0 (without PVA). Dry bulk density can reflect the degree of densification inside the cement matrix; this indicates that the incorporation of an appropriate amount of PVA can improve the pore structure of HPCM. Similar findings have been reported by Allahverdi et al. [50], whose results showed that the filling effect of the PVA film formed during cement hydration could result in a matrix with dense internal microstructure and high dry bulk specific gravity. The improvement in the CNT dispersion state in the matrix by PVA incorporation might be another reason for the improved densification of HPCM. The dry bulk density of HPCM5 (with 2 wt% PVA) decreased by approximately 1.5% than that of HPCM4, suggesting that doping with high amounts of PVA would have some negative effects on HPCM densification. This phenomenon can be attributed to two reasons. First, the strong cohesive forces generated by the incorporation of excessive amounts of PVA can negatively affect the workability of fresh mortar and consequently the homogeneity of the mixture, a finding that was confirmed in our previous work [48]. Second, air entrapment caused by the incorporation of large amounts of PVA can reduce the internal densification of the matrix, despite using a certain amount of defoamer. It is well known that improving the internal densification of cementitious materials contributes to strength enhancement. Figure 8b illustrates that a strong correlation with an R 2 value of 0.82/0.91 exists between the 28-day compressive/flexural strengths and dry bulk density of HPCM. In addition, the compressive and flexural strengths of HPCM increase linearly with dry bulk density.

(a) Dry bulk density and (b) its correlation with compressive/flexural strengths of HPCM with different PVA contents.

3.6 Effect of PVA content on the water resistance of HPCM

The water resistance of cementitious materials is related to their porosity and can provide useful information on pore permeability within the specimen. Figure 9 depicts the capillary water absorption exhibited by HPCM samples for different PVA dosages. The experimental results showed that the capillary water absorption curves of HPCM samples with and without PVA comprised two phases: a rapid water absorption phase (phase I) and water absorption saturation phase (phase II). However, the 24-h water absorption rate considerably reduced after the introduction of PVA into HPCM. The incorporation of 1 wt% PVA (HPCM4) was the most effective for improving the water resistance of HPCM. The 24-h water absorption rate of HPCM4 was 3.21 kg m−2, which was 60% lower than that of HPCM0. By contrast, the 24-h water absorption rate of HPCM5 was 25% higher than that of HPCM4. This experimental phenomenon suggests that an appropriate concentration of PVA can effectively improve the water resistance of HPCM. The amount of absorbed water was proportional to the square root of time, and the absorption coefficient could be defined as the slope of the absorption curve during the rapid absorption phase [52]. The water absorption coefficients of HPCM specimens with different PVA contents are shown in Figure 9b. The water absorption coefficients of the PVA-modified mortars (HPCM1–HPCM5) were considerably lower than that of HPCM0. Amongst samples, HPCM4 had the lowest water absorption coefficient of 0.30 kg m−2 min1/2, which was 68% lower than that of HPCM0. The main reasons for the improved water resistance of HPCM samples containing moderate amounts of PVA can be attributed to the following two aspects. First, the uniformly distributed polymer film formed in the cement matrix has a good confinement effect, which significantly reduces the diffusion rate of water in HPCM, a finding consistent with that reported by Kim and Robertson [49]. Second, the relatively homogeneously dispersed nanofillers formed by PVA and h-CNTs filled permeable pores in the cement matrix, leading to improved water resistance of the cement mortar [51].

(a) Capillary water absorption (b) and water absorption coefficient of HPCM with different PVA contents.

3.7 Dispersion studies on h-CNTs in water and PVA latex

As shown in Figure 10, SEM was used to observe the distribution morphology of h-CNTs in pure water and varying concentrations of PVA latex and evaluate the effect of PVA on the dispersion characteristics of the CNTs. Notably, in pure water, h-CNTs tended to entangle and aggregate owing to van der Waals forces, despite undergoing 1.5 h of ultrasonic dispersion. By contrast, the CNTs showed a relatively uniform distribution with increasing PVA doping amounts in the solution, and their surface appeared to be encapsulated by a polymer gel layer. In addition, some profiles of the CNTs isolated from the polymer and several encapsulated fillers could be easily observed in the h-CNT/PVA system. These materials were connected together to form an interpenetrating network. The SEM images clearly showed that PVA could increase the spatial positional barrier between h-CNTs through a coating effect, thereby weakening the van der Waals forces between nanoparticles and improving their dispersion. This phenomenon was similar to that found by Naseem et al. [53].

SEM images of h-CNT dispersion in (a) pure water and (b) 1 wt%, (c) 3 wt% and (d) 7 wt% PVA latex.

Ensuring not only the good dispersion of the nanoparticles but also the formation of long-term stable interfacial bonding with the substrate is necessary to fully use the potential of the CNTs. Figure 11 shows the results of sedimentation tests on h-CNTs in pure water and PVA latex. The initial state of the sedimentation test was directly photographed after 1.5 h of ultrasonic dispersion, and the test solution was then kept undisturbed for continuous measurements. The particles in pure water almost completely precipitated after 5 min. By contrast, the dispersion of the CNTs in PVA latex was more stable. In particular, in 1–3 wt% PVA latex, the nanoparticles remained stably dispersed even after 24 h without coagulation or precipitation. This result fully demonstrated that the appropriate concentration of PVA could effectively maintain the dispersion state of h-CNTs.

Dispersion state of h-CNTs in (a) pure water and (b) 1 wt%, (b) 3 wt% and (d) 7 wt% PVA latex vs time.

3.8 Macromorphology of CNT-modified cement mortars with and without PVA

Figure 12 shows the typical macroscopic morphology of different types of CNT- modified cement mortars with and without PVA incorporation. By comparing these morphologies, we can clarify the effect of PVA doping on the distribution and dispersion stability of nanoparticles in cement mortars. When the CNTs were added alone (with or without functionalisation), black particles aggregated on the surfaces of the moulded specimen (top view) and nanoparticle layering appeared on the side of the specimen. This phenomenon indicates poor bonding between CNTs and cement, with nanoparticles suspending and distributing in a layered manner during vibration and moulding. The top and side views of the PVA-incorporated samples showed a uniform grey–green colour (the original colour of the cement mortar), suggesting that the incorporation of PVA enhanced the adhesion between CNTs and cement and fixed the uniform distribution of the nanoparticles in the cement matrix.

Typical top and side macro views of CNT-modified cement mortars with and without PVA.

3.9 Microstructural analysis

The microscopic morphologies of PCM, HCM and HPCM4 are observed using SEM to deeply understand the internal structural changes in the cement mortar and enhancement mechanism after incorporating PVA, h-CNTs and h-CNT/PVA composites. Representative SEM images are shown in Figure 13. Figure 13a clearly reveals that PVA positively affects the microstructure of cement mortar, given that numerous polymer films are formed to bridge over cracks. Polymer film formation is the main factor affecting the strength enhancement of cement mortars with PVA. However, broken PVA films with irregular shapes are observed in the SEM images, indicating the limiting load transfer capacity of PVA films. Figure 13b shows defects in HCM incorporated with 0.5 wt% h-CNTs after 28 days of curing, wherein a large number of CNTs with smooth surfaces are observed. Figure 13b shows that the agglomeration of h-CNTs occurs because an h-CNT content of 0.5 wt% is excessively high and cannot be uniformly dispersed in the CNT–cement system using only a sonicator. This figure also shows the positive effect of the CNTs on the microstructure of cement mortar, wherein some micropores are filled by h-CNTs. The SEM images of HPCM4 are presented in Figure 13c, showing the interaction between PVA and h-CNTs. The h-CNTs are coated by PVA film, and three-dimensional h-CNT/PVA networks bridge cracks and fill pores, leading to a dense microstructure. Furthermore, the h-CNT/PVA hybrid modifier is uniformly dispersed within the cement mortar. The formation of abundant h-CNT/PVA networks and densified microstructure of HPCM4 are the key factors for the enhancement in mechanical properties. Figure 13c also shows that h-CNTs are embedded within PVA films and form good bonds with the cement matrix. The network structure comprising of h-CNT/PVA acts like long fibres (which are considerably longer than h-CNTs) and can bridge large cracks, thus improving the load transfer capacity of the cement matrix.

SEM images of (a) PCM, (b) HCM and (c) HPCM4.

4 Discussion

The above results show that incorporating of appropriate amounts of PVA and CNTs can remarkably improve the mechanical properties and water resistance of cement mortar. This improvement can be explained on the basis of SEM, XRD, FTIR and Raman results as follows:

CNTs have high aspect ratios that lead to strong van der Waals self-attraction, thereby causing them to disperse uniformly and show a tendency to form agglomerates in pure water [54]. When CNTs are combined with PVA latex, PVA molecules improve the dispersion of the nanoparticles in two ways (as shown in Figure 14a). First, the PVA gel encapsulated on the CNT surface can act as a spatial site barrier and increase the distance between the nanoparticles (this is confirmed in Figure 10). The interaction with PVA molecules introduces additional surface defects in CNTs (especially, functionalised CNTs). These defects help weaken the van der Waals forces between the nanoparticles, thereby further preventing the agglomeration of CNTs. Second, the PVA gel effectively maintains the dispersion stability of the nanoparticles during the mixing of CNT/PVA complexes with cement paste.

As the water content decreases during hydration, PVA gel particles gradually come together to form cured polymer films. These polymer films and CNT particles are in contact with each other, forming a special CNT/PVA network structure. The presence of the CNT/PVA network is advantageous to the performance of cement mortar in two ways (Figure 14b). First, the pure PVA film has insufficient strength to bridge cracks (PVA film breakage can be observed in Figure 13a), whereas the CNT/PVA network containing CNT as a nanoreinforcing agent enhances load transfer between cement matrices more efficiently. In addition, nanoscale CNTs can only bridge small cracks, whereas the long fibre-like structures formed by CNT/PVA can bridge large cracks. Second, the uniformly distributed CNT/PVA network can effectively reduce the number of large pores through the filling effect, thereby improving the compactness of the cement matrix. However, the excessive use of PVA can have a negative impact on the performance of cement mortars, which can be attributed to three main reasons. First, the strong cohesion formed due to the excessive incorporation of PVA negatively affects the workability of the fresh mortar and consequently the homogeneity of the mixture, a finding that has been confirmed in our previous work [48]. Second, the incorporation of excessive PVA can exert a gas-entraining effect and produce numerous macropores, negatively affecting the mortar’s properties [55]. Third, the thick polymer film formed in the matrix by the excessive incorporation of PVA hinders the hydration of cement particles, which is another factor contributing to its reduced effectiveness in improving the properties of cement mortar [48]. A reasonable PVA addition to CNT–cement mortars systems (in the range of 0.6–1 wt%) is recommended on the basis of the results of this study.

Schematic representation of (a) PVA molecules improving the dispersion of CNTs and (b) the synergistic effect of CNTs and PVA on cement mortar.

5 Conclusions

Herein, the microstructures and mechanical properties of cement mortar containing CNT/PVA hybrids are investigated. In addition, the chemical interactions and microstructural characteristics of the CNT/PVA composites and their resulting mortars are determined via FTIR, XRD, Raman and SEM analyses. The conclusions of this work are summarised below:

The compound addition of appropriate amounts of PVA to CNT-modified cement mortars, especially mortars modified with functionalised CNTs, can synergistically improve the mechanical properties of the mortars. The combined use of 0.5 wt% h-CNTs and 1 wt% PVA in the cement matrix provides the best mechanical properties amongst all samples. This strategy increases the compressive/flexural strengths of the modified cement by 53%/101% than those of the reference (without CNTs and PVA).

The incorporation of PVA considerably increases the resistance of the h-CNT-modified cement mortar to water capillary adsorption. This effect is most remarkable at a 1 wt% dosage than at the other dosages.

The presence of PVA improves the dispersion uniformity and interfacial adhesion of CNTs, enabling them to be stably dispersed in the cement matrix.

The SEM analyses revealed that the use of the h-CNT/PVA hybrids leads to the formation of h-CNT/PVA films that bridge cracks and fill pores in the cement matrix, thereby improving the mechanical properties, especially flexural properties, of the cement mortar.

The findings of this study highlight the potential of CNT/PVA (especially h-CNT/PVA) hybrids as additives to improve the mechanical properties of cementitious materials. However, it is worth noting that PVA has poor ageing resistance and low thermal stability; hence, future research efforts should focus on the possible effects of CNT/PVA hybrids on the long-term durability of cementitious materials. In addition, the incorporation of PVA may increase the water and heat sensitivity of cement-based materials. Therefore, further investigations involving dry–wet cycles, freeze–thawing cycles and high temperatures should be conducted.

-

Funding information: The authors thank the projects supported from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52178209 and 51708145), the Key Projects of Universities of Guangdong Province (2019KZDZX2001), the project of Natural Science Research Foundation of Guizhou Province (No. ZK [2021]-283) and Guangzhou Maritime University Scientific Research Initiation Fund (K42022116).

-

Author contribution: Jie Fan: data curation, writing of the original draft, conceptualisation, methodology; Sijie Deng: conceptualisation, writing of the original draft; Gengying Li: conceptualisation, validation, writing – review and editing; Jianxin Li: data curation, investigation; Jinwen Zhang: writing – review and editing, conceptualisation, supervision. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Pan SQ, Dai QY, Safaei B, Qin ZY, Chu FL. Damping characteristics of carbon nanotube reinforced epoxy nanocomposite beams. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021;166:108127.10.1016/j.tws.2021.108127Search in Google Scholar

[2] Konsta-Gdoutos MS, Metaxa ZS, Shah SP. Highly dispersed carbon nanotube reinforced cement based materials. Cem Concr Res. 2010;40(7):1052–9.10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.02.015Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hu Y, Luo DN, Li PH, Li QB, Sun GQ. Fracture toughness enhancement of cement paste with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Constr Build Mater. 2014;70(15):332–8.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.077Search in Google Scholar

[4] Assi L, Alsalman A, Bianco D, Ziehl P, El-Khatib J, Bayat M, et al. Multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) dispersion & mechanical effects in OPC mortar & paste: A review. J Build Eng. 2021;43:102512.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102512Search in Google Scholar

[5] Abu Al-Rub RK, Ashour AI, Tyson BM. On the aspect ratio effect of multi-walled carbon nanotube reinforcements on the mechanical properties of cementitious nanocomposites. Constr Build Mater. 2012;35:647–55.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.086Search in Google Scholar

[6] Fan J, Li GY, Deng SJ, Deng CW, Wang ZK, Zhang ZJ. Effect of carbon nanotube and styrene-acrylic emulsion additives on microstructure and mechanical characteristics of cement paste. Materials. 2020;13:2807.10.3390/ma13122807Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Li Z, Corr DJ, Han BG, Shah SP. Investigating the effect of carbon nanotube on early age hydration of cementitious composites with isothermal calorimetry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Cem Concr Compos. 2020;107(2):103513.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103513Search in Google Scholar

[8] Wang X, Feng D, Shi X, Zhong J. Carbon nanotubes do not provide strong seeding effect for the nucleation of C3S hydration. Mater Struct. 2022;55(7):1–17.10.1617/s11527-022-02008-5Search in Google Scholar

[9] Li GY, Wang PM, Zhao XH. Pressure-sensitive properties and microstructure of carbon nanotube reinforced cement composites. Cem Concr Compos. 2007;29(5):377–82.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[10] Deng SJ, Fan J, Li GY, Zhang M, Li M. Influence of styrene-acrylic emulsion additions on the electrical and self-sensing properties of CNT cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. 2023;403:133172.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133172Search in Google Scholar

[11] Han BG, Yu X, Ou JP. Structures of self-sensing concrete. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014.10.1016/B978-0-12-800517-0.00001-0Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ding SQ, Xiang Y, Ni YQ, Thakur VK, Wang XY, Han BG, et al. In-situ synthesizing carbon nanotubes on cement to develop self-sensing cementitious composites for smart high-speed rail infrastructures. Nano Today. 2022;43:101438.10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101438Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sobolkina A, Mechtcherine V, Khavrus V, Maier D, Mende M, Ritschel M, et al. Dispersion of carbon nanotubes and its influence on the mechanical properties of the cement matrix. Cem Concr Compos. 2012;34(10):1104–13.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.07.008Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jayakumari BY, Swaminathan EN, Partheeban P. A review on characteristics studies on carbon nanotubes-based cement concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2023;367:130344.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130344Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gao FF, Tian W, Wang Z, Wang F. Effect of diameter of multi -walled carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties and microstructure of the cement based materials. Constr Build Mater. 2020;260(6348):120452.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120452Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang BM, Han Y, Liu S. Effect of highly dispersed carbon nanotubes on the flexural toughness of cement-based composites. Constr Build Mater. 2013;46:8–12.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.04.014Search in Google Scholar

[17] Li SJ, Zhang YL, Cheng C, Wei H, Du SG, Yan J. Surface-treated carbon nanotubes in cement composites: Dispersion, mechanical properties and microstructure. Constr Build Mater. 2021;310:125262.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125262Search in Google Scholar

[18] Thong CC, Teo DCL, Ng CK. Application of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in cement-based composite materials: A review of its engineering properties and microstructure behavior. Constr Build Mater. 2016;107:172–80.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.188Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kim J, Robertson R. Effects of polyvinyl alcohol on aggregate paste bond. Adv Cem Based Mater. 1998;8(2):66–76.10.1016/S1065-7355(98)00009-1Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gupta S, Prabha CR, Murthy CN. Functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polyvinyl alcohol membrane coated glassy carbon electrode for efficient enzyme immobilization and glucose sensing. J Environ Chem Eng. 2016;4(4):3734–40.10.1016/j.jece.2016.08.021Search in Google Scholar

[21] Varzaneh AS, Naderi M. Experimental and finite element study to determine the mechanical properties and bond between repair mortars and concrete substrates. J Appl Comput Mech. 2022;8(2):493–509.Search in Google Scholar

[22] BSI. Methods of test for mortar for masonry – Determination of flexural and compressive strength of hardened mortar. EN1015 11:1999 E: British Standards. London, England; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[23] BSI. Determination of dry bulk density of hardened mortar. EN1015 10:1999 E: British Standards. London, England; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[24] DIN. Determination of the water absorption coefficient of construction materials. DIN 52617: German Institute for Standardisation. Berlin, Germany; 1987.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tahermansouri H, Islami F, Gardaneh M, Kiani F. Functionalisation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with thiazole derivative and their influence on SKBR3 and HEK293 cell lines. Mater Technol. 2016;31(7):371–6.10.1179/1753555715Y.0000000062Search in Google Scholar

[26] Min CY, Nie P, Song HJ, Zhang ZZ, Zhao KL. Study of tribological properties of polyimide/graphene oxide nanocomposite films under seawater-lubricated condition. Tribol Int. 2014;80:131–40.10.1016/j.triboint.2014.06.022Search in Google Scholar

[27] Susana A, Edward MG, Luis V, Jazmin C, Ricardo P, Katherine C, et al. Effect of additions of multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNT, MWCNT-COOH and MWCNT-Thiazol) in mechanical compression properties of a cement-based material. Materialia. 2020;11:100739.10.1016/j.mtla.2020.100739Search in Google Scholar

[28] Feng JG, Safaei B, Qin ZY, Chu FL. Nature-inspired energy dissipation sandwich composites reinforced with high-friction graphene. Compos Sci Technol. 2023;233:109925.10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.109925Search in Google Scholar

[29] Feng JG, Safaei B, Qin ZY, Chu FL. Effects of graphene surface morphology on damping properties of epoxy composites. Polymer. 2023;218:126107.10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126107Search in Google Scholar

[30] Azeem M, Saleem MA. Role of electrostatic potential energy in carbon nanotube augmented cement paste matrix. Constr Build Mater. 2019;39:117875.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117875Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zhan MM, Pan GH, Zhou FF, Mi RJ, Shah SP. In situ-grown carbon nanotubes enhanced cement-based materials with multifunctionality. Cem Concr Compos. 2020;108:103518.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103518Search in Google Scholar

[32] Çakir U, Kestel F, Kizilduman BK, Bicil Z, Dogan M. Multi walled carbon nanotubes functionalized by hydroxyl and Schiff base and their hydrogen storage properties. Diam Relat Mater. 2021;120:108604.10.1016/j.diamond.2021.108604Search in Google Scholar

[33] Su XM, Jiang L, Xu ZY, Liu YJ, Yu ZJ, Zhang LL, et al. Synthesis of carboxyl-modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes for efficient adsorption of furfurylamine. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2023;153:105212.10.1016/j.jtice.2023.105212Search in Google Scholar

[34] Gao TT, Yu JG, Zhou Y, Jiang XY. Performance of xanthate-modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes on adsorption of lead ions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017;228(5):172.10.1007/s11270-017-3359-8Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kashyap S, Pratihar SK, Behera SK. Strong and ductile graphene oxide reinforced PVA nanocomposites. J Alloy Compd. 2016;684:254–60.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.05.162Search in Google Scholar

[36] Jia LP, Kou HH, Jiang YM, Yu SJ, Li JJ, Wang CM. Electrochemical deposition semiconductor ZnSe on a new substrate CNTs/PVA and its photoelectrical properties. Electrochim Acta. 2013;107:71–7.10.1016/j.electacta.2013.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[37] Alghunaim NS. Optimization and spectroscopic studies on carbon nanotubes/PVA nanocomposites. Results Phys. 2016;6:456–60.10.1016/j.rinp.2016.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[38] Shameli A, Ameri E. Synthesis of cross-linked PVA membranes embedded with multi-wall carbon nanotubes and their application to esterification of acetic acid with methanol. Chem Eng J. 2017;309:381–96.10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.039Search in Google Scholar

[39] Bhat NV, Nate MM, Kurup MB, Bambole VA, Sabharwal S. Effect of γ-radiation on the structure and morphology of polyvinyl alcohol films. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res. 2005;237(3–4):585–92.10.1016/j.nimb.2005.04.058Search in Google Scholar

[40] Patel AK, Bajpai R, Keller JM. On the crystallinity of PVA/palm leaf biocomposite using DSC and XRD techniques. Microsyst Technol. 2014;20:41–9.10.1007/s00542-013-1882-0Search in Google Scholar

[41] Rafat S, Ankur M. Effect of carbon nanotubes on properties of cement mortars. Constr Build Mater. 2014;50:116–29.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.09.019Search in Google Scholar

[42] Huang J, Rodrigue D, Guo PP. Flexural and compressive strengths of carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious composites as a function of curing time. Constr Build Mater. 2022;318:125996.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125996Search in Google Scholar

[43] Cui K, Lu D, Jiang T, Zhang JX, Jiang ZL, Zhang GD, et al. Understanding the role of carbon nanotubes in low carbon sulfoaluminate cement-based composite. J Clean Prod. 2023;416:137843.10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137843Search in Google Scholar

[44] Oda H, Yamashita A, Minoura S, Okamoto M, Morimoto T. Modification of the oxygen-containing functional group on activated carbon fiber in electrodes of an electric double-layer capacitor. J Power Sources. 2006;158(2):1510–6.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.10.061Search in Google Scholar

[45] Cui X, Han BG, Zheng QF, Yu X, Dong SF, Zhang LQ, et al. Mechanical properties and reinforcing mechanisms of cementitious composites with different types of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2017;103:131–47.10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[46] Cao DT, Gu Y, Jiang LH, Jin WZ, Lyu K, Guo MZ. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on the performance of carbon fixation foam concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2023;390:131775.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131775Search in Google Scholar

[47] Sun GX, Liang R, Lu ZY, Zhang JR, Li ZJ. Mechanism of cement/carbon nanotube composites with enhanced mechanical properties achieved by interfacial strengthening. Constr Build Mater. 2016;115:87–92.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.034Search in Google Scholar

[48] Fan J, Li GY, Deng SJ, Wang ZK. Mechanical properties and microstructure of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) modified cement mortar. Appl Sci. 2019;9(11):2178.10.3390/app9112178Search in Google Scholar

[49] Kim J, Robertson R. Prevention of air void formation in polymer-modified cement mortar by pre-wetting. Cem Concr Res. 1997;27(2):171–6.10.1016/S0008-8846(97)00001-XSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Allahverdi A, Kianpur K, Moghbeli M. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on flexural strength and some important physical properties of Portland cement paste. Iran J Mater Sci Eng. 2010;7(1):1–6.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Wang ZK, Yu J, Li GY, Zhang M, Leung CKY. Corrosion behavior of steel rebar embedded in hybrid CNTs-OH/polyvinyl alcohol modified concrete under accelerated chloride attack. Cem Concr Compos. 2019;100:120–9.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.02.013Search in Google Scholar

[52] Xu JY, Liu Q, Guo HD, Wang MM, Li ZJ, Sun GX. Low melting point alloy modified cement paste with enhanced flexural strength, lower hydration temperature, and improved electrical properties. Compos Part B: Eng. 2022;232:109628.10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.109628Search in Google Scholar

[53] Naseem Z, Shamsaei E, Sagoe-Crentsil K, Duan WH. Antifoaming effect of graphene oxide nanosheets in polymer-modified cement composites for enhanced microstructure and mechanical performance. Cem Concr Res. 2022;158:106843.10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.106843Search in Google Scholar

[54] Sudip B, Pujan S, Prasanta S. Electro-mechanical response of stretchable pdms composites with a hybrid filler system. Facta Univ-Ser Mech Eng. 2023;21(1):51–61.10.22190/FUME221205002KSearch in Google Scholar

[55] Naaman R. Structure and properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)-modified mortar and concrete. Cem Concr Res. 1999;29:407–15.10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00246-4Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications