Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

-

Asmawi Nazrin

, Mohamed Yusoff Mohd Zuhri

Abstract

In this study, sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose (SPCNC)-reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch (TPS) was blended with poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in order to prioritize the biodegradation feature while offsetting individual polymer limitation. Prior to melt blending process, SPCNC was dispersed through sonication in advance of starch gelatinization which was later casted into petri dishes. PLA and TPS were melt blended into five different ratios using Brabender mixer followed by compression molding. Soil degradation (4 months) and water uptake (4 weeks) tests were conducted to evaluate the physical stability of PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites. Based on Fickian law, the diffusion curve and coefficient of diffusion for seawater, river water, and sewer water were calculated. The flammability and limiting oxygen index (LOI) tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM D635 and ASTM D2863, respectively. For PLA60TPS40 (40% TPS), significant reduction (46–69%) was recorded in maximum water uptake in all mediums, while soil degradation rate experienced insignificant increment (7.92%) for PLA70TPS30 (30% TPS) owing to the reinforcement of SPCNC through the well-dispersed TPS within PLA. Meanwhile, the flammability rates and LOI values for PLA40TPS60 and PLA60TPS40 indicated flammable material properties.

1 Introduction

Non-biodegradable petrochemical-based plastics are polluting the environment at a concerning rate instigating long term environmental, economic, and waste management problems [1]. The effort to dispose and recycle plastic wastes are inefficient due to poor management, high recycling cost, and difficulties in polymer separation, which end up either in landfills or the ocean [2]. Finite petroleum resources coupled with the rising environmental issues had prompted scientists and material engineers to shift toward biodegradable food packaging materials derived from bioresources as an alternative replacement for current conventional plastics [3]. PLA is a promising biodegradable polymer synthesized from bioresources with unique features such as glossy appearance, decent transparency, good processability, and high rigidity [4]. However, PLA exhibits slow degradation rate in soil and little to no degradation in seawater [5]. In soil, PLA films with thickness of 0.2 mm exhibited no mass loss at 25 and 37°C after 1 year, but 40% mass loss was detected at 45°C after 8 weeks [2]. PLA showed no mass loss in seawater and fresh water under simulated conditions over 1 year. In sewage sludge, the biological degradation (CO2 release) of PLA was 43% at 37°C after 277 days [6] and 75% at 55°C after 75 days [7].

In an effort to solve the marine plastic waste pollution, starch is incorporated to induce biodegradation, while reducing the raw material cost of PLA. Starch had piqued the interest of fellow researchers in manufacturing of food packaging plastics due to their promising features such as colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, and biodegradable properties [8]. Several modifications have been carried out in order to improve their mechanical strength, water barrier, and thermal properties such as plasticizers addition, fiber reinforcement, and polymer blending. Sugar palm starch (SPS) like most starches has received considerable research attention in developing biodegradable food packaging materials. Its high amylose content (37%) was reported as a good film-forming material in producing starch biopolymer films comparable to other commercial starches [9]. Sanyang et al. [10] reported that SPS films plasticized by sorbitol achieved 28.35 MPa in tensile strength, while the one plasticized by glycerol reached 61.63% in elongation at break. Prominently, nanosized fibers have gained tremendous attraction due to their outstanding features, such as excellent mechanical properties, light weight, low density, high surface area (100 m2/g), and high aspect ratio of 100 compared to other commercial fibers [11]. Ilyas et al. [12] reported SPS biocomposite film reinforced with 0.5% sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose (SPCNC) which demonstrated an improvement in both tensile strength (140%) and water vapor permeability (19.94%). However, starch-based biocomposite deteriorates its mechanical strength easily upon prolonged exposure to moisture. Hence, blending with hydrophobic polymer such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA) helps to offset the low water barrier properties of starch-based biocomposite. The incorporation of low-cost starch filler will inevitably deteriorate mechanical strength, but at the same time induce water absorption for microorganism inhabitation to enhance degradability in aqueous environments [13].

In this context, PLA is blended with SPCNC-reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch (TPS) in an effort to overcome individual polymer limitations and achieve desirable material properties for intended application. To date, only limited research has been conducted on the water uptake within seawater, river water, and sewer water. To the best of authors’ knowledge, there have been no study performed on water uptake of seawater, river water, and sewer water for polymer blend composites of PLA with SPCNC-reinforced TPS. TPS and SPCNC have similar botanical origin with similar chemical composition forming good compatibility between fibers and matrixes. In the present study, PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites were fabricated into five different ratios and the capabilities of each composition was evaluated based on their flammability behavior, soil degradation behavior as well as water uptake of seawater, river water, and sewer water.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

SPS in the form of mixture of starch and woody fibers extracted from the trunk of sugar palm tree was purchased from Hafiz Adha Enterprise at Kampung Kuala Jempol, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. PLA (NatureWork 2003D), glycerol, and sorbitol were bought from Mecha Solve Engineering, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. SPCNC derived from sugar palm fibers which are naturally entwined at the outer part of sugar palm tree was provided by Laboratory of Biocomposite Technology, Institute of Tropical Forestry and Forest Products, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia. Table 1 shows the physical properties of SPCNC and their values.

Physical properties of SPCNC and their values

| Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.05 |

| Diameter (nm) | 9 |

| Surface area (m2/g) | 14.47 |

| Pore volume (cm3/g) | 0.226 |

| Moisture content (wt%) | 17.90 |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 23164.7 |

| Degree of crystallinity (%) | 85.9 |

| Degree of polymerization | 142.86 |

2.2 Extraction and preparation of SPS

SPS was extracted from the trunk of sugar palm trees located at Jempol, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Initially, the mixture of starch and woody fibers were transferred into a bucket and left out for 1 day for the sedimentation of starch while less dense fibers floated to the surface. The floating fibers were removed and a strainer cloth was used to filter finer size woody fiber residue mixed with starch. Next the wet starch was spread evenly onto a plastic film and left in open air for a moment. Then, the starch was transferred into an air circulating oven at 120°C for 24 h to obtain starch powder. The extraction method was adapted from Sahari et al. [14].

2.3 Fabrication of SPCNC-reinforced TPS/PLA blend bionanocomposite sheets

Solution casting method was used to fabricate TPS. Initially, 1,000 mL of distilled water was filled in a beaker and 0.5 g SPCNC (0.5%), 15 g of both glycerol (15%) and sorbitol (15%) were added. Sonication method was applied for 15 min to agitate SPCNC to ensure discontinuous particles distribution and uniform dispersion in the liquid. Then, the beaker was transferred into a water bath with a temperature of 80°C. Progressively, 100 g SPS was added into the mixture, while maintaining continuous stirring for 30–45 min until a semi-fluid consistency was attained. The gelatinized starch was transferred into glass petri dishes and placed in an oven for drying at 60°C for 24 h. Later, the dried-up gelatinized starch formed thin TPS films and were crushed into granule-size to ease the melt blending process. PLA granules and crushed TPS films were melt blended using Brabender Plastograph (Model 815651, Brabender GmbH & Co. KG, Duisburg, Germany) at 170°C for 13 min with a rotor speed of 50 rpm. PLA and TPS were blended into five different ratios of 20:80, 40:60, 60:40, 70:30, and 80:20. Once again, the blend bionanocomposites were crushed into granule-size before being hot pressed (Technovation, Selangor, Malaysia) at 170°C for 17 min into 150 mm × 150 mm × 3 mm sheet. Table 2 shows the composition of PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites. Figure 1 shows the overall preparation of PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites.

Various composition of PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites

| Designation | PLA (%) | TPS (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PLA20TPS80 | 20 | 80 |

| PLA40TPS60 | 40 | 60 |

| PLA60TPS40 | 60 | 40 |

| PLA70TPS30 | 70 | 30 |

| PLA80TPS20 | 80 | 20 |

| PLA100 | 100 | 0 |

Schematic diagram of the preparation of PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites.

2.4 Flammability test

Flammability test was conducted in accordance with ASTM D635 in a horizontal position. Prior to the test, samples (125 mm × 13 mm × 3 mm) were placed in an oven for 24 h at 100°C to remove remaining moisture. Two reference lines were drawn at distances of 25 mm and 100 mm as starting and finishing marks. Then, the sample was clamped horizontally at the end side leaving both reference lines visible using retort stand. The sample was lit at the other end side and as soon as the flame reached a distance of 25 mm, the timer was started. The test was carried out in triplicate and time taken for the flame to reach 100 mm was recorded. The burning rate of the sample can be calculated using equation (1):

where V is the linear burning rate (mm/min), L is the burnt length (mm), and t is the time (min)

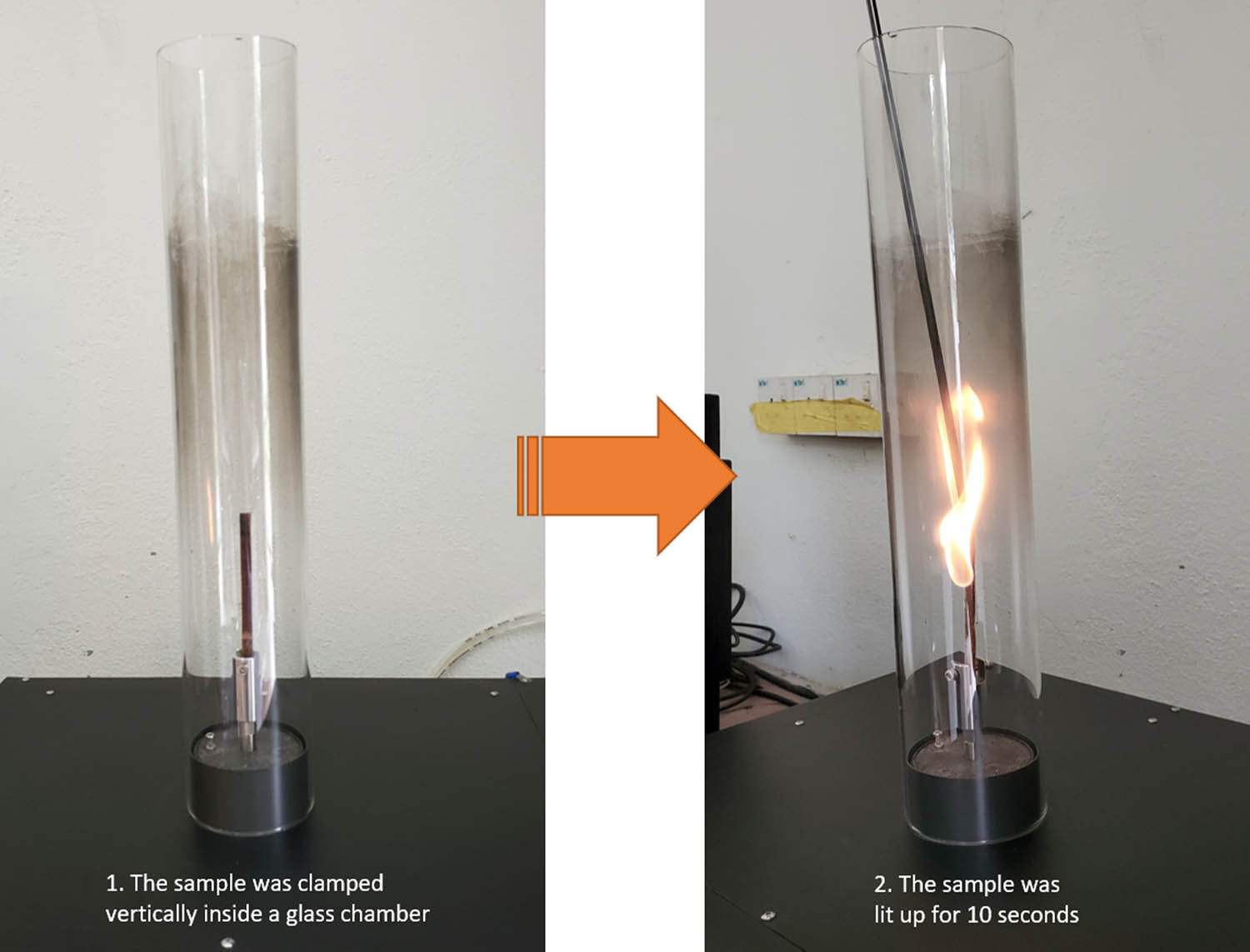

2.5 Limiting oxygen index (LOI)

The LOI test was conducted in accordance with ASTM D2863 to measure the lowest oxygen concentration for combustion of a sample. Prior to the test, samples (100 mm × 6.5 mm × 3 mm) were placed in an oven for 24 h at 100°C to remove remaining moisture. The sample was clamped vertically in the glass chamber and lit up for 10 s until ignition. Figure 2 shows the experimental setup of LOI test. The test was carried out with ten replicate samples. The LOI value can be calculated using equation (2):

where Cf is the final value of oxygen concentration in vol% for the previous five measurements, d is the interval difference in vol% between oxygen concentration levels (0.2 vol%), and k is the factor derived from the experimental value.

The experimental setup of LOI test.

2.6 Biodegradation in compost soil

Six samples (15 mm × 15 mm × 3 mm) were buried in polybags containing characterized soil at 10 cm depth, which was moistened daily with water. Plastic mesh was used to wrap the samples before burying into the soil to facilitate removal of the degraded samples while maintaining the access of moisture and microorganism. The physiochemical properties of the soil were pH: 6; organic carbon: 35%; total nitrogen: 1.3%; phosphorus: 1,750 ppm; potassium: 1,750 ppm; magnesium: 2,500 ppm; and calcium: 4,500 ppm. Prior to testing, samples were dried at 100°C for 24 h and weighed to obtain the initial weight, W i. Four sets of experiments were made for predetermined 1 month interval for 4 months. Samples were taken from the soil at specified intervals and gently cleaned with distilled water to remove impurities. Finally, samples were left to dry at 100°C for 24 h and weighed to obtain the final weight, W f. The test was done in triplicate and the average values were taken. The weight loss, W l can be calculated using equation (3):

2.7 Water uptake

Total of six samples (20 mm × 15 mm × 3 mm) were immersed in three different conditions which were seawater, river water, and sewer water. Table 3 shows the origin sources of the three different mediums used in this study. Prior to testing, samples were dried at 100°C for 24 h and weighed to obtain the initial weight, W 0. After selected immersion periods, the samples were removed, washed, wiped, and weighed (W t ) using OHAUS balance with a precision of 1 mg at room temperature (25°C and RH 25%). The test was done in triplicate and the average values were taken. The percentage of weight gain at given time M t can be calculated using equation (4):

The test was done in triplicate and the maximum moisture absorption, M max, was calculated as an average value with very little variation in water uptake. The weight gained from moisture absorption can be modeled in terms of two parameters, the diffusion coefficient D and M max, and are given by Fick’s first law in equation (5):

where h is the thickness of the sample and D can be calculated using the initial linear portion of the absorption curve. For M t /M max ≤ 0.5, the function M t = f(√t) is linear and the Fickian diffusion coefficient D is determined by equation (6):

As this equation is commonly used in square specimen dimension, a correction factor is required to interpret for the finite length l and width w of the sample compared to its thickness h using equation (7):

Origin sources of seawater, river water, and sewer water

| Medium | Source (coordinate) |

|---|---|

| Seawater | Shoreline of Malacca Strait |

| (2°54′54.2″N 101°19′15.9″E) | |

| River water | Kuyoh river of pale brown water |

| (3°00′51.6″N 101°43′07.7″E) | |

| Sewer water | Seri Serdang town with less than 10 building blocks (3°00′35.2″N 101°42′49.2″E) |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Flammability test

The flammability behavior of a material are attributed to its chemical composition and interfacial bonding formed within the material itself [15]. The chemical composition of the plastic cause ease in ignition when exposed to sufficient heat in the presence of oxygen. In an effort to minimize the flammability of plastic, implementation of additional flame retardant materials or substances had been utilized. Table 4 shows the effect of blending TPS with PLA at various ratios toward their burning rate and behavior. As observed, the introduction of TPS into PLA induced flammability in the blend bionanocomposite samples but only for PLA60TPS40 and PLA40TPS60, while the flame for PLA80TPS20, PLA70TPS30, and PLA20TPS80 quickly extinguished before reaching the first 25 mm reference line. PLA60TPS40 and PLA40TPS60 continuously burned till 100 mm reference line indicating highly flammable properties. This is mainly caused by the incorporated plasticizers in fabricating TPS which are glycerol and sorbitol. Glycerol and sorbitol are known to be flammable substances with the flash point of 176 and above 300°C, respectively [16]. The higher concentration of plasticizers in TPS seemed to greatly affect the burning rate as can be seen for PLA40TPS60 (16.39 mm/min) which exhibited faster burning rate compared to PLA60TPS40 (15.29 mm/min). This occurrence can be associated with the migration of glycerol from TPS into PLA due to its lower molecular weight which activated the flammability in the PLA phase. Various authors [17,18,19] reported that during the melt mixing process, lower molecular weight of glycerol (92 g/mol) tends to migrate from TPS to PLA matrix, while higher molecular weight sorbitol (182 g/mol) stayed within TPS. Sorbitol is responsible for decreasing the particle size and promoted a fine dispersion of TPS within PLA phase resulting in homogeneous composition. The uniform distribution of TPS within PLA triggered a continuous combustion of the samples. Even so, the burning rate of PLA40TPS60 and PLA60TPS40 were less than 40 mm/min which classified as HB in UL94 rating. In other words, they are considered to be the least flame retardant material that required improvement in flammability features. Due to this fact, some researchers [20,21] substituted glycerol with glycerol phosphate with the intention of increasing the flame retardant properties of starch-based polymer blend.

Burning rate, UL94 rating, and burning behavior of pristine PLA and PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites

| Sample | Burning rate | Burning behavior | LOI (vol%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA20TPS80 | Inflammable | Partially burned, slow dripping, moderate smoke, and low flame | — |

| PLA40TPS60 | 16.39 mm/min (HB) | Fully burned, fast dripping, less smoke, and low flame | 19.2% |

| PLA60TPS40 | 15.29 mm/min (HB) | Fully burned, fast dripping, less smoke, and low flame | 18.8% |

| PLA70TPS30 | Inflammable | Partially burned, moderate dripping, moderate smoke, and moderate flame | — |

| PLA80TPS20 | Inflammable | Partially burned, moderate dripping, moderate smoke, and moderate flame | — |

| PLA100 | Inflammable | Partially burned, moderate dripping, moderate smoke, and moderate flame | — |

According to our previous paper [22], the scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of PLA60TPS40 displayed smooth surface morphology indicating good interfacial bonding, while some visible agglomeration spots of TPS were detected for PLA40TPS60 and PLA20TPS80. All these samples showed a constant dripping of the melted material. Meanwhile, PLA80TPS20 and PLA70TPS30 displayed some microcracks and voids indicating poor interfacial bonding between PLA and TPS. It was observed that when these two samples lit up, fragment of material was detached rather than a consistent dripping. The minor proportion of TPS within the samples melted quickly as compared to less flammable PLA phase which led to the detachment of PLA fragment with the assistance of spread microcracks. Based on those behaviors, it was verified that PLA60TPS40 and PLA40TPS60 have the optimal plasticizers concentration to promote the flammability of PLA and improve the dispersion of TPS into PLA. Nazrin et al. [19] conducted Dynamic Mechanical Analysis and reported a significant increment in storage modulus for PLA60TPS40 (53.5%), while trivial changes were recorded for PLA70TPS30 (10%) and PLA80TPS20 (0.6%) due to the insufficient glycerol migration to promote the chain mobility responsible in improving the storage modulus.

Based on Table 4, PLA40TPS60 (19.2%) had a slightly higher LOI value compared to PLA60TPS40 (18.8%). Bocz et al. [20] recorded the LOI value of 22% for TPS plasticized with 25% glycerol and 21% for PLA/TPS plasticized with 5% glycerol. This verified that the higher content of TPS required higher oxygen concentration for combustion although higher concentration of glycerol was incorporated. This might be the reason as why PLA20TPS80 was not flammable as PLA40TPS60 and PLA60TPS40 even though it undoubtedly consisted the highest glycerol concentration among all the blend bionanocomposite samples. Relatively higher TPS content indicated higher concentration of SPCNC within the samples. Supposedly, lignin content within cellulose generated char formulation which helps to hinder flame propagation [21]. However, the removal of lignin in order to produce low water retention of SPCNC might have induced the flammability rate for sample with higher TPS content [23]. However, the effect of glycerol migration overwhelms the SPCNC reinforcement.

3.2 Soil burial: weight loss

The calculation of weight loss during soil burial test was done by observing the biodegradation behaviors of a material. The weight loss of the blend bionanocomposites is due to consumption of starch by microorganisms. Figure 3 shows an increasing trend of the percentage of weight loss as the addition of TPS was increased within the blend. In the first 30 days, all blend bionanocomposites went through active degradation process and for the next 90 days, lower degradation rates were recorded. Amylopectin residing within the blend consists of branched hydroxylated chains, which promote hydration and water diffusion resulting in microorganisms growth [24]. The reduction in degradation rate can be associated with the adaptation of microorganisms to the materials after colonization. Ohkita and Lee [25] fabricated PLA/TPS (70:30 and 50:50) blend composites with and without the incorporation of lysine diisocyanate (LDI) as a coupling agent and recorded that the samples with LDI had a steady weight loss for 1 month, while those without LDI had a significant degradation rate for 1 week. LDI acts as a coupling agent by removing the hydroxyl groups of PLA and TPS, thus lowering the accessibility for microorganisms’ invasion.

Weight loss against time of PLA100 and PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites.

In similar case, Ayana et al. [26] found that priorly dispersed montmorillonite clays (1 PHR) during starch gelatinization and later melt mixed with PLA (PLA/TPS, 40:60) promoted the compatibility between immiscible polymer blends by reducing the size distribution of the PLA in the starch matrix. The exfoliation of clay nanolayers established a tortuous path preventing further water penetration into the PLA/TPS blend nanocomposites. The dispersion of SPCNC within TPS for all the blend bionanocomposites seemed to play the exact role as nanoclays to establish tortuous path hindering water penetration for microorganisms to inhabit [27]; though, this mechanism can work only if homogenous combination between PLA and TPS was achieved. Within the first 30 days, a minor increase in weight loss was recorded between PLA70TPS30 (20.92%) and PLA60TPS40 (22.72%). In relation to flammability results, the homogenous composition achieved at PLA60TPS40 seemed to prevent rapid degradation of TPS phase. Taking into account the dispersion of SPCNC, the water penetration into the sample was reduced resulting in lower microorganism inhabitation. Other samples experienced significant increase as TPS content was increased. At 60% of TPS content (PLA40TPS60) (44.45%), the weight loss increased significantly as compared to PLA60TPS40 (20.92%). The agglomeration spots presented in PLA40TPS60 and PLA20TPS80 as mentioned in Section 3.1 acted as an active spot for microorganisms’ inhabitation which led to rapid degradation. The physical condition of these two samples were observed to be completely shrunk into smaller pieces after 24 h of oven drying process. Meanwhile, PLA60TPS40, PLA70TPS30, and PLA80TPS20 seemed to maintain their physical shape with some visible cavities on the surface due to degradation of the TPS.

PLA100 did not seem to experience degradation process as no weight loss was recorded. Another factor which might be affecting the degradation rate was the plasticizers used. Sanyang et al. [10] reported that sorbitol-plasticized TPS had lower water vapor transmission rate compared to glycerol-plasticized TPS. The migration of glycerol from TPS into PLA led to a lower moisture content for all the samples. Lower moisture content caused compact hydrogen bonds interaction between starch and water suggesting that a high number of free hydroxyl groups of the starch are available to interact with the active sites of sorbitol. Hence, the chances of sorbitol interacting with water molecules become lower.

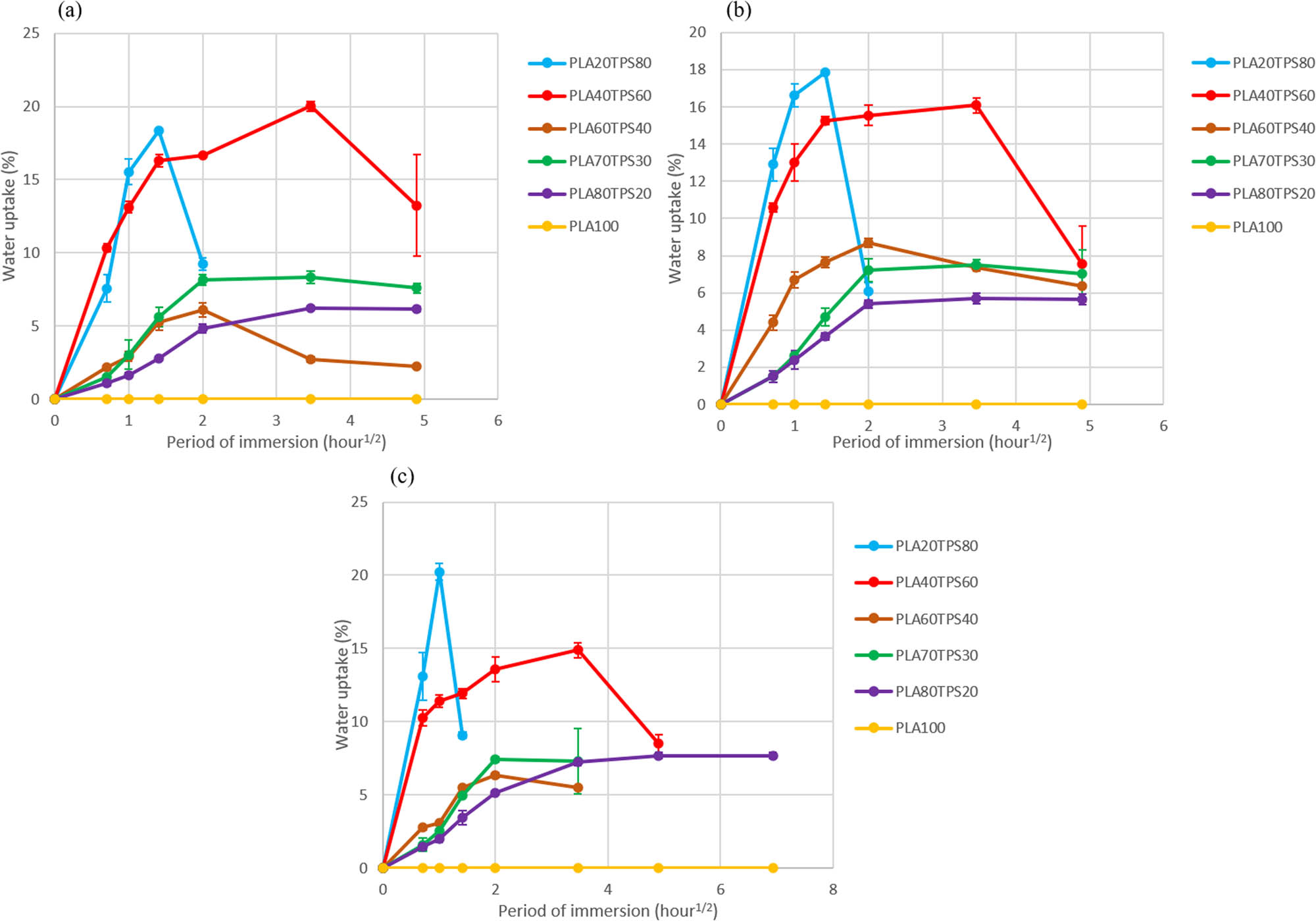

3.3 Water uptake

All bionanocomposite samples including pristine PLA (PLA100) were immersed in three type of liquid medium which are seawater, river water, and sewer waste water. The water uptake of all bionanocomposite samples is solely contributed by TPS content as PLA is well-known for its strong hydrophobic nature. Based on Table 5, the reduction in TPS content decreases the equilibrium water content of the blend bionanocomposites regardless of the medium used. The sample with highest TPS content (PLA20TPS80) had the highest value of equilibrium water content. There are several factors that influenced the water absorption of a polymer composite which are diffusivity, exposed surface area, permeability, temperature, surface protection, fiber content, and orientation [12]. In this study, temperature was kept constant at room temperature (25 ± 1°C) and uniform exposed surface area through fixed sample size with no incorporation of surface protection was considered. As the composition of each sample was different, fiber content and orientation are expected to be different. The differences between the orientation can be observed from the SEM analysis of the previous paper [22], where slight agglomeration spots can be observed within samples that have TPS content more than 40% (PLA20TPS80 and PLA40TPS60), while microcracks and voids are presented within samples that have TPS content lower than 40% (PLA70TPS30 and PLA80TPS20).

Equilibrium water content (M max), coefficient of diffusion (D), and corrected coefficient of diffusion (Dc) of pristine PLA and PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites within seawater, river water, and sewer water

| Medium | Seawater | River water | Sewer water | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | M max (%) | D·10−6 (cm2/s) | Dc·10−6 (cm2/s) | M max (%) | D·10−6 (cm2/s) | Dc·10−6 (cm2/s) | M max (%) | D·10−6 (cm2/s) | Dc·10−6 (cm2/s) |

| PLA20TPS80 | 18.37 | 2.45 | 1.35 | 17.87 | 2.45 | 1.35 | 20.24 | 4.91 | 2.69 |

| PLA40TPS60 | 20.02 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 16.08 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 14.88 | 0.41 | 0.22 |

| PLA60TPS40 | 6.08 | 1.23 | 0.67 | 8.68 | 1.23 | 0.67 | 6.34 | 1.23 | 0.67 |

| PLA70TPS30 | 8.35 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 7.51 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 7.44 | 1.23 | 0.67 |

| PLA80TPS20 | 6.22 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 5.7 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 7.68 | 0.21 | 0.11 |

| PLA100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Strangely, PLA40TPS60 has a lower coefficient of diffusion value compared to PLA60TPS40 within all mediums. This might be due to the high concentration of SPCNC within the sample which might hinder the diffusivity of the water molecules. Ilyas et al. [12] reported that the incorporation of 0.5% SPCNC into sugar palm starch biocomposite films reduced the equilibrium water sorption by 16%. The decrement in the coefficient of diffusion for PLA40TPS60 can be attributed to the high crystallization of SPCNC [28]. For PLA60TPS40, the sample has a better compatibility between PLA and TPS, thus promoting uniform distribution of water molecules in TPS well-dispersed within PLA. This led to quicker diffusivity of water molecules into the samples but at the same time reducing equilibrium water content [27]. Apart from that, PLA20TPS80 displayed higher coefficient of diffusion in sewer water compared to seawater and river water. It is speculated that the static condition of sewer water might be the cause of the high coefficient of diffusion. Continuous flow of seawater and river water stimulate the circulation of foreign particles while procuring them as compared to sewer water which remained static.

The movement of water molecules into polymer composites are based on three mechanisms [29]: diffusion, capillary movement, and transport of water molecules. Diffusion occurs inside the free volume (micro gaps) between polymer chains. Capillary transport occurs through capillary connection through the gaps and cracks at the interface between fibers and continuous phase. Transport of water molecules occurs due to the swelling of fiber within the matrix. Based on Figure 4, sample with highest TPS content reached equilibrium water uptake quickly compared with lower content of TPS regardless of the medium used. The highest value of equilibrium water uptake did not exceed 20% for all samples, while for PLA60TPS40, a significant drop of equilibrium water content can be observed within all medium of immersion with seawater having the lowest value which is 6.08%. It was reported [30] that the seawater contained various minerals (up to 3.5%) which limited the diffusion of water molecules into the polymer composite materials. Based on the previous paper [22], water uptake of the PLA60TPS40 within distilled water reached up to 25% for only 2 h of immersion period. The absence of components such as minerals facilitate the diffusivity of water molecules. In the seawater medium, it is observed that PLA40TPS60 (20.02%) had a slightly higher equilibrium water content value compared to PLA20TPS80 (18.37%). Since the coefficient of diffusion for PLA40TPS60 within all mediums were the same, the difference was insignificant considering the large standard deviation displayed in Figure 4. It was suspected that some replicates might have higher TPS content due to the poor compatibility resulting in extra agglomeration spots. As soon as PLA20TPS80 and PLA40TPS60 reached equilibrium water content, the water uptake dropped rapidly. It was observed that these two samples experienced defragmentation due to the higher TPS content validating the poor physical stability correlated with the results from soil degradation.

The water uptake (%) against period of immersion (hour1/2) of PLA100 and PLA/TPS blend bionanocomposites within: (a) seawater, (b) river water, and (c) sewer water.

4 Conclusion

In a nutshell, the reinforcement of SPCNC within the blend bionanocomposites could only be optimized if TPS is well-dispersed within PLA phase. In order to achieve such condition, a harmonize ratio between PLA and TPS must be identified. The maximum water uptake within seawater, river water, and sewer water decreased as TPS content decreased, but only PLA60TPS40 displayed a significant reduction compared to other samples. However, the coefficient of diffusion recorded a higher value for PLA60TPS40 compared to PLA40TPS60 and PLA70TPS30 owing to uniform distribution of water molecules within the well dispersed TPS within PLA leading to a quicker diffusivity but reducing maximum water uptake. The soil degradation rate also showed minor change between PLA70TPS30 and PLA60TPS40 compared to PLA60TPS40 and PLA40TPS60 due to the tortuous path of SPCNC hindering water penetration for microorganisms to inhabit. PLA60TPS40 and PLA40TPS60 demonstrated burning rate lower than 40 mm/min which were classified as HB in UL94 rating and considered as least flame retardant material. Meanwhile, the low LOI values of PLA40TPS60 (19.2%) and PLA60TPS40 (18.8%) indicated that they were highly flammable materials within atmospheric air. In food packaging application that prioritize biodegradability and cheap material, PLA60TPS40 demonstrated tolerable physical stability but required improvement in flame retardant features.

-

Funding information: The authors wish to thank Universiti Putra Malaysia for the financial support through Inisiatif Pemerkasaan Penerbitan Jurnal Tahun 2020 (Vot number: 9044033) and Geran Putra Berimpak (GPB), UPM/800-3/3/1/GPB/2019/9679800.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Castro-Aguirre E, Iñiguez-Franco F, Samsudin H, Fang X, Auras R. Poly(lactic acid) – mass production, processing, industrial applications, and end of life. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. Dec. 2016;107:333–66. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.03.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kliem S, Kreutzbruck M, Bonten C. Review on the biological degradation of polymers in various environments. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(20):1–18. 10.3390/ma13204586.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Nurazzi NM, Asyraf MRM, Khalina A, Abdullah N, Aisyah HA, Ayu Rafiqah S, et al. A review on natural fiber reinforced polymer composite for bullet proof and ballistic applications. Polymers (Basel). Feb. 2021;13(4):646. 10.3390/polym13040646.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Asim M, Siengchin S. Accelerated weathering and soil burial effect on biodegradability, colour and textureof coir/pineapple leaf fibres/PLA biocomposites. Polymers (Basel). Feb. 2020;12(2):458. 10.3390/polym12020458.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Wang GX, Huang D, Ji JH, Völker C, Wurm FR. Seawater-degradable polymers – fighting the marine plastic pollution. Adv Sci. 2021;8(1):1–26. 10.1002/advs.202001121.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Yagi H, Ninomiya F, Funabashi M, Kunioka M. Mesophilic anaerobic biodegradation test and analysis of eubacteria and archaea involved in anaerobic biodegradation of four specified biodegradable polyesters. Polym Degrad Stab. 2014;110:278–83. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.08.031.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Yagi H, Ninomiya F, Funabashi M, Kunioka M. Thermophilic anaerobic biodegradation test and analysis of eubacteria involved in anaerobic biodegradation of four specified biodegradable polyesters. Polym Degrad Stab. 2013;98(6):1182–7. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.03.010.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Hazrati KZ, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM, Jumaidin R. Effect of plasticizers on physical, thermal, and tensile properties of thermoplastic films based on Dioscorea hispida starch. Int J Biol Macromol. Jun. 2021;185:1–33. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ilyas RA, Sapuan SM, Atiqah A, Ibrahim R, Abral H, Ishak MR, et al. Sugar palm (Arenga pinnata [Wurmb.] Merr) starch films containing sugar palm nanofibrillated cellulose as reinforcement: water barrier properties. Polym Compos. July 2019;121:1–9. 10.1002/pc.25379.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sanyang ML, Sapuan SM, Jawaid M, Ishak MR, Sahari J. Effect of plasticizer type and concentration on tensile, thermal and barrier properties of biodegradable films based on sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) starch. Polymers (Basel). 2015;7(6):1106–24. 10.3390/polym7061106.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Norrrahim MNF, Ariffin H, Yasim-Anuar TAT, Hassan MA, Ibrahim NA, Yunus WMZW, et al. Performance evaluation of cellulose nanofiber with residual hemicellulose as a nanofiller in polypropylene-based nanocomposite. Polymers (Basel). Mar. 2021;13(7):1064. 10.3390/polym13071064.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Ilyas RA, Sapuan SM, Ishak MR, Zainudin ES. Development and characterization of sugar palm nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced sugar palm starch bionanocomposites. Carbohydr Polym. Dec. 2018;202:186–202. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Huang D, Hu ZD, Liu TY, Lu B, Zhen ZC, Wang GX, et al. Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA. E-Polymers. 2020;20(1):759–72. 10.1515/epoly-2020-0071.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Sahari J, Sapuan SM, Zainudin ES, Maleque MA. Thermo-mechanical behaviors of thermoplastic starch derived from sugar palm tree (Arenga pinnata). Carbohydr Polym. Feb. 2013;92(2):1711–6. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ratnavathi CV, Patil JV, Chavan UD. Sorghum biochemistry: An industrial perspective. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sherwani SFK, Zainudin ES, Sapuan SM, Leman Z, Abdan K. Mechanical properties of sugar palm (Arenga pinnata Wurmb. Merr)/glass fiber-reinforced poly(lactic acid) hybrid composites for potential use in motorcycle components. Polymers (Basel); 2021;13(18):3061. 10.3390/polym13183061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Li H, Huneault MA. Comparison of sorbitol and glycerol as plasticizers for thermoplastic starch in TPS/PLA blends. J Appl Polym Sci. Feb. 2011;119(4):2439–48. 10.1002/app.32956.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Esmaeili M, Pircheraghi G, Bagheri R, Altstädt V. Poly(lactic acid)/coplasticized thermoplastic starch blend: effect of plasticizer migration on rheological and mechanical properties. Polym Adv Technol. 2019;30(4):839–51. 10.1002/pat.4517.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Nazrin A, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM, Tawakkal ISMA, Ilyas RA. Water barrier and mechanical properties of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch (TPS)/poly(lactic acid) (PLA) blend bionanocomposites. Nanotechnol Rev. Jun. 2021;10(1):431–42. 10.1515/ntrev-2021-0033.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Bocz K, Szolnoki B, Marosi A, Tábi T, Wladyka-Przybylak M, Marosi G. Flax fibre reinforced PLA/TPS biocomposites flame retarded with multifunctional additive system. Polym Degrad Stab. 2014;106:63–73. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.10.025.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sienkiewicz A, Czub P. Flame retardancy of biobased composites – research development. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(22):1–30. 10.3390/ma13225253.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Nazrin A, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM. Mechanical, physical and thermal properties of sugar palm nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic starch (tps)/poly(lactic acid) (PLA) blend bionanocomposites. Polymers (Basel). Sep. 2020;12(10):2216. 10.3390/polym12102216.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Kim NK, Dutta S, Bhattacharyya D. A review of flammability of natural fibre reinforced polymeric composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2018;162:64–78. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.04.016.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Rodrigues CA, Tofanello A, Nantes IL, Rosa DS. Biological oxidative mechanisms for degradation of poly(lactic acid) blended with thermoplastic starch. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2015;3(11):2756–66. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00639.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ohkita T, Lee SH. Thermal degradation and biodegradability of poly(lactic acid)/corn starch biocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;100(4):3009–17. 10.1002/app.23425.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ayana B, Suin S, Khatua BB. Highly exfoliated eco-friendly thermoplastic starch (TPS)/poly(lactic acid)(PLA)/clay nanocomposites using unmodified nanoclay. Carbohydr Polym. Sep. 2014;110:430–9. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.024.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Nor Arman NS, Chen RS, Ahmad S. Review of state-of-the-art studies on the water absorption capacity of agricultural fiber-reinforced polymer composites for sustainable construction. Constr Build Mater. July 2021;302:124174. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124174.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Petchwattana N, Sanetuntikul J, Sriromreun P, Narupai B. Wood plastic composites prepared from biodegradable poly(butylene succinate) and burma padauk sawdust (pterocarpus macrocarpus): water absorption kinetics and sunlight exposure investigations. J Bionic Eng. 2017;14(4):781–90. 10.1016/S1672-6529(16)60443-2.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Muñoz E, García-Manrique JA. Water absorption behaviour and its effect on the mechanical properties of flax fibre reinforced bioepoxy composites. Int J Polym Sci. 2015;2015:1–10. 10.1155/2015/390275.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Deroiné M, Le Duigou A, Corre YM, Le Gac PY, Davies P, César G, et al. Accelerated ageing of polylactide in aqueous environments: comparative study between distilled water and seawater. Polym Degrad Stab. 2014;108:319–29. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.01.020.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Asmawi Nazrin et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials