Abstract

Litsea umbellata (Lour.) Merr. is a plant commonly grown in Vietnam and some Asian countries. The plant is used in traditional medicines and exhibits significant biological activities. However, the sesquiterpenes’ extraction in the essential oil (EO) of L. umbellata harvested from the northern region of Vietnam has been limitedly known. Therefore, in the present study, the L. umbellata leaves and stem EOs were obtained by hydrodistillation method, then determined for the phytochemical profile by using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry system, and investigated the cytotoxicity activities against five cancer cell lines. Results have identified a total of 21 and 26 compounds in the EOs of L. umbellata leaves and stem, respectively, with the main sesquiterpene compounds being β-caryophyllene (16.87–11.04%), (+)-spathulenol (9.74–6.57%), β-caryophyllene oxide (26.12–18.34%), and (−)-spatulenol (11.08–8.8%). L. umbellata leaves exhibit significant anti-cancer activity with IC50 values ranging from 29.58 to 62.96 µg/ml. Otherwise, L. umbellata EOs also exhibited the good inhibition activities against DPPH free radical and three bacteria strains. The chemical constituents and cytotoxicity activity of L. umbellata EO stems have been reported for the first time and provided the future applications of this plant.

1 Introduction

Litsea umbellata (Lour.) Merr. (L. umbellata) is a species of flowering plant in the Lauraceae family. L. umbellata is a plant located in China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam [1]. There are many chemical components in Litsea genus, such as monoterpene hydrocarbons, oxygenated monoterpenes, sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, and oxygenated sesquiterpenes. Besides, oxygenated diterpenes, aldehydes, alcohols, ketones, and alkanes were identified [1]. Litsea genus is used in traditional medicine to treat various diseases, such as flu, stomach ache, diarrhea, and diabetes. Litsea costalis species in China and Malaysia is used in traditional medicine to treat flu, and stomachache [2]. Litsea cubeba has been used in the treatment of stomach cold hiccough, gastric cavity crymodynia, cold hernia celialgia, and stagnancy of cold-damp [3]. Recently, the bio-activities of Litsea genus have been reported, such as antimicrobial activity [4,5,6,7], antioxidant [8,9] and anti-inflammatory activities [10,11], and cytotoxic activity [9,12,13]. Particularly, caryophyllene oxide, which is one of the main components of Litsea genus, exhibited anti-cancer activities against various cancer cell lines, such as HeLa, A-2780, HepG2, AGS, SNU-1, and SNU-16 [21,22,23]. Caryophyllene oxide has been may reduce cancer cell invasion by inactivating the pathway of p-ERK and p-p38; otherwise, protein expression was also decreased by caryophyllene oxide on HT1080 cells [24]. In addition, caryophyllene oxide led to early and late apoptosis processes by the caspase-7 activation dependent [25] on PC-3 cells and it is an anti-proliferative agent against PC-3 cells, and inducing apoptosis with non-toxicity on normal cells [25]. However, up to the present, the knowledge about the phytochemical profile as well as the bioactivities of L. umbellata essential oils (Eos) has remained limited known. Herein, the present study has compared the chemical composition of the leaves and stem EO of L. umbellata cultivated in Thai Nguyen province, Vietnam by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) method, followed by evaluation of the cytotoxic activities of the obtained L. umbellata EOs against MCF-7, MKN-7, SK-LU-1, A549, and HepG2 cell lines and inhibition activities against DPPH free radical and three bacterial strains.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Plant material

Fresh leaves and stem of L. umbellata (1.5 kg) were collected from a local farm in Thai Nguyen province (21°35′39.19″N, 105°50′53.41″E), Vietnam, in May 2021. The samples were authenticated by Dr Thuong, Faculty of Biology, Thai Nguyen University of Education. The plant samples were air dried at room temperature prior to the steam distillation process. Pure chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (San Louis, MI, USA).

2.2 Extraction of EOs by steam distillation extraction

Extraction of L. umbellata leaves and stems was performed by using the steam distillation method, as previously described by Kong et al. [2]. The prepared samples were subjected to the steam distillation system for 7 h with 3,000 ml of distilled water. Then, the EOs were extracted with a separating funnel and dehydrated using anhydrous sodium sulfate. The EO with strong flavor was obtained and stored in a sealed glass vial in a refrigerator at 4–5°C prior to analysis. The oil yield (%) was calculated by dividing the volume of the obtained EO by the mass of the initial plant material of L. umbellate.

2.3 GC/MS and GC/flame ionization detector (FID) analysis

The GC–FID analysis was performed with a Hewlett Packard GC (HP5890 series II) equipped with HP-5 MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) with an FID. A microliter of EO in n-hexane samples (1/50, v/v) was initially injected (split mode, split ratio 1:15) 1/15. Helium (0.9 ml/min) was used as the carrier gas. The temperature of injector and detector was set at 210 and 295°C, respectively. The oven temperature was kept at 35°C, then gradually raised to 295°C at 3°C/min, and finally held isothermally for 23 min.

The GC/MS analysis was also performed with a Hewlett Packard GC (HP5890 series II) equipped with HP-5 MS (25 m × 0.25 mm × 0.4 µm) and MS (HP MSD5971 model). Helium (0.9 ml/min) was used as the carrier gas. The oven program started with an initial temperature of 70°C held for 3 min and then, the oven temperature was heated at 10°C/min to 270°C and finally held isothermally for 20 min. The electron impact spectra were recorded at an ion voltage of 70 eV over a scan range of 30–600 uma. The compounds were identified by comparison of their retention indices (RI) and their RI on HP-5MS column with those reported in NIST Chemistry WebBook (http://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/). Further identification was made by comparison of their mass spectra with those stored in the Wiley NBS75K.L and NIST/EPA/NIH (2002 and 2014 version) mass spectral libraries. The experimental RI values were determined by a homologous series of n-alkanes (C6–C25) under similar conditions.

2.4 Cytotoxic assay

The cytotoxicity of L. umbellata leaves and stem EOs was investigated against four established cell lines using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay as described by Skehan et al. [14]. Briefly, MCF-7 cell (human breast carcinoma), MKN-7 cell (human gastric carcinoma), SK-LU-1 cell (human lung carcinoma), A549 cell (adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial cells), and HepG2 cell (human hepatocarcinoma) were maintained at the Bioassay Group Lab, Institute of Biotechnology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology. The culture medium included Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, Eagle’s minimum essential medium, and 10% fetal bovine serum thermoactive activity purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The conditions of cell line incubation include 5% CO2, 95% air, 37°C in a CB 220 incubator (Thermo Scientific). The optical density (OD) measurement was performed at 540 nm on ELISA Plate Reader. The cytotoxicity of L. umbellata leaves and stem EOs was expressed as an IC50 value by using TableCurve 2Dv4 software.

2.5 DPPH free radical assay

The antioxidant capacity of EOs from leaf and trunk of L. umbellata by DPPH free radical neutralization was performed by Tabart et al. [27]. Conduct to aspirate 100 μl of each type of EO at concentrations of 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/ml into test tubes, then add 2.9 ml of 0.1 mM DPPH mixed in methanol, shake well, and allow to stand for 30 min and using a UV–Vis 1800 Shimadzu manual, measured at a wavelength of 517 nm. The DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of the extract was determined according to the following formula: free radical scavenging ability DPPH (%) = 100 × (A c – A s)/A c. In which, A c is the optical absorbance of the control sample, and A s is the optical absorbance of the sample that needs to be determined. The antioxidant capacity was determined based on the value of EC50 (is the concentration of sample with DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of 50%) [27]. After measuring the OD, we proceed to build the standard curve and the correlation equation for the antioxidant activity of the L. umbellata EOs.

2.6 Antibacterial activity assay

The antibacterial activity of EOs was determined by the bacterial inhibitor activity test method, which is described by Hadacek and Harald [26]. Bacterial species tested from slanted agar tubes in a 4°C refrigerator were cultured on solid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and then activated in liquid LB medium for 8–16 h at 28°C, shaking at 200 rpm. Aspirate 100 µl of activated bacterial solution on the plate of solid LB medium and spread evenly on the agar plate until dry. Punch five wells with a diameter of 1 cm on the agar plate and add 100 µl of EO extract from L. umbellata mixed in 2% DMSO solution (the negative control well was supplemented with DMSO, and the positive control well was supplemented with the antibiotic ampicillin 100 mg/ml). Place the diluted Petri dishes in the refrigerator at 4°C for 1–2 h and then in the incubator at 28°C for 18–24 h. Measure the diameter of the antibacterial ring, take a picture, and record the result. Each experiment was repeated three times. The diameter of the antibacterial ring was determined by the formula: H = D – d (mm), where D is the diameter of the sterile ring from the center of the hole (mm) and d is the diameter of the agar perforation (mm).

Convention: (D – d) ≥ 25 mm: has very strong antibacterial activity.

(D – d) ≥ 20 mm: has strong antibacterial activity.

(D – d) ≥ 15 mm: has medium antibacterial activity.

(D – d) ≤ 15 mm: has weak antibacterial activity.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data in the present study were obtained from one-way analysis of variance and are represented as mean ± standard deviation with p < 0.05 being considered as statistically different.

3 Results and discussion

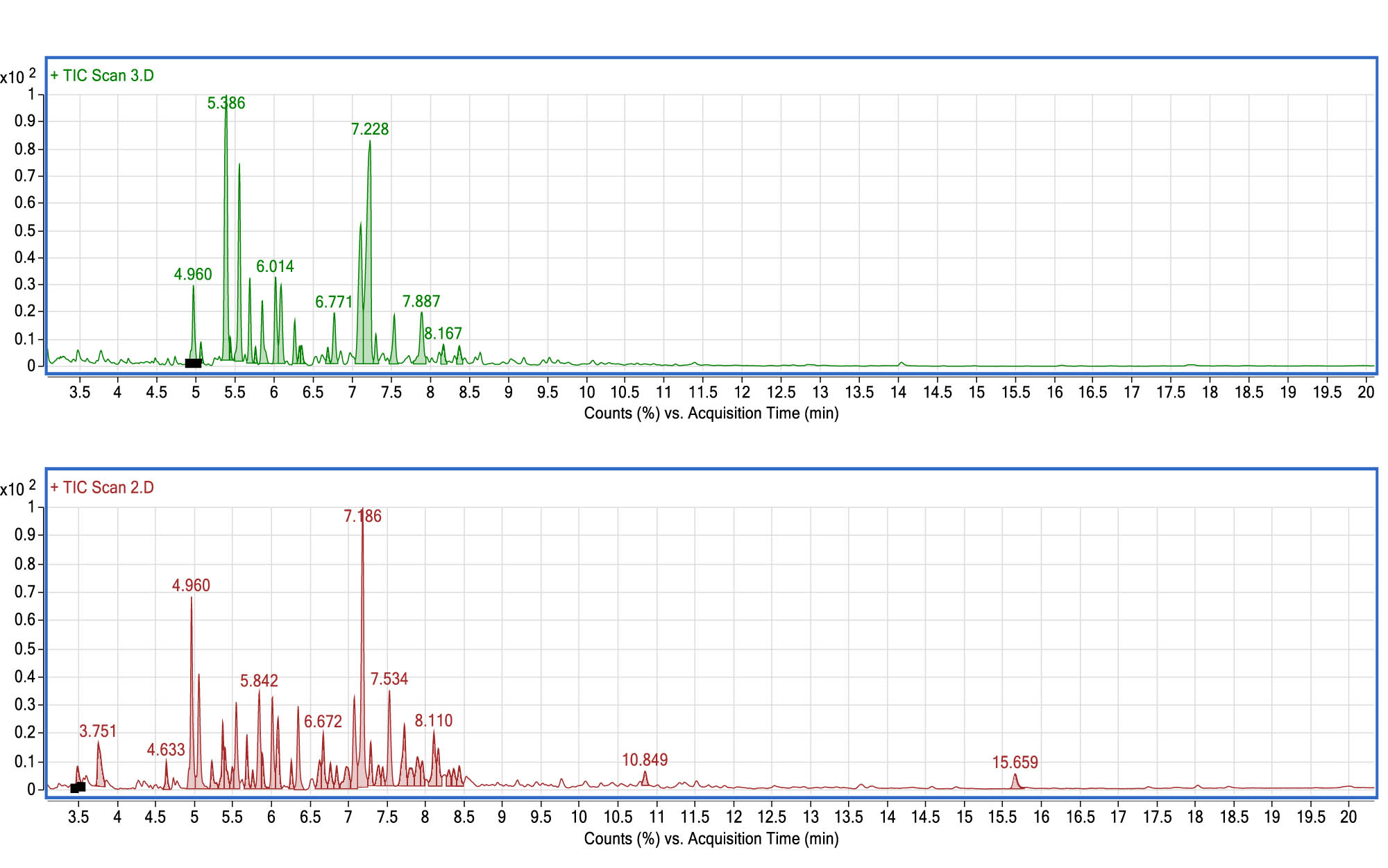

The crude EOs were obtained from leaves and stem of L. umbellata with the yield of 0.08 and 0.04%, respectively. The chemical components of the obtained EOs were analyzed by GC/MS and GC–FID systems (Figure 1) and their relative percentages are reported in Table 1. It can be known that most chemical compositions were similar in the two EOs, except for some components. Specifically, 20 and 23 compounds have been identified in the EO from L. umbellata leaves and stem grown in the north mountain region of Vietnam. The main components were found as β-caryophyllene (16.87 and 11.04%), (+)-spathulenol (9.74 and 6.57%), β-caryophyllene oxide (26.12 and 18.34%), and (−)-spatulenol (11.08 and 8.8%) in the L. umbellata leaves and stem, respectively (Table 1).

The gas chromatography spectrum of L. umbellata leaves (up) and stem (down) EOs.

Chemical composition of the L. umbellata EOs

| No. | Compositions | RI (lit.) | RI (exp.) | Relative content ( %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Stem | ||||

| 1. | α-Copaene | 1,376 | 1,375 | 3.85 | 2.11 |

| 2. | β-Elemene | 1,394 | 1,392 | 0.88 | 1.12 |

| 3. | β-Caryophyllene | 1,415 | 1,415 | 16.87 | 11.04 |

| 4. | α-Himachalene | 1,428 | 1,426 | — | 0,87 |

| 5. | γ-Maaliene | 1,435 | 1,434 | 0.8 | — |

| 6. | α-Caryophyllene | 1,452 | 1,451 | 3.62 | 5.23 |

| 7. | β-Cedrene | 1,424 | 1,464 | 0.59 | 0.43 |

| 8. | γ-Himachalene | 1,481 | 1,485 | 4.31 | 3.13 |

| 9. | (−)-Alloaromadendrene | 1,487 | 1,487 | — | 0.67 |

| 10. | β-Selinene | 1,509 | 1,510 | — | 0.57 |

| 11. | γ-Cadinene | 1,511 | 1,511 | 1.85 | 1.45 |

| 12. | cis-γ-Cadinene | 1,513 | 1,512 | 3.34 | 2.11 |

| 13. | δ-Cadinene | 1,519 | 1,517 | 0.69 | 1.23 |

| 14. | Cadina-1,3,5-triene | 1,543 | 1,540 | 0.84 | 1.56 |

| 15. | (R)-(−)-trans-Nerolidol | 1,551 | 1,552 | 0.8 | 1.54 |

| 16. | 1,1,7-Trimethyl-4-methylenedecahydro-1H-cyclopropa[e]azulen-7-ol | 1,567 | 1,564 | — | 0.56 |

| 17. | (+)-Spathulenol | 1,571 | 1,570 | 9.74 | 6.57 |

| 18. | Isocaryophyllene oxide | 1,572 | 1,571 | 2.78 | 1.23 |

| 19. | β-Caryophyllene oxide | 1,578 | 1,577 | 26.12 | 18.34 |

| 20. | (−)-Spatulenol | 1,582 | 1,584 | 11.08 | 8.8 |

| 21. | (+)-Viridiflorol | 1,593 | 1,592 | 1.36 | 0.79 |

| 22. | Isoaromadendrene epoxide | 1,594 | 1,591 | 1.25 | 0.57 |

| 23. | Cadinol | 1,601 | 1,600 | — | 0.54 |

| 24. | β-Costol | 1,611 | 1,614 | — | 0.78 |

| 25. | 1-Heptatriacotanol | 1,690 | 1,692 | — | 1.03 |

The chemical composition of EO of Litsea plants was varied based on different extraction methods, cultivar, plant parts, time of sampling, and processing [15]. The sesquiterpene group accounted for 37% of the total EOs obtained from the leaves of this plant [16]. Meanwhile, our samples, which were collected in the northern mountainous area of Vietnam, contained a total of 70% of sesquiterpenes of the EO. Besides, the main β-caryophyllene oxide (26.12%) to be different in comparison with major chemical compositions (β-pinene [18.8%], β-caryophyllene [16.2%]) in the sample collected in central Vietnam reported by Dai et al. [15]. Caryophyllene oxide is also found in other species of the genus Litsea, including Litsea deccanensis leaves (8.5%) [17], Litsea glutinosa fruit (5%) [18], and Litsea monopetala flowers (9.5%) in India [19] and Litsea megacarpa leaves in China (56.8%) [2]. Caryophyllene oxide is a sesquiterpenoid oxide in Melissa officinalis and Melaleuca stypheloides, whose content in EOs of 43.8% [20].

The cytotoxic activity of leaves and stem EO of L. umbellata was investigated against MCF-7, MKN-7, SK-LU-1, A549, and HepG2 cell lines. The results are presented in Table 2. Results have shown that no cytotoxicity effect was observed for the L. umbellata stem EO samples at the studied concentrations, as indicated by IC50 value >100 µg/ml. On the other hand, as compared to ellipticine (i.e., positive control), the EO of L. umbellata leaves exhibited high inhibitory activity against five tested cancer cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 26.23 to 62.96 µg/ml (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that caryophyllene oxide exhibited inhibitory activities against several cancer cell lines, such as HeLa, A-2780, HepG2, AGS, SNU-1, and SNU-16 [21,22,23]. Therefore, the higher content of caryophyllene oxide in L. umbellata leaves EO than its stem EO may have given rise to its high cytotoxicity effect. Previously, the anti-cancer activities of L. cubeba EO against OEC-M1, J5, and A549 cells were significant, as indicated by IC50 values of around 50, 50, and 100 ppm, respectively [12]. Thus, it can be concluded that L. umbellata leaves EOs exhibited higher cytotoxic activities than L. cubeba EOs against A549 cells [12].

Cytotoxic activities of L. umbellata leaves and stem EO

| Cancer cell lines | Leaves | IC50 value (µg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | Stem | Ellipticine | ||

| HepG2 | 54.82 ± 3.52 | 3.45 | >100 | 0.40 ± 0.04 |

| MKN-7 | 33.51 ± 2.39 | 3.76 | >100 | 0.27 ± 0.04 |

| SK-LU-1 | 62.96 ± 1.19 | 3.15 | >100 | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| A549 | 26.23 ± 1.40 | 3.50 | >100 | 0.41 ± 0.07 |

| MCF-7 | 43.01 ± 1.55 | 3.23 | >100 | 0.41 ± 0.05 |

Data represented as mean ± SD of three independent replicates, p < 0.05 is considered significant. SI: selective index.

In addition, L. umbellata EOs was experimented with the anti-oxidant activities by using DPPH free radical assay and anti-bacterial activities by using the bacterial inhibitor activity test method. The results show that L. umbellata EOs exhibited the anti-oxidant activities with IC50 = 3.24 µg/ml and the results of anti-bacterial activities are summarized in Table 3. In Table 3, EOs from leaves exhibited better inhibitory activities against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus strains than EOs from the trunk.

Antibacterial activity of EOs of L. umbellata leaves and stem

| Bacterial inhibitor | Concentration | Bacterial strains (zone of inhibition, mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | ||

| Ampicillin | 100 mg/ml | 18.3 ± 0.1 | 19.0 ± 0.2 | 16.0 ± 0.1 |

| Leaves | 25 µg/ml | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 µg/ml | 19.1 ± 0.2 | 19.9 ± 0.3 | 21.9 ± 0.2 | |

| 100 µg/ml | 29.0 ± 0.3 | 30.9 ± 0.2 | 31.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Stem | 25 µg/ml | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 µg/ml | 19.9 ± 0.3 | 27.6 ± 0.2 | 20.1 ± 0.4 | |

| 100 µg/ml | 29.9 ± 0.3 | 35.1 ± 0.4 | 32.1 ± 0.4 | |

4 Conclusions

The medicinal plant L. umbellata has exhibited many important biological and pharmacological activities. To date, many traditional medicines have used this medicinal ingredient. The sesquiterpenes have many biological activities, particularly inhibition activities against cancer cells, so in this study, the aim of this study was to identify the main components of the sesquiterpene group present in the medicinal plant L, umbellata and evaluate the inhibition activity against cancer cell lines MCF-7, MKN-7, SK-LU-1, A549, and HepG2 and against DPPH free radical and three bacterial strains are important in providing more scientific basis for the use of this plant in the medicinal industry.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the University of Thai Nguyen University of Education, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam (CS.2021.20).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the University of Thai Nguyen University of Education, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam (CS.2021.20).

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, H.P.H. and P.V.K.; methodology, H.P.H., P.V.K., and T.Q.T.; software, H.P.H.; investigation, T.Q.T.; writing – original draft preparation, H.P.H. and P.V.K.; writing – review and editing, T.Q.T. and P.V.K; supervision, P.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Azhar MAM, Salleh WMNHW. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oils of the genus Litsea (Lauraceae)-A review. Agric Conspec Sci. 2020;85(2):97–103.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Kong DG, Zhao Y, Li GH, Chen BJ, Wang XN, Zhou HL, et al. The genus Litsea in traditional Chinese medicine: An ethnomedical, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;164:256–64. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wang H, Liu Y. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils from different parts of Litsea cubeba. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7(1):229–35. 10.1002/cbdv.200800349.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hao K, Xu B, Zhang G, Lv F, Wang Y, Ma M, et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of Litsea cubeba L. essential oil against Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Product Commun. 2021;16(3):1–7. 10.1177/1934578X21999146.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Mei C, Wang X, Chen Y, Wang Y, Yao F, Li Z, et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of Litsea cubeba essential oil against food contamination by Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Food Saf. 2020;40(4):e12809. 10.1111/JFS.12809.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] She QH, Li WS, Jiang YY, Wu YC, Zhou YH, Zhang L. Chemical composition, antimicrobial activity and antioxidant activity of Litsea cubeba essential oils in different months. Nat Product Res. 2020;34(22):3285–8. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1557177.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Thielmann J, Muranyi P. Review on the chemical composition of Litsea cubeba essential oils and the bioactivity of its major constituents citral and limonene. J Essent Oil Res. 2019;31(5):361–78. 10.1080/10412905.2019.1611671.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Dalimunthe A, Hasibuan PA, Silalahi J, Sinaga S, Satria D. Antioxidant activity of alkaloid compounds from Litsea cubeba Lour. Orient J Chem. 2018;34(2):1149–52. 10.13005/OJC/340270.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Qin Z, Feng K, Wang S, Zhao W, Jie Y, Lu J, et al. Comparative study on the essential oils of six Hawk tea (Litsea coreana Levl. var. lanuginosa) from China: Yields, chemical compositions and biological activities. Ind Crop Prod. 2018;124:126–35. 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2018.07.035.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Ham M, Cho S, Song S, Yoon SA, Lee YB, Kim CS, et al. Litsenolide A2: The major anti-inflammatory activity compound in Litsea japonica fruit. J Funct Foods. 2017;39:168–74. 10.1016/J.JFF.2017.10.024.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Lin B, Sun L, Xin HL, Nian H, Song HT, Jiang YP, et al. Anti-inflammatory constituents from the root of Litsea cubeba in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. Pharm Biol. 2016;54(9):1741–7. 10.3109/13880209.2015.1126619.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ho CL, Jie-Ping O, Liu YC, Hung CP, Tsai MC, Liao PC, et al. Compositions and in vitro anticancer activities of the leaf and fruit oils of Litsea cubeba from Taiwan. Nat Product Commun. 2010;5(4):617–20. 10.1177/1934578X1000500425.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Xia H, Xia G, Wang L, Wang M, Wang Y, Lin P, et al. Bioactive sesquineolignans from the twigs of Litsea cubeba. Chin J Nat Med. 2021;19(10):796–800. 10.1016/S1875-5364(21)60075-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, Mcmahon J, Vistica D, et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(13):1107–12. 10.1093/JNCI/82.13.1107.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Dai D, Hung N, Chung N, Huong L, Hung N, Ogunwande I. Chemical constituents of the essential oils from the leaves of Litsea umbellata and Litsea iteodaphne and their mosquito larvicidal activity. J Essent Oil-Bear Plants. 2020;23(6):1334–44. 10.1080/0972060X.2020.1858347.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Irulandi K, Kumar J, Arun KD, Rameshprabu N, Swamy P. Leaf essential oil composition of two endemic Litsea species from South India. Chem Nat Compd. 2016;52(1):1–3. 10.1007/s10600-016-1579-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Choudhury S, Singh R, Ghosh A, Leclercq P. Litsea glutinosa (Lour.) C.B. Rob. A new source of essential oil from Northeast India. J Essent Oil Res. 1996;8(5):553–6. 10.1080/10412905.1996.9700687.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Choudhury S, Ghosh A, Choudhury M, Leclercq P. Essential oils of Litsea monopetala (Roxb.) Pers. A new report from India. J Essent Oil Res. 1997;9(6):635–9. 10.1080/10412905.1997.9700802.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Farag R, Shalaby A, El-Baroty G, Ibrahim N, Ali M, Hassan E. Chemical and biological evaluation of the essential oils of different Melaleuca species. Phytother Res. 2004;18:30–5. 10.1002/ptr.1348.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Jun N, Mosaddik A, Moon J, Jang K, Lee D, Ahn K, et al. Cytotoxic activity of β-caryophyllene oxide isolated from Jeju Guava (Psidium cattleianum Sabine) leaf. Rec Nat Prod. 2011;5:242–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Dahham S, Tabana Y, Iqbal M, Ahamed M, Ezzat M, Majid A, et al. The Anticancer, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene from the essential Oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules. 2015;20:11808–29. 10.3390/molecules200711808.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Shahwar D, Ullah S, Khan M, Ahmad N, Saeed A, Ullah S. Anticancer activity of Cinnamon tamala leaf constituents towards human ovarian cancer cells. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28:969–72.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Khang P, Truong M, Hiep H, Thuong S, Shen S. Extraction, chemical compositions, and cytotoxic activities of essential oils of Thevetia peruviana. Toxicol Environ Chem. 2020;102(1–4):124–31. 10.1080/02772248.2020.1770255.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Jo H, Kim M. β-Caryophyllene oxide inhibits metastasis by downregulating MMP-2, p-p38 and p-ERK in human fibrosarcoma cells. J Food Biochem. 2022;46(12):e14468. 10.1111/jfbc.14468.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Delgado C, Mendez-Callejas G, Celis C. Caryophyllene oxide, the active compound isolated from leaves of Hymenaea courbaril L. (Fabaceae) with antiproliferative and apoptotic effects on PC-3 androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line. Molecules. 2021;26(20):6142. 10.3390/molecules26206142.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Hadacek F, Harald G. Testing of antifungal natural products: Methodologies, comparability of results and assay choice. Phytochem Anal. 2020;11(3):137.10.1002/(SICI)1099-1565(200005/06)11:3<137::AID-PCA514>3.0.CO;2-ISuche in Google Scholar

[27] Tabart J, Kevers C, Pincemail J, Defraigne J, Dommes J. Comparative antioxidant capacities of phenolic compounds measured by various tests. Food Chem. 2009;113(4):1226. 10.1016/JFOODCHEM.2008.08.013.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening

- Prefatory in silico studies and in vitro insecticidal effect of Nigella sativa (L.) essential oil and its active compound (carvacrol) against the Callosobruchus maculatus adults (Fab), a major pest of chickpea

- Polymerized methyl imidazole silver bromide (CH3C6H5AgBr)6: Synthesis, crystal structures, and catalytic activity

- Using calcined waste fish bones as a green solid catalyst for biodiesel production from date seed oil

- Influence of the addition of WO3 on TeO2–Na2O glass systems in view of the feature of mechanical, optical, and photon attenuation

- Naringin ameliorates 5-fluorouracil elicited neurotoxicity by curtailing oxidative stress and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 pathway

- GC-MS profile of extracts of an endophytic fungus Alternaria and evaluation of its anticancer and antibacterial potentialities

- Green synthesis, chemical characterization, and antioxidant and anti-colorectal cancer effects of vanadium nanoparticles

- Determination of caffeine content in coffee drinks prepared in some coffee shops in the local market in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

- A new 3D supramolecular Cu(ii) framework: Crystal structure and photocatalytic characteristics

- Bordeaux mixture accelerates ripening, delays senescence, and promotes metabolite accumulation in jujube fruit

- Important application value of injectable hydrogels loaded with omeprazole Schiff base complex in the treatment of pancreatitis

- Color tunable benzothiadiazole-based small molecules for lightening applications

- Investigation of structural, dielectric, impedance, and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-modified barium titanate composites for biomedical applications

- Metal gel particles loaded with epidermal cell growth factor promote skin wound repair mechanism by regulating miRNA

- In vitro exploration of Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) mushroom fruiting bodies: Potential antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agent

- Alteration in the molecular structure of the adenine base exposed to gamma irradiation: An ESR study

- Comprehensive study of optical, thermal, and gamma-ray shielding properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses

- Lewis acids as co-catalysts in Pd-based catalyzed systems of the octene-1 hydroethoxycarbonylation reaction

- Synthesis, Hirshfeld surface analysis, thermal, and selective α-glucosidase inhibitory studies of Schiff base transition metal complexes

- Protective properties of AgNPs green-synthesized by Abelmoschus esculentus on retinal damage on the virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in diabetic rat

- Effects of green decorated AgNPs on lignin-modified magnetic nanoparticles mediated by Cydonia on cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by green mediated silver nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica bark aqueous extract

- Preparation of newly developed porcelain ceramics containing WO3 nanoparticles for radiation shielding applications

- Utilization of computational methods for the identification of new natural inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase in inflammation therapy

- Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors

- Clay-based bricks’ rich illite mineral for gamma-ray shielding applications: An experimental evaluation of the effect of pressure rates on gamma-ray attenuation parameters

- Stability kinetics of orevactaene pigments produced by Epicoccum nigrum in solid-state fermentation

- Treatment of denture stomatitis using iron nanoparticles green-synthesized by Silybum marianum extract

- Characterization and antioxidant potential of white mustard (Brassica hirta) leaf extract and stabilization of sunflower oil

- Characteristics of Langmuir monomolecular monolayers formed by the novel oil blends

- Strategies for optimizing the single GdSrFeO4 phase synthesis

- Oleic acid and linoleic acid nanosomes boost immunity and provoke cell death via the upregulation of beta-defensin-4 at genetic and epigenetic levels

- Unraveling the therapeutic potential of Bombax ceiba roots: A comprehensive study of chemical composition, heavy metal content, antibacterial activity, and in silico analysis

- Green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extract and investigation of its anti-human colorectal cancer application

- The adsorption of naproxen on adsorbents obtained from pepper stalk extract by green synthesis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by silver nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan polymers mediated by Pistacia atlantica extract under ultrasound condition

- In vitro protective and anti-inflammatory effects of Capparis spinosa and its flavonoids profile

- Wear and corrosion behavior of TiC and WC coatings deposited on high-speed steels by electro-spark deposition

- Therapeutic effects of green-formulated gold nanoparticles by Origanum majorana on spinal cord injury in rats

- Melanin antibacterial activity of two new strains, SN1 and SN2, of Exophiala phaeomuriformis against five human pathogens

- Evaluation of the analgesic and anesthetic properties of silver nanoparticles supported over biodegradable acacia gum-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- Review Articles

- Role and mechanism of fruit waste polyphenols in diabetes management

- A comprehensive review of non-alkaloidal metabolites from the subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae)

- Discovery of the chemical constituents, structural characteristics, and pharmacological functions of Chinese caterpillar fungus

- Eco-friendly green approach of nickel oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications

- Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration

- Rapid Communication

- Determination of the contents of bioactive compounds in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Comparison of commercial and wild samples

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: The protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α”

- Topical Issue on Phytochemicals, biological and toxicological analysis of aromatic medicinal plants

- Anti-plasmodial potential of selected medicinal plants and a compound Atropine isolated from Eucalyptus obliqua

- Anthocyanin extract from black rice attenuates chronic inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mouse model by modulating the gut microbiota

- Evaluation of antibiofilm and cytotoxicity effect of Rumex vesicarius methanol extract

- Chemical compositions of Litsea umbellata and inhibition activities

- Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles using Rhynchosia capitata leaf extract and their biological activities

- GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activities of some plants belonging to the genus Euphorbia on selected bacterial isolates

- The abrogative effect of propolis on acrylamide-induced toxicity in male albino rats: Histological study

- A phytoconstituent 6-aminoflavone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress mediated synapse and memory dysfunction via p-Akt/NF-kB pathway in albino mice

- Anti-diabetic potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder: Phytochemistry (GC-MS analysis), α-amylase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, in vivo hypoglycemic, and biochemical analysis

- Assessment of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the Cassia angustifolia aqueous extract against SW480 colon cancer

- Biochemical analysis, antioxidant, and antibacterial efficacy of the bee propolis extract (Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera) against Staphylococcus aureus-induced infection in BALB/c mice: In vitro and in vivo study

- Assessment of essential elements and heavy metals in Saudi Arabian rice samples underwent various processing methods

- Two new compounds from leaves of Capparis dongvanensis (Sy, B. H. Quang & D. V. Hai) and inhibition activities

- Hydroxyquinoline sulfanilamide ameliorates STZ-induced hyperglycemia-mediated amyleoid beta burden and memory impairment in adult mice

- An automated reading of semi-quantitative hemagglutination results in microplates: Micro-assay for plant lectins

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assessment of essential and toxic trace elements in traditional spices consumed by the population of the Middle Eastern region in their recipes

- Phytochemical analysis and anticancer activity of the Pithecellobium dulce seed extract in colorectal cancer cells

- Impact of climatic disturbances on the chemical compositions and metabolites of Salvia officinalis

- Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils of Urginea maritima and Allium sativum

- Phytochemical analysis and antifungal efficiency of Origanum majorana extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi causing tomato damping-off diseases

- Special Issue on 4th IC3PE

- Graphene quantum dots: A comprehensive overview

- Studies on the intercalation of calcium–aluminium layered double hydroxide-MCPA and its controlled release mechanism as a potential green herbicide

- Synergetic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis by zinc ferrite-anchored graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet for the removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light irradiation

- Exploring anticancer activity of the Indonesian guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) fraction on various human cancer cell lines in an in vitro cell-based approach

- The comparison of gold extraction methods from the rock using thiourea and thiosulfate

- Special Issue on Marine environmental sciences and significance of the multidisciplinary approaches

- Sorption of alkylphenols and estrogens on microplastics in marine conditions

- Cytotoxic ketosteroids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp.

- Antibacterial and biofilm prevention metabolites from Acanthophora spicifera

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part II

- Green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial activities of cobalt nanoparticles produced by marine fungal species Periconia prolifica

- Combustion-mediated sol–gel preparation of cobalt-doped ZnO nanohybrids for the degradation of acid red and antibacterial performance

- Perinatal supplementation with selenium nanoparticles modified with ascorbic acid improves hepatotoxicity in rat gestational diabetes

- Evaluation and chemical characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi associated with the ethnomedicinal plant Bergenia ciliata

- Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency with SQI-Br and SQI-I sensitizers: A comparative analysis

- Nanostructured p-PbS/p-CuO sulfide/oxide bilayer heterojunction as a promising photoelectrode for hydrogen gas generation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening

- Prefatory in silico studies and in vitro insecticidal effect of Nigella sativa (L.) essential oil and its active compound (carvacrol) against the Callosobruchus maculatus adults (Fab), a major pest of chickpea

- Polymerized methyl imidazole silver bromide (CH3C6H5AgBr)6: Synthesis, crystal structures, and catalytic activity

- Using calcined waste fish bones as a green solid catalyst for biodiesel production from date seed oil

- Influence of the addition of WO3 on TeO2–Na2O glass systems in view of the feature of mechanical, optical, and photon attenuation

- Naringin ameliorates 5-fluorouracil elicited neurotoxicity by curtailing oxidative stress and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 pathway

- GC-MS profile of extracts of an endophytic fungus Alternaria and evaluation of its anticancer and antibacterial potentialities

- Green synthesis, chemical characterization, and antioxidant and anti-colorectal cancer effects of vanadium nanoparticles

- Determination of caffeine content in coffee drinks prepared in some coffee shops in the local market in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

- A new 3D supramolecular Cu(ii) framework: Crystal structure and photocatalytic characteristics

- Bordeaux mixture accelerates ripening, delays senescence, and promotes metabolite accumulation in jujube fruit

- Important application value of injectable hydrogels loaded with omeprazole Schiff base complex in the treatment of pancreatitis

- Color tunable benzothiadiazole-based small molecules for lightening applications

- Investigation of structural, dielectric, impedance, and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-modified barium titanate composites for biomedical applications

- Metal gel particles loaded with epidermal cell growth factor promote skin wound repair mechanism by regulating miRNA

- In vitro exploration of Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) mushroom fruiting bodies: Potential antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agent

- Alteration in the molecular structure of the adenine base exposed to gamma irradiation: An ESR study

- Comprehensive study of optical, thermal, and gamma-ray shielding properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses

- Lewis acids as co-catalysts in Pd-based catalyzed systems of the octene-1 hydroethoxycarbonylation reaction

- Synthesis, Hirshfeld surface analysis, thermal, and selective α-glucosidase inhibitory studies of Schiff base transition metal complexes

- Protective properties of AgNPs green-synthesized by Abelmoschus esculentus on retinal damage on the virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in diabetic rat

- Effects of green decorated AgNPs on lignin-modified magnetic nanoparticles mediated by Cydonia on cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by green mediated silver nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica bark aqueous extract

- Preparation of newly developed porcelain ceramics containing WO3 nanoparticles for radiation shielding applications

- Utilization of computational methods for the identification of new natural inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase in inflammation therapy

- Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors

- Clay-based bricks’ rich illite mineral for gamma-ray shielding applications: An experimental evaluation of the effect of pressure rates on gamma-ray attenuation parameters

- Stability kinetics of orevactaene pigments produced by Epicoccum nigrum in solid-state fermentation

- Treatment of denture stomatitis using iron nanoparticles green-synthesized by Silybum marianum extract

- Characterization and antioxidant potential of white mustard (Brassica hirta) leaf extract and stabilization of sunflower oil

- Characteristics of Langmuir monomolecular monolayers formed by the novel oil blends

- Strategies for optimizing the single GdSrFeO4 phase synthesis

- Oleic acid and linoleic acid nanosomes boost immunity and provoke cell death via the upregulation of beta-defensin-4 at genetic and epigenetic levels

- Unraveling the therapeutic potential of Bombax ceiba roots: A comprehensive study of chemical composition, heavy metal content, antibacterial activity, and in silico analysis

- Green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extract and investigation of its anti-human colorectal cancer application

- The adsorption of naproxen on adsorbents obtained from pepper stalk extract by green synthesis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by silver nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan polymers mediated by Pistacia atlantica extract under ultrasound condition

- In vitro protective and anti-inflammatory effects of Capparis spinosa and its flavonoids profile

- Wear and corrosion behavior of TiC and WC coatings deposited on high-speed steels by electro-spark deposition

- Therapeutic effects of green-formulated gold nanoparticles by Origanum majorana on spinal cord injury in rats

- Melanin antibacterial activity of two new strains, SN1 and SN2, of Exophiala phaeomuriformis against five human pathogens

- Evaluation of the analgesic and anesthetic properties of silver nanoparticles supported over biodegradable acacia gum-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- Review Articles

- Role and mechanism of fruit waste polyphenols in diabetes management

- A comprehensive review of non-alkaloidal metabolites from the subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae)

- Discovery of the chemical constituents, structural characteristics, and pharmacological functions of Chinese caterpillar fungus

- Eco-friendly green approach of nickel oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications

- Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration

- Rapid Communication

- Determination of the contents of bioactive compounds in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Comparison of commercial and wild samples

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: The protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α”

- Topical Issue on Phytochemicals, biological and toxicological analysis of aromatic medicinal plants

- Anti-plasmodial potential of selected medicinal plants and a compound Atropine isolated from Eucalyptus obliqua

- Anthocyanin extract from black rice attenuates chronic inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mouse model by modulating the gut microbiota

- Evaluation of antibiofilm and cytotoxicity effect of Rumex vesicarius methanol extract

- Chemical compositions of Litsea umbellata and inhibition activities

- Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles using Rhynchosia capitata leaf extract and their biological activities

- GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activities of some plants belonging to the genus Euphorbia on selected bacterial isolates

- The abrogative effect of propolis on acrylamide-induced toxicity in male albino rats: Histological study

- A phytoconstituent 6-aminoflavone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress mediated synapse and memory dysfunction via p-Akt/NF-kB pathway in albino mice

- Anti-diabetic potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder: Phytochemistry (GC-MS analysis), α-amylase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, in vivo hypoglycemic, and biochemical analysis

- Assessment of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the Cassia angustifolia aqueous extract against SW480 colon cancer

- Biochemical analysis, antioxidant, and antibacterial efficacy of the bee propolis extract (Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera) against Staphylococcus aureus-induced infection in BALB/c mice: In vitro and in vivo study

- Assessment of essential elements and heavy metals in Saudi Arabian rice samples underwent various processing methods

- Two new compounds from leaves of Capparis dongvanensis (Sy, B. H. Quang & D. V. Hai) and inhibition activities

- Hydroxyquinoline sulfanilamide ameliorates STZ-induced hyperglycemia-mediated amyleoid beta burden and memory impairment in adult mice

- An automated reading of semi-quantitative hemagglutination results in microplates: Micro-assay for plant lectins

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assessment of essential and toxic trace elements in traditional spices consumed by the population of the Middle Eastern region in their recipes

- Phytochemical analysis and anticancer activity of the Pithecellobium dulce seed extract in colorectal cancer cells

- Impact of climatic disturbances on the chemical compositions and metabolites of Salvia officinalis

- Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils of Urginea maritima and Allium sativum

- Phytochemical analysis and antifungal efficiency of Origanum majorana extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi causing tomato damping-off diseases

- Special Issue on 4th IC3PE

- Graphene quantum dots: A comprehensive overview

- Studies on the intercalation of calcium–aluminium layered double hydroxide-MCPA and its controlled release mechanism as a potential green herbicide

- Synergetic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis by zinc ferrite-anchored graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet for the removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light irradiation

- Exploring anticancer activity of the Indonesian guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) fraction on various human cancer cell lines in an in vitro cell-based approach

- The comparison of gold extraction methods from the rock using thiourea and thiosulfate

- Special Issue on Marine environmental sciences and significance of the multidisciplinary approaches

- Sorption of alkylphenols and estrogens on microplastics in marine conditions

- Cytotoxic ketosteroids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp.

- Antibacterial and biofilm prevention metabolites from Acanthophora spicifera

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part II

- Green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial activities of cobalt nanoparticles produced by marine fungal species Periconia prolifica

- Combustion-mediated sol–gel preparation of cobalt-doped ZnO nanohybrids for the degradation of acid red and antibacterial performance

- Perinatal supplementation with selenium nanoparticles modified with ascorbic acid improves hepatotoxicity in rat gestational diabetes

- Evaluation and chemical characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi associated with the ethnomedicinal plant Bergenia ciliata

- Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency with SQI-Br and SQI-I sensitizers: A comparative analysis

- Nanostructured p-PbS/p-CuO sulfide/oxide bilayer heterojunction as a promising photoelectrode for hydrogen gas generation