Abstract

In marine ecosystems, living organisms are continuously exposed to a cocktail of anthropogenic contaminants, such as microplastics (MPs) and endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs). Being able to adsorb organic compounds, MPs would act as an additional contamination vector for aquatic organisms. To support this hypothesis, the sorption of six EDCs on MPs, including 4-t-butylphenol, 4-t-octylphenol, 4-n-octylphenol, 4-n-nonylphenol, 17β-estradiol and its synthetic analog 17α-ethinylestradiol, has been investigated. These compounds belong to two contaminant families, alkylphenols and estrogens, included in the EU priority and watch lists of the Water Framework Directive. Sorption kinetics were studied onto polyethylene and polypropylene MPs under seawater conditions. MPs at a concentration of 0.400 mg mL−1 were added to a mix of the six EDCs, each at the individual concentration of 100 ng mL−1. The concentrations of contaminants were chosen to be close to environmental ones and comparable with those found in literature. The results demonstrated that the hydrophobicity of the compounds and the MP type are the two factors influencing the sorption capacity. The distribution coefficient (K d) of each compound was determined and compared to others found in the literature. A high affinity was demonstrated between 4-n-NP and PE, with a sorption reaching up to 2,200 ng mg−1.

1 Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) have been defined as plastic items ranging from 1 µm to 5 mm in size [1]. They are omnipresent and persistent in the environment, from the mountains to the seabed [2–6]. In addition to MPs, aquatic living organisms are continuously exposed to a cocktail of environmental organic contaminants impacting their health. Many deleterious effects of plastic wastes (including MPs) have been reported in animals [7–12]. Besides some physical effects, MPs lead to reproduction and immunological disruptions in some species [13]. Additional effects could also be the result of another organic compound transfer pathway to the organisms, through their sorption onto MPs. The MPs would act as a vector of organic contaminants for organisms. The presence of organic compounds in/onto MPs may have two origins. On the one hand, chemicals have been added during the plastic production as additives, such as phthalates, bisphenols and alkylphenols (APs), in order to adapt the plastic properties to their uses [14]. On the other hand, some environmental contaminants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs) or APs for example, can be sorbed onto MP surface via chemical interactions. As a general trend, environmental organic compounds show a high affinity for plastics due to their same hydrophobic characteristics [15–17]. Their sorption capacity also depends on MP characteristics and environmental composition [18,19]. The cocktail of environmental organic contaminants associated with MPs could potentially threat the health of living organisms and even more, humans through the magnification along the food chain [20].

Different contaminants were measured on MP surfaces collected in aquatic ecosystems [21–23]. For example, some concentrations up to 14,459 ng g−1 for PAHs, 2,856 ng g−1 for PCBs and 454 ng g−1 for pesticides have been reported on plastic fragments sampled in the North Pacific [24]. Lowest values have been measured on plastics collected near the Vietnam coast: 2,024, 102, 108 and 551 ng g−1 for PAHs, PCBs, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and nonylphenol (NP), respectively [21]. The concentrations of PCBs and DDT from MPs collected along the Atlantic coast were, respectively, 7 and 4 ng g−1 [22], while they were found at higher concentration (53 and 27.6 ng g−1, respectively) on Izmir coast, Turkey [23]. Despite these observations, the study of sorption mechanisms was debated latterly and still remains very limited to date [25,26].

Among aquatic pollutants, endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) are of great concern due to their multiple action mechanisms on organisms at low doses. Several observations of adverse effects on reproduction, growth and development of aquatic wildlife species have been reported [27–29]. At a global scale, waste water treatment plant effluents were characterized as one of the major sources of EDC-like molecules in aquatic ecosystems, particularly natural and synthetic steroidal estrogens (17β-estradiol (E2) and 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2)), as well as APs, such as 4-tert-octylphenol (4-t-OP) or NPs [30–32]. These two classes of substances are included in the EU priority and watch lists of the Water Framework Directive [33]. Environmental concentrations of estrogens were reported in different compartments of aquatic ecosystems. For example, E2 reach 175 ng L−1 in seawater in Italy [34], while EE2 was reported at 134 ng g−1 in sediment collected in Brazil [35] and at 38 ng g−1 of lipids in a marine mollusk (Mytilus galloprovincialis) collected in Italy [34]. APs are commonly used as plastic additives for their antioxidant and detergent roles. They were also frequently detected in aquatic environments [36–38].

The aim of this research was to characterize the sorption of 6 EDCs, i.e., four APs (4-tertbutyl-phenol (4-t-BP), 4-tertoctyl-phenol (4-t-OP), 4-n-octylphenol (4-n-OP) and 4-n-nonylphenol (4-n-NP)) and two estrogens (E2 and EE2) on polyethylene (PE) MPs. The concentrations of contaminants (0.400 mg mL−1 of MPs and 100 ng mL−1 of each EDC) were chosen considering the marine environmental medium, i.e., being close to environmental ones as well as comparable with those found in literature. The suitable equilibrium time and the distribution coefficients were determined, as well as the EDC recoveries throughout the experiment. Two different types of MPs, PE and polypropylene (PP), corresponding to the two most produced plastics frequently detected in marine environment [39], were then used to evaluate the influence of the polymer nature on the sorption of 4-n-NP.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals, quality assurance and quality control

Low density MPs made of PE and PP were obtained from household products, a bag and a cable, respectively. After grinding the items (Cryogenic mill, SPEX 6770), particles with a size ranging from 53 to 100 µm were selected using a metallic sieve.

The suppliers and the chemical properties of the six studied EDCs are presented in Table 1, and their chemical structures are given in Supplementary Information (Figure S1). Cellulose nitrate filters (12 µm of porosity and 25 mm of diameter) were purchased from Merck-Millipore. All organic solvents were (high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and purchased from VWR: acetonitrile (ACN), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and dimethylformamide (DMF).

Chemical properties of the six organic compounds used for the sorption study onto microplastics

| Properties | APs | Estrogens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-t-BP | 4-t-OP | 4-n-OP | 4-n-NP | E2 | EE2 | |

| Formula | C10H14O | C14H22O | C14H22O | C15H24O | C18H24O2 | C20H24O2 |

| log K ow | 3.29 | 3.70 | 4.12 | 4.48 | 4.01 | 3.67 |

| Solubility(*) (mg L−1) | 610 | 12.6 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 11.3 | 3.9 |

| C.A.S. number | 98-54-4 | 140-66-9 | 1,806-26-4 | 104-40-5 | 50-28-2 | 57-63-6 |

| Provider | Fluka | Sigma-Aldrich | Alfa-Aesar | Sigma-Aldrich | ||

(*): Values measured in water at 25°C.

4-t-BP: 4-t-butylphenol; 4-t-OP: 4-t-octylphenol; 4-n-OP: 4-n-octylphenol; 4-n-NP: 4-n-nonylphenol; E2: 17β-estradiol and EE2: 17α-ethinylestradiol.

All the laboratory material, chemicals and apparatus were pretreated to prevent cross-contaminations. Solvents were directly used after delivery and not reused. All glass materials were washed with Milli-Q water and pyrolyzed (550°C for 4 h) to eliminate all traces of organic compounds. The cellulose nitrate filters were rinsed with MilliQ-Q water before being used to prevent cross-contamination by MPs. The assessment of the absence of organic compound cross-contamination was performed by preparing different blank samples, i.e., without MPs and EDCs, as well as with MPs or EDCs only in seawater. These additional conditions were used for data correction concern.

3 Experimental design

3.1 Recovery and distribution coefficient determination

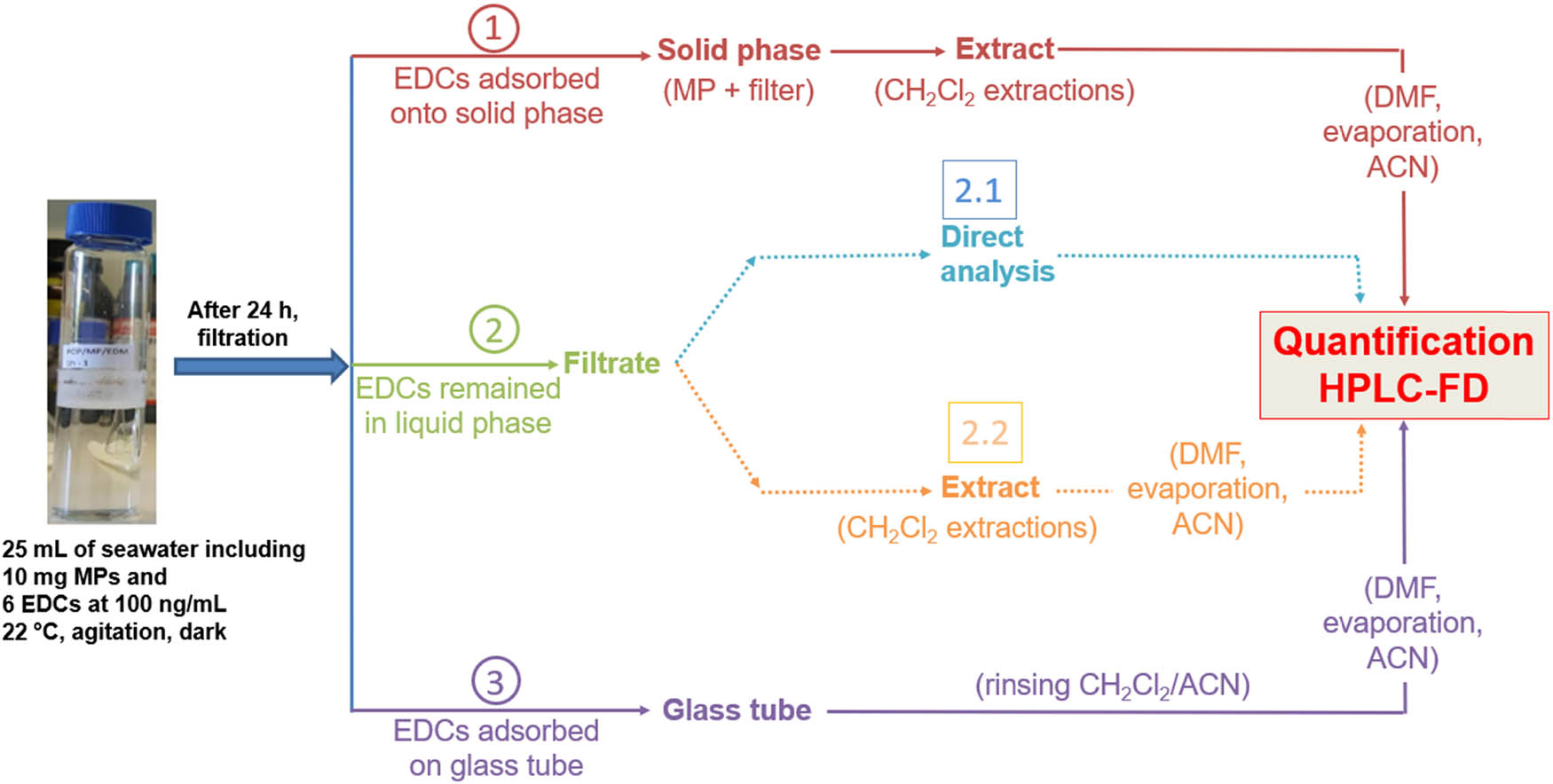

The protocol setup is presented in Figure 1. Experimental concentrations of PE MPs and individual EDCs were fixed at 0.400 mg mL−1 and 100 ng mL−1 in artificial seawater (salinity of 30 PSU, Aquarium Bulle, Poissy, France), respectively. Triplicates were performed. Practically, 10.0 mg of PE MPs was introduced into a glass tube containing 25 mL of seawater including the six EDCs in solution (100 ng mL−1 each). These concentrations were chosen to be close to those found in the environment as well as to be comparable to previous studies [40,41]. The suspension was kept at 22°C, during 24 h, with agitation (220 rounds per minute) and in dark condition, to enhance contact between MPs and EDCs and to reach the equilibrium.

Experimental design for the study of the sorption of six EDCs onto MPs. Three steps were performed: step 1 corresponds to the determination of EDCs adsorbed onto solid phase, step 2 corresponds to the determination of EDCs remained in liquid phase and step 3 corresponds to the determination of EDCs adsorbed on glass tube (EDC: endocrine disrupting compound; MP: microplastic; CH2Cl2: dichloromethane; DMF: dimethylformamide; ACN: acetonitrile; HPLC-FD: high performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence detector).

After 24 h, the solution was filtered using a glass filtration system and a cellulose nitrate filter. As a first step (step 1), the EDCs adsorbed onto the MPs retained on the filter were measured. For that, two successive solid–liquid extractions of the filter with CH2Cl2 (2 × 5 mL) were performed. Before the evaporation of the organic extract, 200 µL of DMF was added in order to prevent a potential loss of the most volatile compounds during the evaporation. After the evaporation, the remaining DMF volume was adjusted to 1 mL using ACN before the injection in HPLC for the determination of EDC concentrations. As a second step (step 2), the concentrations of EDCs remaining in the filtered seawater solution (the filtrate) were determined by a direct injection in HPLC. When the concentrations were below the detection limits (Table S1), 24 mL of the filtrate was extracted two times with CH2Cl2 with the same technique used for extraction of the filter in step 1. Finally, as a third step (step 3) with the aim to calculate the recovery of the EDCs in the experiment, all the glassware used for the filtration, i.e., the tube and the filtration system, were rinsed with 2 mL CH2Cl2 and 2 mL ACN. Following the same preparation of sample as explained above for filters (DMF addition, evaporation and volume adjustment with ACN, HPLC analysis), the EDC concentrations were then determined. This last step was added to evaluate the fraction of the EDCs adsorbed on glass walls during the experiment. In order to calculate the recovery of the manipulation, this protocol was performed without the addition of MPs in the tubes.

The distribution coefficient (K d) is the parameter which represents the sorption capacity of the EDCs onto the MPs. This coefficient is known to depend on the MP type, the sorbed compound properties and the experimental conditions. In order to determine the K d value of each compound, the EDC level sorbed onto the MPs (C s) was divided by its concentration in the solution (C w) at the equilibrium and was expressed as L kg−1.

3.2 Sorption kinetic

To determine the time needed to reach the equilibrium of EDC sorption onto PE MPs, i.e., the equilibrium between the sorption and desorption, the kinetic sorption was determined between 0 and 96 h and involved nine sampling times. Exposure conditions as well as MP and EDC concentrations were similar to those described for K d determination; four replicates were performed at each sampling time. The concentrations of each EDC sorbed on MPs were determined by solvent extractions involving CH2Cl2, as explained in step 1 of the protocol presented in the latter section. The evolution of the EDC concentrations extracted from PE MPs related to the time allowed to determine the equilibrium time for each compound. Then, the highest equilibration time found for the EDCs was chosen as the duration applied for the determination of both the recoveries and the distribution coefficients.

3.3 Influence of the polymer nature on the sorption of 4-n-NP

To highlight the influence of the MP type onto the sorption of organic compounds, the 4-n-NP was chosen as a chemical model for experiments, involving PE and PP MPs, with a similar size range, i.e., 53–100 µm. Exposure conditions were the same for both MP types and involved 72 h of contact, 25 mL of seawater at 30 PSU, 22°C, concentrations of 0.800 mg mL−1 and 10 µg mL−1 for MPs and 4-n-NP, respectively. Triplicates were performed. The levels of 4-n-NP sorbed onto the MPs were then determined as described in Section 4.2.

3.4 EDC analysis by HPLC-fluorescence detector (FD)

EDCs were analyzed in the different solutions, i.e., MP extracts, in seawater and tube-rinsed solution, using a HPLC system (Dionex Thermo Scientific) equipped with a quaternary pump, a thermally controlled auto-sampler (set at 10°C), a column oven (40°C) and a programmable FD. Chromatographic separation was performed using a C18 column (Kinetex, 150 mm × 2.1 mm, particle diameter 2.6 µm) and a flow rate of 0.735 mL min−1. The mobile phase constituted of a mix of ultrapure water (A) and ACN (B). The gradient performed for the analysis was as follows: t = 0–4.2 min: 37% B; t = 4.2–13.8 min: increase of B from 37 to 80%; t = 13.8–14.9 min: increase of % B from 80 to 100% and stays at 100% B until the end of the acquisition time (17.6 min). Excitation and emission wavelengths were 271/334 nm for EE2 and 290/340 nm for the other compounds. Acquisition data treatment was done by Chromeleon 7 software. The quantification of EDCs was performed by external calibration with eight concentration levels from 1 to 200 ng mL−1 in two different solvents, i.e., ACN and seawater. For each concentration level, six calibration solutions were analyzed. Different parameters of method validation were evaluated, such as the limit of detection (LOD), the limit of quantification (LOQ), the linearity, the accuracy and the repeatability.

3.5 Statistical analysis

Result treatment and graphs were performed using the Microsoft Excel® software (version 2019).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Validation of the EDC quantification by HPLC

The EDC quantification by HPLC performed by external calibration, in both ACN and seawater, was first validated for parameters, such as LOD and LOQ, linearity, accuracy and repeatability. The results obtained for the validation are detailed in Tables S1 and S2. All the coefficients of determination (R 2) of the EDC calibration curves were higher than 0.99, except for 4-n-NP in seawater (>0.96). This difference could be attributed to the highest hydrophobicity of 4-n-NP among the other compounds, leading to a lower solubility in seawater, as well as the possible adsorption on vials. The detection and quantification limits were calculated for the six EDCs with values ranging from 0.137 to 4.152 ng mL−1 and from 0.471 to 13.701 ng mL−1 (n = 6), respectively. After the injection of three solutions of EDCs individually prepared and solubilized in seawater at 100 ng mL−1 each, the accuracy and the repeatability were assessed (Table S2). The results of the analytical method were different according to the compound, probably depending on their polarity. In seawater, the method can be considered as repeatable because the relative standard deviations (RSD) were lower than 2.64% (n = 3) for most of the compounds, except for 4-n-NP (9.34% [n = 3]). Nevertheless, the relative biases (RB) were quite high, with values around or higher than 15% for five out of six compounds. EE2 was the only one showing an acceptable RB (1.5% [n = 3]). Better accuracy and repeatability were obtained using ACN as solvent for the solubilization of the six EDCs. The RB ranged from 0.29 to 3.07% (n = 3), and the RSD values were less than 2% (excepted for EE2 at 3.92%, n = 3) (Table S2). The lack of accuracy of the method observed using seawater solvent, could be attributed to the sorption of the compounds onto the glassware used for the preparation of the solutions, or to their precipitation, due to a lower solubility in seawater compared to ACN.

4.2 Recovery determination

Table 2 presents the recovery of the protocol developed to assess the sorption of the six EDCs onto the MPs. To reach this objective, the protocol was performed without the addition of MPs in the tube, as a first point of protocol validation. As a consequence, Step 1, corresponding to the extraction of the filter containing the MPs, was not performed and is presented as C s in Table 3. The total recoveries (Step 2 + Step 3) ranged from 59.73 ± 14.265% (n = 3) to 90.21 ± 6.33% (n = 3) for 4-n-NP and E2, respectively. The highest values, higher than 85%, were obtained for the three compounds with the highest solubility in water among the six studied, i.e., E2, EE2 and 4-t-BP. On the contrary, the lowest values, 59.73 ± 14.265% (n = 3), 66.53 ± 11.64% (n = 3) and 74.77 ± 15.25% (n = 3)% were obtained for the lowest water-soluble compounds, 4-t-OP, 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP, respectively. The recovery was also calculated for Step 2, which corresponded to the EDC levels in the seawater. It corresponded to the recovery obtained for Step 2.1 or 2.2 when the concentration of EDCs in the liquid phase was lower than LOQ for the direct analysis performed in Step 2.1, requiring Step 2.2. The same trend was observed for the total, with values reaching only 57.74 ± 9.97% (n = 3) and 46.23 ± 11.76% (n = 3) for 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP, respectively. Moreover, the loss of compounds due to the sorption onto the glassware can be found in the line “Step 3” of Table 2. Values of 8.79 and 13.50% were found for the highest hydrophobic compounds, 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP, respectively. The same result was shown by Bakir et al. [16,17] who reported a loss of bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) up to 40% on glass system. For the other compounds, their loss by sorption onto glassware can be considered as negligible, reaching 1–4%. The adsorption of the compounds onto the filter could also be an explanation. Besides, the eluent strength of the solvent used for the extraction of the compounds from the glassware was not enough to desorb the most hydrophobic compounds, i.e., 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP. The hexane would have probably better desorbed 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP from the glassware, for which the compounds had likely strong interactions. In this case, the recovery of Step 3 would have been higher. Nevertheless, the choice of a more hydrophobic solvent than CH2Cl2 could have decreased the extraction of the compounds with lower hydrophobicity. For further experiments, successive extractions with different solvents or the use of mix of solvents could be tested.

Recovery of the different steps of the protocol for the study of the six EDC sorption (percentages, average ± SD, n = 3)

| APs | Estrogens | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-t-BP | 4-t-OP | 4-n-OP | 4-n-NP | EE2 | E2 | |

| Step 2 (% in the filtrate of seawater) | 89.08 ± 2.97 | 71.30 ± 14.79 | 57.74 ± 9.97 | 46.23 ± 11.76 | 83.87 ± 3.28 | 89.60 ± 6.25 |

| Step 3 (% adsorbed onto the glassware) | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 3.47 ± 0.46 | 8.79 ± 1.67 | 13.50 ± 2.50 | 0.84 ± 0.16 | 0.61 ± 0.08 |

| Total | 89.81 ± 3.05 | 74.77 ± 15.25 | 66.53 ± 11.64 | 59.73 ± 14.265 | 84.71 ± 3.44 | 90.21 ± 6.33 |

4-t-BP: 4-t-butylphenol; 4-t-OP: 4-t-octylphenol; 4-n-OP: 4-n-octylphenol; 4-n-NP: 4-n-nonylphenol; E2: 17β-estradiol; EE2: 17α-ethinylestradiol and MPs: microplastics.

Concentrations and distribution coefficient of six EDCs studied after sorption experiment onto PE MPs and distribution coefficients (n = 4)

| APs | Estrogens | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-t-BP(*) | 4-t-OP | 4-n-OP | 4-n-NP(*) | E2(*) | EE2 | |

| C s (ng mg−1) | <LOQ | 7.07 ± 3.05 | 44.9 ± 5.95 | 77.3 ± 9.18 | <LOQ | 2.69 ± 1.41 |

| C w (ng mL−1) | 33.9 ± 19.7 | 48.1 ± 14.7 | 34.4 ± 13.8 | <LOQ | 70.1 ± 33.2 | 62.3 ± 26.8 |

| K d (L kg−1) | 12.1 ± 8.30 | 171 ± 120 | 1,579 ± 1,004 | 106 ± 12.6 | 2.28 ± 0.974 | 45.3 ± 21.8 |

(*): Value estimated using the LOD in liquid phase (4-n-NP) and solid phase (4-t-BP and E2).

4-t-OP: 4-t-octylphenol; 4-n-OP: 4-n-octylphenol; EE2: 17α-ethinylestradiol.

C s: solid phase concentration; C w: liquid phase concentration; K d: distribution coefficient.

4.3 Sorption kinetic

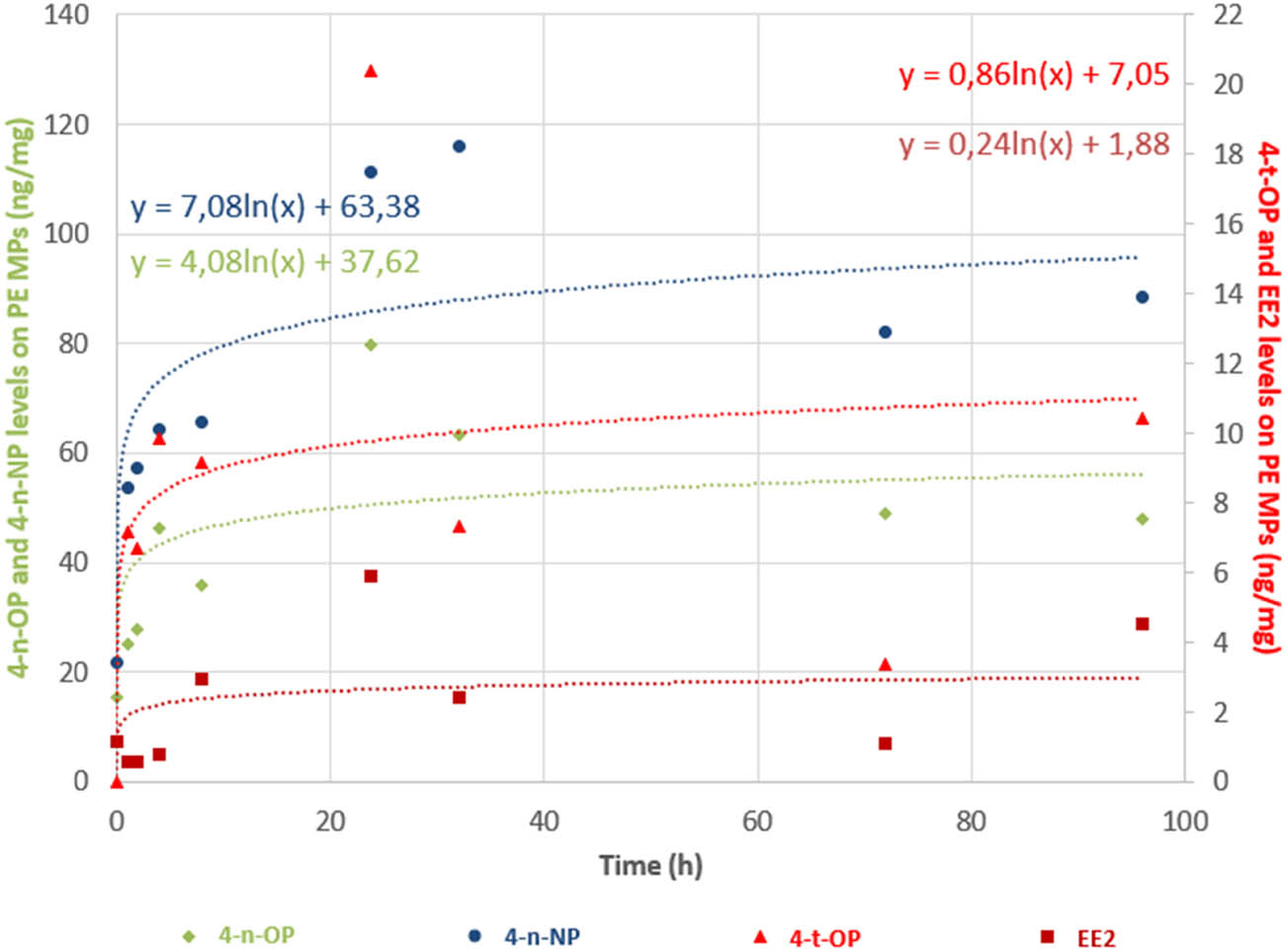

Figure 2 presents the evolution of the levels of EDCs sorbed onto PE MPs related to the time of contact, to assess the equilibration time of sorption. Two out of the six studied compounds were not detected in the extracts of MPs. They corresponded to 4-t-BP and E2 which are the two compounds with the lowest hydrophobicity. In the seawater, the recovery of these two compounds during the time were found high but variable (62.8 ± 31 and 72.8 ± 27% for 4-t-BP and E2, respectively [n = 8]). To enable the assessment of the sorption kinetic of these two compounds, it seems necessary to increase the MP concentration used in the experiment and thus the solid/liquid ratio, in order to reach the analytical requirement for sensitivity. Indeed, in case of low adsorption occurrence, a higher solid/solution ratio is recommended to meet the experimental needs, as described in guidelines of adsorption/desorption of chemicals on soils [42].

Sorption kinetics of four EDCs onto MPs of PE. The kinetic curve was based on logarithmic model. 4-n-OP: 4-n-octylphenol (green); 4-n-NP: 4-n-nonylphenol (blue); 4-t-OP: 4-t-octylphenol (red); EE2: 17α-ethinylestradiol (purple).

The results shown in Figure 2 also highlight that the levels of sorbed compounds onto MPs were stable from 24 h until the end of the experiment. This means that the equilibrium of sorption reached quite rapidly, i.e., before 24 h. Figure 2 also allows comparing the differences of sorption between the four EDCs. The levels of sorption are inversely correlated to the solubility of the studied compounds. The most sorbed compound was 4-n-NP, with 80% of the nominal concentration on the MPs.

4.4 Distribution coefficient

The distribution coefficients were calculated in function of the EDC levels in two phases, solid and liquid. After an equilibration time of 24 h, the distribution coefficients of three compounds, 4-t-OP, 4-n-OP and EE2, were calculated and are presented in Table 3. As the most hydrophobic compound, 4-n-NP, was not detected in the liquid phase. Its distribution coefficient has been determined using the LOD value as the C w; its K d can be thus estimated to be 106.423 (±12.649, n = 4) L kg−1. Concerning 4-t-BP and E2, their K d could be estimated to be 12.141 (±8.303, n = 4) and 2.276 (±0.974, n = 4) L kg−1, respectively, using the LOD values as C s.

Other results of distribution coefficients of organic contaminants onto MPs are reported in Table 4, for both types of MPs and equilibrium times. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first one investigating the K d values of APs onto MP surfaces in marine conditions. Mean values were 170.914 ± 119.784 and 1579.478 ± 1003.520 L kg−1 (n = 4) for 4-t-OP and 4-n-OP, respectively. Compared to other organic compounds, they are relatively low. For example, the K d of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) onto PE particle reached more than 50.000 L kg−1 [40]. For the estrogen compounds, EE2, the K d was lower than the value reported by Wu et al. [40], 45.286 vs 312 L kg−1. On the contrary, similar K d value (2.5 L kg−1) was reported for E2 onto PE MPs in another recent studies [41] after 24 h of equilibrium time. Recently, Hu et al. [47] demonstrated that the adsorption capacity of MPs (PS, PE and PVC) to E2 is stronger than the capacity of the soil. Regarding the equilibrium time, most of the studies reported that it is reached between 24 and 48 h. Karapanagioti and Klontza found an equilibrium time of many days [44]. This difference can be notably explained by larger MPs used (size ranging from 2 to 3 mm), presenting a lower active surface. Llorca et al. [45] also reported an equilibrium time of 7 days for the acid perfluoro-octanoic (PFOA) on PE MPs (3–16 µm) and up to 7 days for PS MPs (10 µm).

Distribution coefficients and equilibration time of different organic contaminants sorbed onto MP surface

| Organic contaminant | log K ow | MP type | MP size (µm) | Equilibrium time (h) | K d (L kg−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenanthrene | 4.5 | PE | 200–250 | 24 | 38,100 | [43] |

| PP | 24 | 2,190 | ||||

| PVC | 24 | 1,650–1,690 | ||||

| PE | 200–250 | 24 | 51,532 | [15] | ||

| PVC | 24 | 2,285 | ||||

| PE | 2,000–3,000 | >80 days | 13,000 | [44] | ||

| PP | 20–40 days | 380 | ||||

| POM | >80 days | 7,400 | ||||

| PEP | >80 days | >12,000 | ||||

| DDT | 6.36 | PE | 200–250 | 48 | 96,892 | [16,17] |

| PVC | 24 | 104,785 | ||||

| PFOA | 0.7 | PE | 200–250 | 24 | 496 | |

| PVC | 24 | 7 | ||||

| DEHP | 7.5 | PE | 200–250 | 24 | 98,494 | |

| PVC | 24 | 11,917 | ||||

| PFOA | 0.7 | PE | 3–16 | 7 days | 64 | [45] |

| PS | 10 | >7 days | ||||

| PCB 77 | 6.72 | PP | >180 | 8 | 1,183 | [46] |

| Carbamazepine | 2.45 | PE | 250–280 | 48 | 191 | [40] |

| 4-MBC | 5.1 | PE | 48 | 53,225 | ||

| Triclosan | 4.76 | PE | 48 | 5,140 | ||

| EE2 | 3.67 | PE | 48 | 312 | ||

| E2 | 4.01 | PE | 250–300 | 48 | 2,5 | [41] |

| 4-t-OP | 3.70 | PE | 53–100 | 24 | 1,580 | This study |

| 4-t-OP | 4.12 | 171 | ||||

| EE2 | 3.67 | 45 |

4.5 Influence of MP type on NP sorption

The levels of 4-n-NP sorbed onto two types of MPs were determined after 72 h of equilibrium. They reached 2260.08 ± 198.67 and 200.12 ± 25.26 ng mg−1 (n = 3) for MPs made of PE and PP, respectively. These results demonstrated that the levels of 4-n-NP sorbed onto MPs of PE were ten times higher than PP MPs. Hence, the polymer nature plays an important role in the sorption mechanisms. The time of contact was increased to 72 h in this experimentation, instead of 24 h for the other experiments. Nevertheless, 72 h was not sufficient to reach equilibrium for distribution of 4-n-NP on PP MPs, since some equilibrium times were determined as higher than 20–40 days in some studies, e.g., for phenanthrene sorbed onto PP particles [43]. Second, the size of the MPs was similar for both PE and PP types but other physical properties could be determined, such as the surface area and the crystalline level, to highlight their influences on sorption mechanism [18,48]. Considering the role of the polymer type on the adsorption process, Teuten et al. [43] demonstrated a K d value for PE 20 times higher than for PP for the same size of particles (200–250 µm). These authors also reported that the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface of PE is three times higher than for PP polymers. Moreover, the difference of sorption mechanism onto PE and PP MPs was also reported by Karapanagioti and Klontza [44]. Accordingly, PE had a higher affinity for organic compounds than PP (around 40 times). These authors also reported that the sorption onto PP polymer was faster but strongly affected by the physico-chemical conditions of the solution, such as the salinity, which increased the sorption behavior. Hu et al. [47] found the sorption capacity of PS > PE > PVC MPs to E2.

5 Conclusion

The present study aimed at assessing the sorption of six EDCs onto MPs in marine conditions. The chosen compounds were four APs, including 4-t-BP, 4-t-OP, 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP, as well as two estrogens, E2 and EE2. To the best of our knowledge, the distribution coefficients of NPs on PE MPs have never been determined before. Regarding estrogens, the results on EE2 (equilibrium time and distribution coefficient) were in the same order of magnitude than others found in the literature. Moreover, estimates of 4-t-BP, E2, 4-n-NP distribution coefficients were made. Then, the sorption mechanisms were found strongly dependent on the hydrophobicity of the studied compounds (4-n-NP > 4-n-OP > 4-t-OP > EE2 > 4-t-BP > E2), as well as the type of MPs. Indeed, the sorption of 4-n-NP onto PE MPs was found to be ten times higher than onto PP MPs.

Due to the hydrophobicity of the compounds, the analytical method used, i.e., HPLC-FD, showed a lack of accuracy for their direct quantification in seawater. Moreover, working with environmental concentrations of the EDCs was difficult since they were very close to the quantification limits. Concerning the protocol developed for the sorption determination, the main critical point was the low procedure recoveries, lower than 70% for most of the hydrophobic compounds, i.e., 4-n-OP and 4-n-NP. In addition, the choice of compounds with a wide range of hydrophobicity was challenging from an analytical and methodological point of view. To study the sorption of individual compound onto MPs could also be interesting, to determine if the behavior would be the same than in a mix. Finally, the assessment of the sorption of environmental organic contaminants onto the wide types of existing MPs remains a large investigation field, considering the diversity of polymers and other MP characteristics, such as the size, the additives, the crystallinity, the surface area and the ageing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to greatly thank MiPlAqua project (Pays de la Loire Region) for its technical and scientific support.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by NAFOSTED under grant number 105.08-2019.337.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization (N.N.P., A.Z.V., L.P.); methodology (N.N.P., A.Z.V., L.P.); writing – original draft preparation (N.N.P., T.T.D., T.P.Q.L.); writing – review and editing (N.N.P., T.T.D., T.P.Q.L., A.Z.V., L.P.).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the Supplementary Information file.

References

[1] Arthur C, Baker J, Bamford H. Effects and fate of microplastic marine debris, NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR & R-30.NOAA. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, September 9–11, 2008. Washington: Silver Spring; 2009. p. 530.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ahmed Q, Ali QM, Bat L, Öztekin A, Memon S, Baloch A. Preliminary study on abundance of microplastic in sediments and water samples along the coast of Pakistan (Sindh and Balochistan)-Northern Arabian Sea. Turkish J Fish Aquat Sci. 2021;22(1):TRJFAS19998.10.4194/TRJFAS19998Search in Google Scholar

[3] Free CM, Jensen OP, Mason SA, Eriksen M, Williamson NJ, Boldgiv B. High-levels of microplastic pollution in a large, remote, mountain lake. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;85:156–63.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Ozguler U, Demir A, Kayadelen G, Kideyş A. Riverine microplastic loading to mersin bay, Turkey on the north-eastern mediterranean. Turkish J Fish Aquat Sci. 2022;22(7):TRJFAS20253.10.4194/TRJFAS20253Search in Google Scholar

[5] Tan I. Preliminary assessment of microplastic pollution index: a case study in Marmara sea. Turkish J Fish Aquat Sci. 2022;22(7):TRJFAS20537.10.4194/TRJFAS20537Search in Google Scholar

[6] Woodall LC, Sanchez-Vidal A, Canals M, Paterson GLJ, Coppock R, Sleight V, et al. The deep sea is a major sink for microplastic debris. R Soc Open Sci. 2014;1:140317.10.1098/rsos.140317Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Acosta-Coley I, Olivero-Verbel J. Microplastic resin pellets on an urban tropical beach in Colombia. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187(7):1–14.10.1007/s10661-015-4602-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Andrady AL. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;62:1596–605.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Blettler MC, Ulla MA, Rabuffetti AP, Garello N. Plastic pollution in freshwater ecosystems: macro-, meso-, and microplastic debris in a floodplain lake. Environ Monit Assess. 2017;189(11):1–13.10.1007/s10661-017-6305-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Enyoh CE, Verla AW, Verla EN, Ibe FC, Amaobi CE. Airborne microplastics: a review study on method for analysis, occurrence, movement and risks. Environ Monit Assess. 2019;191(11):1–17.10.1007/s10661-019-7842-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ustabasi GS, Baysal A. Occurrence and risk assessment of microplastics from various toothpastes. Environ Monit Assess. 2019;191(7):1–8.10.1007/s10661-019-7574-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Wright SL, Rowe D, Thompson RC, Galloway TS. Microplastic ingestion decreases energy reserves in marine worms. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1031–3.10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.068Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Law KL. Plastics in the marine environment. Annu Rev Mar Sci. 2017;9:205–29.10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060409Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Teuten EL, Saquing JM, Knappe DR, Barlaz MA, Jonsson S, Björn A, et al. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2009;364(1526):2027–45.10.1098/rstb.2008.0284Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Bakir A, Rowland SJ, Thompson RC. Competitive sorption of persistent organic pollutants onto microplastics in the marine environment. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64:2782–9.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.09.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Bakir A, Rowland SJ, Thompson RC. Enhanced desorption of persistent organic pollutants from microplastics under simulated physiological conditions. Environ Pollut. 2014a;185:16–23.10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Bakir A, Rowland SJ, Thompson RC. Transport of persistent organic pollutants by microplastics in estuarine conditions. Estuarine Coast Shelf Sci. 2014b;140:14–21.10.1016/j.ecss.2014.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[18] Fu L, Li J, Wang G, Luan Y, Dai W. Adsorption behavior of organic pollutants on microplastics. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;217:112207.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112207Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Luo H, Liu C, He D, Xu J, Sun J, Li J, et al. Environmental behaviors of microplastics in aquatic systems: a systematic review on degradation, adsorption, toxicity and biofilm under aging conditions. J Hazard Mater. 2022;423:126915.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126915Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Rochman CM. The complex mixture, fate and toxicity of chemicals associated with plastic debris in the marine environment. Marine anthropogenic litter. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 117–40.10.1007/978-3-319-16510-3_5Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hirai H, Takada H, Ogata Y, Yamashita R, Mizukawa K, Saha M, et al. Organic micropollutants in marine plastics debris from the open ocean and remote and urban beaches. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;62(8):1683–92.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.06.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Heskett M, Takada H, Yamashita R, Yuyama M, Ito M, Geok YB, et al. Measurement of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in plastic resin pellets from remote islands: toward establishment of background concentrations for International Pellet Watch. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64(2):445–8.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Ogata Y, Takada H, Mizukawa K, Hirai H, Iwasa S, Endo S, et al. International Pellet Watch: global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. 1. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs. Mar Pollut Bull. 2009;58(10):1437–46.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.06.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Rios LM, Jones PR, Moore C, Narayan UV. Quantitation of persistent organic pollutants adsorbed on plastic debris from the Northern Pacific Gyre’s “eastern garbage patch”. J Environ Monit. 2010;12(12):2226–36.10.1039/c0em00239aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jiménez-Skrzypek G, Hernández-Sánchez C, Ortega-Zamora C, González-Sálamo J, González-Curbelo MÁ, Hernández-Borges J. Microplastic-adsorbed organic contaminants: analytical methods and occurrence. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2021;136:116186.10.1016/j.trac.2021.116186Search in Google Scholar

[26] Santana-Viera S, Montesdeoca-Esponda S, Guedes-Alonso R, Sosa-Ferrera Z, Santana-Rodríguez JJ. Organic pollutants adsorbed on microplastics: analytical methodologies and occurrence in oceans. Trends Environ Anal Chem. 2021;29:e00114.10.1016/j.teac.2021.e00114Search in Google Scholar

[27] Purdom CE, Hardiman PA, Bye VVJ, Eno NC, Tyler CR, Sumpter JP. Estrogenic effects of effluents from sewage treatment works. Chem Ecol. 1994;8(4):275–85.10.1080/02757549408038554Search in Google Scholar

[28] Langston WJ, Burt GR, Chesman BS. Feminisation of male clams Scrobicularia plana from estuaries in Southwest UK and its induction by endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;333:173–84.10.3354/meps333173Search in Google Scholar

[29] Tankoua OF, Amiard-Triquet C, Denis F, Minier C, Mouneyrac C, Berthet B. Physiological status and intersex in the endobenthic bivalve Scrobicularia plana from thirteen estuaries in northwest France. Environ Pollut. 2012;167:70–7.10.1016/j.envpol.2012.03.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Miège C, Gabet V, Coquery M, Karolak S, Jugan ML, Oziol L, et al. Evaluation of estrogenic disrupting potency in aquatic environments and urban wastewaters by combining chemical and biological analysis. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2009;28(2):186–95.10.1016/j.trac.2008.11.007Search in Google Scholar

[31] Bertin A, Inostroza PA, Quiñones RA. Estrogen pollution in a highly productive ecosystem off central-south Chile. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;62(7):1530–7.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.04.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Tetreault GR, Bennett CJ, Shires K, Knight B, Servos MR, McMaster ME. Intersex and reproductive impairment of wild fish exposed to multiple municipal wastewater discharges. Aquat Toxicol. 2011;104(3–4):278–90.10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.05.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] European Commission. Directive 2013/39/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 August 2013 amending Directives 2000/60/EC and 2008/105/EC as regards priority substances in the field of water policy. J Eur Union L. 2013;226:1.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Pojana G, Gomiero A, Jonkers N, Marcomini A. Natural and synthetic endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) in water, sediment and biota of a coastal lagoon. Environ Int. 2007;33(7):929–36.10.1016/j.envint.2007.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Froehner S, Machado KS, Stefan E, Bleninger T, Da Rosa EC, de Castro Martins C. Occurrence of selected estrogens in mangrove sediments. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64(1):75–9.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.10.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Ferguson PL, Iden CR, Brownawell BJ. Distribution and fate of neutral alkylphenol ethoxylate metabolites in a sewage-impacted urban estuary. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:2428–35.10.1021/es001871bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kurihara R, Watanabe E, Ueda Y, Kakuno A, Fujii K, Shiraishi F, et al. Estrogenic activity in sediments contaminated by nonylphenol in Tokyo Bay (Japan) evaluated by vitellogenin induction in male mummichogs (Fundulus heteroclitus). Mar Pollut Bull. 2007;54:1315–20.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.06.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Petrovic M, Fernandez-Alba AR, Borrull F, Marce RM, Gonzalez ME, Barcelo D. Occurrence and distribution of nonionic surfactants, their degradation products, and linear alkylbenzene sulfonates in coastal waters and sediments in Spain. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2002;21:37–46.10.1002/etc.5620210106Search in Google Scholar

[39] Phuong NN, Zalouk-Vergnoux A, Poirier L, Kamari A, Châtel A, Mouneyrac C, et al. Is there any consistency between the microplastics found in the field and those used in laboratory experiments? Environ Pollut. 2016;211:111–23.10.1016/j.envpol.2015.12.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Wu C, Zhang K, Huang X, Liu J. Sorption of pharmaceuticals and personal care products to polyethylene debris. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(9):8819–26.10.1007/s11356-016-6121-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Daugherty M, Conte M, Weber JC. Adsorption of organic pollutants to microplastics: the effects of dissolved organic matter. Northwest Univ Semester Environ Sci. 2016;1–27.Search in Google Scholar

[42] OECD, G. 106 for the testing of chemicals-Adsorption–Desorption Using a Batch Equilibrium Method. Paris: organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Teuten EL, Rowland SJ, Galloway TS, Thompson RC. Potential for plastics to transport hydrophobic contaminants. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:7759–64.10.1021/es071737sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Karapanagioti HK, Klontza I. Testing phenanthrene distribution properties of virgin plastic pellets and plastic eroded pellets found on Lesvos island beaches (Greece). Mar Environ Res. 2008;65(4):283–90.10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.11.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Llorca M, Schirinzi G, Martínez M, Barceló D, Farré M. Adsorption of perfluoroalkyl substances on microplastics under environmental conditions. Environ Pollut. 2018;235:680–91.10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.075Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Zhan Z, Wang J, Peng J, Xie Q, Huang Y, Gao Y. Sorption of 3, 3′, 4, 4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl by microplastics: a case study of polypropylene. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016;110(1):559–63.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.05.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Hu B, Li Y, Jiang L, Chen X, Wang L, An S, et al. Influence of microplastics occurrence on the adsorption of 17β-estradiol in soil. J Hazard Mater. 2020;400:123325.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123325Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Liu X, Xu J, Zhao Y, Shi H, Huang CH. Hydrophobic sorption behaviors of 17β-estradiol on environmental microplastics. Chemosphere. 2019;226:726–35.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.162Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening

- Prefatory in silico studies and in vitro insecticidal effect of Nigella sativa (L.) essential oil and its active compound (carvacrol) against the Callosobruchus maculatus adults (Fab), a major pest of chickpea

- Polymerized methyl imidazole silver bromide (CH3C6H5AgBr)6: Synthesis, crystal structures, and catalytic activity

- Using calcined waste fish bones as a green solid catalyst for biodiesel production from date seed oil

- Influence of the addition of WO3 on TeO2–Na2O glass systems in view of the feature of mechanical, optical, and photon attenuation

- Naringin ameliorates 5-fluorouracil elicited neurotoxicity by curtailing oxidative stress and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 pathway

- GC-MS profile of extracts of an endophytic fungus Alternaria and evaluation of its anticancer and antibacterial potentialities

- Green synthesis, chemical characterization, and antioxidant and anti-colorectal cancer effects of vanadium nanoparticles

- Determination of caffeine content in coffee drinks prepared in some coffee shops in the local market in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

- A new 3D supramolecular Cu(ii) framework: Crystal structure and photocatalytic characteristics

- Bordeaux mixture accelerates ripening, delays senescence, and promotes metabolite accumulation in jujube fruit

- Important application value of injectable hydrogels loaded with omeprazole Schiff base complex in the treatment of pancreatitis

- Color tunable benzothiadiazole-based small molecules for lightening applications

- Investigation of structural, dielectric, impedance, and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-modified barium titanate composites for biomedical applications

- Metal gel particles loaded with epidermal cell growth factor promote skin wound repair mechanism by regulating miRNA

- In vitro exploration of Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) mushroom fruiting bodies: Potential antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agent

- Alteration in the molecular structure of the adenine base exposed to gamma irradiation: An ESR study

- Comprehensive study of optical, thermal, and gamma-ray shielding properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses

- Lewis acids as co-catalysts in Pd-based catalyzed systems of the octene-1 hydroethoxycarbonylation reaction

- Synthesis, Hirshfeld surface analysis, thermal, and selective α-glucosidase inhibitory studies of Schiff base transition metal complexes

- Protective properties of AgNPs green-synthesized by Abelmoschus esculentus on retinal damage on the virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in diabetic rat

- Effects of green decorated AgNPs on lignin-modified magnetic nanoparticles mediated by Cydonia on cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by green mediated silver nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica bark aqueous extract

- Preparation of newly developed porcelain ceramics containing WO3 nanoparticles for radiation shielding applications

- Utilization of computational methods for the identification of new natural inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase in inflammation therapy

- Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors

- Clay-based bricks’ rich illite mineral for gamma-ray shielding applications: An experimental evaluation of the effect of pressure rates on gamma-ray attenuation parameters

- Stability kinetics of orevactaene pigments produced by Epicoccum nigrum in solid-state fermentation

- Treatment of denture stomatitis using iron nanoparticles green-synthesized by Silybum marianum extract

- Characterization and antioxidant potential of white mustard (Brassica hirta) leaf extract and stabilization of sunflower oil

- Characteristics of Langmuir monomolecular monolayers formed by the novel oil blends

- Strategies for optimizing the single GdSrFeO4 phase synthesis

- Oleic acid and linoleic acid nanosomes boost immunity and provoke cell death via the upregulation of beta-defensin-4 at genetic and epigenetic levels

- Unraveling the therapeutic potential of Bombax ceiba roots: A comprehensive study of chemical composition, heavy metal content, antibacterial activity, and in silico analysis

- Green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extract and investigation of its anti-human colorectal cancer application

- The adsorption of naproxen on adsorbents obtained from pepper stalk extract by green synthesis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by silver nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan polymers mediated by Pistacia atlantica extract under ultrasound condition

- In vitro protective and anti-inflammatory effects of Capparis spinosa and its flavonoids profile

- Wear and corrosion behavior of TiC and WC coatings deposited on high-speed steels by electro-spark deposition

- Therapeutic effects of green-formulated gold nanoparticles by Origanum majorana on spinal cord injury in rats

- Melanin antibacterial activity of two new strains, SN1 and SN2, of Exophiala phaeomuriformis against five human pathogens

- Evaluation of the analgesic and anesthetic properties of silver nanoparticles supported over biodegradable acacia gum-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- Review Articles

- Role and mechanism of fruit waste polyphenols in diabetes management

- A comprehensive review of non-alkaloidal metabolites from the subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae)

- Discovery of the chemical constituents, structural characteristics, and pharmacological functions of Chinese caterpillar fungus

- Eco-friendly green approach of nickel oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications

- Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration

- Rapid Communication

- Determination of the contents of bioactive compounds in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Comparison of commercial and wild samples

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: The protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α”

- Topical Issue on Phytochemicals, biological and toxicological analysis of aromatic medicinal plants

- Anti-plasmodial potential of selected medicinal plants and a compound Atropine isolated from Eucalyptus obliqua

- Anthocyanin extract from black rice attenuates chronic inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mouse model by modulating the gut microbiota

- Evaluation of antibiofilm and cytotoxicity effect of Rumex vesicarius methanol extract

- Chemical compositions of Litsea umbellata and inhibition activities

- Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles using Rhynchosia capitata leaf extract and their biological activities

- GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activities of some plants belonging to the genus Euphorbia on selected bacterial isolates

- The abrogative effect of propolis on acrylamide-induced toxicity in male albino rats: Histological study

- A phytoconstituent 6-aminoflavone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress mediated synapse and memory dysfunction via p-Akt/NF-kB pathway in albino mice

- Anti-diabetic potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder: Phytochemistry (GC-MS analysis), α-amylase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, in vivo hypoglycemic, and biochemical analysis

- Assessment of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the Cassia angustifolia aqueous extract against SW480 colon cancer

- Biochemical analysis, antioxidant, and antibacterial efficacy of the bee propolis extract (Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera) against Staphylococcus aureus-induced infection in BALB/c mice: In vitro and in vivo study

- Assessment of essential elements and heavy metals in Saudi Arabian rice samples underwent various processing methods

- Two new compounds from leaves of Capparis dongvanensis (Sy, B. H. Quang & D. V. Hai) and inhibition activities

- Hydroxyquinoline sulfanilamide ameliorates STZ-induced hyperglycemia-mediated amyleoid beta burden and memory impairment in adult mice

- An automated reading of semi-quantitative hemagglutination results in microplates: Micro-assay for plant lectins

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assessment of essential and toxic trace elements in traditional spices consumed by the population of the Middle Eastern region in their recipes

- Phytochemical analysis and anticancer activity of the Pithecellobium dulce seed extract in colorectal cancer cells

- Impact of climatic disturbances on the chemical compositions and metabolites of Salvia officinalis

- Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils of Urginea maritima and Allium sativum

- Phytochemical analysis and antifungal efficiency of Origanum majorana extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi causing tomato damping-off diseases

- Special Issue on 4th IC3PE

- Graphene quantum dots: A comprehensive overview

- Studies on the intercalation of calcium–aluminium layered double hydroxide-MCPA and its controlled release mechanism as a potential green herbicide

- Synergetic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis by zinc ferrite-anchored graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet for the removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light irradiation

- Exploring anticancer activity of the Indonesian guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) fraction on various human cancer cell lines in an in vitro cell-based approach

- The comparison of gold extraction methods from the rock using thiourea and thiosulfate

- Special Issue on Marine environmental sciences and significance of the multidisciplinary approaches

- Sorption of alkylphenols and estrogens on microplastics in marine conditions

- Cytotoxic ketosteroids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp.

- Antibacterial and biofilm prevention metabolites from Acanthophora spicifera

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part II

- Green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial activities of cobalt nanoparticles produced by marine fungal species Periconia prolifica

- Combustion-mediated sol–gel preparation of cobalt-doped ZnO nanohybrids for the degradation of acid red and antibacterial performance

- Perinatal supplementation with selenium nanoparticles modified with ascorbic acid improves hepatotoxicity in rat gestational diabetes

- Evaluation and chemical characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi associated with the ethnomedicinal plant Bergenia ciliata

- Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency with SQI-Br and SQI-I sensitizers: A comparative analysis

- Nanostructured p-PbS/p-CuO sulfide/oxide bilayer heterojunction as a promising photoelectrode for hydrogen gas generation

Articles in the same Issue

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening