Abstract

The Mu Us Desert in China is significantly affected by seasonal freeze–thaw processes. In order to evaluate the adaptation potential of reconstituted soil with different proportions of feldspathic sandstone and sand to extreme environment, the laboratory simulation freeze-thaw experiments was conducted to study the characteristics of soil C and N under freeze–thaw conditions. The results showed that the content of soil organic matter reached the peak after two cycles of freezing and thawing in T1, T2 and T3, compared to before freeze–thaw cycle, the soil organic matter content increased by 70, 55 and 59%. After ten cycles of freezing and thawing, the content of soil organic matter increased significantly in T2 and T3. After one cycle of freezing and thawing, soil nitrogen content reached the peak. After ten cycles of freeze–thaw cycle, compared to before freeze–thaw cycle, the contents of ammonium nitrogen increased by 10, 49 and 11%, and the contents of nitrate nitrogen increased by 14, 39 and 34% in T1, T2 and T3. In conclusion, short-term freeze–thaw cycles in the Mu Us Desert significantly increased the accumulation of soil carbon and nitrogen reconstructed by different ratios of feldspathic sandstone and sand, and T2 and T3 treatments had better retention performance on soil organic matter and nitrogen, which has a good adaptability to the extreme environment.

1 Introduction

Soil freezing and thawing is an important factor affecting the release and availability of soil nutrients [1,2]. However, soil organic matter and nitrogen are important components of soils, and their content and dynamic balance not only directly affect soil quality and land productivity [3,4], but also have important implications for the carbon and nitrogen cycles in ecosystems [5,6]. At present, soil organic matter and nitrogen have become one of the core research types on global change problems [7]. Soil freezing and thawing is mainly by destroying soil aggregates and organic matter structure, killing certain microorganisms in the soil, increasing the death and decomposition of fine plant roots, and accelerating the fragmentation of plant residues to release nutrients needed for plant growth [8,9]. At the same time, the thawing process following soil freezing often leads to enhanced microbial respiration [10] and increased concentrations of C, N and P nutrients in the soil [11], potentially affecting ecosystem nutrient cycling processes and ecosystem productivity [12]. After freezing–thawing cycle, soil coarse mineral particles are fragmented mechanically and fine particles are aggregated, and soil particle size tends to be homogeneous [13]. Therefore, the seasonal freezing–thawing alternating action can pulverize large blocks of feldspathic sandstone, which is more conducive to the full mixing of feldspathic sandstone and sand to form reconstituted soil in the Mu Us Desert [14].

The Mu Us Desert annually lasts a freeze period of 4–5 months, and the temperature goes below 0°C in November and gradually returns to above 0°C in March of the following year, with the soil in a frozen and thawed state in the late autumn and early spring seasons. Soils are affected by the temperate cool climate and the seasonal freeze layer, and the resulting freeze–thaw alternation has a significant impact on regional soils [15]. In the Mu Us Desert, feldspathic sandstone and sand are two relatively independent natural substances, and they are the main factors causing soil erosion and land desertification. Han et al. [16,17] found that the rich clay minerals in feldspathic sandstone can improve the erosion resistance and water and fertility retention of sandy soils, and after reconstituting feldspathic sandstone and sandy soils into “soil” according to scientific ratios, they found that the optimal mixing ratio of feldspathic sandstone and sand was 1:1–1:5, and its water and fertility retention performance was the strongest [18,19]. It has been used in large-scale demonstrations. The effects of freeze–thaw on soil structure and mechanical characteristics have been studied extensively at home and abroad [8,11,13,20,21]; however, studies on the effects of soil freeze–thaw processes on organic carbon and nitrogen mineralization in feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstructed soils in the Mu Us Desert, China, have not been reported. In this study, we investigated the effects of soil freeze–thaw processes on the carbon and nitrogen contents of different proportions of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soils in the Mu Us Desert after land remediation, so as to determine the adaptation potential of different proportions of reconstituted soils to extreme environments and to help understand the soil nitrogen cycling processes in the Mu Us Desert. This study has important practical significance for guiding vegetation management and soil fertility improvement in early spring in seasonal frozen soil region.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Overview of the study area

The study area is located at the southern edge of the Mu Us Desert, in the middle reaches of the Wuding River (109°28′58″-109°30′10″E, 38°27′53″-38°28′23″N), at an altitude of 1,206–1,215 m. The climate is mainly temperate arid and semi-arid types, with annual rainfall ranging from 200 to 600, sunshine for 2,500–3,000 h throughout the year, with a sunshine percentage as high as 70–80%. The annual average temperature in the sandy area is 6.0–8.5°C, the average temperature in January is −9.5 to 12°C, the average temperature in July is 22–24°C, and the annual average frost-free period is 120–300 days. Feldspathic sandstone and sand in the Mu Us Desert are distributed interspersedly, and the soil type is mainly aeolian soils, with a total nitrogen content of 0.075%, a total phosphorus content of 0.63 g kg−1, a total potassium content of 26.51 g kg−1 and an organic matter content of 0.03%.

2.2 Research methodology

The experimental soil samples were collected from the field scientific observation test plots of feldspathic sandstone amended wind-sand soil in Xiao Jihan Township, Yuyang District, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province, with each plot being 12 m long × 5 m wide. The original sandy soil was covered with a layer of 30-cm-thick reconstituted soil in each test plot according to the needs of the study, with volumetric ratios of 1:1 (T1), 1:2 (T2) and 1:5 (T3) of feldspathic sandstone to sandy soil, respectively. Below 30 cm was the original local aeolian soils 0:1 (T0). Soils were collected from the 0 to 30 cm surface layer and immediately placed in a 0–4°C freezer and taken back to the laboratory for freeze–thaw incubation tests. Local irrigation water was also collected, and the test samples were moisture corrected. The main physicochemical properties of the reconstituted soil and the original aeolian soil for the different treatments are detailed in Table 1.

Main physical and chemical properties of soils reconstructed by feldspathic sandstone and sand

| Feldspathic sandstone (F): Sand (S) | Soil depth (cm) | Soil mechanical composition (%) | Texture | Bulk density (g cm−3) | Total nitrogen (g kg−1) | Organic matter (g kg−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Silt | Clay | ||||||

| T1 | 0–30 | 53.82 | 38.12 | 8.06 | Loam | 1.37 | 0.44 | 2.26 |

| T2 | 0–30 | 68.86 | 26.01 | 5.13 | Sandy loam | 1.52 | 0.54 | 2.61 |

| T3 | 0–30 | 79.03 | 17.35 | 3.62 | Sandy loam | 1.56 | 0.65 | 2.97 |

| T0 | 0–30 | 95.00 | 4.15 | 0.85 | Sandy soil | 1.61 | 0.75 | 3.32 |

The collected soil samples treated with T0, T1, T2 and T3 were removed from grassroots and other debris, air-dried, and then passed through a 2 mm sieve for freeze–thaw culture experiments. The five samples of 500 g each were prepared for each treatment and placed in 20 round aluminium boxes. In order to keep the freeze–thaw conditions in the chamber closer to the natural state, i.e. temperature fluctuations start as close as possible to the top layer of soil, the aluminium boxes were covered with asbestos mesh to achieve better insulation. The soil was completely frozen at −15 to −5°C for a 24-h period and then placed at 15°C for 24 h, and this constituted one freeze–thaw cycle. Five samples from each treatment, replicated three times, were used to determine the organic matter, nitrate and ammonium nitrogen content of the soil of before freeze–thaw, one cycle, two cycles, five cycles and ten cycles, respectively. The T1 freeze–thaw-treated soil samples were recorded as M0, M1, M2, M5 and M10; the T2 soil samples were recorded as A0, A1, A2, A5 and A10; the T3 soil samples were recorded as S0, S1, S2, S5 and S10; and the T0 soil samples were recorded as H0, H1, H2, H5 and H10. M0, A0, S0 and H0 were control samples and were not subjected to freeze–thaw treatment. In order to simulate the actual soil freeze–thaw conditions, the moisture content of the soil samples needed to be moisture corrected by adjusting the soil moisture content to 60% of the maximum field holding capacity, and then, during the experiment, the lost water was continuously replenished by weighing method to maintain the corresponding moisture condition of the test soil samples. Soil samples were extracted with 2 mol L−1 KCl solution (5:1 water to soil ratio) before the test and the nitrate, and ammonium nitrogen content was determined using a fully automated intermittent chemical analyser (Cleverchem 200, Germany), while the soil moisture was measured by gravimetric method. Soil organic matter content was determined using the potassium dichromate volumetric method – external heating method [22].

2.3 Data processing

SPSS 13.0 statistical analysis software was used for T-test to analyse the differences of soil organic matter, ammonia nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen in T1, T2 and T3 treatments after different freeze–thaw cycles. There were significant differences (P < 0.05) and no significant differences (P > 0.05). The experimental data were collated and plotted using Excel 2010 and SigmaPlot 12, respectively.

3 Results

3.1 Effects of freezing–thawing cycles on reconstructed soil organic matter content

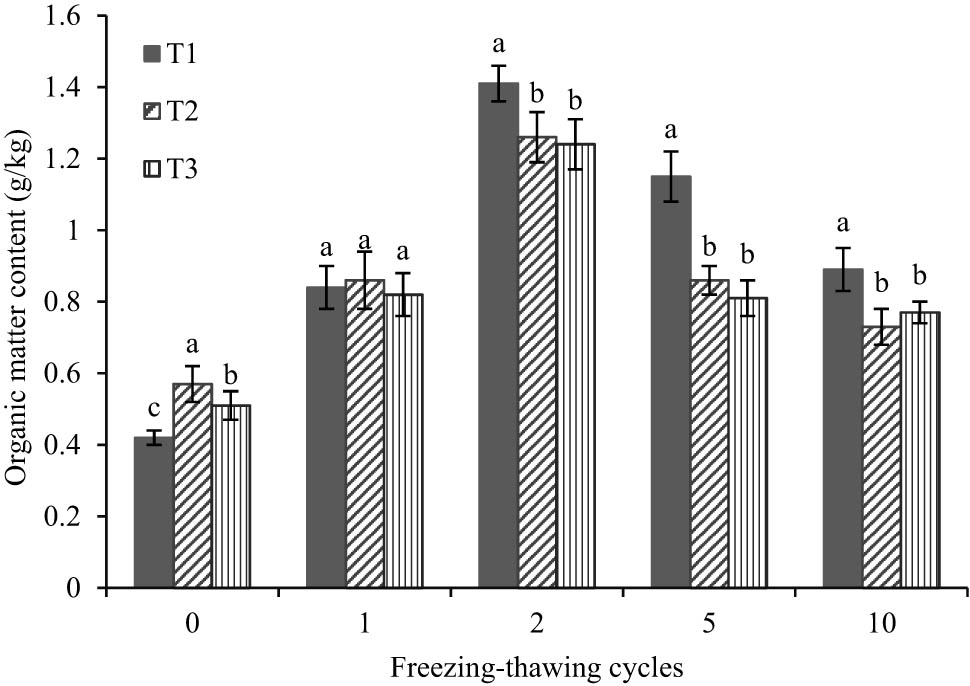

The freeze–thaw cycle had a significant effect (P < 0.005) on the organic matter content of the feldspathic sandstone and sand reconstituted soils (Figure 1). The organic matter content of the three reconstituted soils before freeze–thaw was T2 > T3 > T1, and as the freeze–thaw cycle increased, the organic matter content of the soils in the three treatments showed an overall trend of increasing and then decreasing. The organic matter content of the soils increased significantly at the beginning of the freeze–thaw cycle, and the organic matter content of the soils of the three treatments reached a peak at the second cycle of the freeze–thaw cycle, in the order of T1 > T2 > T3. Before freeze–thaw cycle, the organic matter content of the soils of the T1, T2 and T3 reconstructions increased by 70, 55 and 59%, respectively. After two cycles, the soil organic matter content began to decrease; after ten cycles, the organic matter content of T1, T2 and T3 reconstituted soils was 0.89, 0.74 and 0.77%, respectively, with an overall levelling off, but the organic matter content still increased overall compared to before freeze–thaw cycle, with no significant difference between T2 and T3 (P > 0.005).

Changes of organic matter content in reconstructed soils with different freezing–thawing cycles. Letters above the bars indicate the significance of the differences (at 0.05 level) between treatments; the small bar shows standard deviation. Bars in different treatments but with the same letters are not significantly different at P > 0.05.

3.2 Effects of freezing–thawing cycles on nitrate nitrogen content in reconstructed soils

As can be seen from Figure 2, with the increase in the freeze–thaw cycle, the nitrate–nitrogen content of the soils of the three treatments showed a trend of first increasing, then decreasing and then steadily increasing. Before freeze–thaw and at the beginning of the freeze–thaw cycle, the nitrate–nitrogen content of the soils in all three treatments was T2 > T1 > T3. The nitrate–nitrogen content of the reconstituted soil increased significantly with increasing freeze–thaw cycles at the beginning of the freeze–thaw cycle, with the most pronounced increase reaching a peak at one cycle of freeze–thaw. Compared to the pre-freeze–thaw treatment, soil nitrate-N content increased by 1.30, 1.52 and 1.49 times in the T1, T2 and T3 treatments, respectively. After two cycles of freeze–thaw, the nitrate–nitrogen content of the soils in the three treatments decreased significantly and reached a minimum value. After five cycles of freeze–thaw, the overall trend of the samples with all treatments increased. Compared to the period before freeze–thaw, after ten cycles of freeze–thaw, the nitrate–nitrogen content of the soils in the T1, T2 and T3 treatments increased by 14, 39 and 34%, respectively, with the content showing: T2 > T3 > T1, with the rate of increase in the nitrate–nitrogen content of the soils in the T2 and T3 treatments being more significant.

Changes of nitrate nitrogen content in reconstructed soil with different freezing–thawing cycles.

3.3 Effects of freezing–thawing cycles on the ammonium nitrogen content in reconstructed soils

With the increase of freeze–thaw cycle, the distribution of ammonium nitrogen content of reconstituted soils in the three treatments changed, and the ammonium nitrogen content of reconstituted soils in different proportions showed a trend of first increasing, then decreasing and then increasing steadily. During freeze–thaw cycles 0–1, the soil ammonium nitrogen content of the three treatments was T3 > T2 > T1. During freeze–thaw cycle 1, the soil ammonium nitrogen content of the T1, T2 and T3 treatments increased significantly and reached the peak, which was 1.41, 1.64 and 1.44 times higher than that before the freeze–thaw treatment, respectively. Then, the ammonium nitrogen content of the soils in the three treatments then began to decline, reaching a minimum value after two cycles of freeze–thaw, after which the content showed a steady increase. Compared with freeze–thaw cycle 0, after ten cycles of freeze–thaw, soil ammonium nitrogen content increased by 10, 49 and 11% in the T1, T2 and T3 treatments, respectively, with T2 > T3 > T1, with T2 and T3 treatments having significantly higher soil ammonium nitrogen content than T1 (Figure 3).

Changes of ammonium nitrogen content in reconstituted soil with different freezing–thawing cycles.

4 Discussion

4.1 Reconstructing soil organic content changes

Freeze–thaw alternation can affect soil organic matter content, but the results vary depending on the soil type and the research method [23,24]. In this research, it was found that with the increase in the freeze–thaw cycle, the soil organic matter content of T1, T2 and T3 treatments showed a trend of increasing and then decreasing, and the rate of change of organic matter content in different treatments was different. This is similar to the findings of Hao et al. [25], who found that soil organic matter content increased after 1–3 cycles of freeze–thawing and began to decrease after 6 cycles. Therefore, the short-term effect of freeze–thaw cycling on soil organic matter content is obvious, with significant effects of freeze–thaw frequency. This is due to the fact that changes in soil organic matter under the freeze–thaw cycle mainly originate from changes in soil microorganisms [25,26]. The increase of organic matter content in the early stage of freeze–thaw cycle is due to the death of some microorganisms in the soil due to the severe freezing temperature. These killed microorganisms release some small molecular organic matter in the decomposition process, which increases the content of organic matter in the soil. On the other hand, the stability of soil aggregates is an important factor to determine the content of soil organic matter. Freezing–thawing breaks the stability of soil aggregates and causes the organic matter wrapped and adsorbed by the soil to disaggregate ahead of time, and soil organic matter content increased [26]. After several freeze–thaw cycles, the content of organic matter in the reconstructed soil gradually decreased. On the one hand, the absolute death amount of microorganisms gradually decreased because they had adapted to the temperature change of the outside environment; accordingly, the amount of organic matter released by microorganisms is also decreasing. Second, with the development of freeze–thaw cycle experiment, the microorganisms living in the soil gradually decompose and utilize the original organic matter, resulting in the reduction of the content of organic matter in the soil [27].

4.2 Reconstructing soil nitrogen changes

There is no universal conclusion as to whether nitrate and ammonium nitrogen content in soils increases or decreases under the freeze–thaw cycle, depending on the parent soil forming material, the study area and the mode of analysis. In this study, a significant decrease in nitrate and ammonium nitrogen was found in the soils of the T1, T2 and T3 treatments after two cycles of freeze–thaw. There are mainly several reasons: (1) The nitrate and ammonium nitrogen in the soil was used by the small amount of plant roots remaining during the indoor simulated freeze–thaw test. (2) Nitrogen is sequestered by surviving or nascent microorganisms in the soil, especially under the effect of mild freeze–thaw alternations, to which the microorganisms are highly resistant. (3) Loss of inorganic nitrogen from reconstituted soil infiltrates during indoor simulations. (4) Loss of gaseous nitrogen in reconstituted soils may also lead to a decrease in the ammonium nitrogen content of the soil.

Starting from cycle 5 of the freeze–thaw cycle, the nitrate and ammonium nitrogen contents in the soils of the T1, T2 and T3 treatments all began to show a steady increase, indicating that the effect of multiple freeze–thaw cycles can increase the nitrate and ammonium nitrogen contents in the soil. This is due to the fact that some microorganisms are adapted to survive at low temperatures, and when the frozen soil thaws at elevated temperatures, the residual microorganisms use the sufficient substrate provided by the dead microorganisms, which stimulates microbial activity and facilitates the process of reconstituting the mineralization of soil organic nitrogen, thus promoting the increase of soil nitrate and ammonium nitrogen contents during the freeze–thaw cycle [28,29]. Freppaz et al. [30] and Chen et al. [31] showed that the freeze–thaw cycling process may lead to the release of

5 Conclusions

The diurnal freeze–thaw cycle in the late autumn and early spring seasons of the Mu Us Desert enhances soil microbial activity, and the mineralization of carbon and nitrogen in the soil is still ongoing. It was found that the short-term freeze–thaw cycle could promote the increase of soil organic matter, nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen, and the adaptation potential of T2 and T3 treatments to extreme environment was higher than that of T1 treatments. After freezing and thawing cycles, the soil organic matter content, nitrate nitrogen content and ammonium nitrogen content increased significantly in T2 and T3 treatments, and the soil nutrient retention performance is better. The freeze–thaw cycle increases the mass fraction of organic matter and inorganic nitrogen in the soil, which is conducive to providing a large amount of nutrients for the growth of plants in early spring, and plays an important role in improving the fertility of the soil. This study has important scientific value for guiding the improvement of soil fertility and sustainable agricultural development in frozen soil area.

-

Funding information: This study was financially supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (2022NY-082), Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program (2021JZ-57), funded by Technology Innovation Center for Land Engineering and Human Settlements, Shaanxi Land Engineering Construction Group Co., Ltd and Xi’an Jiaotong University (2021WHZ0087) and Shaanxi Provincial Land Engineering Construction Group internal research project (DJNY2022-17).

-

Author contributions: H.Z. – conceptualization; X.W. – methodology, C.Y. and Z.G. – software; Y.W. – Formal Analysis; Y.W. – investigation; H.Z. and C.Y. – resources; X.W. – data curation; H.Z. – writing original draft preparation; H.Z. – writing review and editing; Z.G. – project administration; H.Z. – funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Shen JJ, Wang Q, Chen YT, Han Y, Zhang XD, Liu YW. Evolution process of the microstructure of saline soil with different compaction degrees during freeze-thaw cycles. Eng Geol. 2022;304:106699.10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106699Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Fan JH, Cao YZ, Yan Y, Lu XY, Wang XD. Freezing-thawing cycles effect on the water soluble organic carbon, nitrogen and microbial biomass of alpine grassland soil in Northern Tibet. African J Microbiol Res. 2012;6(3):562–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Han LF, Sun K, Jin J, Xing BS. Some concepts of soil organic carbon characteristics and mineral interaction from a review of literature. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;94:107–21.10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.023Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Lehmann J, Hansel CM, Kaiser C, Kleber M, Maher K, Manzoni S, et al. Persistence of soil organic carbon caused by functional complexity. Nat Geosci. 2020;13(8):529–34.10.1038/s41561-020-0612-3Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Huang FY, Liu ZH, Zhang P, Jia ZK. Hydrothermal effects on maize productivity with different planting patterns in a rainfed farmland area. Soil Till Res. 2021;205:104794.10.1016/j.still.2020.104794Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Li YL, Pan XZ, Wang CK, Liu Y, Zhao QG. Monitoring changes of soil organic matter and total nitrogen in cultivated land in Guangxi by remote sensing. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2014;34(18):5283–91.10.5846/stxb201405100953Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Guo Z, Wang Y, Wan Z, Zuo Y, He L, Li D, et al. Soil dissolved organic carbon in terrestrial ecosystems: Global budget, spatial distribution and controls. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2020;29(11/12):2159–75.10.1111/geb.13186Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Oztas T, Fayetorbay F. Effect of freezing and thawing processes on soil aggregate stability. Cetena. 2003;52(1):1–8.10.1016/S0341-8162(02)00177-7Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Jin WP, Fan HM, Liu B, Jiang YZ, Jiang Y, Ma RM. Effect of Freeze-thaw alternation on aggregate stability of black soil. Chinese J Appl Ecol. 2019;30(12):4195–201.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Wang JY, Song CC, Wang XW, Wang LL. Progress in the study of effect of freeze-thaw processes on the organic carbon pool and microorganisms in soils. J Glaciol Geocryol. 2011;33(2):442–52.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Edwards LM. The effect of alternate freezing and thawing on aggregate stability and aggregate size distribution of some Prince Edward island soils. Eur J Soil Sci. 2010;42:193–204.10.1111/j.1365-2389.1991.tb00401.xSuche in Google Scholar

[12] Chang ZQ, Ma YL, Liu W, Feng Q, Su YH, Xi HY, et al. Effect of soil freezing and thawing on the carbon and nitrogen in forest soil in the Qilian mountains. J Glaciol Geocryol. 2014;36(1):200–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang Z, Ma W, Feng WJ, Xiao DH, Hou X. Reconstruction of soil particle composition during freeze-thaw cycling: A review. Pedosphere. 2016;26(2):167–79.10.1016/S1002-0160(15)60033-9Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Ni HB, Zhang LP, Zhang DR, Wu XY, Fu XT. Weathering of pisha-sandstones in the wind-water erosion crisscross region on the Loess Plateau. Mt Sci. 2008;5:340–9.10.1007/s11629-008-0218-5Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Sun BY, Li ZB, Xiao JB, Zhang LT, Ma B, Li JM, et al. Research progress on the effects of freeze-thaw on soil physical and chemical properties and wind and water erosion. Chinese J Appl Ecol. 2019;30(1):337–47.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Han JC, Xie JC, Zhang Y. Potential role of feldspathic sandstone as a natural water retaining agent in Mu Us Sandy land, northwest China. Chinese Geogr Sci. 2012;22:550–5.10.1007/s11769-012-0562-9Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Han JC, Liu YS, Zhang Y. Sand stabilization effect of feldspathic sandstone during the fallow period in Mu Us Sandy land. J Geogr Sci. 2015;4:428–36.10.1007/s11442-015-1178-7Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Sun ZH, Han JC. Effect of soft rock amendment on soil hydraulic parameters and crop performance in Mu Us Sandy Land. China Field Crops Res. 2018;222:85–93.10.1016/j.fcr.2018.03.016Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Wang HY, Han JC, Tong W, Cheng J, Zhang HO. Analysis of water and nitrogen use efficiency for maize (Zea mays L.) grown on soft rock and sand compound soil. J Sci Food Agr. 2017;97:2553–60.10.1002/jsfa.8075Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Sahin U, Angin I, Kiziloglu FM. Effect of freezing and thawing processes on some physical properties of saline-sodic soils mixed with sewage sludge or fly ash. Soil Till Res. 2008;99:254–60.10.1016/j.still.2008.03.001Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Cai YJ, Wang XD, Ding WX, Yan Y, Lu XY, Du ZY. Effects of freeze-thaw on soil nitrogen transformation and N2O emission: A review. Acta Pedologica Sinica. 2013;50(5):1032–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Yuan ZR, Ren L, Chen JG. Relationship between soil organic matter and total nitrogen in different types of grassland on Qilian mountain. Grassland and Turf. 2016;36(3):12–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Wei YH, Zhao X, Zhai YL, Zhang EP, Chen F, Zhang HL. Effects of tillages on soil organic carbon sequestration in north China plain. Trans CSAE. 2013;29(17):87–95.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Gao M, Li YX, Zhang XL, Zhang FS, Liu B, Gao SY, et al. Influence of freeze-thaw process on soil physical, chemical and biological properties: A review. J Agro-Environ Sci. 2016;35(12):2269–74.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Hao RJ, Li ZP, Che YP. Effects of freezing and thawing cycles on the contents of WSOC and the organic carbon mineralization in Paddy soil. Chinese J Soil Sci. 2007;38(6):1052–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Wen J, Wang YB, Gao ZY, Liu GH. Soil hydrological characteristics of the degrading meadow in permafrost regions in the Beiluhe river basin. J Glaciol Geocryol. 2013;35(4):929–37.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Zhang B, Chen Q, Wen JH, Ding XL, Agathokleous E. Straw addition decreased the resistance of bacterial community composition to freeze-thaw disturbances in a clay loam soil due to changes in physiological and functional traits. Geoderma. 2022;424:116007.10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116007Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Du ZY, Cai YJ, Wang XD, Yan Y, Lu XY, Liu SZ. Research progress on the effects of soil freeze-thaw on plant physiology and ecology. Chinese J Eco-Agr. 2014;22(1):1–9.10.3724/SP.J.1011.2014.30941Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Wang F, Zhu Y, Chen S, Zhang KQ, Bai HL, Yao H. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on available nitrogen and phosphorus, enzymatic activities of typical cultivated soil. Trans CSAE. 2013;29(24):118–23.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Freppaz M, Williams BL, Edwards AC, Scalenghec R, Zaninia E. Simulating soil freezing and thawing cycles typical of winter alpine conditions: Implications for N and P availability. Appl Soil Ecol. 2006;35(l):247–55.10.1016/j.apsoil.2006.03.012Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Lai F, Zhang Z, Chen S, Sun H. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on soil nitrogen loss and availability. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2016;36(4):1083–94.10.5846/stxb201406061171Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Wang Y, Liu JS, Wang QY. The effects of freeze-thaw processes on soil aggregates and organic carbon. Ecol and Environ Sci. 2013;22(7):1269–74.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening

- Prefatory in silico studies and in vitro insecticidal effect of Nigella sativa (L.) essential oil and its active compound (carvacrol) against the Callosobruchus maculatus adults (Fab), a major pest of chickpea

- Polymerized methyl imidazole silver bromide (CH3C6H5AgBr)6: Synthesis, crystal structures, and catalytic activity

- Using calcined waste fish bones as a green solid catalyst for biodiesel production from date seed oil

- Influence of the addition of WO3 on TeO2–Na2O glass systems in view of the feature of mechanical, optical, and photon attenuation

- Naringin ameliorates 5-fluorouracil elicited neurotoxicity by curtailing oxidative stress and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 pathway

- GC-MS profile of extracts of an endophytic fungus Alternaria and evaluation of its anticancer and antibacterial potentialities

- Green synthesis, chemical characterization, and antioxidant and anti-colorectal cancer effects of vanadium nanoparticles

- Determination of caffeine content in coffee drinks prepared in some coffee shops in the local market in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

- A new 3D supramolecular Cu(ii) framework: Crystal structure and photocatalytic characteristics

- Bordeaux mixture accelerates ripening, delays senescence, and promotes metabolite accumulation in jujube fruit

- Important application value of injectable hydrogels loaded with omeprazole Schiff base complex in the treatment of pancreatitis

- Color tunable benzothiadiazole-based small molecules for lightening applications

- Investigation of structural, dielectric, impedance, and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-modified barium titanate composites for biomedical applications

- Metal gel particles loaded with epidermal cell growth factor promote skin wound repair mechanism by regulating miRNA

- In vitro exploration of Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) mushroom fruiting bodies: Potential antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agent

- Alteration in the molecular structure of the adenine base exposed to gamma irradiation: An ESR study

- Comprehensive study of optical, thermal, and gamma-ray shielding properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses

- Lewis acids as co-catalysts in Pd-based catalyzed systems of the octene-1 hydroethoxycarbonylation reaction

- Synthesis, Hirshfeld surface analysis, thermal, and selective α-glucosidase inhibitory studies of Schiff base transition metal complexes

- Protective properties of AgNPs green-synthesized by Abelmoschus esculentus on retinal damage on the virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in diabetic rat

- Effects of green decorated AgNPs on lignin-modified magnetic nanoparticles mediated by Cydonia on cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by green mediated silver nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica bark aqueous extract

- Preparation of newly developed porcelain ceramics containing WO3 nanoparticles for radiation shielding applications

- Utilization of computational methods for the identification of new natural inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase in inflammation therapy

- Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors

- Clay-based bricks’ rich illite mineral for gamma-ray shielding applications: An experimental evaluation of the effect of pressure rates on gamma-ray attenuation parameters

- Stability kinetics of orevactaene pigments produced by Epicoccum nigrum in solid-state fermentation

- Treatment of denture stomatitis using iron nanoparticles green-synthesized by Silybum marianum extract

- Characterization and antioxidant potential of white mustard (Brassica hirta) leaf extract and stabilization of sunflower oil

- Characteristics of Langmuir monomolecular monolayers formed by the novel oil blends

- Strategies for optimizing the single GdSrFeO4 phase synthesis

- Oleic acid and linoleic acid nanosomes boost immunity and provoke cell death via the upregulation of beta-defensin-4 at genetic and epigenetic levels

- Unraveling the therapeutic potential of Bombax ceiba roots: A comprehensive study of chemical composition, heavy metal content, antibacterial activity, and in silico analysis

- Green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extract and investigation of its anti-human colorectal cancer application

- The adsorption of naproxen on adsorbents obtained from pepper stalk extract by green synthesis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by silver nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan polymers mediated by Pistacia atlantica extract under ultrasound condition

- In vitro protective and anti-inflammatory effects of Capparis spinosa and its flavonoids profile

- Wear and corrosion behavior of TiC and WC coatings deposited on high-speed steels by electro-spark deposition

- Therapeutic effects of green-formulated gold nanoparticles by Origanum majorana on spinal cord injury in rats

- Melanin antibacterial activity of two new strains, SN1 and SN2, of Exophiala phaeomuriformis against five human pathogens

- Evaluation of the analgesic and anesthetic properties of silver nanoparticles supported over biodegradable acacia gum-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- Review Articles

- Role and mechanism of fruit waste polyphenols in diabetes management

- A comprehensive review of non-alkaloidal metabolites from the subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae)

- Discovery of the chemical constituents, structural characteristics, and pharmacological functions of Chinese caterpillar fungus

- Eco-friendly green approach of nickel oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications

- Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration

- Rapid Communication

- Determination of the contents of bioactive compounds in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Comparison of commercial and wild samples

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: The protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α”

- Topical Issue on Phytochemicals, biological and toxicological analysis of aromatic medicinal plants

- Anti-plasmodial potential of selected medicinal plants and a compound Atropine isolated from Eucalyptus obliqua

- Anthocyanin extract from black rice attenuates chronic inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mouse model by modulating the gut microbiota

- Evaluation of antibiofilm and cytotoxicity effect of Rumex vesicarius methanol extract

- Chemical compositions of Litsea umbellata and inhibition activities

- Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles using Rhynchosia capitata leaf extract and their biological activities

- GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activities of some plants belonging to the genus Euphorbia on selected bacterial isolates

- The abrogative effect of propolis on acrylamide-induced toxicity in male albino rats: Histological study

- A phytoconstituent 6-aminoflavone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress mediated synapse and memory dysfunction via p-Akt/NF-kB pathway in albino mice

- Anti-diabetic potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder: Phytochemistry (GC-MS analysis), α-amylase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, in vivo hypoglycemic, and biochemical analysis

- Assessment of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the Cassia angustifolia aqueous extract against SW480 colon cancer

- Biochemical analysis, antioxidant, and antibacterial efficacy of the bee propolis extract (Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera) against Staphylococcus aureus-induced infection in BALB/c mice: In vitro and in vivo study

- Assessment of essential elements and heavy metals in Saudi Arabian rice samples underwent various processing methods

- Two new compounds from leaves of Capparis dongvanensis (Sy, B. H. Quang & D. V. Hai) and inhibition activities

- Hydroxyquinoline sulfanilamide ameliorates STZ-induced hyperglycemia-mediated amyleoid beta burden and memory impairment in adult mice

- An automated reading of semi-quantitative hemagglutination results in microplates: Micro-assay for plant lectins

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assessment of essential and toxic trace elements in traditional spices consumed by the population of the Middle Eastern region in their recipes

- Phytochemical analysis and anticancer activity of the Pithecellobium dulce seed extract in colorectal cancer cells

- Impact of climatic disturbances on the chemical compositions and metabolites of Salvia officinalis

- Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils of Urginea maritima and Allium sativum

- Phytochemical analysis and antifungal efficiency of Origanum majorana extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi causing tomato damping-off diseases

- Special Issue on 4th IC3PE

- Graphene quantum dots: A comprehensive overview

- Studies on the intercalation of calcium–aluminium layered double hydroxide-MCPA and its controlled release mechanism as a potential green herbicide

- Synergetic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis by zinc ferrite-anchored graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet for the removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light irradiation

- Exploring anticancer activity of the Indonesian guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) fraction on various human cancer cell lines in an in vitro cell-based approach

- The comparison of gold extraction methods from the rock using thiourea and thiosulfate

- Special Issue on Marine environmental sciences and significance of the multidisciplinary approaches

- Sorption of alkylphenols and estrogens on microplastics in marine conditions

- Cytotoxic ketosteroids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp.

- Antibacterial and biofilm prevention metabolites from Acanthophora spicifera

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part II

- Green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial activities of cobalt nanoparticles produced by marine fungal species Periconia prolifica

- Combustion-mediated sol–gel preparation of cobalt-doped ZnO nanohybrids for the degradation of acid red and antibacterial performance

- Perinatal supplementation with selenium nanoparticles modified with ascorbic acid improves hepatotoxicity in rat gestational diabetes

- Evaluation and chemical characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi associated with the ethnomedicinal plant Bergenia ciliata

- Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency with SQI-Br and SQI-I sensitizers: A comparative analysis

- Nanostructured p-PbS/p-CuO sulfide/oxide bilayer heterojunction as a promising photoelectrode for hydrogen gas generation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Regular Articles

- A network-based correlation research between element electronegativity and node importance

- Pomegranate attenuates kidney injury in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress

- Ab initio study of fundamental properties of XInO3 (X = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites

- Responses of feldspathic sandstone and sand-reconstituted soil C and N to freeze–thaw cycles

- Robust fractional control based on high gain observers design (RNFC) for a Spirulina maxima culture interfaced with an advanced oxidation process

- Study on arsenic speciation and redistribution mechanism in Lonicera japonica plants via synchrotron techniques

- Optimization of machining Nilo 36 superalloy parameters in turning operation

- Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries

- Characterization of effective constituents in Acanthopanax senticosus fruit for blood deficiency syndrome based on the chinmedomics strategy

- Comparative analysis of the metabolites in Pinellia ternata from two producing regions using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry

- The assessment of environmental parameter along the desalination plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Effects of harpin and carbendazim on antioxidant accumulation in young jujube leaves

- The effects of in ovo injected with sodium borate on hatching performance and small intestine morphology in broiler chicks

- Optimization of cutting forces and surface roughness via ANOVA and grey relational analysis in machining of In718

- Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical characterization, in vitro, in silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

- Translocation of tungsten(vi) oxide/gadolinium(iii) fluoride in tellurite glasses towards improvement of gamma-ray attenuation features in high-density glass shields

- Mechanical properties, elastic moduli, and gamma ray attenuation competencies of some TeO2–WO3–GdF3 glasses: Tailoring WO3–GdF3 substitution toward optimum behavioral state range

- Comparison between the CIDR or sponge with hormone injection to induce estrus synchronization for twining and sex preselection in Naimi sheep

- Exergetic performance analyses of three different cogeneration plants

- Psoralea corylifolia (babchi) seeds enhance proliferation of normal human cultured melanocytes: GC–MS profiling and biological investigation

- A novel electrochemical micro-titration method for quantitative evaluation of the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of caffeic acid

- Comparative study between supported bimetallic catalysts for nitrate remediation in water

- Persicaline, an alkaloid from Salvadora persica, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells

- Determination of nicotine content in locally produced smokeless tobacco (Shammah) samples from Jazan region of Saudi Arabia using a convenient HPLC-MS/MS method

- Changes in oxidative stress markers in pediatric burn injury over a 1-week period

- Integrated geophysical techniques applied for petroleum basins structural characterization in the central part of the Western Desert, Egypt

- The impact of chemical modifications on gamma-ray attenuation properties of some WO3-reinforced tellurite glasses

- Microwave and Cs+-assisted chemo selective reaction protocol for synthesizing 2-styryl quinoline biorelevant molecules

- Structural, physical, and radiation absorption properties of a significant nuclear power plant component: A comparison between REX-734 and 316L SS austenitic stainless steels

- Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum YKL-40 level: In vivo rat periodontitis model

- Investigating the impact of CO2 emissions on the COVID-19 pandemic by generalized linear mixed model approach with inverse Gaussian and gamma distributions

- Influence of WO3 content on gamma rays attenuation characteristics of phosphate glasses at low energy range

- Study on CO2 absorption performance of ternary DES formed based on DEA as promoting factor

- Performance analyses of detonation engine cogeneration cycles

- Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: In vitro and in silico studies

- Untargeted metabolomics revealing changes in aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco

- Effect of pumpkin enriched with calcium lactate on iron status in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Energy consumption, mechanical and metallographic properties of cryogenically treated tool steels

- Optimization of ultra-high pressure-assisted extraction of total phenols from Eucommia ulmoides leaves by response surface methodology

- Harpin enhances antioxidant nutrient accumulation and decreases enzymatic browning in stored soybean sprouts

- Physicochemical and biological properties of carvacrol

- Radix puerariae in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation

- Anti-Alzheimer, antioxidants, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase effects of Taverniera glabra mediated ZnO and Fe2O3 nanoparticles in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

- Experimental study on photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of ZnS/CdS-TiO2 nanotube array thin films

- Epoxy-reinforced heavy metal oxides for gamma ray shielding purposes

- Black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) fruits: As a medicinal plant rich in human health-promoting compounds

- Promising antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oils extracted from fruits of Juniperus thurifera: In vitro and in silico investigations

- Chloramine-T-induced oxidation of Rizatriptan Benzoate: An integral chemical and spectroscopic study of products, mechanisms and kinetics

- Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of chemically profiled essential oils extracted from Juniperus phoenicea (L.) by use of in vitro and in silico approaches

- Screening and characterization of fungal taxol-producing endophytic fungi for evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities

- Mineral composition, principal polyphenolic components, and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties of Cytisus villosus Pourr leaf extracts

- In vitro antiproliferative efficacy of Annona muricata seed and fruit extracts on several cancer cell lines

- An experimental study for chemical characterization of artificial anterior cruciate ligament with coated chitosan as biomaterial

- Prevalence of residual risks of the transfusion-transmitted infections in Riyadh hospitals: A two-year retrospective study

- Computational and experimental investigation of antibacterial and antifungal properties of Nicotiana tabacum extracts

- Reinforcement of cementitious mortars with hemp fibers and shives

- X-ray shielding properties of bismuth-borate glass doped with rare earth ions

- Green supported silver nanoparticles over modified reduced graphene oxide: Investigation of its antioxidant and anti-ovarian cancer effects

- Orthogonal synthesis of a versatile building block for dual functionalization of targeting vectors

- Thymbra spicata leaf extract driven biogenic synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its bio-application in the treatment of different types of leukemia

- The role of Ag2O incorporation in nuclear radiation shielding behaviors of the Li2O–Pb3O4–SiO2 glass system: A multi-step characterization study

- A stimuli-responsive in situ spray hydrogel co-loaded with naringenin and gentamicin for chronic wounds

- Assessment of the impact of γ-irradiation on the piperine content and microbial quality of black pepper

- Antioxidant, sensory, and functional properties of low-alcoholic IPA beer with Pinus sylvestris L. shoots addition fermented using unconventional yeast

- Screening and optimization of extracellular pectinase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis SH7

- Determination of polyphenols in Chinese jujube using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Synergistic effects of harpin and NaCl in determining soybean sprout quality under non-sterile conditions

- Field evaluation of different eco-friendly alternative control methods against Panonychus citri [Acari: Tetranychidae] spider mite and its predators in citrus orchards

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biologically synthesized zero valent iron nanoparticles

- NaCl regulates goldfish growth and survival at three food supply levels under hypoxia

- An exploration of the physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of PbO–MgO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses

- A novel statistical modeling of air pollution and the COVID-19 pandemic mortality data by Poisson, geometric, and negative binomial regression models with fixed and random effects

- Treatment activity of the injectable hydrogels loaded with dexamethasone In(iii) complex on glioma by inhibiting the VEGF signaling pathway

- An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters

- Panax ginseng leaf aqueous extract mediated green synthesis of AgNPs under ultrasound condition and investigation of its anti-lung adenocarcinoma effects

- Study of hydrolysis and production of instant ginger (Zingiber officinale) tea

- Novel green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Salvia rosmarinus extract for treatment of human lung cancer

- Evaluation of second trimester plasma lipoxin A4, VEGFR-1, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of ortho- and para-substituted Schiff bases derived from metformin hydrochloride: Validation by molecular docking and in silico ADME studies

- Antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiglaucoma, and anticholinergic effects of Tayfi grape (Vitis vinifera): A phytochemical screening by LC-MS/MS analysis

- Identification of genetic polymorphisms in the stearoyl CoA desaturase gene and its association with milk quality traits in Najdi sheep

- Cold-acclimation effect on cadmium absorption and biosynthesis of polyphenolics, and free proline and photosynthetic pigments in Spirogyra aequinoctialis

- Analysis of secondary metabolites in Xinjiang Morus nigra leaves using different extraction methods with UPLC-Q/TOF-MS/MS technology

- Nanoarchitectonics and performance evaluation of a Fe3O4-stabilized Pickering emulsion-type differential pressure plugging agent

- Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of Shengdong coal through Py-GC/MS

- Extraction, phytochemical characterization, and antifungal activity of Salvia rosmarinus extract

- Introducing a novel and natural antibiotic for the treatment of oral pathogens: Abelmoschus esculentus green-formulated silver nanoparticles

- Optimization of gallic acid-enriched ultrasonic-assisted extraction from mango peels

- Effect of gamma rays irradiation in the structure, optical, and electrical properties of samarium doped bismuth titanate ceramics

- Combinatory in silico investigation for potential inhibitors from Curcuma sahuynhensis Škorničk. & N.S. Lý volatile phytoconstituents against influenza A hemagglutinin, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, and Omicron-variant spike protein

- Physical, mechanical, and gamma ray shielding properties of the Bi2O3–BaO–B2O3–ZnO–As2O3–MgO–Na2O glass system

- Twofold interpenetrated 3D Cd(ii) complex: Crystal structure and luminescent property

- Study on the microstructure and soil quality variation of composite soil with soft rock and sand

- Ancient spring waters still emerging and accessible in the Roman Forum area: Chemical–physical and microbiological characterization

- Extraction and characterization of type I collagen from scales of Mexican Biajaiba fish

- Finding small molecular compounds to decrease trimethylamine oxide levels in atherosclerosis by virtual screening

- Prefatory in silico studies and in vitro insecticidal effect of Nigella sativa (L.) essential oil and its active compound (carvacrol) against the Callosobruchus maculatus adults (Fab), a major pest of chickpea

- Polymerized methyl imidazole silver bromide (CH3C6H5AgBr)6: Synthesis, crystal structures, and catalytic activity

- Using calcined waste fish bones as a green solid catalyst for biodiesel production from date seed oil

- Influence of the addition of WO3 on TeO2–Na2O glass systems in view of the feature of mechanical, optical, and photon attenuation

- Naringin ameliorates 5-fluorouracil elicited neurotoxicity by curtailing oxidative stress and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 pathway

- GC-MS profile of extracts of an endophytic fungus Alternaria and evaluation of its anticancer and antibacterial potentialities

- Green synthesis, chemical characterization, and antioxidant and anti-colorectal cancer effects of vanadium nanoparticles

- Determination of caffeine content in coffee drinks prepared in some coffee shops in the local market in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

- A new 3D supramolecular Cu(ii) framework: Crystal structure and photocatalytic characteristics

- Bordeaux mixture accelerates ripening, delays senescence, and promotes metabolite accumulation in jujube fruit

- Important application value of injectable hydrogels loaded with omeprazole Schiff base complex in the treatment of pancreatitis

- Color tunable benzothiadiazole-based small molecules for lightening applications

- Investigation of structural, dielectric, impedance, and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-modified barium titanate composites for biomedical applications

- Metal gel particles loaded with epidermal cell growth factor promote skin wound repair mechanism by regulating miRNA

- In vitro exploration of Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) mushroom fruiting bodies: Potential antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agent

- Alteration in the molecular structure of the adenine base exposed to gamma irradiation: An ESR study

- Comprehensive study of optical, thermal, and gamma-ray shielding properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses

- Lewis acids as co-catalysts in Pd-based catalyzed systems of the octene-1 hydroethoxycarbonylation reaction

- Synthesis, Hirshfeld surface analysis, thermal, and selective α-glucosidase inhibitory studies of Schiff base transition metal complexes

- Protective properties of AgNPs green-synthesized by Abelmoschus esculentus on retinal damage on the virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in diabetic rat

- Effects of green decorated AgNPs on lignin-modified magnetic nanoparticles mediated by Cydonia on cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by green mediated silver nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica bark aqueous extract

- Preparation of newly developed porcelain ceramics containing WO3 nanoparticles for radiation shielding applications

- Utilization of computational methods for the identification of new natural inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase in inflammation therapy

- Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors

- Clay-based bricks’ rich illite mineral for gamma-ray shielding applications: An experimental evaluation of the effect of pressure rates on gamma-ray attenuation parameters

- Stability kinetics of orevactaene pigments produced by Epicoccum nigrum in solid-state fermentation

- Treatment of denture stomatitis using iron nanoparticles green-synthesized by Silybum marianum extract

- Characterization and antioxidant potential of white mustard (Brassica hirta) leaf extract and stabilization of sunflower oil

- Characteristics of Langmuir monomolecular monolayers formed by the novel oil blends

- Strategies for optimizing the single GdSrFeO4 phase synthesis

- Oleic acid and linoleic acid nanosomes boost immunity and provoke cell death via the upregulation of beta-defensin-4 at genetic and epigenetic levels

- Unraveling the therapeutic potential of Bombax ceiba roots: A comprehensive study of chemical composition, heavy metal content, antibacterial activity, and in silico analysis

- Green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extract and investigation of its anti-human colorectal cancer application

- The adsorption of naproxen on adsorbents obtained from pepper stalk extract by green synthesis

- Treatment of gastric cancer by silver nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan polymers mediated by Pistacia atlantica extract under ultrasound condition

- In vitro protective and anti-inflammatory effects of Capparis spinosa and its flavonoids profile

- Wear and corrosion behavior of TiC and WC coatings deposited on high-speed steels by electro-spark deposition

- Therapeutic effects of green-formulated gold nanoparticles by Origanum majorana on spinal cord injury in rats

- Melanin antibacterial activity of two new strains, SN1 and SN2, of Exophiala phaeomuriformis against five human pathogens

- Evaluation of the analgesic and anesthetic properties of silver nanoparticles supported over biodegradable acacia gum-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- Review Articles

- Role and mechanism of fruit waste polyphenols in diabetes management

- A comprehensive review of non-alkaloidal metabolites from the subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae)

- Discovery of the chemical constituents, structural characteristics, and pharmacological functions of Chinese caterpillar fungus

- Eco-friendly green approach of nickel oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications

- Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration

- Rapid Communication

- Determination of the contents of bioactive compounds in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Comparison of commercial and wild samples

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: The protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α”

- Topical Issue on Phytochemicals, biological and toxicological analysis of aromatic medicinal plants

- Anti-plasmodial potential of selected medicinal plants and a compound Atropine isolated from Eucalyptus obliqua

- Anthocyanin extract from black rice attenuates chronic inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mouse model by modulating the gut microbiota

- Evaluation of antibiofilm and cytotoxicity effect of Rumex vesicarius methanol extract

- Chemical compositions of Litsea umbellata and inhibition activities

- Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles using Rhynchosia capitata leaf extract and their biological activities

- GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activities of some plants belonging to the genus Euphorbia on selected bacterial isolates

- The abrogative effect of propolis on acrylamide-induced toxicity in male albino rats: Histological study

- A phytoconstituent 6-aminoflavone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress mediated synapse and memory dysfunction via p-Akt/NF-kB pathway in albino mice

- Anti-diabetic potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder: Phytochemistry (GC-MS analysis), α-amylase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, in vivo hypoglycemic, and biochemical analysis

- Assessment of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the Cassia angustifolia aqueous extract against SW480 colon cancer

- Biochemical analysis, antioxidant, and antibacterial efficacy of the bee propolis extract (Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera) against Staphylococcus aureus-induced infection in BALB/c mice: In vitro and in vivo study

- Assessment of essential elements and heavy metals in Saudi Arabian rice samples underwent various processing methods

- Two new compounds from leaves of Capparis dongvanensis (Sy, B. H. Quang & D. V. Hai) and inhibition activities

- Hydroxyquinoline sulfanilamide ameliorates STZ-induced hyperglycemia-mediated amyleoid beta burden and memory impairment in adult mice

- An automated reading of semi-quantitative hemagglutination results in microplates: Micro-assay for plant lectins

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry assessment of essential and toxic trace elements in traditional spices consumed by the population of the Middle Eastern region in their recipes

- Phytochemical analysis and anticancer activity of the Pithecellobium dulce seed extract in colorectal cancer cells

- Impact of climatic disturbances on the chemical compositions and metabolites of Salvia officinalis

- Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils of Urginea maritima and Allium sativum

- Phytochemical analysis and antifungal efficiency of Origanum majorana extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi causing tomato damping-off diseases

- Special Issue on 4th IC3PE

- Graphene quantum dots: A comprehensive overview

- Studies on the intercalation of calcium–aluminium layered double hydroxide-MCPA and its controlled release mechanism as a potential green herbicide

- Synergetic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis by zinc ferrite-anchored graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet for the removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light irradiation

- Exploring anticancer activity of the Indonesian guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) fraction on various human cancer cell lines in an in vitro cell-based approach

- The comparison of gold extraction methods from the rock using thiourea and thiosulfate

- Special Issue on Marine environmental sciences and significance of the multidisciplinary approaches

- Sorption of alkylphenols and estrogens on microplastics in marine conditions

- Cytotoxic ketosteroids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp.

- Antibacterial and biofilm prevention metabolites from Acanthophora spicifera

- Characteristics, source, and health risk assessment of aerosol polyaromatic hydrocarbons in the rural and urban regions of western Saudi Arabia

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part II

- Green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial activities of cobalt nanoparticles produced by marine fungal species Periconia prolifica

- Combustion-mediated sol–gel preparation of cobalt-doped ZnO nanohybrids for the degradation of acid red and antibacterial performance

- Perinatal supplementation with selenium nanoparticles modified with ascorbic acid improves hepatotoxicity in rat gestational diabetes

- Evaluation and chemical characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi associated with the ethnomedicinal plant Bergenia ciliata

- Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency with SQI-Br and SQI-I sensitizers: A comparative analysis

- Nanostructured p-PbS/p-CuO sulfide/oxide bilayer heterojunction as a promising photoelectrode for hydrogen gas generation