Abstract

Extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) which is known as a clean technology was carried out to extract oil from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds. SC-CO2 extraction technique does not contaminate extracts. SC-CO2 is not a toxic and a flammable solvent. Phytosterols, natural and bioactive compounds, which is known to provide protection against various chronic diseases were examined in the seed oil by using gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Stigmasterol and β-sitosterol were detected in the melon seed oil. SC-CO2 extractions were performed in a range of 30-55°C, 150-240 bar, 7-15 g CO2/min, 0.4-1.7 mm (mean particle size of the seeds) and 1-4 h. The optimal quantities of extracted oil, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol were 36.8 g/100 g seed, 304 mg/ kg seed and 121 mg/ kg seed, respectively, at 33°C, 200 bar, 11 g CO2/min, 0.4 mm and 3 h.

1 Introduction

The interest in supercritical fluid extraction which has been applied to food and natural products to obtain nutritionally beneficial compounds such as phytosterols (plant sterols) has recently increased. Phytosterols, a triterpenes group, are natural and bioactive compounds found in all plant cell membranes [1]. They have similar structural and biological functions to cholesterol [2].

Different structures in their side chain, even though minor, make phytosterols and cholesterol differ from each other functionally and metabolically [3]. The structural similarity of phytosterols to cholesterol allows to reduce the absorption of cholesterol from the gut [4]. It is stated that they provide protection against various chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and liver diseases, diabetes, obesity and cancer [2,5]. There are more than 200 phytosterol species naturally found in the plant kingdom and many are found in edible foodstuffs [5]. Primary sources are vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds [6]. β-sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol are the most common phytosterols in the human diet [2]. In this study, oil was extracted from Kırkağaç melon seeds by using supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2). β-sitosterol, stigmasterol and campesterol, known as principal phytosterols, were investigated in the seed oil. According to Turkish Statistical Institute, melon production in Turkey in 2017 was over 1.8 million tonnes (http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist). Kırkağaç melon is the most important melon cultivated in Turkey.

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) offers several advantages especially for biotechnology. Mass transfer limitations are reduced due to high diffusivity of supercritical fluids, particularly for extraction from porous matrices such as plant material. Their low surface tension provides them to penetrate into smaller pores. Selectivity can be managed by changing solubility with pressure and temperature. Since it is possible to work at low temperatures, it is possible to extract the compounds, which cannot be distilled due to thermal instability [7]. Low viscosities allow for flow with less friction [8] CO2 is the most widely used as a SFE solvent due to its low critical temperature and pressure, no contamination of extracts, its non-flammable and non-toxic properties. It is available in high purity at relatively low cost [9,10]. For these reasons, supercritical CO2 extraction is an efficient and green technology for the extraction of bioactive compounds [11].

2 Experimental

2.1 Raw materials

Melon seeds, naturally dried, were taken from a farmer. The seeds with their shells were milled by using a plant grinder and then grouped into various sizes (0.4 mm, 0.8 mm, 1.2 mm and 1.7 mm) by sieve analysis. CO2 (99.99%) was used as a solvent in SFE.

2.2 SFE system and procedure

Spe-ed SFE series of “Applied Separations” was used as a SFE equipment to extract melon seed oil. The basic components of the SFE system consist of CO2 tube, compressor, pump, extraction vessel, oven and extract accumulator. A more detailed description of SFE system is given elsewhere [12]. 5 g of melon seed was charged into a 100 mL extraction vessel. Glass wool plugs were placed in the entrance and exit of the extraction vessel in order to reduce dead volume then the extraction vessel was placed into the oven. The extraction was started after the desirable temperature, pressure and flow rate were achieved. The oil was collected in the collecting vessel at ambient temperature and pressure. The extractions were carried out between 30-55°C, 150-240 bar, 7-15 g CO2/min, 0.4-1.7 mm mean particle size and 1-4 h.

2.3 Analysis of phytosterols

Saponification of oil was performed at 80°C similarly with the method of Nyam et al. [13]. Unsaponifiable part including phytosterols was extracted with petroleum ether and washed with neutral ethanol-water (1:1, v/v). A sample was taken and then dried under reduced pressure. Trimethylsilyl (TMS) ether derivatives of phytosterols were obtained in the way detailed by Cunha et al. [14]. After cooling of mixture formed from mentioned method, 1 μL of it was injected into the gas chromatography of GC-MS (Thermo Finnigan). The specifications of column, procedure and the temperature programme were given in the previous study [15]. The amounts of the phytosterols were determined as cited by Nyam et al. [13].

3 Results and discussion

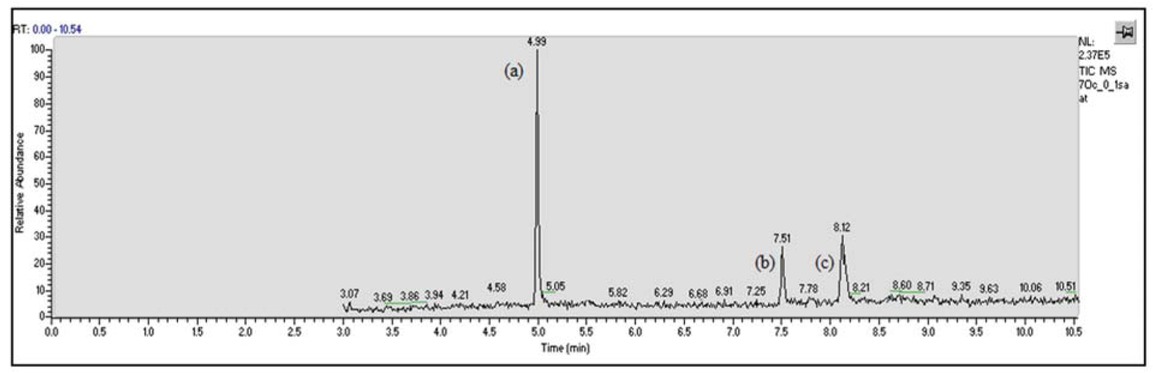

As a result of the analysis with GC-MS, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol were found (Figure 1) in melon seed oil by comparison of their retention times according to the standards which have been purchased. 350-650 g/mol of measured molecular mass range in GC-MS and separating phytosterols from other compounds by saponification provided easy selectable peaks.

GC-MS chromatograms of derivatives (a) internal standard (5α-cholestane); (b) stigmasterol; (c) β-sitosterol.

Other parameters were kept constant at a selected value according to literature research and preliminary experiments to examine the effect of a parameter. Both extraction and analysis trials were performed in triplicate at least.

3.1 Effect of temperature

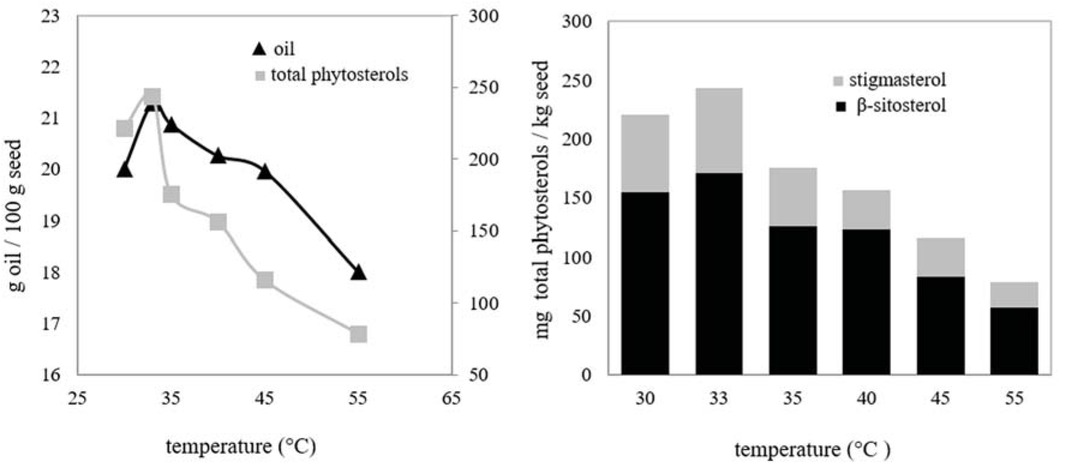

To examine the effect of temperature on the amounts of oil and phytosterols, extractions were performed at a temperature varying between 30-55°C when the other parameters were fixed at 200 bar, 7 g/min, 0.8 mm and 2 h. The results are represented in Figure 2.

Effect of temperature on the amounts of seed oil and phytosterols: 200 bar, 7 g CO2/min, 0.8 mm mean particle size, 2 h.

As seen in Figure 2, up to 33°C, a raise of amounts of both oil and total phytosterols was observed with temperature rising. On the contrary, when 33°C was exceeded, amounts of oil and total phytosterols decreased while the temperature increased. Same tendency was also seen for β-sitosterol and stigmasterol. The temperature on the solubility has two opposing effects. With increasing temperature, the density of the solvent is reduced, resulting in lower solvent power. Contrarily, the vapor pressure of the solutes increases, thus increasing the solubility [16]. It indicated that from 30°C to 33°C, increasing vapor pressures of β-sitosterol, stigmasterol and the other active components in oil were dominant in comparison with the decreasing CO2 density, thus decreasing solvent power. CO2 is already subcritical fluid at 30°C but it has a lot of properties of supercritical fluid [17]. After 33°C, the reduction of SC-CO2 density became more effective. Corroborative results were obtained in the literature. The quantities of oil and β-sitosterol extracted from peach seeds were increased with increasing temperature for the range of 35-40°C and then decreased [15]. In a study by Kawahito et al., β-sitosterol recovery strikingly increased first and then decreased with the rising temperature at 40-80°C and 30 MPa. This result proved that increasing vapor pressure of solute was preponderant at lower temperature [18]. According to another study, it was observed that the effect of temperature on the total wax yield and on the content of phytosterols in the wax extracted from flax straw was important. At a constant pressure in the range of 132-468 bar, yields of total wax and phytosterols first increased, and then decreased with increasing temperature [19]. Between 35-65°C, the amount of oil which was extracted from lotus bee pollen initially increased and then decreased at 200 bar. Higher temperature resulted in lower sterol yields [20]. Between 40-80°C, kenaf seed oil yield [21] and oil recovery from okara [22] declined with increasing temperature at 200 bar. Consequently, 33°C was determined to be preferred temperature value for subsequent experiments.

3.2 Effect of pressure

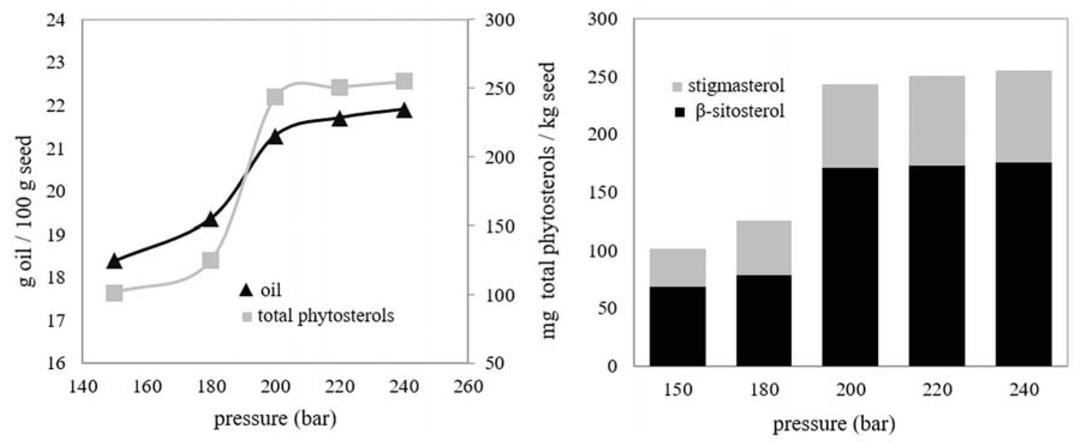

Effect of pressure was examined at 33°C, selected as optimum temperature value, 7 g/ min, 0.8 mm and 2 h. The results are given in Figure 3.

Effect of pressure on the amounts of seed oil and phytosterols: 33°C, 7 g CO2/min, 0.8 mm mean particle size, 2 h.

As can be seen from the Figure 3 the higher the pressure was, the higher the amounts of oil and phytosterols extracted were. It was represented that depending on increasing of pressure, density of CO2 increased so its solvent power increased. Between 150-180 bar, there were increments in the quantities of extracts but not significant when compared with the range of 180-200 bar. It is thought that great part of the solutes was partitioned into SC-CO2 at 180-200 bar. There were insignificant increases in the amounts of extracts and the curve was approximately linear after 200 bar. As a result, 200 bar was determined as the appropriate pressure value. In previously published study [15], altering in the amounts of oil and β-sitosterol with pressure were similar to data which has been obtained in this study. The change in the amount of oil was consistent with the change in another study [22].

3.3 Effect of flow rate of SC-CO2

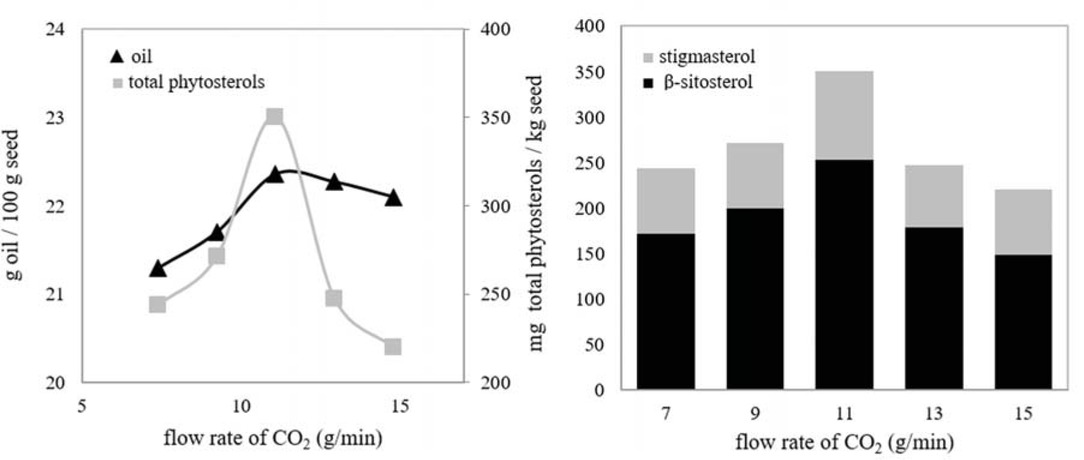

The influence of flow rate of SC-CO2 was investigated between 7 and 15 g CO2/min (Figure 4). Optimum temperature and pressure values had already been determined as 33°C and 200 bar. The other parameter values were 0.8 mm and 2 h.

Effect of flow rate of SC-CO2 on the amounts of seed oil and phytosterols: 33°C, 200 bar, 0.8 mm mean particle size, 2 h.

Figure 4 indicates that the quantities of oil and phytosterols increased from 7 to 11 g/min. It can be explained by the fact that in this range, the external mass transfer resistance or the equilibrium controlled the extraction process. Increased flow rate reduced the external mass transfer resistance. The extraction rate was determined by the flow rate and thus the amount of CO2 fed the extraction vessel [23]. Conversely, further increases in flow rate caused decreases in the amounts of extracts. These decreases suggest that extraction was controlled primarily by diffusion of extracts and increasing the flow rate of SC-CO2 could not control the extraction process hereafter. Increasing the flow rate and thus the linear velocity caused to decrease contact time between SC-CO2 and the seeds resulted in decreases in the amounts of extracts.

It was reported that the flow rate of SC-CO2 had a remarkable influence on the extraction of wax from flax straw [19]. In earlier studies about extraction of different seed oil, similar courses relevant to influence of the flow rate of SC-CO2 had been obtained [15]. As a result, 11 g CO2/min was determined as an optimal value.

3.4 Effect of particle size

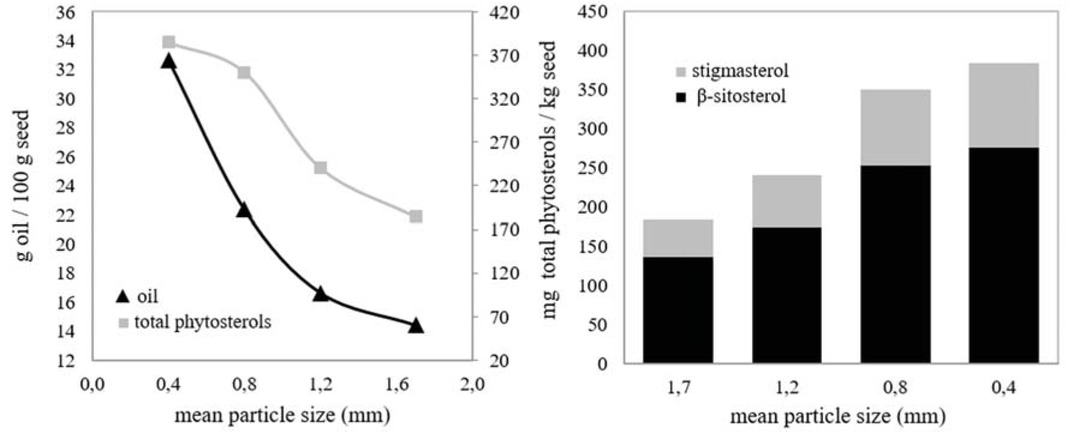

Effect of mean particle size was investigated between 0.4 and 1.7 mm for 2 h of extraction time (Figure 5). Optimum temperature, pressure and flow rate had already been selected as 33°C, 200 bar and 11 g/min.

Effect of mean particle size of the seeds on the amounts of seed oil and phytosterols: 33°C, 200 bar, 11 g CO2/min, 2 h.

As it is understood from Figure 5 the quantities of oils and phytosterols were increased with decreasing mean particle size. High increases in the quantities of oil and total phytosterols (127% and 109%, respectively) were observed between 1.7 mm and 0.4 mm. Smaller mean particle size provided higher contact area between SC-CO2 and the seeds and also reduced the length of diffusion of the solvent [23]. Therefore, higher quantities of oil and phytosterols were extracted. On the other hand, the seeds were not further downsized to avoid channeling problems.

3.5 Effect of extraction time

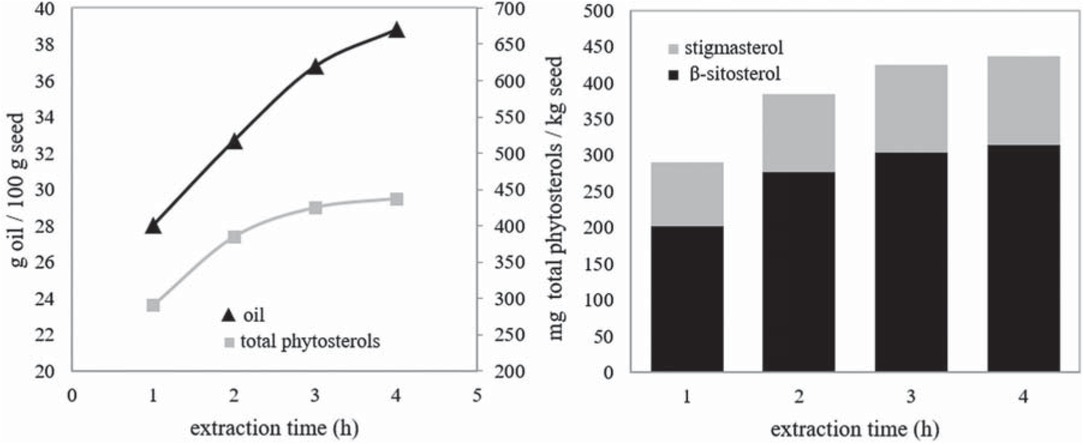

After determining the optimal values of temperature, pressure, flow rate of SC-CO2 and mean particle size (33°C, 200 bar, 11 g CO2/min and 0.4 mm), the optimal extraction time was determined (Figure 6).

The changes in the amounts of seed oil and phytosterols with extraction time: 33°C, 200 bar, 11 g CO2/min, 0.4 mm.

Figure 6 clarifies that the quantities of oil and phytosterols did not change meaningfully from 3 h to 4 h. There were more considerable increases in the quantities of oil and total phytosterols (13% and 10%, respectively) from 2 h to 3 h than from 3 h to 4 h (5% and 3%, respectively). 95% of the oil and 97% of the total phytosterols extracted from melon seeds were obtained at the end of the 3th hour in 4-hour period. Therefore, the optimal extraction time was determined as 3 h.

According to experiment results, optimal quantities of extracted oil, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol were 36.8 g/100 g seed, 304 mg/kg seed and 121 mg/kg seed, respectively, at 33°C, 200 bar, 11 g CO2/min, a mean particle size of 0.4 mm and an extraction time of 3 h.

4 Conclusions

Phytosterols are very important components for human health because they are known to decrease LDL cholesterol and provide protection against various chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer. In this study, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol which are principal phytosterols were detected in melon seed oil. Melon seed oil was obtained by the supercritical CO2 extraction which is a clean and an effective method. The optimal values of the extraction parameters were determined. As a result, obtaining of these healthful compounds with this outstanding method is considered as a promising study.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Gazi University Scientific Research Projects (06/2011-01).

References

[1] Uddin M.S., Ferdosh S., Akanda J.H., Ghafoor K., Rukshana A.H., Ali E., et al., Techniques for the extraction of phytosterols and their benefits in human health: a review. Separ. Sci. Technol., 2018, 53, 2206-2223.10.1080/01496395.2018.1454472Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Shahzad N., Khan W., Shadab M.D., Ali A., Saluja S.S., Sharma S., et al., Phytosterols as a natural anticancer agent: Current status and future perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother., 2017, 88, 786-794.10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.068Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Gylling H., Simonen P., Phytosterols, phytostanols, and lipoprotein metabolism. Nutrients, 2015, 7, 7965-7977.10.3390/nu7095374Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Marangoni F., Poli A., Phytosterols and cardiovascular health. Pharmacol. Res., 2010, 61, 193-199.10.1016/j.phrs.2010.01.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bradford P.G., Awad A.B., Phytosterols as anticancer compounds. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res., 2007, 51, 161-170.10.1002/mnfr.200600164Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] John S., Sorokin A.V., Thompson P.D., Phytosterols and vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol., 2007, 18, 35-40.10.1097/MOL.0b013e328011e9e3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Khosravi-Darani K., Vasheghani-Farahani E., Application of supercritical fluid extraction in biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol., 2005, 25, 231-242.10.1080/07388550500354841Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Sahena F., Zaidul I.S.M., Jinap S., Karim A.A., Abbas K.A., Norulaini N.A.N., et al., Application of supercritical CO2 in lipid extraction – A review. J. Food Eng., 2009, 95, 240-253.10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.06.026Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Lang Q., Wai C.M., Supercritical fluid extraction in herbal and natural product studies – a practical review. Talanta, 2001, 53, 771-782.10.1016/S0039-9140(00)00557-9Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Pourmortazavi S.M., Hajimirsadeghi S.S., Supercritical fluid extraction in plant essential and volatile oil analysis. J. Chromatogr. A, 2007, 1163, 2-24.10.1016/j.chroma.2007.06.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Rawson A., Tiwari B.K., Brunton N., Brennan C., Cullen P.J., O’Donnell C.P., Application of supercritical carbon dioxide to fruit and vegetables: Extraction, processing, and preservation. Food. Rev. Int., 2012, 28, 253-276.10.1080/87559129.2011.635389Suche in Google Scholar

[12] İçen H., Gürü M., Extraction of caffeine from tea stalk and fiber wastes using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluid., 2009, 50, 225-228.10.1016/j.supflu.2009.06.014Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Nyam K.L., Tan C.P., Lai O.M., Long K., Che Man Y.B., Optimization of supercritical fluid extraction of phytosterol from roselle seeds with a central composite design model. Food Bioprod. Process., 2010, 88, 239-246.10.1016/j.fbp.2009.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Cunha S.S., Fernandes J.O., Oliveira M.B.P.P., Quantification of free and esterified sterols in Portuguese olive oil by solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A, 2006, 1128, 220-227.10.1016/j.chroma.2006.06.039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ekinci M.S., Gürü M., Extraction of oil and β-sitosterol from peach Prunus persica seeds using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluid., 2014, 92, 319-323.10.1016/j.supflu.2014.06.004Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Melo M.M.R., Silvestre A.J.D., Silva C.M., Supercritical fluid extraction of vegetable matrices: Applications, trends and future perspectives of a convincing green technology. J. Supercrit. Fluid., 2014, 92, 115-176.10.1016/j.supflu.2014.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Clifford A.A., Williams J.R., Introduction to supercritical fluids and their applications. In: Clifford A.A., Williams J.R. (Eds.), Supercritical Fluid Methods and Protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, New Jersey, 2000.10.1385/1592590306Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Kawahito Y., Kondo M., Machmudah S., Sibano K., Sasaki M., Goto M., Supercritical CO2 extraction of biological active compounds from loquat seed. Sep. Purif. Technol., 2008, 61, 130-135.10.1016/j.seppur.2007.09.022Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Athukorala Y., Mazza G., Optimization of extraction of wax from flax straw by supercritical carbon dioxide. Sep. Sci. Technol., 2011, 46, 247-253.10.1080/01496395.2010.514014Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Xu X., Dong J., Mu X., Sun L., Supercritical CO2 extraction of oil, carotenoids, squalene and sterols from lotus Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn) bee polen. Food Bioprod. Process., 2011, 89, 47-52.10.1016/j.fbp.2010.03.003Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Yazan L.S, Foo J.B., Ghafar S.A., Chan K.W., Tahir P., Ismail M., Effect of kenaf seed oil from different ways of extraction towards ovarian cancer cells. Food Bioprod. Process., 2011, 89, 328-332.10.1016/j.fbp.2010.10.007Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Quitain A.T., Oro K., Katoh S., Moriyoshi T., Recovery of oil components of okara by ethanol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Bioresource Technol., 2006, 97, 1509-1514.10.1016/j.biortech.2005.06.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Reverchon E., de Marco I., Supercritical fluid extraction and fractionation of natural matter. J. Supercrit. Fluid., 2006, 38, 146-166.10.1016/j.supflu.2006.03.020Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Ekinci and Gürü, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering