Abstract

In this prelimnary work, the aim was to fabricate a simple tin (II) sulfide (SnS) quantum dot-sensitized solar cell (QDSSC) from aqueous solution. The SnS QDSSCs were characterized by using current-voltage test (I-V test), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. SEM results showed the presence of TiO2 and SnS elements in the sample, confirming the successful synthesis of SnS quantum dots (QDs). The overall efficiency of QDSSCs increased when concentration of the precursor solutions, which were aqueous sodium sulfide and tin (II) sulfate decreased from 0.5 M to 0.05 M. On the other hand, for a fixed precursor concentration, the efficiency of QDSSC reduced once an optimal cycle of of successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) was achieved. The bandgap energies of QDs obtained by extrapolating the Tauc plot were used to predict the QDs size. In general, the QD size was bigger for samples prepared from precursor concentration of 0.5 M, and with higher number of SILAR cycle used. The best performance was obtained from sample prepared from 0.05 M precursor concentration with 4 SILAR cycles.

1 Introduction

Solar energy is one of the clean and renewable energy technologies available in the world. Compared with current main energy sources, i.e. fossil fuel such as crude oil, coal, and natural gas, it produces no harmful substances to the environment. Solar energy will never be depleted as long as the sun is available. Solar cells function by harvesting the sunlight, and converting it into electricity [1].

In 1954, the first generation of solar cell was made in Bell Laboratories by forming a diffused silicon p-n junction [2]. Silicon was chosen because of the availability and the popularity in semiconductor industry. However, these silicon-based solar cells are expensive to produce. The second generation of solar cells are known as thin film solar cells, which have similar working principle as the first generation solar cells. Thin film solar cells are aimed for mass production. However, deposition of thin film requires high temperature and high vacuum condition which cause high production cost of thin firm solar cells [3]. The combination of knowledge and experience acquired from the first and second generation of solar cells has become the foundation for the third generation solar cells to achieve lower production cost and high energy efficiency which can exceed the theoretical Shockley-Queisser limit of 33% [4, 5]. Solution-processed semiconductor solar cells such as dye-sensitized solar cells and quantum dot-sensitized solar cells (QDSSC) are catergorized as third generation solar cells [1].

Typically, QDSSC consists of photoelectrode, electrolyte, and counter electrode. The photoelectrode consists of conducting glass coated with wide band gap semiconductor, usually titanium dioxide (TiO2) or zinc oxide (ZnO), with semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) attached on it. Commonly used material for counter electrode is platinum (Pt), but other materials like copper (I) sulfate (Cu2S) is also used. QDs are nano-sized particles that are responsible for the light absorbance and generation of electron-hole pairs. The generated excited electrons will then be transfered to the wide band gap semiconductor and ultimately to the external circuit. QDs with small sizes can lead to quantum confinement effect, where the bandgap values of the QDs change accordingly. This effect is beneficial as the response to light can be tuned based on specific bandgap and QD’s size. Many semiconductor materials such as SnS, CdS, CdSe, and PbS have been identified for sensitizing solar cell application [6, 7].

Materials such as CdS, CdSe, and PbS have been commonly researched in the field of QDSSCs due to good optical properties. However, these materials show high toxicity that bring harms to the living creatures and environment, which are inconsistent with the main purpose of solar cells as a clean and green energy generator. On a bright side, few researches have demonstrated the application of SnS in QDSSCs. SnS is cheap and less toxic as compared with the materials mentioned above. SnS has been identified as a potential material for solar cells due to its low bulk bandgap of 1.09-1.30 eV and high conductivity and absorption coefficient. Besides, Sn and S are abundant on earth.

On the fabrication method of QDs, solution processed method like successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) is frequently employed. This method was first reported by Ristov et al. in 1985 [8]. SILAR method is basically an immersion of substrate in different cationic and anionic precursor solutions, and rinsing in deionized water for film growth purpose. The substrate must be rinsed after each dipping in precursor solution to washed away any unreacted ions. In general, SILAR method is an advanced version of chemical bath deposition (CBD) method. However, in CBD method, all the precursors are mixed together in one container, while in SILAR method, the precursors are separated. Thin film in SILAR method grows layer by layer, hence the film thickness can be controlled easily by varying the number of dipping cycle [9].

In this work, solution processed SnS QDSSCs were fabricated and investigated. Unlike previous reported studies, SnS was synthesized from SO42-based salt as precursor, all in aqueous solution. The effect of concentration of precursor solution during the preparation of QDs was investigated. Besides, the number of dipping cycles on the efficiency QDSSC was also studied.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) conducting glass (13 Ω/sq.), titania paste and platinum precursor were purchased from Dyesol, Australia. Chemical reagents like SnSO4, Na2S and S were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, unless otherwise specified. All chemical reagents were used as received due to high purity grade.

2.2 Electrodes preparation

Anode electrodes were prepared by deposition of SnS QDs which were fabricated via SILAR technique. Prior to that, TiO2 layer was deposited on the FTO glass via doctor blading method, which was then followed by sintering at 450°C for 30 min. The layer was prepared from titania paste, without dilution. The treated electrodes were then dipped into various concentrations of SnSO4 and Na2S acqueous solutions. Steps of SnS QDs deposition are described as below:

Immersed electrode in SnSO4 aqueous solution for 4 min.

Rinsed electrode in deionized water for 1 min.

Immersed electrode in Na2S aqueous solution for 4 min.

Secondary rinsing of electrode in deionized water for 1 min.

The above steps are regarded as 1 cycle. The steps were repeated for 0.05 M and 0.5 M precursor solutions, and from 2 to 6 cycles for each concentration of precursor solutions. Samples were numbered based on number of SILAR cycle. For example, A3 represents sample from set A prepared with 3 SILAR cycles. The complete samples ID are shown in Table 2.

Elemental composition of sample TiO2/SnS as detected via EDX analysis.

| Element | Atomic % |

|---|---|

| Ti | 16.42 |

| O | 81.95 |

| Sn | 0.98 |

| S | 0.65 |

| Total | 100.00 |

Relationship between concentration, number of SILAR cycles, and V OC, J SC, FF, and efficiency of SnS QDSSCs.

| Concentration (M) | Sample ID | No. of cycle | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF (%) | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | C2 | 2 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 32.0 | 0.031 |

| C3 | 3 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 46.6 | 0.066 | |

| C4 | 4 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 43.8 | 0.072 | |

| C5 | 5 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 33.4 | 0.029 | |

| C6 | 6 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 27.3 | 0.008 | |

| 0.1 | A2 | 2 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 38.3 | 0.024 |

| A3 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 29.6 | 0.035 | |

| A4 | 4 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 34.3 | 0.055 | |

| A5 | 5 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 42.0 | 0.048 | |

| A6 | 6 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 31.3 | 0.032 | |

| 0.5 | B2 | 2 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 39.9 | 0.010 |

| B3 | 3 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 37.8 | 0.030 | |

| B4 | 4 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 43.4 | 0.023 | |

| B5 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 34.3 | 0.016 | |

| B6 | 6 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 37.5 | 0.012 | |

As for the counter electrode, Pt-coated glass plate was prepared by spin coating Plastisol solution (or platinum precursor solution) onto a FTO conducting surface, followed by sintering at 450˚C for 30 min.

2.3 Device assembly

After solution dipping and heat treatment, solar cell was assembled in sandwich type architecture with generic polysulfide liquid electrolyte. The electrolyte consisted of 1.0 M Na2S and 0.1 M S in aqueous solution [10]. Parafilm was used as spacer, where the centre of the film was cut out slightly larger than the area of the titania film before placing it on the substrate. Then electrolyte was added on top of the TiO2/QDs film surface via pipette. Lastly, the photoanode and counter electrode were sandwiched and clamped together.

Materials characterizations were performed using scanning electron microscope (SEM) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer. Device performance was validated with Keithley 2400 electrometer under light source at 1 sun. For SEM analysis, Hitachi S-3400N SEM was used to study the surface structure and morphology of the substrates. For UV-Vis analysis, model Cary 100 Conc. was used to analyze the QDs-sensitized substrate. The absorption rate of the samples was determined from the analysis.

3 Results and discussion

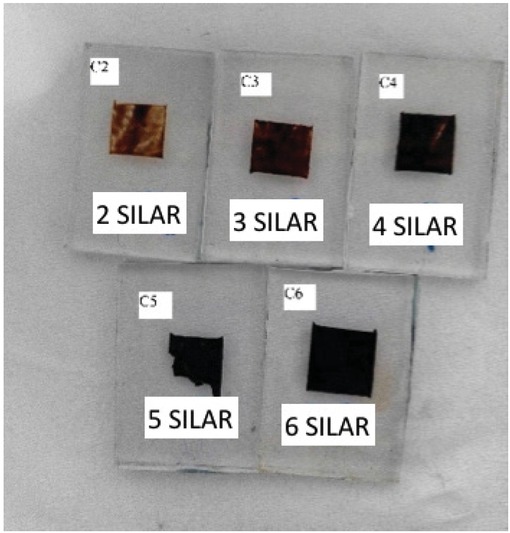

Three sets of QDSSC devices were fabricated from three different precursor concentrations (i.e. 0.05 M, 0.1 M and 0.5 M). These molarities were selected based on previous reported studies [11, 12]. As these studies did not have a thorough investigation on the precursor optimization, we selected a set of general acceptable molarities which started from low molarity. We confined the study to a few precursor concentrations and capped it at 0.5 M. In each set, the anionic and cationic precursor concentrations were maintained at the same concentration level. For example, devices fabricated from 0.05 M were prepared from 0.05 M of SnSO4 and 0.05 M Na2S acqueous solution. The fabricated SnS-sensitized TiO2 electodes exhibited a dark brown color as shown in Figure 1. With higher precursor concentration, the sensitized layer became black. The same observation is also true for higher SILAR cycles. In this work, the SILAR cycles were limited to maximum 6 cycles as more dipping cycles would result in QDs overloading [13, 14].

SnS QD-sensitized electrode sample. All samples show good film adhesion to the substrate despite irregular surface area.

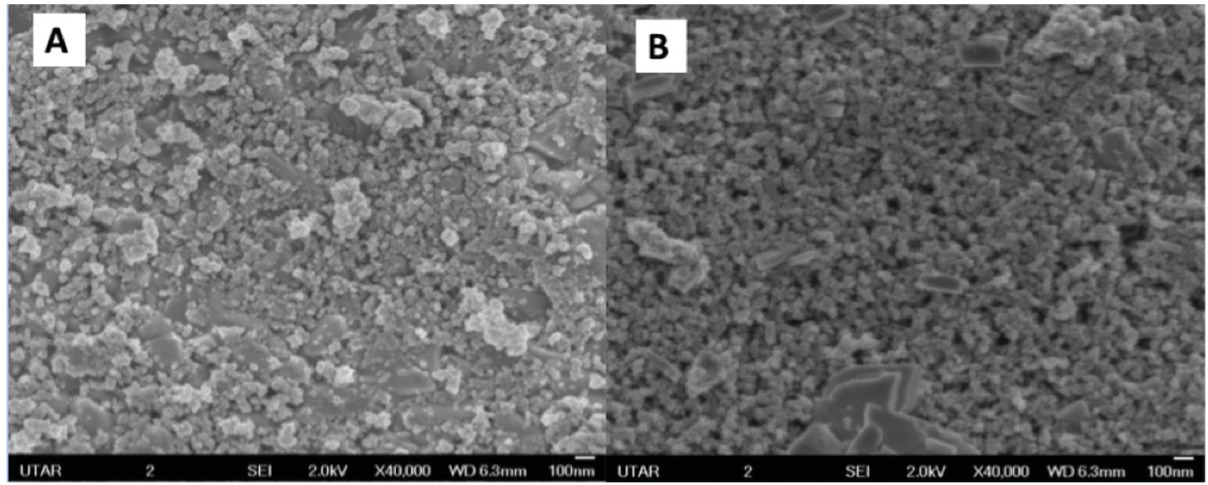

The prepared QD-sensitized TiO2 electrodes were then characterized with SEM imaging. Figure 2 shows the surface morphology of the fabricated TiO2 and TiO2/SnS layer of the electrode samples. TiO2 was successfully deposited on the substrate, as porous structure of TiO2

SEM micrographs of photoanode surface at 40,000x magnification. (a) Bare TiO2 layer; (b) TiO2/SnS layer.

nanoparticles was observed. The TiO2 particles were also “sensitized” (or adsorbed) with SnS layer, where reduced porosity of the TiO2 layer was observed. The porosity of the TiO2 layer was determined qualitatively via Image-J software. The presence of Sn and S elements was also verified by EDX analysis on the same surface analysis (see Table 1 for elemental analysis). In the preparation steps of the TiO2 layer, it is crucial to ensure no cracks are visible as such cracks will cause high shunt resistance, RSH and lower the efficiency of the device [15].

The performances of the fabricated SnS QDSSCs are shown in Figure 3. The J-V curves of the individual SnS QDSSCs prepared from 0.05 M, 0.1 M and 0.5 M precursor concentrations are shown in Figures 3a-c, respectively.

J-V curves for SnS QDSSC prepared from (a) 0.05 M precursor concentration; (b) 0.1 M precursor concentration; (c) 0.5 M precursor concentration with various dipping cycles. The efficiency trend is shown in (d).

Meanwhile, Figure 3d depicts the performance trends of the sample sets. On the other hand, the performance parameters of the SnS QDSSCs are tabulated in Table 2, with information pertaining to the concentrations of precursor solution and SILAR cycles.

From the result obtained, for samples prepared from 0.05 M precursor solutions, the optimal number of dipping cycles is 4 cycles where the device exhibits the highest open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current density (JSC), and efficiency at 0.43 V, 0.40 mA/cm2, and 0.07%, respectively, within the same group. The overall performance is still low compared to other types of QDSSC like CdS and CdSe. This could be due to the intrinsic optical properties of SnS itself [10, 16, 17]. The low performance was also confirmed by other research groups although some were able to achieve better result due to optimization done on the photoanode layer [11, 12]. Further increasing the number of dipping cycles after 4 SILAR cycles does not show any significant improvement on the performance. In fact, the performance reduced dramatically with dipping cycles above 4 cycles. This could be attributed to the overloading of SnS QDs on the TiO2 particles which subsequently increased the charge recombination rate at the TiO2 interfaces [18]. At

this point, it can be assumed that saturation of QDs has been achieved. This observation is in-line with the work by Deepa et al. [19]. Also noted that the J-V curves have minor peak near the open circuit voltage, which indicates possible presence of pin hole in the sample.

Samples prepared from 0.1 M precursor concentration shows a similar pattern in which the best performing device is achieved when the sample was prepared with 4 SILAR cycles. Such sample has VOC value of 0.34 V, JSC value of 0.47 mA/cm2, fill factor (FF) value of 34.3%, and efficiency of 0.055%. As for the samples prepared from 0.5 M precursor concentration, sample prepared with 3 SILAR cycles exhibit the best overall performance. It has VOC of 0.31 V, JSC of 0.25 mA/cm2, and efficiency of 0.030%. All the samples exhibit a relatively low value of FF, which is less than 50%. This signifies a substantial charge recombination which needs to be tackled with. One of the remedies is to apply passivation layer [20].

On the other hand, samples prepared from higher precursor concentration have lower efficiency as higher precursor concentration leads to multiple nucleation sites for QD growth. Eventually, more QDs are formed until blocking the TiO2 interface pathway. Thus, the thickening of SnS QD layers results in the impediment of electrons transfer across the interface. Meanwhile, VOC was observed to increase with incremental of SILAR dipping cycles, up to optimum dipping cycle. The increased of VOC is due to the increase of Fermi level of the photoelectrode with the presence of SnS QDs, allowing more injection of electrons from SnS QDs to the TiO2 layer. Upon reaching the optimum parameter limits, JSC and VOC of the samples reduced which are due to the decrease in electrons recombination resistance in the devices led by overloading of SnS on the surface of TiO2 layer. Overloading of SnS sensitizer also causes the reduction of VOC and FF because it blocks the electrolyte penetration into the porous thin film [21]. One of the major contributing factors to the low performance of solar cell is the high charge recombination rate. Although impedance spectroscopy was not performed, judging from the performance parameters (as shown in Table 2), one can predict the low electrons recombination resistance within the interfaces of the samples. Such phenomenon can result in high charge transfer resistance Rct with small capacitance Cμ, signifying slow charge transport at the interfaces. Ultimately, their electron lifetime values would be at the low side, demonstrating ineffective electrons transfer, which result in lower energy conversion efficiency [22, 23, 24, 25].

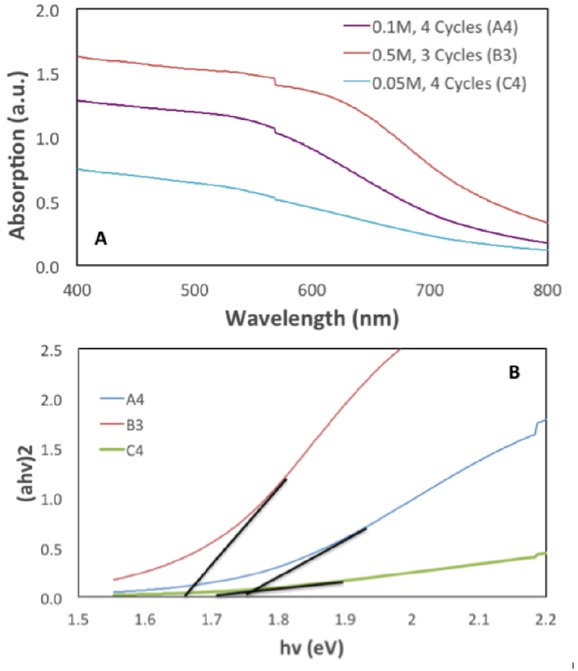

In the later stage, SnS QDSSC devices with the best parameter performances determined from I-V test were selected for UV-Vis absorption analysis in order to estimate the bandgap energy of the QD. Other samples were not tested for their absorption as the value from the best performing sample in each set is sufficient to provide the necessary information. Absorption spectra of TiO2/SnS thin film with different concentration and SILAR cycles are shown in Figure 4a. The bandgap of samples are determined by extrapolating the Tauc plot to x-axis as shown in Figure 4b (for selected samples A4, B3 and C4).

(a) Absorption spectra of selected samples of TiO2/SnS multilayer film; (b) Tauc plots of selected samples of TiO2/SnS multilayer film.

Absorption spectra of TiO2/SnS samples increased as the number of SILAR cycle increased. Also, the absorbance is higher for samples fabricated with higher precursor solution concentration. This is due to more SnS QDs formed on the TiO2 layer which allow more light absorption. From Tauc plot analysis, samples with more SILAR cycles tend to have lower bandgap energy. The bandgap energy values for the selected samples are tabulated in Table 3. It is also observed that bandgap energy is also increased with the increasing deposition concentration except for samples prepared from 0.5 M precursor concentration.

SnS QD size and its corresponding bandgap energy.

| Concentration (M) | Sample ID | Bandgap energy (eV) | QD radius (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05M | C2 | 1.77 | 6.31 |

| C3 | 1.73 | 6.52 | |

| C4 | 1.71 | 6.68 | |

| C5 | 1.63 | 7.45 | |

| C6 | 1.56 | 8.39 | |

| 0.1M | A2 | 1.80 | 6.25 |

| A3 | 1.79 | 6.27 | |

| A4 | 1.75 | 6.38 | |

| A5 | 1.71 | 6.69 | |

| A6 | 1.68 | 7.06 | |

| 0.5M | B2 | 1.69 | 7.00 |

| B3 | 1.67 | 7.03 | |

| B4 | 1.62 | 7.55 | |

| B5 | 1.60 | 7.68 | |

| B6 | 1.58 | 8.46 | |

The QD size was estimated from the absorption spectrum according to reported method [9]. The bulk bandgap energy for SnS is 1.3 eV, according to Deepa et al. [19]. The SnS QDs sizes increased with more SILAR cycles in each set of samples with the same concentration. For example, TiO2/SnS samples prepared from 0.05 M precursor solution, the size of SnS QDs increased from 6.68 nm to 8.39 nm when the number of cycles increased from 4 to 6 cycles. This shows the quantum confinement effect as the dipping cycle and precursor concentration increased. By comparing among the different precursor concentration, there is an optimum QD size with its corresponding bandgap for the best device performance. The reduction of performance with higher QD size could be linked to the thickening

layer of the QDs which reduce the charge recombination resistance within the interface [26].

As the overall performance of the cells is still very low, plan is under way for optimization study. Although other semiconductor QD materials like CdS, CdSe and PbS have shown better performance, SnS being less toxic than the usual QD materials could have a better future application should more effort on optimization work is carried out. It must also be noted that the assembly cell samples in this work used generic setup in order to eliminate other positive contributing effect to the result, unlike other reported result in literature where optimized setup has been used. Some of the parameters that need to be focused on include dipping time and different precusor used. The deposition of blocking layer and passivation layer are also crucial for the better performance of the cells, which are not being applied in this preliminary study. Optimized electrolyte should also be looked into as different semiconductor QDs could perform well in different composition of polysulfide electrolyte [27, 28]. Lastly, suitable counter electrode materials should also be considered. Typically, Cu2S counter electrode produces better result when used in QDSSC [29, 30, 31, 32].

4 Conclusion

Tin (II) sulfide QDSSCs have been successfully fabricated using SILAR method from aqueous solution. SEM and EDX analysis on TiO2/SnS surface showed the presence of SnS nanoparticles attached to the TiO2 particles. The devices performances were characterized using I-V tester and solar simulator. The overall efficiency of SnS QDSSCs increased when the concentration of precursor solution for QDs fabrication decreased from 0.5 M to 0.05 M. For a fixed precursor concentration, the efficiency of QDSSCs reduced once the optimal SILAR cycles were achieved. Further increasing the SILAR cycles did not increase the conversion efficiency of QDSSCs due to overloading of QDs where the aggregates would obstruct the electron transfer through the interface. The optimum SILAR cycles for 0.05 M and 0.1 M precursor concentration were 4 cycles, while for 0.5 M, optimum SILAR cycle was 3 cycles. The best performance was obtained from sample prepared from 0.05 M concentration, 4 SILAR cycles. Although the performance is relatively low, this work shows the feasibility of SnS QDs as alternative green material for QDSSC devices.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the research fund provided by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) of Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme no. FRGS/1/2015/SG06/UTAR/02/1.

Abbreviations

- CBD

Chemical bath deposition

- FF

Fill factor

- FTO

Fluorine-doped tin oxide

- I-V

Current-voltage

- QDs

Quantum dots

- QDSSC

Quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- SILAR

Successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction

- SnS

Tin (II) sulfide

- UV-Vis

Ultraviolet-visible

- VOC

Open-circuit voltage

- JSC

Short-circuit current density

References

[1] Jun H.K., Careem M.A., Arof A.K., Quantum dot-sensitized solar cells—perspective and recent developments: A review of Cd chalcogenide quantum dots as sensitizers. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev., 2013, 22, 148-167.10.1016/j.rser.2013.01.030Search in Google Scholar

[2] Green M.A., Silicon Photovoltaic Modules: A Brief History of the First 50 Years. Prog. Photovolt: Res. Appl., 2005, 13, 447-455.10.1002/pip.612Search in Google Scholar

[3] Shah A., Torres P., Tscharner R., Wyrsch N., Keppner H., Photovoltaic Technology: The Case for Thin-Film Solar Cells. Science, 1999, 285, 692-698.10.1126/science.285.5428.692Search in Google Scholar

[4] Grätzel M., Photoelectrochemical cells. Nature, 2001, 414, 338-344.10.1142/9789814317665_0003Search in Google Scholar

[5] Shockley W., Queisser H.J., Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of p‐n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510-519.10.1063/1.1736034Search in Google Scholar

[6] Duan J., Zhang H., Tang Q., He B., Yu L., Recent advances in critical materials for quantum dot-sensitized solar cells: a review. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 17497-17510.10.1039/C5TA03280FSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Rühle S., Shalom M., Zaban A., Quantum‐Dot‐Sensitized Solar Cells. ChemPhysChem, 2010, 11, 2290-2304.10.1002/cphc.201000069Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ristov M., Sinadinovski G.J., Grozdanov I., Chemical deposition of Cu2O thin films. Thin Solid Films, 1985, 123, 63-67.10.1016/0040-6090(85)90041-0Search in Google Scholar

[9] Jun H.K., Careem M.A., Arof A.K., Fabrication, Characterization, and Optimization of CdS and CdSe Quantum Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells with Quantum Dots Prepared by Successive Ionic Layer Adsorption and Reaction. Int. J. Photoenergy, 2014, Article ID 939423.10.1155/2014/939423Search in Google Scholar

[10] Deepa K.G., Sunil M.A., Nagaraju J., SnS quantum dot solar cells with Cu2S as counter electrode. IEEE 38th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, 2012, 000798-000800.10.1109/PVSC.2012.6317724Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hortikar S.S., Kadam V.S., Rathi A.B., Jagtap C.V., Pathan H.M., Mulla I.S., et al., Synthesis and deposition of nanostructured SnS for semiconductor-sensitized solar cell. J. Solid State Electrochem., 2017, 21, 2707-2712.10.1007/s10008-017-3642-zSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Zhang X.-P., Lan Z., Chen L., Gao S.-W., Wu W.-X., Que L.-F., et al., Preparation and photovoltaic performance of SnS sensitized nanocrystallite TiO2 photoanode. J. Inorg. Mater., 2013, 28, 1093-1097.10.3724/SP.J.1077.2013.12757Search in Google Scholar

[13] Liu I.-P., Chang C.-W., Teng H., Lee Y.L., Performance Enhancement of Quantum-Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells by Potential-Induced Ionic Layer Adsorption and Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2014, 6, 19378-19384.10.1021/am5054916Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Mehrabian M., Mirabbaszadeh K., Afarideh H., Solid-state ZnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell fabricated by the Dip-SILAR technique. Phys. Scr., 2014, 89, 085801.10.1088/0031-8949/89/8/085801Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ha T.T., Lam Q.V., Huynh T.D., Quantum dots-sensitized solar cell: SILAR cycles effect on the parameters of photovoltaic. Int. J. Latest Res. Sci. Tech., 2014, 3, 127-132.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Guo W., Shen Y., Wu M., Wang L., Wang L., Ma T., SnS‐Quantum Dot Solar Cells Using Novel TiC Counter Electrode and Organic Redox Couples. Chem.-Eur. J., 2012, 18, 7862-7868.10.1002/chem.201103904Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Deepa K.G., Nagaraju J., Growth and photovoltaic performance of SnS quantum dots. Mater. Sci. Eng. B, 2012, 177, 1023-1028.10.1016/j.mseb.2012.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[18] Mora-Sero I., Gimenez S., Fabregat-Santiago F., Gomez R., Shen Q., Toyoda T., et al., Recombination in Quantum Dot Sensitized Solar Cells. Acc. Chem. Res., 2009, 42, 1848-1857.10.1021/ar900134dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Deepa K.G., Nagaraju J., Development of SnS quantum dot solar cells by SILAR method. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process., 2014, 27, 649-653.10.1016/j.mssp.2014.08.006Search in Google Scholar

[20] Lan X., Voznyy O., Kiani A., Garcia de Arquer F.P., Abbas A.S., Kim G.H., et al., Passivation Using Molecular Halides Increases Quantum Dot Solar Cell Performance. Adv. Mater., 2016, 28, 299-304.10.1002/adma.201503657Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Tsukigase H., Suzuki Y., Berger M.H., Sagawa T., Yoshikawa S., Synthesis of SnS Nanoparticles by SILAR Method for Quantum Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotech., 2011, 11, 1914-1922.10.1166/jnn.2011.3582Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Kim H.-J., Xu G.-C., Gopi C.V.V.M., Seo H., Venkata-Haritha M., Shiratani M., Enhanced light harvesting and charge recombination control with TiO2/PbCdS/CdS based quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. J. Electroanal. Chem., 2017, 788, 131-136.10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.02.005Search in Google Scholar

[23] Gopi C.V.V.M., Venkata-Haritha M., Seo H., Singh S., Kim S.-K., Shiratani M., et al., Improving the performance of quantum dot sensitized solar cells through CdNiS quantum dots with reduced recombination and enhanced electron lifetime. Dalton Trans., 2016, 45, 8447-8457.10.1039/C6DT00283HSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Samadpour M., Improving the parameters of electron transport in quantum dot sensitized solar cells through seed layer deposition. RSC Adv., 2018, 8, 26056-26068.10.1039/C8RA04413ASearch in Google Scholar

[25] Wu Q., Hou J., Zhao H., Liu Z., Yue X., Peng S., et al., Charge recombination control for high efficiency CdS/CdSe quantum dot co-sensitized solar cells with multi-ZnS layers. Dalton Trans., 2018, 47, 2214-2221.10.1039/C7DT04356BSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Mora-Seró I., Giménez S., Moehl T., Fabregat-Santiago F., Lana-Villareal T., Gómez R., et al., Factors determining the photovoltaic performance of a CdSe quantum dot sensitized solar cell: the role of the linker molecule and of the counter electrode. Nanotech., 2008, 19, 424007.10.1088/0957-4484/19/42/424007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Jun H.K., Careem M.A., Arof A.K., A Suitable Polysulfide Electrolyte for CdSe Quantum Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells. Int. J. Photoenergy, 2013, Article ID 942139.10.1155/2013/942139Search in Google Scholar

[28] Lee Y.L., Chang C.-H., Efficient polysulfide electrolyte for CdS quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources, 2008, 185, 584-588.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.07.014Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hessein A., Wang F., Masai H., Matsuda K., El-Moneim A.A., Improving the stability of CdS quantum dot sensitized solar cell using highly efficient and porous CuS counter electrode. J. Renew. Sust. Energy, 2017, 9, 023504.10.1063/1.4978346Search in Google Scholar

[30] Gopi C.V.V.M., Ventaka-Haritha M., Kim S.-K., Kim H.-J., Facile fabrication of highly efficient carbon nanotube thin film replacing CuS counter electrode with enhanced photovoltaic performance in quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources, 2016, 311, 111-120.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.02.039Search in Google Scholar

[31] Gopi C.V.V.M., Ravi S., Rao S.S., Reddy A.E., Kim H.-J., Carbon nanotube/metal-sulfide composite flexible electrodes for high-performance quantum dot-sensitized solar cells and supercapacitors. Sci. Rep., 2017, 7, 46519.10.1038/srep46519Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Jun H.K., Careem M.A., Arof A.K., Performances of some low-cost counter electrode materials in CdS and CdSe quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett., 2014, 9, 69.10.1186/1556-276X-9-69Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2019 Ngoi and Jun, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering