Abstract

Uranium plant wastewater was treated in laboratory scale experiments by employing zero valent iron powder. Batch experiments conducted by the response surface methodology (RSM) proved significant decrease in concentrations of uranium due to a decrease in an oxidation-reduction potential and an increase in pH relative to an application of zero valent iron powder. Results indicated that it is effective on the removal of uranium from uranium plant wastewater with the uranium concentration of 2772.23 μg/L due to the adding of zero valent iron powder. it was found that the scope of pH is widely from 3 to 5 from the experimental data obtained in this study. The predicted model obtained from response surface methodology is in accordance with experimental results.

1 Introduction

Processing of uranium ores for nuclear power production has resulted in plenty of radioactive dust generation with serious impact on the environment [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Radionuclides such as uranium and its compounds deserve special attention due to their high heavy-metal toxicity and radioactivity [6,7]. The toxicity of uranium (VI) ions in the form of UO22+, existed in uranium plant wastewater systems, even at micro level, has been a public health issue over the years [8]. So, the study on removal of uranium from wastewater is significant. To be effective in the long run, any remediation technique for uranium must be target on both mobile aqueous uranium (VI) precipitates and uranium (VI) species which may be longstanding sources [9].

The uranium content of uranium plant wastewater used as study object in this paper is 2772.23 μg/L. It is 55 times more than the emission value of 50 μg/L proposed in the Regulations for radiation protection for uranium processing and fuel fabrication facility (EJ1056-2005) [10]. Therefore, affordable, efficient and applicable technology is necessary to reduce the health risk by mitigating or eliminating the uranium removal from the uranium plant wastewater. To improve removal efficiency of uranium, optimization method was used to optimize the operation conditions such as pH, dosage of zero valent iron powder, reaction time. Zero valent iron was used to reduce soluble uranium (VI) aqueous species to undissolved uranium (IV) sediments in this paper.

Response surface methodology (RSM), one of the most economical and practical solutions to evaluate single and combinatorial factors of experiment variables which lead to output responses [11, 12, 13]. could be utilized to accomplish the real design of experiments methods. Due to application of the RSM, less time consumption and fewer tests are consumed compared with actual experimental study [14,15]. The results of RSM analysis would provide the best system performance for the entire optimization set [16,17]. In this study, RSM was employed to study the influence of solution pH, reaction time and dosage of zero valent iron on removal efficiency of uranium. In the course of the study, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to detect the uranium content of solution. Five measurements were averaged to minimize the error. The detection range of ICP-MS is between 10-9-1 mg/ L with relative standard deviation of less than 5%.

Response surface methodology (RSM) was employed to optimize the uranium removal process from uranium plant wastewater with the aim of uranium contents less than 50 μg/L. RSM is important for the process under study, because it has been used in empirical studies to assess the impact of input parameters on a set of dependent variables [18,19]. Three variables of pH, dosage of zero valent iron powder and reaction time have been performed. Each treated wastewater sample has been characterized in uranium removal efficiency terms. The RSM was applied to determine the best uranium removal process conditions by using pH, dosage of zero valent iron powder and reaction time data as dependent variables. The optimum combination predicted by RSM was obtained through experiments, whereby almost complete uranium removal with uranium removal efficiency of 99.66%, by using amount of 3 g/ L zero valent iron, 52.5 min reaction time and pH of 5.

2 Experimental procedure and design

2.1 Experimental procedure

The uranium plant wastewater used in this paper was obtained from purification processing with the uranium concentration of 2772.23 μg/L, the pH value of 8.69. The zero-valent iron was of analytical pure grade with above 98% purity. Extraction raffinate with uranium concentration of 2984.1 μg/L, which pH value was 0.12, was used to pretreat pH adjustment of wastewater.

2.2 Experimental design

Many research workers have done lots of work on enhancing uranium removal efficiency from uranium-containing wastewater so far [20]. Uranium concentration of 50 μg/L is allowed to discharge instead of 300 μg/L mentioned in the Integrated Wastewater Discharge Standard (GB8798-1996) [21], according to the Regulations for radiation protection for uranium processing and fuel fabrication facility (EJ1056-2005). Therefore, an innovative statistical approach with high uranium removal efficiency is imperative.

The RSM establishes a set of mathematical models which represents the response surfaces of the measured property (uranium removal efficiency, in this study) through a given set of input variables (pH, dosage of zero valent iron powder, in that case, reaction time) In a particular area of interest. In this study, RSM was used to find the maximum of a particular response (maximum uranium removal efficiency) determining the input variables (pH, dosage of zero valent iron powder or reaction time) that produced the maximum response, and so, the optimum uranium removal technological conditions.

3 Results and discussion

The uranium removal efficiency obtained from RSM experiments are listed in Table 1, along with their units, according to RSM design. The entire set of runs is shown in Table 1. The RSM has the abilities of estimation and prediction abilities to build effective models with maximum responses. Besides that, a set of mathematical models are established which represent the response surfaces of uranium removal efficiency by a given set of input variables (pH, reaction time and dosage of zero-valent iron powder, in that case) In a particular area of interest. The multiple regression coefficients obtained by the second-order polynomial model for predicting uranium removal efficiency by using the least squares technique, are summarized in Eq. 1.

Uranium removal experimental design used in RSM studies by using process variables showing observed values of uranium removal efficiency.

| Run | Variables | Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (-) | Reaction time (min) | Dosage of zero-valent iron powder (g) | Uranium removal efficiency (%) | |

| A | B | C | Y | |

| 1 | 3 | 30 | 0.4 | 92.26 |

| 2 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 98.50 |

| 3 | 8.36 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 51.42 |

| 4 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.26 | 99.20 |

| 5 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.94 | 99.63 |

| 6 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 99.45 |

| 7 | 7 | 75 | 0.4 | 88.09 |

| 8 | 3 | 75 | 0.4 | 98.54 |

| 9 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 99.66 |

| 10 | 5 | 14.66 | 0.6 | 99.21 |

| 11 | 3 | 75 | 0.8 | 99.46 |

| 12 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 97.70 |

| 13 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 98.59 |

| 14 | 1.64 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 98.46 |

| 15 | 3 | 30 | 0.8 | 98.17 |

| 16 | 7 | 30 | 0.8 | 90.04 |

| 17 | 5 | 90.34 | 0.8 | 99.50 |

| 18 | 5 | 52.5 | 0.8 | 99.22 |

| 19 | 7 | 75 | 0.8 | 87.18 |

| 20 | 7 | 30 | 0.4 | 89.04 |

The F test analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the model equation. ANOVA evaluations of the model, given in Table 2, suggest that the experiments could be described by this model. The significance of each coefficient was determined by P-value and F-value. As shown in Table 2, the prob > F-values for uranium removal efficiency is lower than 0.05, which indicating that quadratic models were significant [22]. The p values of both responses are less than 0.1, which indicates that lack of fit for the model was significant. The normal probability of the residuals (R2 = 0.8542) indicated that there was no anomaly in the adopted methodology. The “lack of fit test” compares residuals to “pure errors” from repeated experimental design points. Adequate accuracy in measuring SNR and SNR greater than 4 is desirable. The ratio of 9.899 indicated a sufficient signal. The model is significant to the whole process, due to high value of adequate precision.

ANOVA analysis for responses Y [uranium removal efficiency (%)].

| Source | Sum of squares | DF | Mean square | F value | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Y | |||||

| Model | 1951.82 | 9 | 216.87 | 6.51 | 0.0036 Significant |

| Residual | 333.26 | 10 | 33.33 | ||

| Lack of fit | 333.26 | 5 | 66.12 | 124.03 | < 0.0001 Significant |

| Pure error | 2.67 | 5 | 0.53 | ||

| R2=0.8542 | |||||

| Pred R-Squared = -0.1013 | |||||

| Adeq Precision = 9.899 | |||||

In the model ANOVA, the correlation coefficient R2 of the quadratic regression equation was 0.8542, which indicated model fit the actual situation very well. F-value of 6.51 implies the significance of the models. Because of noise there is only a 0.36% chance of such a large “model f value”. The values of “Prob > F” are less than 0.05 that indicate the model term is significant. On this occasion, A2 and A are significant model terms. A negative “Pred R-Squared” with value of -0.1013 indicates the overall mean is better at predicting responses than the current model. “Adeq Precision” is desirable for signal to noise ratio measurements. In this paper, the ratio of uranium removal experiments is 9.899, a ratio greater than 4, that indicates an adequate signal. This model could be used to navigate the design space.

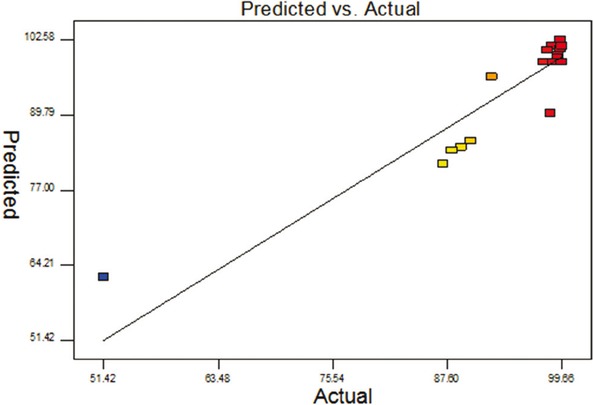

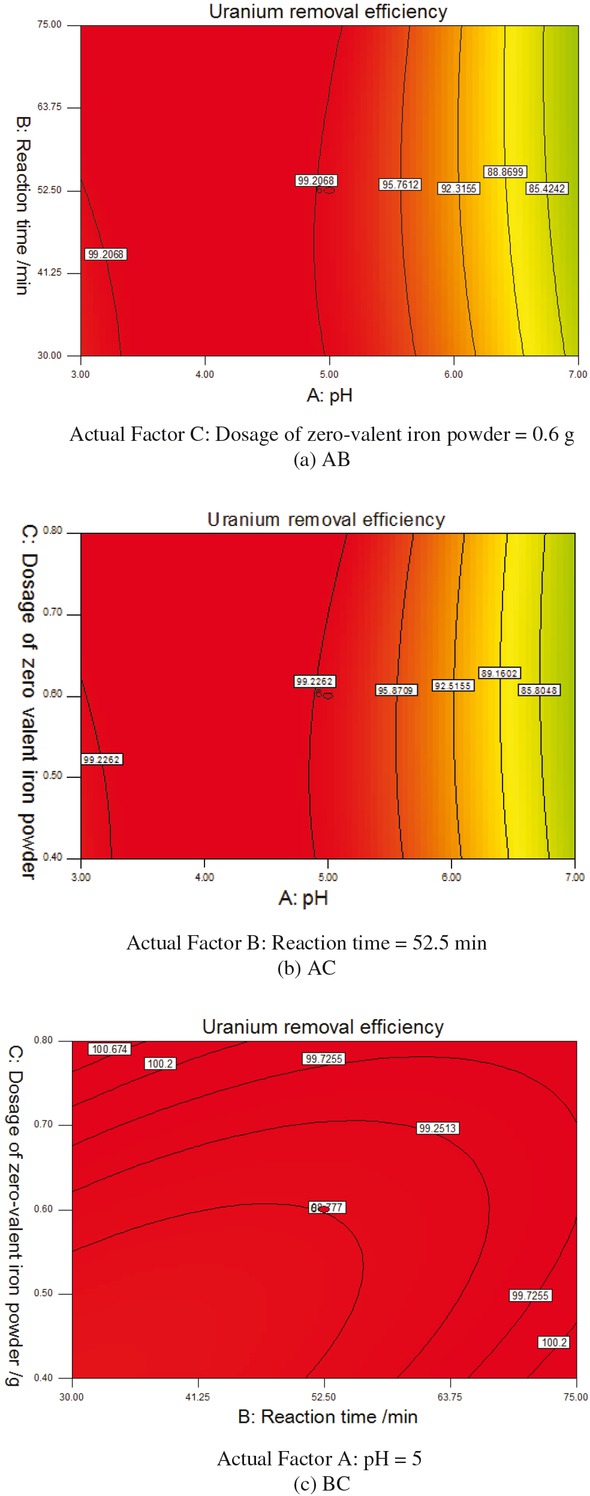

The predicted and actual uranium removal efficiency were plotted in Figure 1. As Figure 1 shown, the response predicted values slightly deviated from experimental data. The quadratic model curves are shown in Figure 2 with selected process variables (pH, reaction time, dosage of zero-valent iron powder) kept at a constant level and the other two varying with the experimental ranges.

Predicted response vs. actual response.

The response surface diagram of the impact of pH, reaction time and dosage of zero-valent iron on uranium removal efficiency.

This method with the maximum U-removal efficiency of 99.66, has shown high effect on uranium removal, occurring from 2772.23 μg/L uranium plant wastewater within 0.40-0.80 g dosage of zero valent of iron powder, the 30-75 min reaction time, for wastewater with pH 3-7.

As Figure 2 shown, firstly, the uranium removal efficiency increased gradually with increasing pH value and then became decreasing sharply when pH value reaching to 5. The experiments results indicated that mildly acidic pH (pH 3-5) was suitable for the removal of uranium. In the weak acid, uranium exists as UO22+ which was easy to be reduced by zero valent iron to produce uranyl hydroxide precipitation by hydrolysis for higher uranium removal efficiency. But because of amphoteric properties of uranyl hydroxide, where the pH is close to neutral or alkaline, uranyl hydroxide precipitation would transfer to the form of UO42- and U2O72- plasma. In the alkaline solution, uranium can inhibit the reduction and precipitation of uranium by zero valent iron. The uranium is returned to the solution that leads to the uranium removal efficiency decreased sharply. Secondly, with the extension of reaction time, the effect of uranium removal becomes better, and then after 52.5 min is steady. That because with the longer reaction time, the contact chance of zero valent iron and uranium (VI) is better, which would promote the combination with iron hydroxide flocculation body and uranium acyl. Better combination of flocs of iron hydroxide and uranium acyl would be positive to uranium removal. When the reaction reaches equilibrium, the longer reaction time has no effect on the reaction of uranium removal. Longer reaction time makes no difference on the removal of uranium. Thirdly, with increase of dosage of iron powder, the effect of uranium removal becomes better, and then over excess of 0.6 g is steady. More iron powder dosage, more uranium removal. When the content of uranium in the wastewater is low enough, removing uranium reaction would stop. Therefore, more iron powder has no effect on uranium removal reaction. As Table 1 and Figure 2 shown, the maximum uranium removal efficiency of 99.66% was obtained in the optimum condition. The optimum conditions are pH of 5, dosage of zero valent iron of 0.6 g, reaction time of 52.5 min. The experiment verified the accuracy of the mathematical model generated by the RSM design when only 0.65% residual error was left in the given optimal medium setting. The optimized process parameters were shown in Table 3.

Predicted value vs. validation experiment value.

| pH A | Reaction time | Dosage of zero-valent of | Uranium removal efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (min) | iron C (g) | Predicted value | Experiment value | |

| 5 | 52.5 | 0.6 | 98.79 | 99.44 |

4 Conclusions

Nitric acid was replaced by extraction raffinate for pH adjustment in the process, which is not only have a good result on uranium removal, but also enhancing resources comprehensive utilization.

It is an effective method to remove uranium from uranium plant wastewater by using zero valent powder. The maximum removal rate of uranium was 99.66% occurring from 2772.23 μg/L uranium plant wastewater with 0.6 g dosage of zero valent of iron powder, 52.5 min reaction time, for wastewater with pH 5.

The maximum removal efficiency of uranium obtained in optimum condition was 98.79%, which is good agreement with experiment one of 99.44% with 0.65% residual.

Acknowledgments

All the Authors are grateful for the Yunnan Provincial Science and technology key project (NO. 2017FA026), financial supports by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51404115), Kunming Key Laboratory of Special Metallurgy, and Academician Workstation of Advanced Preparation of Superhard Materials Field.

References

[1] Xie Y., Chen C.L., Ren X.M., Wang X.X., Wang H.Y., Wang X.K., Emerging natural and tailored materials for uranium-contaminated water treatment and environmental remediation. Prog. Mater. Sci., 2019, 103, 180-234.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Choudhary S., Sar P., Characterization of a metal resistant Pseudomonas sp. isolated from uranium mine for its potential in heavy metal (Ni2+ Co2+ Cu2+ and Cd2+ sequestration. Bioresource Technol., 2009, 100, 2482-2492.10.1016/j.biortech.2008.12.015Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Pereira W.D., Kelecom A.G.A.C., da Silva A.X., do Carmo A.S., Py D.D., Assessment of uranium release to the environment from a disabled uranium mine in Brazil. J. Environ. Radioactiv., 2018, 188, 18-22.10.1016/j.jenvrad.2017.11.012Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Torkabad M.G., Keshtkar A.R., Safdari S.J., Selective concentration of uranium from bioleach liquor of low-grade uranium ore by nanofiltration process. Hydrometallurgy, 2018, 178, 106-115.10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.04.012Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kazy S.K., D’Souza S.F., Sar P., Uranium and thorium sequestration by a Pseudomonas sp.: mechanism and chemical characterization. J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 163, 65-72.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.076Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Omidi M.H., Azad F.N., Ghaedi M., Asfaram A., Azqhandi M.H.A., Tayebi L., Synthesis and characterization of Au-NPs supported on carbon nanotubes: Application for the ultrasound assisted removal of radioactive UO22+ ions following complexation with Arsenazo III: Spectrophotometric detection, optimization, isotherm and kinetic study. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci., 2017, 504, 68-77.10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.022Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Zou W., Zhao L., Han R., Removal of Uranium (VI) by Fixed Bed Ion-exchange Column Using Natural Zeolite Coated with Manganese Oxide. Chin. J. Chem. Eng., 2009, 17, 585-593.10.1016/S1004-9541(08)60248-7Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Han R., Zou W., Wang Y., Zhu L., Removal of uranium (VI) from aqueous solutions by manganese oxide coated zeolite: discussion of adsorption isotherms and pH effect. J. Environ. Radioactiv., 2007, 93, 127-143.10.1016/j.jenvrad.2006.12.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Noubactep C., Schöner A., Meinrath G., Mechanism of uranium removal from the aqueous solution by elemental iron. J. Hazard. Mater., 2006, B132, 202-212.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.08.047Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Regulations for radiation protection for uranium processing and fuel fabrication facility. EJ1056-2005, China Commission of Science Technology and Industry for National Defense, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Taghipour T., Karimipour G., Ghaedi M., Asfaram A., Mild synthesis of a Zn(II) metal organic polymer and its hybrid with activated carbon: Application as antibacterial agent and in water treatment by using sonochemistry: Optimization, kinetic and isotherm study. Ultrason. Sonochem., 2018, 41, 389-396.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.09.056Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Asghar A., Abdul Raman A.A., Daud W.M., A comparison of central composite design and Taguchi method for optimizing Fenton process. Sci. World J., 2014, 4, 1-14.10.1155/2014/869120Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Asfaram A., Ghaedi M., Dashtian K., Ghezelbash G.R., Preparation and Characterization of Mn0.4Zn0.6Fe2O4 Nanoparticles Supported on Dead Cells of Yarrowia lipolytica as a Novel and Efficient Adsorbent/Biosorbent Composite for the Removal of Azo Food Dyes: Central Composite Design Optimization Study. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., 2018, 6, 4549-4563.10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03205Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Dastkhoon M., Ghaedi M., Asfaram A., Goudarzi A., Mohammadi S.M., Wang S.B., Improved adsorption performance of nanostructured composite by ultrasonic wave: Optimization through response surface methodology, isotherm and kinetic studies. Ultrason. Sonochem., 2017, 37, 94-105.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.11.025Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Ma L., Han Y., Sun K., Lu J., Ding J., Optimization of acidified oil esterification catalyzed by sulfonated cation exchange resin using response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manage., 2015, 98, 46-53.10.1016/j.enconman.2015.03.092Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bezerra M.A., Santelli R.E., Oliveira E.P., Villar L.S., Escaleir L.A., Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta, 2008, 76, 965-977.10.1016/j.talanta.2008.05.019Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Awad O.I., Mamata R., Alic O.M., Azmia W.H., Kadirgamaa K., Yusria I.M., et al., Response surface methodology (RSM) based multi-objective optimization of fusel oil-gasoline blends at different water content in SI engine. Energ. Convers. Manage., 2017, 150, 222-241.10.1016/j.enconman.2017.07.047Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Fernandez C., Verné E., Vogel J., Carl G., Optimisation of the synthesis of glass-ceramic matrix biocomposites by the “response surface methodology”. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 2003, 23, 1031-1038.10.1016/S0955-2219(02)00264-9Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Camacho L.M., Deng S.G., Parra R.R., Uranium removal from groundwater by natural clinoptilolite zeolite: Effects of pH and initial feed concentration. J. Hazard. Mater., 2010, 175, 393-398.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Dickinson M., Scott T.B., The application of zero-valent iron nanoparticles for the remediation of a uranium-contaminated waste effluent. J. Hazard. Mater., 2010, 178, 171-179.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.01.060Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Integrated Wastewater discharge Standard, GB8798-1996, National standard of the People’s Republic of China, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Verma P., Agrawal U.S., Sharma A.K., Sarkar B.C., Sharma H.K., Optimization of process parameters for the development of a cheese analogue from pigeon pea Cajanus cajan and soy milk using response surface methodology. Int. J. Dairy Technol., 2005, 58, 51-58.10.1111/j.1471-0307.2005.00182.xSuche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Luo et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering