Abstract

Moringa oleifera oil (MOO), a second-generation lipid feedstock that has been reckoned as a promising feedstock for biodiesel production in recent years. In the current study, crude MOO possessing high acid value (80.5 mg of KOH/g) was subjected to two step esterification and transesterification process for biodiesel production and the process was applied with central composite design (CCD) based response surface methodology (RSM). The results showed that H2SO4 concentration of 0.85 vol%, reaction time of 70.20 min, and methanol to oil ratio of 1:1 (vol/vol) significantly decreased the acid value to 3.10 mg of KOH/g of oil. Moreover, copper oxide-calcium oxide (CuO-CaO) nanoparticles were developed and evaluated as a novel heterogeneous base catalyst for synthesizing Moringa oleifera methyl esters (MOME). The synthesized catalyst was scrutinized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDAX) analysis. Copper oxide (CuO) was perceived to be the dominant phase in the synthesized catalyst. Highest MOME conversion of 95.24% was achieved using 4 wt% CuO-CaO loading, 0.3:1 (vol/vol) methanol to oil ratio and 150 min reaction time as the optimal process conditions.

1 Introduction

The dominance of fossil fuel is escalating over few decades owing to its prominent combustion efficacy, fuel compliance, reliability, availability and handling attributes [1]. Of total primary energy consumption in 2016, crude oil contributes a major share of 33.3% followed by coal (28.11%) and natural gas (24.1%). Despite having a share of around 4%, renewable energy including biofuels was reported to be the fastest growing energy source in 2016 [2]. Also, researchers started to focus on developing various types of alternative energy sources since the emanations generated by the burning of fossil fuels has an adverse impact on both ecosystem and human health. Biodiesel is one such alternate fuel energy which can be employed in diesel engines [3]. It is simply the fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) derived from vegetable oils, animal fats and waste cooking oils in the occurrence of short chain alcohols with a suitable catalyst via chemical route known as transesterification. Furthermore, it has numerous benefits such as biodegradability, lower emission of oxides of carbon and sulphur and also leaves no particulate matter.

Homogeneous and heterogeneous are two types of catalyst generally used for biodiesel production. Homogeneous catalysts are widely used for conventional industrial process due to faster reaction rate, higher yield, and mild reaction conditions [4,5]. Besides several advantages, the major restriction relies on non-environmental friendly process due to the generation of excess waste water during washing of biodiesel. Moreover, the produced biodiesel needs purification inorder to remove the homogeneous basic catalyst which makes the process expensive and time devouring. To surmount the above said drawbacks, the heterogeneous catalyst has been explored widely [6]. Heterogeneous catalysts are gaining importance since it can be rapidly separated via naive filtration technique thereby reducing process time and cost required for purification of final product [7]. Also, the separated catalyst is less corrosive, environmental friendly, and by filtration can be reused in subsequent reactions.

Use of metal oxide nanoparticles as heterogeneous catalysts is on the rise owing to their high reactivity, stability, and reusability. Amongst the various metal oxides, copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NP) are more suitable as they are less expensive than gold or silver nanoparticles [8]. Synthesizing metallic copper nanoparticles is quite challenging owing to its easily oxidizing nature and it may be considered as a major limitation. For CuO-NP production, several techniques are available such as chemical reduction, thermal disintegration, microwave assisted decomposition, polyol synthesis and even by simple precipitation method as copper salts can be easily reduced using mild reducing agents like ascorbic acid [9]. In addition, copper nanoparticles can be produced via size controlled methods which can be used to study the optimum size of nanoparticles for maximizing the yield and conversion of biodiesel [10]. Owing to its advantages such as availability of various production techniques, and virtuous thermodynamic stability holding, metal oxide makes CuO-NP more promising for application in biodiesel production.

Doping is the addition of various compounds so as to increase the catalytic activity of the existing material. Several reports are available indicating the doping of CuO-NP with different materials to bring about enhanced or novel properties [11, 12, 13]. Calcium oxide based catalysts have also been extensively employed owing to its availability, lower toxicity, high basicity and high transesterification activity [14]. To make the biodiesel process highly economical and eco-friendly, the calcium-based catalysts synthesized from waste materials such as animal bones, fish bones, sea shells, and egg shells are of recent research interest. Previously, several mixed metal oxide based heterogeneous catalyst were synthesized using doping or wet impregnation techniques and tested successfully for biodiesel production [15, 16, 17, 18].

Furthermore, a major predicament allied with biodiesel production is lipidic feedstock availability. The exploitation of conventional source has some limitations owing to its food vs. fuel dilemma. Alternative feedstocks such as non-edible sources have acquired worldwide consideration for biodiesel production [19, 20, 21]. Among various non-edible feedstocks, Moringa oleifera (drumstick tree) belongs to the family Moringaceae is a multipurpose small deciduous and most widely cultivated tree found mainly in tropical and subtropical regions. The tree bears triangular shaped seeds which contain 35-45% oil by weight [22]. M. oleifera based biodiesel is proved to be more stable due to the oil’s inherent antioxidant property. Owing to this, prolonged biodiesel storage is made viable [23]. Several works on the utilization of M. oleifera oil (MOO) as a viable source for the production of biodiesel were reported in literature. However, a few reports are available with respect to heterogeneous catalyst based biodiesel production from M. oleifera oil [20,24, 25]. Also, there is no report on statistical optimization of esterification reaction using M. oleifera oil as feedstock.

In the current work, central composite design (CCD) based response surface methodology (RSM) was employed to reveal the optimal level of process parameters for the sulfuric acid based esterification reaction to reduce the acid value of crude M. oleifera oil followed by the mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production. The interaction between esterification variables such as catalyst concentration, methanol to oil volumetric ratio and reaction time on acid value reduction were examined. Moreover, methyl ester synthesis from M. oleifera oil via copper oxide doped with calcium oxide as a mixed metal oxide catalyst was investigated. In this technique, calcium oxide provides high conversion of the feedstock to biodiesel, whereas copper oxide provides high stability and high specific surface area for reaction. The CuO-NP was synthesized using precipitation method and were further doped with calcium oxide obtained by the calcination of powdered conch shell. The resulting catalyst was examined using FTIR, XRD, SEM and EDAX techniques. Further, the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst was utilized for biodiesel synthesis from esterified MOO and the transesterification variables such as catalyst concentration, methanol to esterified oil ratio and reaction time on MOME conversion were optimized using CCD of RSM.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Crude MOO employed in the current research work was procured from Tamil Traders, Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu), Conch shells (CS) were obtained from the Kanyakumari seashore, Tamil Nadu, India. The initial moisture content of crude MOO was found to be 0.12% and hence, it was preheated at 105°C for 4 h to remove the residual moisture present. Typical titration method was employed to determine the crude MOO’s acid value [26]. Phenolphthalein indicator, methanol, and ethanol were purchased from S.D. Fine Chemicals Ltd, Mumbai, India while copper acetate monohydrate salt, sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, sulfuric acid (98%), and petroleum ether (40-60°C) was obtained from HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai. Analytical grade reagents, solvents and chemicals only utilized in this study.

2.2 Preparation of CuO-CaO catalyst

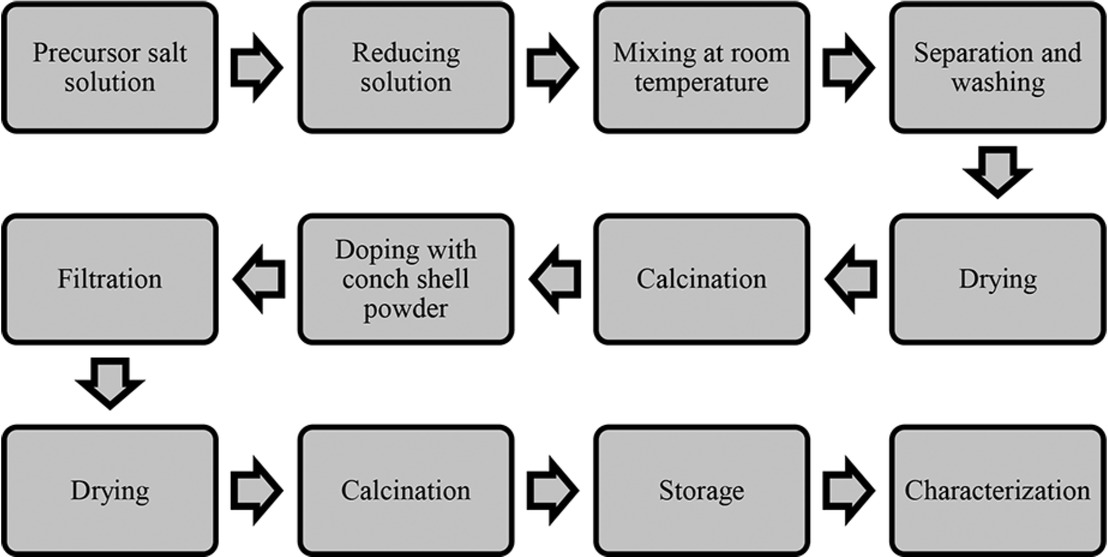

Sodium hydroxide (0.2 M) solution was added to copper acetate (0.2 M) solution at 1:3 ratio respectively at 2 mL/min flow rate under constant stirring (250 rpm) for 4 h till the solution turned completely black. The nanoparticles were then obtained by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min and were repeatedly cleansed with ethanol and de-ionized water to eliminate any traces of impurities. The collected precipitate was calcined at 600°C for 3 h to completely eradicate any moisture. Conversely, conch shells (CS) was initially washed with water several times continued by drying (105°C – 24 h) and then size reduced into fine powder. The powdered CS was calcined at 900°C for 3 h in a programmable muffle furnace. Doping of catalyst was done by adding the synthesized CuO-NP and calcined CS powder (1:1 ratio) to 50 mL of de-ionized water and stirred at 40°C for 6 h. The mixture was poured onto a Whatman No.1 filter paper and the retentate was calcined at 600°C for 3 h to eliminate all traces of moisture [27,28]. The overall schematic of catalyst synthesis was presented in Figure 1.

Flow chart for catalyst synthesis.

2.3 Catalyst characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis using CARL ZEISS (Model: SIGMA V) was utilized to analyze the surface morphology of the CuO-NP and the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst. Energy dispersive atomic X-ray spectrometry (EDAX) was implemented to reveal the elemental constituents of the CuO-NP and the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy using ATR-FTIR (Model: BRUKER, Germany) in the scan range of 4000-600 cm-1 was done to analyze functional groups present in the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using PANalytical X’Pert3 powder diffractometer equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (K-Alpha = 1.54Å) at the rate of 30 mA and 45 kV was employed in order to obtain diffraction patterns in the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst in the scanning angle ranging from 2θ° = 10.00 to 89.99, step size of 0.0130, step time of 48.19 s.

2.4 Sulfuric acid catalyzed esterification reaction

The process was conducted in 250 mL three-necked glass reactor rested in a stable temperature water bath. All the experimentations were carried out using crude MOO. Based on earlier studies, the stirrer speed and reaction temperature were maintained at 450 rpm and 60°C, respectively [20]. The volume of sulfuric acid, methanol to oil volumetric ratio and esterification time were varied based on design matrix to obtain the minimum acid value. After accomplishment of reaction, the mixture was heated to remove the surplus methanol. Furthermore, the resulting mixture was poured into separating funnel and kept uninterrupted for overnight for clear partition. The lowest layer comprising impurities were drained off and the top layer of esterified oil was removed and hoarded for further studies and used for transesterification process.

2.5 CuO-CaO catalyzed transesterification reaction

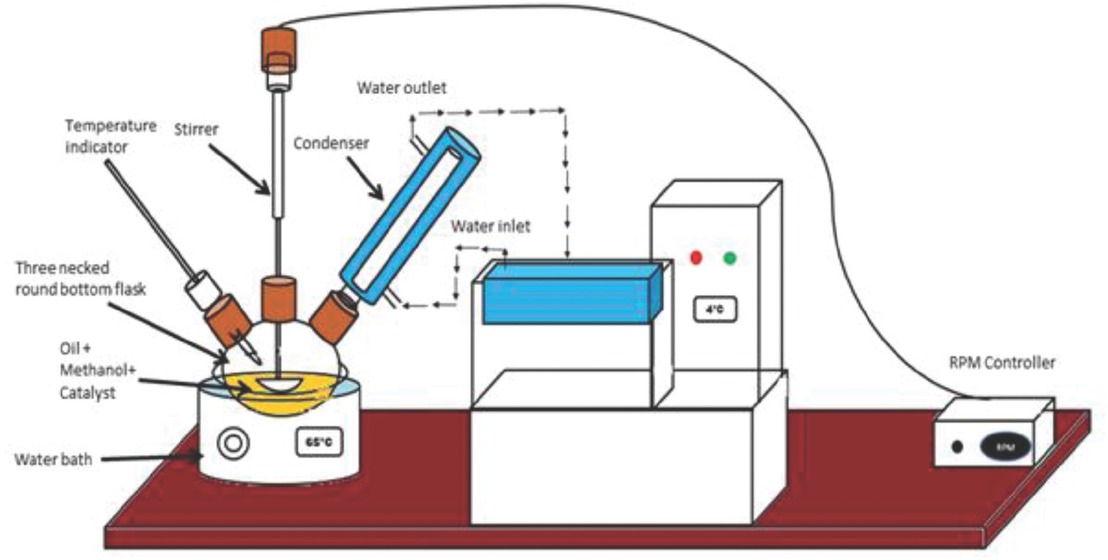

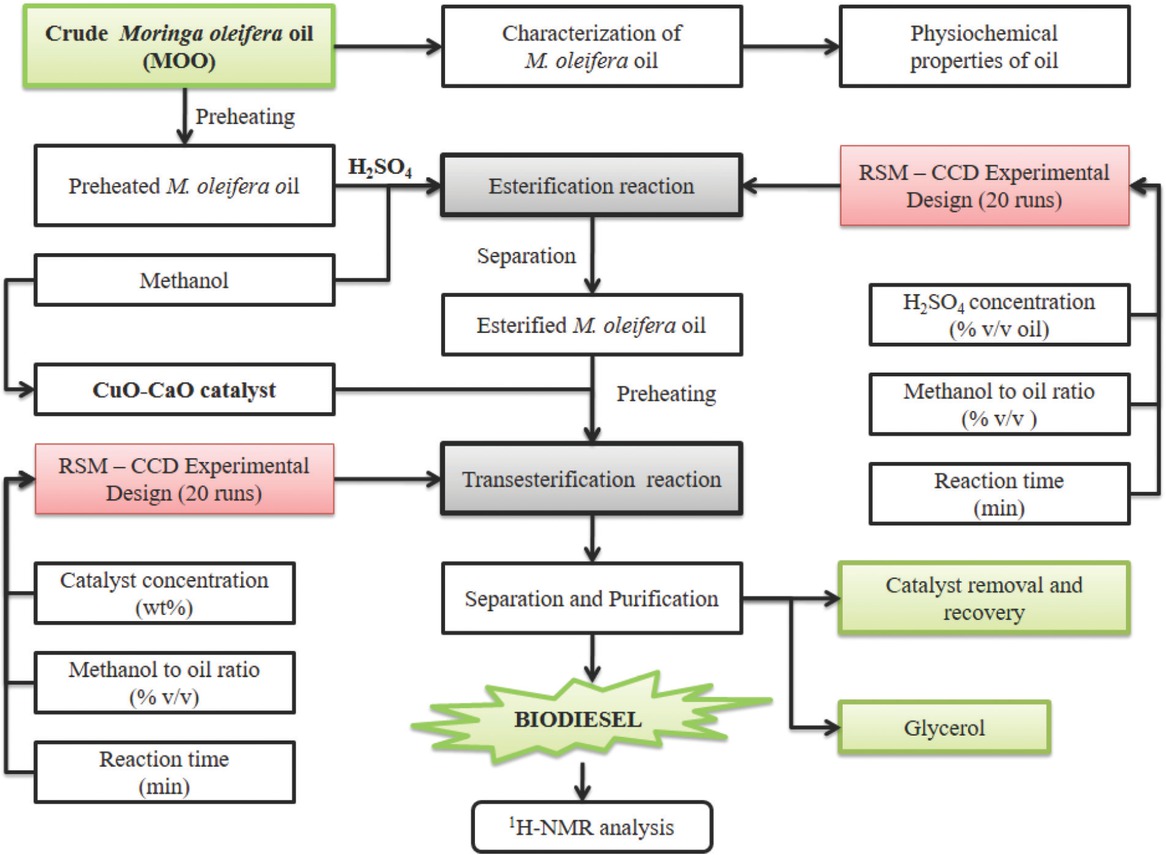

Figure 2 represents the experimental setup employed in transesterification reaction. Based on several preliminary studies, base-catalyzed transesterification reaction was executed in glass reactor by utilizing the synthesized CuO-CaO based catalyst with methanol as solvent. Initially, calculated amount of methanol was added to the desired amount of synthesized catalyst as provided in the design matrix and the mixture was stirred to enhance the methoxide formation. The preheated esterified MOO was then added to the reaction mixture maintained at 65°C with stirrer speed of 450 rpm [20]. After the reaction was completed, the resultant mixture was heated to evaporate additional methanol and then transferred to a separating funnel containing No.1 Whatmann filter paper to cut-off the solid catalyst, followed by the overnight estrangement for the distinct phase partition of M. oleifera methyl esters (top) and glycerol (bottom). Glycerol was eliminated while the biodiesel was stored in an air tight container for further assessment. The overall schematic workflow for M. oleifera oil based biodiesel synthesis was presented in Figure 3. The M. oleifera methyl esters (MOME) conversion was determined by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-NMR) in which CDCl3 was used as solvent. The percentage methyl ester conversion was determined using Eq. 1 [29].

Experimental setup for transesterification reaction.

Overall scheme of biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil.

where, C denotes percentage conversion of triglycerides to methyl esters, AME signifies integration value of methoxy protons of methyl esters,

2.6 Design of experiment

RSM using five levels based three factorial CCD was employed to analyze the effect of three independent variables on both esterification and transesterification process [30]. H2SO4 concentration (0.5-1 vol%), methanol to oil volumetric ratio (1:1-1:3 vol/ vol), and reaction time (30-90 min) are the independent variables selected for the esterification of crude MOO whereas for the CuO-CaO based transesterification, the independent variables such as CuO-CaO catalyst concentration (2-4 wt%), methanol to oil volumetric ratio (0.3-0.7 vol/ vol), and reaction time (90-150 min) were opted. The range and the levels of process variables for esterification and transesterification process were shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Range and levels of independent variables used for acid esterification process.

| Variables | Symbols | Units | Variable levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -α | -1 | 0 | +1 | +α | |||

| H2SO4 concentration | A | vol% | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.17 |

| Methanol to oil ratio | B | (vol/vol) | 1:0.32 | 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 | 1:3.68 |

| Reaction time | C | min | 9.55 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 110.45 |

Range and levels of independent variables used for CuO-CaO based transesterification process.

| Variables | Symbols | Units | Variable levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -α | -1 | 0 | +1 | +α | |||

| CuO-CaO concentration | A | wt% | 1.32 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4.68 |

| Methanol to esterified oil ratio | B | (vol/vol) | 0.16:1 | 0.3:1 | 0.5:1 | 0.7:1 | 0.84:1 |

| Reaction time | C | min | 69.55 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 170.45 |

2.7 Statistical analysis

Design Expert (Version 11 Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, USA) software was used to optimize the esterification and transesterification experiments for estimating the effect of parameters on the response. All the runs in esterification and transesterification processes were analyzed individually to fit the developed model by using the regression analysis and also assessment of the equation for statistical significance. The quality of fit of the predicted model was estimated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance test. By analyzing the response plots and reviewing the regression equation, the optimal conditions for the selected parameters was achieved. Several terms including correlation coefficient (R), coefficient of determination (R2), Fisher’s test (F-value), and probability value (p-value) were analyzed for envisaging the response. Equation 2 represents the second order polynomial equation.

where, Y is the predicted response (acid value reduction and/or biodiesel conversion), b0 – coefficient constant, ba – linear coefficients, baj – interaction coefficients, baa – quadratic coefficients and xa, xj symbolizes the coded values of the experimental variables. A residual analysis which is the divergence among the experimental values and the predicted values was performed to validate the regression model and the values should lie diagonally in the normal probability graph.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Physiochemical properties of Moringa oleifera oil

The physiochemical property of crude MOO used in the present study was analyzed and the observations were given in Table 3. The maximum acid value of MOO reported in the literature was 8.62 g of KOH/g of oil [22,31, 32]. However, the acid value of MOO used in the present study exhibits a very high acid value of 80.50 g of KOH/g oil. The existence of high acid value may be attributed to the crude nature of oil and the extraction technique (mechanical screw press) employed by the supplier. Also, the density of crude MOO was found to be higher used in the present work than the previously reported studies. Similar observations of high free fatty acid content for different non-edible feedstocks such as Hevea brasiliensis oil [33], Madhuca indica [34], Jatropha curcas [35], and Pongamia pinnata [36] were reported in the literature. The difference in the values of physiochemical properties of MOO can be attributed to the plant growth conditions, employed oil extraction technique, fatty acid composition, analysis temperature, and analysis procedure involved.

Comparison of physiochemical properties of MOO used in the present work with the state of art in the literature.

| Properties | [25] | [22] | [31] | [32] | [37] | [38] | [39] | [40,41] | [42] | [43] | [44] | [45] | [46] | Present work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic viscosity (mPa s) at 40°C | -1 | 38.905 | 38.90 | -1 | 92.63,8 | -1 | -1 | 38.99 | 29.003 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 45.888 |

| Acid value(mg of KOH/g) | 2.2 | 8.62 | 8.62 | 8.62 | 1.194 | 4.06 | 0.97 | 8.627 | 0.867 | 3.2 | 13.2 | 0.012 | 3.8-5.04 | 80.50 |

| Free fatty acid (FFA) (%) | 1.1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 0.6 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 6.678 | 0.5-2.51 | 40.25 |

| Saponification value (mg KOH/g) | 192.3 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 192.3 | -1 | 182.48 | -1 | -1 | 172.3 | 179 | -1 | 171.9-191 | 191.88 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 914.4 | 897.5 | 897.50 | 897.5 | 907.0 | 9123 | -1 | 897.14 | 923.42 & 906.34 | -1 | -1 | 876.7 | 903.7 | 9924 |

-1 -= not reported

-2 -= analysis done at 15°C

-3 -= analysis done at 20°C

-4 -= analysis done at 40°C

-5 -= temperature of particular analysis was not reported

-6 -= reported as oleic acid (%)

-7 -= value reported in article [41]

-8 -= reported in unit (cP)

3.2 Catalyst characterization

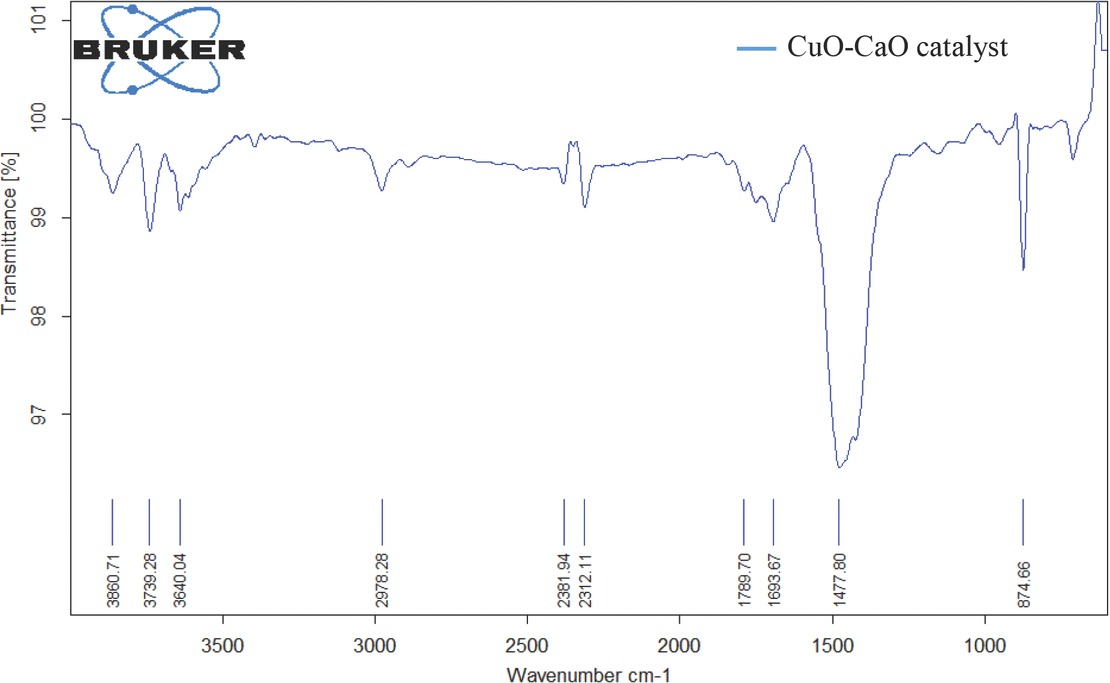

3.2.1 FTIR analysis

The infrared spectrum of synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst was shown in Figure 4. The low intensity absorption band at 3640.04 cm-1 was ascribed to the presence of hydroxyl (–OH) group in Ca(OH)2 formed owing to the association of active catalyst to the air during analysis procedure [47]. Major absorption band observed at 874.66 cm-1 and minimal absorption band at 2312.11 cm-1 was assigned to vibrational mode (out of plane bend) for

FTIR spectrum of CuO-CaO catalyst.

3.2.2 XRD analysis

XRD pattern of the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst was illustrated in Figure 5. The peaks observed at 32.51°, 35.50°, 38.74°, 46.27°, 48.73°, 53.49°, 58.31°, 61.55°, 65.83°, 66.23°, 68.06°, 72.40°, 75.02° and 80.20° represents the presence of monoclinic CuO-NP and are in agreement with the reported diffraction peaks [8,51, 54, 55, 56, 57]. Also, peaks corresponding to CaO were observed at 54.12° and 64.32° which indicates successful doping [58]. The average size of the doped particles was estimated using equation given by Debye-Scherer [59] and was found to be 37.54 nm. Minor peaks of hexagonal shaped portlandite (Ca(OH)2) were observed at 17.99°, 28.67°, 34.08°, 50.80°, 59.30° and 62.62° which can be attributed to the exposure of the calcined catalyst with atmospheric air before analysis. Peaks at 23.03°, 29.36°, and 43.17° indicates the presence of rhombohedral shaped CaCO3 species [60]. The observed

XRD pattern of CuO-CaO catalyst.

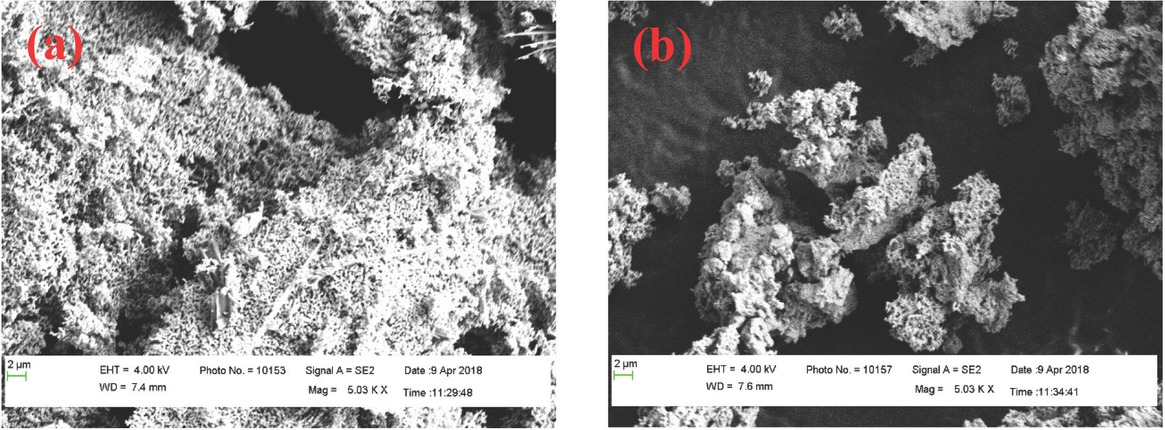

3.2.3 SEM analysis

The surface morphology of CuO-NP and CuO-CaO catalyst was shown in Figure 6. No defined shape was observed on the CuO-NP (Figure 6a) while the CuO-CaO appears as agglomerates (Figure 6b). The CuO-NP shows high porosity on its surface which facilitates the attachment of CaO thereby enhances the catalytic activity. Baskar et al observed that the synthesized manganese doped ZnO was spherical shaped and appeared in cluster form [15]. Madhuvilakku and Piraman observed the morphology of the synthesized mixed oxide (TiO2-ZnO) nanocatalyst by FE-SEM and reported that the catalysts appeared as aggregates. Also, the catalysts particles corresponding to ZnO formed agglomerated flakes while the complex TiO2-ZnO appeared in irregular spherical shapes [53]. No reports were available on doping of CuO-NPs with CaO. Hence, the current study focuses on the usage of doped nanocatalysts for biodiesel production.

SEM image of (a) CuO-NP and (b) CuO-CaO catalyst.

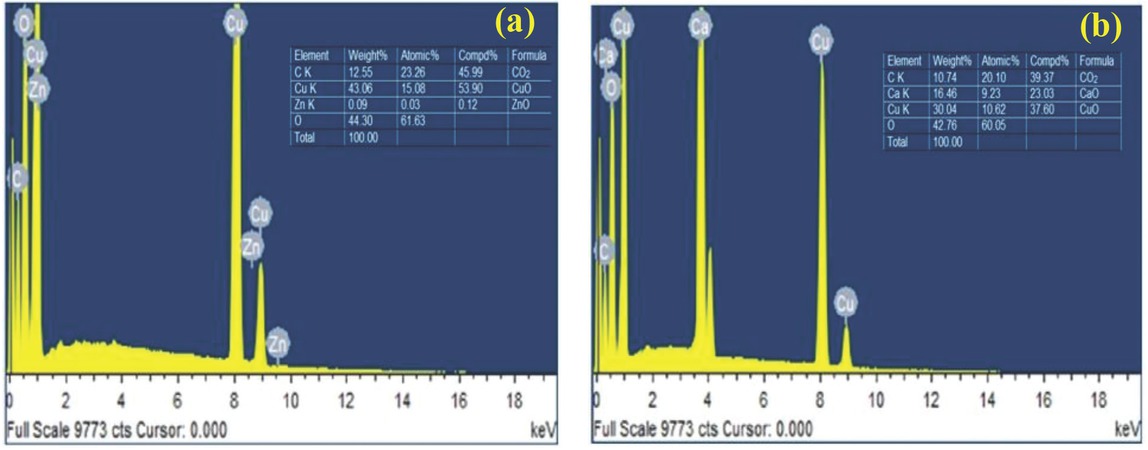

3.2.4 EDAX analysis

The chemical constituents of the synthesized CuO-NP displayed in Figure 7 was determined using EDAX analysis. The EDAX spectrum shown in Figure 7a revealed that copper (43.06 wt%) and oxygen (44.30 wt%) are the major elements. EDAX analysis on CuO-NP synthesized from Aloe vera leaf extract showed atomic percent of 45% and 54% for O and Cu, respectively [56] while the present study revealed a less amount of Cu (15%) and a high amount of O (61.6%). A negligible amount of zinc presence was observed in the EDAX spectrum which is attributed over the impurities being entered during the sample preparation for analysis. Moreover, a high carbon presence was observed due to the usage of carbon tape in which the samples are mounted during analysis procedures. Doping of CuO-NPs with CaO derived from conch shell was observed clearly from the EDAX spectrum shown in Figure 7b. 16.46 wt% of calcium was observed after doping of conch shell powder along with the CuO NP indicating the integration of CaO on CuO-NP. The major constituents of the synthesized catalyst were found to be copper (30.04 wt%), calcium (16.46 wt%) and oxygen (42.76 wt%).

EDAX spectrum of (a) CuO-NP and (b) CuO-CaO catalyst

3.3 RSM optimization of esterification and transesterification reaction

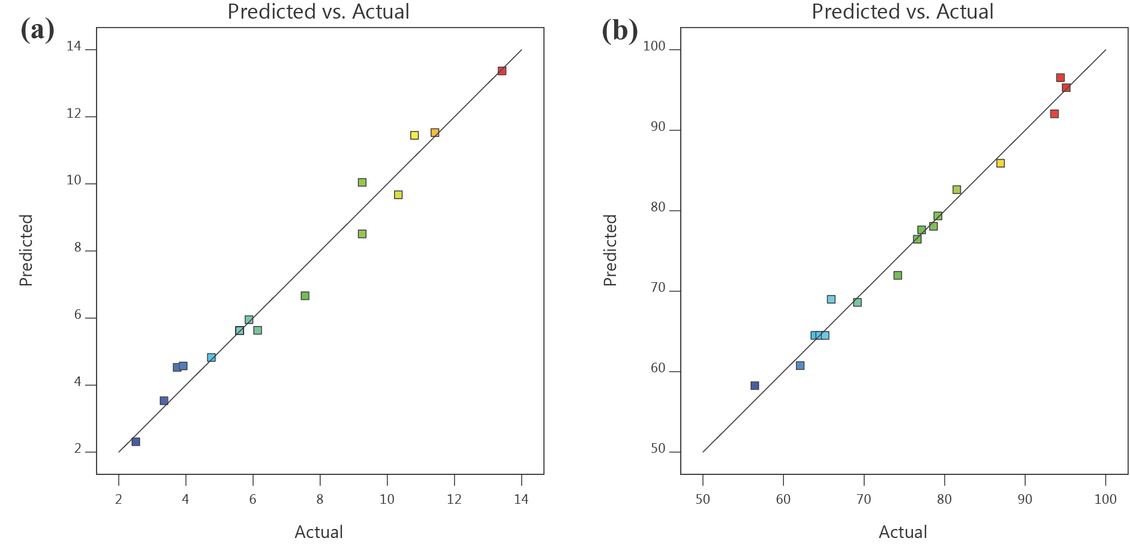

Experimental runs based on the CCD matrix were carried out to evaluate the response with respect to three independent variables for both the sulfuric acid catalyzed esterification (Table 4) and CuO-CaO catalyzed transesterification (Table 5) reaction. Statistical analysis was done using Design-Expert software package and the esterification-transesterification experimental optimization was carried out by analysis of variance (ANOVA). From ANOVA table presented in Table 6 and Table 7, it was evident that the model was statistically influential at 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05). The model’s probability of error (p-value < 0.05) represents that only a 5% likelihood that F-value of model might arise because of noise. The model terms (A, B, C) of esterification and transesterification are also statistically significant since the p-value is < 0.05. Additionally, methanol to oil ratio (B) in esterification and reaction time (C) in transesterification are the most influencing parameters owing to its greater F value and smaller p-value. Also, the fitness of model was evaluated by coefficient of determination (R2) and the corresponding value was 97.51% and 98.68% while the adjusted R2 was observed as 95.27% and 96.99% for esterification and transesterification, respectively. Graph of experimental results obtained was compared with the model predictions for esterification and transesterification are presented in Figure 8. It was perceived that experimental data are in high association with model predictions and exhibits a good agreement since the response values lies near diagonal line. The generated polynomial equation for esterification (Eq. 3) and transesterification (Eq. 4) reaction in coded factors was displayed below.

Predicted Vs Actual Values (a) H2SO4 catalyzed esterification and (b) CuO-CaO catalyzed transesterification.

CCD matrix for esterification reaction.

| Run | A: Catalyst concentration (vol%) | B: Methanol to oil ratio (vol/vol) | C: Reaction time (min) | Experimental acid value (mg of KOH/g) | Predicted acid value (mg of KOH/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.75 | 0.32 | 60 | 2.52 | 2.30 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 30 | 13.43 | 13.36 |

| 3 | 0.75 | 2 | 110.45 | 3.93 | 4.56 |

| 4 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 5 | 0.75 | 2 | 9.55 | 9.26 | 8.50 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 3 | 90 | 10.34 | 9.67 |

| 7 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 8 | 1 | 3 | 90 | 5.89 | 5.94 |

| 9 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 10 | 0.5 | 1 | 30 | 4.77 | 4.81 |

| 11 | 0.75 | 3.68 | 60 | 11.43 | 11.52 |

| 12 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 13 | 0.5 | 1 | 90 | 6.15 | 5.62 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 3.75 | 4.52 |

| 15 | 1 | 3 | 30 | 10.82 | 11.44 |

| 16 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | 90 | 3.36 | 3.52 |

| 18 | 0.75 | 2 | 60 | 5.61 | 5.61 |

| 19 | 1.17 | 2 | 60 | 7.56 | 6.65 |

| 20 | 0.33 | 2 | 60 | 9.26 | 10.03 |

CCD matrix for transesterification reaction.

| Run | A:CuO-CaO concentration (wt%) | B: Methanol to oil ratio (vol/vol) | C: Reaction time (min) | Experimental biodiesel conversion (%) | Predicted biodiesel conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 0.7 | 150 | 81.56 | 82.58 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.3 | 150 | 95.14 | 95.24 |

| 3 | 3 | 0.5 | 120 | 64.53 | 64.46 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.5 | 120 | 65.22 | 64.46 |

| 5 | 4 | 0.3 | 90 | 93.68 | 92.00 |

| 6 | 4.68 | 0.5 | 120 | 79.21 | 79.31 |

| 7 | 3 | 0.16 | 120 | 94.42 | 96.49 |

| 8 | 2 | 0.3 | 90 | 74.23 | 71.92 |

| 9 | 4 | 0.7 | 90 | 69.22 | 68.57 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.3 | 150 | 78.66 | 78.02 |

| 11 | 1.32 | 0.5 | 120 | 56.49 | 58.22 |

| 12 | 3 | 0.5 | 120 | 63.95 | 64.46 |

| 13 | 2 | 0.7 | 150 | 77.19 | 77.58 |

| 14 | 3 | 0.84 | 120 | 76.65 | 76.41 |

| 15 | 3 | 0.5 | 69.55 | 65.98 | 68.94 |

| 16 | 2 | 0.7 | 90 | 62.11 | 60.72 |

| 17 | 3 | 0.5 | 170.45 | 86.99 | 85.85 |

ANOVA table for esterification reaction.

| Source | Sum of squares | Df | Mean square | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 164.13 | 9 | 18.24 | 43.52 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| A-Catalyst concentration | 13.80 | 1 | 13.80 | 32.94 | 0.0002 | |

| B-Methanol to oil ratio | 102.61 | 1 | 102.61 | 244.88 | < 0.0001 | |

| C-Reaction time | 18.73 | 1 | 18.73 | 44.70 | < 0.0001 | |

| AB | 1.32 | 1 | 1.32 | 3.15 | 0.1063 | |

| AC | 1.63 | 1 | 1.63 | 3.89 | 0.0769 | |

| BC | 10.15 | 1 | 10.15 | 24.22 | 0.0006 | |

| A2 | 13.43 | 1 | 13.43 | 32.04 | 0.0002 | |

| B2 | 3.02 | 1 | 3.02 | 7.21 | 0.0229 | |

| C2 | 1.51 | 1 | 1.51 | 3.60 | 0.0870 | |

| Residual | 4.19 | 10 | 0.4190 | |||

| Lack of fit | 4.19 | 5 | 0.8381 | |||

| Pure error | 0.0000 | 5 | 0.0000 | |||

| Cor total | 168.33 | 19 |

R2 – 0.9751; Adj. R2 – 0.9527; Pred. R2 – 0.8109

ANOVA table for transesterification reaction.

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2272.12 | 9 | 252.46 | 58.21 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| A-CuO-CaO concentration | 536.79 | 1 | 536.79 | 123.77 | < 0.0001 | |

| B-Methanol to oil ratio | 486.55 | 1 | 486.55 | 112.19 | < 0.0001 | |

| C-Reaction time | 345.03 | 1 | 345.03 | 79.56 | < 0.0001 | |

| AB | 74.73 | 1 | 74.73 | 17.23 | 0.0043 | |

| AC | 4.08 | 1 | 4.08 | 0.9397 | 0.3646 | |

| BC | 57.94 | 1 | 57.94 | 13.36 | 0.0081 | |

| A2 | 26.06 | 1 | 26.06 | 6.01 | 0.0440 | |

| B2 | 681.11 | 1 | 681.11 | 157.05 | < 0.0001 | |

| C2 | 235.77 | 1 | 235.77 | 54.37 | 0.0002 | |

| Residual | 30.36 | 7 | 4.34 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 29.55 | 5 | 5.91 | 14.62 | 0.0653 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.8085 | 2 | 0.4042 | |||

| Cor total | 2302.48 | 16 |

R2 – 0.9868; Adj. R2 – 0.9699; Pred. R2 – 0.9018

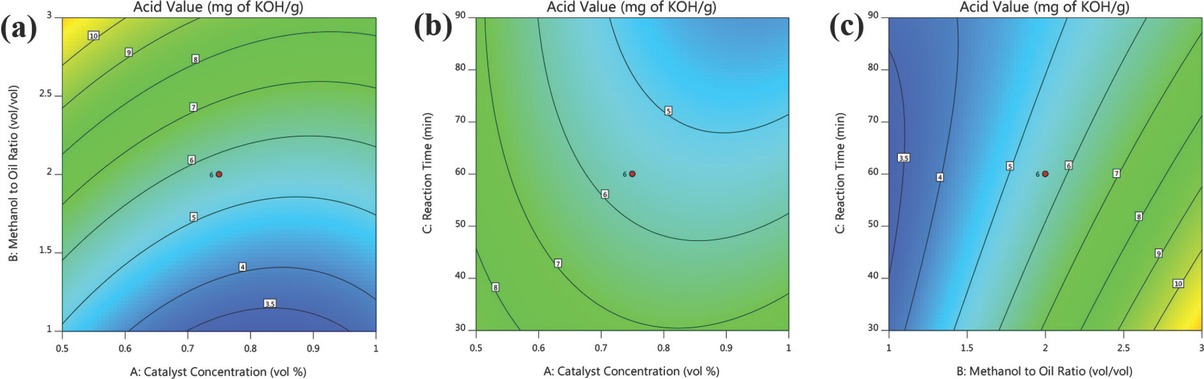

3.4 Interaction effect between esterification process variables

The influence of sulfuric acid concentration (A) and methanol to oil volumetric ratio (B) on the reduction of acid value is indicated in 2D contour plot (Figure 9a) generated by the software. Of three input variables, the reaction time was held at 60 min to study the influence between the parameters (A and B). Raising the sulfuric acid concentration up to 0.9 vol% with methanol to oil ratio at 1:1 ratio significantly increases acid value reduction. However, beyond 0.9 vol% of catalyst concentration, the acid value of crude MOO increases with methanol to oil volumetric ratio. Moreover, varying the methanol to oil volumetric ratio from 1:1 to 1:3 with increasing catalyst concentration, upsurge in the acid value was witnessed. Hence, the significant acid value reduction occurs over the catalyst concentration range of 0.7 to 0.9 with methanol to oil volumetric ratio at 1:1 at a constant reaction time of 60 min. However, volumetric ratio of 1:1 utilizes a higher volume of methanol which resulted in difficulties related to methanol separation thereby increasing the process cost. From ANOVA, it was perceived that the interrelation between sulfuric acid concentration (A) and methanol to oil volumetric ratio (B) are insignificant.

Interaction effects of esterification process variables.

Figure 9b shows the 2D contour plot among sulfuric acid concentration (A) and esterification time (C). The interaction between factor A and C was studied by holding methanol to oil volumetric ratio (B) constant at intermediate level (1:2). At low levels of both the parameters (A and C), the acid value of crude MOO remains higher and no substantial decline in acid value was noticed. At higher levels of factor A around 1 vol% and factor B around 90 min, a significant diminution in acid value was achieved with volumetric ratio of 1:2. From ANOVA, a less significant interaction among sulfuric acid concentration (A) and reaction time (C) was observed.

The effects of volumetric ratio (B) and esterification time (C) on lessening acid value is presented in 2D contour plots (Figure 9c) generated using CCD. The interaction effect of volumetric ratio (B) and esterification time (C) was investigated with a constant catalyst concentration of 0.75 vol%. Higher decline in acid value was witnessed with 1:1 volumetric ratio. However, varying the volumetric ratio from 1:1 to 1:3 ensued in improved acid value of crude MOO. This clearly indicates that higher amount of methanol is needed to solubilize the crude MOO for significant acid value diminution. At low level of reaction time, a significant reduction of acid value was observed with 1:1 methanol to oil ratio. It is also noticed that increase in reaction time exhibits an identical decrease in acid value as perceived in low levels. The acid value reduction among low and high levels of reaction time is almost same with 1:1 methanol to oil ratio. From ANOVA table, it is observed that the interaction effect of volumetric ratio (B) and reaction time (C) is significant.

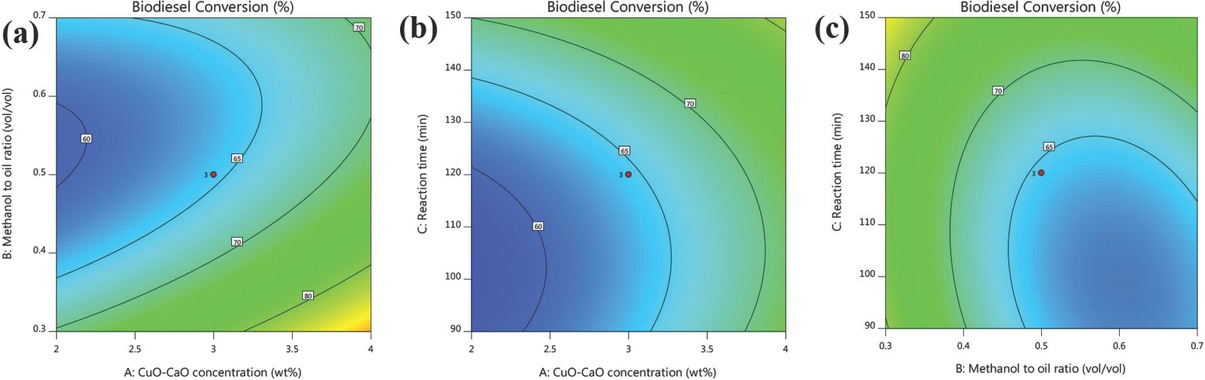

3.5 Interaction effect between transesterification process variables

Figure 10a shows the interaction effects between the transesterification parameters (CuO-CaO concentration and methanol to oil volumetric ratio) on biodiesel conversion while reaction time was held at middle level (120 min). The MOME conversion enhanced with rise in catalyst concentration and obtained a maximum conversion (< 85%) around 4 wt% owing to its huge availability of active catalytic sites. From the observed experimental results (Run. 2 and 5), high MOME conversion of < 90% was seen at lower volumetric ratio. However, lower MOME conversion was observed (Run. 1 and 9) at higher methanol to oil ratio which represents the dilution effect thereby leads to the existence of reverse reaction [47]. Furthermore, utilizing high volumes of methanol significantly increases the energy consumption for its removal at the end of the process [61]. Increasing the catalyst concentration beyond 4 wt% (Run. 6), drop in MOME conversion was witnessed which reflects the increased viscosity of reaction mixture.

Interaction effects of transesterification process variables.

The interaction effect between the variables CuO-CaO concentration and reaction time was presented in Figure 10b. From ANOVA table (Table 8), CuO-CaO loading was observed as highly influential parameter in MOME conversion due to minimal p-value (< 0.0001) and huge F-value (123.77). Low MOME conversion (= 60%) was observed at minimum reaction time (90 min) and lowest CuO-CaO loading (2 wt%) since the mass transfer between solid to liquid was slowly initiated. However, prolonging the reaction time enhances the MOME conversion which indicates well-established mass transfer among solid (catalyst) and liquid (methanol and oil). High MOME conversion around 80% achieved when time held at 150 min with CuO-CaO concentration of 4 wt%. Similar observation was reported using Turbo jourdani shells [62]. From the overall observations, it was evident that reaction time has the least contribution on the MOME conversion among other variables.

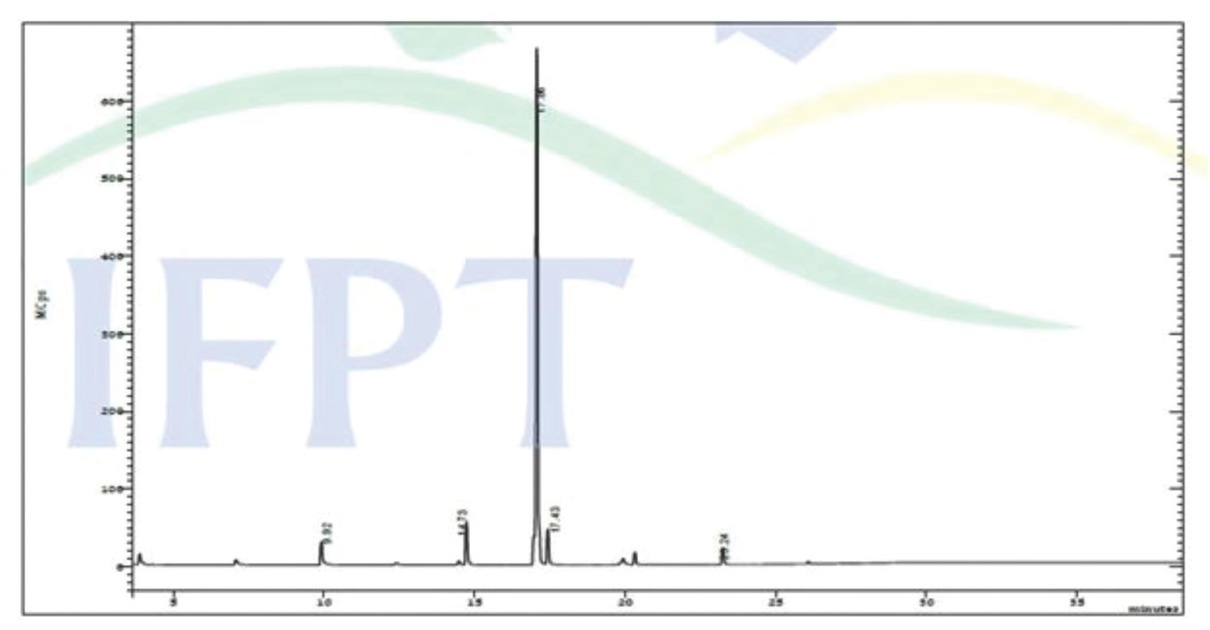

Fatty acid composition of synthesized MOME.

| S.No | RT | Name of the compound | Molecular formula | Molecular weight | Peak area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.88 | Octanoic acid, methyl ester | C9H18O2 | 158 | 1.76 |

| 2 | 7.07 | Decanoic acid, methyl ester | C11H22O2 | 186 | 0.90 |

| 3 | 9.92 | Undecanoic acid, methyl ester | C12H24O2 | 200 | 3.70 |

| 4 | 14.73 | Tridecanoic acid, methyl ester | C14H28O2 | 228 | 6.16 |

| 5 | 16.98 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester | C19H34O2 | 294 | 2.96 |

| 6 | 17.06 | 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester | C19H36O2 | 296 | 74.02 |

| 7 | 17.43 | Pentadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C16H32O2 | 256 | 5.14 |

| 8 | 20.33 | Methyl tetradecanoate | C15H30O2 | 242 | 2.89 |

| 9 | 23.24 | Nonadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C20H40O2 | 312 | 2.47 |

Figure 10c shows the 2D contour graph for the interaction between volumetric ratio and time at constant CuO-CaO concentration of 3 wt%. From the experimental results (Run. 7 and 14), the MOME conversion diminished with enhancing methanol to oil ratio which can be ascribed to the equilibrium shift (reverse reaction) during transesterification process owing to the presence of high methanol. It was also evident from the observations (Run. 15 and 17), increased reaction time enhanced the MOME conversion from 65.98% to 86.99%. From the contour plot shown in Figure 10c high MOME conversion of < 80% acquired at high reaction time (150 min) and low methanol to oil ratio (0.3:1 (v/v)) indicating the methanol was sufficient enough for the conversion. Similar results were observed on waste chicken eggshell based biodiesel production from soybean oil [63]. From ANOVA table, it was found that the interaction among methanol to oil ratio and reaction time was statistically noteworthy since the p-value < 0.05.

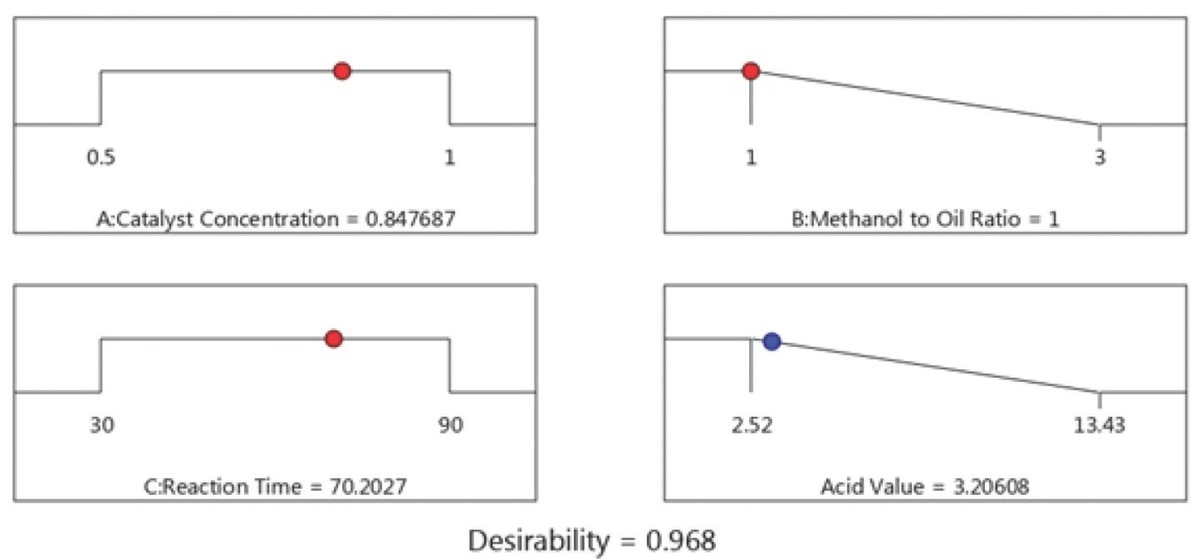

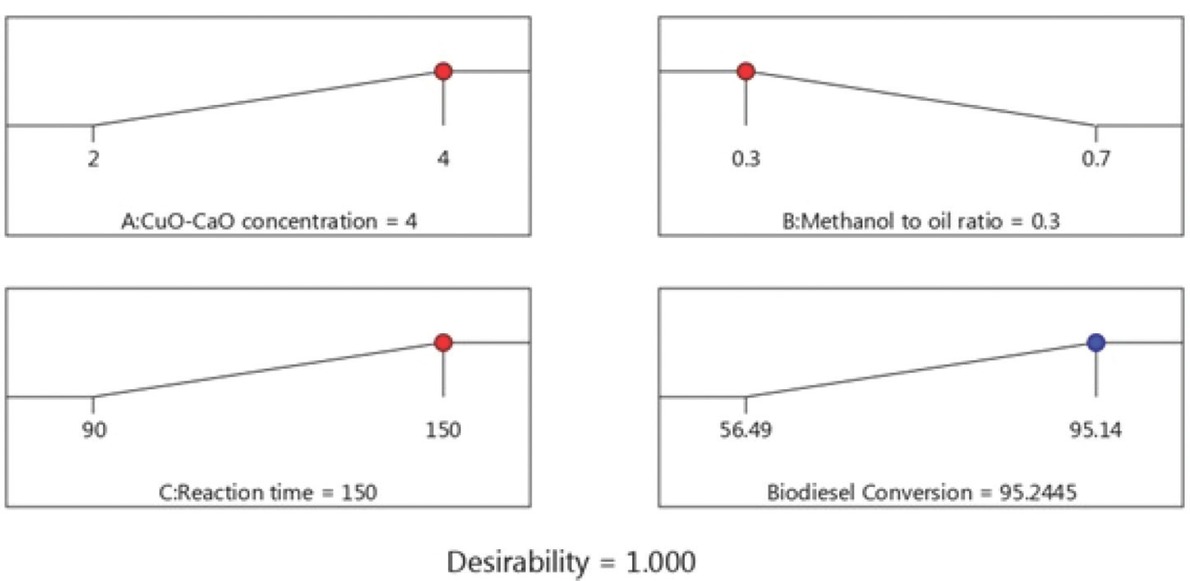

3.6 Optimum process conditions

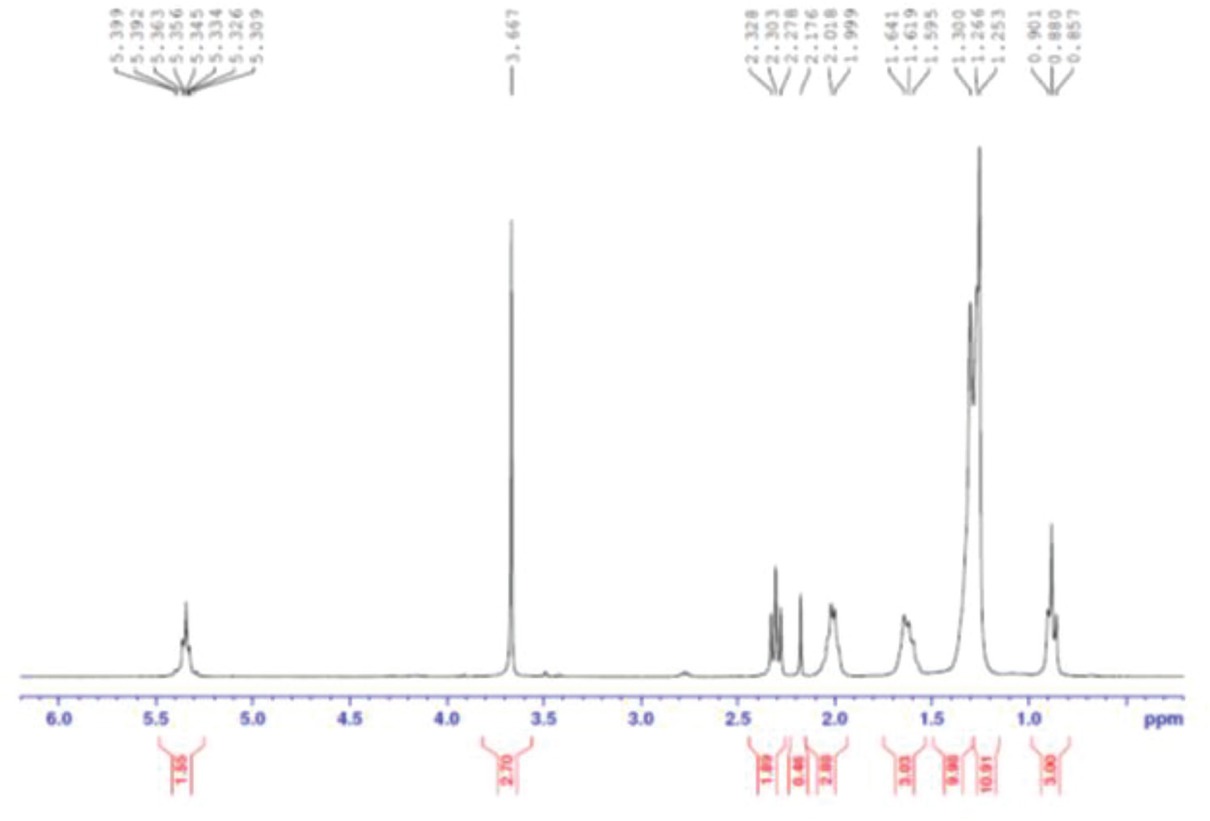

Several studies on esterification optimization employing experimental design on various non-edible sources such as Madhuca indica oil [64], Jatropha curcas [65], Ricinus communis [66], Hevea brasiliensis [33,67], and waste coffee grounds oil [68] were reported. Also, numerous studies are available for optimization of transesterification process variables using RSM on various lipid feedstocks such as waste cooking oil [69], Jojoba oil [70], palm oil [71], Jatropha curcas [72], scum oil [73], shea butter [74], soybean oil [30], and canola oil [75]. In this research, the optimal points for the esterification and transesterification process were obtained through selecting the desired input level using the numerical optimization tool [71,76]. The predicted optimal conditions for maximum reduction of acid value (Figure 11) were found to be H2SO4 loading – 0.85 vol%, methanol to oil volumetric ratio – 1:1 and esterification time – 70.20 min resulted in a predicted acid value of 3.21 mg of KOH/g oil. Similarly, the predicted optimum process conditions for transesterification (Figure 12) were CuO-CaO concentration – 4 wt%, methanol to oil volumetric ratio – 0.3:1 (v/v) and reaction time – 150 min resulted in a predicted MOME conversion of 95.245%. The model prophecies were corroborated by performing additional trials under optimum conditions. The average actual acid value observed as 3.10 mg of KOH/g oil for esterification reaction and the maximum MOME conversion achieved was 95.24% (Figure 13) using Eq. 1. The obtained result showed that the actual value is in accordance with predicted value. The synthesized M. oleifera biodiesel was characterized using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy (GC-MS, Bruker, Scion 436, Germany). BR-5MS column having the composition 5% Diphenyl and 95% Dimethyl polysiloxane was employed and GC-grade helium gas was utilized as carrier gas with constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The biodiesel sample was introduced via the injector system maintained at 280°C having 10:1 split ratio. Primarily, oven temperature maintained at 110°C (holding - 3.5 min) and it was ramped-up to 200°C with 10°C/min. Furthermore, the temperature was ramped-up to 280°C with 5°C/min (held for 12 min). MS (TQ Quadrupole) inlet temperature was maintained at 290°C while the source being maintained at 250°C and the NIST library (Version -11) was utilized for the identification of compounds. The fatty acid composition of synthesized MOME was shown in Table 8 and its corresponding spectrum was presented in Figure 14.

Optimized esterification conditions and predicted acid value.

Optimized transesterification conditions and predicted MOME conversion.

1H-NMR spectra of synthesized MOME.

GC-MS spectra of synthesized MOME.

3.7 Catalyst reusability studies

Catalyst reuse is one of the substantial attributes of heterogeneous catalysts. The studies on reuse of prepared CuO-CaO catalyst was performed under the optimized conditions. The catalyst obtained after the end of transesterification reaction was washed with methanol and then dried (overnight) in hot air oven at 105°C. For the first five cycles, the biodiesel conversion was maintained above 90%. However, the biodiesel conversion was drastically decreased after 5th cycle due to the reduction in active sites. From the overall observations, the synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst holds good stability and sustained the activity up to five consecutive runs.

3.8 Comparison of optimal esterification conditions with previously reported studies

An overview of various research works presented on esterification using Moringa oleifera oil was illustrated in Table 9 and the optimal conditions from the current research ensued maximum drop in acid value from 80.5 to 3.10 mg of KOH/g of oil at a lower catalyst loading of 0.847 vol% and moderate reaction time of 70.11 min. Furthermore, no earlier reports were available on MOO based esterification optimization using experimental design.

Comparison of esterification conditions with the previous studies.

| Esterification reaction conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst type | Catalyst concentration (%) | Methanol to oil ratio (molar) | Reaction time (min) | Reaction temperature (°C) | Agitation speed (rpm) | Acid value (mg of KOH/g oil) | References |

| H2SO4 | 1a | 12:1 | 180 | 60 | 400 | - | [40] |

| H2SO4 | 0.5b | 6:1 | 20-30 | 50 | - | 2.5d | [77] |

| H2SO4 | 1a | 12:1 | 180 | 60 | 600 | - | [22,78, 79, 80] |

| H2SO4 | 1b | 10:1 | 60 | -z | - | 13.2d | [44] |

| H2SO4 | 1a | 12:1 | 180 | 60 | 600 | 8.62d | [31,81] |

| H2SO4 | 0.85a | 1:1c | 70.20 | 60 | 450 | 80.40d – 3.10e | Present work (Optimized condition) |

a – catalyst concentration (%) on the volumetric basis with respect to (v/voil)

b – catalyst concentration (%) on a weight basis with respect to (w/woil)

c – methanol to oil ratio on the volumetric basis

d – the acid value of MOO

e – the acid value of esterified MOO

4 Conclusion

In the present research, experimental optimization for esterification and transesterification of Moringa oleifera oil (MOO) was done by RSM using CCD. The acid value of crude MOO was diminished from 80.5 mg of KOH/ g of oil to 3.10 mg of KOH/g of oil using 0.85 vol% H2SO4 loading, 1:1 volumetric ratio, esterification time of 70.20 min at 60°C as the optimal process conditions. From the ANOVA table, it was observed that methanol to oil volumetric ratio was the most substantial variable in reducing the acid value of crude MOO. A novel CuO-CaO heterogeneous base catalyst has been developed and characterized using FTIR, XRD, SEM and EDAX analysis. SEM analysis of CuO-CaO catalyst revealed that the particles have a very high porosity which in turn provides a very high surface area for the reaction to take place, thereby increasing its catalytic activity. FTIR analysis confirmed the successful integration of CaO derived from conch shell into CuO-NP. Esterified MOO was further utilized for transesterification reaction using synthesized CuO-CaO catalyst and high biodiesel conversion of 95.24% was acquired using 4 wt% CuO-CaO catalyst, 0.3:1 methanol to oil volumetric ratio, 150 min reaction time, and 65°C reaction temperature. Furthermore, the developed CuO-CaO catalyst drastically reduces the problem of Ca-based soap formation at the top of the biodiesel layer. Thus, the current work clearly shows the promising use of CuO-CaO nanoparticles as heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production.

Acknowledgment

SN is grateful to Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), New Delhi, India for Early Career Research Award (ECR) and MB is thankful to SERB for the award of Junior Research Fellowship (JRF).

References

[1] Mofijur M., Atabani A.E., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Masum B.M., A study on the effects of promising edible and non-edible biodiesel feedstocks on engine performance and emissions production: A comparative evaluation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2013, 23, 391-404, DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.009.10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.009Search in Google Scholar

[2] British Petroleum. Stat. Rev., World Energy, 2018. https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html (accessed March 21, 2018).Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tan P.-Q., Hu Z.-Y., Lou D.-M., Li Z.-J., Exhaust emissions from a light-duty diesel engine with Jatropha biodiesel fuel. Energy, 2012, 39, 356-362, DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.002.10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[4] Meher L.C., Vidya Sagar D., Naik S.N., Technical aspects of biodiesel production by transesterification - A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2006, 10, 248-268, DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2004.09.002.10.1016/j.rser.2004.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[5] Mićić R., Tomić M., Martinović F., Kiss F., Simikić M., Aleksic A., Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: Investigation and optimization of process parameters. Green Process. Synth., 2018, DOI:10.1515/gps-2017-0118.10.1515/gps-2017-0118Search in Google Scholar

[6] Malins K., The potential of K3PO4 K2CO3 Na3PO4 and Na2CO3 as reusable alkaline catalysts for practical application in biodiesel production. Fuel Process. Technol., 2018, 179, 302-312, DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.07.017.10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.07.017Search in Google Scholar

[7] Gaikwad N.D., Gogate P.R., Synthesis and application of carbon based heterogeneous catalysts for ultrasound assisted biodiesel production. Green Process. Synth., 2015, 4, 17-30, DOI:10.1515/gps-2014-0079.10.1515/gps-2014-0079Search in Google Scholar

[8] Varghese R., Joy Prabu I., Synthesis and characterizations of needle-shaped CuO nanoparticles for biodiesel application. Int. J. Adv. Res., 2017, 5, 1642-1648, DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/2930.10.21474/IJAR01/2930Search in Google Scholar

[9] Liu Y.C., Lin L.H., Chiu W.H., Size-controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticles from bulk gold substrates by sonoelectrochemical methods. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2004, 108, 19237-19240, DOI:10.1021/jp046866z.10.1021/jp046866zSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Mott D., Galkowski J., Wang L., Luo J., Zhong C.J., Synthesis of size-controlled and shaped copper nanoparticles. Langmuir, 2007, 23, 5740-5745, DOI:10.1021/la0635092.10.1021/la0635092Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Vidyasagar C.C., Naik Y.A., Venkatesh T.G., Viswanatha R., Solid-state synthesis and effect of temperature on optical properties of Cu-ZnO, Cu-CdO and CuO nanoparticles. Powder Technol., 2011, 214, 337-343, DOI:10.1016/j.powtec.2011.08.025.10.1016/j.powtec.2011.08.025Search in Google Scholar

[12] Thi T.V., Rai A.K., Gim J., Kim J., Potassium-doped copper oxide nanoparticles synthesized by a solvothermal method as an anode material for high-performance lithium ion secondary battery. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2014, 305, 617-625, DOI:10.1016/j. apsusc.2014.03.144.10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.03.144Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sudakar C., Thakur J.S., Lawes G., Naik R., Naik V.M., Ferromagnetism induced by planar nanoscale CuO inclusions in Cu-doped ZnO thin films. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys., 2007, 75, 1-6, DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.75.054423.10.1103/PhysRevB.75.054423Search in Google Scholar

[14] Liu X., He H., Wang Y., Zhu S., Piao X., Transesterification of soybean oil to biodiesel using CaO as a solid base catalyst 2008, 87, 216-221, DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2007.04.013.10.1016/j.fuel.2007.04.013Search in Google Scholar

[15] Baskar G., Gurugulladevi A., Nishanthini T., Aiswarya R., Tamilarasan K., Optimization and kinetics of biodiesel production from Mahua oil using manganese doped zinc oxide nanocatalyst. Renew. Energy, 2017, 103, 641-646, DOI:10.1016/j. renene.2016.10.077.10.1016/j.renene.2016.10.077Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mapossa A.B., Costa A.C.F.M., Cornejo D.R., Dantas J., Leal E., Magnetic nanocatalysts of Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 doped with Cu and performance evaluation in transesterification reaction for biodiesel production. Fuel, 2016, 191, 463-471, DOI:10.1016/j. fuel.2016.11.107.10.1016/j.fuel.2016.11.107Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mansourpanah Y., Molaei R., Bet-Moushoul E., Farhadi K., Nikbakht A.M., Forough M., Application of CaO-based/Au nanoparticles as heterogeneous nanocatalysts in biodiesel production. Fuel, 2015, 164, 119-127, DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2015.09.067.10.1016/j.fuel.2015.09.067Search in Google Scholar

[18] Feyzi M., Norouzi L., Preparation and kinetic study of magnetic Ca/Fe3O4@SiO2 nanocatalysts for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy, 2016, 94, 579-586, DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.086.10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.086Search in Google Scholar

[19] Esipovich A.L., Rogozhin A.E., Belousov A.S., Kanakov E.A., Danov S.M., A comparative study of the separation stage of rapeseed oil transesterification products obtained using various catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol., 2018, 173, 153-164, DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.01.023.10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.01.023Search in Google Scholar

[20] Niju S., Anushya C., Balajii M., Process optimization for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil using conch shells as heterogeneous catalyst. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy, 2018, DOI:10.1002/ep.13015.10.1002/ep.13015Search in Google Scholar

[21] Buasri A., Loryuenyong V., The new green catalysts derived from waste razor and surf clam shells for biodiesel production in a continuous reactor. Green Process. Synth., 2015, 4, 389-397.10.1515/gps-2015-0047Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mobarak H.M., Kalam M.A., Fattah I.M.R., Masjuki H.H., Mofijur M., Atabani A.E., Comparative evaluation of performance and emission characteristics of Moringa oleifera and Palm oil based biodiesel in a diesel engine. Ind. Crops Prod., 2014, 53, 78-84, DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.12.011.10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[23] Rashed M.M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Alabdulkarem A., Rahman M.M., Imdadul H.K., et al., Study of the oxidation stability and exhaust emission analysis of Moringa olifera biodiesel in a multi-cylinder diesel engine with aromatic amine antioxidants. Renew. Energy, 2016, 94, 294-303, DOI:10.1016/j. renene.2016.03.043.10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.043Search in Google Scholar

[24] Aziz M.A.A., Triwahyono S., Jalil A.A., Rapai H.A.A., Atabani A.E., Transesterification of Moringa oleifera oil to biodiesel over potassium flouride loaded on eggshell as catalyst. Malaysian J. Catal., 2016, 1, 22-26.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Kafuku G., Lam M.K., Kansedo J., Lee K.T., Mbarawa M., Heterogeneous catalyzed biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil. Fuel Process. Technol., 2010, 91, 1525-1529, DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.05.032.10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.05.032Search in Google Scholar

[26] Balajii M., Niju S., Esterification optimization of underutilized Ceiba pentandra oil using response surface methodology. Biofuels, 2019, 1-8, DOI:10.1080/17597269.2018.1496384.10.1080/17597269.2018.1496384Search in Google Scholar

[27] Niju S., Rabia R., Sumithra Devi K., Naveen Kumar M., Balajii M., Modified Malleus malleus shells for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: An optimization study using Box-Behnken design. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2018, DOI:10.1007/s12649-018-0520-6.10.1007/s12649-018-0520-6Search in Google Scholar

[28] Niju S., Begum M.M.M.S., Anantharaman N., Modification of egg shell and its application in biodiesel production. J. Saudi Chem. Soc., 2014, 18, 702-706, DOI:10.1016/j.jscs.2014.02.010.10.1016/j.jscs.2014.02.010Search in Google Scholar

[29] Knothe G., Analyzing biodiesel: Standards and other methods. JAOCS, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 2006, 83, 823-833, DOI:10.1007/s11746-006-5033-y.10.1007/s11746-006-5033-ySearch in Google Scholar

[30] Tan Z., Zhang X., Kuang Y., Du H., Song L., Han X., et al., Optimized microemulsion production of biodiesel over lipase-catalyzed transesterification of soybean oil by response surface methodology. Green Process. Synth., 2014, 3, 471-478, DOI:10.1515/gps-2014-0066.10.1515/gps-2014-0066Search in Google Scholar

[31] Rashed M.M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Alabdulkarem A., Rahman M.M., Imdadul H.K., et al., Study of the oxidation stability and exhaust emission analysis of Moringa oleifera biodiesel in a multi-cylinder diesel engine with aromatic amine antioxidants. Renew. Energy, 2016, 94, 294-303, DOI:10.1016/j. renene.2016.03.043.10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.043Search in Google Scholar

[32] Mofijur M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Rasul M.G., Atabani A.E., Hazrat M.A., et al., Effect of biodiesel-diesel blending on physico-chemical properties of biodiesel produced from Moringa oleifera Procedia Eng., 2015, 105, 665-669, DOI:10.1016/j.proeng.2015.05.046.10.1016/j.proeng.2015.05.046Search in Google Scholar

[33] Trinh H., Yusup S., Uemura Y., Optimization and kinetic study of ultrasonic assisted esterification process from rubber seed oil. Bioresour. Technol., 2018, 247, 51-57, DOI:10.1016/j. biortech.2017.09.075.10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.075Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Ghadge S.V., Raheman H., Biodiesel production from mahua Madhuca indica oil having high free fatty acids. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2005, 28, 601-605, DOI:10.1016/j. biombioe.2004.11.009.10.1016/j.biombioe.2004.11.009Search in Google Scholar

[35] Mazumdar P., Dasari S.R., Borugadda V.B., Srivasatava G., Sahoo L., Goud V. V., Biodiesel production from high free fatty acids content Jatropha curcas L. oil using dual step process. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, 2013, 3, 361-369, DOI:10.1007/s13399-013-0077-3.10.1007/s13399-013-0077-3Search in Google Scholar

[36] Naik M., Meher L.C., Naik S.N., Das L.M., Production of biodiesel from high free fatty acid Karanja Pongamia pinnata oil. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2008, 32, 354-357, DOI:10.1016/j. biombioe.2007.10.006.10.1016/j.biombioe.2007.10.006Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kafuku G., Mbarawa M., Alkaline catalyzed biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil with optimized production parameters. Appl. Energy, 2010, 87, 2561-2565, DOI:10.1016/j. apenergy.2010.02.026.10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.02.026Search in Google Scholar

[38] da Silva J.P. V, Serra T.M., Gossmann M., Wolf C.R., Meneghetti M.R., Meneghetti S.M.P., Moringa oleifera oil: Studies of characterization and biodiesel production. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2010, 34, 1527-1530, DOI:10.1016/j. biombioe.2010.04.002.10.1016/j.biombioe.2010.04.002Search in Google Scholar

[39] Rashid U., Anwar F., Ashraf M., Saleem M., Yusup S., Application of response surface methodology for optimizing transesterification of Moringa oleifera oil: Biodiesel production. Energy Convers. Manag., 2011, 52, 3034-3042, DOI:10.1016/j. enconman.2011.04.018.10.1016/j.enconman.2011.04.018Search in Google Scholar

[40] Atabani A.E., Mahlia T.M.I., Masjuki H.H., Badruddin I.A., Yussof H.W., Chong W.T., et al., A comparative evaluation of physical and chemical properties of biodiesel synthesized from edible and non-edible oils and study on the effect of biodiesel blending. Energy, 2013, 58, 296-304, DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2013.05.040.10.1016/j.energy.2013.05.040Search in Google Scholar

[41] Atabani A.E., Mahlia T.M.I., Anjum Badruddin I., Masjuki H.H., Chong W.T., Lee K.T., Investigation of physical and chemical properties of potential edible and non-edible feedstocks for biodiesel production, A comparative analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2013, 21, 749-755, DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2013.01.027.10.1016/j.rser.2013.01.027Search in Google Scholar

[42] Wakil M.A., Kalam M.A., Masjuki H.H., Rizwanul Fattah I.M., Masum B.M., Evaluation of rice bran, sesame and moringa oils as feasible sources of biodiesel and the effect of blending on their physicochemical properties. RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 56984-56991, DOI:10.1039/C4RA09199J.10.1039/C4RA09199JSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Zubairu A., Ibrahim F.S., Moringa oleifera oilseed as viable feedstock for biodiesel production in northern Nigeria. Int. J. Energy Eng., 2014, 4, 21-25, DOI:10.5923/j.ijee.20140402.01.10.5923/j.ijee.20140402.01Search in Google Scholar

[44] Fernandes D.M., Sousa R.M.F., De Oliveira A., Morais S.A.L., Richter E.M., Muñoz R.A.A., Moringa oleifera A potential source for production of biodiesel and antioxidant additives. Fuel, 2015, 146, 75-80, DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2014.12.081.10.1016/j.fuel.2014.12.081Search in Google Scholar

[45] Eloka-Eboka A.C., Inambao F.L., Hybridization of feedstocks - A new approach in biodiesel development: A case of Moringa and Jatropha seed oils. Energy Sources, Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff., 2016, 38, 1495-1502, DOI:10.1080/15567036.2014.934413.10.1080/15567036.2014.934413Search in Google Scholar

[46] Mariod A.A., Saeed Mirghani M.E., Hussein I., Mariod A.A., Saeed Mirghani M.E., Hussein I., Moringa oleifera seed oil. Unconv. Oilseeds Oil Sources, Academic Press, 2017, p. 233-241, DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-809435-8.00035-4.10.1016/B978-0-12-809435-8.00035-4Search in Google Scholar

[47] Syazwani O.N., Teo S.H., Islam A., Taufiq-Yap Y.H., Transesterification activity and characterization of natural CaO derived from waste venus clam Tapes belcheri S.) material for enhancement of biodiesel production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2017, 105, 303-315, DOI:10.1016/j.psep.2016.11.011.10.1016/j.psep.2016.11.011Search in Google Scholar

[48] Mazaheri H., Ong H.C., Masjuki H.H., Amini Z., Harrison M.D., Wang C.T., et al., Rice bran oil based biodiesel production using calcium oxide catalyst derived from Chicoreus brunneus shell. Energy, 2018, 144, 10-19, DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2017.11.073.10.1016/j.energy.2017.11.073Search in Google Scholar

[49] Busca G., FT-IR study of the surface of copper oxide. J. Mol. Catal., 1987, 43, 225-36.10.1016/0304-5102(87)87010-4Search in Google Scholar

[50] Jadhav S., Gaikwad S., Nimse M., Rajbhoj A., Copper oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and their antibacterial activity. J. Clust. Sci., 2011, 22, 121-129, DOI:10.1007/s10876-011-0349-7.10.1007/s10876-011-0349-7Search in Google Scholar

[51] Padil V.V.T., Černík M., Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using gum karaya as a biotemplate and their antibacterial application. Int. J. Nanomedicine, 2013, 8, 889-898, DOI:10.2147/IJN.S40599.10.2147/IJN.S40599Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Niju S., Niyas M., Begum S., Kader Mohamed Meera Anantharaman N., KF-impregnated clam shells for biodiesel production and its effect on a diesel engine performance and emission characteristics. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy, 2015, 34, 1166-1173, DOI:10.1002/ep.10.1002/epSearch in Google Scholar

[53] Madhuvilakku R., Piraman S., Biodiesel synthesis by TiO2-ZnO mixed oxide nanocatalyst catalyzed palm oil transesterification process. Bioresour. Technol., 2013, 150, 55-59, DOI:10.1016/j. biortech.2013.09.087.10.1016/j.biortech.2013.09.087Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Kayani Z.N., Umer M., Riaz S., Naseem S., Characterization of copper oxide nanoparticles fabricated by the Sol-Gel Method. J. Electron. Mater., 2015, 44, 3704-3709, DOI:10.1007/s11664-015-3867-5.10.1007/s11664-015-3867-5Search in Google Scholar

[55] Das D., Nath B.C., Phukon P., Dolui S.K., Synthesis and evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial behavior of CuO nanoparticles. Colloid. Surface. B, 2013, 101, 430-433, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Kumar P.P.N.V., Shameem U., Kollu P., Kalyani R.L., Pammi S.V.N., Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Aloe vera leaf extract and its antibacterial activity against fish bacterial pathogens. Bionanoscience, 2015, 5, 135-139, DOI:10.1007/ s12668-015-0171-z.10.1007/s12668-015-0171-zSearch in Google Scholar

[57] Sivaraj R., Rahman P.K.S.M., Rajiv P., Narendhran S., Venckatesh R., Biosynthesis and characterization of Acalypha indica mediated copper oxide nanoparticles and evaluation of its antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Spectrochim. Acta A, 2014, 129, 255-258, DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2014.03.027.10.1016/j.saa.2014.03.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Niju S., Indhumathi J., Begum K.M.M.S., Anantharaman N., Tellina tenuis : a highly active environmentally benign catalyst for the transesterification process. Biofuels, 2016, 0, 1-6, DOI:1 0.1080/17597269.2016.1236006.10.1080/17597269.2016.1236006Search in Google Scholar

[59] Patterson A.L., The scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys. Rev., 1939, 56, 978-982, DOI:10.1103/ PhysRev.56.978.10.1103/PhysRev.56.978Search in Google Scholar

[60] Lee S.L., Wong Y.C., Tan Y.P., Yew S.Y., Transesterification of palm oil to biodiesel by using waste obtuse horn shell-derived CaO catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag., 2015, 93, 282-288, DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.12.067.10.1016/j.enconman.2014.12.067Search in Google Scholar

[61] Mansir N., Teo S.H., Rashid U., Taufiq-Yap Y.H., Efficient waste Gallus domesticus shell derived calcium-based catalyst for biodiesel production. Fuel, 2018, 211, 67-75, DOI:10.1016/j. fuel.2017.09.014.10.1016/j.fuel.2017.09.014Search in Google Scholar

[62] Boonyuen S., Smith S.M., Malaithong M., Prokaew A., Cherdhirunkorn B., Luengnaruemitchai A., Biodiesel production by a renewable catalyst from calcined Turbo jourdani (Gastropoda: Turbinidae) shells. J. Clean. Prod., 2018, 177, 925-929, DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.137.10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.137Search in Google Scholar

[63] Goli J., Sahu O., Development of heterogeneous alkali catalyst from chicken eggshell for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy, 2018, DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2018.05.048.10.1016/j.renene.2018.05.048Search in Google Scholar

[64] Ghadge S.V., Raheman H., Process optimization for biodiesel production from mahua Madhuca indica oil using response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol., 2006, 97, 379-384, DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2005.03.014.10.1016/j.biortech.2005.03.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Kumar Tiwari A., Kumar A., Raheman H., Biodiesel production from jatropha oil Jatropha curcas with high free fatty acids: An optimized process. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2007, 31, 569-575, DOI:10.1016/j.biombioe.2007.03.003.10.1016/j.biombioe.2007.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[66] Halder S., Dhawane S.H., Kumar T., Halder G., Acid-catalyzed esterification of castor Ricinus communis oil: Optimization through a central composite design approach. Biofuels, 2015, 6, 191-201, DOI:10.1080/17597269.2015.1078559.10.1080/17597269.2015.1078559Search in Google Scholar

[67] Van T.D.S., Trung N.P., Anh V.N., Lan H.N., Kim A.T., Optimization of esterification of fatty acid rubber seed oil for methyl ester synthesis in a plug flow reactor. Int. J. Green Energy, 2016, 13, 720-729, DOI:10.1080/15435075.2014.966372.10.1080/15435075.2014.966372Search in Google Scholar

[68] Mueanmas C., Nikhom R., Kaew-On J., Prasertsit K., Statistical optimization for esterification of waste coffee grounds oil using response surface methodology. Energy Procedia, 2017, 138, 235-240, DOI:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.10.043.10.1016/j.egypro.2017.10.043Search in Google Scholar

[69] Hamze H., Akia M., Yazdani F., Optimization of biodiesel production from the waste cooking oil using response surface methodology. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2015, 94, 1-10, DOI:10.1016/j.psep.2014.12.005.10.1016/j.psep.2014.12.005Search in Google Scholar

[70] Bouaid A., Bajo L., Martinez M., Aracil J., Optimization of biodiesel production from jojoba oil. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2007, 85, 378-382, DOI:10.1205/psep07004.10.1205/psep07004Search in Google Scholar

[71] Safieddin Ardebili S.M., Hashjin T.T., Ghobadian B., Najafi G., Mantegna S., Cravotto G., Optimization of biodiesel synthesis under simultaneous ultrasound-microwave irradiation using response surface methodology (RSM). Green Process. Synth., 2015, 4, 259-267, DOI:10.1515/gps-2015-0029.10.1515/gps-2015-0029Search in Google Scholar

[72] Lee H. V., Taufiq-Yap Y.H., Optimization study of binary metal oxides catalyzed transesterification system for biodiesel production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2015, 94, 430-440, DOI:10.1016/j.psep.2014.10.001.10.1016/j.psep.2014.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[73] Yatish K. V., Lalithamba H.S., Suresh R., Arun S.B., Kumar P.V., Optimization of scum oil biodiesel production by using response surface methodology. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2016, 102, 667-672, DOI:10.1016/j.psep.2016.05.026.10.1016/j.psep.2016.05.026Search in Google Scholar

[74] Ajala E.O., Aberuagba F., Olaniyan A.M., Ajala M.A., Sunmonu M.O., Optimization of a two stage process for biodiesel production from shea butter using response surface methodology. Egypt. J. Pet., 2016, 26, 1-11, DOI:10.1016/j. ejpe.2016.11.005.10.1016/j.ejpe.2016.11.005Search in Google Scholar

[75] Rezayan A., Taghizadeh M., Synthesis of magnetic mesoporous nanocrystalline KOH/ZSM-5-Fe3O4 for biodiesel production: Process optimization and kinetics study. Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2018, 117, 711-721, DOI:10.1016/j.psep.2018.06.020.10.1016/j.psep.2018.06.020Search in Google Scholar

[76] Kamalini A., Muthusamy S., Ramapriya R., Muthusamy B., Pugazhendhi A., Optimization of sugar recovery efficiency using microwave assisted alkaline pretreatment of cassava stem using response surface methodology and its structural characterization. J. Mol. Liq., 2018, 254, 55-63, DOI:10.1016/j. molliq.2018.01.091.10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.091Search in Google Scholar

[77] Kivevele T.T., Mbarawa M.M., Bereczky Á., Zöldy M., Evaluation of the oxidation stability of biodiesel produced from Moringa oleifera oil. Energy and Fuels, 2011, 25, 5416-5421, DOI:10.1021/ef200855b.10.1021/ef200855bSearch in Google Scholar

[78] Atabani A.E., Mofijur M., Masjuki H.H., Badruddin I.A., Kalam M.A., Chong W.T., Effect of Croton megalocarpusCalophyllum inophyllumMoringa oleifera palm and coconut biodiesel-diesel blending on their physico-chemical properties. Ind. Crops Prod., 2014, 60, 130-137, DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.06.011.10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.06.011Search in Google Scholar

[79] Rahman M.M., Hassan M.H., Kalam M.A., Atabani A.E., Memon L.A., Rahman S.M.A., Performance and emission analysis of Jatropha curcas and Moringa oleifera methyl ester fuel blends in a multi-cylinder diesel engine. J. Clean. Prod., 2014, 65, 304-310, DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.034.10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.034Search in Google Scholar

[80] Mofijur M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Atabani A.E., Arbab M.I., Cheng S.F., et al., Properties and use of Moringa oleifera biodiesel and diesel fuel blends in a multi-cylinder diesel engine. Energy Convers. Manag., 2014, 82, 169-176, DOI:10.1016/j. enconman.2014.02.073.10.1016/j.enconman.2014.02.073Search in Google Scholar

[81] Rashed M.M., Kalam M.A., Masjuki H.H., Mofijur M., Rasul M.G., Zulkifli N.W.M., Performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with palm, jatropha, and moringa oil methyl ester. Ind. Crops Prod., 2016, 79, 70-76, DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.10.046.10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.10.046Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 S. Niju et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system