Abstract

Molecular weight reduction of natural rubber (NR) with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) oxidizing agent is limited in biphasic water-toluene systems that is attributed to mass transfer. In this work, CO2 was applied to the (aqueous H2O2)-(toluene-NR) systems with the objective of improving reaction efficiency. Experiments were performed on the reaction system with CO2 at 12 MPa and at reaction temperatures and times of 60°C–80°C and 1 h–10 h to evaluate the reaction kinetics. CO2 could enhance the NR molecular weight reduction by lowering the activation energy (from 121 kJ·mol−1 to 38 kJ·mol−1). The role of CO2 in the reaction system seems to be the formation of oxidative peroxycarbonic acid intermediate and promotion of mass transport due to the reduction in the toluene-NR viscosity and interfacial tension. The epoxidized liquid NRs (M̅n=4.9×103 g·mol−1) obtained from NR molecular weight reduction was further processed to prepare hydroxyl telechelic NR (M̅n=1.0×103 g·mol−1) and biobased polyurethane.

Abbreviations and symbols

- Abbreviations

- CTNR

carbonyl telechelic natural rubber

- CXL

CO2-expanded liquid

- ELNR

epoxidized liquid natural rubber

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HTNR

hydroxyl telechelic natural rubber

- NR

natural rubber

- PDI

polydispersity index (M̅w/M̅n)

- phr

parts per hundred rubber

- PU

polyurethane

- Symbols

- DPn(t0)

degree of polymerization at beginning t=0, according to Eq. (5)

- DPn(t)

degree of polymerization at the reaction time t, according to Eq. (5)

- Ea

activation energy

- k

rate constant

- M̅n

number-average molecular weight

- M̅w

weight-average molecular weight

- t

reaction time

1 Introduction

Polyurethane is a commodity plastic that has been used in many applications such as building and construction, thermal insulations, transportations, sport equipment, and footwear due to its desirable lightweight, excellent thermal insulating and mechanical properties [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. In the chemical structures of polyurethane, urethane repeating units are produced by the reaction of isocyanates and polyols, which contain hydroxyl groups at the chain ends [5], [6].

Nowadays, polyols are readily derived from biomass feedstocks (e.g. natural rubber (NR) and vegetable oil) [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. NR is one of the most well-known polymers that can be functionalized into biobased polyols [14], [15], [16] due to its structure that contains unsaturated bonds. Scheme 1 shows a four-step reaction pathway for preparing biobased polyurethane from NR that includes three intermediates: epoxidized liquid natural rubber (ELNR), carbonyl telechelic natural rubber (CTNR), and hydroxyl telechelic natural rubber (HTNR). However, the use of virgin NR in Scheme 1 yields non-uniform properties of the resulting biobased polyurethanes due to the broad and high molecular weight of the natural polymer [4], [10]. To produce suitable polymeric materials, it is necessary to reduce the molecular weight of virgin NR before preparing biobased polyurethane.

Reaction pathways for preparing biobased polyurethane from NR including three intermediates as ELNR, CTNR, and HTNR.

In the chemical degradation process, oxidizing agents (e.g. hydrogen peroxide [15], [17], [18], periodic acid [16], [19], potassium persulfate [20], [21], and diphenyl disulfide [22], [23], [24]) were used for molecular weight reduction. Among these oxidizing agents, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is preferable due to its environmentally friendly characteristic [25], [26]. However, H2O2 is typically supplied in an aqueous solution with water up to 70 wt.%, while NR is only soluble in organic phases (e.g. toluene or xylene solvents). Thus, the NR molecular weight reduction with H2O2 as an oxidizing agent is limited due to the mass transfer of H2O2 from the aqueous phase into the organic phase in the biphasic aqueous-organic systems.

The use of CO2 in CO2-expanded liquid (CXL) reaction systems is a promising technique for green and sustainable processes [27], [28], [29], [30] because it allows one to adjust both polarity and transport properties by altering pressure and temperature. In the triphasic CO2/organic solvent/H2O systems with H2O2, the addition of CO2 can (i) promote the formation of oxidative peroxycarbonic acid intermediate by the reaction of CO2 and H2O2 [31], [32], [33] and (ii) promote the solubility of small molecules in the organic phase (e.g. H2, O2, and oxidizing agent) [23], [24], [34] by lowering the viscosity and interfacial tension of the biphasic aqueous-organic systems [35]. The peroxycarbonic acid intermediate can be used as an effective oxidative agent in the epoxidation of olefins in the biphasic systems reported in literature [36], [37], [38], [39]. Thus, chemical degradation in the triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with H2O2 could improve the efficiency of the NR molecular weight reduction.

The first objective of this work is to study the enhancement of NR molecular weight reduction in triphasic systems of CO2/toluene/H2O using H2O2 as an oxidizing agent and toluene as an organic solvent for NR dissolution. The second objective of this work is to prepare biobased polyurethane obtained from the NR molecular weight-modified polymers. A comparative study on the NR molecular weight reduction in biphasic water-toluene systems without the addition of CO2 was made as a basis for assessing the results. Reactions were performed to evaluate the activation energy at a constant CO2 pressure of 12 MPa. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) analyses were used to analyze the products.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Virgin NR STR-5L (Standard Thai Test Rubber) with dirt less than 5% was used as received without further purification. Liquid CO2 (purity≥99.95%) was supplied by United Industrial Gases (Thailand). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with a purity of 30 wt.% was obtained from Fluka Chemical. Toluene, methanol (AR grade), tetrahydrofuran (AR grade), and chloroform (HPLC grade) were purchased from RCI Labscan Co. (Thailand). Periodic acid (H5IO6) and sodium borohydride (NaBH4) were purchased from ACS Reagent Chemical Co. Dibutyltindilaurate (DBTDL) as a catalyst was obtained from Air Products and Chemicals, and toluene diisocyanate (TDI) from IRPC Public Company Limited (Thailand) was used in the preparation of biobased polyurethanes.

2.2 NR molecular weight reduction

NR molecular weight reduction was performed in the presence of CO2 at a constant pressure of 12 MPa over a temperature range of 60°C–80°C and at reaction times of 1 h–10 h using H2O2 concentrations of 10–30 parts per hundred rubber (phr). These conditions were adopted from the literature that did not consider experiments in the presence of CO2 [15], [17], [37].

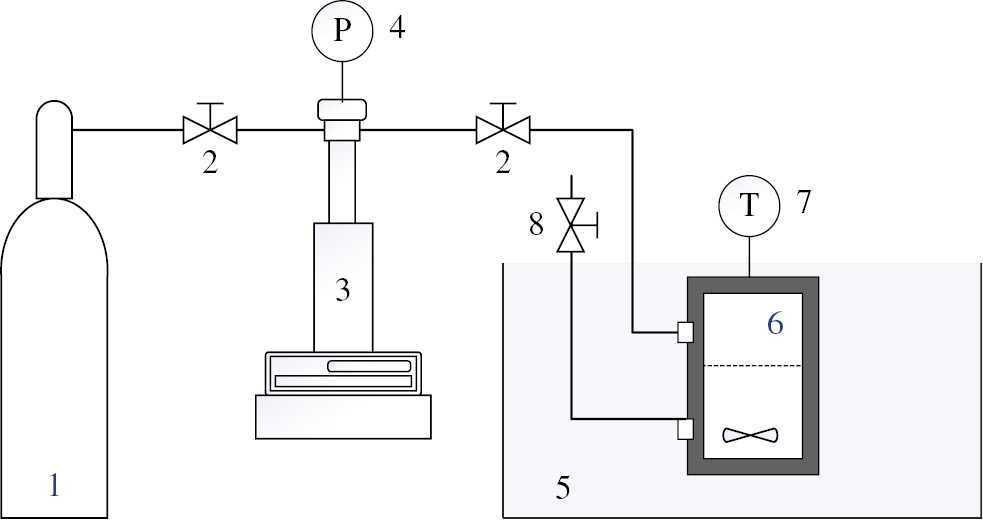

In the experimental apparatus (Figure 1), a solution of NR (1% w/v in toluene) of 5 ml was loaded into a high-pressure vessel (15 ml, Taiatsu Techno/Japan SUS316) and mixed with H2O2 using a magnetic stirrer (550 rpm, g≈9.98 m·s−2). The high-pressure vessel was then placed in a water bath at a constant temperature of 60°C. The residual air inside the vessel was subsequently flushed out with CO2 from the cylinder. CO2 was delivered into the high-pressure vessel by a syringe pump (ISCO 260D, USA) until the pressure inside the vessel rose to 12 MPa. CO2 was then discharged from the vessel after reaching the reaction time. Comparative experiments on NR molecular weight reduction using similar conditions were made without the addition of CO2. The obtained ELNR products in both cases were analyzed with GPC, FT-IR, and 1H-NMR techniques.

Apparatus for chemical degradation of NR using H2O2 as an oxidizing agent in the presence of CO2. (1) CO2 cylinder, (2) valves, (3) syringe pump, (4) pressure gauge, (5) water bath, (6) high-pressure vessel, (7) thermocouple, and (8) relief valve.

2.3 Preparation of biobased polyurethane

ELNRs obtained from the NR molecular weight reduction were subsequently functionalized to CTNR and HTNR as shown in Scheme 1. CTNR was prepared by adding 1.1 mol equivalent of periodic acid (H5IO6) to 0.4 mol·l−1 of the ELNR solutions [Eq. (2), Scheme 1]. The solutions were stirred at a rotational speed of 720 rpm at 60°C for 6 h in a glass reactor with a magnetic stirrer. The CTNR product was neutralized with sodium hydrogen carbonate and sodium chloride.

Subsequently, the resulting CTNR was functionalized to the HTNR solution by adding excess sodium borohydride (5 mol equivalent) at 60°C for 6 h [Eq. (3), Scheme 1]. The obtained HTNR product was then hydrolyzed with 10 ml of cool water, purified by a sodium chloride solution, and dehydrated by magnesium sulfate. The molecular weight and functional groups of the obtained HTNR were analyzed by GPC, FT-IR, and 1H-NMR.

The HTNR was then used as a raw material for preparing HTNR-based polyurethane by a one-shot method [14], [15] [Eq. (4), Scheme 1]. A solution of HTNR in THF at a concentration of 0.5% (w/v) was mixed with dibutyltindilaurate (DBTDL) as a catalyst at a [DBTL]/[OH] ratio of 0.045, before adding isocyanate into the mixture at a [NCO]/[OH] ratio of 1.2 at 60°C. After stirring for 20 min, the resulting HTNR-based polyurethanes were cast onto an aluminum substrate and then cured at 40°C for 48 h. The functional groups of HTNR-based polyurethanes were analyzed with FT-IR.

2.4 Analysis methods

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC): The number-average molecular weight (M̅n), weight-averaged molecular weight (M̅w), and polydispersity index (PDI, M̅w/M̅n) of the samples were characterized by GPC. Before the measurements, the GPC apparatus was calibrated using 0.1% (w/v) polystyrene standard solutions (PS, molecular weights of 30–900 kg·mol−1) in chloroform. The sample was prepared as a 0.1% (w/v) chloroform solution filtered through a 0.2-μm Teflon (Millex) filter. The GPC system had an HPLC pump (Spectra System, model P2000), a GPC column (Shodex, GPC KF-80M with two columns), and a UV-Vis detector at a fixed wavelength (λ) of 254 nm (Lab Alliance, model 201, USA). Chloroform (HPLC) was used as the mobile phase, and the flow rate of the mobile phase was 1 ml·min−1 in the column maintained at 40°C. A sample (20 μl) was injected into the column in the measurements.

FT-IR and 1H-NMR: The functional groups in the chemical structure of NR, ELNR, CTNR, HTNR, and PU were analyzed using FT-IR and 1H-NMR. A dried sample was mixed with potassium bromide tablets and then dried at 60°C for 2 h to remove moisture. The FT-IR spectra were taken in transmission mode with an FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo-Nicolet Avatar 360 Multi Bounce, USA). Each sample was dissolved in chloroform-d (CDCl3), and tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as the internal standard solution. The 1H-NMR spectra were measured with an1H-NMR spectrometer (Bruker, 300 MHz, USA).

3 Kinetic studies

The rate constant (k) and activation energy (Ea) were estimated for assessing the enhancement of NR molecular weight reduction by CO2. The rate constants were estimated from second-order reaction equations as follows [21], [40], [41]], [42]:

where DPn(t) and

where A is the frequency of collisions in the correct orientation, and R is the universal gas constant.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 NR molecular weight reduction

Figure 2A–C and Table 1 show molecular weight reduction in terms of M̅n values of ELNR with CO2 and without CO2. With an increase in reaction time (Figure 2A–C), the M̅n values of ELNR in both cases tended to decrease exponentially during the first two hours and then gradually plateaued. Trends in decrease of M̅n values of ELNR with CO2 (Figure 2A–C) were larger than those without CO2, especially at low temperature.

Number-average molecular weight (M̅n) and reciprocal degree of depolymerization (1/DPn(t)) of ELNR obtained from NR molecular weight reduction using H2O2 in the presence (filled symbols) and in the absence (unfilled symbols) of CO2 as a function of reaction time at 60°C (A and D), 70°C (B and E), and 80°C (C and F). Conditions were performed at a constant pressure of 12 MPa and constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr. (A–C) Lines were calculated by Eq. (5) with rate constants (k) in Table 2. (D–F) Lines were obtained by fitting with Eq. (5) using M̅n values in Table 1.

Number-average molecular weight (M̅n), weight-average molecular weight (M̅w), PDI (M̅w/M̅n), and degree of polymerizationa (DPn) of ELNR obtained from molecular weight reduction of NR using H2O2 with CO2 at a pressure of 12 MPa and without CO2 for a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr.

| Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | With CO2 | Without CO2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M̅w×104 (g·mol−1) | M̅n×104 (g·mol−1) | PDI (−) | DPn×103 (−) | M̅w×104 (g·mol−1) | M̅n×104 (g·mol−1) | PDI (−) | DPn×103 (−) | ||

| 60 | 1 | 44.83 | 9.00 | 4.98 | 4.34 | 101.64 | 24.54 | 4.14 | 3.61 |

| 2 | 22.64 | 5.55 | 4.08 | 1.32 | 77.72 | 21.64 | 3.59 | 3.18 | |

| 3 | 7.87 | 2.86 | 2.75 | 0.82 | 62.34 | 20.03 | 3.11 | 2.95 | |

| 5 | 3.30 | 1.57 | 2.10 | 0.42 | 50.57 | 15.34 | 3.30 | 2.26 | |

| 10 | 2.02 | 1.09 | 1.85 | 0.23 | 26.76 | 9.10 | 2.94 | 1.34 | |

| 70 | 1 | 17.68 | 5.76 | 3.07 | 0.85 | 66.44 | 14.68 | 4.53 | 2.16 |

| 2 | 9.38 | 3.85 | 2.44 | 0.57 | 25.59 | 7.23 | 3.54 | 1.06 | |

| 3 | 4.65 | 1.99 | 2.33 | 0.29 | 21.17 | 6.15 | 3.44 | 0.91 | |

| 5 | 2.55 | 1.18 | 2.17 | 0.17 | 16.84 | 6.11 | 2.76 | 0.90 | |

| 10 | 1.65 | 0.74 | 2.24 | 0.11 | 4.73 | 1.97 | 2.40 | 0.29 | |

| 80 | 1 | 7.26 | 3.28 | 2.22 | 0.48 | 19.29 | 5.50 | 3.51 | 0.81 |

| 2 | 4.59 | 2.23 | 2.06 | 0.33 | 10.06 | 4.67 | 2.15 | 0.69 | |

| 3 | 3.22 | 1.38 | 2.34 | 0.20 | 7.14 | 3.55 | 2.01 | 0.52 | |

| 5 | 1.92 | 0.92 | 1.97 | 0.14 | 5.12 | 2.06 | 2.49 | 0.30 | |

| 10 | 1.05 | 0.49 | 2.12 | 0.07 | 3.59 | 1.21 | 2.95 | 0.18 | |

aDegree of polymerization (DPn), according to Eq. (6).

Trends of NR molecular weight reduction (Figure 2A–C) in both cases were similar to the second-order reaction rate of depolymerization [Eq. (5)]. The k [Eq. (5)] and Ea [Eq. (7)] were calculated from the M̅n values (Table 1). Figure 2D–F shows a linear relationship between degree of depolymerization (1/DPn(t)) and reaction time, according to Eq. (5). The rate constants for NR molecular weight reduction were estimated from the slopes in Figure 2D–F and are tabulated in Table 2. The k values for chemical degradation in both cases (Table 2) showed an increase with temperature, while the k values for experiments made in the presence of CO2 were higher than those in the absence of CO2.

Rate constants (k) of chemical degradation of NR with CO2 at a pressure of 12 MPa and without of CO2 at a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr.

| Temperature (°C) | With CO2 | Without CO2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (min−1) | R2 | k (min−1) | R2 | |

| 60 | 1.07×10−5 | 0.96 | 8.00×10−7 | 0.99 |

| 70 | 1.57×10−5 | 0.98 | 4.90×10−6 | 0.93 |

| 80 | 2.30×10−5 | 0.99 | 9.30×10−6 | 0.98 |

R2, coefficient of determination for fitting with Eq. (5) as shown in Figure 2D–F.

The Ea can be determined from the slopes in Figure 3, according to Eq. (7). The Ea value for molecular weight reduction in the presence of CO2 with H2O2 was 38 kJ·mol−1, which was lower than that in the absence of CO2 (121 kJ·mol−1) or methods in the literature such as chemical degradation with other potassium persulfate oxidizing agent (77 kJ·mol−1) [21] and thermal decomposition of NR (203 kJ·mol−1) [43]. Due to lower oxidative activity, Ea value from chemical degradation with H2O2 was lower than that from potassium persulfate, however, combination of H2O2 with CO2 allowed more effective than that using potassium persulfate.

![Figure 3: Plot of rate constant (k) with inverse temperature (1/T) used to determine Ea [Eq. (6)] of molecular weight reduction using H2O2 in the presence of CO2 (filled symbols, R2=0.99) and absence of CO2 (unfilled symbols, R2=0.94) over a temperature range of 60–80°C, a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr, and at a constant pressure of 12 MPa.](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2018-0092/asset/graphic/j_gps-2018-0092_fig_003.jpg)

Plot of rate constant (k) with inverse temperature (1/T) used to determine Ea [Eq. (6)] of molecular weight reduction using H2O2 in the presence of CO2 (filled symbols, R2=0.99) and absence of CO2 (unfilled symbols, R2=0.94) over a temperature range of 60–80°C, a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr, and at a constant pressure of 12 MPa.

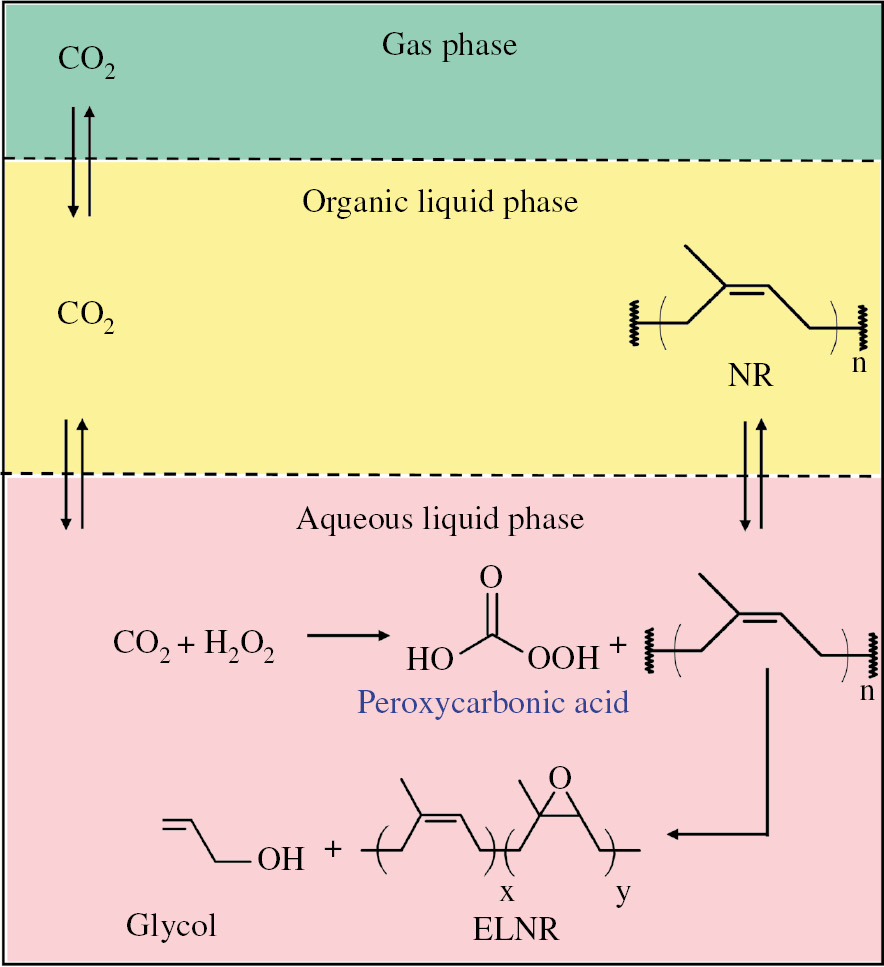

Figure 4 shows a proposed process for NR molecular weight reduction in triphasic CO2/organic/H2O systems. The triphasic systems (Figure 4) include the CO2 phase, the aqueous phase containing H2O2 solution, and the organic phase of NR solution in toluene solvent. As CO2 can be soluble in both aqueous and organic phases, CO2 can cause (i) the formation of peroxycarbonic acid in the aqueous phase by the reaction of CO2 and H2O2, as reported in the literature [32], [33], [36], [37] and (ii) the promotion of the mass transfer of H2O2 to react with NR in the organic phase due to a reduction in viscosity in the organic phase, as reported in the literature [44], [45], [46], [47], and interfacial tension between the aqueous and organic phases according to the molecular dynamics simulation [35].

Proposed molecular weight reduction of NR in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems using H2O2 with CO2 to produce ELNR. The organic phase contains NR solutions in toluene solvent. The aqueous phase contains H2O2 and peroxycarbonic acid intermediate.

To elucidate the effect of peroxycarbonic acid formation on NR molecular weight reduction, the NR molecular weight reduction was carried out in the H2O-CO2 system without the addition of H2O2. The M̅w and PDI values of the NR obtained in the H2O-CO2 system (50°C, 12 MPa, and 5 h) were 8.3×105 g·mol−1 and 3.4, respectively. The NR molecular weight reduction in the H2O-CO2 system was less effective than that with the addition of H2O2, according to the higher M̅w values (Table 1) obtained with CO2. These results were consistent with studies on epoxidation of cyclohexene in H2O-CO2 systems [48] in that no reaction occurred.

The reason for the lack of reaction in the H2O-CO2 system without the addition of H2O2 could be due to unsuitable conditions such as pH for epoxidation because pH higher than 7 is generally required for epoxidation reactions [32], [48]. However, the reaction of CO2 with H2O can generate carbonic acid (pH≈3–4) [31] in the H2O-CO2 systems, while the pH values in the aqueous solution with the addition of H2O2 in the presence or absence of CO2 are typically higher than 7 [32], [33].

CO2 can reduce the viscosity of organic solvents [44], [45], [46], [47] and polymer solutions [49], [50], [51], while the effect of viscosity reduction is negligible in aqueous solutions [52]. Thus, the main reasons for efficient NR molecular weight reduction in the triphasic systems with H2O2 as the oxidizing agent can be thought of as (i) the formation of oxidative peroxycarbonic acid intermediate that synergically reduces the NR molecular weight along with H2O2 and (ii) the promotion of mass transport as CO2 can reduce both organic solution viscosity and interfacial tension that would enhance the degradation reaction and increase in the O2 transport.

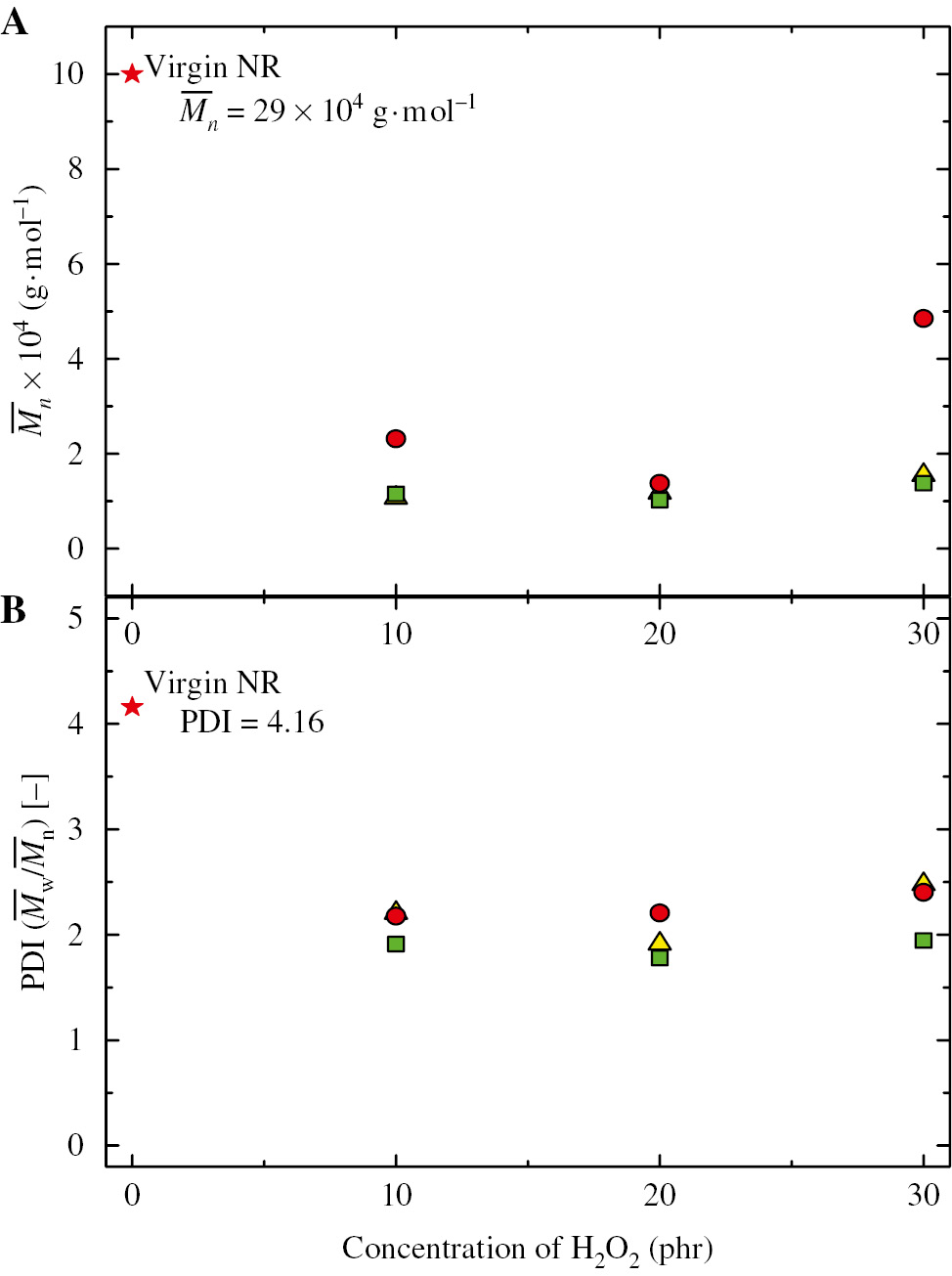

The addition of H2O2 up to 30 phr (Figure 5) caused an increase in M̅n and polydispersity index due to an excess amount of the oxidative agent that promoted retrogressive repolymerization among the free radical chain ends [21], [53]. Therefore, the chemical degradation using H2O2 at 20 phr in the presence of CO2 was used to prepare the ELNR, and the biobased polyurethane as shown in Scheme 1 is discussed in the following section.

Concentration dependence of H2O2 in the unit of phr on (A) the number-averaged molecular weight (M̅n) and (B) PDI (M̅w/M̅n) of virgin NR ( ) and ELNRs obtained from molecular weight reductions of NR using H2O2 in the presence of CO2 at a constant pressure of 12 MPa, a constant temperature of 60°C (

) and ELNRs obtained from molecular weight reductions of NR using H2O2 in the presence of CO2 at a constant pressure of 12 MPa, a constant temperature of 60°C ( ), 70°C (

), 70°C ( ), and 80°C (

), and 80°C ( ) for 5 h.

) for 5 h.

4.2 Chemical structures of NR from molecular weight reduction

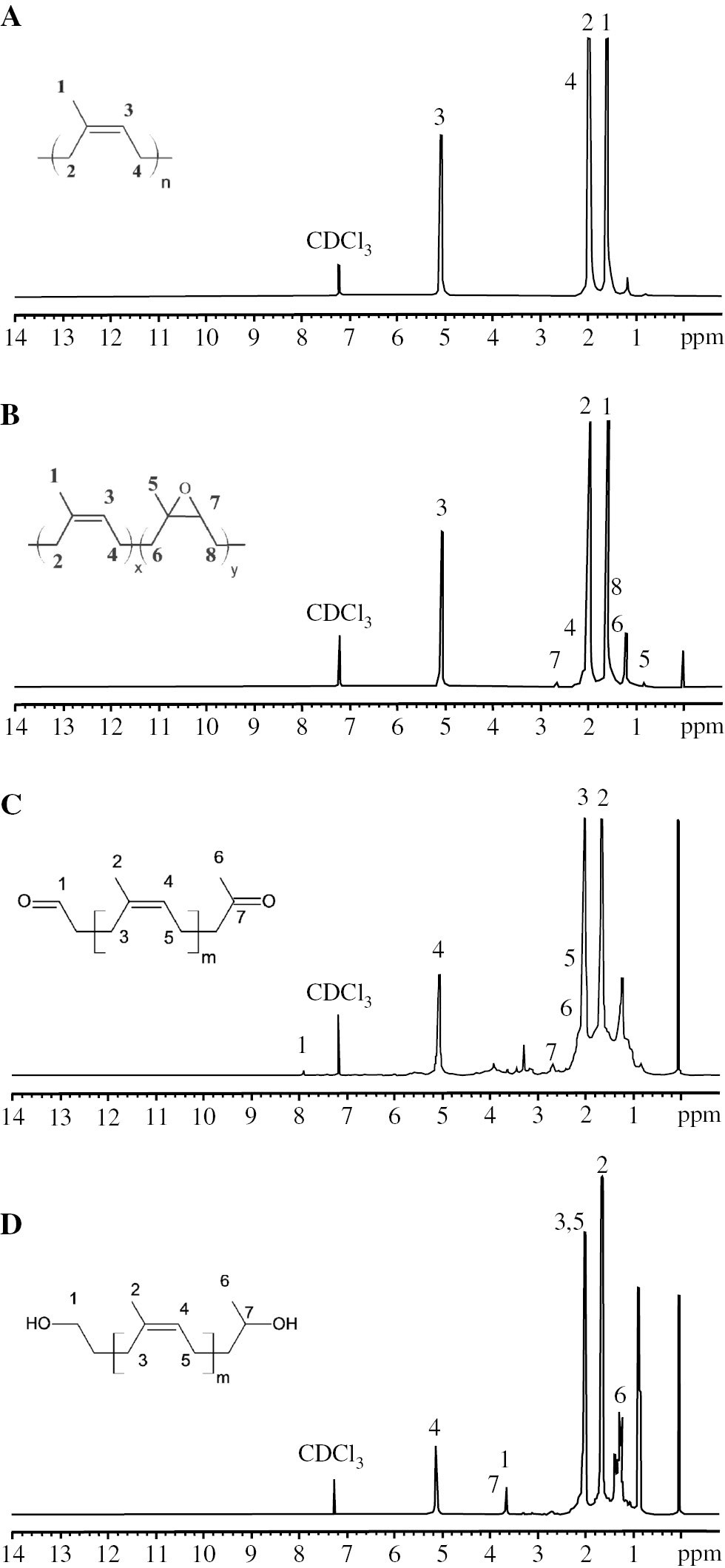

The chemical structures of the ELNR obtained from NR molecular reduction were characterized with 1H-NMR and FT-IR (Figures 6 and 7). The 1H-NMR spectra of both the NR and ELNR (Figure 6A and B) showed the olefinic proton of cis-1,4-polyisopren unit at 5.10 ppm, the methyl proton at 1.67 ppm, and the methylene proton at 2.16 ppm next to the C=C bond. After the molecular weight reduction, small signals of the ELNR (Figure 6B) were detected from the methine proton adjacent to the epoxide ring at 2.70 ppm and the methyl group (-CH3) adjacent to the epoxide unit at 1.30 ppm. The epoxide content of the ELNR was estimated from methods in the literature [16], [17], [54] by considering the integration areas of signals of 2.70 and 5.10 ppm and determined to be 5.7%. Figure 7 shows the FT-IR spectra of the NR and ELNR that exhibited the C=C stretching of polyisoprene at 1665 cm−1. The ELNR (Figure 7) showed a weak signal of the epoxide ring (C-O-C) at 870 cm−1. The 1H-NMR and FT-IR results obtained in this work were in accordance with the literature [16], [17], [19].

1H-NMR spectra of (A) virgin NR, (B) ELNR obtained from molecular weight reduction using H2O2 with CO2 at a constant pressure of 12 MPa, a constant temperature of 80°C, and a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr, (C) CTNR, and (D) HTNR.

FT-IR spectra of virgin NR and ELNR obtained from NR molecular weight reduction using H2O2 in the presence of CO2 at a constant pressure of 12 MPa, a constant temperature of 80°C, and a constant H2O2 concentration of 20 phr for 10 h.

4.3 Preparation of biobased polyurethane

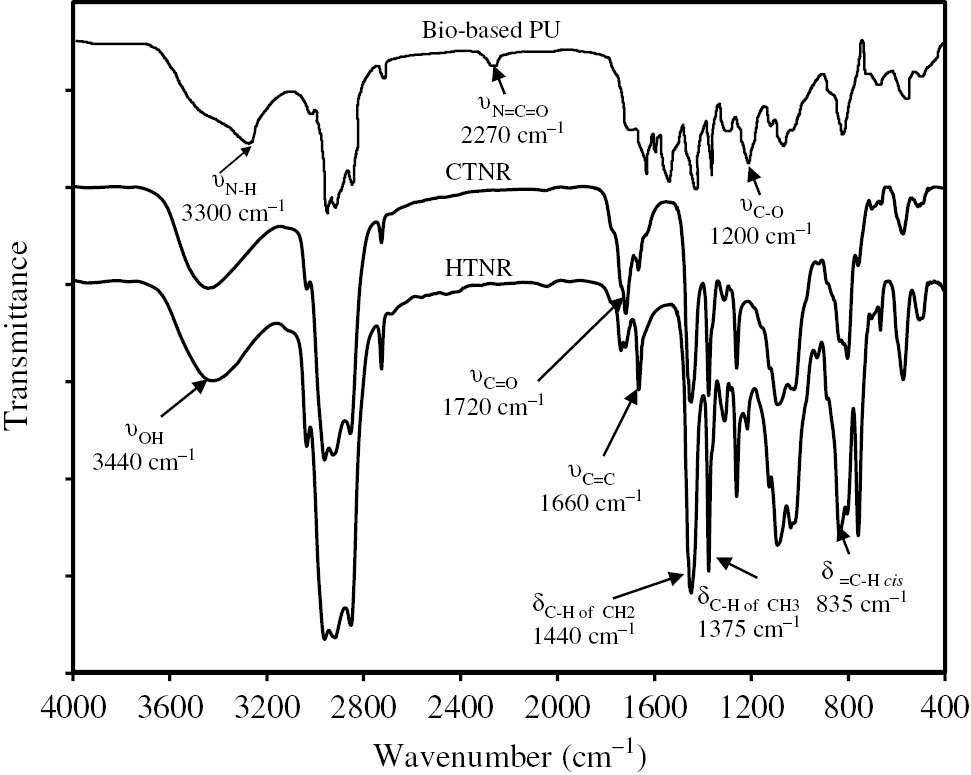

The obtained ELNR was functionalized to CTNR and HTNR [Scheme 1, Eqs. (2) and (3)]. The chemical structures of CTNR and HTNR were confirmed by FT-IR and 1H-NMR (Figures 6 and 8). The FT-IR spectra of the C=O stretching of CTNR at 1720 cm−1 (Figure 8) were observed, which were consistent with the 1H-NMR results (Figure 6C) wherein there appeared new peaks for the aldehyde proton (at 9.80 ppm), the methylic proton in the ketone end groups (at 2.13 ppm), and the CH2 in the α and β terminal carbonyl (-CH2) groups (between 2.20 and 2.60 ppm).

FT-IR spectra of CTNR, HTNR, and biobased polyurethane.

The FT-IR spectra of the OH stretching in the HTNR at 3440 cm−1 (Figure 8) were consistent with 1H-NMR results (Figure 6D) as they showed the appearance of new peaks for methylic protons adjacent to a secondary alcohol (at 1.20 ppm) and two peaks corresponding to CH (3.80 ppm) and CH2 (3.68 ppm) adjacent to alcohol groups at the chain ends. Thus, the FT-IR and 1H-NMR results showed that the hydroxyl functional groups were located at the chain ends of the HTNR.

The functionality of the HTNR was estimated by an 1H-NMR method reported in the literature [15]. The HTNR obtained in this work had two functionalities, indicating that there are two hydroxyl groups at the chain end of the HTNR structure so that the prepared HTNR material can be used for preparing the biobased polyurethane. The biobased polyurethane synthesized from the HTNR was confirmed by FT-IR analysis (Figure 8) that exhibited absorption wavenumbers of 3300 cm−1 for N-H stretching and 1720 cm−1 for C=O stretching.

5 Conclusion

High-pressure (12 MPa) CO2 improves the efficiency of NR molecular weight reduction in water-toluene biphasic systems with hydrogen peroxide as the oxidizing agent. The role of CO2 in the reaction system seems to be to improve mass transport in the toluene phase and to enhance the oxidation rate through H2O2 transport and formation of peroxycarbonic acid intermediate. CO2 lowers the activation energy for the NR molecular weight reduction using H2O2 oxidation by a factor of about three in the water-toluene-NR reaction system. The ELNR obtained a molecular weight reduction that can be used subsequently to prepare biobased polyurethane.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT).

References

[1] Zhang C, Madbouly SA, Kessler MR. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1226–1233.10.1021/am5071333Search in Google Scholar

[2] Li Y, Luo X, Hu S. Introduction to Bio-based Polyols and Polyurethanes. Bio-based Polyols and Polyurethanes, Springer International Publishing: Berlin, 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-21539-6Search in Google Scholar

[3] Isikgor FH, Becer CR. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 4497–4559.10.1039/C5PY00263JSearch in Google Scholar

[4] Amnuaysin T, Buahom P, Areerat S. J. Cell. Plast. 2015, 52, 585–594.10.1177/0021955X15583882Search in Google Scholar

[5] Nohra B, Candy L, Blanco J-F, Guerin C, Raoul Y, Mouloungui Z. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 3771–3792.10.1021/ma400197cSearch in Google Scholar

[6] Engels H-W, Pirkl H-G, Albers R, Albach RW, Krause J, Hoffmann A, Casselmann H, Dormish J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9422–9441.10.1002/anie.201302766Search in Google Scholar

[7] Noreen A, Zia KM, Zuber M, Tabasum S, Zahoor AF. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 91, 25–32.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2015.11.018Search in Google Scholar

[8] Mangili I, Lasagni M, Anzano M, Collina E, Tatangelo V, Franzetti A, Caracino P, Isayev AI. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 121, 369–377.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[9] Shi J, Jiang K, Zou H, Ding L, Zhang X, Li X, Zhang L, Ren D. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40298.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Nik Pauzi NNP, Majid RA, Dzulkifli MH, Yahya MY. Composites, Part B. 2014, 67, 521–526.10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.08.004Search in Google Scholar

[11] Howard GT. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 245–252.10.1016/S0964-8305(02)00051-3Search in Google Scholar

[12] Zhang C, Kessler MR. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.2015, 3, 743–749.10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00049Search in Google Scholar

[13] Rattanapan S, Pasetto P, Pilard J-F, Tanrattanakul V. J. Polym. Res. 2016, 23, 182–194.10.1007/s10965-016-1081-7Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kébir N, Campistron I, Laguerre A, Pilard J-F, Bunel C, Couvercelle J-P, Gondard C. Polymer 2005, 46, 6869–6877.10.1016/j.polymer.2005.05.106Search in Google Scholar

[15] Saetung A, Rungvichaniwat A, Campistron I, Klinpituksa P, Laguerre A, Phinyocheep P, Pilard J-F. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 117, 1279–1289.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Phinyocheep P, Phetphaisit CW, Derouet D, Campistron I, Brosse JC. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 95, 6–15.10.1002/app.20812Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhang J, Zhou Q, Jiang X-H, Du A-K, Zhao T, van Kasteren JJ, Wang Y-Z. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 1077–1082.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.02.028Search in Google Scholar

[18] Xu P, Li J, Ding J. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 82, 54–59.10.1016/j.compscitech.2013.04.002Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sadaka F, Campistron I, Laguerre A, Pilard J-F. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 816–828.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.01.019Search in Google Scholar

[20] Chaikumpollert O, Sae-Heng K, Wakisaka O, Mase A, Yamamoto Y, Kawahara S. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 1989–1995.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2011.08.010Search in Google Scholar

[21] Phetphaisit CW, Phinyocheep P. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 3546–3555.10.1002/app.12982Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kojima M, Tosaka M, Ikeda Y, Kohjiya S. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 95, 137–143.10.1002/app.20806Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kojima M, Kohjiya S, Ikeda Y. Polymer 2005, 46, 2016–2019.10.1016/j.polymer.2004.12.053Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kojima M, Tosaka M, Ikeda Y. Green Chem. 2004, 6, 84–89.10.1039/b314137cSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Garcia-Serna J, Moreno T, Biasi P, Cocero MJ, Mikkola J-P, Salmi TO. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2320–2343.10.1039/c3gc41600cSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Yi Y, Wang L, Li G, Guo H. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1593–1610.10.1039/C5CY01567GSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Herrero M, Mendiola JA, Ibáñez E. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 5, 24–30.10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.03.008Search in Google Scholar

[28] Pollet P, Davey EA, Urena-Benavides EE, Eckert CA, Liotta CL. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1034–1055.10.1039/C3GC42302FSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Jessop PG, Subramaniam B. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2666–2694.10.1021/cr040199oSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Duereh A, Smith RL. J. Supercrit. Fluids, 2017, doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2017.11.004. (in press).Search in Google Scholar

[31] Pigaleva MA, Elmanovich IV, Kononevich YN, Gallyamov MO, Muzafarov AM. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 103573–103608.10.1039/C5RA18469JSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Hâncu D, Green J, Beckman EJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 757–764.10.1021/ar010069rSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Hâncu D, Green J, Beckman EJ. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 4466–4474.10.1021/ie0108752Search in Google Scholar

[34] Hiraga Y, Sato Y, Smith RL. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 96, 162–170.10.1016/j.supflu.2014.09.010Search in Google Scholar

[35] Liu B, Shi J, Wang M, Zhang J, Sun B, Shen Y, Sun X. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 111, 171–178.10.1016/j.supflu.2015.11.001Search in Google Scholar

[36] Rajagopalan B, Wei M, Musie GT, Subramaniam B, Busch DH. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 6505–6510.10.1021/ie0340950Search in Google Scholar

[37] Nolen SA, Lu J, Brown JS, Pollet P, Eason BC, Griffith KN, Gläser R, Bush D, Lamb DR, Liotta CL, Eckert CA, Thiele GF, Bartels KA. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 316–323.10.1021/ie0100378Search in Google Scholar

[38] Escande V, Petit E, Garoux L, Boulanger C, Grison C. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 2704–2715.10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00561Search in Google Scholar

[39] Cheng L, Wei M, Huang L, Pan F, Xia D, Li X, Xu A. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3478–3485.10.1021/ie403801fSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Ilić L, Jeremić K, Jovanović S. Eur. Polym. J. 1991, 27, 1227–1229.10.1016/0014-3057(91)90059-WSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Chee KK. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1990, 41, 985–994.10.1002/app.1990.070410510Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jeremić K, Ilić L, Jovanović S. Eur. Polym. J. 1985, 21, 537–540.10.1016/0014-3057(85)90077-1Search in Google Scholar

[43] Li S-D, Peng Z, Kong LX, Zhong J-P. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006, 6, 541–546.10.1166/jnn.2006.114Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Kian K, Scurto AM. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 133, 411–420.10.1016/j.supflu.2017.10.030Search in Google Scholar

[45] Baled HO, Gamwo IK, Enick RM, McHugh MA. Fuel 2018, 218, 89–111.10.1016/j.fuel.2018.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[46] Sih R, Foster NR. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 47, 233–239.10.1016/j.supflu.2008.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[47] Sih R, Armenti M, Mammucari R, Dehghani F, Foster NR. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 43, 460–468.10.1016/j.supflu.2007.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[48] Richardson DE, Yao H, Frank KM, Bennett DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1729–1739.10.1021/ja9927467Search in Google Scholar

[49] Iguchi M, Hiraga Y, Kasuya K, Aida TM, Watanabe M, Sato Y, Smith Jr RL. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 97, 63–73.10.1016/j.supflu.2014.10.013Search in Google Scholar

[50] Avelino NT, Fareleira NA, Gourgouillon D, Igreja JM, Nunes da Ponte M. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 128, 300–307.10.1016/j.supflu.2017.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[51] Kravanja G, Knez Ž, KnezHrnčič M. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 139, 72–79.10.1016/j.supflu.2018.05.012Search in Google Scholar

[52] McBride-Wright M, Maitland GC, Trusler JPM. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2015, 60, 171–180.10.1021/je5009125Search in Google Scholar

[53] Kojima M, Ogawa K, Mizoshima H, Tosaka M, Kohjiya S, Ikeda Y. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2003, 76, 957–968.10.5254/1.3547784Search in Google Scholar

[54] Phinyocheep P, Duangthong S. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 78, 1478–1485.10.1002/1097-4628(20001121)78:8<1478::AID-APP30>3.0.CO;2-KSearch in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering