Abstract

The volcanic ash from the Andes mountain range (Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcanic complex situated in western South America on the Argentinean-Chilean border) was used as heterogeneous acid catalyst in the suitable synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines. The natural ashes were classified according to their particle size to generate the different catalytic materials. The catalysts were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), vibrational spectroscopies (FT-IR and Raman), and textural properties were determined by N2 adsorption (SBET). Potentiometric titration with n-butylamine was used to determine the acidic properties of the catalytic materials. Several 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines were obtained by reaction of o-phenylenediamine and substituted 1,3-diphenyl-1,3-propanedione in solvent-free conditions, giving good to excellent yields of a variety benzodiazepines. The method was carried out in environmentally friendly conditions and it was operationally simple. The volcanic ash resulted in a safe and recyclable catalyst.

1 Introduction

In the last three decades, methods based on the use of heterogeneous catalysts have been widely used in laboratory and industrial processes because they play an important role in the current bid for the development of suitable synthetic processes [1].

The requirement of green procedures leads to the use of different environmentally friendly reaction conditions; among them, the substitution/elimination of toxic organic solvents in organic transformations is one of the most important targets in ‘green’ chemistry [2,3]. Formerly, it was thought that a reaction could not be carried out without the presence of a solvent; however, this statement is no longer valid. In fact, many reactions occur more efficiently and selectively than those carried out in the presence of a solvent. Such reactions under solvent-free conditions are simple to handle, comparatively easy to operate, reduce pollution, and are especially important in laboratory research and particularly in the industry [4]. In this context, a particularly important area is the development of suitable synthetic processes in the absence of solvents [1]. Many reports show the efficiency of performing solvent-free reactions, especially in the heterocyclic chemistry synthesis of indoles [5], coumarins [6,7], 2-arylchromone [8], quinoxalines, dipyridophenazines [9], and many others.

The use of reusable solid acid rather than inorganic or organic liquids, such as hydrochloric, sulfuric, p-toluenesulfonic and trichloroacetic acids as catalyst, is another approach to the implementation of green procedures. Numerous inorganic, organic and hybrid materials can catalyze different reactions with several advantages and excellent results [10].

Particularly, the use of clay and related materials as suitable catalysts is a field of increasing worldwide importance. Numerous studies on basic and applied research have been carried out in the last three decades.

The use of clays as solid acid catalysts has aroused great interest because they are noncorrosive, environmentally compatible, inexpensive, nontoxic, and generally allow for simple isolation of reaction products and easy catalyst separation [1,11,12].

There are several reports about the use of clay material in suitable green organic synthesis, e.g., reaction of enaminones, β-ketoesters and ammonium acetate to form pyridines; addition of carbenes to C=N double bonds to produce aziridines; synthesis of methylenedioxyprecocene (MDP), a natural insecticide; solvent-free method for Biginelli reaction under IR irradiation; coumarin-3-carboxylic acids from malonic acid and salicylic aldehydes; furano-/pyrano-quinolines from aryl amines and dihydrofuran/dihydropyran and multicomponent Povarov reaction for the synthesis of quinolones [11]. In this regard, our research group reported the use of bentonite in the benzodiazepine synthesis (acid catalysis) [13] and the selective hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde [14].

Volcanic ashes are particularly amorphous aluminosilicate materials. They are well known and their applications were reported several years ago. Volcanic ashes can be used in abrasives, cleansers, scouring or polishing compounds, concrete admixtures, glazes for pottery, bricks and tiles, glass wool, enamels, lightweight products, fertilizers, asphalt constituents, acoustical tiles, sweeping compounds, paint fillers, insecticide carriers, absorptive packing material, and in the purification of lard and tallow [15]. Some more recent applications of these materials involve their transformation to zeolites and their use as catalyst in different organic reactions on a laboratory and industrial scale [16].

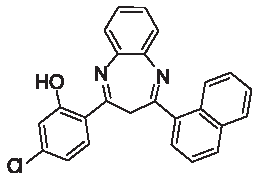

Benzodiazepines are bicyclic compounds that possess a phenyl group fused with a heptagonal heterocyclic ring with two nitrogen atoms in their structure. These compounds have been previously studied due to their pharmacological properties, such as biological activity as anxiolytic, sedative, antidepressant [17], antifungal, and antibacterial agents [18], as insecticides and herbicides [19], and as light-sensitive fibers in photography [20].

Benzodiazepines have been usually synthesized by the condensation of 1,2-phenyldiamines with β-dicarbonyl compounds using different inorganic or organic acid promoters, e.g., polyphosphoric acid [21], acetic acid [22], HY zeolite [23], p-toluenesulfonic acid [24], N-propylsulfamic acid/nanosilica [25], indium tribromide [26], zinc montmorillonite [27], sulfated zirconia [28], MCM-22 zeolite [29], heteropolyacids [30,31], among others [32,33].

In the present paper, we report the treatment, characterization and application as catalysts of volcanic ashes obtained from the Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcanic complex (Argentina-Chile), located at 2236 m above sea level, which is part of the southern Andes system. The last volcanic eruption started on June 4 2011. The dominance of regional “westerly” winds has been responsible for the transport, dispersion and accumulation of tephras along the eastern mountain chain, in Argentine territory. In this context, the volcanic eruption produced large deposits of pyroclastic material in northern Patagonia [34,35].

The catalysts made of selected particle size were characterized by Raman and FT-IR spectroscopies, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) analysis and textural properties (SBET). Acidic properties were determined through potentiometric titration with n-butylamine. We studied the application of these recyclable solid catalysts in a simple, convenient, efficient, and ecofriendly process for the preparation of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines in solvent-free conditions.

2 Experimental

2.1 Catalyst pretreatment

Volcanic ashes from the Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcanic complex (PVA), collected from natural accumulations in S. C. de Bariloche (Río Negro Province, Argentina), were washed with distilled water at room temperature for 72 h, dried and separated according to particle size by sieving. The particle sizes were selected using four mesh sizes: greater than #40 (0.420 mm), #40-60 (0.420-0.250 mm), #60-100 (0.250-0.149 mm) and lower than #100 (0.149 mm)

The systems were named PVA N, where N stands for the mesh size (PVA 40, PVA 40-60, PVA 60-100, and PVA 100). Ashes without any treatment were called natural PVA

Commercial acid catalysts based on natural montmorillonite modified by hydrothermal treatment (K-10 and K-30 from Fluka, general formula (Al4(Si4O10)2(OH)4)) were evaluated for comparison.

2.2 Catalyst characterization

The PVA powder X-ray diffraction patterns were collected with Philips PW-1732 equipment (Cu Kα radiation, Ni filter).

The scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy microanalysis (SEM-EDS) of the materials was performed in a Philips 505 SEM equipped with EDAX 9100.

Textural properties and specific surface area of the PVAs were determined using the Brunauer–Emmett– Teller (BET) multipoint method performed from the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms using Micromeritics ASAP 2020 equipment.

Vibrational FT-IR and Raman spectra of the catalysts were performed with a Thermo Bruker IFS 66 FT-IR (using KBr pellets) and with a Renishaw spectrometer, respectively.

The acid strength and number of acid sites of the solids were determined by potentiometric titration with n-butylamine in acetonitrile. The titration was conducted with 94 Basic Titrino Metrohm equipment using a double junction electrode.

For further details on experimental data, see Supplementary material.

2.3 Catalytic test

All the reactants were provided by Aldrich and used without further refinement. Melting points were measured in open capillary tubes. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on UV-active aluminum-backed plates of silica gel. The nuclear magnetic resonance of 1H and 13C (1H-NMR and 13C-NMR) spectra were determined on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer.

The synthesis of benzodiazepines was achieved by combination of 1,3-diphenyl-1,3-propanedione with the corresponding o-phenyldiamine added to the solid catalyst (1% mmol with respect to dione). The process was conducted at 130°C under magnetic stirring. The pure benzodiazepines were characterized by TLC and physical constants (comparison with standard samples) and by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR analysis.

In order to study the catalyst reusability, after the separation from the reaction media, the catalyst was washed with toluene and dried in vacuum at 80°C up to constant weight. For additional experimental and characterization details, see Supplementary material.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Catalyst characterization

3.1.1 X-ray diffraction

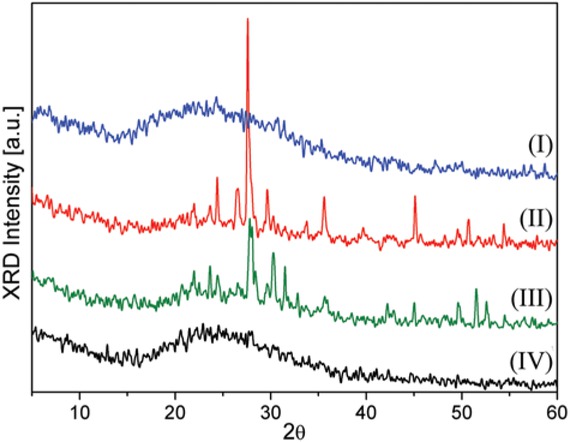

The XRD pattern of the different particle fractions of PVA presented the amorphous phase mainly, with vitreous characteristics as shown in Figure 1 (lines I-IV). Fractions of PVA 40-60 and 60-100 (0.420-0.250 mm and 0.250-0.149 mm respectively) also exhibited the characteristic peaks of crystalline phases (Figure 1, lines II and III) [35], which can be ascribed to the presence of iron oxide phases such as magnetite (PDF 80-0390) and hematite (PDF 89-2810). These phases exhibited their main peaks at 2θ = 30° and 35°. They also presented crystal phases of quartz (PDF 79-1906), plagioclase (CaAl2Si2O8) and pyroxene (Mg2Si2O6) (PDF 89-1463, 85-1740, 88-2377), with their major intensity peaks located about 26.5°, 28° and 30° of 2θ [36,37].

Comparative XRD patterns for catalysts based on volcanic ash materials: (I) PVA 40, (II) PVA 40-60, (III) PVA 60-100, and (IV) PVA 100.

3.1.2 Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy

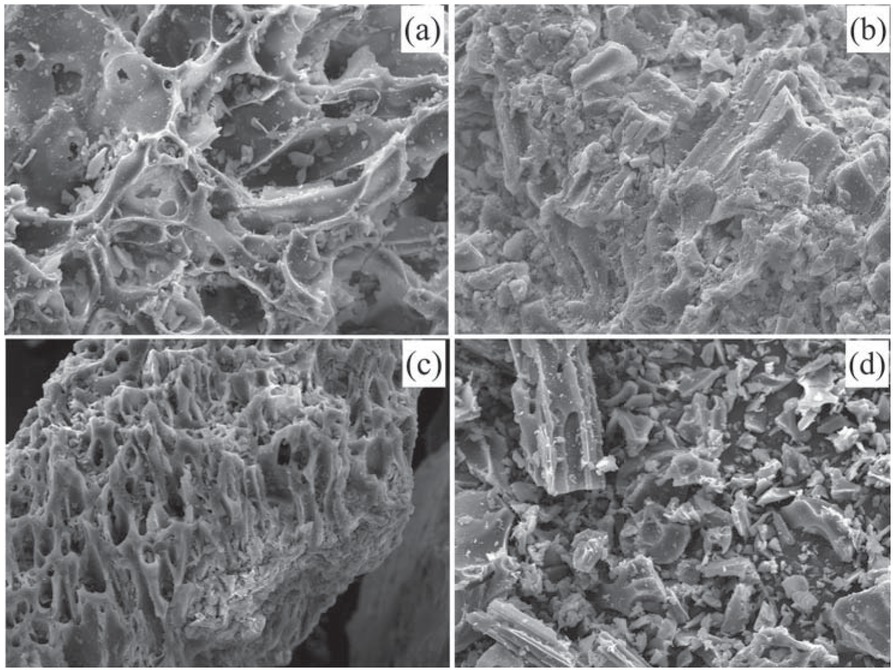

Figures 2a-d show the SEM images of the volcanic pyroclastic material of different fractions. It can be observed that the major component corresponds to pumiceous-type material, dominated by vesiculated particles (cavity formed by entrapment of a gas bubble during solidification) with few connections among the channels and pores.

SEM micrographs of the volcanic ash studied (mag. 500x): (a) PVA 40, (b) PVA 40-60, (c) PVA 60-100, and (d) PVA 100.

SEM-EDS analysis showed the average composition of natural and washed ashes in all systems (Table 1). According to EDS results, the ashes are basically aluminosilicates, the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio in the systems being between 2 and 4. The decrease of Al content can be associated with the enrichment of Si species (crystalline or glassy). Those fractions with a particle size between #40-60 and #60-100 contain about 5% more Fe. This fact suggests the existence of mixed valence iron oxides or related phases (magnetite-type) containing Fe, Mg, Al, and Ti [36,37].

EDS chemical data for the studied ashes and K-materials.

| Element | PVA40 | PVA40-60 | PVA60-100 | PVA100 | Natural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (oxide) | (% m/m) | PVA | |||

| Na2O | 5.4 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 5.2 |

| MgO | 0.2 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Al2O3 | 15.0 | 14.2 | 16.7 | 14.2 | 14.2 |

| SiO2 | 66.3 | 67.0 | 55.3 | 70.1 | 73.2 |

| K2O | 3.9 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| CaO | 2.7 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 2.7 | 1.1 |

| TiO2 | 0.0* | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.0* | 0.3 |

| Fe2O3 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 9.9 | 5.5 | 3.6 |

| Si/Al# | 3.8 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 8.7 |

* not detected by EDS#in atoms

The K-10 and K-30 systems are commercial aluminosilicates based on natural montmorillonite with the general formula (Al4(Si4O10)2(OH)4). They were obtained by acid hydrothermal treatment. EDS chemical data for K-10 and K-30 systems are listed in Table 1. The ratio SiO2/Al2O3 was around 3-4, similar to those found for ashes. Fe, Ti and Mg traces were also found.

3.1.3 Textural properties

A variability of the textural properties in the different fractions of ashes can be observed (Table 2). It was found that the BET area was independent of particle size, except for VPA 60-100 that presented the highest surface area (45 m2/g). The surface area of the rest of the ashes was between 1 and 4 m2/g. In addition, the material presented meso- and macropores (50-500 Å according to IUPAC convention), thus indicating its low overall density [35, 36, 37, 38].

BET and pore data for different fractions of volcanic ashes.

| SBET | Total pore | Pore size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (m2/g) | vol. (cm3/g) | (Å) | |

| PVA 40 | 3.7 | 0.007 | 75.5 |

| PVA 40-60 | 1.4 | 0.005 | 151.0 |

| PVA 60-100 | 45.5 | 0.200 | 191.8 |

| PVA 100 | 2.0 | 0.005 | 106.3 |

| natural PVA | 1.5 | 0.003 | 85.1 |

| K-10 | 225.9 | 0.280 | 50.1 |

| K-30 | 222.9 | 0.340 | 60.2 |

3.1.4 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

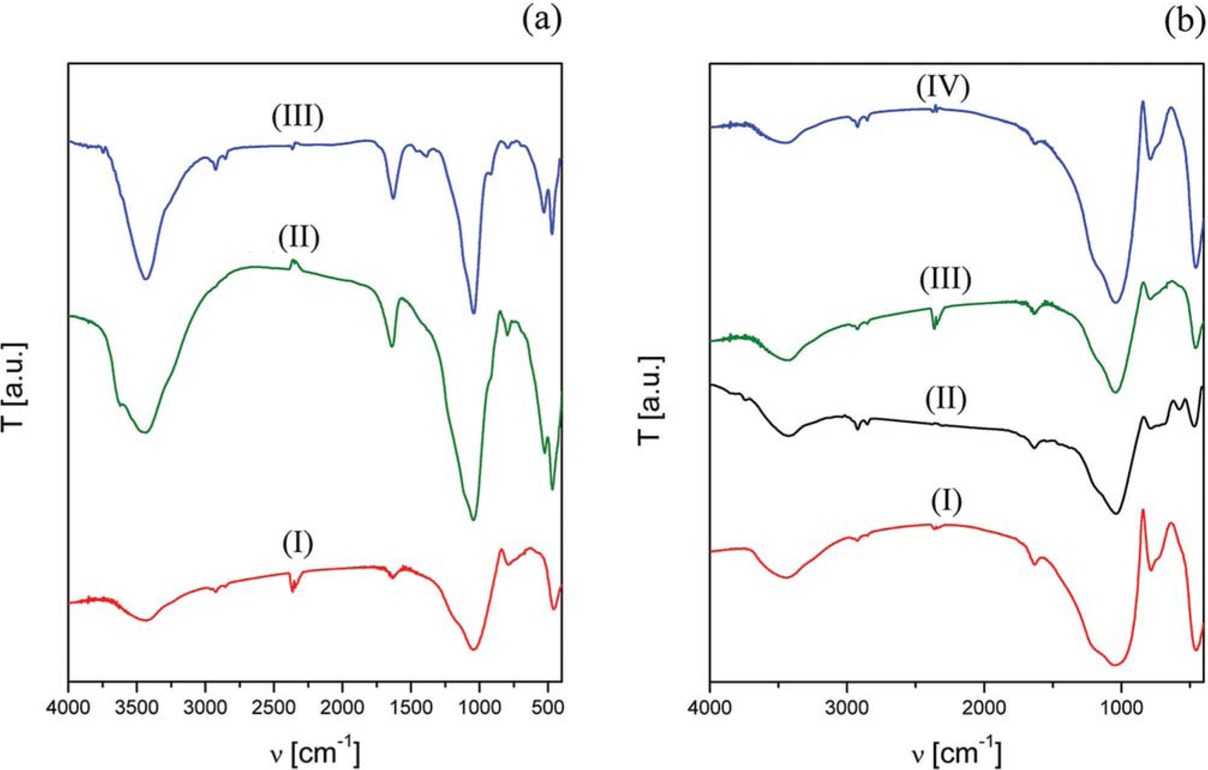

Figure 3 shows the comparative FT-IR spectra of ashes and K systems in the frequency range of 4000 to 400 cm-1. The FT-IR vibrational spectra of PVA systems presented the characteristic signals of aluminosilicates (Figure 3).

FT-IR comparative spectra of: (a) (I) K-10, (II) K-30, and (III) natural volcanic ashes; (b) (I) PVA 100, (II) PVA 40-100, (III) 40-60, and (IV) PVA 40.

The spectral bands around 3450 cm-1 could be attributed to νO-H stretching and those around 1630 cm-1 to the δH-OH; the νs and νas T-O (Si/Al-O) in tetrahedral environment appeared at 1050-1100 and 790 cm-1, respectively, and network stretching modes at 460 cm-1. The broadening of the bands below 1500 cm-1 could be attributed to the coupling between different vibrational modes of the T-O units due to the inherent structural distortion of amorphous systems [37].

The K-10 and K-30 systems also have the characteristic spectrum of aluminosilicates, but in this case the bands are more defined due to their higher crystallinity and more defined structure.

3.1.5 Raman spectroscopy

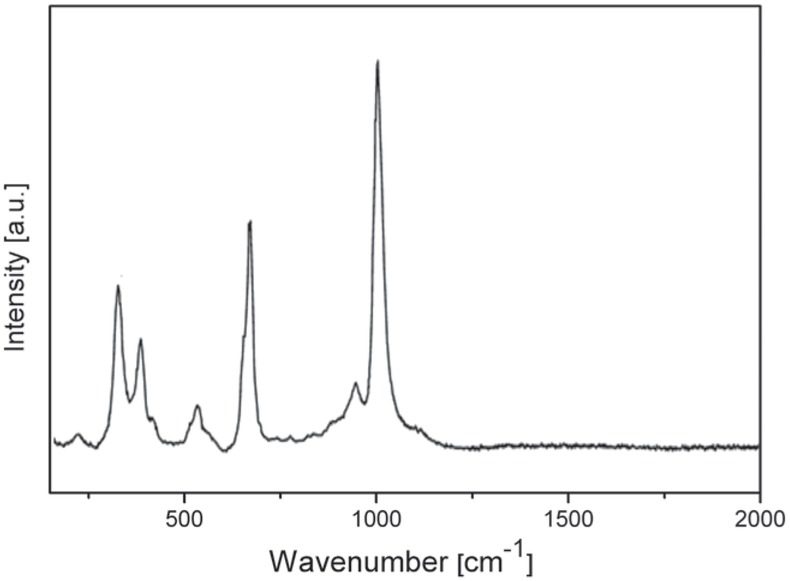

The presence of microcrystals and vitreous particles in the PVA was determined by Raman microprobe spectroscopy [37]. Raman spectroscopy of vitreous materials gave low resolution spectra due to the structural disorder [37]. In Figure 4, the Raman spectrum of a part of the PVA selected under optical microscope presents signals at 999, 664, 325 cm-1, characteristic of pyroxene (997, 667 and 322 cm-1) and a line centered at 530 typical of plagioclase (~510 cm-1) [37]. The Raman spectra of the crystal phases were in concordance with those suggested by XRD.

Raman microprobe spectra for natural PVA.

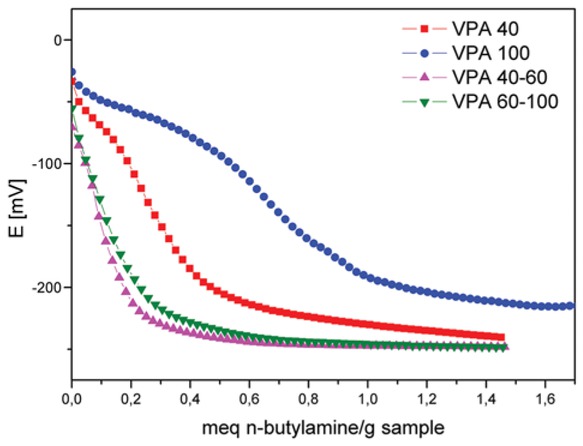

3.1.6 Potentiometric titration

The acidity measurements of the catalysts by means of potentiometric titration with n-butylamine let us estimate the total number of acid sites (where the plateau is reached) and their acid strength (Einitial), Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5, the PVA systems present weak acid sites (Einitial in the range of -70.7 and -25.9 mV). The total number of acid sites is 0.7, 0.55, and 0.65 meq/g of solid for PVA 40, PVA 40-60, and PVA 60-100, respectively, i.e., a small number of acid sites. However, the PVA 100 system presented two types of acid sites: weak and very weak ones corresponding to an Einitial of -25.9 and 88.0 mV, respectively [38].

Potentiometric titration of PVA.

3.2 Catalytic test

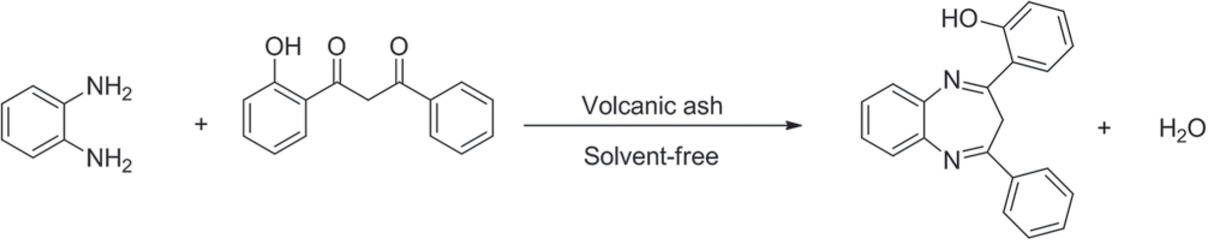

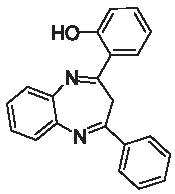

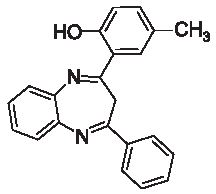

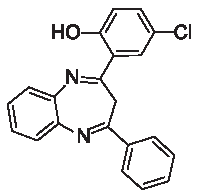

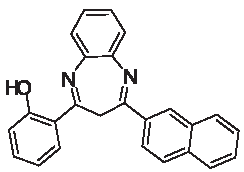

The condensation reaction was initially studied using 1-phenyl-3(2 hydroxyphenyl)-1,3-propanedione and 1,2-phenylendiamine as substrates (Scheme 1). From this point, different reaction conditions were checked, such as temperature, time, molar ratio of reactants, catalyst amount, and catalyst reusability. The reaction conditions were: 130°C, 10 min, under solvent-free conditions using a 1:1 molar ratio of substrates.

Scheme of reaction.

In a blank experiment, without the presence of catalyst, no products were detected by TLC, indicating that the presence of a catalyst is necessary (Table 3, entry 8). Commercial clays Montmorillonite K-10 and Montmorillonite K-30, tested for comparison purposes (Table 3, entries 1 and 2), yielded conversions of 48% and 55% with a benzodiazepine selectivity of 79% and 84%, respectively. In both cases, the yields of pure benzodiazepine were 38% and 46% respectively.

Catalyst effect.

| Entry | Catalyst | Conv | Benzodiazepine selectivity | Other selectivity | Yield pure benzodiazepine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| 1 | Montmorillonite K-10 | 48 | 79 | 10 | 38 |

| 2 | Montmorillonite K-30 | 55 | 84 | 9 | 46 |

| 3 | Natural PVA | 57 | 77 | 13 | 44 |

| 4 | PVA 40 | 51 | 80 | 10 | 41 |

| 5 | PVA 40-60 | 58 | 83 | 10 | 48 |

| 6 | PVA 60-100 | 64 | 86 | 9 | 55 |

| 7 | PVA 100 | 58 | 81 | 11 | 47 |

| 8 | No Catalyst | 0 | – | – | – |

Results of catalytic tests in solvent-free conditions with different ashes as catalysts are summarized in Table 3 (entries 3-7). There is an apparent increase in the reaction yields for three PVA catalysts compared to the natural PVA (44%, Table 3, entry 3); PVA 40-60 (58%, Table 3, entry 4), PVA 60-100 (64%, Table 3, entry 6), and PVA 100 (58%, Table 3 entry 7). In all cases, benzodiazepine selectivity was high, between 82% and 89% (Table 3, entries 1-7). The system that showed the best catalytic performance was PVA 60-100, that with the highest Fe and Ti content and with the largest pore size (Tables 1 and 2). So, the catalytic activity is related to the Fe and Ti content, which could be ascribed to the larger number of Lewis acid sites given by the presence of Fe and Ti and greater availability of active sites due to larger pore size.

The effect of reaction time on reaction yields at the selected temperature of 130°C was also tested at four different times: 10, 20, 30 and 40 min (Table 4). An excellent yield was obtained at 20 min of reaction (86%, Table 4, entry 2), without any variation at longer reaction times such as 40 min (84%, Table 4, entry 4). In all cases, the selectivity ranged between 83% and 91%.

Time effect for PVA 60-100.

| Entry | Time (min) | Conv. (%) | Benzodiazepine selectivity | Other selectivity | Yield pure benzodiazepine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

| 1 | 10 | 64 | 86 | 9 | 55 |

| 2 | 20 | 95 | 91 | 9 | 86 |

| 3 | 30 | 96 | 88 | 12 | 84 |

| 4 | 40 | 96 | 83 | 17 | 80 |

The influence of temperature on the production of benzodiazepine 3a (3H-2,4-diphenyl-1,5-benzodiazepine) was investigated with experiments performed at 80, 100, 130 and 140°C (Table 5). The best yield was obtained at 130°C (86%, Table 5, entry 4) with a selectivity of 91%. No reaction was detected when the test was performed at 80°C (Table 5, entry 1). When the temperature was increased to 140°C, a conversion of 100% was obtained; however, the selectivity was very low, and several unidentified secondary products were detected by TLC.

Temperature effect for PVA 60-100.

| Entry | Temperature | Conv | Benzodiazepine | Other | Yield pure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (%) | selectivity | selectivity | benzodiazepine | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

| 1 | 80 | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 100 | 33 | 90 | 10 | 30 |

| 3 | 130 | 95 | 91 | 9 | 86 |

| 4 | 140 | 100 | 68 | 32 | 68 |

Another key factor to optimize the reaction conditions is the molar ratio of reactants. Table 6 lists the results

Effect of substrate molar ratio for PVA 60-100.

| Entry | Molar ratio dione/diamine | Conv | Benzodiazepine selectivity | Other selectivity | Yield pure benzodiazepine pure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| 1 | 1:1 | 95 | 91 | 9 | 86 |

| 2 | 1:1.5 | 100 | 92 | 8 | 92 |

| 3 | 1:2 | 100 | 89 | 11 | 89 |

| 4 | 1:3 | 100 | 85 | 15 | 85 |

obtained with different proportions of the reactants using the previously defined optimal temperature (130°C) and time (20 min). Equimolar quantities gave a good yield; an excess of o-phenyldiamine improved the yield, while a ratio 1:1.5 of o-phenyldiamine/1-phenyl-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,3-propanedione gave the best performance (92%, Table 6, entry 2), with a selectivity of 92%. An increase of molar ratio to 2:1 or 3:1 decreased the selectivity, and unidentified secondary products were detected by TLC.

Under the optimal conditions determined (solvent-free, a reactant molar ratio of 1:1.5 at 130°C for 20 min of reaction) the PVA 60-100 catalyst was tested as a function of its mass. The results listed in Table 7 show that 50 mg of the PVA 60-100 catalyst gives the best yield (92%, Table 7, entry 2), and no additional amount of catalyst is required to improve it.

Catalyst amount effect.

| Entry | Catalyst amount | Conv | Benzodiazepine selectivity | Other selectivity | Yield pure benzodiazepine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| 1 | 25 | 75 | 93 | 7 | 70 |

| 2 | 50 | 100 | 92 | 8 | 92 |

| 3 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 10 | 90 |

| 4 | 200 | 100 | 90 | 10 | 90 |

The catalyst reusability in the reaction was studied in the same conditions and proportions as for natural PVA (in solvent-free conditions, at 130°C, 1:1.5 dione/diamine ratio and 50 mg of PVA 60-100 catalyst), at five consecutive times of reaction. The used catalyst was separated from the reaction media, washed with toluene and dried in vacuum to recover it. The results showed no considerable variations in the reaction performance (Table 8) when the catalyst was reused five consecutive times.

Catalyst reuse.

| Entry | Cycle | Yield pure benzodiazepine | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Use | 92 | |

| 2 | 1st Reuse | 90 | |

| 3 | 2nd Reuse | 90 | |

| 4 | 3rd Reuse | 88 |

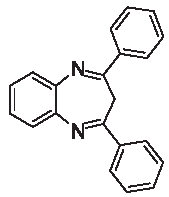

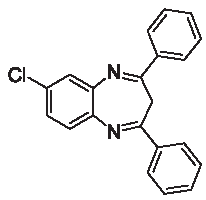

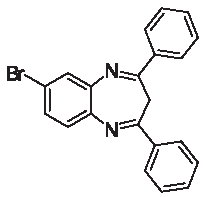

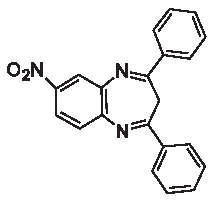

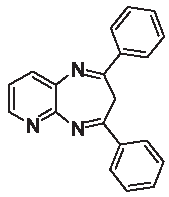

According to the good results achieved for experiments under solvent-free reaction conditions, involving 50 mg of catalyst at 130°C and 20 min reaction time (hereafter denoted as optimal conditions), several reactions were

carried out using different 1,3-diones and 1,2-diamines. The corresponding benzodiazepines were obtained in very good yields as indicated in Table 9 (entries a to d and g). However, phenylenediamine containing nitro group or nitrogen in their structure does not react under the established reaction conditions, probably due to the decrease in the nucleophilicity of amino groups present in the reagent.

Yield and Green Metric Parameters for the different substituted 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines obtained.

| Compounds | Product | Yield (%) | Green Metric Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE % | PMI | E Factor | ||||

| 3a |  | [39] | 61 | 89.2 | 2.41 | 1.41 |

| 3b |  | [30] | 91 | 89.6 | 1.62 | 0.62 |

| 3c |  | [30] | 82 | 90.2 | 1.80 | 0.80 |

| 3d |  | [30] | 78 | 91.2 | 1.90 | 0.90 |

| 3e |  | – | – | 89.2 | – | – |

| 3f |  | – | – | 90.5 | – | – |

| 3g |  | [40] | 92 | 89.7 | 1.57 | 0.57 |

| 3h |  | [40] | 73 | 90.1 | 1.96 | 0.96 |

| 3i |  | [40] | 79 | 90.6 | 1.78 | 0.78 |

| 3j |  | [40] | 63 | 91.0 | 2.20 | 1.20 |

| 3k |  | [30] | 79 | 91.7 | 1.71 | 0.71 |

The workup and catalyst recovery are simple, and all reactions have very high selectivity toward the corresponding benzodiazepines. The TLC analysis shows small amounts of by-products. The products are known compounds and were characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy. The NMR characterization details of all compounds are shown in Supplementary material.

4 Conclusion

In this article, we present the treatment and characterization of volcanic ashes obtained from the Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcanic complex. The volcanic ashes were

characterized by Raman and FT-IR spectroscopy, XRD, SEM, and BET. The acidic strength of the catalysts was determined by potentiometric titration with n-butylamine. Substituted 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines were synthesized from 1,3-propanediones and 1,2-phenylendiamine, under solvent-free reaction conditions, using volcanic ashes as catalysts. This procedure allows obtaining good to excellent performance of the derivatives in a short reaction time of approximately 20 min, and a temperature of 130°C. The volcanic ash catalysts are insoluble in organic solvent, which allows easy removal of the reaction products without affecting their catalytic activity.

Different PVA fractions were comparable from the viewpoint of spectroscopic, textural and acidity characteristics. The PVA system that showed the best catalytic performance was that with higher Fe content and larger total number of acid sites.

The applications of these catalysts in oxidation reactions and biomass valorization through a multicomponent reaction are in progress in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank G. Valle for FT-IR spectra, M. Theiller for the SEM analysis, E. Soto and Pablo Fetsis for SBET data, and F. Ziarelli for 31P-NMR spectra.

Funding sources: This work was supported by “Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas” (CONICET - PIP 003), “Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica” (ANPCyT - PICT 0409), “Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas de la Prov. de Bs. As.” (CICPBA - Project 832/14) and Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Project I11/172). MM, AGS, and GPR are members of CONICET. CIC is a member of CIC-PBA and Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

References

[1] Rocchi D., González J.F., Menéndez J.C., Montmorillonite Clay-Promoted, Solvent-Free Cross-Aldol Condensations under Focused Microwave Irradiation. Molecules, 2014, 19, 7317-7326.10.3390/molecules19067317Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Capello C., Fischer U., Hungerbühler K., What is a green solvent? A comprehensive framework for the environmental assessment of solvents. Green Chem., 2007, 9, 927-934.10.1039/b617536hSearch in Google Scholar

[3] Kerton F.M., Marriott R., Alternative Solvents for Green Chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry Publishing, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Himaja M., Poppy D., Asif K., Green technique-solvent free synthesis and its advantages. Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm., 2011, 2(4), 1079-1086.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sayyed-Alangi S.Z., Hossaini Z., ZnO nanorods as an efficient catalyst for the green synthesis of indole derivatives using isatoic anhydride. Chem. Heterocyc. Compd., 2015, 51, 541-544.10.1007/s10593-015-1734-1Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zolfigol M., Ayazi-Nasrabadi R., Baghery S., Synthesis and characterization of two novel biological-based nano organo solid acids with urea moiety and their catalytic applications in the synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol), coumarin-3-carboxylic acid and cinnamic acid derivatives under mild and green conditions. RSC Adv., 2015, 5(88), 71942-71954.10.1039/C5RA14001CSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Atghia S.V., Beigbaghlou S.S., Use of a highly efficient and recyclable solid-phase catalyst based on nanocrystalline titania for the Pechmann condensation. C. R. Chim., 2014, 17, 1155-1159.10.1016/j.crci.2014.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[8] Perez M., Ruiz D., Autino J., Sathicq A.G., Romanelli G.P., A very simple solvent-free method for the synthesis of 2-arylchromones using KHSO4 as a recyclable catalyst. C. R. Chim., 2016, 19, 551-555.10.1016/j.crci.2016.02.014Search in Google Scholar

[9] Krishnakumar B., Swaminathan M., Solvent free synthesis of quinoxalines, dipyridophenazines and chalcones under microwave irradiation with sulfated Degussa titania as a novel solid acid catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem., 2011, 350, 16-25.10.1016/j.molcata.2011.08.026Search in Google Scholar

[10] Clark J.H., Solid Acids for Green Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res., 2002, 35, 791-797.10.1021/ar010072aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Nagendrappa G., Organic synthesis using clay and clay-supported catalysts. Appl. Clay Sci., 2011, 53, 106-138 (and the references cited herein).10.1016/j.clay.2010.09.016Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kaur N., Kishore D.V., Montmorillonite: An efficient, heterogeneous and green catalyst for organic synthesis. J. Chem. Pharm. Res., 2012, 4, 991-1015.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Muñoz M., Sathicq A.G., Romanelli G.P., Hernández S., Cabello C.I., Botto I.L., et.al., Porous modified bentonite as efficient and selective catalyst in the synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepines. J. Porous Mat., 2013, 20, 65-73.10.1007/s10934-012-9575-0Search in Google Scholar

[14] Bertolini G.R., Vetere V., Gallo M.A., Muñoz M., Casella M.L., Gambaro L., et al., Composites based on modified clay assembled Rh(III)–heteropolymolybdates as catalysts in the liquid-phase hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde. C. R. Chim., 2016, 19, 1174-1183.10.1016/j.crci.2015.09.015Search in Google Scholar

[15] Manz O.E., Investigation of pozzolanic properties of the Cretaceous volcanic ash deposit near Linton: North Dakota Geological Survey Report of Investigation. J. W. Acad. Sci., 1962, 38(7), 80.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Suib Newnes S.L., New and future developments in catalysis: hybrid materials, composites, and organocatal (1st ed.). Elsevier, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Abdollahi-Alibeik M., Mohammadpoor-Baltork I., Zaghaghi Z., Yousefi B.H., Efficient synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepines catalyzed by silica supported 12-tungstophosphoric acid. Catal. Commun., 2008, 9, 2496-2502.10.1016/j.catcom.2008.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jadhav K.P., Ingle D.B., Synthesis of 2,4-diaryl-2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines and their 1,1-dioxides as antibacterial agents. Indian J. Chem., 1983, B22, 180-182.10.1002/chin.198333256Search in Google Scholar

[19] Reddy R.J., Ashok D., Sharma P.N., Synthesis of 4,6-bis(2´-substituted-2′,3′-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepin-4′-yl)resorcinols as potential antifeedants. Indian J. Chem., 1993, B32, 404-406.10.1002/chin.199325202Search in Google Scholar

[20] Rodriguez R., Insusti B., Abonía R., Quiroga J., Preparation of some light-sensitive 2-nitrophenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzodiazepines. Arkivoc, 2004, 13, 67-71.10.3998/ark.5550190.0005.d08Search in Google Scholar

[21] Jung D., Song J., Kim Y., Lee D., Lee Y., Park Y., et al., Synthesis of 1H-1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives and pyridinylquinoxalines with heterocyclic ketones. B. Korean Chem. Soc., 2007, 28(10), 1877-1880.10.5012/bkcs.2007.28.10.1877Search in Google Scholar

[22] Pozarentzi M., Stephanidou-Stephanatou J., Tsoleridis C.A., An efficient method for the synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives under microwave irradiation without solvent. Tetrahedron Lett., 2002, 43, 1755-1758.10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00115-6Search in Google Scholar

[23] Jeganathan M., Pitchumani K., Solvent-Free syntheses of 1,5-Benzodiazepines using HY Zeolite as a green solid acid catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., 2014, 2, 1169-1176.10.1021/sc400560vSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Pasha M.A, Jayashankara V.P., An expeditious Synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives catalyzed by p-toluensulfonic acid. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 2006, 1, 573-578.10.3923/jpt.2006.573.578Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tarannum S., Siddiqui Z., Nano silica-bonded N-propylsulfamic acid as an efficient and environmentally benign catalyst for the synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepines. Monatsh Chem., 2017, 148(4), 717-730.10.1007/s00706-016-1775-xSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Yadav J.S., Reddy B.V.S., Praveenkumar S., Nagaiah K., Indium(III) Bromide: A novel and efficient reagent for the rapid synthesis of 1,5-Benzodiazepines under solvent-free conditions. Synth., 2005, 3, 480-484.10.1055/s-2004-834939Search in Google Scholar

[27] Varala R., Enugala R., Adapa S.R., Zinc montmorillonite as a reusable heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives. Arkivoc, 2006, 13, 171-177.10.3998/ark.5550190.0007.d18Search in Google Scholar

[28] Reddy B.M., Sreekanth P.M., An efficient synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives catalyzed by a solid superacid sulfated zirconia. Tetrahedron Lett., 2003, 44, 4447-4449.10.1016/S0040-4039(03)01034-7Search in Google Scholar

[29] Majid S.A., Khanday W.A., Tomar R., Synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine and its derivatives by condensation reaction using H-MCM-22 as catalyst. J. Biomed. Biotechnol., 2012.10.1155/2012/510650Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Pasquale G.A., Ruiz D., Jios J.L., Autino J.C., Romanelli G.P., Preyssler catalyst-promoted rapid, clean, and efficient condensation reactions for 3H-1,5-benzodiazepine synthesis in solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett., 2013, 54(48), 6574-6579.10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.09.101Search in Google Scholar

[31] Pasquale G., Ruiz D., Baronetti G., Thomas H., Autino J., Romanelli G.P., Wells-Dawson type catalyst: An efficient, recoverable and reusable solid acid catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of benzodiazepines. Curr. Catal., 2014, 3(2), 229-233.10.2174/2211544702666131224003128Search in Google Scholar

[32] Willy B., Dallos T., Rominger F., Schönhaber J., Müller T.J.J., Three‐ component synthesis of cryofluorescent 2,4‐disubstituted 3H‐1,5‐benzodiazepines – conformational control of emission properties. Eur. J. Org. Chem., 2008, 4796-4805.10.1002/ejoc.200800619Search in Google Scholar

[33] Young J., Schäfer C., Solan A., Baldrica A., Belcher M., Nişanci B., et al., Regioselective “hydroamination” of alk-3-ynones with non-symmetrical o-phenylenediamines. Synthesis of diversely substituted 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines via (Z)-3-amino-2-alkenones. RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 107081-107093.10.1039/C6RA24291JSearch in Google Scholar

[34] Special reports of volcanic activity Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcanic complex. SERNAGEOMIN, 2011, http://www.sernageomin.cl/Search in Google Scholar

[35] Botto I.L., Barone V., Canafoglia M.E., Rovere E., Violante R., González M.J., et al., Pyroclasts of the first phases of the explosive-effusive PCCVC volcanic eruption: physicochemical analysis. Mater. Phys. Chem., 2015, 5(8), 302-315.10.4236/ampc.2015.58030Search in Google Scholar

[36] Canafoglia M.E., Vasallo M., Barone V., Botto I.L., Problems associated to natural phenomena: potential effects of PCCVC eruption on the health and the environment in different zones of Villa La Angostura, Neuquen, Argentina. In: Proceedings of AUGM-DOMUS (2012, La Plata, Argentina). La Plata, Bs. As., Argentina, 2012, 4, 1-11.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Botto I.L., Canafoglia M.E., Gazzoli D., González M.J., Spectroscopic and microscopic characterization of volcanic ash from Puyehue-(Chile) eruption: Preliminary approach for the application in the arsenic removal. J. Spectrosc., 2013, ID-254517, DOI:10.1155/2013/254517.10.1155/2013/254517Search in Google Scholar

[38] Villabrille P., Vázquez P., Blanco M., Cáceres C., Equilibrium adsorption of molybdosilicic acid solutions on carbon and silica: basic studies for the preparation of ecofriendly acidic catalysts. J. Colloid Interf. Sci., 2002, 251, 151-159.10.1006/jcis.2002.8391Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Tsoleridis C., Pozarentzi M., Mitkidou S., Stephanidou-Stephanatou J., An experimental and theoretical study on the regioselectivity of successive bromination sites of 7,8-dimethyl-2,4-diphenyl-3H-1,5-benzodiazepine. Efficient microwave assisted solventless synthesis of 4-phenyl-3H-1,5-benzodiazepines. Arkivoc, 2008, xv, 193-209.10.3998/ark.5550190.0009.f18Search in Google Scholar

[40] Ahmad R., Zia-Ul-Haq M., Hameed S., Nadeem H., Duddeck H., Synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine nucleosides. J. Chem. Soc. Pakistan, 2000, 22, 302-308.Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Muñoz et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering