Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

-

Esam M. Aboubakr

, Abeer S. Hassan

Abstract

A new formulation (niosomes) was prepared to enhance the bioavailability, hepatic tissue uptake, and hepatoprotective activity of glutathione (GSH). The GSH-loaded niosomes (nanoform, N-GSH) were formulated by the thin-film hydration technique using cholesterol/non-ionic surfactants (Span®40, Span®60, and Tween®80) at a componential ratio of 1:1 and 2:1. The hepatoprotective activity of N-GSH, GSH, and the standard silymarin against CCl4-induced liver damage and oxidative stress were tested on the rats’ model. The hepatic morphology and histopathological characters were also investigated. The tissue contents of N-GSH were analysed using a concurrently validated RP-HPLC method. The optimized niosomes, composed of glutathione (500 mg), cholesterol, and Span®60-Tween®80 at a molar ratio of 2:1 of cholesterol/non-ionic surfactant, displaying a particle size of 688.5 ± 14.52 nm, a zeta potential of −26.47 ± 0.158 mV, and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of 66 ± 2.8% was selected for in vivo testing. The levels of MDA, NO, SOD, NF-κB, IL-1β, and Bcl-2 were measured. The results demonstrated that hepatic tissue damage was ameliorated using N-GSH as confirmed by the morphological and histopathological examination compared to the CCl4 and control groups. The N-GSH significantly (p < 0.05) decreased the elevated levels of hepatic enzymes, oxidative parameters, and inflammatory mediators, as compared to silymarin and GSH. Also, N-GSH significantly (p < 0.05) increased GSH hepatocyte concentrations as compared to the control groups. The present study demonstrated that N-GSH remarkably improved glutathione oral bioavailability and hepatic tissue uptake, thereby introducing a new glutathione formulation to protect hepatic tissue from injury and restore its GSH contents.

1 Introduction

Liver-associated illnesses remain a global health concern. These diseases are considered to be the leading cause of mortality among populations of low- to middle-income Asian and African countries [1]. The liver is highly susceptible to oxidative stress, inflammation, and degeneration since it is the main organ responsible for the metabolism and detoxification of nutrients/drugs [2]. Several physiological and pathological processes in human and animal cells, e.g. gene expression, signal transduction, growth, and even death, are associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [3]. However, excessive ROS are implicated in soft-tissue degeneration, cancer, neurodegenerative, cardiovascular diseases, cellular damage, and death [4].

The protective antioxidant mechanisms and a number of antioxidant systems are conspicuous in the biological systems that are involved in the free radicals capture/neutralization and thereby performing cellular protection [5]. Two antioxidant protective systems are available in the human body, i.e. enzymatic antioxidants and non-enzymatic antioxidants. The first system includes several enzymes, e.g. glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (CAT), which combats free radical formation and neutralize their harmful effects [6]. The second antioxidant system, non-enzymatic antioxidants, includes compounds such as glutathione, coenzyme Q10, melatonin, thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, and lipoic acid, produced as endogenous metabolic products, contributes to cellular protection against excessive ROS [5]. In addition, nutrients such as greens, fruits, vitamin E, and vitamin C-rich foods are also supportive materials used as protective antioxidant nutraceuticals [7].

Glutathione (GSH) is the predominant non-enzymatic thiol antioxidant in cells with a primary role in scavenging the free radicals. GSH is present in the cytosol and other cell structures, such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and nuclear matrices [8]. Also, all the cells can biosynthesize GSH; however, hepatocytes are the main exporting source [8]. The oxidized glutathione, glutathione disulphide (GS-SG), produced from the reaction of GSH with free radicals, further undergoes the enzymatic reduction process by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent glutathione reductase to regenerate the glutathione (GSH) in a reduced form [9]. Other roles of GSH, i.e. in the regeneration of disulphide bonds of proteins, as co-factor for detoxifying the enzymes, and lessening a load of electrophiles and oxidants as a result of the presence of cysteine in the GSH structure, have also been also reported [10]. Therefore, the cells’ ability to combat free radicals is directly affected by the GSH/GS-SG, and to a lesser extent, to the ratio of other redox couples, e.g. NADPH/NADP+ and thioredoxinred/thioredoxinox [9,11]. The factors affecting GSH levels in the plasma have also been reported in the literature. For instance, the levels of GSH normally decrease with age and could be pathologically depleted due to several physiological malfunctioning in response to diseases, e.g. neurodegenerative [12], pulmonary, hepatic [13], immune, and cardiovascular disorders [14].

The GSH bioavailability through the oral route is poor as it is degraded by the intestinal enzyme, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, leading to its lowered absorption from gout [15]. In addition, GSH also has a short half-life of ∼2.5 min in the blood [16]. Therefore, the oral formulations of glutathione that withstand the gastrointestinal environment and degradation are imperative in nature and are in demand to overcome these shortcomings. Different approaches have been adopted to improve the GSH bioavailability through the oral route by different novel formulations, and in this context, the nanoformulations have taken the lead. The GSH encapsulating chitosan nanoparticles [17] and Eudragit VR RS 100/cyclodextrin material-based formulations [16] have been prepared. Also, the mucoadhesive polymer-based film for GSH was formulated [18]. The appropriate liposomal nanovesicles formulation that may enhance the bioavailability and stability of the GSH component and reduce the dosing frequency of GSH has also been proposed. The phospholipid bilayer composition of liposomes has a similar structure to that of the cell membranes, which enhanced the entrapped/core drugs, e.g. the bioavailabilities of peptides and proteins [19]. However, drug leakage, phospholipid hydrolysis, phospholipid oxidation, sedimentation, and particles aggregation are common drawbacks and stability shortcomings of the liposomal preparations [20,21]. Therefore, alternative non-ionic surfactant nanovesicles (niosomes) have been proposed and are currently developed to overcome the stability shortcomings of the liposomes. Niosomes are vesicular bilayer structures of non-ionic surfactants and cholesterol that self-assemble spontaneously on hydration with aqueous media. Niosomes are also better candidates for drug delivery than liposomes owing to their lower costs and higher stability. In addition, the niosomes have better resistance to hydrolysis and oxidation during storage. Drug solubility and stability enhancements are also added advantages for the niosomes formulations. The drug’s permeation and bioavailability have also been widely explored as advantages of the niosomes formulations when delivered through various routes of administration [22]. These nanovesicles, the niosomes, are comparatively thermodynamically more stable than the liposomes, thereby adjusting the process temperature above the gel/liquid transition of the main lipid composition through the use of suitable mixtures of the surfactants and a proper stabilizer, i.e. cholesterol, in the formulation of niosomes. By considering the parameters of componential ratios of the ingredients, the nature of the surfactant, temperature, and the stabilizer, the prepared nanovesicles are considered to be suitable for use as a targeted carrier for controlled release of the dosage form for the lipophilic and hydrophilic drugs [23].

The current study was designed to develop and evaluate various formulations of the GSH-loaded niosomes prepared with different non-ionic surfactants to enhance the stability of the GSH, and bioavailability of the GSH-loaded formulations when administered through the oral route. The GSH-nanovesicles (n-GSH) formulated through the thin-film hydration method and characterized in terms of their particle size, zeta potential, and entrapment efficiency (EE). Furthermore, the biological evaluations of the N-GSH as a liver-protecting agent against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury in comparison to silymarin and GSH were performed. GSH concentrations in the liver tissue homogenates of the injured and treated animals were assayed. The intracellular redox status and oxidative stress conditions were also evaluated by measuring the malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, anti-oxidant enzyme activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD) reactivity, and the serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor TNF-α, IL-6, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and nitric oxide (NO) status. A histopathological examination for hepatic tissues of the normal, injured, and treated animals were also performed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Cholesterol, silymarin, and glutathione were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO, USA. Span®20, Span® 40, Span® 60, Span® 80, Tween® 20, Tween® 40, Tween® 60, Tween® 80, and propylene glycol were purchased from Adwic, El-Naser Chemical Co., Egypt. The HPLC-grade chloroform, methanol, acetonitrile, and analytical-grade sodium acetate, disodium hydrogen phosphate, CCl4, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and diethyl ether were purchased from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany. Ultra-pure water was obtained from the Milli-Q Plus® water purification system (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). The standard solution of GSH was prepared by dissolving 50 mg/L GSH in 10 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) to prevent oxidation by trace metals. The standard working solution was prepared through dilutions with the HPLC mobile phase.

2.2 Preparation of glutathione-loaded niosomes

Glutathione-loaded-niosomes were prepared using the thin-film hydration method with different mixtures of cholesterol and non-ionic surfactants at molar ratios of 1:1 and 2:1 [24]. A 500 µmol of non-ionic surfactants mixture (Span® 40 and Span® 60: Tween® 80) and cholesterol were dissolved in a chloroform/methanol mixture (2:1 v/v) in a round bottom flask. Organic solvents were evaporated (15 min at 55°C, 900 rpm) using a rotary evaporator (Buchi 200, BU¨CHI Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). The resultant film that formed in the bottom of the rounded flask was hydrated by gently shaking it for 45 min at 55°C with distilled water containing 250 mg and 500 mg of GSH. The developed niosomal dispersion was stored at 4°C for further study. The compositions of different niosomal formulations are summarized in Table 1.

Composition of glutathione-loaded niosomes prepared with 1:1 and 2:1 molar ratios of cholesterol and non-ionic surfactant mixture (Span 40® and span 60®: Tween 80®)

| Formulation | GSH (mg) | Cholesterol (µmol) | Span 40® (µmol) | Span 60® (µmol) | Tween 80® (µmol) | EE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTN1 | 250 | 250 | 125 | — | 125 | 35 ± 3.6 |

| GTN2 | 250 | 250 | — | 125 | 125 | 45 ± 1.6 |

| GTN3 | 250 | 335 | 82.5 | — | 82.5 | 53 ± 1.6 |

| GTN4 | 250 | 335 | — | 82.5 | 82.5 | 65 ± 2.5 |

| GTN5 | 500 | 250 | 125 | — | 125 | 47 ± 2.2 |

| GTN6 | 500 | 250 | — | 125 | 125 | 54 ± 2.7 |

| GTN7 | 500 | 335 | 82.5 | — | 82.5 | 60 ± 1.4 |

| GTN8 | 500 | 335 | — | 82.5 | — | 66 ± 2.8 |

2.3 RP-HPLC analytical procedure

Agilent 1260 Infinity® HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Germany), used for the method development, consisted of an Agilent 1260 Infinity® binary solvent pump, thermostat column, autosampler, and Agilent 1260 Infinity® Diode array detector. The output signals were monitored and processed using OpenLAB CDS ChemStation® software. All the solutions were degassed by ultrasonication (Power-Sonic 420, Labtech, Korea) and filtered through a 0.45 µm Nylon filter (PALL Life Sciences, USA). GSH concentrations were determined using the method explained by Tsiasioti et al. [25], with certain modifications. At 30°C, isocratic separation was carried out on Pursuit-3® C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm i.d. and 3 µm particle size, Agilent Technologies, Netherland) using a mobile phase prepared by mixing 10% methanol and 90% 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The injected volume of the standard solution was 20 µL, and detected with a UV spectrophotometer at 210 nm. Various chromatographic conditions were tested, optimized, and validated according to ICH guidelines for use [26].

2.4 Characterization of glutathione-loaded niosomes

2.4.1 Evaluation of the vesicle size and zeta potential

An average diameter of N-GSH (GSH-loaded niosomes, z-average) and polydispersity index (PDI) of all the formulations were measured at 25°C by the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method utilizing the Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS® instrument (Malvern Instruments, UK) equipped with a backscattered light detector operating at 173°. Before each measurement, the niosomal dispersion was diluted (20×) with double-distilled water. The zeta potential of the vesicles was estimated by laser Doppler anemometry using a Malvern Zetasizer ZS®. All the measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4.2 Entrapment efficiency

The EE of the GSH into the N-GSH niosomes was estimated indirectly by measuring the free drug (GSH) in the supernatant of the hydrated N-GSH preparation using the developed RP-HPLC method. The unentrapped drug was separated from drug-loaded niosomes by centrifugation at 4°C, 14,000 rpm, for 60 min, using a bench-top refrigerated centrifuge (Centurion Scientific Ltd, Sussex, UK). The obtained niosomes pellets were reconstituted in distilled water and washed twice using the same procedures. The EE (in percentage) was calculated according to the following equation:

where T is the initial total amount of drug added and C is the free unentrapped drug in the supernatant. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.4.3 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The niosomal dispersion of GSH was diluted (10×) using distilled water. A diluted GSH vesicle dispersion drop was applied to a carbon-coated 300 mesh copper grid and left for 1 min to allow some vesicles to adhere to the carbon substrate. Excess dispersion was removed by a piece of filter paper followed by rising the grid twice in deionized water for 3–5 s. Next, a drop of 2% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate was applied for 1 s. The remaining solution was removed using filter paper, and the sample was air-dried. Afterward, the sample was viewed under the microscope at 10–100k magnification power using an accelerating voltage of 100 kV using the JEOL TEM (Model 100 CX II; Tokyo, Japan).

2.4.4 In vitro drug release study

The in vitro drug release from the N-GSH niosomal formulation as compared to the free GSH was determined at 37°C similar to the pH of the stomach (pH 1.2) and small intestine (pH 6.8). The pH was adjusted to 6.8 with 0.5 M HCl and 0.05 M phosphate buffer. These were used to mimic the pH conditions of the stomach and small intestine. About 1 mL of N-GSH formulation, equivalent to 50 mg of GSH, was placed over a previously soaked cellulose membrane (Spectro/Por membranes, molecular weight cut-off: 12–14 kDa) fitted at the lower end of a glass cylinder, and the glass cylinder was then dipped in a beaker containing 100 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 1.2 and 6.8, 100 mL) at 37 ± 0.5°C, and shaken at 50 rpm using a thermostatically controlled water bath (Gesellschaft Labor Technik MBH & Co., GFL. Germany). Aliquots (5 mL) were removed and substituted with a freshly prepared buffer medium. The drug content was estimated by the RP-HPLC method at the predefined time points for 24 h. The in vitro release experiment was repeated in triplicate.

2.4.5 Kinetic release study

The data obtained from the in vitro release studies were analysed using the linear regression method (r 2). The release data were analysed according to the zero-order kinetic model, Higuchi diffusion model, and Korsmeyer–Peppas model.

Zero-order kinetics:

where Q is the drug released at time t and k 0 is the zero-order release constant.

Higuchi model:

where Q is the amount of drug released at time t per unit area, and KH is the Higuchi release rate constant.

Korsmeyer–Peppas equation:

where Mt/M∞ is the fraction of drug released at time t and n is the release exponent. The n value is indicative of the drug release mechanism, where n ≤0.5 indicates a Fickian diffusion mechanism, while 0.5 < n < 1 indicates a non-Fickian mechanism (anomalous diffusion). If n = 1, it indicates a zero-order mechanism (case II relaxation). In the case of n > 1, it indicates a super case II transport. The anomalous diffusion or non-Fickian diffusion refers to a combination of both diffusion and erosion controlled release rate, while case II relaxation and super case II transport refer to the erosion of the polymeric matrix.

2.4.6 Stability studies

The stability of all formulations was determined by storing them at 4°C and room temperature in a sealed 20 mL glass vial. The size, PDI, and zeta-potential values were recorded at predefined time intervals (fresh preparation and 4 weeks after storage). All the measurements were repeated in triplicate.

2.5 In vivo experiment

All approvals were obtained by the ethical committee at the faculty of Pharmacy, South Valley University (Approval # P1001). Animals were purchased from Helwan Animal Breeding House, Cairo, Egypt. Sixty-four adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing between 130 and 150 g were used. Animals were kept under optimized conditions of 12 h light–12 h dark cycle, 25 ± 2°C temperature, and were fed standard rat chow and water ad libitum. The animals were treated according to international and national ethical guidelines.

2.5.1 Experimental design

Animals were randomly divided into 8 groups (n = 8 per group) as follows: G1 (Normal group), healthy control animals received corn oil (1 mL/kg, twice a week) by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) and distilled water (0.5 mL/day, orally) for 8 consecutive weeks; G2 (CCl4 group), animals were i.p. injected with CCl4 as 50% solution in corn oil (1 mL/kg, twice a week) for 8 consecutive weeks and 0.5 mL normal saline (0.5 mL/day, orally) for 8 consecutive weeks; G3 (silymarin group), rats were orally administered 100 mg/kg/day silymarin for 8 consecutive weeks; G4 (GSH group), rats were orally administered 100 mg/kg/day of reduced glutathione for 8 consecutive weeks; G5 (N-GSH group), rats were orally administered 100 mg/kg/day reduced N-GSH (nano-glutathione) for 8 consecutive weeks; G6 (CCl4 + silymarin), rats were administered 1 mL of CCl4 (50% solution in corn oil, i.p., 1 mL/kg, twice a week) + 100 mg/kg/day silymarin orally for 8 consecutive weeks; G7 (CCl4 + GSH), rats were administered 1 mL CCl4 (50% solution in corn oil, i.p., 1 mL/kg, twice a week) + 100 mg/kg/day reduced glutathione (GSH) orally for 8 consecutive weeks; and G8 (CCl4 + N-GSH), rats were administered 1 mL of CCl4 (50% solution in corn oil, i.p, 1 mL/kg, twice a week) + 100 mg/kg reduced N-GSH orally for 8 consecutive weeks.

2.5.2 Blood and liver sampling

Twenty-four hours after the last administered dose, under light diethyl ether anaesthesia, blood samples were collected from inferior vena cava in clean, dry test tubes, and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min; serum was separated and refrigerated at −20°C for further analysis. The liver of each animal was immediately dissected out, washed with ice-cold saline. The liver samples were macroscopically examined to determine the apparent intensity of the damage, and its relative weight to the animal’s total weight was recorded. Parts of liver samples were collected and homogenized using 100 mmol KH2PO4 buffer containing 1 mmol EDTA (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 30 min at 4°C to produce the 10% homogenate. The supernatants were collected and refrigerated at −80°C for further analysis through RP-HPLC. Other parts of the hepatic tissues were also preserved in 10% formalin for histopathological examinations.

2.5.3 Histopathological examination

The hepatic tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin at room temperature for 24 h, and samples were dehydrated using graded ethanol and embedded in paraffin wax. Tissue sections with a thickness of 5 µm were deparaffinized using xylene and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) [27]. Hepatic tissue staining for NF-KB [28] and Bcl-2 [29] were performed using a standard immune-histochemical procedure. Histopathological analysis was performed in the Pathology Department at the faculty of Medicine, South Valley University, and visualized using an Olympus microscope with 200× magnification.

2.5.4 Determination of total protein

Protein concentrations in the hepatic tissue homogenates were determined using the Bradford technique [30].

2.5.5 Determination of liver enzymes

Levels of serum AST and ALT were determined calorimetrically [31] using commercial kits obtained from Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt.

2.5.6 Assessment of NO concentration

NO levels in the hepatic tissue were determined using a commercial kit (Biodiagnostics, Cairo, Egypt) following the manufacturer's instructions. NO is converted to nitrous acid followed by a reaction with sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine producing azo dye. The absorbances of samples were measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm.

2.5.7 Assessment of SOD

The hepatic tissue SOD activity was measured using a standard kit (Biodiagnostics, Cairo, Egypt) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Serial dilutions of the standard SOD and samples were added to each well, followed by the radical detector and xanthine oxidase. The plate was shaken and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Samples absorbances were recorded at 440–460 nm using the ELISA microplate reader.

2.5.8 Assessment of inflammatory marker (IL-Iβ)

The total hepatic IL-1β was measured in the hepatic tissue supernatant obtained using the corresponding rat-specific ELISA kit by following the manufacturer’s protocols [32].

2.5.9 Assessment of MDA

MDA levels in the hepatic tissue homogenates were determined using the spectrophotometric method based on the reaction between MDA (the product of lipid peroxidation) and TBA. The pink color produced was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm [33].

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using graph-pad prism version 9.2.0 (332). Values were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n = 8. A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare groups’ results, followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The difference was considered significant for p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Development and characterization of GSH-loaded niosomes

3.1.1 Vesicle size, zeta potential, and EE measurements

The results in Table 2 showed the vesicle sizes of all the formulations that were in the range of 476 ± 10.32 to 688.5 ± 14.52 nm. Formulations prepared with varying molar ratios of cholesterol under similar experimental conditions showed a slight increase in the vesicle size. The optimized formulation, GTN-8, was evaluated for its zeta potential, which was at −26.47 ± 0.158 mV. The negative zeta-potential values might be due to the presence of hydroxyl groups of the cholesterol molecule.

Physicochemical characteristics of the prepared glutathione-loaded niosomes

| Formulation | Particle size (nm) | PDI |

|---|---|---|

| GTN-1 | 476 ± 10.32 | 0.501 ± 0.10 |

| GTN-2 | 658.28 ± 15.32 | 0.433 ± 0.04 |

| GTN-3 | 500.5 ± 7.887 | 0.426 ± 0.02 |

| GTN-4 | 686.0 ± 20.38 | 0.506 ± 0.19 |

| GTN-5 | 482.9 ± 7.75 | 0.491 ± 0.08 |

| GTN-6 | 662.5 ± 2.23 | 0.462 ± 0.28 |

| GTN-7 | 506.9 ± 12.73 | 0.470 ± 0.28 |

| GTN-8 | 688.5 ± 14.52 | 0.509 ± 0.08 |

Table 2 illustrates the EE (%) of GSH of the niosomes containing cholesterol and non-ionic surfactants in ratios of 1:1 and 2:1. It was observed that by increasing the cholesterol contents from a 1:1 to 2:1 molar ratio of both the Span60® and Span40®, the EE of GSH niosomes increased significantly (p < 0.05). Formulations GTN-4 and GTN-8 (Table 1) with the composition of cholesterol and Span60® in the ratio of 2:1 showed a maximum EE percentage at 65 ± 3.6 and 66 ± 2.8%, respectively. Also, the EE of the GSH increased significantly by increasing the drug contents from 250 to 500 mg (p < 0.05) in the prepared niosomes formulations. Based on the above-mentioned results of the EE, the optimized formulation GTN-8 that showed higher EE% was selected for further in vitro release and in vivo studies.

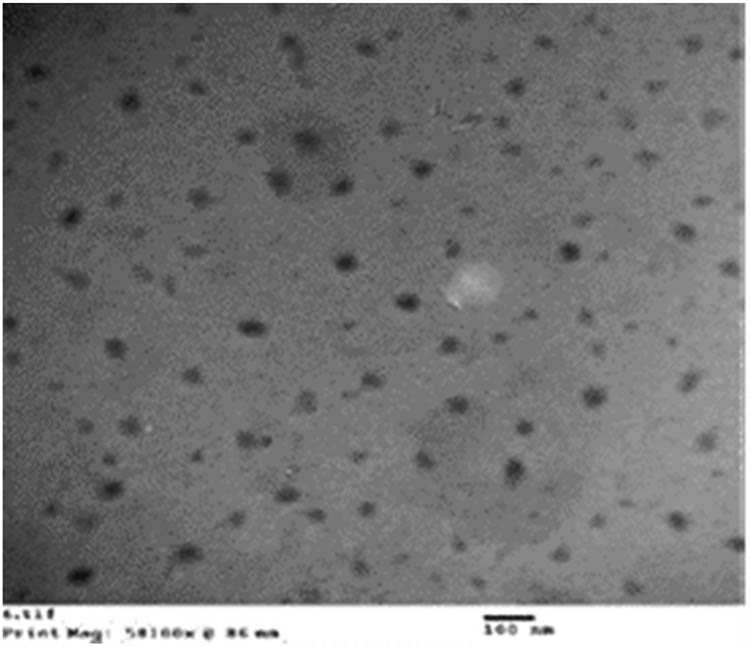

3.1.2 TEM and microscopic examination

Figure 1 shows the TEM image of the optimized glutathione-loaded niosomes (prepared formulation, GTN-8). The vesicles had uniform spherical shapes and were free of aggregation.

Transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) of glutathione-loaded niosomes, N-GSH (formulation, GTN-8).

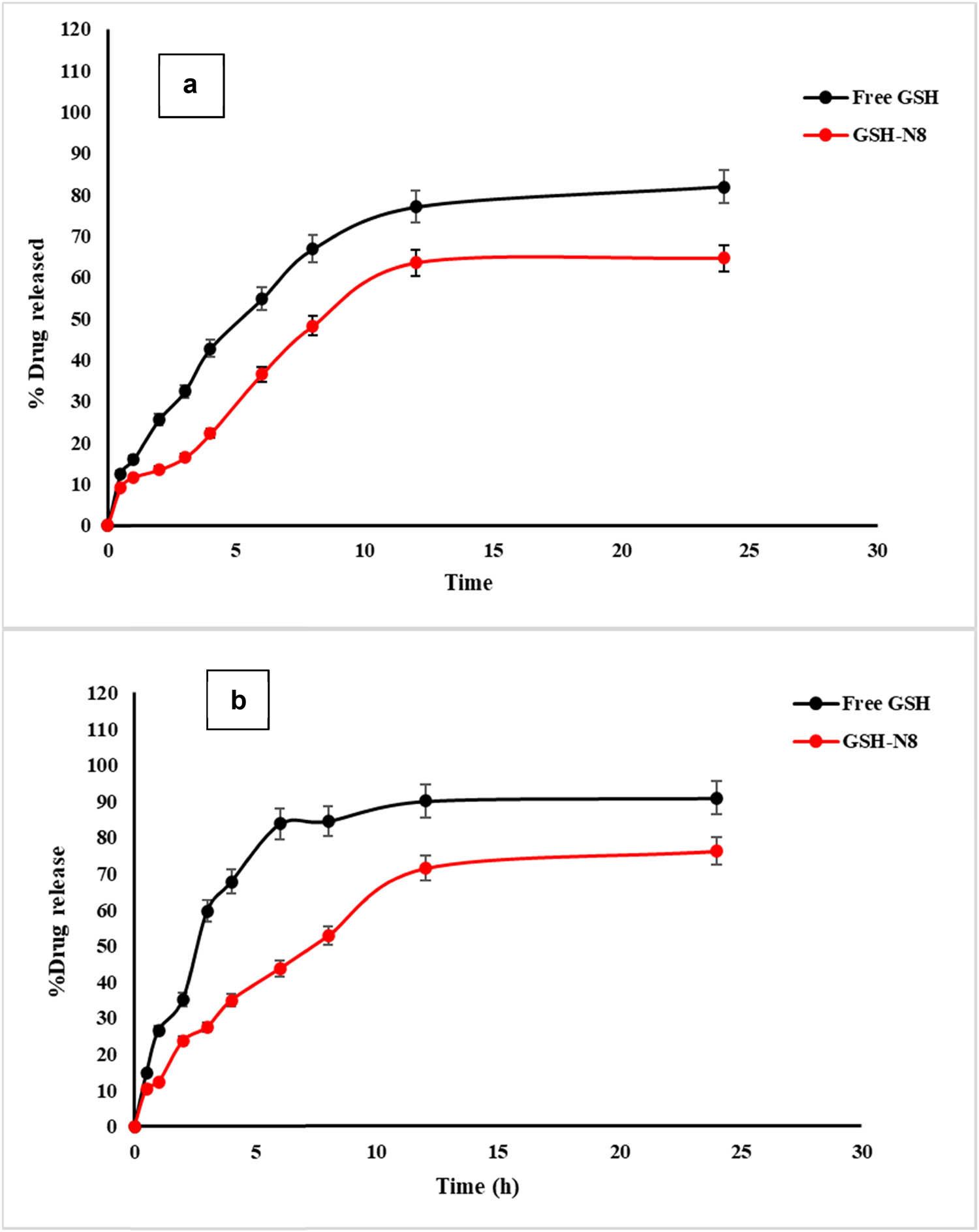

3.2 In vitro drug release studies

The GSH release in pure form and from niosomes formulation (GTN-8) at similar pH of the gastrointestinal tract (stomach: pH 1.2, and intestine: pH 6.8) is exhibited in Figure 2. The release profile of the free drug at pH of the stomach and intestine demonstrated a maximum drug release of 33 and 59.7%, respectively, in a 3 h period. Consequently, 90.9% of the drug was released within 24 h at the pH of the intestine. Also, it was noticed that in the stomach environment (Figure 2a), only 35.5% of GSH was released from the niosomes after 6 h of incubation, which represented the integrity of the nanovesicles maintained in this simulated condition, and their ability to restrict GSH release in an acidic environment. However, in terms of intestinal pH (pH 6.8) (Figure 2b), the release of GSH showed a higher release rate than at pH 1.2, and the release of GSH reached 45% after 6 h of time.

Release profiles of GSH (free and selected niosomes (formulation, GTN-8)) at pH 1.2 (a) and pH 6.8 (b) (n = 3, mean ± SD).

3.2.1 Release kinetics of glutathione (GSH)

The kinetic parameters of GSH release from GTN-8 formulation that followed the zero-order kinetics model, Higuchi model, and Korsmeyer–Peppas model are summarized in Table 3. It was found out that the best-fit model for the GSH release from the GTN-8 formulation was the Higuchi diffusion model. According to all the applied models, the release speed (k) was less at pH 1.2 as compared to that at pH 6.8. The calculated n value was between 0.5 and 1, which corresponded to the anomalous non-Fickian transport, whereas the mechanism of drug release seemed to be governed by matrix erosion and diffusion [34]. These results agreed with the previous investigations that reported similar release patterns for niosomes [35].

Modelling of glutathione release kinetics from the selected formulation GTN8 in the stomach (pH 1.2) and intestine (pH 6.8)

| pH | Zero-order | Higuchi-model | Korsmeyer–Peppas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K 0 (mg/mL/h) | R 2 | K h (h0.5) | R 2 | K | R 2 | n | |

| 1.2 | 2.65 | 0.88899 | 16.03209 | 0.947581 | 5.91 | 0.948971031 | 0.7 |

| 6.8 | 2.903418 | 0.903418 | 17.66243 | 0.971605 | 6.79 | 0.986886917 | 0.6 |

3.3 Stability studies

Stability studies were conducted at 4°C and at room temperature for the optimized niosomal formulation GTN-8, and the results are summarized in Table 4. It was found out that no considerable variations occurred. After 4 weeks of storage, the formulation showed a slight increase in size at 4°C, and at room temperature, respectively, as 710 ± 12.45 and 760 ± 14.32 nm, which were within the acceptable range. Further, the values of PDI were found to be 0.509 and 0.580. In addition, the zeta-potential values remained near −20 mV, which indicated the homogenous nature of the vesicles distribution and the niosomes stability. As shown in Table 4, there are also no significant changes in the EE values of the GSH-loaded niosomes.

Vesicle size, zeta potential, PDI, and EE% for the selected formulation GTN8 stored at 4°C and at room temperature for four weeks (n = 3)

| Storage temperature | 4°C | Room temperature (25°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) | 710 ± 12.45 | 760 ± 14.32 |

| PDI | 0.509 ± 0.08 | 0.580 ± 0.08 |

| Zeta potential (mV) | −19.6 ± 0.08 | −12.6 ± 0.23 |

| EE% | 62.5 ± 2.4 | 59.5 ± 1.5 |

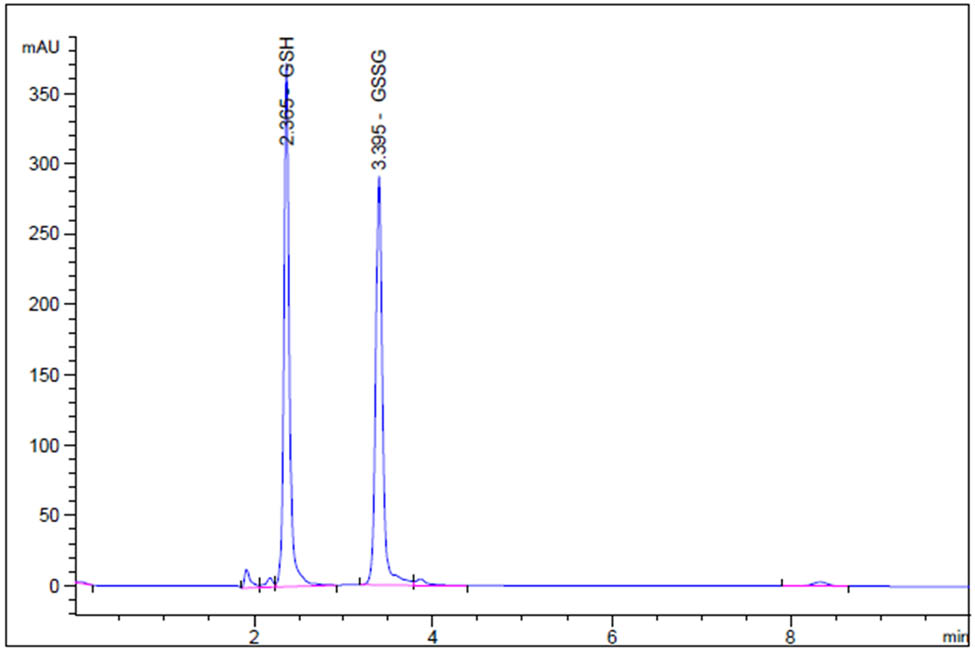

3.4 RP-HPLC analysis validation

Mobile phase parameters for HPLC separations were optimized to produce symmetric, sharp, and well-resolved peaks. After several trials, the optimized mobile phase was found to be a mixture of 10% methanol/90% phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) containing 1 mM EDTA, wherein the column temperature was set at 30°C, and a retention time of 2.35 min for GSH and 3.39 min for GS-SG (Figure 3) at 210 nm were obtained. The validation parameters, such as linearity, accuracy, precision, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantitation (LOQ) were recorded (Table 5). The system suitability parameters, such as the tailing factor, asymmetry factor, number of theoretical plates, and the height equivalent to a theoretical plate (HETP) were also calculated (Table 6).

Representative RP-HPLC-generated chromatogram of a mixture of GSH (2.35 min) and GSSG (3.39 min) (5.0 µg/mL) under optimized conditions.

Summary of the development and validation of the RP-HPLC method

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Retention time (min) | 2.36 |

| Linearity range (µg/mL) | 2.0–7.5 |

| Regression equation | Y = 247.04 + 601.45x |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.998 |

| LOD (µg/mL) | 0.642 |

| LOQ (µg/mL) | 1.94 |

| Accuracy (n = 3) | |

| Mean recovery (%) | 98.36–102.03 |

| % RSD | 0.853–1.44 |

| Precision (n = 3) | |

| Intra-day (% RDS) | 1.05 |

| Inter-day (% RDS) | 1.08 |

| Assay of N-GSH | |

| Mean recovery% | 100.25 ± 0.58 |

| % RSD | 0.58 |

LOD: limit of detection; LOQ: limit of quantitation; RSD: relative standard deviation.

System suitability parameters for the determination of GSH by the HPLC method

| HPLC parameter | GSH | Acceptable limits |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetry factor | 0.820 | >1.5 |

| Theoretical plates (m) | 10,939 | <200 |

| Tailing factor | 1.16 | >2.0 |

| HETP (cm) | 0.00186 |

The validated RP-HPLC method was developed to quantify the loaded GSH in the prepared niosomes. Different mobile phase compositions and ratios were evaluated; the final optimized mobile phase selected was composed of 10% methanol and 90% phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) containing 1 mM EDTA where the column temperature was set at 30°C. The acidic pH of the mobile phase was used to prevent oxidation of GSH and to suppress the ionization of the residual silanols, or other active sites on the stationary phase material [36]. This composition showed a retention time of 2.36 min at 210 nm. The high linearity range (2.5–75.0 µg/mL) showed LOD and LOQ values of 0.64 and 1.94 µg/mL, respectively, indicating that the developed method has good sensitivity. The method showed high recovery (100.25 ± 0.58%) and an RSD% value of less than 2, which were under the accepted criteria for the study. Also, the precision study showed that the method was found to be precise and accurate. The developed method utilized UV absorbance detectors, which are relatively inexpensive and are already widely employed in pharmaceutical laboratories. Moreover, the developed method does not require the test material to be derivatized prior to analysis [37].

The tailing and asymmetry factors of the 5 µg/mL peaks were 1.16 and 0.820, respectively. The theoretical plate number was determined to be greater than 2,000, and the HETP was 0.00186 cm. These values are within acceptable limits and demonstrate the system’s suitability for the proposed test (Table 5). The well-shaped peaks in the chromatograms confirmed that the method has satisfactory specificity.

3.5 Hepatic contents of the reduced glutathione (GSH) in animal groups

Hepatic GSH contents were measured by RP-HPLC. The i.p. administration of CCl4 to the rats significantly (p < 0.05) decreased the GSH hepatic tissue contents (8.15 ± 0.66 µg/g protein) as compared to its contents in the untreated normal group of animals (15.83 ± 2.16 µg/g protein). Oral administration of silymarin partially restored the GSH contents (12.33 ± 0.63 µg/g protein) and ameliorated the CCl4 effects. However, a modest protective effect was observed by oral administration of GSH against CCl4 reducing effects (9.91 ± 1.07 µg/g protein). These results also revealed that N-GSH was significantly (p < 0.05) protecting the hepatocytes against the CCl4 depleting effects and normalized the GSH levels in the hepatocytes (15.90 ± 1.02 µg/g protein).

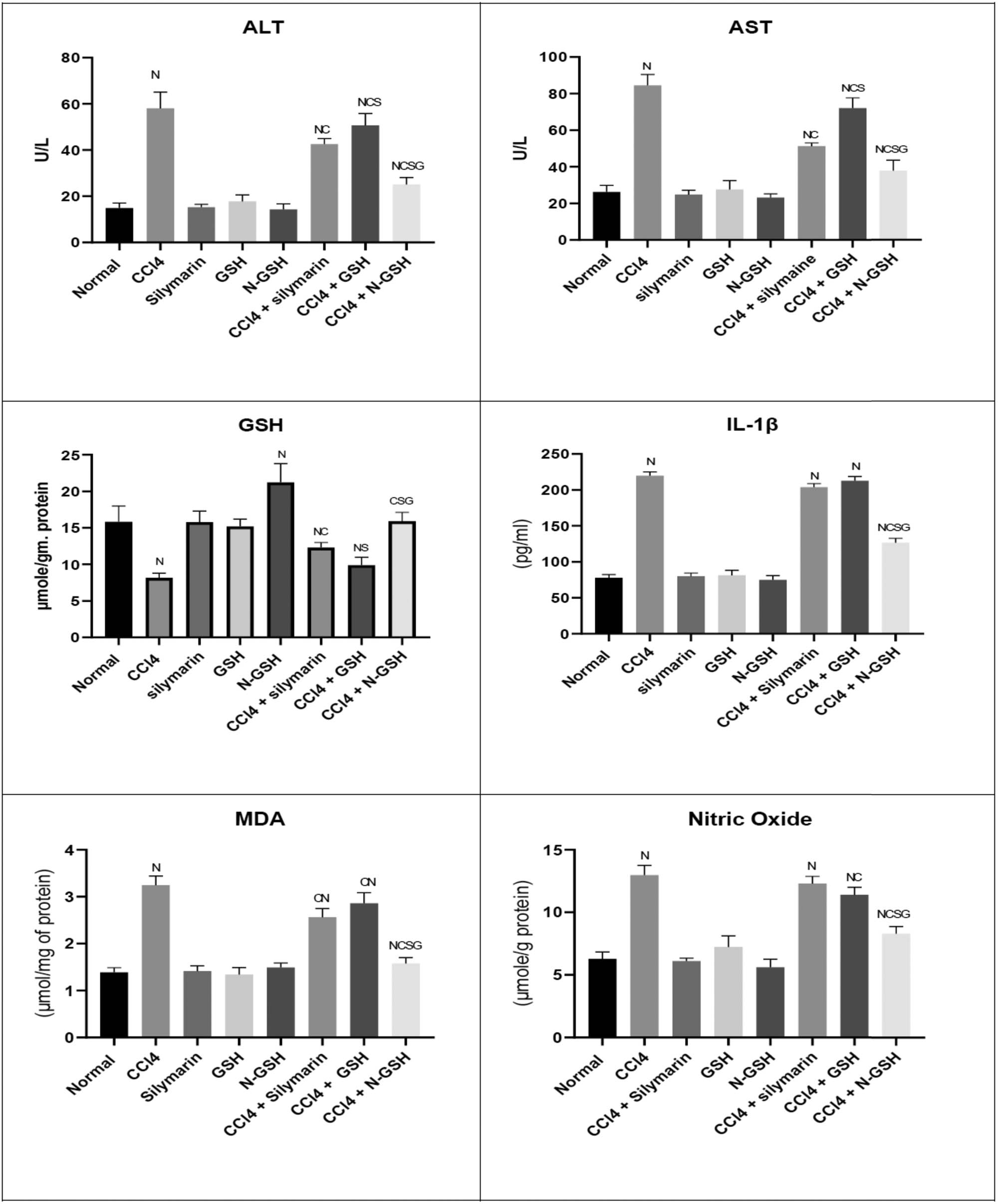

3.6 Levels of oxidative stress and biochemical parameters of hepatic tissues in the injured and treated rats

As presented in Figure 4, the i.p. administration of CCl4 significantly (p < 0.05) resulted in the hepatic tissue damage that was represented by the extremely elevated MDA concentrations (3.25 µmol/mg protein) in the hepatic tissue and the hepatic enzymes ALT (58 U/L) and AST (84 U/L) concentration in the serum levels, while the SOD concentration was significantly reduced (21 µg/g protein). Moreover, the CCl4 animal group, which was concomitantly treated by silymarin, showed a moderate decrease in that damage as shown by the reduced levels of MDA (2.5 µmol/mg protein), ALT (42.5 U/L), AST (72 U/L), and elevated SOD (24.8 µg/g protein) levels as compared with the CCl4 group. In contrast, the GSH + CCl4 co-administration produced marginal changes in these parameters. However, co-administration of N-GSH + CCl4 significantly (p <0.05) reduced the MDA (1.5 µmol/mg protein), ALT (25 U/L) AST (37 U/L), but increased the SOD (33 µg/g protein) as compared to other CCl4 treated groups.

Variations in the levels of biochemical parameters in the normal, injured, and treated rats. (N = significantly different compared to the normal group, C = significantly different compared to the CCl4 group, S = significantly different compared to the CCl4 + silymarin group, G = significantly different compared to the CCl4 + glutathione group).

3.7 Levels of inflammatory mediators in the injured and treated rats

To explore whether the N-GSH significantly ameliorates the inflammatory mediator's progression produced by CCl4, the levels of NO and IL-1β were measured. The CCl4 administration significantly (p < 0.05) increased both the IL-1β (217.9 pg/mL) and NO (17.9 µM/g protein) levels as compared to the normal group, while this effect was moderately suppressed by co-administration with silymarin and GSH (Figure 4). However, a marked reduction (p < 0.05) in both the inflammatory mediators, IL-1β (126.5 pg/mL) and NO (8.27 µM/g protein), was demonstrated by co-administration of CCl4 with N-GSH as compared to other groups.

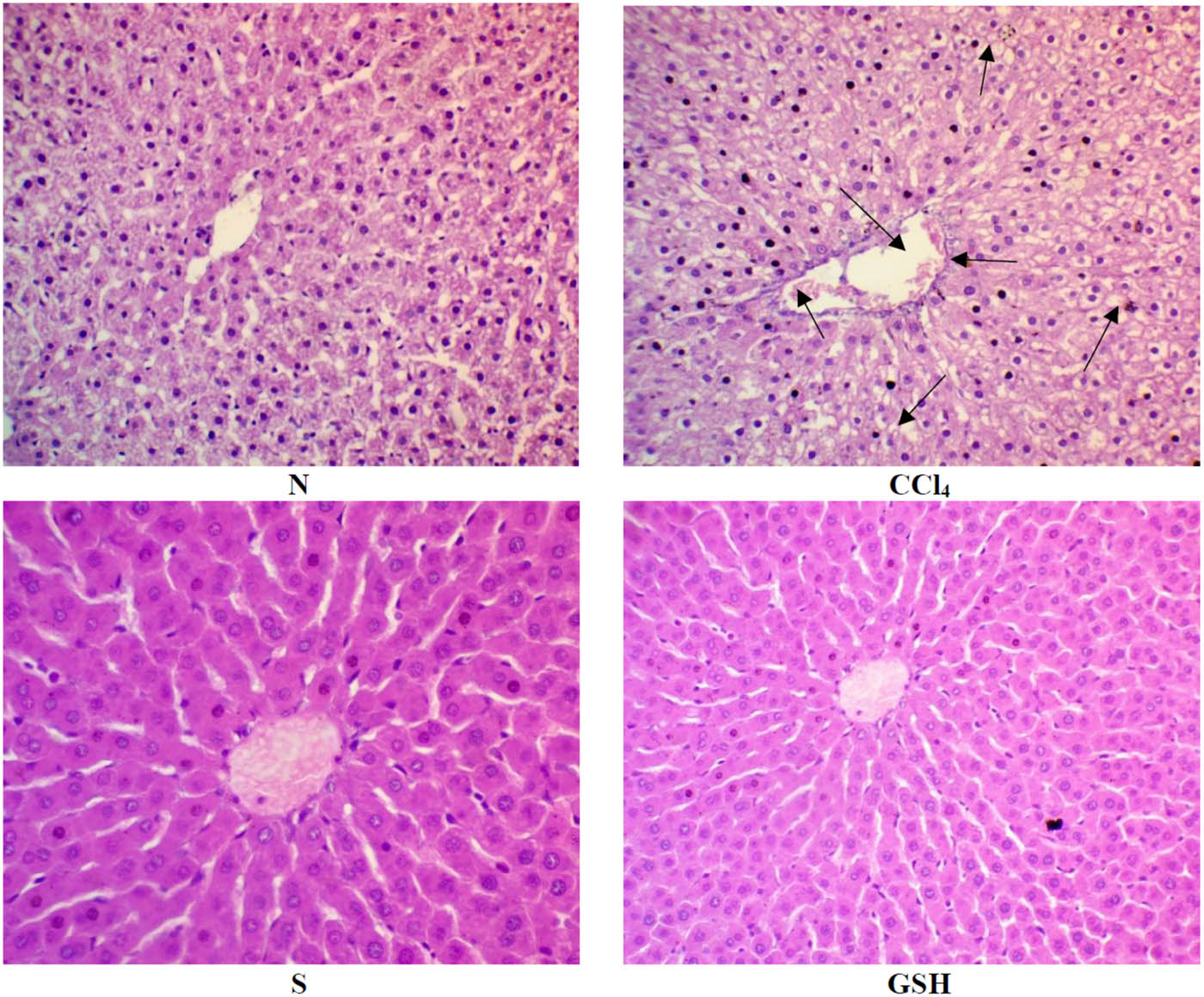

3.8 Histopathology of the liver in the injured and treated rats

The untreated rat’s liver cross-section (Figure 5, plate N) showed a normal central vein with hepatocyte cords arranged around the central vein. The section also showed no fatty changes or degeneration, and hepatocytes were separated with non-dilated and non-congested sinusoids. The CCl4 administered rat’s liver (Figure 5, plate CCl4) showed markedly dilated congested central vein, and the surrounding hepatocytes showed moderate vacuolar clear cytoplasm with hepatocytes degeneration (arrow-head) and were separated by dilated and congested sinusoids (arrow). The animals treated with silymarin (Figure 5, plate S) showed the hepatic tissue of normal architecture, wherein hepatocytes were normally radiating from the central vein and sinusoidal space. In the section obtained from glutathione-treated rat’s liver (Figure 5, plate GSH), normal central veins with normal hepatic architecture were observed (Figure 5).

Histopathology of rats’ liver (H&E stain). N = normal rats; CCl4 = injured rats; S = silymarin-treated rats; GSH = glutathione-treated rats.

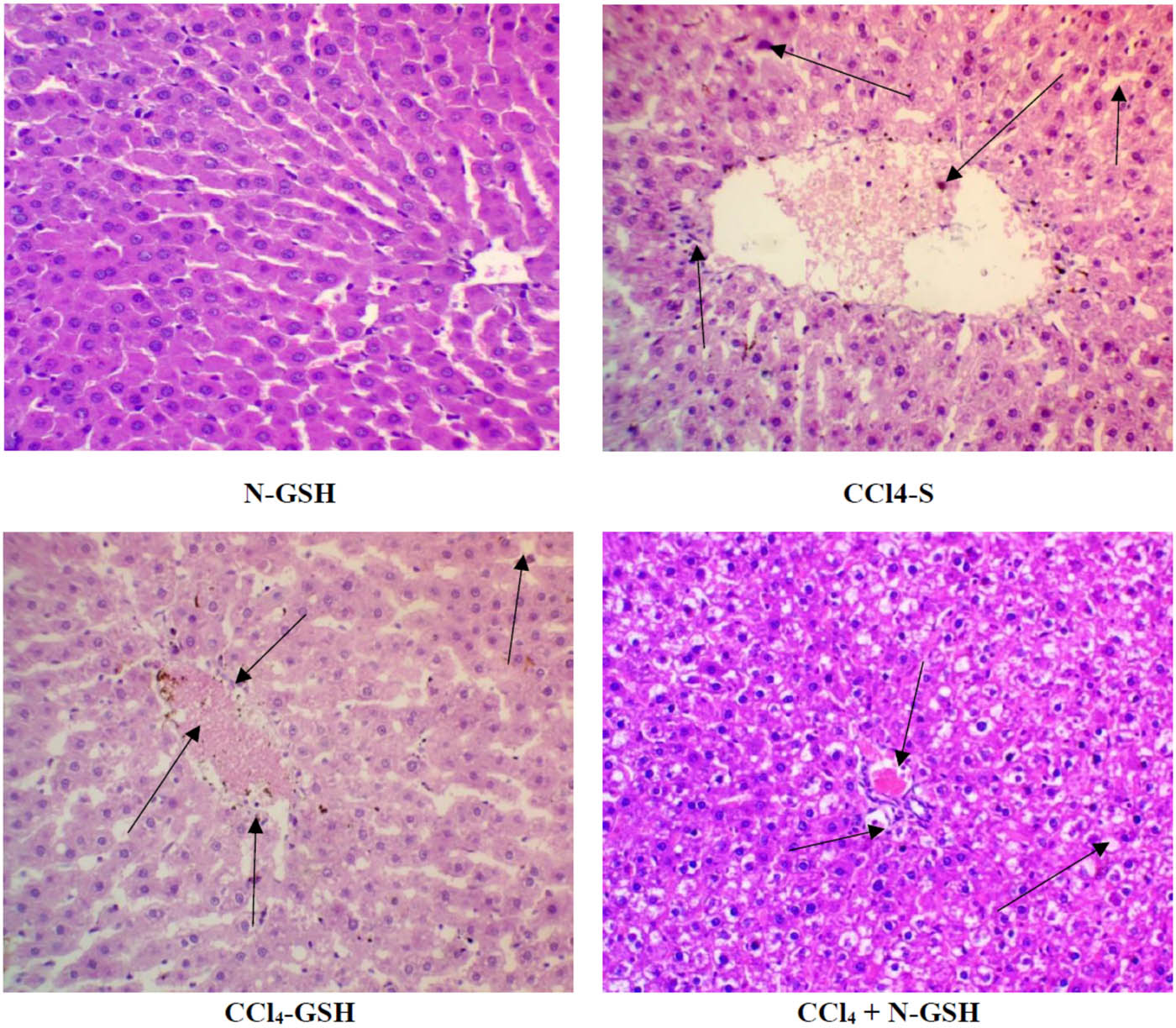

The tissue section obtained from the N-GSH treated rat’s liver showed the normal central vein with hepatocyte cords arranged around the central vein and regular marginal disruption in the normal liver histology. In the group of animals administered with CCl4 and silymarin (CCl4-S), the liver sections showed dilated congested central vein with surrounding hepatocytes showing vacuolar cytoplasm that was separated by hepatic sinusoids with inflammatory cell infiltration and sinusoidal congestion with the red blood cells. In the CCl4 + glutathione group (CCl4-GSH), the hepatic tissue showed dilated and congested central vein with inflammatory cell infiltration, some fatty degeneration of hepatocytes, and there were sinusoidal congestions with a number of hepatocytes showing morphological criteria of apoptosis. Also, the nuclei were seen in the periphery in some of the hepatocytes. In the group of CCl4 + nano-glutathione (CCl4 + N-GSH), the liver tissue section showed congested central vein with surrounding hepatocytes with clear vacuolated cytoplasm and central rounded nuclei (Figure 6).

Histopathology of rats’ liver (H&E stain). N-GSH = nano-glutathione-treated rats; CCl4-S = CCl4 + silymarin-treated rats; CCl4-GSH = CCl4 + glutathione-treated rats; CCl4 + N-GSH = CCl4 + nanoglutathione-treated rats.

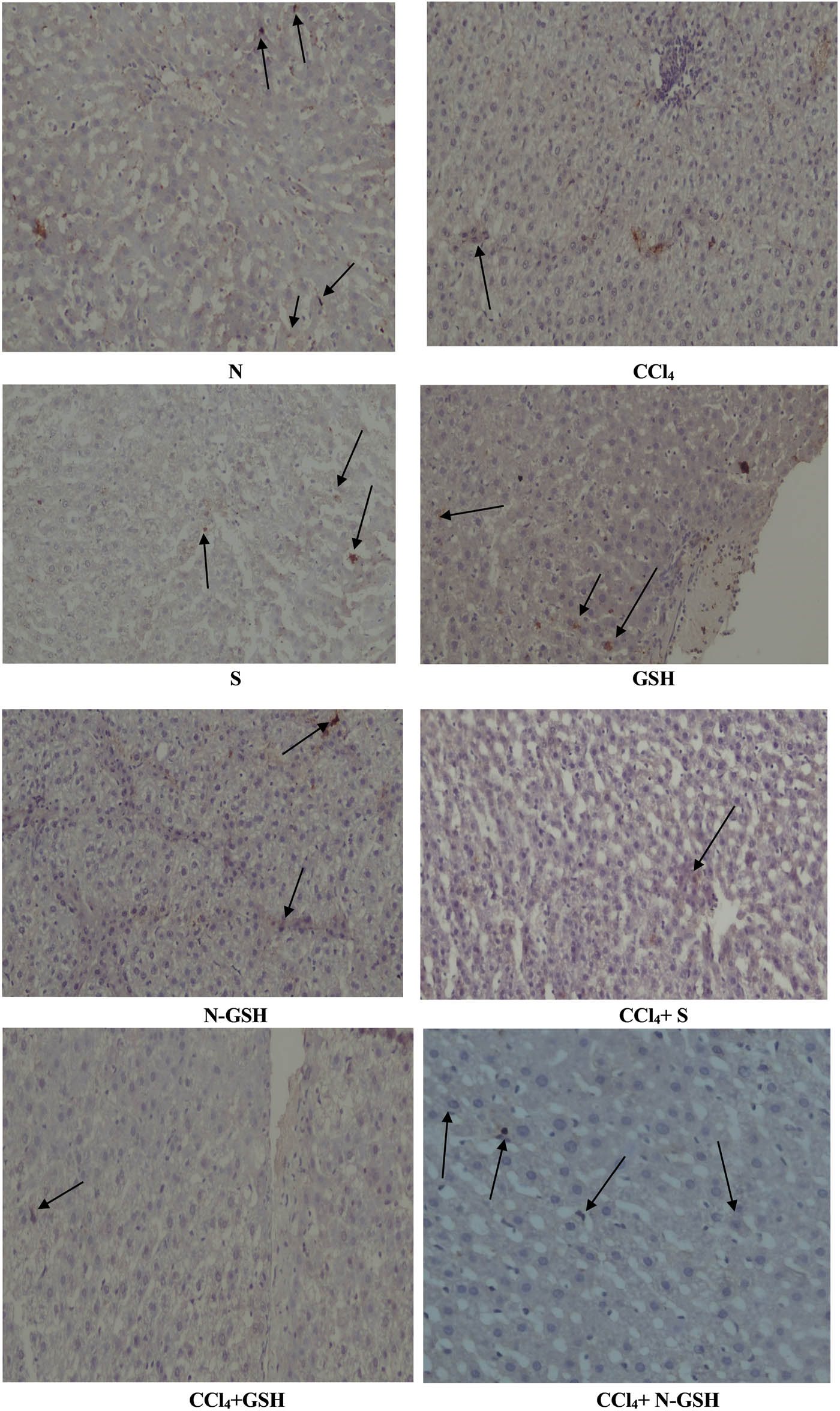

3.9 Effects of Bcl-2 protein on the injured and treated rats

Bcl-2 protein was detected in the hepatic tissue of normal, silymarin, GSH, and N-GSH administered animal groups. However, Bcl-2 protein was absent in the CCl4 group stained hepatocytes with Bcl-2 antibody detection. The CCl4 + silymarin group showed a small number of mild and intense hepatocytes, whereas the Bcl-2 protein in the CCl4 + GSH group was nearly absent. On the contrary, the CCl4 group treated by N-GSH showed a remarkable presence of Bcl-2 protein, also represented by multiple stained hepatocytes (Figure 7).

Immunohistochemistry results of Bcl-2 on hepatic tissues of N, normal rats; CCl4, treated rats; S, silymarin-treated rats; GSH, glutathione-treated rats; N-GSH, nano-glutathione-treated rats; CCl4 + S, CCl4 + silymarin-treated rats; CCl4 + GSH, CCl4 + glutathione-treated rats; and CCl4 + N-GSH, CCl4 + nanoglutathione-treated rats.

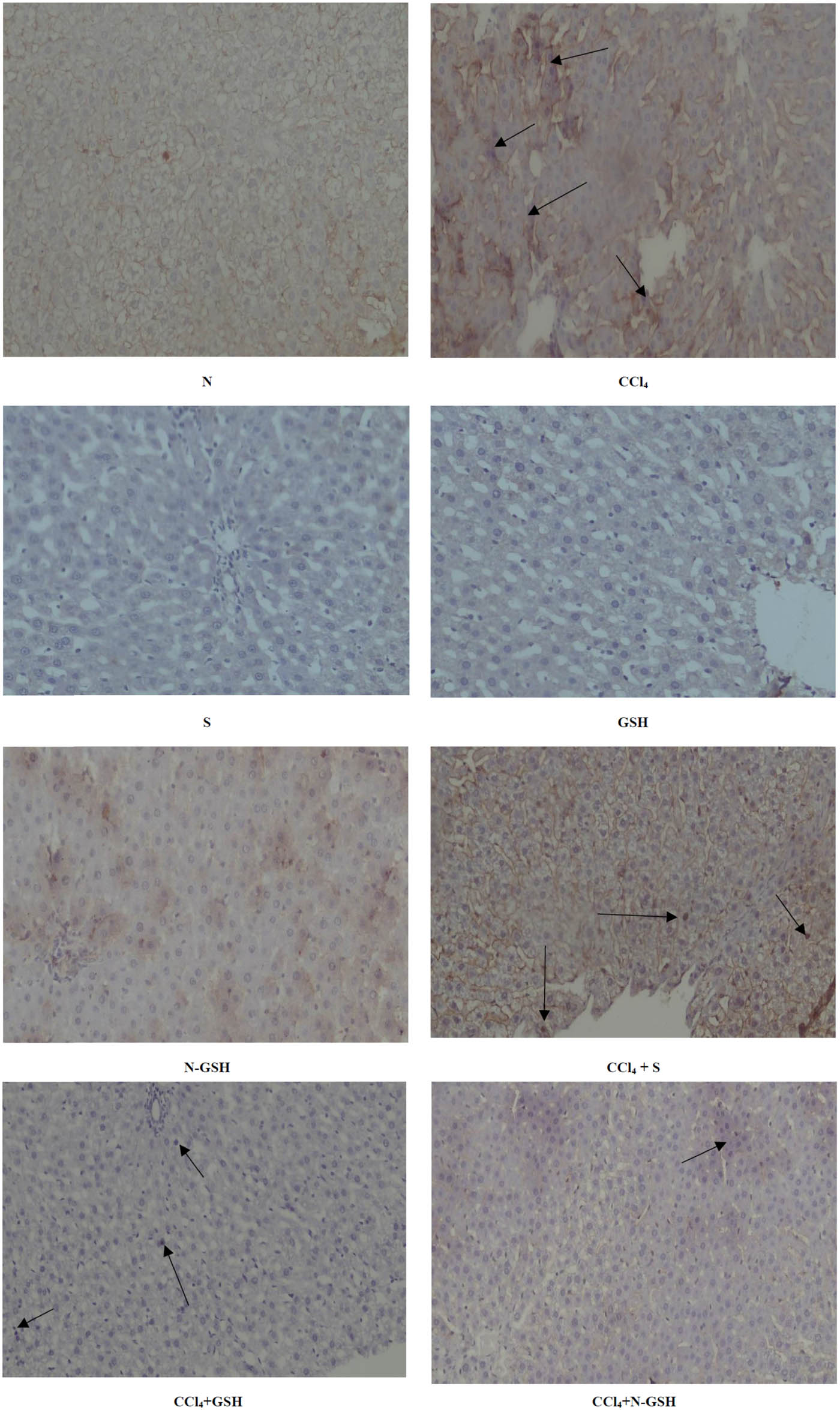

3.10 Effect of NF-Kβ on the injured and treated rats

Positive NF-Kβ hepatocytes were not observed in normal, silymarin, GSH, and N-GSH administered animal groups, while it was highly upregulated by CCl4 treatment (CCl4 group). The GSH treatment (CCl4 + GSH group) nearly did not decrease the NF-Kβ-positive hepatocytes as compared to the CCl4 non-treated group. However, silymarin treatment (CCl4 + silymarin group) moderately decreased the NF-Kβ-positive hepatocytes. A remarkable decrease in the number of NF-Kβ-positive hepatocytes was observed in the CCl4 group treated by nano-glutathione (CCl4 + N-GSH) (Figure 8).

Immunohistochemistry results of NF-Kβ on hepatic tissued of N, normal rats; CCl4, treated rats; S, silymarin-treated rats; GSH, glutathione-treated rats; N-GSH, nano-glutathione-treated rats; CCl4 + S, CCl4 + silymarin-treated rats; CCl4 + GSH, CCl4 + glutathione-treated rats; and CCl4 + N-GSH, CCl4 + nanoglutathione-treated rats.

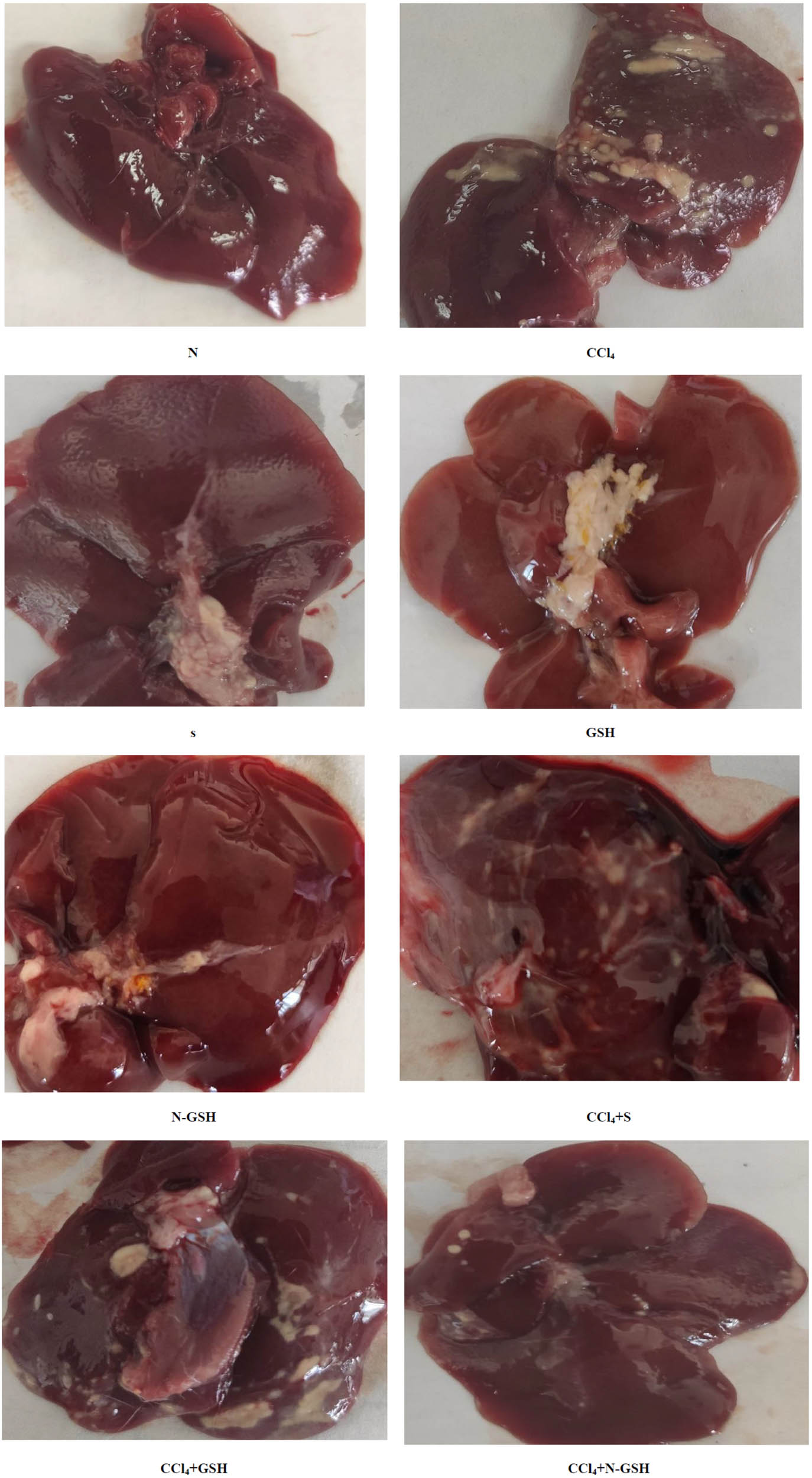

3.11 Macroscopic examination of the liver in the injured and treated rats

Normal gross morphology with the normal architecture of the liver was observed in normal, silymarin, GSH, and N-GSH-administered animal groups, while the CCl4-treated animal groups showed irregular, pale, and gross surfaces, with multiple macro- and micronodules, while the silymarin oral administration attenuated CCl4 damaging effect, showed lower numbers of macro- and micronodules as compared to the CCl4-administered animal group with retraction of the liver capsule. In contrast, the CCl4 + GSH group showed many micro- and macronodules with irregular hepatic surfaces. On the other hand, the CCl4 + N-GSH-administered animal group liver tissue showed soft texture and smooth surface, and nearly preserved the liver’s normal anatomy and appearance (Figure 9).

Macroscopic examination of the liver tissues from N, normal rats; CCl4, treated rats; S, silymarin-treated rats; GSH, glutathione-treated rats; N-GSH, nano-glutathione-treated rats; CCl4 + S, CCl4 + silymarin-treated rats; CCl4 + GSH, CCl4 + glutathione-treated rats; and CCl4 + N-GSH, CCl4 + nanoglutathione-treated rats.

4 Discussion

Hepatic damage represents one of the most serious health problems owing to its high prevalence and limited treatment options [38]. When injuries with different etiologies affect hepatic tissues, it triggers fibrogenesis and damage with major clinical implications and fatality at the end-stage liver disease. The molecular processes underlying the pathogenesis of hepatic injury involve complex interchanges of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and necrosis [39].

In this context of liver damage, when the GSH level decreases, the excessive oxidative stress provokes severe health complications, including hepatocyte damage [40]. GSH plays a crucial role in the hepatocytes’ protection against free radicals, thereupon resulting in protecting the DNA, lipids, proteins, encountered toxins’ neutralizations, and regulation of cell cycle progression and apoptosis [41]. Moreover, GSH is also conjugated to a wide range of endogenous hepatotoxic compounds and xenobiotics, making them safer for the liver through enhancing their excretion [41].

GSH administration is therapeutically beneficial. Unfortunately, GSH cannot be used orally, as oral GSH undergoes intestinal hydrolysis by γ-glutamyltransferase that consequently diminishes its bioavailability. Also, the reports on GSH systemic availability revealed that the oral administration of GSH in high doses is also not helpful to increase the GSH levels inside the hepatic tissue to a clinically beneficial level [42]. Therefore, there is a need to increase the systemic bioavailability and hepatic tissue accumulation of GSH by oral administration. For this purpose, an appropriate pharmaceutical dosage form of GSH is required that provides the GSH as an effective hepatoprotective agent [15].

Recently, nano-medicines-based approaches have been introduced as a promising alternative to conventional therapy. Nanoparticles (NPs) were prepared to deliver drugs in a site-directed manner that were achieved through amending the drugs’ physicochemical properties, use of tissue-specific homing devices, allowing specific organ targeting with minimal side effects, and utilization of the encapsulating material, mostly polymers of synthetic and natural origins [43]. The formulated NPs protect the drug, especially macromolecular entities, such as proteins against inactivation until they reach their target organ. Furthermore, the liver is the major organ for the accumulation of nanomedicines owing to its rich blood supply [44].

The current work presents the preparation of niosomes formulations with several non-ionic surfactants with a view to enhance the orally routed GSH’s bioavailability. The thin-film hydration method has been used efficiently to formulate nanovesicles [34]. Several non-ionic surfactants were utilized in the niosomes preparation to understand their effects on niosomes properties and stability. Span40® and Span60® were selected because of their better stability and biocompatibility, compared with other surfactants. Also, Span40® and Span60® have lower irritability and toxicity as compared to other surfactants. These surfactants also have low toxic effects due to their tendency to degrade in vivo to triglycerides and fatty acids [45]. Two other factors also affect the encapsulation of glutathione as a hydrophilic drug within the niosomes, first the permeability of bilayer membranes and second the structural consistency of the hydrocarbon chain of the surfactant [46]. Hence, the formulation, GTN-8, containing high cholesterol and Span60® showed the highest EE (66 ± 2.8%) as Span60® strongly interacts with cholesterol molecules and forms large core space for hydrophilic drug entrapments [47]. In addition, the presence of Tween80® in the formulation enhances the encapsulation of hydrophilic glutathione into the aqueous core of the niosomes vesicles. These observations have been reported earlier and helped us to conclude that the surfactant type and cholesterol concentrations are important and primary factors affecting the niosomes stability and drug entrapments efficiency [46]. A high amount of cholesterol inhibited the gel to the liquid phase transition of the surfactant by firming itself in the bilayer and thereby providing rigidity to the vesicles and preventing the entrapped drugs leakage. This also explained the increase in the EE% of GSH and its sustained release over time [48,49].

The loading of 500 mg of GSH in niosomes formulation, GTN-8, significantly increased the EE as compared with the formulation GTN-4, which contained 250 mg of GSH. The results may be attributed to increased EE, which provided the most drug loading into the currently formulated GTN-8 preparation of the niosomes [24]. The niosomes provided a promising oral delivery module for GSH, partly also owing to their small particle size. All the formulations (GTN-1 to GTN-8) were found in the nanosized range with low values of PDI. The PDI value of ≤0.5 is considered appropriate for drug delivery applications that represent a relatively homogenous distribution of the nanocarriers. According to the stability studies, it was found that the optimized formulation, GTN-8, was a stable niosomes formulation with the acceptable smallest vesicle size and PDI value. The presence of cholesterol and the negative zeta potential resulted in improved stability of the developed niosomes formulation. This result provided evidence for the maintenance of the structural integrity of niosomes for 1 month at 4°C. The results obtained from the formulation also revealed that the presence of different molar ratios of cholesterol and different types of non-ionic surfactants in the fabricated niosomes could affect the GSH encapsulation into nanovesicles. The encapsulation of GSH into niosomes may avoid metabolic degradation and provide a small particle size, which enhances oral glutathione bioavailability. Glutathione release from niosomes in the stomach environment (pH 1.2) was less as compared with the intestine pH (6.8). Therefore, smaller amounts of GSH will supposedly be degraded in the stomach during the digestion time (about 2 h), and thus, higher quantities of glutathione will be made available for absorption in the intestine. The release of GSH depends on the pH and the ionic strength of the dispersing medium. Niosomes containing cholesterol (anionic moiety) are capable of swelling and shrinking, which are used to trigger its release. Responding to changes in the pH or ionic concentrations, the anionic cholesterol has the tendency to shrink in the acidic media [51]. So, it was anticipated that the GSH niosomes would shrink in an acidic medium and minimize the glutathione release in the stomach environment.

The CCl4-induced liver injury in rats is a widely used model to investigate the potential therapeutic effect of new agents due to their similarities with chemical liver injury in humans [50]. CCl4 is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes to produce reactive intermediates, such as trichloromethyl free radicals and peroxyl free radicals, which initiate the peroxidation of proteins and lipids, leading to hepatocellular damages [52]. In the present study, 50% solution of CCl4 (1 mL/kg) was given intraperitoneally (i.p.) for eight weeks, which was used as an inducer of hepatic injury and resulted in severe hepatic tissue damage as noticed by both macro- and microscopic examinations of the hepatic tissue, which is in parallel to other studies utilizing the same inducer [53].

In the present study, the CCl4 i.p. injection resulted in irregular and nodular hepatic surfaces with fatty depositions, but when CCl4 was co-administered with silymarin (100 mg/kg, orally), there were moderate reductions in the damage that were observed macroscopically; hence, silymarin was also used as a standard hepatoprotective agent to compare the results with GSH and the formulated N-GSH. The oral administration of GSH did not reduce the hepatic damage by CCl4, which is attributable to the poor oral bioavailability of GSH and its diminished ability to reach hepatocytes. On the other hand, the formulated N-GSH niosomes significantly protected the rats’ liver from CCl4 damage, as the macroscopic examination of the rat liver showed a smooth surface with a few small nodules and sporadic fat deposition. These results were also supported by the histo-microscopic examinations, proposing that the N-GSH was more potent than silymarin in protecting the liver from hepatic injury.

Inflammation, a commonly associated condition, with hepatic injury, is an outcome of free radical metabolites of the CCl4 attack on the hepatocytes, which cause the damage of parenchymal cells, promote the hepatocyte’s inflammatory responses, and upregulate the inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α IL-1β, and IL-6 [54]. IL-1β is one of the major players in hepatic inflammation, and its concentration is extremely increased in the case of hepatic injury. It was also found out that IL-1β induces hepatic inflammation and collagen synthesis [55]. Additionally, IL-1β is produced by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and enhances the hepatic production of extracellular matrix, including type I collagen, which leads to hepatic fibrosis and necrosis [55]. The present study also found out that the N-GSH significantly ameliorated the serum IL-1β levels when co-administered with CCl4 as compared to the CCl4 group results in a similar context. Silymarin oral administration also attenuated the CCl4 upregulatory effects on IL-1β, which is consistent with and is supported by prior studies [56]. However, N-GSH was significantly more active than silymarin, while oral GSH showed negligible inhibitory effect for the upregulation of IL-1β as induced by CCl4.

Moreover, Bcl-2 is an apoptosis regulator present in outer mitochondria and plays an important role in liver fibrosis. It was found out that Bcl-2 overexpression in mice livers causes liver fibrosis, indicating that Bcl-2 could be pro-fibrogenic in nature. It was also reported that animals exposed to liver injury inducer, CCl4, not only demonstrated the increase in Bcl-2 expression but also, surprisingly, decreased its expression [57]. In the present study, hepatic tissue immunostaining showed a decline of the Bcl-2 protein expression in the CCl4-administered animal group as compared to the normal group. Our findings are consistent with the previous study where CCl4 reduces Bcl-2 protein expression leading to hepatic cell apoptosis [58]. On the contrary, the N-GSH oral administration exhibited a remarkable increase in Bcl-2 protein expression as compared to other CCl4 groups treated with silymarin and GSH. The increased Bcl-2 protein expression suggested that the N-GSH may protect hepatic tissues against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity by keeping Bcl-2 from being downregulated.

Lipid peroxide is the main parameter, considered a good indicator, of oxidative injury severity. Also, the hepatic tissue MDA concentration is commonly used as an indicator for hepatic tissue damage. The increase of MDA levels in the hepatic tissue homogenate is a clear marker for the severity of oxidative stress, causing tissue damage and depletion of the antioxidant defences [59]. The present study revealed a significant increase in the hepatic MDA concentrations in the CCl4-administered animals’ group tissue homogenate compared to the normal group of animals’ tissue, which is consistent with the previously reported findings [60]. However, the elevated hepatic MDA concentrations were attenuated significantly by oral administration of N-GSH, silymarin, and GSH; however, the MDA attenuation produced through induced N-GSH was more potent than silymarin and GSH. Consequently, it is suggested that N-GSH-protective effects against CCl4-induced hepatic damage by inhibiting lipid peroxidation that is produced by oxidative stress are noteworthy.

The CCl4 i.p. administration to the experimental animal resulted in GSH depletion GSH 8.15 ± 0.66 µg/g protein in the CCl4 group as compared to 15.83 ± 2.16 µg/g levels of protein in the normal group of animals, which was in agreement with the reported result [61]. On the other hand, N-GSH oral administration significantly increased the GSH concentration inside the hepatic tissue of CCl4-injured animals (15.90 ± 1.02 µg/g protein levels) to about two-fold of its concentration in the untreated injured animals, and it was significantly higher than the silymarin and GSH groups. Additionally, the N-GSH, when administered to normal animals, increased the hepatic GSH contents than the normal group animals.

CCl4 induces hepatic injury by generating chloromethyl free radicals (–CCl3), which enables the peroxidation of membrane lipids, and other lipidic contents as well as subcellular structures of the hepatocytes, thereby causing the increase of membrane permeability and resulting in the release of large amounts of the hepatic enzymes, ALT and AST, from the cytoplasm into the blood [62]. For the current study, the CCl4 + N-GSH-administered group showed significantly lowered concentrations of the hepatic enzymes among the CCl4-treated groups, although less than the reference (silymarin) group, indicating the outstanding capability of N-GSH to preserve the hepatocytes’ integrity even under highly stressful conditions. On the other hand, GSH also ameliorated the increased AST and ALT levels but it was much less than those in the N-GSH-administered group.

Drugs and different substances and materials’ accumulative studies have demonstrated that hepatocytes secrete SOD after exposure to injurious pro-oxidants compounds, such as CCl4, which leads to depletion of SOD stores and its dramatically decreased concentrations [63], which was in line with the present findings. SOD catalyses the conversion of superoxide to H2O2, which is further converted into water and oxygen by CAT and peroxidase. Thus, SOD is a major defence and protects hepatic tissues from oxidative stress [64]. In the current study, the N-GSH administration protected the hepatic SOD stores from depletion by CCl4, which could be attributed to its ability to highly upregulate the GSH hepatic concentrations, which seemingly is among the major defensive mediator against oxidative stress in the given situations.

Nonetheless, the increased NO tissue concentration is believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic injury, including oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions. The CCl4 exposure generates excessive amounts of NO by activating the iNOS, contributing to hepatic tissue damages [64], an observation circumstantially consistent with the present study’s findings. Furthermore, these results also revealed that the oral administration of N-GSH also dramatically decreased NO concentrations in the hepatic tissue, thereby contributing to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that excessive free radical production induced by CCl4 can induce upregulation of NF-κB and its nuclear translocation, which is considered responsible for hepatic tissue injury by increasing the inflammatory cytokine production [65,66]. These results also exhibited that N-GSH significantly inhibits the NF-κB tissue expression, which was also consistent with the current findings of the decreased levels of the NO hepatic tissue levels. In contrast, silymarin and GSH oral administration did not significantly affect the NF-κB tissue expressions.

5 Conclusion

A designated, novel formulation of niosomes incorporating GSH was successfully prepared, characterized, and biologically tested for their potential hepatoprotective activity. The concentrations of GSH in the liver tissue homogenates obtained from the CCl4-injured animal’s group and the treated animals with silymarin, GSH, and N-GSH, indicated that N-GSH was prominent in restoring glutathione in the liver to its normal levels as compared to the normal group of animals. These results also proved the successfulness and utility of the N-GSH niosomes formulation in enhancing the absorption, protection, liver tissue uptake, and subsequently, the bioactivity of GSH. Therefore, the present study introduced an improved, novel formulation for reduced glutathione GSH (as N-GSH) with physicochemical properties that enabled it to accumulate inside the hepatic tissue and overcome the pharmacokinetic barriers, which limits the GSH use as one of the most potent and easily available hepatoprotective agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the technical support of Qassim University, Saudi Arabia, and South Valley University, Egypt.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

References

[1] Younossi ZM . Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease–a global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;70(3):531–44.10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033Search in Google Scholar

[2] Reyes-Gordillo K , Shah R , Muriel P . Oxidative stress and inflammation in hepatic diseases: current and future therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3140673.10.1155/2017/3140673Search in Google Scholar

[3] Fang YZ , Yang S , Wu G . Free radicals, antioxidants, and nutrition. Nutrition. 2002;18(10):872–9.10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00916-4Search in Google Scholar

[4] Battin EE , Brumaghim JL . Antioxidant activity of sulfur and selenium: a review of reactive oxygen species scavenging, glutathione peroxidase, and metal-binding antioxidant mechanisms. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;55(1):1–23.10.1007/s12013-009-9054-7Search in Google Scholar

[5] Pham-Huy LA , He H , Pham-Huy C . Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci IJBS. 2008;4(2):89–96.10.59566/IJBS.2008.4089Search in Google Scholar

[6] Armstrong D , editor. Oxidative stress in applied basic research and clinical practice. New York: Springer; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mohammed HA . The valuable impacts of halophytic genus Suaeda; nutritional, chemical, and biological values. Med Chem (Los Angeles). 2020;16(8):1044–57.10.2174/1573406416666200224115004Search in Google Scholar

[8] Franco R , Cidlowski JA . Apoptosis and glutathione: beyond an antioxidant. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(10):1303–14.10.1038/cdd.2009.107Search in Google Scholar

[9] Cnubben NHP , Rietjens IMCM , Wortelboer H , van Zanden J , van Bladeren PJ . The interplay of glutathione-related processes in antioxidant defense. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2001;10(4):141–52.10.1016/S1382-6689(01)00077-1Search in Google Scholar

[10] Scirè A , Cianfruglia L , Minnelli C , Bartolini D , Torquato P , Principato G , et al. Glutathione compartmentalization and its role in glutathionylation and other regulatory processes of cellular pathways. Biofactors. 2019;45(2):152–68.10.1002/biof.1476Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Chen Y , Dong H , Thompson DC , Shertzer HG , Nebert DW , Vasiliou V . Glutathione defense mechanism in liver injury: insights from animal models. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;60:38–44.10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Smeyne M , Smeyne RJ . Glutathione metabolism and Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:13–25.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Gul M , Kutay FZ , Temocin S , Hanninen O . Cellular and clinical implications of glutathione. Indian J Exp Biol. 2000;38(7):625–34.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Viña J , Sastre J , Anton V , Bruseghini L , Esteras A , Asensi M . Effect of aging on glutathione metabolism. Protection by antioxidants. EXS. 1992;62:136–44.10.1007/978-3-0348-7460-1_14Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang H , Forman HJ , Choi J . Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in glutathione biosynthesis. Methods Enzym. 2005;401:468–83.10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01028-1Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lopedota A , Trapani A , Cutrignelli A , Chiarantini L , Pantucci E , Curci R , et al. The use of Eudragit RS 100/cyclodextrin nanoparticles for the transmucosal administration of glutathione. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;72(3):509–20.10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.02.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Rotar O . Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with glutathione for diminishing tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Adv Eng Nanotechnol. 2014;1:19–23.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Chen G , Bunt C , Wen J . Mucoadhesive polymers-based film as a carrier system for sublingual delivery of glutathione. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67(1):26–34.10.1111/jphp.12313Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Byeon JC , Lee S-E , Kim T-H , Ahn JB , Kim DH , Kim , et al. Design of novel proliposome formulation for antioxidant peptide, glutathione with enhanced oral bioavailability and stability. Drug Deliv. 2019;26(1):216–25.10.1080/10717544.2018.1551441Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Van Tran V , Moon J-Y , Lee Y-C . Liposomes for delivery of antioxidants in cosmeceuticals: Challenges and development strategies. J Control Release. 2019;300:114–40.10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] He H , Lu Y , Qi J , Zhu Q , Chen Z , Wu W . Adapting liposomes for oral drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9(1):36–48.10.1016/j.apsb.2018.06.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Tavano L , Muzzalupo R , Picci N , de Cindio B . Co-encapsulation of antioxidants into niosomal carriers: Gastrointestinal release studies for nutraceutical applications. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2014;114:82–8.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.09.058Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Kulkarni P , Rawtani D , Barot T . Design, development and in-vitro/in-vivo evaluation of intranasally delivered Rivastigmine and N-Acetyl Cysteine loaded bifunctional niosomes for applications in combinative treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2021;163:1–15.10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.02.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Arzani G , Haeri A , Daeihamed M , Bakhtiari-Kaboutaraki H , Dadashzadeh S . Niosomal carriers enhance oral bioavailability of carvedilol: effects of bile salt-enriched vesicles and carrier surface charge. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:4797–813.10.2147/IJN.S84703Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Tsiasioti A , Zacharis CK , Zotou A-S , Tzanavaras PD . Study of the oxidative forced degradation of glutathione in its nutraceutical formulations using zone fluidics and green liquid chromatography. Separations. 2020;7(1):16.10.3390/separations7010016Search in Google Scholar

[26] Singh J . International conference on harmonization of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2015;6(3):185–87.10.4103/0976-500X.162004Search in Google Scholar

[27] Feldman AT , Wolfe D . Tissue processing and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1180:31–43.10.1007/978-1-4939-1050-2_3Search in Google Scholar

[28] Lavon I , Pikarsky E , Gutkovich E , Goldberg I , Bar J , Oren M , et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB protects the liver against genotoxic stress and functions independently of p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63(1):25–30.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Nakopoulou L , Stefanaki K , Vourlakou C , Manolaki N , Gakiopoulou H , Michalopoulos G . Bcl-2 protein expression in acute and chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pr. 1999;195(1):19–24.10.1016/S0344-0338(99)80089-2Search in Google Scholar

[30] Pande SV , Murthy MS . A modified micro-Bradford procedure for elimination of interference from sodium dodecyl sulfate, other detergents, and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1994;220(2):424–6.10.1006/abio.1994.1361Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hamada H , Ohkura Y . A new photometric method for the determination of serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase activity using pyruvate and glutamate as substrates. Chem Pharm Bull. 1976;24(8):1865–9.10.1248/cpb.24.1865Search in Google Scholar

[32] DeCicco LA , Rikans LE , Tutor CG , Hornbrook KR . Serum and liver concentrations of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-1β following administration of carbon tetrachloride to male rats. Toxicol Lett. 1998;98(1):115–21.10.1016/S0378-4274(98)00110-6Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ohkawa H , Ohishi N , Yagi K . Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95(2):351–8.10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3Search in Google Scholar

[34] Sadeghi-Ghadi Z , Ebrahimnejad P , Talebpour Amiri F , Nokhodchi A . Improved oral delivery of quercetin with hyaluronic acid containing niosomes as a promising formulation. J Drug Target. 2021;29(2):225–34.10.1080/1061186X.2020.1830408Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Maiti S , Paul S , Mondol R , Ray S , Sa B . Nanovesicular formulation of brimonidine tartrate for the management of glaucoma: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2011;12(2):755–63.10.1208/s12249-011-9643-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Ahmed AM . Analytical study of certain pharmaceutical compounds acting on cardiovascular system. Ph.D. Al-Azhar University, Egypt, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sutariya V , Wehrung D , Geldenhuys WJ . Development and validation of a novel RP-HPLC method for the analysis of reduced glutathione. J Chromatogr Sci. 2012;50(3):271–6.10.1093/chromsci/bmr055Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Paik JM , Golabi P , Younossi Y , Mishra A , Younossi Z . Changes in the global burden of chronic liver diseases from 2012 to 2017: the growing impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2020;72(5):1605–16.10.1002/hep.31173Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Neuman MG . Liver diseases: a multidisciplinary textbook. Hepatotoxicity: mechanisms of liver injury. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020.10.1007/978-3-030-24432-3_7Search in Google Scholar

[40] Ahmed N , Chakrabarty A , Guengerich FP , Chowdhury G . Protective role of glutathione against peroxynitrite-mediated DNA damage during acute inflammation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2020;33(10):2668–74.10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00299Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Sacco R , Eggenhoffner R , Giacomelli L . Glutathione in the treatment of liver diseases: insights from clinical practice. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2016;62(4):316–24.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Schmitt B , Vicenzi M , Garrel C , Denis FM . Effects of N-acetylcysteine, oral glutathione (GSH) and a novel sublingual form of GSH on oxidative stress markers: a comparative crossover study. Redox Biol. 2015;6:198–205.10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Soares S , Sousa J , Pais A , Vitorino C . Nanomedicine: principles, properties, and regulatory issues. Front Chem. 2018;6(360):360.10.3389/fchem.2018.00360Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Bartneck M , Warzecha KT , Tacke F . Therapeutic targeting of liver inflammation and fibrosis by nanomedicine. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3(6):364–76.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Fathalla D , Fouad EA , Soliman GM . Latanoprost niosomes as a sustained release ocular delivery system for the management of glaucoma. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(5):806–13.10.1080/03639045.2020.1755305Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Kumar P , Rajeshwarrao P . Nonionic surfactant vesicular systems for effective drug delivery – an overview. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2011;1:208–19.10.1016/j.apsb.2011.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[47] Abdelbary G , El-Gendy N . Niosome-encapsulated gentamicin for ophthalmic controlled delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2008;9(3):740–7.10.1208/s12249-008-9105-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Sankhyan A , Pawar PK . Metformin loaded non-ionic surfactant vesicles: optimization of formulation, effect of process variables and characterization. Daru. 2013;21(1):7.10.1186/2008-2231-21-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Sita VG , Jadhav D , Vavia P . Niosomes for nose-to-brain delivery of bromocriptine: formulation development, efficacy evaluation and toxicity profiling. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;58:101791.10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101791Search in Google Scholar

[50] Jelvehgari M , Mobaraki V , Montazam SH . Preparation and evaluation of mucoadhesive beads/discs of alginate and algino-pectinate of piroxicam for colon-specific drug delivery via oral route. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2014;9(4):16576.10.17795/jjnpp-16576Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Yanguas SC , Cogliati B , Willebrords J , Maes M , Colle I , van den Bossche B , et al. Experimental models of liver fibrosis. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(5):1025–48.10.1007/s00204-015-1543-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Fortea JI , Fernández-Mena C , Puerto M , Ripoll C , Almagro J , Bañares J , et al. Comparison of two protocols of carbon tetrachloride-induced cirrhosis in rats – improving yield and reproducibility. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9163.10.1038/s41598-018-27427-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Sadeghi H , Hosseinzadeh S , Akbartabar Touri M , Ghavamzadeh M , Jafari Barmak M , Sayahi M , et al. Hepatoprotective effect of Rosa canina fruit extract against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in rat. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6(2):181–8.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Unsal V , Cicek M , Sabancilar İ . Toxicity of carbon tetrachloride, free radicals and role of antioxidants. Rev Env Heal. 2020;36(2):279–95.10.1515/reveh-2020-0048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Schmidt-Arras D , Rose-John S . IL-6 pathway in the liver: from physiopathology to therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1403–15.10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Marcolino Assis-Júnior E , Melo AT , Pereira VBM , Wong DVT , Sousa NRP , Oliveira CMG , et al. Dual effect of silymarin on experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by irinotecan. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;327:71–9.10.1016/j.taap.2017.04.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Teng K-Y , Barajas JM , Hu P , Jacob ST , Ghoshal K . Role of B Cell Lymphoma 2 in the Regulation of Liver Fibrosis in miR-122 Knockout Mice. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(7):157.10.3390/biology9070157Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Yalcin A , Yumrutas O , Kuloglu T , Elibol E , Parlar A , Yilmaz İ , et al. Hepatoprotective properties for Salvia cryptantha extract on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury. Cell Mol Biol. 2017;63(12):56–62.10.14715/10.14715/cmb/2017.63.12.13Search in Google Scholar

[59] Cheng DL , Zhu N , Li CL , Lv WF , Fang WW , Liu Y , et al. Significance of malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase and endotoxin levels in Budd–Chiari syndrome in patients and a rat model. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(6):5227–35.10.3892/etm.2018.6835Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Suzuki K , Nakagawa K , Yamamoto T , Miyazawa T , Kimura F , Kamei M , et al. Carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic and renal damages in rat: inhibitory effects of cacao polyphenol. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79(10):1669–75.10.1080/09168451.2015.1039481Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Kanawati GM , Al-Khateeb IH , Kandil YI . Arctigenin attenuates CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity through suppressing matrix metalloproteinase-2 and oxidative stress. Egypt Liver J. 2021;11(1):1–7.10.1186/s43066-020-00072-6Search in Google Scholar

[62] Li M , Sun Q , Li S , Zhai Y , Wang J , Chen B , et al. Chronic restraint stress reduces carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11(6):2147–52.10.3892/etm.2016.3205Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Di Naso FC , Simões Dias A , Porawski M , Marroni NA . Exogenous superoxide dismutase: action on liver oxidative stress in animals with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res. 2011;2011:754132.10.1155/2011/754132Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Ighodaro OM , Akinloye OA . First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54(4):287–93.10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[65] Chen T , Zamora R , Zuckerbraun B , Billiar TR . Role of nitric oxide in liver injury. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3(6):519–26.10.2174/1566524033479582Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Czauderna C , Castven D , Mahn FL , Marquardt JU . Context-dependent role of NF-κB signaling in primary liver cancer-from tumor development to therapeutic implications. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(8):1053.10.3390/cancers11081053Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 Esam M. Aboubakr et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte