CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

-

Laura Turri

, Karine Gérardin

Abstract

CO2 sequestration by reaction with abundant, reactive minerals such as olivine has often been considered. The most straightforward, direct process consists in performing the reaction at high temperature and CO2 pressure, in view to producing silica, magnesium and iron carbonates and recovering the traces of nickel and chromite contained in the feedstock mineral. Most of direct processes were found to have an overall cost far larger than the CO2 removal tax, because of incomplete carbonation and insufficient properties of the reaction products. Similar conclusions could be drawn in a previous investigation with a tubular autoclave. An indirect process has been designed for high conversion of olivine and the production of separate, profitable products e.g. silica, carbonates, nickel salts, so that the overall process could be economically viable: the various steps of the process are described in the paper. Olivine particles (120 μm) can be converted at 81% with a low excess of acid within 3 h at 95°C. The silica quantitatively recovered exhibits a BET area over 400 m2 g-1, allowing valuable applications to be considered. Besides, the low contents of nickel cations could be separated from the magnesium-rich solution by ion exchange with a very high selectivity.

1 Introduction

The increasing concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is attributed to the rising consumption of fossil fuels for energy generation or use around the world. In order to develop steel industry with low carbon dioxide emissions, chemical processes by reaction of CO2 with minerals derived from silicate minerals, e.g. olivine can be considered [1,2]. Because of their alkaline nature, silica-based minerals can react with acidic carbon dioxide at high pressure and temperature to generate carbonates and silica [3]. Various processes have been investigated as for instance in [4,5]. However, the reaction has a significant cost, estimated in the range 80-200 €/tCO2 depending on the process considered [3]. In this study, the recovery of the products has been considered in the global carbonation process, for an economic profitability and an environmental acceptability. More precisely, the conventional direct route for olivine carbonation has been compared to an indirect process currently under investigation and relying upon olivine acidic leaching followed by carbonation and separation stages. Comparison of the two processes is made in terms of reaction yields and quality of the products obtained.

2 Direct carbonation of olivine

2.1 Feedstock

The olivine used is produced in Norway and can be considered as a mixed Mg-Ni and Fe silicate. The main phase corresponds to the stoichiometry of Mg1,838Fe0,156Ni0,006(SiO4), with chromite particles present at approx. 0.38 wt% and other inert minerals at trace levels. The particle size distribution of the GL30 ® grade used ranged from 70 to 250 μm with an average size of 120 μm (d(0.5) = 121 μm) to limit the grinding costs. More details about olivine characterization and properties are given in [6,7].

2.2 Introduction to the direct process

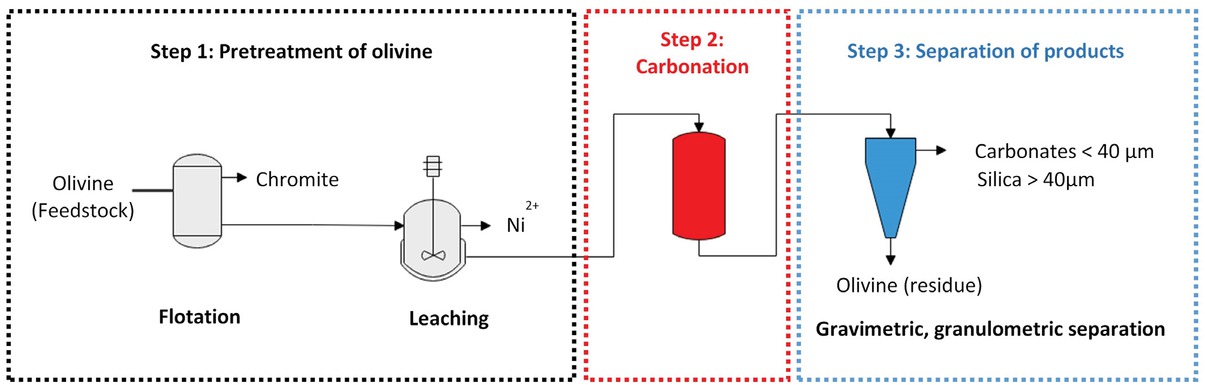

Direct carbonation using olivine as feedstock has been considered as an alternative to convert CO2 emissions into solid carbonates and silica. In this study, separation of carbonation products has been investigated for an environmental aspect and is specifically decisive for the economic viability of the process. The overall process of direct carbonation consists of the following steps (Figure 1):

Schematic view of the process for CO2 sequestration by direct carbonation of olivine.

Olivine pretreatment has been considered before the carbonation reaction, due to the presence of impurities (Step 1). Two separation processes have been investigated successively: (i) flotation of chromite particles, for which the results are presented in [7], (ii) selective leaching of nickel which replaces magnesium in the forsterite matrix (Mg2SiO4) largely present in olivine.

Direct carbonation of olivine particles (Step 2) is to be performed after separation of chromite and nickel. This steps consists of two reactions, namely olivine dissolution then formation and precipitation of carbonation products. Both reactions can be conducted in the same reactor.

Separation of the solids obtained by carbonation (Step 3). This step requires accurate characterization of the solids recovered after carbonation.

Examples of results obtained for the three steps are presented below, together with the potential and the limits of the direct process.

2.3 Pretreatment of olivine (Step 1)

Being both observed in olivine and in the carbonation products, chromite particles are not affected by high temperature carbonation. Various mechanical operations can be considered for the separation of chromite from olivine as magnetic or gravimetric separation [8,9]. Flotation of chromite, based on surface phenomena, has been extensively investigated for the recovery of fine particles in the range 25-100 μm [10,11]. In a previous study [7], flotation has been studied in a lab-scale column, using a sodium carbonate solution at pH 11 with cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTMAB). The enrichment ratio of chromite was found to be as large as 10 which demonstrated the potential of flotation for the recovery of chromite in a multistage flotation process [7].

Further, leaching of nickel for the pretreatment of olivine has been tested in view to purify the carbonation products. In various studies, dissolution of nickel contained in laterites (mixed iron and aluminium hydroxides and silicates) has been carried out using ammoniacal solutions [12,13], as for example in the Caron process. In China, the recovery of nickel from serpentine by leaching in ammonium carbonate solution was studied downstream the mineral carbonation [14]. Selective separation of metals and ammonia recycling were also included in the process proposed.

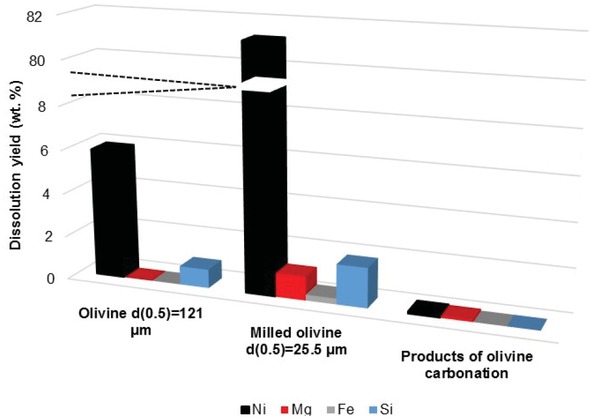

In the present study, leaching tests of nickel have been carried out with 6 M ammonium hydrogencarbonate solution at 70°C with three solids: GL30 olivine particles (d(0.5) = 121 μm), milled olivine (d(0.5) = 25.5 μm), and the solids formed by carbonation. In all tests, 5 g solids were treated in 100 mL ammoniacal solution under thorough stirring; three replicates were made for the three solids investigated. After leaching, the slurry has been separated by filtration; analysis of the liquid phase by ICP-OES

yielded the dissolution yield of the various elements. As shown in Figure 2, the dissolution yield of nickel was only 5% for GL30 olivine, whereas it attained 80% with the milled olivine. Nickel contained in the carbonation products could be dissolved at less than 0.1%, which confirmed the fact that nickel should be separated from olivine before carbonation in the direct process. Moreover, Mg, Fe and Si were very little dissolved (dissolution rate below 3%) which clearly shows the high selectivity of the leaching process. However, in spite of the above results, this solution cannot be considered at pilot/industrial scale because of the energy required in the milling operation, in addition to the complex ammonia recycling loop [14] to be implemented.

Dissolution yield of olivine and carbonation products using ammonia solution.

2.4 Carbonation and products separation: potential and limits (Steps 2 and 3)

The reaction has been investigated in a pilot tubular autoclave, developed by Innovation Concepts B.V. [5,15,16]. The system consists of a stainless steel tube 1 m long and 47 mm inside diameter, submitted to sudden rocking at regular intervals. The olivine used here was the pristine mineral, i.e. not treated by flotation. Carbonation tests have been carried out during 90 min, at 175°C and 100 bars with CO2, plus N2 as pressure driving gas. 600 g olivine were added to 1200 cm3 solution of 0.64 M sodium hydrogencarbonate, 0.5 M oxalic acid and 0.01 M ascorbic acid. The effects of the operating conditions presented in [5,6] have been evaluated on the carbonation yield.

The conversion yield of olivine has been estimated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), from the thermal decomposition of carbonates in the range 400-600°C.

Total weight loss in TGA for a completely converted (carbonated) olivine was calculated at 37% taking into account its equivalent stoichiometry given above. Previous results [6] have shown the limited carbonation because of inhibition phenomena of the reacting surface [5,6]. Conversion of GL30 olivine was found to slightly increase with time, up to 30% after 10 hour-long carbonation. The conversion also increased with the decrease in particle size, passing from 10% for GL 30 particles (120 μm) after 90 min. to 60% with 4 μm particles. However, in this case, the energy required for grinding increases from 58 kWh/t ≈ 3.1 €/t (120 μm) to 210 kWh/t ≈ 11.3 €/t (4 μm), which can hardly be considered at industrial scale.

The formation of a passivation layer has been evidenced on the surface of the unreacted olivine by SEM, EDX and DRX, as presented in [5,6]. This layer is mainly formed by a silica-based mineral, and considered as the limiting factor, leading to insufficient dissolution yield of particles over 10-20 μm as reported in most relevant papers.

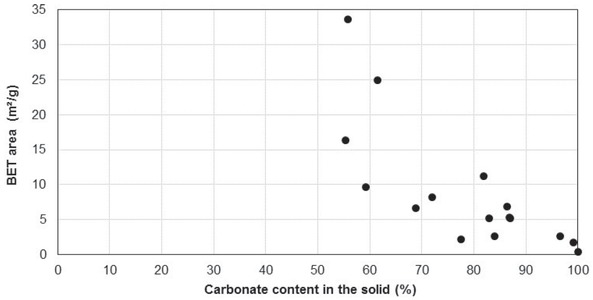

The solids obtained after Step 2 were shown to consist in a fine particles fraction below 106 μm and a coarser (residue) fraction [6]. The residue is principally formed by unreacted olivine, whereas the fine particles consist mainly of mixed Mg-Fe carbonates (mainly below 40 μm) and silica (over 40 μm): this segregation with particle size appears favourable for the separation of carbonation products. Nevertheless, the presence of coprecipitated particles of carbonate-silica also revealed by microscopic analysis, is to affect the efficiency of the separation operation.

The BET area of the fine particles fraction was shown to be a decreasing fraction of the carbonate fraction in this solid phase (Figure 3) with all the data obtained with various operating conditions. The BET area of very rich carbonate fractions was as low as 2,3 m2/g, a value far below the minimum level at 15 m2/g, recommended for applications in concrete [17]. Conversely, the values

BET area vs. and carbonate content in the fine particles for various operating conditions.

reached 35 m2/g for carbonation tests, with carbonate fractions lower than 60% in the fine particles. However, in this case, the products also included a significant fraction of unreacted olivine, corresponding to poorly efficient separation of the solids obtained by carbonation.

Although of fundamental interest, the results obtained by direct carbonation exclude any possible benefit from CO2 sequestration, mainly because of insufficient dissolution yields [6] and insufficient quality of the reaction products in terms of purity and surface area.

3 Indirect carbonation of olivine

3.1 Description of the overall indirect process

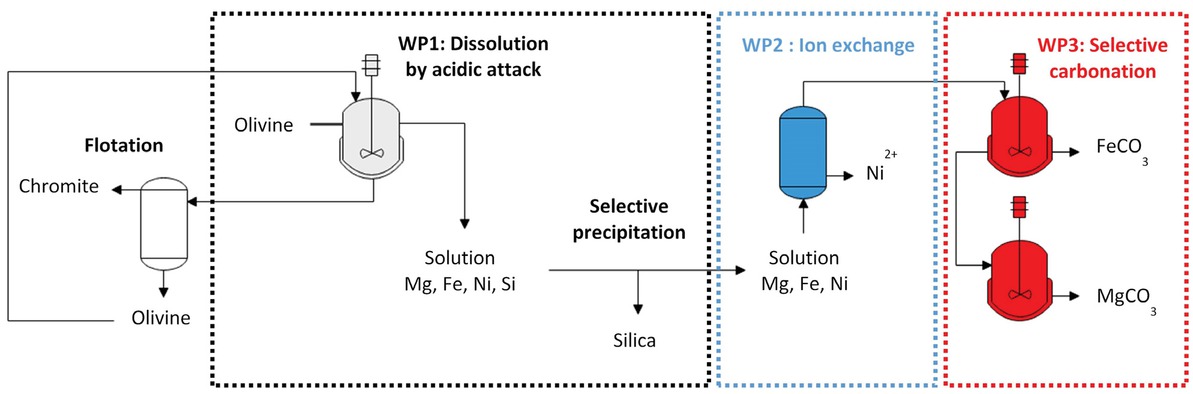

Indirect process can be considered as an alternative to the potential limits of direct carbonation which consists of the sequence of olivine dissolution by reaction with acidic solutions, followed by a series of separation and reaction steps [1]. For this purpose, an overall indirect route is currently investigated by the authoring teams for the production of highly valuable minerals, with the aim of profitable CO2 sequestration using reactive silicates. The presence of chromium- and nickel-based minerals can be valuable upon their efficient separation, but a potential hazard source otherwise. The overall process designed with the same olivine feedstock, consists of the following steps after the separation of chromite particles by flotation (Figure 4):

Schematic view of the process for CO2 sequestration by indirect carbonation of olivine.

Olivine particles are dissolved in a concentrated acidic solution (WP1), yielding an acidic solution of divalent magnesium, iron and nickel cations, and solid amorphous silica [18,20] which is gradually formed as the acid is consumed by the dissolution. Care had to be taken for a nearly complete dissolution with a minimum excess of acid and the recovery of concentrated metal cation solutions. The preparative formation of microporous silica particles with a high BET area has also been investigated in view to possible use in paper industry, tyre manufacturing or even as sorbent of inkjet paper.

First separation step of metal cations (WP2): the low contents of nickel have to be separated from the metal salt solution. In spite of the large fluxes of liquid solution to be treated, ion-exchange (IEX) technique has been selected because of existing, reliable technology and specific resins. Besides, the use of resins is also free from inherent drawbacks of solvent extraction processes or reactants use leading to subsequent pollution of the separated metal solution [21].

Selective carbonation and final separation of metal species (WP3). The slightly acidic solutions resulting from WP1 and WP2 have to be gradually neutralized by addition of slags acting as low-cost alkaline materials. The mixed Mg-Fe can be carbonated at approx. 200°C and under 20 bars CO2. However, two-stage process at two different pH levels is required for optimal separation, with intermediate addition of slag for pH increase.

Evaluation of technical and financial viability of the overall process, together with its integration in industrial areas have finally to be investigated. Examples of results obtained for WP1 (olivine dissolution and silica recovery) and WP2 (metal separation by ion exchange) are illustrated below.

3.2 Olivine dissolution in acid and silica recovery (WP1)

A literature survey has shown that olivine, in the form of a suspension of 10-100 μm, could be dissolved in a solution of hydrochloric or sulfuric acid at concentrations near 3 M, for temperatures ranging from 60 to 100°C [22,23]. Moreover, precipitation of silica in acidic media has been the subject of a number of studies [18,19,20], from which the experimental protocol could be defined.

Dissolution was extensively investigated in stirred vessels, with a volume of 250 mL (lab scale) or 1 L (pilot). Discontinuous tests have been made in 3 M sulfuric acid, under inert atmosphere to avoid undesired oxidation of divalent iron species, at solid-over-liquid (S/L) weight ratio varying from 80 to 180 g/L. Dissolution is nearly complete within a few hours, in agreement with formerly reported works [17,18,19]. Then, silica is formed in the reaction vessel by neutralization with NaOH, for pH in the range 1-2. Two fractions of solids have been recovered from the leaching reactor: the upper, lighter fraction corresponds mainly to silica, whereas the solids settled in the vessel (bottom fraction) contains also unreacted olivine [24].

As shown in Table 1, operation at 95°C with 20% of sulfuric acid excess allowed to obtain a conversion rate of 93% within 3 h. Silica nanoparticles (upper fraction) with a BET area near 500 m2/g have been recovered quantitatively which is promising for the future beneficiation of solids. After optimization of the lab scale dissolution, low excess of acid (12%) at 95°C, with 180 g/L olivine and a short reaction time (90 min) have been tested, with a conversion rate of 81%. In order to evaluate the potential of the process, dissolution of olivine has also been conducted in the larger stirred vessel for 3 h, under comparable conditions: olivine conversion attained 81% as shown by both analysis of the solid formed, and analysis of the concentrated resulting liquid phase to evaluate the mass balances in metal cations. For the three tests presented here BET area higher than 400 m2/gr has been found for the upper fraction which is promising for silica beneficiation [24].

Operating conditions and dissolution yield (Xdiss) of olivine.

| Parameters | S/L ratio (g/L) | Acid excess (%) | Time (min) | % Xdiss | % SiO2: Upper | % SiO2: Bottom | BET (m2/g): Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab scale | 80 | 20 | 180 | 93% | 96% | 56% | > 500 |

| Lab scale Optimization | 180 | 12 | 90 | 70% | 87% | 20% | 400 |

| Pilot | 180 | 12 | 180 | 81% | 93% | 23% | 440 |

3.3 First separation of metal cations by ion-exchange (WP2)

In the indirect route of carbonation process, the low contents of nickel have to be removed from the olivine leachate. For this purpose, separation by IEX has been studied. Several commercial resins have been screened for the separation of Ni2+ in an acidic solution. Chelating resins with the iminodiacetate functional group were reported to allow selective adsorption of nickel from tailings of pressure acid leaching plants but for pH of the feed solution near 4 or 5 [25]. In contrast, Dowex M-4195 ® resin can form complexes with transition metals in acidic solutions through their free electron pair-bearing nitrogen atom (bis-picolylamine group) [26,27]. Separation of nickel from sulfate or chloride solutions with this resin at pH below 3 was reported [26,28].

In this study, separation tests of nickel by IEX have been conducted with Dowex M-4195 ® resin, in a 150 mm long column being 15 mm in diameter and with a bed volume (BV) at 21 cm3. The resin was conditioned according to the recommendations of the manufacturer, by washing with deionized water and 1 M sulfuric acid to remove the impurities from the resin and to obtain a free base form. The feed solutions were injected in counter-current flow, using a peristaltic pump at 1 mL/min, i.e. nearly 3 BV/h. 64BV were run for the loading tests. ICP-OES analysis of the collected liquid fractions allowed the adsorption kinetics of Mg, Fe, Ni cations to be evaluated.

First, pure nickel solutions (5,87 g/L Ni) with various pH have been prepared to evaluate the capacity of the resin (Table 2). All tests have been conducted until saturation of the resin. For pH > 1.5, the capacity was in the range 0.810.89 eq/L, whereas it decreased to 0.48 eq/L at pH 1, in accordance with the literature [26].

Capacity of the resin depending on solution pH, with a 5.87 g/L Ni solution.

| Solution pH | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resin capacity (eq./L) | 0.48 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

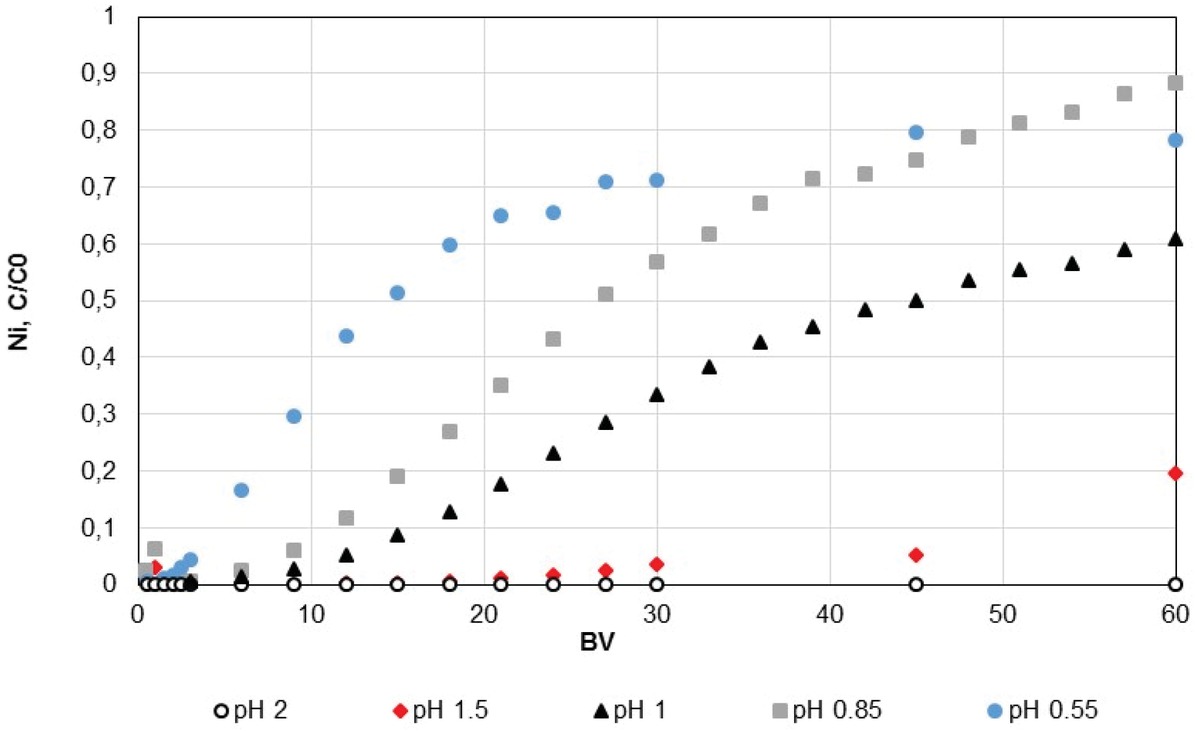

Feed solutions have been prepared with 0.025 g/L Ni, 0.5 g/L Fe, 2.7 g/L Mg: the respective proportions of metal cations are in accordance with those in the liquid phase to be issued from olivine dissolution. As expected, the adsorption of nickel cations on the resin was found to depend on the solution pH (Figure 5). After

Adsorption of nickel depending on pH of 25 ppm Ni, 2.7 g/L Mg, 0.5 g/L Fe solutions.

injection of the feed solution, the ratio of the nickel outlet concentration over the concentration of the feed solution (C/C0) was measured at 0, 0.19 and 0.61 after 64 BV, respectively at pH 2, 1.5 and 1. The results also confirmed the performances of the resin for a pH larger or equal to 1.5.

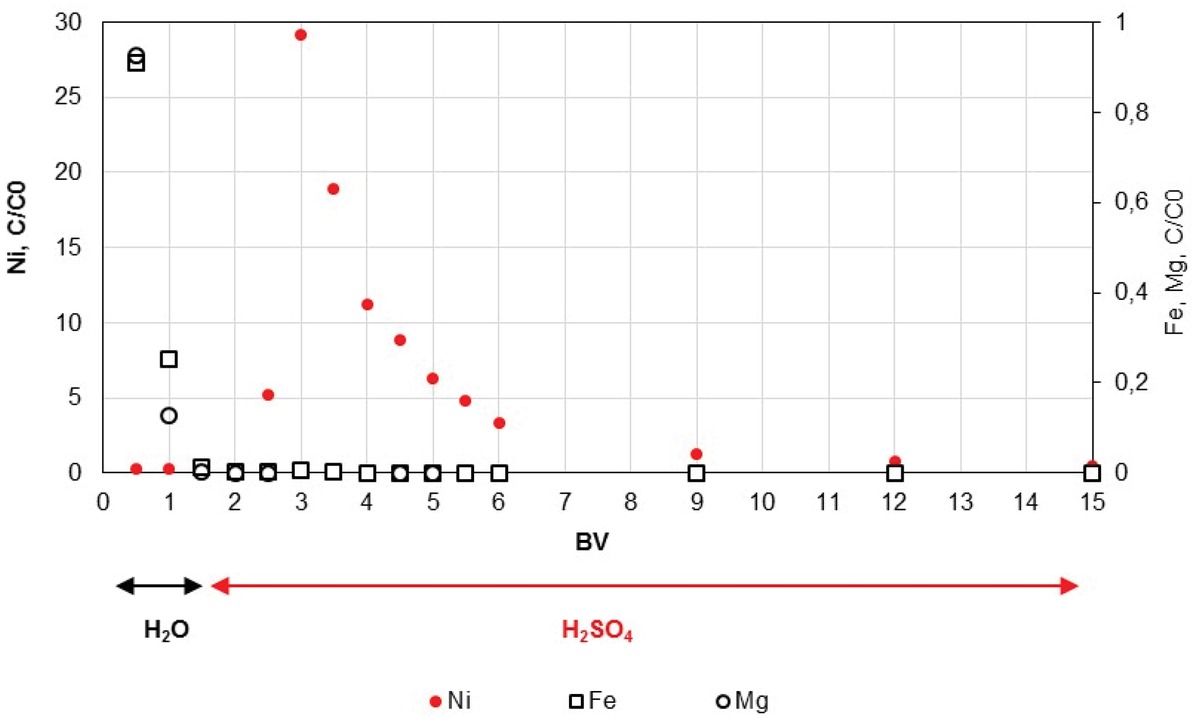

In the present work, both adsorption (loading) and desorption (elution) have been investigated. Before nickel desorption, a backwash step with 1.5 BV of deionized water through the column was conducted to remove impurities as Fe and Mg cations. One-molar sulfuric solution was then injected to recover Ni cations in the elution step. At pH 1.5 of the feed solution, the ratio C/C0 of nickel reached 30 after 1.5 BV with 1 M sulfuric acid (Figure 6). This value also expresses the enrichment factor of the eluate in comparison to the acidic solution to be treated. Mg and Fe were not detected after the backwash; moreover, the ratio C/C0 for Ni near 1 observed during the backwash corresponds to the dead volume.

Elution of nickel for solution containing 25 ppm Ni, 2.7 g/L Mg, 0.5 g/L Fe at pH 1.5.

These results confirmed the selectivity of the resin for nickel separation from the Mg-Fe solution.

The global yield of the various tests differing from the solution pH is presented in Table 3. For pH < 1, less than 60% of nickel could be separated. At pH 2, more than 90% of nickel was recovered in the sulfuric eluate, however with 0.4% of Fe2+ contained in the feed solution. Suitable conditions have been found for both nickel adsorption and production of single Ni solution at pH 1.5. This shows the potential of IEX for low concentrations of Ni cations. After the removal of Ni ions from the liquor solution, the Mg-Fe solution can either be driven to the carbonation stage or undergo a second IEX stage for the separation of iron species. However, because of the far larger content of Fe2+, iron carbonation should be preferred.

Overall yield of ion exchange depending on solution pH, using 25 ppm Ni, 2.7 g/L Mg, 0.5 g/L Fe.

| Over. yield % | pH 0.55 | pH 0.85 | pH 1 | pH 1.5 | pH 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Mg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ni | 22.5 | 42.4 | 59.1 | 85.3 | 93.1 |

The comparison between the two carbonation routes is summarized in Table 4. Although the direct process is of an easier implementation, the carbonation rate was limited by the passivation of the olivine surface. Moreover, the separation of carbonation products was limited by their coprecipitation. The indirect carbonation can allow high dissolution yields and leads to highly valuable silica, nickel salts, and separate iron and magnesium carbonates.

Comparison between direct and indirect carbonation routes.

| Carbonation | Direct process | Indirect process |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | – Carbonation reaction in one step | – Provide a high dissolution rate |

| – Easy to implement | – Production of high value added silica | |

| – Control of the operating conditions | ||

| – Selective carbonation | ||

| – Higher carbonation rate | ||

| – Improvement of the products separation | ||

| Drawbacks | – Limited Carbonation yield | – Requires several unit operations |

| – Passivation layer on olivine | ||

| – Coprecipitation of products | ||

4 Conclusion and further prospects

The possible reconciliation of reduction of CO2 emissions by its sequestration and the development of green processes for the production of valuable products has been considered in this study. We propose here an alternative to the conventional direct carbonation of olivine by an original process, whose various steps are still under investigation and development. Although some parts of the indirect route have to be validated e.g. iron and magnesium carbonations, the potential of the overall indirect process was demonstrated for the quantitative production of nanostructured silica and concentrated solutions of metal cations. Ion-exchange technique has been shown promising for the separation of low concentration Ni cations. For both tasks, the targets defined could be attained.

After experimental investigation of the carbonation step of divalent Fe and Mg cations, the overall process will

be evaluated in terms of energy demand and costs. Life cycle analysis has also to be conducted for assessment of its technical and environmental validity.

Acknowledgments

The study is a part of VALORCO project, coordinated by ArcelorMittal and funded by ADEME, to develop a steel industry with highly reduced carbon dioxide emissions. Thanks are also due to French Ministery of Research and Region Lorraine for co-funding most of the facilities used here, within the project “Sustainable Chemistry and Processes” (CPER Lorraine).

References

[1] IEA. Energy and Climate Change, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Leung D.Y.C., Caramanna G., Maroto-Valer M.M., An overview of current status of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev., 2014, 39, 426-443.10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.093Search in Google Scholar

[3] Olajire A.A., Valorization of greenhouse carbon dioxide emissions into value-added products by catalytic processes. J. CO2 Util., 2013, 3, 74-92.10.1016/j.jcou.2013.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[4] Huang S., Yan B., Wang S., Ma X., Recent advances in dialkyl carbonates synthesis and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2015, 44, 3079-3116.10.1039/C4CS00374HSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Monteiro J.G.M.-S., Araújo O. de Q.F., Medeiros J.L. de., Sustainability metrics for eco-technologies assessment, part I: preliminary screening. Clean. Technol. Envir., 2009, 11, 209-214.10.1007/s10098-008-0189-9Search in Google Scholar

[6] ADEME. Valorisation chimique du CO2 - Etat des lieux, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Tamboli A.H., Chaugule A.A., Kim H., Catalytic developments in the direct dimethyl carbonate synthesis from carbon dioxide and methanol. Chem. Eng. J., 2017, 323, 530-544.10.1016/j.cej.2017.04.112Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kindermann N., Jose T., Kleij A.W., Synthesis of Carbonates from Alcohols and CO2 Top. Curr. Chem., 2017, 375, 15.10.1007/978-3-319-77757-3_2Search in Google Scholar

[9] Tomishige K., Sakaihori T., Ikeda Y., Fujimoto K., A novel method of direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from methanol and carbon dioxide catalyzed by zirconia. Catal. Lett., 1999, 58, 225-229.10.1023/A:1019098405444Search in Google Scholar

[10] Wang S., Zhao L., Wang W., Zhao Y., Zhang G., Ma X., et al., Morphology control of ceria nanocrystals for catalytic conversion of CO2 with methanol. Nanoscale, 2013, 5, 5582-5588.10.1039/c3nr00831bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Tomishige K., Ikeda Y., Sakaihori T., Fujimoto K., Catalytic properties and structure of zirconia catalysts for direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from methanol and carbon dioxide. J. Catal., 2000, 192, 355-362.10.1006/jcat.2000.2854Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ikeda Y., Asadullah M., Fujimoto K., Tomishige K., Structure of the Active Sites on H3PO4/ZrO2 Catalysts for Dimethyl Carbonate Synthesis from Methanol and Carbon Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2001, 105, 10653-10658.10.1021/jp0121522Search in Google Scholar

[13] Jiang C., Guo Y., Wang C., Hu C., Wu Y., Wang E., Synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from methanol and carbon dioxide in the presence of polyoxometalates under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. A-Gen., 2003, 256, 203-212.10.1016/S0926-860X(03)00400-9Search in Google Scholar

[14] Honda M., Tamura M., Nakagawa Y., Sonehara S., Suzuki K., Fujimoto K., et al., Ceria-Catalyzed Conversion of Carbon Dioxide into Dimethyl Carbonate with 2-Cyanopyridine. ChemSusChem, 2013, 6, 1341-1344.10.1002/cssc.201300229Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jonquières A., Arnal-Hérault C., Babin J., Pervaporation. In: Hoeck E.M.V., Tarabara V.V., Encyclopedia of Membrane Science and Technology, 2013.10.1002/9781118522318.emst092Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jonquières A., Clément R., Lochon P., Néel J., Dresch M., Chrétien B., Industrial state-of-the-art of pervaporation and vapour permeation in the western countries. J. Membrane Sci., 2002, 206, 87-117.10.1016/S0376-7388(01)00768-2Search in Google Scholar

[17] Bolto B., Hoang M, Xie Z., A review of membrane selection for the dehydration of aqueous ethanol by pervaporation. Chem. Eng. Process, 2011, 50, 227-235.10.1016/j.cep.2011.01.003Search in Google Scholar

[18] Chapman P.D., Oliveira T., Livingston A.G., Li K., Membranes for the dehydration of solvents by pervaporation. J. Membrane Sci., 2008, 318, 5-37.10.1016/j.memsci.2008.02.061Search in Google Scholar

[19] Diban N., Aguayo A.T., Bilbao J., Urtiaga A., Ortiz I., Membrane Reactors for in Situ Water Removal: A Review of Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2013, 52, 10342-10354.10.1021/ie3029625Search in Google Scholar

[20] Izák P., Mateus N.M.M., Afonso C.A.M., Crespo J.G., Enhanced esterification conversion in a room temperature ionic liquid by integrated water removal with pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol., 2005, 41, 141-145.10.1016/j.seppur.2004.05.004Search in Google Scholar

[21] Dibenedetto A., Aresta M., Angelini A., Ethiraj J., Aresta B.M., Synthesis, Characterization, and Use of NbV/CeIV-Mixed Oxides in the Direct Carboxylation of Ethanol by using Pervaporation Membranes for Water Removal. Chem.-Eur. J., 2012, 18, 10324-10334.10.1002/chem.201201561Search in Google Scholar

[22] Li C.-F., Zhong S.-H., Study on application of membrane reactor in direct synthesis DMC from CO2 and CH3OH over Cu–KF/MgSiO catalyst. Catal. Today, 2003, 82, 83-90.10.1016/S0920-5861(03)00205-0Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kuenen H.J., Mengers H.J., Nijmeijer D.C., van der Ham A.G.J., Kiss A.A., Techno-economic evaluation of the direct conversion of CO2 to dimethyl carbonate using catalytic membrane reactors. Comput. Chem. Eng., 2016, 86, 136-147.10.1016/j.compchemeng.2015.12.025Search in Google Scholar

[24] Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Dutta A., Energy issues in the utilization of CO2 in the synthesis of chemicals: The case of the direct carboxylation of alcohols to dialkylcarbonates. Catal. Today, 2017, 281, Part 2, 345-351.10.1016/j.cattod.2016.02.046Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wang J., Hao Z., Wohlrab S., Continuous CO2 esterification to diethyl carbonate (DEC) at atmospheric pressure: Application of porous membranes for in-situ H2O removal. Green Chem., 2017, 19, 3595-3600.10.1039/C7GC00916JSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Wang Y., Jia D., Zhu Z., Sun Y., Synthesis of Diethyl Carbonate from Carbon Dioxide, Propylene Oxide and Ethanol over KNO3-CeO2 and KBr-KNO3-CeO2 Catalysts. Catalysts, 2016, 6, 52.10.3390/catal6040052Search in Google Scholar

[27] Shukla K., Srivastava V.C., Diethyl carbonate: critical review of synthesis routes, catalysts used and engineering aspects. RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 32624-32645.10.1039/C6RA02518HSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Yoshida Y., Arai Y., Kado S., Kunimori K., Tomishige K., Direct synthesis of organic carbonates from the reaction of CO2 with methanol and ethanol over CeO2 catalysts. Catal. Today, 2006, 115, 95-101.10.1016/j.cattod.2006.02.027Search in Google Scholar

[29] Yave W., Separation performance of improved PERVAP membrane and its dependence on operating conditions. J. Membrane Sci. Res. (in press), doi:10.22079/jmsr.2018. 88186.1198.10.22079/jmsr.2018.88186.1198Search in Google Scholar

[30] Santos B.A.V., Pereira C.S.M., Silva V.M.T.M., Loureiro J.M., Rodrigues A.E., Kinetic study for the direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from methanol and CO2 over CeO2 at high pressure conditions. Appl. Catal. A-Gen., 2013, 455, 219-226.10.1016/j.apcata.2013.02.003Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kumar P., With P., Chandra Srivastava V., Shukla K., Gläser R., Mani Mishra I., Dimethyl carbonate synthesis from carbon dioxide using ceria–zirconia catalysts prepared using a templating method: characterization, parametric optimization and chemical equilibrium modeling. RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 110235-110246.10.1039/C6RA22643DSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Hofmann H.J., Brandner A., Claus P., Direct Synthesis of Dimethyl Carbonate by Carboxylation of Methanol on Ceria-Based Mixed Oxides. Chem. Eng. Technol., 2012, 35, 2140-2146.10.1002/ceat.201200475Search in Google Scholar

[33] Baker R.W., Wijmans J.G., Huang Y., Permeability, permeance and selectivity: A preferred way of reporting pervaporation performance data. J. Membrane Sci., 2010, 348, 346-352.10.1016/j.memsci.2009.11.022Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Turri et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering