Abstract

A “reactive coupling” process for one-pot transesterification of rapeseed oil into fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) for biodiesel, and in situ acetalisation of the glycerol by-product to solketal was investigated by both an experimental and a kinetic modelling approach. The aim was to develop a process with a more valuable co-products than glycerol, and to minimise glycerol production. The results showed that a one-stage reactive coupling achieved a solketal yield of 39.5 ± 5.1% and FAME yield of 99% after 8 h at 10:7:1 of methanol: acetone: oil molar ratio. However, based on these results and the predictions of the kinetic model developed, a “two-stage” reactive coupling process was investigated, in which some of the acetone was added later in the process. The two-stage process was demonstrated to achieve up to 98 ± 0.5% FAME and 82 ± 4% solketal yields under the same operating conditions.

1 Introduction

Due to fossil fuel depletion and global warming, biofuel production has become significant over the last 25 years, in 2016 accounting for 351 kte in the UK [1]. Biodiesel is synthesised via the reaction of triglycerides, usually vegetable oils, with alkyl alcohols, usually methanol. The biodiesel (the fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) of the triglyceride) is the main product, but glycerol is a significant by-product (10-20% of biodiesel, by volume). Co-production of glycerol in the conventional biodiesel processes has little economic advantage for biodiesel manufacturers, as the huge rise in global glycerol production has caused its oversupply, significantly reducing the glycerol price [2]. Glycerol production is reported to have increased from 200,000 te in 2003, to over 2 Mte in 2011, and this is predicted to rise to over 6 Mte by 2025 [3]. One way to improve the economics of biodiesel production is to convert the glycerol into valuable products. Indeed, many alternatives have been suggested to utilize glycerol in many fields such as, animal food, drugs, cosmetics, tobacco, fuel additives, waste treatment and production of different chemicals [4, 5, 6]. Previous studies have shown that glycerol can be converted to many valuable chemicals such as 1,3-propanediol [7], citric acid [8], polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) [9], glycerol carbonate [10], glycerol ethers [11], fuel extender [12] and solketal [13].

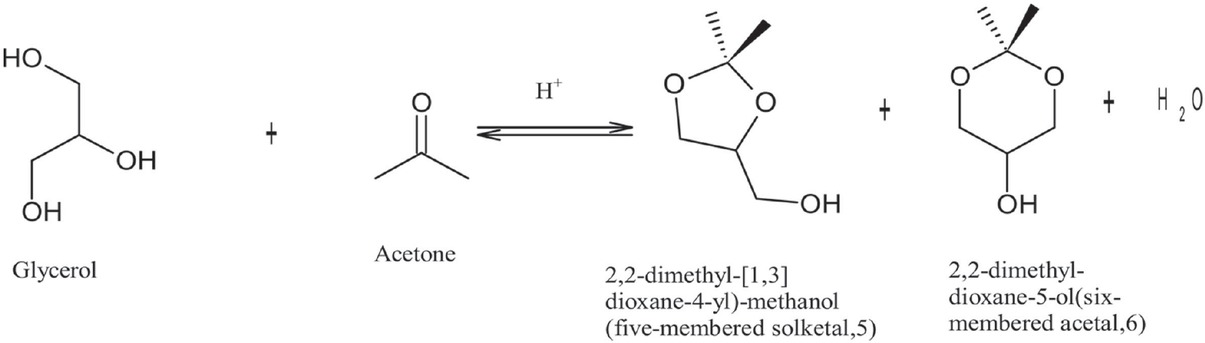

Solketal production is one of the most economical and promising ways of utilising glycerol. The process involves reacting the glycerol with acetone in the presence of an acid catalyst [13]. The reaction of acetone and glycerol to produce solketal is shown in Figure 1. Solketal is a valuable product used in the pharmaceutical industry and as a plasticizer in the polymer industry [14]. Another important future use is as an additive to improve biodiesel’s fuel properties by reducing its viscosity and improving fuel stability [15,16].

Acid-catalysed reactions of glycerol and acetone to produce solketal.

Although glycerol from the biodiesel process can be converted to valuable chemicals, glycerol recovery and upgrading requires various separation and purification steps. A previous study has shown that acetone can be used as a co-solvent in biodiesel production, to increase alcohol and oil miscibility [17]. However, the acetone must be separated from the final product [18], which increases costs. Applications of integrated process, such as reactive distillation [19] and reactive coupling [20], could be less expensive than conventional reaction for biodiesel production, and this technique could lead to reduction in the required equipment and energy. Solketal co-production through reactive coupling of triacetin transesterification with condensation of the glycerol by-product with acetone has been demonstrated in a recent study [20]. Although triacetin, a short chain triglyceride, was used, the study suggests that this could be of potential application to the long-chain (typically C14-C20) fatty acids found in naturally occurring vegetable oils. It is envisaged that a

modification of the biodiesel processing method, via in situ reactive coupling of glycerol condensation with acetone during triglyceride transesterification, could be applied to produce biodiesel and solketal, greatly reducing the glycerol production in biodiesel plants. In situ reactive coupling of glycerol by-product and acetone will changes the reaction rates and reaction equilibrium, and might be hoped to reduce the methanol recycling requirement.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Anhydrous methanol (99.8% purity), 2,2-dimethyl 1,3-dioxalane-4-methanol (solketal) (99% purity), acetone (98% purity), 4- Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA) (98% purity), 2-propanol (99% purity), methyl heptadecanaote (99% purity), glycerol (99% purity), triethylamine (99% purity) and high-purity grade silica gel (Davisil Grade 635, pore size 60 Å, 60-100 mesh) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The rapeseed oil (RSO) used was supplied from Henry Colbeck Ltd, UK.

2.2 Experimental methods

The process parameters for the coupling of glycerol transformation to solketal into biodiesel production reactions were investigated using a Design of Experiment statistics (DoE) at methanol to oil molar ratio of 10:1, 0.5 mole of DBSA catalyst per mole of the oil, acetone to oil molar ratio between 2:1-10:1, reaction times of 1-4 h and 0-100 wt% of silica gel as a dehydrating agent. Silica gel was added into the reaction mixture to remove reactively-formed water from the system, because of the thermodynamic equilibrium limitations in conversions of glycerol to solketal, due to the productions of water as a by-product [21]. The silica gel was activated by drying in a vacuum oven (OV-11/12) at 120°C for 24 h before use. The reactions were performed at a constant reaction temperature of 50°C, in a three-necked 250 mL batch reactor equipped with a heater-stirrer and ports for connections to a condenser, sampling port, and feed input/temperature probe.

A condenser was used to prevent acetone evaporation, and the entire system was sealed before starting the experiment. The acetone, methanol, RSO and catalyst were preheated in reservoirs inside hot water bath before they were transferred into the reaction vessel. The required amounts of acetone, methanol, RSO and silica gel were transferred into the batch reactor, and heated to the reaction temperature. This was followed by additions of the required amount of an acid catalyst. An organosulphonic acid (DBSA) was selected as the catalyst for this process because of its surfactant-like nature, high rate of reaction, and low corrosivity compared to mineral acid catalysts [22]. A preliminary investigation of the reaction showed that mixing speeds of 800 rpm or more were necessary to ensure that the reaction is mass-transfer independent. The reactants were mixed vigorously at 800 rpm and the reaction temperature of 50°C. Samples were collected for analysis at various time intervals, from 1-240 min. Minitab 17 statistical software (box Behnken design), with stepwise methodology, was applied to analyse the experimental results. Statistical models that describe the FAME and solketal yields (responses) were obtained from the experimental data analysis, as a function of the process variables.

A two-stage process for conversions of the RSO to FAME and solketal was also performed, by addition of acetone after the reaction has attained high RSO to FAME and glycerol conversions, in an attempt to compare with the one-stage process, and to maximise the glycerol to solketal conversions. The two-stage experiments consisted of an initial RSO transesterification at 10:1 methanol to oil molar ratio, 50°C temperature, 0.5:1 of catalyst to oil molar ratio, and reaction time of 4 h, followed by in situ acetalisation of the produced glycerol by addition of acetone at 4:1 acetone to RSO molar ratio and reacting for 4 h in the second step. The RSO transesterification in the first step was left to reach high FAME yields (near complete conversion), so that there could be high glycerol content in the reaction medium to increase the rate of acetalisation in the second step.

2.3 Sample analysis

All the samples collected were quenched with triethylamine immediately. Approximately 100-200 mg of each sample was weighed into a 2 mL of gas chromatography (GC) vials, and 1 mL of 10 gm/mL of methyl heptadecanoate (C17) prepared in 2-propanol was added to samples and the mixtures homogenised. The C17 was prepared by dissolving of 1000 mg of methyl heptadecanaote in a 100 mL of 2-propanol. A 5890 series Hewlett Packard gas chromatograph (GC) was used to analyse the prepared samples. The GC was equipped with a capillary column with dimensions of 30 m length, 0.32 mm inner diameter and 0.25 μm film thickness. The GC oven temperatures were programmed at: initial temperature of 60°C held for 4 min, followed by temperature ramp from 60°C to 250°C at a rate of 15°C/min, and held for 7 min. The analytes were calculated from their peak areas referenced against the internal standard. FAME contents in the samples were quantified using the BS EN 14103:2003 [23], whereas the solketal was quantified using calibration data obtained from the response factors of the solutions of solketal and the methyl heptadecanoate standard prepared in a 2-propanol. A solketal response factor against the methyl heptadecanoate standard was determined as 0.43. The conversions of FAME and solketal were calculated using Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, respectively.

Water contents of the samples were determined using a Coulometric Karl Fischer titrator (C30X Coulometer equipped with a generator cell without diaphragm, Mettler Toledo, UK), which measures water contents to 0.1 μg resolution. The titrator was calibrated using water standards (Karl Fischer Aqualine™ water standard, Fischer Scientific, UK) before it was used for the analysis. The measurements of the water contents of the samples were used to determine the effectiveness of the silica in removal of the reactively-formed water.

2.4 Kinetic model

Reaction kinetics for homogenous catalysis of triglyceride transesterification have been studied for acid (H2SO4) and base (NaOBu) catalysts, where a pseudo first-order reaction was reported at 30:1 alcohol-to-oil molar ratio, and second-order at 6:1 alcohol to oil molar ratio [24]. Transesterification of soybean oil and methanol at 6:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio using NaOH catalyst was reported to be initially mass transfer-controlled, followed by a kinetically controlled second-order reaction [25]. Methanolysis of palm oil at 6:1 molar ratio in the presence of KOH catalyst also has been shown to be second-order initially, followed by pseudo-first or zero-order kinetics [26]. However, it has been generally accepted that triglyceride transesterification occurs via three consecutive steps [27], as shown in Eq. 3-5, where: MA is methanol, TG is triglyceride, DG is diglyceride, MG is monoglyceride, and GL is glycerol. The overall reaction is shown in Eq. 6.

Overall reaction

Kinetic rate expressions for the triglyceride transesterification [28,29] are shown in Eq. 7-12 below, where rA is the rate of formation of species A (mol‧L-1‧s-1), [A] is the concentration of species A (mol‧L-1), and ki is the rate constants of the individual reaction steps (L‧mol-1‧s-1).

In a reactive coupling process, the kinetic rate expressions must be modified, due to the reaction of MG with acetone in Eq. 13 and reactions of glycerol with acetone shown in Eq. 14, where AC is acetone, and FA-solketal is fatty acid solketal.

The kinetic rate expressions of solketal, acetone, water, MG and GL can be described as below in Eq. 15-19.

Numerical simulations of the reaction kinetics was done using MATLAB ODE45 solver, based on Eq. 7-12 and Eq. 15-19, to obtain a model for the in situ reactive coupling of glycerol acetalisation to triglyceride transesterification. The initial rate constants used for the numerical modelling were obtained from an existing study for a vegetable oil transesterification [28], coupled with values determined from preliminary experiments between pure glycerol and solketal in the presence of DBSA catalyst. The model adjusts the initial rate constants to minimise the sum of squared errors (SSE < 0.05) between the experimental and the model predictions. The actual rate constants for the reactions were the computed k values that give best fit to the experimental data at minimised SSE [28]. The model was applied to predict the effects of catalyst concentrations, reaction temperature and residence time, on conversions of RSO to FAME and solketal, and these were validated using experimental data. The experimental and numerical modelling approaches were combined to identify the reaction conditions necessary for high FAME and solketal yields.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effects of process parameters on reactive coupling for FAME and solketal co-productions

Table 1 shows the RSO conversions to solketal and FAME at various acetone molar ratios, residence time, and silica loading, and fixed conditions of 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio, 0.5 of catalyst to oil molar

DoE model and the conversion of solketal and FAME.

| Operating parameters | Experimental conversion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone: | Residence | Silica loading: | Solketal | FAME yield |

| oil molar ratio | time (hr) | water (wt%) | yield (%) | (%) |

| 2 | 1 | 50 | 24 | 45 |

| 6 | 2.5 | 50 | 34 | 71.3 |

| 6 | 1 | 100 | 11 | 27 |

| 6 | 2.5 | 50 | 34 | 71.3 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 0 | 37 | 89 |

| 6 | 2.5 | 50 | 34 | 71.3 |

| 10 | 1 | 50 | 7.3 | 9 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 0 | 20 | 53 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 100 | 21 | 53 |

| 2 | 4 | 50 | 44 | 99.9 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 100 | 38 | 89 |

| 10 | 4 | 50 | 27.3 | 66 |

| 6 | 4 | 100 | 31.46 | 84 |

| 6 | 4 | 0 | 30.5 | 84 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 27 |

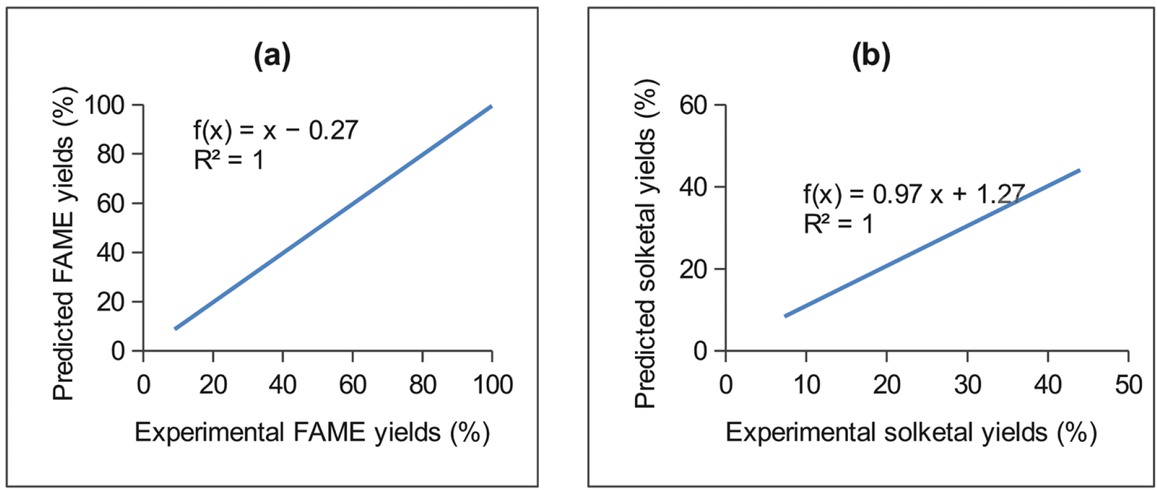

ratio and 50°C. The experimental data were analysed with Minitab 17, using the stepwise response surface method (box Behnken design), to evaluate the effects of the process conditions. The predictive models in Eq. 20 and Eq. 21 were generated from the experimental data for the conversions of the RSO to FAME and solketal respectively, where AMR is the acetone to RSO molar ratio, SL is the silica loading (wt%) based on the RSO, and t is the reaction time (h). The fit and the experimental data are shown in Figure 2 (R2 ≥ 0.99).

Plots of the experimental versus predicted values for (a) FAME and (b) solketal, for the DoE parametric screening of reaction variables in a single-stage reactive coupling of RSO conversions to FAME and solketal.

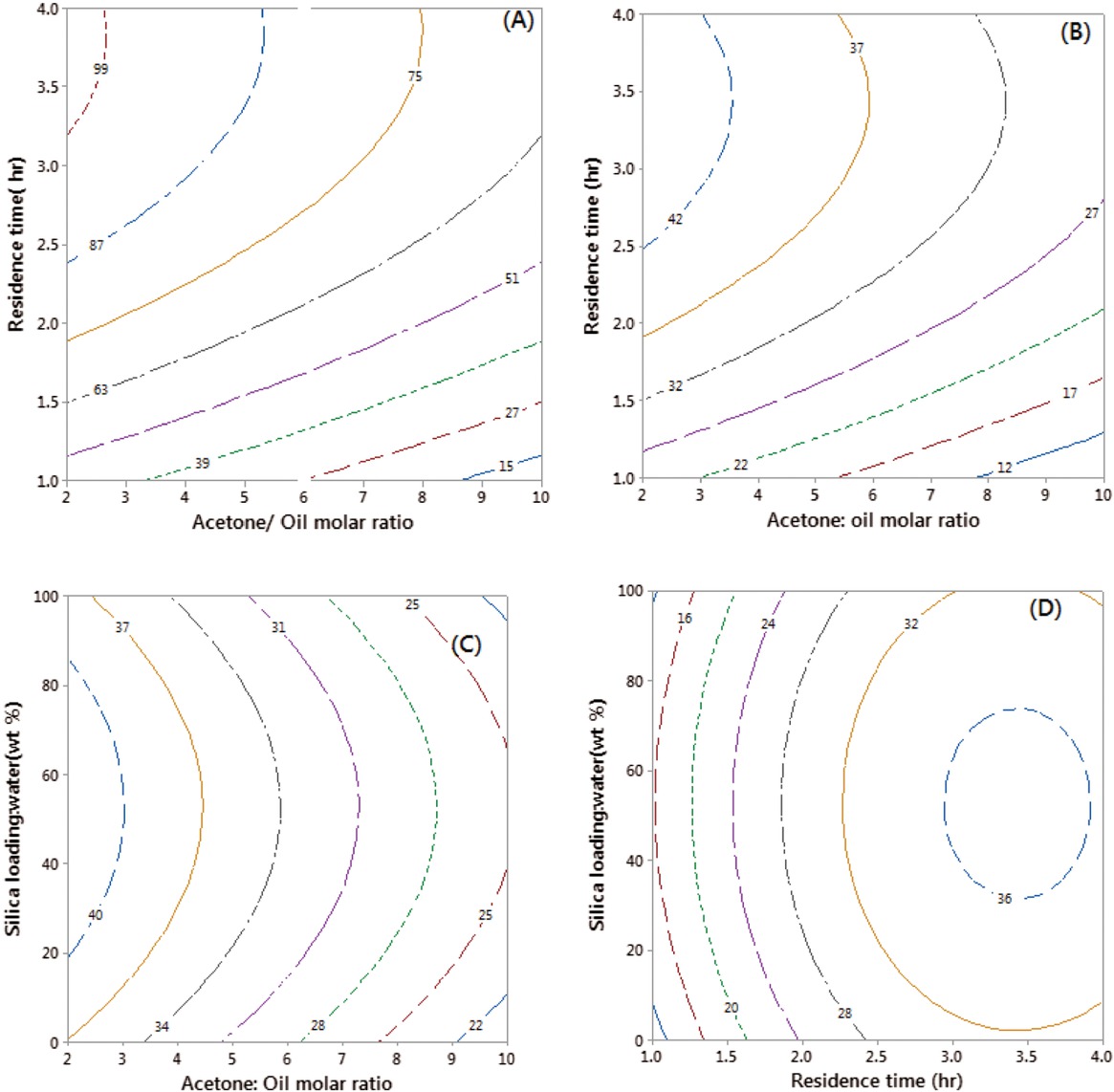

The effects of acetone to RSO molar ratio, residence time, and silica loading (wt%) on FAME and solketal productivity are shown in Figure 3. The contour plots in Figures 3a and 3b, show that 2:1 acetone to oil molar ratio was optimal value for both the FAME and solketal yields. The decrease in yield above this value was attributed to dilution of the reaction mixture by the excess acetone, which reduces reaction rates. Similar findings have been reported, where it was observed that large excesses of methanol and acetone could reduce the concentrations of glycerol, resulting in reduced reaction rates [20]. Silica gel was added as it can absorb water, so could remove the reactively- formed water, leading to higher solketal yields. As shown in Figures 3c and 3d, increasing the silica gel loading resulted in higher solketal yields, as expected. However, further addition of silica gel above 50 wt% did not increase the solketal yields, indicating that 50 wt% of silica loading could absorb substantial amounts of the reactively-formed water from the reaction system. Table 2 clearly shows the activity of silica in removal of the reactively formed water, indicating that 50 wt% of silica can remove of up to 83% of water produced in the system.

The effects of reaction time and acetone-to-RSO molar ratio on the yields of FAME (a) and solketal (b) for reactions at 50 wt% of silica gel loading / 1 mol RSO; and the effects of silica loading on the solketal yields, at different acetone molar ratios (c), and reaction times (d).

Water removal by silica for reactions at 2:1 of acetone to oil molar ratio, 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio, 0.5 mole of DBSA/1 mol RSO and 50°C.

| Time | Solketal | Expected2 HO | Measured H2O | H2O removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (min) | yield (%) | content (wt%) | content (wt%) | by Silica (wt%) |

| 0 | 0 | – | 0.71 | 0 |

| 30 | 5.88 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 3.87 |

| 60 | 15.61 | 2.13 | 0.79 | 63 |

| 120 | 32.06 | 4.37 | 0.81 | 81.45 |

| 180 | 39.26 | 5.35 | 0.97 | 82 |

| 240 | 44.10 | 6.01 | 0.98 | 83.7 |

The silica gel loading had no effect on the FAME yields, as illustrated by the empirical model in Eq. 20. It was observed that less than 45% conversion of the reactively-formed glycerol to solketal could be obtained even after 4 h reaction time using single-stage process. Complete online conversion of the glycerol produced from the RSO could not be achieved. This observation is consistent with an existing study which reported that even in acetalisation of pure glycerol, the acetalisation reaction is limited to 75-76% of solketal conversion by equilibrium [21].

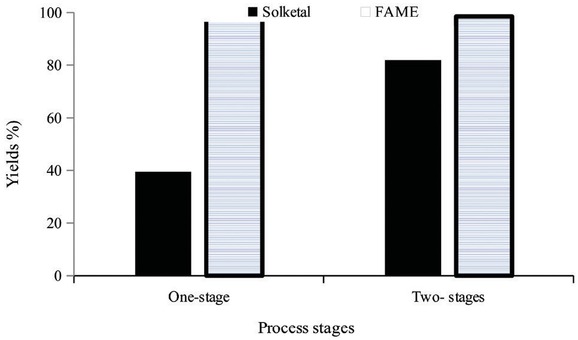

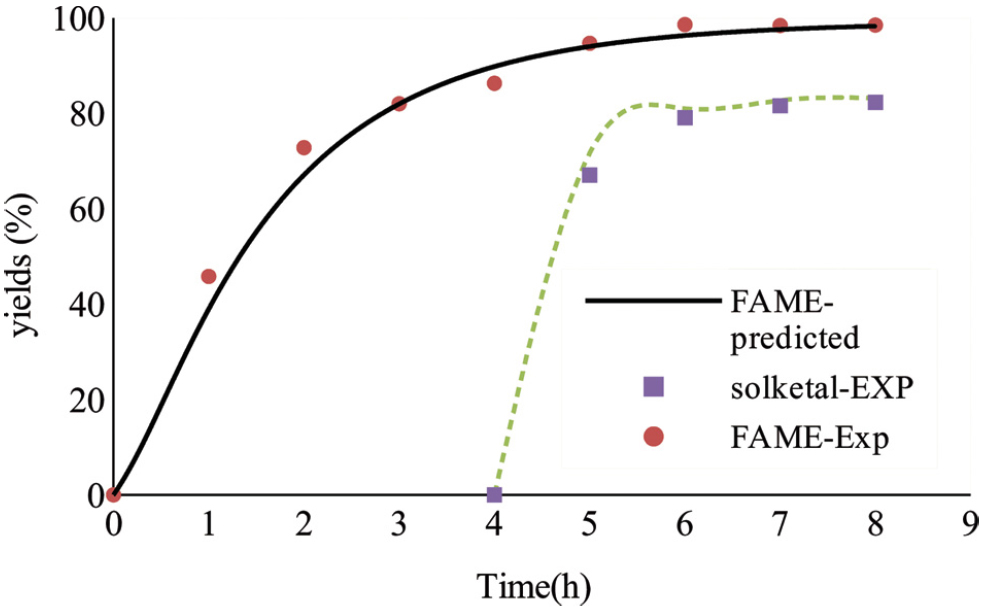

The one-stage and two-stage processes were compared at 7:1 of acetone to RSO molar ratio, 500C,8 h and 0.5 of DBSA to oil molar ratio (Figure 4). The results showed that a 39.5 ± 5.1% solketal yield was obtained from the one-stage process, as compared to 82 ± 4% for the two-stage process where acetone was added after 4 h. The FAME yields were ≥98 for both one-stage and two-stage processes

One- and two-stage processes for the reactive coupling of FAME and solketal co-productions at 7:1 of acetone to oil molar ratio, 0.5 of DBSA catalyst concentration, 50°C, 8 h and 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio.

It was observed that 97% of the solketal formed was of the cyclic five-membered acetal form, whereas the cyclic six-membered acetal constituted the remaining 3%. The proportions of the five- and six-membered cyclic acetals in this study are consistent with other reports: 98% selectivity of a five-membered ring (2,2-dimethyl-[1,3] dioxolan-4-yl) and 2% of six-membered ring (2,2-dimethyl-[1,3]dioxolan-4-yl) [15,30].

3.2 Kinetic model for reactive coupling of RSO transesterification with glycerol acetalisation

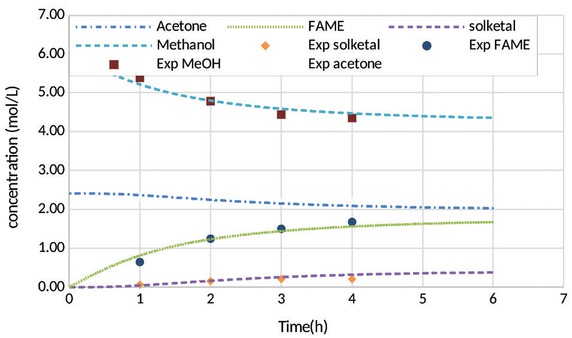

Based on the MATLAB model, the conditions required to achieve high solketal yields were identified. Figure 5, below, shows the experimental data and the model-predicted reaction profile, for the reactive coupling of biodiesel and solketal at acetone to rapeseed oil of 4:1 acetone molar ratio, 50°C, 10:1 of methanol to rapeseed oil molar ratio and 0.5 of catalyst to oil molar ratio. The model predictions (represented by dotted lines) closely match the experimental data (represented by data points).

Prediction by kinetic model at 50°C, 0.5 of catalyst to oil molar ratio, and (1:4) of oil to acetone molar ratio, 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio (One-stage).

The rate constants for the reactive coupling reaction of RSO transesterification with in situ by-product glycerol acetalisation using DBSA catalyst at 50°C reaction temperature are shown in Table 3. The rate constant for the DBSA catalyst was 163 times lower than the rate constant for base catalysis [28], but base catalysis is of course unsuitable for solketal production. Therefore, the reaction rate for the DBSA catalyst was 24 times higher than the sulphuric acid with reported rate of 4000 times less than base catalysts [31]. This has been attributed to the surfactant ability of the DBSA catalyst [22].

Theoretical and experimental values of equilibrium rate constants at 50°C, 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio, and 4:1 of acetone to oil molar ratio.

| Rate designation | aRate constants (L/mol‧s) * 10-4 | bRate constants (L/mol‧s) * 10-4 | K(Calc.) | K(Exp.) eq | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k= 2.47 1 | k= 0.237 2 | 9.82 | 10.42 | [32,33] | |

| k3 = 3.06 | k4 = 2.6 | 0.90 | 1.18 | [32,33] | |

| k 5 = 1.24 | k 6 = 0.728 | 0.02 | 1.70 | [32,33] | |

| k7 = 5.67 | k8 = 5.34 | 1.19 | 1.06 | [15] |

Note: aRate constants for forward reactions; b Rate constants for backward reactions.

The equilibrium rate constants (Keq) in Table 3 were obtained from the experimental rate constants and theoretically based on Gibbs free energy (ΔG). The theoretical Keq were calculated using Eq. 22 and Eq. 23, where ΔH is the enthalpy of formation, ΔS is the entropy of formation, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the reaction temperature in Kelvin. The value of ΔH and ΔS of each compound were obtained from existing studies [15,32,33]. Table 3 shows that the experimental Keq were substantially higher that the theoretical values from Gibbs free energies, except for the glycerol reaction with acetone. This could be attributed to the continuous removal of glycerol from the reaction mixture, which favours the forward reaction according to Le Chatelier’s principle. The continuous removal of glycerol by-product indicates that reactive coupling could potentially allow for reductions in the amount of methanol required for biodiesel productions. There was no enhancement in the Keq for the solketal formation, indicating that this reaction is limited by thermodynamic equilibrium”.

3.3 Validation of the kinetic model for reactive coupling of RSO transesterification

Figure 6 shows the RSO conversions to FAME and solketal for the two-stage process at the optimal process conditions determined from the DoE. This two-stage reactive coupling process was intended to maximise both the FAME and solketal yields. In the two-stage process, the RSO transesterification was allowed to reach complete conversion to achieve high glycerol concentration in the first stage, followed by addition of the required amount of acetone. It was observed that high solketal yield (82%) was achieved after 4 h reaction time (from adding acetone) or 8 h (total reaction time) (Figure 6) at 7:1 of acetone to oil molar ratio, which compares well with solketal yields reported elsewhere, when only using pure glycerol as reactant [30,34]. These results clearly demonstrated that adding acetone in the second stage (when high content of glycerol is formed) can lead to improve solketal yield compared to one-stage process. The experimental data for two–stage processes were used to validate the kinetic model predictions, and it was observed that there is a high agreement between them, indicating the reliability of the model as shown in Figure 6.

conversion of predicted and experimental values for reactive coupling of (solketal and FAME yield): two stage process, at 7:1 of acetone to oil molar ratio, 50°C, 10:1 of methanol to oil molar ratio and 0.5 of catalyst to oil molar ratio.

4 Conclusions

A novel process for combining triglyceride transesterification to FAME and in situ acetalisation of its glycerol by-product to solketal is reported. The aim of the study was to minimise or prevent co-production of crude glycerol, whilst maximising the solketal yield, to improve the economics of biodiesel production. A parametric study of the reactive coupling process was performed using DoE, to investigate the reaction parameters at acetone to glycerol (oil) molar ratio of 2:1 to 10:1; residence time of 1-4 h; and silica gel loading of 0 to 100 wt% based on the RSO. A two-stage process with delayed introduction of some of the acetone was also studied.

It was observed that silica loading had no effect on the FAME yield, but did increase the solketal yield, as it removes the reactively-formed water from the system by up to 83 %, thereby pushing the equilibrium towards higher glycerol to solketal conversion. Higher solketal yields were achieved using the two-stage process, with 82 ± 4% solketal yield, as compared to 39.5 ± 5.1% solketal yield for the one-stage. The one-stage and two-stage processes achieved (≥98%) FAME yields. Although acetone is required for the acetalisation of the glycerol, the excess acetone reduces rates of production of both biodiesel and solketal, due to dilution. This study also established a kinetic model for the reactive coupling of RSO transesterification and glycerol conversions to solketal. This model was validated using experimental data, and was successfully used to predict both FAME and solketal yields.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Higher Committee for Education Development in Iraq (HCED) for their financial support.

References

[1] Statistics, Biofuels production in selected countries in Europe in 2017. Statista - The portal for statistics, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rodrigues R., Isoda N., Gonçalves M., Figueiredo F.C.A., Mandelli D., Carvalho W.A., Effect of niobia and alumina as support for Pt catalysts in the hydrogenolysis of glycerol. Chem. Eng. J., 2012, 198-199, 457-467.10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ciriminna R., Pina C.D., Rossi M., Pagliaro M., Understanding the glycerol market. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech., 2014, 116, 1432-1439.10.1002/ejlt.201400229Search in Google Scholar

[4] Leoneti A.B., Aragão-Leoneti V., de Oliveira S.V.W.B, Glycerol as a by-product of biodiesel production in Brazil: Alternatives for the use of unrefined glycerol. Renew. Energ., 2012, 45, 138-145.10.1016/j.renene.2012.02.032Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yang F., Hanna M.A., Sun R., Value-added uses for crude glycerol a byproduct of biodiesel production. Biotechnol.Biofuels, 2012, 5:13.10.1186/1754-6834-5-13Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Knothe G., Krahl J., Van Gerpen J., The Biodiesel Handbook (2nd Ed.). Academic Press and AOCS Press, 2010.10.1201/9781003040262Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mu Y., Teng H., Zhang D.-J., Wang W., Xiu Z.-L., Microbial production of 1,3-propanediol by Klebsiella pneumoniae using crude glycerol from biodiesel preparations. Biotechnol. Lett., 2006, 28, 1755-1759.10.1007/s10529-006-9154-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Papanikolaou S., Muniglia L., Chevalot I., Aggelis G., Marc I., Yarrowia lipolytica as a potential producer of citric acid from raw glycerol. J. Appl. Microbiol., 2002, 92, 737-744.10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01577.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ashby R., Solaiman D.Y., Foglia T., Bacterial Poly(Hydroxyalkanoate) Polymer Production from the Biodiesel Co-product Stream. J. Polym. Environ., 2004, 12, 105-112.10.1023/B:JOOE.0000038541.54263.d9Search in Google Scholar

[10] Lertlukkanasuk N., Phiyanalinmat S., Kiatkittipong W., Arpornwichanop A., Aiouache F., Assabumrungrat S., Reactive distillation for synthesis of glycerol carbonate via glycerolysis of urea. Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensification, 2013, 70,103-109.10.1016/j.cep.2013.05.001Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kiatkittipong W., Intaracharoen P., Laosiripojana N., Chaisuk C., Praserthdam P., Assabumrungrat S., Glycerol ethers synthesis from glycerol etherification with tert-butyl alcohol in reactive distillation. Comput. Chem. Eng., 2011, 35, 2034-2043.10.1016/j.compchemeng.2011.01.016Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kiatkittipong W., Suwanmanee S., Laosiripojana N., Praserthdam P., Assabumrungrat S., Cleaner gasoline production by using glycerol as fuel extender. Fuel Process. Techn., 2010, 91456-91460.10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.12.004Search in Google Scholar

[13] Mota C.J.A., da Silva C.X.A., Rosenbach N., Costa J., da Silva F., Glycerin Derivatives as Fuel Additives: The Addition of Glycerol/Acetone Ketal (Solketal) in Gasolines. Energ. Fuel., 2010, 24, 2733-2736.10.1021/ef9015735Search in Google Scholar

[14] Nanda M.R., Yuan Z., Qin W., Ghaziaskar H.S., Poirier M.-A., Xu C., Catalytic conversion of glycerol to oxygenated fuel additive in a continuous flow reactor: Process optimization. Fuel, 2014, 128,113-119.10.1016/j.fuel.2014.02.068Search in Google Scholar

[15] Rossa V., Pessanha Y, Díaz G.C., Câmara L.D.T., Pergher S.B.C., Aranda D.A.G., Reaction Kinetic Study of Solketal Production from Glycerol Ketalization with Acetone. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2017, 56, 479-488.10.1021/acs.iecr.6b03581Search in Google Scholar

[16] Melero J.A., Vicente G., Morales G., Paniagua M., Bustamante J., Oxygenated compounds derived from glycerol for biodiesel formulation: Influence on EN 14214 quality parameters. Fuel, 2010, 89, 2011-2018.10.1016/j.fuel.2010.03.042Search in Google Scholar

[17] Alhassan Y., Kumar N., Bugaje I.M., Pali H.S., Kathkar P., Co-solvents transesterification of cotton seed oil into biodiesel: Effects of reaction conditions on quality of fatty acids methyl esters. Energ. Convers. Manage., 2014, 84, 640-648.10.1016/j.enconman.2014.04.080Search in Google Scholar

[18] Luu P.D., Takenaka N., Van Luu B., Pham L.N., Imamura K., Maeda Y., Co-solvent Method Produce Biodiesel form Waste Cooking Oil with Small Pilot Plant. Energy Proced., 2014, 61, 2822-2832.10.1016/j.egypro.2014.12.303Search in Google Scholar

[19] Petchsoongsakul N., Ngaosuwan K., Kiatkittipong W., Aiouache F., Assabumrungrat S., Process design of biodiesel production: Hybridization of ester-and transesterification in a single reactive distillation. Energ. Convers. Manage., 2017, 153, 493-503.10.1016/j.enconman.2017.10.013Search in Google Scholar

[20] Eze V.C., Harvey A.P., Continuous reactive coupling of glycerol and acetone – A strategy for triglyceride transesterification and in-situ valorisation of glycerol by-product. Chem. Eng. J., 2018, 347, 41-51.10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.078Search in Google Scholar

[21] Dmitriev G.S., Terekhov A.V., Zanaveskin L.N., Khadzhiev S.N., Zanaveskin K.L., Maksimov A.L., Choice of a catalyst and technological scheme for synthesis of solketal. Russ. J. Appl. Chem.+, 2016, 89, 1619-1624.10.1134/S1070427216100094Search in Google Scholar

[22] Alegría A., Arriba Á.L.F., Morán J.R., Cuellar J., Biodiesel production using 4-dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid as catalyst. Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2014, 160-161, 743-756.10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.06.033Search in Google Scholar

[23] BS EN 14103, Fat and oil derivatives - Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) for diesel engines - Determination of esters and linolenic acid methyl ester contents. In: British standerd. Chiswick High Road, London, 2003, 1-11.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Freedman B., Butterfield R., Pryde E., Transesterification kinetics of soybean oil 1. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 1986, 63, 1375-1380.10.1007/BF02679606Search in Google Scholar

[25] Noureddini H., Zhu D., Kinetics of transesterification of soybean oil. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc., 1997, 74, 1457-1463.10.1007/s11746-997-0254-2Search in Google Scholar

[26] Darnoko D., Cheryan M., Kinetics of palm oil transesterification in a batch reactor. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc., 2000, 77, 1263-1267.10.1007/s11746-000-0198-ySearch in Google Scholar

[27] Vicente G., Martínez M., Aracil J., Esteban A., Kinetics of sunflower oil methanolysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2005, 44, 5447-5454.10.1021/ie040208jSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Eze V.C., Phan A.N., Harvey A.P., A more robust model of the biodiesel reaction, allowing identification of process conditions for significantly enhanced rate and water tolerance. Bioresource Technol., 2014, 156, 222-231.10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Eze V.C., Phan A.N., Harvey A.P., Intensified one-step biodiesel production from high water and free fatty acid waste cooking oils. Fuel, 2018, 220567-220574.10.1016/j.fuel.2018.02.050Search in Google Scholar

[30] Menezes F.D.L., Guimaraes M.D.O., da Silva M.J., Highly Selective SnCl2-Catalyzed Solketal Synthesis at Room Temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2013, 52, 16709-16713.10.1021/ie402240jSearch in Google Scholar

[31] Boz N., Degirmenbasi N., Kalyon D.M., Esterification and transesterification of waste cooking oil over Amberlyst 15 and modified Amberlyst 15 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2015, 165, 723-730.10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.10.079Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zeng D., Li R., Jin T., Fang T., Calculating the Thermodynamic Characteristics and Chemical Equilibrium of the Stepwise Transesterification of Triolein Using Supercritical Lower Alcohols. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2014, 53, 7209-7216.10.1021/ie402811nSearch in Google Scholar

[33] Kieffer W.F., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 54th Edition. J. Chem. Ed., 1975, 52, A142.10.1021/ed052pA142.1Search in Google Scholar

[34] Nandan D., Sreenivasulu P., Sivakumar Konathala L.N., Kumar M., Viswanadham N., Acid functionalized carbon–silica composite and its application for solketal production. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2013, 179, 182-190.10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.06.004Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Al-Saadi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Studies on the preparation and properties of biodegradable polyester from soybean oil

- Flow-mode biodiesel production from palm oil using a pressurized microwave reactor

- Reduction of free fatty acids in waste oil for biodiesel production by glycerolysis: investigation and optimization of process parameters

- Saccharin: a cheap and mild acidic agent for the synthesis of azo dyes via telescoped dediazotization

- Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of polyethylene glycol stearate in a solvent-free system

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Platanus orientalis leaf extract for antifungal activity

- Ultrasound assisted chemical activation of peanut husk for copper removal

- Room temperature silanization of Fe3O4 for the preparation of phenyl functionalized magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction for the extraction of phthalates in water

- Evaluation of the saponin green extraction from Ziziphus spina-christi leaves using hydrothermal, microwave and Bain-Marie water bath heating methods

- Oxidation of dibenzothiophene using the heterogeneous catalyst of tungsten-based carbon nanotubes

- Calcined sodium silicate as an efficient and benign heterogeneous catalyst for the transesterification of natural lecithin to L-α-glycerophosphocholine

- Synergistic effect between CO2 and H2O2 on ethylbenzene oxidation catalyzed by carbon supported heteropolyanion catalysts

- Hydrocyanation of 2-arylmethyleneindan-1,3-diones using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) as a nontoxic cyanating agent

- Green synthesis of hydratropic aldehyde from α-methylstyrene catalyzed by Al2O3-supported metal phthalocyanines

- Environmentally benign chemical recycling of polycarbonate wastes: comparison of micro- and nano-TiO2 solid support efficiencies

- Medicago polymorpha-mediated antibacterial silver nanoparticles in the reduction of methyl orange

- Production of value-added chemicals from esterification of waste glycerol over MCM-41 supported catalysts

- Green synthesis of zerovalent copper nanoparticles for efficient reduction of toxic azo dyes congo red and methyl orange

- Optimization of the biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Penicillium oxalicum GRS-1 and their antimicrobial effects against common food-borne pathogens

- Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions to overproduce bioethanol using two industrial and traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

- Extraction of In3+ and Fe3+ from sulfate solutions by using a 3D-printed “Y”-shaped microreactor

- Foliar-mediated Ag:ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity

- Green cyclic acetals production by glycerol etherification reaction with benzaldehyde using cationic acidic resin

- Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities assessment of fabricated selenium nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- Synthesis of high surface area magnesia by using walnut shell as a template

- Controllable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinobacterial strains

- Green vegetation: a promising source of color dyes

- Mechano-chemical synthesis of ammonia and acetic acid from inorganic materials in water

- Green synthesis and structural characterization of novel N1-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones

- Biodiesel production from cotton oil using heterogeneous CaO catalysts from eggshells prepared at different calcination temperatures

- Regeneration of spent mercury catalyst for the treatment of dye wastewater by the microwave and ultrasonic spray-assisted method

- Green synthesis of the innovative super paramagnetic nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and their application for the decolourisation of toxic dyes

- Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: a study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight

- Leached compounds from the extracts of pomegranate peel, green coconut shell, and karuvelam wood for the removal of hexavalent chromium

- Enhancement of molecular weight reduction of natural rubber in triphasic CO2/toluene/H2O systems with hydrogen peroxide for preparation of biobased polyurethanes

- An efficient green synthesis of novel 1H-imidazo[1,2-a]imidazole-3-amine and imidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazole-5-amine derivatives via Strecker reaction under controlled microwave heating

- Evaluation of three different green fabrication methods for the synthesis of crystalline ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium zonale leaf extract

- A highly efficient and multifunctional biomass supporting Ag, Ni, and Cu nanoparticles through wetness impregnation for environmental remediation

- Simple one-pot green method for large-scale production of mesalamine, an anti-inflammatory agent

- Relationships between step and cumulative PMI and E-factors: implications on estimating material efficiency with respect to charting synthesis optimization strategies

- A comparative sorption study of Cr3+ and Cr6+ using mango peels: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic

- Effects of acid hydrolysis waste liquid recycle on preparation of microcrystalline cellulose

- Use of deep eutectic solvents as catalyst: A mini-review

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of pyrrolidinone derivatives using 1,1’-butylenebis(3-sulfo-3H-imidazol-1-ium) chloride in ethylene glycol

- Green and eco-friendly synthesis of Co3O4 and Ag-Co3O4: Characterization and photo-catalytic activity

- Adsorption optimized of the coal-based material and application for cyanide wastewater treatment

- Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains

- Waste phenolic resin derived activated carbon by microwave-assisted KOH activation and application to dye wastewater treatment

- Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana

- Agricultural waste biomass-assisted nanostructures: Synthesis and application

- Biodiesel production from rubber seed oil using calcium oxide derived from eggshell as catalyst – optimization and modeling studies

- Study of fabrication of fully aqueous solution processed SnS quantum dot-sensitized solar cell

- Assessment of aqueous extract of Gypsophila aretioides for inhibitory effects on calcium carbonate formation

- An environmentally friendly acylation reaction of 2-methylnaphthalene in solvent-free condition in a micro-channel reactor

- Aegle marmelos phytochemical stabilized synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles and their role against agriculture and food pathogen

- A reactive coupling process for co-production of solketal and biodiesel

- Optimization of the asymmetric synthesis of (S)-1-phenylethanol using Ispir bean as whole-cell biocatalyst

- Synthesis of pyrazolopyridine and pyrazoloquinoline derivatives by one-pot, three-component reactions of arylglyoxals, 3-methyl-1-aryl-1H-pyrazol-5-amines and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of tetrapropylammonium bromide

- Preconcentration of morphine in urine sample using a green and solvent-free microextraction method

- Extraction of glycyrrhizic acid by aqueous two-phase system formed by PEG and two environmentally friendly organic acid salts - sodium citrate and sodium tartrate

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Juglans regia leaf extract and assessment of their physico-chemical and biological properties

- Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as powerful and recyclable catalysts and solvents for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones

- Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-microbial activity of silver nanoparticle based gel hand wash

- Efficient and selective microwave-assisted O-methylation of phenolic compounds using tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)

- Anticoagulant, thrombolytic and antibacterial activities of Euphorbia acruensis latex-mediated bioengineered silver nanoparticles

- Volcanic ash as reusable catalyst in the green synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines

- Green synthesis, anionic polymerization of 1,4-bis(methacryloyl)piperazine using Algerian clay as catalyst

- Selenium supplementation during fermentation with sugar beet molasses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase bioethanol production

- Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication

- Investigating the effectiveness of classical and eco-friendly approaches for synthesis of dialdehydes from organic dihalides

- Pyrolysis of palm oil using zeolite catalyst and characterization of the boil-oil

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract assisted green synthesis of Ag-TiO2 for degradation of Methylene blue and Rhodamine B dyes in aqueous medium

- Synthesis of vitamin E succinate catalyzed by nano-SiO2 immobilized DMAP derivative in mixed solvent system

- Extraction of phytosterols from melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by supercritical CO2 as a clean technology

- Production of uronic acids by hydrothermolysis of pectin as a model substance for plant biomass waste

- Biofabrication of highly pure copper oxide nanoparticles using wheat seed extract and their catalytic activity: A mechanistic approach

- Intelligent modeling and optimization of emulsion aggregation method for producing green printing ink

- Improved removal of methylene blue on modified hierarchical zeolite Y: Achieved by a “destructive-constructive” method

- Two different facile and efficient approaches for the synthesis of various N-arylacetamides via N-acetylation of arylamines and straightforward one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes promoted by recyclable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles in water

- Optimization of acid catalyzed esterification and mixed metal oxide catalyzed transesterification for biodiesel production from Moringa oleifera oil

- Kinetics and the fluidity of the stearic acid esters with different carbon backbones

- Aiming for a standardized protocol for preparing a process green synthesis report and for ranking multiple synthesis plans to a common target product

- Microstructure and luminescence of VO2 (B) nanoparticle synthesis by hydrothermal method

- Optimization of uranium removal from uranium plant wastewater by response surface methodology (RSM)

- Microwave drying of nickel-containing residue: dielectric properties, kinetics, and energy aspects

- Simple and convenient two step synthesis of 5-bromo-2,3-dimethoxy-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil

- The effect of activation temperature on structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation

- Optimization of reaction parameters for the green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles using pine tree needles

- Microwave-assisted protocol for squalene isolation and conversion from oil-deodoriser distillates

- Denitrification performance of rare earth tailings-based catalysts

- Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi L and Plum extracts and investigation on the synergistic bioactivity using in vitro models

- Green production of AgNPs and their phytostimulatory impact

- Photocatalytic activity of Ag/Ni bi-metallic nanoparticles on textile dye removal

- Topical Issue: Green Process Engineering / Guest Editors: Martine Poux, Patrick Cognet

- Modelling and optimisation of oxidative desulphurisation of tyre-derived oil via central composite design approach

- CO2 sequestration by carbonation of olivine: a new process for optimal separation of the solids produced

- Organic carbonates synthesis improved by pervaporation for CO2 utilisation

- Production of starch nanoparticles through solvent-antisolvent precipitation in a spinning disc reactor

- A kinetic study of Zn halide/TBAB-catalysed fixation of CO2 with styrene oxide in propylene carbonate

- Topical on Green Process Engineering