Abstract

Iron–carbon microelectrolysis was employed to remove phosphorus in this study. The efficiency, mechanism, influence factors, and feasibility of actual wastewater were investigated. The results showed that iron–carbon microelectrolysis had an excellent phosphorus removal ability. When the initial concentration of

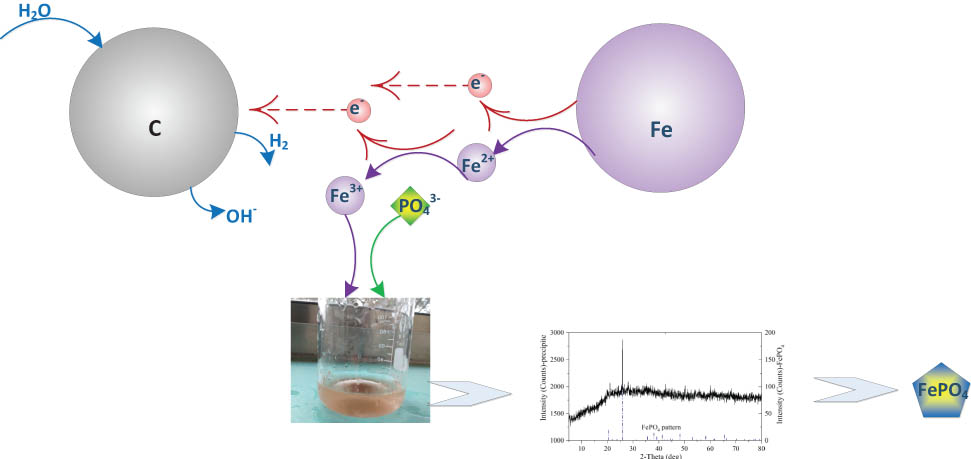

Graphical abstract

Iron–carbon microelectrolysis has an excellent phosphorus removal ability. The precipitate formed in the reaction was mainly ferric phosphate (FePO4) which had a high recovery value.

Natural water body eutrophication is caused by wastewater discharge that contains nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) [1,2], while P is considered a limiting factor of eutrophication because most lakes are P limitation [3,4]. It is generally considered that eutrophication occurs when the total nitrogen and total phosphorus (TP) in water are more than 0.2 and 0.02 mg·L−1, respectively [5]. On the other hand, P is a necessary nutriment for the development of life, constituting one of the major nutrients vital for agriculture [6]. However, the quantities of mineral P resources (phosphate rock) are decreasing in the world, making P recovery necessary to solve the P shortage [6,7]. Therefore, many research studies are now focusing increasingly on P recovery from wastewater.

P Recovery is a feasible and valuable technique which is suited to high-strength wastewater such as anaerobic sludge digestion and high P industry wastewater [8,9]. P is easily removed by chemical precipitation. Insoluble calcium, magnesium, and iron phosphates can be formed by pH control and chemical dosing, which precipitate at the bottom of specific reactors [10,11]. However, chemical dosing means the operation cost and is not an environmentally friendly approach. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) and ferric iron (Fe3+) can react with phosphate to form insoluble phosphate precipitation. In recent years, iron has been developed as a promising cost-effective chemical dosage considering both its high P removal efficiency and low commercial price [12,13,14]. Zhang et al. reported an application of in situ electrochemical generation of ferrous (Fe(ii)) ions for phosphorus (P) removal in wastewater treatment; at concentrations typical of municipal wastewater, P could be removed by in situ Fe(ii) with removal efficiency higher than achieved on the addition of FeSO4 and close to that of FeCl3 under both anoxic and oxic conditions [15]. But an electric field should be applied for in situ Fe2+ generation with direct current, which meant energy consumption.

Because of the advantages of treating waste with waste, the phosphorus removal technology of inorganic phosphorus removal filler (represented by fly ash ceramsite, water supply sludge ceramsite, calcium-silica filter material, and so on) has developed rapidly [16,17]. Among these inorganic fillers, the iron–carbon (Fe–C) micro-electrolysis method is to treat wastewater by forming a galvanic cell reaction in the electrolyte solution through the mixture of iron chips and coke or iron–carbon composite materials under the condition of no electricity. The removal of pollutants is completed by the primary cell reaction, flocculation precipitation, oxidation–reduction, electrochemical enrichment, physical adsorption, and other processes [18,19]. The research studies of Fe–C microelectrolysis technology mostly focus on the improvement of the biodegradability of refractory organic wastewater and the treatment efficiency of some industrial wastewater as a pretreatment unit combined with biochemical treatment process [18,19], ignoring the research of phosphorus removal of iron–carbon micro-electrolysis. In this study, iron filings acquired from a machine processing factory were used as the chemical dosage combined with activated carbon to achieve efficient P recovery via iron–carbon (Fe–C) microelectrolysis in situ. The mechanism, recovery efficiency, and feasibility of actual wastewater were investigated, providing an environmental and sustainable way for P removal and recovery.

The efficiency of Fe–C microelectrolysis on P removal from synthetic wastewater is shown in Figure 1. The initial concentration of

P Removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis.

Fe–C microelectrolysis was a common galvanic cell reaction and was explicated for many years [21,22,23]. Fe was the anode, and the reaction was:

C was the cathode, and the reaction was:

Because the above reactions were simultaneous, Fe2+ from Eq. 1 and H2O2 from Eq. 5 could react as:

It was Fenton's reaction. Moreover, the products from the above reactions, such as ˙OH, [H], Fe2+, Fe3+, could react with many pollutants in wastewater [24,25]. Galvanic cell reaction, flocculation–sedimentation, oxidation–reduction, electrochemical enrichment, and physical adsorption were the micro-process which was with high efficiency and wide application in water treatment.

As to P removal, Fe2+, Fe3+ could react with phosphate to form ferrous phosphate (Fe3(PO4)2·8H2O) and ferric phosphate (FePO4), respectively (as shown in Figure 2) [25,26]. In order to determine the main product from Fe–C microelectrolysis, X-ray diffraction analysis was employed to detect the precipitate formed after the reaction, and the diffractogram is presented in Figure 3. A number of distinct rays indicate the presence of crystalline forms. By comparison with reference spectra, most of the peaks, and in particular the bigger ones, coincided with those of ferric phosphate (FePO4).

Schematic diagram of Fe–C microelectrolysis mechanism.

XRD Pattern of Fe–C microelectrolysis P removal precipitates.

The above reaction provided a new way of P removal and recovery way for high P wastewater. Through Fe–C microelectrolysis pretreatment, not only could the biodegradability of raw water be improved, but also P could be removed, reducing the N and P simultaneous removal pressure of subsequent biochemical treatment units. Moreover, the contradiction of N and P simultaneous removal in low C/N ratio wastewater could be relieved [27,28].

The product, FePO4, was a raw material to make lithium iron phosphate batteries, catalysts, and ceramics, and had a high recovery value. Nowadays, one of the most important uses of FePO4 was to make lithium iron phosphate batteries [29,30]. With the rapid development of the electric vehicle industry, China became the largest consumer market of lithium iron phosphate in the world. Especially from 2012 to 2013, the sales volume of lithium iron phosphate in China was about 5,797 tons, accounting for more than 50% of global sales. Therefore, FePO4, the precipitate of P removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis, had a high recycling value.

The initial

Influence of initial P on P removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis.

Salinity was one of the common pollutants in industrial wastewater and also one of the limiting factors in industrial wastewater treatment [31,32]. When the initial

Influence of salinity on P removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis.

The influence of salinity on P removal velocity is shown in Figure 5. In the range of 0–10 g·L−1 salinity, the reaction rate decreased rapidly with the increment of salinity. When the salinity was 10 g·L−1, the reaction rate was 0.20 mg·L−1·min−1, and only 51.28% of that when the salinity was 0 g·L−1. The reaction rate was 0.14 mg·L−1·min−1, when the salinity was 25.00 g·L−1, which was 70.00% of the reaction rate when the salinity was 10.00 g·L−1. The fitting curve showed that the P removal velocity by Fe–C microelectrolysis decreased exponentially under the influence of salinity (R 2 = 0.9795). The results showed that the salinity had an obvious inhibition on P removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis, and the salinity range of wastewater suitable for P removal by Fe–C microelectrolysis was 0–10 g·L−1.

In order to verify the feasibility of P removal from actual wastewater, the influent of WWTP, effluent of SST, and actual high salinity wastewater were treated by Fe–C microelectrolysis. The results are shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that the phosphorus removal rate of Fe–C microelectrolysis for these three types of wastewaters is relatively high and stable, and the removal rate is 88.37 ± 0.44%, 89.78 ± 1.88%, and 94.23 ± 0.16%, respectively (water samples were taken every other day, and the average value of the three experiments). Even if the salinity of raw water was greater than 20.00 g·L−1, the Fe–C microelectrolysis process showed excellent TP removal capacity. The results indicated that Fe–C microelectrolysis also had a good P removal effect on the actual industrial wastewater, so it was worth further research and promotion. There was no aeration and denitrification in the reaction process, so

P removal efficiency by Fe–C microelectrolysis in different types of wastewater.

P Removal by microelectrolysis was achieved in this study and might be a new way to P recovery; 76.05% removal rate was achieved under the initial concentration of

Experimental

Material preparation

Activated carbon (AR), bought from Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China), was washed with deionized water, dried at 105℃, and cooled for standby. Iron filings, acquired from Linyi Taiping Machine Processing Factory (Linyi Shandong, China), were soaked in 1 mol·L−1 NaOH solution for 5 min to remove the dirt on the surface and then washed to neutral with deionized water, then soaked in 1% hydrochloric acid for 5 min to remove the oxide film on the surface, and finally washed to neutral with deionized water for immediate using.

Synthetic P-containing wastewater was prepared by adding K2HPO4 to tap water. The mechanism, efficiency, and influencing factors of P recovery were studied with synthetic wastewater. The feasibility of P removal from actual wastewater was investigated by using the influent of municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) and the effluent of secondary sedimentation tank (SST). The influent of WWTP and the effluent of SST were collected from the water inlet and the SST outlet in a municipal wastewater treatment plant in Zaozhuang City (Zaozhuang Shandong, China). High salinity wastewater (high COD and >20.00 g·L−1 salinity (NaCl) on average) was collected from a pickle factory in Lanling County, Linyi City (Linyi Shandong, China).

Experiment operation

Into a 250 mL flask, 100 mL P containing wastewater was put. The flask was placed on a magnetic stirrer at room temperature (20 ± 0.5℃, 200 rpm). Added prepared iron–carbon filings to the flask according to test requirements. After the reaction, the filtrate was filtered to measure P concentration.

Measurement and analysis methods

Samples of the solution were taken at fixed times according to the experiment plan with one of these samples filtered immediately through a membrane with 0.45 μm pore size. Analysis of the filtrate was conducted immediately. The concentrations of chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia nitrogen, and TP were determined according to the standard method [33].

The membrane containing residual insoluble was dried in a lyophilizer (XY-FD-S40, Shanghai, China) to prevent oxidation of the Fe(ii) species as much as possible and the dry solid substances present analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (XRD-6000, Shimadzu, Japan). Jade 6.0 software was used to analyze the data and determine the chemical structure of the precipitate [34].

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Doctoral Fund, ZR2016EEB09) for financial support.

-

Funding information: Grants ZR2016EEB09 from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Doctoral Fund).

-

Author contributions: Chao Wang: writing – original draft; Changwen Wang: writing – review and editing; Mei Xu: methodology; Fanke Zhang: formal analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Sun F, Liu Y. China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection adopted Draft Amendment to the Law on Prevention and Control of Water Pollution. Front Environ Sci Eng. 2016;10(6):1–2.10.1007/s11783-016-0890-6Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mayer T, Manning PG. Evaluating inputs of heavy metal contaminants and phosphorus to lake ontario from Hamilton Harbour. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1991;59(3–4):281–98.10.1007/BF00211837Search in Google Scholar

[3] Farmer JG. Methodologies for soil and sediment fractionation studies. Sci Total Environ. 2003;303(3):263–4.10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00501-6Search in Google Scholar

[4] Burpee B, Saros JE, Northington RM, Simon KS. Microbial nutrient limitation in Arctic lakes in a permafrost landscape of, southwest Greenland. Biogeosciences. 2016;13(2):365–74.10.5194/bg-13-365-2016Search in Google Scholar

[5] Smith VH, Tilman GD, Nekola JC. Eutrophication: impacts of excess nutrient inputs on freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Environ Pollut. 1999;100(1–3):196.10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00091-3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Daniel TC, Sharpley AN, Lemunyon JL. Agricultural phosphorus and eutrophication: a symposium overview. J Environ Qual. 1999;27(2):251–7.10.2134/jeq1998.00472425002700020002xSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Petzet S, Cornel P. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater. Water Sci Technol. 2013;59(6):1069–76.10.2166/wst.2009.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Stávková J, Maroušek J. Novel sorbent shows promising financial results on P recovery from sludge water. Chemosphere. 2021;276(6):130097.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130097Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Yuan Z, Pratt S, Batstone DJ. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater through microbial processes. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23(6):878–83.10.1016/j.copbio.2012.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Zhang T, Ding LL, Ren HQ, Guo ZT, Tan J. Thermodynamic modeling of ferric phosphate precipitation for phosphorus removal and recovery from wastewater. J Hazard Mater. 2010;176(1–3):444–50.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Jordaan EM, Ackerman J, Cicek N. Phosphorus removal from anaerobically digested swine wastewater through struvite precipitation. Water Sci Technol. 2010;61(12):3228–34.10.2166/wst.2010.232Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Yoshino H, Kawase Y. Kinetic modeling and simulation of zero-valent iron wastewater treatment process: simultaneous reduction of nitrate, hydrogen peroxide, and phosphate in semiconductor acidic wastewater. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2013;52(50):17829–40.10.1021/ie402797jSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang J, Abdallatif S, Chen XG, Xiao K, Sun JY, Yan XX, et al. Low-voltage electric field applied into MBR for fouling suppression: Performance and mechanisms. Chem Eng J. 2015;273:223–30.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zhou YN, Xing XH, Liu ZH, Cui LW, Yu AF, Feng Y, et al. Enhanced coagulation of ferric chloride aided by tannic acid for phosphorus removal from wastewater. Chemosphere. 2008;72(2):290–8.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.02.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Zhang J, Satti A, Chen X, Xiao K, Sun J, Yan X, et al. Low-voltage electric field applied into MBR for fouling suppression: Performance and mechanisms. Chem Eng J. 2015;273:223–30.10.1016/j.cej.2015.03.044Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wan A, Zhao B, Dong H, Wu Y, Xie Y. Study on biological filler-coupled biological process for phosphorus removal. Desalin Water Treat. 2020;203:179–87.10.5004/dwt.2020.26218Search in Google Scholar

[17] Liu S. Performance and mechanism of phosphorus removal by slag ceramsite filler. Transactions of The Institution of Chemical Engineers. Process Saf Environ Prot Part B. 2021;148(1):858–66.10.1016/j.psep.2021.02.016Search in Google Scholar

[18] Han Y, Li H, Liu M, Sang Y, Liang C, Chen J. Purification treatment of dyes wastewater with a novel micro-electrolysis reactor. Sep Purif Technol. 2016;170:241–7.10.1016/j.seppur.2016.06.058Search in Google Scholar

[19] Xu X, Cheng Y, Zhang T, Ji F, Xu X. Treatment of pharmaceutical wastewater using interior micro-electrolysis/Fenton oxidation-coagulation and biological degradation. Chemosphere. 2016;152:23–30.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.100Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Li JP, Song C, Wu W. A study on influential factors of high-phosphorus wastewater treated by electrocoagulation–ultrasound. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013;20(8):5397–404.10.1007/s11356-013-1537-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Yuan SH, Wu C, Wan JZ, Lu XH. In situ removal of copper from sediments by a galvanic cell. J Environ Manag. 2009;90(1):421–7.10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.10.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Deng SH, Li DS, Yang X, Xing W, Li JH, Zhang Q. Iron [Fe(0)]-rich substrate based on iron–carbon micro–electrolysis for phosphorus adsorption in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 2017;168:1486–93.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Hu SH, Wu YG, Yao HR, Lu C, Zhang CJ. Enhanced Fenton-like removal of nitrobenzene via internal microelectrolysis in nano zerovalent iron/activated carbon composite. Water Sci Technol. 2016;73(1):153–60.10.2166/wst.2015.467Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Ying DW, Peng J, Xu XY, Li K, Wang YL, Jia JP. Treatment of mature landfill leachate by internal micro-electrolysis integrated with coagulation: a comparative study on a novel sequencing batch reactor based on zero valent iron. J Hazard Mater. 2012;229–30:426–33.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.06.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Gutierrez O, Park D, Sharma KR, Yuan ZG. Iron salts dosage for sulfide control in sewers induces chemical phosphorus removal during wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2010;44(11):3467–75.10.1016/j.watres.2010.03.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ivanov V, Kuang SL, Stabnikov V, Guo CH. The removal of phosphorus from reject water in a municipal wastewater treatment plant using iron ore. J Chem Technol Biotechnol Biotechnol. 2009;84(1):78–82.10.1002/jctb.2009Search in Google Scholar

[27] Wu CY, Peng YZ, Gan YP. Biological nutrient removal in A∼2O process when treating low C/N ratio domestic wastewater. J Chem Ind Engineering (China). 2008;59(12):3126–31.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Chen YZ, Peng YZ, Wang JH, Zhang LC. Biological phosphorus and nitrogen removal in low C/N ratio domestic sewage treatment by a A2/O-BAF combined system. Acta Sci Circumstantiae. 2010;30(10):1957–63.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Carter R, Huhman B, Love CT, Zenyuk IV. X-ray computed tomography comparison of individual and parallel assembled commercial lithium iron phosphate batteries at end of life after high rate cycling. J Power Sources. 2018;381:46–55.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.01.087Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lu J, Nishimura SI, Yamada A. A Fe-rich sodium iron orthophosphate as cathode material for rechargeable batteries. Electrochem Commun. 2017;79:51–4.10.1016/j.elecom.2017.04.012Search in Google Scholar

[31] Wu Y, Tam NFY, Wong MH. Effects of salinity on treatment of municipal wastewater by constructed mangrove wetland microcosms. Mar Pollut Bull. 2008;57(6–12):727–34.10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.02.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Hong J, Lu F, Yin J. Effects of salinity on treatment of aquaculture wastewater by dynamic membrane bioreactor with intermittent aeration. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2012;28(11):212–7.Search in Google Scholar

[33] APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 21st edn. Washington: American Public Health Administration; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Huang WL, Cai W, Huang H, Lei ZF, Zhang ZY, Tay JH, et al. Identification of inorganic and organic species of phosphorus and its bio-availability in nitrifying aerobic granular sludge. Water Res. 2015;68:423–31.10.1016/j.watres.2014.09.054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”