Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

-

Muntathir AlBeladi

, Avni Berisha

Abstract

Zinc oxide and quaternary ammonium-type surfactants have been separately recognized for their anti-corrosive efficiencies. Their composite, not investigated so far, could provide a synergetic anti-corrosion effect. In this respect, the aim of this study is to synthesize a composite material consisting of zinc oxide and benzalkonium chloride (ZnO-BAC) in varying mass ratios (3:1, 1:1, and 1:3). The inhibitory properties of the ZnO-BAC composite against carbon steel corrosion in a 0.5 M sulfuric acid solution were assessed under ambient conditions. First, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy were used to examine the chemical structure of the prepared composite. Then, the corrosion inhibitive performance of the devised inhibitors was screened using electrochemical, hydrogen collection, and weight loss measurements. Further, the surface morphology was examined using a scanning electron microscope, both before and after immersion in the corrosion medium. The electrochemical measurements indicate that the prepared inhibitor exhibits a predominant cathodic inhibition behavior and the maximum inhibition efficiency, approximately 91.9%, was achieved for one-to-one mass ratio. Similar results were obtained from weight loss and hydrogen evolution measurements, which showed that the ZnO-BAC composite reduced the corrosion rate of carbon steel by 69.9% and 64.9%, respectively. Finally, molecular dynamics and an adsorption equilibrium model were used to elucidate the mechanism of corrosion inhibition by the ZnO-BAC composite, which exhibits a high adsorption energy on the iron surface.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Mild steel and iron are extensively involved in a myriad of industrial applications, such as pipes, storage tanks as well as construction materials [1,2,3]. However, legion of industrial processes, such as pickling, acid cleaning, acid descaling, and oil well acidification, resulted in undesirable corrosion of such materials, leading to significant economic and ecological problems [4,5]. To mitigate such corrosion processes, basically two main methods are available: surface coatings and inhibitors. Inhibitors are a class of substances, which in a small quantity in a corrosive medium has the ability to suppress, slowdown, or at least mitigate the corrosion reaction.

Historically, diverse inorganic compounds, such as chromates, tungstates, phosphates, nitrates, molybdates, and heptamolybdates, have been applied for long time as corrosion inhibitors; however, their use is, now, very restricted because of toxicity concerns and strict environmental regulations [6]. Therefore, assessment, design, and synthesis of new, effective, and environmentally benign compounds are of paramount importance in this field.

Alternatively, several metal oxide materials such TiO2, MgO, Al2O3, CuO, CeO, ZnO, etc., are recognized to be effective against corrosion processes [7]. Metal oxides are also used as fillers in epoxy coatings to enhance both their corrosion resistance and their cracking resistance, which makes the coatings more durable [8]. The eco-friendly and cost-effective green synthesis of nanoparticles, including zinc oxide (ZnO), using natural plant extracts like Fagonia cretica, has garnered significant attention in recent years, showcasing its potential for applications in various fields [9,10]. Zinc oxide, which has features such as simple synthesis methods, low cost, ecofriendly nature, high thermal conductivity, high refractive index, antimicrobial effectiveness, low toxicity, and biocompatibility, was widely used as an additive in various applications such as food, drugs, cement, plastics, paints, and batteries [11]. In this respect, low load of ZnO has been reported to exhibit better inhibition efficiency in sulfuric acid (H2SO4) medium [11]. Besides, the synergistic effects of ZnO nanoparticles in hydrochloric acid have been reported [12]. Later, zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with a natural myrrh extract exhibited a strong inhibitive effect on the corrosion of steel in 1 M HCl [13].

On the other hand, unsaturated organic compounds including electronegative atoms within their structures, namely, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur are well recognized to be the main active components of organic corrosion inhibitors [14,15,16,17]. Basically, the centers of interaction between the metal atoms on the surface and the inhibitor molecules are the free, unbound electrons of unsaturated bonds and the lone pair electrons on the electronegative heteroatoms. Such interactions favor the attachment of the inhibitor molecules to the metal surface and the creation of a protective layer that blocks and hinders the access of the aggressive acid solution to the surface. However, like inorganic anticorrosion agents, standard organic inhibitors suffer from being often expensive and hazardous to the environment [18]. In this respect, cationic surfactants that are highly soluble in polar electrolytes, thermally and chemically stable, low in toxicity, and biodegradable arise as promising green and sustainable alternatives to combat against steel corrosion [19,20].

Among them, Benzalkonium chloride (BAC), as a cationic surfactant, was chosen in this study because of its widespread use in the oil and gas industry as a biocide to prevent microbiologically induced corrosion [15,18,21,22,23]. Previously, BAC was used to inhibit the corrosion of carbon steel in 0.1 M H2SO4 [23].

This research pioneers a novel approach by combining zinc oxide and benzalkonium chloride (ZnO-BAC), prepared in different mass ratios, as a corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel, demonstrating its superior performance in a highly corrosive 0.5 M H2SO4 environment, capitalizing on the unique characteristics of both materials. The binary composite was applied as anticorrosion agent for carbon steel in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. The synergistic effects of the as-prepared corrosion inhibitors were assessed by different electrochemical techniques, notably open current circuit, polarization curves, and impedance spectroscopy as well as by weight loss and hydrogen collection experiments. Furthermore, an attempt to understand the mechanism governing the anticorrosion behavior of the devised inhibitors was undertaken by density functional theory (DFT) calculations, notably using the adsorption model.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma and the Shanghai Chemical Reagent Company (China) and were used without any further purification.

2.2 Preparation of the ZnO-BAC composite

A certain quantity of ZnO was combined with 20 mL of water to prepare the ZnO-BAC composite. This blend was then gradually added to 20 mL of ethanol solution (25, 50, and 75 wt% of BAC) containing an appropriate amount of BAC. The solution was then refluxed for 9 h and dried in an oven for 10 h.

2.3 Characterization apparatus

A spectrophotometer Alpha-P from Bruker was used to obtain Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra. The spectra covered a wavenumber range from 400 to 4,000 cm−1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis, a method that detects electrons from atoms near the surface, with minimal energy loss, was performed using a Thermo Sicientific K-Alpha with an Al Kα source that provided an energy of 1,486.6 eV.

2.4 Coupon preparation

The study employed low-carbon steel plate samples (2.5 cm × 4 cm × 0.1 cm) with the following compositions (wt%): C, 0.20; Mn, 0.02; Si, 0.05; Al, 0.01; P, 0.02; Ti, 0.04; and Cu, 0.02; balance Fe (wt%). The samples were polished using a LaboPol-21 (Struers) grinding machine with 500, 1,200, 2,000, and 4,000 grit silicon-carbide grinding papers. The samples were smoothed using 8 in MICROPAD polishing papers manufactured by PACE Technologies and a 30 μm MetaDi diamond suspension from BUEHLER. They were then put in an ultrasonic bath with acetone for 10 min, rinsed with distilled water, and air-dried.

2.5 Electrochemical measurements

A three-electrode flat cell used with a platinum mesh, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE), and a 0.785 cm2 carbon steel are used as the counter, reference, and working electrodes, respectively. High-flow nitrogen gas purged the cell of oxygen before experiments, and a slow nitrogen flow continued during measurements to stop oxygen from dissolving in the electrolyte, which was made by diluting analytical grade 90–91% H2SO4 with distilled water and adding or not adding 200 ppm of inhibitors. Five electrochemical measurements were performed at room temperature using an SP-200 potentiostat (BioLogic Company, Grenoble, France), and EC Laboratory software was used to analyze the data. The inhibitive effects of the inhibitors were evaluated using several electrochemical techniques, including open circuit measurements, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, potentiodynamic polarization, and cyclic voltammetry. Before performing electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements, an open circuit potential was recorded for 2 h. Then, a sinusoidal voltage of 10 mV was applied at an open circuit potential to obtain the measurements in the frequency range of 10−1 Hz to 105 Hz using an AC signal. The following formula was used to calculate the double-layer capacitance (Q), F·s(n−1)·cm−2 [24]:

where Y

0 is a proportional factor, ω

m

is the angular frequency at the peak of the imaginary axis impedance, and n is a deviation factor from −1 to +1, indicating a pure inductor or a pure capacitor, respectively. Linear polarization was performed on the working electrode by varying its potentials between open circuit potential (OCP) plus or minus 30 mV. A scan rate of 0.166 mV·s–1 was used for this method. The polarization resistance (R

p) of the inhibitors was measured using the Stern-Geary technique and compared with the blank sample. The working electrode potentials were changed between OCP plus 500 mV and OCP minus 250 mV at a scan rate of 0.166 mV·s–1 to perform the potentiodynamic polarization experiment. Eq. 2 was used to calculate the inhibition efficiency, represented by

The current densities without and with inhibitors,

The corrosion current density (µA·cm−2), i

corr; atomic mass of carbon steel (g·mol−1), MW; sample density (g·cm−3),

2.6 Weight loss experiment

For different durations, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12 days, the carbon steel samples were tested by immersing them in acid solutions containing 200 ppm of the inhibitors. Afterward, they were cleaned according to ASTM G1 standard under C3.5 designation [26]. The following formula shows corrosion rates, (r corr in MPY) calculated using the gravimetric method [26].

The formula for the corrosion rate uses the weight loss (mg),

Eq. 5 was used to determine the weight loss inhibition efficiency, represented by

The equation uses

2.7 Hydrogen collection experiment

The hydrogen evolution method was used to complement the results from the polarization and gravimetric experiments for the inhibitors. This method allows for real-time measurement of the hydrogen gas produced by the displacement of water molecules. For 10 days, the water level in a graduated cylinder that was upside down decreased as the coupons were soaked in a 20 mL flask of acidic solution with 200 ppm of inhibitors. The corrosion rate, represented by i

corr and measured in µA·cm−2, was calculated using Eq. 6, which involves

2.8 Computational details

For the purpose of simulating the propensity of ZnO-BAC to interact with Fe substrate, module DFT was applied. The DMol3 module in Material Studio was utilized for the optimization of the geometry and the calculation of the quantum chemical parameters. This work made use of the M06-L functional in combination with the polarization (DNP) basis set and the generalized gradient approach-corrected functional approaches [28,29,30,31]. In order to take into account the impacts of the aqueous phase in the DMol3 computations, COSMO parameters were utilized [32,33]. After being imported, the Fe cell was split along the 110 plane and then relaxed. To reduce the energy of the Fe (110) surface and increase the surface area for interaction between the constituents of ZnO-BAC, a smart minimizer approach was employed. This was achieved by enlarging the Fe (110) surface to a super cell size using the following parameters: a = b = 24.82 Å and c = 13.24 Å +40 Å vacuum layer. This additional space was necessary to accommodate the molecules used to simulate the inhibitor and the corrosion media, which included ZnO-BAC (1:3), 800 H2O molecules, 5SO4 2− ions, and 10H3O+ ions. The MD calculation was performed using the COMPASS III force field in a simulation box [34,35,36,37,38,39]. The conditions for the simulation included a time step of 1 fs and a simulation time of 800 ps. The NVT ensemble was utilized. The overall energy of the entire system (E total), the energy of the iron surface with the solution added (E surface + solution), and the energy of the inhibitor film (E inhibitor) were used to calculate the interaction energies (E interaction).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of the prepared inhibitors

3.1.1 FTIR analysis

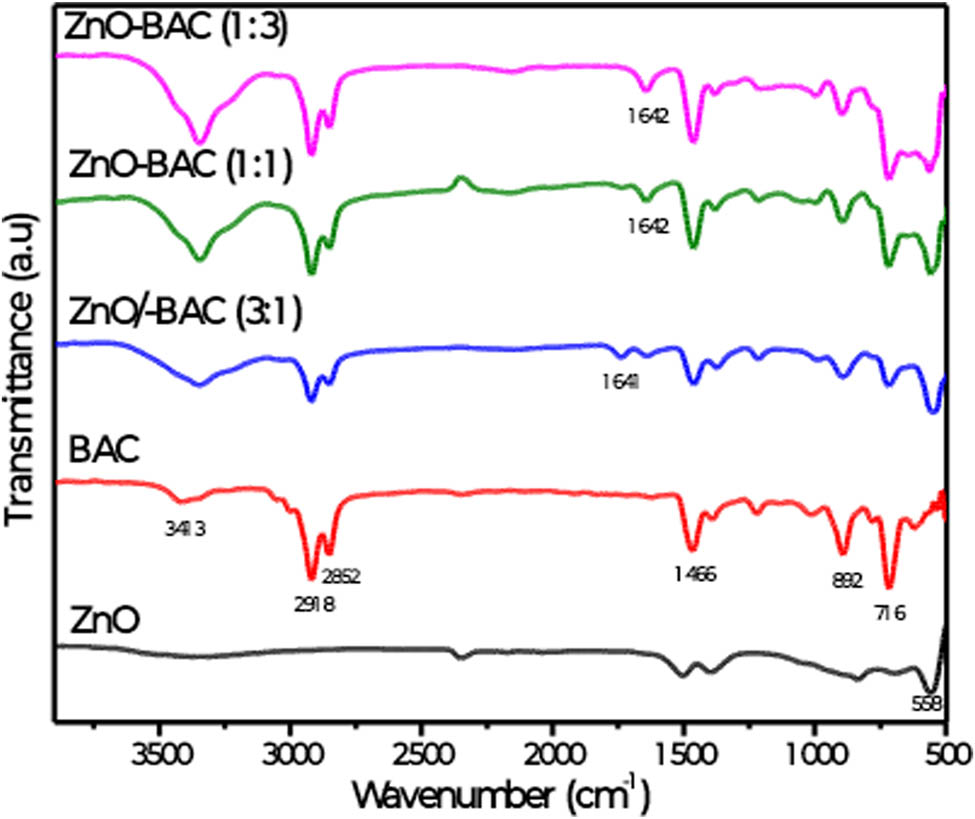

To get insights on how ZnO interacts with BAC, FTIR measurements were performed and the spectra of the different samples are shown in Figure 1. The FTIR spectrum of the bare ZnO sample displays typical pattern for such material, characterized by a large vibration band between 500 and 600 cm−1 assigned to the stretching mode of Zn–O bond [40,41]. Likewise, the FTIR spectrum of BAC overlaps with those reported in literature for this compound [42,43]. Thus, in the spectrum of BAC, the main characteristic peaks appear at 3,413 (O–H stretching vibration of adsorbed water as samples are prepared at open air), 2,918 (–CH3 bending vibration), 2,852 (C–H stretching vibration), 1,466 (C═C stretching vibration), 892 (C–N stretching vibration), and 716 (aromatic rings out-of-plane binding vibrations). Remarkably, the mixture of ZnO and BAC brings minor changes in the vibrations of BAC and the spectra relative to various BAC percentages overlap quasi-totally with that of the naked BAC except the appearance of vibrational band around 1,640 cm−1, whose intensity increase with the BAC mass percentage. Such band could be assigned to the N–H deformation band. Structurally, BAC consists of polar hydrophilic head group positively charged and non-polar hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail chain, it is likely that the hydrophilic group is oriented outside in the ZnO-BAC composite, while the positively charged ammonium group of the polar head interact with hydroxyl groups on the ZnO surface reflected by the increase in the N–H band intensity with the increase in the BAC mass percentage. Further, a large band located between 500 and 600 cm−1 is attributed to Zn–O vibration. The above observations together with a slight peak shift of the BAC vibration band positions indicate a weak interaction between ZnO and BAC; therefore, ZnO is simply entrapped into BAC via weak electrostatic interactions.

FTIR spectra of zinc oxide (ZnO) without and with different mass percentages of BAC.

3.1.2 XPS analysis

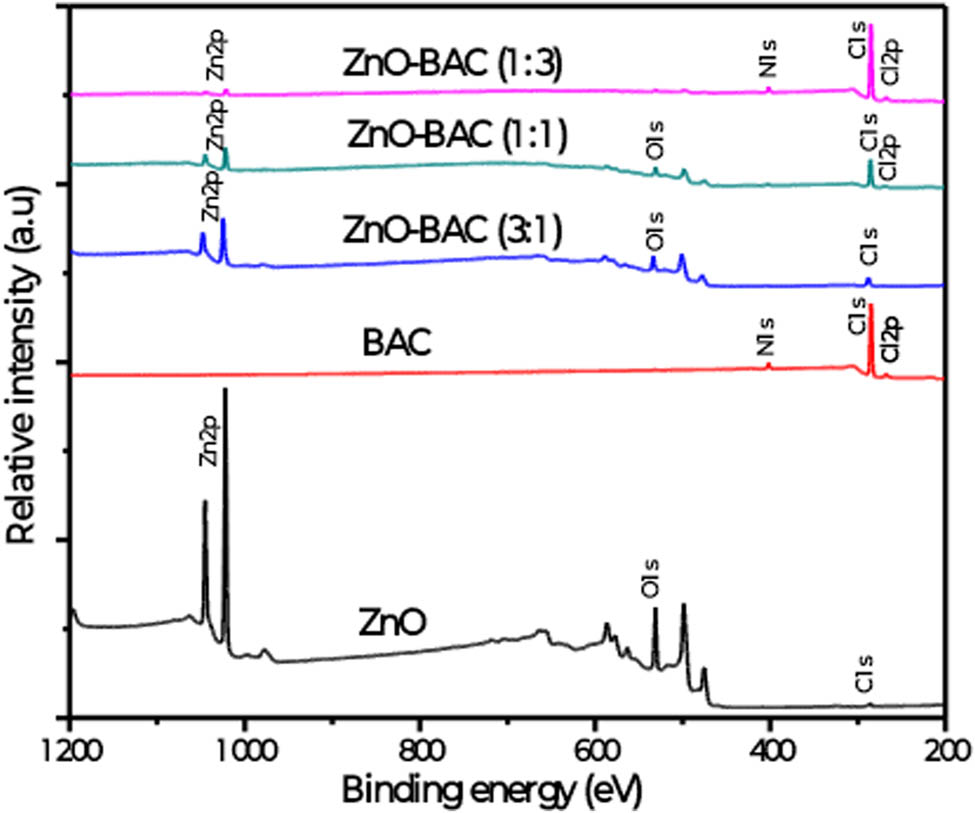

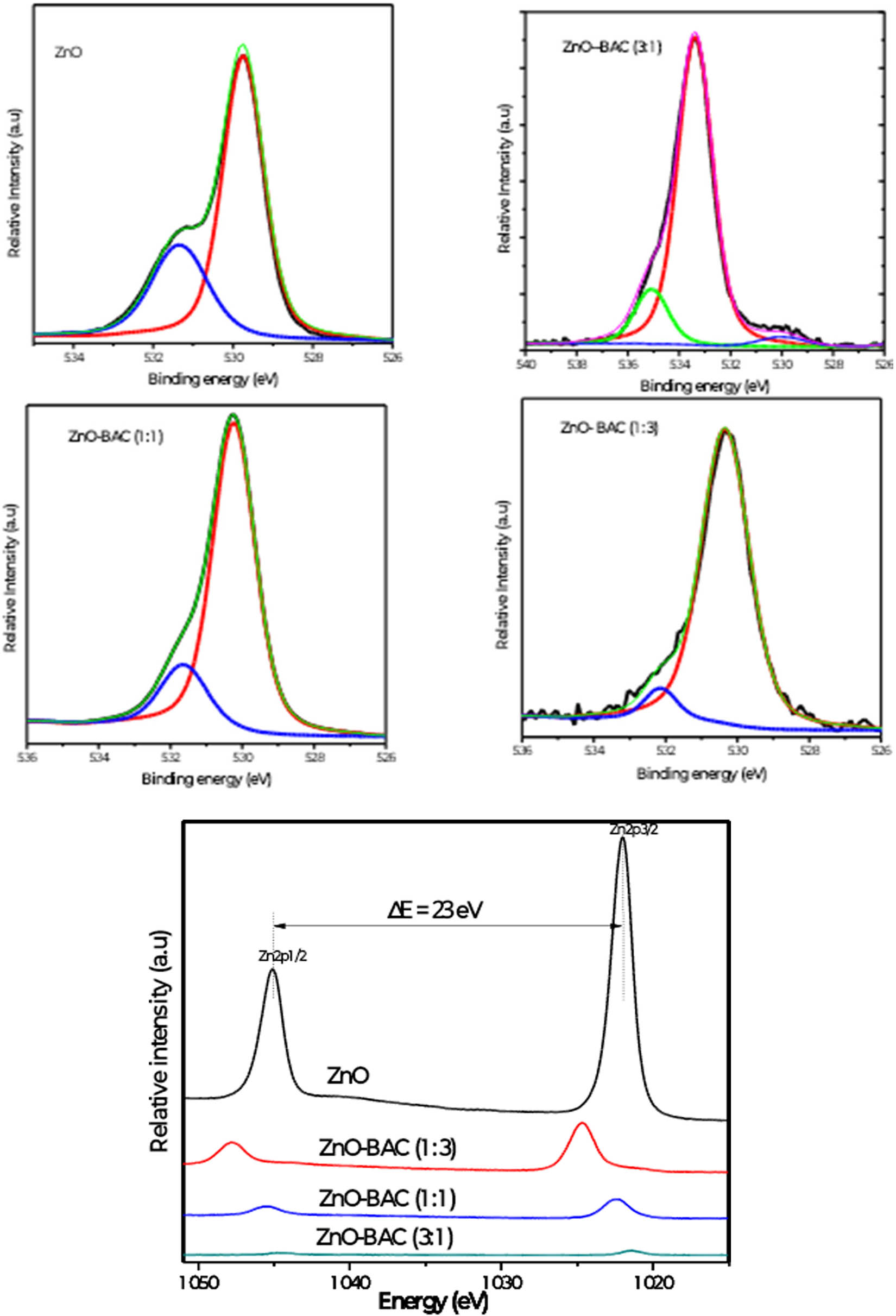

The surface chemistry of ZnO before and after BAC mixture process was explored by XPS. The binding energies are calibrated with respect to the binding energy of the adventurous carbon set at 284.8 eV [44]. Figure 2 shows the recorded survey for each sample, while Figure 3 shows the deconvoluted high resolution scans corresponding to Zn2p and O1s lines.

XPS surveys for the different inhibitors.

Deconvolution of the high-resolution XPS spectra showing the characteristic peaks O1s and Zn2p for different inhibitors.

As depicted in Figure 2, the characteristic lines of ZnO, notably, Zn2p and O1S appeared clearly in the spectrum of the bare ZnO, then vanished gradually when the BAC percentage increased. Based on this observation, it can be inferred that the ZnO structures in the composite material are predominantly located within the bulk region.

In addition, the deconvolution of the high-resolution spectra of the characteristic peaks of ZnO, notably O1s, enabled inspection of its surface chemistry evolution. The O1s peaks are clearly dissymmetric, so that they can be fitted by two or more Gaussian, reflecting the existence of various types of oxygen bonding at the ZnO surface. Specifically, the O1s of the naked ZnO is deconvoluted into peaks: a central peak centered at 530 eV assigned to the lattice oxygen and a shoulder centered at 531.3 eV assigned to oxygen deficiency or vacancy. Remarkably, in the case of ZnO-BAC (3:1), the deconvolution of O1s shows three components centered at 530, 533.4, and 535.1 eV, respectively, and could be assigned to the lattice oxygen, the adsorbed oxygen and the adventitious carbon dioxide C═O and the COOH groups adsorbed at ZnO surfaces. Finally, the O1s peaks of the ZnO-BAC (1:1) and ZnO-BAC (1:3) are identical and present two peaks: a central peak located at 530 .3 eV attributed to the lattice oxygen in ZnO and a shoulder at 532.1 eV ascribed to the adsorbed oxygen. On the other hand, the deconvolution of Zn2p peaks reveals two resolved peaks located at 1,021 and 1,024 eV for the naked ZnO and assigned to the Zn2p3/2 and Zn2p1/2 spin-orbit splitting, respectively. The positions of these peaks are slightly shifted to 1,021.6 and 1,044.5 eV for both samples ZnO-BAC (1:1) and ZnO- BAC (1:3).

In contrast, these peaks were shifted to higher energies (at 1,024.7 and 1,047.8 eV) for the ZnO-BAC (3:1) which can be associated with the drastic change in its surface chemistry with respect to the other samples.

Overall, XPS analysis indicated an obvious surface chemical change in ZnO in the composite, especially for the sample ZnO-BAC (3:1).

3.2 Evaluation of the inhibitive potential of the devised inhibitor

3.2.1 Electrochemical measurements

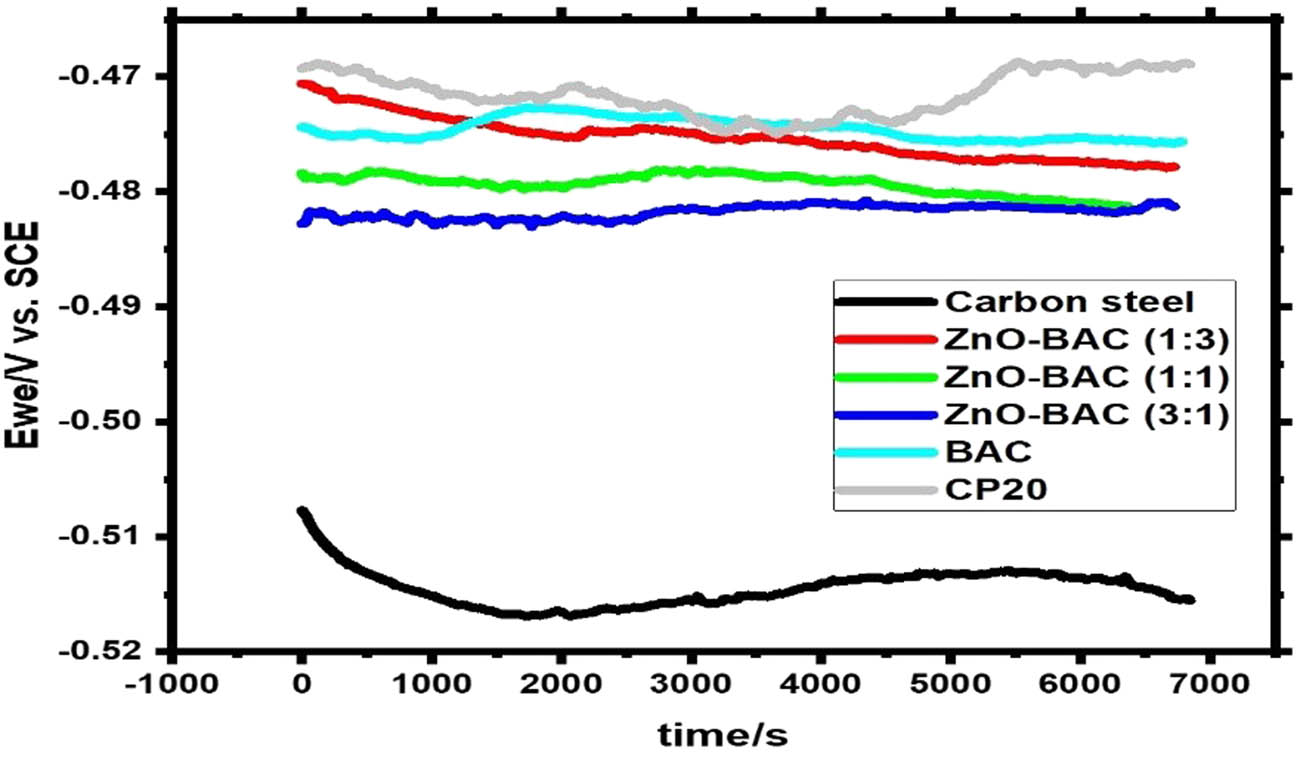

3.2.1.1 OCP analysis

Figure 4 shows the free potential (OCP) variation with time, about 2 h, for the inhibited and uninhibited carbon steel samples. The OCP remains almost constant when the steel plates are immersed in the various test solutions. The addition of inhibitors caused the corrosion potential to move to passive regions. The change in potentials was less than 85 mV, which means that the inhibitors affected both the anodic and cathodic reactions in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution [45]. Similar results were previously obtained for a binary composite TiO2-BAC [46]. This result is due to the inhibitor forming a protective layer on the carbon steel surface [47].

OCP experiment in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution.

3.2.1.2 Potentiodynamic polarization analysis

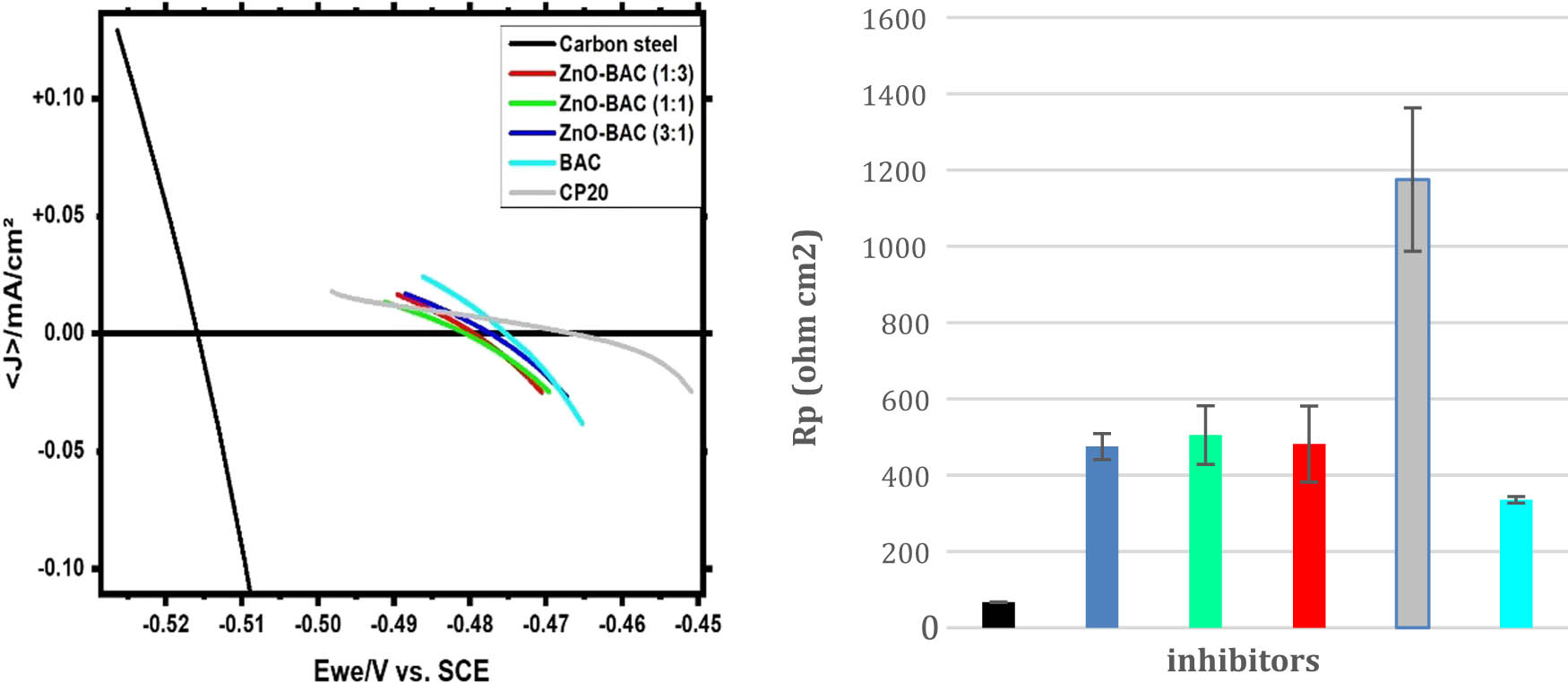

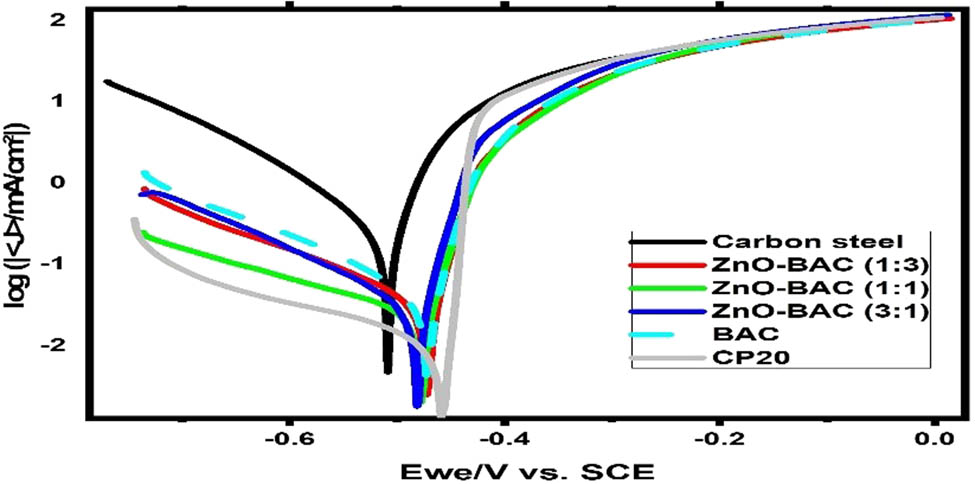

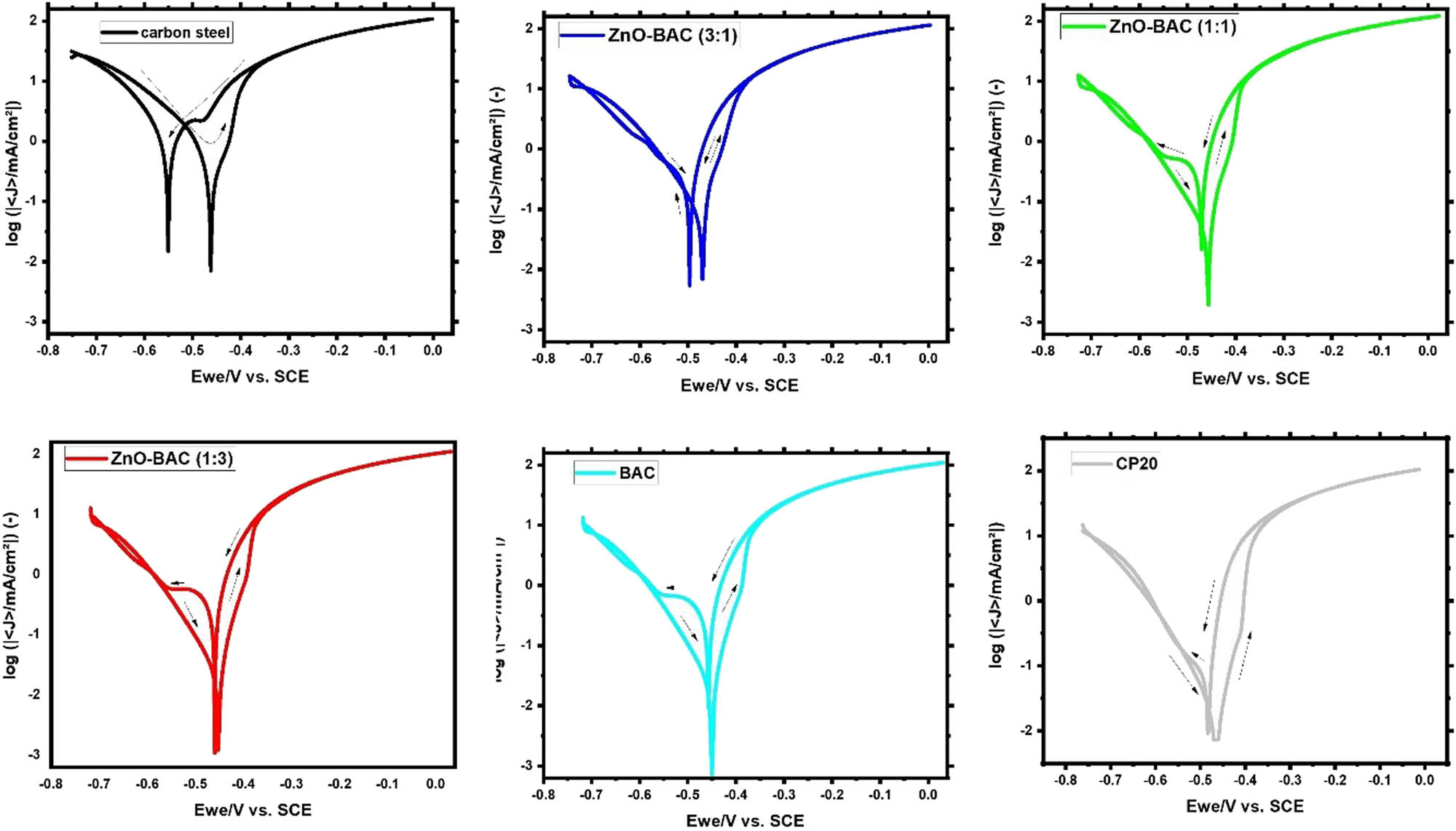

In 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, the linear polarization plots of carbon steel are shown in Figure 5a with and without each of these inhibitors: BAC, ZnO-BAC (3:1), ZnO-BAC (1:1), ZnO-BAC (1:3), and CP20. These curves are extracted from the linear polarization plots using the linear polarization method (LPR). R p value increased, five-fold, by BAC addition compared to uninhibited sample, and ZnO inclusion further improved the BAC resistance. The commercial inhibitor: CP20 behaves more linear than other inhibitors, displaying the highest R p value as shown in Figure 5b. Long polarization plots, Tafel, provide similar trend, corrosion current density is lower for CP20 than ZnO-BAC (1:1), and BAC shows the highest value among all inhibitors with inhibition efficiencies of 94.8%, 91.9%, and 84.7%, respectively (Figure 6 and Table 1). Inhibitors prevent iron from dissolving and hydrogen from forming by adsorbing on the anodic and cathodic sites on the carbon steel surface, respectively. In the anodic region, CP20 has a significant lower anodic Beta Tafel constant than all as-prepared inhibitors revealed by the decrease in the slope of its plot with respect to the other inhibitors, which support a pitting corrosion susceptibility. The corrosion cathodic current densities are clearly lower than the anodic ones for all inhibited samples. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 7, for all the inhibitors, cyclic voltammetry plots showed positive hysteresis indicating a localized corrosion. In addition, BAC, ZnO-BAC (1:1), and ZnO-BAC (1:3) outperforms CP20 with slight more positive re-passivation potentials (E rep) and smaller hysteresis size related to pitting corrosion.

Left side: Linear polarization experiment in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, ZnO: zinc oxide and BAC: benzalkonium chloride. Right side: Average polarization resistance extracted from the left-side curves.

Potentiodynamic Polarization curves in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution.

Electrochemical parameters from potentiodynamic polarization figures

| Corrosion medium | E corr (V/SCE) | β a (mV·dec−1) | −β c (mV·dec−1) | I corr (µA·cm−2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | −0.513 | 53.1 | 126.1 | 297.3 | — |

| ZnO-BAC (3:1) | −0.482 | 43.9 | 163.8 | 40.5 | 86.4 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:1) | −0.475 | 29.1 | 281.2 | 24.1 | 91.9 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:3) | −0.472 | 34.6 | 199.3 | 37.9 | 87.3 |

| BAC | −0.476 | 35.2 | 173.2 | 45.5 | 84.7 |

| CP20 | −0.486 | 24.7 | 338.1 | 15.6 | 94.8 |

Cyclic polarization in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, at a scan rate of 1 mV·s−1.

3.2.1.3 EIS analysis

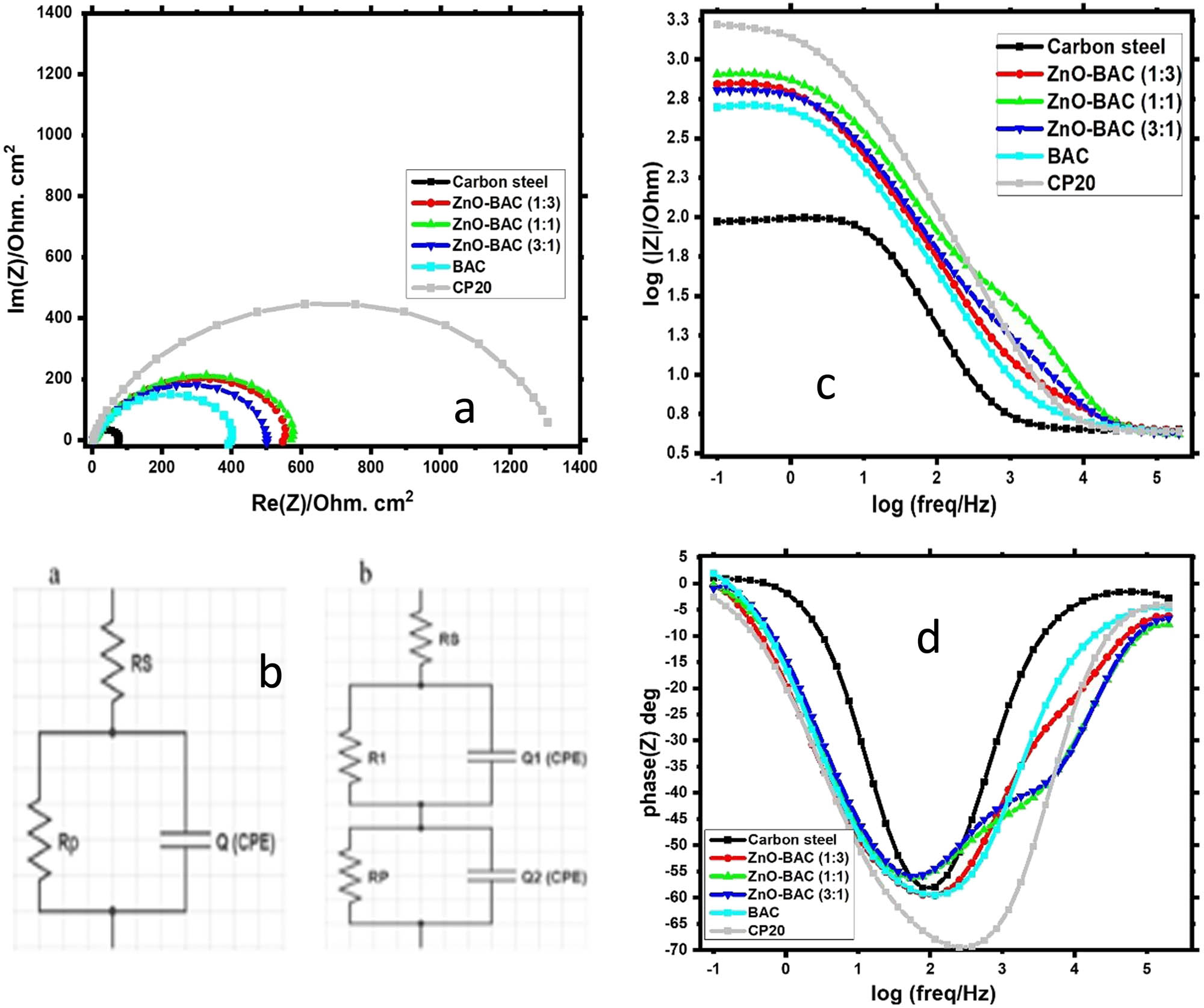

A quick and effective experimental technique widely used to evaluate the performance of corrosion inhibitors is electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Experiments were performed at corrosion potential and at room temperature. Figure 8a shows the electrochemical impedance curves of carbon steel (as a Nyquist diagram) in the 0.5 M H2SO4 by adding 200 ppm of inhibitor. Figure 8b and c show the Bode diagrams and phase angles, respectively. The curves show that the steel surface has a capacitive behavior whether or not the inhibitor is present in the electrochemical process. In both cases, with or without inhibitors, the Nyquist plot shows only one capacitive loop that indicates that a charge transfer process mainly controls the corrosion of steel in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution [36,48]. The working electrode surface has inhomogeneity and roughness, which causes the curves to be semicircle [49]. This electrochemical behavior of semi-circle is noticed in the majority of the cases of the organic molecules test as corrosion inhibitors, which create a protective layer on the surface of the steel [50]. This behavior can be attributed to the non-ideal capacitive interface between the steel and electrolyte, demonstrating the inhibitor’s effectiveness in hindering corrosion. The increase in the impedance plot diameter suggests that the inhibitory efficiency increases in the following order: BAC < ZnO-BAC (3:1) < ZnO-BAC (1:3) < ZnO-BAC (1:1) < CP20. The impedance data from the EIS experiments with and without inhibitors are summarized in Table 2.

(a) Nyquist plot carried out on the carbon steel electrode in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, (b) equivalent electrical circuits including two models I and II used for the fitting of the impedance spectra, (c) corresponding Bode plots, and (d) corresponding phase angles.

Calculated electrical elements for the proposed equivalent circuits

| Corrosion medium | R s (Ω·cm2) | R 1 (Ω·cm2) | Q 1 (µF·s(n−1)·cm−2) | n 1 | R p (Ω·cm2) | Q 2 (µF·s(n−1)·cm−2) | n 2 | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 4.5 | — | — | — | 74.2 | 182.0 | 0.91 | 0.030 |

| BAC | 4.4 | — | — | — | 417.7 | 203.7 | 0.77 | 0.050 |

| ZnO-BAC (3:1) | 4.0 | 7.8 | 71.1 | 0.79 | 507.9 | 112.5 | 0.78 | 0.027 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:1) | 4.0 | 19.9 | 10.3 | 0.92 | 822.4 | 95.4 | 0.78 | 0.016 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:3) | 4.2 | 1.5 | 41.0 | 0.86 | 577.4 | 139.1 | 0.76 | 0.028 |

| CP20 | 4.1 | — | — | — | 1,258.4 | 60.9 | 0.82 | 0.141 |

While a simplified Randels cell model is used to fit carbon steel, CP20 and BAC data, two-time constants in series are more appropriate to fit the impedance spectra of the binary ZnO-BAC inhibitors. Randels equivalent circuit consists of double-layer capacitor (CPE) and polarization resistance (R p) in parallel, and R s solution resistance in series. A second circuit consists of resistance, R 1, and constant phase element, Q 1, for fast charge transfer process of iron dissolution. A single time constant from Bode plot and one depressed capacitive semicircle from Nyquist plot indicate a single charge transfer mechanism for blank, BAC, and CP20 samples. A common process for organic inhibitors is to create a protective film on the metal surface by adsorbing inhibitor molecules [18,51]. Surface heterogeneity and frequency dispersion cause depressed semicircle-shaped Nyquist. Inhibitor effectively protects carbon steel as the increased semicircle diameter suggests. ZnO-BAC (1:1) showed the highest R p value, 822.4 (Ω·cm2), with respect to other mass ratios Table 3. CP20 had the highest R p and lowest CPE values revealed by a low phase shift angle − 70° at higher frequencies, symbolic of superior corrosion inhibition (Figure 8d). BAC inhibitors displayed higher phase angles and greater impedance over the entire frequency range compared to the blank sample. In Figure 8, two distinct slopes for ZnO inhibitors as well a discrepancy between phase angles in high and low frequency regions indicate the changed inhibition kinetic mechanism. ZnO-BAC inhibitors showed similar n values but lesser than both CP20 and the blank which can be ascribed to the attachment of the inhibitor to the metal surface and the creation of a more heterogenous protective layer.

Overview of the mean rates of corrosion in MPY units measured by three techniques, namely, electrochemical, weight loss, and hydrogen evolution

| Inhibitor | Corrosion inhibiting effectiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Weight loss | Hydrogen collection | |

| ZnO-BAC (3:1) | 79.4 | 59.9 | 50.2 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:1) | 89.4 | 69.9 | 64.9 |

| ZnO-BAC (1:3) | 86.6 | 75.3 | 62.1 |

| BAC | 84.5 | 70.8 | 55.1 |

| CP20 | 92.3 | 93.5 | 78.9 |

The Bode diagram reflects the behavior of oxidation–reduction reactions, inhibition reactions, and migration of material across the electrochemical interface which depends on the physicochemical characteristics of the interface of the electrode and the corrosive medium. The Bode diagram offers a more detailed representation of the electrochemical system’s frequency-dependent behavior that is only implied in the Nyquist diagrams. The convenience of these Bode diagrams is the identification of the basic elements of the equivalent circuits that describe the electrolyte/electrode interface. In general, bode diagrams show three frequency ranges, namely, high, medium, and low frequencies [52]. When the phase angle gets close to 0°, the Bode diagram has a level region for frequencies higher than 1,000 Hz. The spectrum has a linear response of about −1 as log(f) decreases in the mid-frequency range (1,000–10 Hz). This indicates a capacitive behavior resulting from the conductive film’s dielectric properties on the surface of the steel. Several chemical processes, such as electron charge transfer, mass transfer, and relaxation, occur at the boundary between the film and the electrolyte or inside the film’s pores when the frequency is low (f < 10 Hz). In all cases, the Bode diagrams, in the high frequency range from 1,000 Hz, the logarithmic values of log|Z| tend toward the same value independent of frequency. This is observed in uninhibited and inhibited solutions. When the inhibitor is absent, the plateau region begins to appear at frequencies above 1,000 Hz, but when the inhibitor is added, it only does so at frequencies above 10,000 Hz. A new phase angle loop also appears when the inhibitors have a certain amount of ZnO. A protective film that prevents the carbon steel from corroding may form this new loop, and its small time constant leads to a change in phase at high frequencies.

3.2.2 Hydrogen collection and weight loss experiments

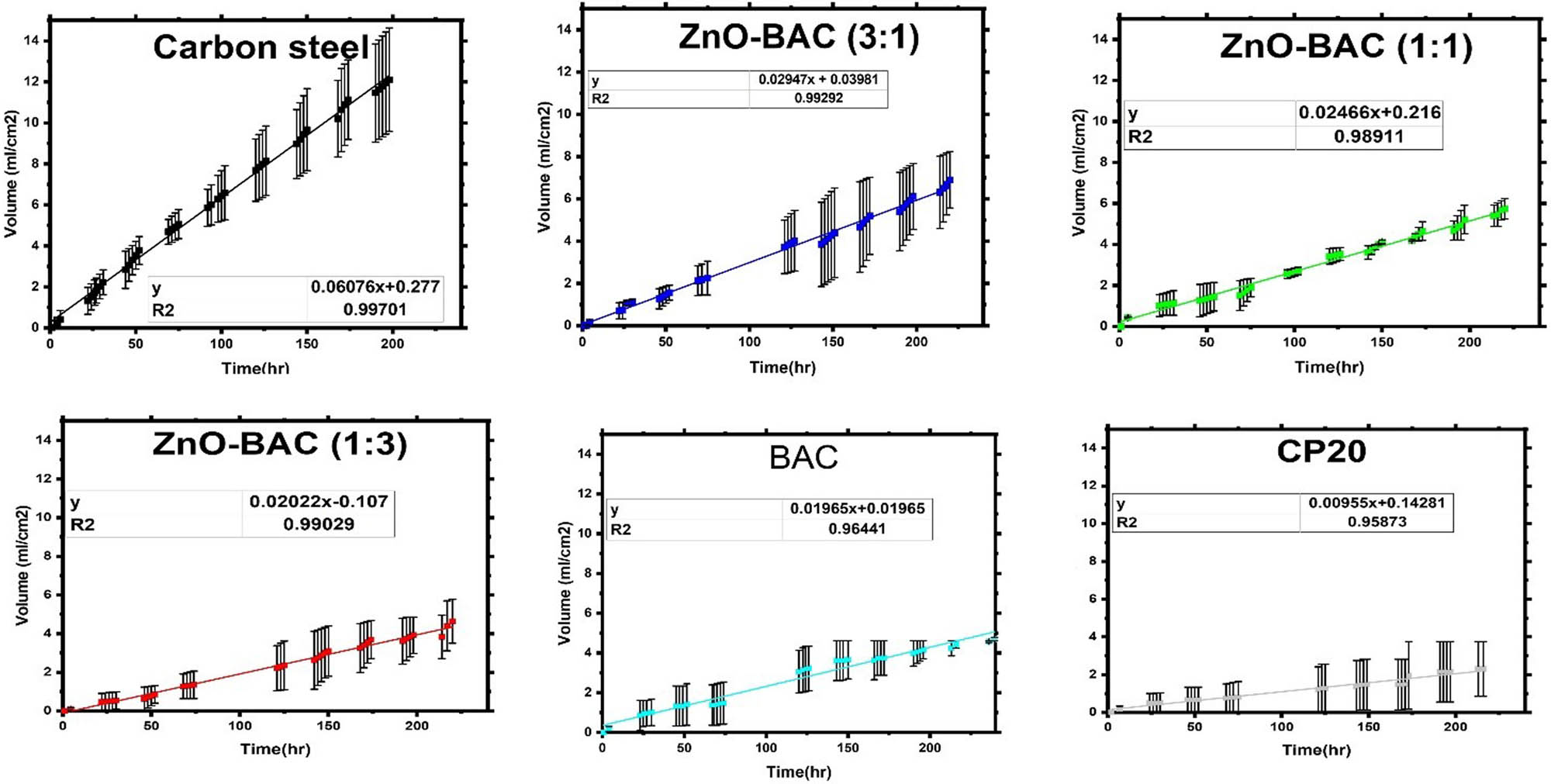

Hydrogen evolution efficiencies followed similar trend as the electrochemical method, that is ZnO-BAC (1:1) inhibitor had the major protection efficiency after CP20. Figure 9 shows the real time hydrogen collection processed with and without inhibitors over a period of 10 days. Uniform linear curves are obtained with a steady corrosion rate over time, as indicated by the high R-squared values and absence of a plateau at the end of the data. The plots indicate that the slope of the curves is significantly lowered after inhibitors addition.

The mean volume of displaced water per sample area vs the incubation time in hours measured from two samples except for the blank which had three samples.

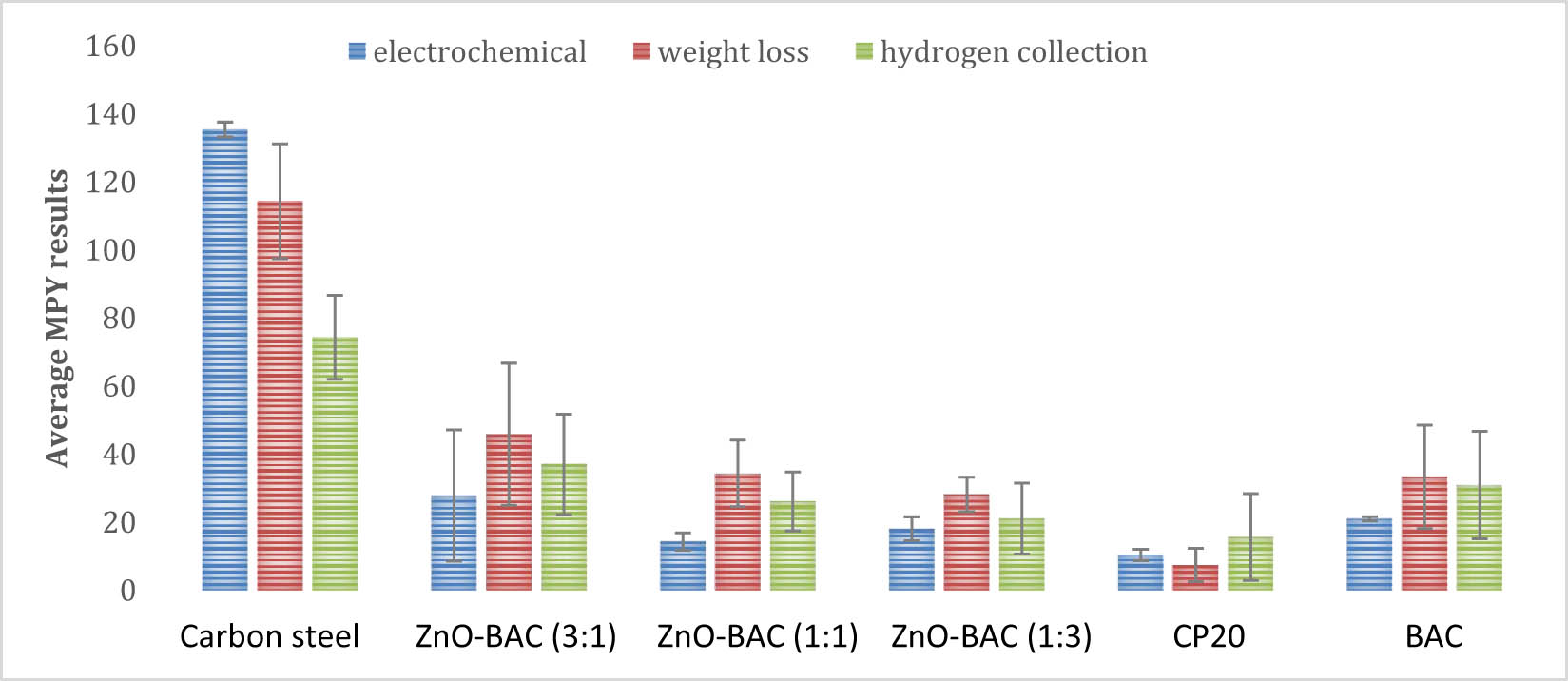

Further, weight loss experiments were conducted for each sample with varied incubation days: 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12 in 0.5 M H2SO4 media. Figure 10 presents the average MPY corrosion rate for three experiments: mass loss, gasometric, and electrochemical techniques. Mass loss method is colored orange in Figure 10. Inhibitors addition reduced corrosion significantly compared to blank sample. The most efficient inhibitor was ZnO-BAC (1:3) followed by BAC and ZnO-BAC (1:1) of around 70%. CP20, the commercial inhibitor, showed the best efficacy of 94% (Table 3). The electrochemical efficiencies presented in Table 3 highlight that BAC demonstrates corrosion inhibiting effectiveness comparable to what was observed in Guo et al.’s study [23]. Moreover, when a lower quantity of ZnO is combined with BAC, it enhances corrosion inhibition, as previously observed in Loto et al.’s research, emphasizing the synergistic effect between these materials [11].

An overview of the mean corrosion rates in MPY units with the standard deviation calculated from the three methods, namely, electrochemical, weight loss, and hydrogen evolution.

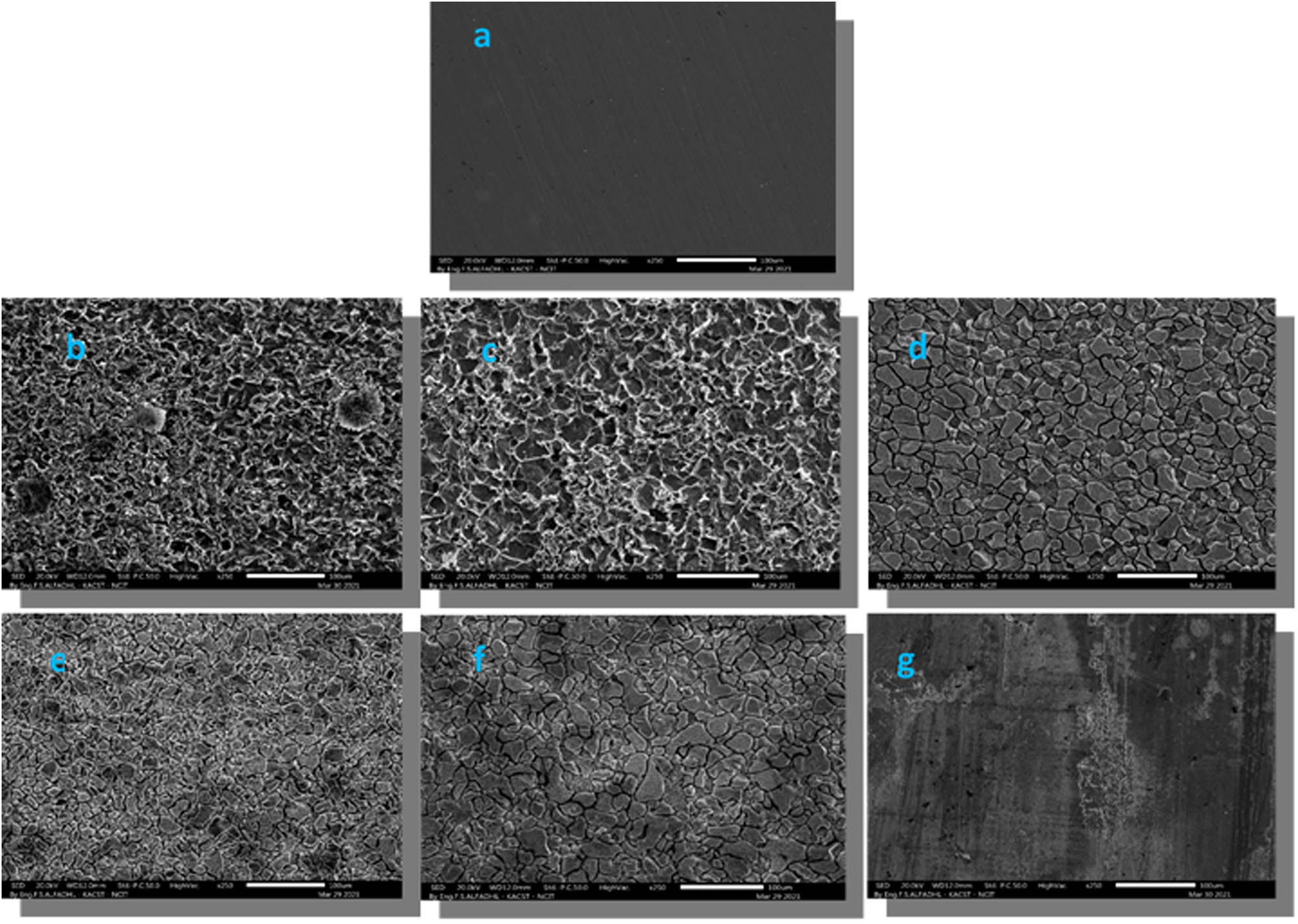

3.2.3 Surface roughness and morphology

To gain further insight into the performance of inhibitors, the surface characteristics of carbon steel samples were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). This analysis was conducted after immersing the samples in 0.5 M H2SO4 for a period of 10 days, both with and without the presence of inhibitors, at room temperature. The SEM image in Figure 11(a) depicts the polished steel prior to its exposure to the corrosive acidic medium. The carbon steel sample appeared smooth with few abrasion scratches. On the other hand, Figure 11(b) displays a distinct deterioration of the carbon steel surface following its submersion in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. Remarkably, in the presence of BAC, Figure 11(c) demonstrates that the steel surface experiences less damage compared to when H2SO4 is present. The SEM images in Figure 11(c)–(e) show the steel surface after being immersed in 0.5 M H2SO4 with the ZnO-BAC composite. The steel surface remains intact and is not corroded. The steel’s surface coverage is enhanced by reducing the direct interaction between the surface and the corrosive substance. The presence of the CP20 inhibitor creates a protective film on the steel surface, enhancing its resistance to corrosion. As shown in Figure 11(g), the steel remains unaffected by H2SO4.

SEM images taken after 10 days of incubation in an acidic solution, except for (a) which shows polished carbon steel before corrosion, (b) blank, (c) ZnO-BAC (3:1), (d) ZnO-BAC (1:1), (e) ZnO-BAC (1:3), (f) BAC, and (g) CP20.

3.2.4 Plausible mechanism of inhibition: DFT simulation

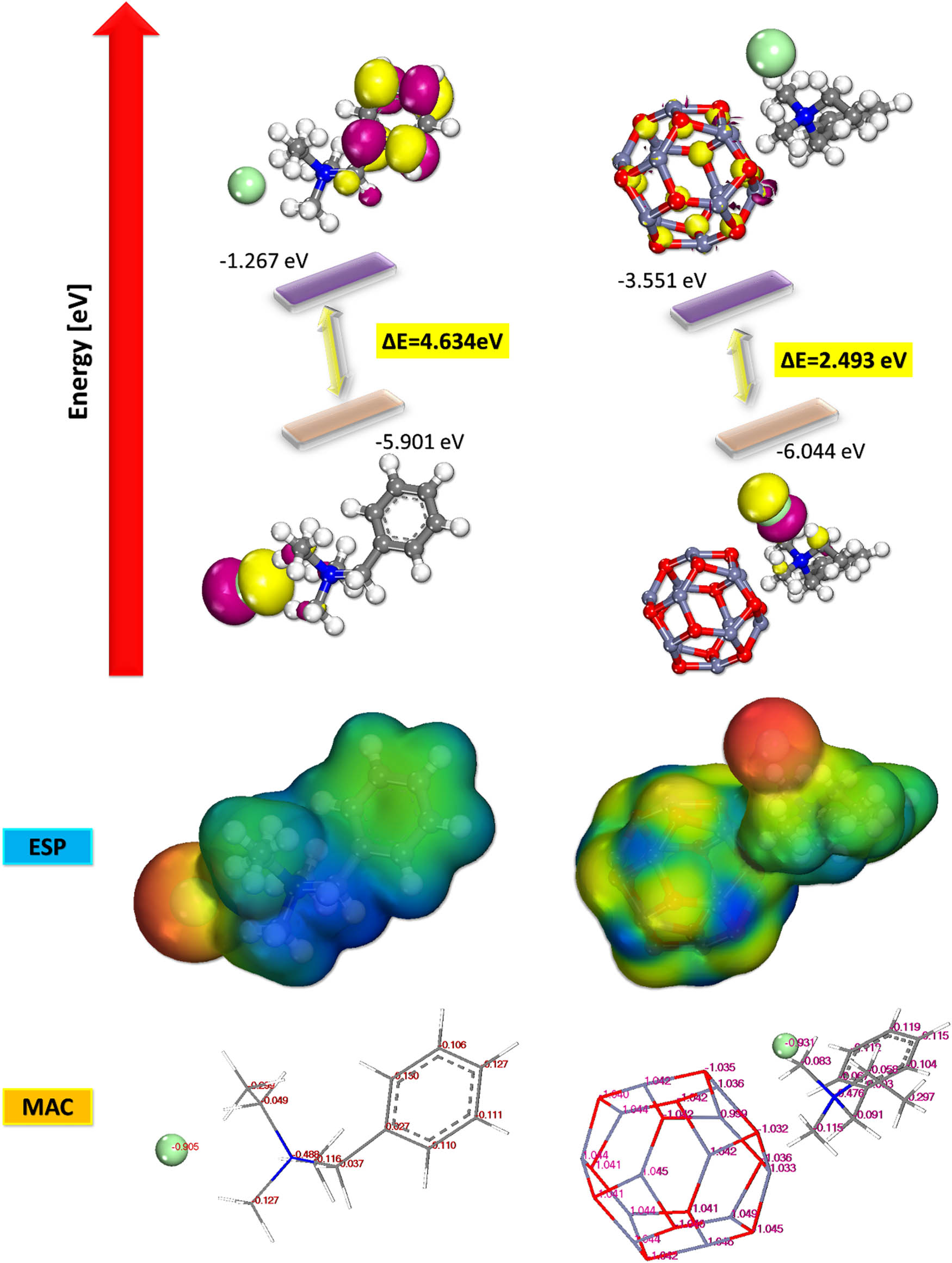

The use of theoretical research employing density quantum chemical computations has become prevalent in quantifying a range of electronic and structural factors that exhibit strong correlation with the corrosion inhibitory activity of diverse organic compounds [50,53,54]. Herein, a theoretical method has been used to explore how ZnO-BAC interact with the iron (Fe) surface in order to complement the above experimental method and estimate the inhibitory mechanism. The correlation between the ability of an organic compound to function as a corrosion inhibitor and specific electronic characteristics that dictate its strength of adsorption as an adsorption-based inhibitor on a surface is significant. This tendency can be traced back to the fact that certain electronic descriptors play a role in the adsorption of inhibitors to act as corrosion barrier layers [55–58]. BAC and ZnO-BAC each has its own optimal electronic structures depicted in Figure 12.

HOMO, LUMO, MAC, and ESP for BAC and ZnO-BAC.

This Figure also shows the density of electron distribution, the region of highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO), and the region of lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) for each material. The main objective of this computation is not to compare the inhibition efficiency of multiple compounds, but rather to provide the electronic properties of the material that has been investigated and to gain an understanding of the compound’s site of interaction with the metal surface [50,55,59]. This is because only one organic molecule has been studied. The tabular representation of the estimated electronic parameters are shown in Table 4. The LUMO, which is represented by the yellow region, is often linked to areas in the structure that lack electrons. As a result, it is highly receptive to receiving electrons from a site that has an abundance of electrons [36,56,57,60]. The HOMO regions, represented by the blue region, indicate the specific areas within the BAC and ZnO-BAC structure that are most favorable for electron release toward electron deficient regions. A significantly small negative value of LUMO energies (E LUMO) indicates a high level of electron acceptance sensitivity, while a large negative value of HOMO energies (E HOMO) indicates a strong ability to donate electrons. This potential feature demonstrates significant tendencies to interact with the vacant-d orbital of the iron lattice by employing the antibonding orbital. This can lead to the formation of feedback bonds. As a consequence, the energy gap, denoted by the symbol (ΔE), which was determined from the difference between the values of (E HOMO) and (E LUMO), remained at low levels. This is characteristic of highly polarized molecules or highly reactive chemicals. This demonstrates that the examined inhibitors can efficiently transfer electrons to the vacant d-orbital of iron and can also receive electrons from corroding iron surface and/or in the d-orbital of iron using antibonding orbitals [61–63]. Once again, a small energy gap (ΔE) suggests amplified tendency of achieving higher levels of inhibition efficiency. This is because a minimal excitation energy is required to remove an electron from its occupied orbital [35,36]. The electron affinity and ionization potential can be approximated using the EHOMO and ELUMO, while Mulliken electronegativity (χ) and absolute hardness, the fraction of transferred electrons (ΔN), are described previously [34,39,64]. When ΔN > 0, one may anticipate a significant amount of electron transfer from the metal surface to the inhibitor molecule, and vice versa [33,36,65]. Altogether, computational results demonstrate that ZnO-BAC possesses the necessary properties to act as an effective inhibitor.

Calculated theoretical chemical parameters for the studied inhibitor system

| Descriptor | BAC | ZnO/BAC |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO | −5.9010 | −6.0440 |

| LUMO | −1.2670 | −3.5510 |

| ∆E(HOMO–LUMO) | 4.634 | 2.493 |

| Ionization energy (I) | 5.9010 | 6.0440 |

| Electron affinity (A) | 1.2670 | 3.5510 |

| Electronegativity (X) | 3.5840 | 4.7975 |

| Global hardness (η) | 2.3170 | 1.2465 |

| Chemical potential (π) | −3.5840 | −4.7975 |

| Global softness (σ) | 0.4316 | 0.8022 |

| Global electrophilicity (ω) | 2.7719 | 9.2323 |

| Electrodonating (ω−) power | 4.8535 | 11.7868 |

| Electroaccepting (ω+) power | 1.2695 | 6.9893 |

| Net electrophilicity (∆ω+−) | 1.0635 | 6.9045 |

| Fraction of transferred electrons (∆N) | 0.2667 | 0.0090 |

| Energy from Inhb to metals (∆N) | 0.1648 | 0.0001 |

| ∆E back-donation | −0.5793 | −0.3116 |

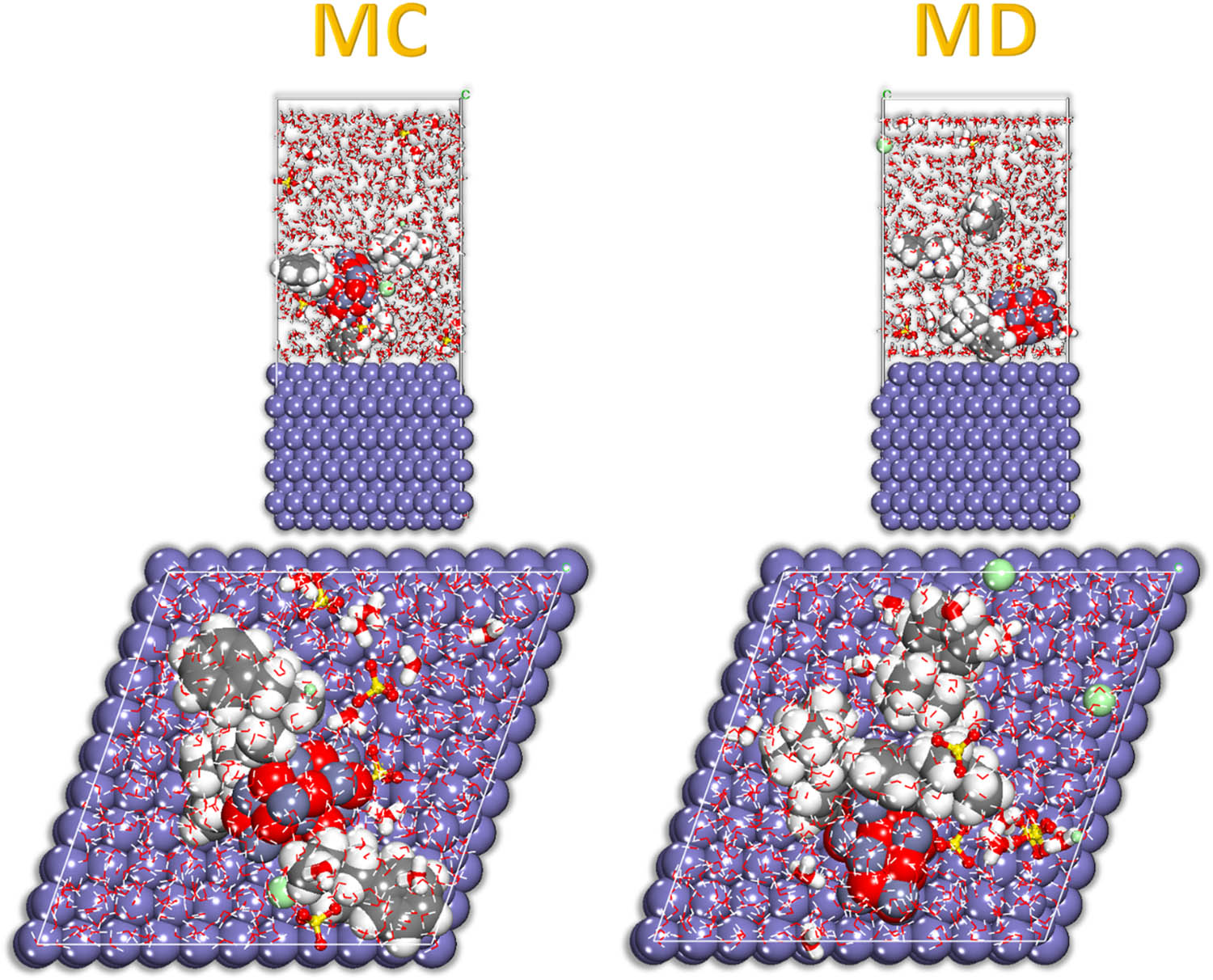

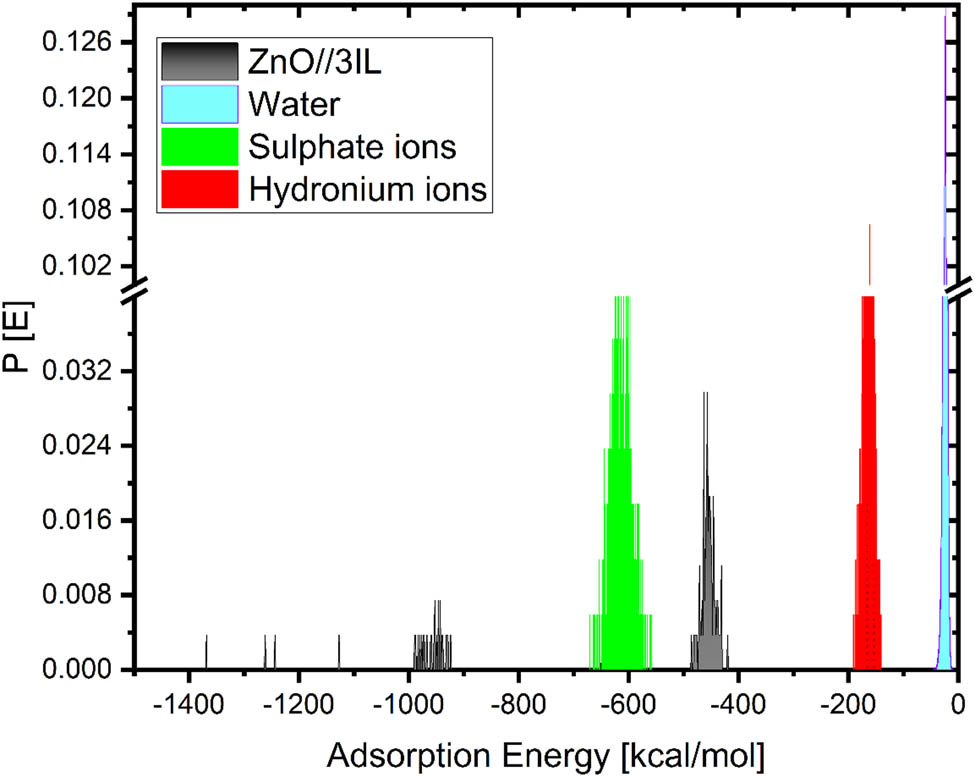

The obtained results are consistent with previous experimental findings [34,39,56,59]. A reputable and efficient method to identify the atoms responsible for inhibiting the metal adsorption process is to use the Mulliken atomic charges (MAC). There are multiple factors that contribute to the increased likelihood of interaction between specific atoms on the Fe (1 1 0) surface and various inhibitor compounds. Many ideas have been put up in an effort to explain this event [66–68]. The MAC of the inhibitor, a parameter of significant relevance to our study, is visually depicted in Figure 13. The inhibitors contain nitrogen and multiple carbon atoms with highly negative charges, which suggests that these areas have the highest electron density and are therefore the most effective in adhering to metal surfaces. The inhibitors’ molecular electrostatic potential is shown in Figure 13, with the red area representing a range of values for MC and MD. It is simple to determine the system’s adsorption energies using the Fe (110) surface as a main basis and a grade of simplicity equal to that of the calculation. The system’s adsorption energies may now be calculated thanks to this. Using the following equation on a specific molecule will yield the Eads value, or adsorption energy [69–74]:

where

In the simulated corrosive medium, the lowest adsorption configurations for inhibitors adsorption on the Fe (110) substrate, with A representing MC and B representing MD.

Following the successful completion of the MC calculations, a thorough examination of the inhibitor’s adsorption configuration was conducted in order to elucidate the findings. This was undertaken to make certain that the findings were valid [56,57]. The equilibrium of the MC simulation can be evaluated by comparing the energy values at the steady state with the energy values at the beginning of the simulation. The simulation had progressed to the stage where the system’s running state demanded minimal energy to maintain [50,53]. Figure 14 depicts the actual configuration of the adsorbent inhibitors, which is an accurate representation of the actual organization of the adsorbent inhibitors. This illustration is based on a simulated Fe-110 aircraft. The inhibitor decorates Fe (110) surface during the MD. As seen in Figure 14, we hypothesize that the adsorption pattern on the Fe (110) plane is induced by the inhibitor molecule’s adsorption centers attaching to the surface atoms of the plane [66,72,75–77]. The evidence gathered lends legitimacy to this notion. The inclination of molecules to bring their rich atom structural constituents closer to the surface allows them to adsorb, and this capacity endows these molecules their capacity to act as adsorbents [78–80].

Derived from MC calculations, the distribution of the adsorption energies of the inhibitors utilized in the simulated corrosive media.

Adsorption of the inhibitors to the metal’s surface will result in the formation of massive Eads, which will be visible on the surface of the metal. Due to its extremely high adsorption energies, the inhibitor exhibits a robust adsorption interaction with the metal [57,61–63,81,82]. This interaction forms a protective layer on the surface of the metal, preventing corrosion and maintaining its original condition [50,55,58].

4 Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated the synergistic corrosion inhibitory effects of a binary ZnO-BAC composite, prepared in different mass ratios, on carbon steel in a 0.5 M H2SO4 medium. Our electrochemical measurements demonstrated predominant cathodic inhibitory characteristics for all assessed inhibitors, and ZnO-BAC (1:1) was the most effective inhibitor among the tested ratios, with an inhibition efficiency of 89.4%. The presence of corrosion inhibitors was found to create a protective layer, reducing the extent of corrosion damage, as supported by SEM images. Gravimetric and hydrogen evolution experiments revealed that ZnO-BAC (1:3) and ZnO-BAC (1:1) exhibited the highest inhibition efficiency among the inhibitors at 75.3% and 64.9%, respectively. Theoretical investigations emphasized the role of electron acceptance and molecular polarity in the inhibitor’s adsorption onto the metal surface.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) and Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for supporting this study by providing laboratory facilities.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Muntathir AlBeladi: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, data curation, investigation, visualization, and formal analysis; Mohammed H. Geesi: conceptualization, resources, writing – original draft, formal analysis, and visualization; Yassine Riadi: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, data curation, formal analysis, and visualization; Mustapha Alahiane: writing – original draft and data curation; Oussama Ouerghi: writing – original draft and data curation; Avni Berisha: writing – original draft and formal analysis; Arianit Reka: writing – original draft and formal analysis; Abdellah Kaiba: writing – original draft and data curation; Talal A. Aljohani: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, formal analysis, resources, supervision, validation, and project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Panossian Z, Almeida NL, Sousa RM, Pimenta G, de Marques LB. Corrosion of carbon steel pipes and tanks by concentrated sulfuric acid: A review. Corros Sci. 2012;58:1–11. 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.01.025.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Roberge PR. Handbook of corrosion engineering. 3rd edn. McGraw Hill Professional; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Popoola L, Grema A, Latinwo G, Gutti B, Balogun A. Corrosion problems during oil and gas production and its mitigation. Int J Ind Chem. 2013;4(1):35. 10.1186/2228-5547-4-35.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ali SKA, Saeed MT, Rahman SU. The isoxazolidines: A new class of corrosion inhibitors of mild steel in acidic medium. Corros Sci. 2003;45(2):253–66. 10.1016/s0010-938x(02)00099-9.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ahanotu CC, Onyeachu IB, Solomon MM, Chikwe IS, Chikwe OB, Eziukwu CA. Pterocarpus santalinoides leaves extract as a sustainable and potent inhibitor for low carbon steel in a simulated pickling medium. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2020;15:100196. 10.1016/j.scp.2019.100196.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ait Albrimi Y, Ait Addi A, Douch J, Souto RM, Hamdani M. Inhibition of the pitting corrosion of 304 stainless steel in 0.5 M hydrochloric acid solution by heptamolybdate ions. Corros Sci. 2015;90:522–8. 10.1016/j.corsci.2014.10.023.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Verma C, Quraishi MA, Ebenso EE, Hussain CM. Recent advancements in corrosion inhibitor systems through carbon allotropes: Past, present, and future. Nano Sel. 2021;2(12):2237–55. 10.1002/nano.202100039.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kumari S, Saini A, Dhayal V. Metal oxide based epoxy coatings for corrosion protection of steel. Mater Today Proc. 2021;43:3105–9. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.587.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Hussain R, Zafar A, Hasan M, Tariq T, Saif MS, Waqas M, et al. Casting zinc oxide nanoparticles using Fagonia blend microbial arrest. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;195(1):264–82. 10.1007/s12010-022-04152-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Hasan M, Sajjad M, Zafar A, Hussain R, Anjum SI, Zia M, et al. Blueprinting morpho-anatomical episodes via green silver nanoparticles foliation. Green Process Synth. 2022;11(1):697–708. 10.1515/gps-2022-0050.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Loto CA, Joseph OO, Loto RT. Inhibition effect of zinc oxide on the electrochemical corrosion of mild steel reinforced concrete in 0.2M H2SO4. J Mater Env Sci. 2016;7:915–25.Search in Google Scholar

[12] AL-Mosawi BT, Sabri MM, Ahmed MA. Synergistic effect of ZnO nanoparticles with organic compound as corrosion inhibition. Int J Low-Carbon Technol. 2020;16(2):429–35. 10.1093/ijlct/ctaa076.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Al-Dahiri RH, Turkustani AM, Salam MA. The application of zinc oxide nanoparticles as an eco-friendly inhibitor for steel in acidic solution. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2020;15(1):442–57. 10.20964/2020.01.01.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Obot IB, Meroufel A, Onyeachu IB, Alenazi A, Sorour AA. Corrosion inhibitors for acid cleaning of desalination heat exchangers: Progress, challenges and future perspectives. J Mol Liq. 2019;296:111760. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111760.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Assem R, Fouda AS. Evaluation of cationic surfactant benzalkonium chloride as inhibitor of corrosion of steel in presence of hydrochloric acid solution. Madrige J Mol Biol. 2019;1:14–22.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jadhav AJ, Holkar CR, Pinjari DV. Anticorrosive performance of super-hydrophobic imidazole encapsulated hollow zinc phosphate nanoparticles on mild steel. Prog Org Coat. 2018;114:33–9. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.09.017.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lebrini M, Lagrenée M, Vezin H, Gengembre L, Bentiss F. Electrochemical and quantum chemical studies of new thiadiazole derivatives adsorption on mild steel in normal hydrochloric acid medium. Corros Sci. 2005;47(2):485–505. 10.1016/j.corsci.2004.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Pal A, Das C. A novel use of solid waste extract from tea factory as corrosion inhibitor in acidic media on Boiler Quality Steel. Ind Crop Prod. 2020;151:112468. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112468.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liu Y, Zhang H, Liu Y, Li J, Li W. Inhibitive effect of quaternary ammonium-type surfactants on the self-corrosion of the anode in alkaline aluminium-air battery. J Power Sources. 2019;434:226723. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.226723.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wang J, Zhang T, Zhang X, Asif M, Jiang L, Dong S, et al. Inhibition effects of benzalkonium chloride on Chlorella vulgaris induced corrosion of carbon steel. J Mater Sci Technol. 2020;43:14–20. 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.01.012.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Nowak-Lange M, Niedziałkowska K, Lisowska K. Cosmetic Preservatives: Hazardous micropollutants in need of greater attention? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):14495. 10.3390/ijms232214495.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Liu H, Gu T, Lv Y, Asif M, Xiong F, Zhang G, et al. Corrosion inhibition and anti-bacterial efficacy of benzalkonium chloride in artificial CO2-saturated oilfield produced water. Corros Sci. 2017;117:24–34. 10.1016/j.corsci.2017.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Guo L, Zhu S, Zhang S. Experimental and theoretical studies of benzalkonium chloride as an inhibitor for carbon steel corrosion in sulfuric acid. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;24:174–80. 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.09.026.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Verma C, Obot IB, Bahadur I, Sherif E-SM, Ebenso EE. Choline based ionic liquids as sustainable corrosion inhibitors on mild steel surface in acidic medium: Gravimetric, electrochemical, surface morphology, DFT and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;457:134–49. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.06.035.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ahmad Z. Corrosion kinetics. Principles of corrosion engineering and corrosion control. United Kingdom: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2006. p. 57–119. 10.1016/b978-075065924-6/50004-0.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Practice for preparing, cleaning, and evaluating corrosion test specimens. 2012. 10.1520/g0001-90r99e01.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Cui L-Y, Gao S-D, Li P-P, Zeng R-C, Zhang F, Li S-Q, et al. Corrosion resistance of a self-healing micro-arc oxidation/polymethyltrimethoxysilane composite coating on magnesium alloy AZ31. Corros Sci. 2017;118:84–95. 10.1016/j.corsci.2017.01.025.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ben Hadj Ayed M, Osmani T, Issaoui N, Berisha A, Oujia B, Ghalla H. Structures and relative stabilities of Na + Nen (n = 1–16) clusters via pairwise and DFT calculations. Theor Chem Acc. 2019;138(7):84. 10.1007/s00214-019-2476-4.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Peverati R, Truhlar DG. Performance of the M11 and M11-L density functionals for calculations of electronic excitation energies by adiabatic time-dependent density functional theory. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14(32):11363. 10.1039/c2cp41295k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Molhi A, Hsissou R, Damej M, Berisha A, Bamaarouf M, Seydou M, et al. Performance of two epoxy compounds against corrosion of C38 steel in 1 M HCL: Electrochemical, thermodynamic and theoretical assessment. Int J Corros Scale Inhib. 2021;10(2):812–37. 10.17675/2305-6894-2021-10-2-21.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Nairat N, Hamed O, Berisha A, Jodeh S, Algarra M, Azzaoui K, et al. Cellulose polymers with β-amino ester pendant group: Design, synthesis, molecular docking and application in adsorption of toxic metals from wastewater. BMC Chem. 2022;16(1):43. 10.1186/s13065-022-00837-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Halili J, Berisha A. An experimental and theoretical analysis of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of cu(II) and pb(II) ions in the form of dithizone bidentate complexes. Turk J Chem. 2022;46(3):721–9. 10.55730/1300-0527.3362.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Jafari H, Ameri E, Soltanolkottabi F, Berisha A, Seydou M. Experimental and theoretical investigations of new Schiff base compound adsorption on aluminium in 1 M HCL. J Electrochem Sci Eng. 2022. 10.5599/jese.1405.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jafari H, Ameri E, Rezaeivala M, Berisha A. 4,4’-(((2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diyl)bis(azanediyl)bis(methylene) bis(2-methoxyphenol) as new reduced form of Schiff base for protecting API 5L grade B in 1 M HCL. Arab J Sci Eng. 2022;48(6):7359–72. 10.1007/s13369-022-07281-8.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Jafari H, Ameri E, Rezaeivala M, Berisha A. Experimental and theoretical studies on protecting steel against 0.5 M H2SO4 corrosion by new schiff base. J Indian Chem Soc. 2022;99(9):100665. 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100665.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Alahiane M, Oukhrib R, Ait Albrimi Y, Abou Oualid H, Idouhli R, Nahlé A, et al. Corrosion inhibition of SS 316L by organic compounds: Experimental, molecular dynamics, and conceptualization of molecules–surface bonding in H2SO4 solution. Appl Surf Sci. 2023;612:155755. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155755.Search in Google Scholar

[37] El Gaayda J, Ezzahra Titchou F, Oukhrib R, Karmal I, Abou Oualid H, Berisha A, et al. Removal of cationic dye from coloured water by adsorption onto hematite-humic acid composite: Experimental and theoretical studies. Sep Purif Technol. 2022;288:120607. 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120607.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Ajebli S, Kaichouh G, Khachani M, Babas H, El Karbane M, Warad I, et al. The adsorption of tenofovir in aqueous solution on activated carbon produced from maize cobs: Insights from experimental, molecular dynamics simulation, and DFT calculations. Chem Phys Lett. 2022;801:139676. 10.1016/j.cplett.2022.139676.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ganjoo R, Sharma S, Thakur A, Assad H, Kumar Sharma P, Dagdag O, et al. Experimental and theoretical study of Sodium Cocoyl Glycinate as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in hydrochloric acid medium. J Mol Liq. 2022;364:119988. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119988.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Sudha D, Kumar ER, Shanjitha S, Munshi AM, Al-Hazmi GAA, El-Metwaly NM, et al. Structural, optical, morphological and electrochemical properties of ZnO and graphene oxide blended ZnO nanocomposites. Ceram Int. 2023;49(5):7284–8. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.10.192.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Long DA. Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies. tables and charts George Socrates John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, Chichester, third edition, 2001. J Raman Spectrosc. 2004;35(10):905–5. 10.1002/jrs.1238.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Liu K, Lin X, Chen L, Huang L, Cao S, Wang H. Preparation of microfibrillated cellulose/chitosan–benzalkonium chloride biocomposite for enhancing antibacterium and strength of sodium alginate films. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(26):6562–7. 10.1021/jf4010065.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Yue X, Zhang R, Li H, Su M, Jin X, Qin D. Loading and sustained release of benzyl ammonium chloride (BAC) in nano-clays. Materials. 2019;12(22):3780. 10.3390/ma12223780.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Chastain J, King Jr RC. Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Perkin-Elmer Corp. 1992;40:221.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Nkuna AA, Akpan ED, Obot IB, Verma C, Ebenso EE, Murulana LC. Impact of selected ionic liquids on corrosion protection of mild steel in acidic medium: Experimental and computational studies. J Mol Liq. 2020;314:113609. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113609.Search in Google Scholar

[46] AlBeladi MI, Riadi Y, Geesi MH, Ouerghi O, Kaiba A, Alamri AH, et al. Benzalkonium chloride/titanium dioxide as an effective corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in a sulfuric acid solution. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022;26(3):101481. 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101481.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Chauhan DS, Quraishi MA, Sorour AA, Saha SK, Banerjee P. Triazole-modified chitosan: A biomacromolecule as a new environmentally benign corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in a hydrochloric acid solution. RSC Adv. 2019;9(26):14990–5003. 10.1039/c9ra00986h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Cherrak K, Belghiti ME, Berrissoul A, El Massaoudi M, El Faydy M, Taleb M, et al. Pyrazole carbohydrazide as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCL medium: Experimental and theoretical investigations. Surf Interfaces. 2020;20:100578. 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100578.Search in Google Scholar

[49] El Faydy M, Benhiba F, Timoudan N, Lakhrissi B, Warad I, Saoiabi S, et al. Experimental and theoretical examinations of two quinolin-8-ol-piperazine derivatives as organic corrosion inhibitors for C35E steel in hydrochloric acid. J Mol Liq. 2022;354:118900. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118900.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Ould Abdelwedoud B, Damej M, Tassaoui K, Berisha A, Tachallait H, Bougrin K, et al. Inhibition effect of N-propargyl saccharin as corrosion inhibitor of C38 Steel in 1 M HCL, experimental and theoretical study. J Mol Liq. 2022;354:118784. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118784.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Pal A, Das C. New eco-friendly anti-corrosion inhibitor of purple rice bran extract for boiler quality steel: Experimental and theoretical investigations. J Mol Struct. 2022;1251:131988. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131988.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Saady A, Rais Z, Benhiba F, Salim R, Ismaily Alaoui K, Arrousse N, et al. Chemical, electrochemical, quantum, and surface analysis evaluation on the inhibition performance of novel imidazo[4,5-b] pyridine derivatives against mild steel corrosion. Corros Sci. 2021;189:109621. 10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109621.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Rahimi A, Farhadian A, Berisha A, Shaabani A, Varfolomeev MA, Mehmeti V, et al. Novel sucrose derivative as a thermally stable inhibitor for mild steel corrosion in 15% HCL medium: An experimental and computational study. Chem Eng J. 2022;446:136938. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.136938.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Mehmeti V, Halili J, Berisha A. Which is better for Lindane pesticide adsorption, graphene or graphene oxide? An experimental and DFT study. J Mol Liq. 2022;347:118345. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118345.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Daoudi W, El Aatiaoui A, Falil N, Azzouzi M, Berisha A, Olasunkanmi LO, et al. Essential oil of dysphania ambrosioides as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCL solution. J Mol Liq. 2022;363:119839. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119839.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Rbaa M, Galai M, Ouakki M, Hsissou R, Berisha A, Kaya S, et al. Synthesis of new halogenated compounds based on 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives for the inhibition of acid corrosion: Theoretical and experimental investigations. Mater Today Commun. 2022;33:104654. 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.104654.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Iravani D, Esmaeili N, Berisha A, Akbarinezhad E, Aliabadi MH. The quaternary ammonium salts as corrosion inhibitors for X65 carbon steel under sour environment in NACE 1D182 solution: Experimental and computational studies. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. 2023;656:130544. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130544.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Jafari H, Ameri E, Rezaeivala M, Berisha A, Halili J. Anti-corrosion behavior of two N2O4 Schiff-base ligands: Experimental and theoretical studies. J Phys Chem Solids. 2022;164:110645. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.110645.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Haldhar R, Kim S-C, Berisha A, Mehmeti V, Guo L. Corrosion inhibition abilities of phytochemicals: A combined computational studies. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2022;37(5):842–57. 10.1080/01694243.2022.2047379.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Abbout S, Hsissou R, Chebabe D, Erramli H, Safi Z, Wazzan N, et al. Investigation of two corrosion inhibitors in acidic medium using weight loss, electrochemical study, surface analysis, and computational calculation. J Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2022;8(3):86. 10.1007/s40735-022-00684-y.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Tang C, Farhadian A, Berisha A, Deyab MA, Chen J, Iravani D, et al. Novel biosurfactants for effective inhibition of gas hydrate agglomeration and corrosion in offshore oil and gas pipelines. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;11(1):353–67. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c05716.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Haldhar R, Jayprakash Raorane C, Mishra VK, Periyasamy T, Berisha A, Kim S-C. Development of different chain lengths ionic liquids as green corrosion inhibitors for oil and gas industries: Experimental and theoretical investigations. J Mol Liq. 2023;372:121168. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.121168.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Iroha NB, Anadebe VC, Maduelosi NJ, Nnanna LA, Isaiah LC, Dagdag O, et al. Linagliptin drug molecule as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M HCL solution: Electrochemical, SEM/XPS, DFT and MC/MD simulation approach. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. 2023;660:130885. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130885.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Dagdag O, Haldhar R, Kim S-C, Safi Zaki S, Wazzan N, Mkadmh AM, et al. Synthesis, physicochemical properties, theoretical and electrochemical studies of Tetraglycidyl methylenedianiline. J Mol Struct. 2022;1265:133508. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133508.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Tassaoui K, Damej M, Molhi A, Berisha A, Errili M, Ksama S, et al. Contribution to the corrosion inhibition of Cu–30Ni copper–nickel alloy by 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole-5-thiol (ATT) in 3% NaCl solution. Experimental and theoretical study (DFT, MC and MD). Int J Corros Scale Inhib. 2022;11(1):221–44. 10.17675/2305-6894-2022-11-1-12.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Jessima SJH, Berisha A, Srikandan SS, Subhashini S. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of corrosion inhibition efficiency of sodium lauryl sulfate modified chitosan for mild steel in the acid pickling process. J Mol Liq. 2020;320:114382. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114382.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Mehmeti VV, Berisha AR. Corrosion study of mild steel in aqueous sulfuric acid solution using 4-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol and 2-mercaptonicotinic acid – an experimental and theoretical study. Front Chem. 2017;5:61. 10.3389/fchem.2017.00061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Hsissou R, Abbout S, Seghiri R, Rehioui M, Berisha A, Erramli H, et al. Evaluation of corrosion inhibition performance of phosphorus polymer for carbon steel in [1 M] HCl: Computational studies (DFT, MC and MD simulations). J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(3):2691–703. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Dagdag O, Hsissou R, El Harfi A, Berisha A, Safi Z, Verma C, et al. Fabrication of polymer based epoxy resin as effective anti-corrosive coating for steel: Computational modeling reinforced experimental studies. Surf Interfaces. 2020;18:100454. 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100454.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Guo L, Zhang ST, Li WP, Hu G, Li X. Experimental and computational studies of two antibacterial drugs as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acid media. Mater Corros. 2013;65(9):935–42. 10.1002/maco.201307346.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Hsissou R, Benzidia B, Rehioui M, Berradi M, Berisha A, Assouag M, et al. Anticorrosive property of hexafunctional epoxy polymer HGTMDAE for E24 carbon steel corrosion in 1.0 M HCL: Gravimetric, electrochemical, surface morphology and molecular dynamic simulations. Polym Bull. 2019;77(7):3577–601. 10.1007/s00289-019-02934-5.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Dagdag O, Hsissou R, Berisha A, Erramli H, Hamed O, Jodeh S, et al. Polymeric-based epoxy cured with a polyaminoamide as an anticorrosive coating for aluminum 2024-T3 surface: Experimental studies supported by computational modeling. J Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2019;5(3):58. 10.1007/s40735-019-0251-7.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Hsissou R, Dagdag O, Abbout S, Benhiba F, Berradi M, El Bouchti M, et al. Novel derivative epoxy resin TGETET as a corrosion inhibition of E24 carbon steel in 1.0 M HCl solution. experimental and computational (DFT and MD simulations) methods. J Mol Liq. 2019;284:182–92. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.03.180.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Abbout S, Zouarhi M, Chebabe D, Damej M, Berisha A, Hajjaji N. Galactomannan as a new bio-sourced corrosion inhibitor for iron in acidic media. Heliyon. 2020;6(3):e03574. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03574.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Rbaa M, Dohare P, Berisha A, Dagdag O, Lakhrissi L, Galai M, et al. New epoxy sugar based glucose derivatives as eco friendly corrosion inhibitors for the carbon steel in 1.0 M HCL: Experimental and theoretical investigations. J Alloy Compd. 2020;833:154949. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154949.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Dagdag O, Hsissou R, El Harfi A, Safi Z, Berisha A, Verma C, et al. Epoxy resins and their zinc composites as novel anti-corrosive materials for copper in 3% sodium chloride solution: Experimental and computational studies. J Mol Liq. 2020;315:113757. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113757.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Berisha A, Podvorica F, Mehmeti V, Syla F, Vataj D. Theoretical and experimental studies of the corrosion behavior of some thiazole derivatives toward mild steel in sulfuric acid media. Maced J Chem Chem Eng. 2015;34(2):287. 10.20450/mjcce.2015.576.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Alahiane M, Oukhrib R, Berisha A, Albrimi YA, Akbour RA, Oualid HA, et al. Electrochemical, thermodynamic and molecular dynamics studies of some benzoic acid derivatives on the corrosion inhibition of 316 stainless steel in HCL solutions. J Mol Liq. 2021;328:115413. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115413.Search in Google Scholar

[79] El Faydy M, About H, Warad I, Kerroum Y, Berisha A, Podvorica F, et al. Insight into the corrosion inhibition of new bis-quinolin-8-ols derivatives as highly efficient inhibitors for C35E steel in 0.5 M H2SO4. J Mol Liq. 2021;342:117333. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117333.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Molhi A, Hsissou R, Damej M, Berisha A, Thaçi V, Belafhaili A, et al. Contribution to the corrosion inhibition of C38 steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid medium by a new epoxy resin PGEPPP. Int J Corros Scale Inhib. 2021;10(1):399–418. 10.17675/2305-6894-2021-10-1-23.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Daoudi W, Azzouzi M, Dagdag O, El Boutaybi A, Berisha A, Ebenso EE, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and corrosion inhibition activity of new imidazo[1.2-a]pyridine chalcones. Mater Sci Eng B. 2023;290:116287. 10.1016/j.mseb.2023.116287.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Omidvar M, Cheng L, Farhadian A, Berisha A, Rahimi A, Ning F, et al. Development of highly efficient dual-purpose gas hydrate and corrosion inhibitors for flow assurance application: An experimental and computational study. Energy Fuels. 2022;37(2):1006–21. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c03454.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties