A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

-

Amr Fouda

, Khalid Sulaiman Alshallash

Abstract

In the current study, among 36 isolates, the bacterial strain M7 was selected as the highest cellulase producer and underwent traditional and molecular identification as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7. The productivity of the cellulase enzyme was optimized using the one-factor-at-a-time method. The optimization analysis showed that the best pH value for cellulase production was 7, in the presence of 1% bacterial inoculum size, 5 g·L−1 of carboxymethyl cellulose, 5 g·L−1 of peptone as nitrogen source, and incubation period of 24 h at a temperature of 35°C. The highest cellulase activity (64.98 U·mL−1) was obtained after optimizing conditions using BOX-Behnken Design. The maximum cellulase yield (75.53%) was obtained after precipitation by 60% ammonium sulfate, followed by purification by dialysis bag and Sephadex G-100 column chromatography. The purified cellulase enzyme was characterized by 6.38-fold enrichment, with specific activity (60.54 U·mg−1), and molecular weight of approximately 439.0 Da. The constituent of purified cellulase was 18 amino acids with high concentrations of 200 and 160 mg·L−1 for glycine and arginine, respectively. The purified cellulase enzyme was more stable and active at pH 8 and an incubation temperature of 50°C. The metal ions CaCl2, NaCl, and ZnO enhanced the activity of purified cellulase enzyme. Finally, the B. amyloliquefaciens M7-cellulase exhibits high bio-polishing activity of cotton fabrics with low weight loss (4.3%) which was attained at a maximum concentration (1%, v/v) for 90 min.

1 Introduction

Microbial enzymes are defined as those produced by different microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, and yeasts. These enzymes are characterized as safe, eco-friendly, cost-effective, and highly stable compared to plant enzymes [1]. Different types of microbial enzymes such as proteases, amylases, xylanases, laccases, lipases, pectinases, and cellulases are extracellularly or intracellularly produced and incorporated into varied application especially those that have unique characteristics such as extreme conditions [2,3]. Among microorganisms, different bacterial strains have the efficacy to produce a wide range of enzymes. Bacillus species have found versatile applications across diverse fields, including agriculture, food and beverages, textiles, detergents, and more. These activities are due to their efficacy in producing varied extracellular proteins, amino acids, and enzymes that have been released from the cells and can be detected floating in the surrounding medium [4]. Bacillus species are frequently used in varied biotechnology and industry due to their various benefits, including their classification as harmless organisms. In addition, they are often referred to as microbial factories because of the large number of active substances, such as enzymes and antibiotics, which have been involved in different applications in various industries [5]. The significance of Bacillus species isolated from extreme environments like hot springs is heightened by their ability to produce active compounds that can withstand various stresses [6]. Thermophile bacteria are a group of bacteria that can survive in high-temperature environments, ranging from 45°C to 80°C. Also, thermophilic bacteria not only have the ability to be tolerate extreme environmental temperatures but they are also able to survive and reproduce at these temperatures [7]. These enzymes can be used in various industrial applications such as textiles, dying, agriculture, paper industries, bioethanol, pharmaceuticals, detergent, beverages, food industry, dairy, juice production, brewing, feed industry, leather industry, and waste treatment [8,9,10].

Cellulose is the main component of lignocellulosic biomass which is released from forestry and agricultural industries. This lignocellulosic biomass is hydrolyzed through the combination of three enzymes, namely, endoglucanases, cellobiohydrolases, and β-glucosidase [11]. Although a high amount of lignocellulosic plant biomass is being incorporated into different applications worldwide, many of them are unused due to the excessive cost of the bioconversion process, ultimately leading to the accumulation of these materials in the biosphere and causing pollution [10]. The disadvantage of chemical and physical methods used for the pretreatment of lignocellulose materials is the release of secondary contaminants due to the use of toxic chemicals such as bases or acids. Therefore, microbial enzymes are considered an alternative method used to increase the breakdown of lignocellulosic materials [12]. Recently, cellulase enzymes have attracted more attention due to their industrial importance. Cellulase is used for the saccharification of cellulose, which is the main component of lignocellulosic plant materials, resulting in the release of monosaccharides such as glucose which can be converted after that to biofuel such as bioethanol [13]. When compared to mesophilic cellulase enzymes, thermostable cellulase speeds up reactions, has a longer half-life, provides less risk of contaminants, and increases the feedstock solubility [14].

Cotton, known for its natural comfort and breathability, is one of the most widely used natural fibers in the textile industry. However, despite its numerous advantages, cotton fabrics often exhibit certain drawbacks, such as surface fuzziness, pilling, and reduced smoothness, which can compromise the overall quality of cotton. To overcome these issues and enhance the characteristics of cotton textiles, the textile industry has turned to innovative processes known as “bio-polishing.” Bio-polishing is a textile finishing technique that involves the use of enzymes to modify the surface of cotton fabrics that are carried out before, during, or after dyeing. This process aims to remove protruding fibers and irregularities from the fabric’s surface, resulting in improved smoothness, enhanced sheen, and reduced pilling [15]. Traditional mechanical finishing methods, while effective to some extent, are fraught with their own set of challenges. These conventional techniques often involve harsh chemical treatments, which can have detrimental effects on both the environment and the longevity of textiles. Furthermore, they consume substantial energy and water resources, contributing to the textile industry’s environmental footprint [16]. However, enzymatic bio-polishing offers a greener and more long-lasting option. Bacterial thermotolerant cellulase enzymes have shown remarkable effectiveness in enhancing the characteristics of cotton fabrics. These enzymes improve the fabric’s appearance by specifically breaking down cellulose fibers on the surface, resulting in a smoother, glossier finish without damaging the fabric [17]. Enzymatic bio-polishing has many benefits. It helps conserve water and energy while lowering pilling and softening and brightening fabrics. In addition to reducing the negative effects of textile production on the environment, bio-polishing also makes it possible to use less harmful chemical treatments and mechanical processes [15].

The aim of the current study is to investigate the efficacy of different bacterial strains isolated from water hot springs to produce cellulase enzymes. The most potent producer strain was identified using conventional and molecular methods. The optimization of cellulase production was achieved using one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) and BOX–Behnken Design (BBD) method. Moreover, the molecular weight, amino acid composition, and effect of some metals on the stability and activity of cellulase were investigated. Finally, the efficacy of synthesized cellulase enzyme in the bio-polishing of cotton fabrics was assessed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Ammonium sulfate, sodium potassium tartrate, sodium hydroxide, 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid, and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) powder, ethanol 95%, and o-phosphoric acid were purchased from EL-Noor company for chemicals, Al-Qasr Al-Aini, Cairo, Egypt). Lougle’s iodine solution, Nutrient agar (ready prepared), Sephadex G-100, Dialysis bag, and Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Cairo, Egypt).

2.2 Samples collection and bacterial isolation

Soil and water samples used for bacterial isolation were collected from Ain-Helwan spring, Helwan, Cairo, Egypt (29°51′N, 31°19′E) in sterilized Falcon tubes. The temperature of water samples was measured upon collection (39–45°C), and the pH was measured (6.23–7.14). The soil and water samples were transferred to the laboratory directly for bacterial isolation. One gram of each soil sample was dispersed in 10 mL of sterile distilled water, followed by transferring 1 mL of soil suspension or collected water samples to 9 mL dH2O and repeating this step to perform serial dilution (10–1–10–5). After that, 100 µL from a dilution of 10–4 was spread on the surface of nutrient agar plates (Ready-prepared, Fluka, Sigma Aldrich) and incubated at 45°C for 24 h. At the end of the incubation period, the bacterial colonies appeared which were picked up using a sterilized needle and re-inoculated onto a new nutrient agar plate for checking the purity. The purified bacterial isolates were inoculated on nutrient agar slants and preserved at −4°C for further study.

2.3 Primary screening to check the ability of different bacterial isolates to secrete cellulase enzymes

The efficacy of obtained bacterial isolates to secrete cellulase enzyme was investigated using mineral salt agar (MSA)media (containing g·L−1: NaNO3, 5; KH2PO4, 1; K2HPO4, 2; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5; KCl, 0.1; CaCl2, 0.01; FeSO4·7H2O, 0.02; agar, 15, dH2O, 1 L; pH = 7) supplemented with 5 g (w/v) CMC powder and sterilized at 120°C (1.5 psi) for 20 min [18]. Under aseptic conditions, the sterilized MSA media was poured onto Petri dishes and inoculated with purified bacterial isolate in the center upon solidification. The inoculated plate was incubated for 24 h at 45°C followed by being flooded with Lougle’s iodine solution. The appearance of a clear zone around bacterial growth indicates the efficacy of the bacterial isolate to secrete cellulase enzymes. The results recorded the diameter of a clear zone (mm). The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.4 Traditional and molecular identification of the most potent bacterial isolate

According to standard keys, the high cellulase enzyme producer coded as M7 was subjected to morphological, physiological, and biochemical identification [19]. Various biochemical and physiological tests such as coagulase, urease, oxidase, catalase, oxidation/fermentation (O/F) test, IMVC (indole test, methyl red test, Voges–proskauer test, and citrate utilization) test carbohydrate fermentation, hydrogen sulfide test, and gelatin and starch hydrolysis were performed.

The universal primers of 27 f (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGGCTC AG-3′) and 1492r (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACTT-3′) were used for amplification of the 16 s rRNA gene [20]. The PCR tube contained: 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer, 2.5U Taq-DNA polymerase (QIAGEN), 0.5 μM of universal primer, 0.25 mM dNTP, and 5 ng of genomic DNA. The analysis was achieved according to the following protocol: 3 min at 94°C, 0.5 min at 94°C (30 cycles), 0.5 min at 55°C, 1 min at 72°C, and the final step was extended for 10 min at 72°C [21]. The Applied Biosystem’s 3730xl DNA Analyzer technology was used to sequence (forward and reverse) the PCR product. This analysis was performed at Sigma Company, Cairo, Egypt. The obtained sequence was compared with those deposited on the GenBank using the NCBI BLAST nucleotide. The neighbor-joining method using MEGA (version 6.1) software was used to construct the phylogenetic tree with confidence level of 1,000 repeats.

2.5 Quantitative assay of cellulase activity and protein concentration

The activity of the cellulase enzyme was detected through the detection of the amount of reducing sugars from the CMC substrate by using the dinitrosalicylic acid method (DNS) [22]. In this method, 1 mL of 1% (w/v) CMC (prepared in phosphate buffer, pH 7) was added to a test tube, followed by 200 µL of culture filtrate and mixed well. The previous mixture was incubated at 45°C for 30 min. At the end of the incubation period, 1 mL DNS reagent was added and subjected to boiling in a water bath at 100°C for 5 min. After cooling, the color intensity on spectrophotometry was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm. The amount of reducing sugars released was measured using a glucose standard curve. One unit of cellulase enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of reducing sugar per minute. The total soluble protein was detected using the Bradford method [23]. This method depends upon the binding of CBB G-250 with protein and the color of the reaction converts into blue from light green. The CBB was prepared by dissolving the CBB dye (100 mg) in 50 mL ethanol 95%. Orthophosphoric acid (85%) was added to complete the dye solution to 100 mL followed by diluting with dH2O to reach a total of 200 mL. The absorbance of the formed color was read using spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 595 nm.

2.6 OFAT optimization

The bacterial isolates were subjected to different environmental conditions for the detection of the best parameters that give the maximum cellulase production using OFAT. To achieve this goal, the mineral broth media was prepared and supplemented with CMC powder, autoclaved, and inoculated upon cooling with 2% (v/v) of overnight bacterial culture. During the experiment, different environmental factors, including pH values (6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), temperature (30°C, 35°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C), inoculum size (1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% v/v after adjusting the optical density (OD) of bacterial culture at 1.0), the incubation period (6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 h), different nitrogen sources (ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride, ammonium hydrogen orthophosphate, beef extract, urea, and peptone), and different CMC concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 g·L−1) were investigated.

The investigation of each parameter was achieved by keeping all other parameters at optimum conditions. At the end of the incubation period of each factor, approximately, 2 mL of incubated media were taken and subjected to centrifugation under 4°C for 10 min at 7,000 rpm, followed by a collection of supernatants used for the detection of cellulase activity using the DNS method as mentioned above. Each factor was achieved in triplicate.

2.7 Optimization with BBD

In this study, a BBD was used to improve the optimization factors to get maximum cellulase productivity by bacterial strain M7 based on optimizing factors using OFAT. This test was used for the investigation of the combined effect of six variables: temperature, pH, inoculum size, CMC concentration, bacterial incubation time, and different nitrogen sources. Table 1 shows the three levels (+1, 0, −1) that were used in the experimental design [24]. The Box- Behnken design was used to get higher-order response surfaces using fewer required runs than a normal factorial technique. Also, the BBD is used with wide shape for the preparation of quadratic response surfaces and a second-degree polynomial model to analyze the pattern of enzyme production. According to the second-degree polynomial model, the optimization process was carried out by a set of experimental runs [25]. To maintain the higher order surface definition, the BBD essentially suppresses selected runs in an attempt (version 12, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, USA), where this design with statistical software is used to obtain the best cellulase activity. The experimental design depends upon this equation N = k2 + k + Cp for setting up a number of runs (N), where k and Cp are the factor number and replications number, respectively. The predicted model in this study, derived from a second-degree polynomial equation, was based on 54 distinct experimental runs. By using the second-degree polynomial equation in the current work, the predicated model was 54 different experimental runs. The representation of the predicted model as a second-degree polynomial equation is as follows:

where Y is the anticipated response; β 0 is the show constant; A, B, C, D, E, and F are the free factors; β 1, β 2, β 3, β 4, β 5, and β 6 are the direct coefficients; β 12, β 13, β 14, β 15, β 16, β 23, β 24, β 25, β 26, β 34, β 35, β 36, β 45, β 46, and β 56 are the cross-product coefficients, and β 11, β 22, β 33, β 44, β 55, and β 66 are the quadratic coefficients

Different factors, units, and their levels are used in BBD for cellulase production

| Factor name | Units | −1 | 0 | +1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | A | °C | 33 | 35 | 37 |

| pH | B | — | 6.5 | 7 | 7.5 |

| Inoculum size | C | % | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Nitrogen source | D | g·L−1 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| Incubation period | E | h | 20 | 24 | 28 |

| CMC | F | g·L−1 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

In this study, there were six factors that formed the BBD: temperature (A) [30°C, 35°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C], pH (B) [6, 7, 8, 9, and 10], inoculum size (C) [1%, 2%, 3%, and 4%], nitrogen source (D) [NH4NO3, NH4H2PO4, NH4CL, yeast extract, urea, and peptone], the incubation period (E) [6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 h], and CMC concentration (F) [2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 g·L−1] for cellulase production. Further, the RSM data were undertaken.

2.8 Extraction and purification of cellulase enzyme

The extraction and purification steps for the cellulase enzyme were carried out at 4°C. The mineral salt (MS) broth after cultivation was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min and mixed with ammonium sulfate at varied concentrations (10–80%) to concentrate the cellulase enzyme in the cell-free supernatant. Ammonium sulfate fractions were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min followed by dissolving in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to form turbid suspension which was subjected to centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000 rpm to form clear supernatant [26]. The collected final clear supernatant was subjected to more purification by dialysis bag and column chromatography.

2.9 Partial purification with dialysis process

The crude supernatant obtained from the ammonium sulfate step was kept in a dialysis bag and put beaker against dH2O for 3 h followed by transfer to a phosphate buffer (pH 7). After that, the dialysis bag containing cellulase enzyme was concentrated by putting it in a beaker against sucrose crystals and kept in the refrigerator at 4°C for further purification.

2.10 Complete purification using Sephadex G-100 chromatography

The Sephadex G-100 column (1.5 × 50 cm) was equilibrated, by using phosphate buffer. The concentrated cellulase fraction obtained from the dialysis bag was subjected to complete purification through loading onto the column and chromatographed by using phosphate buffer subsequently. Each 5 mL from the flow rate column (5 mL·h−1) was collected to detect the active fractions.

2.11 Characterization of cellulase enzyme

2.11.1 TLC mass spectroscopy for molecular weight detection

The molecular weight of purified cellulase enzyme was detected by Advion compact mass spectrometer NY, USA under the following specifications: Ion source (ESI, APCI, or APCI/ASAP), polarity (positive & negative ion switching in a single analysis), flow rate range (ESI: 10µL·min−1 to 1 mL·min−1 and APCI: 10 µL·min−1 to 2 mL·min−1), m/z range (expression S m/z 10–1,200 and expression L m/z 10–2,000), sensitivity (ESI): 10 pg reserpine (FIA – 5 µL injection at 100 µL·min−1) 100:1 S/N (RMS) with SIM of m/z 609.3, NB standard sulphadiazine (M. wt = 250) was injected to assure the quality of analysis.

2.11.2 Amino acids

The amino acids composition of cellulase enzyme was detected by Sykam Amino Acid Analyzer (Sykam GmbH, Germany) equipped with Solvent Delivery System S 2100 (Quaternary pump with flow range 0.01–10.00 mL·min−1 and maximum pressure up to 400 bar), Autosampler S 5200, Amino Acid Reaction Module S4300 (with built-in dual filter photometer between 440 and 570 nm with constant signal output and signal summary option), and Refrigerated Reagent Organizer S 4130, where the standard is prepared as follows, Stock solution contains 18 amino acids (aspartic acid, threonine, serine, glutamic acid, proline, glycine, alanine, cystine, valine, methionine, isoleucine, leucine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, histidine, lysine, ammonia, and arginine) at a concentration of 2.5 µMol·mL−1, except cystine which is 1.25 µMol·mL−1, then dilute 60 µL in 1.5 mL vial with sample dilution buffer, then filter using 0.22 µm syringe filter and then 100 µL was injected. The sample was prepared by mixing 1 gm of the sample with 5 mL hexane. The mixture was allowed to be macerated for 24 h. Then, the mixture was filtered on Whatman no. 1 filter paper and the residue was transferred into a test tube where it was incubated in an oven with 10 mL 6 N HCl for 24 h at 110°C. After the incubation, the sample was filtered on Whatman no. 1 filter paper, evaporated on a rotary evaporator, and dissolved completely in 20 mL of dilution buffer, filtered using 0.22 µm syringe filter, and 100 µL was injected.

2.12 Application of cellulase on bio-polishing of cotton fabric

The treatment of cotton fabrics with bacterial cellulase enzyme was carried out at various concentrations (0.25%, 0.5%, and 1%) at different times (30, 60, and 90 min). The experimental conditions for the treatment of cotton fabrics with cellulase enzyme are illustrated in Table 2. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used as a control to compare the weight loss of cotton fabrics with those obtained due to cellulase treatment. At the end of each treatment, the weight loss was calculated using the following equation [27]:

Experimental design for the treatment of cotton fabrics with cellulase enzyme

| Factor | Recipe using a less amount of cellulase | Recipe using a medium amount of cellulase | Recipe using a heavy amount of cellulase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulase | 0.25% | 0.50% | 1.0% |

| Acetic acid (100%) | 0.5 g·L−1 | 0.5 g·L−1 | 0.5 g·L−1 |

| Temperature | 55°C | 55°C | 55°C |

| Time | 30, 60, and 90 min | 30, 60, and 90 min | 30, 60, and 90 min |

| pH | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4– 5 |

| Hot wash | 90°C for 10 min | 90°C for 10 min | 90°C for 10 min |

2.13 Statistical analysis

In the current study, all results are the mean values of three independent replicates. Data were subjected to analysis of variance one-way (ANOVA) by a statistical package Minitab v19. The mean difference comparison between the treatments was analyzed by the Tukey HSD at P < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Isolation, primary screening, and identification of bacterial isolates

From the collected water and soil samples, 36 bacterial isolates were obtained which showed high efficacy in growing at 45°C. From these isolates, it was found that 19 (52.8%) bacterial isolates can produce cellulase enzyme that was detected by rapid qualitative agar plate through the appearance of a clear zone around the bacterial growth after flooding the plate with Logule’s iodine solution (Table 3). Whereas the remaining bacterial isolates (17 isolates which represented 47.2% of the total isolates) did not have the efficacy to produce cellulase enzyme. The producer bacterial isolates were classified based on clear zones as follows: low producers (6 isolates represented by 11.4% of the total producer isolates) that formed clear zone in the range of 10–20 mm, moderate producers (12 isolates represented by 63.2%) that produce clear zone in the ranges of 20–30 mm, and high producers (1 isolate, 5.3%) that formed clear zone above 30 mm.

Primary qualitative screening test to produce cellulase enzyme

| Bacterial isolate | Isolation source | Cellulase | Bacterial isolate | Isolation source | Cellulase | Bacterial isolate | Isolation source | Cellulase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Water | − | M13 | Water | − | M25 | Soil | − |

| M2 | Water | − | M14 | Water | − | M26 | Soil | + |

| M3 | Water | ++ | M15 | Water | − | M27 | Soil | − |

| M4 | Water | ++ | M16 | Water | − | M28 | Soil | ++ |

| M5 | Water | − | M17 | Water | ++ | M29 | Soil | − |

| M6 | Water | + | M18 | Water | ++ | M30 | Soil | ++ |

| M7 | Water | +++ | M19 | Water | ++ | M31 | Soil | − |

| M8 | Water | − | M20 | Water | − | M32 | Soil | − |

| M9 | Water | ++ | M21 | Water | + | M33 | Soil | ++ |

| M10 | Water | + | M22 | Soil | ++ | M34 | Soil | − |

| M11 | Water | + | M23 | Soil | − | M35 | Soil | − |

| M12 | Water | ++ | M24 | Soil | + | M36 | Soil | ++ |

(−) = negative, (+) = 10–20 mm, (++) = 20–30 mm, (+++) = 30–40 mm.

Based on the primary survey, the bacterial isolate designated as M7 was selected due to its high-producing cellulase enzyme. Similarly, among 84 bacterial isolates obtained from serially diluted soil samples, 24 (28.6%) isolates have the efficacy to form a clear zone around the bacterial growth after growing on the LB agar plates supplemented with 1% CMC when flooded the plates with 1% Congo red [28]. Also, among 20 bacterial isolates obtained from soil and cow dung samples, 16 (80%) isolates can form a halo zone around the bacterial colony on the CMC agar plate when flooded with Congo red [29].

The selected most potent cellulase-producer bacterial isolate M7 was subjected to traditional identification based on some morphological, physiological, and biochemical tests according to key standards. The bacterial isolate M7 appeared as Bacilli, Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic, spore former, exhibiting weekly growth at 55–60°C, and the growth was completely inhibited at 20°C. The bacterial isolate showed positive results for the Vogues–Proskauer test, nitrate reduction, methyl red test, and citrate utilization. Also, it has the efficacy of fermenting different sugars including maltose, mannose, glucose, galactose, fructose, xylose, arabinose, and starch forming acid and gas. Interestingly, the catalase and oxidase tests were positive but did not have the potential to break down tryptophane to form indole. Based on the above results, the bacterial strain may belong to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens [19].

The molecular identification based on amplification and sequencing of the 16 s rRNA gene was used to confirm the identification of the bacterial strain. Sequence analysis showed that the bacterial strain M7 was similar to B. amyloliquefaciens that was deposited in GenBank under accession number NR117946 with similarity percentages of 99.8%. Therefore, the selected bacterial strain in the current study was identified as B. amyloliquefaciens. Moreover, the obtained sequence was loaded in GenBank with accession number ON514179 (Figure 1). Bacillus species are widely recognized for their ability to produce a diverse range of enzymes, including cellulase, amylase, gelatinase, xylanase, and more [22,30,31]. Among Bacillus species, B. amyloliquefaciens has the potential to produce cellulase enzymes. For instance, B. amyloliquefaciens DL3 showed cellulase activity at temperature and pH values of 50°C and 7, respectively [32]. Also, B. amyloliquefaciens S1 has the potential to secrete cellulase enzyme at the optimum temperature of 37°C and pH value of 7 [33].

Phylogenetic tree of the bacterial strain M7 based on 16 s rRNA sequences analysis compared with NCBI reference sequences and identified as B. amyloliquefaciens M7. MEGA 6 was used to achieve the analysis, which used the neighbor-joining approach with a bootstrap value (1,000 replicates).

3.2 Optimizing the cellulase production using OFAT

While choosing the suitable strain is important for the effectiveness of enzyme production, attaining maximum enzyme yield is not assured unless the production process and culture conditions are appropriately fine-tuned. To attain this maximum cellulase productivity, different culture conditions such as pH, temperature, inoculum size, incubation period, nitrogen source, and CMC concentration were optimized.

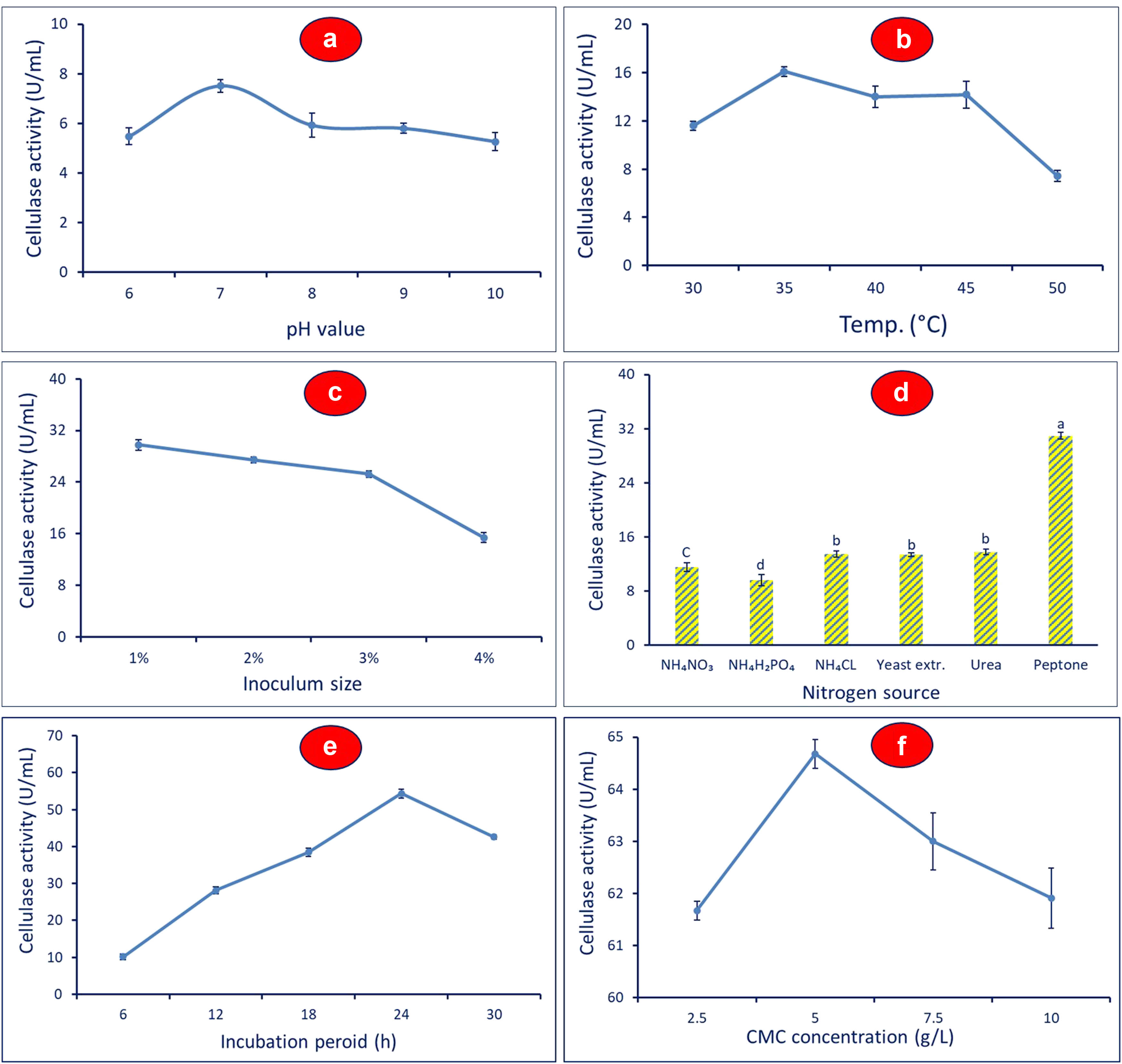

The pH of the fermented culture has a significant role in increasing the enzyme activity and physiology of microorganisms. Accordingly, different pH values (6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) were used for the incubation of B. amyloliquefaciens M7 for 24 h to study the effect of pH on enzyme activity. ANOVA showed that the maximum cellulase activity of 7.5 ± 0.03 U·mL−1 was attained at a pH value of 7 (P ≤ 0.001), which was partly decreased to 5.5 ± 0.5 and 5.3 ± 0.7 U·mL−1 at pH 6 and 10, respectively (Figure 2a). As shown, the cellulase activity at pH values of 6, 8, 9, and 10 were not significant (P = 1.00). From these data, it was observed that either acidity or alkalinity has a deleterious effect on bacterial strain M7 and hence has a negative impact on cellulase activity. This finding could be attributed to the variation in pH values leading to alterations in its ionic bonding due to the loss of functional shape. Also, the deleterious effect of extreme pH value could be due to the denaturation of enzymes by the unfavorable ionic state [34]. Furthermore, the enzyme’s active site is most effective in binding substrate and catalyzing reactions at neutral value. Additionally, at pH 7, the enzyme is more stable, meaning it can keep its structure and activity throughout time without degrading. In a similar study, the maximum cellulase production (1.5 U·mL−1) by B. amyloliquefaciens ASK11 was accomplished at a neutral pH value [35]. On the other hand, Yang and co-authors reported that the optimum pH value of culture media for maximum cellulose hydrolysis and hence secretion of cellulase enzyme was in the range of 7–9 [36]. Generally, due to variances in components of the media and bacterial specificities, the optimal pH value for cellulase production differs among microorganisms [37,38]. Many published literature reported that the optimum pH value for maximum cellulase production was 7 [32,35].

Optimizing factors affect cellulase activity using the OFAT method. (a) pH, (b) temperature, (c) inoculum size, (d) nitrogen source, (e) incubation period, and (f) CMC concentration. Different letters between columns denote that mean values are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) by the Tukey test, mean values ± SD (n = 3).

Temperature is a second important factor that affects bacterial growth and hence cellulase activity. To investigate the effect of different temperature degrees, the bacterial strain B. amyloliquefaciens M7 was inoculated in MS broth media supplemented with CMC and incubated for 24 h at varied degrees (30°C, 35°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C). Data analysis showed that the best temperature for getting the maximum cellulase activity (16.1 ± 0.4 U·mL−1) was 35°C (P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2b). The enzyme’s kinetic energy is maximized at this temperature, allowing for more rapid enzymatic reactions. In addition, the enzyme’s structure and activity are preserved, ensuring peak performance [10,39]. The disparity in the production of enzymes using microbes under varied temperature degrees could be related to the physical alterations it induced in the cells. It has been shown that most Bacillus spp. have the efficacy for the secretion of optimal yield from cellulase enzyme when grown within the mesophilic temperature range [33,40]. In a similar study, the optimum cellulase activity (6 U·mL−1) from B. albus was attained at mesophilic temperature degree (35°C) [9]. In the current study, the lowest cellulase activity (7.4 ± 0.05 U·mL−1) was observed at a temperature of 50°C followed by cultivation at 30°C (11.6 ± 0.4 U·mL−1), which showed significant difference (P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2b).

As shown, the maximum cellulase activity (29.8 ± 0.2 U·mL−1) was attained at inoculum size 1% (v/v) which showed high significance compared to other treatments (P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2c). Unfortunately, the cellulase enzyme activity was decreased with increase in the inoculum sizes. As shown, the enzyme activity was 27.5 ± 0.4, 25.2 ± 0.2, and 15.4 ± 0.2 U·mL−1 at an inoculum size of 2%, 3%, and 4%, respectively. This finding could be related to the phenomenon of competition for resources and/or substrate inhibition. The space for bacterial growth and nutrients may be limited at high bacterial inoculum size. the metabolic activity and enzymatic production can be decreased due to competition among the bacterial community on resources, further contributing to the reduced cellulase activity [41]. Cellulase enzymes hydrolyze their substrate (cellulose) into smaller sugars. With larger bacterial inoculum sizes, both bacterial concentration and the production of metabolic byproducts increase. Consequently, there is a greater presence of end products like cellobiose or glucose, which can potentially impede cellulase activity [42]. At high enough concentrations, these byproducts can compete with cellulase enzymes for access to the cellulose substrate and inhibit the enzymes’ ability to catalyze the reaction. The overall cellulase activity is diminished as a result of this substrate inhibition. Similarly, the maximum cellulase production using B. licheniformis 1–1 v was achieved when the inoculum size was set at 1%, while enzyme activity decreased significantly at higher concentrations (2%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%) [43].

Another important factor that affects cellulase activity is the addition of extra-organic and inorganic nitrogen sources to fermentative media. To achieve this goal, different nitrogen sources including NH4NO3, NH4H2PO4, NH4Cl, beef extract, urea, and peptone were used. ANOVA showed that the maximum cellulase activity (30.9 ± 0.1 U·mL−1, P ≤ 0.001) was attained in the presence of peptone, whereas the addition of other nitrogen sources leads to a decrease in the enzyme activity (Figure 2d). Peptone is an organic nitrogen source containing amino acid, peptide-rich protein, inorganic salts, vitamins, lipids, and sugars [44]. It provides a wide range of nitrogen-containing compounds and other important elements that serve as a readily available and balanced source of nutrients for bacterial growth and enzyme production. The presence of peptides and amino acids in peptone provides multiple nitrogen sources that can be utilized by the bacterial species. This guarantees that the essential amino acids required for protein synthesis and enzyme production are present in adequate and balanced amounts. Unlike inorganic nitrogen sources like NH4NO3, NH4H2PO4, and NH4Cl, the nitrogen in peptone is in an organic form, making it more assimilated by bacteria. Microbial biomass may quickly metabolize and absorb peptone’s organic nitrogen, leading to increased cell development and metabolic activity. Therefore, the bioavailability and balance of nutrients that are present in peptone can enhance bacterial growth and metabolism, resulting in improved cellulase enzyme production. This, in turn, leads to higher cellulase activity in the fermentative media compared to other nitrogen sources tested. Compatible with the obtained results, Khadiga and coauthors reported that the organic nitrogen source (yeast extract) was the best for the maximum cellulase activity synthesized by B. alcalophilus S39 and B. amyloliquefaciens C2 [45].

The incubation period played an important role in the cellulase activity of B. amyloliquefaciens. The best incubation time with maximum cellulase activity (54.3 ± 0.1 U·mL−1, P ≤ 0.05) was at 24 h (Figure 2e). Before 24 h, the bacterial strain undergoes a lag phase where they adapt to the new environment and start metabolizing the available nutrients. This is followed by an exponential phase where the population of bacterial strains increases rapidly. However, after an optimum incubation period, cellulase activity was decreased because the metabolic activity of bacterial species started to decline due to the reduction in nutrients or the accumulation of other harmful metabolites in the growth media.

Finally, the concentration of enzyme precursor (CMC) in fermentative media is a critical factor for enhancing the activity. As shown, the maximum cellulase activity (64.7 ± 0.3 U·mL−1, P ≤ 0.001) using B. amyloliquefaciens M7 strain was accomplished at 5 g·L−1 CMC (Figure 2f). The cellulase activity decreased gradually both above and below this concentration due to the phenomenon known as substrate inhibition [46]. The availability of CMC at low concentrations may be limited leading to lower cellulase activity because of the insufficient substrate that the enzyme acts upon it. Whereas the substrate inhibition phenomenon occurred at high CMC concentrations. As a result of high substrate concentrations, the end products or intermediate metabolites can be accumulated and hence inhibit the cellulase enzymes by reacting with enzyme active sites or hindering their catalytic activity, ultimately decreasing the enzyme activity. Therefore, it can be concluded that the balance between enzyme activity and substrate concentration is a critical factor that should be optimized. Below or above the optimum concentration, it will have a negative impact on enzyme activity due to the substrate being insufficient or the occurrence of substrate inhibition phenomenon. Also, it is worth noting that the optimum CMC concentrations can change compared to published literature due to the type of microorganisms, cellulase enzyme, and experimental conditions.

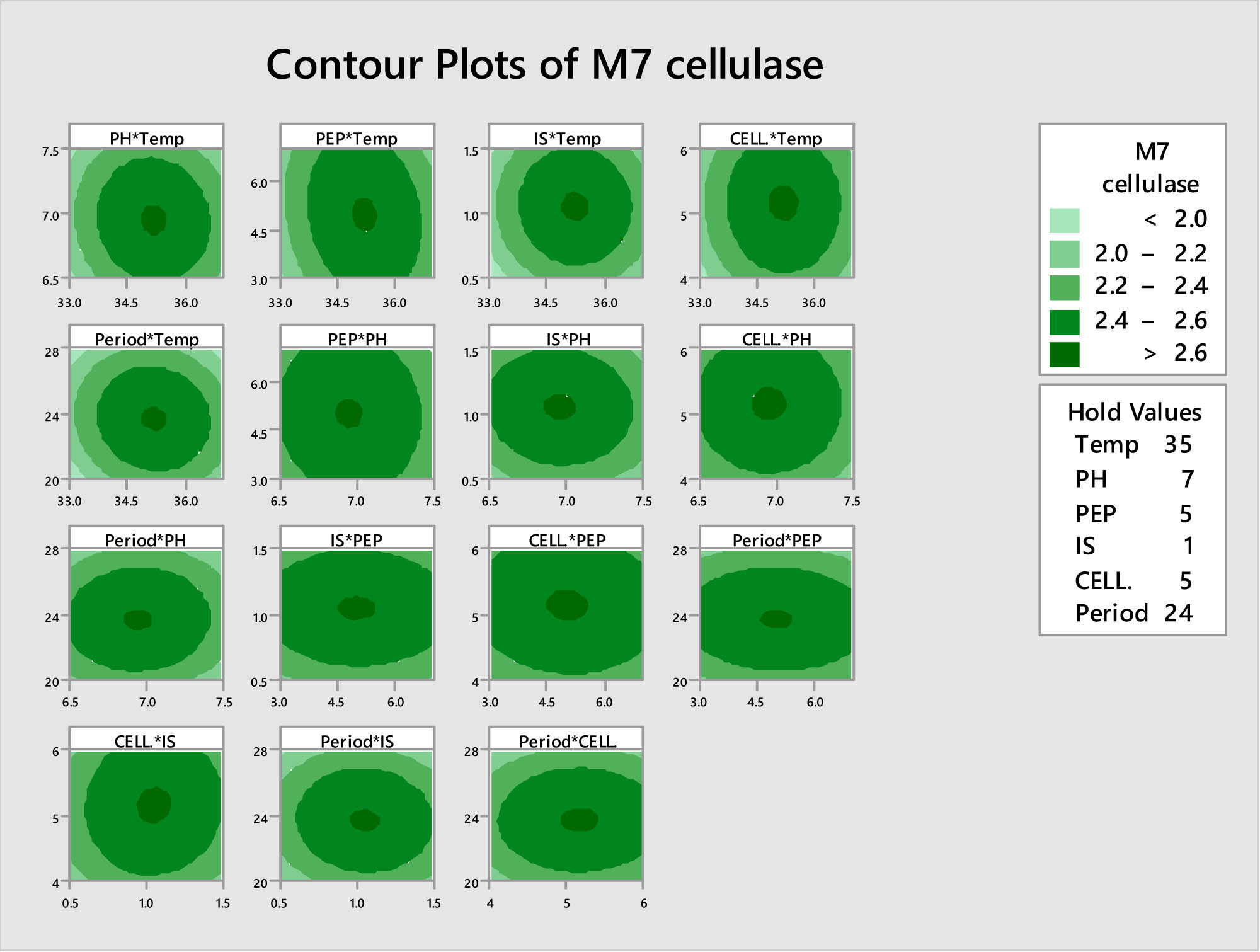

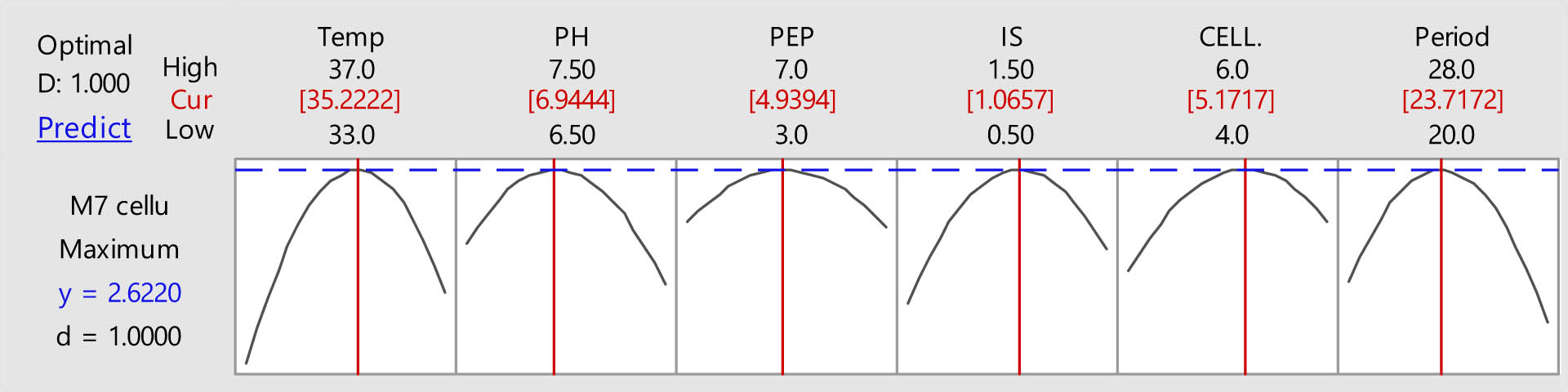

3.3 Optimization using BBD

The optimizing factors for cellulase production were confirmed using the BBD. This statistical experimental design is a response surface methodology that allows for the efficient exploration of multiple factors and levels to identify optimal conditions. In the current study, six factors including pH, temperature, inoculum size, concentration of nitrogen source (peptone), incubation period, and concentration of substrate (CMC) based on the OFAT method were investigated. Each factor was varied at six different levels to evaluate their impact on the production of cellulase enzyme. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, and Figure 3, the cellulase activity ranged from 36.94 to 64.98 U·mL−1 across all statistical experimental runs. Run no. 13 exhibited the maximum cellulase activity with values of 64.98 U·mL−1. As shown the specific conditions during this run were as follows: pH = 7, temperature = 35°C, peptone concentration = 5 g·L−1, bacterial inoculum size = 1%, substrate (CMC) concentration = 5 g·L−1, and incubation period = 24 h.

Result of BBD for cellulase production by M7 strain

| Run | Temp. | pH | Peptone | Inoculum size | CMC conc. | Period | Enzyme activity (U·mL−1) | Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 44.68 | 43.9396 |

| 2 | 35 | 6.5 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 52.76 | 51.8879 |

| 3 | 37 | 6.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 24 | 45.18 | 45.8283 |

| 4 | 35 | 7 | 7 | 0.5 | 5 | 28 | 47.42 | 45.5304 |

| 5 | 33 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 41.93 | 41.1196 |

| 6 | 35 | 7 | 3 | 0.5 | 5 | 20 | 49.49 | 45.5988 |

| 7 | 33 | 6.5 | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 24 | 45.27 | 44.1267 |

| 8 | 37 | 7 | 5 | 0.5 | 4 | 24 | 43.40 | 44.9300 |

| 9 | 33 | 7.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 24 | 39.19 | 40.2058 |

| 10 | 37 | 7 | 5 | 1.5 | 4 | 24 | 45.03 | 45.9208 |

| 11 | 37 | 7 | 5 | 1.5 | 6 | 24 | 52.83 | 49.6575 |

| 12 | 35 | 7 | 3 | 1.5 | 5 | 20 | 50.14 | 50.1296 |

| 13 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 14 | 35 | 6.5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 53.01 | 54.0421 |

| 15 | 33 | 7 | 5 | 1.5 | 6 | 24 | 46.39 | 46.6650 |

| 16 | 35 | 6.5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 20 | 49.74 | 47.8421 |

| 17 | 35 | 7.5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 52.21 | 52.6346 |

| 18 | 35 | 7 | 7 | 1.5 | 5 | 28 | 44.68 | 46.6713 |

| 19 | 33 | 7 | 5 | 1.5 | 4 | 24 | 40.24 | 42.2683 |

| 20 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 21 | 37 | 6.5 | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 24 | 48.39 | 49.1792 |

| 22 | 37 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 46.69 | 46.0971 |

| 23 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 24 | 35 | 6.5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 20 | 50.66 | 50.7863 |

| 25 | 37 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 47.12 | 49.7604 |

| 26 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 27 | 35 | 7 | 3 | 1.5 | 5 | 28 | 47.17 | 47.6513 |

| 28 | 33 | 7 | 5 | 0.5 | 4 | 24 | 38.44 | 39.8075 |

| 29 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 30 | 35 | 7 | 3 | 0.5 | 5 | 28 | 44.68 | 45.6954 |

| 31 | 35 | 7.5 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 49.72 | 49.1354 |

| 32 | 35 | 6.5 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 52.91 | 54.3171 |

| 33 | 35 | 6.5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 51.66 | 50.2329 |

| 34 | 33 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 37.74 | 39.8379 |

| 35 | 35 | 7 | 7 | 1.5 | 5 | 20 | 49.67 | 50.5546 |

| 36 | 35 | 6.5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 28 | 49.17 | 48.1829 |

| 37 | 33 | 6.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 24 | 36.94 | 39.3058 |

| 38 | 35 | 7.5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 50.11 | 49.1504 |

| 39 | 37 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 48.29 | 47.2004 |

| 40 | 35 | 7.5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 20 | 47.17 | 47.6588 |

| 41 | 35 | 7.5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 28 | 44.48 | 46.8254 |

| 42 | 33 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 45.37 | 44.0629 |

| 43 | 37 | 7.5 | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 24 | 44.68 | 44.1192 |

| 44 | 37 | 7.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 24 | 43.93 | 43.2683 |

| 45 | 35 | 7.5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 20 | 44.50 | 45.0396 |

| 46 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 64.98 | 64.9800 |

| 47 | 35 | 7.5 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 50.26 | 51.2396 |

| 48 | 33 | 7 | 5 | 0.5 | 6 | 24 | 44.68 | 41.9842 |

| 49 | 35 | 7.5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 28 | 44.43 | 43.8563 |

| 50 | 33 | 7.5 | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 24 | 44.98 | 42.5267 |

| 51 | 35 | 7 | 7 | 0.5 | 5 | 20 | 45.42 | 46.8388 |

| 52 | 37 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 42.33 | 42.1321 |

| 53 | 37 | 7 | 5 | 0.5 | 6 | 24 | 46.67 | 46.4467 |

| 54 | 35 | 6.5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 28 | 44.93 | 44.8888 |

Response Surface Regression of BBD for cellulase production vs different factors including temperature, pH value, inoculum size, peptone, incubation period, and CMC concentration

| ANOVA | Coded coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | F-value | P-value | Term | T-value | P-Value |

| Model | 23.08 | 0.000 | Constant | 79.53 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 10.28 | 0.000 | A | 4.97 | 0.000 |

| A | 24.66 | 0.000 | B | −2.55 | 0.017 |

| B | 6.49 | 0.017 | D | 0.16 | 0.876 |

| D | 0.02 | 0.876 | C | 3.47 | 0.002 |

| C | 12.04 | 0.002 | F | 3.62 | 0.001 |

| F | 13.11 | 0.001 | E | −2.32 | 0.028 |

| E | 5.38 | 0.028 | A × A | −15.10 | 0.000 |

| Square | 91.11 | 0.000 | B × B | −9.01 | 0.000 |

| A × A | 228.09 | 0.000 | D × D | −5.28 | 0.000 |

| B × B | 81.22 | 0.000 | C × C | −10.20 | 0.000 |

| D × D | 27.87 | 0.000 | F × F | −7.18 | 0.000 |

| C × C | 103.96 | 0.000 | E × E | −12.80 | 0.000 |

| F × F | 51.60 | 0.000 | A × B | −1.22 | 0.233 |

| E × E | 163.95 | 0.000 | A × D | −2.40 | 0.024 |

| Way interaction | 0.98 | 0.501 | A × C | −0.74 | 0.469 |

| A × B | 1.49 | 0.233 | A × F | −0.23 | 0.817 |

| A × D | 5.75 | 0.024 | A × E | −1.74 | 0.093 |

| A × C | 0.54 | 0.469 | B × D | −0.59 | 0.560 |

| A × F | 0.05 | 0.817 | B × C | −0.89 | 0.384 |

| A × E | 3.04 | 0.093 | B × F | −0.16 | 0.873 |

| B × D | 0.35 | 0.560 | B × E | 0.63 | 0.537 |

| B × C | 0.78 | 0.384 | D × C | −0.29 | 0.773 |

| B × F | 0.03 | 0.873 | D × F | −0.48 | 0.632 |

| B × E | 0.39 | 0.537 | D × E | −0.70 | 0.488 |

| D × C | 0.08 | 0.773 | C × F | 0.79 | 0.437 |

| D × F | 0.23 | 0.632 | C × E | −0.91 | 0.372 |

| D × E | 0.50 | 0.488 | F × E | 0.12 | 0.903 |

| C × F | 0.62 | 0.437 | |||

| C × E | 0.82 | 0.372 | |||

| F × E | 0.02 | 0.903 | |||

A is the temperature, B is the pH value, C is the bacterial inoculum size, D is the peptone as nitrogen source, E is the incubation period, and F is the CMC concentration.

The interaction between different factors and locating the optimal level of each factor for maximal production of cellulase from M7 strain.

The statistical BBD regression equation in uncoded units was as follows:

where A is the temperature, B is the pH, C is the inoculum size, D is the nitrogen source, E is the incubation period, and F is the CMC concentration.

In a similar study, the maximum cellulase activity (26.26 IU·gds−1) synthesized by B. subtilis M-11 was attained after optimizing conditions using BBD at run 27 with specific conditions of pH = 7.5, incubation temperature = 42°C, after an incubation period of 72 h [47]. In the current study, the constructed experimental model is highly significant and accurately portrays the real connection between the impacts of factors and enzyme response linked to cellulase activity according to the ANOVA analysis. The expected vs actual plots and normal residual plots of cellulase activity of the cellulolytic bacterial strain B. amyloliquefaciens showed more stability in the residual plot (Figure 4). The distribution of response variables from several experimental circumstances revealed that most of the components contributed equally. The likelihood graphs also showed that the expected and real cellulase activities were quite comparable.

The validation of predicted and actual cellulase production by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7.

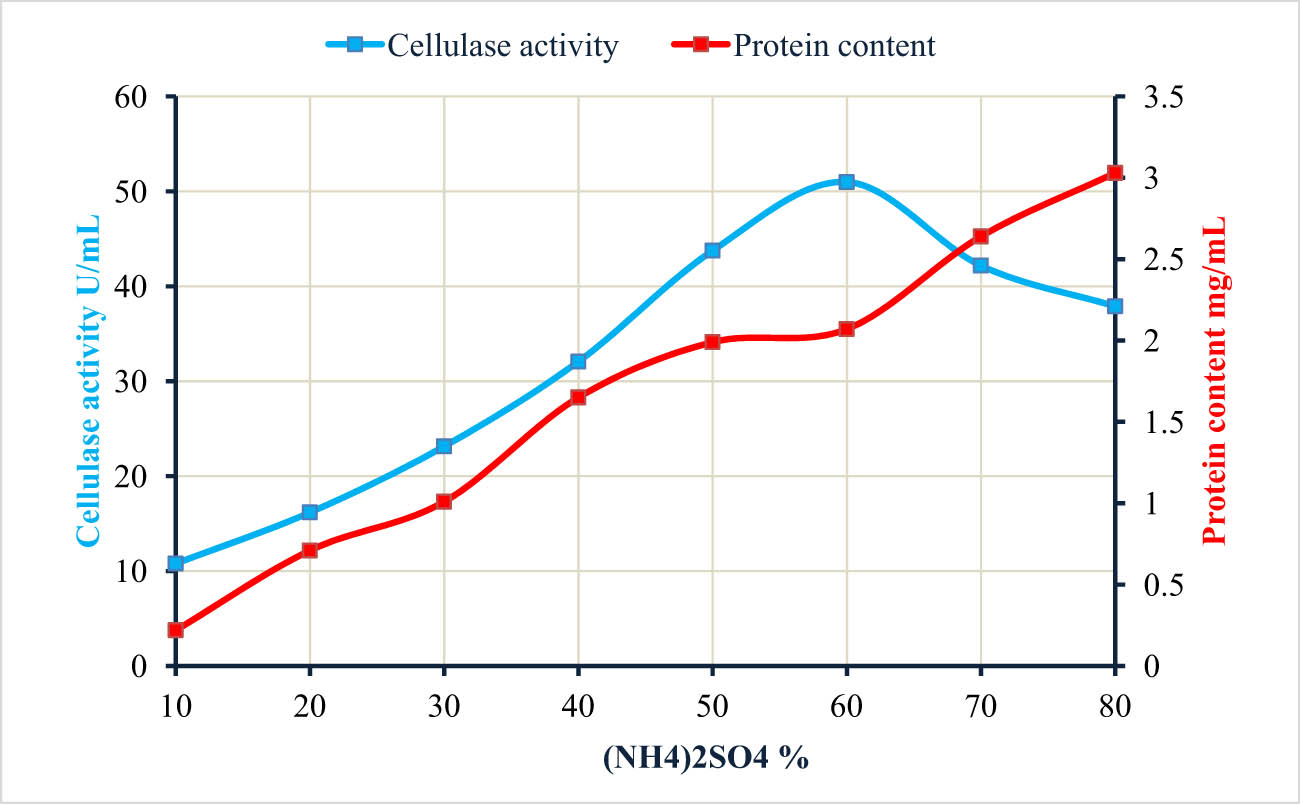

3.4 Purification of cellulase enzyme

The B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7 was used to produce cellulase enzyme under all optimum fermentation conditions. Following the incubation period, proteins were precipitated using varying concentrations (10–80%) of ammonium sulfate (NH4)2SO4. In contrast to the increased protein precipitation with increasing (NH4)2SO4 concentrations, the activity of the cellulase enzyme showed the highest increase up to a concentration of 60% (NH4)2SO4, after which it decreased with further concentration increases (Table 6, Figure 5). The obtained data are incompatible with those reported that the highest protein precipitation and cellulase enzyme activity produced by B. subtilis was attained at a concentration of 80% (NH4)2SO4 [48]. (NH4)2SO4 is a common salt used for protein precipitation via the phenomenon of salt-out and the continuous precipitation with the increase in the concentration of (NH4)2SO4 indicates the efficacy of salt to precipitate protein present in the solution. At certain salt points, the cellulase enzyme activity was enhanced due to it providing a favorable condition for an enzyme to work through ion pair formation or other interactions that improve the stabilization of enzyme structure [49]. At high salt concentrations (in the current study, above 60%), the cellulase activity was decreased because of a phenomenon known as salt inhibition or salt-induced enzyme inactivation. The enzyme structure or function can be disrupted at high salt concentration, which affects enzyme active sites, enhances protein aggregation, or alters the enzyme’s conformation, leading to a decrease in the enzyme’s catalytic activity and reduces their efficiency [50]. Therefore, the optimization between salt concentrations and cellulase enzyme activity is an important step to prevent enzyme inhibition or denaturation.

Partial and complete purification of cellulase enzyme produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7

| Sample | Total volume (mL) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Specific activity (U·mg−1) | Purification fold | Yield % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude enzyme | 50 | 206.21 | 1,956.93 | 9.49 | 1 | 100 |

| (NH4)2SO4 60% | 29 | 100.09 | 1,478.33 | 14.77 | 1.56 | 75.53 |

| Dialysis process | 21 | 58.31 | 1,346.96 | 23.10 | 2.43 | 68.81 |

| Sephadex G-100 | 50 | 23.51 | 1,423.295 | 60.54 | 6.38 | 72.71 |

Protein precipitation and cellulase enzyme activity due to treatment with different (NH4)2SO4 concentrations.

In the current study, the specific activity of the cellulase enzyme was 23.10 U·mg−1 after being subjected to a dialysis bag against sugar (sucrose) as shown in Table 7. The concentrated enzyme from the dialysis process underwent complete purification by loading it on a Sephadex G-100 column and receiving ten fractions, each one containing 5 mL of purified cellulase enzyme, followed by detection of cellulase activity, protein content, and specific enzyme activity for each fraction (Table 7). Data showed that the highest enzyme activity was attained in fraction number 6 with enzyme activity, protein content, and specific enzyme activity values of 91.22 U·mL−1, 0.86 mg·mL−1, and 97.95 U·mg−1, respectively. According to the obtained data, the cellulase enzyme activity varied due to purification steps.

Different fractions were obtained from Sephadex G100 column chromatography for complete purification of cellulase enzyme produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7

| Fraction no. | Specific enzyme activity (U·mg−1) | Protein content (mg·mL−1) | Cellulase activity (U·mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.08 | 10.32 | 1.33 |

| 3 | 1.72 | 7.87 | 13.02 |

| 4 | 14.08 | 1.65 | 39.63 |

| 5 | 52.47 | 0.97 | 78.99 |

| 6 | 97.95 | 0.86 | 91.22 |

| 7 | 48.37 | 0.73 | 36.99 |

| 8 | 35.75 | 0.57 | 15.76 |

| 9 | 12.65 | 0.34 | 6.19 |

| 10 | 3.75 | 0.20 | 1.52 |

3.5 Characterization of purified cellulase enzyme

3.5.1 Molecular weight and amino acid content

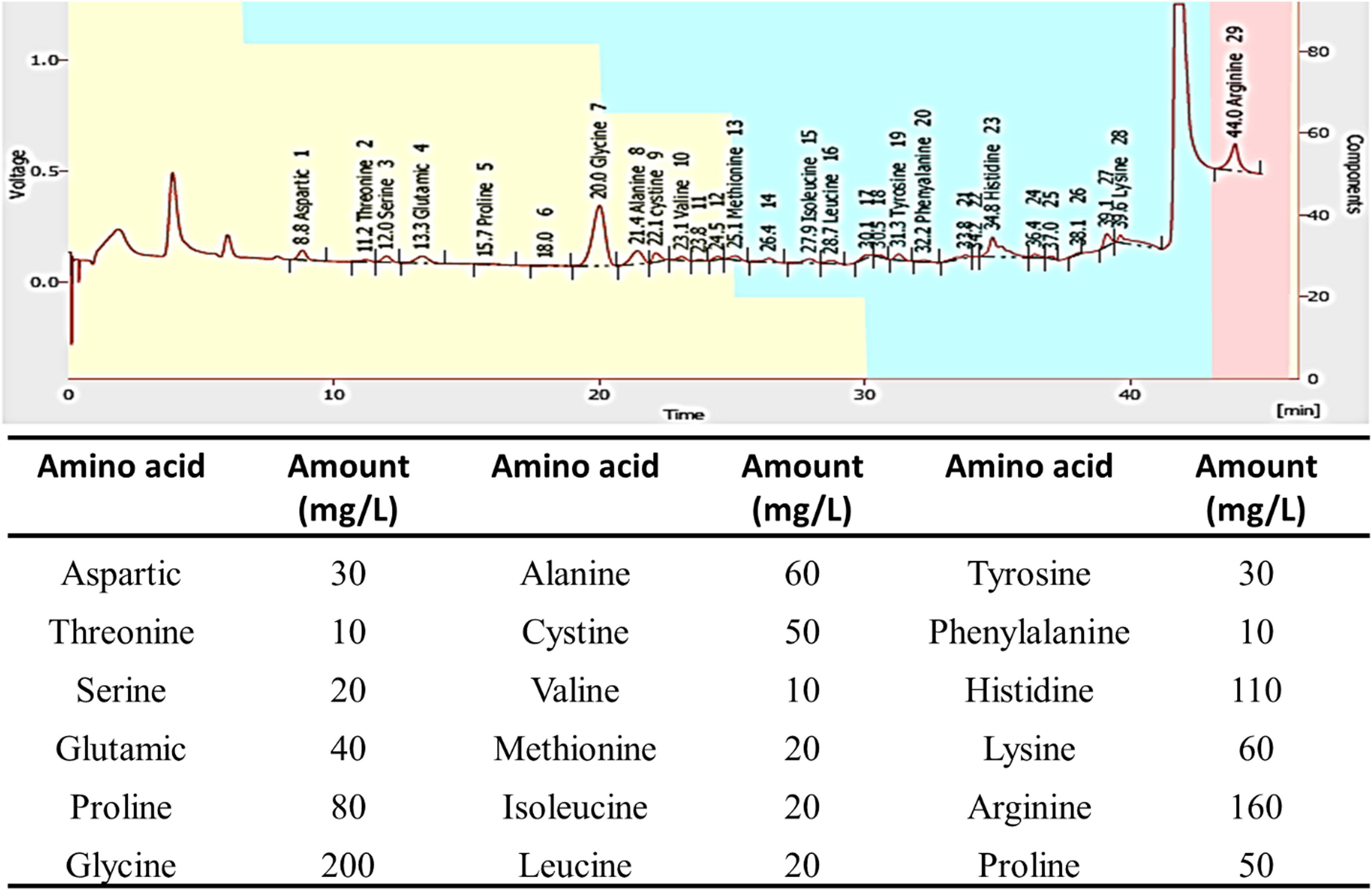

In the current study, the molecular weight of the cellulase enzyme produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7 was 439.0 m/z (Figure 6). Moreover, the amino acid structure of cellulase enzyme obtained from B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7 is represented in (Figure 7). As shown, the cellulase enzyme was composed of 18 amino acids which were aspartic acid followed by threonine, serine, glutamic, glycine, alanine, cystine, valine, methionine, isoleucine, leucine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, histidine, lysine, arginine, and proline. The results showed that the highest values were 200 and 160 mg·L−1 for glycine and arginine, while the lowest value was 10 mg·L−1 for threonine, valine, and phenylalanine, respectively. The structure, function, and overall activity of the cellulase enzyme can be affected by the quantities of amino acids present in the enzyme. The presence of glycine in high amounts provides flexibility to proteins due to its small side chain. Glycine was found in portions of protein that needed flexibility such as turns and loops. Also, glycine contributes to substrate binding, and catalysis, and modulates thermal stability through interaction with the charged chains or peptide structure of proteins [51]. Due to the high amount of basic amino acid, arginine, it participates in ion-pair interactions, protein stabilizing structure, hydrogen bonding, enzyme–substrate interactions, and catalysis. Compared to other amino acids, threonine, valine, and phenylalanine are not very plentiful in the cellulase enzyme. The structure and function of proteins can be altered by the presence of any one of these amino acids. Threonine has an important function in phosphorylation events and can contribute to hydrogen bonding, while valine is a hydrophobic amino acid that can assist in protein stability in nonpolar environments. Phenylalanine is an aromatic amino acid and can be involved in hydrophobic interactions and protein folding [10]. It is worth noting that several factors, such as the organism from which the enzyme is produced, the growth circumstances, and the purification processes, can affect the amounts of individual amino acids in a protein. These amounts may shift between enzyme batches or preparations.

Detection of molecular weight of cellulase enzyme produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7 by TLC analysis.

Amino acids composition and their amount (mg·L−1) for cellulase enzyme produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strain M7.

3.5.2 Effect of temperature, pH, and metals on purified cellulase activity.

The effect of varied temperatures on the activity of purified cellulase enzyme was investigated at the ranges of 30–80°C. As shown, the maximum activity of purified cellulase enzyme was attained at 50°C with a mean value of 73.6 ± 1.1 U·mL−1 (Figure 8a). Meanwhile, the stability and activity of cellulase enzyme decrease at a temperature below and above this value. In a similar study, the cellulase enzyme produced by B. licheniformis C55 was stable, and maximum activity was attained at 50°C [52]. On the other hand, the maximum activity of the cellulase enzyme secreted by B. subtilis CD001 was achieved at 60°C [48]. The obtained findings highlighted the importance of thermostable cellulase enzymes to be incorporated into various applications that needed high temperatures.

Effect of temperature (a) and pH values (b) on the purified cellulase activity produced by B. amyloliquefaciens M7.

Moreover, the pH optimum for purified cellulase enzyme was 8 with the highest cellulase activity of 63.7 ± 0.8 U·mL−1 (Figure 8b). At pH values higher or lower than 8, both the stability and activity of the enzyme decreased. Incompatible with the obtained results, the optimum pH value for the highest cellulase activity was in the acidic range of 4–5.5, the activity and stability of the purified cellulase enzyme beyond this range were low [48]. Also, the obtained results are inconsistent with those reported that the cellulolytic Bacillus spp. showed an optimal pH value for cellulase activity in acidic conditions [26,53]. In the current study, the cellulase enzyme’s apparent sensitivity to changes in pH is demonstrated by the fact that its activity and stability decrease when the pH value is either more or less than 8. This could be attributed to various reasons such as at high or low pH values, the structure of enzymes can be disrupted leading to denaturation or loss of its catalytic activity. Also at extreme pH, hydrogen bonding, the ionic and hydrophobic interactions that provide proper folding and stability of enzymes can be disrupted [54]. Moreover, amino acid residue ionization states in the enzyme’s active site can be drastically altered by a shift in pH to the optimum value. The enzyme’s capacity to bind to the cellulose substrate and catalyze the process efficiently can be hindered by changes in the ionization states of key amino acids [55].

The effect of different metal ions including CaCl2, NaCl, ZnO, CdCl2, CuSO4·5H2O, FeCl3, and HgCl2 with different concentrations (50, 100, 150, and 200 ppm) on the cellulase activity and stability was investigated. Data analysis showed that some metals such as CaCl2, NaCl, and ZnO improved the stability and activity of cellulase enzyme, whereas other metals including CdCl2, CuSO4·5H2O, FeCl3, and HgCl2 inhibited the cellulase activity (Figure 9). As shown, the best CaCl2 concentration for enhancing the stability and activity of cellulase enzyme was 150 ppm with the cellulosic activity of 76.9 ± 0.9 U·mL−1, whereas the optimum concentration of metal ions NaCl and ZnO to obtain maximum cellulase activity was 100 ppm with values of 70.8 ± 0.6 and 64.7 ± 0.8 U·mL−1, respectively. The positive effects of CaCl2, on the stability and activity of cellulase enzyme could be attributed to the Ca2+ ions which have stabilizing effects on the enzyme structure and enhance the proper folding [56]. NaCl is a common salt that has a stabilizing effect on enzymes and provides an environment with the right ionic strength [57]. Moreover, the activity and stability of cellulase enzymes are improved by the presence of zinc ions (Zn2+), which serve as cofactors or structural stabilizers [58]. Other metals including Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, and Hg2+ have a deleterious effect on the stability and activity of cellulase due to their interference with the enzyme’s structures, disrupting important interactions, producing reactive oxygen species that cause oxidative damage, and enzyme inactivation [59]. Overall, the effects of metal ions on enzyme activity and stability might vary depending on a wide range of parameters such as the type of cellulase enzyme, metal concentrations, and contact time. Enzyme–metal ion interactions can occur by site-specific binding or can alter the protein’s three-dimensional structure.

Effect of different metals at varied concentrations on the purified cellulase activity produced by B. amyloliquefaciens M7. (a) Metal at a concentration of 50 ppm, (b) metal at a concentration of 100 ppm, (c) metal at a concentration of 150 ppm, and (d) metal at a concentration of 200 ppm.

3.6 Bio-polishing of cotton fabrics due to treatment with cellulase enzyme

The weight loss in cotton fabrics is a significant outcome and an indicator of successful bio-polishing. The removal of protruding fibers which are known as fibrils from the cotton fabric surface is defined as bio-polishing. The presence of these fibrils causes the pilling of fabric, and thereby decreases the fabric’s smoothness. The enzymes or chemical substances break down these fibrils, and thus remove the excess material resulting in a decrease in the weight of the fabric [15].

Data analysis showed that the loss of weight of the fabric was proportional to enzyme concentration and treatment duration (Table 8). For instance, at cellulase concentration of 0.25%, the weight loss was 1.8 ± 0.1%, 2.6 ± 0.2%, and 3.4 ± 0.4% after 30, 60, and 90 min, respectively. These weight losses were increased by the high amount of treatment. ANOVA showed that the weight loss due to treatment with 1% cellulase enzyme was 3.1 ± 0.1%, 4.2 ± 0.6%, and 4.3 ± 0.1% after incubation times of 30, 60, and 90 min, respectively. Treatment of cotton fabrics with cellulase enzyme has the ability to penetrate the structure of fabrics leading to breakdown of the fibers between the yarn and the fabric’s inner layers, ultimately leading to loss of weight of the fabric [27]. Different chemical substances such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), acetic acid (CH3COOH), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and surfactant were used for polishing cotton fabrics. These substances have disadvantages that retard their applications such as H2O2 at high concentrations or prolonged time exposure can damage the fabrics and reduce their strength and durability [16]. Moreover, H2O2 and NaClO can change the appearance of fabrics causing color fading [60], in addition to their negative impact on humans and the environment. The NaClO can cause skin and eye irritation as well as damage to gastrointestinal and respiratory tissue [61]. Also, EDTA is used to chelate the metal ions forming complexes which have a negative impact on the eco-system if not correctly treated or disposed [62]. The distinct odor that is produced due to using CH3COOH may be undesirable during the polishing process. Therefore, the main target of researchers is using safe and eco-friendly substances for the bleaching of cotton fabrics. Cellulase enzymes originating from different biological entities such as bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi can be used for this purpose. In a similar study, the weight loss (%) of cotton fabric due to treatment with various concentrations (1%, 2%, and 3%) of cellulase enzyme for different times (40, 55, and 70 min) was calculated. The authors reported that the weight loss was proportional to the concentrations of cellulase enzyme [27].

Weight loss percentages of the cotton fabrics treated with cellulase enzyme obtained from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7

| Sl no. | Concentration of cellulase % | Time(min) | Weight loss due to cellulase treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.25 | 30 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 0.25 | 60 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | 0.25 | 90 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 30 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 60 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 90 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| 7 | 1 | 30 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 1 | 60 | 4.2 ± 0.6 |

| 9 | 1 | 90 | 4.3 ± 0.1 |

4 Conclusion

In the current study, the cellulase enzyme was produced using thermotolerant bacterial strain B. amyloliquefaciens M7. The highest production of cellulase from B. amyloliquefaciens was attained after an incubation period of 24 h, at pH 7, with 5 g·L−1 of CMC powder, at an incubation temperature of 35°C, with inoculum size 1% (v/v), and in the presence of peptone as the best nitrogen source with a concentration of 5 g·L−1. Also, highest cellulase production was achieved by optimizing the production conditions using BBD, where this design gave 54 runs and the best run was 13 at the following conditions: pH 7, incubation temperature 35°C, with 1% inoculum size, by using 5 g·L−1 CMC, 5 g·L−1 peptone, and incubation period of 24 h. At these conditions, the maximum cellulase activity was 64.9 U·mL−1. The molecular weight of the obtained cellulase enzyme was 439.0 m/z and contains 18 amino acids in various quantities. Moreover, the highest stability and activity of purified cellulase was accomplished at a temperature of 50°C, pH 8, in the presence of metal ions CaCl2 (150 ppm), NaCl (100 ppm), and ZnO (100 ppm). Whereas the presence of metal ions CdCl2, CuSO4·5H2O, FeCl3, and HgCl2 were considered inhibitors for cellulase activity. The synthesized cellulase enzyme exhibits high activity in the bio-polishing of cotton fabrics through low amount of weight loss after treatment with varied concentrations at different times. The obtained results can be used to improve settings for future fermenter scale-up experiments to get the maximum cellulase enzyme at a large scale. Also, it can be concluded that cellulase is appropriate for industrial usage, particularly in the bio-polishing process, because it lowers the use of toxic chemicals and is economically safe.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt, for the great support in the achievement and publication of this research work. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the support from Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (Grant number IMSIU-RP23027).

-

Author contributions: Amr Fouda, Hossam M. Atta, Mohamed M. Bakry, Salem S. Salem: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review and editing. Mamdouh S. El – Gamal: supervision, project administration, and validation. Khalid S. Alshallash and Mohammed I. Alghonaim: validation, formal analysis, writing – original draft preparation, and funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Liu X, Kokare C. Chapter 11 - Microbial enzymes of use in industry. In: Brahmachari G, editor. Biotechnology of Microbial Enzymes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: Academic Press; 2017. p. 267–98.10.1016/B978-0-12-803725-6.00011-XSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Sanchez S, Demain AL. Chapter 1 - useful microbial enzymes—an introduction. In: Brahmachari G, editor. Biotechnology of Microbial Enzymes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United states: Academic Press; 2017. p. 1–11.10.1016/B978-0-12-803725-6.00001-7Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bakry MM, Salem SS, Atta HM, El-Gamal MS, Fouda A. Xylanase from thermotolerant Bacillus haynesii strain, synthesis, characterization, optimization using Box-Behnken Design, and biobleaching activity. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2022. 10.1007/s13399-022-03043-6.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ortiz A, Sansinenea E. The Industrially important enzymes from bacillus species. In: Islam MT, Rahman M, Pandey P, editors. Bacilli in Agrobiotechnology: Plant Stress Tolerance, Bioremediation, and Bioprospecting. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 89–99.10.1007/978-3-030-85465-2_4Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ortiz A, Sansinenea E. Chemical compounds produced by bacillus sp. factories and their role in nature. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2019;19:373–80. 10.2174/1389557518666180829113612.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ulucay O, Gormez A, Ozic C. Identification, characterization and hydrolase producing performance of thermophilic bacteria: geothermal hot springs in the Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia Regions of Turkey. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2022;115:253–70. 10.1007/s10482-021-01678-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Singhal G, Bhagyawant SS, Srivastava N. Chapter 3 - Cellulases through thermophilic microorganisms: Production, characterization, and applications. In: Tuli DK, Kuila A, editors. Current Status and Future Scope of Microbial Cellulases. United States: Elsevier; 2021. p. 39–57.10.1016/B978-0-12-821882-2.00005-3Search in Google Scholar

[8] Singh R, Kumar M, Mittal A, Mehta PK. Microbial enzymes: industrial progress in 21st century. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:174. 10.1007/s13205-016-0485-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Abada EA, Elbaz RM, Sonbol H, Korany SM. Optimization of cellulase production from Bacillus albus (MN755587) and its involvement in bioethanol production. Pol J Environ Stud. 2021;30:2459–66.10.15244/pjoes/129697Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bhardwaj N, Kumar B, Agrawal K, Verma P. Current perspective on production and applications of microbial cellulases: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2021;8:95. 10.1186/s40643-021-00447-6.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Sharma A, Tewari R, Rana SS, Soni R, Soni SK. Cellulases: Classification, methods of determination and industrial applications. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;179:1346–80. 10.1007/s12010-016-2070-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Premalatha N, Gopal NO, Jose PA, Anandham R, Kwon SW. Optimization of cellulase production by Enhydrobacter sp. ACCA2 and its application in biomass saccharification. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1046. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Bajaj P, Mahajan R. Cellulase and xylanase synergism in industrial biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:8711–24. 10.1007/s00253-019-10146-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ajeje SB, Hu Y, Song G, Peter SB, Afful RG, Sun F, et al. Thermostable cellulases/xylanases from thermophilic and hyperthermophilic microorganisms: current perspective. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:794304. 10.3389/fbioe.2021.794304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Uddin MG. Effects of biopolishing on the quality of cotton fabrics using acid and neutral cellulases. Text Cloth Sustain. 2015;19:1–10. 10.1186/s40689-015-0009-7.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Tang P, Ji B, Sun G. Whiteness improvement of citric acid crosslinked cotton fabrics: H2O2 bleaching under alkaline condition. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;147:139–45. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Korsa G, Konwarh R, Masi C, Ayele A, Haile S. Microbial cellulase production and its potential application for textile industries. Ann Microbiol. 2023;73:13. 10.1186/s13213-023-01715-w.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Mahgoub HAM, Fouda A, Eid AM, Ewais EE-D, Hassan SE-D. Biotechnological application of plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria isolated from halophytic plants to ameliorate salinity tolerance of Vicia faba L. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2021;15:819–43. 10.1007/s11816-021-00716-y.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, et al. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology: Volume 3: The Firmicutes. Vol. 3. Springer New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Lane D. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1991.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Abdel-Hamid MS, Fouda A, El-Ela HKA, El-Ghamry AA, Hassan SE-D. Plant growth-promoting properties of bacterial endophytes isolated from roots of Thymus vulgaris L. and investigate their role as biofertilizers to enhance the essential oil contents. Biomol Concepts. 2021;12:175–96.10.1515/bmc-2021-0019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Islam F, Roy N. Screening, purification and characterization of cellulase from cellulase producing bacteria in molasses. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:445. 10.1186/s13104-018-3558-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54.10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3Search in Google Scholar

[24] Guo H, Hong C, Zhang C, Zheng B, Jiang D, Qin W. Bioflocculants’ production from a cellulase-free xylanase-producing Pseudomonas boreopolis G22 by degrading biomass and its application in cost-effective harvest of microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2018;255:171–9.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.082Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Emami K, Nagy T, Fontes CM, Ferreira LM, Gilbert HJ. Evidence for temporal regulation of the two Pseudomonas cellulosa xylanases belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 11. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4124–33.10.1128/JB.184.15.4124-4133.2002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Anu, Kumar S, Kumar A, Kumar V, Singh B. Optimization of cellulase production by Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis JJBS300 and biocatalytic potential in saccharification of alkaline-pretreated rice straw. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;51:697–704. 10.1080/10826068.2020.1852419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Sankarraj N, Nallathambi G. Enzymatic biopolishing of cotton fabric with free/immobilized cellulase. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;191:95–102. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.02.067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Abdel-Aziz S, Ibrahim A, Guirgis A, Dawwam G, Elsababty Z. Isolation and screening of cellulase producing bacteria isolated from soil. Benha J Appl Sci. 2021;6:207–13.10.21608/bjas.2021.188849Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lugani Y, Singla R, Sooch BS. Optimization of cellulase production from newly isolated Bacillus sp. Y3. J Bioprocess Biotechniques. 2015;5(11):1000264.10.4172/2155-9821.1000264Search in Google Scholar

[30] El-Sersawy MM, Hassan SE, El-Ghamry AA, El-Gwad AMA, Fouda A. Implication of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria of Bacillus spp as biocontrol agents against wilt disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht in Vicia faba L. Biomol Concepts. 2021;12:197–214. 10.1515/bmc-2021-0020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Dai J, Dong A, Xiong G, Liu Y, Hossain MS, Liu S, et al. Production of highly active extracellular amylase and cellulase from bacillus subtilis ZIM3 and a recombinant strain with a potential application in tobacco fermentation. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1539. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01539.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Lee Y-J, Kim B-K, Lee B-H, Jo K-I, Lee N-K, Chung C-H, et al. Purification and characterization of cellulase produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens DL-3 utilizing rice hull. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:378–86. 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.12.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ye M, Sun L, Yang R, Wang Z, Qi K. The optimization of fermentation conditions for producing cellulase of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and its application to goose feed. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:171012. 10.1098/rsos.171012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Pandey A. Solid-state fermentation. Biochem Eng J. 2003;13:81–4.10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00121-3Search in Google Scholar

[35] Aslam S, Hussain A, Qazi JI. Production of cellulase by bacillus amyloliquefaciens-ASK11 under high chromium stress. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2019;10:53–61. 10.1007/s12649-017-0046-3.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Yang V, Zhuang Z, Elegir G, Jeffries T. Alkaline-active xylanase produced by an alkaliphilic Bacillus sp isolated from kraft pulp. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:434–41.10.1007/BF01569971Search in Google Scholar

[37] Heck JX, Hertz PF, Ayub MA. Cellulase and xylanase productions by isolated Amazon Bacillus strains using soybean industrial residue based solid-state cultivation. Braz J Microbiol. 2002;33:213–8.10.1590/S1517-83822002000300005Search in Google Scholar

[38] Abdel-Maksoud G, Abdel-Nasser M, Sultan MH, Eid AM, Alotaibi SH, Hassan SE, et al. Fungal biodeterioration of a historical manuscript dating back to the 14th Century: An insight into various fungal strains and their enzymatic activities. Life. 2022;12:1821. 10.3390/life12111821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Ismail MA, Amin MA, Eid AM, Hassan SE, Mahgoub HAM, Lashin I, et al. Comparative study between exogenously applied plant growth hormones versus metabolites of microbial endophytes as plant growth-promoting for phaseolus vulgaris L. Cells. 2021;10(5):1059. 10.3390/cells10051059.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Nandimath A, Kharat K, Gupta S, Kharat A. Optimization of cellulase production for Bacillus sp. and Pseudomonas sp. soil isolates. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2016;10(13):410–9.10.5897/AJMR2016.7954Search in Google Scholar

[41] Niyonzima FN, Veena SM, More SS. Industrial production and optimization of microbial enzymes. In: Arora NK, Mishra J, Mishra V, editors. Microbial Enzymes: Roles and Applications in Industries. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020. p. 115–35.10.1007/978-981-15-1710-5_5Search in Google Scholar

[42] Hsieh CW, Cannella D, Jørgensen H, Felby C, Thygesen LG. Cellulase inhibition by high concentrations of monosaccharides. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:3800–5. 10.1021/jf5012962.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Abdel-Rahman M, Abdel-Shakour E, El-Din M, Refaat B, Ewais E, Alrefaey H. A novel promising thermotolerant cellulase-producing bacillus licheniformis 1-1v strain suitable for composting of rice straw. Int J Adv Res. 2015;3:413–23.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Davami F, Eghbalpour F, Nematollahi L, Barkhordari F, Mahboudi F. Effects of peptone supplementation in different culture media on growth, metabolic pathway and productivity of CHO DG44 Cells; a new insight into amino acid profiles. Iran Biomed J. 2015;19:194–205. 10.7508/ibj.2015.04.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Abou –Taleb K, Mashhoor W, Nasr S, Sharaf M. Nutritional and environmental factors affecting cellulases activity produced by high potent cellulolytic Bacilli. J Agric Chem Biotechnol. 2015;6:29–39. 10.21608/jacb.2015.44030.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Kokkonen P, Beier A, Mazurenko S, Damborsky J, Bednar D, Prokop Z. Substrate inhibition by the blockage of product release and its control by tunnel engineering. RSC Chem Biol. 2021;2:645–55. 10.1039/D0CB00171F.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Özbek Yazıcı S, Özmen I. Optimization for coproduction of protease and cellulase from Bacillus subtilis M-11 by the Box–Behnken design and their detergent compatibility. Braz J Chem Eng. 2020;37:49–59. 10.1007/s43153-020-00025-x.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Malik WA, Javed S. Biochemical characterization of cellulase from Bacillus subtilis strain and its effect on digestibility and structural modifications of lignocellulose rich biomass. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:800265. 10.3389/fbioe.2021.800265.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Wingfield P. Protein precipitation using ammonium sulfate. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2001;Appendix 3, Appendix 3F. 10.1002/0471140864.psa03fs13.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Sinha R, Khare SK. Protective role of salt in catalysis and maintaining structure of halophilic proteins against denaturation. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:165. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00165.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Platts L, Falconer RJ. Controlling protein stability: Mechanisms revealed using formulations of arginine, glycine and guanidinium HCl with three globular proteins. Int J Pharmaceutics. 2015;486:131–5. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.03.051.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Listyaningrum NP, Sutrisno A, Wardani AK. Characterization of thermostable cellulase produced by Bacillus strains isolated from solid waste of carrageenan. IOP Conf Series: Earth Environ Sci. 2018;131:012043. 10.1088/1755-1315/131/1/012043.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Li F, Xie Y, Gao X, Shan M, Sun C, Niu YD, et al. Screening of cellulose degradation bacteria from Min pigs and optimization of its cellulase production. Electron J Biotechnol. 2020;48:29–35.10.1016/j.ejbt.2020.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[54] Wohlert M, Benselfelt T, Wågberg L, Furó I, Berglund LA, Wohlert J. Cellulose and the role of hydrogen bonds: not in charge of everything. Cellulose. 2022;29:1–23. 10.1007/s10570-021-04325-4.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Robinson PK. Enzymes: principles and biotechnological applications. Essays Biochem. 2015;59:1–41. 10.1042/bse0590001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Liao SM, Liang G, Zhu J, Lu B, Peng LX, Wang QY, et al. Influence of Calcium Ions on the Thermal Characteristics of α-amylase from Thermophilic Anoxybacillus sp. GXS-BL. Protein Peptide Lett. 2019;26:148–57. 10.2174/0929866526666190116162958.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Hani FM, Cole AE, Altman E. The ability of salts to stabilize proteins in vivo or intracellularly correlates with the Hofmeister series of ions. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;10:23–31.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Thompson MW. Regulation of zinc-dependent enzymes by metal carrier proteins. BioMetals. 2022;35:187–213. 10.1007/s10534-022-00373-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Liu X, Wu M, Li C, Yu P, Feng S, Li Y, et al. Interaction structure and affinity of zwitterionic amino acids with important metal cations (Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+ and Zn2+) in aqueous solution: a theoretical study. Molecules. 2022;27(8):2407. 10.3390/molecules27082407.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Fu S, Farrell MJ, Ankeny MA, Turner ET, Rizk V. Hydrogen peroxide bleaching of cationized cotton fabric. AATCC J Res. 2019;6:21–9. 10.14504/ajr.6.5.4.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Slaughter RJ, Watts M, Vale JA, Grieve JR, Schep LJ. The clinical toxicology of sodium hypochlorite. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia, Pa). 2019;57:303–11. 10.1080/15563650.2018.1543889.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Zhang K, Dai Z, Zhang W, Gao Q, Dai Y, Xia F, et al. EDTA-based adsorbents for the removal of metal ions in wastewater. Coord Chem Rev. 2021;434:213809. 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213809.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter