Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

-

A. M. Castorena-Sánchez

Abstract

Terpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol, are phenols that exhibit antioxidant and antimicrobial activities but are unstable in the presence of light or oxygen. Layered hydroxide salts are laminar compounds that can host molecules in their interlaminar space, protecting them from degradation and delivering bioactive molecules in a sustained manner. In the present study, hybrids composed of brucite, thymol, or carvacrol were synthesized by precipitation and anion-exchange process. The structure was confirmed by X-ray diffraction, and characteristic hexagonal morphology was verified by scanning electronic microscopy. The antibacterial activity of hybrids was evaluated against foodborne pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella Enteritidis, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus), obtaining an inhibition of 80% for both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria, while inhibition of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) was 65% for carvacrol and 93% for thymol. Finally, the exposition of hybrids to Artemia salina proved to be non-toxic up to 200 mg·mL−1. The results suggest that these hybrids can control pathogen growth and exhibit antioxidant activity without threatening consumers’ health in the case of consumption, which helps develop novel and safe products applied in the food industry.

1 Introduction

Foodborne illnesses constitute a significant health problem worldwide; in 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that every year in the Americas Region, 77 million people were sick, and more than 9,000 died from foodborne illness [1]. Among the foodborne disease-causing organisms identified, Campylobacter, pathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia enterocolitica are the most common foodborne pathogens associated with foods such as red meat, fish and shellfish, bivalves, dairy products, poultry, fruits, and vegetables [2,3,4]. For this reason, in the food industry, a set of chemical and physical treatments are carried out to eliminate, reduce, or control the presence of pathogenic microorganisms in food. The control of etiological agents by applying physical conservation methods includes heat treatments and ultraviolet radiation, ionizing radiation, high pressure, and pulsed electric fields [5]. Chemical methods include the use of antimicrobial substances that inhibit microbial growth by acting on specific targets such as the cell membrane, enzymes, and the genetic material of bacteria [6].

An example of chemical methods is the use of bioactive compounds such as carvacrol and thymol, which are monoterpenes found in the essential oils extracted from plants belonging to the Lamiaceae family of the genera Origanum, Thymus, Coridothymus, Thymbra, Satureja, and Lippia. Both substances inhibit the proliferation of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria since they can damage their outer membranes. In addition, given the hydrophobic nature of thymol and carvacrol, they can integrate into bacterial cell membranes, causing disruption and alteration of their functionality, which leads to increased permeability of the cytoplasmic membrane [6,7,8,9,10].

Simple layered hydroxides (LHSs) are synthetic brucite-like structures that comprise hydroxylated layers with positive electrostatic charges stabilized by anions between layers, joined together by van der Waals forces [11]. Furthermore, they are promising materials owing to their properties like chemical and thermal stability, the ability to intercalate different types of anions (inorganic, organic, and biomolecules), sustained delivery of intercalated anions, and high biocompatibility [12]. Hybrid materials have proved to combine the properties of the LHS and the counter anion, sometimes a biomolecule, improving the solubility of hydrophobic compounds and increasing the systems in which they can be incorporated [12].

In this study, layered magnesium hydroxide compounds with thymol (LHS-Mg+T) and carvacrol (LHS-Mg+C) were synthesized through precipitation and ion exchange. X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy were employed to elucidate the composition and structure of the nanohydroxide; antioxidant activity was determined using the 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) technique, and antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the well diffusion technique, microdilution, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) against foodborne pathogens E. coli, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella Enteritidis. Finally, the toxicity of hybrids was evaluated in the Artemia salina model.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The magnesium LHS compounds with thymol (LHS-Mg+T) and carvacrol (LHS-Mg+C) were synthesized using MgCl2 hexahydrate (FAGA LAB, Mexico), fructose 1% (Food Technologies Trading Co., Mexico), NaOH 0.1 M (Golden Bell Co., Mexico), thymol, and carvacrol (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., USA). Distilled water was used during the experimental period.

2.2 Synthesis of nanohydroxides and hybrids

The synthesis of magnesium nanohydroxides by precipitation (LHS-Mg) followed the methodology described by Wang et al. [13] with some modifications. Briefly, 0.04 g·mL−1 of MgCl2 hexahydrate and 1% fructose as a reducing agent were dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water under constant stirring (IKA, Wilmington, USA) until the reagents were completely dissolved. Then, 0.1 M NaOH was added dropwise until a final pH of 11 and a white precipitate formed, allowing it to stabilize for 24 h at room temperature with constant stirring.

Subsequently, two washes with distilled water were performed by centrifugation (LZ-1580R, LaboGene, Yuseon-gu, South Korea) at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 25°C. Finally, the precipitate was dried in a forced convection oven (FE-291, Felisa, Guadalajara, Mexico) at 40°C for 48 h and reserved until use.

To prepare the hybrid material with thymol and carvacrol, 50 mL of a solution of each compound was prepared at a concentration of 5 mg·mL−1; then, 500 mg of LHS-Mg was added with constant stirring for 2 h. For the recovery of the precipitate, two washes were carried out under the conditions previously mentioned. Finally, the precipitate was dried in a forced convection oven at 40°C for 48 h and reserved until use [14].

2.3 Characterization

X-ray diffractograms were recorded in an Empyrean X-ray diffractor (Panalytical, Malvern, UK) using CuKα radiation at a 2θ angle between 5° and 70°, with a step of 0.02 and a collection time of 30 s. The analysis of the surface morphology of the nanohydroxides was carried out by SEM. The dried materials were placed in a sample holder overlaid with gold for 20 s; then, the micrographs were taken on a FE-SEM microscope (MIRA 3 LMU, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. FTIR spectra were recorded in a spectrophotometer Cary 630 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) in absorbance mode in a wavenumber interval of 4,000–400 cm−1, with 32 scans and 4 cm−1 of resolution [14].

2.4 Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of hybrids was evaluated with the inhibition of the ABTS radical. The methodology reported by Li et al. [15] with modifications was tested. Briefly, 280 μL of an ABTS solution previously adjusted to an absorbance of 0.7 at 750 nm was added to a 96-well microplate with 20 μL of solutions of the materials in ethanol (1:1 m/v). The plate was incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, absorbance was measured in a 96-well microplate reader (BioRad iMarkTM, CA, USA) at 750 nm; the percentage of inhibition was calculated with Eq. 1. Ethanol was used as negative control, while positive control was a solution of Trolox (50–400 μg·mL−1) used for comparison:

where A 0 is the absorbance of the control and A 1 is the absorbance of the sample.

2.5 Antimicrobial evaluation

Simple bioactive compounds (thymol and carvacrol) and hybrid materials were evaluated against four bacterial strains: E. coli ATCC 8739, S. aureus ATCC 25923, L. monocytogenes (isolated from fresh cheese), and Salmonella Enteritidis from clinical cases. Bacteria were cultivated in Müller–Hinton broth (MHB) (DIFCO, USA) and incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. Then, the concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 cells·mL−1 with an optical density measured at 600 nm in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (OPTIZEN, 131 Mecasys, South Korea).

Plate microdilution was performed in a 96-well microplate to determine the antimicrobial effect of LHS-Mg, bioactive compounds, and hybrids. Briefly, 160 μL of MHB was inoculated with 20 μL of 1 × 108 CFU·mL−1 of each strain, and then 20 μL of the bioactive compound, LHS, or hybrid at a concentration of 100 mg·mL−1 were added. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C; PBS was used as a negative control, while 0.1% gentamicin (m/V) was a positive control. After incubation, plates were read at 600 nm in a BioRad microplate reader (BioRad, iMarkTM, CA, USA), and the percentage of inhibition was calculated with Eq. 2:

where A is the absorbance of the control and B is the absorbance of the treated compounds.

As for the well diffusion method, 100 μL (1 × 108 CFU·mL−1) of the strains were inoculated by surface extension on Müller–Hinton agar (MHA); it was allowed to dry, and perforations were made with sterile tips (10 mm in diameter). Then, 60 μL of each bioactive compound and each hybrid material were placed. Finally, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and the inhibition halos were measured. Positive and negative controls were the same as microdilution.

The MIC and MBC values were determined based on the methodology described by Gonçalves et al. [16] and the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute [17]. The concentrations of the hybrid materials, thymol, and carvacrol, were determined using the methodology of Vasconcelos et al. [18] in 96-well microplates, with some modifications. Each well contained 160 μL of MHB, 20 μL of the inoculum (1 × 108 CFU·mL−1), and 20 μL of standard or hybrid material with a 50–500 mg·mL−1 concentration. The microplates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Then, 30 μL of a 0.1 mg·mL−1 resazurin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 75 min at 37°C to observe the color change. Cell viability can be elucidated according to the color change of resazurin from blue to pink (resorufin). Serial dilutions were made for each well, and 100 μL was transferred to MHA with surface extension. After incubation with the same conditions previously used, colonies were counted. MIC was determined as the minimum concentration in which the inhibition was observed, while MBC was selected as the concentration where growth was absent.

2.6 Brine shrimp bioassay

In order to determine if hybrids exhibit cytotoxic effects, an evaluation with Artemia salina was conducted [19]. A. salina eggs were hatched in artificial seawater (34 g NaCl·L−1) at 28°C with constant light and aeration for 24 h. Then, 10 nauplii were transferred to 6-well microplate with 5 mL of artificial seawater and 7 mm Whatman No. 4 filter papers wetted with LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, or LHS-Mg+C solutions at different concentrations (50–200 mg·mL−1). Hexane was used as the positive control. After 24 h, dead nauplii were counted, and the percentage of mortality was determined using Eq. 3:

where N m is the number of dead nauplii and N T is the number of total nauplii at the beginning of the test. Toxicity was specified according to Clarkson criteria [20], and lethal dose (LD50) was estimated with the PROBIT method [21] classifying the materials as non-toxic if LD50 > 1,000 μg·mL−1, slightly toxic when 500 μg·mL−1 < LD50 < 1,000 μg·mL−1, moderately toxic if 100 μg·mL−1 < LD50 < 500 μg·mL−1, and extremely toxic when LD50 < 100 μg·mL−1.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate (±SD), and the results were analyzed using ANOVA, followed by the Tukey HSD test with a p-value ≤ 0.05 using the Statgraphics Centurion (Statgraphics Centurion XVIII, version 18.1.12, USA) statistical program. In addition, illustrations were created using Origin 2022 (OriginLab Inc., USA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD analysis

Figure 1 depicts the XRD diffractogram for magnesium-layered hydroxide (LHS-Mg), thymol (LHS-Mg+T), and carvacrol (LHS-Mg+C) hybrids. All diffractogram peaks match the characteristics of brucite (ICDD Card No. 44-1482), demonstrating that brucite was obtained during the synthesis of LHS and hybrids [13]. Interestingly, the LHS-Mg+T diffractogram exhibits a first signal at 7.93° in the 2θ angle, which suggests a possible partial intercalation of thymol in the interlaminar space of the LHS due to the expansion of the space between layers according to Bragg’s law [14]. Furthermore, the lower intensity peaks that appear in the range from 15° to 30° can be associated with diffraction peaks characteristic of thymol [22]. Both hybrids showed wider signals at each diffraction angle compared to LHS-Mg, indicating a reduction of particle crystallinity, possibly due to interactions of bioactive compounds on the surface of pristine compounds [23]. Also, the widening of the signal indicated as (001) is because of the substitution of water and OH− in the interlaminar space for the biomolecules from the layered compound to the respective hybrids [24].

XRD diffractograms of LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, and LHS-Mg+C.

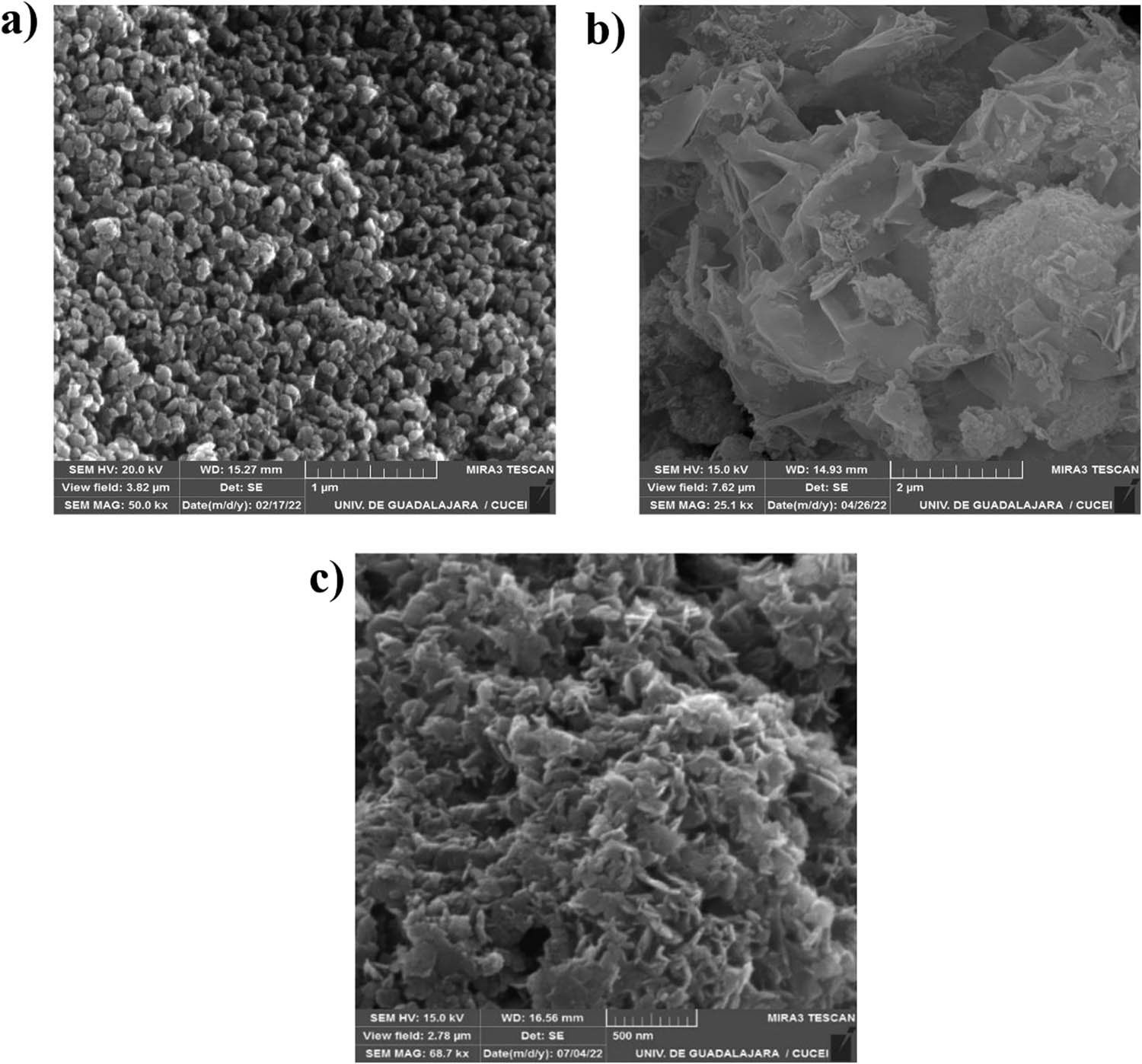

3.2 SEM

Figure 2 depicts SEM micrography of LHS-Mg and hybrids. The characteristic hexagonal structure found in layered compounds was obtained for LHS-Mg (Figure 2a); small granules observed on the surface can also be attributed to the reducing agent. Reducing agents are added since it has been demonstrated that they control the growth rate of crystals, favoring the interaction between the crystal interphase and solvent [25]. Figure 2b shows an abundant formation of lamellar structures approximately 0.045 µm thick. In contrast, LHS-Mg+T and LHS-Mg+C produced larger size crystals, modifying their crystallinity as demonstrated by DRX analysis. Both terpenes formed a web-type structure around the brucite, similar to a coral (Figure 2c), which can result from the exposition of hydrophobic groups present in thymol and carvacrol molecules [26]. It is worth mentioning that substituting structural cations with other ions with less valence produces a charge deficiency on layers, which can be neutralized with adsorbed species located in the interlayer space [27]. When substituting anions in a layered compound, crystals grow in larger shapeless aggregates, as can be seen using positive ions such as copper [24].

SEM micrographs of (a) LHS-Mg, (b) LHS-Mg+T, and (c) LHS-Mg+C.

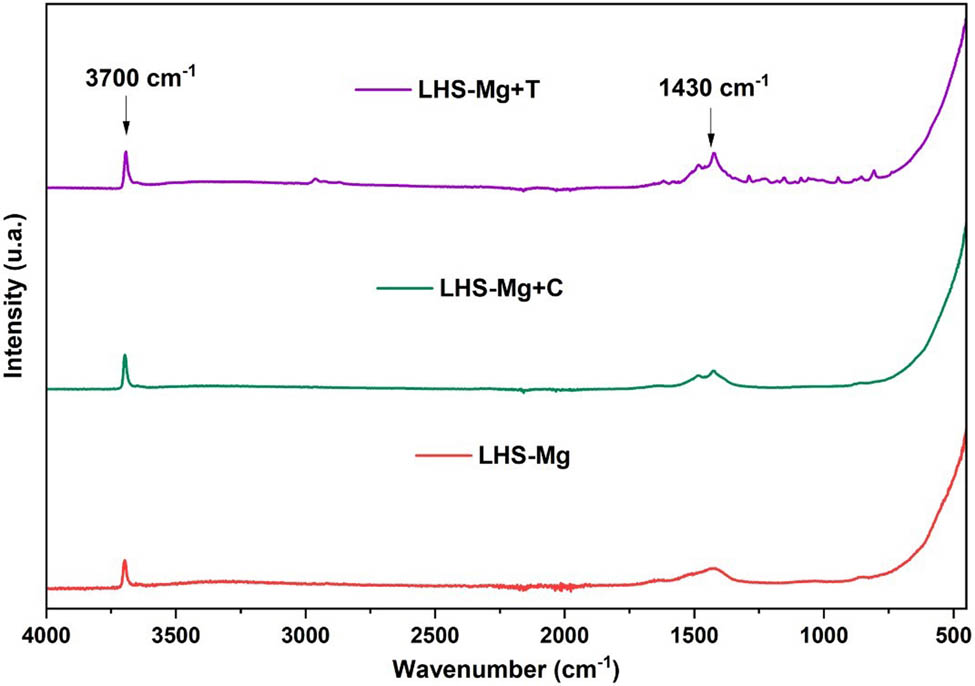

3.3 FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra of brucite and hybrids are depicted in Figure 3. The signal around 3,700 cm−1 is associated with –OH vibrations, typical of LHS structures. In contrast, signals below 1,000 cm−1 can be attributed to metal bonds, confirming the formation of the brucite in the three materials. In the case of LHS-Mg+T, a small peak can be observed at around 2,900 cm−1, a signal corresponding to a stretch of C–H bonds of the organic compound. Also, at around 1,430 cm−1, thymol and carvacrol hybrids exhibit an arm compared to brucite alone, corresponding to C–H bonds [28,29].

FT-IR spectra for LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, and LHS-Mg+C.

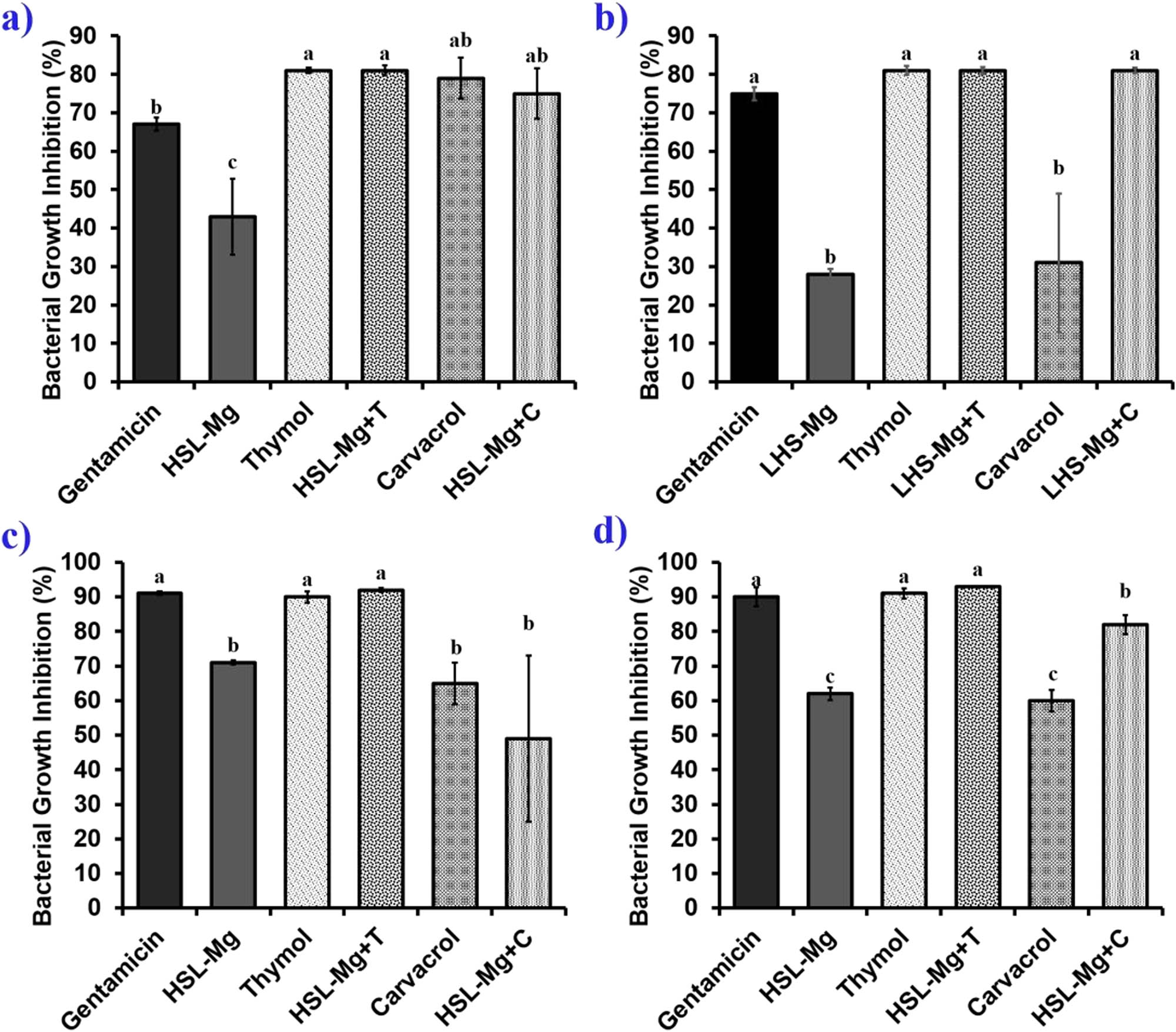

3.4 Antimicrobial evaluation

The antibacterial activity of LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, LHS-Mg+C, thymol, and carvacrol by microdilution was tested against four foodborne pathogens. Figure 4 depicts the percentage of inhibition for each bacterial strain. The interaction of bioactive compounds with brucite is confirmed due to the increasing rate of inhibition of hybrids compared to the LHS alone. E. coli (Figure 4a) exhibited higher values of inhibition in comparison with gentamicin in both cases, while for S. aureus (Figure 4b) and Salmonella Enteritidis (Figure 4d), the increase exhibited for carvacrol in combination with brucite was significantly higher than when bioactive or brucite was used. However, the growth inhibition of L. monocytogenes (Figure 4c), although not significant, had a decrease in inhibition percentage. Similar results for E. coli and S. aureus were found by Clavier et al. [24] when exposing the bacterial strains to brucite nanoparticle solution at a concentration of 1 mg·mL−1.

Bacterial growth inhibition of magnesium LHS, thymol, carvacrol, and hybrids. (a) E. coli, (b) S. aureus, (c) L. monocytogenes, and (d) Salmonella Enteritidis. Different letters indicate statistical differences (p < 0.05).

These results are in accordance with the ones obtained in the well diffusion test (Table 1), where inhibition halos increased for E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella Enteritidis. Carvacrol and LHS-Mg+C produced the same diameter with all strains, except S. aureus. However, in the case of L. monocytogenes, the diameter was higher for thymol and LHS-Mg+T than for LHS-Mg.

Diameters of inhibition halos for bioactive compounds and hybrids

| Material | Inhibition halo (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. aureus | L. monocytogenes | Salmonella Enteritidis | |

| Gentamicin | 17 ± 1.0c | 20 ± 2.5c | 20 ± 0.0b | 23 ± 1.2b |

| LHS-Mg | 15 ± 1.2cd | 14 ± 0.6d | 16 ± 2.0c | 12 ± 2.0c |

| Thymol | 23 ± 1.1b | 21 ± 1.2c | 25 ± 2.3a | 35 ± 5.0a |

| LHS-Mg+T | 49 ± 6.4a | 46 ± 1.1a | 27 ± 4.2a | 47 ± 9.9a |

| Carvacrol | 13 ± 1.0d | 15 ± 8.1cd | 14 ± 2.0cd | 15 ± 1.2c |

| LHS-Mg+C | 13 ± 1.2d | 35 ± 6.1b | 13 ± 1.2d | 15 ± 1.2c |

Results are mean ± SD from three replicates.

Different uppercase letters indicate statistical difference (p < 0.05).

MIC values were not detected in the range of concentrations evaluated for bioactive compounds and hybrids, as shown in Table 2. MBC values were around 200 mg·mL−1 for bioactive compounds alone and hybrids but layered magnesium hydroxide reached values above 300 mg·mL−1. At the same time, brucite exhibited values from 100 to 300 mg·mL−1 for some bacterial strains.

MIC and MBC for bioactive compounds and hybrids

| Material | Concentration (mg·mL−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. aureus | L. monocytogenes | Salmonella Enteritidis | |||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| LHS-Mg | 100 | 300 | 300 | 500 | <50 | 300 | 250 | 500 |

| Thymol | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 |

| LHS-Mg+T | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | >300 | <50 | 200 |

| Carvacrol | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 |

| LHS-Mg+C | <50 | 200 | <50 | 200 | <50 | >300 | <50 | >300 |

Results are mean ± SD from three replicates.

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration.

MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration.

It has been proposed that magnesium nanoparticles can inhibit bacterial growth due to OH− radicals interacting with the cell membrane, increasing its pH and provoking cell death [30]. Depending on whether the bacteria are Gram-positive or -negative, this mechanism may vary since, in the latter, the presence of lipopolysaccharides may limit the diffusion of hydrophobic compounds [31]. Other mechanisms through which layered compounds exhibit antibacterial activity are due to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide ions, or hydrogen peroxide, which can oxidize the lipid membrane and favor cellular content leakage, altering metabolic processes and provoking cell death [32].

The size and surface charge of nanoparticles also play a crucial role in antibacterial activity. Magnesium nanosheets may interact with bacterial cells attaching to the cell membrane and then integrating inside the cell, destroying and inactivating the cell wall [33]. Bioactive compounds like thymol and carvacrol interact with the cell membrane, generating pores and leading to cell content leakage [34]. Modifying the surface of layered compounds has been demonstrated to increase the antimicrobial activity of these materials. It has been proved that functionalizing magnesium LHSs with poly (sodium 4-styrene sulfonate) or poly(allylamine hydrochloride) increases the inhibition of microorganisms like E. coli or S. cerevisiae since the combination of materials improves the attachment to cell walls, promoting its disruption and, in consequence, cell death [35,36]. Brucite structure has been used as a host for the anti-tuberculosis antibiotic pyrazinamide (PZA) and tested against E. coli, S. aureus, and M. tuberculosis, where activity was upgraded compared to independent hydroxide salt or PZA [37]. The combination of brucite and bioactive compounds may act, generating holes in the membrane and favoring the introduction of magnesium ions and OH− groups, which can explain the elevation of inhibition percentage and diameter of the inhibition halo.

3.5 Antioxidant activity

Table 3 shows the percentage of inhibition of the ABTS radical for LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, LHS-Mg+C, thymol, and carvacrol. ABTS inhibition for carvacrol increased when the hybrid was evaluated from 16 to 65%, while thymol activity decreased from 93 to 80%. Comparing these results with the antioxidant activity of Trolox (data not shown), it can be seen that LHS-Mg and LHS-Mg+C activity exhibits the same percentage of ABTS radical inhibition of 250 μg·mL−1, carvacrol as 40 μg·mL−1, LHS-Mg+T for 300 μg·mL−1, and thymol as 400 μg·mL−1 of Trolox. The ABTS inhibition of thymol intercalated in the layered zinc hydroxide has been previously evaluated, demonstrating that hybrids exhibit slightly higher inhibition [14], in which thymol was mainly on the surface of the nanoparticle. In this work, a fraction of thymol was intercalated inside the brucite structure as suggested by XRD, which affects the activity of this radical inhibition in the concentration evaluated. Conversely, as shown by the SEM and XRD results, carvacrol is located on the surface. Its activity was increased in combination with brucite, probably due to ROS production [8].

Antioxidant activities of bioactive compounds and hybrids

| Material | ABTS inhibition (%) | Trolox equivalent (μg·mL−1)* |

|---|---|---|

| LHS-Mg | 60 ± 7.5 | 250 |

| Thymol | 93 ± 0.1 | 400 |

| LHS-Mg+T | 80 ± 2.0 | 300 |

| Carvacrol | 16 ± 5.5 | 40 |

| LHS-Mg+C | 65 ± 2.1 | 250 |

Results are mean ± SD from three replicates.

*Data obtained from the standard curve (not shown).

3.6 Artemia salina bioassay

The nauplii of Artemia salina were mixed with LHS-Mg, LHS-Mg+T, and LHS-Mg+C in the concentration range from 25 to 200 mg·mL−1. After 24 h, results demonstrated that all materials were non-toxic according to the Clarkson scale [20] since the mortality percentage was up to 10% (Table 4). The LD50 calculated with the PROBIT test indicated that a high dose of the materials is required to cause multiple nauplii deaths, corroborating that these materials are nontoxic (Table 4). Thymol and carvacrol are molecules that have OH− radicals in their structure; at high concentrations, these radicals may exhibit a lethal effect on Artemia salina nauplii and even on human cells [38], but the bioavailability of these bioactive compounds can be controlled since they interact with the nanohydroxide structure. In the case of magnesium nanoparticles obtained from different precursors, it has been demonstrated that they are safe to be in contact with human cells at concentrations of 1,000 μg·mL−1 [39], as nitrate is the counter ion that exhibits a slight cytotoxic effect for the pristine LHS [37]. These results suggest that the synthesized and evaluated hybrids are safe for their application in food matrices, reducing the growth of pathogens and exhibiting antioxidant activity.

Cytotoxic activities and LD50 values estimated using the PROBIT test of hybrids

| Material | Mortality (%) | PROBIT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg·mL−1) | LD50 (mg·mL−1) | ||||

| 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | ||

| Hexane | 70 ± 0.0 | 70 ± 0.0 | 70 ± 0.0 | 70 ± 0.0 | |

| LHS-Mg | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 10 ± 14 | 19 |

| LHS-Mg+T | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 7.1 | 165 |

| LHS-Mg+C | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 10 ± 14 | 1,008 |

Results are mean ± SD from three replicates.

4 Conclusions

Hybrids of magnesium-LHS with thymol or carvacrol were obtained, whose structures were confirmed with solid-state techniques. Antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogens suggests that these hybrids can be incorporated in food matrices or applied as disinfectants to control the proliferation of microorganisms since they proved innocuous on Artemia salina nauplii. The results obtained from this research open a new path to introduce layered magnesium compounds to stabilize and potentiate the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of terpenes such as thymol and carvacrol, keeping in mind that the safety of consumers is a priority in food research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Council of Humanities, Science and Technology CONAHCyT (Grant number 1100443) and the University of Guadalajara.

-

Author contributions: Castorena-Sánchez: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing-original draft. Velázquez-Carriles: methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, and investigation. López-Álvarez: resources and data curation. Serrano-Niño: resources and supervision. Cavazos-Garduño: data curation and conceptualization. Garay-Martínez: data curation and formal analysis. Silva-Jara: project administration, resources, investigation, visualization, writing-original draft, formal analysis, and software.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Administración Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y Tecnología Médica (ANMAT). Enfermedades Transmitidas por Alimentos. 2021. Retrieved from http://www.anmat.gov.ar/alimentos/eta.pdfAccessed 12, November 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[2] World Health Organization (WHO). Food safety. 2020 Apr. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safetyAccessed 18, November 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Foodborne Germs and Illnesses. 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/es/foodborne-germs-es.htmlAccessed 12, November 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Soto-Varela Z, Pérez-Lavalle L, Estrada-Alvarado D. Bacterias causantes de enfermedades transmitidas por alimentos: Una mirada en Colombia. Sal Uninor. 2016;32(1):105–22. 10.14482/sun.32.1.8598.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Abdelhamid GA, El-Dougdoug KN. Controlling foodborne pathogens with natural antimicrobials by biological control and antivirulence strategies. Heliyon. 2020;6(9):2–7. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Pisoschi AM, Pop A, Georgescu C, Turcuş V, Kinga ON, Mathe E. An overview of natural antimicrobials role in food. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;143(1):922–35. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.095.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Kachur K, Suntres Z. The antibacterial properties of phenolic isomers, carvacrol and thymol. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;60(18):3042–53. 10.1080/10408398.2019.1675585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Rúa J, Del Valle P, De Arriaga D, Fernández-Álvarez L, García-Armesto MR. Combination of carvacrol and thymol: Antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and antioxidant activity. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019;16(9):622–9. 10.1089/fpd.2018.2594.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Sivaranjani D, Saranraj P, Manigandan M, Amala K. Antimicrobial activity of Plectranthus amboinicus solvent extracts against Human Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019;9(3):36–9. 10.22270/jddt.v9i3.2604.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Soumya E, Saad KI, Hassan L, Ghinzlane Z, Hind M, Adnane R. Carvacrol and thymol components inhibiting Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence and biofilm formation. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(20):3229–32. 10.5897/AJMR11.275.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Martínez RD, Carbajal GG. Hidróxidos dobles laminares: arcillas sintéticas con aplicaciones en la nanotecnología. Av en Química. 2012;7(1):87–99.10.53766/AVANQUIM/2012.07.01.01Search in Google Scholar

[12] Mishra G, Dash B, Pandey S. Layered double hydroxides: A brief review from fundamentals to application as evolving biomaterials. Appl Clay Sci. 2018;153:172–86. 10.1016/j.clay.2017.12.021.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wang X, Yu M, Li L, Fan X. Synthesis and morphology control of nano-scaled magnesium hydroxide and its influence on the mechanical property and flame retardancy of polyvinyl alcohol. Mater Express. 2019;9(6):675–80. 10.1166/mex.2019.1545.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Velázquez-Carriles C, Macías-Rodríguez ME, Ramírez-Alvarado O, Corona-González RI, Macias-Lamas A, García-Vera I, et al. Nanohybrid of thymol and 2D simonkolleite enhances inhibition of bacterial growth, biofilm formation, and free radicals. Molecules. 2020;27(19):6161. 10.3390/molecules27196161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Li H, Wang X, Li P, Li Y, Wang H. Comparative study of antioxidant activity of grape (Vitis vinifera) seed powder assessed by different methods. J Food Drug Anal. 2008;16(6):67–73. 10.38212/2224-6614.2321.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Gonçalves TB, Braga MA, de Oliveira FFM, Santiago GMP, Carvalho CBM, Cabral PB, et al. Effect of subinihibitory and inhibitory concentrations of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng essential oil on Klebsiella pneumoniae. Phytomedicine. 2012;19(11):962–8. 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.05.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. 2012. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id=564ceedf5e9d97daf08b45a2&assetKe y=AS%3A297254750572544%401447882463055Accessed 15, November 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Vasconcelos SECB, Melo HM, Calvacante TTA, Júnior FEAC, de Carvalho MG, Menezes FGR, et al. Plectranthus amboinicus essential oil and carvacrol bioactive against planktonic and biofilm of oxacillin- and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):2–9. 10.1186/s12906-017-1968-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Casas-Junco PP, Solís-Pacheco JR, Ragazzo-Sánchez JA, Aguilar-Uscanga BR, Bautista-Rosales PU, Calderón-Santoyo M. Cold plasma treatment as an alternative for ochratoxin a detoxification and inhibition of mycotoxigenic fungi in roasted coffee. Toxins. 2019;11(6):337. 10.3390/toxins11060337.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Clarkson C, Maharaj VJ, Crouch NR, Grace OM, Pillay P, Matsabisa MG, et al. In vitro antiplasmodical activity of medicinal plants native to or naturalized in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92(2–3):177–91. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Ates M, Daniels J, Arslan Z, Farah IO. Effects of aqueous suspensions of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on Artemia salina: assessment of nanoparticle aggregation, accumulation, and toxicity. Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185(4):3339–48. 10.1007/s10661-012-2794-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Trivedi MK, Patil S, Mishra RK, Jana S. Structural and physical properties of biofield treated thymol and menthol. J Mol Pharm Org Process Res. 2015;3(2):1000127. 10.4172/2329-9053.1000127.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Sierra-Fernández A, Gómez-Villalba LS, Muñoz L, Flores G, Fort R, Rabanal ME. Effect of temperature and reaction time on the synthesis of nanocrystalline brucite. Int J Mod Manuf Technol. 2014;6(1):50–4.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Clavier B, Baptiste T, Massuyeau F, Jounanneaux A, Guiet A, Boucher F, et al. Enhanced bactericidal activity of brucite through partial copper substitution. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:100–13. 10.1039/C9TB01927H.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Liu Z, Yang Y, Fan W, Yu H, Zhang W, Zhong H, et al. Hydro thermal synthesis and morphology control of magnesium hydroxide flame retardant. Chem World. 2002;11:612–4. 10.1166/mex.2019.1545.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Hidouri S, Jafari R, Fournier C, Girard C, Momen G. Formulation of nanohybrid coating based on essential oil and fluoroalkyl silane for antibacterial superhydrophobic surfaces. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2022;9:100252. 10.1016/j.apsadv.2022.100252.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Constantino-Vera RI, Barbosa CAS, Bizeto MA, Dias PM. Intercalation compounds involving inorganic layered structures. An Acad Bras Ciénc. 2000;72(1):45–9. 10.1590/s0001-37652000000100006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Ziyat H, Naciri Bennani M, Hajjaj H, Mekdad S, Qabaquos O. Synthesis and characterization of crude hydrotalcite Mg–Al–CO3: Study of thymol adsorption. Res Chem Intermed. 2018;44:4163–77. 10.1007/s11164-018-3361-9.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Tian Q, Yin WZ, Zhang LL, Liu L. Synthesis of hydrotalcite using brucite as the source of magnesium. Adv Mater Res. 2010;158:241–7. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.158.241.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Dong C, He G, Zheng W, Bian T, Li M, Zhang D. Study on antibacterial mechanism of Mg(OH)2 nanoparticles. Mater Lett. 2014;134(1):286–9. 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.07.110.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Shrivastava R, Chng SS. Lipid trafficking across the Gram-negative cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(39):14175–84. 10.1074/jbc.AW119.008139.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Zhu Y, Tang Y, Ruan Z, Dai Y, Li Z, Lin Z, et al. Mg(OH)2 nanoparticles enhace the antibacterial activities of macrophages by activating the reactive oxygen species. J Biomed Mater Res. 2021;19(11):23692380. 10.1002/jbm.a.37219.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Pan X, Wang Y, Chen Z, Pan D, Chen Y, Liu Z, et al. Investigation of antibacterial activity and related mechanism of a series of Nano-Mg(OH)2. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;5(3):1137–42. 10.1021/am302910q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Kim H, Lee S, Son B, Jeon J, Kim D, Lee W, et al. Biocidal effect of thymol and carvacrol on aquatic organisms: Possible application in ballast water management systems. Mar Pollut Bull. 2018;133:734–40. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.06.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Halus AF, Horozov TS, Paunov VN. Controlling the antimicrobial action of surface modified magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles. Biomimetics. 2019;4(2):41. 10.3390/biomimetics4020041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Saifullah V, Arulselvan P, El-Zowalaty ME, Tan WS, Fakurazi P, Webster TJ, et al. A novel para-amino salicylic acid magnesium layered hydroxide nanocomposite anti-tuberculosis drug delivery system with enhanced in vitro therapeutic and antiinflammatory properties. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:7035–50. 10.2147/IJN.S297040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Saifullah B, Arulselvan P, Fakurazi S, Webster TJ, Bullo N, Hussein MZ, et al. Development of a novel anti-tuberculosis nanodelivery formulation using magnesium layered hydroxide as the nanocarrier and pyrazinamide as a model drug. Sci Rep. 2022;12:14086. 10.1038/s41598-022-15953-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Kimbaris AC, González-Coloma A, Andrés MF, Vidali VP, Polissiou MG, SantanaMéridas O. Biocidal Compounds from Mentha sp. Essential Oils and Their Structure-Activity Relationships. Chem Biodivers. 2017;14(3):1–13. 10.1002/cbdv.201600270.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Alves MM, Batista C, Mil-Homens D, Grenho L, Fernandes MH, Santos CF. Enhanced antibacterial activity of Rosehip extract-functionalized Mg(OH)2 nanoparticles: An in vitro and in vivo study. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2022;217:112643. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112643.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”