Abstract

Bio-fortification is a potential technique to tackle micronutrient deficiencies that remain. Wheat grain bio-fortification has the ability to decrease malnutrition because it represents one of the most essential staple crops. Bio-fortification is cost-effective and evidence-based sustainable technique to address malnutrition in wheat varieties possessing additional micronutrient contents. Nano-biofortification is a novel approach, enriching crops with essential nutrients in order to supplement human diets with balanced diets. The current study was designed to explore the potential role of phytogenic iron nanoparticles (Fe-NPs) to enhance nutritional contents in wheat plants to fulfill the nutrient deficiency important for human and animal health. In the current study, Fe-NPs were fabricated by using the extract of Mentha arvensis L. that were irregular in shape with an approximate size range of 40–100 nm. Further, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) analyses were deployed to confirm the presence of t of various functional groups involved in the green and eco-friendly fabrication of Fe-NPs. The effects of phytogenic Fe-NPs were examined on various physiological and biochemical parameters such as total proline, total chlorophyll, carbohydrates, protein, crude fibers, and lipids contents. Moreover, wheat physiological and biochemical profiling was carried out, and it was noticed that Fe-NPs significantly altered the physico-biochemical profiling of wheat plants. Multiple methods of administration of Fe-NPs were used to fortify the wheat crop. However, the Fe-NPs assisted seed priming along with foliar applications at various concentrations (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1) were found more suitable to enhance the contents of proline, Chlorophyll a, b, total chlorophyll, carbohydrate, proteins, fibers, and lipids (20.22%, 18.23%, 17.25%, 16.32%, 12.34%, 24.31%, 19.52%, and 11.97%, respectively) in wheat plants. Further, wheat flour was exposed to digestive enzymes, with the iron content gradually increased in a dose-dependent manner. The nutritional analysis of wheat zinc (Zn), molybdenum (Mo), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), yttrium (Y), and copper (Cu) and the fatty acid profile have demonstrated divergent patterns of behavior. Similarly, iron content was also increased significantly in response to the exposure to Fe-NPs.

1 Introduction

Agriculture serves as the backbone of the majority of developing nations and is critical to humanity’s existence on Earth. With a rising population, novel agricultural innovations are required to meet future demands [1]. Approximately 14% of worldwide people suffer from nutritional iron deficiency [2]. Iron consumption in adults is generally lower than the 10–18 mg daily nutritional requirement [3]. Fortification is an approach that has a stellar record of enhancing dietary diversification and drastically reducing nutritional deficiencies in food grains [4]. The benefits of agronomic bio-fortification are both immediate and long-term. Agronomic bio-fortification is a short-term solution to this mess compared to plant breeding [5]. Rawanda’s government commenced food fortification with essential micro-nutrients such as Fe, Zn, I, sugars, salt, vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B12, and folic acid on an industrial scale. The most common and cost-effective way to treat anemia in people is to consume iron-fortified foods [6].

The term bio-fortification relates to nutritious fortified agriculture products with greater bio-availability and digestibility to humans which are produced and farmed utilizing current biotechnology tools, traditional plant hybridizing and agronomic gentility [7]. Hidden hunger causes serious health problems in underdeveloped countries, which had become an acute fiscal burden on the health sector. Increased global population growth and an increase in food demand pose a very challenging scenario for agricultural scientists [8]. A persistent deficiency of critical vitamins and nutrients in the food is a major issue in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [9]. Among teenagers who suffer from thalassemia, 50% lack key micro-nutrients like vitamin A, Fe, and folic acid. This can happen to both pregnant and non-pregnant women [10].

Wheat plants belong to the family Poaceae and the second leading crop worldwide. Wheat considered a major staple agronomic food crop as a source of essential proteins and nutrients required for the normal physiological and biochemical functioning of the human and animals [11]. According to estimation wheat production exceeded as 761.7 million tons in (2017/2018), but its demand exceeded 762.4 million tons due to enhanced world population in the survey of (2019/2020) [12]. Moreover, wheat glutens are mainly used in baked breakfasts and in crumpets, flakes, cookies, chapattis biscuits, noodles, etc. Due to the increasing population, wheat production should be enhanced to fix the gap between consumption and growth. Unfortunately, wheat is suffering from environmental stresses due to poor productivity and due to irregular use of various fertilizers mismanagement of a farmer’s field operation and traditional technology [13]. Soil nutrient levels and plant nutrient absorption need to be analyzed to determine the right amount of wheat fertilizer. Adequate moisture and humidity are also required for crops to respond favorably to fertilizer. Moreover, various plants, species, and genotypes absorb both nutrients and water at different rates as well as respond differently to various environmental stresses [14]. Because organic manure alone cannot meet the nutrient demands, the wheat plants produced low yields. Chemical fertilizers are applied to wheat in a timely way which boosts up the wheat output [15]. A study reported that mineral fertilizers and organic manures optimally boost up the output of wheat, agricultural field efficiency, and water usage efficiency. Wheat growth characteristics are changing substantially as a result of biological fertilizer injection [12].

Iron is a crucial micro-nutrient that exists in two forms, heam and non-heam, and is naturally present in a variety of foods such as fruit, vegetables, meat, and fish [16]. An imperative role played by iron fortifiers (Fe2+ and Fe3+) is to facilitate iron absorption in mammals. Water-soluble iron compounds have an impact on food tastes, colors, and acceptability as well as shelf life. Iron nanoparticles have been shown to be safe for consumption and to cause no harm to human the body in both in vivo and in vitro studies [17]. A major role for iron is as an electron carrier, located within the chloroplasts, RNA synthesis, C3 cycle of plants, and role in the operation of various respiratory enzymes. In the twenty-first century, nanotechnology had gained popularity as an appealing technology that brings improvement in the pharmaceutical, farming, and food industries [18]. The food industry uses nanoparticles in a variety of ways, including supplements, transporters, antibacterial agents, and injectables for improving mechanical performance and toughness of food packaging [19]. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has included one durum wheat variety, MACS 4028, in its National Nutrition Strategy to combat hidden hunger in rural India. It contains high Fe (46.1 ppm) and Zn (40.3 ppm) [20].

According to the literature, nanoparticles may be utilized to manufacture numerous kinds of products such as nano-sensors, nano-coating materials, food packaging, precision farming, and nano-fertilizers [19]. Employing phytogenic Fe-NPs in crops has been shown to improve the physico-morphological properties of the plants. Iron nanoparticles promote photosynthesis by increasing the leaf area, biomass, and the number of leaves/branches. Additionally, iron nanoparticles (NPs) are substantially smaller than normal ferrous oxides and iron molecules. Plant organs have increased accessibility to iron as they can form more complexes with other substances (19). Current agriculture focuses on greater yields but compromising nutritional profile. There has been recent research indicating that mineral concentrations are negatively correlated with grain yield, indicating wheat varieties with better grain yields have significantly lower mineral content [21]. The purpose of nano-fertilizers is to drastically improve crop growth potential, increase fertilizer efficiency, reduce nutrient losses, and reduce negative environmental impacts [22]. Furthermore, reducing the particle size of the nanoparticles enhances the interaction between the fertilizers and crops, resulting in greater nutrient absorption by the crops [23].

Human health, particularly that of those living in rural regions, is being negatively impacted by nutrient deficiencies in food crops, and nanotechnology may provide the most long-term solution [24]. The nutrients in food can be enhanced in several ways, including dietary variety, medication use, and industrial fortification. The affordability and sustainability of these techniques have not been fully attained, though. Fertilizers provide nutrients for plants to absorb; however, the majority of traditional fertilizers are not very effective at doing so [25,26].

Biofortification, or increasing the iron concentration in edible plant parts, is seen as a long-term solution to iron deficiency, which is a serious global health issue. For all living things, iron (Fe) is one of the essential mineral micronutrients. Fe takes part in a number of biological and growth activities in plants [27]. Additionally, iron nanoparticles (NPs) are substantially smaller than normal ferrous oxides and iron molecules. Plant organs have increased accessibility to iron as they can form more complexes with other substances [28].

In the current study, we have focused on iron nanoparticles-assisted bio-fortification in wheat. Promising results have been observed and could possibly lead to nanoparticles-assisted bio-fortification in the future as a promising potential tool for different essential animals.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of plant-based Fe-NPs

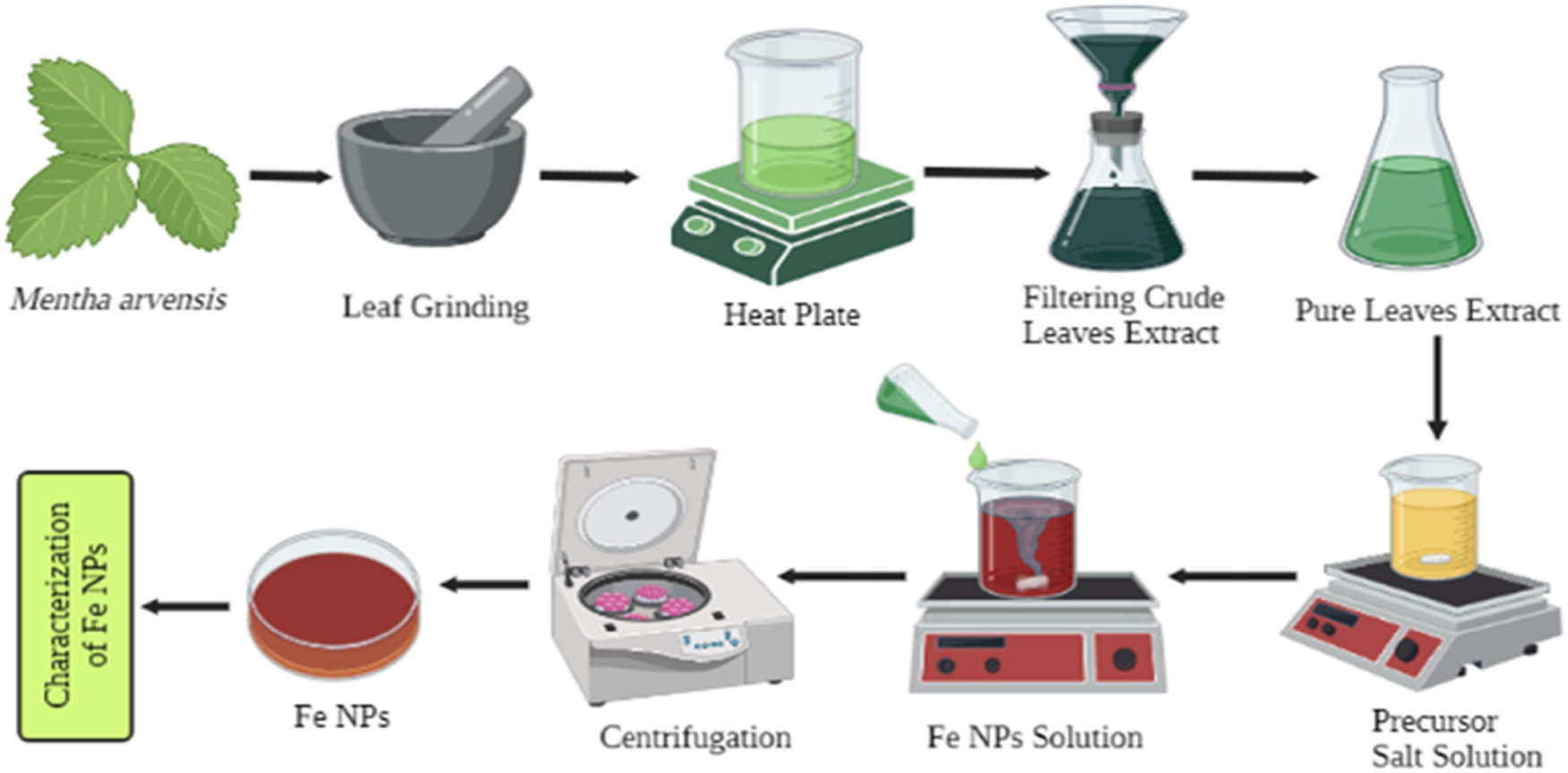

In the present research study, the Fe-NPs were synthesized by using fresh leaves of Mentha arvensis L. which act as a reducing, capping, and stabilizing agent. The synthesis of Fe-NPs has two steps, i.e., plant extraction preparation and synthesis of nanoparticles. In plant extraction preparation, the fresh leaves of Mentha arvensis are washed thoroughly with distilled water to remove dust and ground with the help of a pestle and mortar. About 25 g of leaves is added to a beaker containing 250 mL of distilled water and then placed on a hot plate at 80°C for 45 min. The plant extract solution was left for some time to cool down and then filtered trice to remove the impurities. Second, to prepare Mentha arvensis-mediated iron nanoparticles, 0.45 g of ferrous sulphate was dissolved in 500 mL of distilled water to make a 1 mM salt solution. The precursor salt solution was placed on a magnetic stirrer and the temperature of the hot plate was kept at 150°C for 2 h. The plant extract was added drop by drop until the precursor solution color changed to yellowish to red brick color. Reduction of FeSO4 to Fe-NPs was completed in 48 h by a color change from colorless to red brick color. The Fe-NPs were fractionated by centrifuging at 12,000 rpm (Figure 1). Pallets which are obtained were dried and stored for further characterization [29].

Procedure of iron nanoparticle synthesis from fresh leaves of Mentha arvensis.

2.2 Characterization of nanoparticles

Several approaches include UV-visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were deployed for the physicochemical characterization of Fe-NPs. To verify the reduction of the ferric ions in the colloidal solution, a 1 mL aliquot of the colloidal FeNPs solution in quartz cuvettes was examined using UV–Vis spectroscopy (Labomed UVD 3500, Los Angeles, CA, USA) with distilled water as a reference and 0.05 mM FeSO4 as a blank.

The function groups that were bound on the iron surface and were involved in the synthesis of FeNPs were identified using FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer FTIR-Spectrum, Akron, OH, USA) After 72 h of incubation, the FeNPs were isolated by repeated centrifugation (three–four times) of the reaction mixtures at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was replaced by deionized water and the pellet was stored as powder. After being dried, the FeNPs were put through an FTIR analysis using the potassium bromide pelleting process at a ratio of 1:100.

An SEM SIGMA (TESCAN MIRA3 FEG-SEM, Nano Images, LLC, CA, USA) was used to examine the nanoparticles and establish their surface shape. Substrates were prepared on a clean 5 mm × 5 mm Si substrate cleaved from a 100 mm diameter wafer. The substrate was allowed to react for 2–6 h, and the sample was prepared by centrifuging a colloidal solution at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was dried after being centrifuged many times, after which it was dispersed in deionized water and the procedure was repeated. Finally, the dry pellet was obtained, which was further subjected to structural characterization by SEM analysis as per the procedure described by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST-2007.

Following drying on a carbon-coated copper grid, the reduced FeNPs were analyzed using EDX (JSM-IT 500, Jeol, Boston, MA, USA), which also allowed the elemental composition to be determined. On a Philips X-ray analyzer having a model (PW1710), the iron oxide remnant was placed on X-ray diffraction experiments were carried out by using Cu Kα (= 1.5405 Å) radiation. The ligands were created using the standard diazotization process. To carry out the experiment, three azo dyes were used. After then, FeCl3 was added to ethanolic solutions and diluted with three different azo dyes with 1:2 molar ratios. To complete the reaction, the resultant solution was simmered at gird for 6 h. The deposited solid material was vacuum filtered out, repeatedly washed with ethanol, and then dried in silica gel in a desiccator. Several spectroscopic and analytical techniques were used to analyze the resultant complexes [30,31].

2.3 Application of Fe-NPs on wheat

The germination experiment was carried out in a laboratory under aseptic conditions. An experiment in a greenhouse was done to see how well the synthesized Fe-NPs worked on wheat plants. Sandy loam soil, which contains 44.2% sand, 4.6% silt, and 51.2% clay, was used to grow wheat plants in pots that were 24 cm in diameter and 19 cm high. The relative humidity in the greenhouse was maintained between 80% and 90%, while the temperature was maintained between 21°C and 25°C. Seeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) were obtained from NARC (National Agriculture Research Center Islamabad, Pakistan). Locally available wheat variety NARC-11 was used for the experiment. The experiment was performed in triplicates by using the different concentrations of Fe-NPs such as 10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1 as compared to untreated (control) plants.

2.3.1 Fe-NPs treatments

Three different concentrations of Fe-NPs 10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1 were prepared and applied in three different ways, i.e., seed priming (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1), foliar spray (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1), and combination of seed priming and foliar spray (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1). Three different techniques were used for nanoparticle application including seed priming, foliar spray, and combination of seed priming plus foliar spray (Table 1).

Treatment detail of iron nanoparticles

| Treatments | Applications |

|---|---|

| Control | Wheat plants without Fe-NPs |

| T1 | Seed priming + Fe-NPs (10 mg·L−1) |

| T2 | Seed priming + Fe-NPs (20 mg·L−1) |

| T3 | Seed priming + Fe-NPs (30 mg·L−1) |

| T4 | Foliar spray with Fe-NPs (10 mg·L−1) |

| T5 | Foliar spray with Fe-NPs (20 mg·L−1) |

| T6 | Foliar spray with FeNPs (30 mg·L−1) |

| T7 | Seed priming + foliar spray with (10 mg·L−1) |

| T8 | Seed priming + foliar spray with (20 mg·L−1) |

| T9 | Seed priming + foliar spray with (30 mg·L−1) |

2.4 Agronomical and physiological parameters

The agronomic parameters included plant height, stem diameter, and weight of 1,000 seeds for Triticum aestivum variety (NARC-11) days to maturity, and days for flowering. The physiological parameters included total chlorophyll contents and proline content was examined for wheat variety (NARC-11) using the following methodologies.

2.4.1 Estimation of chlorophyll content

Chlorophyll content was measured by using the method of Amon [32], with slight modification. Leaf tissue was carefully weighed and homogenized in 80% chilled acetone. The resulting solution was filtered twice, and absorbance was noted at three different wavelengths, i.e., 633, 645, and 663 nm, on a spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were calculated with the help of the following formula:

2.4.2 Total proline content

Proline content was determined by the method described by Bates [31,33]. About 0.2 g of leaf tissue was crumbled in 10 mL of sulfosalicylic acid, filtered through Whattman filter paper No. 1, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. In a test tube, 2 mL of filtrate was mixed with 2 mL of glacial acetic acid along with 2 mL of ninhydrin and incubated at 100°C water bath. After 1h, the test tubes were placed in a desiccator and 4 mL of toluene was added to each test tube and mixed well by placing on a vortex for 5 min. From the two layers of solution, the upper translucent layer was separated, and absorbance at 520 nm was determined. The following formula was used to calculate proline content:

2.5 Wheat flour quality parameters

2.5.1 Total sugar contents (TSC)

The total soluble sugars were extracted from the whole wheat flour (300 mg of dry weight) of all selected genotypes along with checks by using 15 mL of 80% and 70% ethanol each by refluxing in a water bath for 20 min. After refluxing, the supernatants were collected and mixed. About 1 mL of extract from mixed supernatant was taken and evaporated at room temperature and made the final volume to 25 mL with water and used for the estimation of total soluble sugars. In 1 mL of extract, 1 mL of 1% phenol was added, followed by the addition of 5 mL of sulfuric acid. Absorbance was read at 490 nm by using glucose as standard [32,34].

2.5.2 Total protein contents (TPC)

The percent protein content was determined from wheat grains using (Infratec 1241 whole grain analyzer M/S FOSS) by non-destructive method previously standardized for high throughput screening of whole wheat grains for protein content

2.5.3 Crude fiber contents (CFiC)

Crude fiber content of the seed was determined by the method of AOAC [35].

2.5.4 Crude fat contents (CFC)

AOAC method was used to measure the percentage of crude fat content [35].

2.6 Bio-fortification analysis

2.6.1 Acquisition of iron in wheat flour

A precise weight was recorded in crucibles with covers for wheat samples. The samples were then oven-dried overnight at 70°C before being refrigerated in a desiccator. After removing smoke from the samples, they were heated in a muffle furnace at 520°C for 3 h. During this time, all organic matter was incinerated and white ash remained. Again, wheat samples were placed for 24 h in an oven to remove moisture before being cooled in a desiccator and reweighed. The micro-nutrient composition in wheat samples was determined by using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The standard calibration curve was used to evaluate nutrient contents in the 0.110 g·mL−1 limit. To compensate for sample attrition related to volatility and evaporation, 1 ppm of yttrium was added to each sample [36].

2.6.2 In vitro enzymatic digestion of wheat flour

Wheat flour samples were diluted using imitated peptic pancreatic digestion. The enzymes and bile extracts were soaked in distilled water. The iron levels in the samples used in the assay influenced their weights. Wheat flour samples were diluted using imitated peptic pancreatic digestion. The enzymes and bile extracts were soaked in distilled water. The iron levels in the samples used in the assay influenced their weights. About 10 ml of isotonic salt solution of 140 mM NaCl + 5 mM KCl was added to wheat samples and added few drops of 1 M HCl. The pH was adjusted for each replicate. Then each sample solution was diluted with 0.5 mL pepsin, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 75 min. The pH was maintained at 5.5 with NaHCO3 (1 M) to cease peptic digestion. To initiate pancreatin-bile digestion, 2.5 mL of bile extract (8.5 mg·mL−1 bile extract and 1.4 mg·mL−1 pancreatin) was added, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 using NaHCO3 (1 M). The volume was raised to 15 mL by adding isotonic salt solution, and the sample mixture was incubated at 37°C for 120 min. Centrifugation was done for 10 min at 3,000 rpm, and digestible precipitate was saved for future experiments [37].

2.6.3 CaCO2 cells reviving and splitting for bio-absorption analysis

The samples were incubated in minimum essential medium (MEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% antifungal antibiotics (1%). Totally, 50,000 samples or cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells in 2.5 mL of DMEM in six different well plates. The samples were incubated for 2 weeks adjusting temperature at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air, with medium replaced after 2 days. The samples or cells were then cultivated at 37°C for 24 h. After that, the cells were fed with 2 mL of fresh MEM. Each digest was pipetted into cellulose dialysis tubing and subjected to the cell-washing medium. The samples were then grown at 37°C for 2 h to allow iron absorption. For control, just MEM medium was employed. The digest was then removed, and the cells were supplied 1 mL of enriched MEM to grow again for 22 h. Further, samples were then washed in phosphate buffer solution and mashed utilizing mammalian protein extraction reagent. To eliminate dead cells, the supernatant was then centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicates and (completely randomized design) CRD was used to analyze the data. Heat map illustration utilizing data of Pearson correlation by PAST 3.9 version was used for analyzing nutrient profiling.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of plant-based Fe-NPs

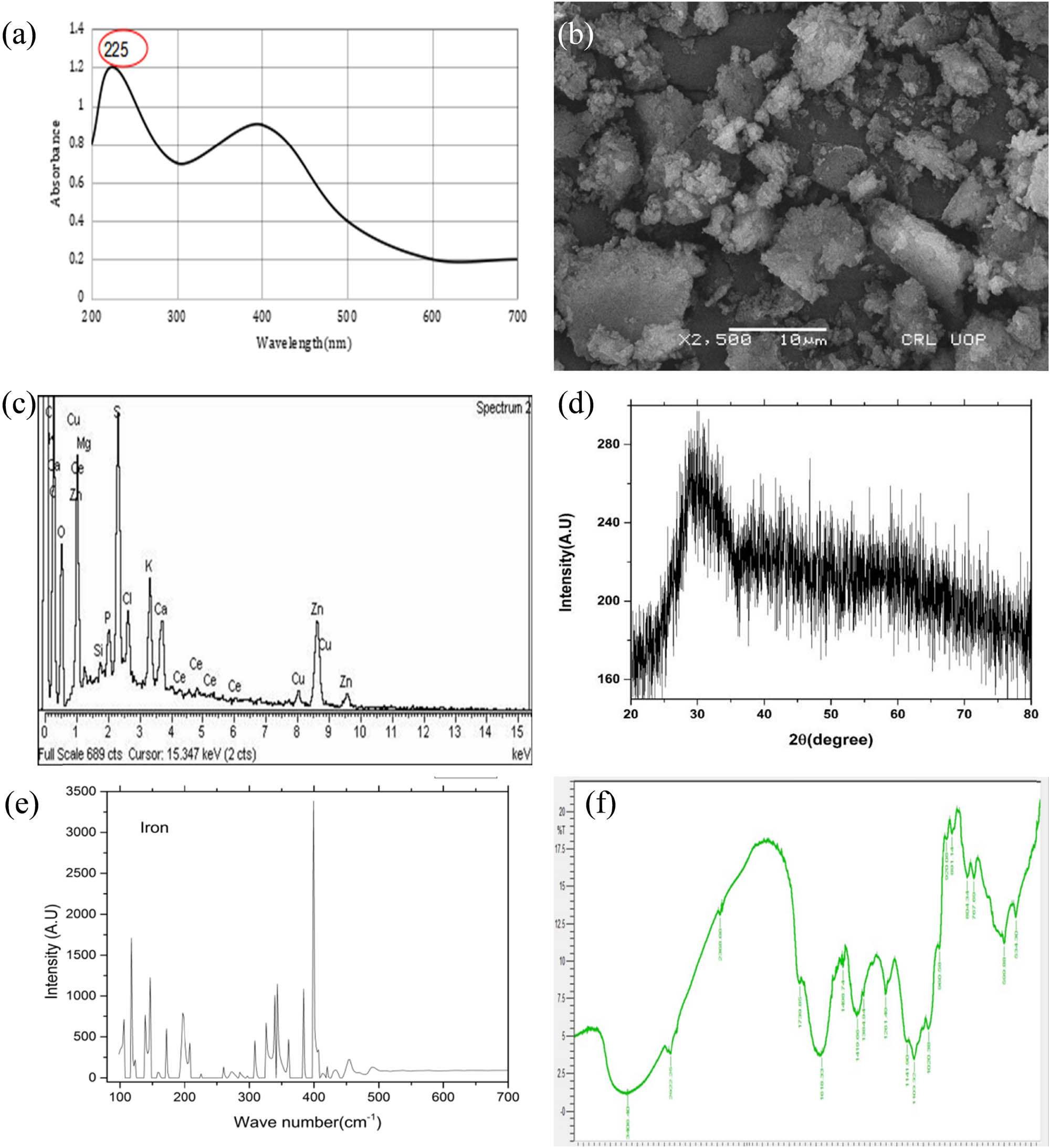

UV–Vis spectrum was used for the characterization of Fe-NPs. The absorption peaks have confirmed the synthesis of Fe NPs (Figure 2a). The absorption peak that falls in the range between 215 and 290 nm was considered as small-sized nanoparticles while peaks that lie above 300 nm were informed as large-sized nanoparticles. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed the shape of Fe-NPs was irregular. The size of phyto-synthesized Fe-NPs using fresh leaves of Mentha arvensis was found to be 100 nm. Results of SEM are shown in Figure 2b.

(a) UV–Vis spectrum of plant-based synthesized Fe-NPs; (b) SEM spectrum of phyto-synthesized Fe-NPs; (c) EDX analysis for Mentha arvensis mediated Fe-NPs; (d) XRD spectrum of green-synthesized Fe-NPs; (e) intensity peaks for Mentha arvensis mediated Fe-NPs; (f) FTIR spectrum of plant-based synthesized Fe-NPs.

The crystalline structure of films is determined by an X-ray diffractometer. Researchers use it to analyze thin films and gain insight into the deposited film. The method is used to assess crystal atomic and molecular structure. Plant-based iron nanoparticle arrangements were studied by X-ray diffraction at an angle of 2 thetas between 20° and 80° (scanning range) at a scanning rate of 2°·min−1. The X-ray diffraction spectroscopy characterization was used to determine the peak intensity, width, location, full width, and half maximum (Figure 2d and e). The energy dispersive X-ray was done for investigation of elemental analysis. At 15.267 keV, Fe attained 38% area along with Ce, while other elements included Cl, K, Ca, O, Si, and P covered the remaining space for the iron nanoparticles sample (Figure 2c). The FTIR spectrum of Fe-NPs extracted from fresh leaves of Mentha arvensis was applied to determine the functional group responsible for the production and stability of green synthesized Fe-NPs. According to FTIR spectra at a specific absorbance, the wave number ranges from 400 (far IR spectrum) to 4,000 (mid IR spectrum) for green synthesized FeNPs.

The FTIR spectra of Fe-NPs synthesized from Mentha arvensis generated 19 absorption peaks including 634.30, 690.88, 767.69, 804.34, 891.14, 920.08, 960.58, 1,020.38, 1,103.32, 1,141.90, 1,261.40, 1,384.94, 1,410.06, 1,498.74, 1,618.33, 1,739.85, 2,368.66, 2,922.26, and 3,406.40 cm−1 (Figure 2f). Each peak represents the presence of a particular functional group that serves as a capping agent to stabilize Fe-NPs. The trajection of the peak at 3,200–3,420 cm−1 of wave number may be due to the presence of hydroxyl (O–H) group and amino (N–H) group. The strongest absorption peak was observed at 3,406.40 cm−1 determining the presence of the amino group, whereas the weakest absorption peak was obtained at 634.30 and 699.88 cm−1 for functional group (C–H) cis and trans alkenes. The peak spectrum was noticed for amide and hydrocarbon groups that participated higher than any other functional groups to stabilize the nanoparticles. The other functional groups found at wave number for 1,020.38 (aromatic hydrocarbon), 1,103.32–1,261.40 cm−1 (cyclic ether), 1,384.94 cm−1 (methyl), 1,498.74 cm−1 (aromatic aryl group), and 1618.33–1,739 cm−1 (carbonyl group, aldehyde, ketones, and ester), respectively.

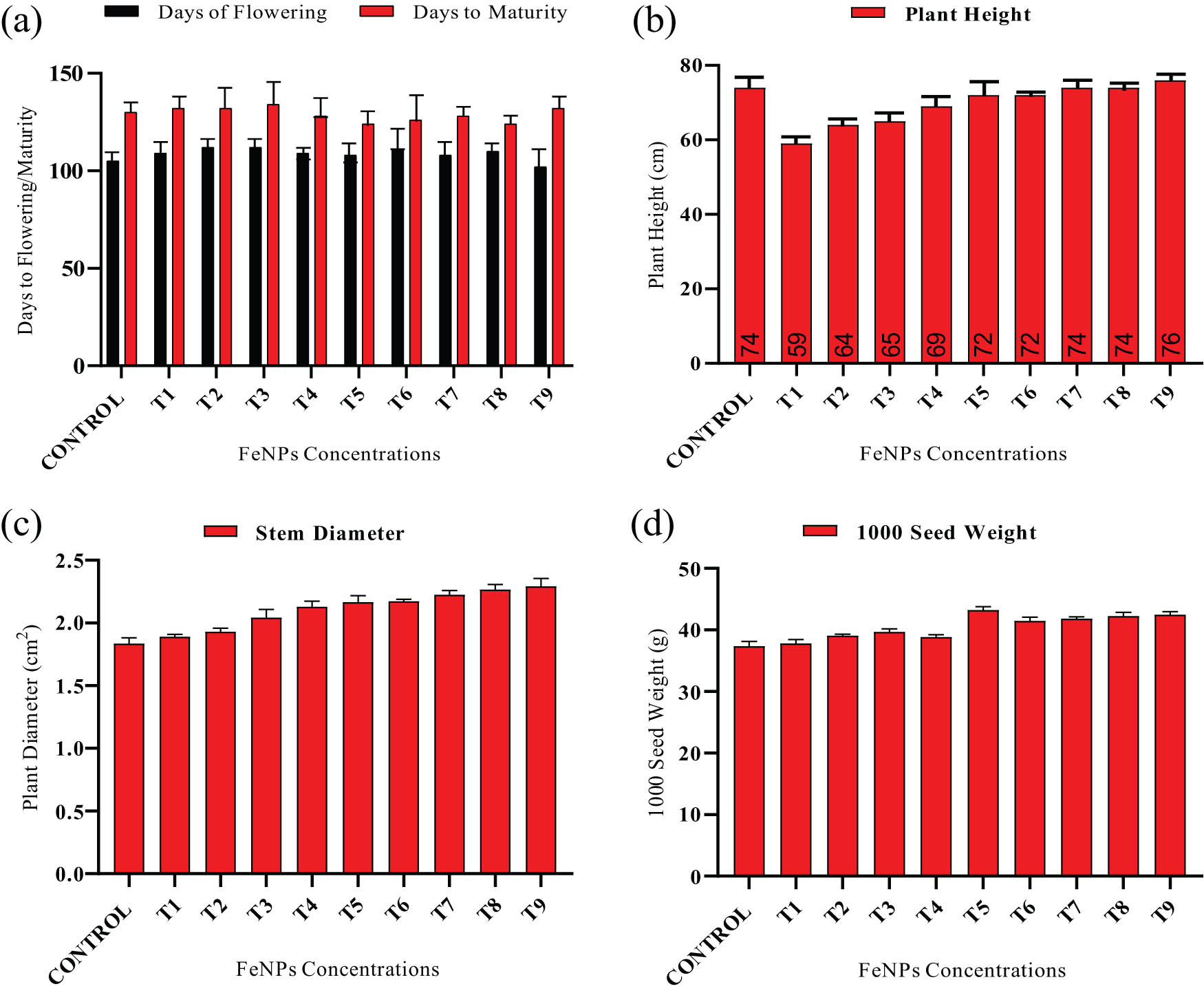

3.2 Effect of iron nanoparticles on the agromorphological traits of the wheat

The application of FeNPs causes an insignificant increase in plant height. Foliar spray of Fe-NPs has shown minimal effectiveness on plant height of wheat variety (NARC-11) as compared to seed priming and a combination of seed priming plus foliar applications and untreated plants. By applying foliar spray on wheat, the highest plant height was 76 cm recorded at 30 mg·L−1 for both iron nanoparticles as compared to control. The lowest plant height 60 cm was found in wheat (NARC-11), when the plant was treated with 10 mg·L−1 iron nanoparticles using seed priming application (Figure 3b). The seed priming followed by foliar delivery of iron nanoparticles exhibited a maximal plant diameter of 2.42 cm2 at 30 mg·L−1 and seems greater than untreated plants in the current research investigation.

(a) Days to flowering and days to maturity, (b) average plant height, (c) stem diameter, and (d) weight of 1,000 seeds for wheat variety (NARC-11). The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept < 0.05. Control, T1 (seed treated with 10 mg·L−1), T2 (seed treated with 10 mg·L−1), T3 (seed treated with 10 mg·L−1), T4 (foliar spray with seed with 10 mg·L−1), T5 (foliar spray with seed with 20 mg·L−1), T6 (foliar spray with seed with 30 mg·L−1), T7 (seed treated + foliar spray with seed with 10 mg·L−1), T8 (seed treated + foliar spray with seed with 10 mg·L−1), and T9 (seed treated + foliar spray with seed with 10 mg·L−1).

Healthy flowers indicate a high rate of plant reproduction. Flowers develop exceptionally soon after 105 days in untreated plants compared to plants treated with iron nanoparticles using three separate strategies. After foliar sprays of nanoparticles on wheat (NARC-11), seed priming and foliar spray of Fe-NPs resulted in rapid blossoming at 30 mg·L−1 after 102 days. At blooming, neither nanoparticle showed a significant difference. Flowers that mature early indicate a rapid pace of growth in plants. Control plants matured much earlier than plants treated with varied concentrations of iron nanoparticles using seed priming, foliar, and seed priming + foliar spray approaches. The day to maturation for the control plant in wheat (NARC-11) was 130 days, whereas foliar sprays of 20 mg·L−1 iron nanoparticles cause early maturity in wheat (NARC-11) after 124 days (Figure 3a). The present study found that foliar spray of Fe-NPs at 20 mg·L−1 was the best concentration for promoting early maturation in wheat varieties.

After the crop season, another key agronomic parameter, 1,000 seed weight, was measured in wheat plants. A total of 1,000 seeds were weighed for each of the three treatments utilized in the research study: seed priming, foliar spray, and a combination of seed priming and foliar spray. The highest weight seen for thousand seed weight (43.2 g) was observed utilizing foliar spray with 20 mg·L−1, Fe-NPs followed by 43.1 g as plants were treated with 30 mg·L−1, Fe-NPs in the foliar stage, and 42.6 g as plants were treated with 20 mg·L−1 Fe-NPs on seed + foliar treatment (Figure 3d).

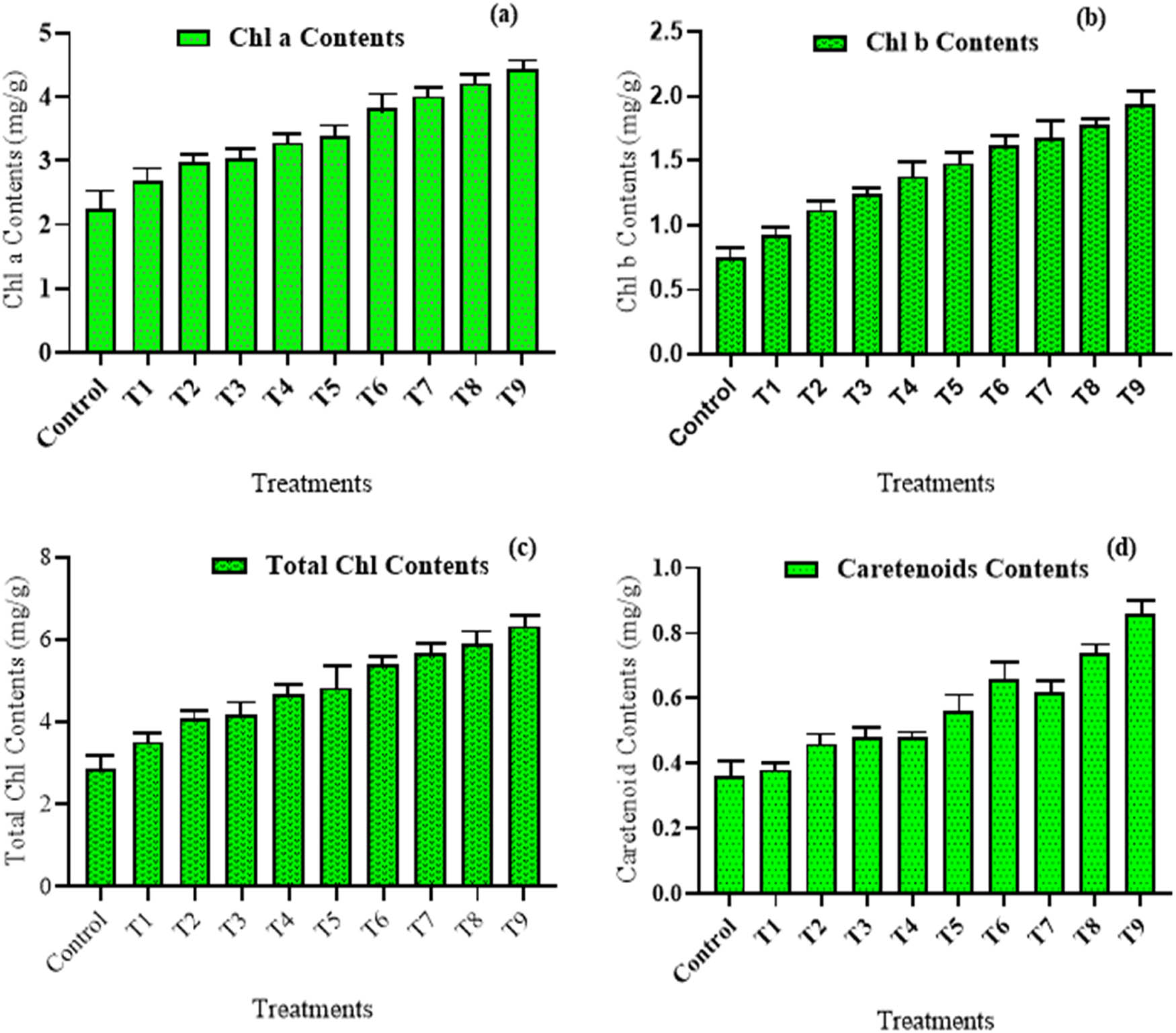

3.2.1 Physiological and biochemical parameter of wheat (NARC-11)

Plants have the ability to generate chlorophyll, a pigment that is ubiquitous and essential for photosynthesis. The application of iron nanoparticles coupled with seed priming with foliar at 30 mg·L−1 resulted in considerably greater chlorophyll a content of 4.24 µg·mL−1 and chlorophyll b content of 1.92 µg·mL−1 as compared to control plants (Figure 4a and b). Total chlorophyll levels are greater in healthy plants as compared to stress plants. Compared to the control, the highest total chlorophyll content of 6.42 µg·mL−1 in wheat (NARC-11) was noticed at 30 mg·L−1, when plants were treated with both seed priming and foliar application of iron nanoparticles as compared to the control. The lowest value for total chlorophyll contents 2.48 µg·mL−1 was observed in untreated wheat variety. Seed priming of wheat variety (NARC-11) with different concentrations (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1) of iron nanoparticles showed least effectiveness results for total chlorophyll contents (Figure 4c). Proline works as an osmoprotectants in plants, assisting them in getting rid of stressful circumstances. The highest proline concentration (1.19 µg·mL−1) was observed in wheat (NARC-11) with 20 mg·L−1 Fe-NPs treatment employing both seed pre-treatment plus foliage spraying. In contrast, wheat plants with 10 mg·L−1 Fe-NPs on seed priming had the lowest proline concentration (0.325 µg·mL−1) as compared to the control. Similarly, the highest carotenoids contents were 0.82 µg·mL−1 recorded for 30 mg·L−1 Fe-NPs on seed priming along with foliar sprays followed by foliar treatment 0.62 µg·mL−1. Negligible variation in carotenoid contents was observed as the plant was pre-treated with Fe-NPs as compared to untreated plants (Figure 4d).

Biochemical characterization of wheat after exogenous application of green synthesized Fe-NPs. (a) Chlorophyll a content, (b) chlorophyll b content, (c) total chlorophyll content, and (d) carotenoids content. The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

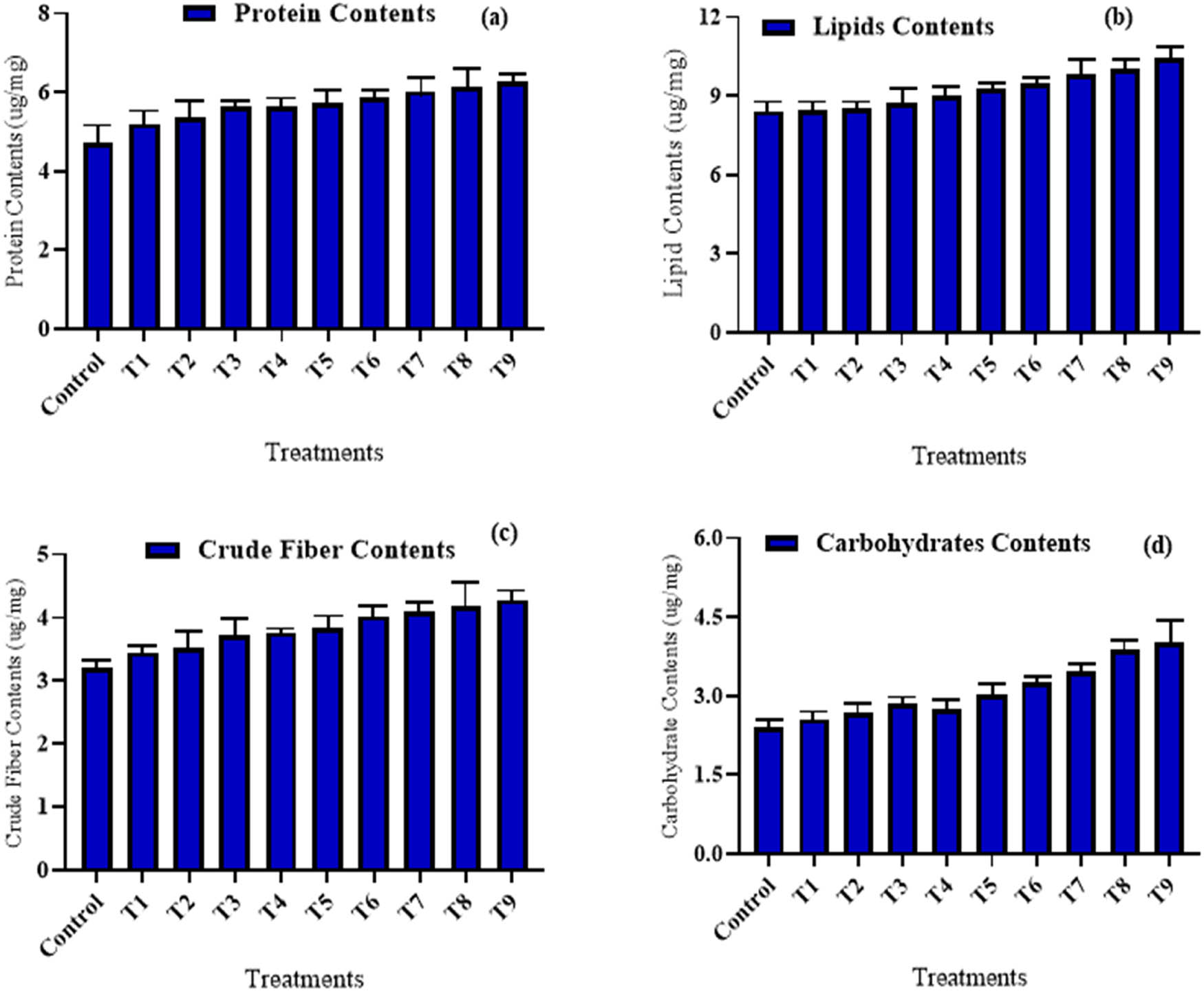

3.2.2 Effect of Fe-NPs on seed quality parameter of wheat (NARC-11)

Bio-fortified wheat variety (NARC-11) treated with different concentrations of ferric nanoparticles such as (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1) improved the seed proteins contents. In the current research study, bio-fortification of wheat variety was done with iron nanoparticles. The wheat variety (NARC-11) that was treated to seed priming plus foliar applications showed the highest protein contents of 6.25 µg·mL−1 at 30 mg·L−1, whereas the lowest protein content of 4.35 µg·mL−1 was observed at 10 ppm, when plants were treated with seed priming (Figure 5a). The crude fiber content was recorded in wheat (NARC-11) for all three approaches, i.e., seed priming, foliar spray, and a combination of both. Noticeable increase of 4.31 µg·mL−1 of crude fiber contents in wheat (NARC-11) was recorded at 30 mg·L−1 as the plant was treated with seed plus foliar with iron nanoparticles as compared to untreated wheat variety having crude fiber contents of 3.19 µg·mL−1. The lowest fiber contents were found at 10 mg·L−1 (3.31 µg·mL−1) as the plant get treated with the seed priming technique (Figure 5c). Marginal variation in crude fiber content was present in wheat for various concentrations of Fe-NPs using the seed priming method.

Seed quality parameters in (a) wheat variety (NARC-11) protein content, (b) lipid content, (c) crude fiber content, and (d) carbohydrates. The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

A marginal increase in carbohydrate contents was found in wheat (NARC-11). The seed pre-treatment with iron nanoparticles was done for wheat (NARC-11) shown a negligible increase in carbohydrate contents for all three different dosages included (10, 20, and 30 mg·L−1), Whereas the highest value seems as 4.32 µg·mL−1 at 30 mg·L−1 and lowest was 2.3 µg·mL−1 at 10 mg·L−1 treated with Fe-NPs using seed pre-treatment as compared to control (Figure 5d). When the wheat variety (NARC-11) was treated with Fe-NPs, the lipid content of the wheat grains changed. The highest lipid contents were found 10.45 µg·mL−1 at 30 mg·L−1, when iron nanoparticles were delivered on the upper surface of leaves of wheat. As the plant was treated with foliar application, the reduction in lipid contents was noted. The lowest value was noted 8.2 at 10 mg·L−1 dosage of iron nanoparticles (Figure 5b).

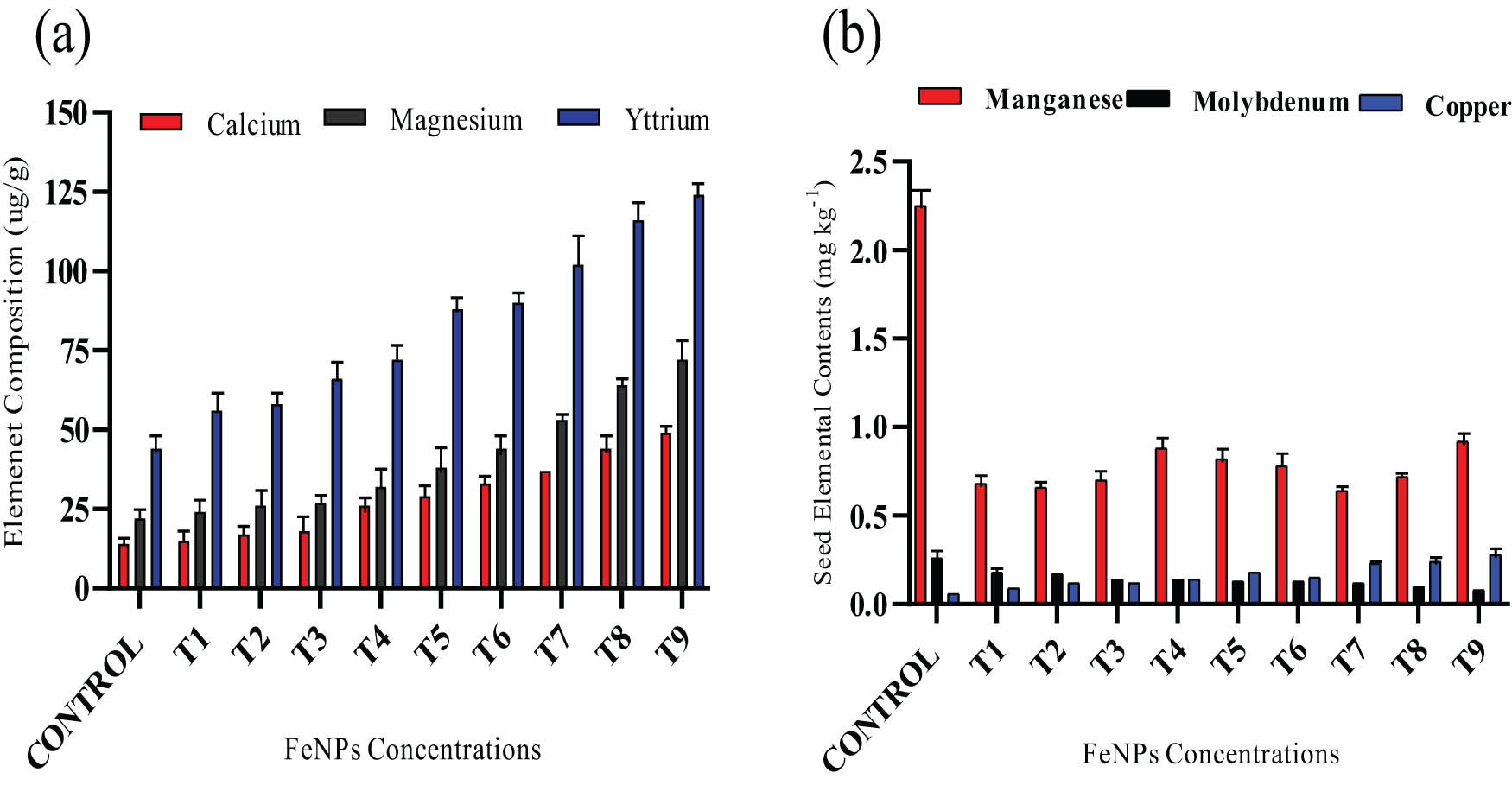

3.3 Effect of Fe-NPs on the elemental profiling of the wheat (NARC-11)

The elemental profiling of wheat was checked after fortification was done using iron nanoparticles (Fe-NPs) that enhance nutritional status. The increase in nutrient accumulation was observed higher for wheat (NARC-11) on treated with iron nanoparticles in three different ways. The delivery of Fe-NPs to wheat boosts nutrients levels for (magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), yttrium (Y), copper (Cu), and molybdenum (Mo). The highest value 76 µg·g−1 of magnesium was recorded at 30 mg·L−1 at seed soaking followed by foliar spray while the lowest value was 21 µg·g−1 at 10 mg·L−1 at seed soaking method as compared to untreated wheat variety (Figure 6a). The wheat (NARC-11) had minimum effect on calcium contents by utilizing seed priming and foliar technique as compared to untreated plants. The highest value 36 µg·g−1 of calcium recorded at 30 mg·L−1 by employing seed priming plus foliar approach. The maximum iron contents 25.8 µg·g−1 were observed at 10 mg·L−1 and less contents 25.1 µg·g−1 seem at 10 mg·L−1 as wheat was treated by using seed pre-treatment plus foliar spray to control variety.

Seed profiling in wheat variety (NARC-11) calcium, magnesium, yttrium (a), manganese, molybdenum, and copper (b). The data in graphs were expressed in terms of mean ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

Similarly, the marginal increment in zinc contents was noticed when plants were processed with iron nanoparticles. The peak zinc contents were determined 25.8 µg·g−1 at 10 mg·L−1 using foliar employment of Fe-NPs. The extreme yttrium contents were ascertained at 118 µg·g−1 at 30 mg·L−1 using combined seed priming plus foliage spray of Fe-NPs as compared to the control. The lowest contents were 46.2 µg·g−1 at 10 mg·L−1. In the current study, wheat fortification was done by applying iron nanoparticles to enhance the nutrient contents of Cu2+ and Mo in wheat grains. A remarkable increase of 0.32 mg·g−1 in copper at 30 mg·L−1 was found using SF methods whereas molybdenum level alleviated at the same concentration (Figure 6b).

3.3.1 Linear Pearson correlation heat map for wheat (NARC-11)

The current study used (PAST 3.9 version) to develop a linear Pearson correlation for a nutritional profile in wheat (NARC-11) after wheat was enriched with iron nanoparticles. The current study investigated the outcomes for nutritional value increase in wheat grains (magnesium, iron, zinc, yttrium, copper, and molybdenum) when sprayed foliar by Fe-NPs, as shown in Figure 7a. As discussed earlier, the foliar intake of iron nanoparticles increased significantly in phenotypic, physiological, and biochemical parameters in the present study. The current investigation discovered that two micro-elements (Mg and Fe) had a greater percentage than 99.9% among all six micro-elements with the highest Eigen values of 8.82 and 1.17. For Zn, an eigenvalue smaller than one indicates that Fe-NPs had less impact (shown in Table 2). The Y, Cu, and Mo eigenvalues with the lowest eigenvalues showed the least variation when targeting iron nanoparticles. The principal components analysis revealed that different concentrations of Fe-NPs were employed in comparison to the control.

(a) Heat map-based on nutrient profiling in wheat (NARC-11). The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05. (b) Principle components analysis for nutrients profiling in wheat (NARC-11) at different iron nanoparticles concentration. Component 1 (PCA1) and component 2 (PCA2) demonstrated Mg and Fe contents showing highest variance. The nutritional profile of wheat highly influenced by Fe-NPs was Mg contents. The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

Micro-element contents influenced by targeting Fe-NPs on wheat (NARC-11)

| PC | Eigenvalue | % Variance | Eig 2.5% | Eig 97.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.82497 | 88.25 | 0 | 100 |

| 2 | 1.17276 | 11.728 | 0 | 66.118 |

| 3 | 0.00225 | 0.02252 | 0 | 100 |

| 4 | 2.46 × 10−5 | 0.00024556 | 0 | 100 |

| 5 | 2.70 × 10−7 | 2.70 × 10−6 | 0 | 3.03 × 10−6 |

Mg is represented by component 1 on the Y-axis, and iron is represented by component 2 on the X-axis. The PCA revealed that foliage sprays containing 20 and 30 mg·L−1 FeNPs were favorably correlated with Mg and Cu levels, but seed plus foliar containing 10 mg·L−1 was adversely correlated. Similarly, seed priming with iron nanoparticles demonstrated a lower correlation than other foliar and seed priming with Fe-NPs at varied doses (Figure 7b).

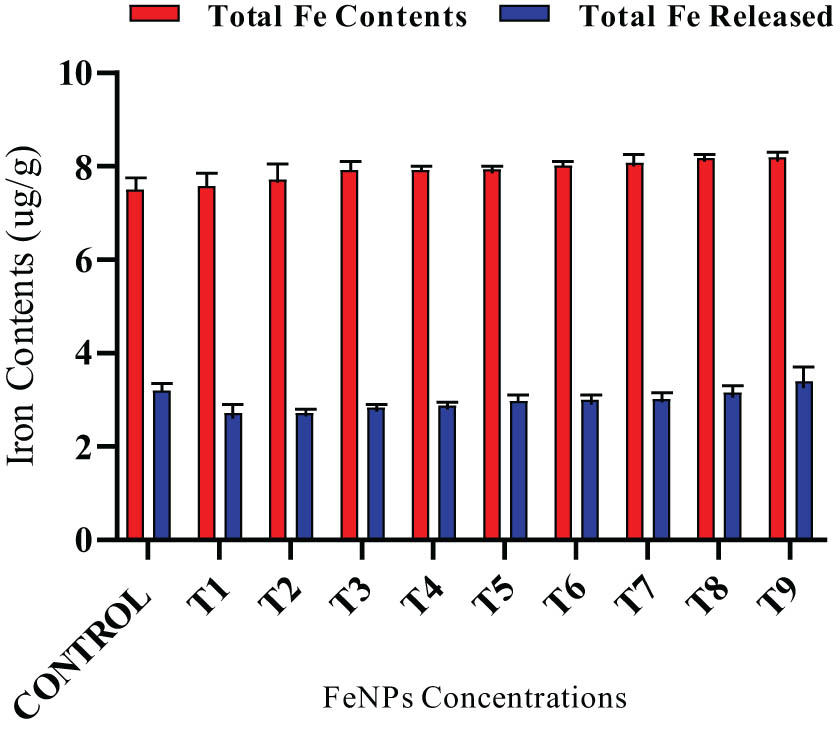

3.3.2 Iron released after in-vitro enzymatic digestion

Wheat flour/grains were subjected to in-vitro digestion with digestive enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin/bile, and trypsin) to check the effect on nutritional contents of iron sustain and was observed using ICP-OES. It was noted that 25–35% of iron contents were released from all the wheat samples upon in-vitro digestion. The higher amount of iron released was (3.4 µg·g−1) out of a total of 8.2 µg·g−1 present for 30 mg·L−1 seed priming along with foliar application, followed by 3.2 µg·g−1 out of a total of 7.25 µg·g−1 in control (Figure 8). The lowest iron was released at 20 mg·L−1 foliar nanoparticles applications when exposed to various digestive enzymes. The lowest release of iron contents from wheat flour/grains was thought to be the optimum concentration that minimize the release of iron contents from total iron contents. The results show that there is a fine amount of iron present in the digested wheat flour which would be bioaccessible to the human body as well.

Iron contents after in-vitro enzymatic digestion at various iron nanoparticle concentrations. The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

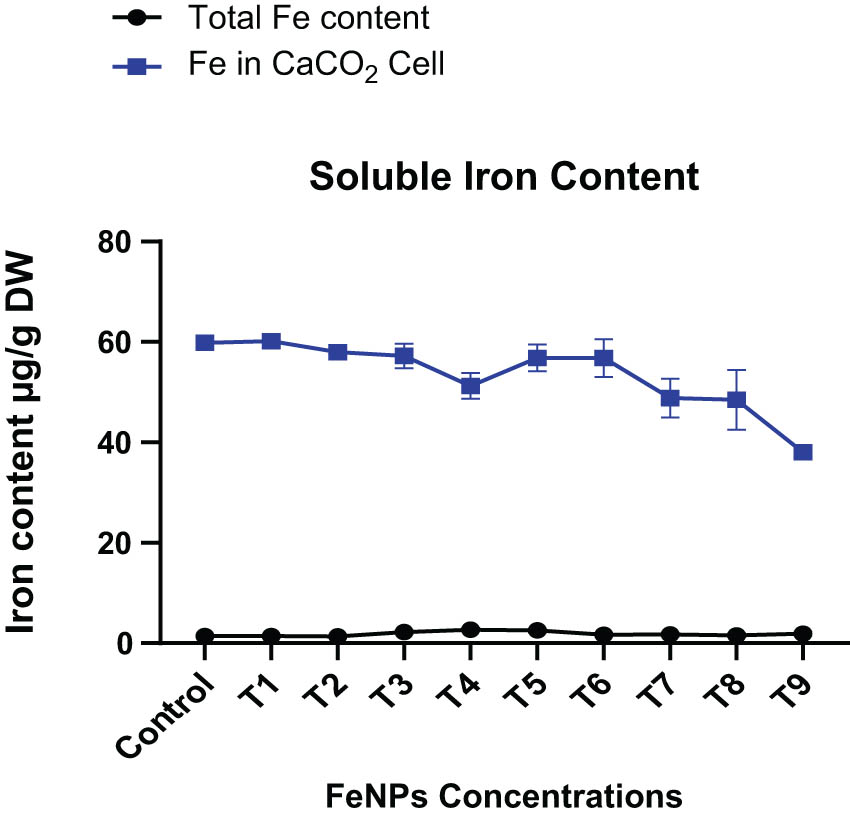

3.4 Bioavailability analysis of Fe after in-vitro enzymatic digestion using CaCO2 cells

3.4.1 Bioavailability of Fe after in-vitro enzymatic digestion

To determine the total iron contents or nutritional profile of wheat (NARC-11) flour after exposure to in-vitro enzymatic digestion, CaCO2 cells were used. To count nutritional contents different samples was applied to culture CaCO2 cells containing wheat untreated samples, treated with iron nanoparticles and sample containing digestive enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin/bile, and trypsin). Total iron contents in all wheat flour samples were observed using ICP-MS. It was noticed that a reduction of 18–28% in iron contents was by CaCO2 cells after in-vitro enzymatic digestion. Wheat (NARC-11) treatments with iron nanoparticles showed better results than enzymatic digestion (Figure 9). The significant amount of iron absorption (2.28 µg·g−1) in CaCO2 culture cells among a total of 9.28 µg·g−1 present at 20 ppm foliar, followed by 2.522 µg·g−1 among a total of 9.25 µg·g−1 at SF20 present in the sample.

Iron contents absorption by CaCO2 culture cells at various iron nanoparticle concentrations. The data in the graphs were expressed in terms of means ± SD, while the P value was kept <0.05.

4 Discussion

In the current research study, fresh leaves extract of Mentha arvensis was used for the synthesis of Fe-NPs. The UV–Vis spectroscopy validated the synthesis of Fe-NPs, with the maximum absorption peak obtained at 225 nm and a band gap energy of 1.1 eV. Khan et al. [38] found that iron oxide nanoparticles produced from Mentha spicata had an absorbance peak at 272 nm and an energy band of 2.23 eV. Additionally, the characterization method is utilized to determine the most engaged participating group in the stabilization of NPs and vibration of bonds and stretching of functional group in FTIR. The most increased functional group in the present research was the amide group, which showed an absorption spectrum at 801 nm. Earlier study outcome of Abdullah et al. [39] synthesized NPs from date palm demonstrated that mostly involved functional was the carboxylic group and hydrocarbon in the stabilization of nanoparticles. Moreover, SEM was also utilized to validate the creation of iron oxide nanoparticles, elemental profiling, and the construction of an intensity peak for an ionic component that acts as a capping agent. In our research study hydrogen and sulfur construct elevated peaks along with chlorine, zinc, cerium, phosphorus, and others, compared to the study of Kiwumulo et al. [40] on Moringa oleifera--based iron nanoparticles had the most participating ionic component was aluminum and sodium. The peak intensity, breadth, position, and even structure of nanoparticles are all determined by XRD. Mentha arvensis-based nanoparticles have shown variation in pattern-deficient diffraction peaks with irregular form in the current investigation. The comparison was done with the work of Seth et al. [41], who discovered a resemblance in the diffraction peak as well as a correlation with the amorphous shape of nanoparticles generated from Cheilanthes bicolor.

In the present research investigation, it was found that Fe-NPs significantly result in higher plant height by increasing water uptake from soil. A prior study conducted by Rizwan et al. [42] found a significant increase of 35% and 37% in plant height for wheat variety primed with a high dosage of 100 mg·L−1 (100 ppm) ZnO NPs and low dosage of 20 mg·L−1 (20 ppm) for Fe-NPs, respectively. Comparing the outcome of both studies shows that higher ZnO NPs and low dosages of iron nanoparticles had a positive impact on plant height. The current study found a modest increase in stem diameter in wheat (NARC-11) using a foliar method and a combined effect of seed priming followed by foliar treatments, whereas the results of Rizwan et al. [42], for stem diameter were similar, but the approach of nanoparticles was different, i.e., seed soaking.

At blooming, neither nanoparticle showed a significant difference. Likewise, a previous research investigation by Nandhini et al. [43] stated that employing plant-based zinc nanoparticles in aqueous extract of Eclipta alba induced no fast blossoming in flower when compared to control. Previous findings support the current outcomes on the day of blooming in the present study. In the current investigation, early maturity was under consideration after applying various concentrations of Fe-NPs to wheat variety (NARC-11), whereas a study performed by Siji et al. [44] determined that green iron nanoparticles generated using the marine algae Chaetomorpha antennia had no discernible influence on the maturity of pearl millet plants. In a recent study, it was noted that nutrient enrichment of wheat seeds was done by delivering NPs to crop plants shown marginally higher seeds weight than control plants. The finding was compared to previous research work performed by Yasmeen et al. [45], which elucidated that FeCl3 nanoparticles result in an increase in seed weight in wheat grains. Previous outcomes assist the consequence of the current research investigation.

It was also found that, in wheat variety (NARC-11) had favored higher chlorophyll accumulation after spraying iron nanoparticles that was interlinked to rise of sugar contents. An earlier finding of Sebastian et al. [46] showed that iron oxide nanoparticles improved chlorophyll concentration in Cd-stressed rice. Similarly, another research study outcome by Al-Amri et al. [47] confirmed that foliar application of Fe-NPs enhanced total chlorophyll contents in wheat. High proline accumulation in plants resulted to cope up plants from various stress situations. As plants were introduced to stress conditions by utilizing Fe-NPs plants in response elevate proline contents. Previously, Rout et al. [48] conducted a study on rice using iron salt of various concentrations and found that dosage creates toxicity and proline contents were higher at a smaller concentration of 100 mM. An earlier study shown different results for proline contents as compared to the current study.

In the current investigation, NP applications on wheat cause improvement in various biochemical parameters including proteins, carbohydrates, and total fiber contents. Tawfik et al. [49] reported that foliar spraying of iron oxide nanoparticles improves the nutritional profile of Moringa oleifera (5% total protein and 1.2% total fiber contents). The prior findings produced identical outcomes as the present research. Another study conducted by Bashir et al. [50], on rice line 3993, noted that mitochondrial iron transporter identified reduced chlorosis and synthesized specialized storage proteins in plants by boosting nutrient uptake from surrounding. An earlier study by Hasan et al. [51] supports the results of the current study for carbohydrates contents, showing that at 25 mg·L−1 carbohydrate contents increased and reduction was observed at 100 mg·L−1 FeO NPs in Zea mays. Another study by Wang et al. [52] reported that watermelon plants were treated with varying concentrations of Fe2O3 NPs, and there were no substantial differences in carbohydrate build-up when compared to control plants.

Wheat fortification targeted in recent work was done by treating with various concentrations of Fe-NP-enhanced mineral contents in crop plants. A study by Mohamed et al. [53] used high dosages (1 g·L−1) of Fe + Zn nanoparticles to enhance nutrients profile (N, K, P, Ca, Mg, and Zn) in faba bean. The study by Sahrawat [54], conducted work on rice varieties, found that deficiency in iron causes a reduction of other micro-nutrients to suck as Ca, Mn, and Mg. Hence, current results showed an increase in micro-nutrients as wheat grains were fortified using iron nanoparticles. Another finding of Briat et al. [55] confirmed that iron deficiency in rice may cause a reduction of copper in roots. An earlier study by Krejpcio et al. [56] supports the outcome of the current research study stating that digestion and extrusion processing dramatically boosted Fe release (by 127%), while substantially decreasing Zn and Cu liberation from lupine grains. Prior research findings of Bilal et al. [57] showed that the total release of iron content (4.1%) was lesser as compared to the present research study. Earlier findings of Christides et al. [37] evaluated that total iron nutrients used in CaCO2 cells had greater bio-availability as compared to the current study. Wang et al. [58] investigated the influence of three distinct nanoparticles on crop productivity and nutritional profile. Among them, TiONPs had little influence on plant growth and development; however, CuO NPs reduce iron and zinc micronutrients in wheat flour by boosting copper concentration by 30%, and iron oxide nanoparticles tremendously elevate wheat amino acid content.

5 Conclusions

Iron malnutrition is a significant global health issue that affects more than half of the population, especially in impoverished nations. Wheat is a major staple food crop in many countries, including Pakistan, and enhancing its nutritional value could be an effective strategy to address this issue. By utilizing the foliar application of iron nanoparticles, remarkable enhancements have been observed in the plant morphology, physiology, and nutritional profile of wheat (NARC-11). A remarkable improvement in plant height, stem diameter, 1,000 seed weight, early blooming, and maturation was achieved. The immense potential of this approach in enhancing crop yield and quality was observed. The present study reported that a remarkable increase in plant height of 2%, a considerable 25–40% increase in seed weight, and an accelerated maturation period of 7 days were observed in treated plants as compared to untreated. Wheat grains have shown an impressive increase (1–6%) in protein content, along with a notable 3% increase in crude fiber content, despite only a 0.9% reduction in crude fat content, these promising outcomes represent an advancement toward more sustainable and healthier food production. Interestingly, in an in-vitro study, wheat flour treated with proteolytic enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin, bile, and trypsin) can retain up to 30% Fe in its digested solution, as determined by ICP-OES.

-

Funding information: The article processing charge was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 491192747 and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

-

Author contributions: Ubaid ul Hassan: conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft and preparation, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization, project administration; Maarij Khan: validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing – original draft and preparation, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization; Zohaib Younas: methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing – original draft and preparation, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization; Naveed Iqbal Raja: conceptualization, validation, resources, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization, supervision; Zia ur Rehman Mashwani: conceptualization, software, validation, investigation, resources, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration; Sohail: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft and preparation, writing – reviewing and editing, visualization.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All obtained data are presented in this article.

References

[1] Iqbal M, Raja NI, Mashwani ZUR, Hussain M, Ejaz M, Yasmeen F, et al. Effect of silver nanoparticles on growth of wheat under heat stress. Iran J Sci Technol. 2019;43:387–95.10.1007/s40995-017-0417-4Search in Google Scholar

[2] Matres JM, Arcillas E, Cueto-Reaño MF, Sallan-Gonzales R, Trijatmiko KR, Slamet-Loedin I. Biofortification of rice grains for increased iron content. Rice Improv. 2021;5(3):471–8.10.1007/978-3-030-66530-2_14Search in Google Scholar

[3] Trumbo P, Yates AA, Schlicker S, Poos M. Dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(3):294.10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00078-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hoddinott J, Rosegrant M, Torero M. Investments to reduce hunger and undernutrition. Challenge Paper on Hunger and Malnutrition. Copenhagen Consensus Challenge Paper; 2012.10.1017/CBO9781139600484.008Search in Google Scholar

[5] Cakmak I, Kalayci M, Kaya Y, Torun AA, Aydin N, Wang Y, et al. Biofortification and localization of zinc in wheat grain. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(16):9092–102.10.1021/jf101197hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] García-Bañuelos ML, Sida-Arreola JP, Sánchez E. Biofortification-promising approach to increasing the content of iron and zinc in staple food crops. J Elementol. 2014;19(3):112–6.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Meenakshi JV, Johnson NL, Manyong VM, DeGroote H, Javelosa J, Yanggen DR, et al. How cost-effective is biofortification in combating micronutrient malnutrition? An ex ante assessment. World Dev. 2010;38(1):64–75.10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zou C, Du Y, Rashid A, Ram H, Savasli E, Pieterse PJ, et al. Simultaneous biofortification of wheat with zinc, iodine, selenium, and iron through foliar treatment of a micronutrient cocktail in six countries. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67(29):8096–106.10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01829Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Muthayya S, Rah JH, Sugimoto JD, Roos FF, Kraemer K, Black RE. The global hidden hunger indices and maps: An advocacy tool for action. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67860.10.1371/journal.pone.0067860Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Olson R, Gavin-Smith B, Ferraboschi C, Kraemer K. Food fortification: The advantages, disadvantages and lessons from sight and life programs. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1118.10.3390/nu13041118Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Alzaayid DTJ, Aloush RH. Effect of cytokinin levels on some varieties of wheat on yield, growth and yield components. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 910, No. 1, IOP Publishing; 2021. p. 012090.10.1088/1755-1315/910/1/012090Search in Google Scholar

[12] Pandey M, Shrestha J, Subedi S, Shah KK. Role of nutrients in wheat: A review. Trop Agrobiodivers. 2020;1(1):18–23.10.26480/trab.01.2020.18.23Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ullah I, Ali N, Durrani S, Shabaz MA, Hafeez A, Ameer H, et al. Effect of different nitrogen levels on growth, yield and yield contributing attributes of wheat. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2018;9:595–602.10.14299/ijser.2018.09.01Search in Google Scholar

[14] Adhikari M, Adhikari NR, Sharma S, Gairhe J, Bhandari RR, Paudel S. Evaluation of drought tolerant rice cultivars using drought tolerant indices under water stress and irrigated condition. Am J Clim Change. 2019;8(2):228–36.10.4236/ajcc.2019.82013Search in Google Scholar

[15] Sheoran S, Raj D, Antil RS, Mor VS, Dahiya DS. Productivity, seed quality and nutrient use efficiency of wheat (Triticum aestivum) under organic, inorganic and integrated nutrient management practices after twenty years of fertilization. Cereal Res Commun. 2017;45:315–25.10.1556/0806.45.2017.014Search in Google Scholar

[16] Bathla S, Arora S. Prevalence and approaches to manage iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;62(1):1–14. 10.1080/10408398.2021.1935442.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Blanco-Rojo R, Vaquero MP. Iron bioavailability from food fortification to precision nutrition. A review. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2019;51:126–38.10.1016/j.ifset.2018.04.015Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kumari A, Chauhan AK. Iron nanoparticles as a promising compound for food fortification in iron deficiency anemia: A review. J Food Sci Technol. 2022;59(9):3319–35.10.1007/s13197-021-05184-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Singh R, Dutt S, Sharma P, Sundramoorthy AK, Dubey A, Singh A, et al. Future of nanotechnology in food industry: Challenges in processing, packaging, and food safety. Glob Chall. 2023;7(4):2200209.10.1002/gch2.202200209Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Wani SH, Gaikwad K, Razzaq A, Samantara K, Kumar M, Govindan V. Improving zinc and iron biofortification in wheat through genomics approaches. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(8):8007–23.10.1007/s11033-022-07326-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Amiri R, Bahraminejad S, Sasani S, Jalali-Honarmand S, Fakhri R. Bread wheat genetic variation for grain’s protein, iron and zinc concentrations as uptake by their genetic ability. Eur J Agron. 2015;67:20–6.10.1016/j.eja.2015.03.004Search in Google Scholar

[22] Rui M, Ma C, Hao Y, Guo J, Rui Y, Tang X, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles as a potential iron fertilizer for peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:815.10.3389/fpls.2016.00815Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Rai P, Sharma S, Tripathi S, Prakash V, Tiwari K, Suri S, et al. Nanoiron: Uptake, translocation and accumulation in plant systems. Plant Nano Biol. 2022;3(2):100017.10.1016/j.plana.2022.100017Search in Google Scholar

[24] Prajapati HR, Devi R. Intensive farming, land degradation and food security issues in India. AKADEMOS. 2018;313–9.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Vasil IK. Molecular genetic improvement of cereals: Transgenic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26(8):1133–54.10.1007/s00299-007-0338-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Bukhari MA, Ahmad Z, Ashraf MY, Afzal M, Nawaz F, Nafees M, et al. Silicon mitigates drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) through improving photosynthetic pigments, biochemical and yield characters. Silicon. 2021;13(12):4757–72.10.1007/s12633-020-00797-4Search in Google Scholar

[27] Connorton JM, Balk J. Iron biofortification of staple crops: lessons and challenges in plant genetics. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019;60(7):1447–56.10.1093/pcp/pcz079Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Feng Y, Kreslavski VD, Shmarev AN, Ivanov AA, Zharmukhamedov SK, Kosobryukhov A, et al. Effects of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) on growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant activity and distribution of mineral elements in wheat (Triticum aestivum) Plants. Plants. 2022;11(14):1894.10.3390/plants11141894Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Ali A, Zafar H, Zia M, Ul-Haq I, Phull AR, Ali JS, et al. Synthesis, characterization, applications, and challenges of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2016;9:49.10.2147/NSA.S99986Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Mashwani ZUR, Khan T, Khan MA, Nadhman A. Synthesis in plants and plant extracts of silver nanoparticles with potent antimicrobial properties: current status and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(23):9923–34.10.1007/s00253-015-6987-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Mohan AC, Renjanadevi B. Preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles and its characterization using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Procedia Technol. 2016;24:761–6.10.1016/j.protcy.2016.05.078Search in Google Scholar

[32] Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24(1):1.10.1104/pp.24.1.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare I. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant soil. 1973;39(1):205–7.10.1007/BF00018060Search in Google Scholar

[34] Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PT, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–6.10.1021/ac60111a017Search in Google Scholar

[35] Feldsine P, Abeyta C, Andrews WH. AOAC International methods committee guidelines for validation of qualitative and quantitative food microbiological official methods of analysis. J AOAC Int. 2002;85(5):1187–200.10.1093/jaoac/85.5.1187Search in Google Scholar

[36] Shi R, Zhang Y, Chen X, Sun Q, Zhang F, Römheld V, et al. Influence of long-term nitrogen fertilization on micronutrient density in grain of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Cereal Sci. 2010;51(1):165–70.10.1016/j.jcs.2009.11.008Search in Google Scholar

[37] Christides T, Wray D, McBride R, Fairweather R, Sharp P. Iron bioavailability from commercially available iron supplements. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54(8):1345–52.10.1007/s00394-014-0815-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Khan S, Bibi G, Dilbar S, Iqbal A, Ahmad M, Ali A, et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles from Mentha spicata and screening its combating potential against Phytophthora infestans. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13(1):1001499.10.3389/fpls.2022.1001499Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Abdullah JAA, Eddine LS, Abderrhmane B, Alonso-González M, Guerrero A, Romero A. Green synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles by pheonix dactylifera leaf extract and evaluation of their antioxidant activity. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2020;17(1):100280.10.1016/j.scp.2020.100280Search in Google Scholar

[40] Kiwumulo HF, Muwonge H, Ibingira C, Lubwama M, Kirabira JB, Ssekitoleko RT. Green synthesis and characterization of iron-oxide nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera: a potential protocol for use in low and middle income countries. BMC Res Notes. 2022;15(1):1–8.10.1186/s13104-022-06039-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Seth A, Devi E, Thakur K, Attri C, Singh V, Bhandari A, et al. Himalayan fern cheilanthes bicolor mediated fabrication and characterization of iron nanoparticles with antimicrobial potential. BioNanoScience. 2022;12(2):486–95.10.1007/s12668-022-00969-zSearch in Google Scholar

[42] Rizwan M, Ali S, Ali B, Adrees M, Arshad M, Hussain A, et al. Zinc and iron oxide nanoparticles improved the plant growth and reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat. Chemosphere. 2019;214:269–77.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.120Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Nandhini M, Rajini SB, Udayashankar AC, Niranjana SR, Lund OS, Shetty HS, et al. Biofabricated zinc oxide nanoparticles as an eco-friendly alternative for growth promotion and management of downy mildew of pearl millet. Crop Prot. 2019;121:103–12.10.1016/j.cropro.2019.03.015Search in Google Scholar

[44] Siji S, Njana J, Amrita PJ, Raj A, Vishnudasan D, Manoj PK. Green synthesized iron nanoparticles and its uptake in pennisetum glaucum—A nanonutriomics approach. In: 2017 International Conference on Technological Advancements in Power and Energy (TAP Energy). IEEE; 2017.10.1109/TAPENERGY.2017.8397338Search in Google Scholar

[45] Yasmeen F, Raja NI, Razzaq A, Komatsu S. Proteomic and physiological analyses of wheat seeds exposed to copper and iron nanoparticles. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2017;1865(1):28–42.10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.10.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Sebastian A, Nangia A, Prasad M. A green synthetic route to phenolics fabricated magnetite nanoparticles from coconut husk extract: Implications to treat metal contaminated water and heavy metal stress in Oryza sativa L. J Clean Prod. 2018;174:355–66.10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.343Search in Google Scholar

[47] Al-Amri N, Tombuloglu H, Slimani Y, Akhtar S, Barghouthi M, Almessiere M, et al. Size effect of iron (III) oxide nanomaterials on the growth, and their uptake and translocation in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;194:110377.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110377Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Rout G, Sunita S, Das AB, Das SR. Screening of iron toxicity in rice genotypes on the basis of morphological, physiological and biochemical analysis. J Exp Biol Agric Sci. 2014;2(6):567–82.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Tawfik MM, Mohamed MH, Sadak MS, Thalooth AT. Iron oxide nanoparticles effect on growth, physiological traits and nutritional contents of Moringa oleifera grown in saline environment. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2021;45(1):1–9.10.1186/s42269-021-00624-9Search in Google Scholar

[50] Bashir K, Ishimaru Y, Shimo H, Nagasaka S, Fujimoto M, Takanashi H, et al. The rice mitochondrial iron transporter is essential for plant growth. Nat Commun. 2011;2(1):1–7.10.1038/ncomms1326Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Hasan M, Rafique S, Zafar A, Loomba S, Khan R, Hassan SG, et al. Physiological and anti-oxidative response of biologically and chemically synthesized iron oxide: Zea mays a case study. Heliyon. 2020;6(8):e04595.10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04595Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Wang Y, Hu J, Dai Z, Li J, Huang J. In vitro assessment of physiological changes of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) upon iron oxide nanoparticles exposure. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;108:353–60.10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.08.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Mohamed HI, Elsherbiny EA, Abdelhamid MT. Physiological and biochemical responses of Vicia faba plants to foliar application of zinc and iron. Gesunde Pflanz. 2016;68(4):201–12.10.1007/s10343-016-0378-0Search in Google Scholar

[54] Sahrawat KA. Iron toxicity in wetland rice and the role of other nutrients. J Plant Nutr. 2005;27(8):1471–504.10.1081/PLN-200025869Search in Google Scholar

[55] Briat JF, Fobis‐Loisy I, Grignon N, Lobréaux S, Pascal N, Savino G, et al. Cellular and molecular aspects of iron metabolism in plants. Biol Cell. 1995;84(1–2):69–81.10.1016/0248-4900(96)81320-7Search in Google Scholar

[56] Krejpcio Z, Lampart-Szczapa E, Suliburska J, Wójciak RW, Hoffman A. Effect of technological processes on the release of copper, iron and zinc from lupine grain preparations (Lupinus albus Butan var.) in in vitro enzymatic digestion. Feb. 2009;18(10):1923–6.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Bilal R, Roohi S, Ahmad T, Trinidad TP. Iron fortification of wheat flour: Bioavailability studies. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(3):199–202.10.1177/15648265020233S139Search in Google Scholar

[58] Wang Y, Jiang F, Ma C, Rui Y, Tsang DC, Xing B. Effect of metal oxide nanoparticles on amino acids in wheat grains (Triticum aestivum) in a life cycle study. J Environ Manag. 2019;241:319–27.10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.041Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic