Abstract

The study synthesized Pluronic F-127 nanoparticles that encapsulate Fe2O3 (PF127Fe2O3NPs), nanoparticles, characterized their formation, and evaluated their cytotoxicity and anticancer activity using Berberis vulgaris leaf extract, using various analytical methods such as FTIR, Ultraviolet-visible, photoluminescence, dynamic light scattering, X-ray diffraction, and morphology analysis. We assessed the antioxidant properties of PF127Fe2O3NPs, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis through 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay and acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining in breast cancer cells, such as MCF7, and MDA-MB-231. The characterization results demonstrated that PF-127 was coated with Fe2O3 nanoparticles. MTT assay data revealed that PF127Fe2O3NPs effectively prevent cancer cells from proliferating and act as an anticancer drug. The antimicrobial results revealed that the fabricated nanoparticles are effective against gram-negative (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Shigella dysenteriae) and gram-positive (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis) bacteria. Treatment of PF127Fe2O3NPs in a dose-dependent manner on MCF7, and MDA-MB-231, exhibited increased antioxidant activity, nuclear damage, and apoptotic activity. These results confirm the apoptotic activity of PF127Fe2O3NPs. The study concludes that MCF7 appears to be more sensitive to PF127Fe2O3NPs than MDA-MB-231. In conclusion, we have found that it can be used as an effective antioxidant and anticancer agent in therapeutics.

1 Introduction

As an alternative to their enormous materials, nanoparticles are now being studied for a varied diversity of reasons and have enhanced biological activity due to their small size, high surface-to-volume ratio, and ability to change size and shape [1]. Nanoparticles are currently made using several physicochemical techniques for various applications, such as biological sensors, solar cells, agriculture, and textiles [2]. Their usage in the biological and medical domains is constrained due to the use of hazardous chemicals, the difficulty of the synthesis process, the high pricing, and the creation of dangerous by-products [3].

In a green way to generate nanoparticles, plant extracts are used to generate nanoparticles that are easy, fast, and do not contain toxic or high-energy substances. Additionally, diverse proteins found in microbes and plant extracts serve as capping agents, allowing the creation of nanoparticles to be scaled up [4]. The use of plant extracts has some perks over the utilization of microorganisms among the various organisms that are used to produce nanoparticles, such as the absence of the need for culture media or other challenges associated with the use of microorganisms for nanoparticle production, such as the need for aseptic conditions [5]. The utilization of plants is now one of the most dependable processes for synthesizing nanoparticles due to the usage of biomaterials, green, and ease of synthesis [6]. Plant extracts include coating and reducing substances such as polysaccharides, amino acids, flavonoids, terpenes, enzymes, and proteins. These substances may generate nanoparticles with remarkable stability and a variety of sizes and forms by reducing metal ions [7].

Recent years have seen a plethora of basic and medicinal uses for magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4, γ-Fe2O3, α-Fe2O3, and FeO). Hematite (α-Fe2O3), a more stable form of iron oxide than other polymorphs, has a range of useful technological uses due to its low cost, superior chemical stability, anti-corrosive, tuneable optical, and magnetic characteristics [8]. Iron oxide nanoparticles have gained much attention because of their distinct physiochemical characteristics. Using green chemistry, plants can generate iron oxide nanoparticles, which is a revolutionary way that gets beyond the drawbacks of existing traditional approaches. In this green route of the fabrication process, the biomolecules of plants serve as capping and reducing agents [9]. These therapeutic efficacies are due to the bioactive components that are affixed to the NPs’ surface. These characteristics are also connected to the biological uses of NPs. In the combat against oxidative stress, the weakly radical scavenging action is efficient [10]. Additionally, ROS may be transported into bacteria via iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles, which disrupts the functionality of the cell membrane and causes the leaking of cellular components, which may induce bacterial cell death [11].

Traditional medicine places a special emphasis on therapeutic herbs from the genus Berberis. Several studies have reported that among distinct Berberis species, the Berberis vulgaris plant has pharmaceutical, antioxidant, and nutritional properties [12]. The different organs of this plant contain several alkaloids, the most significant of which is berberine. This alkaloid can have a variety of effects, including anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, antioxidant, and hypotensive properties [13]. The culinary and pharmaceutical sectors employ various B. vulgaris organs, while the ornamental species are used to beautify various locations. Traditional medicine recommends using B. vulgaris to treat liver illness, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, depression, and bleeding [14]. According to the findings, B. vulgaris includes a substantial number of phytochemical substances, including more than ten phenolic compounds, vitamin K, ascorbic acid, a variety of triterpenoids, and more than thirty alkaloids [15]. Consequently, B. vulgaris may have benefits that are antioxidant, analgesic, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory [12].

Recent research has focused heavily on the surface modification of nanoparticles by polymers to diminish aggregation, regulate their physicochemical characteristics, and regulate their links with biological systems [16]. The polymer can increase the nanoparticles’ stability in the cellular environment and improve their biocompatibility with healthy, normal live cells and organs [17]. As a surfactant polyol, Pluronic F127 exhibits a low toxicity that allows it to be used to control drug release while also facilitating the solubilization of water-insoluble materials in physiological media, as well as acting as an absorption promoter that improves drug permeability across ocular epithelia [18]. A commercially available FDA-approved triblock copolymer called Pluronic F-127 is among these polymers. It is injectable, nontoxic, biocompatible, and thermo-reversible [19]. It can exhibit amphiphilic properties in an aqueous environment. Pluronic F-127 is ideally suited for gene therapy, controlled release, drug administration, and tissue engineering because of its unique thermo-reversible micellization property near body temperature [20].

The results showed that both synthesized FeO-NPs displayed 100% antimicrobial photodynamic therapy activity after light-emitting diode irradiation. The water extract of FeO-NPs and methanol extract of FeO-NPs also showed significant biofilm inhibition [21]. The study synthesized hematite nanoparticles using Artemisia plant extract, achieving a saturated magnetization of 0.96 emu·g−1 and a low remnant magnetization of 0.06 emu·g−1, indicating potential biomedical applications [22]. The study reveals that green iron nanoparticles with high adsorption capacity are promising for industrial applications. Clove-prepared iron nanoparticles showed more effective bactericidal activity against pathogens than g-Coffee-prepared ones, with Clove-prepared iron oxide inhibiting Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli at different depths [23]. The study showcases the green synthesis of Fe2O3 nanoparticles from Bauhinia tomentosa leaf extract, demonstrating their effectiveness in lipase immobilization and 1,3-diolein synthesis [24].

In this work, Pluronic F-127-coated Fe2O3 NPs were prepared using a novel, environmentally friendly method, and their characterization studies including ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), dynamic light scattering (DLS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), photoluminescence (PL), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with EDAX, and transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis were performed. In addition, the antibacterial biological cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity of fabricated Pluronic F-127-coated Fe2O3 NPs were assessed for the first time to our knowledge. Fe2O3 NP’s stability and biocompatibility have been markedly enhanced by the modification method while also maintaining their preferred crystalline form.

2 Materials and methodology

2.1 Preparation of B. vulgaris extract

A freshly harvested B. vulgaris plant, authenticated by the Botanical Survey of India (11.6653454; 78.280684), weighed 10 g and was soaked in 100 mL of demineralized water for 20 min at 80°C. Using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, the resulting extraction was purified. The filtrate was then stored in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask and kept at 37℃ for further processing.

2.2 Preparation of Fe2O3 NPs

To synthesize Fe2O3 NPs, 0.5 g of Pluronic F-127 and 0.1 M of ferrous nitrate hexahydrate Fe(NO3)2·6H2O were mixed in 100 mL of prepared Berberis vulgaris extract. This resulted in a red-colored homogenous reaction mixture. This mixture was continuously agitated for 5 h at a temperature of 80℃. At 120°C for 1 h, the resulting crimson precipitate was dried. For further research, the obtained Fe2O3 NPs in powder state were annealed at a temperature of 800°C for 5 h.

2.3 UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

UV-Vis spectroscopy was used to identify the surface plasmon resonance peak in the Fe2O3 nanoparticle. Analyzed nanoparticle samples were carried out at wavelengths ranging from 200 to 1,100 nm. To calculate the average absorbance of the Fe2O3 nanoparticle, the experiment was carried out three times.

2.4 Analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs by DLS

The Fe2O3 nanoparticle was examined using DLS. The nanoparticles were first homogenized with Milli-Q water, and then the mixture was subjected to 30 s of sonication. Nanoparticles are diluted 1:10 with Milli-Q water before undergoing a zeta potential test.

2.5 Analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs with field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and EDAX

FESEM coupled with EDAX was used to examine the composition, size, and surface properties of the fabricated Fe2O3 nanoparticle.

2.6 TEM analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

The TEM (Tecnai F20 model) apparatus was used to analyze the morphologies of the PF127Fe2O3NPs at a 200 kV accelerating voltage.

2.7 XRD analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

An XRD was used to analyze the PF127Fe2O3NPs. When the monochromatic wavelength of 1.54 Å was employed, the diffraction patterns for the PF127Fe2O3NPs were recorded in the 20°–80° range.

2.8 FTIR spectroscopic analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

Investigation of the different functional groups present in Fe2O3 NPs was done using FTIR analysis. Potassium bromide pellets and Fe2O3 NPs were mixed in a 1:100 ratio before being scanned at a resolution of 4 cm, each scan between 500 and 4,000 cm−1. The program was used to perform and assess 50 scans in total.

2.9 PL analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

The electronic structure and characteristics of the PF127 Fe2O3NPs were assessed using photoluminescence spectroscopy (Cary Eclipse spectrometer).

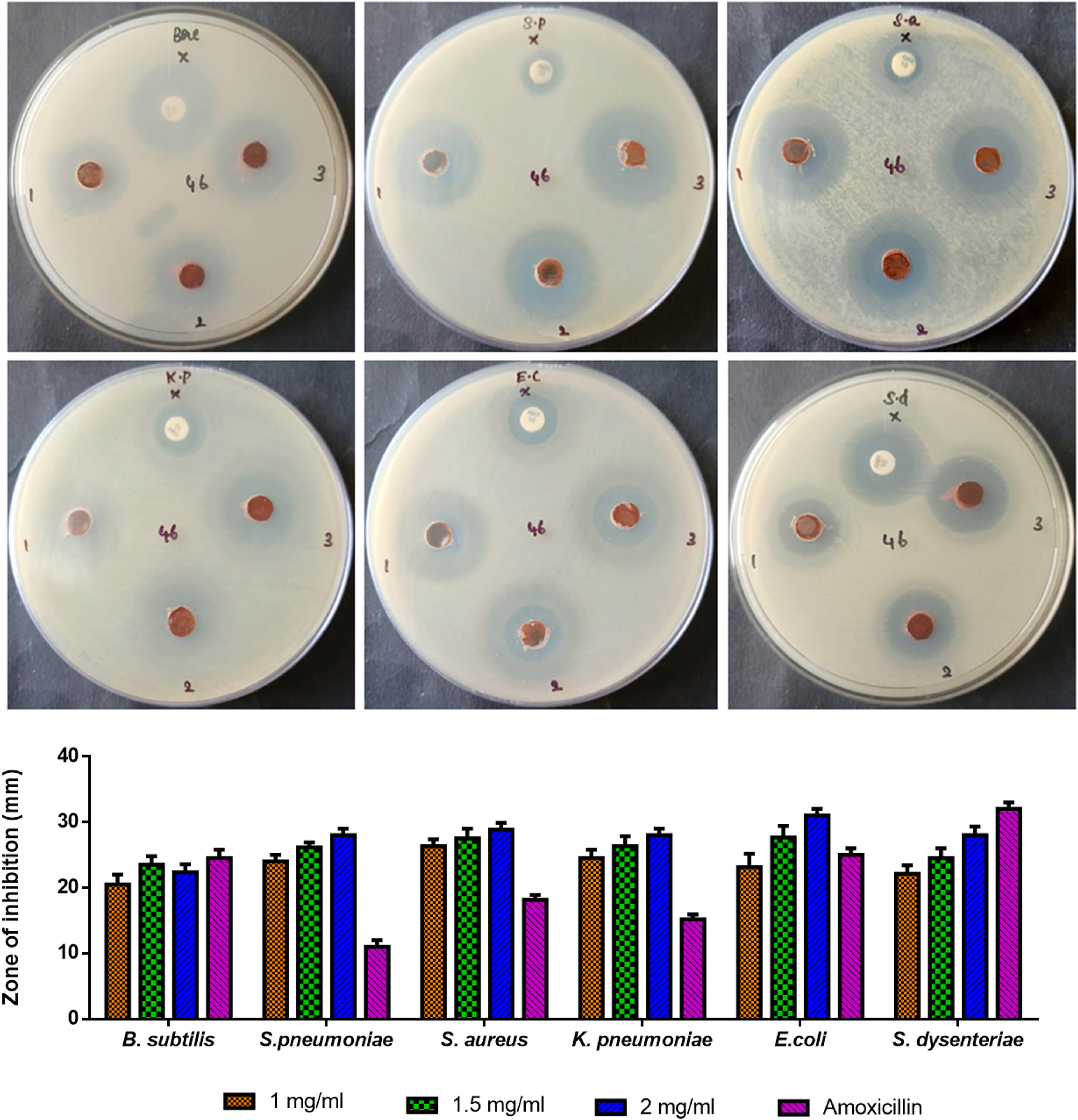

2.10 Determination of antibacterial potential of PF127 Fe2O3NPs

The antibacterial activity of the PF127Fe2O3NPs was examined by the well diffusion technique and tested against Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, E. coli, and Shigella dysenteriae following molten nutritional agar. Micropipettes were used to transfer test samples at concentrations of 1, 1.5, and 2 mg·mL−1 onto the bacteria-seeded well plates. Following that, the plates were incubated at 37℃ for a duration of 24 h. The inhibition zone’s dimensions were taken. The positive control against B. subtilis, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. dysenteriae was amoxicillin (Hi-Media) [21].

2.11 Estimation of in vitro antioxidant activity of PF127 Fe2O3NPs

The antioxidant capability of the Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles was studied by 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity. Each test is carried out three times. Several concentrations of Fe2O3 NP solution (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 µg·mL−1) were mixed with an equivalent volume of 0.1 mM DPPH solution. The reaction mixture’s absorbance at 517 nm was measured after it had been incubated for a duration of 30 min at 37°C and in the dark. The application of ascorbic acid as the benchmark and ethanol (blank) as the positive control. It is proof of antioxidants’ ability to scavenge free radicals that the absorbance of the DPPH mixed reaction mixture reduced when the antioxidant was introduced. The percentage of free radicals that were suppressed or scavenged was calculated using the following formula:

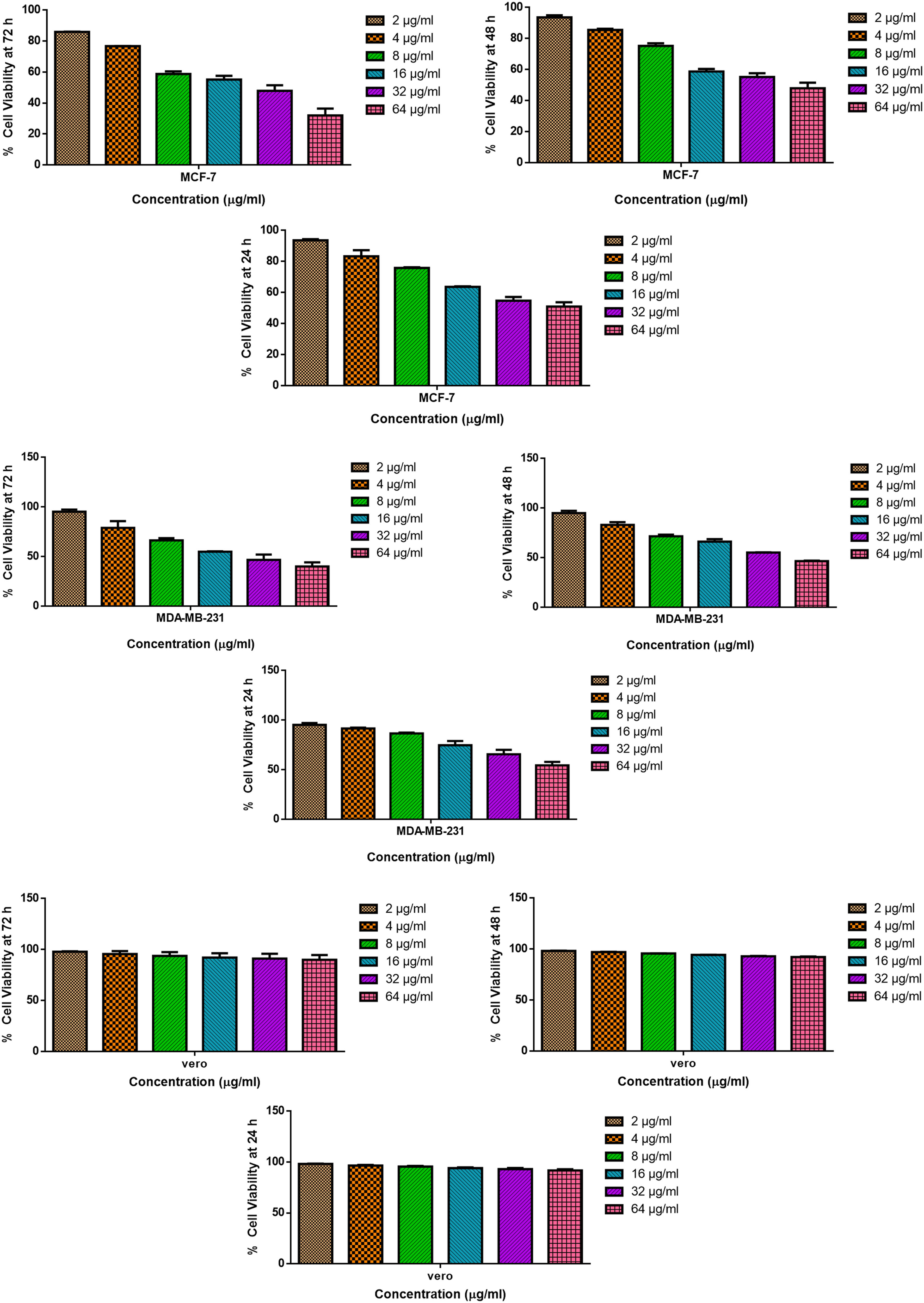

2.12 Cell viability assay

The study used Vero (normal), MDA MB-231, and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines to assess PF127Fe2O3NPs cytotoxicity based on Sarathbabu et al. [22]. Cells were seeded onto 96-well tissue culture plates and incubated with Fe2O3 NPs for 24, 48, and 72 h at room temperature and 5% CO2. After incubation, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added for 2–4 h until purple crystallites appeared. Cells were drained and cleaned with 1× PBS. Viability percentage and IC50 value were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

2.13 Statistical analysis

Each study was conducted in triplicate, and the results were statistically analyzed using One-way ANOVA and a post hoc Tukey post-test. The results were presented as mean ± SD, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UV-Vis spectra of PF127Fe2O3NPs

From the highest occupied molecular orbital in the valence band (VB) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital in the conduction band (CB), electrons are excited by the absorption of electromagnetic waves. By absorbing wavelengths between bonding and anti-bonding orbitals, the substance’s band gap energy can be determined. The three probable electronic transitions between 200 and 1,000 nm are n → π, n → σ*, and π → π* [23]. With a UV-Vis spectrophotometer operating at room temperature, the optical absorbance of Fe2O3 nanoparticles was examined; the corresponding spectrum is shown in Figure 1. Using UV-Vis spectroscopy, it is possible to determine if precursor reduction has been placed. The presence of Fe2O3 NPs is indicated by a high absorption peak at 395 nm [24]. The absorption bands observed at 395 nm are caused by the ligand-to-metal charge-transfer transitions (direct transitions), with coupled effects from the Fe3+ ligand field transitions [25].

UV-Vis spectrophotometer analysis of synthesized Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. Fe2O3 nanoparticles coated with Pluronic F-127 and analyzed with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

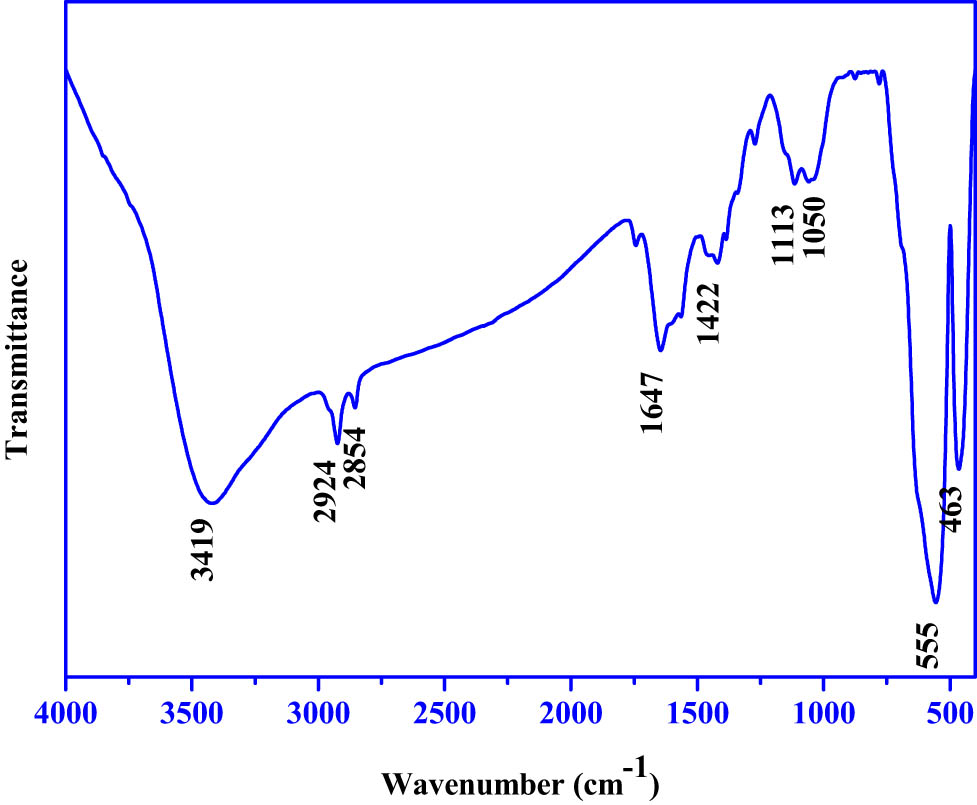

3.2 FTIR spectra of PF127Fe2O3NPs

The B. vulgaris extract used to make Fe2O3 NPs was subjected to FTIR examinations to look for any potential modifications in functional group bonds that could have occurred through the reduction process. Figure 2 illustrates the FTIR spectrum for PF127Fe2O3NPs mediated by B. vulgaris extract, which showed multiple distinct bands at 463, 555, 1,050, 1,113, 1,422, 1,647, 2,854, 2,924, and 3,419 cm−1, respectively. B. vulgaris extract has a shifted absorption band at 555 cm−1, and the band at 463 cm−1 matches the Fe–O stretch of Fe2O3, demonstrating the synthesis of Fe2O3 NPs. The intensity of the detected absorption bands exceeded those of the extract, demonstrating the extract’s reducing function in forming Fe2O3 NPs. The peak at 1,113 cm−1 represents the stretching vibration of the C–O–C present in the polyphenolic chemicals that are found in the plant extract. The in-plane bending vibrations of O–H in phenols correspond to the band obtained at 1,422 cm−1. The polyphenol chemicals found in the plant extract and the amino acids that stabilized and served as a capping agent are shown by the absorption band at 1,647 cm−1, which is related to the C═O bond stretching. To reduce iron ions and iron oxide nanoparticles, polyphenol compounds and phenyl groups are crucial [26,27]. C–H stretching peaks present in Pluronic F-127 were seen at 2,924 and 2,854 cm−1, respectively. The band with the maximum intensity that is ascribed to the O–H groups is an indication that the surface of the manufactured Fe2O3 NPs has been coated with water-soluble polyphenol compounds. With an enhanced absorption band, the ferric chloride reduction is shown by the band at 3,419 cm1, which corresponds to the O–H bond stretching and identifies the aqueous phase [28,29].

FTIR analysis of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs derived from infrared analysis. Based on infrared analysis, FTIR transmission vs wavenumber of pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 nanoparticles is depicted in the chart.

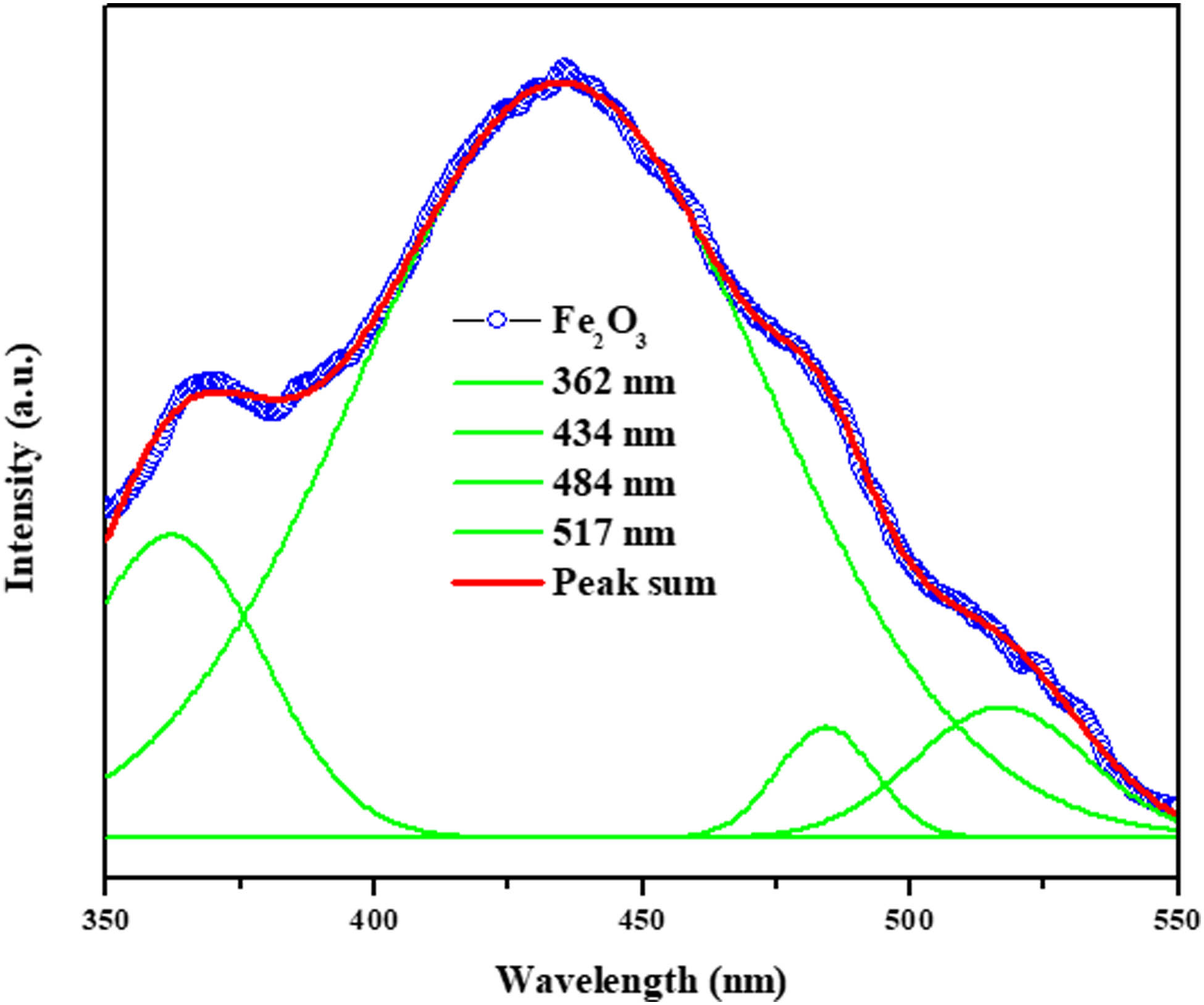

3.3 PL spectra of PF127Fe2O3NPs

A key method for assessing the optical characteristics of electronic materials is PL analysis. Fabricated Fe2O3 NPs’ PL spectra at room temperature are depicted in Figure 3 and stimulated at a wavelength of 325 nm (Figure 3). The PF127Fe2O3NPs’ PL emission spectra showed values at 362, 434, 484, and 512 nm, respectively. The VB and CB are excited, resulting in 362 nm UV emission. Excitons and holes flow freely in CB and VB, generating excitons. Blue emission at 434 and 484 nm is caused by electron and hole recombination, while green emission at 512 nm is caused by ionized oxygen vacancies and structural flaws in Fe2O3 NPs [30,31,32].

PL spectroscopy spectrum of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. Fe2O3 nanoparticles coated with Pluronic F-127 and their PL spectrum.

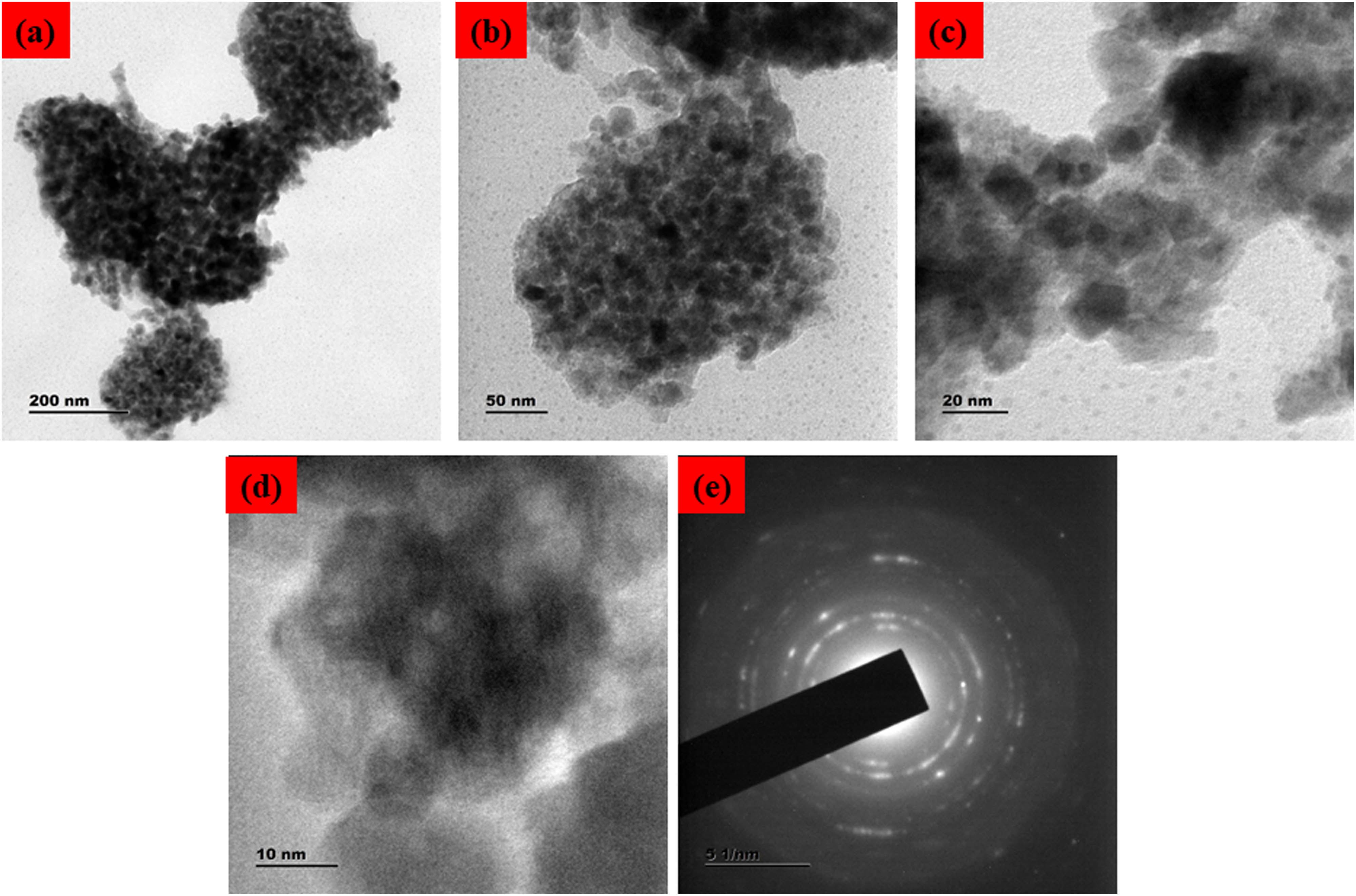

3.4 Morphological analysis of PF127Fe2O3NPs

Nanostructured hematite particles’ shape, size, and crystallinity were confirmed using TEM imaging and Selected area (electron) diffraction [SAED] pattern analysis, revealing spherical structure (Figure 4(a–d)). To further demonstrate the crystallinity of the distinct little bright and pointed dots that make up the ring, which is coated with Pluronic F-127. The SAED pattern confirmed the rhombohedral crystalline phase of the produced Fe2O3 NPs (Figure 4e). This agrees with XRD data and TEM micrographs that demonstrate that all the particles are nanoscale in size.

TEM micrographics of the Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs: lower (a, b) and higher (c, d) magnification TEM image and SAED pattern (d). PF127Fe2O3NPs TEM study monitored Fe2O3 NPs’ shape, with particle sizes ranging from 30 to 50 nm.

3.5 FESEM analysis and EDAX spectra of PF127Fe2O3NPs

The PF127Fe2O3NPs were synthesized using Berberis vulgaris extract at room temperature utilizing a green approach. The PF127Fe2O3NPs SEM study monitored Fe2O3 NPs’ shape, and the particle size ranged from 35 to 55 nm. According to Figure 5(a and b), the particles were agglomerated and spherical. The presence of biological substances on the surface of the particles may be the cause of the agglomeration. The particles seem to aggregate because bioactive chemicals had OH bonding, which makes this possible (Figure 5c) [33,34,35].

FESEM image of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. Lower (a) and higher (b) magnification. Elements, weight %, and atomic % of the composition obtained by EDX (c).

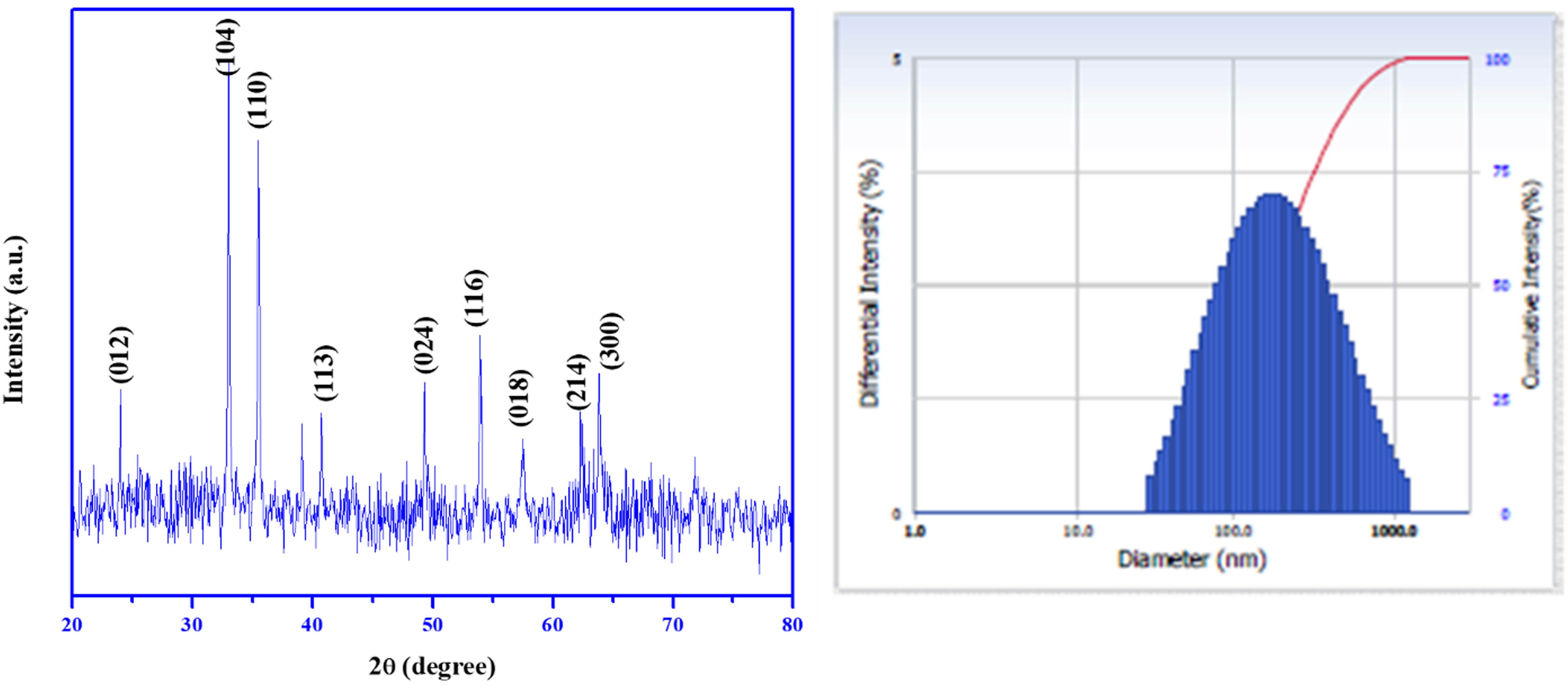

3.6 X-ray diffraction patterns of PF127Fe2O3NPs

Figure 6 displays the XRD spectrum of the green route fabricated PF127Fe2O3NPs. The generation of α-Fe2O3 NPs was indicated by well-defined peak locations in the XRD spectra with 2θ values of (012), (104), (110), (113), (024), (116), and (018) corresponding to the 25.160°, 35.120°, 36.630°, 40.640°, 49.970°, 57.080°, and 59.420°. The crystalline nature of the Fe2O3 NPs produced by the reduction technique utilizing B. vulgaris extract was unquestionably demonstrated by the strong and crisp peaks. The findings nearly exactly match those of other researchers who studied iron oxide nanoparticles [26,36], supporting the creation of a crystalline rhombohedral structure. According to the Debye–Scherrer equation [26], the average crystallite size of synthetic PF127Fe2O3NPs was 32.54 nm. The computed lattice parameters are a = 0.506 nm and c = 1.388 nm. The absence of additional diffraction peaks suggests that the PF127Fe2O3NPs produced by green synthesis were very pure and had high crystallinity.

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) pattern and DLS Spectrum of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. Fe2O3 NPs coated with Pluronic F-127 and their XRD patterns and DLS spectra.

3.7 DLS spectra of PF127Fe2O3NPs

Figure 6 displays the particle size distributions for PF127Fe2O3NPs. The average diameter of the particles after 800°C annealing is 174.90 nm. The build-up of primary particles results in an expansion in the mean particle size.

3.8 Antibacterial effect of PF127Fe2O3NPs

The antibacterial activity and zone of inhibition of fabricated PF127Fe2O3NPs are depicted in Figure 7. PF127Fe2O3NPs exhibit antibacterial activity against bacterial strains including B. subtilis, S. pneumonia, E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumonia, and S. dysenteriae bacterial strains. Amoxicillin samples and fabricated PF127Fe2O3NPs both demonstrate antibacterial activity. PF127Fe2O3NPs have a stronger antibacterial effect as compared to amoxicillin. Additionally, the antimicrobial activity increased as NP concentration was raised. The fact that Fe2O3 NPs are highly stable in the ambient environment, indicating that metal ion release plays a lesser role in antibacterial activity, is one of the proposed pathways by which Fe2O3 NPs are effective against bacteria [37]. Contrarily, exposure to UV light causes the defect sites of Fe2O3 to create visible light electron–hole pairs or to produce reactive oxygen species. The electron–hole pairs that are created can help ROS like superoxide radical anions (O2 −) and hydroxyl radicals (OH−) generate. The OH− and O2 − free radicals generated can destroy the membrane, thereby eradicating the microorganisms [38]. Furthermore, cellular function disruption and membrane disarray are caused by important interactions such as dipole–dipole, hydrophobic, electrostatic, hydrogen bond, and van der Wall’s contacts [34].

Antibacterial activity of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. NPs inhibit the growth of bacteria and a zone of inhibition was shown in agar well plates. Graphical representation of antibacterial activity was determined for Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs by measuring the zone of inhibition (mm).

3.9 Antioxidant activity and percentage of inhibition of DPPH free radical by synthesized PF127Fe2O3NPs

Potential free radical scavenging capacity against DPPH free radicals is shown by Fe2O3 nanoparticles in Figure 8. The radical DPPH is transformed into the colorless stable diamagnetic compound by the NPs by transferring electrons or hydrogen to it. In previous studies, flavonoids and phenolics were noted to be present in B. vulgaris plants [39], which have been used to form nanoparticles encapsulating Fe2O3 using Pluronic F-127. The phenolic and flavonoid-rich plant extract serves as a reducing agent for the fabrication of nanoparticles [40]. A range of biological applications are available from phenolic compounds in edible and medicinal plants, including epigallocatechin gallate, catechins, ferulic acid, flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, and tannins [41]. The redox characteristics of phenolic compounds, which can be useful in the captivation and nullification of free radicals, dissolving peroxides, or quenching singlet and triplet oxygen, are primarily responsible for their antioxidant action [42]. In this study, the DPPH scavenging activity ranges from 5% to 70% for the five distinct concentrations of iron oxide NPs, which are 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 μg·mL−1. The scavenging mechanism elevates with the increasing concentration of Fe2O3 NPs. The trend observed in the scavenging activity is 64 > 32 > 16 > 8 > 4 > 2 μg·mL−1 of Fe2O3 NPs. When the DPPH radical interacts with the surface of Fe2O3 NPs, an electron is transferred from the oxygen species to the nitrogen atom of the DPPH, which scavenges the radical. So, Fe2O3 NPs exhibit effective antioxidant activity and can be used for therapeutic purposes.

Antioxidant activity and percentage of inhibition DPPH free radical by synthesized Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs. An illustration of the antioxidant activity (superoxide radical scavenging activity) of Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs is provided. The values are presented as means and standard deviations (n = 3).

3.10 Effect of PF127Fe2O3 NPs on cell viability

MTT assay assessed iron oxide nanoparticles’ cytotoxic activity against MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and Vero cell lines. Figure 9 depicts the cytotoxic effect of fabricated Fe2O3 NPs (2–64 µg·mL−1) for 24, 48, and 72 h. The MTT test, which relies on actively developing cells to generate blue, water-insoluble formazan crystals, has been frequently used to gauge the rate of cell proliferation. The concentration of the Fe2O3 NPs had an impact on the cell viability, which reduced as the concentration of Fe2O3 NPs increased. The IC50 value for the MCF7 (breast) cell line was calculated to be 21.9, 44.18, and 51.58 µg·mL−1 for 24, 48, and 72 h respectively. The IC50 value for the MDA-MB-231 (breast) cell line was calculated to be 27.17, 45.64, and 75.96 µg·mL−1 for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. The small impact of all samples on normal cell lines supports the unique impact of fabricated Fe2O3 NPs on cancer cells. It has been noted that mitochondria, which are redox-active organelles, are attacked by nanoparticles of various sizes and chemical compositions. In cells exposed to nanoparticles, mitochondria are a key location for ROS production. In the fabrication of nanoparticles, Flavonoids and Phenolics are found in B. vulgaris leaf extract to serve as a reducing agent and capping agent, respectively. PF127Fe2O3NPs have a lower toxicity risk. As a result of the controlled release of encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles, there is a reduced risk of quick increases in ROS in breast cancer cells, which leads to a gradual increase in their cytotoxicity. Nanoparticles may cause oxidative stress by altering ROS and influencing antioxidant defenses [43,44]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 −), superoxide radical (O2 −), and hydroxyl radical (OH*) are the most common ROS, and they damage biological components, including DNA, leading to apoptotic cell death [45]. This makes it evident that Fe2O3 NPs react in a similar way in MCF7 (breast) and MDA-MB-231 (breast) to induce apoptosis. Other than iron nanoparticles, the previous study explores the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Carissa spinarum leaf extract, revealing its potential as a rapid, cheap, and effective mosquitocides bio-resource [46]. The previous study presents a hybrid nanosystem for cancer-targeted fluorescence imaging and drug delivery, enhancing antibiofilm and antioxidant properties, with potential applications in various industries [47].

Pluronic F-127 coated Fe2O3 NPs cause cytotoxicity in MCF7 (breast), MDA-MB-231(breast), and Vero cells. MCF7 (breast), MDA-MB-231(breast), and Vero cell lines were treated with different concentrations (2–64 µg·mL−1) of Pluronic F-127 coated FeNO3 NPs for 24, 48 and 72 h. The cells were subjected to MTT assay and the values were depicted as ±SD of three individual experiments.

The study explored a novel approach to cancer research by investigating the potential anticancer properties of nanoparticles derived from B. vulgaris extract and encapsulated in Pluronic F-127. The study explores the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from B. vulgaris extract. The innovative formulation technique combines a natural extract with a biocompatible polymer, potentially enhancing the nanoparticles’ properties and applications. The nanoparticles effectively inhibit cancer cell proliferation, indicating their potential as an anticancer drug. They also exhibit antimicrobial properties against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. The study also highlights a dose-dependent effect on breast cancer cells (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231), highlighting the potential dosage for achieving desired anticancer effects. The nanoparticles also show enhanced antioxidant activity, suggesting their dual potential as an antioxidant and anticancer agent.

4 Conclusion

In the current research, we have fabricated an effective nanoparticle utilizing Pluronic F-127 as an effective delivery agent and B. vulgaris leaf extract as a reducing and capping agent. The characterization studies of the nanoparticles revealed the formation of a complete nanoparticle and the presence of all the components in the nanoparticle. We have also analyzed the effect of fabricated nanocomposite on microbes, cell viability of the MCF7 (breast), MDA-MB-231 (breast), Vero cell lines, and antioxidant activity. These results confirmed the potency of pluronic F-127-encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles as an anticancer drug and antioxidant. Furthermore, considerable research is required in the long term to determine the precise therapeutic mechanisms of the Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticle.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support given by the institution (Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah 77207, Saudi Arabia) for conducting this study.

-

Funding information: Author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The author contributed to the work.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Jeevanandam J, Barhoum A, Chan YS, Dufresne A, Danquah MK. Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: history, sources, toxicity, and regulations. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2018 Apr;9:1050–74. 10.3762/bjnano.9.98, PMID: 29719757; PMCID: PMC5905289.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Yetisgin AA, Cetinel S, Zuvin M, Kosar A, Kutlu O. Therapeutic nanoparticles and their targeted delivery applications. Molecules. 2020 May;25(9):2193. 10.3390/molecules25092193. PMID: 32397080; PMCID: PMC7248934.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Gupta RB. Fundamentals of drug nanoparticles. In: Nanoparticle Technology for Drug Delivery. Florida, United States: CRC Press; 2006. p. 25–44.10.1201/9780849374555.ch1Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Parveen K, Banse V, Ledwani L. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Their advantages and disadvantages. AIP Conf Proc. 2016;1724:020048. 10.1063/1.4945168.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Nikbakht M, Yahyaei B, Pourali P. Green synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles using fruit aqueous and methanolic extracts of Berberis vulgaris and Ziziphus vulgaris. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2015;9(1):349–55.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Singh J, Dutta T, Kim KH, Rawat M, Samddar P, Kumar P. ‘Green’ synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:84. 10.1186/s12951-018-0408-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Afshar AS, Nematpour FS. Evaluation of the cytotoxic activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Berberis vulgaris leaf extract. Jentashapir J Cell Mol Biol. 2021;12(1):e112437.10.5812/jjcmb.112437Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Pallela PNVK, Ummey S, Ruddaraju LK, Gadi S, Cherukuri CS, Barla S, et al. Antibacterial efficacy of green synthesized α- Fe2O3 nanoparticles using Sida cordifolia plant extract. Heliyon. 2019;5(11):e02765.10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02765Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Jagathesan G, Rajiv P. Biosynthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles using Eichhornia crassipes leaf extract and assessing their antibacterial activity. Biocatalysis Agric Biotechnol. 2018;13:90–4.10.1016/j.bcab.2017.11.014Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Naz S, Islam M, Tabassum S, Fernandes NF, de Blanco EJC, Zia M. Green synthesis of hematite (α- Fe2O3) nanoparticles using Rhus punjabensis extract and their biomedical prospect in pathogenic diseases and cancer. J Mol Structure. 2019;1185:1–7.10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.02.088Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Bashir M, Ali S, Farrukh MA. Green synthesis of Fe2O3 nanoparticles from orange peel extract and a study of its antibacterial activity. J Korean Phys Soc. 2020;76(9):848–54.10.3938/jkps.76.848Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Rahimi-Madiseh M, Lorigoini Z, Zamani-Gharaghoshi H, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Berberis vulgaris: specifications and traditional uses. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2017;20(5):569.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Neag MA, Mocan A, Echeverría J, Pop RM, Bocsan CI, Crişan G, et al. Berberine: botanical occurrence, traditional uses, extraction methods, and relevance in cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic, and renal disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Aug;9:557. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00557. PMID: 30186157; PMCID: PMC6111450.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] El-Zahar KM, Al-Jamaan ME, Al-Mutairi FR, Al-Hudiab AM, Al-Einzi MS, Mohamed AA. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activities of the ethanolic extract obtained from berberis vulgaris roots and leaves. Molecules. 2022 Sep;27(18):6114. 10.3390/molecules27186114, PMID: 36144846; PMCID: PMC9503718.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Ceclu L, Oana-Viorela N. Red beetroot: Composition and health effects - a review. J Nutr Med Diet Care. 2020;6:043.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:101–24. 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Bolhassani A, Javanzad S, Saleh T, Hashemi M, Aghasadeghi MR, Sadat SM. Polymeric nanoparticles: potent vectors for vaccine delivery targeting cancer and infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(2):321–32. 10.4161/hv.26796, Epub 2013 Oct 15 PMID: 24128651; PMCID: PMC4185908.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Civiale C, Licciardi M, Cavallaro G, Giammona G, Mazzone MG. Polyhydroxyethylaspartamide-based micelles for ocular drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2009 Aug;378(1–2):177–86. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.05.028, Epub 2009 May 22 PMID: 19465101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Abuelsamen A, Mahmud S, Mohd Kaus NH, Farhat OF, Mohammad SM, Al‐Suede FSR, et al. Novel Pluronic F‐127‐coated ZnO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and their in‐vitro cytotoxicity evaluation. Polym Adv Technol. 2021;32(6):2541–51.10.1002/pat.5285Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Fusco S, Borzacchiello A, Netti PA. Perspectives on: PEO-PPO-PEO triblock copolymers and their biomedical applications. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2006;21(2):149–64.10.1177/0883911506063207Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Elderdery AY, Alzahrani B, Hamza SMA, Mostafa-Hedeab G, Mok PL, Subbiah SK. Synthesis, characterization, and antiproliferative effect of CuO-TiO2-chitosan-amygdalin nanocomposites in human leukemic MOLT4 Cells. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2022 Sep;2022:1473922. 10.1155/2022/1473922, PMID: 36199748; PMCID: PMC9529517.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Sarathbabu S, Marimuthu SK, Ghatak S, Vidyalakshmi S, Gurusubramanian G, Ghosh SK, et al. Induction of apoptosis by pierisin-6 in HPV positive HeLa and HepG2 cancer cells is mediated by the caspase-3 dependent mitochondrial pathway. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19(3):337–46. 10.2174/1871520619666181127113848, PMID: 30479220.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Burganov TI, Katsyuba SA, Zagidullin AA, Zvereva EE, Miluykov VA, Sinyashin OG. Conjugation effects and optical spectra of 1,2-diphosphole cycloadducts. Russ Chem Bull. 2015;64:1896–900. 10.1007/s11172-015-1090-4.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Rahman MM, Khan SB, Jamal A, Faisal M, Aisiri AM. Iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2011;3:43–67.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Alagiri M, Hamid SBA. Green synthesis of α- Fe2O3 nanoparticles for photocatalytic application. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2014;25(8):3572–7.10.1007/s10854-014-2058-0Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Bhuiyan MSH, Miah MY, Paul SC, Aka TD, Saha O, Rahaman MM, et al. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticle using Carica papaya leaf extract: application for photocatalytic degradation of remazol yellow RR dye and antibacterial activity. Heliyon. 2020;6(8):e04603.10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04603Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Yardily A, Sunitha N. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles using hibiscus leaf extract, characterization, antimicrobial activity. Int J Sci Res Revie. 2019;8(7).10.7598/cst2019.1552Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Haiss W, Thanh NT, Aveyard J, Fernig DG. Determination of size and concentration of gold nanoparticles from UV− Vis spectra. Anal Chem. 2007;79(11):4215–21.10.1021/ac0702084Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Demirezen DA, Yilmaz D, Yılmaz Ş. Green synthesis and characterization of iron nanoparticles using Aesculus hippocastanum seed extract. Int J Adv Sci Eng Technol. 2018;6:2321–8991.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Pottker WE, Ono R, Cobos MA, Hernando A, Araujo JF, Bruno AC, et al. Influence of order-disorder effects on the magnetic and optical properties of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Ceram Int. 2018;44(14):17290–7.10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.06.190Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang L, Yin L, Wang C, Lun N, Qi Y, Xiang D. Origin of visible photoluminescence of ZnO quantum dots: defect-dependent and size-dependent. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114(21):9651–8.10.1021/jp101324aSuche in Google Scholar

[32] Oliveira LH, De Moura AP, La Porta FA, Nogueira IC, Aguiar EC, Sequinel T, et al. Influence of Cu-doping on the structural and optical properties of CaTiO3 powders. Mater Res Bull. 2016;81:1–9.10.1016/j.materresbull.2016.04.024Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Bibi I, Kamal S, Ahmed A, Iqbal M, Nouren S, Jilani K, et al. Nickel nanoparticle synthesis using Camellia Sinensis as reducing and capping agent: Growth mechanism and photo-catalytic activity evaluation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;103:783–90.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Rufus A, Sreeju N, Philip D. Synthesis of biogenic hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles for antibacterial and nanofluid applications. RSC Adv. 2016;6(96):94206–17.10.1039/C6RA20240CSuche in Google Scholar

[35] Nazar N, Bibi I, Kamal S, Iqbal M, Nouren S, Jilani K, et al. Cu nanoparticles synthesis using biological molecule of P. granatum seeds extract as reducing and capping agent: Growth mechanism and photo-catalytic activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;106:1203–10.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.126Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Ahmmad B, Leonard K, Islam MS, Kurawaki J, Muruganandham M, Ohkubo T, et al. Green synthesis of mesoporous hematite (α- Fe2O3) nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activity. Adv Powder Technol. 2013;24(1):160–7.10.1016/j.apt.2012.04.005Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Vihodceva S, Šutka A, Sihtmäe M, Rosenberg M, Otsus M, Kurvet I, et al. Antibacterial activity of positively and negatively charged hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles to escherichia coli, staphylococcus aureus and vibrio fischeri. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Mar;11(3):652. 10.3390/nano11030652. PMID: 33800165; PMCID: PMC7999532.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Kombaiah K, Vijaya JJ, Kennedy LJ, Bououdina M, Ramalingam RJ, Al-Lohedan HA. Okra extract-assisted green synthesis of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles and their optical, magnetic, and antimicrobial properties. Mater Chem Phys. 2018;204:410–9.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.10.077Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zovko Koncić M, Kremer D, Karlović K, Kosalec I. Evaluation of antioxidant activities and phenolic content of Berberis vulgaris L. and Berberis croatica Horvat. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 Aug–Sep;48(8–9):2176–80. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.025, Epub 2010 May 17 PMID: 20488218.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Mat Yusuf SNA, Che Mood CNA, Ahmad NH, Sandai D, Lee CK, Lim V. Optimization of biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles from flavonoid-rich Clinacanthus nutans leaf and stem aqueous extracts. R Soc Open Sci. 2020 Jul;7(7):200065. 10.1098/rsos.200065. PMID: 32874618; PMCID: PMC7428249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009 Nov–Dec;2(5):270–8. 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498, PMID: 20716914; PMCID: PMC2835915.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Rehana D, Mahendiran D, Kumar RS, Rahiman AK. Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of copper oxide nanoparticles synthesized using medicinally important plant extracts. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;89:1067–77.10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.101Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Abdal Dayem A, Hossain MK, Lee SB, Kim K, Saha SK, Yang GM, et al. The role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the biological activities of metallic nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jan;18(1):120. 10.3390/ijms18010120, PMID: 28075405; PMCID: PMC5297754.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Manke A, Wang L, Rojanasakul Y. Mechanisms of nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:942916. 10.1155/2013/942916 Epub 2013 Aug 20. PMID: 24027766; PMCID: PMC3762079.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Alarifi S, Ali D, Alkahtani S, Alhader MS. Iron oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress, DNA damage, and caspase activation in the human breast cancer cell line. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;159(1):416–24.10.1007/s12011-014-9972-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Govindarajan M, Nicoletti M, Benelli G. Bio-physical characterization of poly-dispersed silver nanocrystals fabricated using carissa spinarum: A potent tool against mosquito vectors. J Clust Sci. 2016;27:745–61. 10.1007/s10876-016-0977-z.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Karthika V, AlSalhi MS, Devanesan S, Gopinath K, Arumugam A, Govindarajan M, et al. Chitosan overlaid Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite for targeted drug delivery, imaging, and biomedical applications. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18912. 10.1038/s41598-020-76015-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”