Abstract

Selenium (Se) is indispensable for animals and humans. One option to address Se deficiency is to biofortify plants with Se. Biofortification of forage with Se nanoparticles (NPs) is gaining more attention as an efficient and safe source of Se for livestock. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of different concentrations of NPs-Se (0, 30, 50, 100, 150, and 250 mg·L−1) on the growth of alfalfa harvested multiple times, and to provide a basis for the production of Se-enriched forages. Applying 50 mg·L−1 concentration of NPs-Se had the best effect on yield over three harvests. Over three harvests, low-dose NPs-Se (30 and 50 mg·L−1) application significantly increased peroxidase and superoxide dismutase activities, chlorophyll content and carotenoid content, and significantly decreased malondialdehyde content. The total Se content and Se accumulation in plants at the same harvest showed an upward trend with increasing Se concentration. At the same concentration, from first harvest to third harvest, Se content and Se accumulation showed an initially increasing and then decreasing trend. The evaluation found that foliar application of NPs-Se at 50 mg·L−1 could have the greatest positive effect on the growth and yield of multiple-harvested alfalfa.

1 Introduction

Selenium (Se) is an essential trace element for human beings. Se supplementation is of paramount importance in Se-deficient countries and regions, because it improves people’s thyroid function, participates in the body’s antioxidant defenses, enhances their immunity and can reduce cardiovascular disease and cancer risks [1]. Se is a component of proteins and enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase, thyroxine 5-deiodinase, selenoprotein K, selenoprotein N, and selenoprotein P [2]. It is involved in the production of active thyroid hormones and the regulation of the immune system, while protecting cells from damage by free radicals generated during oxidative metabolism [3]. In many places, including in the United States, Australia, and China, Se is only present in small amounts in soils, resulting in a correspondingly low Se content of plant produce [4]. Recent estimates indicate that 15–20% of children and adults around the world are Se deficient [5]. Therefore, relying only on naturally occurring Se in foods is often insufficient to meet the basic needs of the human body, resulting in a low Se status which poses a potential threat to human health. Biofortification is the principal method to prevent inadequate Se intake in both humans and animals. To date, biofortification with Se has been conducted on some agricultural products, such as wheat [6], peas [7], rice [8], and vegetables [9]. Se, like several stressors, such as certain toxins, biostimulants, or non-essential elements, elicits a biphasic dose–response. In other words, low concentrations of Se will promote the growth and development of plants, while high concentrations of Se will inhibit and may even have toxic effects [10]. Nanotechnology is a rapidly developing technique for targeted and precise micronutrient fertilizing in agriculture [11]. Se can be found in different varieties of forms, including selenite, selenate, nanoparticles of Se (NPs-Se), and selenoproteins [12]. NPs-Se is a red elemental Se with lower toxicity and higher biological activity than inorganic Se [13,14]. Therefore, NPs-Se has good prospects as a new Se source in the Se-enrichment industry.

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is a perennial legume forage, which is widely planted worldwide because of its adaptability, high production performance, good palatability, high protein, and high digestible fiber content [15,16]. Alfalfa has deep roots, which can enrich soil organic matter to a certain extent and prevent water erosion and wind erosion [17,18]. At the same time, with multiple harvesting during a year, high-yield alfalfa can help meet demand for forage in crop–livestock farming systems [19]. Application of Se not only increases the Se content in plants, but also increases plant yield, nutritional quality, and resistance to external environmental stressors affecting plant growth [20,21]. Therefore, the production of Se-enriched alfalfa could provide a safe source of Se combined with high yield and high-quality forage for livestock. The main methods currently used to enrich Se in alfalfa include foliar application of Se and application of Se in the soil. Studies have shown that foliar fertilization has remarkable effects compared with soil fertilization [5]. When Se is applied in soil, the concentration and form of Se, and the effects of soil microorganisms and interaction with metal ions have great influence on the absorption of Se [22,23]. However, foliar application of Se is simple, safe, and less harmful to soil [24]. The feeding value of alfalfa leaves is much greater than that of stems, so the effect of foliar application of Se content in leaves is potentially of great significance.

Previous studies on Se bioaugmentation have focused on plant biological effects over one period [25]. For forage plants such as alfalfa that are harvested several times, it is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the effects of Se on plant physiological characteristics and Se accumulation across different harvests. Therefore, the present study aimed to clarify the effects of NPs-Se concentration (0, 30, 5, 100, 150, and 250 mg·L−1) on yield, physiological characteristics, and Se accumulation during three successive alfalfa harvests. The study aimed to explore the effects of foliar biofortification with NPs-Se on alfalfa, to clarify the suitable dose of NPs-Se in alfalfa production, to provide a safe source of Se for humans and livestock.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Treatments and plant materials

The plant materials were the alfalfa variety “WL232HQ,” which has a fall dormancy grade of 2.6 and a cold resistance index of 1.3. Seeds were provided by Xintai Agricultural Science and Technology Co. Ltd, Baotou City, Inner Mongolia.

NPs-Se was 5% NPs-Se nutrient solution, provided by Shenzhen Zhigao Military and Civilian Integration Equipment Technology Research Institute.

The experiment was conducted at the Baotou Experimental Station for Forage Processing and High Efficient Utilization, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University. The experimental station is located in Baotou City in Inner Mongolia, China (110°37″–110°27″E; 40°05″–40°17″N). Alfalfa was sown in May 2020 using a drill, with a distance between rows of 10 cm. Because alfalfa is highly regenerative, it is generally harvested three times a year in the test area. The field experiments were conducted in 2021. After reaching a height of 20 cm, plants were sprayed with Se at a rate of 1,000 L·hm−2. Leaf spraying concentrations were T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. The area of each test plot was 20 m2 (5 m × 4 m). Each treatment was repeated three times. Alfalfa was harvested in the initial flowering stage. The specific spraying and harvest dates are shown in Table 1.

Spraying and harvest dates

| Spraying dates | Harvest times | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st harvest | May 7, 2021 | June 10, 2021 |

| 2nd harvest | July 2, 2021 | July 19, 2021 |

| 3rd harvest | August 16, 2021 | September 13, 2021 |

2.2 Measurements

2.2.1 Determination of yield, crude protein, and Se content

After harvesting, plants were thoroughly washed with deionized water. After oven-drying at 105°C for 0.5 h to kill bacteria, all samples were dried for 72 h at 65°C to a constant weight and the weights (DW) were recorded. For the determination of Se concentration, the dried samples were ground and cryopreserved (4°C). We weighed 2.0 g of sample (accurate to 0.0001 g), placed it in a 100 mL high-profile beaker, added 15 mL of mixed acid (HNO3:HClO4 ratio of 4:1) to digest overnight, then heated the solution at 160°C to clarify and cool to 50 mL, which was taken as the sample digestion solution. We then took 20 mL digestive solution and a 50 mL volume bottle, and added 8 mL hydrochloric acid and 2 mL potassium ferricyanide solution to a constant volume. Total Se contents were determined via hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectrometry after oxidation digestion and reduction [26]. The amount of Se extracted by plants was calculated as follows [27]:

2.2.2 Measurement of antioxidant enzyme activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration

The fresh samples were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.8). The homogenate was then centrifuged for 20 min (11,000×g, 4°C). The activities of peroxidase (POD) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes were determined in the supernatant. SOD activity was detected by monitoring the photoreduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT). One SOD enzyme activity unit is defined as 50% inhibition of NBT reduction at 560 nm [28]. Activity of POD was assayed by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 470 nm, as described by Zhang and Kirkham [29]. A change of 0.01 absorbance per minute corresponds to a unit of POD activity. MDA was extracted by homogenizing the fresh samples in 3 mL of 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and centrifuging the homogenate for 10 min (11,500×g). MDA content in the supernatant was measured using the thiobarbituric acid method and calculated using the absorption coefficient of 155 mmol·L−1·cm−1 [28].

2.2.3 Determination of photosynthetic pigments

Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid measurements were performed by homogenizing 0.5 g fresh leaves (samples of three plants in each replicate bulked) in 25 mL of ethanol/acetone. Absorbance of the extract at 663, 645, and 470 nm (chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid) was measured with a spectrophotometer and the total chlorophyll concentration was calculated using the formulas described by Arnon [27].

2.3 Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and SAS statistical software version 9.4. Analysis of variance using two-way ANOVA was conducted between Se treatments and harvests, and one-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the differences among Se treatments within the same harvest. Separation of means was performed by post-hoc test (Duncan’s test), and significant differences were assessed at the levels P < 0.05 and P < 0.01. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

In order to determine the optimum concentration, a comprehensive evaluation of the indicators of each treatment was carried out. Because of different indicator units, scoring functions were used to score the indicators. The equations of the score curves are as follows [30]:

where f(x) is the linear score, x is the index value, and L and U are the lower and upper threshold values, respectively. Eq. 2 was used for the “more is better” scoring function, whereas Eq. 3 was used for the “less is better” function. For the “optimum” function, indicators were scored as “more is better” for the increasing part and then scored as “less is better” for the decreasing part.

On the basis of the indicator scores, the weight of each index was determined according to the results of principal component analysis (PCA), and the final comprehensive evaluation index formula for alfalfa under the treatment of NPs-Se concentration (CEI) was as follows

where W is the PCA weighting, N is the indicator score, i is the index for indicators, and j is the index for harvests.

3 Results

3.1 Yield

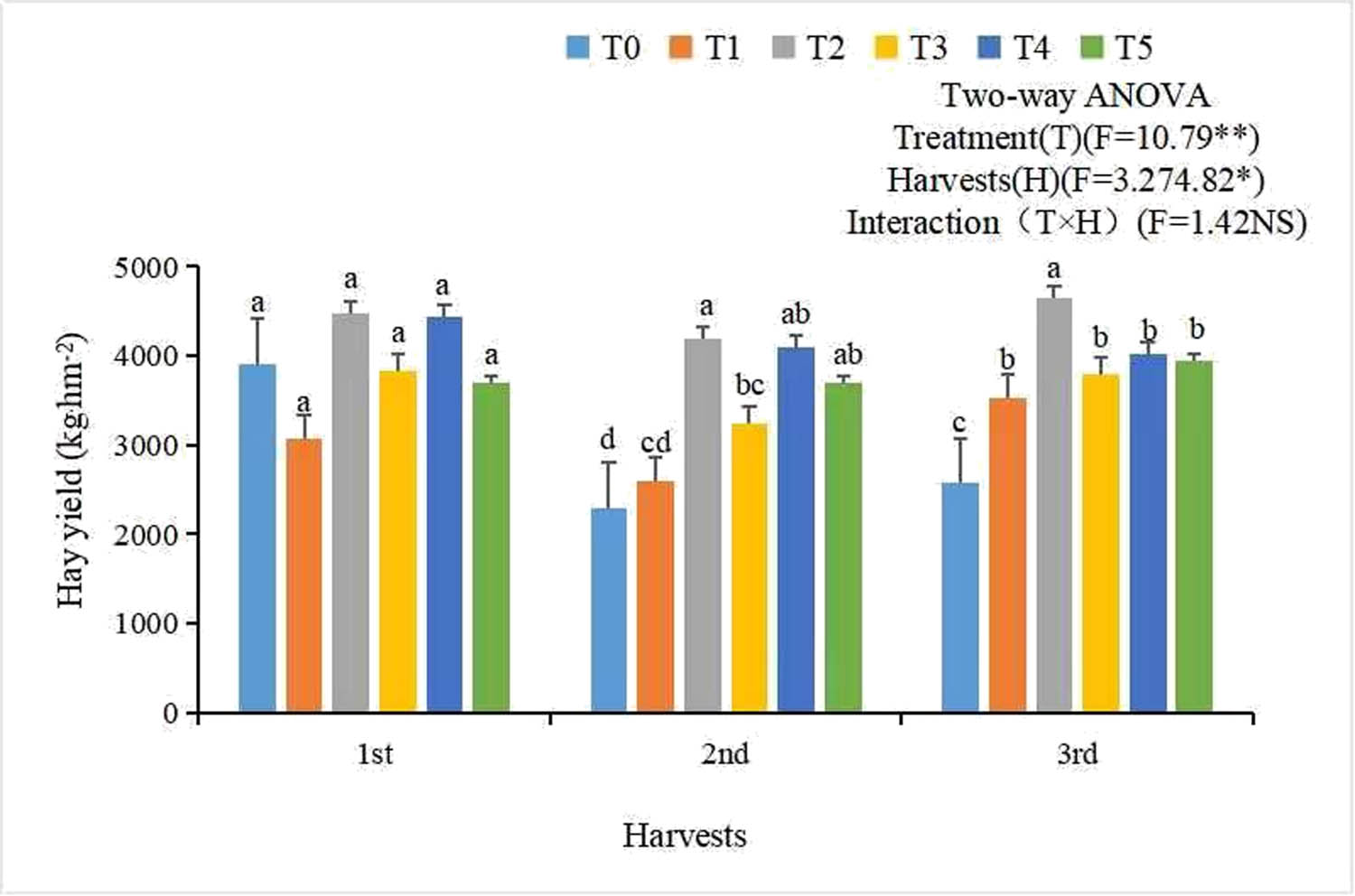

Treatment with Se had significant effects on alfalfa yield (P < 0.01, Figure 1). With increasing Se concentration, yield first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum under T2, especially in the third crop. From the first harvest to the third harvest, the T0 treatment first decreased and then tended to be constant, while yield in T1, T2, and T3 treatments decreased first and then increased slightly. The T4 treatment showed a downward trend and the T5 treatment showed little change. At third harvest, the yield of the T1, T3, T4, and T5 treatments were almost the same, and the T2 treatment was higher than the other treatments.

Effects of different Se concentrations on alfalfa yield during three consecutive harvests. T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between different Se applications in the same harvest (P < 0.05). * Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.05). ** Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.01). NS indicates no significant according to Duncan’s test (P > 0.05). Bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3).

3.2 Total Se content

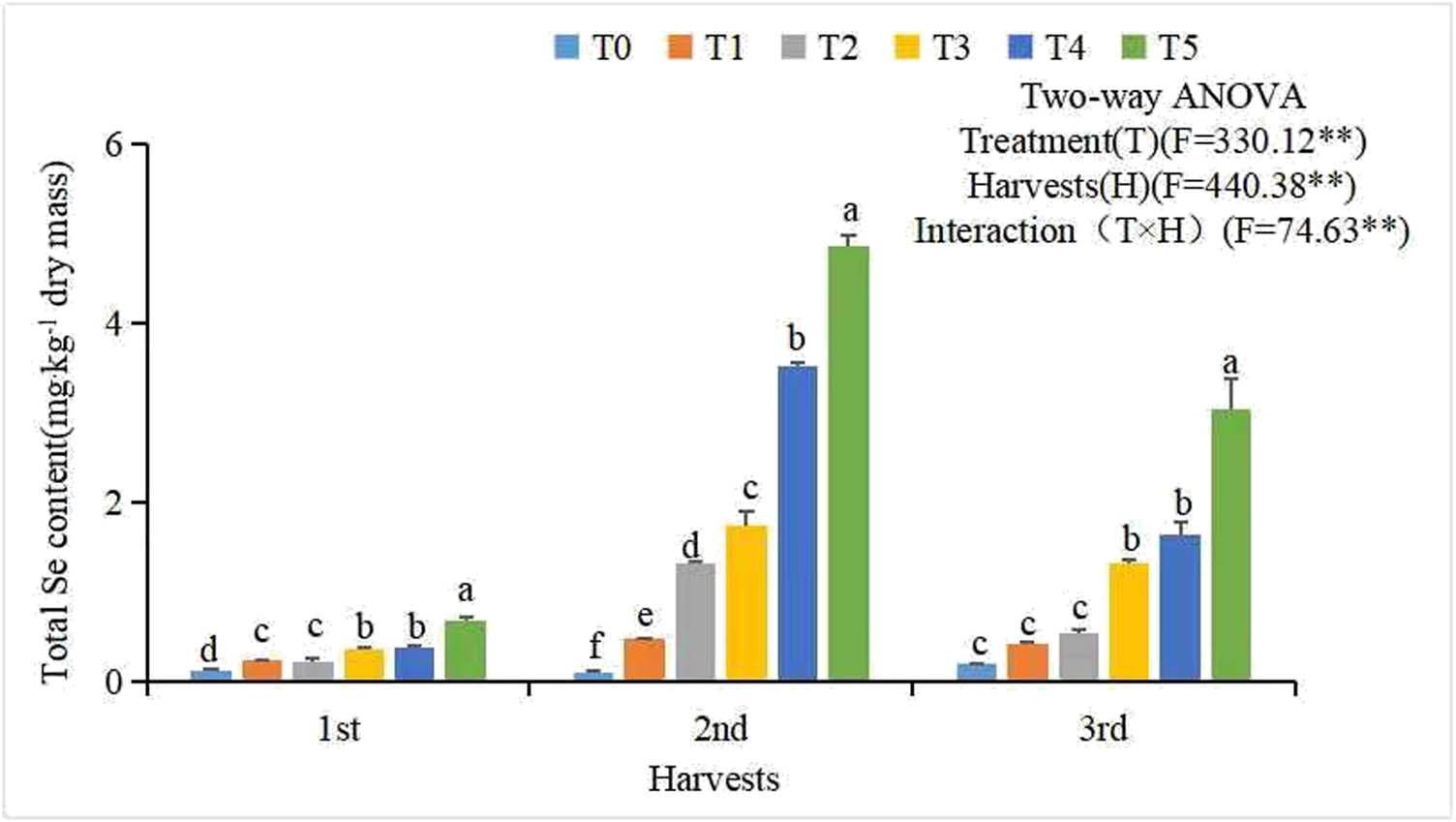

The interaction between Se concentration and harvest had significant effects on the total Se content of alfalfa (P < 0.01, Figure 2). Under the six concentration treatments, the changes of total Se content in alfalfa in different harvests were consistent. Total Se content increased with increasing Se dosage. From the first harvest to the third harvest, the total Se content of plants first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum in the second harvest. In the second harvest, the total Se content of plants under the T5 treatment reached 4.86 mg·L−1, which was 38.6 times higher than that of T0.

Effects of different Se concentrations on total Se content of alfalfa during three consecutive harvests. T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between different Se applications in the same harvest (P < 0.05). **Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.01). Bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3).

3.3 Se extracted by alfalfa

Table 2 shows that the increase in Se extraction by alfalfa was related to the trend in Se concentration. The interaction between Se concentration and harvest had significant effects on the amount of Se extracted by alfalfa (P < 0.01). In each harvest, the extracted Se content in alfalfa increased with increasing Se concentration. From the first harvest to the third harvest, the extracted Se content in alfalfa in the T0 and T1 treatments showed an upward trend, while the T2, T3, T4, and T5 treatments showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing.

Effects of different Se concentrations on total amount of Se extracted by alfalfa during three consecutive harvests (g·hm−2)

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Harvest | 0.39 ± 0.14d | 0.70 ± 0.08d | 0.97 ± 0.10cd | 1.38 ± 0.22bc | 1.67 ± 0.51b | 2.48 ± 0.63a |

| 2nd Harvest | 0.24 ± 0.09d | 1.22 ± 0.33d | 5.54 ± 0.68c | 5.60 ± 0.46c | 14.46 ± 1.81b | 17.94 ± 1.41a |

| 3rd Harvest | 0.48 ± 0.03c | 1.48 ± 0.24c | 2.50 ± 0.21bc | 4.99 ± 0.70b | 6.59 ± 0.91b | 12.11 ± 3.04a |

| F -test (two-ways) | ||||||

| Treatment | ** | |||||

| Harvest | ** | |||||

| Treatment × harvest | ** | |||||

Note: Data are mean ± SD around the mean (n = 3). T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters in superscripts indicate significant differences between different Se applications in the same harvest (P < 0.05). ** Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.01).

3.4 Antioxidant enzyme activities and MDA content

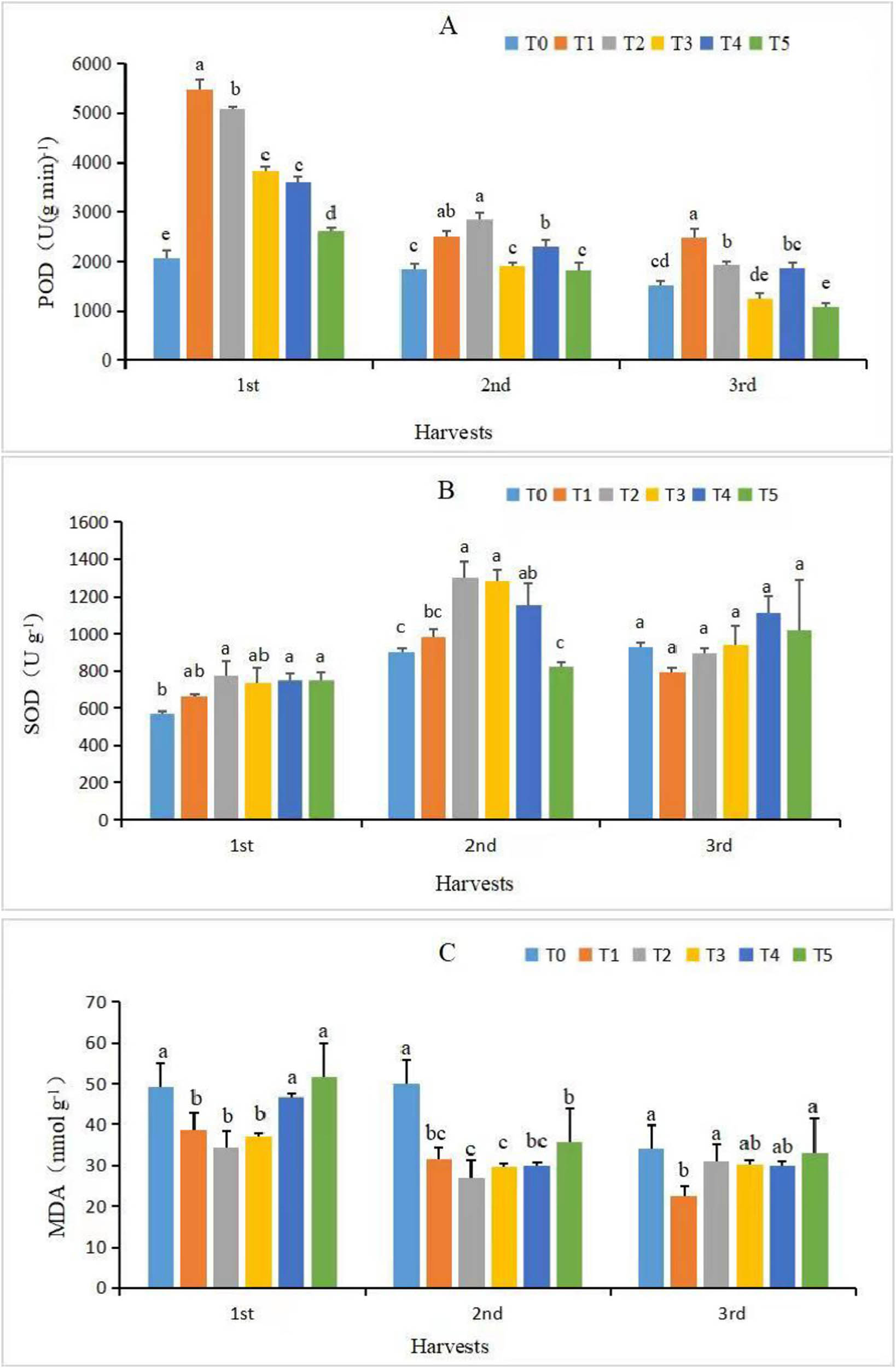

Se played a positive role as an antioxidant at low doses. Table 3 shows that the main effect and interactive effect of Se concentration and harvest on POD activities and MDA content in alfalfa were significant (P < 0.01), but the interactive effect had no significant effect on SOD activities (P > 0.05). The main effect of harvest was significant on SOD activities (P < 0.01), while the main effect of Se concentration only had a significant effect on SOD activities at the level of P < 0.05.

Variance analysis results of antioxidant enzyme activity and MDA of alfalfa under different Se concentrations and harvests

| Sources of changes | df | F (POD) | F (SOD) | F (MDA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 5 | 105.9** | 3.44* | 24.93** |

| Harvest | 2 | 494.92** | 26.93** | 69.17** |

| Treatment × harvest | 10 | 24.31** | 2.04 | 6.08** |

Note: POD: peroxidase; SOD: superoxide dismutase; MDA: malondialdehyde. * Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.05). ** Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.01).

POD activity first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration across the three harvests (Figure 3a). In the first harvest, the Se concentrations in all treatments were significantly higher than T0 (P < 0.05), and POD activity reached a maximum under T1, which was 1.65 times higher than that under T0. In the second harvest, POD activity reached a maximum under the T2 treatment, which was significantly increased by 0.54 times compared with T0 (P < 0.05), while POD activity under T3, T5, and T0 treatments had no significant effect (P > 0.05). In the third harvest, POD activity reached a maximum under the T1 treatment, which was significantly increased by 0.63 times compared with T0 (P < 0.05) but was significantly lower than T0 under the T5 treatment (P > 0.05), indicating that POD activity began to be inhibited under high Se concentration.

Effects of different Se concentrations on antioxidant enzyme activity and lipid peroxidation products in alfalfa during three consecutive harvests: (a) POD, (b) SOD, and (c) MDA. T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between different Se applications in the same harvest (P < 0.05). Bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3).

The effect of Se concentration on SOD activity in alfalfa varied between harvests (Figure 3b). In the first harvest, with increasing Se concentration, SOD activity first increased and then remained stable, and T2 treatment was a turning point. SOD activity under T2 to T5 concentration treatments was significantly higher than in the T0 treatment (P < 0.05). In the second harvest, SOD activity first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration, and reached a maximum value in the T2 treatment, which was significantly higher than under T0 (P < 0.05). In the first and second harvests, the SOD activity of the T2 treatment was 0.35 and 0.44 times higher than that of T0, respectively. In the third harvest, there was no significant difference in SOD activity between treatments (P > 0.05).

The response of MDA content in alfalfa to the six Se concentration treatments was consistent among the three harvests (Figure 3c). In the first and second harvests, with increasing Se concentration, MDA content first decreased and then increased, and both harvests had the lowest value in the T2 treatment, which was significantly reduced by 30% and 46% compared with T0, respectively (P < 0.05). In the third harvest, the T1 treatment was significantly lower than the other treatments (P < 0.05), with a significant reduction of 34% compared to T0 (P < 0.05).

3.5 Photosynthetic pigments

As shown in Table 4, the interaction of Se concentration and harvest had no significant effect on chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, or total chlorophyll content (P > 0.05), but there was a significant effect on carotenoids (P < 0.01). The main effect of harvest on photosynthetic pigments was significant (P < 0.01). Se concentration had a significant effect on chlorophyll a, total chlorophyll content, and carotenoids (P < 0.05) but had no significant effect on chlorophyll b (P > 0.05). Chlorophyll a content was observed in the first harvest, but Se concentration treatment had no significant effect on it (P > 0.05). In the second and third harvests, chlorophyll a first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration, and reached its highest point under the T1 and T2 treatments, respectively, which were significantly higher than those under T0 (P < 0.05). Chlorophyll b content first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration in the first and second harvests, reaching maximum values in the T3 and T1 treatments, respectively, which were significantly higher than those under T0 (P < 0.05). In the third harvest, Se concentration treatment had no significant effects (P > 0.05). Across the three harvests, total chlorophyll content first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration. On the whole, total chlorophyll content was significantly higher than T0 under low Se concentration treatments (P < 0.05), and there was no significant effect under high Se concentration treatments (P > 0.05). In the first harvest, compared with T0, carotenoid contents in T1–T4 treatments were significantly increased (P < 0.05), while carotenoid content in T5 treatment was not significantly affected (P > 0.05). In the second harvest, compared with T0, the carotenoid content of the T1–T5 treatments increased significantly (P < 0.05). In the third harvest, compared with T0, there was no significant difference in the carotenoid contents in T1–T5 treatments (P > 0.05).

Effects of different Se concentrations on photosynthetic pigments in alfalfa leaf during three consecutive harvests

| Treatment | F-test (two-ways) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | Treatment | Harvest | Treatment × harvest | ||

| Chlorophylla (mg·g−1) | 1st harvest | 1.86 ± 0.52a | 2.27 ± 0.09a | 2.40 ± 0.02a | 2.48 ± 0.17a | 2.51 ± 0.09a | 2.32 ± 0.09a | * | ** | NS |

| 2nd harvest | 2.59 ± 0.10c | 2.97 ± 0.24a | 2.91 ± 0.18ab | 2.68 ± 0.06bc | 2.70 ± 0.06bc | 2.53 ± 0.09c | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 2.52 ± 0.12b | 2.45 ± 0.11b | 2.81 ± 0.02a | 2.49 ± 0.16b | 2.44 ± 0.15b | 2.50 ± 0.03b | ||||

| Chlorophyllb (mg·g−1) | 1st harvest | 1.07 ± 0.04b | 1.2 ± 0.01ab | 1.19 ± 0.02ab | 1.40 ± 0.24a | 1.22 ± 0.09ab | 1.17 ± 0.06b | NS | ** | NS |

| 2nd harvest | 1.33 ± 0.07b | 1.47 ± 0.09a | 1.42 ± 0.09ab | 1.37 ± 0.06ab | 1.42 ± 0.07ab | 1.42 ± 0.02ab | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.84 ± 0.05a | 0.83 ± 0.05a | 0.97 ± 0.01a | 0.86 ± 0.08a | 0.85 ± 0.01a | 0.90 ± 0.05a | ||||

| Carotenoid (mg·g−1) | 1st harvest | 0.63 ± 0.04b | 0.71 ± 0.03a | 0.72 ± 01a | 0.73 ± 0.04a | 0.71 ± 0.02a | 0.67 ± 0.02ab | ** | ** | ** |

| 2nd harvest | 0.78 ± 0.05b | 0.96 ± 0.05a | 0.93 ± 0.05a | 0.89 ± 0.05a | 0.90 ± 0.04a | 0.95 ± 0.01a | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.81 ± 0.05ab | 0.87 ± 0.01a | 0.8 ± 0.03ab | 0.78 ± 0.07b | 0.75 ± 0.05b | 0.82 ± 0.02ab | ||||

| Total chlorophyll (mg·g−1) | 1st harvest | 2.93 ± 0.89b | 3.47 ± 0.15ab | 3.59 ± 0.05ab | 3.88 ± 0.10a | 3.73 ± 0.24a | 3.49 ± 0.19ab | * | ** | NS |

| 2nd harvest | 3.92 ± 0.17c | 4.44 ± 0.33a | 4.33 ± 0.27ab | 4.05 ± 0.08bc | 4.13 ± 0.12abc | 3.95 ± 0.09c | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 3.36 ± 0.19b | 3.28 ± 0.21b | 3.78 ± 0.02a | 3.36 ± 0.30b | 3.30 ± 0.17b | 3.40 ± 0.05b | ||||

Note: Data are mean ± SD around the mean (n = 3). T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters in superscripts indicate significant differences between different Se applications in the same harvest (P < 0.05). * Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.05). ** Indicates significant according to Duncan’s test (P < 0.01). NS indicates no significant according to Duncan’s test (P > 0.05).

3.6 Comprehensive evaluation

The comprehensive score of the effect of Se concentration on various indicators of alfalfa is shown in Table 5. The variables were transformed using linear scoring functions. After deciding the shape of the anticipated response (“more is better,” “less is better”), the limits or threshold values were assigned for each indicator. Yield, total Se content, POD, SOD, and photosynthetic pigments were evaluated using “more is better” curves. MDA was evaluated using a “less is better” curve, because the lower the MDA content, the lower the cell membrane damage. The scores were then calculated by using Eqs. 2–4. The final ranking was T2 > T4 > T3 > T1 > T5 > T0.

Comprehensive evaluation of the effect of Se concentration on alfalfa in three harvests

| Treatment | Harvest | Yield | Total Se content | POD | SOD | MDA | Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Total chlorophyll | Carotenoid | CEI | Ranking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 1st harvest | 0.4304 | 0.1038 | 0.3027 | 0.1000 | 0.1742 | 0.1000 | 0.4375 | 0.1000 | 0.1000 | 0.3505 | 6 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.1000 | 0.1000 | 0.2565 | 0.5110 | 0.1536 | 0.6919 | 0.8031 | 0.6901 | 0.5091 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.2033 | 0.1170 | 0.1911 | 0.5424 | 0.6449 | 0.6351 | 0.1141 | 0.3563 | 0.5909 | ||||

| T1 | 1st harvest | 0.3932 | 0.1246 | 1.0000 | 0.2158 | 0.4970 | 0.4324 | 0.6203 | 0.4219 | 0.3182 | 0.5548 | 4 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.2141 | 0.1700 | 0.3932 | 0.6098 | 0.7231 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.5694 | 0.1605 | 0.3857 | 0.3739 | 1.0000 | 0.5784 | 0.1000 | 0.3086 | 0.7545 | ||||

| T2 | 1st harvest | 0.9338 | 0.1227 | 0.9171 | 0.3504 | 0.6384 | 0.5378 | 0.6063 | 0.4934 | 0.3455 | 0.6624 | 1 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.8265 | 0.3307 | 0.4610 | 1.0000 | 0.8623 | 0.9514 | 0.9297 | 0.9344 | 0.9182 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 1.0000 | 0.1832 | 0.2763 | 0.5034 | 0.7376 | 0.8703 | 0.2969 | 0.6066 | 0.5636 | ||||

| T3 | 1st harvest | 0.6890 | 0.1492 | 0.6615 | 0.3027 | 0.5549 | 0.6027 | 0.9016 | 0.6662 | 0.3727 | 0.5723 | 3 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.4623 | 0.4101 | 0.2677 | 0.9811 | 0.7829 | 0.7649 | 0.8594 | 0.7675 | 0.8091 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.6686 | 0.3307 | 0.1353 | 0.5506 | 0.7588 | 0.6108 | 0.1422 | 0.3563 | 0.5091 | ||||

| T4 | 1st harvest | 0.9203 | 0.1511 | 0.6165 | 0.3202 | 0.2577 | 0.6270 | 0.6484 | 0.5768 | 0.3182 | 0.5885 | 2 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.7877 | 0.7485 | 0.3495 | 0.8162 | 0.7733 | 0.7811 | 0.9297 | 0.8152 | 0.8364 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.7596 | 0.3912 | 0.2594 | 0.7688 | 0.7671 | 0.5703 | 0.1281 | 0.3205 | 0.4273 | ||||

| T5 | 1st harvest | 0.6335 | 0.2097 | 0.4125 | 0.3169 | 0.1000 | 0.4730 | 0.5781 | 0.4338 | 0.2091 | 0.5203 | 5 | |

| 2nd harvest | 0.6339 | 1.0000 | 0.2509 | 0.4070 | 0.5925 | 0.6432 | 0.9297 | 0.7079 | 0.9727 | ||||

| 3rd harvest | 0.7270 | 0.6578 | 0.1000 | 0.6527 | 0.6741 | 0.6189 | 0.1984 | 0.3801 | 0.6182 | ||||

| Weight | 0.1211 | 0.0560 | 0.1169 | 0.1050 | 0.1003 | 0.1136 | 0.1239 | 0.1380 | 0.1252 | ||||

Note: T0 = 0 mg·L−1, T1 = 30 mg·L−1, T2 = 50 mg·L−1, T3 = 100 mg·L−1, T4 = 150 mg·L−1, and T5 = 250 mg·L−1. POD: peroxidase; SOD: superoxide dismutase; MDA: malondialdehyde; CEI: comprehensive evaluation index.

4 Discussion

Alfalfa is an important forage plant in agricultural and animal husbandry production systems, and yield is a strongly prioritized indicator. At an ideal concentration, Se can promote plant growth, but excessive amounts of Se can be toxic to some plant species, including wheat [6], rice [8], and vegetables [9]. In this study, the application of NPs-Se promoted the yield of alfalfa harvested three times but did not inhibit the yield. Especially in the third harvest, a low concentration of NPs-Se was found to significantly improve yield, and the best effect was obtained when the concentration was T2 (i.e., 50 mg·L−1). When concentrations were T4 (150 mg·L−1) and T5 (250 mg·L−1), the yield of alfalfa showed a downward trend in the third harvest compared with the first two harvests. This finding is inconsistent with the findings of Bai et al. [31], whose study showed that the application of sodium selenite in soil inhibits antioxidant enzyme activities and photosynthetic parameters of alfalfa when Se concentration exceeded 20 mg·L−1, resulting in the inhibition of alfalfa growth. The reasons for the lack of inhibition in our study may be that, first the Se application method was different, as foliar spraying was used in this study, and second it may be that the highest concentration used in our study did not reach the threshold for toxicity for alfalfa. We found that there was no significant effect of NPs-Se on the yield of the first harvest, which was consistent with the results of Xia et al. [32]. However, there was a significant difference between the effects of NPs-Se concentrations on the yield of the second and third harvest. Previous studies only investigated the effects on one harvest and did not explore the effect of Se on multiple harvests. Therefore, the biological effects of Se NPs on multiple harvests are different and further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

The Se content in common plants is 0.02–1.5 mg·L−1 [33]. In the present study, the Se content in alfalfa increased with increasing NPs-Se concentration. Moreover, the amount of Se extracted from plants also increased. These results were similar to those of previous studies [28,34]. In this study, in the three harvests, both the Se content and the extraction amount reached a maximum in the second harvest. The reason may be that at the second harvest, when temperature was high, alfalfa grew vigorously and had a strong ability to absorb nutrients such as Se. There was a clear downward trend in the third harvest, especially at high concentrations (150 and 250 mg·L−1). The results of this study were consistent with those of Di et al. [35]. This indicates that the high concentration of NPs-Se produced an inhibitory effect on Se content and extraction amount in the third harvest compared with the first two harvests. It is possible that foliar sprays cause the transfer of Se from leaves to roots and that multiple sprays cause the roots to accumulate Se up to the domain value of alfalfa [32]. This finding provides new insights for the development of organic Se-enriched products by studying alfalfa harvested several times a year.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) results from electron leakage to O2 during photosynthetic electron transport, and a certain concentration of ROS (at a level that does not induce harmful effects) is necessary for plants to maintain their normal physiological processes [36]. However, excessive ROS damages plants and suppresses growth when plants are exposed to stress [37]. The accumulation of excess ROS would cause membranous peroxidation in the cell. MDA is the final soluble product in the process of membrane lipid peroxidation. The higher the content of MDA, the more severe the damage to the cell membrane system, so the content of MDA is usually used to measure the degree of oxidative stress [38,39]. SOD and POD are the main antioxidant enzymes involved in scavenging ROS and reducing damage to the membrane system. In the current study, after low-dose NPs-Se treatment, the activities of SOD and POD were significantly enhanced, while the content of MDA was significantly reduced, especially in the first and second harvests. However, in the third harvest, SOD activity was not significantly affected compared to T0, while POD activity was significantly increased at lower doses. Under the high concentration treatment (250 mg·L−1), POD activity was inhibited. This shows that POD activity is more sensitive than SOD activity to NPs-Se treatment. In the third harvest, POD activity was significantly increased after Se concentration treatment in T1 (30 mg·L−1) compared with T0 (0 mg·L−1), while MDA content was significantly decreased. This shows that POD is more effective than SOD in scavenging ROS and reducing MDA content. This finding is consistent with the studies by Bai et al. [31] and Duan et al. [33]. The response of SOD activity to Se may be related to the change of SOD gene transcription level. Studies have shown that Se can significantly affect the transcription level of CuZn-SOD in chloroplast of potato plants under light stress [40]. When the Se application level was higher than the toxicity threshold, POD activity decreased significantly, which may be due to the stress caused by high Se on leaves beyond the regulation of antioxidant system and the accumulation of ROS [31,41]. In short, it is not suitable to apply high concentration of NPs-Se to alfalfa harvested more than once a year. At the same time, the application of an appropriate amount of NPs-Se can improve the antioxidant capacity, which also provides a new insight for alfalfa cultivation in adverse environments, such as saline and alkali soils.

Plants may contain selenoprotein structures similar to thioredoxin and iron–sulfur protein involved in the regulation of chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis [42,43]. In this study, photosynthetic pigments first increased and then decreased with increasing Se concentration, which was consistent with the results of Lin et al. [27] and Hawrylak-Nowak [44]. Over three harvests, low concentrations of NPs-Se significantly increased chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids, and total chlorophyll content, especially at the T2 (50 mg·L−1) concentration. This also explains why the yield under T2 (50 mg·L−1) concentration was higher than that under other treatments. It may be that low concentrations of Se can protect chlorophyll and PS II functions from oxidative damage through up-regulation of antioxidants [45,46]. However, high Se has adverse effects on porphobilinogen synthase required for chlorophyll biosynthesis and inhibits biosynthesis by lipid peroxidation [47]. In the first harvest, the concentration of NPs-Se had the greatest effect on carotenoids, followed by effects on chlorophyll b, showing a contrasting trend to that for MDA content. This result indicates that carotenoids are efficient antioxidants that scavenge peroxyl radicals and singlet molecular oxygen in plants, thus protecting photosynthetic membranes from photooxidation [48,49]. Wang et al. found no significant effect of foliar spraying of higher concentrations of Se on the carotenoid content of alfalfa, a result similar to the present study in the first harvest and different from our results in the second harvest [50]. The reason for this may be that in the second harvest, the high concentration of Se damaged the plant and stimulated increased carotenoid content to mitigate this damage. In the third harvest, T2 (50 mg·L−1) concentration had insignificant effects on carotenoid and chlorophyll b content compared with T0 but had a significant effect on chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll content. This shows that the response of chlorophyll b to NPs-Se was initially stronger than that of chlorophyll a. It may be that chlorophyll b is a branch of the synthesis pathway of chlorophyll a. An appropriate Se concentration in the early stage will promote chlorophyll an oxygenase to synthesize chlorophyll b, and oxygen will be involved at the same time [51,52]. It could also be that Se increases stomatal conductance, facilitates the entry of oxygen, and speeds up the process [21,53]. However, this effect may gradually weaken with repeated application of Se, thereby promoting the synthesis of chlorophyll a.

Due to the different units of each index assessed, in order to facilitate the comprehensive evaluation of each treatment, it is common to quantify each index by using a function. Andrews et al. compared index methods composed of different indicator selection methods with scoring functions (linear and non-linear) for vegetable production systems [54]. PCA is a common method of multivariate statistical analysis [55]. Our study suggests that it was reasonable to combine PCA with the curve function to comprehensively evaluate alfalfa after each treatment. In this study, the indicators of alfalfa treated with NPs-Se concentration were comprehensively evaluated to determine the optimal Se concentration. T2 scored the highest, indicating the best overall effect after treatment.

5 Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to investigate the biofortification effect of different concentrations of NPs-Se on multiple harvested alfalfa. The results showed that under long-term bioaugmentation, the application of low concentration of NPs-Se could increase chlorophyll content, carotenoid content, SOD activity, and POD activity of alfalfa, and reduce MDA content, thereby limiting the damage to plants from external factors and achieving the purpose of increasing yield. The positive effects of the T2 (50 mg·L−1) concentration treatment were the most obvious. Our results further suggest that the application concentration of NPs-Se can be appropriately increased in the second harvest, thereby increasing the cumulative amount of Se. However, prior to the realization of large-scale practical projects, further research on the utilization of NPs-Se and its existing forms in plants is needed to determine the effectiveness of NPs-Se.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Key Laboratory of Forage Cultivation, Processing and High Efficient Utilization of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the Key Laboratory of Grassland Resources of Ministry of Education, the Program for Technology Project of Inner Mongolia (2021GG0109), and the National Dairy Technology Innovation Center (2021-National Dairy Innovation Center-1), China.

-

Author contributions: Pengbo Sun: writing – original draft, investigation, formal analysis; Zhijun Wang, Ning Yuan, Qiang Lu, and Lin Sun: writing – review and editing, formal analysis; Yuyu Li, Jiawei Zhang, and Yuhan Zhang: writing – review and editing, investigation; Gentu Ge and Yushan Jia: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data are presented within the article.

References

[1] Abd Elghany Hefnawy R, Revilla-Vázquez A, Ramírez-Bribiesca E, Tórtora-Pérez J. Effect of pre-and postpartum selenium supplementation in sheep. J Anim Vet Adv. 2008;7:61–7. 10.2460/javma.232.1.98.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Duntas LH, Benvenga S. Selenium: an element for life. Endocrine. 2015;48:756–75. 10.1007/s12020-014-0477-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Kieliszek M. Selenium–fascinating microelement, properties and sources in food. Molecules. 2019;24:1298. 10.3390/molecules24071298.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Stevens J, Olson W, Kraemer R, Archambeau J. Serum selenium concentrations and glutathione peroxidase activities in cattle grazing forages of various selenium concentrations. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:1556–60. 10.2754/avb198554010091.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Thavarajah D, Thavarajah P, Vial E, Gebhardt M, Lacher C, Kumar S, et al. Will selenium increase lentil (Lens culinaris Medik) yield and seed quality? Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:356. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Acuña JJ, Jorquera MA, Barra PJ, Crowley DE, de la Luz Mora M. Selenobacteria selected from the rhizosphere as a potential tool for Se biofortification of wheat crops. Biol Fertil Soils. 2013;49:175–85. 10.1007/s00374-012-0705-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Poblaciones MJ, Rodrigo SM, Santamaría O. Evaluation of the potential of peas (Pisum sativum L.) to be used in selenium biofortification programs under Mediterranean conditions. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;151:132–7. 10.1007/s12011-012-9539-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Premarathna L, McLaughlin MJ, Kirby JK, Hettiarachchi GM, Stacey S, Chittleborough DJ. Selenate-enriched urea granules are a highly effective fertilizer for selenium biofortification of paddy rice grain. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:6037–44. 10.1021/jf3005788.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] El-Ramady H, Abdalla N, Fári M, Domokos-Szabolcsy É. Selenium enriched vegetables as biofortification alternative for alleviating micronutrient malnutrition. Int J Hortic Sci. 2014;20:75–81. 10.31421/IJHS/20/1-2/1121.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Zhu Z, Chen Y, Shi G, Zhang X. Selenium delays tomato fruit ripening by inhibiting ethylene biosynthesis and enhancing the antioxidant defense system. Food Chem. 2017;219:179–84. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.138.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Navarro-Alarcon M, Cabrera-Vique C. Selenium in food and the human body: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2008;400:115–41. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.024.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Chauhan R, Awasthi S, Srivastava S, Dwivedi S, Pilon-Smits EA, Dhankher OP, et al. Understanding selenium metabolism in plants and its role as a beneficial element. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2019;49:1937–58. 10.1080/10643389.2019.1598240.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang J, Gao X, Zhang L, Bao Y. Biological effects of a nano red elemental selenium. BioFactors. 2001;15:27–38. 10.1002/biof.5520150103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wang H, Zhang J, Yu H. Elemental selenium at nano size possesses lower toxicity without compromising the fundamental effect on selenoenzymes: comparison with selenomethionine in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1524–33. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Sa DW, Lu Q, Wang Z, Ge G, Sun L, Jia Y. The potential and effects of saline-alkali alfalfa microbiota under salt stress on the fermentation quality and microbial. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:1–10. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-113684/v1.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Lu Q, Wang Z, Sa D, Hou M, Ge G, Wang Z, et al. The potential effects on microbiota and silage fermentation of alfalfa under salt stress. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:688695. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.688695.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Huang Z, Liu Y, Cui Z, Fang Y, He H, Liu B-R, et al. Soil water storage deficit of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) grasslands along ages in arid area (China). Field Crop Res. 2018;221:1–6. 10.1016/j.fcr.2018.02.013.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Owusu-Sekyere A, Kontturi J, Hajiboland R, Rahmat S, Aliasgharzad N, Hartikainen H, et al. Influence of selenium (Se) on carbohydrate metabolism, nodulation and growth in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant Soil. 2013;373:541–52. 10.1007/s11104-013-1815-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Thornton PK, Herrero M. Climate change adaptation in mixed crop–livestock systems in developing countries. Glob Food Secur. 2014;3:99–107. 10.1016/j.gfs.2014.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Ekanayake LJ, Vial E, Schatz B, McGee R, Thavarajah P. Selenium fertilization on lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) grain yield, seed selenium concentration, and antioxidant activity. Field Crop Res. 2015;177:9–14. 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Zhang M, Tang S, Huang X, Zhang F, Pang Y, Huang Q, et al. Selenium uptake, dynamic changes in selenium content and its influence on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ Exp Bot. 2014;107:39–45. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Kápolna E, Laursen KH, Husted S, Larsen EH. Bio-fortification and isotopic labelling of Se metabolites in onions and carrots following foliar application of Se and 77Se. Food Chem. 2012;133:650–7. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.043.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Nawaz F, Ahmad R, Ashraf M, Waraich E, Khan S. Effect of selenium foliar spray on physiological and biochemical processes and chemical constituents of wheat under drought stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;113:191–200. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Kápolna E, Hillestrøm PR, Laursen KH, Husted S, Larsen EH. Effect of foliar application of selenium on its uptake and speciation in carrot. Food Chem. 2009;115:1357–63. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.054.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Astaneh RK, Bolandnazar S, Nahandi FZ, Oustan S. The effects of selenium on some physiological traits and K, Na concentration of garlic (Allium sativum L.) under NaCl stress. Inf Process Agric. 2018;5:156–61. 10.1016/j.inpa.2017.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Zhou F, Peng Q, Wang M, Liu N, Dinh QT, Zhai H, et al. Influence of processing methods and exogenous selenium species on the content and in vitro bioaccessibility of selenium in Pleurotus eryngii. Food Chem. 2021;338:127661. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127661.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Lin L, Sun J, Cui T, Zhou X, Liao MA, Huan Y, et al. Selenium accumulation characteristics of Cyphomandra betacea (Solanum betaceum) seedlings. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2020;26:1375–83. 10.1007/s12298-020-00838-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Feng R, Wei C. Antioxidative mechanisms on selenium accumulation in Pteris vittata L., a potential selenium phytoremediation plant. Plant Soil Environ. 2012;58:105–10. 10.1007/s00271-011-0278-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Zhang J, Kirkham M. Drought-stress-induced changes in activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase in wheat species. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994;35:785–91. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078658.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Chen Y, Wang H, Zhou J, Xing L, Zhu B, Zhao Y, et al. Minimum data set for assessing soil quality in farmland of northeast China. Pedosphere. 2013;23:564–76. 10.1016/S1002-0160(13)60050-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Bai B, Wang Z, Gao L, Chen W, Shen Y. Effects of selenite on the growth of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L. cv. Sadie 7) and related physiological mechanisms. Acta Physiol Plant. 2019;41:1–11. 10.1007/s11738-019-2867-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Xia Q, Yang Z, Shui Y, Liu X, Chen J, Khan S, et al. Methods of selenium application differentially modulate plant growth, selenium accumulation and speciation, protein, anthocyanins and concentrations of mineral elements in purple-grained wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1114. 10.3389/fpls.2020.01114.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Duan M, Fu D, Wang S, Wang D, Xue R, Wu X. Effects of different selenite concentrations on plant growth, absorption and transportation of selenium in four different vegetables. Acta Sci Circum. 2011;31:658–65. 10.3724/SP.J.1011.2011.00468.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Huang K, Wang Y, Wei X, Bie Y, Zhou H, Deng L, et al. Effects of mutual grafting Solanum photeinocarpum from two ecosystems on physiology and selenium absorption of their offspring under selenium stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2021;43:96. 10.1007/s11738-021-03269-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Di X, Qin X, Zhao L, Liang X, Xu Y, Sun Y, et al. Selenium distribution, translocation and speciation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) after foliar spraying selenite and selenate. Food Chem. 2023;400:134077. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134077.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zhang H, Li X, Guan Y, Li M, Wang Y, An M, et al. Physiological and proteomic responses of reactive oxygen species metabolism and antioxidant machinery in mulberry (Morus alba L.) seedling leaves to NaCl and NaHCO3 stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;193:110259. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110259.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kaiwen G, Zisong X, Yuze H, Qi S, Yue W, Yanhui C, et al. Effects of salt concentration, pH, and their interaction on plant growth, nutrient uptake, and photochemistry of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) leaves. Plant Signal Behav. 2020;15:1832373. 10.1080/15592324.2020.1832373.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] McKay H, Mason W. Physiological indicators of tolerance to cold storage in Sitka spruce and Douglas-fir seedlings. Can J For Res. 1991;21:890–901. 10.1139/x91-124.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Lou Y, Guan R, Sun M, Han F, He W, Wang H, et al. Spermidine application alleviates salinity damage to antioxidant enzyme activity and gene expression in alfalfa. Ecotoxicology. 2018;27:1323–30. 10.1007/s10646-018-1984-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Seppänen M, Turakainen M, Hartikainen H. Selenium effects on oxidative stress in potato. Plant Sci. 2003;165:311–9. 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00085-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Noctor G, Foyer CH. Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 1998;49:249–79. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] El-Ramady H, Abdalla N, Taha HS, Alshaal T, El-Henawy A, Faizy SEDA, et al. Selenium and nano-selenium in plant nutrition. Environ Chem Lett. 2015;14:123–47. 10.1007/s10311-015-0535-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Gupta M, Gupta S. An overview of selenium uptake, metabolism, and toxicity in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:2074. 10.3389/fpls.2016.02074.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Hawrylak-Nowak B. Beneficial effects of exogenous selenium in cucumber seedlings subjected to salt stress. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;132:259–69. 10.1007/s12011-009-8402-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Djanaguiraman M, Prasad PV, Seppanen M. Selenium protects sorghum leaves from oxidative damage under high temperature stress by enhancing antioxidant defense system. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:999–1007. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.09.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Trippe IRC, Pilon-Smits EAH. Selenium transport and metabolism in plants: phytoremediation and biofortification implications. J Hazard Mater. 2021;404:124178. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124178.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Saffaryazdi A, Lahouti M, Ganjeali A, Bayat H. Impact of selenium supplementation on growth and selenium accumulation on spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) plants. Not Sci Biologicae. 2012;4:95–100. 10.15835/nsb.4.4.8029.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Stahl W, Sies H. Antioxidant activity of carotenoids. Mol Asp Med. 2003;24:345–51. 10.1016/S0098-2997(03)00030-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Strzałka K, Kostecka-Gugała A, Latowski D. Carotenoids and environmental stress in plants: significance of carotenoid-mediated modulation of membrane physical properties. Russ J Plant Physl. 2003;50:168–73. 10.1023/A:1022960828050.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Wang YD, Wang X, Ngai SM, Wong YS. Comparative proteomics analysis of selenium responses in selenium-enriched rice grains. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:808–20. 10.1021/pr300878y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Tsuchiya T, Mizoguchi T, Akimoto S, Tomo T, Tamiaki H, Mimuro M. Metabolic engineering of the Chl d-dominated cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina: production of a novel Chl species by the introduction of the chlorophyllide a oxygenase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:518–27. 10.1093/pcp/pcs007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Chew AGM, Bryant DA. Chlorophyll biosynthesis in bacteria: the origins of structural and functional diversity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:113–29. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093242.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Jiang C, Zu C, Shen J, Shao F, Li T. Effects of selenium on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of flue-cured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2015;84:71–7. 10.5586/asbp.2015.006.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Andrews SS, Karlen D, Mitchell J. A comparison of soil quality indexing methods for vegetable production systems in Northern California. Agric, Ecosyst Environ. 2002;90:25–45. 10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00174-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Croux C, Filzmoser P, Fritz H. Robust sparse principal component analysis. Technometrics. 2013;55:202–14. 10.2139/SSRN.1868107.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles