Abstract

In this study, a simple green method was employed to produce strontium (Sr)-doped-tin-dioxide (SnO2) nanoparticles (SrSnO2 NPs) using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract. The synthesized NPs were characterized with XRD, FE-SEM, FTIR, and PL spectroscopy measurements. SrSnO2 NPs were analysed for antimicrobial and anticancer activities. The XRD analysis revealed that the synthesized samples exhibited a tetragonal rutile crystal structure type of tin oxide. The EDX spectrum conforms to the chemical composition and elemental mapping of SrSnO2 NP synthesis. At 632 cm−1, the O–Sn–O band was observed and chemical bonding was confirmed using an FTIR spectrum. The PL spectrum identified surface defects and oxygen vacancies. The SrSnO2 NPs were tested against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative human pathogens. The synthesized nanoparticles exhibited effective antibacterial properties. The anticancer effects of SrSnO2 nanoparticles were also assessed against MCF-7 cells, and growth was decreased with increasing concentrations of the nanoparticles. Dual staining revealed high apoptosis in SrSnO2 NP-treated MCF-7 cells, proving its apoptotic potential. To conclude, we synthesized and characterized potential SrSnO2 nanoparticles using a green approach from the Mahonia bealei leaf extract. Further, green SrSnO2 nanoparticles showed significant antibacterial and anticancer properties against breast cancer cells (MCF-7) through apoptosis, which suggests a healthcare application for these nanoparticles.

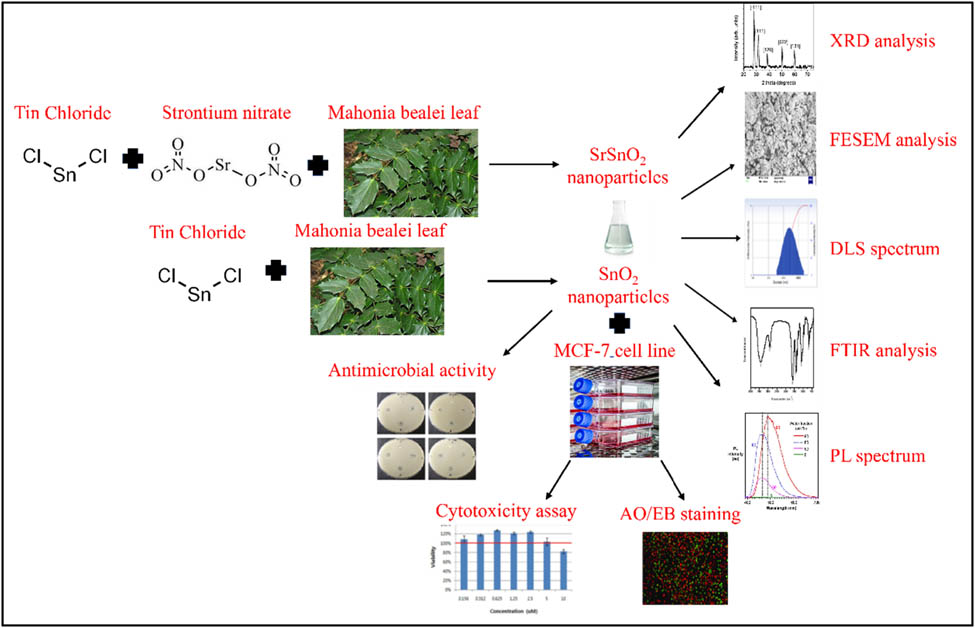

Graphical abstract

An overview of the study presented in a schematic form.

Abbreviations

- SrSnO2 NPs

-

strontium (Sr)-doped tin dioxide nanoparticles

- UV

-

ultraviolet

- XRD

-

X-ray diffraction

- SEM

-

scanning electron microscopy

- TEM

-

transmission electron microscopy

- MG/L

-

part per million

1 Introduction

Tin oxide nanoparticles (SnO2 NPs) have recently received increasing interest due to their extraordinary chemical, physical, and biological properties, most notably their excellent antibacterial activity. It is an N-type semiconductor with a wide bandgap and the most promising material owing to its unique physicochemical properties. On the other hand, those methods require more energy and are more expensive. Additionally, both environmental and human health hazardous chemicals have been employed for tin oxide nanoparticle synthesis. As a result, there is a necessity to create safer eco-friendly tin oxide synthesis methods that avoid unsafe solvents and chemicals while maximizing the use of natural biodegradable materials [1].

Mahonia bealei is a significant member of the Mahonia genus and is widely employed in traditional Chinese medicine. Many bioactive compounds have been extracted from this plant and have beneficial properties. It is an ethnomedicinal plant [2] and therefore utilized in a variety of nations, including India, Malaysia, Mauritius, Bangladesh, Nepal, Mozambique, and Oman for abortion, asthma, constipation, diarrhoea, earache, epilepsy, fever, ganglion, gum, and teeth disease, insect bites, headaches, decreased sugar levels, a mouth ulcer, acne, inflammatory bowel disease, syphilis, and healing of wounds, as well as an anti-helminthic, anti-parasite, aphrodisiac, dermatology ailment, emmenagogue, expectorant, and laxative [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) has acknowledged that a reliable source of medicinal plants for traditional medicinal practices is based on plant sources for therapeutic applications [12].

The photocatalytic properties of tin oxide nanomaterials are highly promising candidates for microbial and cancer cell inactivation. Nanomaterials generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and are strongly linked to antibacterial and anticancer activity [13]. This is because of their large surface areas, increased oxygen vacancies, reactant molecule diffusion, and active ion release. When tin oxide nanomaterials come into contact with light, they induce oxidative stress in cells, which leads to bacterial and cancer cell death. Tin oxide has, therefore, been employed to synthesize nanomaterials from both organic and inorganic substances due to these factors [14].

These ethnomedicinal plants can grow along the side of the road, in outdoor play areas, and in house compounds throughout settlements. In addition, they can be found in the wild or cultivated for personal use by some people. Moreover, the leaves contain valuable phytochemicals including alkaloids, anthraquinone, catechol, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, steroids, triterpenoids, and tannins [15]. The alkaline-earth metal was doped with tin oxide to enhance its physical, chemical, and biological properties. Technological applications can be expanded by doping with foreign metal ions. According to a literature report, charge compensation and ionic radius differences may arise through the doping of alkaline earth metals (Mg2+, Ba2+, Sr2+), which can further boost the antibacterial activity [16].

In this study, the synthesis of alkaline-earth metal strontium-doped tin oxide NPs utilizing a simple green method has been carried out, which could increase optical efficiency. These nanoparticles open up additional opportunities for incorporating oxide nanoparticles into tin oxide. This will support a variety of fundamental and advanced concepts in a variety of applications. Though some research has been performed on the optical, antibacterial, and anticancer activity of SrSnO2 NPs, there has been only limited research on the structural, optical, and antibacterial behaviours of SrSnO2. As a result, we attempted to verify the impact of variations caused by the amalgamation of Sr ions into the tin oxide lattice site. Tin oxide NPs also play an important role in antibacterial and anticancer activities [17,18]. Previous studies reported that green synthesized cerium-doped tin oxide (Ce-SnO2) nanoparticles exhibit talented anticancer effects against several tumours [19].

To synthesize and evaluate the properties of Sr ions on the structural, morphological, and elemental properties of SrSnO2 nanoparticles, a Sr ion on tin oxide nanoparticles was hypothesized. Molecular characterization of SrSnO2 NPs was performed using several characterization techniques. The antimicrobial properties of SrSnO2 NPs were investigated. Additionally, their ability to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells by inducing cytotoxicity has been investigated. The synthesized nanoparticles were further tested for their efficacy in inducing cytotoxicity via promoting apoptosis on MCF-7 cells.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Chemicals such as tin chloride and strontium nitrate were acquired from Sigma Aldrich, USA. All the other required chemicals and reagents attained were of the analytical category.

2.2 Synthesis of green SrSnO2 nanoparticles

Tin chloride and strontium nitrate were utilized as precursors without additional purification. Approximately, 10 g of fresh M. bealei leaves was boiled with deionized water (100 mL) for 10 min at 50–60°C. The suspension was filtered; in 100 mL of the M. bealei leaf extract, 0.2 M tin oxide was dissolved. For 6 h, this aqueous extract of tin chloride and M. bealei leaf was constantly shaken at 80°C. This resulted in a black precipitate, which was dried at 120°C. Similarly, 0.2 M tin chloride and 0.1 M strontium nitrate were dissolved in 100 mL of M. bealei leaf extract to synthesize SrSnO2. On continuous stirring, a white precipitate was formed. This solution was constantly shaken for 6 h at 80°C. SrSnO2 was obtained by drying the precipitate at 120°C. Finally, the nanopowder was annealed for 5 h at 800°C. As a result, tin oxide and SrSnO2 NPs were produced [20].

2.3 Characterization of SrSnO2 nanoparticles

An X’PERT PRO PANalytical XRD was employed to characterize the SrSnO2 NPs. Diffraction patterns between 25° and 80° were recorded with a monochromatic wavelength of 1.54. A NanoPlus DLS Nano Particle Sizer was utilized for the particle size comparison of SrSnO2 NPs. FE-SEM (Carl Zeiss Ultra-55 FESEM) with EDAX and mapping analysis was employed to investigate the samples (model: Inca). A Perkin-Elmer spectrometer was utilized to obtain FT-IR spectra in the range of 400–4,000 cm−1. The Cary Eclipse spectrometer was used to measure photoluminescence (PL) spectra [21].

2.4 Antibacterial activity of SrSnO2 NPs

The well diffusion technique was used to determine the antibacterial properties of SrSnO2 NPs against Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia, and Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative (Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, and Vibrio cholerae) strains. To ensure homogeneous distribution of the inoculums, the bacteria were streaked onto the media plates (NA) twice, with each streak being rotated at 60°. After inoculation, sterile forceps were used to place wells containing 1, 1.5, and 2 mg·mL−1 SrSnO2 NPs on the bacteria-inoculated plates. After that, the plates were incubated at 37℃ for 24 h. Around the discs, the inhibition zone was noted and recorded. The positive control was amoxicillin (Hi-Media), which was tested against pathogens to compare the efficacy of the test samples.

2.5 Culturing of MCF-7 cells

The MCF-7 cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 1% antibiotics and 10% FBS. The culture medium with cells was incubated at 37°C by supplying 5% CO2. A trypsin-EDTA solution containing 0.25% trypsin was used to perform experiments with sub-cultured cells at 80% confluency.

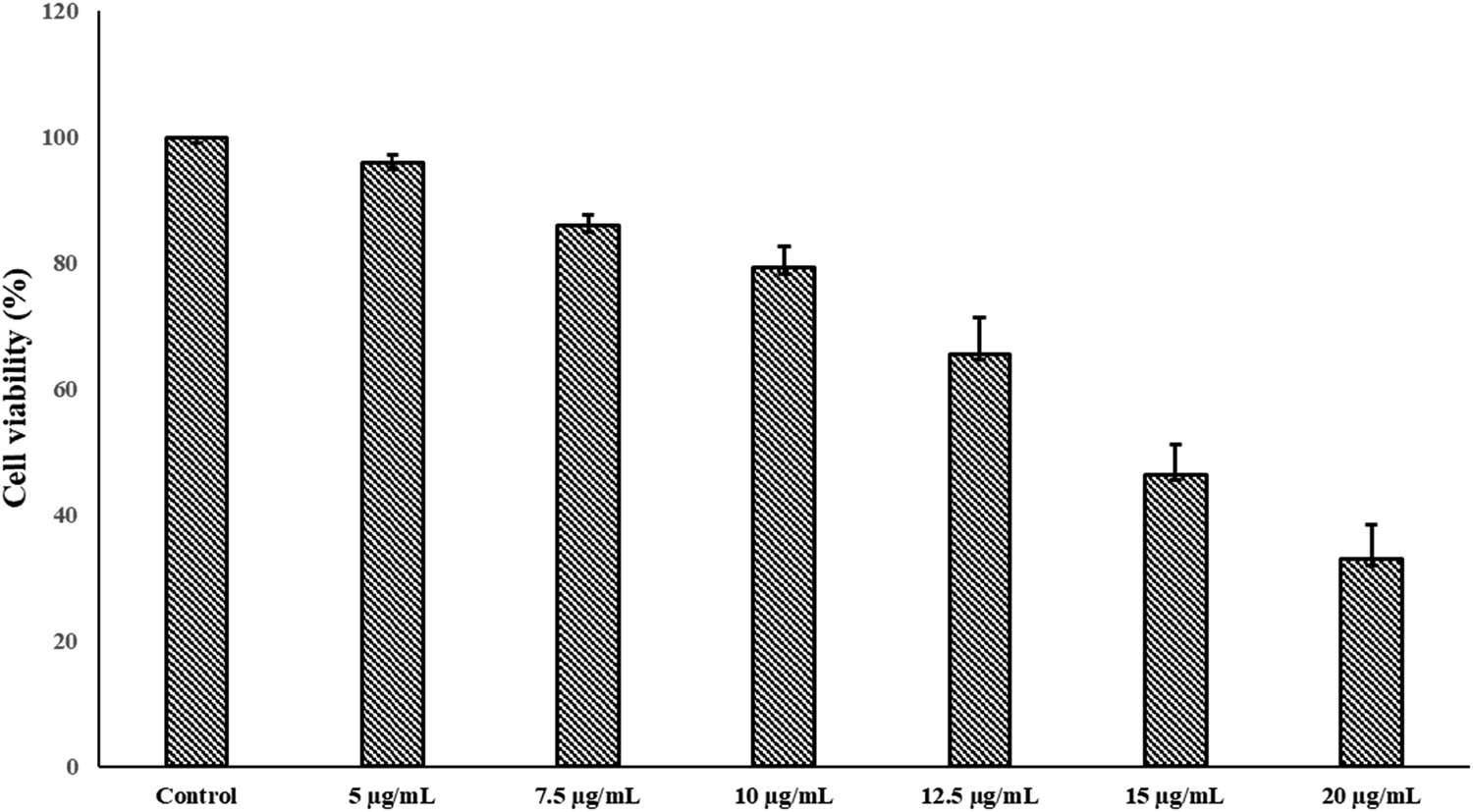

2.6 MTT assay

After seeding and incubating for 24 h at 37°C, the breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells were plated into a 96-well plate. SrSnO2 NPs were applied in different dosages to the cells after the incubation period (5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, and 20 µM·mL−1) for 24 h. The medium was later discarded; after adding serum-free culture medium to each well and MTT solution, the cells were incubated at 37°C in the dark for 3 h. The plates were incubated for 15 min after 150 µL of MTT was added to every well. The OD values in three replicates of each concentration were measured at 595 nm and used to determine the percentage of viable cells [22].

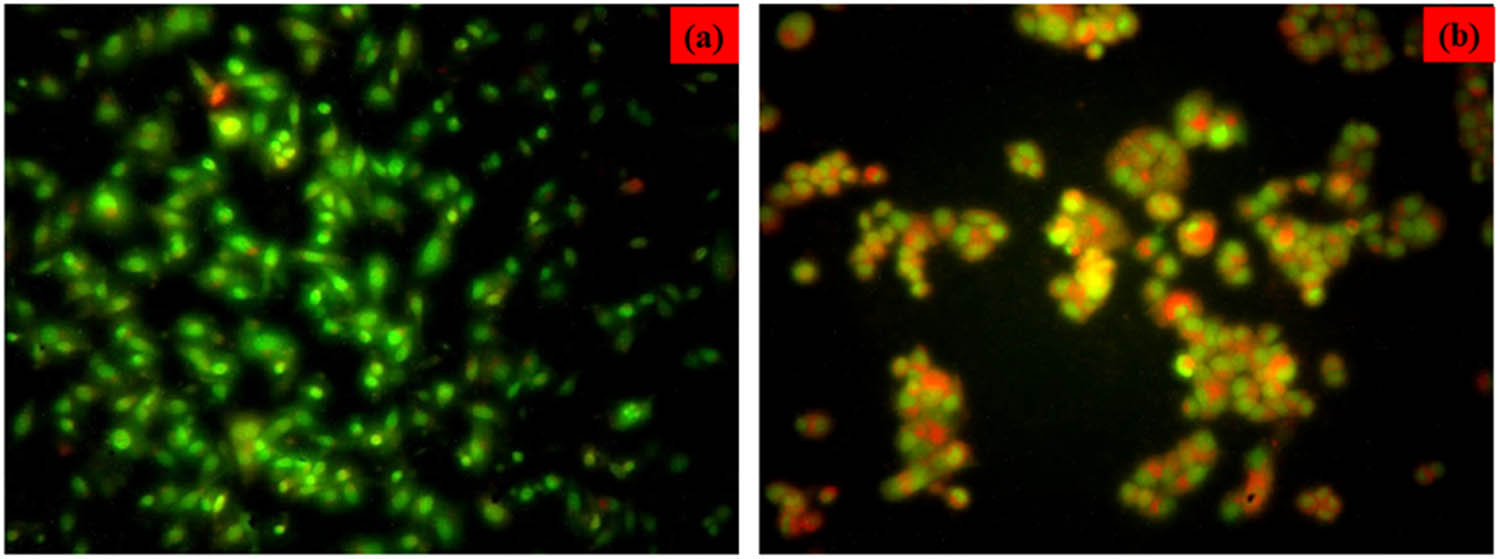

2.7 Dual staining assay

Dual staining using AO/EtBr stain was performed to evaluate the apoptotic potential of SrSnO2 NPs in breast carcinoma cells, MCF-7. A 7.5 and 15 µM solution of SrSnO2 NPs were used to treat the cells for 24 h. Then, the cells were rinsed with PBS and stained with a mixture of AO/EtBr (1:1). A fluorescence microscope was utilized to examine the stained cells [23].

2.8 Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 6.02 software was employed to examine the values after the experiments were conducted. We analysed the data with a one-way ANOVA and subsequently the post hoc Duncan’s test; significance we fixed at P < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of SrSnO2 nanoparticles

The ultraviolet-visible absorbance spectrum of SrSnO2 NPs is shown in Figure 1a. The absorption band edge values of the synthesized SrSnO2 NPs were observed at 394 nm [24]. With the help of Planck’s formula,

where E g is the band-gap energy (eV), h is Planck’s constant (= 4.1357 × 10−15 eV s), and λ is the wavelength (nm). The band gap of nanomaterials was calculated in eV. Varshney et al. reported that the band gap of tin oxide/NiO2 NPs was 3.132 eV compared to 3.3 eV for pure tin oxide NPs [25]. In the present work, a band gap of 3.1468 eV was observed for SrSnO2 nanocomposites. The bandgap values of SrSnO2 NPs are lower compared to that of tin oxide [26]. The effect of different energy states in the valence band and conduction band of tin oxide is linked to a decrease in the band gap of NPs. As Sr2+ is added to the tin oxide lattice, oxygen vacancies are occupied to keep the local charge neutral, leading to these different energy states.

Spectral analysis of SrSnO2 NPs: (a) UV-Vis spectrum, (b) FTIR spectrum, and (c) PL spectrum.

The wavenumbers 3,424, 2,923, and 2,853 cm−1 represent the stretching vibrations of O–H, and asymmetric and symmetric stretching of C–H, respectively. The aromatic functional groups are involved in the nanoparticle’s reduction process observed at 1,639 and 1,561 cm−1 representing the primary amino acids I and II, respectively. The peaks ranging from 1,457 to 1,384 cm−1 represent the stretching vibrations of phenol (O–H) and C–H. The secondary amine found at 1,112 cm−1 acts as a capping agent. The C–O stretching changes were observed at 1,059 and 1,033 cm−1. In the Sn–O mode, stretching was observed at 662 and 520 cm−1. The FT-IR results display the presence of carboxyl (C–O), phenol (O–H), and proteins (amino acids) on the nanoparticle surface [27]. SrSnO2 NPs were reduced and then stabilized by these phytocomponents (Figure 1b).

The PL spectrum of SrSnO2 NPs with an excitation wavelength of 380 nm is shown in Figure 1c. The peaks in the PL emission spectrum of the SrSnO2 sample were found at 413, 442, 465, 482, 499, and 522 nm. The violet emission, found at 413 nm, is accredited to the electron transition from the natural zinc interstitials’ shallow donor level to the valence band’s top level [28]. The blue emission peaks observed at 442, 465, 482, and 499 nm are allocated to single ionized Zn vacancies [29]. Finally, the green emission peak is located at 522 nm, and this emission corresponds to the single ionized oxygen vacancy [30].

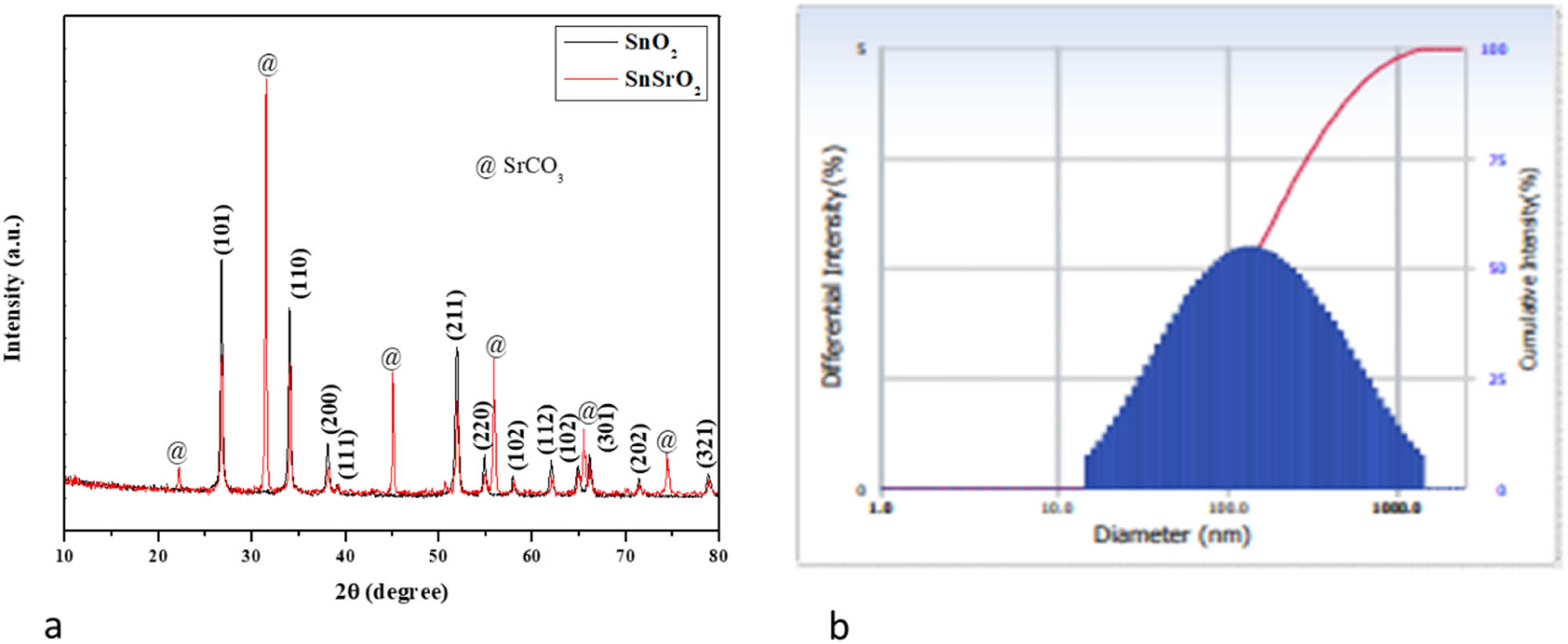

Figure 2a represents the XRD pattern of the tin oxide and SrSnO2 NPs that were synthesized using the green approach. Tin oxide NPs have XRD peaks that appear at angles (2θ) of 26.53°, 33.94°, 37.95°, 38.94°, 51.99°, 54.87°, 57.99°, 62.01°, 64.64°, 66.15°, 71.42°, and 78.93°, and they correspond to the planes (110), (101), (201), (220), (220), (102), (301), respectively (JCPDS No. 41-1445). In addition, as per the JCPDS file No. 74-1491, the presence of some secondary phases associated with orthorhombic SrCO3 [space group: Pmcn (62)] was discovered:

where λ is the X-ray wavelength (= 1.54060), β is the angular peak width at half maximum (in rad), and θ is Bragg’s diffraction angle. The average crystallite sizes of tin oxide and SrSnO2 NPs were calculated to be 35.2 and 27.3 nm, respectively.

X-ray diffraction (a) and DLS (b) pattern of SnO2 and SrSnO2 NPs.

The hydrodynamic diameter of SrSnO2 NPs was determined using dynamic light scattering to obtain the particle size (Figure 2b). The size of SrSnO2 NPs was 143 nm; as the water medium surrounded the NPs, the DLS particle size was higher than XRD and TEM findings and is called hydrodynamic size.

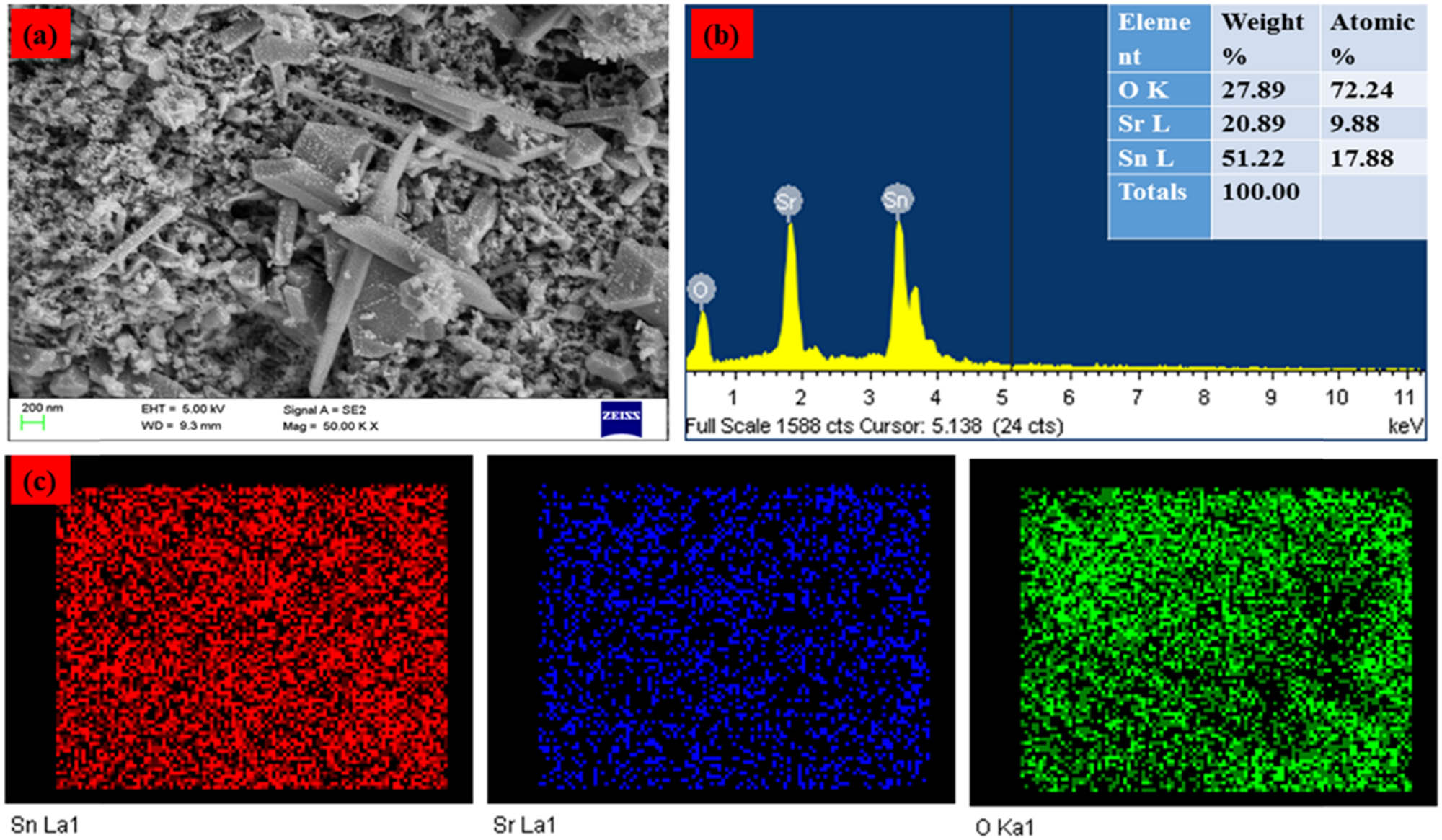

The morphology, chemical composition, and elemental mapping of the synthesized SrSnO2 NPs are shown in Figure 3a–c. As shown in the FESEM images, SrSnO2 NPs exhibit a nanorod structure (Figure 3a). The average particle size was 200 nm. The chemical composition of SrSnO2 NPs was demonstrated using the EDAX spectra and is shown in Figure 3b. In SrSnO2 nanocomposites, the atomic percentages were as follows: 17.88% Sn, 9.88% Sr, and 72.24% O. The elemental mapping analysis revealed the presence of Sn, Sr, and O (Figure 3c). The NPs of SrSnO2 exhibited uniform distribution of Sn, Sr, and O atoms throughout the structure.

(a) FESEM image. (b) EDAX and (c) elemental mapping analysis of SrSnO2 NPs.

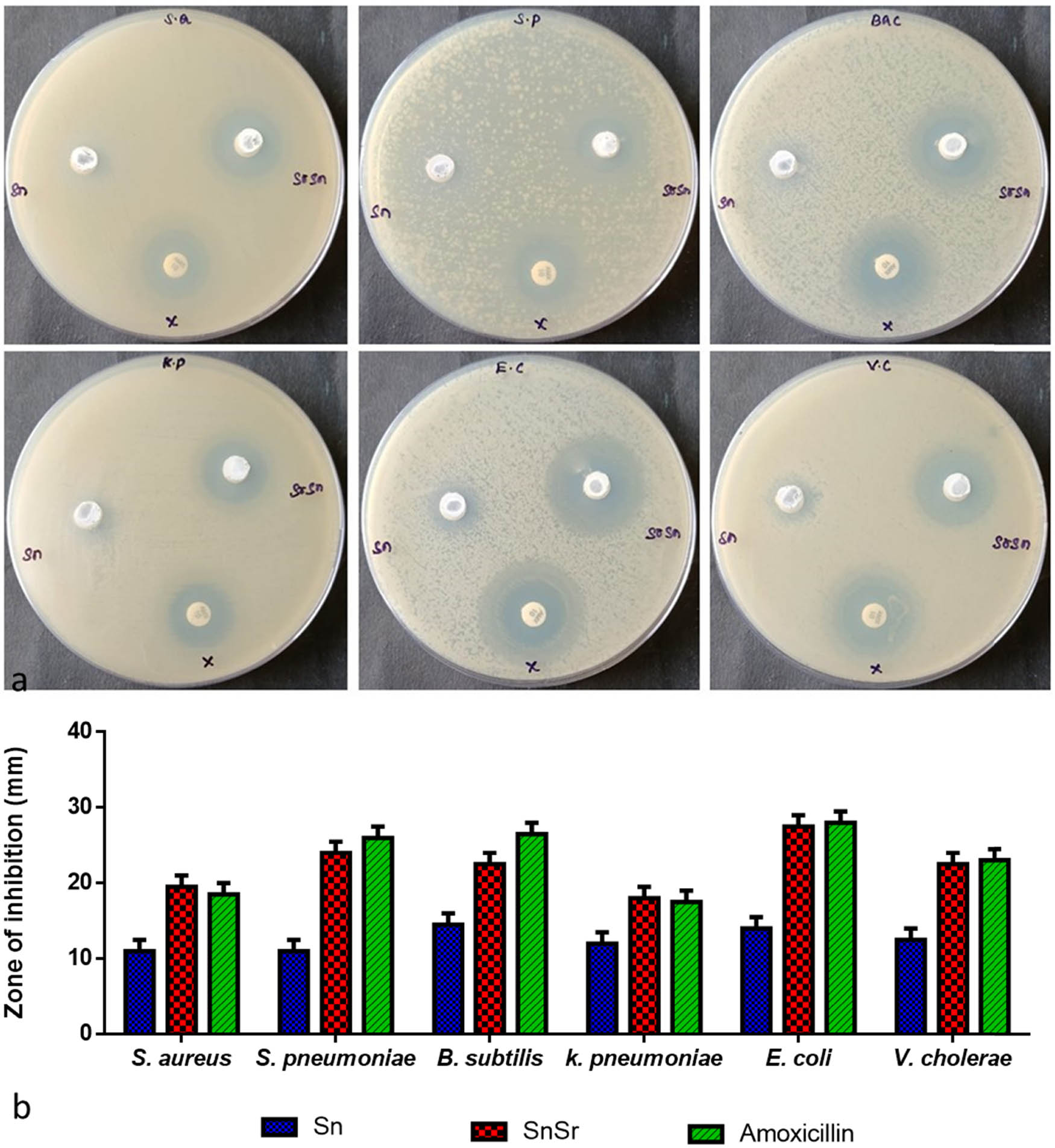

3.2 Antimicrobial activity of SrSnO2 NPs

The tin oxide and SrSnO2 NPs were tested against S. aureus, S. pneumonia, B. subtilis, K. pneumonia, E. coli, and V. cholerae pathogens via the agar well diffusion method, as shown in Figure 4a. Figure 4a and b illustrates the zone of inhibition of tin oxide, SrSnO2, and conventional antibiotics such as amoxicillin when treated with the bacterial strains. The SrSnO2 NPs displayed higher antibacterial activity than tin oxide NPs. The bacterial inhibitory mechanism depends on the adsorption–desorption (A–D) and chemical–physical (C–P) activity between the SrSnO2 NPs and various human pathogens. The interaction between the SrSnO2 NPs and the human pathogens leads to distinct antibacterial activity. Each cytoplasmic lipid cell membrane produced A–D and C–P activities when SrSnO2 NPs accumulated on the surface of each microbe. Nanomaterials synthesized through the green approach cause different disturbances on each cellular membrane, leading to cell death. The other antibacterial effects could be because varied amounts of active free radicals (ROSs) were formed on the cell walls during the contact, contributing to varying oxidative stress levels in the cells [31].

Antibacterial effect of SrSnO2 NPs. Zone of inhibition (a) of Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, S. pneumonia, and B. subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (K. pneumonia, E. coli, and V. cholerae) was tested against SrSnO2 NPs. Values represent mean ± SD of three experiments (b).

In previous studies, SnCl2H2O was synthesized from leaf extracts of Aloe barbadensis miller as a precursor for SnO2 nanoparticles. These nanoparticles were found to be spherical and ranged in size from 50 to 100 nm, and they revealed substantial antibacterial properties against E. coli and S. aureus [32]. Green synthesis of SnO2 NPs can also be done efficiently and cheaply using the P. amboinicus leaf extract and SnCl2H2O [33]. A previous study indicated that the Nyctanthes arbortristis (Parijataka) flower extract could reduce and stabilize SnO2 nanoparticles and antimicrobial activity [34]. Previous studies demonstrated the antimicrobial activity of undoped and co-doped SnO2 NPs against B. subtilis, A. flavus, E. coli, A. niger, and C. albicans [35]. In the past, similar studies reported that the formulation of SnO2 NPs using the P. pinnata leaf extract revealed that the flower-like shape of NPs renders antibacterial properties against K. pneumoniae, E. coli, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes, which is comparable and even higher than tin oxide nanoparticles reported in previous studies [36]. Previously, similar studies reported that Ce-doped SnO2 nanoparticles exhibited antimicrobial activity against E. coli and inhibited bacterial growth [37].

3.3 Cell viability assay

In this study, the in vitro cytotoxicity of SrSnO2 NPs against MCF-7 cells was examined. The green-synthesized SrSnO2 NPs were tested against MCF-7 cells. Cell growth decreased with increasing concentrations of SrSnO2 NPs (5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, and 20 µg·mL−1), which led to reduced cell viability. When SrSnO2 NPs were treated with MCF cells for 48 h, the inhibitory concentration (IC50) was 14 µg·mL−1 (Figure 5).

Cytotoxicity effects of SrSnO2 NPs treated with MCF-7 cell line. The data were obtained for the treatment of 24 h and values represent mean ± SD of three experiments.

The particle size of SrSnO2 NPs was 27.3 nm in this study. The XRD and PL results show several interstitial oxygen vacancies (Oi) at 522 nm for the sample’s oxygen vacancies (Ov). The effects of the high number of ROS generated in SrSnO2 NPs are responsible for the change. These defects allow more electron–hole pairs to migrate onto the nanomaterial matrix surface of SrSnO2 NPs. While the electrons and holes can react with the superoxide anion (⋅

Tin oxide NPs were tested for cytotoxicity against liver cancer HepG2 cells using an aqueous extract of A. squamosa, and cells treated with tin oxide nanoparticles were inhibited in a dose- and time-dependent manner due to chromatin breakdown in the nucleus [38]. Tin oxide nanoparticles synthesized from the Piper nigrum seed extract demonstrated increased cytotoxicity against lung (A549) and colorectal (HCT116) cancer cell lines [39]. Tin oxide nanoparticles made from the Pruni spinosae flos aqueous extract exhibited substantial cytotoxicity against lung cancer A549 and CCD-39Lu cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, and the authors reported that the cytotoxicity was related to the accumulation ROS and increased oxidative stress [40]. In previous reports, in vitro cytotoxicity of green-synthesized undoped tin oxide and co-doped tin oxide NPs revealed a substantial mortality rate using the MTT assay, which further showed significant cytotoxicity and apoptosis in MCF-7 cells when compared with normal cell lines such as human lung fibroblast (WI38) and human amnion (WISH). The co-doped tin oxide NPs demonstrated more ROS accumulation than the undoped/doped tin oxide NPs [41].

3.4 Acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining of SrSnO2 NPs

Apoptotic changes and nuclear condensation are involved in SrSnO2 NP cytotoxicity. Fluorescent DNA-binding AO/EB dyes were utilized to detect and quantify apoptosis induction and necrosis formation in MCF-7 cells before and after treatment with SrSnO2 NPs. AO dye was absorbed by both living cells, as indicated by green fluorescence. On the other hand, EB dye only absorbs dead cells (red fluorescence). The bright green nuclei and orange cytoplasm were evenly distributed throughout viable cells. In the early stages of apoptosis, apoptosis-inducing cells appear to have a green-coloured nucleus because their membranes are still intact but their DNA breaks down, resulting in a green-coloured nucleus. A bright orange-coloured nucleus with dense chromatin reveals late apoptotic and necrotic cells (Figure 6a and b). The tin and oxygen vacancies in SrSnO2 NPs are believed to be responsible for anticancer activity, leading to higher ROS production. Because of the composition of SrSnO2 NPs, they can produce significant ROS spontaneously. Reeves et al. [42] reported a similar result, where a nanogel containing curcumin appeared more effective against MDA-MB 231 cells than curcumin alone. HT-29 cells treated with curcumin-containing chitosan NPs (CUR-CS-NPs) and free curcumin at 75 µM also displayed fragmentation of nuclei and irregular edges, clearly indicative of apoptosis [43]. MTT assays of SrSnO2 nanoparticles were performed on MCF-7 cells and the nanoparticles showed potential anticancer activity. Nanoparticles also caused cancer cell death through apoptosis when stained with AO/EtBr. Overall, the nanoparticles demonstrated greater anticancer activity than tin oxide alone.

Apoptotic morphology of MCF-7 cells induced by SrSnO2 NPs. (a) Control and (b) breast cancer (MCF-7) cells treated with IC50 concentration of SrSnO2 NPs (14 μg·mL−1) for 24 h and stained with dual dye AO/EB.

4 Conclusion

An eco-friendly green approach was employed to synthesize SrSnO2 NPs, in which the Mahonia bealei leaf extract was used as a reducing and capping agent. The phase analysis results showed a tetragonal rutile-type structure and an average crystallite size of 27.3 nm. When compared to pure tin oxide crystals, SrSnO2 NPs were reduced in size. UV absorption band edge values were observed at 394 nm. Moreover, the PL spectrum showed that a lot of oxygen vacancies induced ROS production and cell death. SrSnO2 NPs displayed higher antibacterial activity than pure tin oxide nanoparticles. In addition, SrSnO2 nanoparticles exhibited potent anticancer effects against breast cancer MCF-7 cells. In the near future, we believe that SrSnO2 nanoparticles could serve as potential anticancer agents through further research.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R357), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Abeer S. Aloufi was solely responsible for the entire work.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Soltys L, Olkhovyy O, Tatarchuk T, Naushad M. Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: Principles of green chemistry and raw materials. Magnetochemistry. 2021;7(11):145.10.3390/magnetochemistry7110145Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Kakar MU, Li J, Mehboob MZ, Sami R, Benajiba N, Ahmed A, et al. Purification, characterization, and determination of biological activities of water-soluble polysaccharides from Mahonia bealei. Sci Rep. 2022 May 17;12(1):8160. 10.1038/s41598-022-11661-3. PMID: 35581215, PMCID: PMC9114413.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Kumar D, Kumar A, Prakash O. Potential antifertility agents from plants: a comprehensive review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:1–32.10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Liu A, Liu S, Li Y, Tao M, Han H, Zhong Z, et al. Phosphoproteomics Reveals Regulation of Secondary Metabolites in Mahonia bealei Exposed to Ultraviolet-B Radiation. Front Plant Sci. 2022 Jan 11;12:794906. 10.3389/fpls.2021.794906. PMID: 35087555, PMCID: PMC8787227.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Vimala S. Kucing Galak. Malaysia: Institut Penyelidikan Perhutanan Malaysia; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Savithramma N, Sulochana C, Rao K. Ethnobotanical survey of plants used to treat asthma in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:54–61.10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Senthilkumar M, Gurumoorthi P, Janardhanan K. Some medicinal plants used by Irular, the tribal people of Marudhamalai hills, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. Nat Product Radiance. 2006;5:382–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Huang Y, Jiang Z, Wang J, Yin G, Jiang K, Tu J, et al. Quality evaluation of Mahonia bealei (Fort.) carr. using supercritical fluid chromatography with chemical pattern recognition. Molecules. 2019 Oct 13;24(20):3684. 10.3390/molecules24203684. PMID: 31614942; PMCID: PMC6832872.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Hu W, Zhou J, Shen T, Wang X. Target-guided isolation of three main antioxidants from Mahonia bealei (Fort.) carr. leaves using hsccc. Molecules. 2019 May 17;24(10):1907. 10.3390/molecules24101907. PMID: 31108973, PMCID: PMC6572348.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Steyn DG. The presence of hydrocyanic acid in stock feeds and other plants. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1938;9:60–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Lingaraju D, Sudarshana M, Rajashekar N. Ethnopharmacological survey of traditional medicinal plants in tribal areas of Kodagu district, Karnataka, India. J Pharm Res. 2013;6:284–97.10.1016/j.jopr.2013.02.012Suche in Google Scholar

[12] WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine. 2022. https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-global-centre-for-traditional-medicine.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Fakhri A, Behrouz S, Pourmand M. Synthesis, photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties of SnO2, SnS2 and SnO2/SnS2 nanostructure. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015 Aug;149:45–50. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.05.017. Epub 2015 May 27, PMID: 26046748 Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Li H, Li Q, Li Y, Sang X, Yuan H, Zheng B. Stannic oxide nanoparticle regulates proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, and oxidative stress of oral cancer cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:768. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00768.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Hsieh CL, Yu CC, Huang YL, Chung KF. Mahonia vs. berberis unloaded: generic delimitation and infrafamilial classification of berberidaceae based on plastid phylogenomics. Front Plant Sci. 2022 Jan 6;12:720171. 10.3389/fpls.2021.720171. PMID: 35069611; PMCID: PMC8770955.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Ahmed A, Naseem Siddique M, Alam U, Ali T, Tripathi P. Improved photocatalytic activity of Sr doped SnO2 nanoparticles: A role of oxygen vacancy. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;463:976–85.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Venkatesan R, Rajeswari N. Poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) bionanocomposites: effect of SnO2 NPs on mechanical, thermal, morphological, and antimicrobial activity. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2018;1(4):731–40.10.1007/s42114-018-0050-5Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Ahamed M, Akhtar MJ, Khan MM, Alhadlaq HA. SnO2-Doped ZnO/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: synthesis, characterization, and improved anticancer activity via oxidative stress pathway. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:89.10.2147/IJN.S285392Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Prasanth M, Muruganandam G, Ravichandran K, Dayana Jeyaleela G, Shanthaseelan K, Priyadharshini BP. Anticancer activity of tin oxide and cerium-doped tin oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Ipomoea carnea flower extract. Biomed Biotechnol Res J. 2022;6:337–40.10.4103/bbrj.bbrj_100_22Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Buniyamin I, Akhir RM, Nurfazianawatie MZ, Omar H, Malek NSA, Rostan NF, et al. Aquilaria malaccensis and Pandanus amaryllifolius mediated synthesis of tin oxide nanoparticles: The effect of the thermal calcination temperature. Mater Today Proc. 2023;75:23–30.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.09.580Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Elderdery AY, Alzahrani B, Alanazi F, Hamza SM, Elkhalifa AM, Alhamidi AH, et al. Amelioration of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells by ZnO-TiO2-Chitosan-Amygdalin nanocomposites. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(8):103999. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103999.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Sudha D, Vairam S, Sarathbabu S, Senthil Kumar N, Sivasamy R, Jone Kirubavathy S, et al. 2-Methylimidazolium pyridine-2,5-dicarboxylato zinc (II) dihydrate: Synthesis, characterization, DNA interaction, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant and anti-breast cancer studies. J Coord Chem 74(16):2701–19. 10.1080/00958972.2021.1981302.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Zhang Q, Kandasamy K, Alyami NM, Alyami HM, Natarajan N, Elayappan PK. Influence of Padina gymnospora on Apoptotic Proteins of Oral Cancer Cells – a Proteome-Wide Analysis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(12):5945–62. 10.1007/s12010-022-04045-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Mayandi J, Marikkannan M, Ragavendran V, Jayabal P. Hydrothermally synthesized Sb and Zn doped SnO2 nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;2:707–10.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Varshney B, Shoeb M, Siddiqui MJ, Azam A, Mobin M. Azadirachta indica (neem) leaves mediated synthesis of SnO2/NiO nanocomposite and assessment of its photocatalytic activity. In AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 1953. Issue 1. AIP Publishing LLC; 2018, May. p. 030140.10.1063/1.5032475Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Matussin SN, Tan AL, Harunsani MH, Mohammad A, Cho MH, Khan MM. Effect of Ni-doping on properties of the SnO2 synthesized using Tradescantia spathacea for photoantioxidant studies. Mater Chem Phys. 2020;252:123293.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.123293Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Bhavana S, Gubbiveeranna V, Kusuma CG, Ravikumar H, Sumachirayu CK, Nagabhushana H, et al. Facile green synthesis of SnO2 NPs using vitex altissima (L.) leaves extracts: characterization and evaluation of antibacterial and anticancer properties. J Clust Sci. 2019;30(2):431–7.10.1007/s10876-019-01496-wSuche in Google Scholar

[28] Teldja B, Noureddine B, Azzeddine B, Meriem T. Effect of indium doping on the UV photoluminescence emission, structural, electrical and optical properties of spin-coating deposited SnO2 thin films. Optik. 2020;209:164586.10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.164586Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Wang X, Wang X, Di Q, Zhao H, Liang B, Yang J. Mutual effects of fluorine dopant and oxygen vacancies on structural and luminescence characteristics of F doped SnO2 nanoparticles. Materials. 2017;10(12):1398.10.3390/ma10121398Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Ahmed A, Siddique MN, Alam U, Ali T, Tripathi P. Improved photocatalytic activity of Sr doped SnO2 nanoparticles: a role of oxygen vacancy. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;463:976–85.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.182Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Mostafa AM, Mwafy EA. Effect of dual-beam laser radiation for synthetic SnO2/Au nanoalloy for antibacterial activity. J Mol Structure. 2020;1222:128913.10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128913Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Gowri S, Gandhi RR, Sundrarajan M. Green synthesis of tin oxide nanoparticles by Aloe vera: structural, optical and antibacterial properties. J Nanoelectron Optoelectron. 2013;8(3):240–9. 10.1166/jno.2013.1466.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Fu L, Zheng Y, Ren Q, Wang A, Deng B. Green biosynthesis of SnO2 nanoparticles by plectranthus amboinicus leaf extract their photocatalytic activity toward rhodamine B degradation. J Ovonic Res. 2015;11(1):21–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Rajiv Gandhi R, Gowri S, Suresh J, Selvam S, Sundrarajan M. Biosynthesis of tin oxide nanoparticles using corolla tube of nyctanthes arbor-tristis flower extract. J Biobased Mater Bioenergy. 2012;6(2):204–8.10.1166/jbmb.2012.1210Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Khan SA, Kanwal S, Rizwan K, Shahid S. Enhanced antimicrobial, antioxidant, in vivo antitumor and in vitro anticancer effects against breast cancer cell line by green synthesized un-doped SnO2 and Co-doped SnO2 nanoparticles from Clerodendrum inerme. Microb Pathog. 2018;125:366–84. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.09.041.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Fatimah I, Purwiandono G, Hidayat H, Sagadevan S, Mohd Ghazali SA, Oh WC, et al. Flower-like SnO2 nanoparticle biofabrication using Pometia pinnata leaf extract and study on its photocatalytic and antibacterial activities. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Nov 10;11(11):3012. 10.3390/nano11113012. PMID: 34835776, PMCID: PMC8623890.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Bhawna, Choudhary AK, Gupta A, Kumar S, Kumar P, Singh RK, et al. Synthesis, antimicrobial activity, and photocatalytic performance of Ce doped SnO2 nanoparticles. Front Nanotechnol. 2020 Nov 19;2:595352.10.3389/fnano.2020.595352Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Roopan SM, Kumar SHS, Madhumitha G, Suthindhiran K. Biogenic-production of SnO2 nanoparticles and its cytotoxic effect against hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2). Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;175(3):1567–75. 10.1007/s12010-014-1381-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Tammina SK, Mandal BK, Ranjan S, Dasgupta N. Cytotoxicity study of Piper nigrum seed mediated synthesized SnO2 nanoparticles towards colorectal (HCT116) and lung cancer (A549) cell lines. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2017;166:158–68. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.11.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Dobrucka R, Dlugaszewska J, Kaczmarek M. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial effect of biosynthesized SnO2 nanoparticles using Pruni spinosae flos extract. Inorg Nano-Metal Chem. 2018;48(7):367–76. 10.1080/24701556.2019.1569054.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Khan SA, Kanwal S, Rizwan K, Shahid S. Enhanced antimicrobial, antioxidant, in vivo antitumor and in vitro anticancer effects against breast cancer cell line by green synthesized un-doped SnO2 and Co-doped SnO2 nanoparticles from Clerodendrum inerme. Microb Pathog. 2018;125:366–84. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.09.041.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Reeves A, Vinogradov SV, Morrissey P, Chernin M, Ahmed MM. Curcumin-encapsulating nanogels as an effective anticancer formulation for intracellular uptake. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2015;7(3):25.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Chuah LH, Roberts CJ, Billa N, Abdullah S, Rosli R. Cellular uptake and anticancer effects of mucoadhesive curcumin containing chitosan nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;116:228–36.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.01.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”