Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

-

Ayesha Talib

, Muhammad Zaeem Ahsan

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most challenging diseases among all the other diseases in the recent era, and it is a life-threatening disorder. The best enzymes to target for treating DM are α-glucosidase and α-amylase. For this purpose, we explored numerous succinimides with ketone functionalities. First, we explored these compounds for their in vitro analysis. Compounds 1 and 4 exhibited excellent inhibition of both enzymes in in vitro studies. These compounds displayed excellent activity with IC50 values of 3.69 and 1.526 µg·mL−1 against the α-glucosidase enzyme. In the α-amylase inhibitory assay, compound 1 has shown excellent potential with an IC50 value of 1.07 µg·mL−1 and compound 4 with an IC50 value of 0.115 µg·mL−1. Based on the in vitro analysis, the potent compounds were further subjected to their in vivo analysis. Before the in vivo analysis, the toxicity profile was checked, and it was confirmed that the compounds were safe at 1,500 µg·kg−1. Then, these compounds were subjected for their in vivo anti-diabetic potential in a mouse model of diabetes. Various concentrations of compounds 1 and 4 were explored by in vivo analysis using glibenclamide as a standard drug. The blood glucose level of the tested and control groups was measured at 0 to 15 days accordingly. Similarly, we also explored compounds 1 and 4 for the oral glucose tolerance test at 0–120 min using glibenclamide as the standard drug. Hence, the succinimide having ketone moiety displayed excellent potential against diabetes.

1 Introduction

A higher blood glucose level is the primary symptom of the heterogeneous collection of disorders known as diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. The number of diabetic patients sharply amplified globally from 108 million in 1980 to around four times in 2014 [2]. The estimation of the global pervasiveness of diabetes in percentage showed awestruck results. There was a clear increment in diabetes from 4.7% in 1980 to 8.5% in 2014, with prevalence increasing or, at best, remaining stable in all countries over this period [3]. In 2017, the number of diabetic patients was 451 million. In 2045, the number may have increase up to 693 million. The main problem is that half of the total population, 49.7, suffering from diabetes is not diagnosed properly. Moreover, the number of people with impaired glucose tolerance test was estimated to be 374 million, and nearly 21.3 million live births to women were predicted to have been affected by some form of hyperglycemia in pregnancy [4]. Currently, Pakistan is at the top of this index in diabetes.

DM is a condition of defective protein, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism that causes low insulin production or resistance to insulin action, which results in persistent hyperglycemia [5]. DM has two main types, namely, type 1 and 2. Type 2 DM is the most typical form of the disease. This type of diabetes is more common in adults. It accounts for 90% of all diabetes cases. Complications of DM are vast and the main cause of mortality and morbidity [6]. Chronic diabetes causes the failure of many vital organs, including the heart, kidneys, nerves, and eyes. The symptoms of DM are loss of vision, excessive hunger, excessive thirst, increased urination, and polyphagia [7]. Occasionally, hyperglycemic patients are accompanied by certain growth-impairing abnormalities and infections. If diabetes becomes uncontrolled, it will cause hypoglycemia, including non-ketotic hyperglycemia and occasionally ketoacidosis. Other complications of DM are retinopathy resulting from vision loss, nephropathy that leads to kidney failures, sexual dysfunction, and peripheral neuropathy resulting in foot ulcers, heart diseases, genitourinary, and vascular complications [8]. Furthermore, increased blood pressure and changes in lipoprotein metabolism are the two most prevalent illnesses in people with DM. To lower postprandial hyperglycemia, the therapeutic option for non-insulin-dependent DM is to decrease the absorption of sugar from the intestinal tract. This is typically accomplished by suppressing important enzymes involved in the metabolism of simple monosaccharides’ carbohydrates. The most important enzyme in this process, glucosidase, is found in a wide variety of plants, animals, and microorganisms [9].

A membrane-bound gut enzyme called glucosidase plays a major role in the breakdown of complex sugars and the release of glycol from their non-reducing side, which facilitates sugar absorption. Amylase is primarily responsible for glycol metabolism and spreads widely in plants, microorganisms, and animals. Breaking the bonds of 1,4-glucan, the main enzyme linked with type 2 DM can catalyze the breakdown of starch and other carbohydrate polymers, leading to postprandial hyperglycemia in T2DM patients [10]. Currently, oral hypoglycemic agents and insulin are used in the treatment of diabetes. These agents include biguanide, pioglitazone, glibornuride, bromocriptine, glitazone, bezafibrate, glipizide, pioglitazone, rosiglitazone, saroglitazar, and metformin. Due to various adverse effects of the aforementioned drugs such as skin, gastrointestinal problems, hematological, hypoglycemic coma, and kidney and liver dysfunction [11], the side effect-free treatment of diabetes is still a challenge for the medical system. Additional research for the treatment of diabetes is now being done. In this study, we explored succinimide derivatives for their in vitro and in vivo anti-diabetic potentials based on the previous literature survey [12–18]. The current study’s objective was to look into the synthetic compounds’ in vitro anti-diabetic potential. Animal models have also been used to examine these substances.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Chemicals

The chemicals listed in Table 1 were used in the current investigation.

List of chemicals and reagents

| Sr.# | Chemicals | CAS No. |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Phenyl maleimide | (941-69-5) |

| 2. | l-Isoleucine | (73-32-5) |

| 3. | Potassium hydroxide | (1310-58-3) |

| 4. | Creatinine | (60-27-5) |

| 5. | 8-Hydroxyquinoline | (148-24-3) |

| 6. | TLC silica gel 60 F254 | (105554) |

| 7. | Silica gel powder | (7631-86-9) |

| 8. | N-hexane | (110-54-3) |

| 9. | Methanol | (67-56-1) |

| 10. | Ethyl acetate | (141-78-6) |

| 11. | Chloroform | (67-66-3) |

| 12. | Hydrochloric acid | (7647-01-0) |

| 13. | Dimethyl-sulfoxide | (67-68-5) |

| 14. | Alcohol | (64-17-5) |

| 16. | α-Glucosidase | 9001-42-7 |

| 17. | α-Amylase | 9000-90-2 |

| 18. | Acarbose | 56180-94-0 |

| 19. | Aloxane | ALX2244-11-3 |

| 20. | Glibenclamide | Donated by Sanofi Aventis Pharma (Pvt.) Ltd, Pakistan |

2.2 Synthesis

In this research, ketone was added to maleimide in the presence of potassium hydroxide and creatinine in an appropriate container, and the reaction was started until the reaction was completed. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was used to keep track of the reaction’s progress. After completion of reaction workup was done with the help of distilled water. A separating funnel was used to separate the aqueous layer from the organic layer. Two layers were formed, and the aqueous layer was removed and discarded. Following separation, the organic layer was added to a rotary evaporator to dry the organic layer while operating at a low vacuum. The unpurified reaction mixture was then adsorbed on silica gel and loaded into a column for multipolar solvent purification [19].

2.3 Characterization

Structural details were elucidated using 1H NMR and 13C NMR.

2.4 In vitro anti-diabetic assay

2.4.1 α-Glucosidase assay

Different quantities of the synthesized compounds (31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg·mL−1, respectively) were prepared according to the previously prescribed procedure [20]. In all, 1,200 µL of buffer solution and 200 µL of substrate solution glucopyranoside (15 mg/10 mL distilled water) were prepared and then added to this solution to the above concentrations to produce samples for in vitro glucosidase activity. The aforementioned mixture also contained 0.5 µg·mL−1 of the glucosidase enzyme in distilled water. The reaction mixture was then prepared and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. After allowing the mixture to settle for a few minutes, HCl was added to stop the reaction. A spectrophotometer was used to measure the color’s intensity at 540 nm, and the percentage inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

2.4.2 α-Amylase assay

According to the previously described methodology [21], the α-amylase activity was measured. Amylase solution of 250 µL and phosphate buffer solvent of 250 µL were added to the mixture of the compounds of different concentrations (31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg·mL−1). Then, starch solution of 250 µL was added to that combination after incubation for 20 min, and the reaction mixture that had been created was then held in a water bath at 100°C for some time. The microplate reader used 656 nm to gauge the color’s intensity. The % inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

2.5 In vivo anti-diabetic assay

2.5.1 Test animals

For the in vivo phase of this study, albino mice that were 3–4 weeks old and weighed 20–27 g were used. They were acquired from the National Institutes of Health in Islamabad, Pakistan, and kept in sterile containers in isolated lab facilities at a temperature of 25°C + 2°C, humidity of 50% + 5%, and a period of 12 h of light to 12 h of darkness. They were also fed a mouse nutrient tape and water mixture as directed.

2.5.2 Acute toxicity studies

To establish the toxicity tests of the newly synthesized chemicals, the test animals were divided into six groups of four animals (n = 5). The synthetic substances were given intraperitoneally (i.p.) at doses ranging from 100 to 1,500 mg·kg−1 body weight. The animals were critically observed for the first 24 h, then the observation time was exceeded to 72 h. Any aberrant reactions were observed 3 days after the drugs were given to the animals [22].

2.6 Diabetes induction and experiment design

According to the claimed method of producing DM, alloxan was employed. Animals that had been fasting for 16 h were given a single injection of freshly manufactured alloxan (ALX) intraperitoneally at a concentration of 150 mg·kg−1. Following the administration of ALX, the animals’ glucose levels were checked to keep an eye out for the onset of diabetes. Only animals with diabetes and incident blood glucose levels over 200 mg·dL−1 were chosen for the investigations. The hypoglycemic effects of the synthesized succinimide derivatives were studied in 30 animals. Six test animals were placed in each of the five groups (n = 5). Group II was labeled the control group and received only I/P with normal saline. During the induction of diabetes, Group III received a conventional medication (glibenclamide), while Group I served as the diabetic control group and simply received alloxan. Groups IV and V each received a unique dosage of the tested samples. The blood glucose level of each animal was noted on days 0, 4, 7, 10, and 15 of the experiment [23].

2.7 Biochemical assay

Blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital plexus of each animal under mild anesthesia for 15 days following pure given compounds for various biochemical alterations [24].

2.8 Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

The OGTT, which measures the ability to adequately respond to a glucose challenge, is performed 5 days before the experiment’s end on the 15th day. The OGTT was performed on overnight-fasted mice, comprising control and treatment mice. As an alternative to glibenclamide, glucose was given orally at a dose of 2 g·kg−1. To assess the effect of exogenously provided d-glucose on treated mice, the blood glucose level was measured at intervals of 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after the administration of glucose [25].

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals’ use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals. The Ethics Committee, Bacha Khan University Charsadda, Department of Pharmacy, approved the experimental protocol with ethical approval no. Phrm-22/05S.

3 Results

3.1 Procedure for the synthesis of succinimide derivatives

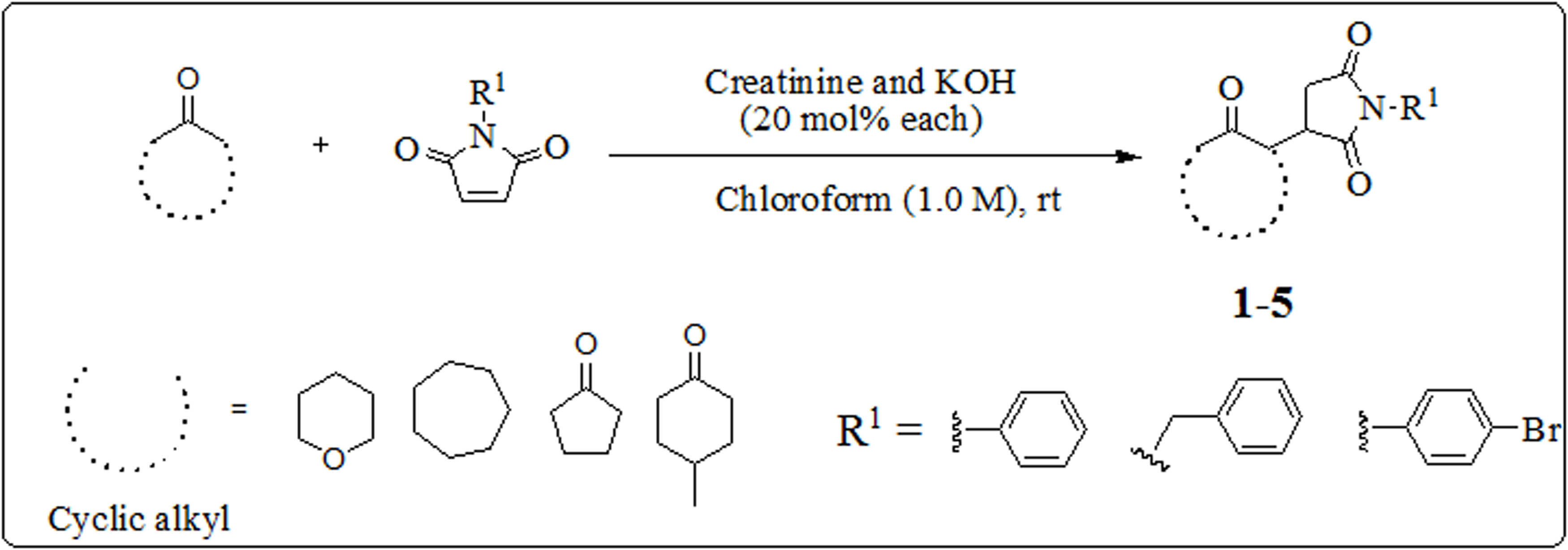

Various N-substituted maleimides (equiv. 1 mmole), creatinine, and 20 µmol% KOH were added to a well-mixed solution of ketones (equiv. 2 mmole) in chloroform at room temperature. When the reaction was finished, a sufficient amount of water was added to quench it (15 mL). A separatory funnel was used to isolate the chloroform component. Three separate separations of the organic layer were carried out (15 mL each). Following separation, the organic layer was dried using a rotary evaporator under a low vacuum. After being adsorbed onto silica gel, the reaction mixture was then put onto the purification column. N-hexane and ethyl acetate were used as solvents in the column chromatography. From the pure product, the yield of the end product was estimated in Scheme 1 and Figure 1.

Synthesis of succinimide derivatives (Compounds 1–5).

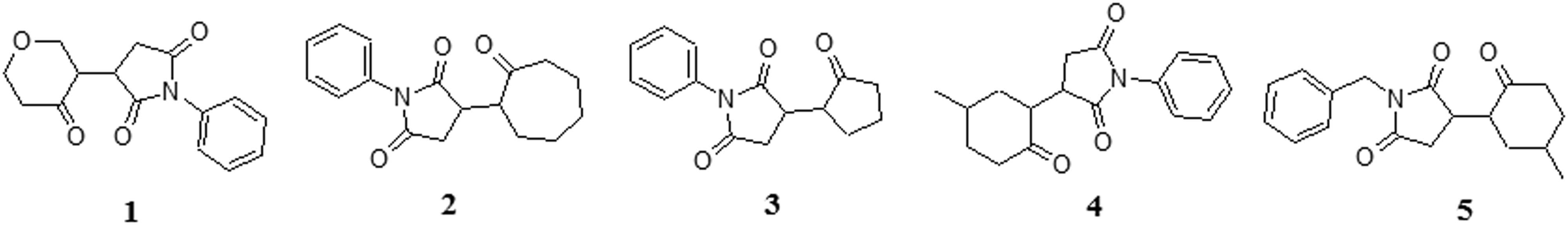

Structures of the synthesized compounds.

3.2 Characterization of the synthesized compounds

3.2.1 (4-Oxo-tetrahydro-pyran-3yl)-1-succinimide (compound 1)

This reaction was completed in 19 h, and the color of the obtained product is white with 74% yield. The R f value in methanol and chloroform (1:6) was calculated as 0.42. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) (ppm): 174.96, 129.89, 129.21, 128.73, 126.31, 70.22, 69.01, 66.62, 53.11, 51.23, 43.14, 41.68, 36.97, 32.30, 31.47. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (ppm): 7.25 to 7.48 (m; 5H), 4.26 to 4.75 (m; 2H), 3.52 to 3.78 (m; 2H), 2.71 to 3.19 (m; 5H), 2.33 to 2.41 (m; 1H); HPLC purity: 98.4%, TR: 6.3 min. LC-MS: C15H15NO4 (m/z): 274.1 [M + H]. Analysis calculated in percentage: N, 5.13; H, 5.53; C, 65.92; Found (%): N, 5.15; H, 5.52; C, 65.73 (Figures S1 and S2).

3.2.2 (2-Oxo-cyclo-heptyl)-1-succinimde (compound 2)

The reaction was finished in 18 h, and the color was white with 78–80% yield. The R f value in ethyl acetate and n-hexane (1:4) was measured as 0.52.

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) (ppm): 214.03, 213.86, 177.27, 175.12, 174.91, 134.61, 133.66, 130.15, 129.77, 128.21, 127.30, 127.06, 54.14, 53.19, 38.64, 34.11, 33.55, 33.39, 31.70, 31.06, 30.66, 30.51, 30.31, 28.94, 25.22. 1H NMR (400 MHz; CDCl3) (ppm): 7.45 to 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.37 to 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.32 to 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.24 to 7.27 (m, 1H), 3.42 to 3.55 (m, 1H), 3.22 to 3.38 (m, 1), 2.75 to 3.01 (m, 2H), 2.61 to 2.75 (m, 2H), 2.00 to 2.27 (m, 2H), 1.23 to 1.99 (m, 6H); HPLC purity: 97.1%, TR: 13.5 min. LC-MS for C17H19NO3 (m/z): 286.1 [M + H]. Analysis calculated in percentage: N, 4.91; H, 6.71; C, 71.56; Found (%): N, 4.88; H, 6.72; C, 71.70 (Figures S3 and S4).

3.2.3 (2-Oxocyclopentyl)-1phenylsuccinimide (compound 3)

This reaction was finished in 24 h, and the color was yellowish with 75% yield. The R f value in solvent ethyl acetate in n-hexane (1:2) was measured as 0.41. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) (ppm): 216.19, 179.82, 176.88, 132.78, 129.81, 128.92, 127.07, 51.08, 40.01, 37.96, 30.68, 25.59, 23.69; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (ppm): 7.44 to 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.36 to 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.23 to 7.27 (m, 2H), 3.45 (dd, J: 8.43, 5.26, & 3.17 Hz; 1H), 2.99 (dd, J: 9.66 & 18.39 Hz; 1H), 2.82 to 2.89 (m, 1H), 2.95 (dd, J: 5.26 & 18.39 Hz; 1H), 2.36 to 2.45 (m, 1H), 2.18 to 2.26 (m, 2H), 2.06 to 2.17 (m, 2H), 1.82 to 1.95 (m, 2H); HPLC purity: 97.3%, TR: 9.1 min. LC-MS for C15H15NO3 (m/z): 258.1 [M + H]. Analysis calculated in percentage: N, 5.44; H, 5.88; C, 70.02; Found (%): N, 5.47; C, 70.21; H, 5.86 (Figures S5 and S6).

3.2.4 3-(5-Methyl-2-oxocyclohexyl)-1-phenylsuccinimide (compound 4)

The synthesis of this compound was finished in 24 h. The color was white solid. The isolated yield was 78%. R f value was 0.47 in ethyl acetate and n-hexane (1: 4). 13C NMR (100 MHz; CDCl3) (ppm): 210.85, 210.45, 178.74, 178.64, 175.88, 175.83, 132.54, 132.25, 129.29, 128.74, 126.93, 126.78, 126.76, 51.30, 47.47, 46.15, 41.34, 41.22, 41.02, 38.18, 37.41, 37.18, 37.13, 35.72, 35.24, 34.92, 33.60, 33.37, 32.40, 32.00, 26.93, 26.88, 21.37, 21.35, 17.70, 17.67. 1H NMR (400 MHz; CDCl3) (ppm): 7.38 to 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.19 to 7.27 (m, 2H), 7.31 to 7.33 (m, 1), 3.03 to 3.15 (m, 1H), 2.94 to 2.97 (m, 1H), 2.43 to 2.81 (m, 2H), 2.16 to 2.36 (m, 2H), 1.87 to 2.03 (m, 2H), 1.61 to 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.26 to 1.44 (m, 1H), 1.14 to 1.20 (m, 3H), 0.95 to 0.96 (m, 1H); HPLC purity: 96.5%, TR: 11.2 min. LC-MS for C17H19NO3 (m/z): 286.5 [M + H]. Analysis calculated in percentage: N, 4.91; H, 6.69; C, 71.56; Found (%): N, 4.93; H, 6.71; C, 71.76 (Figures S7 and S8).

3.2.5 1-Benzyl-3(5-methyl-2-oxo-cyclohexyl)succinimide (compound 5)

This reaction was finished in 24 h. The color was yellowish with a total yield of 63%. The R f value was calculated as 0.45 in ethyl acetate in n-hexane (1:4). 13C NMR (100 MHz; CDCl3) (ppm): 212.54, 210.18, 179.43, 176.54, 176.42, 136.07, 128.83, 128.77, 128.69, 128.63, 128.05, 127.84, 100.07, 99.54, 50.56, 46.76, 45.52, 42.56, 41.38, 41.17, 41.04, 39.94, 37.42, 37.24, 35.22, 34.97, 32.92, 32.71, 32.32, 31.79, 26.95, 26.82, 21.30, 21.21, 17.83, 17.77. 1H NMR (400 MHz; CDCl3) (ppm): 7.23 to 7.39 (m, 5H), 4.62 to 4.73 (m, 2H), 2.63 to 3.08 (m, 1H), 2.24 to 2.36 (m, 3H), 1.83 to 2.02 (m, 4H), 1.32 to 1.45 (m, 2H), 1.16 to 1.26 (m, 1H), 1.00 (d; J: 6.58 Hz, 3H); HPLC purity: 95.7%, TR: 12.1 min. LC-MS for C18H21NO3 (m/z): 300.2 [M + H]. Analysis calculated in percentage: N, 4.68; H, 7.07; C, 72.22; Found (%): N, 4.71, H, 7.09, C, 72.01 (Figures S9 and S10).

3.3 α-Glucosidase inhibitory result

In the α-glucosidase inhibition test, compound 1 at concentrations of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed a percent inhibition of 84.62 ± 0.56, 79.35 ± 0.22, 74 36 ± 0.81, 71.62 ± 0.21, and 56.16 ± 0.18 with an IC50 of 3.69 µg·mL−1. Compound 2 performed similarly at doses of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed a percent inhibition of 80.30 ± 0.70, 75.70 ± 0.80, 61.91 ± 0.88, 47.80 ± 0.90, and 43.00 ± 0.60, respectively, with an IC50 of 45.19 µg·mL−1. Similarly, compound 3 displayed a percentage inhibition of 71.36 ± 0.57, 66.85 ± 2.24, 61.08 ± 0.47, 56.90 ± 0.96, and 46.35 ± 0.51, respectively, and an estimated IC50 of 22.45 µg·mL−1. In this assay, compound 4 showed a percent inhibition of 91.90 ± 0.96, 85.08 ± 0.47, 77.40 ± 0.20, 71.61 ± 0.43, and 65.45 ± 0.90, respectively, and an IC50 of 1.526 µg · mL−1. Compound 5 at doses of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed a percentage inhibition of 78.91 ± 1.30, 65.00 ± 0.30, 58 .76 ± 0.58, 52.67 ± 0.61, and 43.74 ± 0.61, respectively, and an IC50 of 39.89 µg·mL−1. The standard drug acarbose was used in this assay, which had a percent inhibition of 93.56 ± 1.06, 90.31 ± 0.88, 87.56 ± 1.21, 85.44 ± 0.22, and 83.30 ± 1.20, respectively, at the same concentration as IC50 of 0.50 µg·mL−1, as shown in Table 2. Compound 1 and compound 4 were the most active compared to the others in this assay (Table 2).

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of the synthesized compounds

| Compound | Conc. (µg·mL−1) | Percent inhibitions (±SEM) | IC50 (μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 500 | 84.62 ± 0.56*** | 3.69 |

| 250 | 79.35 ± 0.22*** | ||

| 125 | 74.36 ± 0.81*** | ||

| 62.50 | 71.62 ± 0.21*** | ||

| 31.25 | 56.16 ± 0.18*** | ||

| 2 | 500 | 80.30 ± 0.70*** | 45.19 |

| 250 | 75.70 ± 0.80*** | ||

| 125 | 61.91 ± 0.88*** | ||

| 62.50 | 47.80 ± 0.90*** | ||

| 31.25 | 43.00 ± 0.60** | ||

| 3 | 500 | 71.36 ± 0.57*** | 22.45 |

| 250 | 66.85 ± 2.24*** | ||

| 125 | 61.08 ± 0.47*** | ||

| 62.50 | 56.90 ± 0.96*** | ||

| 31.25 | 46.35 ± 0.51*** | ||

| 4 | 500 | 91.90 ± 0.96 ns | 1.526 |

| 250 | 85.08 ± 0.47* | ||

| 125 | 77.40 ± 0.20** | ||

| 62.50 | 71.61 ± 0.43*** | ||

| 31.25 | 65.45 ± 0.90*** | ||

| 5 | 500 | 78.91 ± 1.30*** | 39.89 |

| 250 | 65.00 ± 0.30*** | ||

| 125 | 58.76 ± 0.58*** | ||

| 62.50 | 52.67 ± 0.61*** | ||

| 31.25 | 43.74 ± 0.61*** | ||

| Acarbose (Std) | 500 | 93.56 ± 1.06 | 0.50 |

| 250 | 90.31 ± 0.88 | ||

| 125 | 87.56 ± 1.21 | ||

| 62.50 | 85.44 ± 0.22 | ||

| 31.25 | 83.30 ± 1.20 |

All values are taken as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test was followed. Values significantly differ from the standard drug, i.e.,* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001, and ns = not significant.

3.4 α-Amylase inhibitory assay

In the amylase inhibitory test, compound 1 at concentrations of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed a percentage inhibition of 88.90 ± 1.16, 82.27 ± 0.58, 79.36 ± 0.57, 71.34 ± 0.98, and 67.70 ± 1.25, respectively, with an IC50 of 1.07 µg·mL−1. Similarly, compound 2 showed percent inhibition of 85.62 ± 0.56, 74.35 ± 0.21, 71.36 ± 0.82, 65.62 ± 0.27, and 51.16 ± 0.18, respectively, with an IC50 11.16 of µg·mL−1. Likewise, compound 3 with doses of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed percent inhibition of 80.90 ± 0.00, 73.08 ± 46, 67.40 ± 0.22, 62.61 ± 0.42, and 53.45 ± 0.92 with an IC50 of 7.17 µg·mL−1. Compound 4 showed a percentage inhibition of 95.45 ± 0.49, 91.75 ± 0.58, 87.79 ± 0.62, 83.61 ± 0.53, and 78.75 ± 0.63 and an IC50 of 0.115 µg·mL−1. In compound 5, with doses of 500, 250, 125, 62.50, and 31.25 µg·mL−1 showed a percent inhibition of 87.90 ± 0.92, 83.08 ± 0.45, 80.40 ± 0.22, 75.61 ± 0.45, and 71.45 ± 0.92, each with an IC50 of 15.43 µg·mL−1. In the amylase inhibition test, the standard drug acarbose showed a percentage inhibition of 95.66 ± 0.88, 92.32 ± 0.52, 89.50 ± 0.44, 87.27 ± 0.57, and 86.44 ± 0.58, respectively, with an IC50 of 0.090 µg·mL−1. In this assay, compounds 1 and 4 again are the most active compounds, and the second most active compound is fourth compared to others (Table 3).

α-Amylase inhibition activity of the synthesized compounds

| Compound | Conc. (μg·mL−1) | Percent inhibitions (± SEM) | IC50 (μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 500 | 88.90 ± 1.16** | 1.07 |

| 250 | 82.27 ± 0.58*** | ||

| 125 | 79.36 ± 0.57* | ||

| 62.50 | 71.34 ± 0.98* | ||

| 31.25 | 67.70 ± 1.25* | ||

| 2 | 500 | 85.62 ± 0.56*** | 11.16 |

| 250 | 74.35 ± 0.21*** | ||

| 125 | 71.36 ± 0.82*** | ||

| 62.50 | 65.62 ± 0.27*** | ||

| 31.25 | 51.16 ± 0.18*** | ||

| 3 | 500 | 80.90 ± 0.00* | 7.17 |

| 250 | 73.08 ± 0.46** | ||

| 125 | 67.40 ± 0.22** | ||

| 62.50 | 62.61 ± 0.42** | ||

| 31.25 | 53.45 ± 0.92** | ||

| 4 | 500 | 95.45 ± 0.49ns | 0.115 |

| 250 | 91.75 ± 0.58ns | ||

| 125 | 87.79 ± 0.62ns | ||

| 62.50 | 83.61 ± 0.53ns | ||

| 31.25 | 78.75 ± 0.63** | ||

| 5 | 500 | 77.90 ± 0.92*** | 10.79 |

| 250 | 73.08 ± 0.45*** | ||

| 125 | 60.40 ± 0.22*** | ||

| 62.50 | 55.61 ± 0.45*** | ||

| 31.25 | 51.45 ± 0.92*** | ||

| Acarbose | 500 | 95.66 ± 0.88 | 0.090 |

| 250 | 92.32 ± 0.52 | ||

| 125 | 89.50 ± 0.44 | ||

| 62.50 | 87.27 ± 0.57 | ||

| 31.25 | 86.44 ± 0.58 |

All values are taken as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test were followed. Values were significantly different compared to the standard drug, i.e., * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and ns = not significant.

3.5 Acute toxicity results

Based on the acute toxicity series findings of lethal dosage (LD0 to LD100), the dose range of Compounds 1 and 4 employed for acute toxicity was 100–1,500 mg·kg−1 body weight. The entire dosing schedule for synthetic compounds is shown in Table 4. Each animal was individually and often observed during the first 24 h of the acute toxicity research test for behavioral abnormalities and general toxicity alterations. After that, 3 days of daily observations were done. In this toxicological study, the newly synthesized chemicals were tested for harmful or toxic effects, but no anomalous effects were discovered. The medicine was proven to be safe, up to 1,500 mg. The compounds’ LD50 in mice was roughly 1,500 mg·kg−1. In mice given 1,000 mg·kg−1 of body weight of 1 and 4 synthesized compounds, no abnormalities were seen in the nasal or ocular system, respiration, coat and skin, sweat, urinary incontinence, defecation incontinence, salivation, hair loss, blood pressure and heart rate, or CNS abnormalities like gait, drowsiness, ptosis, and convulsions (Table 4).

Acute-toxicity studies with tested synthesized compounds

| Groups | Animals | Tested compounds 1 and 4 (mg·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 100 |

| 2 | 5 | 200 |

| 3 | 5 | 400 |

| 4 | 5 | 500 |

| 5 | 5 | 1,000 |

| 6 | 5 | 1,500 |

n = 5 per group.

3.6 In vivo anti-diabetic study results

Based on their potential in vitro anti-diabetic study results, we evaluated two synthetic drugs for anti-diabetic efficacy in this assay. The experiment was conducted using the common medication glibenclamide. Compound 1 demonstrated a reduction in blood glucose levels over 15 days to 120, 201, 48, 34, and 36 mg·dL−1 at strengths of 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 µg·kg−1, respectively, while compound 4 demonstrated a reduction in blood glucose levels of 202, 109, 69, 64, and 37 mg·dL−1 at doses of 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 µg·kg−1, respectively, compared to the most active glibenclamide, both compounds 1and 4 were able to significantly reduce blood glucose levels (Table 5).

In vivo results of synthesized compounds against the standard drug

| Sr.# | Dose (µg·kg−1) | Blood glucose level (mg·dL−1) | Decrease in blood glucose after 15 days (mg·dL−1) | Change in body weight (g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | 0 day | 4th day | 7th day | 10th day | 15th day | |||||

| 1 | Diabetic control | 0.35 mL | 476 | 481 | 501 | 512 | 524 | −48 | −13.4 | |

| 2 | Normal control saline | — | 123*** | 109*** | 101*** | 94*** | 92*** | 31 | — | |

| 3 | Glibenclamide | 1 | 500 | 473*** | 303*** | 257*** | 212*** | 198*** | 275 | +10.3 |

| 2 | 250 | 431*** | 342*** | 310*** | 270*** | 201*** | 230 | +8.1 | ||

| 3 | 125 | 446*** | 405*** | 380*** | 361*** | 334*** | 112 | +6.3 | ||

| 4 | 62.5 | 381*** | 348*** | 304*** | 230*** | 285*** | 96 | +5.7 | ||

| 5 | 31.25 | 406*** | 381*** | 345*** | 328*** | 317*** | 89 | +2.9 | ||

| 4 | Compound 1 | 1 | 500 | 410*** | 386*** | 373*** | 315*** | 290*** | 120 | +7.3 |

| 2 | 250 | 418*** | 396*** | 347*** | 215*** | 217*** | 201 | +5.5 | ||

| 3 | 125 | 443* | 435* | 416* | 401* | 395* | 48 | +4.1 | ||

| 4 | 62.5 | 380*** | 371*** | 365*** | 351*** | 346*** | 34 | +4.4 | ||

| 5 | 31.25 | 414** | 406** | 397** | 380** | 378** | 36 | +2.3 | ||

| 5 | Compound 4 | 1 | 500 | 459*** | 403*** | 360*** | 302*** | 257*** | 202 | +7.1 |

| 2 | 250 | 465ns | 467ns | 445ns | 407ns | 356ns | 109 | +3.5 | ||

| 3 | 125 | 438* | 432* | 420* | 394* | 369* | 69 | −3.3 | ||

| 4 | 62.5 | 389*** | 357*** | 349*** | 336*** | 325*** | 64 | −4.2 | ||

| 5 | 31.25 | 454 ns | 446 ns | 432 ns | 423 ns | 417 ns | 37 | −6.2 | ||

Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test, *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05, ns = not significant (P > 0.05). All the data were compared to the diabetic control group.

3.7 Biochemical assays

In this research, the values of serum glutamate oxaloacetate (SGOT), serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (SGPT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were assessed in alloxan-triggered diabetic mice. Table 6 represents the effect of tested compounds on the liver enzymes. It was found that with the administration of compounds 1 and 4 there was no significant rise in the level of SGPT, ALP, and SGOT that was checked against the glibenclamide as standard. Moreover, the tested compounds were also evaluated for serum creatinine changes. Compounds 1 and 4 showed no rise in serum creatinine above the normal range.

Biochemical tests results

| Treatment | Route | Biochemical changes after 15 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGOT (IU) | SGPT (IU) | ALP (IU) | Serum creatinine (mg·dL−1) | ||

| Group I diabetic control | IP | 19.1 ± 0.37 | 14.1 ± 0.32 | 184.1 ± 0.33 | 0.60 ± 0.27 |

| Group II normal control | IP | 45.1 ± 0.55### | 53.1 ± 0.57### | 290.7 ± 0.69### | 2.7 ± 0.36# |

| Group III GB | IP | 19.26 ± 0.61*** | 17.8 ± 0.26*** | 178.4 ± 0.78*** | 0.53 ± 0.47ns |

| Group IV Compound 1 | IP | 22.6 ± 0.63*** | 32.5 ± 0.95*** | 180.3 ± 0.89*** | 0.77 ± 0.67ns |

| Group V Compound 4 | IP | 26.7 ± 0.85*** | 38.3 ± 0.9*** | 183.3 ± 0.73*** | 0.80 ± 0.42ns |

Two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post-test. Group I compared with Group II. After that group II compared with group (III–VII). Data are represented as changes in LFTs and serum creatinine (mean ± SEM of n = 3). *** P < 0.001. ### P < 0.001, # P < 0.05 which means the comparison of normal control to the diabetic control. ns; not significant.

3.8 OGTT results

Overnight fasting animals were used for the OGTT, comprising control and treatment mice. Glucose was given orally at a dose of 2 g·kg−1 instead of the usual medication, glibenclamide. To assess the impact of exogenously delivered D-glucose on treated mice, blood glucose levels were measured at intervals of 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after administering glucose. After 120 min of glucose administration, mice treated with compound 1 demonstrated excellent results of 158.2 mg·dL−1, followed by compound 4 (152.8 mg·dL−1), in comparison to the usual glibenclamide (138.4 mg·dL−1) (Table 7).

OGTT results

| Treatment | OGTT (mg·dL−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | |

| Group-I (Tween 80) | 210.5 | 228.3 | 253.7 | 296.9 |

| Group II (GB) | 151.1*** | 173.7*** | 215.4*** | 138.4*** |

| Compound 1 | 163.4*** | 195.8*** | 212.2*** | 158.2*** |

| Compound 4 | 161.3*** | 186.2*** | 211.4*** | 152.8*** |

Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test, *** P < 0.001. All the data were compared to the tween-80 group.

4 Discussion

The in vitro anti-diabetic activity of the synthesized compounds was investigated. First, all α-amylase inhibitory properties were assessed. This α-amylase enzyme, which is present in saliva and pancreatic juice, is responsible for breaking down large polysaccharides into smaller ones. However, the small intestine may contain α-glucosidase, which converts disaccharides into monosaccharides. The α-glucosidase and α-amylase slow down the absorption of carbohydrates at the intestinal level and increase postprandial blood sugar levels. The succinimide moiety of synthetic heterocyclic compounds has been used to inhibit carbohydrate metabolic enzymes. The succinimide derivatives support an inhibitory effect on the enzyme, resulting in a decrease in blood glucose levels. The result of the experimental work showed that succinimide derivatives are useful in treating postprandial hyperglycemia. The α-amylase inhibitory activity of compound 1 at the highest concentration showed excellent potential, with an IC50 value of 1.07 µg·mL−1, and compound 4 showed 0.115 µg·mL−1. Similarly, in the α-glucosidase assay, compound 1 demonstrated excellent percent inhibition, as shown in Table 1 and 2. Before the in vivo evaluation, the toxicity profile of the synthesized compounds was also verified for consistency with the safety profile of the compounds, and it was concluded that our synthesized compounds were safe up to 1,500 mg·kg−1. In the OGTT, compounds 1 and 4 showed a significant decline in blood glucose levels from 30 min to group 1’s. The ability of the samples being investigated to lower postprandial glucose levels can be ascribed to several factors, including decreased glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, increased peripheral glucose utilization, and restricted glucose uptake. This shows that the tested samples have the potential to improve regulatory processes, implying that the compounds may be useful in reducing complications of diabetes associated with hyperglycemia [26].

Body weight is a sensitive indicator of an experimental animal’s health, and a decline in body weight is correlated with metabolic abnormalities caused by poisoning [27]. One of the potential causes of weight loss is a diabetic condition caused by specific harmful chemicals. In diabetic animals, a lack of insulin inhibits the body from delivering blood glucose to the cells for energy, causing the cells to start burning fat and muscle instead, lowering body weight. In most previous investigations, body weights of diabetic animals compared to their control peers were mainly studied in adults and especially male animals, although only a few cases included animals of both sexes. In the present study, however, the body weights of alloxan-induced diabetic young, adult, and old mice of both sexes were estimated and compared to the control animals of the same sex and age group. Loss of body weight in diabetic animals such as rabbits, dogs, mice, or rats compared to the control animal has been reported by several previous investigators. Several experimental studies have shown that administration of alloxan or streptozotocin after their intracellular accumulation selectively causes the destruction of the pancreatic cell membrane and cytotoxicity, leading to a reduction in pancreatic islets, depletion of cells, and an overall reduction in the number of cells; this can lead to insufficient insulin secretion. With a lack of insulin in the blood, sugar cannot enter the cell, which leads to a hyperglycemic state. In such conditions, the body attempts to eliminate extra sugar by excreting it through the urine. A decrease in body water due to frequent urination may result in a reduction in body weight. However, weight loss may also be caused by an excessive breakdown of muscle proteins, which can be used as a substitute for the energy that would otherwise be provided by glucose since insulin is not present in the blood and the glucose entry into the cell is largely unsuccessful. The body weight loss in mice with alloxan diabetes seen in the current investigation lends support to the aforementioned concept. The animals’ pancreatic islets of Langerhans are destroyed by the beta-cytotoxin agent alloxan. This results in a decrease in insulin production, which raises blood sugar levels. When the mice were given continuous treatment with the produced compounds 1 and 4, there was a striking decrease in BGL. For experiments, a dosage of 500–31.25 µg·kg−1 was employed. The reduction in BGL was observed from 120 to 36 mg·dL−1 and from 202 to 37 mg·dL−1 by compounds 1 and 4, respectively. At a dose of 500–31.25 µg·kg−1 each, reduction in BGL plays a significant role in reducing BGL in alloxan-induced hyperglycemia in animals when compared with standard drug glibenclamide. Synthesized ketone derivatives’ pharmacological actions have demonstrated that they can fulfill the criteria for being approved as medicines. Additionally, the SAR analyses of these variants can be used to improve them.

5 Conclusion

In this research work, we synthesized various ketone derivatives and investigated their anti-diabetic potential. Among these five compounds, only compounds 1 and 4 had an anti-hyperglycemic activity in in vitro activities. Acute in vivo toxicity research did not reveal any unique symptoms. During the in vivo assay, both compounds 1 and 4 displayed a very excellent effect on diabetic mice compared to the reference drug glibenclamide. Based on the aforementioned findings, we are working on designing further studies like SAR and mechanistic studies in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Princess Nourah bint Abdularahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R47), Princess Nourah bint Abdularahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R47), Princess Nourah bint Abdularahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization – A.T., S.A.S., M.S.J., M.Z.A., A.M.; methodology – I.A.B., H.S., validation T.S.A., formal analysis – N.A., investigation – A.R., A.T., and resources and data curation and original draft preparation – A.R., A.T. All authors have read and agree to submit this version of manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: One of the corresponding authors (Abdur Rauf) is a member of the Editorial Board of Green Processing and Synthesis.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Rosik J, Szostak B, Machaj F, Pawlik A. The role of genetics and epigenetics in the pathogenesis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Ann Hum Genet. 2020;84(2):114–24.10.1111/ahg.12356Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J hepatology. 2019;70(1):151–71.10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Franzke B, Schwingshackl L, Wagner KH. Chromosomal damage measured by the cytokinesis block micronucleus cytome assay in diabetes and obesity-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mutat Res/Reviews Mutat Res. 2020;786:108343.10.1016/j.mrrev.2020.108343Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Shah S, Sharma SK, Sinha B, Kalra S, Sahay RK, Gangopadhyay KK, et al. History and Milestones in Development of Insulins. Norm Physiol Metab Insulin Ther Made Easy. 2020;1:1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Poznyak A, Grechko AV, Poggio P, Myasoedova VA, Alfieri V, Orekhov AN. The diabetes mellitus–atherosclerosis connection: The role of lipid and glucose metabolism and chronic inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1835.10.3390/ijms21051835Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Giulietti A, van Etten E, Overbergh L, Stoffels K, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile. 1-25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(1):47–57.10.1016/j.diabres.2006.10.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Ranheim T, Halvorsen B. Coffee consumption and human health–beneficial or detrimental? –Mechanisms for effects of coffee consumption on different risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Nutr & food Res. 2005;49(3):274–84.10.1002/mnfr.200400109Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Wang W, Tang X, Feng H, Sun F, Liu L, Rajah GB, et al. Clinical manifestation of non-ketotic hyperglycemia chorea: a case report and literature review. Medicine. 2020;99(22):e19801.10.1097/MD.0000000000019801Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Kimura A, Lee JH, Lee IS, Lee HS, Park KH, Chiba S, et al. Two potent competitive inhibitors discriminating α-glucosidase family I from family II. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339(6):1035–40.10.1016/j.carres.2003.10.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Liu D, Gao H, Tang W, Nie S. Plant non‐starch polysaccharides that inhibit key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1401(1):28–36.10.1111/nyas.13430Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Kimura I. Medical benefits of using natural compounds and their derivatives having multiple pharmacological actions. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126(3):133–43.10.1248/yakushi.126.133Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Alshehri OM, Mahnashi MH, Sadiq A, Zafar R, Jan MS, Ullah F, et al. Succinimide derivatives as antioxidant anticholinesterases, anti-α-amylase, and anti-α-glucosidase: in vitro and in silico approaches. Evidence-Based Complementary Alternative Med. 2022;2022:6726438. 10.1155/2022/6726438.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Waheed B, Mukarram Shah SM, Hussain F, Khan MI, Zeb A, Jan MS. Synthesis, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activities of ketone derivatives of succinimide. Evidence-Based Complementary Alternative Med. 2022;2022:1445604. 10.1155/2022/1445604.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Sadiq A, Nugent TC. Catalytic access to succinimide products containing stereogenic quaternary carbons. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5(38):11934–38.10.1002/slct.202003664Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Huneif MA, Mahnashi MH, Jan MS, Shah M, Almedhesh SA, Alqahtani SM, et al. New succinimide–thiazolidinedione hybrids as multitarget antidiabetic agents: design, synthesis, bioevaluation, and molecular modelling studies. Molecules. 2023;28(3):1207.10.3390/molecules28031207Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Mahnashi MH, Alam W, Huneif MA, Abdulwahab A, Alzahrani MJ, Alshaibari KS, et al. Exploration of succinimide derivative as a multi-target, anti-diabetic agent: in vitro and in vivo approaches. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1589.10.3390/molecules28041589Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Pervaiz A, Jan MS, Hassan Shah SM, Khan A, Zafar R, Ansari B, et al. Comparative in-vitro anti-inflammatory, anticholinesterase and antidiabetic evaluation: Computational and kinetic assessment of succinimides cyano-acetate derivatives. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40:1–14.10.1080/07391102.2022.2069862Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Ahmad A, Ullah F, Sadiq A, Ayaz M, Saeed Jan M, Shahid M, et al. Comparative cholinesterase, α-glucosidase inhibitory, antioxidant, molecular docking, and kinetic studies on potent succinimide derivatives. Drug Design, Dev Ther. 2020;14:2165–78.10.2147/DDDT.S237420Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Jan MS, Ahmad S, Hussain F, Ahmad A, Mahmood F, Rashid U, et al. Design, synthesis, in-vitro, in-vivo and in-silico studies of pyrrolidine-2, 5-dione derivatives as multitarget anti-inflammatory agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;186:111863.10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111863Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Rahim H, Sadiq A, Khan S, Amin F, Ullah R, Shahat AA, et al. Fabrication and characterization of glimepiride nanosuspension by ultrasonication-assisted precipitation for improvement of oral bioavailability and in vitro α-glucosidase inhibition. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:6287–96.10.2147/IJN.S210548Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Yao X, Zhu L, Chen Y, Tian J, Wang Y. In vivo and in vitro antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibitory effects of flavonoids from Cichorium glandulosum seeds. Food Chem. 2013;139(1–4):59–66.10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.045Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Kinsner-Ovaskainen A, Rzepka R, Rudowski R, Coecke S, Cole T, Prieto P. Acutoxbase, an innovative database for in vitro acute toxicity studies. Toxicol vitro. 2009;23(3):476–85.10.1016/j.tiv.2008.12.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Barkat MA, Mujeeb M. Comparative study of Catharanthus roseus extract and extract loaded chitosan nanoparticles in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Int J Biomed Res. 2013;4(12):670–8.10.7439/ijbr.v4i12.412Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Hussain F, Khan Z, Jan MS, Ahmad S, Ahmad A, Rashid U, et al. Synthesis, in-vitro α-glucosidase inhibition, antioxidant, in-vivo antidiabetic and molecular docking studies of pyrrolidine-2, 5-dione and thiazolidine-2, 4-dione derivatives. Bioorganic Chem. 2019;91:103128.10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103128Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Chandirasegaran G, Elanchezhiyan C, Ghosh K, Sethupathy S. Determination of antidiabetic compounds from Helicteres isora fruits by oral glucose tolerance test. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2016;6(2):172–4.10.7324/JAPS.2016.60227Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Kifle ZD, Enyew EF. Evaluation of in vivo antidiabetic, in vitro α-amylase inhibitory, and in vitro antioxidant activity of leaves crude extract and solvent fractions of Bersama abyssinica fresen (melianthaceae). J Evidence-Based Integr Med. 2020;25:2515690X20935827.10.1177/2515690X20935827Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] King H, Finch C, Collins A, King LF, Zimmet P, Koki G, et al. Glucose tolerance in Papua New Guinea: ethnic differences, association with environmental and behavioural factors and the possible emergence of glucose intolerance in a highland community. Med J Aust. 1989;151(4):204–10.10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb115991.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”