Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

-

Lan Anh Thi Nguyen

Abstract

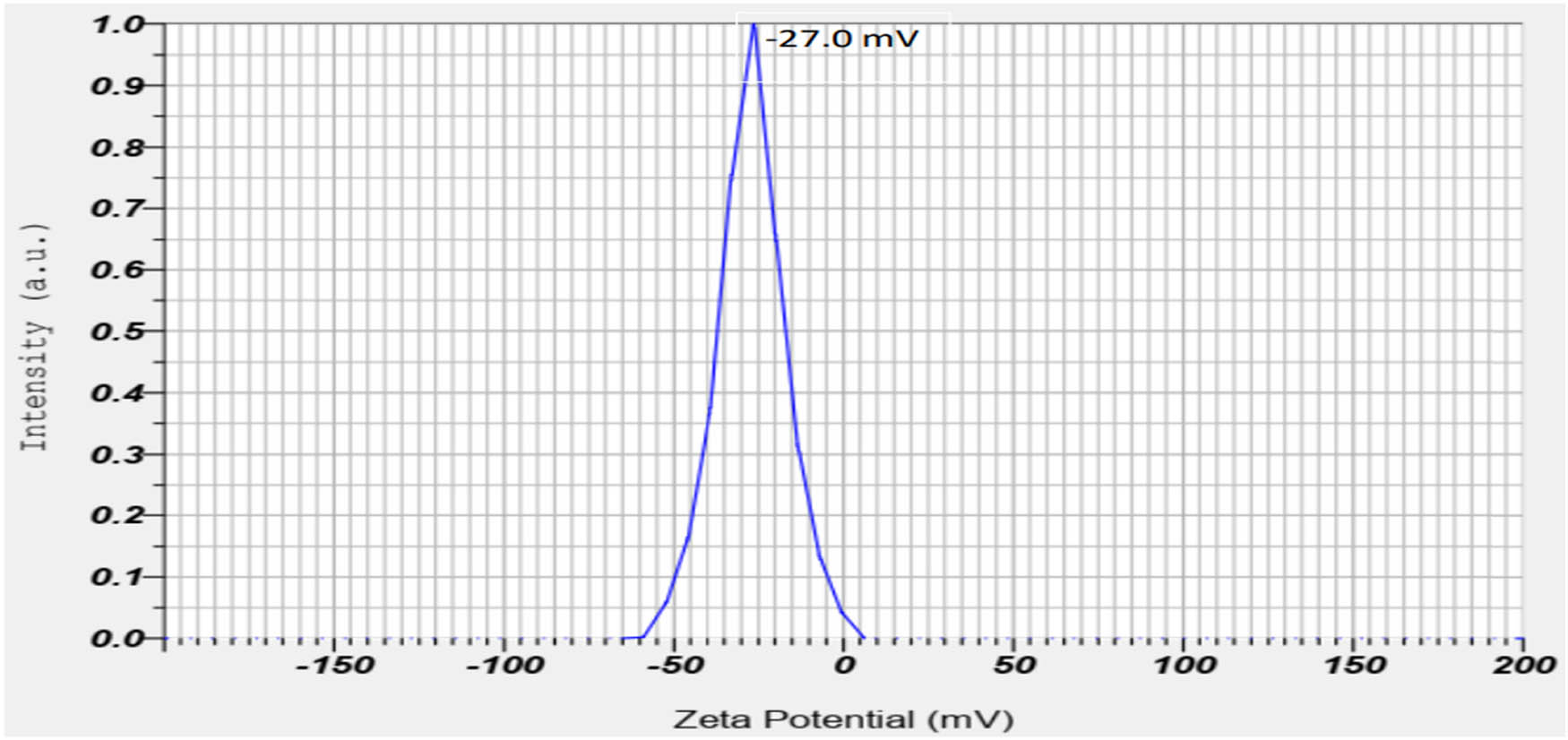

This article presents a simple, eco-friendly, and green method for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from AgNO3 solution utilizing an aqueous extract of Callisia fragrans leaf. The effects of C. fragrans leaf extraction conditions were evaluated. Parameters affecting the synthesis of AgNPs, such as the volume of extract, pH, temperature, and reaction time were investigated and optimized. The obtained AgNPs were analyzed by UV–Vis spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction pattern, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, field emission scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), dynamic light scattering (DLS), and FTIR techniques. TEM and DLS analyses have shown that the synthesized AgNPs were predominantly spherical in shape with an average size of 48 nm. The zeta potential of the colloidal solution of AgNPs is −27 mV, indicating the dispersion ability of AgNPs. The results of GC–MS and FTIR analyses show the presence of biomolecules in the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf that acts as reducing and capping agents for the biosynthesis of AgNPs. The synthesized AgNPs demonstrate anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines, with inhibitory concentrations at 50% (IC50 values) of 2.41, 2.31, 2.65, 3.26, and 2.40 µg·mL−1, respectively. The obtained results in the study show that the biosynthesized AgNP from C. fragrans leaf extract can be further exploited as a potential candidate for anticancer agents.

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is one of the most active fields of research in materials science. Nanoparticles have completely new and improved properties based on specific characteristics such as their size, distribution, and morphology. The development of reliable, eco-friendly processes for the synthesis of nanomaterials is an important aspect of nanotechnology, which is called green nanotechnology. Nanoparticles of metals are well recognized to have significant applications in electronics, magnetic, optoelectronics, and information storage [1]. In medicine, metallic nanomaterial like gold, silver, iron, copper, tellurium, and zinc oxide nanoparticles reported to play a powerful role in antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer [2–5].

Among the various metal nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have found applications in products ranging from food, medicine, and consumer products to washing machines [6–8]. Moreover, AgNPs have recently attracted attention as the anticancer agent against the cell lines such as MCF-7, Hep2, HepG2, HCT-116 colon, HT29, HELA, Caco2, and A549 [9–19]. The main mechanisms of AgNPs in cancer therapy also suggest that AgNPs induce cell death through reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, activation of caspase 3, and DNA fragmentation [20].

AgNPs are typically synthesized by different methods such as physical and chemical methods. The physical methods include laser ablation [21], spark discharging [22], and pyrolysis [23]. The chemical methods are electrochemical reduction [24], chemical reduction [25], solution irradiation [26], etc. The major process involved in chemical synthesis is the reduction of Ag+ ions to AgNPs.

The major disadvantage in the physical method is the low yield and complex instruments. The disadvantage in the chemical method is the use of toxic solvent and expensive stabilizing agents are also required to prevent the aggregation of nanoparticles to make them physiologically compatible, which may pose potential environmental and biological risks [27]. Thus, the development of the green methods for the synthesis of AgNPs is of great scientific interest. The main advantages of biological method for AgNPs synthesis are its simplicity, low cost, non-toxicity, and ease of upscaling. Several biological systems including bacterial [28], fungi [29], algae [30], yeast [31], chitosan [32], and particularly plant extracts [33–42] have been used in the synthesis of AgNPs.

The synthesis of AgNPs employing reducing agents from plant extracts is based on the redox reactions of biological compounds in the extracts such as flavonoids, terpenoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, and sugars with Ag+ [43]. The functional groups in phytochemical compounds, whose redox potential is less than that of silver ion can reduce silver cation to silver atoms, which then aggregate to form AgNPs. The biological compounds are adsorbed on the surfaces of newly-synthesized AgNPs, encapsulating them to prevent agglomeration and stabilize the AgNPs colloidal solution. The synthesis of AgNPs using plant extracts does not use any harmful chemicals, and the applicability of AgNPs colloidal solutions is becoming increasingly promising, thanks to the binding of bioactive compounds in plant extracts to the surfaces of AgNPs. The presence of substances extracted from herbal plants on the surface of AgNPs has significantly increased the application of AgNPs in medicine. In addition, the green synthesis of AgNPs employing plant extracts can be carried out under simple conditions. The major limitation of the synthesis of nanoparticles using plants is the long hours required for the synthesis, and the formation of polydisperse mixture of nanoparticles.

Callisia fragrans is an herbaceous plant with small white fragrant flowers and waxy leaves, which can be found widely in Vietnam (its Vietnamese name is Luoc Vang). In Vietnam C. fragrans leaves have been used in traditional medicines for treating skin diseases, burns, and joint disorders. C. fragrans leaves contain biologically active compounds such as flavonoids, neutral glycol- and phospholipids, and fatty acids [44,45]. Accordingly, C. fragrans is considered as an antiviral and antibacterial drug [46].

In this study, we have developed a green method for the synthesis of AgNPs using C. fragrans leaf aqueous extracts which have been demonstrated as a facile, cheap, and environmentally friendly method. The anticancer activities of the synthesized AgNPs were also investigated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Silver nitrate (AgNO3), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), n-hexane (C6H14), chloroform (CHCl3), ethyl acetate (CH3COOC2H5), and ethanol (C2H5OH) were purchased from Merck chemical company (Germany). Fresh C. fragrans leaves were collected from various locations in Da Nang City, Vietnam. All aqueous solutions were made using double-distilled water.

The cell lines of human breast carcinoma (MCF-7), human lung carcinoma (Lu-1), human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human carcinoma in the mouth (KB), and human gastric carcinoma (MKN-7) were obtained from Long-Island University, USA and Milan University, Italia.

2.2 Preparation of leaf extract

The leaves were washed thoroughly with double-distilled water and then dried by air. Predetermined masses of leaves were cut into fine pieces. The influences of the ratio of C. fragrans leaf mass/water volume, extraction time, and extraction temperature to the efficacy of C. fragrans leaf extraction were investigated. After the boiling process, the extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper to obtain an aqueous extract, which was directly used in the synthesis of AgNPs or stored at 4°C for further experiments.

2.3 Phytochemical screening of aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf

The aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf was screened for the presence of phytochemicals like terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, and saponins using standard color tests [47].

2.4 Chemical constituent of aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf

The aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf is extracted by liquid–liquid method with n-hexane, chloroform, and ethyl acetate solvents to, respectively, yield n-hexane extract, chloroform extract, and ethyl acetate extract. The remaining aqueous extract were concentrated and dissolved in ethanol to obtain ethanol extract. These extracts are subjected to GC–MS analysis using GC–MS 7890B-5977B – Agilent. A capillary column HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. and 0.25 μm film thickness) was used for separating the components. Helium gas was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.1 mL·min−1. The temperature of the oven varied from 40°C to 280°C at a rate of 5 min−1 with a holding time of 1–10 min. The injector temperature was 270°C, and the injection volume was 1.0 μL. The identification of components of the extracts was based on a comparison between Kovat’s retention indices and mass spectra that corresponded with data (Adam, 1989) and mass spectra libraries (National Institute of Standards and Technology 98).

2.5 Synthesis of AgNPs

For the synthesis of AgNPs, a definite volume of leaf extract was mixed with a volume of 1 mM AgNO3 in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The reaction was carried out by placing the flasks in a water bath for a specified synthesis time and temperature. The color change in the colloidal solutions occurred indicating the formation of AgNPs. The influence of some factors such as the volume ratio of C. fragrans leaf extract/AgNO3 solution, pH, reaction temperature, and reaction time for the synthesis of AgNPs was investigated.

2.6 Characterization of AgNPs

The formation of AgNPs was characterized by UV–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy. The synthesized AgNPs solution was diluted ten times and measured using the UV–Vis spectra. The UV–Vis spectra of these samples were measured between 350 and 700 nm on a UV–VIS Perkin Elmer Lambda 365 spectrophotometer operated at a resolution of 1 nm. The samples for electron microscopy were gold coated (JEOL, Model No. JFC-1600), and images were obtained by scanning electron microscope (ZEISS EVO-MA 10, Oberkochen, Germany). The samples for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis were prepared by drop coating biologically synthesized AgNPs solution onto carbon-coated copper TEM grids. TEM measurements and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis were carried out using HRTEM Tecnai G2 F20. Crystal phase identification of AgNPs was characterized by powder X-ray diffraction using a Panlytical X Pert PRO Diffractometer. The diffracted intensities were recorded from 10° to 70° 2θ angles. The zeta potential and hydrodynamic size were calculated using HORIBA SZ-100. FTIR was carried out with JASCO FT/IR-6800 to investigate the type of functional groups involved in the reduction and capping of AgNPs.

2.7 Evaluation of in vitro cytotoxic activity of the AgNPs on cancer cell lines

The in vitro cytotoxicity of AgNPs was determined using human breast carcinoma (MCF-7), human lung carcinoma (Lu-1), human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human carcinoma in the mouth (KB), and human gastric carcinoma (MKN-7) cell lines. These tests were performed by the Institute of Biotechnology – Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology according to the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. The test was carried out to determine the total cellular protein content based on the optical density (OD) measured when the protein composition of the cells was stained with SRB. The measured OD value is directly proportional to the amount of SRB bonded to the protein molecule, so the more the cells (the more protein) the larger the OD value. The test was carried out under the following specific conditions: trypsinizing experimental cells to separate cells and counting in a counting chamber to adjust the density to suit the experiment. Proceed to put 190 µL of cells in 96-well plate for testing. The prepared sample (10 µL) was introduced into the wells of the cell-prepared test a 96-well plate. Wells without reagent but contained cancer cells (190 µL) + DMSO 1% (10 µL) were used as day 0 control. After 1 h, cells were fixed with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 20% in day 0 control wells. Cells were then incubated in the incubator for 72 h. After 72 h, the cells were fixed with TCA for 1 h, stained with SRB for 30 min at 37°C, washed three times with acetic acid, and then dried at room temperature. Unbuffered Tris base of 10 mM was used to dissolve the amount of SRB, then the mixture was shook gently for 10 min. The OD result was determined at 540 nm on an ELISA Plate Reader (Biotek). The inhibition percentage of cell growth in the presence of reagents is calculated by the following equation:

Ellipticine at concentrations of 10, 2, 0.4, and 0.08 µg·mL−1 was used as the reference control; 1% DMSO was used as a negative control (final concentration in the test well is 0.05%). All experiments were performed in triplicate and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The IC50 value (concentration that inhibits 50% of growth) was determined using Table Curve 2Dv4 computer software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Optimization for the extraction of C. fragrans leaf

The influence of some factors on the extraction process of phytochemical compounds present in C. fragrans leaf was studied. The obtained extract of C. fragrans leaves (10 mL) was mixed with 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 solution in Erlenmeyer flasks. The flask was kept in a water bath at 70°C for 60 min. A change in the color was observed indicating the formation of AgNPs.

3.1.1 Effect of solid/liquid ratio

The effect of the ratio of C. fragrans leaf weight/distilled water volume on the formation of AgNPs was studied with experimental parameters as follows. The time of extraction was 60 min and the extraction temperature was 60°C. The ratio of C. fragrans leaf weight/distilled water volume varied from 5 g·100 mL−1 to 10 g·100 mL−1, 15 g·100 mL−1, 20 g·100 mL−1, and 25 g·100 mL−1. The UV–Vis spectra (Figure 1) show the effect of C. fragrans leaf weight/distilled water volume on the formation of AgPNs from 1 mM AgNO3. Characteristic surface plasmon absorption was observed at 420–460 nm for the brown-colored AgNPs.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized at the ratio of C. fragrans leaf weight/distilled water volume.

The results of Figure 1 show that the intensity of absorption peak increased along with the increase of the ratio of C. fragrans leaf from 5 g to 15 g·100 mL−1 of distilled water. The reason is that when the C. fragrans leaf content increases, the amount of reducing agent is more separated, so the concentration of AgNP is more. However, as the content of C. fragrans leaf increased up to 20 g and 25 g·100 mL−1, the intensity of the absorption peak of the obtained AgNPs solution decreased dramatically. This can be explained as follows: when the weight of C. fragrans leaf exceeds 15 g, it is possible to create many substances that speed up the creation of AgNPs drastically, the formed particles then coagulate easily into larger-sized version, reducing the intensity of absorption peak [48]. So the optimal solid/liquid ratio is 15 g of C. fragrans leaf per 100 mL of distilled water.

3.1.2 Effect of extraction time

The effect of extraction time of C. fragrans leaf on the formation of AgNPs was studied under the following conditions: 15 g C. fragrans leaf per 100 mL of distilled water, the temperature of extraction was 60°C, and the time for extraction t = 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 min.

The results of Figure 2 show that the absorption of the synthesized AgNPs solution increased with the increase in the extraction time from 30 to 70 min. As the extraction time was prolonged (80 and 90 min), the intensity of AgNPs absorption decreased considerably. A possible reason for this is that at the extraction time of 70 min, the appropriate amount of reducing agent to reduce the largest amount of silver ions to silver was produced. Beyond this point, substances that are not beneficial to the process of creating AgNPs may be formed or coagulation may occur, reducing the intensity of absorption peak. Thus, the suitable time for the extraction of C. fragrans leaf was 70 min.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized at various extraction times.

3.1.3 Effect of extraction temperature

The effect of extraction temperature of C. fragrans leaf on the formation of AgNPs was studied with experimental parameters as follows: 15 g of C. fragrans leaf per 100 mL of distilled water, an extraction time of 70 min, and the temperature for extraction at 60°C, 70°C, 80°C, 90°C, and boiling temperature.

The obtained results are shown in Figure 3. The intensity of AgNPs absorption increased when extraction temperature increased from 60°C to boiling temperature. Thus, the increase in the intensity of peak can be correlated with an enhancement in the extraction temperature of C. fragrans leaf because the higher the extraction temperature, the higher the amount of reducing agent separated. In accordance to above reported results, Ahmadi and coworkers [40] and many others have shown that the preparation of extract by boiling the plant in the water was proved in the synthesis of AgNPs.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized at various extraction temperatures.

In summary, the optimum extraction conditions of phytochemical compounds from C. fragrans leaf were found to be 15 g of C. fragrans leaf per 100 mL of double distilled water, extraction time of 70 min, and boiling temperature.

3.2 Phytochemical screening of aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf

Standard phytochemical tests were conducted to find the presence of metabolites like terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, tannin, and saponin in the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf. The results of the phytochemical screening are presented in Table 1.

Phytochemical screening of aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf

| Phytochemical | C. fragrans leaf extract |

|---|---|

| Terpenoids | + |

| Flavonoids | + |

| Alkaloids | − |

| Tannin | + |

| Saponin | + |

− indicates absence, + indicates presence.

It is well evident from the table that the aqueous extract was rich in metabolites like terpenoids, flavonoids, tannin, and saponin. These biological compounds are reducing and stabilizing agents for the synthesis of AgNPs [43].

3.3 Chemical constituents of C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract by GC/MS

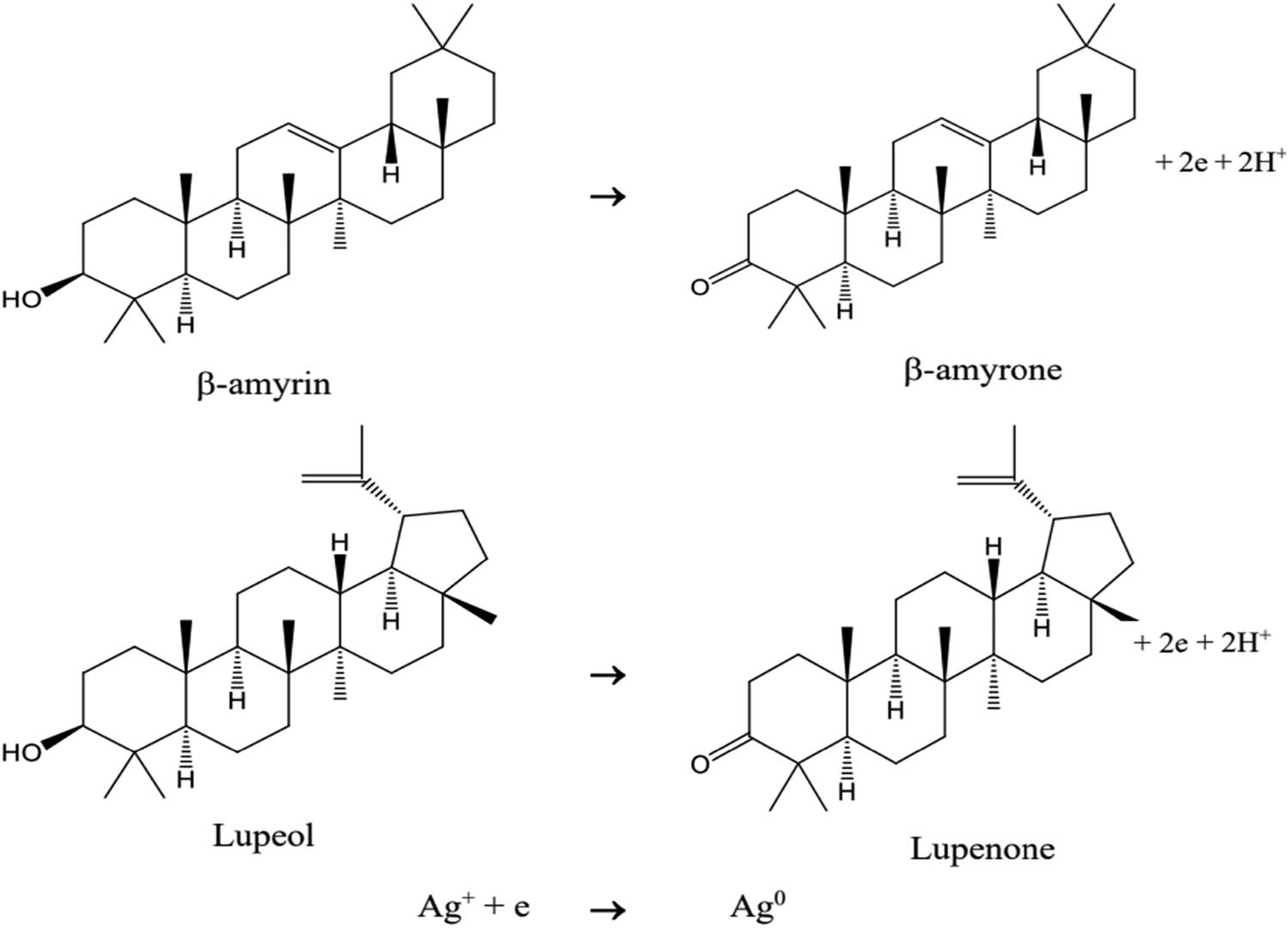

The GC/MS analysis of C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract, as given in Table 2, revealed its richness with many bioactive compounds such as beta-amyrin, lupeol, and vitamin E. Beta-amyrin and lupeol are triterpenoids, which are reducing agents for the synthesis of AgNPs and are known to possess potent bioactivities such as anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities.

GC–MS analysis of C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract

| Compound | Chemical formula |

|---|---|

| Alpha-pinen | C10H16 |

| Beta-amyrin | C30H50O |

| Caryophyllene | C15H24 |

| Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O |

| Cetene | C16H32 |

| Cyclohexadecane, 1,2-diethyl- | C20H40 |

| 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | C14H22O |

| Dihydroactinidiolide | C11H16O |

| Docosyl trifluoroacatate | C24H45F3O2 |

| Dodecane | C12H26 |

| 1-Dodecene | C12H24 |

| Eicosane | C20H42 |

| 5-Eicosene, (E)- | C20H40 |

| Eucalyptol | C10H18O |

| E-15-heptadecenal | C17H32O |

| Hentriacontane | C31H64 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | C18H36O2 |

| Humulenen | C15H24 |

| Lupeol | C30H50O |

| Nanocos-1-ene | C29H58 |

| Octadecanoic acid | C18H36O2 |

| Propane, 1,1,2,3,3-pentachloro | C3H3Cl3 |

| Phytol | C20H40O |

| Spathulenol | C15H24O |

| 2-Tetradecene, (E)- | C14H28 |

| Tetracosane | C24H50 |

| Tridecane | C13H28 |

| Vitamin E |

3.4 Optimization of various parameters to improve the AgNPs synthesis

The effect of mixing ratio (volume of extract per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3), temperature, pH, and time, which influence the formation of AgNPs was studied in detail.

3.4.1 Effect of mixing ratio on the formation of AgNPs

To assess the effect of mixing ratio on the formation of AgNPs, 14 samples were tested (from mixing ratio of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 mL of extract volume per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 solution volume). The samples after color change were measured by spectroscopy within the wavelength of 350–700 nm (Figure 4).

UV–Vis spectra show effect of mixing ratio of extract volume per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 solution in the formation of AgNPs.

By changing the mixing ratio in similar environmental conditions, the observed wavelength of maximum peak (λmax) did not change much. However, by increasing the extract volume, the absorption intensity rose and reached its peak at 10 mL of extract per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3. This occurred by increasing the extract volume of C. fragrans leaf, leading to an increase in the concentration of terpenoids, flavonoids, tannin, saponin, etc., which is responsible for the forming and stabilizing of AgNP. As the extract volume continued to increase (11–15 mL), the absorption intensity decreased. The reason may be that when the extract volume increased, the concentration of the reducing agent in the extract also increased, thus raising the rate of AgNPs generation, thereby leading to an increase in the particle size and reducing the absorption intensity. Thus, the optimal volume of C. fragrans leaf extract V = 10 mL per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 solution and the synthesized AgNP solution is not flocculated.

3.4.2 Effect of temperature on the formation of AgNPs

Temperature plays an important role in the synthesis of AgNPs. In order to study the effect of temperature, six containers containing 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 together with 10 mL extract were put at six different temperature levels of 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, 80°C, 90°C, and 100°C. The UV–Vis spectra in Figure 5 show the effect of temperature on the formation of AgNPs.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized at the different temperatures.

It can be seen from Figure 5 that the synthesis of nanoparticles increases while increasing the reaction temperature from 50°C to 80°C by using the leaf extract of C. fragrans. A higher rate of reduction occurred at higher temperature due to the consumption of silver ions in the formation of nuclei of nanoparticles.

As the reaction temperature continued to increase from 90°C to 100°C, the absorption intensity decreased, possibly due to the aggregation of nanoparticles. Mittal et al. [49] have also reported this trend in the biosynthesis of AgNPs.

According to the obtained results, 80°C was selected as the optimum temperature for this study.

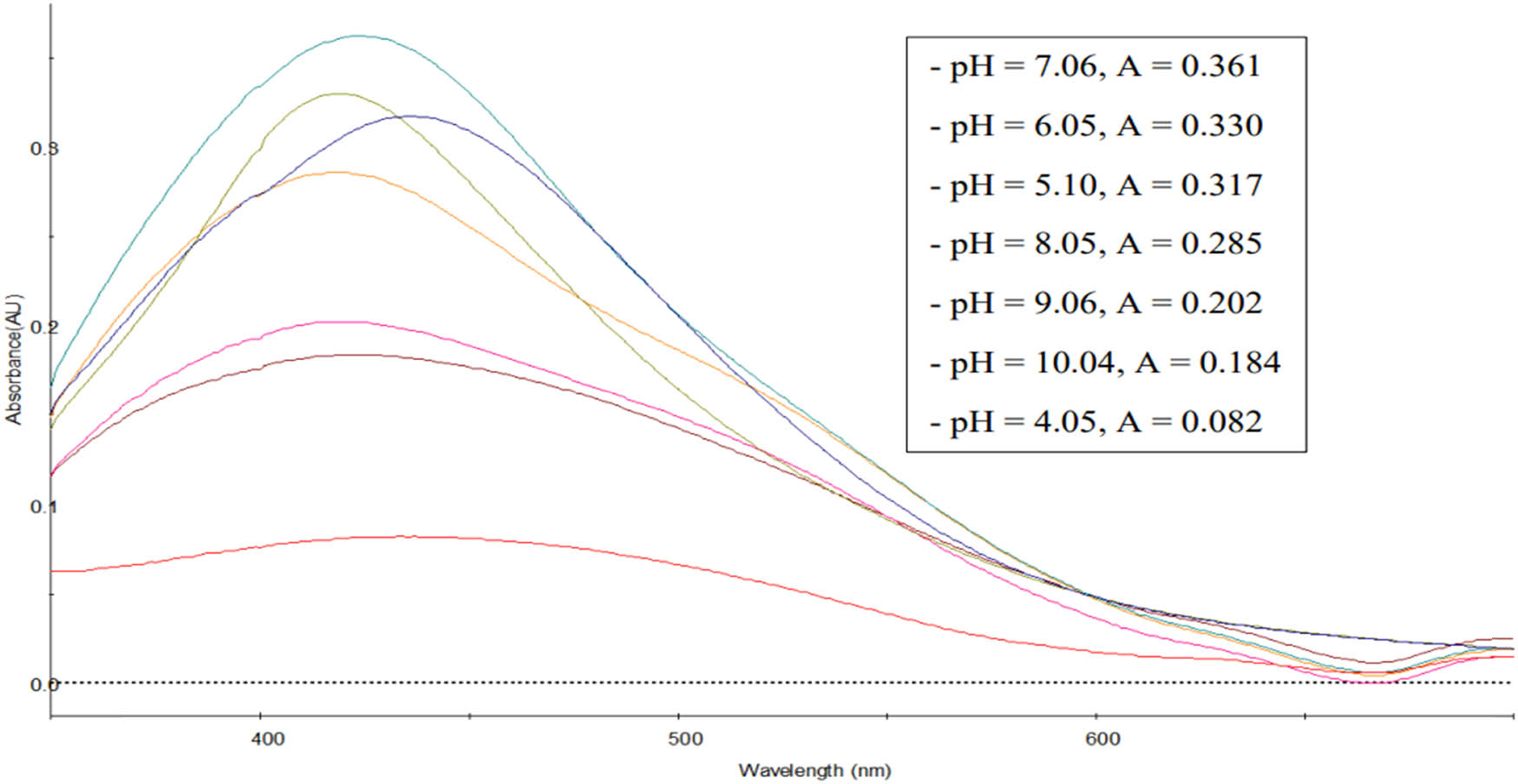

3.4.3 Effect of pH level on the formation of AgNPs

pH level plays an important role in AgNPs synthesis [50]. This factor induces the reactivity of leaf extract with silver ions. The influence of pH on the synthesis of AgNPs was evaluated under different pH levels of the reaction mixture by the leaf extract (Figure 6). The obtained results showed that the absorption peak intensity increased gradually with an increase in pH, suggesting that the reduction rate of silver ions increases with the increase in pH. These results are congruent with those reported by other works [51–54]. They attributed this behavior to the possible ionization of the phenolic and tannin compounds present in the mentioned extracts. At low pH, a small with broadening SPR band was formed, indicating the formation of a large amount of AgNPs. As the pH level increased from 4.05 to 7.06, the absorption intensity values rose and reached the highest value at pH = 7.06 with a sharp peak. However, at pH = 8.05, 9.06, and 10.04, the amount of AgNPs was formed too fast, leading to coagulation; AgNPs have large size, which reduces the absorption intensity values. Similarly, Sarsar et al. [55] reported that the AgNP synthesis using P. guajava leaf extract, pH 7.0 was optimum for the synthesis of the nanoparticles.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized at various pH.

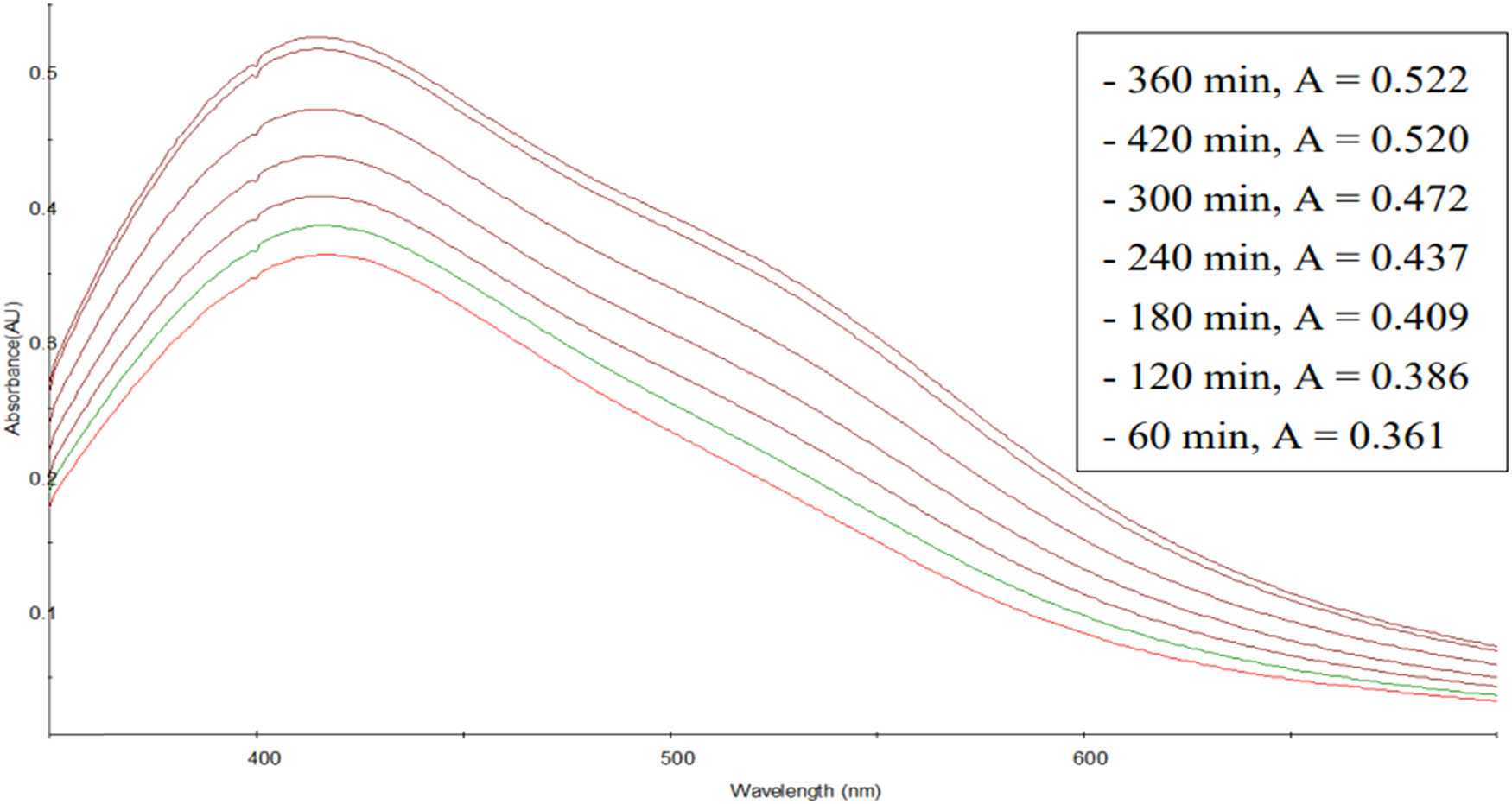

3.4.4 Effect of reaction time on the formation of AgNPs

The influence of reaction time on the synthesis of AgNPs was evaluated with the results shown in Figure 7.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesized as a function of time.

Figure 7 shows that as the reaction time of the synthesis of AgNPs increased, the measured absorption intensity value also grew. This can be explained that the longer the reaction time, the stronger the reaction of the substances in the extract with Ag+ ions to create AgNPs, leading to a higher absorption intensity. After 360 min, the synthesis of AgNPs by C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract is considered complete.

In summary, the optimal conditions for the synthesis of AgNPs using C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract are 10 mL of extract per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 solution, pH 7.06, reaction temperature 80°C, and reaction time 360 min.

3.5 Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), TEM, EDX, and X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) analysis of AgNPs

FE-SEM and TEM images of the produced AgNPs are shown in Figure 8. The shapes of AgNPs were spherical.

FE-SEM and TEM micrographs of AgNPs synthesized by aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf.

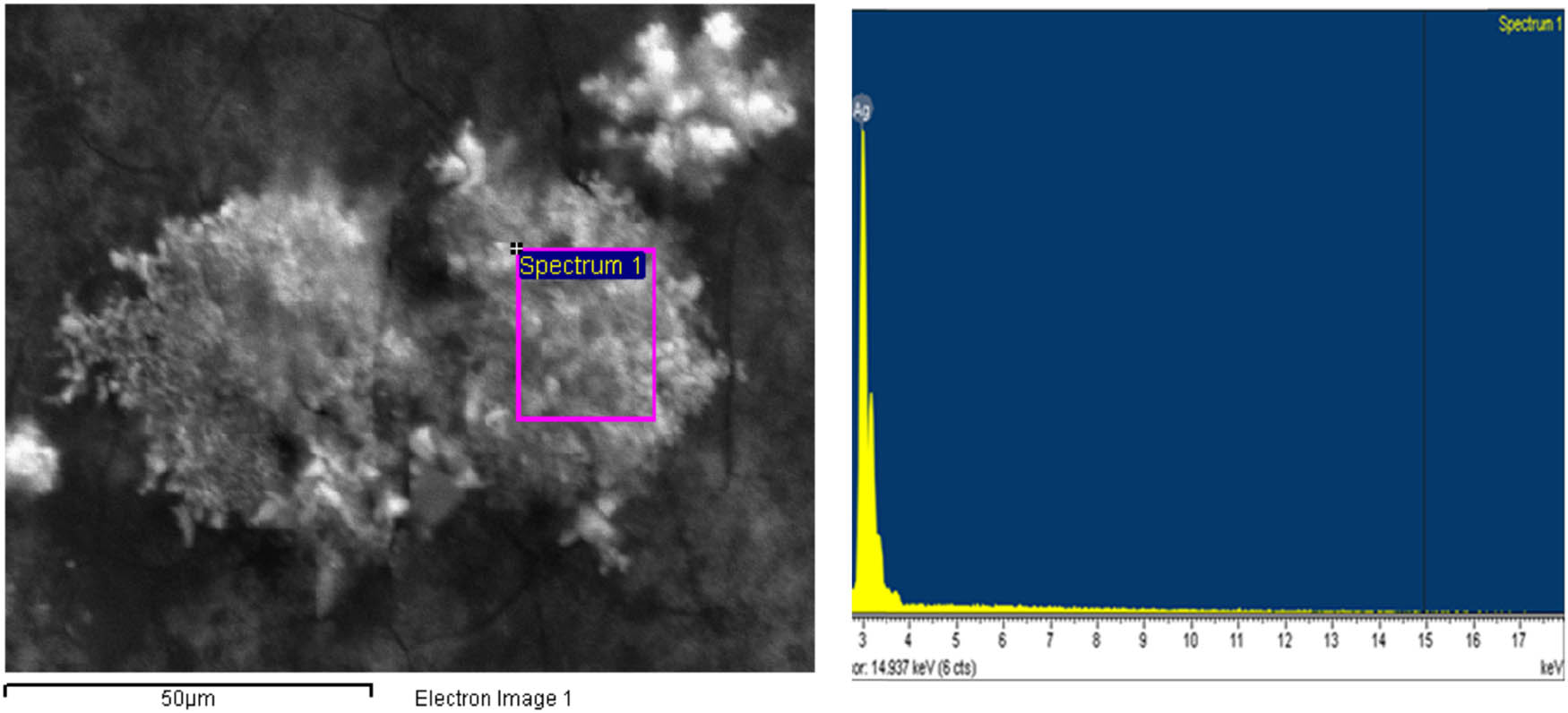

EDX spectra recorded from the AgNPs are shown in Figure 9.

EDX micrograph of AgNPs synthesized by aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf. The EDX spectra of the biosynthesized AgNPs show silver element, indicating that the reduction of Ag ions to AgNPs had occurred in the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf. Carbon and oxygen are also present in the EDX graph due to the organic molecules found in the extract of the C. fragrans leaves. These biomolecules capped the AgNPs as capping and stabilizing agents.

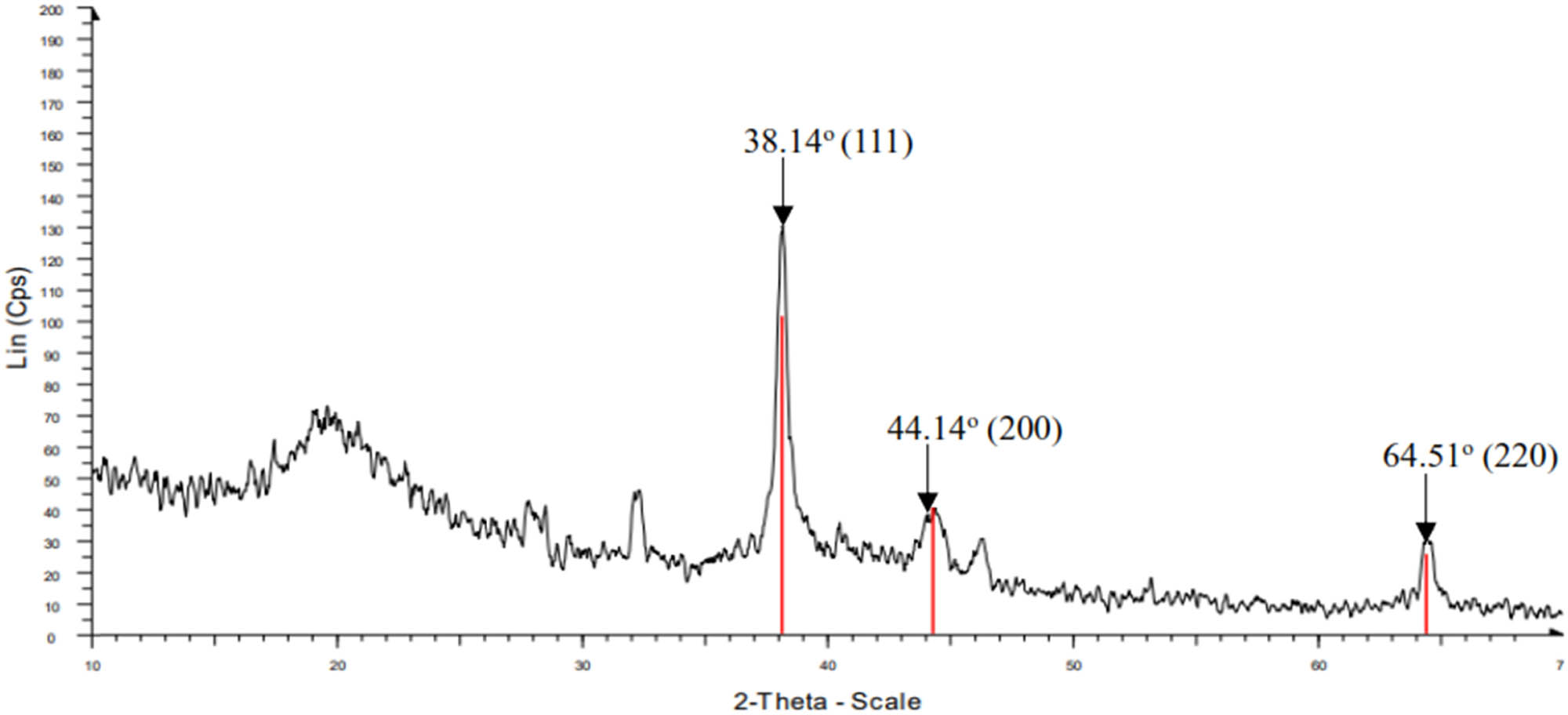

X-ray diffraction pattern of AgNPs synthesized by C. fragrans leaf extract is shown in Figure 10. The diffraction peaks at 2θ = 38.14°, 44.14°, and 64.51° correspond to the (111), (200), and (220) faces of the silver fcc crystal structure, respectively.

XRD pattern of AgNPs synthesized by C. fragrans leaf aqueous extract.

3.6 Nanoparticle size distribution and zeta potential

The hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of spherical AgNPs were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Results show that the AgNPs synthesized by extract of the C. fragrans leaf with the average nanoparticle size was around 48.0 nm (Figure 11). The value of polydispersity index (PDI) may vary from 0.01 (mono-dispersed particles) to 0.5–0.7, whereas PDI index value >0.7 indicated broad particle size distribution of the formulation and is probably not suitable to be analyzed by the DLS technique The polydispersity index of AgNPs synthesized by the extract of the C. fragrans leaf was 0.523, indicating the formation of polydisperse mixture of nanoparticles [56].

Size distribution mean of biosynthesized AgNPs from C. fragrans leaf extracts in nm.

The surface charges and stability of the nanoparticles in the suspension were measured through zeta potential and the value was about −27.0 mV (Figure 12), which indicated negative charges on the formed AgNPs. This result showed that the use of the extract of the C. fragrans leaf allows obtaining stable AgNPs without a stabilizer.

Zeta potential of AgNPs from C. fragrans leaf extracts in mV.

3.7 FTIR spectra of C. fragrans leaf extract and biosynthesized AgNPs

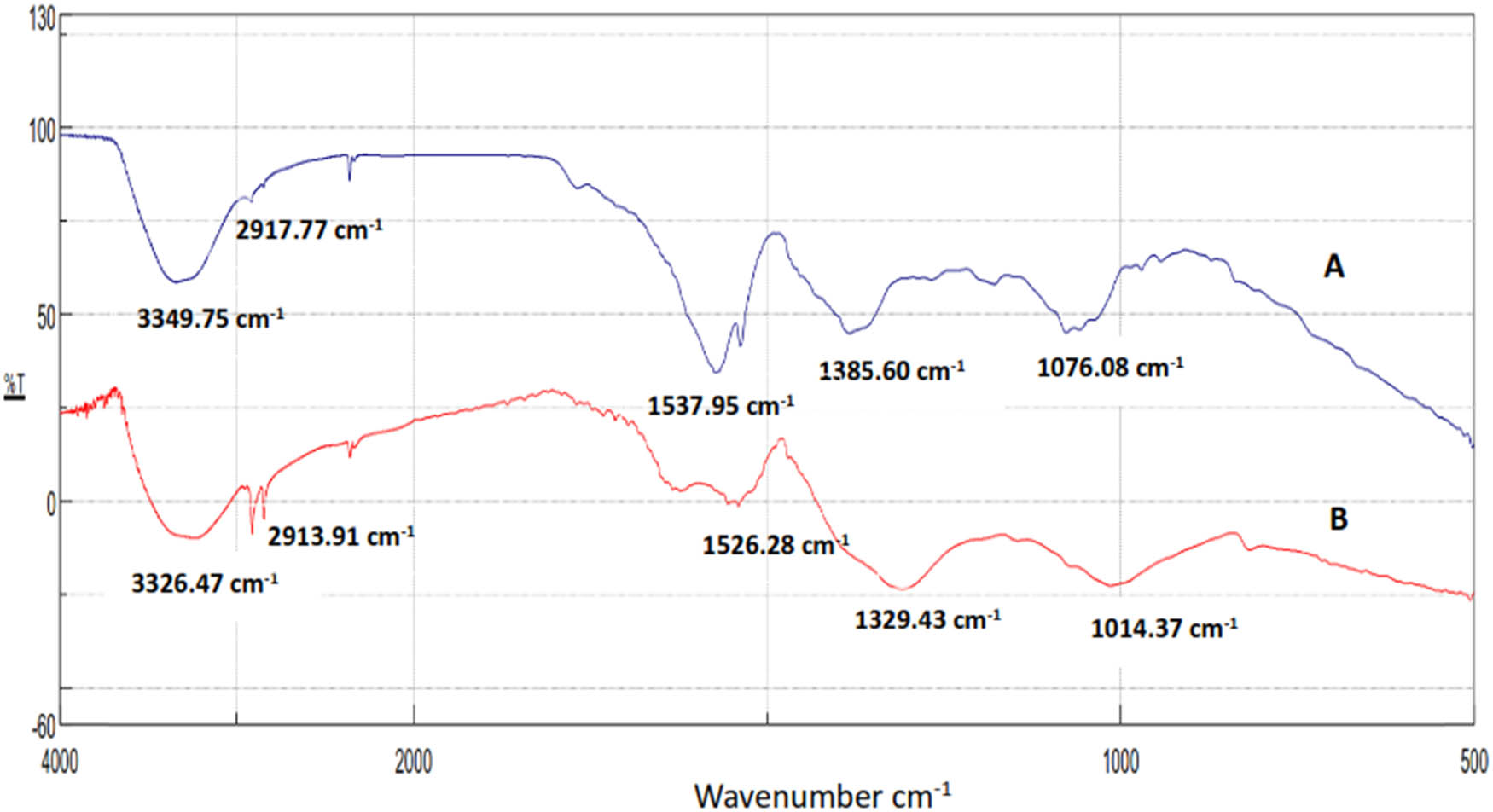

FTIR measurement was used to determine the presence of bioactive molecules that could be responsible for AgNP stabilization by acting as capping agents. The absorption spikes at 3,349.75, 2,917.77, 1,537.95, 1,385.60, and 1,076.08 cm−1 were determined for C. fragrans leaf extract, while AgNPs shows absorption spikes at 3,326.47, 2,913.91, 1,526.28, 1,329.43, and 1,014.37 cm−1 ((A) and (B) in Figure 13). Higher peaks at 3,349.75 and 3,326.47 cm−1 can be attributed to bounded hydroxyl (–OH) in alcohols in the C. fragrans leaf extract. The presence of smaller bands at 2,917.77 and 2,913.91 cm−1 for extract and AgNPs was due to the –CH stretching in alkanes. Peaks at 1,537.95 cm−1 (extract) and 1,526.28 cm−1 (AgNPs) correspond to the C═O group. The bands at 1,385.60 cm−1 (extract) and 1,329.43 cm−1 (AgNPs) correspond to the C–O–C group. The peaks at 1,076 cm−1 (extract) and 1,014 cm−1 (AgNPs) are attributed to the C–O stretching in esters that were found in the leaf extract. The spectrum of AgNPs ((B) in Figure 13) was observed to be similar to (A) in Figure 13 regarding the sites of the functional groups. Therefore, these groups found in plant leaf extracts were responsible for silver nitrate reduction to AgNPs and capping nanoparticles for stabilization and preventing their aggregation in the medium.

FTIR spectra of C. fragrans leaf extracts (A) and AgNPs biosynthesized using the leaf extracts (B).

3.8 Mechanism of the formation of AgNPs by aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf

Based on the results of phytochemical screening and determination of chemical compositions by GC–MS, the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf contains functional groups of terpenoids, flavonoids, tannin, and saponin; these groups of substances will act as the reducing agent Ag+ to Ag [57,58]. In particular, the presence of β-amyrin and lupeol with the –OH group in the ring may undergo oxidation and get converted to quinone forms of β-amyrone and lupenone, respectively. The synthesized AgNPs are stabilized through the lone pair of electrons and p electrons of quinone structures of lupenone and β-amyrone and other organic compounds in the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaves (Figure 14).

Mechanism of reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 by C. fragrans leaf extract.

Figure 14 shows that, when the pH level of the solution is low, the oxidation reactions of β-amyrin and lupeol are not favored, so the ability to reduce Ag+ into Ag decreases. When the pH of the solution increases, the equilibrium of the oxidation reaction of β-amyrin and lupeol shifts from rightward, raising the rate of the reduction reaction Ag+ → Ag and the amount of synthesized AgNPs. This reaction mechanism is consistent with the results produced from investigating the effect of pH on the synthesis of AgNPs.

3.9 Anticancer activity

The viability of MCF-7 (human breast carcinoma), LU-1 (human lung carcinoma), HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma), KB (human carcinoma in the mouth), and MKN-7 (human gastric carcinoma) cancer cells with AgNPs for 72 h was determined using the colorimetric SRB assay.

The obtained results showed that MCF-7 cells proliferation was significantly inhibited by AgNPs with an IC50 value of 2.41 µg·mL−1, HepG2 cells with an IC50 value of 2.31 µg·mL−1, KB cells with an IC50 value of 2.65 µg·mL−1, LU-1 cells with an IC50 value of 3.26 µg·mL−1 of the concentration and MKN-7 cells with an IC50 value of 2.40 µg·mL−1. The cytotoxicity of metal nanomaterials is associated with the various parameters such as sizes, morphologies, and surface charges as well as different biological resources that act as reducing and capping agents [59–61]. The IC50 values (2.41 and 2.31 µg·mL−1) for MCF-7 and HepG2 cancer cell lines of AgNPs synthesized from the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaves are low compared to the IC50 values of AgNPs synthesized from other plant extracts [62–64]. The reason is that extracts of C. fragrans leaves contain beta-amyrin and lupeol. These substances participate in a redox reaction with Ag+ ions to convert to beta-amyrone and lupenone, which are active substances with excellent anticancer properties [65,66]. The presence of these substances on the surface of AgNPs has significantly increased the anticancer ability of AgNPs. Thus, AgNPs were synthesized in this study and showed good anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines (Figure 15, Table 3).

Anticancer activity of C. fragrans leaf AgNPs against MCF-7, HepG2, MKN7, LU-1, and KB cell lines (the magnification in microscopic images is 20×).

In vitro cytotoxicity effect of AgNPs from the C. fragrans leaf on cancer cell lines represented as cell inhibition percentage ± standard deviation

| Concentration (ppm) | MCF-7 | HepG2 | KB | LU-1 | MKN-7 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of inhibition | SD | % of inhibition | SD | % of inhibition | SD | % of inhibition | SD | % of inhibition | SD | |

| 3.75 | 79.40 | 2.78 | 82.57 | 2.55 | 75.64 | 3.73 | 62.95 | 3.10 | 80.81 | 2.13 |

| 0.75 | 14.74 | 1.49 | 16.41 | 0.16 | 11.30 | 1.40 | 7.04 | 0.63 | 13.02 | 1.13 |

| 0.15 | 5.95 | 0.48 | 7.25 | 0.27 | 1.90 | 0.16 | 3.73 | 0.44 | 1.80 | 0.48 |

| 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 2.06 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.17 | 3.47 | 0.26 | −1.98 | 0.81 |

| IC50 | 2.41 ± 0.23 | 2.31 ± 0.25 | 2.65 ± 0.39 | 3.26 ± 0.28 | 2.40 ± 0.33 | |||||

SD = standard deviation.

4 Conclusions

The bio-reduction of Ag+ ion using the aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaves leading to the formation of AgNPs of fairly well-defined dimensions has been demonstrated to have the optimal conditions of 10 mL of extract (15 g of C. fragrans leaf per 100 mL of water, extraction time 70 min, boiling temperature) per 30 mL of 1 mM AgNO3, temperature 80°C, pH = 7.06, reaction time 360 min. XRD result shows the face-centered cubic lattice of AgNPs. The synthesized AgNPs are mostly spherical in shape with an average size of 48.0 nm. The zeta potential of AgNPs is −27.0 mV. The aqueous extract of C. fragrans leaf acts as a reducing and stabilizing agent. The synthesis of AgNPs using C. fragrans leaf extract holds the environmental advantage over alternative chemical synthesis methods due to the absence of pollutants produced. Promisingly, the synthesized AgNPs demonstrated anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines. This study thus demonstrates that synthesizing AgNPs by using aqueous extract of C. fragrans not only generates considerably lower environmental impacts, but the resulting product also possesses incredible potential as life-saving anticancer agents.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by The Ministry of Education and Training of Vietnam under the grant number B2022-DNA-05.

-

Author contributions: Lan Anh Thi Nguyen: conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, and performed the analysis; Bay Van Mai: conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, and performed the analysis; Din Van Nguyen: conceived and designed the analysis and performed the analysis; Ngoc Quyen Thi Nguyen: conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, and performed the analysis; Vuong Van Pham: conceived and designed the analysis and performed the analysis; Thong Le Minh Pham: conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, performed the analysis, and writing – original draft; Hai Tu Le: conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, performed the analysis, and writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Joudeh N, Linke D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:262. 10.1186/s12951-022-01477-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Sharma A, Goyal AK, Rath G. Recent advances in metal nanoparticles in cancer therapy. J Drug Target. 2018;8:617–32. 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1400553.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Barabad H. Nanobiotechnology: a promising scope of gold biotechnology. Cell Mol Biol. 2017;63(12):3–4. 10.14715/cmb/2017.63.12.2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Vahidi H, Kobarfard F, Alizadeh A, Saravanan M, Barabadi H. Green nanotechnology-based tellurium nanoparticles: exploration of their antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic potentials against cancerous and normal cells compared to potassium tellurite. Inorg Chem Commun. 2021;124:108385.10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108385Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Cruz MD, Mostafavi E, Vernet-Crua A, Barabadi H, Cholula-Díaz LJ, Guisbiers G, et al. Green nanotechnology-based zinc oxide (ZnO) nanomaterials for biomedical applications: a review. J Phys Mater. 2020;3:034005.10.1088/2515-7639/ab8186Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Burdusel AC, Gherasim O, Grumezescu AM, Mogoantă L, Ficai A, Andronescu E. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: an up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:681.10.3390/nano8090681Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Chaloupka K, Malam Y, Seifalian AM. Nanosilver as a new generation of nanoproduct in biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(11):580–8.10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.07.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Viana RLS, Fidelis GP, Medeiros JC, Morgano MA, Alves MG, Passero LFD, et al. Green synthesis of antileishmanial and antifungal silvernanoparticles using Corn Cob Xylan as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Biomolecules. 2020;10:1235.10.3390/biom10091235Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Zulkifli NI, Muhamad M, Zain NNM, Tan WN, Yahaya N, Bustami Y, et al. A bottom-up synthesis approach to silver nanoparticles induces anti-proliferative and apoptotic activities against MCF-7, MCF-7/TAMR-1 and MCF-10A human breast cell lines. Molecules. 2020;25:4332. 10.3390/molecules25184332 Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Kaur J, Tikoo K. Evaluating cell specific cytotoxicity of differentially charged silver nanoparticles. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51(1):1–14.10.1016/j.fct.2012.08.044Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Sufyani NMA, Hussien NA, Hawsawi YM. Characterization and anticancer potential of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from Olea chrysophylla and Lavandula dentata leaf extracts on HCT116 colon cancer cells. J Nanomater. 2019;2019:7361695.10.1155/2019/7361695Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Paul JA, Selvi BK, Karmegam N. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Premna serratifolia L. leaf and its anticancer activity in CCl4-induced hepato-cancerous Swiss albino mice. Appl Nanosci. 2015;5:937–44.10.1007/s13204-014-0397-zSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Velammal PS, Devi AT, Amaladhas PT. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized using Plumbago zeylanica bark. J Nanostruct Chem. 2016;6:247–60. 10.1007/s40097-016-0198-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hawar SN, Al-Shmgani HS, Al-Kubaisi ZA, Sulaiman GM, Dewir YH, Rikisahedew JJ. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Alhagi graecorum leaf extract and evaluation of their cytotoxicity and antifungal activity. J Nanomater. 2022;2022:8. 10.1155/2022/1058119.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Younas M, Rizwan M, Zubair M, Inam A, Ali S. Biological synthesis, characterization of three metal-based nanoparticles and their anticancer activities against hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;223:112575.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112575Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Walimbe KG, Dhawal PP, Kakodkar SA. Anticancer potential of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles: a review. Eur J Biol Biotechnol. 2022;3(2):10–20. 10.24018/ejbio.2022.3.2.338.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Tadele KT, Abire TO, Feyisa TY. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles using plant extracts as promising prospect for cancer therapy: a review of recent findings. J Nanomed. 2021;4(1):1040.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Oves M, Rauf MA, Aslam M, Qari HA, Sonbol H, Ahmad I, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Conocarpus lancifolius plant extract and their antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29:460–71.10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Matteis VD, Cascione M, Toma CC, Leporatti S. Silver nanoparticles: synthetic routes, in vitro toxicity and theranostic applications for cancer disease. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:319. 10.3390/nano8050319.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Gurunathan S, Raman J, Malek ANS, John AP, Vikineswary S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ganoderma neo-japonicum Imazeki: a potential cytotoxic agent against breast cancer cells. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:4399–413.10.2147/IJN.S51881Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mafune F, Kohno J, Takeda Y, Kondow T, Sawabe H. Structure and stability of silver nanoparticles in aqueous solution produced by laser ablation. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104(35):8333–7.10.1021/jp001803bSuche in Google Scholar

[22] Tien CD, Lao Y, Huang CJ, Tseng HK, Lung KJ, Tsung TT, et al. Novel technique for preparing a nano-silverswater suspension by the arc discharge method. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2008;18:750–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Pingali CK, Rockstraw AD, Deng S. Silver nanoparticles from ultrasonic spray pyrolysis of aqueous silver nitrate. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2005;39:1010–4.10.1080/02786820500380255Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Haider JM, Mahdi SM. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by electrochemical method. Eng Tech J. 2015;33(7)Part (B):1361–73.10.30684/etj.2015.116707Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Quintero-Quiroz C, Acevedo N, Zapata-Giraldo J, Botero EL, Quintero J, Zárate-Triviño D, et al. Optimization of silver nanoparticle synthesis by chemical reduction and evaluation of its antimicrobial and toxic activity. Biomater Res. 2019;23:27. 10.1186/s40824-019-0173-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Chen P, Song L, Liu Y, Fang Y. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by γ-ray irradiation in acetic water solution containing chitosan. Radiat Phys Chem. 2007;76(7):1165–8.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2006.11.012Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Pryshchepa O, Pomastowski, P, Buszewski, B. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, investigation techniques, and properties. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;284:102246.10.1016/j.cis.2020.102246Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Rahimirad A, Javadi A, Mirzaei H, Anarjan N, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H. Biosynthetic potential assessment of four food pathogenic bacteria in hydrothermally silver nanoparticles fabrication. Green Process Synth. 2019;8:629–34. 10.1515/gps-2019-0033 Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, Senapati S, Sainkar RS, Khan IM, et al. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their immobilization in the mycelial matrix: a novel biological approach to nanoparticle synthesis. Nano Lett. 2001;1(10):515–9.10.1021/nl0155274Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Chugh D, Viswamalya SV, Das B. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with algae and the importance of capping agents in the process. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19:126.10.1186/s43141-021-00228-wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Niknejad F, Nabili M, Daie Ghazvini R, Moazeni M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: advantages of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae model. Curr Med Mycol. 2015;1(3):17–24. 10.18869/acadpub.cmm.1.3.17.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Torabfam M, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H. Microwave-enhanced silver nanoparticle synthesis using chitosan biopolymer: optimization of the process conditions and evaluation of their characteristics. Green Process Synth. 2018;7:530–7. 10.1515/gps-2017-0139.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Varadharaj V, Ramaswamy A, Sakthivel R, Subbaiya R, Barabadi H, Chandrasekaran M, et al. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activity of green synthesized starch nanoparticles: an in vitro study. J Clust Sci. 2020;31:1257–66. 10.1007/s10876-019-01732-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Rafique M, Sadaf I, Rafique MS, Tahir MB. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;45(7):1272–91.10.1080/21691401.2016.1241792Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Abdelghany TM, Al-Rajhi AMH, Al Abboud MA, Alawlaqi MM, Magdah AG, Helmy EAM, et al. Recent advances in green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications: about future directions. A review. BioNanoScience. 2018;8:5–16.10.1007/s12668-017-0413-3Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Tarannum N, Divya, Gautam YK. Facile green synthesis and applications of silver nanoparticles: a state-of-the-art review. RSC Adv. 2019;9:34926–48.10.1039/C9RA04164HSuche in Google Scholar

[37] Vanlalveni C, Lallianrawna S, Biswas A, Selvaraj M, Changmai B, Rokhum SL. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: a review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021;11:2804–37.10.1039/D0RA09941DSuche in Google Scholar

[38] Zargar M, Hamid AA, Bakar FA, Shamsudin MN, Shameli K, Jahanshiri F, et al. Green synthesis and antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles using Vitex negundo L. Molecules. 2011;16:6667–76.10.3390/molecules16086667Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Masurkar SA, Chaudhari PR, Shidore VB, Kamble SP. Rapid biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cymbopogan citratus (lemongrass) and its antimicrobial activity. Nano-Micro Lett. 2011;3:189–94.10.1007/BF03353671Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Ahmadi O, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H, Jodeiri N. Eco-friendly microwave-enhanced green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera leaf extract and their physico-chemical and antibacterial studies. Green Process Synth. 2018;7:231–40. 10.1515/gps-2017-0039.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Ghanbari S, Vaghari H, Sayyar Z, Adibpour M, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H. Autoclave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using A. fumigatus mycelia extract and the evaluation of their physico-chemical properties and antibacterial activity. Green Process Synth. 2018;7:217–24. 10.1515/gps-2017-0062.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Eshghi M, Kamali-Shojaei A, Vaghari H, Najian Y, Mohebian Z, Ahmadi O, et al. Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties. Green Process Synth. 2021;10:606–13. 10.1515/gps-2021-0062.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Rai M, Posten C. Green biosynthesis of nanoparticles mechanisms and applications. Printed and Bound in the UK by Berforts Information Press Ltd; 2013.10.1079/9781780642239.0000Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Chernenko TV, Ul’chenko NT, Glushenkova AI, Redzhepov D. Chemical investigation of Callisia fragrans. Chem Nat Compd. 2007;43:253–5.10.1007/s10600-007-0098-xSuche in Google Scholar

[45] Olennikov DN, Nazarova AV, Rokhin AV, Ibragimov TA, Zilfikarov IN. Chemical composition of Callisia fragrans juice. II. Carbohydrates. Chem Nat Compd. 2010;46:273–5.10.1007/s10600-010-9585-6Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Sohafy SM, Nassra RA, D’Urso G, Piacente S, Sallam SM. Chemical profiling and biological screening with potential anti-inflammatory activity of Callisia fragrans grown in Egypt. Nat Product Res. 2021;35:5521–4.10.1080/14786419.2020.1791113Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Soni A, Sosa S. Phytochemical analysis and free radical scavenging potential of herbal and medicinal plant extracts. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;2(4):22–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Nagar N, Jain S, Kachhawah P, Devra V. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles via green route. Korean J Chem Eng. 2016;33(10):2990–7.10.1007/s11814-016-0156-9Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Mittal AK, Kaler A, Banerjee UC. Free radical scavenging and antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized from flower extract of Rhododendron dauricum. Nano Biomed Eng. 2012;4(3):118–24.10.5101/nbe.v4i3.p118-124Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Dubey SP, Lahtinen M, Sillanpää M. Tansy fruit mediated greener synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles. Process Biochem. 2010;45:1065–71.10.1016/j.procbio.2010.03.024Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Heydari R, Rashidipour M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using extract of oak fruit hull (Jaft): synthesis and in vitro cytotoxic effect on MCF-7cells. Int J Breast Cancer. 2015;6:1–6. 10.1155/2015/846743.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Iravani S, Zolfaghari B. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pinus eldarica bark extract. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:5. Article ID 639725. 10.1155/2013/639725.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Melkamu WW, Bitew TL. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F.Gmel plant leaf extract and their antibacterial and anti-oxidant activities. Heliyon. 2021;7:e08459.10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08459Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Heydari R. Biological applications of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles through the utilization of plant extracts. Herb Med J. 2017;2(2):87–95.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Sarsar V, Selwal KM, Selwel KK. Significant parameters in the optimization of biosysnthesis o silver nanoparticles using Psidium guajava leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against human pathogenic bacteria. Int J Adv Pharma Sci. 2014;5(1):1769–75.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Nidhin M, Indumathy R, Sreeram JK, Nair BU. Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles of narrow size distribution on polysaccharide templates. Bull Mater Sci. 2008;31(1):93–6.10.1007/s12034-008-0016-2Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Ullah I, Khalil AT, Ali M, Iqbal J, Ali W, Alarifi S, et al. Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles induced apoptotic cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by generating reactive oxygen species and activating caspase 3 and 9 enzyme activities. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:1215395.10.1155/2020/1215395Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Mashwani ZR, Khan MA, Khan T. Applications of plant terpenoids in the synthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;234:132–41.10.1016/j.cis.2016.04.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Mostafavi E, Zarepour A, Barabadi H, Zarrabi A, Truong BL, Medina-Cruz D. Antineoplastic activity of biogenic silver and gold nanoparticles to combat leukemia: beginning a new era in cancer theragnostic. Biotechnol Rep. 2022;34:e00714.10.1016/j.btre.2022.e00714Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Virmani I, Sasi C, Priyadarshini E, Kumar R, Sharma KS, Singh PG, et al. Comparative anticancer potential of biologically and chemically synthesized gold nanoparticles. J Clust Sci. 2020;31:867–76. 10.1007/s10876-019-01695-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Barabadi H, Vahidi H, Mahjoub AM, Kosar Z, Kamali DK, Ponmurugan K, et al. Emerging antineoplastic gold nanomaterials for cervical cancer therapeutics: a systematic review. J Clust Sci. 2020;31:1173–84. 10.1007/s10876-019-01733-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Alahmad A, Feldhoff A, Bigall NC, Rusch P, Scheper T. Hypericum perforatum L.-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles exhibiting antioxidant and anticancer activities. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:487.10.3390/nano11020487Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Patra JK, Das G, Shin HS. Facile green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pisum sativum L. outer peel aqueous extract and its antidiabetic, cytotoxicity, antioxidant, and antibacterial activity. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:6679–90.10.2147/IJN.S212614Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Hashemi Z, Mizwari ZM, Mohammadi-Aghdam S, Mortazavi-Derazkola S, Ebrahimzadeh MA. Sustainable green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Sambucus ebulus phenolic extract (AgNPs@SEE): optimization and assessment of photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange and their in vitro antibacterial and anticancer activity. Arab J Chem. 2022;15:103525.10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103525Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Almeida PDO, Boleti APA, Rüdiger AL, Lourenço GA, Veiga Junior VF, Lima ES. Anti-inflammatory activity of triterpenes isolated from protium paniculatum oil-resins. Evid-Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;10:Article ID 293768.10.1155/2015/293768Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Ferreira RGS, Silva Júnior WF, Veiga Junior VF, Lima AAN, Lima ES. Physicochemical characterization and biological activities of the triterpenic mixture α, β-amyrenone. Molecules. 2017;22:298. 10.3390/molecules22020298.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives