Abstract

The selective leaching method presents a new and innovative approach for the enrichment of low-grade phosphate raw materials. The use of acetic acid as a reagent in the leaching process allows for the selective dissolution of carbonates, potassium-, and aluminum-containing compounds, offering a promising solution for the improvement of the recovery rates of valuable phosphorus compounds. This study presents the results of research on the selective leaching of carbonates from low-grade phosphate raw materials and evaluation of its efficiency using a combination of SEM, energy-dispersion and chemical analysis, X-ray diffraction, differential thermal, IR-Fourier spectroscopic, and mineralogical analysis techniques. The results showed an increase in the content of phosphorus(v) oxide from 14% to 22% through the selective leaching process. The enriched phosphate raw materials were also found to be suitable for the production of phosphorus-containing products. This research highlights the potential of the selective leaching method to overcome the challenges faced in the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites and provide a more efficient and sustainable solution for the industry.

1 Introduction

Phosphorus is one of the most abundant elements on the Earth and plays an important role in geological and biological processes. In terms of mineralogy, phosphorites are complex and varied in structure. The element phosphorus is an integral part of all biological/physiological processes in plants and animals. In addition, phosphate minerals are a valuable natural resource widely used as agricultural fertilizers [1].

Phosphorites occur in various geological environments and in many complex mineralogical structures. Representatives of the apatite group predominate in igneous and metamorphic rocks, in particular, phosphorites of the fluorapatite type [2]. Depending on the form of formation, phosphorites are divided into two different genetic groups: marine and terrestrial. Marine phosphorites, in turn, consist of a lithologic classification as follows: fine-grained, granular, nodular, and shell. The assignment of such names is not accidental, since each of them depends on the characteristics of the geological formation, location at stratigraphic levels, and geographical location [3].

One of the large deposits of microgranular phosphorites is the Karatau phosphorite basin in Kazakhstan, which serves as the main source of raw materials for the production of phosphorus compounds in the country. The Karatau phosphorite basin is located in the northeastern massif of the Malyi Karatau Range in South Kazakhstan and extends in a northwestern direction for about 120 km, 25 km wide.

The reserves of phosphorite rocks in the Karatau basin, in terms of P2O5, are about 700 million tons [4]. The Karatau Phosphorite Basin, with a significant share of the world’s phosphate reserves, is the leading exporter of phosphates and their derivatives. Most of the phosphorite reserves are sedimentary rocks with a significant amount of carbonate minerals.

In the studies of Bushinskiy [5], the bulk of the Karatau phosphorites is limited by a group of terrigenous–siliceous–carbonate formations. Within this group, two types of phosphorite formations can be named: shale–silica–dolomite and quartzite–shale–limestone (here quartzites are understood as quartz sandstone). Most of the phosphorite deposits of Karatau are representatives of shale–siliceous–dolomite formations. Also here, the phosphorite lining is laid with clay and siliceous–argillaceous shales and covered with the thickness of the Tamdinsky dolomites. From this it can be seen that the silicic–dolomite formation contains rich deposits of phosphorites. They arose under the conditions of medium and small deposits and phosphate occurrences.

Currently, Kazphosphate LLP is operating the main ordinary deposits of the Karatau phosphorite basin. At the mining and processing complex “Karatau,” the extraction of the necessary raw materials for the production of yellow phosphorus and wet-process phosphoric acid (WPA) by an open land method from the Kokzhon, Koksu, and Zhanatas deposits is carried out, followed by mechanical enrichment [6]. The reserves of deposits of this raw material are depleted, and the exploration and exploitation of new deposits require significant financial sources. Also, in the process of extraction and subsequent processing, the amount of waste containing a phosphate useful part increases. The disposal of these wastes is not well established. The use of low-grade phosphorite deposits in terms of P2O5, is also not possible, since it requires scientific research and technological solutions for their enrichment.

2 Literature review

Low-grade phosphorites, which contain low concentrations of valuable phosphorus compounds, are a major challenge for the phosphate processing industry. The conventional methods for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites, such as flotation and roasting, often result in low recovery rates and significant environmental impacts. To address this challenge, the development of new and innovative methods for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites is needed.

The flotation enrichment method, commonly used in phosphate processing plants, has limitations that hinder its efficiency and effectiveness. One major limitation is the high cost of flotation reagents, which increases the operational expenses of processing plants. The method also generates significant waste, adding to the environmental impact of phosphate processing [7].

Additionally, the high dispersibility of phosphate grains during the flotation process reduces the recovery rates of valuable phosphorus compounds. The flotation properties of calcium and magnesium carbonates, commonly found in the composition of low-grade phosphorites, are similar to those of the phosphate, making it difficult to separate the two components. Contamination of the concentrate with aluminum and iron oxides also limits the efficiency of the flotation process.

Finally, the low volume of products produced and the low content of useful substances in the concentrate, coupled with the complex hardware and technological design required, further highlight the disadvantages of the flotation enrichment method.

Abbes et al. [8] and Rizk [9] identified several disadvantages of the calcination method: at high temperatures, the solubility and reactivity of phosphorite decrease. That is, the burnt phosphorite concentrate requires a longer retention period so that it again acquires the solubility of simple phosphorite. This condition may be associated with physical and chemical changes in phosphate rocks at high temperatures during the heat treatment. Thus, it was found that the solubility of chlorine in phosphorous raw materials decreases after calcination [10]. When calcining carbonates/dolomites contained in phosphorites, their complete decomposition should occur. This is because the products formed during their decomposition prevent the use of phosphorite concentrate in the process of subsequent sulfuric acid decomposition. Therefore, it is necessary to extend the calcination time at 900–950°C or increase the temperature. This, in turn, leads to subsidence and melting of the phosphate part [11]. Also, magnesium oxide formed during the decomposition of dolomite during high-temperature treatment can turn into an insoluble compound of magnesium hydroxide [12]. It is known that an excessive amount of magnesium compounds prevents the production of WPA and fertilizers.

The selective leaching method presents a promising solution for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites. This method uses an acid reagent to selectively dissolve carbonates from low-grade phosphorites, resulting in an enriched concentrate with improved recovery rates of valuable phosphorus compounds. Despite the potential of the selective leaching method, there is limited research on its application for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites.

The efficiency of dissolving carbonates is high, low cost, technologically simple design, and the possibility of reuse of the used acid demonstrate the advantages of this method. According to the literature review, organic acids such as formic, acetic, lactic, succinic, citric and maleic acids have been used in many studies. The main effectiveness of all acids lies in the fact that they have the property of selective leaching of carbonate compounds in the composition of phosphorite. Among other carboxylic acids used in the enrichment process, there are studies of the effect of lactic and succinic acids on low-grade phosphorites [13,14]. At certain optimal parameters, such as 45°C, the ratio of solid/liquid is equal to 1:7, the acid concentration is 8%, and the content of phosphoric anhydride increased to 33–34%.

The use of acetic acid in the selective leaching of carbonates from low-grade phosphorites has received growing attention in recent years. As an organic monocarboxylic acid, acetic acid offers several advantages for the enrichment process, including its widespread availability and relatively low cost in the market. The property of acetic acid to selectively dissolve carbonates from low-grade phosphorites makes it a promising reagent for the improvement of the recovery rates of valuable phosphorus compounds.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of the selective leaching method for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites and to explore new areas for improvement. The results of this study will provide a comprehensive evaluation of the selective leaching method and highlight new areas for exploration in the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites.

3 Materials and methods

Studies on the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites consisted of the following stages: preparation of raw materials, acid leaching, analysis of the composition, and the structure of the products obtained.

3.1 Description of laboratory equipment and acetic acid

A laboratory ball mill MSHL-1 was used to prepare the raw materials. The drum in the mill is filled with balls made of durable steel material and current raw materials. When the drum rotates, the material is crushed as a result of the impact action of the balls. A vibro-sieve of the brand “Analysette” was used to sift the crushed raw materials.

For acid leaching of crushed low-grade phosphorites, a laboratory installation has been designed with an attached magnetic stirrer of the IKA C-MAG HS 7 brand with a fully controlled temperature regime and mixing frequency, and a laboratory ionomer I-160MI was used to control the pH value of the pulp formed when mixing acid and raw materials.

In this regard, acetic acid produced at the JSC Nevinnomyssky Azot plant in accordance with the regulatory requirements of TC 9182-086-00203766-2005 was used as the selected reagent for the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites.

3.2 Instrumental methods of analysis

The following installations were used to carry out instrumental physicochemical analysis methods:

The JEOL JSM-6490 LV Electronic Scanning Microscope (Japan) makes it possible to determine the element-weight composition of the sample under study by obtaining micrographs of various materials of inorganic nature and energy dispersion analysis.

The IR-Prestige 21 Infrared Fourier Spectrometer (Japan) is a modern device with a single-beam optical system equipped with a quick-release Michelson interferometer. The spectral range includes wavelengths of 7,800–350 cm−1. It is provided with the IRsolution software package for processing the received analytical materials.

The NEOPHOT-21 metallographic microscope (Germany) was used to determine the mineralogical structure of low-grade phosphorites. It is equipped with computer software for processing the received micrographs. For the preliminary preparation of raw materials in determining the mineralogical structure, installations of the STRUERS brand (Denmark) were used.

The Q-1500 D derivatograph (Hungary) was used for differential thermal analysis of materials. It allows one to study the heat resistance of various materials and the processes of hydration and dehydration.

The phase structure of the materials was determined using a Bruker D8 diffractometer (Germany). In addition, DiffracPlusSearch was used to process the data obtained for phase detection and a database of PDF2 radiographs consisting of more than 450,000 known compounds.

Thermodynamic analysis of the processes of enrichment of low-grade phosphorites with acetic acid was carried out on a modern, multifunctional software package HSC 9.3, based on the principle of maximum entropy and minimization of Gibbs energy. For heterogeneous reactions, the specified module “Reaction Equations” is used to calculate the change in the values of enthalpy ΔH, entropy ΔS, and Gibbs free energy ΔG in accordance with the following equations [15]:

where s i is the stoichiometric coefficients.

The possibilities of the online application “Statistics” were used for the statistical processing of the experimental data obtained. Differences were analyzed via a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3.3 Description of the experimental part and calculation of the main parameters of the process

Crushed raw materials were used for experimental studies. The temperature range of the process was 20–40°C and the enrichment time was 15–45 min. The liquid/solid ratio = 3:1 was determined by calculating the amount of acetic acid required for the complete decomposition of CaCO3, MgCO3, K2O, and Al2O3 compounds in phosphate raw materials and the volume of water required for dilution, based on its solubility in water (40 g·L−1). Also, the density d = 1.030 for dilute acetic acid, the pH value was 2.33, and pK a = 6.2 × 10−2 mol·L−1. Based on the pH values of the dilute acid and the resulting pulp, the concentration (C, mol·L−1) was calculated using the expression [H+] = 10−pH. Then, using these values, the level of consumption of acetic acid for the enrichment process (α) was calculated by the following equation:

where C 1 is the concentration of dilute acetic acid (mol·L·1) and C 2 is the pulp concentration (mol·L−1).

Based on this value, the reaction rate is calculated using the following equation:

where ∆n is the change in the number of moles of starting substances (mol), V is the volume of the mixture (L), and ∆τ is the time (min).

The efficiency of the process under study was determined with P2O5 (%). The degree of increase in P2O5 (%) is calculated by the following equation:

where B is the weight of the enriched raw materials (g), b the amount of P2O5 in the enriched raw materials (%), P is the weight of the initial raw material (g), and p is the amount of P2O5 in the initial raw material (%).

The concept of “mineral efficiency” was used as the degree of completeness of the increase in the useful component in the concentrate, the criterion for improving the enrichment process [16]. The determination of this indicator is based on the calculation of efficiency criteria using analytical methods for the yield of enrichment products and the amount of the corresponding component contained in them according to the following equation:

where P2O5 DI is the degree of increase in P2O5 (%), A is the amount of P2O5 in the initial raw material (%), and B is the amount of P2O5 in the enriched raw materials (%).

The degree of concentration (K) indicator was also calculated, which determines how much the content of the useful component in the concentrate increased compared to its content in the initial material [16]. The useful component in the concentrate is defined as the ratio of the amount (B) of P2O5 in the enriched raw material to the amount (A) of P2O5 in the initial raw material according to the following equation:

where A is the amount of P2O5 in the initial raw material (%) and B is the amount of P2O5 in the enriched raw materials (%).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Material composition of low-grade phosphate raw materials

The chemical analysis of low-grade phosphorites is presented in Table 1.

Chemical composition of low-grade phosphorites

| P2O5 | CaO | MgO | K2O | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.51% | 31.43% | 2.08% | 0.39% | 1.16% | 0.51% | 20.08% |

Based on chemical analysis, it was found that the content of phosphoric pentoxide in phosphate raw materials was 14.51%, and those of calcium and magnesium oxides were 31.43% and 2.08%, respectively. The content of aluminum oxide was 1.16% and that of iron oxide was 0.51%.

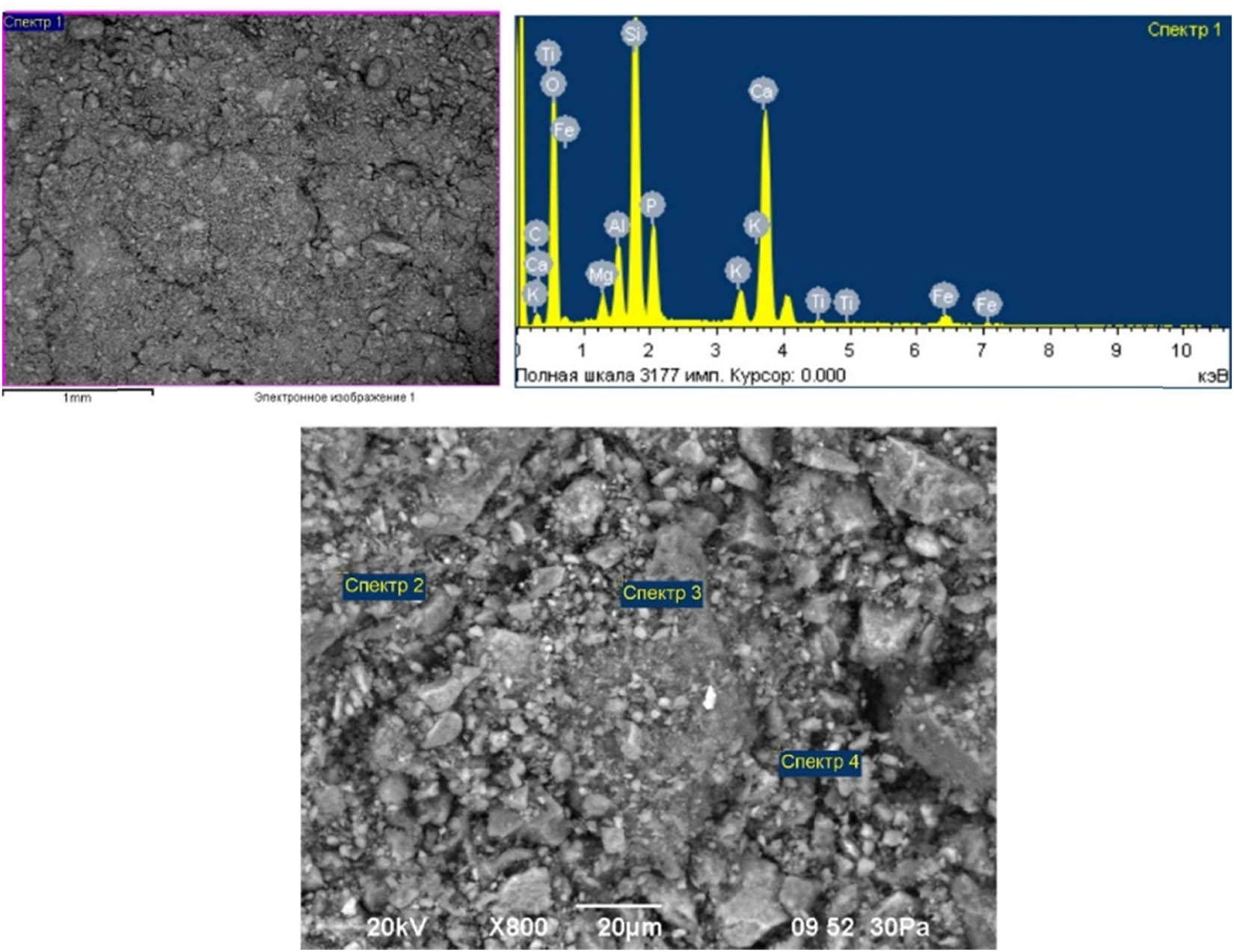

Micrographs of phosphorites were magnified 40 and 800 times (acceleration voltage: 20 kV), and the element-weight compositions obtained from four different spectra using energy-dispersion analysis are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Elemental-weight composition of low-grade phosphorites

| Element | Spectrum 1 | Spectrum 2 | Spectrum 3 | Spectrum 4 | On average (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight compos. (%) | As oxides (%) | Weight compos. (%) | As oxides (%) | Weight compos. (%) | As oxides (%) | Weight compos. (%) | As oxides (%) | Weight compos. (%) | As oxides (%) | |

| C | 8.91 | — | 5.76 | — | 7.13 | — | 6.75 | — | 7.13 | — |

| O | 48.66 | — | 54.17 | — | 54.40 | — | 49.61 | — | 51.71 | — |

| F | — | — | — | — | 1.62 | — | 0.54 | — | 1.08 | — |

| Mg | 2.55 | 4.22 | 1.43 | 2.37 | 1.89 | 3.13 | 2.01 | 3.33 | 1.97 | 3.26 |

| Al | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.34 | 1.07 | 2.02 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.59 | 1.11 |

| Si | 8.65 | 18.50 | 9.28 | 19.84 | 8.91 | 19.05 | 8.73 | 18.67 | 8.89 | 19.01 |

| P | 6.47 | 14.82 | 7.13 | 16.33 | 5.61 | 12.85 | 4.78 | 10.95 | 5.99 | 13.72 |

| K | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.43 |

| Ca | 23.66 | 33.10 | 20.76 | 29.04 | 18.17 | 25.41 | 26.40 | 36.93 | 22.24 | 31.11 |

| Fe | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 1.04 | 0.54 | 0.77 |

| Ti | 0.03 | 0.05 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.03 | 0.05 |

Micrographs of low-grade phosphorites, and the results of energy dispersion analysis.

From the above data, it is evident that phosphorus, silicon, and calcium oxides are the main compounds in the composition of phosphate raw materials. So, if the proportion of silicon oxide is, on average, 19.01%, then the content of calcium oxides is 31.11%. The share of the main useful component, phosphoric anhydride, is about 13.72%, and this value determines that the raw materials of this deposit can be classified as low-grade phosphorites. In the SEM image, the structure of the phosphorite sample appears as a complex and heterogeneous mix of different minerals. The bright regions in the image are predominantly composed of phosphate minerals, such as apatite, while the darker regions contain silicates, carbonates, and oxides. The surface of the sample is seen to be rough and irregular, with numerous small protrusions and indentations, suggesting a complex history of formation and alteration.

The proportion of magnesium and potassium oxides is 3.26% and 0.43%, respectively. The proportion of aluminum and iron oxide compounds ranges from 1.11% to 0.77%. Fluorine was detected only in spectra 3 and 4, and its content is, on average, 1.08%. In the same situation, titanium compounds observed only in spectrum 1 are 0.03%.

The results of IR spectroscopic studies of low-grade phosphorites are presented in Figure 2 and Table 3.

IR spectra of low-grade phosphorites.

Peaks of IR spectra

| Phase bonding | Peak | Intensity | Corr. intensity | Base (H) | Base (L) | Area | Corr. area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si–O–Si | 455.20 | 90.145 | 4.472 | 462.92 | 447.49 | 0.595 | 0.159 |

| Si–O–Si | 528.50 | 93.260 | 4.651 | 543.93 | 513.07 | 0.601 | 0.338 |

| P–F | 559.36 | 91.907 | 2.136 | 567.07 | 547.78 | 0.559 | 0.106 |

| P–F | 574.79 | 91.353 | 1.345 | 586.36 | 567.07 | 0.711 | 0.076 |

| Al | 601.79 | 87.874 | 7.127 | 624.94 | 590.22 | 1.235 | 0.540 |

| Al | 694.37 | 95.813 | 1.320 | 705.95 | 682.80 | 0.359 | 0.073 |

| Al | 729.09 | 93.787 | 2.912 | 740.67 | 709.80 | 0.616 | 0.158 |

| Al | 779.21 | 92.390 | 1.672 | 786.96 | 744.52 | 0.949 | 0.087 |

| Si–O–Si | 798.53 | 92.226 | 2.389 | 825.53 | 786.96 | 0.905 | 0.112 |

| Si–O–Si | 879.54 | 86.966 | 8.850 | 898.83 | 829.39 | 2.152 | 1.029 |

| Si–O–Si | 964.41 | 88.310 | 0.410 | 968.27 | 902.69 | 2.205 | 0.007 |

| Si–O–Si | 1,033.85 | 76.294 | 11.224 | 1,083.99 | 972.12 | 9.942 | 3.517 |

| Si–O–Si | 1,091.71 | 86.493 | 0.941 | 1,246.02 | 1,083.99 | 4.237 | −1.281 |

|

|

1,427.32 | 89.387 | 1.358 | 1,442.75 | 1,288.45 | 3.823 | 0.210 |

|

|

1,450.47 | 89.854 | 0.359 | 1,589.34 | 1,446.61 | 2.951 | −0.456 |

| Organic matters | 2,927.94 | 99.586 | 0.840 | 2,951.09 | 2,885.51 | −0.015 | 0.121 |

An infrared spectroscopic analysis of the low-grade phosphorites was performed to identify the chemical functional groups present in the sample. The spectral peaks at 400–500 and 800–960 cm−1 were found to be characteristic of Si–O–Si bonds in the phosphorite frame structure. On the other hand, peaks at 550–570 cm−1 indicate the presence of P–F compounds. The presence of aluminate compounds is indicated by spectral peaks in the range of 600–780 cm−1, while the layered and chain structure of compounds with Si–O–Si bonds is indicated by peaks at 1,000–1,060 cm−1.

In addition, spectral peaks in the range of 1,435–1,450 cm−1 were found to be characteristic of crystals containing

The X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out to determine the phase structures of phosphate raw materials, and the results are shown in Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction peaks of low-grade phosphorites.

X-ray diffraction studies conducted on low-grade phosphorites have revealed the presence of various minerals in their composition. Fluorapatite, Ca5(PO4)3F, was found to be the dominant mineral, constituting approximately 48.76% of the total composition. Quartz, SiO2, was also identified as a significant component, making up approximately 22.11% of the composition.

In addition, the studies showed the presence of dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2, and calcite, CaCO3, in the composition, with proportions of 18.25% and 10.87%, respectively. These findings demonstrate the complexity of the mineral composition of low-grade phosphorites, highlighting the need for efficient methods to selectively extract valuable phosphorus compounds.

The differential thermal analysis was performed on a Q-1,500 D derivatograph with a maximum heating temperature of 1,000°C, and the results are presented in Figure 4.

Derivatogram of low-grade phosphorites.

The absorption water contained in the test sample is characterized in the temperature range from 90°C to 170°C by endoeffects. When the heating temperature increases to 200°C and above, the crystal transition of quartz occurs. Dehydration of clay compounds occurs in the temperature range of 520–570°C, and at temperature values of 700°C and above, carbonate compounds decompose. Exothermic effects in the temperature range of 940–980°C lead to crystallization of aluminate compounds [21]. According to the derivatogram, the duration of the analysis is 90 min, and there was a loss of 8.44% of the mass of the raw material.

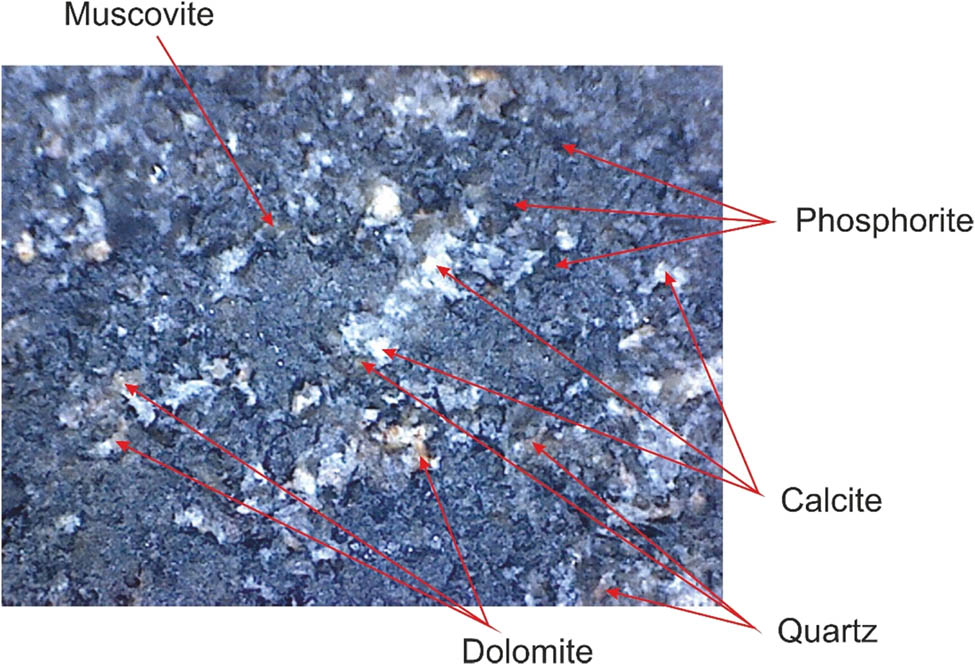

The initial processing of the low-grade phosphorite sample was performed using a Struers device, followed by an examination of the sample micrograph using a metallographic microscope. The obtained results are depicted in Figure 5.

Mineralogical composition of low-grade phosphorites.

The analysis of the studied sample revealed the presence of white-shiny calcite and yellowish dolomite minerals. These minerals are commonly found in sedimentary metamorphosed rocks and are difficult to distinguish due to their similar properties, such as three-sided perfect mineral fusion along the rhombohedron. However, dolomite is harder than calcite and has a higher density [22,23,24]. The results also showed the presence of quartz, a trigonal mineral with a refractive index of 1.544, a hardness of 7, and a density of 2.6 g·cm−3. Quartz is commonly found in sedimentary rocks in combination with dolomites and has a cellular fracture and no mineral integration property [25]. The SEM analysis also revealed the presence of aluminosilicate minerals, such as muscovite, on a small scale, with an elastic and monoclinic syngonic classification, a refractive index of 1.6, and layered and lamellar crystal types [26].

4.2 Chemistry and thermodynamic analysis of the selective leaching process

The reactions of the interaction of phosphate raw materials and the compounds contained therein with acetic acid take place according to the following equations:

The reaction in Eq. 9 of fluorapatite and acetic acid proceeds with the release of calcium acetate, phosphoric acid, and hydrogen fluoride, which pass into the gas phase. As a result of the interaction of calcium and magnesium carbonates with acetic acid, an exchange reaction occurs, where acetate salts, water, and carbon dioxide are released as a product. Since potassium and aluminate compounds are present in the phosphate raw materials in the form of nepheline, their interaction with acetic acid occurs with the formation of potassium acetate and aluminum products. The proposed chemical reactions are based on known data.

In the process of selective leaching under the action of acetic acid, carbonate, potassium, and aluminate compounds contained in phosphate raw materials are involved. They are present in the solution in the form of acetate salts during the exchange reaction, and in the insoluble part of the pulp, the phosphate part, compounds of silicon, iron, and calcium fluoride remain. Acetic acid, due to its chemical properties, is a monocarboxylic acid, belongs to the number of proton polar solvents. This, in turn, is based on the fact that acetic acid contains a hydrogen ion capable of splitting in the form of a proton H+; acetic acid has a pK a = 1.8 × 10−5. In other studies [27,28,29,30,31,32], these data have been substantiated and presented. The results of the thermodynamic analysis of these chemical reactions and their mechanisms are presented in Table 4.

Thermodynamic analysis of the selective leaching process

| Reaction no. | Gibbs free energy ΔG (kcal) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | |

| (1) | 80.82 | 83.10 | 85.52 | 88.08 | 90.77 | 93.36 | 96.01 | 98.78 | 101.67 | 104.68 | 107.8 |

| (2) | −0.85 | −0.79 | −0.70 | −0.59 | −0.46 | −0.30 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| (3) | −8.25 | −7.79 | −7.40 | −7.06 | −6.75 | −6.48 | −6.23 | −6.00 | −5.80 | −5.61 | −5.44 |

| (4) | −100.90 | −100.90 | −100.92 | −100.96 | −101.01 | −101.07 | −101.13 | −101.20 | −101.27 | −101.34 | −101.41 |

| (5) | −14.05 | −10.45 | −7.01 | −3.68 | −0.45 | 2.70 | 5.79 | 8.84 | 11.83 | 14.79 | 17.70 |

| (6) | 37.60 | 40.04 | 42.47 | 45.01 | 47.62 | 50.30 | 53.05 | 55.87 | 58.76 | 61.72 | 64.74 |

Based on the above, it can be said that the reaction of fluorapatite and acetic acid does not proceed from a thermodynamic point of view. Reactions 10 and 11, where interactions of carbonates with acid are described, occur at low temperatures; increase in temperature leads to a decrease in the Gibbs energy. The decomposition of potassium and aluminum oxides in acetic acid can be explained by the fact that these compounds are present in the phosphate raw materials in the form of a nepheline mineral. Nepheline is a mineral, sodium/potassium aluminosilicate (Na,K)AlSiO4 [26], formed in rocks. In studies conducted by the Academy of Sciences of the USSR [33], it was found that nepheline is partially soluble in acetic acid. Thermodynamic probability of the interaction of calcium and magnesium carbonates, potassium, and aluminum oxides with acetic acid in phosphate raw materials occurs according to the following scheme: CaCO3 > MgCO3 > Al2O3 > K2O. Obviously, this information complements the data on the thermodynamic probability of these reactions. The reaction of iron oxide with acetic acid also has positive Gibbs free energy values and therefore does not proceed.

4.3 Experimental data of the selective leaching process

The results of experimental studies on the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites with acetic acid are presented in Tables 5 and 6 and in Figure 6.

Experimental data on the enrichment of low-grade phosphorites with acetic acid

| Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | pH | C (mol·L−1) | ν (mol·L−1·min−1) | A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 10 | 3.452 | 0.00035318 | 0.18300 | 92.44 |

| 20 | 3.487 | 0.00032583 | 0.09208 | 93.03 | |

| 30 | 3.515 | 0.00030549 | 0.06167 | 93.46 | |

| 40 | 3.528 | 0.00029648 | 0.04635 | 93.66 | |

| 50 | 3.533 | 0.00029308 | 0.03711 | 93.73 | |

| 30 | 10 | 3.538 | 0.00028973 | 0.18569 | 93.80 |

| 20 | 3.540 | 0.00028840 | 0.09287 | 93.83 | |

| 30 | 3.542 | 0.00028707 | 0.06193 | 93.86 | |

| 40 | 3.544 | 0.00028575 | 0.04646 | 93.89 | |

| 50 | 3.545 | 0.00028510 | 0.03717 | 93.90 | |

| 40 | 10 | 3.567 | 0.00027101 | 0.18648 | 94.20 |

| 20 | 3.570 | 0.00026915 | 0.09328 | 94.24 | |

| 30 | 3.584 | 0.00026061 | 0.06230 | 94.42 | |

| 40 | 3.597 | 0.00025292 | 0.04681 | 94.59 | |

| 50 | 3.611 | 0.00024490 | 0.03751 | 94.76 |

Technological indicators of the process of enrichment of low-grade phosphorites with acetic acid

| Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | P2O5 (%) | P2O5 passed into solution (%) | E (%) | K | P2O5 DI (%) | Standard deviations for P2O5 DI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 10 | 18.54 | — | 54.16 | 1.26 | 56.71 | 0.86 |

| 20 | 18.86 | — | 54.96 | 1.28 | 57.77 | 1.02 | |

| 30 | 19.28 | — | 55.50 | 1.31 | 58.64 | 0.74 | |

| 40 | 19.13 | — | 55.42 | 1.29 | 58.45 | 1.04 | |

| 50 | 19.04 | — | 55.36 | 1.29 | 58.32 | 1.10 | |

| 30 | 10 | 20.16 | — | 59.48 | 1.37 | 63.54 | 0.39 |

| 20 | 20.73 | — | 59.79 | 1.40 | 64.33 | 0.91 | |

| 30 | 20.86 | — | 60.35 | 1.41 | 65.04 | 0.88 | |

| 40 | 20.82 | — | 60.53 | 1.41 | 65.20 | 0.71 | |

| 50 | 20.72 | 0.19 | 60.52 | 1.40 | 65.11 | 0.94 | |

| 40 | 10 | 21.43 | 0.37 | 63.30 | 1.45 | 68.71 | 0.43 |

| 20 | 21.85 | 0.41 | 63.28 | 1.48 | 69.06 | 0.97 | |

| 30 | 22.11 | 0.34 | 64.68 | 1.50 | 70.82 | 1.08 | |

| 40 | 22.21 | 0.37 | 65.27 | 1.51 | 71.56 | 0.69 | |

| 50 | 22.18 | 0.32 | 64.48 | 1.50 | 70.67 | 0.83 |

Acetic acid enrichment of low-grade phosphorites: (a) dependence of the increase in P2O5 on time; and (b) dependence of the acetic acid consumption level on time.

It was found that an increase in the reaction temperature during the enrichment of phosphorites affects the increase in the reaction rate and the level of acetic acid (α) consumption. Thus, with increasing temperature and time, the indicators of P2O5 and P2O5DI also increase. However, at 40°C and 20–30 min, the amount of phosphorus(v) oxide increases and reaches a maximum value at 40 min; subsequently, this indicator decreases or remains unchanged at 50 min. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the establishment of equilibrium in these values or calcium (magnesium) acetates formed as a result of the interaction of dolomite and acetic acid inside the pulp inhibit the further course of the process. To verify this fact, the Pilling–Bedworth ratio can be used [34], according to the following equation:

where 2 is the number of calcium acetate molecules;

The value of PBratio is calculated to be 1.24 and, accordingly, it indicates that the acetate salts formed during the reaction have a significant diffusion resistance to the process under study, since this value lies within 2.5 ≥ PBratio ≥ 1.

The revealed optimal regime parameters allow the enriching of low-grade phosphorites with acetic acid. In other studies on the enrichment of phosphorites [13,27,35,36,37], the duration of the acetic acid enrichment process is 40–60 min, and the process temperature is studied in the range of 20–70°C, with a process duration of 40 min; at a temperature of more than 40°C, the indicators such as the amount of P2O5 and the output remain unchanged. The data obtained coincide with the data of studies on the enrichment of phosphorites and indicate the uniformity of the studies carried out.

4.4 Physico-chemical characteristics of enriched raw materials and assessment of their suitability for phosphorus production

This section presents the results of a study of the physicochemical properties of concentrates obtained during the enrichment of low-grade phosphate raw materials with acetic acid, as well as data on their suitability for the production of yellow phosphorus and phosphorus-containing fertilizers. The results of the chemical analysis of the enriched concentrate are presented in Table 7.

Chemical composition of enriched raw materials

| P2O5 | CaO | MgO | K2O | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22.19% | 32.40% | 0.19% | 0.08% | 0.07% | 1.76% | 33.05% |

It can be seen from the table data that when the content of the main compounds in the composition of the enriched raw materials is compared with the results of the primary chemical analysis, a significant increase in the content of phosphoric pentoxide is observed in the enriched concentrates. Also, a decrease in the amount of magnesium and aluminum oxides indicates the course of the enrichment process with acetic acid. The phase composition of the enriched phosphorite is shown in Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction peaks of enriched phosphorites.

The phase composition is represented by the main compounds in the form of fluorapatite and silicon dioxide. Compared with the phase composition of the feedstock, there are no carbonates or potassium- and aluminum-containing compounds in the final enriched product.

The phosphate raw materials required for the production of electrothermal phosphorus in Kazakhstan are regulated by “ST RK 2213-2012-Karatau crushed phosphate raw materials: Technical conditions,” and indicators of raw materials necessary for the production of phosphoric acid “ST RK 2211-2012-Karatau fine-grained phosphate raw materials: Technical conditions.” The raw materials required for the production of electrothermal phosphorus are designated as FKT (Phosphorite Karatau for heat treatment), and the raw materials subjected to acid treatment are designated as FKE (Phosphorite Karatau for extraction).

Technical requirements for phosphate raw materials are based on technical capabilities and economic optimality during its mechanical, thermal, or extraction processing. The indicator with the greatest importance in phosphate raw materials is the content of phosphoric pentoxide (P2O5). At the same time, the concentrate enriched with acetic acid, according to the indication of P2O5 in the composition, corresponds to the grades FKT-1 and FKE-2.1.

5 Conclusions

The results of the studies indicate that the process of selective leaching with acetic acid effectively removes all carbonate compounds from concentrates and the following:

The concentration of phosphoric pentoxide increased from 14% to 22%.

The leaching process takes 30–40 min and takes place at a temperature range of 30–40°C. However, an increase in temperature results in the solubilization of phosphoric anhydride.

Along with carbonates, potassium and aluminum compounds also contribute to the leaching process. These compounds are present in the form of nepheline in the structure of phosphorites and are partially dissolved by acetic acid. This has been confirmed through thermodynamic analysis and experimental studies.

By removing carbonates and nepheline, phosphate raw materials can be utilized in the production of phosphorus through electrothermal sublimation and in the production of phosphoric acid through sulfuric acid treatment. This will increase the economic efficiency of these industries as the heat treatment process can be abandoned and the consumption of sulfuric acid can be reduced.

This study provides valuable information for the improvement of the processing of low-grade phosphorites and the efficient utilization of phosphate resources.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP15473115.

-

Author contributions: Yerkebulan Raiymbekov: methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, funding acquisition; Perizat Abdurazova: visualization, investigation, writing – review and editing; Ulzhalgas Nazarbek: software, validation, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Dar SA, Khan KF, Birch WD. Sedimentary: Phosphates. In: Birch WD, editor. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 120–8.10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10509-3Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Mihailova IA, Bondarenko OB. Paleontology. 2nd edn. Moscow: MSU; 2006 [in Russ].Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Earle S. Physical geology. Nanaimo: Vancouver Island University; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Elkondieva GB. Karatauskij bassejn – krupnejshaja fosfatnaja syr’evaja baza Evrazii [in Russian: The Karatau basin is the largest phosphate resource base in Eurasia]. In: Sukhodolova VI, editor. Proceedings of the Scientific and Practical Conferences “Phosphate Raw Materials: Production and Processing”. Moscow, Russia; 2012. p. 21–30 [in Russ].Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Bushinskiy GI. Drevnie fosfority Azii i ih genezis [in Russian: Ancient phosphorites of Asia and their genesis]. Moscow: Nauka; 1966 [in Russian].Suche in Google Scholar

[6] “Kazphosphate” LLP, 2022. Mining processing complex “Karatau” branch. http://www.kpp.kz/kaz/stru_podr/gpkk/index.php. (accessed 17 October 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Derhy M, Taha Y, Hakkou R, Benzaazoua M. Review of the main factors affecting the flotation of phosphate ores. Minerlas. 2020;10(12):1109. 10.3390/min10121109.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Abbes N, Bilal E, Hermann L, Steiner G, Haneklaus N. Thermal beneficiation of sra ouertane (Tunisia) low-grade phosphate rock. Minerals. 2020;10(11):937. 10.3390/min10110937.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Rizk M. A comparative study between calcination and leaching of calcareous phosphate ore. J Eng Sci Assiut Univ Fac Eng. 2018;47(2):157–71.10.21608/jesaun.2019.115118Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Wu LLR, Shibin Y. Concentration of dolomitic phosphate rock and recovery of iodine at wengfu phosphorus mine. In Proceed. 15th International Mineral Processing Congress. Cannes, France; 1985. p. 400–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Good PC. Beneficiation of unweathered indian calcareous phosphate rock by calcination and hydration. Washington: Albany Metallurgy Research Center; 1976.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] El-Jalead IS, Abouzeid AZM, El-Sinbawy HA. Calcination of phosphates: Reactivity of calcined phosphate. Powder Technol. 1980;26:187–97.10.1016/0032-5910(80)85061-3Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zafar IZ, Ashraf M. Selective leaching kinetics of calcareous phosphate rock in lactic acid. Chem Eng J. 2007;131(1):41–8.10.1016/j.cej.2006.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Ashraf M, Zafar ZI, Ansari TM. Selective leaching kinetics and upgrading of low-grade calcareous phosphate rock in succinic acid. Hydromet. 2005;80(4):286–92. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2005.09.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Leal JP. A análise do Programa “HSC Chemistry”. Quimica. 1999;2(75):18. 10.52590/M3.P599.A3000899.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Beletski VS. Malaja gornaja jenciklopedija [in Russian: Small Mountain Encyclopedia]. Donetsk: Donnbass; 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Korovkin MV, Ananyeva LG. Infrakrasnaja spektroskopija karbonatnyh porod i mineralov [in Russian: Infrared spectroscopy of carbonate rocks and minerals]. Tomsk: TPU; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Tarasevich BN. IK spektry osnovnyh klassov organicheskih soedinenij [in Russian: IR spectra of the main classes of organic compounds]. Moscow: Lomonosov Moscow State University; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Nakamoto K. Infrared and Raman spectra of inorganic and coordination compounds. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1991.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Papko LF, Kravchuk AP. Fiziko-himicheskie metody issledovanija neorganicheskih veshhestv i materialov [in Russian: Physico-chemical methods of research of inorganic substances and materials]. Minsk: Belarusian State Technical University; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Bukovshin VV. Sovremennye metody issledovanija mineral’nogo veshhestva: Termicheskij i termoljuminescentnyj analizy [in Russian: Modern methods of mineral substance research: Thermal and thermoluminescent analyses]. Voronezh: Voronezh State University; 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Ptacek P. Apatites and their synthetic analogues: Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications. London: IntechOpen; 2016. 10.5772/59882.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Nriagu JO, Moore PB. Phosphate Minerals. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984.10.1007/978-3-642-61736-2Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Yoder CH. Ionic Compounds. Applications of Chemistry to Mineralogy. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2006.10.1002/0470075104Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Petruk W. Applied mineralogy in the mining industry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000.10.1016/B978-044450077-9/50009-2Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Bulakh AG, Zolotarev AA, Krivochichev VG. Obshhaja mineralogija [in Russian: General mineralogy]. Moscow: Academia; 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Fei X, Jie ZH, Jiyan CH, Wang J, Wu L. Research on enrichment of P2O5 from low-grade carbonaceous phosphate ore via organic acid solution. J Anal Methods Chem. 2019;2019:9859580 10.1155/2019/9859580.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Haweel CKH, Abdul-Majeed BA, Eisa MY. Beneficiation of Iraqi akash at phosphate ore using organic acids for the production of wet process phosphoric acid. Al-Khwarizmi Eng J. 2013;9(4):24–38.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Arroug L, Elaatmani M, Zegzouti A. Low-grade phosphate tailings beneficiation via organic acid leaching: Process optimization and kinetic studies. Minerals. 2021;11:492. 10.3390/min11050492.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Economou ED, Vaimakis TC. Beneficiation of greek calcareous phosphate ore using acetic acid solutions. Ind Eng Chem Res. 1997;36(5):1491–7. 10.1021/ie960432b.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Economou ED, Vaimakis TC, Papamichael EM. Kinetics of dissolution of the carbonate minerals of phosphate ores using dilute acetic acid solutions. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1998;245(1):164–71. 10.1006/jcis.1998.5395.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Economou ED, Vaimakis TC, Papamichael EM. The kinetics of dissolution of the carbonate minerals of phosphate ores using dilute acetic acid solutions: The case of pH range from 3.96 to 6.40. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2002;245(1):133–41. 10.1006/jcis.2001.7931.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Dorphman MD, Bussen IV, Dudkin OB. Nekotorye dannye po izbiratel’nomu rastvoreniju mineralov [in Russian: Some data on selective dissolution of minerals]. Proceedings of the Mineralogical Museum. Vol. 9: 1959. p. 167–71.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Voldman GM, Zelikman AN. Teorija gidrometallurgicheskih processov [in Russian: Theory of hydrometallurgical processes]. 4th edn. Moscow: Intermet Engineering; 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Zafar IZ, Anwar MM, Pritchard DW. Selective leaching of calcareous phosphate rock in formic acid: Optimisation of operating conditions. Min Eng. 2006;19(4):1459–61.10.1016/j.mineng.2006.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Gharabaghi M, Irannajad M, Noaparast M. A review of the beneficiation of calcareous phosphate ores using organic acid leaching. Hydromet. 2010;103(1):96–107. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Gharabaghi M, Noaparast M, Irannajad M. Selective leaching kinetics of low-grade calcareous phosphate ore in acetic acid. Hydromet. 2009;95:341–5. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.04.011.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”