Abstract

Red elemental nano-selenium, which is an important biological form of selenium, exhibits very low toxicity and remarkable biological properties and thus has several positive effects. For instance, it shows antioxidation and antistress characteristics, promotes growth and improves immunity. However, owing to its nanoscale size, it is very difficult to disperse and stabilize during synthesis and storage. In this study, nanoscale selenium with a mass content of 2.06% and an average particle size of 49 nm was prepared by the chemical reduction method. The analysis demonstrated that the surface phospholipids formed lamellar structures after directional freezing, and the nano-selenium particles were distributed in the middle of the lamellar. The nano-selenium particles were efficiently dispersed due to their lamellar structure and amphiphilicity. The particles displayed excellent stability and remained relatively unchanged after 20 days of storage in solution or solid state. The difficulties associated with the dispersion and storage stability of nanometer selenium during preparation were solved.

1 Introduction

Selenium is an essential trace element for animal growth and is an important part of selenoproteins. Selenium deficiency may lead to immune deficiency, muscular dystrophy and exudative inflammation. Different forms of selenium exhibit different functions, including antioxidant ability, promoting cell growth, improving immunity, resisting heat stress, improving intestinal health and regulating body metabolism. Thus, the different forms can be used as selenium supplements for animals [1,2].

In the animal diet, selenium mainly exists in the form of inorganic selenium (selenate and selenite), organic selenium (yeast selenium, selenomethionine and selenocysteine) and nano-selenium (selenium in a simple form). The different forms of selenium are absorbed by animals with different efficiencies through different mechanisms. Under normal physiological conditions, the absorption rate of organic selenium is 70–90%, while the direct absorption rate of selenite is lower than 60%. Because of its small particle size and large specific surface area, nano-selenium can interact with the physiological system rapidly and better maintain the morphology of the intestinal mucosa than yeast selenium. Specifically, it can increase intestinal mucosal permeability and improve intestinal absorption efficiency by forming nano-emulsion droplets. Thus, nano-selenium is used in animal feed because of its high bioavailability and low toxicity [3].

At present, the methods available for synthesizing nano-selenium primarily include chemical and biological routes [4]. The biological methods involve the use of substances produced during microbial growth (such as metabolites and enzymes) as well as plant extracts (such as proteins, flavonoids and vitamins) to reduce selenium salts (sodium selenite and selenite, among others) for synthesizing red nano-selenium particles [5,6]. However, microbial culture and plant extracts require specialized equipment to prepare, involve complex processes that are not environmentally friendly and are present in low contents [7]. Moreover, their presence in higher contents can cause toxicity in the microorganisms themselves. Thus, scaling their production from the laboratory scale to the industrial scale is a major challenge.

The chemical methods involve directly synthesizing nano-selenium by reducing a selenium salt (sodium selenite or selenite) using a reducing agent [8,9]. Generally, a surfactant or stabilizer is added during the synthesis process to ensure that the size of the synthesized nano-selenium particles is 0–1,000 nm so that they can exist stably without forming aggregates [10]. However, this requires a high degree of dispersion and can result in instability during long-term storage, resulting in their agglomeration. Thus, most chemical methods use large amounts of dispersants in concentrations of up to 1% [11]. However, dispersants and stabilizers are not conducive to matrix absorption and cause environmental pollution. This limits the use of chemical methods for the large-scale production of nano-selenium in high concentrations.

For example, Blinov et al. [10] prepared nano-selenium by using quaternary ammonium salt for dispersion and vitamin C for reduction. The electrostatic action of quaternary ammonium salt was used to disperse nano-selenium. However, due to the low selenic acid dispersion concentration (0.036 mol‧L−1), only the solution state was studied. Salem et al. [12] used orange peel waste for selenium nanoparticles with a concentration of 2 mM Na2SeO3. This concentration was extremely low and only the solution state was investigated.

Therefore, red nano-selenium particles were synthesized using sodium selenite as the selenium source, vitamin C as the reducing agent, soybean phospholipid and water-soluble starch as the stable dispersant. In addition to the solution state, the storage stability was investigated. Because of their unique molecular structure, phospholipids readily form molecular layers [13,14]. Thus, we attempted to disperse and encapsulate the nano-selenium particles between two films of phospholipids by directional freezing to prevent their agglomeration and ensure their stability and synthesis in a high concentration. Moreover, this method uses a phospholipid and water-soluble starch as stabilizers. Both exhibit good biocompatibility and thus do not prevent matrix absorption, in contrast to surfactants.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of nano-selenium

As shown in Figure 1, 13.5 g of water-soluble starch was added to 180 mL of deionized water, and the mixture was heated to 90°C. Next, the temperature was reduced to 50°C, and 4.0 g of a soybean phospholipid (Beijing Chinaholder Biotech Co., Ltd) was added to the solution under magnetic stirring. Subsequently, 0.9 g of sodium selenite was dissolved in the solution. The solution temperature was reduced to 10°C and 20 mL of a vitamin C (VC) solution (0.1 g‧mL−1) was slowly added. The reaction proceeded for 1 h to obtain a nano-selenium suspension, as shown in Figure 1a. Finally, directional freezing was performed followed by freeze-drying to obtain the desired product, as shown in Figure 1a. The yellow arrows in the figure point to the layers or sheets of the final product.

Synthesis of nano-selenium: (a) digital picture of synthesized solution sample and (b) digital picture of freeze-dried sample.

2.2 Determination of nano-selenium concentration

To determine the concentration of nano-selenium in the obtained product, 0.1000 g of the product was weighed and digested using nitric acid and perchloric acid. The solution was then diluted with 50% hydrochloric acid to the corresponding concentration. Next, the solution was analyzed using a dual-channel atomic fluorescence spectrometer, and the selenium content was determined using the expression given below:

where c is the concentration of nano-selenium in the test solution (ng‧mL−1), V is the volume of the test solution (mL), N is the dilution multiple of the test solution and m is the quantity of the sample to be weighed (g).

2.3 Structural characterization and performance evaluation

A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) system (EVO 18, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to evaluate the particle size, morphology and distribution of the nano-selenium particles in the obtained sample. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, EVO18) was used to analyze the elemental distribution of the sample. An ultraviolet–visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectrophotometer (Lambda 25, PerkinElmer, America) was also used to characterize the nano-selenium particles. The analysis was performed for the wavelength range of 200–500 nm. Finally, a dual-channel atomic fluid spectrometer (AFS-2000, Beijing Kechuang Haiguang Instrument Factory) was used to determine the concentration of selenium in the obtained sample. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were measured using a D8 Advance (Brucker, Germany) diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation) at a generator voltage of 40 kV. The thermal performance of our samples was analyzed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC, Q2000, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) at a scanning rate of 10°C‧min−1. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves were obtained with a TGA2 (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) at a heating rate of 10°C‧min−1 in a nitrogen atmosphere.

3 Results and discussion

After freezing the nano-selenium-containing solution shown in Figure 1a and thawing it to room temperature, a flaky solid was obtained, as shown in Figure 2a. Subsequently, after freeze-drying, the flaky material shown in the yellow box in Figure 2b was obtained. SEM analysis showed that the material is lamellar (Figure 2c), with a large number of nano-selenium particles attached to the sheets (Figure 2d). Generally, the nanoparticles are coated with phospholipids to form a microcapsule. And in this study, the synthesized nanoparticles exhibited homogenous morphologies. However, during directed freezing, the phospholipids in the solution interact with and realign along the surface of the ice crystals, resulting in the development of lamellar phospholipids, due to the frame-induced effect [15]. The average particle size was approximately 49 nm, as determined using the software ImageJ. Thus, it was confirmed that nano-selenium particles were synthesized successfully using the proposed method. Moreover, the use of the phospholipid resulted in the formation of a lamellar structure after directional freezing, with the nano-selenium particles dispersed within these lamellar structures.

Digital and electron microscopy images of the synthesized sample: (a) digital pictures after freeze-thawing, (b) digital pictures of samples after freeze-drying and (c and d) electron microscopic images after freeze-drying.

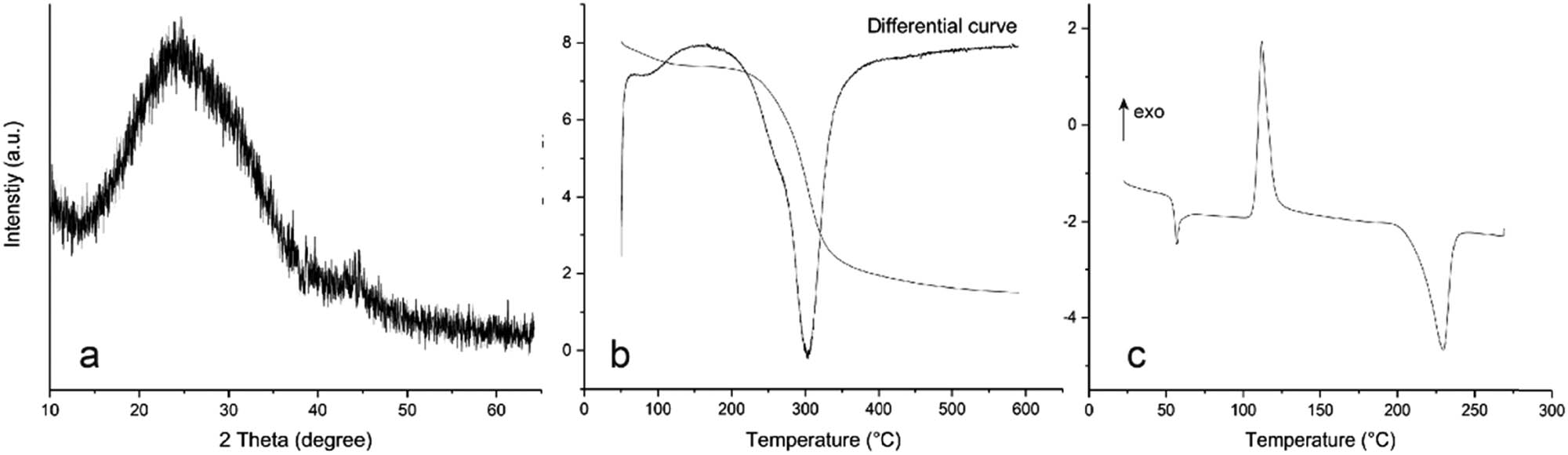

The samples were characterized by DSC, TGA and XRD (Figure 3). There were no obvious crystal spectral features according to XRD (Figure 3a). This indicates that the prepared nano-selenium was amorphous, containing only nano-selenium aggregates. As can be seen from Figure 3b, when the sample exceeds 250°C, it began to dissolve slowly, indicating that when the sample was below 250°C, there was no other substance except partial evaporation of water. The DSC analysis exhibits two heat-absorbing peaks near 56.7°C and 229.7°C, which are, respectively, attributed to the melting temperatures of a-Se and t-Se (Figure 3c) [16]. The exothermic peak appeared at 112.3°C, indicating that the crystallinity of a-Se in the melting state increased, changing the crystal type to tripartite t-Se.

XRD, TGA and DSC spectrogram of the sample: (a) XRD curve, (b) TGA curve and (c) DSC curve.

The selenium concentration of the sample was determined using the method described in Section 2.2 and found to be 2.06 wt%. To analyze the distribution of the nano-selenium particles within the lamellae, EDS analysis was performed. After freeze-drying, lamellae were formed due to the frame-induced effect of ice crystals, and nano-selenium particles were randomly distributed on the lamellae (Figure 4a and b). During directional freezing, the excess phospholipids in the solution formed the lamellar layer while the phospholipids remained wrapped on the nano-selenium, preventing aggregation. The mass content of selenium was determined as 2.35% via EDS (Figure 4c), which was consistent with the detected concentration. The selenium nanoparticles were subjected to another round of directional freeze drying and were found to be evenly and randomly distributed.

EDS spectrum of synthesized sample and results of its elemental analysis: (a) distribution spectrum of selenium in the sample, (b) energy spectra of each element contained in the sample and (c) content of each element in the sample.

Next, to evaluate the particle size and stability of the nano-selenium particles sandwiched within the phospholipid lamellae, UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry was performed. According to the literature [17,18,19], an increase in the size of nano-selenium particles increases the UV absorption wavelength of the suspension. As per previous reports, the average diameter corresponding to the absorption peaks observed at wavelengths smaller than 300 nm is less than 70.9 ± 9.1 nm (Figure 5). This is consistent with the results of this study, wherein the adsorption peak wavelength was determined to be 264 nm and the average size of the nano-selenium particles was 49 nm. At the same time, the stability of the sample was also verified. A newly prepared liquid sample not subjected to freeze drying, a sample subjected to freeze drying and a sample stored for 20 days after freeze drying were subjected to UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry. The results are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the absorption peak did not move significantly, indicating that the nano-selenium particles did not undergo significant aggregation during the freeze drying and storage processes and thus exhibited good stability. The stability of the nano-selenium particles in the liquid state was also investigated. It can be seen from Figure 5 that the absorption peak of the nano-selenium particles in a non-lyophilized solution shifted to a higher wavelength after storage for 10 and 20 days. However, the shift was not pronounced, indicating that while the nano-selenium particles formed some aggregates, their absorption peak wavelength remained lower than 300 nm even after 20 days. Thus, the average particle size remained smaller than 70 nm, indicating that the nano-selenium particles were stable even in a solution.

UV absorption curves of various solutions.

4 Conclusions

In this study, inorganic selenium was reduced by VC and dispersed using a phospholipid to obtain a suspension of nano-selenium particles with a concentration of approximately 2.06% and an average particle size of approximately 49 nm. Because of the unique molecular structure of the phospholipid, it readily formed a molecular layer, which transformed into a lamellar structure after directional freeze drying. SEM imaging confirmed that the nano-selenium particles formed an interlayer within the lamellar structure of the phospholipid. UV-Vis absorption analysis confirmed that the nano-selenium particles did not form aggregates for up to 20 days both in solid and solution forms and thus exhibited high stability. In comparison to earlier research, this study was characterized by simple preparation and high stability. The dispersed system utilized eco-friendly bio-derived raw ingredients. Importantly, the concentration of nano-selenium synthesized by this methodology was relatively high, approaching industrial production levels, and had a wide range of applications.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Guangzhou Tanke Bio-Tech Co., Ltd, in samples testing.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Research Project of Guangdong Industry Polytechnic (KJ2021-08).

-

Author contributions: Jinhui Huang: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft; Xue Lin: resources; writing – review and editing; Yongchuang Zhu: writing – review and editing; Xuejiao Sun: formal analysis; Jiesheng Chen: visualization; Yingde Cui: project administration, funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Kumar A, Prasad KS. Role of nano-selenium in health and environment. J Biotechnol. 2021;325(4):152–63. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Farah SD, Emad K, Ali H. Synthesis Of selenium nanoparticles. Eurasian J Phys Chem Math. 2022;7(3):67–71. 10.1038/s41598-019-57333-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Bhattacharjee A, Basu A, Bhattacharya S. Selenium nanoparticles are less toxic than inorganic and organic selenium to mice in vivo. Nucleus. 2019;62(3):259–68. 10.1007/s13237-019-00303-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Khanna PK, Bisht N, Phalswal P. Selenium nanoparticles: A review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater Adv. 2022;3(1):1415–31. 10.1039/D1MA00639H.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Cui YH, Li LL, Zhou NQ, Liu JH, Huang Q, Wang HJ, et al. In vivo synthesis of nano-selenium by Tetrahymena thermophila SB210. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2016;95(5):185–91. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.08.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Akcay FA, Avci A. Effects of process conditions and yeast extract on the synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by a novel indigenous isolate Bacillus sp. EKT1 and characterization of nanoparticles. Arch Microbiol. 2020;202(8):2233–43. 10.1007/s00203-020-01942-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Hashem AH, Khalil AMA, Reyad AM, Salem SS. Biomedical applications of mycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using penicillium expansum ATTC 36200. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199(10):3998–4008. 10.1007/s12011-020-02506-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Yunusov KE, Sarymsakov AA, Turakulov FM. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of the nanocomposites based on sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and selenium nanoparticles. Polym Sci Ser B. 2022;64(1):68–77. 10.1134/s1560090422010080.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Alam H, Khatoon N, Raza M, Ghosh PC, Sardar M. Synthesis and characterization of nano selenium using plant biomolecules and their potential applications. BioNanoScience. 2018;9(1):96–104. 10.1007/s12668-018-0569-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Blinov AV, Maglakelidze DG, Yasnaya MA, Gvozdenko AA, Blinova AA, Golik AB, et al. Synthesis of selenium nanoparticles stabilized by quaternary ammonium compounds. Russ J Gen Chem. 2022;92(3):424–9. 10.1134/s1070363222030094.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Wen S, Hui Y, Chuang W. Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):178–88. 10.1515/gps-2021-0018.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Salem SS, Badawy MSEM, Al-Askar AA, Arishi AA, Elkady FM, Hashem AH. Green biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using orange peel waste: Characterization, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Life. 2022;12(6):893.10.3390/life12060893Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Sut TN, Park S, Yoon BK, Jackman JA, Cho NJ. Supported lipid bilayer formation from phospholipid-fatty acid bicellar mixtures. Langmuir. 2020;36(18):5021–9. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00675.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Jackman JA, Cho NJ. Supported lipid bilayer formation: Beyond vesicle fusion. Langmuir. 2020;36(6):1387–400. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03706.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Dong Y, Sun Y, Wang L, Wang D, Zhou T, Yang Z, et al. Frame-guided assembly of vesicles with programmed geometry and dimensions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(10):2607–10. 10.1002/anie.201310715.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Chen Z, Shen Y, Xie A, Zhu J, Wu Z, Huang F. L-cysteine-assisted controlled synthesis of selenium nanospheres and nanorods. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9(3):1327–33. 10.1021/cg800398b.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Vahdati M, Tohidi Moghadam T. Synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles-lysozyme nanohybrid system with synergistic antibacterial properties. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):501–10. 10.1038/s41598-019-57333-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Lin Z-H, Chris Wang CR. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater Chem Phys. 2005;92(2–3):591–4. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.02.023.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Asghari-Paskiabi F, Imani M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M, Rafii-Tabar H. Fusarium oxysporum, a bio-factory for nano selenium compounds: Synthesis and characterization. Sci Iran. 2018;25(3):1857–63. 10.24200/sci.2018.5301.1192.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”