Abstract

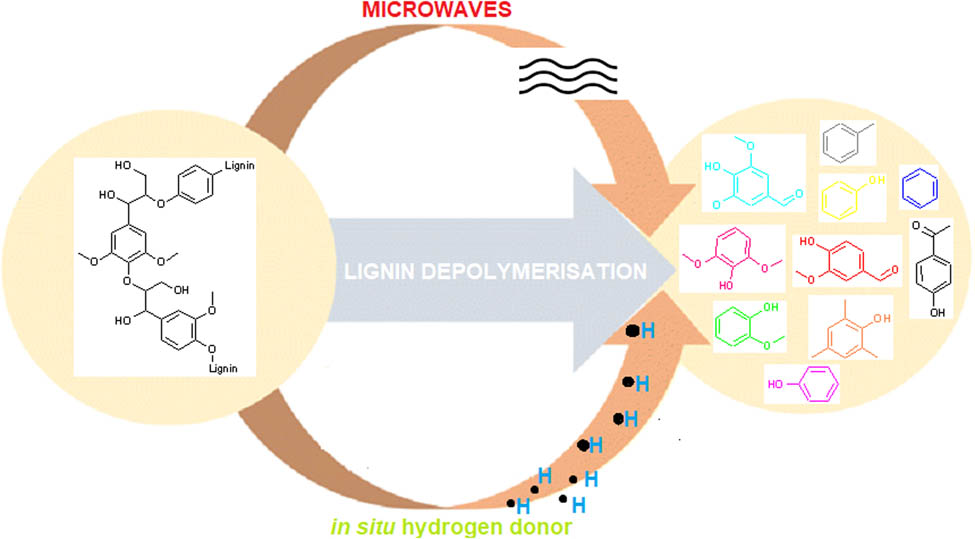

The effective exploitation of lignin, the world’s largest renewable source of aromatics, is alluring for the sustainable production of chemicals. Microwave-assisted depolymerisation (MAD) of lignin using hydrogen-donating solvents (HDS) is a promising technique owing to its effective volumetric heating pattern and so-called “non-thermal effects.” However, lignin is a structurally complex bio-polymer, and its degradation produces a myriad of products; consequently, MAD reaction mechanisms are generally complex and poorly understood. This review aims to provide a perspective of current research into MAD reaction mechanisms involving HDS, with the goal to give researchers an overall understanding of MAD mechanisms and hopefully inspire innovation into more advanced methods with better yields and selectivity of desired aromatics. Most reaction mechanisms were determined using characterisation methods such as GC-MS, MALDI-TOF, 2D-NMR, GPC, and FT-IR, supported by computational studies in some instances. Most mechanisms generally revolved around the cleavage of the β–O–4 linkage, while others delved into the cleavage of α–O–4, 4–O–5 and even C–C bonds. The reactions occurred as uncatalysed HDS reactions or in combination with precious metal catalysts such as Pt/C, Pd/C and Ru/C, although transition metal salts were also successfully used. Typical MAD products were phenolic, including syringol, syringaldehyde, vanillin and guaiacol.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The circular economy (CE) revolves around the concept of industrial ecology [1], endeavouring to promote sustainable environmental benevolence and economic viability [2]. CE is frequently associated with reducing, reusing, and recycling activities [3], aimed at reducing the current reliance on non-renewable petroleum-based sources in industrial, pharmaceutical, and agricultural domains [4,5]. CE is a promising remedy to current unsustainable consumption and production trends [6,7], in line with the United Nations’ sustainable development goal (UN SDG-12) of “Responsible consumption and production” [5,8].

Lignocellulosic biomass is a key component in the sustainable production [9,10] of various chemicals, polymers, materials, solvents, compounds [11], and energy [4,5,6]. In particular, lignin is the world’s largest renewable source of aromatic compounds [7], and its conversion into useful aromatic chemicals or materials is crucial, especially given the copious amount of lignin produced as a low-value by-product, particularly in the pulp industry or cellulosic ethanol generation [12].

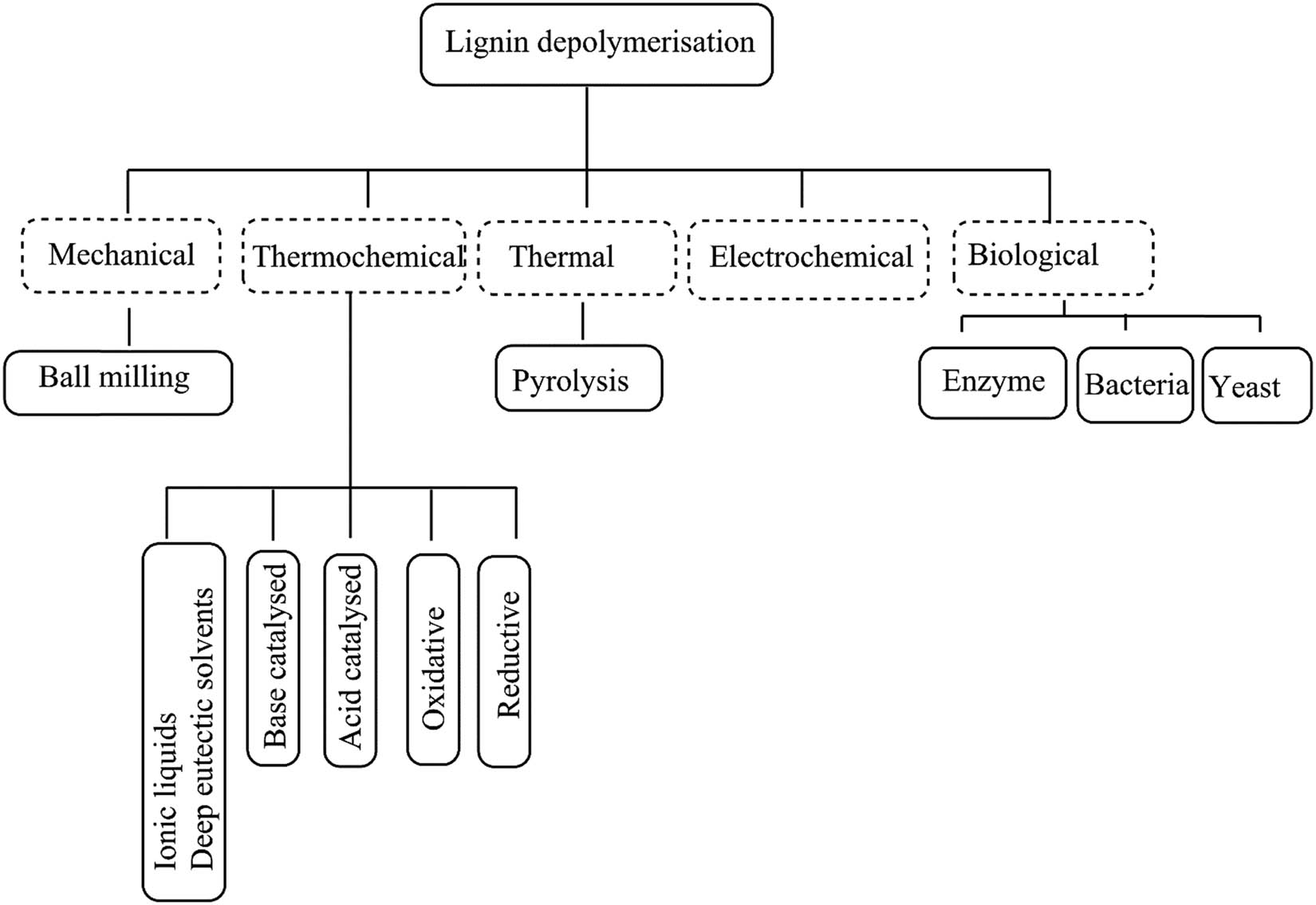

In order to degrade lignin into useful aromatic chemicals, numerous lignin depolymerisation techniques are utilised, some of which are shown in Figure 1. The choice of the technique partly determines the yield and selectivity of aromatic chemicals produced [13]. In particular, the reductive depolymerisation method utilising in situ hydrogen from hydrogen-donating solvents (HDS) is a promising technique for lignin depolymerisation [14,15], with good yields of aromatics. Conveniently HDS such as ethanol, formic acid (FA), and acetic acid are also typically cheap, recyclable, environmentally safe, and easily available. In addition, they can even be produced on-site using biomass at bio-refineries [16].

Lignin depolymerisation techniques.

Lignin depolymerisation to aromatic monomers is generally time consuming and an energy-intensive endeavour. As a result, lignin depolymerisation is often coupled with microwave (MW)-assisted heating, a technology that has been successfully applied in other areas including extraction studies, and synthetic organic and nanomaterials chemistry [17,18,19,20], with the hope of improving the overall efficiency of MW-assisted depolymerisation (MAD) of lignin.

Lignin is a structurally complex polymer with numerous linkages and different functionalities [21,22,23]. Although substantial advancement in MAD has been realised, effective lignin to single value-added aromatic chemicals remains a significant challenge [12]. The mechanism of MAD is generally complicated and numerous compounds are often produced, posing a separation challenge. In particular, MW-assisted reactions are also believed to induce unique so-called “non-thermal effects” [24], resulting in reaction pathways unique to MAD. In turn, it affects the yield and selectivity of produced aromatic chemicals [11,25,25,26,27,28,29]. This review provides a comprehensive critical review of the current literature on the reaction mechanisms involved in the application of environmentally benign and sustainable HDS in the MAD of lignin into aromatic compounds in a sustainable manner to display the common pathways that occur during MAD, in particular, to investigate the presence or relevance of the “non-thermal effects” on the proposed reaction mechanisms. Ultimately, we hope to give researchers a better insight into MAD reaction mechanisms and encourage the refinement of current techniques into viable unambiguous and reproducible methods that can be upscaled to the industrial level to produce a single aromatic product.

2 Lignin composition and structure

Lignin is a heterogeneous aromatic biopolymer with a complex three-dimensional structure of polymerised phenyl propane (C9) units. It is composed of three main units, namely p-hydroxyphenyl, guaiacyl, and syringyl via ether bonds or carbon–carbon bonds [30,31,32].

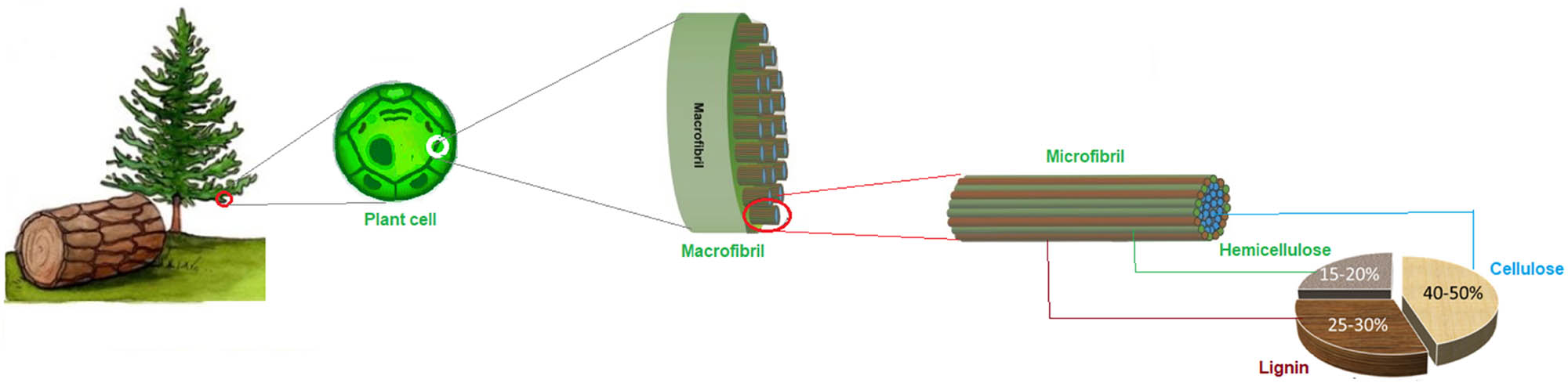

In plant cell walls, lignin fills the spaces between cellulose and hemicellulose polymers binding the lignocellulose matrix together, analogous to cement used in construction (Figure 2). This cross-linking with the polysaccharides cellulose and hemicellulose confers strength and rigidity to the cell walls and the plant system overall [21]. Lignin accounts for 15–30% of the dry weight of plants, and its composition and amount depend on plant age, conditions of plant growth, and species, among other factors. In general, grasses contain the least amount of lignin followed by hardwoods, while softwoods have the most lignin. In the literature, lignin naturally present in biomass is termed “native lignin,” and once extracted from the biomass it is referred to as either “technical lignin” or “isolated lignin”; the extraction of lignin from biomass invariably also affects its structure [33,34].

Typical biomass composition.

Considerable research has focused on the full characterisation and the structure determination of native lignin. Many of lignin’s main structural features and linkages have been elucidated through advances in spectroscopy, including advanced nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods [35], thermogravimetric analysis [36], and computational studies [37]. Despite these efforts, the lignin’s pristine structure is complex and insufficiently understood [38,39,40,41].

As a consequence, new lignin depolymerisation techniques are a challenging endeavour. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that lignin is a heteropolymer comprising at least three different monolignols randomly linked via various bonds through free radical–radical coupling among the monomer units in lignin (Figure 3). The ether bond functionality is the most common linkage between the monomer units in lignin, although C–C bonds are also present [8,41,42,43]. Approximately, 66% of the linkages between the monomers are ether bonds. Of the ether bonds, the most abundant are the β–O–4 alkyl–aryl ether linkage between two units, although α–O–4 or 4–O–5 ether bonds are also possible. Therefore, most depolymerisation methods focus on cleaving these weaker ether bonds in particular, while deliberately avoiding the stronger C–C bonds, which need harsher processing conditions. A typical lignin structure and associated bonds are depicted in Figure 3.

The typical lignin structure, its constituent monolignols, and common bond linkages.

Lignin structure is inevitably modified to varying degrees during its isolation from biomass. Milder biological and organosolv treatments are known to produce lignin closest in structure to native lignin, although they may sometimes be inefficient. Other more efficient methods of lignin extraction and depolymerisation inadvertently result in the replacement of weaker ether bonds with refractory C–C bonds, which are more difficult to depolymerise as a result of the recalcitrant nature of lignin that provides its protective role in plants as a defence against biological and chemical attacks [44].

Shu et al. [45] and Milovanović et al. [46] proved a link between lignin feedstock and bio-oil yield [46]. A higher proportion of syringol monomers (S units) to guaiacol monomers (G units) ratio (S/G ratio) was found to be favourable in maximising monomer yields in bio-refining applications [44,47]. A reduction in the presence of unwanted C–C bonds in S units, which have O–CH3 groups on both carbon 3 and carbon 5 [48], is thought to reduce the potential formation of C–C bonds in S units compared to G units, which would otherwise replace weaker ether bonds with stronger C–C bonds; this subsequently affects lignin’s physiochemical properties [49,50] and ultimately negatively impacts on the valorisation of lignin [51,52].

3 Lignin model compounds

As a consequence of lignin’s structural complexity and heterogeneity, sensible reaction mechanisms are often difficult to deduce using pure lignin. Therefore, a significant number of studies are conducted utilising lignin model compounds first to systematically focus on desired bonds and their cleavage mechanisms.

Many monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric model compounds have been considered for various lignin depolymerisation studies. These compounds are used to simulate the main characteristics of lignin such as inter-unit links, methoxyphenol groups and propanoid chains, and subsequently extrapolate the findings to lignin [21,53]. Some simple examples of model compounds and the bonds they are used to represent are shown in Figure 4.

Lignin model compounds and representative linkages.

The use of simpler compounds simplifies the characterisation challenges usually associated with the myriad of aromatic products, which can number in the hundreds. By using model compounds, researchers have been able to better comprehend the effect of particular reaction conditions on the cleavage mechanism of particular moieties and the likely products. This has enabled reaction mechanisms to be proposed and then applied to lignin. Model compounds have fewer variables to consider, which has enabled the analysis of the performance, kinetics, and stability of intermediates and products in lignin depolymerisation [53]. Better insights into the roles of various reaction parameters in monomer yield and/or bond cleavage have also been determined before embarking on much more complex lignin processes.

While lignin model compounds are useful in formulating reaction mechanisms, it is important to note that simply extrapolating their mechanisms to lignin can be misleading. Lignin contains a multitude of other linkages whose reaction intermediates and products may affect each other’s mechanisms due to thermodynamics and kinetics. Nevertheless, the information provided by lignin model compounds is invaluable in clarifying the mechanisms likely to be encountered in lignin depolymerisation.

4 MW-assisted technology in chemistry

MW radiation is part of the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS), and it is found between infrared and radio waves (Figure 5). This technology was first developed by the military in radar applications. Later, it was used in MW ovens and for wireless radio communication [54,55,56,57]. It became more mainstream largely due to the invention of the MW generator (magnetron) by A. W. Hull [58] in the 1970s, resulting in mass production, which dramatically reduced the price of MW units. A magnetron is essentially a vacuum device that converts direct current electrical energy into MWs.

The EMS.

MWs have wavelengths between 1 m and 1 mm, corresponding to a frequency of between 0.3 and 300 GHz [59]. Although other frequencies can theoretically be used as well, a frequency of ∼2.45 GHz is used for domestic units by regulation to avoid potential interference with other equipment that also utilises MW radiation, such as radar and telecommunications equipment [60].

Before the advent of MW heating, most reactions employed slower conventional heat transfer equipment, including heating jackets, oil baths, and sand baths. These depend on a temperature gradient passing on heat to the inner parts of the apparatus [61]. However, MW energy is introduced into the reactor remotely and passes through the vessel walls, uniformly heating only the reactants and solvent, rather than heating the vessel itself (Figure 6) [62]. Rapid heating of substrates shortens the reaction time and prevents over-reaction of the obtained products, reducing by-products and/or decomposition products [62].

A comparison of conductive and MW-assisted heating mechanisms.

In 1986, Gedye et al. [63] reported results comparing MW-assisted reactions versus conventionally heated reactions. The results proved that MW irradiation considerably improved the reaction rate, increased efficiency, as well as added some “non-thermal effects” to the reaction. Other workers also experimented with other types of reactions [64]. When used for a polymerisation process, Bakibaev et al. [65] claimed that the reaction proceeded hundreds of times faster than conventional heating; while a pyrolysis reaction had a lower activation energy compared to conventional heating [29]. Other researchers have since claimed improved aromatic compound yield and product selectivity after conducting MW-assisted lignin depolymerisation [7].

MW-assisted reactions are thought to occur by a combination of thermal and “non-thermal effects” [55]. Some reports have suggested that non-thermal effects improve the diffusion of the substrate, which helps with mass transfer in reactions [66]. Super-heating effects are thought to cause higher localised temperatures in parts of the reaction vessel compared to the bulk material, which probably makes it easier for reactions with high activation energies to occur. Some researchers also theorised that MW irradiation increases the reaction rate via non-thermal effects which increase the exponential factor and decrease the activation energy, based on the Arrhenius equation,

Several variables are involved in MW-assisted reactions, making fair comparisons of conventional and MW heating daunting. Apart from the properties of the solvents used, the volume, contents, and geometry of the reaction vessel are also crucial to provide uniform and reproducible heating. In order to achieve the best possible reproducibility, reactions should be performed in carefully designed cavities and vessels, in addition to proper temperature control, which is now possible on modern machines [62]. It can also be argued that laboratory-scale reactions use comparatively high power (300–1,000 W) for minuscule quantities. This results in uncontrolled energy input, higher temperatures, shorter reaction times, and consequently, greater yields, resulting in observations that can be speculated to be non-thermal effects.

MW heating has different effects on different substances. Overall, the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter is characterised by three different processes: absorption, transmission, and reflection. Highly dielectric materials lead to a strong absorption of MWs and consequently to rapid heating of the medium [80]. The proponent of the heating is dielectric polarisation, which depends on the ability of the dipoles to re-orientate when an electric field is applied [81,82]. Dielectric constants are often used to compare the relative heating effect of MW on different solvents. It represents the ability of a dielectric material to store electrical potential energy under the influence of an electric field. A higher dielectric constant is generally desirable for MW reactions. As a green solvent, which is globally abundant, water is a convenient solvent in MW-assisted reactions, given its high dielectric constant of 80.4ɛ S [81]. Depending on the solvents used, the dielectric constant of the lignin reaction mixture can be manipulated to influence the MW breakdown of the lignin into various chemical products. It is also important to note that the dielectric constant varies with temperature, which adds another layer of complex variables to MW-assisted reactions [18]. When solvents with comparable dielectric properties are matched, their capabilities to absorb MW and convert that absorbed energy into heat are also considered.

The dielectric constant and the dielectric loss factor are important variables in dielectric heating; the former symbolises the capacity of the material to store electric energy, while the latter symbolises the capacity of the material to disperse the electric energy [82]. Ultimately the effectiveness of materials in MW heating depends on their ability to absorb and store energy (dielectric constant) as well as the ability to disperse this internal energy as heat to the bulk material (dielectric loss); the extent of this depends on the ratio of dielectric loss to dielectric constant. This comparison is done using the loss angle. The loss angle quantifies the efficiency with which the absorbed energy is converted into heat, providing another useful parameter that can be used to compare the effect of MW on different materials [62].

The general scale-up of MW-assisted reactions from laboratory to pilot and industrial scales appears to be extremely slow with very few pilot-scale MW units globally. It could be a result of the general lack of consensus in the scientific fraternity on the proficiency of MW-assisted technology coupled with potential safety issues regarding MW radiation and the cost of industrial-type magnetrons for use in the MW units, or it could be financial due to the reluctance of industrialists to risk high capital investments retrofitting their chemical plants with MW technology without assured rewards, aside from the steep learning curve their personnel may have to contend with regarding the safe use of radiation.

4.1 MW heating mechanisms

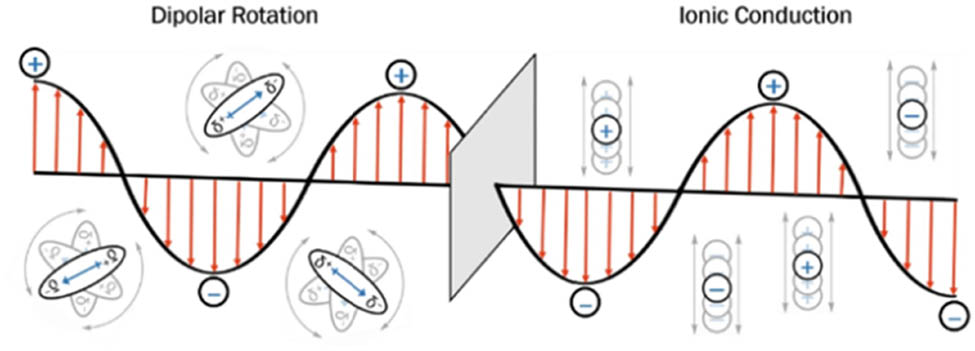

As part of the EMS, MW radiation can be divided into its electric and magnetic field components. The electric component is responsible for the two fundamental principles of MW heating, namely dipolar rotation and ionic conduction [83], while a third is regarded to be a combination of both dipolar rotation and ionic conduction mechanisms [84]. MW heating and related effects rely on dipolar polarisation and ionic conduction which are connected to various properties of the compounds [81], including permittivity, dielectric constant, dielectric/magnetic loss tangent as well as viscosity of the fluid and frequency irradiation which have a partial influence on rotation [83]. Further mathematical details, which are beyond the scope of this review, are outlined in other reports [85,86].

4.1.1 Dipolar polarisation mechanism

In dipolar polarisation, the material should have a dipole to be heated, and when it absorbs energy from the waves, the transmitted MWs are converted into specific frequencies [87,88]. When MW penetrates the molecules, the fluctuating electric field leads to extreme and repetitive oscillation and realignment of dipoles (Figure 7). Subsequently, molecular friction is generated inside the material as internal energy, which causes the material to be heated up with the dissipation of internal heat to the bulk of the material.

Dipolar and ionic conduction mechanisms of an oscillating electric field in an MW as it changes between positive and negative polarity.

For dielectric heating to occur, the frequency of the dipole must be low enough to allow the dipoles enough time to react to the alternating electric field, but high enough to avoid syncing with the oscillating phase and rotating in phase with the current. This allows the dipole enough time to align itself with the electric field but not enough to exactly follow the electric field. As such, this generates a phase difference between the orientation of the field and the dipole, causing an energy loss from the dipole by molecular friction and collisions, giving rise to dielectric heating [85,86].

4.1.2 Ionic conduction mechanism

Another major interaction of the electric field component with the sample is via the ionic conduction mechanism. This mechanism depends, among other factors, on the ion concentration, ionic size, the dielectric constant of the medium, the MW frequency, and the viscosity of the reacting medium [80]. The ions present in a solution are influenced by an electric field resulting in their migration throughout the polar liquid as the electric field changes, which causes them to move back and forth through the solvent, generating friction as well as increasing the rates of collision, ultimately expending their kinetic energy as heat energy (Figure 7) [59,83,89].

The ionic conduction mechanism is a much stronger interaction compared to the dipolar mechanism with regard to heat-generating capacity. The heat generated via the ionic conduction mechanism is added to that from the dipolar mechanism, overall resulting in a higher final temperature in ionic solutions. This is referred to as interfacial polarisation and could be considered as the third mechanism. It is an important mechanism for systems composed of both conducting and non-conducting materials [84], compared to pure polar solvents such as water.

Non-polar solvents do not have a dipole; therefore, they are not heated effectively under MW irradiation, if at all. Xu et al. [90] used various solvents to liquefy southern pine sawdust to produce phenolic-rich products using MW irradiation. Hexane (a non-polar solvent) was observed to have very low reactivity as a result of its low ability to interact with MW radiation. This led to low reaction temperature, and additionally, the solvent also lacked nucleophilic reactive functionalities, such as –OH groups, thus causing the solvent to fail to break the C–O–C linkages in cellulose and lignin, respectively [90]. Conversely, methanol and ethanol as polar solvents had a high reaction activity for decomposition. Their lower molecular weight also provided favourable permeability and fluidity at higher reaction temperatures, which were beneficial for biomass conversion in lignin studies. Increasing the carbon chain of alcohols, however, increased the hydrophobicity and reduced the effect of MW [90].

The addition of a small amount of salt or a polar solvent with a large loss tangent was observed to improve the MW heat generation of non-polar solvents [40,64], attributed to the rapid energy transfer between adjacent microwavable polar molecules, which had been superheated, and non-polar molecules (Figure 8) [62]. This allows the use of non-polar solvents in MW heating reactions when mixed with polar solvents; however, miscibility challenges may abound. The advent of environmentally friendly and recyclable ionic liquids with excellent dielectric properties promises to provide good substitutes for dipolar aprotic solvents in lignin depolymerisation studies [91,92].

Localised superheating resulting from MW absorption by polar solutes and subsequent dissemination to non-polar solutes.

5 Hydrogen donors and associated donation mechanisms

Dry lignin, without any inherent moisture, has a low MW ability [22,93]; therefore, depolymerisation of the material via MW-assisted heating often requires the addition of MW receptors, including the addition of polar aliphatic alcohols to the lignin depolymerisation reaction vessel [94]. The successful addition of such alcohols combined with suitable catalysts has been shown to improve the depolymerisation of lignin, even under mild reaction conditions.

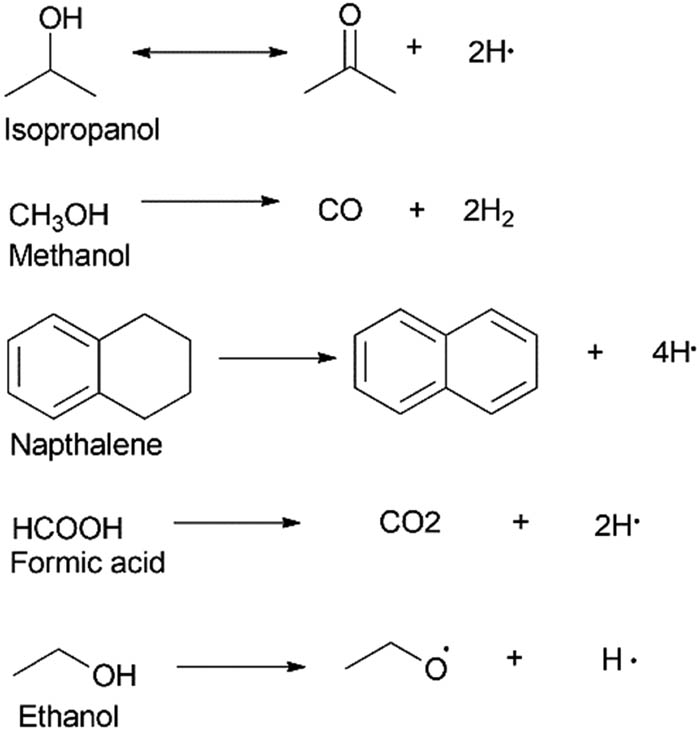

Hydrogen donor solvents are generally low-molecular-weight organic solvents [95] with the capacity to release atomic hydrogen in situ to varying degrees once they are heated to a specific temperature [22,96,97,98,99,100]. Connors et al. [101] established the hydrogen-donating effects of particular solvents such as FA and tetralin in the hydrocracking of Kraft lignin [101,102]. Many solvents can function as HDS, and examples include solvents such as decalin, methanol, ethanol, acetic acid, ethylene glycol (EG), glycerol, and isopropanol among others [100,103]. In liquefaction experiments, it was been observed that the atomic hydrogen atoms donated from donor solvents are more efficiently used compared to gaseous molecular hydrogen in the production of oil [96,100,104,105]. Hydrogen donation reactions of selected HDS are shown in Figure 9.

Hydrogen donation by common HDS.

HDS, either on their own or with catalysts [17,93,106,107], play several crucial roles in improving hydrolysis, hydrogenation [5], deoxygenation, and hydrocracking reactions with inhibition of polycondensation into bio-char by quenching reactive radicals produced by the heated biomass in the lignin depolymerisation process [53,100,108], in turn, improving the quality of bio-oil produced [103]. Patil et al. [95] outlined the solvent’s hydrogen-donating ability, the capability to solvate the lignin, and viscosity as important factors to consider concerning the choice of HDS [95,109]. Overall, the action of alcohols depended on their hydrogen-donation and alkylating abilities [100,110,111].

FA appears to be the most popular HDS used in research, and it has been utilised in several reports in lignin depolymerisation [44,90,112–114]. Using alkaline lignin, Shao et al. [113] enlisted MW-assisted degradation of alkaline lignin in methanol/FA media. They investigated the role played by various variables, such as FA amount, reaction temperature, and reaction time, in actual lignin depolymerisation, and reached a similar conclusion as Xu et al. [90]. They reasoned that even though FA, a typical in situ hydrogen donor was used, the anticipated hydrogenation reaction was probably not the only mechanism followed in these reactions. It appeared that the FA was also an acid catalyst based on the large amount of catalysed products, rather than typical hydrogenation products, such as hydrogenated phenyl side chains.

This theory was further corroborated by Zhou et al. [114] using alkaline lignin and de-alkaline lignin in a MAD in the presence of FA and ethanol to produce bio-oil and phenolic monomers. They were able to determine that FA acted as both catalyst and in situ hydrogen donor. Zhou and co-workers [114] collected more products under acidic extraction conditions compared to neutral or basic conditions, producing bio-oil products with improved quality. This was attributed to pH adjustment-induced ionisation of solutes, which improved the affinity between the solutes and the associated extraction solvents used. It was also revealed that bio-oil derived from de-alkaline lignin had a lower average molecular weight compared to alkaline lignin-based bio-oil. The alkaline compounds in the alkaline lignin likely neutralised some of the FA catalyst, causing a decreased degree of depolymerisation with the alkaline lignin. Numerous research reports show FA used in different lignin systems [115–118].

Methanol has been observed to participate in esterification reactions with acidic lignin fragments forming methyl [95,113,119] or alkyl-substituted phenols as well as promoting demethoxylation of methoxy side chains [108]. In an MW-assisted approach, several alcohols were compared, including methanol and ethanol. Methanol was determined to be a better non-water solvent because of its good hydrogen-donating abilities coupled with good lignin solubility. It improved the liquid product yield and decreased molecular weights of lignin fragments, seemingly due to its higher polarity [119]. By contrast, Cederholm et al. [17] suggested that ethanol was a better solvent than methanol. The authors asserted that ethanol was a better capping agent that could scavenge reactive free radicals. They also suggested ethanol’s greater alkylation prowess compared to methanol, suggesting that O-ethylation is more likely than O-methylation. This alkylation decreased the phenolic OH groups and stabilised the fragments produced in the depolymerisation reaction [120]. This highlights some of the challenges associated with lignin depolymerisation studies whereby direct comparisons are often difficult to make due to subtle differences in variables used in studies conducted.

Furthermore, when compared to ethanol, methanol could oxidise to formaldehyde, which was likely to cause oligomerisation with phenolic intermediates in the reaction mixture, similar to phenol–formaldehyde resins (resoles and novolacs) (Scheme 1) [121]. Ethanol’s good capping abilities appeared to scavenge reactive formaldehyde intermediates and other depolymerised monomer species, which could have contributed to ethanol being the better HDS in terms of the product yield [121].

Formation of resoles and novolacs from formaldehyde and phenol.

As a hydrogen donor solvent, EG has a high loss tangent, and it effectively absorbs MWs; however, at high temperatures, the solvent tends to become transparent to MWs, requiring more MW power to maintain the temperature of the setup. EG showed inordinate efficiency in terms of conversion yield when it was used in the liquefaction of empty fruit bunches, as a result of its high dipole moment [100,122].

Tetralin is converted into naphthalene after dehydrogenation to release atomic hydrogen [101,118,123,124] and produces good yields of bio-oil as well, although its use in lignin studies was infrequent. As it is not a renewable HDS, its successful application in sustainable HDS-mediated solvolysis is not guaranteed.

Following sound circular bio-economy guidelines, HDS should ideally be green solvents, which are easily generated from renewable sources such as biomass and preferably come from the bio-refinery itself to reduce the logistical challenges involved in ferrying raw materials from afar, aside from the associated carbon emissions involved. In short, the incorporation of HDS into the lignin depolymerisation process would result in a process that is cheaper and safer, given the risk of an explosion associated with molecular hydrogen, making HDS-assisted lignin depolymerisations more practical [14,95,109,125]. Recent reports have proposed hemicellulose as a hydrogen donor for the reductive cleavage of the β–O–4 ether bond [5,126], a development which would make the lignin solvolysis process even more sustainable as the biomass would essentially self-stabilise during liquefaction of biomass to produce aromatic compounds.

6 Lignin depolymerisation reaction mechanisms in HDS under MW-assisted heating

Lignin ether and C–C bonds typically fragment via heterolytic cleavage or homolytic cleavage mechanisms. This produces a plethora of intermediates that are stabilised by hydrogen species or fragments derived from HDS used in reactions, or even other lignin fragments, which may result in undesirable and more complicated condensed structures. The activation of ether bonds is pivotal, especially since they are the most abundant linkages for maximum lignin depolymerisation, although other ether bonds such as 4–O–5 and dibenzodioxocin units are also present [24,127]. C–C bonds may also be broken, as they have a higher bond dissociation energy (BDE) and are unfavourable compared to weaker β–O–4 bonds. The solvolysis mechanisms of lignin depolymerisation can be grouped into heterolytic and homolytic cleavage mechanisms.

6.1 Heterolytic cleavage

In this mechanism, a bond is broken unevenly, resulting in two oppositely charged species when electrons are transferred from one bonding atom to the other.

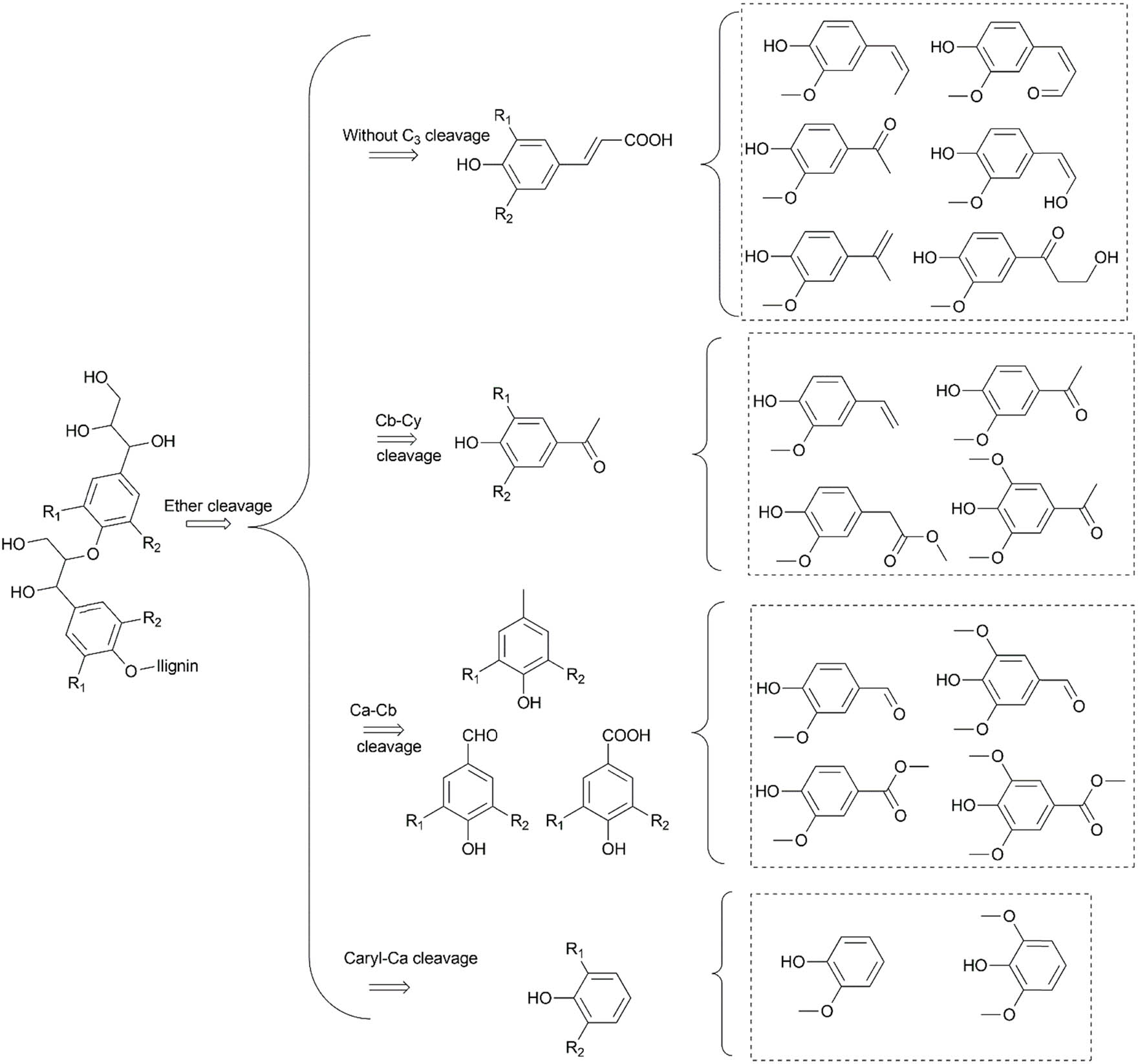

A general overview of the cleavage of lignin into various fragments is shown in Scheme 2. The products depend on the location of the bond to be cleaved. The ether bond Cβ–O is often preferred over Cα–Cβ because of a lower BDE. Nevertheless, the cleavage of Cα–Cβ or Cα–OH or H abstractions forming the Cα═Cβ double bond is also possible [113,128–130]. The cleavage of C–C bonds was observed to be greater in a MW-assisted reaction, relative to conventional heating. In this reaction, the monophenolic compound yield was observed to increase from 0.92 to 13.61% under MW irradiation [64]. The role of MW-derived non-thermal effects in the form of a surge in the pre-exponential factor and a decrease of the activation energy based on the Arrhenius equation was indicated, which promoted the cleavage of C–C bonds, including Caryl–Cα bonds [24] Liu et al. [106] also confirmed the cleavage of inter-unit aryl ether linkages on Cα or Cβ atoms of the aliphatic side chain of oligomers, which led to an abundance of aldehyde- and ketone-type aromatic compounds. This was achieved without the need for a catalyst, ensuring the green depolymerisation of lignin. In a DFT study, Li and Vlachos predicted that increasing the methoxy groups on the aromatic structure overall decreased the C–C barrier making 5-5′ linkages, which are the strongest bonds in lignin, easier to cleave [131].

Lignin depolymerisation into aromatic products via the cleavage of ether and C–C bonds.

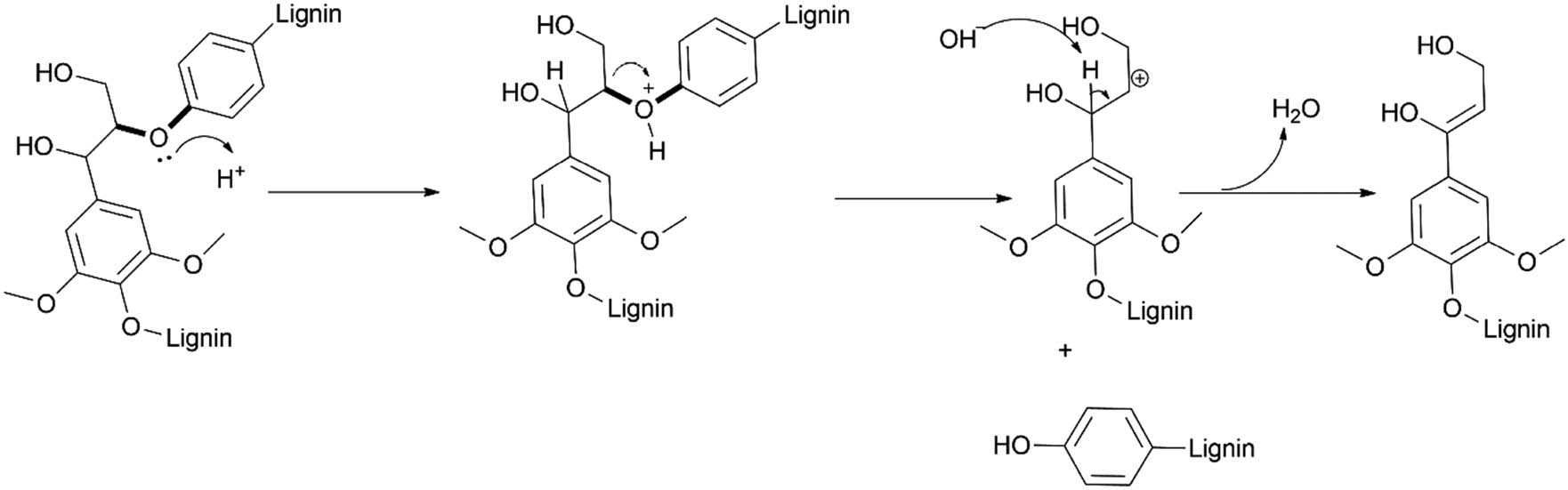

The mechanism of the cleavage of the β–O–4 linkage, as the most common moiety in lignin, is the focal point of most mechanisms postulated thus far (Scheme 3). The activation of the ether bond is pivotal in this mechanism. This is achieved via a fast and reversible protonation of the ether bonds, forming an oxonium ion, making it electrophilic, and thereafter a base. Typically, the alkoxyl base of the alcohol used or even water serves as a nucleophile attacking the electrophilic carbon atom adjacent to the ether bond [90]. Subsequently, electrons move towards the oxonium ions creating a good leaving group and neutral hydroxyl group by cleaving the C–O bond. The produced oligomers may then undergo subsequent hydrolysis into variations of H-, G-, and S-type units [30,106,109,132,133]. This secondary fragmentation-hydrolysis mechanism was postulated by Song et al. [109] and corroborated based on an observed inverse correlation between particular oligomers and monomers by Zhou et al. [134] and Liu et al. [106]. This confirmed that oligomers were subsequently cleaved into smaller monomer fragments after the initial cleavage into oligomers [134], although oligomers could also react with each other to produce condensed structures, which is undesirable in depolymerisation reactions. This re-polymerisation phenomenon is dependent on several factors, including temperature, catalyst, and solvents used [134].

Mechanism of the cleavage of a β–O–4 bond forming an alkenyl product.

Deliberate alteration of lignin before depolymerisation has also been developed to improve solvolysis and the selectivity of resultant monolignol products [15,135]. Zhu et al. [15] used MW irradiation in a two-step depolymerisation process to efficiently achieve a 98% methylation degree of the benzylic alcohol after just 2 min.

This methylation improved the reactivity and cleavage of β–O–4 by 55.9% as well as product selectivity after using methanol and a Pd/C catalyst. Mark’s group acetylated both primary and secondary hydroxyl groups in the α and γ positions in β–O–4 lignin environment to ultimately promote the methylation process, which in turn improved the subsequent cleavage of β–O–4 bonds [136]. Using aspen lignin, Rahimi et al. [44] developed a strategy for the chemoselective oxidation of the benzylic OH on Cα to a ketone first, before depolymerisation was conducted. Subsequently, an FA/sodium formate combination was used in the ensuing depolymerisation. The authors speculated that the benzylic carbonyl group polarised the Cβ–H bond of the adjacent carbon, which effectively lowered the energy barrier for the rate-limiting elimination reaction of H abstraction by the base. A result of the elevated acidity of the Cβ–H, combined with orbital overlap between the existing C═O π system and the developing π system of the unsaturated bond formed as the H is abstracted.

After the initial oxidation of the Cα alcohol to a ketone (1), FA acted as a Brønsted acid catalyst and induced the formylation–dehydrogenation–hydrolysis reaction mechanism, as shown in Scheme 4. In this mechanism, the FA reacted in what appeared to be an esterification reaction with the Cγ alcohol in a formylation reaction (2). Thereafter, the base (which could be formate in this instance) abstracted H from the Cβ, while simultaneously a double bond was formed between Cβ and Cγ atoms; meanwhile, the Cγ–O bond broke as FA was eliminated after the abstraction of the subtle differences in the studies which appear to have produced these differences are notable. Rahimi et al. used acid and a conjugate base combination (CH3COOH/CH3COO−), whereby the formate ion likely acted as a base to abstract the H (3), whereas Oregui-Bengoechea et al. showed the use of an alkoxide as the base which abstracted the H in the elimination step (13) to form methanol in a reaction catalysed by the NiMo/alumina catalyst. Both authors agreed about the dual role played by FA as a hydrogen donor and a catalyst [44,112], leading to both depolymerisation and stabilisation of lignin fragments [114].

The role of FA in the cleavage of lignin: (a) the formylation–dehydrogenation–hydrolysis mechanism, (b) the formylation–dehydrogenation–hydrogenolysis mechanism, and (c) the formylation mechanism of FA.

Part (c) in Scheme 4 portrays the formylation mechanism steps as computed by Qu et al. [135] in a DFT mechanistic study. The attack was carried out using two HCOOH molecules on the Cγ hydroxyl group forming a gem-diol intermediate, possibly assisted by hydrogen bonding. One FA molecule (Scheme 4, in green) acted as an electrophile while the other (in red) shuttled hydrogen from the Cγ–OH to the carbonyl group of the electrophilic FA molecule attacking the Cγ–OH via its O atom. Thereafter, dehydration of 3 generates the formylation product via another H shuttle, which is known to reduce the energy barrier for dehydration to occur. Water can also act as a hydrogen shuttle; however, it is a weaker Brønsted acid than FA and is unlikely to have been involved in this case [135]. Oxalic acid has also been studied to have the potential to take part in formylation-type reactions [137].

Zhu et al. [24] reported the collusion of MW-assisted heating and ferric sulphate in the catalytic cleavage of Cα–Cβ to a 96.3% bond cleavage degree using organosolv lignin in methanol (Scheme 5). The choice of HDS was peculiar given the general low solubility of both the hydrophobic lignin and the ferric sulphate salt in methanol. Nevertheless, the authors claimed that the reaction was more facile under MW-assisted heating than under conventional heating and overall the MW assistance improved the yield of aromatic monomers. The cleavage of the Cα–Cβ bonds was proven based on the presence of Cα–Cβ cleavage products and the absence of anticipated β–O–4 bond cleavage products. Unfortunately, the authors did not give any particular insight into why the β–O–4 with a lower BDE was not preferentially cleaved rather than the Cα–Cβ bond with a higher BDE. It would be interesting if the same protocol could be applied to an α–O–4 to break the Cα–Cβ bond.

The reaction mechanisms involved in the cleavage of C–C bonds. (a) The depolymerisation mechanism of lignin via the etherification of Cα hydroxyl group using methanol in ferric sulphate. (b) The hydrolysis mechanism of C═C cleavage in a vinyl ether into alcohol.

The researchers suggested a reaction mechanism that proceeded via initial etherification of the Cα-hydroxyl group facilitated by H+ and the methanol solvent conditions, as suggested by others [112], rather than merely its typical hydrogen donor role. Thereafter, water was involved in shuttling hydrogen from Cβ to the methoxide substituent re-forming the methanol used in etherification. This elimination of methanol and water simultaneously forms an alkenyl product from the elimination, and thereafter the Cα–Cβ bond is cleaved.

DFT calculations predicted that the yield of the cleavage of the phenolated dimer was much greater than the non-phenolated dimer [24] because the phenolic dimer was more thermodynamically favourable to form the alkenyl precursor, which then cleaved into the final products. MW heating also vastly improved the selective cleavage of the Cα–Cβ bond in lignin and contributed to a narrow distribution of aromatic monomers. It was unclear how the cleavage of the Cα–Cβ proceeded from the mechanism described, or the fate of the Cβ atom after step 6. Given that the molecule formed after step 5 is an enol ether (specifically a vinyl ether), the H+-mediated hydrolysis could have produced an aldehyde and an alcohol instead, as shown in step 8, similar to step 5 of part (a), Scheme 5. The H-mediated hydrolysis mechanism of vinyl ethers is shown in detail in part (b) for further elaboration. Sturgeon et al. [127] created a reaction mechanism based on DFT calculations showing the vinyl ether hydrolysis mechanism (Scheme 6).

![Scheme 6

Vinyl ether cleavage into alcohol and carbonyl compounds. Adapted from the study of Sturgeon et al. [127].](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2023-0154/asset/graphic/j_gps-2023-0154_fig_016.jpg)

Vinyl ether cleavage into alcohol and carbonyl compounds. Adapted from the study of Sturgeon et al. [127].

Dhar and Vinu [93] observed the incorporation of the HDS solvent used into the lignin fragments during the cleavage using EG as a solvent [93], and the suggested reaction mechanism is shown in Scheme 7. It involved EG taking part in the etherification-type reaction with the Cα–OH, similar to using methanol as portrayed by Zhu et al. [24] in Scheme 5, inset (a), which resulted in two possible cleavage routes, either via the Cα–Cβ cleavage route or the β–O–4 route. In the former reaction, dehydration results in an aldehyde of the carbonyl group forming on the Cα carbon (step 6) after a Cα–Cβ bond cleavage, presumably after etherification. In the β–O–4 bond cleavage route, a ketone is produced instead as the Cα–Cβ bond is still intact. The carbonyl group also forms on Cα, as with the Cα–Cβ bond cleavage route. The authors also presented the formation of a diether intermediate formed from the incorporation of the EG into the lignin. EG may also form in situ diol-stabilised C-3 ketals and C-2 acetals as products, using the carbonyl compounds product (Scheme 8) [138].

Mechanism of C–C and β–O–4 bond cleavage using EG.

Formation of diol-stabilised ketal and acetal using EG.

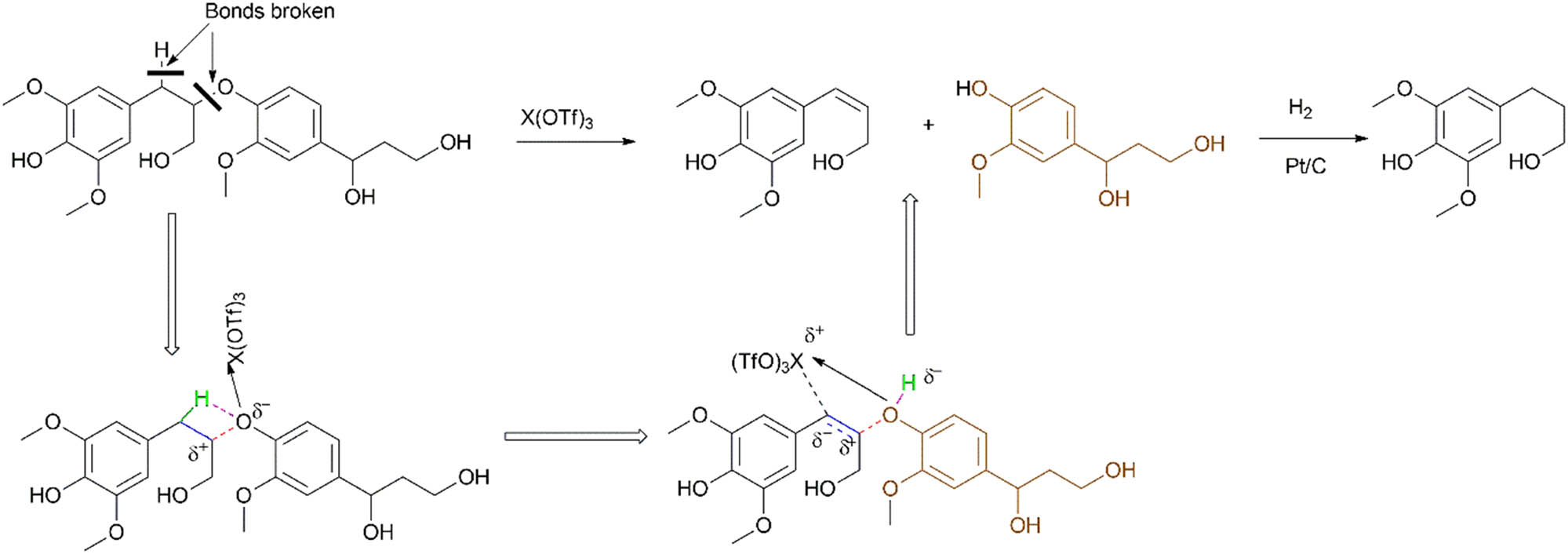

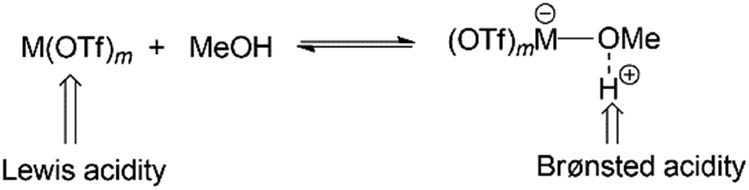

Liu et al. [41] used a tandem system with metal triflates and a Pt catalyst in methanol solvent; their proposed mechanism is based on earlier work by Assary et al. [139], and the metal triflates participated in β–O–4 scission as Lewis acids (Scheme 9). The Cα–H and Cβ–O bonds were cleaved and the H was transferred from the Cα to the O of the β–O–4 bond resulting in an alkenol. This is due to metal triflates that have Lewis acid assisted-Bronsted acidity derived from the complexation of the metal centre with a protic solvent (Scheme 10) [140]. The Bronsted acid’s acidity likely improved the cleavage of the β–O–4 bond using H+ as observed by the Fe(OTf)3 complex that had the greatest acidity and afforded the highest yield.

Mechanism of lignin depolymerisation using triflate-assisted β–O–4 bond cleavage.

Lewis-assisted Bronsted acidity.

The hydrolysis of the metal chloride catalyst into in situ Brønsted acid HCl was postulated when metallic chloride catalysts (MgCl2, AlCl3, FeCl3, ZnCl2, and MnCl2) were used. A MW-assisted lignin depolymerisation method was conducted in a FA and hydrochloric acid system under mild conditions (160°C for 30 min) [140]. Previous studies [141–143] demonstrated the depolymerisation activity of Lewis acids once converted into Brønsted acids via a reaction of the Lewis acid with water, or low-molecular-weight alcohol used [144]. Once formed, the Brønsted acid proceeds with the cleavage of the β–O–4 linkage [145], as already discussed (Scheme 3). However, the original purpose of including the HCl as a reactant, as well as how to differentiate the potential effect of the formed HCl from the salts versus the original HCl used as a reactant, was not reported. In addition, the differences in MW absorptivity of the various salts used were not taken into account and could have led to disparities in the observed results.

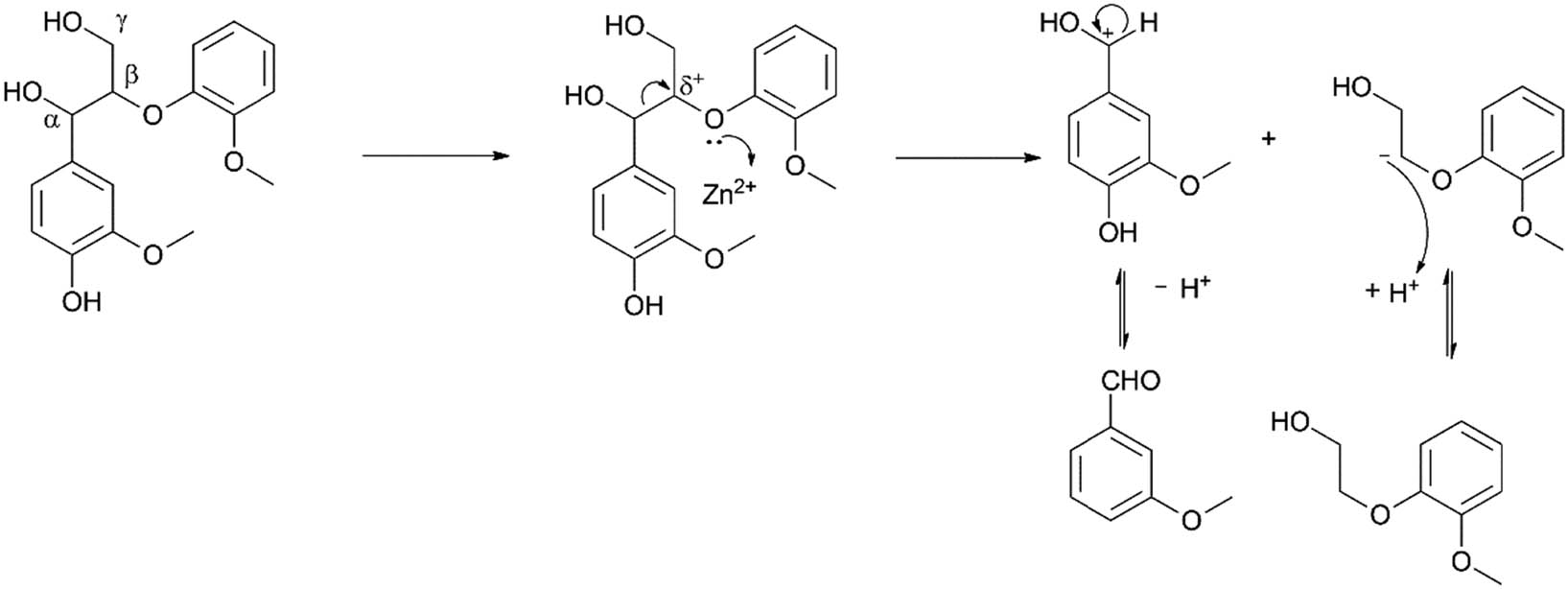

An alternative mechanism was involved in the action of the metal cations present in the solution. Using Zn2+ to illustrate, the cation coordinated with the oxygen atom positioned at β–O–4, which possibly weakened the Cα–Cβ bond (Scheme 11). Shu et al. [146] described the synergistic effects of Pd/C and ZnCl2. The metal cation also interacted as a Lewis acid with ether bonds and promoted their cleavage via hydrogenolysis, with the assistance of a Pd/C catalyst (Scheme 12). Meanwhile, the Cl− weakened the β–O–4 bond by lowering its dissociation energy. Shao et al. [147] recently corroborated this using a methanol/FA combination with a Pt/C catalyst in synergy with nine different metal chlorides. ZnCl2, CrCl3, and FeCl3 were observed to significantly promote lignin depolymerisation. The authors attributed this to the higher valence of the metal cation, which improved the Lewis acid strength of the metal cation, allowing more acid centres, in turn promoting lignin depolymerisation [147]. Comparing ZnCl2 and zinc acetate, the former was observed to have a higher bio-oil and aromatic monomer yield than the latter, an indication that as a highly electronegative element the Cl− ion was an excellent nucleophile which played a role in β–O–4 cleavage in the depolymerisation process [148,149]. The authors suggested that, overall, both the cation and anion worked in synergy with the Pd/C in the depolymerisation reaction.

The cleavage of β–O–4 bond using Zn2+ as a Lewis acid to weaken the Cα–Cβ bond.

![Scheme 12

Synergistic effect of metal chlorides and the Pd/C catalyst in lignin depolymerisation. Adapted from the study of Zhang et al. [145].](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2023-0154/asset/graphic/j_gps-2023-0154_fig_022.jpg)

Synergistic effect of metal chlorides and the Pd/C catalyst in lignin depolymerisation. Adapted from the study of Zhang et al. [145].

Parallel to heterolytic and homolytic cleavage occurring between lignin units, side chain cleavage methyl transfer, demethylation, and hydrolysis of methoxyl groups may also occur and, at higher reaction severity, alter the composition of phenolic products [150]. In particular, side-chain cleavage, methyl transfer, and demethylation reaction of phenolic compounds were also observed to occur during lignin depolymerisation producing a significant proportion of phenols, a phenomenon that was touted to enable selectivity of aromatic products, rather than a myriad of products that induce separation challenges as researchers are currently faced with.

This lowers the dissociation energy of the ether bond, subsequently allowing the weakened O–C bond to cleave heterolytically. Thereafter, the positively charged methyl group can be transferred to the aromatic ring, followed by the formation of the methyl-catechol (Scheme 13). Shu et al. [146] obtained the largest yield using a CrCl3 catalyst, probably a result of a strong Lewis acidity, which encouraged demethoxylation and alkylation, converting the guaiacols into phenols (Scheme 13) [146].

![Scheme 13

Demethoxylation mechanism and conversion of guaiacol into catechol. Adapted from the study of Zhang et al. [145].](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2023-0154/asset/graphic/j_gps-2023-0154_fig_023.jpg)

Demethoxylation mechanism and conversion of guaiacol into catechol. Adapted from the study of Zhang et al. [145].

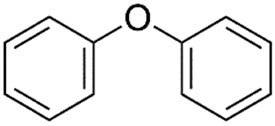

Most reaction mechanisms focused on the β–O–4 linkage; however, recently Polidoro et al. [151] reported a catalytic transfer hydrogenation (CTH) mechanism involving the α–O–4 linkage in benzene phenyl ether (BPE). In this reaction, a Ru/C catalyst and isopropanol were used as HDS (Scheme 14). The proposed mechanism proceeded by initial absorption of isopropanol HDS onto the ruthenium catalyst sites using its hydroxyl groups. Thereafter, the transfer of the α-hydrogen atom from the isopropanol to the α-methylene moiety of BPE ensued, which in turn weakened the ether C–O bond, resulting in its cleavage and subsequently the production of the toluene product. The phenol product was later formed after another catalytic transfer of hydrogen. Meanwhile, the isopropanol HDS was converted into acetone after its dehydrogenation. Due to the significant catalytic hydrogenation efficiency of the Ru catalyst, undesirable cyclohexanes were also observed from the excessive hydrogenation of the aromatics products initially produced.

![Scheme 14

The catalytic transfer hydrogenation cleavage mechanism of an α–O–4 linkage in benzene phenyl ether using isopropanol as HDS, in turn produces aromatic products, which can undergo hydrogenation into cyclohexanes. Adapted from the study of Polidoro et al. [151].](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2023-0154/asset/graphic/j_gps-2023-0154_fig_024.jpg)

The catalytic transfer hydrogenation cleavage mechanism of an α–O–4 linkage in benzene phenyl ether using isopropanol as HDS, in turn produces aromatic products, which can undergo hydrogenation into cyclohexanes. Adapted from the study of Polidoro et al. [151].

The mechanism for the 4–O–5 linkage in the diphenyl ether (DPE) reaction conducted (Figure 10) was not reported. However, similar products to BPE were observed with DPE, namely benzene, phenol, and cyclohexanol; it is therefore probable that DPE followed the same mechanism as BPE.

DPE.

Although researchers were able to provide insights into the proposed cleavage of α–O–4 and 4–O–5 using model compounds, the proposed mechanism cannot simply be extrapolated to actual lignin studies given the structural complexity of lignin and other associated kinetic considerations.

The substrate/catalyst ratios usually used with expensive commercial catalysts were typically 1:1, which appears untenable for the potential scale-up of the lignin depolymerisation process; Polidoro et al. [151] used a 1:2 ratio. Although it is noteworthy that they successfully recovered and recycled the catalyst six times without any observed loss in the catalytic activity, we propose a more prudent approach in designing catalysts from abundant and cheaper earth metals, oxides, and their salts, given that they have shown some decent catalytic activity [145]. Particular focus should be placed on those catalysts with magnetic properties, which enable easy recovery from the reaction mixture by magnetic means, for example, magnetite, Fe3O4. Catalysts fabricated from the biomass-derived catalyst support would also add to the overall sustainability of the process. The coupling of MW depolymerisation with other means of lignin depolymerisation such as photocatalysis depolymerisation [12,152] could also help to improve the yield and selectivity of catalysts in MAD by introducing new favourable reaction mechanisms, which are currently unknown.

Virtually, all the precious metal catalysts used in MAD were supported on an activated carbon (AC) matrix. Some catalysts and AC itself were good MW absorbers capable of inducing hotspots in the reaction system [153]. AC also played a role in product yield and selectivity [153,154]. However, researchers appear to omit catalyst-free AC in control experiments, which would better enable a fair comparison of MAD catalysed and uncatalysed reactions. We speculate that some effects attributed to solely the catalysts, including some reaction mechanisms, could have been the combined effects of the AC support and the catalysts.

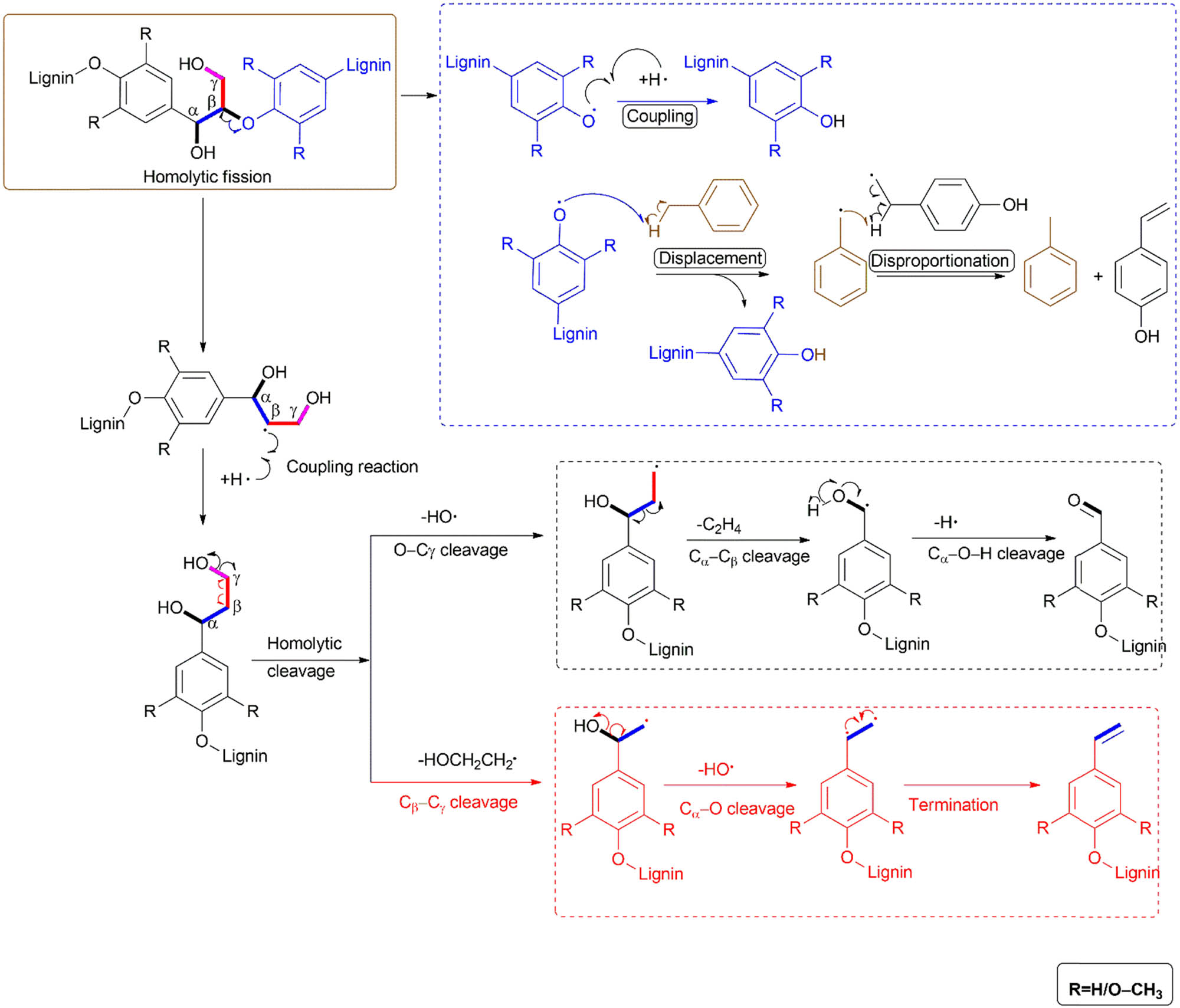

6.2 Homolytic cleavage

In this type of reaction, various types of bonds in lignin and the HDS fragment equally produce free radicals, rather than form ions, as with heterolytic cleavage. The H radicals are often used to stabilise the radical fragments from lignin depolymerisation and hopefully curtail free radical polymerisation into biochar, which is unwanted, unlike in heterolytic cleavage where H+ is often involved in bond cleavage. Given that the original formation of lignin in plants is believed to be a bio-synthesis process that occurs via oxidative radical–radical coupling of monolignols [155], it is plausible that lignin’s degradation is also a radical-initiated mechanism. Alternatively, perhaps both heterolytic and homolytic mechanisms are simultaneously involved in the same vessel during lignin degradation (Scheme 15).

A summary of selected homolytic depolymerisation reactions of lignin.

A summary of some free radical-mediated reactions is shown in Scheme 14, stemming from a β–O–4 homolytic fission from the cracking of the Cβ–O bond into free radicals. As reactive species, these radicals then undergo various reactions until eventual termination. The lignin fragments could eventually couple with a free radical, abstract an H radical from other lignin fragments to form the oligomers or compounds, which are found in the depolymerisation product, and can fragment further into more aromatic products. The main depolymerisation reactions of lignin are summarised in Table 1.

A summary of selected MAD reactions

| Lignin source | Reaction conditions | Prominent monomers in products | HDS | Catalyst(s) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Biolignin, eucalyptus lignin, hardwood lignin | L/S = 12.5, 400 W, 180°C, 60 min | • Syringol | FA | NiO/H-ZSM-5 | [46] |

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Syringic acid | |||||

| • Acetosyringone | |||||

| • Olive tree pruning waste lignin | L/S ratio 25, 400 W, 140°C, 30 min | • Syringol | FA | Ni/Al-SBA-15 | [22] |

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Vanillin | |||||

| • Black liquor lignin | 600 W, 130°C, 30 min | • Vanillin | FA | HUSY catalyst | [30] |

| • Ethanone,1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) | |||||

| • 2-Propanone,1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) | |||||

| • Phenylacetylformic acid,4-hydroxy-3-methoxy | |||||

| • Ethanone,1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-methoxyphenyl) | |||||

| • Dibutylphthalate | |||||

| • Olive tree lignin | L/S = 25, 400 W, 140°C, 30 min | • Mesitol | FA | Ni, Ru, Pd, Pt NPs supported on Al-SBA-15 | [102] |

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Vanillin | |||||

| • Mesitol | |||||

| • 2,3,6-Trimethylphenol | |||||

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Alkaline lignin (corn cob) | L/S = 24, 400 W, 120–180°C, 15–45 min | • 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran | Methanol-FA | None | [113] |

| • Vanillin | |||||

| • p-Coumaric acid | |||||

| • 2-Propenoic acid, | |||||

| • 3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) | |||||

| • Benzaldehyde | |||||

| • Ethanone,1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)- | |||||

| • 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamaldehyde | |||||

| • Alkaline lignin | 1 g lignin, 1 mmol metal chloride, 0.2 g Pt/C, 20 mL MeOH, 4 g FA, 400 W, 140–180°C, 15–45 min | • 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran | Methanol/FA | Pt/C and metal chlorides | [147] |

| • Phenol | |||||

| • Phenol, 4-ethyl- | |||||

| • 2-Propenoic acid, 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-, methyl ester | |||||

| • Phenol, 2-methoxy- | |||||

| • 2-Propenoic acid, 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)- | |||||

| • Ethanol organosolv lignin (bamboo) | L/S = 24, 80 W, 100–200°C, 20–60 min | • Guaiacol | Ethanol/FA | None | [120] |

| • Vanillin | |||||

| • Syringol | |||||

| • Homovanillyl alcohol | |||||

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Acetosyringone | |||||

| • Desaspidinol | |||||

| • Ethanol organosolv lignin (olive tree pruning) | L/S = 12.5 30 min, 150°C | • Syringol | Tetralinisopropanol, glycerol, and FA | NiAl-SBA15 | [22] |

| • Vanillin and | |||||

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Southern pine sawdust | L/S = 6, 15 min at 180°C, 700 W | • 2-Methoxy-4-propyl-phenol and | Methanol | H2SO4 | [90] |

| • 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-benzoic acid methyl ester | |||||

| • Alkaline lignin | L/S = 40, 400 W, 100–160°C,40–80 min | • p-Hydroxyacetophenone | Methanol | CuNiAl | [134] |

| • Guaiacol | |||||

| • p-Hydroxyacetovanillon | |||||

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Organosolv lignin (eucalyptus) | 160°C, 30 min | • Vanillin | Methanol/water | Fe2(SO4)3 | [24] |

| • Syringaldehyde | |||||

| • Methyl vanillate | |||||

| • Methyl syringate | |||||

| • Ethanosolv lignin | L/S = 24:1, 100 W, 160°C, 30 min | • N/D | Methanol | H2SO4 | [156] |

| • Black liquor lignin | 120°C, 30 min | • Ethanone,1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) | Isopropanol | None | [106] |

| • Ethanone, 1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy phenyl) | |||||

| • Wheat straw alkaline lignin | L/S = 20, 300 W, 120°C, 40 min | • 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid | Phenol/EG | H2SO4 | [64] |

| • Phenol | |||||

| • 2-Methoxyphenol | |||||

| • 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol | |||||

| • 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid | |||||

| • Alkaline lignin | L/S = 50, 600 W, 100–140°C, 20–80 min | • Syringaldehyde | EG, DMSO, DMF | None | [93] |

| • Acetosyringone | |||||

| • Guaiacol | |||||

| • Anisole |

Key: L/S = liquid to solid ratio, N/D = no data given.

7 Conclusions and future prospects

In general, β–O–4 linkages are the focal point of most lignin depolymerisation studies due to their abundance and low BDE. Most reaction mechanisms of lignin depolymerisation involve the cleavage of this linkage. The Cα and its hydroxyl group also appeared to be involved in a significant number of heterolytic mechanisms. Modification of the Cα–OH by oxidation to a ketone was observed to improve subsequent depolymerisation. The presence of OH on the phenyl ring appeared important enough to improve the reactivity of the β–O–4 linkage, thereby causing an unzipping mechanism starting from the terminal unit with phenolic ends of branched, polymer chains inward toward the core of the polymer. Metal cations also play significant roles in cleaving β–O–4 by acting as Lewis acids using their d-orbitals to accommodate the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atom of β–O–4.

While most research appeared to focus on β–O–4 bond cleavage, C–C bonds were also reportedly cleaved under MW-assisted conditions, resulting in uniquely Cα–Cβ cleavage type products. The reaction mechanism is not clear, however, opening speculation as to either a vinyl ether hydrolysis or via homolytic fission mechanism.

Reaction mechanisms on the cleavage of α–O–4 linkages using benzene phenyl ether have recently been proposed. The reaction pathway was proposed to occur via a catalytic hydrogen transfer reaction mechanism between lignin model compounds and the isopropanol HDS in a reaction facilitated by a Ru/C catalyst. We suggest that a similar mechanism likely occurred to cleave the 4–O–5 linkage in the DPE lignin model used in the same study, based on the presence of benzene and phenol in the reaction mixture of DPE.

HDS used by most researchers were either alcohols or carboxylic acids and they seemed to have slightly different roles when applied in lignin depolymerisation. Alcohols mainly played H-donor, etherification, and alkylation roles, which stabilised reactive lignin fragments and prevented condensation, while acids played the roles of hydrogen donation and catalysis based on their Brønsted acid status.

Overall, the most common products reported were syringol, syringaldehyde, vanillin, and guaiacol, while the most common commercial catalysts used to produce high yields were Pt/C, Pd/C, and Ru/C. Unfortunately, apart from being expensive precious metals, these catalysts are also capable of inducing hydrogenation of the aromatic rings to cyclohexane, which is undesirable in the production of aromatics. Using cheaper earth-abundant metal catalysts with relatively good yields and selectivity has more favourable process economics to potential biorefineries of the future, and some reports demonstrated MAD successfully conducted in catalyst-free HDS, which is even more favourable.

In catalysed MAD, using AC support, researchers appeared to ignore the potential effect of the AC on which their commercial catalysts were supported. This omission was surprising given that AC is a good MW absorber capable of inducing hotspots in the vessel and contributing to the yield and selectivity of products. We recommend the inclusion of catalyst-free AC in control experiments to negate the effect of the AC support used in catalysts, rather than omit the AC altogether in the control experiments. Such oversight could result in unfair comparisons and incorrect deductions.

The ideal MAD catalyst with both high yield and excellent selectivity has proven elusive so far. Using successive MAD catalytic steps with different catalysts and taking advantage of their different catalytic properties could aid in this regard. The successive application of MWs and photocatalysis to harness the full potential of both techniques is also recommended.

Based on the reports, the controversial “non-thermal effects” were not always evident from the reaction mechanisms studied, rather the effects appeared thermally related. MW-assisted reactions have a distinct advantage over conventional heating as a result of the volumetric heating pattern which is more efficient resulting in a high heating rate, a property linked to several variables on the Arrhenius equation to explain the improvement in MW-assisted reactions. The reaction mechanisms described did not appear to be specific to MW-assisted reaction in most cases for them to be a result of non-thermal effects, rather they appeared to be effects derived from the different heating profiles of MW, which are essentially thermal. The use of polar compounds in the form of alcohols and carboxylic acids, and ionic substances such as metallic salts are convenient in MW-assisted reactions based on the two main heating mechanisms of MW, namely dipolar polarisation and ionic conduction. However, the proper comparison of MW-assisted and conventional heating sources is also complicated by changes in the dielectric properties of solvents with temperature, which changes the interaction of the MW energy and the solvent resulting in disparities in heating rates.

Computational studies using DFT calculations proved extremely useful in determining feasible pathways to interpret the reactivity difference. This enabled the completion of mechanistic steps for catalysis showing the energy profiles of proposed pathways’ however, DFT showed relative stabilities (thermodynamics) of species and cannot be used to address the kinetics of proposed intermediates. Incorporating isotopic studies for mechanism determination could improve the determination of reaction mechanisms [109,157]. Some mechanisms proposed were deduced from aromatic reaction products and sometimes appeared speculative and ambiguous.

With the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), the synergy of AI and computational chemistry could ultimately improve the determination of mechanisms in lignin depolymerisation studies. We propose that AI and computational chemistry combined could become the solution to the longstanding challenge of determining the ideal parameters and catalysts for the best yield and selectivity in MAD of lignin.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, for their support.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

-

Author contributions: Emmanuel Mkumbuzi: conceptualisation, visualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing; Michael Nivendran Pillay: writing – review &editing; Werner Ewald van Zyl: conceptualisation, writing – review and editing, supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Frosch RA, Gallopoulos NE. Strategies for Manufacturing the impact of industry on the environment. Sci Am. 1989;261(September):144–53. 10.1038/scientificamerican0989-144.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Carus M, Dammer L. The Circular Bioeconomy - Concepts, Opportunities, and Limitations. Ind Biotechnol. 2018;14(2):83–91. 10.1089/ind.2018.29121.mca.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kirchherr J, Piscicelli L, Bour R, Kostense-Smitb E, Mullerb J, Huibrechtse-Truijensb A, et al. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence From the European Union (EU. Ecol Econ. 2018;150(April):264–72. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.028.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Toukoniitty B, Mikkola JP, Murzin DY, Salmi T. Utilization of electromagnetic and acoustic irradiation in enhancing heterogeneous catalytic reactions. Appl Catal A Gen. 2005;279(1–2):1–22. 10.1016/j.apcata.2004.10.044.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Liu X, Bouxin FP, Fan J, Budarin VL, Hu C, Clark JH. Microwave-assisted catalytic depolymerization of lignin from birch sawdust to produce phenolic monomers utilizing a hydrogen-free strategy. J Hazard Mater. 2021;402(July 2020):123490. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123490.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ubando AT, Felix CB, Chen WH. Biorefineries in circular bioeconomy: A comprehensive review. Bioresour Technol. 2020;299(November 2019):122585. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Cao Y, Chen SS, Tsang DCW, Clark JH, Budarin VL, Hu C, et al. Microwave-assisted depolymerization of various types of waste lignins over two-dimensional CuO/BCN catalysts. Green Chem. 2020;22(3):725–36.10.1039/C9GC03553BSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Liu G, Zhao Y, Guo J. High selectively catalytic conversion of lignin-based phenols into para-/m-xylene over Pt/HZSM-5. Catalysts. 2016;6(2):19. 10.3390/catal6020019.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ragauskas AJ, Ragauskas AJ, Williams CK, Davison BH, Britovsek G, Cairney J, et al. The path forward for biofuels. Science. 2013;311(2006):484. 10.1126/science.1114736.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Mota IF, da Silva Burgal J, Antunes F, Pintado ME, Costa PS. High value-added lignin extracts from sugarcane by-products. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;230(September 2022):123144. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123144.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Yu IKM, Chen H, Abeln F, Auta H, Fan J, Budarin VL, et al. Chemicals from lignocellulosic biomass: A critical comparison between biochemical, microwave and thermochemical conversion methods. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2020;0(0):1–54. 10.1080/10643389.2020.1753632.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tan X, Wu H, Zhang H, Li H, Yang S. Relay catalysis of Pt single atoms and nanoclusters enables alkyl/aryl C-O bond scission for oriented lignin upgrading and N-functionalization. Chem Eng J. 2023;462(March):11–6. 10.1016/j.cej.2023.142225.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Schutyser W, Renders T, Van Den Bosch S, Koelewijn SF, Beckham GT, Sels BF. Chemicals from lignin: An interplay of lignocellulose fractionation, depolymerisation, and upgrading. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(3):852–908. 10.1039/c7cs00566k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Galkin MV, Samec JSM. Selective route to 2-propenyl aryls directly from wood by a tandem organosolv and palladium-catalysed transfer hydrogenolysis. ChemSusChem. 2014;7(8):2154–8. 10.1002/cssc.201402017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Zhu G, Qiu X, Zhao Y, Qian Y, Pang Y, Ouyang X. Depolymerization of lignin by microwave-assisted methylation of benzylic alcohols. Bioresour Technol. 2016;218:718–22. 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.07.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Kloekhorst A, Shen Y, Yie Y, Fang M, Heeres HJ. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation and hydrocracking of Alcell® lignin in alcohol/formic acid mixtures using a Ru/C catalyst. Biomass Bioenergy. 2015;80(0):147–61. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.04.039.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Cederholm L, Xu Y, Tagami A, Sevastyanova O, Odelius K, Hakkarainen M. Microwave processing of lignin in green solvents: A high-yield process to narrow-dispersity oligomers. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;145(January):112152. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112152.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Nde DB, Barekati-Goudarzi M, Muley PD, Khachatryan L, Boldor D. Microwave-assisted lignin liquefaction in hydrazine and ethylene glycol: Reaction pathways via response surface methodology. Sustain Mater Technol. 2021;27:e00245. 10.1016/j.susmat.2020.e00245.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Motasemi F, Ani FN. A review on microwave-assisted production of biodiesel. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2012;16(7):4719–33. 10.1016/j.rser.2012.03.069.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Song LH. Facile preparation of biodiesel using microwave heating. Adv Mater Res. 2013;634–638(1):764–7. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.634-638.764.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zakzeski J, Bruijnincx PCA, Jongerius AL, Weckhuysen BM. The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem Rev. 2010;110(6):3552–99. 10.1021/cr900354u.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Toledano A, Serrano L, Labidi J, Pineda A, Balu AM, Luque R. Heterogeneously Catalysed Mild Hydrogenolytic Depolymerisation of Lignin Under Microwave Irradiation with Hydrogen-Donating Solvents. ChemCatChem. 2013;5(4):977–85. 10.1002/cctc.201200616.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Huang X, Korányi TI, Boot MD, Hensen EJM. Catalytic depolymerization of lignin in supercritical ethanol. ChemSusChem. 2014;7(8):2276–88. 10.1002/cssc.201402094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Zhu G, Jin D, Zhao L, Ouyang X, Chen C, Qiu X. Microwave-assisted selective cleavage of Cα─Cβ for lignin depolymerization. Fuel Process Technol. 2017;161:155–61. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2017.03.020.Search in Google Scholar

[25] de la Hoz A, Díaz-Ortiz À, Moreno A. Microwaves in organic synthesis. Thermal and non-thermal microwave effects. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34(2):164–78. 10.1039/b411438h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Li H, Qu Y, Yang Y, Chang S, Xu J. Microwave irradiation - A green and efficient way to pretreat biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2016;199:34–41. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Liu X, Feng S, Fang Q, Jiang Z, Hu C. Reductive catalytic fractionation of lignin in birch sawdust to monophenolic compounds with high selectivity. Mol Catal. 2020;495:111164. 10.1016/j.mcat.2020.111164.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Xiao LP, Wang S, Li H, Li Z, Shi ZJ, Xiao L, et al. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of lignins into phenolic compounds over carbon nanotube supported molybdenum oxide. ACS Catal. 2017;7(11):7535–42. 10.1021/acscatal.7b02563.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Yunpu W, Leilei D, Liangliang F, Shaoqi S, Yuhuan L, Roger R. Review of microwave-assisted lignin conversion for renewable fuels and chemicals. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2016;119:104–13. 10.1016/j.jaap.2016.03.011.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Shen D, Liu N, Dong C, Xiao R, Gu S. Catalytic solvolysis of lignin with the modified HUSYs in formic acid assisted by microwave heating. Chem Eng J. 2015;270:641–7. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Cao L, Yu IKM, Liu Y, Ruan X, Tsang DCW, Hunt AJ. Bioresource Technology Lignin valorization for the production of renewable chemicals: State-of-the- art review and future prospects. Bioresour Technol. 2018;269:465–75. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.08.065.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Evans RJ, Milne TA, Soltys MN. Direct mass-spectrometric studies of the pyrolysis of carbonaceous fuels. III Primary pyrolysis of lignin. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 1986;9(3):207–36. 10.1016/0165-2370(86)80012-2.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Börcsök Z, Pásztory Z. The role of lignin in wood working processes using elevated temperatures: an abbreviated literature survey. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2021;79(3):511–26. 10.1007/s00107-020-01637-3.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zhou N, Thilakarathna WPDW, He QS, Rupasinghe HPV. A review: depolymerization of lignin to generate high-value bio-products: opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Front Energy Res. 2022;9(January):1–18. 10.3389/fenrg.2021.758744.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Chakar FS, Ragauskas AJ. Review of current and future softwood kraft lignin process chemistry. Ind Crops Prod. 2004;20(2):131–41. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2004.04.016.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Xie X, Goodell B, Zhang D, Nagle DC, Qian Y, Peterson ML, et al. Characterization of carbons derived from cellulose and lignin and their oxidative behavior. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100(5):1797–802. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.09.057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Beste A, Buchanan AC. Computational study of bond dissociation enthalpies for lignin model compounds. Substituent effects in phenethyl phenyl ethers. J Org Chem. 2009;74(7):2837–41. 10.1021/jo9001307.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Xu C, Arancon RAD, Labidi J, Luque R. Lignin depolymerisation strategies: Towards valuable chemicals and fuels. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(22):7485–500. 10.1039/c4cs00235k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Liu X, Jiang Z, Feng S, Zhang H, Li J, Hu C. Catalytic depolymerization of organosolv lignin to phenolic monomers and low molecular weight oligomers. Fuel. 2019;244(December 2018):247–57. 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.01.117.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Wang H, Pang G. Baked bread enhances the immune response and the catabolism in the human body in comparison with steamed bread. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):1–15. 10.3390/nu12010001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Liu X, Bouxin FP, Fan J, Gammons R, Budarin VL, Hu C, et al. Effect of metal triflates on the microwave-assisted catalytic hydrogenolysis of birch wood lignin to monophenolic compounds. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;167(November 2020):113515. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113515.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Wong SS, Shu R, Zhang J, Liu H, Yan N. Downstream processing of lignin derived feedstock into end products. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49(15):5510–60. 10.1039/d0cs00134a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Liu X, Bouxin FP, Fan J, Budarin VL, Hu C, Clark JH. Recent advances in the catalytic depolymerization of lignin towards phenolic chemicals: A review. ChemSusChem. 2020;13(17):4296–317. 10.1002/cssc.202001213.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Rahimi A, Ulbrich A, Coon JJ, Stahl SS. Formic-acid-induced depolymerization of oxidized lignin to aromatics. Nature. 2014;515(7526):249–52. 10.1038/nature13867.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Shu R, Long J, Xu Y, Ma L, Zhang Q, Wang T, et al. Investigation on the structural effect of lignin during the hydrogenolysis process. Bioresour Technol. 2016;200:14–22. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.09.112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Milovanović J, Rajić N, Romero AA, Li H, Shih K, Tschentscher R, et al. insights into the microwave-assisted mild deconstruction of lignin feedstocks using nio-containing zsm-5 zeolites. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4(8):4305–13. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00825.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Shuai L, Amiri MT, Questell-Santiago YM, Héroguel F, Li Y, Kim H, et al. Formaldehyde stabilization facilitates lignin monomer production during biomass depolymerization. Science. 2016;354(6310):329–33. 10.1126/science.aaf7810.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Anderson EM, Stone ML, Katahira R, Reed M, Muchero W, Ramirez KJ, et al. Differences in S/G ratio in natural poplar variants do not predict catalytic depolymerization monomer yields. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–10. 10.1038/s41467-019-09986-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Galkin MV, Samec JSM. Lignin valorization through catalytic lignocellulose fractionation: A fundamental platform for the future biorefinery. ChemSusChem. 2016;9(13):1544–58. 10.1002/cssc.201600237.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Ročnik T, Likozar B, Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek E, Grilc M. Catalytic lignin valorisation by depolymerisation, hydrogenation, demethylation and hydrodeoxygenation: Mechanism, chemical reaction kinetics and transport phenomena. Chem Eng J. 2022;448(2):137309. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.137309.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Derkacheva O, Sukhov D. Investigation of lignins by FTIR spectroscopy. Macromol Symp. 2008;265(1):61–8. 10.1002/masy.200850507.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Cao Y, Chen SS, Zhang S, Ok YS, Matsagar BM, Wu KCW, et al. Advances in lignin valorization towards bio-based chemicals and fuels: Lignin biorefinery. Bioresour Technol. 2019;291(May):121878. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121878.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Pandey MP, Kim CS. Lignin depolymerization and conversion: A review of thermochemical methods. Chem Eng Technol. 2011;34(1):29–41. 10.1002/ceat.201000270.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Zlotorzynski A. The application of microwave radiation to analytical and environmental chemistry. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 1995;25(1):43–76. 10.1080/10408349508050557.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Priecel P, Lopez-Sanchez JA. Advantages and limitations of microwave reactors: from chemical synthesis to the catalytic valorization of biobased chemicals. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(1):3–21. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03286.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Ameta SC, Punjabi PB, Ameta R, Ameta C. Microwave-assisted organic synthesis: a green chemical approach. New York: CRC Press; 2014.10.1201/b17953Search in Google Scholar

[57] Vivas-Castro J, Rueda-Morales G, Ortega-Cervantez G, Moreno-Ruiz L, Ortega-Aviles M, Ortiz-Lopez J. Synthesis of Carbon Nanostructures by Microwave Irradiation. In: Yellampalli S, editor. Carbon Nanotubes - Synthesis, Characterization, Applications. Rijeka: Intech; 2011. p. 47–60.10.5772/17722Search in Google Scholar

[58] Bassyouni FA, Abu-Bakr SM, Rehim MA. Evolution of microwave irradiation and its application in green chemistry and biosciences. Res Chem Intermed. 2012;38(2):283–322. 10.1007/s11164-011-0348-1.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Haque KE. Microwave energy for mineral treatment processes - A brief review. Int J Miner Process. 1999;57(1):1–24. 10.1016/s0301-7516(99)00009-5.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Jacob J. Microwave assisted reactions in organic chemistry: A review of recent advances. Int J Chem. 2012;4(6):29–43. 10.5539/ijc.v4n6p29.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Nayak J, Devi C, Vidyapeeth L. Microwave assisted synthesis: A green chemistry approach. Int Res J Pharm Appl Sci. 2016;3(5):278–85.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Lidstrom P, Tierney J, Wathey B, Westman J. Microwave-assisted organic synthesis-a review. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9225–83. 10.1039/9781782623632-00001.Search in Google Scholar