Abstract

In this article, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF hybrid nanomaterials were synthesized by supporting Zn-based metal–organic framework (Zn-MOF) through the hydrothermal method. X-ray diffractometer, Fourier transform infrared, scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray, N2 physisorption, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and UV-Vis were used to characterize the physical and chemical properties of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanomaterials. The photocatalytic activity of the as-prepared hybrid has been studied over the degradation of rhodamine B (RhB). A catalytic activity of 97.2% was achieved using Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanocomposite with the loading of 0.18 g Bi2O3, after 90 min of exposure to visible light irradiation, and the high photocatalytic performance was mainly associated with the nanorod structures, larger pore size, and broaden visible light absorption region due to the synergistic effect of the constituting materials. Furthermore, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanocomposite can be reused three times and the degradation rate of RhB was maintained at 77.9%. Thus, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanocomposite can act as a potential photocatalyst for the photodegradation of organic dyes in environmental applications.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, with the development of textile industry, water pollution has become a serious environmental issue [1,2]. More than ever, the removal of organic pollutants from wastewater has become a necessity, especially organic synthetic dyes, e.g., rhodamine B (RhB), acridine orange (AO), and methylene blue (MB) [3,4]. According to a research survey, some studies have reported the use of various technologies to remove organic dyes in the wastewater, such as adsorption, biodegradation, ion exchange, and photodegradation [5,6,7]. Among diverse technologies, photocatalytic reduction is a widely used method by inexhaustible solar energy [8]. Currently, several photocatalysts based on semiconductors (e.g., TiO2, ZnO, and ZnS) have been widely applied to photocatalysis [9]. Particularly, pure Bi2O3 has wide bandgap energy (2.0–3.9 eV) and exhibits significant visible light-responsive photocatalytic performance. Meanwhile, it has the merits of non-toxicity, excellent chemical stability, and abundant earth reserves [10,11,12,13]. Nevertheless, pure Bi2O3 is still limited, which can be related to its low interfacial area that limits electron transfer, and the easy recombination of electrons and holes [14]. In order to improve the photocatalytic activity of pure Bi2O3 photocatalysts, loading Bi2O3 into porous nanomaterials is one of the efficient methods.

Recently, metal–organic framework (MOF) has drawn extensive attention due to uniformly structural arrangements, high surface area, tunable pore size, rich functional sites, and excellent adsorption ability [15,16,17]. Besides, MOF materials have also been exploited as semiconductor-like photocatalysts, which can be related to the organic ligands of MOF being excited and transferring electrons to the metal center under visible light irradiation [18,19]. Among numerous MOFs, MOF-5 is a relatively highly coordinated Zn-based metal–organic framework (Zn-MOF) with excellent properties, which was considered as a photogenerated charge carrier to enhance the photocatalytic activity [20]. Hence, a feasible approach should be combining Zn-MOF with Bi2O3 for photocatalytic research.

Based on the aforementioned considerations, a series of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF composites were prepared via the one-pot hydrothermal method, and the photocatalytic performance of the composite was investigated for the degradation of RhB under visible light irradiation condition. The morphology, elemental composition, specific surface area, and structure of the composites were characterized through X-ray diffractometer (XRD), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), N2 physisorption, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), UV-Vis, etc. Moreover, the degradation rate of RhB by Bi2O3@Zn-MOF composite system under different catalyst dosages and initial RhB concentration was investigated. Importantly, repetitive experiments and photocatalytic degradation of different organic dyes were also carried out. Finally, the possible photocatalytic reaction mechanism on photocatalytic degradation of RhB was analyzed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Bismuth trioxide (Bi2O3), zinc(ii) nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O), terephthalic acid (H2BDC), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), RhB, congo red (CR), AO, neutral red (NR), and MB were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the aforementioned chemicals were of analytical grade and were used as received without further purification. Moreover, deionized water was used in all experiments.

2.2 Synthesis

The Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanocomposites were obtained by the hydrothermal method. In this method, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.59 g, 2 mmol) and H2BDC (0.33 g, 2 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (18 mL), and a certain amount of Bi2O3 was added to the above mixture, sonicated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the solution was stirred for 1 h and then transferred to an autoclave to be heated at 150°C for 6 h. The autoclave was cooled to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged, and the precipitate was washed with an appropriate amount of DMF for 2 h, followed by washing several times with DMF and water, and dried overnight at 60°C under a vacuum to obtain the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-x nanomaterials, x = 1, 2, and 3, corresponding to the addition of 0.14, 0.18, and 0.22 g Bi2O3, and the mole ratio of Bi2O3/Zn(NO3)2·6H2O was 0.15, 0.195, and 0.235, respectively. For comparison, Zn-MOF was synthesized through the same preparation process without Bi2O3.

2.3 Characterization techniques

FTIR spectra were applied to determine the chemical features of the nanocomposites on a PerkinElmer spectrum 100 using KBr pellet technology (4,000–400 cm−1). The XRD studies of the synthesized materials were investigated with D8 ADVANCE (Germany) using CuKĮ (1.5406 Å) radiation. The morphology of the synthesized materials was observed by SEM (Hitachi S4800), and the elemental mapping by EDX was performed on the scanning SEM mode. The surface area and particle sizes of the nanocomposites were studied using N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms using a Quantachrome Quadrasorb EVO apparatus (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, USA). Measurements of XPS were recorded in the Thermo ESCALAB 250XI. The UV-Vis spectra of the synthesized materials were measured by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-3600 PLUS, Japan).

2.4 Photodegradation test

The photocatalytic performance of all composites was assessed by RhB degradation. In the photocatalytic process, a certain amount of the nanomaterial was put into 50 mL of RhB solution (40 mg·L−1). To reach the adsorption–desorption equilibrium, the mixture was stirred in the dark for 0.5 h. Subsequently, the resulting solution was irradiated under visible light with a 300 W xenon lamp for 90 min. After every interval of 30 min, the suspension samples (3–4 mL) were taken from the reaction system and centrifuged to remove the catalyst, and the RhB concentration was determined by a UV-5200PC spectrophotometer (at the characteristic wavelength of 554 nm for RhB). The photodegradation rate of RhB was calculated as follows:

where C 0 is the initial mass concentration of dye solution, A 0 is the corresponding absorbance of dye solution before the reaction, and C and A are the mass concentration and absorbance corresponding to the solution at time t, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

The XRD patterns of synthesized Zn-MOF, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2, and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3 are shown in Figure 1a. The characteristic XRD patterns of Zn-MOF sample (8.8°, 12.0°, 16.8°, 25.4°, 27.8°, 35.4°, and 45.4°) in Figure 1a matched perfectly with those in the previous report [21,22], implying the generation of Zn-MOF. After the induction of Bi2O3, some XRD peaks of Zn-MOF-1 disappeared, and the appearance of new peaks of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF is also observed at 27.4°, 29.6°, and 33.2°, which are corresponding to the phase of Bi2O3 [23], which may be due to the relatively strong interaction between Bi2O3 and Zn-MOF. In the case of all composites (Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2, and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3), the characteristic diffraction peaks of three composites matched well. In addition, the intensity of the observed characteristic diffraction peaks increased with increasing Bi2O3 content. Based on the above analysis, the successful preparation of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF composites is clearly demonstrated.

XRD (a) and FTIR (b) spectra of Zn-MOF, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3, and the recovered Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 sample.

To analyze the functional groups of synthesized Zn-MOF, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2, and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3, FTIR spectroscopy was used (Figure 1b). In Figure 1b, for Zn-MOF, the characteristic peaks between 700 and 1,600 cm−1 were related to C═O, C–O, and C═C stretching vibration in carboxylic acid [24]. In comparison with Zn-MOF, similar peaks also appeared in the spectra of all Bi2O3@Zn-MOF composites, which proves that the structure of Zn-MOF was not changed after the introduction of Bi2O3 into the Zn-MOF. In particular, the appeared band at 519 cm−1 in Bi2O3@Zn-MOF composites was attributed to Bi–O of Bi2O3 [25], which indicates that the successful impregnation of Bi2O3 is on the framework of the Zn-MOF.

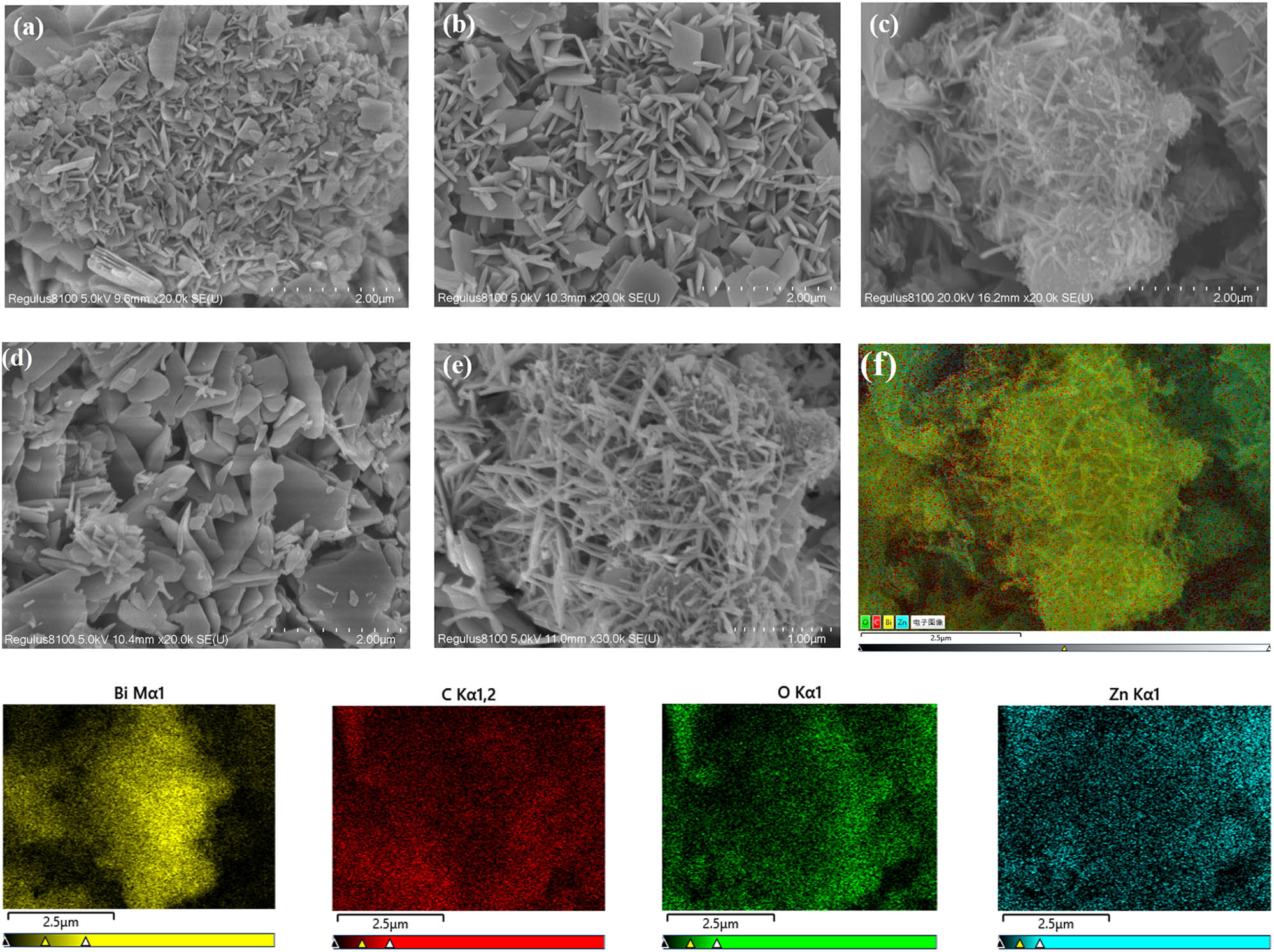

The structure and morphology of the as-prepared Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF with different additions of Bi2O3 were observed by SEM, as shown in Figure 2. In Figure 2a, the Zn-MOF sample is irregular nanosheets with thickness in the range of 30–50 nm. When the wrapping of Bi2O3, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 sample is composed of irregular nanosheets and rod-shaped structure (Figure 2b). With increasing Bi2O3 content, sample Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 (Figure 2c and e) exhibits quite different morphologies compared with Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 samples. It has a typical branched nanorod, and the existence of abundant pores may result in better adsorption of dye molecules and improves the catalytic material photocatalytic activity. For sample Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3 (Figure 2d), the agglomeration of rod-shaped particles and large irregular lumpy structure by the shrinkage of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3 composite was clear. This was possible because of the effect of the formation of Zn-MOF framework by the addition of excess Bi2O3. Additionally, the EDX elemental mappings of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 were further analyzed. As can be seen from Figure 2f, Bi, C, O, and Zn elements are present in the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite. Besides, the Bi and O elements were uniformly distributed over the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite, indicating that Bi2O3 adheres to the surface of the Zn-MOF. The EDX analysis results are consistent with results of the XRD and FTIR analysis.

SEM images of Zn-MOF (a), Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 (b), Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 (c and e), and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3 (d), and (f) the EDX analysis of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 sample and the related elemental mapping photographs of Bi, C, O, and Zn.

Figure 3a shows the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm curves of Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2. All the N2 adsorption–desorption curves show type IV adsorption, and their hysteresis loops reveal H3 type. Moreover, it can be known from Figure 3b that the pore sizes of Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 are mainly distributed in the range of 4–8 nm, which are characteristics of mesoporous materials. According to previous studies, the surface area and pore volume of pure Bi2O3 are 4.3 m2·g−1 and 0.018 cm3·g−1, respectively, indicating that pure Bi2O3 exhibits a low surface area and pore volume [26]. Interestingly, from Table 1, the incorporation of Bi2O3 slightly decreased the surface area and increased the average pore size of Zn-MOF, and this could be explained by partial obstruction of mesoporous materials by Bi2O3 particles. Furthermore, it should be noted that the larger size of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst pore structure will provide abundant surface adsorption and active sites, and further resulting in enhancement of the photocatalytic activity.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (a) and pore size distribution (b) of Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2.

Textural parameters of Zn-MOF and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2

| Entry | Sample type | Surface area (m2·g−1) | Average pore size (nm) | Pore volume (cm3·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zn-MOF | 17.51 | 11.02 | 0.048 |

| 2 | Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 | 13.21 | 13.74 | 0.045 |

The elemental compositions and the chemical states of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 were further evaluated using XPS, and the obtained results are given in Figure 4. In Figure 4a, the XPS full spectrum clearly shows that C, Zn, and Bi elements exist in Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composites. The XPS spectrum of C 1s (Figure 4b) presents two peaks at 284.6 and 288.8 eV that can be assigned to the C═C and C═O bonds, respectively [27]. The Zn 2p XPS spectra located at 1,022.8 and 1,045.9 eV are related to the Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2, respectively (Figure 4c), indicating that Zn is +2 valent [28]. Finally, for the Bi 4f spectra shown in Figure 4d, the peaks at 159.5 and 164.8 eV can be matched to Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, revealing the Bi3+ in Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 [29]. XPS analysis also proved that the successful synthesis of Bi2O3 on the Zn-MOF by the hydrothermal method.

XPS full spectrum (a), C 1s spectrum (b), Zn 2p spectrum (c), and Bi 4f spectrum (d) of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite.

The UV-Vis diffuse reflection spectroscopy (DRS) was also measured to examine the light absorption performances of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 5, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite displays the light absorption peak ranging between 300 and 460 nm. According to the previous articles, the Zn-MOF sample showed the absorption of light below 400 nm, and the absorption edge was about 379.7 nm [30]. After the introduction of Bi2O3, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 sample exhibited an absorption edge around 453 nm, and the light absorption was extended further to the visible region. The shift suggests that the existence of the synergistic effect between Bi2O3 and Zn-MOF in the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite can enhance the absorption of visible light, resulting in the improvement of the photodegradation ability.

UV-Vis light DRS of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite.

3.2 Photocatalytic activity of different photocatalysts

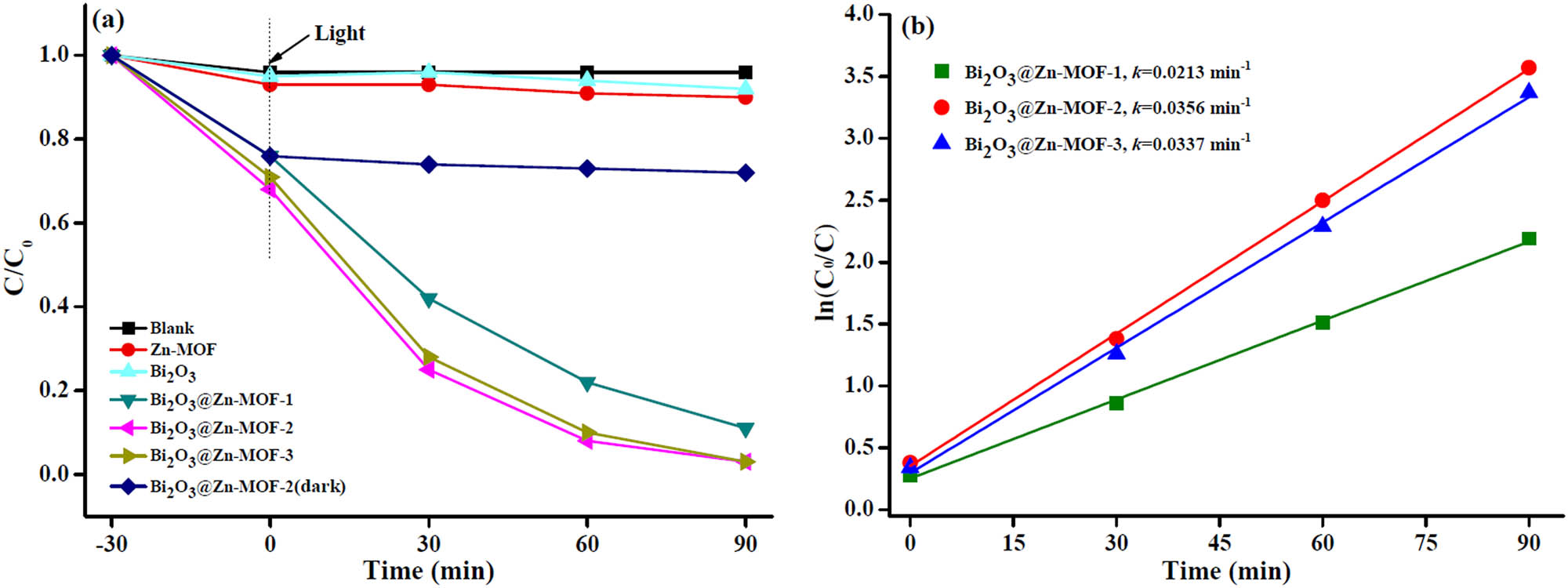

Figure 6a shows the RhB degradation over different photocatalysts. From Figure 6a, in the absence of catalyst, the RhB has no obvious degradation for 90 min, representing that the RhB is a stable and difficult to degrade organic dye. Both Zn-MOF and Bi2O3 samples were not effective in the degradation of RhB. However, it was found that after introduction of Bi2O3, the RhB degradation further obviously increased. Additionally, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 showed higher photocatalytic activity than Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3. In contrast, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 under light-free condition only showed some adsorption activity. Figure 6b shows the proposed pseudo-first-order kinetics for the photocatalytic degradation of RhB by Bi2O3@Zn-MOF with the addition of different mass ratios of Bi2O3, the degradation rate constants of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 are 1.67 and 1.06 times higher than that of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3, it may be due to the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 can provide a large pore size and abundant transport pores, and increasing the visible light irradiation. Thus, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 is chosen as the optimal photocatalyst.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB with different catalysts under visible light irradiation. (b) Pseudo-first-order kinetics plots of photocatalytic degradation of RhB with different catalysts.

3.3 Effect of the catalyst amount and RhB concentration

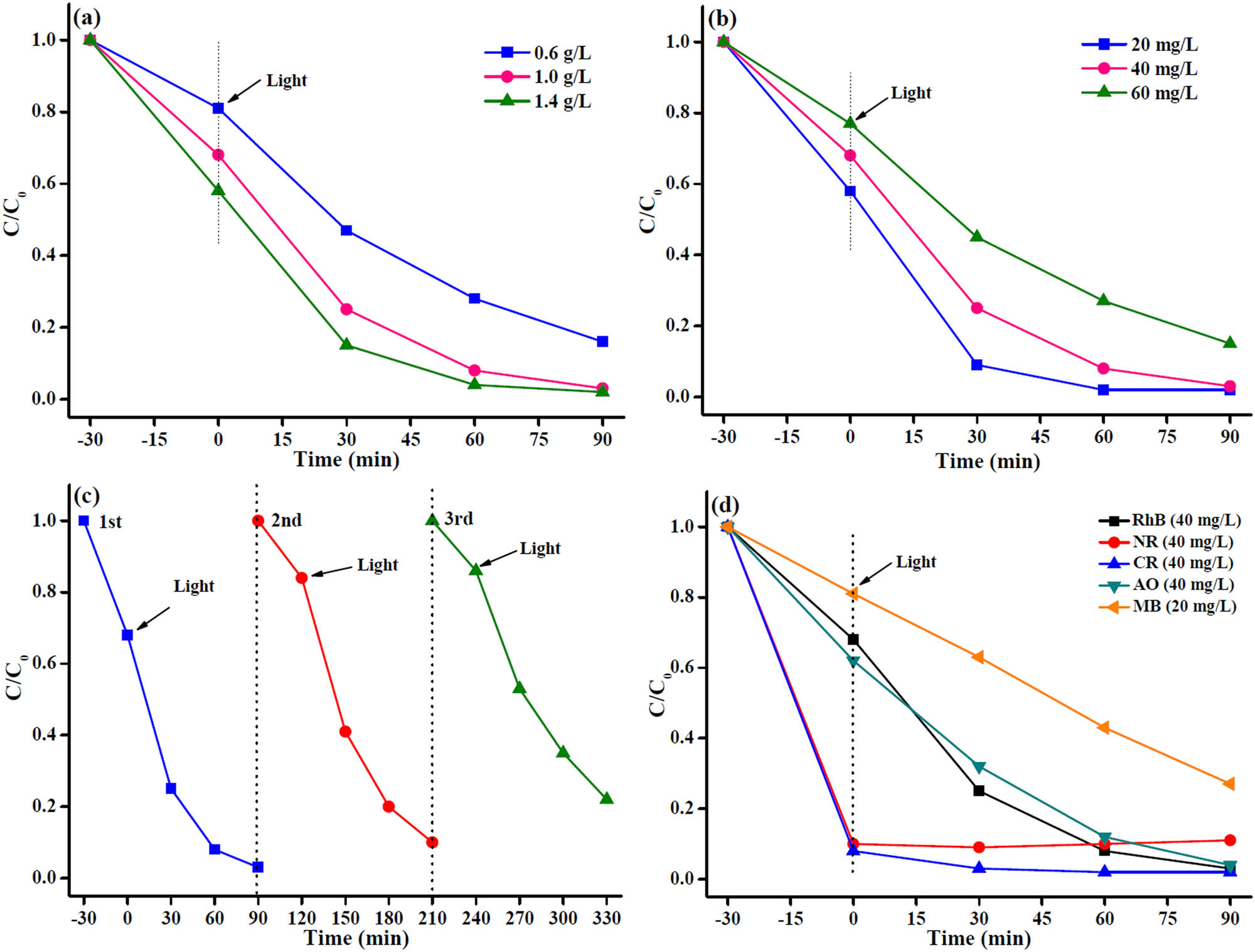

To investigate the effect of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst amount on the photocatalytic degradation of RhB, different amounts of catalyst (0.6, 1.0, and 1.4 g·L−1) were added to the photocatalytic system and the degradation profiles are depicted in Figure 7a. With the increase in catalyst amount, the degradation rate of RhB was also increased. It can see that the increase in catalyst amount may increase the number of active sites and the contact probability between dye molecules and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2. However, when the amount of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 increased to a certain level, the degradation rate was also slightly increased. This phenomenon may be attributed to the agglomeration of the catalyst leading to decrease in the radiation absorption, and as a result, the degradation rate was not significant change [31]. Therefore, the amount of catalyst was 1.0 g·L−1.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB with various dosages of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst. (b) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB with different concentrations using Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst. (c) Cyclic stability of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst after three cycles. (d) Photocatalytic degradation of various organic dyes using Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst.

The influence of initial RhB concentration on photocatalytic degradation activity of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 was studied (Figure 7b). The degradation rate gradually decreased as the RhB concentration increased from 20 to 60 mg·L−1. When the concentration of RhB is increased, it is probably related to more molecules to present around photocatalytic active sites, and thus, the light transmission capacity of the system decreases, leading to reduce the electron and hole pairs [32], and resulting in decrease in the degradation rate.

3.4 Stability test

To evaluate the stability of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst for its repetitive use, the repeated RhB degradation rate was investigated for three cycles. In each cycle experiment, the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst can be directly separated via centrifugation, and then washed, dried, and applied in the next experiment, and the experiment results are indicated in Figure 7c. Indeed, the photocatalytic degradation rate of RhB decreased from 97.2% to 77.9% after three cycles, which is probably due to the partial loss of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst throughout the cycling tests. Moreover, FTIR and XRD patterns of Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst after three recycling experiments were investigated and compared to the fresh catalyst. As shown in Figure 1, the results reveal that no significant changes occurred in the characteristic diffraction peaks, but the strength of the peaks weakened after three cycles. Furthermore, all these confirm that the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst is a better stability photocatalyst.

3.5 Photocatalytic degradation of different organic dyes

The degradation rate of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst for five organic dyes under visible light irradiation within 90 min was studied, and the results are shown in Figure 7d. For NR and CR degradation, the adsorption saturation was reached at 30 min of lightless reaction with the presence of the catalyst, resulting in good adsorption of those two dyes. Moreover, clearly seen, the photocatalytic performances of the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst were 97.2%, 96.1%, and 73.1% for RhB (40 mg·L−1), AO (40 mg·L−1), and MB (20 mg·L−1) degradation under visible light irradiation, respectively. It follows that the as-synthesized Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst can effectively degrade other organic dyes, and it can also be an excellent candidate for application in industrial wastewater treatment processes.

3.6 Possible photocatalytic mechanisms

Possible photocatalytic mechanism for degradation of RhB solution with Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite photocatalyst is illustrated in Figure 8. Under visible light irradiation, electrons (e−) and holes (h+) can be generated from Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2. According to the literature, the conduction band (CB) potential (E

CB) and valence band (VB) potential (E

VB) of Bi2O3 are −0.076 and 2.744 eV, respectively [33]. The E

CB and E

VB of Zn-MOF are −1.01 and 2.87 eV, respectively [34]. Then, h+ transfers from the VB of Zn-MOF to the VB of Bi2O3, and e− transfers from the CB of Zn-MOF to the CB of Bi2O3, resulting in efficient separation of e−–h+ pairs in Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 composite. Subsequently, the VB edge of Bi2O3 and Zn-MOF has a more positive VB potential than oxidation potential energy of H2O/˙OH (2.7 eV), and the partial h+ can participate in the generation of ·OH from H2O. Also, the position of the Zn-MOF conduction band is higher than the oxidation potential energy of O2/˙

Possible photocatalytic mechanisms of RhB solution using Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 catalyst.

4 Conclusion

This study aimed to successfully synthesize Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites (Bi2O3@Zn-MOF) with different Bi2O3 concentrations for the photocatalytic degradation of RhB under visible light irradiation. Among them, Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 has the highest photodegradation activity compared to Bi2O3, Zn-MOF, and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-1 and Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-3, which is related to the relatively larger specific surface area and pore size, the nanorods morphology, the synergistic effect the constituting materials lead to expand visible light absorption range. After 90 min of photocatalytic reaction, the degradation rate of RhB for Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 nanocomposite was estimated to be 97.2%. After three cycles, the degradation rate of RhB is still above 77.9%, and it has good reusability. Meanwhile, tests for the photodegradation of CR, AO, and MB also revealed that the Bi2O3@Zn-MOF-2 nanocomposite was an efficient photocatalyst. Overall, the obtained Bi2O3@Zn-MOF nanocomposites might be considered for application in the field of wastewater treatment.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22262001), the 2018 Thousand Level Innovative Talents Training Program of Guizhou Province, the Anshun Science and Technology Planning Project ([2021]1), the Guizhou Science and Technology Foundation ([2020]1Y054), the 2022 Innovative Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates of the Guizhou Education Department (202210667017), and the Student Research Training of Anshun University (asxysrt202202).

-

Author contributions: Qiuyun Zhang: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, formal analysis, project administration; Dandan Wang: methodology, formal analysis; Rongfei Yu: methodology, formal analysis; Linmin Luo: methodology, formal analysis; Weihua Li: visualization; Jingsong Cheng: visualization; Yutao Zhang: project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Hou JW, Yang HD, He BY, Ma JG, Lu Y, Wang QY. High photocatalytic performance of hydrogen evolution and dye degradation enabled by CeO2 modified TiO2 nanotube arrays. Fuel. 2022;310:122364.10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122364Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yang GH, Zhang DQ, Zhu G, Zhou TR, Song MT, Qu LL, et al. A Sm-MOF/GO nanocomposite membrane for efficient organic dye removal from wastewater. RSC Adv. 2020;10:8540–7.10.1039/D0RA01110JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Alshammari AS, Bagabas A, Alarifi N, Altamimi R. Effect of the nature of metal nanoparticles on the photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B. Top Catal. 2019;62:786–94.10.1007/s11244-019-01180-3Search in Google Scholar

[4] Mahmoodi NM. Surface modification of magnetic nanoparticle and dye removal from ternary systems. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;27:251–9.10.1016/j.jiec.2014.12.042Search in Google Scholar

[5] Khan M, Ali SW, Shahadat M, Sagadevan S. Applications of polyaniline-impregnated silica gel-based nanocomposites in wastewater treatment as an efficient adsorbent of some important organic dyes. Green Process Synth. 2022;11:617–30.10.1515/gps-2022-0063Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wang TT, Yang YT, Lim SC, Chiang CL, Lim JS, Lin YC, et al. Hydrogenation engineering of bimetallic Ag-Cu-modified-titania photocatalysts for production of hydrogen. Catal Today. 2022;388–389:79–86.10.1016/j.cattod.2020.11.012Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mahmoodi NM, Mokhtari-Shourijeh Z. Preparation of PVA-chitosan blend nanofiber and its dye removal ability from colored wastewater. Fibers Polym. 2015;16:1861–9.10.1007/s12221-015-5371-1Search in Google Scholar

[8] Khan F, Khan MS, Kamal S, Arshad M, Ahmad SI, Nami SAA. Recent advances in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide based nanocomposites for the photodegradation of dyes. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8:15940–55.10.1039/D0TC03684FSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Lian P, Qin AM, Liao L, Zhang KY. Progress on the nanoscale spherical TiO2 photocatalysts: Mechanisms, synthesis and degradation applications. Nano Sel. 2021;2:447–67.10.1002/nano.202000091Search in Google Scholar

[10] Natarajan K, Bajaj HC, Tayade RJ. Photocatalytic efficiency of bismuth oxyhalide (Br, Cl and I) nanoplates for RhB dye degradation under LED irradiation. J Ind Eng Chem. 2016;34:146–56.10.1016/j.jiec.2015.11.003Search in Google Scholar

[11] Devika S, Tayade RJ. Low temperature energy-efficient synthesis methods for bismuth-based nanostructured photocatalysts for environmental remediation application: A review. Chemosphere. 2022;304:135300.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135300Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Limpachanangkul P, Liu LC, Hunsom M, Piumsomboon P, Chalermsinsuwan B. Application of Bi2O3/TiO2 heterostructures on glycerol photocatalytic oxidation to chemicals. Energy Rep. 2022;8:1076–83.10.1016/j.egyr.2022.07.131Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sharma A, Sharma S, Mphahlele-Makgwane MM, Mittal A, Kumari K, Kumar N. Polyaniline modified Cu2+-Bi2O3 nanoparticles: Preparation and photocatalytic activity for Rhodamine B degradation. J Mol Structure. 2023;1271:134110.10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134110Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jiang HY, Liu JJ, Cheng K, Sun WB, Lin J. Enhanced visible light photocatalysis of Bi2O3 upon fluorination. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:20029–36.10.1021/jp406834dSearch in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang QY, Zhang YT, Cheng JS, Li H, Ma PH. An overview of metal-organic frameworks-based acid/base catalysts for biofuel synthesis. Curr Org Chem. 2020;24:1876–91.10.2174/1385272824999200726230556Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yadav S, Dixit R, Sharma S, Dutta S, Solanki K, Sharma RK. Magnetic metal-organic framework composites: structurally advanced catalytic materials for organic transformations. Mater Adv. 2021;2:2153–87.10.1039/D0MA00982BSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Zhang QY, Wang JL, Zhang SY, Ma J, Cheng JS, Zhang YT. Zr-based metal-organic frameworks for green biodiesel synthesis: A minireview. Bioengineering. 2022;9:700.10.3390/bioengineering9110700Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Xiao JD, Jiang HL. Metal-organic frameworks for photocatalysis and photothermal catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52:356–66.10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00521Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Jiang W, Li Z, Liu CB, Wang DD, Yan GS, Liu B, et al. Enhanced visible-light-induced photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline using BiOI/MIL-125(Ti) composite photocatalyst. J Alloy Compd. 2021;854:157166.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157166Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yang HM, Liu X, Song XL, Yang TL, Liang ZH, Fan CM. In situ electrochemical synthesis of MOF-5 and its application in improving photocatalytic activity of BiOBr. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2015;25:3987–94.10.1016/S1003-6326(15)64047-XSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Phan NTS, Le KKA, Phan TD. MOF-5 as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for Friedel-Crafts alkylation reactions. Appl Catal A-General. 2010;382:246–53.10.1016/j.apcata.2010.04.053Search in Google Scholar

[22] Yang M, Baia QH. Flower-like hierarchical Ni-Zn-MOF microspheres: Efficient adsorbents for dye removal. Colloids Surf A. 2019;582:123795.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.123795Search in Google Scholar

[23] Rahman NJA, Ramli A, Jumbri K, Uemura Y. Biodiesel production from N. oculata microalgae lipid in the presence of Bi2O3/ZrO2 catalysts. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020;11:553–64.10.1007/s12649-019-00619-8Search in Google Scholar

[24] Celebi N, Aydin MY, Soysal F, Yıldız N, Salimi K. Core/shell PDA@UiO-66 metal-organic framework nanoparticles for efficient visible-light photodegradation of organic dyes. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2020;3:11543–54.10.1021/acsanm.0c02636Search in Google Scholar

[25] Yang Q, Wei SQ, Zhang LM, Yang R. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of BiVO4/C-dots/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts for degradation of minocycline hydrochloride and Rhodamine B: optimization and mechanism investigation. N J Chem. 2020;44:17641–53.10.1039/D0NJ03375HSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Song Q, Li L, Luo HX, Liu Y, Yang CL. Hierarchical nanoflower-ring structure Bi2O3/(BiO)2CO3 composite for photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B. Chin J Inorg Chem. 2017;33:1161–71.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ahmad M, Chen S, Ye F, Quan X, Afzal S, Yu HT, et al. Efficient photo-Fenton activity in mesoporous MIL-100(Fe) decorated with ZnO nanosphere for pollutants degradation. Appl Catal B: Environ. 2019;245:428–38.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.12.057Search in Google Scholar

[28] Xu J, Wang XT, Fan CC, Qiao J. Effect of Pd-modification on photocatalytic H2 evolution over Cd0.8Zn0.2S/SiO2 from glycerol solution. J Fuel Chem Technol. 2013;41:323–7.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lu MJ, Yang Z, Zhao WF, Li Y. Study on photocatalytic activities of Bi2WO6 coupled with wide band-gap semiconductor titanium oxide under visible light irradiation. J Funct Mater. 2018;49:7093–8.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Yang L, Wang Q, Deng YJ, Wang XY, Ren HE, Yi ZY, et al. Effect of metal exchange on the light-absorbing and band-gap properties of nanoporous Zn-Cu based MOFs. Chin J Inorg Chem. 2018;34:1199–208.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Mirzaeifard Z, Shariatinia Z, Jourshabani M, Darvishi SMR. ZnO photocatalyst revisited: Effective photocatalytic degradation of emerging contaminants using S‑doped ZnO nanoparticles under visible light radiation. Ind & Eng Chem Res. 2020;59:15894–911.10.1021/acs.iecr.0c03192Search in Google Scholar

[32] Li F, Qin SN, Jia S, Wang GY. Pyrolytic synthesis of organosilane-functionalized carbon nanoparticles for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under visible light irradiation. Luminescence. 2021;36:711–20.10.1002/bio.3994Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Chen QG, Gu FF, Cheng XF, Jin XF. Bi2O3-ZnO composite materials: preparation and performance. J Funct Mater. 2017;48:155–9.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yao TT, Tan YW, Zhou Y, Chen YB, Xiang MH. Preparation of core-shell MOF-5/Bi2WO6 composite for the enhanced photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. J Solid State Chem. 2022;308:122882.10.1016/j.jssc.2022.122882Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”